Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Gamma ray

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2024) |

| Nuclear physics |

|---|

|

A gamma ray, also known as gamma radiation (symbol γ), is a penetrating form of electromagnetic radiation arising from high-energy interactions like the radioactive decay of atomic nuclei or astronomical events like solar flares. It consists of the shortest wavelength electromagnetic waves, typically shorter than those of X-rays. With frequencies above 30 exahertz (3×1019 Hz) and wavelengths less than 10 picometers (1×10−11 m), gamma ray photons have the highest photon energy of any form of electromagnetic radiation. Paul Villard, a French chemist and physicist, discovered gamma radiation in 1900 while studying radiation emitted by radium. In 1903, Ernest Rutherford named this radiation gamma rays based on their relatively strong penetration of matter; in 1900, he had already named two less penetrating types of decay radiation (discovered by Henri Becquerel) alpha rays and beta rays in ascending order of penetrating power.

Gamma rays from radioactive decay are in the energy range from a few kiloelectronvolts (keV) to approximately 8 megaelectronvolts (MeV), corresponding to the typical energy levels in nuclei with reasonably long lifetimes. The energy spectrum of gamma rays can be used to identify the decaying radionuclides using gamma spectroscopy. Very-high-energy gamma rays in the 100–1000 teraelectronvolt (TeV) range have been observed from astronomical sources such as the Cygnus X-3 microquasar.

Natural sources of gamma rays originating on Earth are mostly a result of radioactive decay and secondary radiation from atmospheric interactions with cosmic ray particles. However, there are other rare natural sources, such as terrestrial gamma-ray flashes, which produce gamma rays from electron action upon the nucleus. Notable artificial sources of gamma rays include fission, such as that which occurs in nuclear reactors, and high energy physics experiments, such as neutral pion decay and nuclear fusion.

The energy ranges of gamma rays and X-rays overlap in the electromagnetic spectrum, so the terminology for these electromagnetic waves varies between scientific disciplines. In some fields of physics, they are distinguished by their origin: gamma rays are created by nuclear decay while X-rays originate outside the nucleus. In astrophysics, gamma rays are conventionally defined as having photon energies above 100 keV and are the subject of gamma-ray astronomy, while radiation below 100 keV is classified as X-rays and is the subject of X-ray astronomy.

Gamma rays are ionizing radiation and are thus hazardous to life. They can cause DNA mutations, cancer and tumors, and at high doses burns and radiation sickness. Due to their high penetration power, they can damage bone marrow and internal organs. Unlike alpha and beta rays, they easily pass through the body and thus pose a formidable radiation protection challenge, requiring shielding made from dense materials such as lead or concrete. On Earth, the magnetosphere protects life from most types of lethal cosmic radiation other than gamma rays.

History of discovery

[edit]The first gamma ray source to be discovered was the radioactive decay process called gamma decay. In this type of decay, an excited nucleus emits a gamma ray almost immediately upon formation.[note 1] Paul Villard, a French chemist and physicist, discovered gamma radiation in 1900, while studying radiation emitted from radium. Villard knew that his described radiation was more powerful than previously described types of rays from radium, which included beta rays, first noted as "radioactivity" by Henri Becquerel in 1896, and alpha rays, discovered as a less penetrating form of radiation by Rutherford, in 1899. However, Villard did not consider naming them as a different fundamental type.[1][2] Later, in 1903, Villard's radiation was recognized as being of a type fundamentally different from previously named rays by Ernest Rutherford, who named Villard's rays "gamma rays" by analogy with the beta and alpha rays that Rutherford had differentiated in 1899.[3] The "rays" emitted by radioactive elements were named in order of their power to penetrate various materials, using the first three letters of the Greek alphabet: alpha rays as the least penetrating, followed by beta rays, followed by gamma rays as the most penetrating. Rutherford also noted that gamma rays were not deflected (or at least, not easily deflected) by a magnetic field, another property making them unlike alpha and beta rays.

Gamma rays were first thought to be particles with mass, like alpha and beta rays. Rutherford initially believed that they might be extremely fast beta particles, but their failure to be deflected by a magnetic field indicated that they had no charge.[4] In 1914, gamma rays were observed to be reflected from crystal surfaces, proving that they were electromagnetic radiation.[4] Rutherford and his co-worker Edward Andrade measured the wavelengths of gamma rays from radium, and found they were similar to X-rays, but with shorter wavelengths and thus, higher frequency. This was eventually recognized as giving them more energy per photon, as soon as the latter term became generally accepted. A gamma decay was then understood to usually emit a gamma photon.

Sources

[edit]Natural sources of gamma rays on Earth include gamma decay from naturally occurring radioisotopes such as potassium-40, and also as a secondary radiation from various atmospheric interactions with cosmic ray particles. Natural terrestrial sources that produce gamma rays include lightning strikes and terrestrial gamma-ray flashes, which produce high energy emissions from natural high-energy voltages.[5] Gamma rays are produced by a number of astronomical processes in which very high-energy electrons are produced. Such electrons produce secondary gamma rays by the mechanisms of bremsstrahlung, inverse Compton scattering and synchrotron radiation. A large fraction of such astronomical gamma rays are screened by Earth's atmosphere. Notable artificial sources of gamma rays include fission, such as occurs in nuclear reactors, as well as high energy physics experiments, such as neutral pion decay and nuclear fusion.

A sample of gamma ray-emitting material that is used for irradiating or imaging is known as a gamma source. It is also called a radioactive source, isotope source, or radiation source, though these more general terms also apply to alpha and beta-emitting devices. Gamma sources are usually sealed to prevent radioactive contamination, and transported in heavy shielding.

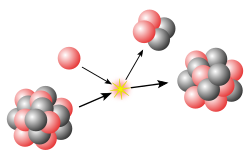

Radioactive decay (gamma decay)

[edit]Gamma rays are produced during gamma decay, which normally occurs after other forms of decay occur, such as alpha or beta decay. A radioactive nucleus can decay by the emission of an α or β particle. The daughter nucleus that results is usually left in an excited state. It can then decay to a lower energy state by emitting a gamma ray photon, in a process called gamma decay.

The emission of a gamma ray from an excited nucleus typically requires only 10−12 seconds. Gamma decay may also follow nuclear reactions such as neutron capture, nuclear fission, or nuclear fusion. Gamma decay is also a mode of relaxation of many excited states of atomic nuclei following other types of radioactive decay, such as beta decay, so long as these states possess the necessary component of nuclear spin. When high-energy gamma rays, electrons, or protons bombard materials, the excited atoms emit characteristic "secondary" gamma rays, which are products of the creation of excited nuclear states in the bombarded atoms. Such transitions, a form of nuclear gamma fluorescence, form a topic in nuclear physics called gamma spectroscopy. Formation of fluorescent gamma rays are a rapid subtype of radioactive gamma decay.

In certain cases, the excited nuclear state that follows the emission of a beta particle or other type of excitation, may be more stable than average, and is termed a metastable excited state, if its decay takes (at least) 100 to 1000 times longer than the average 10−12 seconds. Such relatively long-lived excited nuclei are termed nuclear isomers, and their decays are termed isomeric transitions. Such nuclei have half-lifes that are more easily measurable, and rare nuclear isomers are able to stay in their excited state for minutes, hours, days, or occasionally far longer, before emitting a gamma ray. The process of isomeric transition is therefore similar to any gamma emission, but differs in that it involves the intermediate metastable excited state(s) of the nuclei. Metastable states are often characterized by high nuclear spin, requiring a change in spin of several units or more with gamma decay, instead of a single unit transition that occurs in only 10−12 seconds. The rate of gamma decay is also slowed when the energy of excitation of the nucleus is small.[6]

An emitted gamma ray from any type of excited state may transfer its energy directly to any electrons, but most probably to one of the K shell electrons of the atom, causing it to be ejected from that atom, in a process generally termed the photoelectric effect (external gamma rays and ultraviolet rays may also cause this effect). The photoelectric effect should not be confused with the internal conversion process, in which a gamma ray photon is not produced as an intermediate particle (rather, a "virtual gamma ray" may be thought to mediate the process).

Decay schemes

[edit]

Co

One example of gamma ray production due to radionuclide decay is the decay scheme for cobalt-60, as illustrated in the accompanying diagram. First, 60

Co decays to excited 60

Ni by beta decay emission of an electron of 0.31 MeV. Then the excited 60

Ni decays to the ground state (see nuclear shell model) by emitting gamma rays in succession of 1.17 MeV followed by 1.33 MeV. This path is followed 99.88% of the time:

Another example is the alpha decay of 241

Am to form 237

Np; which is followed by gamma emission. In some cases, the gamma emission spectrum of the daughter nucleus is quite simple, (e.g. 60

Co/60

Ni) while in other cases, such as with (241

Am/237

Np and 192

Ir/192

Pt), the gamma emission spectrum is complex, revealing that a series of nuclear energy levels exist.

Particle physics

[edit]Gamma rays are produced in many processes of particle physics. Typically, gamma rays are the products of neutral systems which decay through electromagnetic interactions (rather than a weak or strong interaction). For example, in an electron–positron annihilation, the usual products are two gamma ray photons. If the annihilating electron and positron are at rest, each of the resulting gamma rays has an energy of ~ 511 keV and frequency of ~ 1.24×1020 Hz. Conversely, gamma rays above 1022 keV can interact with nuclei via pair production of an electron and positron.[7] Similarly, a neutral pion most often decays into two photons. Many other hadrons and massive bosons also decay electromagnetically. High energy physics experiments, such as the Large Hadron Collider, accordingly employ substantial radiation shielding.[8] Because subatomic particles mostly have far shorter wavelengths than atomic nuclei, particle physics gamma rays are generally several orders of magnitude more energetic than nuclear decay gamma rays. Since gamma rays are at the top of the electromagnetic spectrum in terms of energy, all extremely high-energy photons are gamma rays; for example, a photon having the Planck energy would be a gamma ray.

Other sources

[edit]A few gamma rays in astronomy are known to arise from gamma decay (see discussion of SN1987A), but most do not.

Photons from astrophysical sources that carry energy in the gamma radiation range are often explicitly called gamma-radiation. In addition to nuclear emissions, they are often produced by sub-atomic particle and particle-photon interactions. Those include electron-positron annihilation, neutral pion decay, bremsstrahlung, inverse Compton scattering, and synchrotron radiation.

Laboratory sources

[edit]In October 2017, scientists from various European universities proposed a means for sources of GeV photons using lasers as exciters through a controlled interplay between the cascade and anomalous radiative trapping.[9]

Terrestrial thunderstorms

[edit]Thunderstorms can produce a brief pulse of gamma radiation called a terrestrial gamma-ray flash. These gamma rays are thought to be produced by high intensity static electric fields accelerating electrons, which then produce gamma rays by bremsstrahlung as they collide with and are slowed by atoms in the atmosphere. Gamma rays up to 100 MeV can be emitted by terrestrial thunderstorms, and were discovered by space-borne observatories. This raises the possibility of health risks to passengers and crew on aircraft flying in or near thunderclouds.[10]

Solar flares

[edit]The most effusive solar flares emit across the entire EM spectrum, including γ-rays. The first confident observation occurred in 1972.[11]

Cosmic rays

[edit]Extraterrestrial, high energy gamma rays include the gamma ray background produced when cosmic rays (either high speed electrons or protons) collide with ordinary matter, producing pair-production gamma rays at 511 keV. Alternatively, bremsstrahlung are produced at energies of tens of MeV or more when cosmic ray electrons interact with nuclei of sufficiently high atomic number (see gamma ray image of the Moon near the end of this article, for illustration).

Pulsars and magnetars

[edit]The gamma ray sky (see illustration at right) is dominated by the more common and longer-term production of gamma rays that emanate from pulsars within the Milky Way. Sources from the rest of the sky are mostly quasars. Pulsars are thought to be neutron stars with magnetic fields that produce focused beams of radiation, and are far less energetic, more common, and much nearer sources (typically seen only in our own galaxy) than are quasars or the rarer gamma-ray burst sources of gamma rays. Pulsars have relatively long-lived magnetic fields that produce focused beams of relativistic speed charged particles, which emit gamma rays (bremsstrahlung) when those strike gas or dust in their nearby medium, and are decelerated. This is a similar mechanism to the production of high-energy photons in megavoltage radiation therapy machines (see bremsstrahlung). Inverse Compton scattering, in which charged particles (usually electrons) impart energy to low-energy photons boosting them to higher energy photons. Such impacts of photons on relativistic charged particle beams is another possible mechanism of gamma ray production. Neutron stars with a very high magnetic field (magnetars), thought to produce astronomical soft gamma repeaters, are another relatively long-lived star-powered source of gamma radiation.

Quasars and active galaxies

[edit]More powerful gamma rays from very distant quasars and closer active galaxies are thought to have a gamma ray production source similar to a particle accelerator. High energy electrons produced by the quasar, and subjected to inverse Compton scattering, synchrotron radiation, or bremsstrahlung, are the likely source of the gamma rays from those objects. It is thought that a supermassive black hole at the center of such galaxies provides the power source that intermittently destroys stars and focuses the resulting charged particles into beams that emerge from their rotational poles. When those beams interact with gas, dust, and lower energy photons they produce X-rays and gamma rays. These sources are known to fluctuate with durations of a few weeks, suggesting their relatively small size (less than a few light-weeks across). Such sources of gamma and X-rays are the most commonly visible high intensity sources outside the Milky Way galaxy. They shine not in bursts (see illustration), but relatively continuously when viewed with gamma ray telescopes. The power of a typical quasar is about 1040 watts, a small fraction of which is gamma radiation. Much of the rest is emitted as electromagnetic waves of all frequencies, including radio waves.

Gamma-ray bursts

[edit]The most intense sources of gamma rays are also the most intense sources of any type of electromagnetic radiation presently known. They are the "long duration burst" sources of gamma rays in astronomy ("long" in this context, meaning a few tens of seconds), and they are rare compared with the sources discussed above. By contrast, "short" gamma-ray bursts of two seconds or less, which are not associated with supernovae, are thought to produce gamma rays during the collision of pairs of neutron stars, or a neutron star and a black hole.[12]

The so-called long-duration gamma-ray bursts produce a total energy output of about 1044 joules (as much energy as the Sun will produce in its entire life-time) but in a period of only 20 to 40 seconds. Gamma rays are approximately 50% of the total energy output. The leading hypotheses for the mechanism of production of these highest-known intensity beams of radiation, are inverse Compton scattering and synchrotron radiation from high-energy charged particles. These processes occur as relativistic charged particles leave the region of the event horizon of a newly formed black hole created during supernova explosion. The beam of particles moving at relativistic speeds are focused for a few tens of seconds by the magnetic field of the exploding hypernova. The fusion explosion of the hypernova drives the energetics of the process. If the narrowly directed beam happens to be pointed toward the Earth, it shines at gamma ray frequencies with such intensity, that it can be detected even at distances of up to 10 billion light years, which is close to the edge of the visible universe.

Properties

[edit]Penetration of matter

[edit]

Due to their penetrating nature, gamma rays require large amounts of shielding mass to reduce them to levels which are not harmful to living cells, in contrast to alpha particles, which can be stopped by paper or skin, and beta particles, which can be shielded by thin aluminium. Gamma rays are best absorbed by materials with high atomic numbers (Z) and high density, which contribute to the total stopping power. Because of this, a lead (high Z) shield is 20–30% better as a gamma shield than an equal mass of a low-Z shielding material, such as aluminium, concrete, water, or soil; lead's major advantage is not in lower weight, but rather its compactness due to its higher density. Protective clothing, goggles and respirators can protect from internal contact with or ingestion of alpha or beta emitting particles, but provide no protection from gamma radiation from external sources.

The higher the energy of the gamma rays, the thicker the shielding made from the same shielding material is required. Materials for shielding gamma rays are typically measured by the thickness required to reduce the intensity of the gamma rays by one half (the half-value layer or HVL). For example, gamma rays that require 1 cm (0.4 inch) of lead to reduce their intensity by 50% will also have their intensity reduced in half by 4.1 cm of granite rock, 6 cm (2.5 inches) of concrete, or 9 cm (3.5 inches) of packed soil. However, the mass of this much concrete or soil is only 20–30% greater than that of lead with the same absorption capability.

Depleted uranium is sometimes used for shielding in portable gamma ray sources, due to the smaller half-value layer when compared to lead (around 0.6 times the thickness for common gamma ray sources, i.e. Iridium-192 and Cobalt-60)[13] and cheaper cost compared to tungsten.[14]

In a nuclear power plant, shielding can be provided by steel and concrete in the pressure and particle containment vessel, while water provides a radiation shielding of fuel rods during storage or transport into the reactor core. The loss of water or removal of a "hot" fuel assembly into the air would result in much higher radiation levels than when kept under water.

Matter interaction

[edit]

When a gamma ray passes through matter, the probability for absorption is proportional to the thickness of the layer, the density of the material, and the absorption cross section of the material. The total absorption shows an exponential decrease of intensity with distance from the incident surface:

where x is the thickness of the material from the incident surface, μ= nσ is the absorption coefficient, measured in cm−1, n the number of atoms per cm3 of the material (atomic density) and σ the absorption cross section in cm2.

As it passes through matter, gamma radiation ionizes via three processes:

- The photoelectric effect: This describes the case in which a gamma photon interacts with and transfers its energy to an atomic electron, causing the ejection of that electron from the atom. The kinetic energy of the resulting photoelectron is equal to the energy of the incident gamma photon minus the energy that originally bound the electron to the atom (binding energy). The photoelectric effect is the dominant energy transfer mechanism for X-ray and gamma ray photons with energies below 50 keV (thousand electronvolts), but it is much less important at higher energies.

- Compton scattering: This is an interaction in which an incident gamma photon loses enough energy to an atomic electron to cause its ejection, with the remainder of the original photon's energy emitted as a new, lower energy gamma photon whose emission direction is different from that of the incident gamma photon, hence the term "scattering". The probability of Compton scattering decreases with increasing photon energy. It is thought to be the principal absorption mechanism for gamma rays in the intermediate energy range 100 keV to 10 MeV. It is relatively independent of the atomic number of the absorbing material, which is why very dense materials like lead are only modestly better shields, on a per weight basis, than are less dense materials.

- Pair production: This becomes possible with gamma energies exceeding 1.02 MeV, and becomes important as an absorption mechanism at energies over 5 MeV (see illustration at right, for lead). By interaction with the electric field of a nucleus, the energy of the incident photon is converted into the mass of an electron-positron pair. Any gamma energy in excess of the equivalent rest mass of the two particles (totaling at least 1.02 MeV) appears as the kinetic energy of the pair and in the recoil of the emitting nucleus. At the end of the positron's range, it combines with a free electron, and the two annihilate, and the entire mass of these two is then converted into two gamma photons of at least 0.51 MeV energy each (or higher according to the kinetic energy of the annihilated particles).

The secondary electrons (and/or positrons) produced in any of these three processes frequently have enough energy to produce much ionization themselves.

Additionally, gamma rays, particularly high energy ones, can interact with atomic nuclei resulting in ejection of particles in photodisintegration, or in some cases, even nuclear fission (photofission).

Light interaction

[edit]High-energy (from 80 GeV to ~10 TeV) gamma rays arriving from far-distant quasars are used to estimate the extragalactic background light in the universe: The highest-energy rays interact more readily with the background light photons and thus the density of the background light may be estimated by analyzing the incoming gamma ray spectra.[15][16]

Gamma spectroscopy

[edit]Gamma spectroscopy is the study of the energetic transitions in atomic nuclei, which are generally associated with the absorption or emission of gamma rays. As in optical spectroscopy (see Franck–Condon effect) the absorption of gamma rays by a nucleus is especially likely (i.e., peaks in a "resonance") when the energy of the gamma ray is the same as that of an energy transition in the nucleus. In the case of gamma rays, such a resonance is seen in the technique of Mössbauer spectroscopy. In the Mössbauer effect the narrow resonance absorption for nuclear gamma absorption can be successfully attained by physically immobilizing atomic nuclei in a crystal. The immobilization of nuclei at both ends of a gamma resonance interaction is required so that no gamma energy is lost to the kinetic energy of recoiling nuclei at either the emitting or absorbing end of a gamma transition. Such loss of energy causes gamma ray resonance absorption to fail. However, when emitted gamma rays carry essentially all of the energy of the atomic nuclear de-excitation that produces them, this energy is also sufficient to excite the same energy state in a second immobilized nucleus of the same type.

Applications

[edit]

Gamma rays provide information about some of the most energetic phenomena in the universe; however, they are largely absorbed by the Earth's atmosphere. Instruments aboard high-altitude balloons and satellites missions, such as the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, provide our only view of the universe in gamma rays.

Gamma-induced molecular changes can also be used to alter the properties of semi-precious stones, and is often used to change white topaz into blue topaz.

Non-contact industrial sensors commonly use sources of gamma radiation in refining, mining, chemicals, food, soaps and detergents, and pulp and paper industries, for the measurement of levels, density, and thicknesses.[17] Gamma-ray sensors are also used for measuring the fluid levels in water and oil industries.[18] Typically, these use Co-60 or Cs-137 isotopes as the radiation source.

In the US, gamma ray detectors are beginning to be used as part of the Container Security Initiative (CSI). These machines are advertised to be able to scan 30 containers per hour.

Gamma radiation is often used to kill living organisms, in a process called irradiation. Applications of this include the sterilization of medical equipment (as an alternative to autoclaves or chemical means), the removal of decay-causing bacteria from many foods and the prevention of the sprouting of fruit and vegetables to maintain freshness and flavor.

Despite their cancer-causing properties, gamma rays are also used to treat some types of cancer, since the rays also kill cancer cells. In the procedure called gamma-knife surgery, multiple concentrated beams of gamma rays are directed to the growth in order to kill the cancerous cells. The beams are aimed from different angles to concentrate the radiation on the growth while minimizing damage to surrounding tissues.

Gamma rays are also used for diagnostic purposes in nuclear medicine in imaging techniques. A number of different gamma-emitting radioisotopes are used. For example, in a PET scan a radiolabeled sugar called fluorodeoxyglucose emits positrons that are annihilated by electrons, producing pairs of gamma rays that highlight cancer as the cancer often has a higher metabolic rate than the surrounding tissues. The most common gamma emitter used in medical applications is the nuclear isomer technetium-99m which emits gamma rays in the same energy range as diagnostic X-rays. When this radionuclide tracer is administered to a patient, a gamma camera can be used to form an image of the radioisotope's distribution by detecting the gamma radiation emitted (see also SPECT). Depending on which molecule has been labeled with the tracer, such techniques can be employed to diagnose a wide range of conditions (for example, the spread of cancer to the bones via bone scan).

Health effects

[edit]Gamma rays cause damage at a cellular level and are penetrating, causing diffuse damage throughout the body. However, they are less ionising than alpha or beta particles, which are less penetrating.[citation needed]

Low levels of gamma rays cause a stochastic health risk, which for radiation dose assessment is defined as the probability of cancer induction and genetic damage. The International Commission on Radiological Protection says "In the low dose range, below about 100 mSv, it is scientifically plausible to assume that the incidence of cancer or heritable effects will rise in direct proportion to an increase in the equivalent dose in the relevant organs and tissues"[19]: 51 (The unit mSv is milli-Seivert). High doses produce deterministic effects, which is the severity of acute tissue damage that is certain to happen. These effects are compared to the physical quantity absorbed dose measured by the unit gray (Gy).[19]: 61

Effects and body response

[edit]When gamma radiation breaks DNA molecules, a cell may be able to repair the damaged genetic material, within limits. However, a study of Rothkamm and Lobrich concerning X-ray radiation has shown that this repair process works well after high-dose exposure but is much slower in the case of a low-dose exposure.[20]

Studies have shown low-dose gamma radiation may be enough to cause cancer.[21] In a study of mice, they were given human-relevant low-dose gamma radiation, with genotoxic effects 45 days after continuous low-dose gamma radiation, with significant increases of chromosomal damage, DNA lesions and phenotypic mutations in blood cells of irradiated animals, covering the three types of genotoxic activity.[21] Another study studied the effects of acute ionizing gamma radiation in rats, up to 10 Gy, and who ended up showing acute oxidative protein damage, DNA damage, cardiac troponin T carbonylation, and long-term cardiomyopathy.[22]

Risk assessment

[edit]Natural gamma radiation in the United Kingdom of accounts for about 13% of the average radiation dose.[23] Natural exposure to gamma rays is about 1 to 2 mSv per year, and the average total amount of radiation received in one year per inhabitant in the USA is 3.6 mSv.[24] There might be a small increase in the dose around small particles of depleted uranium should these enter the human body from spent munitions, caused by increased effects of natural gamma radiation.[25]

By comparison, the radiation dose from chest radiography (about 0.06 mSv) is a fraction of the annual naturally occurring background radiation dose.[26] A chest CT delivers 5 to 8 mSv. A whole-body PET/CT scan can deliver 14 to 32 mSv depending on the protocol.[27] The dose from fluoroscopy of the stomach is much higher, approximately 50 mSv (14 times the annual background).

An acute full-body equivalent single exposure dose of 1 Sv (1000 mSv), or 1 Gy, will cause mild symptoms of acute radiation sickness, such as nausea and vomiting; and a dose of 2.0–3.5 Sv (2.0–3.5 Gy) causes more severe symptoms (i.e. nausea, diarrhea, hair loss, hemorrhaging, and inability to fight infections), and will cause death in a sizable number of cases—about 10% to 35% without medical treatment. A dose of 3–5 Sv (3–5 Gy) is considered approximately the LD50 (or the lethal dose for 50% of exposed population) for an acute exposure to radiation even with standard medical treatment.[28][29] A dose higher than 5 Sv (5 Gy) brings an increasing chance of death above 50%. Above 7.5–10 Sv (7.5–10 Gy) to the entire body, even extraordinary treatment, such as bone-marrow transplants, will not prevent the death of the individual exposed (see radiation poisoning).[30] (Doses much larger than this may, however, be delivered to selected parts of the body in the course of radiation therapy.)

For low-dose exposure, for example among nuclear workers, who receive an average yearly radiation dose of 19 mSv,[clarification needed] the risk of dying from cancer (excluding leukemia) increases by 2 percent. For a dose of 100 mSv, the risk increase is 10 percent. By comparison, risk of dying from cancer was increased by 32 percent for the survivors of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.[31]

Units of measurement and exposure

[edit]The following table shows radiation quantities in SI and non-SI units:

| Quantity | Unit | Symbol | Derivation | Year | SI equivalent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity (A) | becquerel | Bq | s−1 | 1974 | SI unit |

| curie | Ci | 3.7×1010 s−1 | 1953 | 3.7×1010 Bq | |

| rutherford | Rd | 106 s−1 | 1946 | 1000000 Bq | |

| Exposure (X) | coulomb per kilogram | C/kg | C⋅kg−1 of air | 1974 | SI unit |

| röntgen | R | esu / 0.001293 g of air | 1928 | 2.58×10−4 C/kg | |

| Absorbed dose (D) | gray | Gy | J⋅kg−1 | 1974 | SI unit |

| erg per gram | erg/g | erg⋅g−1 | 1950 | 1.0×10−4 Gy | |

| rad | rad | 100 erg⋅g−1 | 1953 | 0.010 Gy | |

| Equivalent dose (H) | sievert | Sv | J⋅kg−1 × WR | 1977 | SI unit |

| röntgen equivalent man | rem | 100 erg⋅g−1 × WR | 1971 | 0.010 Sv | |

| Effective dose (E) | sievert | Sv | J⋅kg−1 × WR × WT | 1977 | SI unit |

| röntgen equivalent man | rem | 100 erg⋅g−1 × WR × WT | 1971 | 0.010 Sv |

The measure of the ionizing effect of gamma and X-rays in dry air is called the exposure, for which a legacy unit, the röntgen, was used from 1928. This has been replaced by kerma, now mainly used for instrument calibration purposes but not for received dose effect. The effect of gamma and other ionizing radiation on living tissue is more closely related to the amount of energy deposited in tissue rather than the ionisation of air, and replacement radiometric units and quantities for radiation protection have been defined and developed from 1953 onwards. These are:

- The gray (Gy), is the SI unit of absorbed dose, which is the amount of radiation energy deposited in the irradiated material. For gamma radiation this is numerically equivalent to equivalent dose measured by the sievert, which indicates the stochastic biological effect of low levels of radiation on human tissue. The radiation weighting conversion factor from absorbed dose to equivalent dose is 1 for gamma, whereas alpha particles have a factor of 20, reflecting their greater ionising effect on tissue.

- The rad is the deprecated CGS unit for absorbed dose and the rem is the deprecated CGS unit of equivalent dose, used mainly in the USA.

Distinction from X-rays

[edit]

The conventional distinction between X-rays and gamma rays has changed over time. Originally, the electromagnetic radiation emitted by X-ray tubes almost invariably had a longer wavelength than the radiation (gamma rays) emitted by radioactive nuclei.[33] Older literature distinguished between X and gamma radiation on the basis of wavelength, with radiation shorter than some arbitrary wavelength, such as 10−11 m, defined as gamma rays.[34] Since the energy of photons is proportional to their frequency and inversely proportional to wavelength, this past distinction between X-rays and gamma rays can also be thought of in terms of its energy, with gamma rays considered to be higher energy electromagnetic radiation than are X-rays.

However, since current artificial sources are now able to duplicate any electromagnetic radiation that originates in the nucleus, as well as far higher energies, the wavelengths characteristic of radioactive gamma ray sources vs. other types now completely overlap. Thus, gamma rays are now usually distinguished by their origin: X-rays are emitted by definition by electrons outside the nucleus, while gamma rays are emitted by the nucleus.[33][35][36][37] Exceptions to this convention occur in astronomy, where gamma decay is seen in the afterglow of certain supernovas, but radiation from high energy processes known to involve other radiation sources than radioactive decay is still classed as gamma radiation.

For example, modern high-energy X-rays produced by linear accelerators for megavoltage treatment in cancer often have higher energy (4 to 25 MeV) than do most classical gamma rays produced by nuclear gamma decay. One of the most common gamma ray emitting isotopes used in diagnostic nuclear medicine, technetium-99m, produces gamma radiation of the same energy (140 keV) as that produced by diagnostic X-ray machines, but of significantly lower energy than therapeutic photons from linear particle accelerators. In the medical community today, the convention that radiation produced by nuclear decay is the only type referred to as "gamma" radiation is still respected.

Due to this broad overlap in energy ranges, in physics the two types of electromagnetic radiation are now often defined by their origin: X-rays are emitted by electrons (either in orbitals outside of the nucleus, or while being accelerated to produce bremsstrahlung-type radiation),[38] while gamma rays are emitted by the nucleus or by means of other particle decays or annihilation events. There is no lower limit to the energy of photons produced by nuclear reactions, and thus ultraviolet or lower energy photons produced by these processes would also be defined as "gamma rays" (indeed, this happens for the isomeric transition of the extremely low-energy isomer 229mTh).[39] The only naming-convention that is still universally respected is the rule that electromagnetic radiation that is known to be of atomic nuclear origin is always referred to as "gamma rays", and never as X-rays. However, in physics and astronomy, the converse convention (that all gamma rays are considered to be of nuclear origin) is frequently violated.

In astronomy, higher energy gamma and X-rays are defined by energy, since the processes that produce them may be uncertain and photon energy, not origin, determines the required astronomical detectors needed.[40] High-energy photons occur in nature that are known to be produced by processes other than nuclear decay but are still referred to as gamma radiation. An example is "gamma rays" from lightning discharges at 10 to 20 MeV, and known to be produced by the bremsstrahlung mechanism.

Another example is gamma-ray bursts, now known to be produced from processes too powerful to involve simple collections of atoms undergoing radioactive decay. This is part and parcel of the general realization that many gamma rays produced in astronomical processes result not from radioactive decay or particle annihilation, but rather in non-radioactive processes similar to X-rays.[clarification needed] Although the gamma rays of astronomy often come from non-radioactive events, a few gamma rays in astronomy are specifically known to originate from gamma decay of nuclei (as demonstrated by their spectra and emission half-life). A classic example is that of supernova SN 1987A, which emits an "afterglow" of gamma-ray photons from the decay of newly made radioactive nickel-56 and cobalt-56. Most gamma rays in astronomy, however, arise by other mechanisms.

See also

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ It is now understood that a nuclear isomeric transition, however, can produce inhibited gamma decay with a measurable and much longer half-life.

References

[edit]- ^ Villard, P. (1900). "Sur la réflexion et la réfraction des rayons cathodiques et des rayons déviables du radium". Comptes rendus. 130: 1010–1012. See also: Villard, P. (1900). "Sur le rayonnement du radium". Comptes rendus. 130: 1178–1179.

- ^ L'Annunziata, Michael F. (2007). Radioactivity: introduction and history. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier BV. pp. 55–58. ISBN 978-0-444-52715-8.

- ^ Rutherford named γ rays on page 177 of Rutherford, E. (1903). "The magnetic and electric deviation of the easily absorbed rays from radium". Philosophical Magazine. 6. 5 (26): 177–187. doi:10.1080/14786440309462912.

- ^ a b "Rays and Particles". Galileo.phys.virginia.edu. Retrieved 2013-08-27.

- ^ Fishman, G. J.; Bhat, P. N.; Mallozzi, R.; Horack, J. M.; Koshut, T.; Kouveliotou, C.; Pendleton, G. N.; Meegan, C. A.; Wilson, R. B.; Paciesas, W. S.; Goodman, S. J.; Christian, H. J. (May 27, 1994). "Discovery of Intense Gamma-Ray Flashes of Atmospheric Origin" (PDF). Science. 264 (5163): 1313–1316. Bibcode:1994STIN...9611316F. doi:10.1126/science.264.5163.1313. hdl:2060/19960001309. PMID 17780850. S2CID 20848006. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 10, 2012. Retrieved August 28, 2015.

- ^ van Dommelen, Leon. "14.20 Draft: Gamma Decay". Quantum Mechanics for Engineers. FAMU-FSU College of Engineering. Retrieved 2023-02-19.

- ^ Pecko, Stanislav; Slugeň, Vladimír; Chung, Won Sang; Algin, Abdullah; Yamashita, Osamu; Sekimoto, Takeyuki; Terakawa, Akira; Torchigin, V.P.; Torchigin, A.V.; Oliveira, Felipe M.F. de; Limousin, O. (2006-06-01). "Electron–positron pair production by photons: A historical overview". Radiation Physics and Chemistry. 75 (6). Pergamon: 614–623. Bibcode:2006RaPC...75..614H. doi:10.1016/j.radphyschem.2005.10.008. ISSN 0969-806X. Retrieved 2025-04-30.

- ^ Höfert, Manfred; Huhtinen, M; et al. (17 Oct 1996). Radiation protection considerations in the design of the LHC, CERN's Large Hadron Collider. American Health Physics Society Topical Meeting on the Health Physics of Radiation Generating Machines, San José, CA, USA, 5 - 8 Jan 1997. pp. 343–352. CERN-TIS-96-014-RP-CF.

- ^ Gonoskov, A.; Bashinov, A.; Bastrakov, S.; Efimenko, E.; Ilderton, A.; Kim, A.; Marklund, M.; Meyerov, I.; Muraviev, A.; Sergeev, A. (2017). "Ultrabright GeV Photon Source via Controlled Electromagnetic Cascades in Laser-Dipole Waves". Physical Review X. 7 (4) 041003. arXiv:1610.06404. Bibcode:2017PhRvX...7d1003G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevX.7.041003. S2CID 55569348.

- ^ Smith, Joseph; David M. Smith (August 2012). "Deadly Rays From Clouds". Scientific American. Vol. 307, no. 2. pp. 55–59. Bibcode:2012SciAm.307b..54D. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0812-54.

- ^ Chupp, E. L.; Forrest, D. J.; Higbie, P. R.; Suri, A. N.; Tsai, C.; Dunphy, P. P. (1973). "Solar Gamma Ray Lines observed during the Solar Activity of August 2 to August 11, 1972". Nature. 241 (5388): 333–335. Bibcode:1973Natur.241..333C. doi:10.1038/241333a0. S2CID 4172523.

- ^ "NASA - In a Flash NASA Helps Solve 35-year-old Cosmic Mystery". www.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2023-02-19.

- ^ "Half-Value Layer". Iowa State University Center for Nondestructive Evaluation. Retrieved 2024-05-10.

- ^ "Answer to Question #8929 Submitted to "Ask the Experts"". Health Physics Society. Retrieved 2024-05-10.

- ^ Bock, R. K.; et al. (2008-06-27). "Very-High-Energy Gamma Rays from a Distant Quasar: How Transparent Is the Universe?". Science. 320 (5884): 1752–1754. arXiv:0807.2822. Bibcode:2008Sci...320.1752M. doi:10.1126/science.1157087. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 18583607. S2CID 16886668.

- ^ Domínguez, Alberto; et al. (2015-06-01). "All the Light There Ever Was". Scientific American. Vol. 312, no. 6. pp. 38–43. ISSN 0036-8075.

- ^ Beigzadeh, A.M. (2019). "Design and improvement of a simple and easy-to-use gamma-ray densitometer for application in wood industry". Measurement. 138: 157–161. Bibcode:2019Meas..138..157B. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2019.02.017. S2CID 115945689.

- ^ Falahati, M. (2018). "Design, modelling and construction of a continuous nuclear gauge for measuring the fluid levels". Journal of Instrumentation. 13 (2): 02028. Bibcode:2018JInst..13P2028F. doi:10.1088/1748-0221/13/02/P02028. S2CID 125779702.

- ^ a b Valentin, J.; International Commission on Radiological Protection, eds. (2007). The 2007 recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection. ICRP publication. Oxford: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7020-3048-2.

- ^ Rothkamm, K; Löbrich, M (2003). "Evidence for a lack of DNA double-strand break repair in human cells exposed to very low x-ray doses". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 100 (9): 5057–62. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.5057R. doi:10.1073/pnas.0830918100. PMC 154297. PMID 12679524.

- ^ a b Graupner, Anne; Eide, Dag M.; Instanes, Christine; Andersen, Jill M.; Brede, Dag A.; Dertinger, Stephen D.; Lind, Ole C.; Brandt-Kjelsen, Anicke; Bjerke, Hans; Salbu, Brit; Oughton, Deborah; Brunborg, Gunnar; Olsen, Ann K. (2016-09-06). "Gamma radiation at a human relevant low dose rate is genotoxic in mice". Scientific Reports. 6 (1) 32977. Bibcode:2016NatSR...632977G. doi:10.1038/srep32977. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5011728. PMID 27596356.

- ^ Rosen, Elliot; Kryndushkin, Dmitry; Aryal, Baikuntha; Gonzalez, Yanira; Chehab, Leena; Dickey, Jennifer; Rao, V. Ashutosh (2020-06-04). "Acute total body ionizing gamma radiation induces long-term adverse effects and immediate changes in cardiac protein oxidative carbonylation in the rat". PLOS ONE. 15 (6) e0233967. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1533967R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0233967. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 7272027. PMID 32497067.

- ^ "Radioactivity in food and the environment (RIFE) reports". GOV.UK. Retrieved 2023-02-19.

- ^ United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation Annex E: Medical radiation exposures – Sources and Effects of Ionizing – 1993, p. 249, New York, UN

- ^ Pattison, J. E.; Hugtenburg, R. P.; Green, S. (2009). "Enhancement of natural background gamma-radiation dose around uranium microparticles in the human body". Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 7 (45): 603–611. doi:10.1098/rsif.2009.0300. PMC 2842777. PMID 19776147.

- ^ US National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements – NCRP Report No. 93 – pp 53–55, 1987. Bethesda, Maryland, USA, NCRP

- ^ Huang, Bingsheng; Law, Martin Wai-Ming; Khong, Pek-Lan (April 2009). "PET/CT total radiation dose calculations" (PDF). Radiology. 251 (1): 166–174. doi:10.1148/radiol.2511081300. PMID 19251940. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-01-23. Retrieved 2011-11-08.

- ^ Ryan JL (March 2012). "Ionizing radiation: the good, the bad, and the ugly". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 132 (3 Pt 2): 985–993. doi:10.1038/jid.2011.411. PMC 3779131. PMID 22217743.

- ^ "Radiation Exposure - Dose and Dose Rate (the Gray & Sievert)". Ionactive. 2022-12-13. Retrieved 2024-07-27.

- ^ Rodgerson, D.O.; Reidenberg, B.E.; Harris, A.g.; Pecora, A.L. (2012). "Potential for a pluripotent adult stem cell treatment for acute radiation sickness". World Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2 (3): 37–44. doi:10.5493/wjem.v2.i3.37. PMC 3905584. PMID 24520532.

- ^ Cardis, E (9 July 2005). "Risk of cancer after low doses of ionising radiation: retrospective cohort study in 15 countries". BMJ. 331 (7508): 77–0. doi:10.1136/bmj.38499.599861.E0. PMC 558612. PMID 15987704.

- ^ "CGRO SSC >> EGRET Detection of Gamma Rays from the Moon". Heasarc.gsfc.nasa.gov. 2005-08-01. Retrieved 2011-11-08.

- ^ a b Dendy, P. P.; B. Heaton (1999). Physics for Diagnostic Radiology. US: CRC Press. p. 12. ISBN 0-7503-0591-6.

- ^ Charles Hodgman, Ed. (1961). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 44th Ed. US: Chemical Rubber Co. p. 2850.

- ^ Feynman, Richard; Robert Leighton; Matthew Sands (1963). The Feynman Lectures on Physics, Vol.1. US: Addison-Wesley. pp. 2–5. ISBN 0-201-02116-1.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ L'Annunziata, Michael; Mohammad Baradei (2003). Handbook of Radioactivity Analysis. Academic Press. p. 58. ISBN 0-12-436603-1.

- ^ Grupen, Claus; G. Cowan; S. D. Eidelman; T. Stroh (2005). Astroparticle Physics. Springer. p. 109. ISBN 3-540-25312-2.

- ^ "Bremsstrahlung radiation" is "braking radiation", but "acceleration" is being used here in the specific sense of the deflection of an electron from its course: Serway, Raymond A; et al. (2009). College Physics. Belmont, CA: Brooks Cole. p. 876. ISBN 978-0-03-023798-0.

- ^ Shaw, R. W.; Young, J. P.; Cooper, S. P.; Webb, O. F. (1999). "Spontaneous Ultraviolet Emission from 233Uranium/229Thorium Samples". Physical Review Letters. 82 (6): 1109–1111. Bibcode:1999PhRvL..82.1109S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.82.1109.

- ^ "Gamma-Ray Telescopes & Detectors". NASA GSFC. Retrieved 2011-11-22.

External links

[edit]- Basic reference on several types of radiation Archived 2018-04-25 at the Wayback Machine

- Radiation Q & A

- GCSE information

- Radiation information Archived 2010-06-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Gamma-ray bursts

- The Lund/LBNL Nuclear Data Search – Contains information on gamma-ray energies from isotopes.

- Mapping soils with airborne detectors Archived 2010-11-11 at the Wayback Machine

- The LIVEChart of Nuclides – IAEA with filter on gamma-ray energy

- Health Physics Society Public Education Website

Gamma ray

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Characteristics

Position in Electromagnetic Spectrum

Gamma rays represent the highest-energy portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, exhibiting both wave-like and particle-like properties as described by quantum electrodynamics. As electromagnetic waves, they are characterized by their extremely short wavelengths, typically less than 10 picometers (pm), and correspondingly high frequencies exceeding 30 exahertz (EHz). In the particle picture, gamma rays manifest as photons with energies greater than 100 kiloelectronvolts (keV), making them the most energetic form of electromagnetic radiation.[7][1][8] The electromagnetic spectrum arranges all forms of electromagnetic radiation by increasing frequency (or decreasing wavelength), from long radio waves to short gamma rays. Gamma rays occupy the position immediately adjacent to X-rays on the high-energy end, with no abrupt boundary but rather a conventional demarcation around 100 keV. This positioning highlights their role as the pinnacle of the spectrum, where photon energies can extend into the mega- and giga-electronvolt ranges in extreme cases.[7][9] Historically, the term "gamma ray" was coined by Ernest Rutherford in 1903 to describe a highly penetrating radiation discovered emanating from radioactive nuclei, distinguishing it from X-rays, which were identified earlier by Wilhelm Röntgen as emissions from electron interactions in atomic shells. Unlike stricter physical boundaries in other spectral regions, the gamma ray-X-ray divide is primarily based on origin—nuclear processes for gamma rays versus atomic or accelerated electron sources for X-rays—leading to significant energy overlap, particularly in the 100 keV to 10 MeV range. This convention persists in scientific usage, even as modern detection blurs the lines based on production mechanisms. In a typical spectrum diagram, gamma rays appear as the final segment after X-rays, emphasizing their extreme brevity in wavelength and intensity in energy.[10][11][12]Energy Range and Production Threshold

Gamma rays are defined as photons with energies exceeding 100 keV, spanning a conventional range from approximately 100 keV up to several TeV, though there is no strict upper limit to their possible energies.[7] This range places them at the highest-energy end of the electromagnetic spectrum, far beyond visible light or even X-rays. The energy of a gamma-ray photon is related to its frequency and wavelength by the fundamental equation where is Planck's constant, and is the speed of light.[13] Photons in this energy regime require significant excitation to produce, distinguishing them from lower-energy radiation. The production of gamma rays typically occurs through nuclear transitions in excited atomic nuclei, where nuclear energy levels differ by amounts typically from tens of keV to several MeV, though lower energies occur, with gamma rays conventionally starting above ~100 keV to distinguish from X-rays. The conventional energy threshold helps distinguish gamma rays (nuclear origin) from X-rays (atomic origin), despite significant energy overlap, as nuclear processes often involve higher excitation energies but not exclusively. In contrast, X-rays originate from electron rearrangements in atomic orbitals, leading to a clear distinction based on the physical origin despite some energy overlap.[11] The overlap between gamma rays and hard X-rays occurs in the 10–100 keV band, where the classification depends primarily on the emission mechanism: nuclear or extranuclear processes for gamma rays versus atomic electron interactions for X-rays.[14] For instance, ultra-high-energy gamma rays exceeding 100 TeV have been detected from cosmic sources, such as galactic PeVatrons observed by the Large High Altitude Air Shower Observatory (LHAASO), highlighting the extreme conditions in astrophysical accelerators capable of producing such radiation.[15] These detections underscore the vast energy scale accessible in non-terrestrial environments.Historical Development

Initial Discovery

The initial observations of what would later be known as gamma rays emerged from the pioneering work on radioactivity by French physicist Henri Becquerel. In 1896, Becquerel discovered that uranium salts spontaneously emit invisible, penetrating radiation capable of fogging photographic plates even in the absence of light, a finding he connected to the decay processes of uranium compounds through subsequent experiments up to 1900.[16] These emissions were initially referred to as "Becquerel rays" due to their novel penetrating properties.[17] In 1900, French chemist and physicist Paul Villard extended these investigations by studying radiation from radium salts supplied by Becquerel. Villard detected an even more penetrating form of radiation using photographic plates wrapped in black paper to exclude light; he placed radium samples behind absorbers like lead sheets and observed that a residual radiation could still expose the plates after traversing thicknesses of lead up to several centimeters, surpassing the penetration of X-rays.[18] In his report to the French Academy of Sciences, Villard described this highly energetic emission as "rays of Becquerel," noting its straight-line propagation unaffected by magnetic fields, and conducted the experiments by confining the radium in a lead container with a narrow aperture to form a directed beam.[19] Building on Villard's findings, British physicist Ernest Rutherford formally identified and named this radiation in 1903 as "gamma rays" (γ-rays) to differentiate it from the positively charged alpha particles and negatively charged beta particles he had characterized earlier from radioactive sources like radium.[20] Rutherford emphasized the gamma rays' exceptional ability to penetrate matter, likening them to X-rays in their behavior.[21] Subsequent early experiments focused on absorption characteristics, revealing that gamma rays required significantly thicker shielding—often several times that needed for X-rays—to be attenuated, as demonstrated in Villard's lead absorption tests and Rutherford's deflection studies.[18] Their electromagnetic nature was confirmed by 1914 through observations of diffraction when gamma rays interacted with crystal surfaces, establishing them as high-energy photons in the electromagnetic spectrum.[10]Key Milestones in Detection and Understanding

In the 1920s and 1930s, significant advancements in gamma ray detection emerged with the development of the Geiger-Müller counter by Hans Geiger and Walther Müller in 1928, which detected ionizing radiation including gamma rays through secondary electrons produced in interactions with matter.[22] Cloud chambers, refined during this period, visualized particle tracks from gamma ray-induced events, enabling early studies of their interactions. A pivotal theoretical and experimental milestone was Walther Bothe's 1924 coincidence experiment with Geiger, which used needle counters to detect simultaneous events from Compton scattering, confirming the corpuscular nature of gamma rays and supporting wave-particle duality.[23] Building on these foundations in the 1940s and 1950s, scintillation detectors revolutionized gamma ray detection with the 1948 invention of thallium-activated sodium iodide (NaI:Tl) crystals by Robert Hofstadter, offering higher efficiency and energy resolution for spectroscopy compared to earlier gas-based counters.[24] Semiconductor detectors, particularly lithium-drifted germanium (Ge(Li)) devices developed in the early 1960s, further enhanced precision by providing superior energy resolution for gamma ray identification.[25] Arthur Compton's 1923 scattering formula, originally for X-rays, was increasingly applied to quantify gamma ray energies through measurements of scattered photon wavelengths in these new instruments. The space era marked a leap in gamma ray astronomy, beginning with NASA's Explorer 11 satellite in 1961, which achieved the first detection of cosmic gamma rays above 50 MeV, recording 22 events despite its short operational life.[26] A major breakthrough came in 1967 when the U.S. military Vela satellites, designed to monitor nuclear tests, serendipitously detected the first gamma-ray bursts (GRBs) on July 2, revealing brief, intense flashes of cosmic gamma radiation that puzzled scientists and spurred decades of research into their origins.[27] In the 1970s, the European Space Research Organisation's COS-B observatory, launched in 1975 and active until 1982, produced the first detailed sky maps of galactic gamma ray sources using a spark chamber telescope, identifying over 20 discrete sources and advancing understanding of high-energy cosmic processes.[28] Further progress in the 1990s was driven by NASA's Compton Gamma Ray Observatory (CGRO), launched in 1991 and operating until 2000, which featured instruments like the Burst and Transient Source Experiment (BATSE) that detected over 2,700 GRBs and mapped the gamma-ray sky, confirming their extragalactic nature and providing foundational data on diffuse emission and point sources.[29] Recent developments from 2023 to 2025 have deepened insights into transient gamma ray phenomena, exemplified by NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope detecting the repeating gamma-ray burst GRB 250702B on July 2, 2025, which exhibited multiple emissions over nearly a full day—unprecedented duration challenging models of burst progenitors.[30] Concurrently, China's Einstein Probe, launched in 2024, observed exotic gamma-ray bursts in 2024-2025, including off-axis events with extended emissions, integrating multi-wavelength data to refine theories of relativistic jets and high-energy astrophysics.[31] These observations build on the initial recognition of gamma rays by Paul Villard in 1900 and Ernest Rutherford's naming in 1903, extending terrestrial detection to cosmic scales.[27]Production Sources

Nuclear Decay Processes

Gamma decay occurs when an excited atomic nucleus transitions to a lower energy state by emitting a high-energy photon known as a gamma ray, typically following alpha or beta decay that leaves the daughter nucleus in an excited configuration.[32] This process releases the excess nuclear energy without altering the atomic number or mass number of the nucleus, distinguishing it from alpha and beta decays.[33] The emitted gamma ray carries away the precise energy difference between the initial and final nuclear states, often in the range of tens to thousands of keV.[34] A notable example of gamma decay is the isomeric transition in technetium-99m (Tc-99m), a metastable isotope widely used in medical imaging, where the nucleus decays by emitting a 140 keV gamma ray to reach the ground state of technetium-99.[35] This transition has a half-life of approximately 6 hours, making Tc-99m suitable for diagnostic procedures due to its short-lived emission.[36] In radioactive decay schemes, gamma emission often follows beta decay in a cascade sequence, as depicted in energy level diagrams that illustrate the nuclear transitions and their probabilities. For instance, cobalt-60 (Co-60) undergoes beta-minus decay to an excited state of nickel-60, which then de-excites via two sequential gamma emissions at 1.17 MeV and 1.33 MeV, with branching ratios of nearly 100% for the cascade.[37] Co-60 has a half-life of 5.27 years, and these gamma rays are emitted in coincidence, providing a characteristic signature for detection.[38] Such schemes highlight how multiple gamma rays can be produced in a single decay chain to fully relax the nucleus. Gamma rays are also produced promptly in nuclear reactions, particularly through radiative capture processes like the (n, γ) reaction, where a nucleus captures a neutron and emits a gamma ray to conserve energy and achieve a bound state.[39] These prompt gamma rays are emitted almost instantaneously and carry the binding energy released in the capture. The energetics of such reactions are quantified by the Q-value, defined as where and are the masses of the initial and final particles, and is the speed of light; a positive Q-value indicates an exothermic reaction releasing energy as gamma radiation.[40] Among common isotopes emitting gamma rays in decay processes, cesium-137 (Cs-137) is frequently used for calibration due to its prominent 662 keV gamma emission from the decay of its daughter barium-137m, occurring with an intensity of about 85%.[41] Cs-137 has a half-life of 30.17 years, making its gamma ray a standard reference for energy calibration in spectroscopy systems.[42]High-Energy Particle Interactions

High-energy particle interactions provide a key mechanism for gamma ray production, involving the acceleration, collision, or decay of subatomic particles at relativistic speeds. These processes generate both continuous spectra and discrete emission lines, contrasting with the discrete, lower-energy gamma rays from nuclear decays. Such interactions occur in cosmic ray cascades and laboratory accelerators, where charged particles interact with matter to emit photons across a broad energy range, from keV to GeV scales. Bremsstrahlung arises from the deceleration of charged particles, primarily electrons, in the Coulomb fields of atomic nuclei, resulting in a continuous gamma ray spectrum extending up to the incident particle's kinetic energy. This process is prominent in high-energy environments, where relativistic electrons lose energy rapidly through radiation. In the non-relativistic limit, the instantaneous power radiated by an accelerating charge is described by the Larmor formula: where is the acceleration, the vacuum permittivity, and the speed of light; for relativistic cases relevant to gamma production, the radiated power scales with the square of the Lorentz factor , enhancing emission efficiency.[43][44] Electron-positron annihilation yields discrete gamma rays when a positron () and electron () collide, converting their combined rest masses into two photons via the reaction , with each photon having an energy of 511 keV to conserve four-momentum; the photons are emitted back-to-back in the center-of-mass frame. This process is fundamental in particle physics experiments and contributes to gamma ray backgrounds in accelerators.[45][46] Neutral pion () decay is a prolific source of gamma rays in high-energy interactions, proceeding dominantly via with a branching ratio of approximately 98.8%, where each photon carries 67.5 MeV in the pion's rest frame, half the pion's rest energy of 135 MeV. Pions are copiously produced as secondaries in cosmic ray-induced atmospheric showers and proton-nucleus collisions, leading to cascades of these 67.5 MeV gamma rays that dominate the observed flux in that energy band.[47] In laboratory settings, linear accelerators (LINACs) routinely produce gamma rays through bremsstrahlung by accelerating electrons to multi-GeV energies and impinging them on high-Z targets like tungsten. For instance, the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center (SLAC) accelerates electrons to up to 50 GeV, generating forward-peaked bremsstrahlung beams with photon energies reaching GeV levels, used for applications in nuclear physics and material science. These setups achieve high brilliance and tunability, enabling precise studies of gamma ray-matter interactions.[48][49]Astrophysical and Terrestrial Phenomena

Gamma rays are produced in terrestrial thunderstorms through relativistic runaway electron avalanches (RREAs), where strong electric fields accelerate electrons to near-light speeds, leading to bremsstrahlung and subsequent gamma-ray flashes known as terrestrial gamma-ray flashes (TGFs).[50] These events, lasting microseconds, emit gamma rays with energies up to tens of MeV and have been observed emanating from thunderclouds, with recent aircraft campaigns like ALOFT in 2025 confirming their association with rapidly charging storm systems that produce oscillating gamma-ray glows.[51] In 2025, studies revealed downward TGFs linked to lightning collisions, highlighting how photoelectric effects in air initiate these avalanches and explain enhanced gamma radiation during storms.[52] Another 2025 investigation detailed threshold electric fields required for RREA initiation, underscoring the role of thunderstorm dynamics in sustaining these high-energy emissions.[53] Solar flares generate gamma rays primarily through bremsstrahlung radiation from electrons accelerated to relativistic speeds in magnetic reconnection events, with observed energies reaching up to 100 MeV or higher.[54] Fermi Large Area Telescope observations have detected over 18 such flares emitting gamma rays above 100 MeV, providing evidence of ion acceleration during the impulsive phase.[54] These emissions, often peaking in the tens of MeV range, arise from interactions in the solar corona and chromosphere, as confirmed by multi-wavelength data from events like behind-the-limb flares.[55] In Earth's atmosphere, cosmic rays—primarily high-energy protons—interact with air nuclei to produce secondary gamma rays via pion decay, where neutral pions rapidly decay into two gamma-ray photons each.[56] This process creates a "pion-decay bump" in the gamma-ray spectrum around 100 MeV to 1 GeV, observable as diffuse atmospheric emission and a key signature of hadronic interactions.[57] Recent 2025 analyses of air showers have probed this background, confirming gamma rays as a major component of secondary cosmic radiation reaching sea level.[58] Pulsars and magnetars, rapidly rotating neutron stars with intense magnetic fields, emit gamma rays through synchrotron radiation from accelerated charged particles and inverse Compton scattering of lower-energy photons.[59] In pulsars like Vela, inverse Compton processes near the light cylinder upscatter synchrotron photons to gamma-ray energies, producing pulsed emission detectable up to TeV levels.[60] Magnetars, with fields exceeding 10^14 G, release gamma rays in giant flares via magnetic reconnection, as evidenced by eruptions observed in nearby galaxies by NASA's Swift and NuSTAR in multi-wavelength campaigns.[61] These events, rare within our Milky Way but prolific extragalactically, generate bursts up to 100 keV initially, with tails extending to higher energies.[62] Extragalactic sources such as quasars and active galactic nuclei (AGN) produce gamma rays from relativistic jets powered by supermassive black holes, where accelerated particles undergo synchrotron and inverse Compton processes in outflows.[63] Fermi observations of quasars like PKS 1441+25 have revealed gamma-ray outbursts escaping dense environments, with fluxes providing constraints on intergalactic radiation fields.[64] Quasar-driven outflows contribute to the diffuse extragalactic gamma-ray background through proton interactions, as modeled in studies of high-redshift sources.[65] Gamma-ray bursts (GRBs), the most luminous explosions in the universe, originate from cataclysmic events like massive star collapses or neutron star mergers in distant galaxies. In 2025, NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope detected GRB 250702B, a repeating event lasting over a day with multiple peaks, challenging standard models and confirmed as extragalactic by follow-up with Hubble and the Very Large Telescope.[66] This unusual burst, initially triggered on July 2, exhibited energies in the keV to MeV range, suggesting a novel central engine possibly involving a black hole-neutron star system.[67] The Einstein Probe mission, launched in 2024, identified exotic GRBs in 2025, including puzzling transients like EP240408a with multi-wavelength afterglows indicating jetted tidal disruptions or magnetar activity.[31] A 2025 PNAS study recreated GRB fireballs in laboratory plasmas at CERN, revealing how magnetic fields suppress low-energy gamma rays, explaining observational deficits in burst spectra and probing hidden cosmic magnetism.[68]Physical Properties

Interaction with Matter

Gamma rays primarily interact with matter through three fundamental processes: the photoelectric effect, Compton scattering, and pair production, each characterized by distinct energy dependencies and interaction probabilities that govern energy loss in materials.[69] These interactions are probabilistic, with cross sections determining the likelihood of occurrence per unit path length.[70] The photoelectric effect dominates for gamma rays with energies below approximately 500 keV, where the incident photon is fully absorbed by an atomic electron, typically from an inner shell, ejecting it with kinetic energy equal to the photon energy minus the binding energy.[70] The cross section for this process, which measures the effective interaction area per atom, is proportional to , with the atomic number of the material and the photon energy in appropriate units.[69] This strong dependence on makes the photoelectric effect more probable in high-atomic-number materials, such as lead, at lower energies.[71] Compton scattering prevails in the intermediate energy range of 0.5 to 10 MeV, during which the gamma ray photon collides with a loosely bound atomic electron, transferring part of its energy to the electron as kinetic energy while the scattered photon continues with reduced energy and altered direction.[70] The wavelength shift in this inelastic scattering is described by the Compton formula: where is Planck's constant, is the electron rest mass, is the speed of light, and is the scattering angle relative to the incident direction.[71] The cross section for Compton scattering follows the Klein-Nishina relation, which decreases with increasing photon energy and is roughly proportional to the electron density (thus to ) but independent of nuclear structure.[69] Pair production occurs when gamma ray energies exceed 1.022 MeV, the rest mass energy equivalent of an electron-positron pair (), allowing the photon to be annihilated in the strong Coulomb field near an atomic nucleus, creating an electron () and positron () with combined kinetic energy equal to the excess photon energy.[69] The threshold condition is thus , and the cross section rises logarithmically with energy, proportional to due to the nuclear field's influence.[70] This process becomes the primary interaction mechanism above several MeV in high- materials.[71] The overall attenuation of gamma rays in matter is quantified by the linear attenuation coefficient , which sums the individual process coefficients: , where , , and represent the photoelectric, Compton scattering, and pair production contributions, respectively.[69] For material-independent comparisons, the mass attenuation coefficient (with the density) is commonly used, revealing how interaction probabilities scale with atomic composition across different substances.[69]Penetration and Shielding

Gamma rays exhibit high penetration power due to their electromagnetic nature and lack of charge, allowing them to traverse materials with minimal interaction compared to charged particles. The propagation of gamma ray intensity through a homogeneous material follows the Beer-Lambert law, expressed as , where is the transmitted intensity, is the initial intensity, is the linear attenuation coefficient (dependent on the gamma ray energy and material properties), and is the material thickness. This exponential attenuation arises from the probabilistic interactions of gamma rays with matter, primarily through photoelectric absorption, Compton scattering, and pair production, which collectively determine .[72] A practical measure of penetration is the half-value layer (HVL), the thickness of material required to reduce the gamma ray intensity to half its original value, given by .[73] For instance, at 1 MeV energy, the HVL in lead is approximately 0.87 cm, meaning successive layers of this thickness halve the intensity each time.[74] Shielding design often relies on multiple HVLs to achieve desired dose reductions; for example, about 3 cm of lead attenuates 1 MeV gamma rays to one-tenth of their initial intensity, calculated as cm using cm⁻¹ for lead at this energy.[74] The effectiveness of shielding materials varies with gamma ray energy and atomic number (Z) of the absorber. High-Z materials like lead (Z=82) are preferred for lower-energy gamma rays (below ~1 MeV), where photoelectric absorption dominates, due to their high density (11.35 g/cm³) and electron density that enhance interaction probability.[73] For higher energies (above ~3 MeV), where pair production becomes significant, high-Z materials remain effective, but lower-cost, lower-Z options like concrete (density ~2.3–2.4 g/cm³) or water are often used in bulk for economic and structural reasons, requiring greater thicknesses—typically 10–20 times that of lead for equivalent attenuation.[75] In nuclear reactor shielding, for example, concrete walls several meters thick surround the core to attenuate gamma rays from fission products, providing both radiation protection and structural support while minimizing secondary neutron interactions.[73] A key consideration in shielding design is the build-up factor, a multiplier greater than 1 that accounts for the increased effective dose from scattered (secondary) gamma rays produced within the shield, which can travel forward and contribute to the transmitted radiation.[76] Build-up factors depend on gamma energy, shield material, thickness (in mean free paths), and geometry, often requiring Monte Carlo simulations or tabulated data for accurate calculation; for broad-beam geometries, they can increase the apparent transmission by factors of 2–10 or more in thick shields.[73] Angular dependence further complicates design, as oblique incidence reduces effective thickness (via the secant of the angle), necessitating additional shielding margins in applications like reactor vaults or medical linear accelerators.[76]Comparison to Other Radiation Types

Gamma rays are high-energy electromagnetic radiation originating primarily from nuclear processes, such as radioactive decay or nuclear reactions within atomic nuclei.[11] In contrast, X-rays arise from atomic processes outside the nucleus, typically involving the deceleration of high-speed electrons or transitions between electron shells in atoms.[11] While both are photons with overlapping energy ranges—X-rays generally spanning 0.1 to 100 keV and gamma rays exceeding 100 keV—there is no strict energy boundary, and the distinction is largely conventional based on origin rather than fundamental physical differences.[7] Gamma rays are produced through nuclear de-excitation or particle capture in the nucleus, whereas X-rays result from electron bombardment in devices like X-ray tubes or synchrotron sources.[77] This nuclear versus extranuclear origin clarifies a common misconception that gamma rays are always higher energy than X-rays, as some nuclear emissions fall in the X-ray range but are still classified as gamma due to their source.[78] Unlike alpha and beta particles, which are particulate radiation with mass and charge, gamma rays are massless photons that travel at the speed of light and interact with matter primarily through electromagnetic processes like the photoelectric effect or Compton scattering.[3] Alpha particles, consisting of helium nuclei with a +2 charge and approximately 4 atomic mass units, have very low penetration, traveling only a few centimeters in air due to strong ionization from their high charge density.[6] Beta particles, which are high-energy electrons (-1 charge, negligible mass) or positrons (+1 charge), penetrate farther—up to several meters in air—but are still stopped by thin metal or plastic, unlike gamma rays that can traverse hundreds of meters in air before significant attenuation.[79] This electromagnetic nature gives gamma rays far greater range and penetrating power compared to the charged particulate alpha and beta radiation, which lose energy rapidly through direct collisions.[3] Gamma rays differ markedly from ultraviolet (UV) and visible light, which are lower-energy electromagnetic waves in the non-ionizing portion of the spectrum, typically below 10 eV for visible light and up to about 100 eV for UV.[80] While UV radiation can cause photochemical reactions and partial ionization in outer electron shells, visible light primarily excites electrons without removing them, lacking the capability to ionize atoms deeply.[81] In comparison, gamma rays' energies exceeding 100 keV enable strong ionization by ejecting inner-shell electrons, allowing penetration through materials opaque to UV and visible light, such as metals or human tissue.[3] This ionizing potential underscores gamma rays' position as hazardous high-energy radiation, far beyond the surface-level effects of non-ionizing UV or visible photons.[80]| Radiation Type | Typical Energy Range | Charge | Mass | Primary Interaction Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gamma rays | >100 keV | 0 | 0 | Electromagnetic (photoelectric, Compton scattering, pair production)[3] |

| X-rays | 0.1–100 keV | 0 | 0 | Electromagnetic (similar to gamma, but lower energy)[7] |

| Alpha particles | 4–9 MeV | +2 | ~4 u | Direct ionization via Coulomb interactions[6] |

| Beta particles | Up to a few MeV | -1 or +1 | Negligible (electron mass) | Ionization and bremsstrahlung radiation[79] |