Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ultraviolet

View on Wikipedia

Ultraviolet radiation, also known as simply UV, is electromagnetic radiation of wavelengths of 10–400 nanometers, shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiation is present in sunlight and constitutes about 10% of the total electromagnetic radiation output from the Sun. It is also produced by electric arcs, Cherenkov radiation, and specialized lights, such as mercury-vapor lamps, tanning lamps, and black lights.

The photons of ultraviolet have greater energy than those of visible light, from about 3.1 to 12 electron volts, around the minimum energy required to ionize atoms.[1]: 25–26 Although long-wavelength ultraviolet is not considered an ionizing radiation[2] because its photons lack sufficient energy, it can induce chemical reactions and cause many substances to glow or fluoresce. Many practical applications, including chemical and biological effects, are derived from the way that UV radiation can interact with organic molecules. These interactions can involve exciting orbital electrons to higher energy states in molecules potentially breaking chemical bonds. In contrast, the main effect of longer wavelength radiation is to excite vibrational or rotational states of these molecules, increasing their temperature.[1]: 28 Short-wave ultraviolet light is ionizing radiation.[2] Consequently, short-wave UV damages DNA and sterilizes surfaces with which it comes into contact.

For humans, suntan and sunburn are familiar effects of exposure of the skin to UV, along with an increased risk of skin cancer. The amount of UV radiation produced by the Sun means that the Earth would not be able to sustain life on dry land if most of that light were not filtered out by the atmosphere.[3] More energetic, shorter-wavelength "extreme" UV below 121 nm ionizes air so strongly that it is absorbed before it reaches the ground.[4] However, UV (specifically, UVB) is also responsible for the formation of vitamin D in most land vertebrates, including humans.[5] The UV spectrum, thus, has effects both beneficial and detrimental to life.

The lower wavelength limit of the visible spectrum is conventionally taken as 400 nm. Although ultraviolet rays are not generally visible to humans, 400 nm is not a sharp cutoff, with shorter and shorter wavelengths becoming less and less visible in this range.[6] Insects, birds, and some mammals can see near-UV (NUV), i.e., somewhat shorter wavelengths than what humans can see.[7]

Visibility

[edit]Humans generally cannot use ultraviolet rays for vision. The lens of the human eye and surgically implanted lens produced since 1986 blocks most radiation in the near UV wavelength range of 300–400 nm; shorter wavelengths are blocked by the cornea.[8] Humans also lack color receptor adaptations for ultraviolet rays. The photoreceptors of the retina are sensitive to near-UV but the lens does not focus this light, causing UV light bulbs to look fuzzy.[9][10] People lacking a lens (a condition known as aphakia) perceive near-UV as whitish-blue or whitish-violet.[6] Near-UV radiation is visible to insects, some mammals, and some birds. Birds have a fourth color receptor for ultraviolet rays; this, coupled with eye structures that transmit more UV gives smaller birds "true" UV vision.[11][12]

History and discovery

[edit]"Ultraviolet" means "beyond violet" (from Latin ultra, "beyond"), violet being the color of the highest frequencies of visible light. Ultraviolet has a higher frequency (thus a shorter wavelength) than violet light.

UV radiation was discovered in February 1801 when the German physicist Johann Wilhelm Ritter observed that invisible rays just beyond the violet end of the visible spectrum darkened silver chloride-soaked paper more quickly than violet light itself. He announced the discovery in a very brief letter to the Annalen der Physik[13][14] and later called them "(de-)oxidizing rays" (German: de-oxidierende Strahlen) to emphasize chemical reactivity and to distinguish them from "heat rays", discovered the previous year at the other end of the visible spectrum. The simpler term "chemical rays" was adopted soon afterwards, and remained popular throughout the 19th century, although some said that this radiation was entirely different from light (notably John William Draper, who named them "tithonic rays"[15][16]). The terms "chemical rays" and "heat rays" were eventually dropped in favor of ultraviolet and infrared radiation, respectively.[17][18] In 1878, the sterilizing effect of short-wavelength light by killing bacteria was discovered. By 1903, the most effective wavelengths were known to be around 250 nm. In 1960, the effect of ultraviolet radiation on DNA was established.[19]

The discovery of the ultraviolet radiation with wavelengths below 200 nm, named "vacuum ultraviolet" because it is strongly absorbed by the oxygen in air, was made in 1893 by German physicist Victor Schumann.[20] The division of UV into UVA, UVB, and UVC was decided "unanimously" by a committee of the Second International Congress on Light on August 17th, 1932, at the Castle of Christiansborg in Copenhagen.[21]

Subtypes

[edit]The electromagnetic spectrum of ultraviolet radiation (UVR), defined most broadly as 10–400 nanometers, can be subdivided into a number of ranges recommended by the ISO standard ISO 21348:[22]

| Name | Photon energy (eV, aJ) | Notes/alternative names | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abbreviation | Wavelength (nm) | ||

| Ultraviolet A | 3.10–3.94 0.497–0.631 |

Long-wave UV, blacklight, not absorbed by the ozone layer: soft UV. | |

| UVA | 315–400 | ||

| Ultraviolet B | 3.94–4.43 0.631–0.710 |

Medium-wave UV, mostly absorbed by the ozone layer: intermediate UV; Dorno radiation. | |

| UVB | 280–315 | ||

| Ultraviolet C | 4.43–12.4 0.710–1.987 |

Short-wave UV, germicidal UV, ionizing radiation at shorter wavelengths, completely absorbed by the ozone layer and atmosphere: hard UV. | |

| UVC | 100–280 | ||

| Near ultraviolet | 3.10–4.13 0.497–0.662 |

Visible to birds, insects, and fish. | |

| NUV | 300–400 | ||

| Middle ultraviolet | 4.13–6.20 0.662–0.993 |

||

| MUV | 200–300 | ||

| Far ultraviolet | 6.20–10.16 0.993–1.628 |

Ionizing radiation at shorter wavelengths. | |

| FUV | 122–200 | ||

| Hydrogen Lyman-alpha |

10.16–10.25 1.628–1.642 |

Spectral line at 121.6 nm, 10.20 eV. | |

| H Lyman‑α | 121–122 | ||

| Extreme ultraviolet | 10.25–124 1.642–19.867 |

Entirely ionizing radiation by some definitions; completely absorbed by the atmosphere. | |

| EUV | 10–121 | ||

| Far-UVC | 5.28–6.20 0.846–0.993 |

Germicidal but strongly absorbed by outer skin layers, so does not reach living tissue. | |

| 200–235 | |||

| Vacuum ultraviolet | 6.20–124 0.993–19.867 |

Strongly absorbed by atmospheric oxygen, though 150–200 nm wavelengths can propagate through nitrogen. | |

| VUV | 10–200 | ||

Several solid-state and vacuum devices have been explored for use in different parts of the UV spectrum. Many approaches seek to adapt visible light-sensing devices, but these can suffer from unwanted response to visible light and various instabilities. Ultraviolet can be detected by suitable photodiodes and photocathodes, which can be tailored to be sensitive to different parts of the UV spectrum. Sensitive UV photomultipliers are available. Spectrometers and radiometers are made for measurement of UV radiation. Silicon detectors are used across the spectrum.[23]

Vacuum ultraviolet

[edit]Vacuum UV, or VUV, wavelengths (shorter than 200 nm) are strongly absorbed by molecular oxygen in the air, though the longer wavelengths around 150–200 nm can propagate through nitrogen. Scientific instruments can, therefore, use this spectral range by operating in an oxygen-free atmosphere (pure nitrogen, or argon for shorter wavelengths), without the need for costly vacuum chambers. Significant examples include 193-nm photolithography equipment (for semiconductor manufacturing) and circular dichroism spectrometers.[24]

Technology for VUV instrumentation was largely driven by solar astronomy for many decades. While optics can be used to remove unwanted visible light that contaminates the VUV, in general, detectors can be limited by their response to non-VUV radiation, and the development of solar-blind devices has been an important area of research. Wide-gap solid-state devices or vacuum devices with high-cutoff photocathodes can be attractive compared to silicon diodes.

Extreme ultraviolet

[edit]Extreme UV (EUV or sometimes XUV) is characterized by a transition in the physics of interaction with matter. Wavelengths longer than about 30 nm interact mainly with the outer valence electrons of atoms, while wavelengths shorter than that interact mainly with inner-shell electrons and nuclei. The long end of the EUV spectrum is set by a prominent He+ spectral line at 30.4 nm. EUV is strongly absorbed by most known materials, but synthesizing multilayer optics that reflect up to about 50% of EUV radiation at normal incidence is possible. This technology was pioneered by the NIXT and MSSTA sounding rockets in the 1990s, and it has been used to make telescopes for solar imaging. See also the Extreme Ultraviolet Explorer satellite.[citation needed]

Hard and soft ultraviolet

[edit]Some sources use the distinction of "hard UV" and "soft UV". For instance, in the case of astrophysics, the boundary may be at the Lyman limit (wavelength 91.2 nm, the energy needed to ionise a hydrogen atom from its ground state), with "hard UV" being more energetic;[25] the same terms may also be used in other fields, such as cosmetology, optoelectronic, etc. The numerical values of the boundary between hard/soft, even within similar scientific fields, do not necessarily coincide; for example, one applied-physics publication used a boundary of 190 nm between hard and soft UV regions.[26]

Solar ultraviolet

[edit]

Very hot objects emit UV radiation (see black-body radiation). The Sun emits ultraviolet radiation at all wavelengths, including the extreme ultraviolet where it crosses into X-rays at 10 nm. Extremely hot stars (such as O- and B-type) emit proportionally more UV radiation than the Sun. Sunlight in space at the top of Earth's atmosphere (see solar constant) is composed of about 50% infrared light, 40% visible light, and 10% ultraviolet light, for a total intensity of about 1400 W/m2 in vacuum.[27]

The atmosphere blocks about 77% of the Sun's UV, when the Sun is highest in the sky (at zenith), with absorption increasing at shorter UV wavelengths. At ground level with the sun at zenith, sunlight is 44% visible light, 3% ultraviolet, and the remainder infrared.[28][29] Of the ultraviolet radiation that reaches the Earth's surface, more than 95% is the longer wavelengths of UVA, with the small remainder UVB. Almost no UVC reaches the Earth's surface.[30] The fraction of UVA and UVB which remains in UV radiation after passing through the atmosphere is heavily dependent on cloud cover and atmospheric conditions. On "partly cloudy" days, patches of blue sky showing between clouds are also sources of (scattered) UVA and UVB, which are produced by Rayleigh scattering in the same way as the visible blue light from those parts of the sky. UVB also plays a major role in plant development, as it affects most of the plant hormones.[31] During total overcast, the amount of absorption due to clouds is heavily dependent on the thickness of the clouds and latitude, with no clear measurements correlating specific thickness and absorption of UVA and UVB.[32]

The shorter bands of UVC, as well as even more-energetic UV radiation produced by the Sun, are absorbed by oxygen and generate the ozone in the ozone layer when single oxygen atoms produced by UV photolysis of dioxygen react with more dioxygen. The ozone layer is especially important in blocking most UVB and the remaining part of UVC not already blocked by ordinary oxygen in air.[citation needed]

Blockers, absorbers, and windows

[edit]Ultraviolet absorbers are molecules used in organic materials (polymers, paints, etc.) to absorb UV radiation to reduce the UV degradation (photo-oxidation) of a material. The absorbers can themselves degrade over time, so monitoring of absorber levels in weathered materials is necessary.[citation needed]

In sunscreen, ingredients that absorb UVA/UVB rays, such as avobenzone, oxybenzone[33] and octyl methoxycinnamate, are organic chemical absorbers or "blockers". They are contrasted with inorganic absorbers/"blockers" of UV radiation such as titanium dioxide and zinc oxide.[34]

For clothing, the ultraviolet protection factor (UPF) represents the ratio of sunburn-causing UV without and with the protection of the fabric, similar to sun protection factor (SPF) ratings for sunscreen.[citation needed] Standard summer fabrics have UPFs around 6, which means that about 20% of UV will pass through.[citation needed]

Suspended nanoparticles in stained-glass prevent UV rays from causing chemical reactions that change image colors.[citation needed] A set of stained-glass color-reference chips is planned to be used to calibrate the color cameras for the 2019 ESA Mars rover mission, since they will remain unfaded by the high level of UV present at the surface of Mars.[citation needed]

Common soda–lime glass, such as window glass, is partially transparent to UVA, but is opaque to shorter wavelengths, passing about 90% of the light above 350 nm, but blocking over 90% of the light below 300 nm.[35][36][37] A study found that car windows allow 3–4% of ambient UV to pass through, especially if the UV was greater than 380 nm.[38] Other types of car windows can reduce transmission of UV that is greater than 335 nm.[38] Fused quartz, depending on quality, can be transparent even to vacuum UV wavelengths. Crystalline quartz and some crystals such as CaF2 and MgF2 transmit well down to 150 nm or 160 nm wavelengths.[39]

Wood's glass is a deep violet-blue barium-sodium silicate glass with about 9% nickel(II) oxide developed during World War I to block visible light for covert communications. It allows both infrared daylight and ultraviolet night-time communications by being transparent between 320 nm and 400 nm and also the longer infrared and just-barely-visible red wavelengths. Its maximum UV transmission is at 365 nm, one of the wavelengths of mercury lamps.[40]

Artificial sources

[edit]"Black lights"

[edit]A black light lamp emits long-wave UVA radiation and little visible light. Fluorescent black light lamps work similarly to other fluorescent lamps, but use a phosphor on the inner tube surface which emits UVA radiation instead of visible light. Some lamps use a deep-bluish-purple Wood's glass optical filter that blocks almost all visible light with wavelengths longer than 400 nanometers.[41] The purple glow given off by these tubes is not the ultraviolet itself, but visible purple light from mercury's 404 nm spectral line which escapes being filtered out by the coating. Other black lights use plain glass instead of the more expensive Wood's glass, so they appear light-blue to the eye when operating.[citation needed]

Incandescent black lights are also produced, using a filter coating on the envelope of an incandescent bulb that absorbs visible light (see section below). These are cheaper but very inefficient, emitting only a small fraction of a percent of their power as UV. Mercury-vapor black lights in ratings up to 1 kW with UV-emitting phosphor and an envelope of Wood's glass are used for theatrical and concert displays.[citation needed]

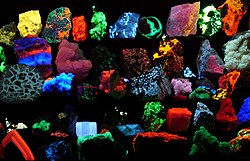

Black lights are used in applications in which extraneous visible light must be minimized; mainly to observe fluorescence, the colored glow that many substances give off when exposed to UV light. UVA / UVB emitting bulbs are also sold for other special purposes, such as tanning lamps and reptile-husbandry.[citation needed]

Short-wave ultraviolet lamps

[edit]Shortwave UV lamps are made using a fluorescent lamp tube with no phosphor coating, composed of fused quartz or vycor, since ordinary glass absorbs UVC. These lamps emit ultraviolet light with two peaks in the UVC band at 253.7 nm and 185 nm due to the mercury within the lamp, as well as some visible light. From 85% to 90% of the UV produced by these lamps is at 253.7 nm, whereas only 5–10% is at 185 nm.[42] The fused quartz tube passes the 253.7 nm radiation but blocks the 185 nm wavelength. Such tubes have two or three times the UVC power of a regular fluorescent lamp tube. These low-pressure lamps have a typical efficiency of approximately 30–40%, meaning that for every 100 watts of electricity consumed by the lamp, they will produce approximately 30–40 watts of total UV output. They also emit bluish-white visible light, due to mercury's other spectral lines. These "germicidal" lamps are used extensively for disinfection of surfaces in laboratories and food-processing industries.[43]

Incandescent lamps

[edit]'Black light' incandescent lamps are also made from an incandescent light bulb with a filter coating which absorbs most visible light. Halogen lamps with fused quartz envelopes are used as inexpensive UV light sources in the near UV range, from 400 to 300 nm, in some scientific instruments. Due to its black-body spectrum a filament light bulb is a very inefficient ultraviolet source, emitting only a fraction of a percent of its energy as UV, as explained by the black body spectrum.

Gas-discharge lamps

[edit]Specialized UV gas-discharge lamps containing different gases produce UV radiation at particular spectral lines for scientific purposes. Argon and deuterium arc lamps are often used as stable sources, either windowless or with various windows such as magnesium fluoride.[44] These are often the emitting sources in UV spectroscopy equipment for chemical analysis.[citation needed]

Other UV sources with more continuous emission spectra include xenon arc lamps (commonly used as sunlight simulators), deuterium arc lamps, mercury-xenon arc lamps, and metal-halide arc lamps.[citation needed]

The excimer lamp, a UV source developed in the early 2000s, is seeing increasing use in scientific fields. It has the advantages of high-intensity, high efficiency, and operation at a variety of wavelength bands into the vacuum ultraviolet.[citation needed]

Ultraviolet LEDs

[edit]

Light-emitting diodes (LEDs) can be manufactured to emit radiation in the ultraviolet range. In 2019, following significant advances over the preceding five years, UVA LEDs of 365 nm and longer wavelength were available, with efficiencies of 50% at 1.0 W output. Currently, the most common types of UV LEDs are in 395 nm and 365 nm wavelengths, both of which are in the UVA spectrum. The rated wavelength is the peak wavelength that the LEDs put out, but light at both higher and lower wavelengths are present.[45]

The cheaper and more common 395 nm UV LEDs are much closer to the visible spectrum, and give off a purple color. Other UV LEDs deeper into the spectrum do not emit as much visible light.[46] LEDs are used for applications such as UV curing applications, charging glow-in-the-dark objects such as paintings or toys, and lights for detecting counterfeit money and bodily fluids. UV LEDs are also used in digital print applications and inert UV curing environments. As technological advances beginning in the early 2000s have improved their output and efficiency, they have become increasingly viable alternatives to more traditional UV lamps for use in UV curing applications, and the development of new UV LED curing systems for higher-intensity applications is a major subject of research in the field of UV curing technology.[47]

UVC LEDs are developing rapidly, but may require testing to verify effective disinfection. Citations for large-area disinfection are for non-LED UV sources[48] known as germicidal lamps.[49] Also, they are used as line sources to replace deuterium lamps in liquid chromatography instruments.[50]

Ultraviolet lasers

[edit]Gas lasers, laser diodes, and solid-state lasers can be manufactured to emit ultraviolet rays, and lasers are available that cover the entire UV range. The nitrogen gas laser uses electronic excitation of nitrogen molecules to emit a beam that is mostly UV. The strongest ultraviolet lines are at 337.1 nm and 357.6 nm in wavelength. Another type of high-power gas lasers are excimer lasers. They are widely used lasers emitting in ultraviolet and vacuum ultraviolet wavelength ranges. Presently, UV argon-fluoride excimer lasers operating at 193 nm are routinely used in integrated circuit production by photolithography. The current[timeframe?] wavelength limit of production of coherent UV is about 126 nm, characteristic of the Ar2* excimer laser.[citation needed]

Direct UV-emitting laser diodes are available at 375 nm.[51] UV diode-pumped solid state lasers have been demonstrated using cerium-doped lithium strontium aluminum fluoride crystals (Ce:LiSAF), a process developed in the 1990s at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.[52] Wavelengths shorter than 325 nm are commercially generated in diode-pumped solid-state lasers. Ultraviolet lasers can also be made by applying frequency conversion to lower-frequency lasers.[53]

Ultraviolet lasers have applications in industry (laser engraving), medicine (dermatology, and keratectomy), chemistry (MALDI), free-air secure communications, computing (optical storage), and manufacture of integrated circuits.[54][55]

Tunable vacuum ultraviolet (VUV)

[edit]The vacuum ultraviolet (V‑UV) band (100–200 nm) can be generated by non-linear 4 wave mixing in gases by sum or difference frequency mixing of 2 or more longer wavelength lasers. The generation is generally done in gasses (e.g. krypton, hydrogen which are two-photon resonant near 193 nm)[56] or metal vapors (e.g. magnesium). By making one of the lasers tunable, the V‑UV can be tuned. If one of the lasers is resonant with a transition in the gas or vapor then the V‑UV production is intensified. However, resonances also generate wavelength dispersion, and thus the phase matching can limit the tunable range of the 4 wave mixing. Difference frequency mixing (i.e., f1 + f2 − f3) has an advantage over sum frequency mixing because the phase matching can provide greater tuning.[56]

In particular, difference frequency mixing two photons of an ArF (193 nm) excimer laser with a tunable visible or near IR laser in hydrogen or krypton provides resonantly enhanced tunable V‑UV covering from 100 nm to 200 nm.[56] Practically, the lack of suitable gas / vapor cell window materials above the lithium fluoride cut-off wavelength limit the tuning range to longer than about 110 nm. Tunable V‑UV wavelengths down to 75 nm was achieved using window-free configurations.[57]

Plasma and synchrotron sources of extreme UV

[edit]Lasers have been used to indirectly generate non-coherent extreme UV (E‑UV) radiation at 13.5 nm for extreme ultraviolet lithography. The E‑UV is not emitted by the laser, but rather by electron transitions in an extremely hot tin or xenon plasma, which is excited by an excimer laser.[58] This technique does not require a synchrotron, yet can produce UV at the edge of the X‑ray spectrum. Synchrotron light sources can also produce all wavelengths of UV, including those at the boundary of the UV and X‑ray spectra at 10 nm.[citation needed]

Human health-related effects

[edit]The impact of ultraviolet radiation on human health has implications for the risks and benefits of sun exposure and is also implicated in issues such as fluorescent lamps and health. Getting too much sun exposure can be harmful, but in moderation, sun exposure is beneficial.[59]

Beneficial effects

[edit]UV (specifically, UVB) causes the body to produce vitamin D,[60] which is essential for life. Humans need some UV radiation to maintain adequate vitamin D levels. According to the World Health Organization:[61]

There is no doubt that a little sunlight is good for you! But 5–15 minutes of casual sun exposure of hands, face and arms two to three times a week during the summer months is sufficient to keep your vitamin D levels high.

Vitamin D can also be obtained from food and supplementation.[62] Excess sun exposure produces harmful effects, however.[61]

Skin conditions

[edit]UV rays also treat certain skin conditions. Modern phototherapy has been used to successfully treat psoriasis, eczema, jaundice, vitiligo, atopic dermatitis, and localized scleroderma.[63][64] In addition, UV radiation, in particular UVB radiation, has been shown to induce cell cycle arrest in keratinocytes, the most common type of skin cell.[65] As such, sunlight therapy can be a candidate for treatment of conditions such as psoriasis and exfoliative cheilitis, conditions in which skin cells divide more rapidly than usual or necessary.[66]

Harmful effects

[edit]

In humans, excessive exposure to UV radiation can result in acute and chronic harmful effects on the eye's dioptric system and retina. The risk is elevated at high altitudes and people living in high latitude areas where snow covers the ground right into early summer and sun positions even at zenith are low, are particularly at risk.[67] Skin, the circadian system, and the immune system can also be affected.[68]

The differential effects of various wavelengths of light on the human cornea and skin are sometimes called the "erythemal action spectrum".[69] The action spectrum shows that UVA does not cause immediate reaction, but rather UV begins to cause photokeratitis and skin redness (with lighter skinned individuals being more sensitive) at wavelengths starting near the beginning of the UVB band at 315 nm, and rapidly increasing to 300 nm. The skin and eyes are most sensitive to damage by UV at 265–275 nm, which is in the lower UVC band. At still shorter wavelengths of UV, damage continues to happen, but the overt effects are not as great with so little penetrating the atmosphere. The WHO-standard ultraviolet index is a widely publicized measurement of total strength of UV wavelengths that cause sunburn on human skin, by weighting UV exposure for action spectrum effects at a given time and location. This standard shows that most sunburn happens due to UV at wavelengths near the boundary of the UVA and UVB bands.[citation needed]

Skin damage

[edit]

Overexposure to UVB radiation not only can cause sunburn but also some forms of skin cancer. However, the degree of redness and eye irritation (which are largely not caused by UVA) do not predict the long-term effects of UV, although they do mirror the direct damage of DNA by ultraviolet.[70]

All bands of UV radiation damage collagen fibers and accelerate aging of the skin. Both UVA and UVB destroy vitamin A in skin, which may cause further damage.[71]

UVB radiation can cause direct DNA damage.[72] This cancer connection is one reason for concern about ozone depletion and the ozone hole.

The most deadly form of skin cancer, melanoma, is mostly caused by DNA damage independent from UVA radiation. This can be seen from the absence of a direct UV signature mutation in 92% of all melanoma.[73] Occasional overexposure and sunburn are probably greater risk factors for melanoma than long-term moderate exposure.[74] UVC is the highest-energy, most-dangerous type of ultraviolet radiation, and causes adverse effects that can variously be mutagenic or carcinogenic.[75]

In the past, UVA was considered not harmful or less harmful than UVB, but today it is known to contribute to skin cancer via indirect DNA damage (free radicals such as reactive oxygen species).[76] UVA can generate highly reactive chemical intermediates, such as hydroxyl and oxygen radicals, which in turn can damage DNA. The DNA damage caused indirectly to skin by UVA consists mostly of single-strand breaks in DNA, while the damage caused by UVB includes direct formation of thymine dimers or cytosine dimers and double-strand DNA breakage.[77] UVA is immunosuppressive for the entire body (accounting for a large part of the immunosuppressive effects of sunlight exposure), and is mutagenic for basal cell keratinocytes in skin.[78]

UVB photons can cause direct DNA damage. UVB radiation excites DNA molecules in skin cells, causing aberrant covalent bonds to form between adjacent pyrimidine bases, producing a dimer. Most UV-induced pyrimidine dimers in DNA are removed by the process known as nucleotide excision repair that employs about 30 different proteins.[72] Those pyrimidine dimers that escape this repair process can induce a form of programmed cell death (apoptosis) or can cause DNA replication errors leading to mutation.[citation needed]

UVB damages mRNA[79] This triggers a fast pathway that leads to inflammation of the skin and sunburn. mRNA damage initially triggers a response in ribosomes though a protein known as ZAK-alpha in a ribotoxic stress response. This response acts as a cell surveillance system. Following this detection of RNA damage leads to inflammatory signaling and recruitment of immune cells. This, not DNA damage (which is slower to detect) results in UVB skin inflammation and acute sunburn.[80]

As a defense against UV radiation, the amount of the brown pigment melanin in the skin increases when exposed to moderate (depending on skin type) levels of radiation; this is commonly known as a sun tan. The purpose of melanin is to absorb UV radiation and dissipate the energy as harmless heat, protecting the skin against both direct and indirect DNA damage from the UV. UVA gives a quick tan that lasts for days by oxidizing melanin that was already present and triggers the release of the melanin from melanocytes. UVB yields a tan that takes roughly 2 days to develop because it stimulates the body to produce more melanin.[citation needed]

Sunscreen safety debate

[edit]

Medical organizations recommend that patients protect themselves from UV radiation by using sunscreen. Five sunscreen ingredients have been shown to protect mice against skin tumors. However, some sunscreen chemicals produce potentially harmful substances if they are illuminated while in contact with living cells.[81][82] The amount of sunscreen that penetrates into the lower layers of the skin may be large enough to cause damage.[83]

Sunscreen reduces the direct DNA damage that causes sunburn, by blocking UVB, and the usual SPF rating indicates how effectively this radiation is blocked. SPF is, therefore, also called UVB-PF, for "UVB protection factor".[84] This rating, however, offers no data about important protection against UVA,[85] which does not primarily cause sunburn but is still harmful, since it causes indirect DNA damage and is also considered carcinogenic. Several studies suggest that the absence of UVA filters may be the cause of the higher incidence of melanoma found in sunscreen users compared to non-users.[86][87][88][89][90] Some sunscreen lotions contain titanium dioxide, zinc oxide, and avobenzone, which help protect against UVA rays.

The photochemical properties of melanin make it an excellent photoprotectant. However, sunscreen chemicals cannot dissipate the energy of the excited state as efficiently as melanin and therefore, if sunscreen ingredients penetrate into the lower layers of the skin, the amount of reactive oxygen species may be increased.[91][81][82][92] The amount of sunscreen that penetrates through the stratum corneum may or may not be large enough to cause damage.

In an experiment by Hanson et al. that was published in 2006, the amount of harmful reactive oxygen species (ROS) was measured in untreated and in sunscreen treated skin. In the first 20 minutes, the film of sunscreen had a protective effect and the number of ROS species was smaller. After 60 minutes, however, the amount of absorbed sunscreen was so high that the amount of ROS was higher in the sunscreen-treated skin than in the untreated skin.[91] The study indicates that sunscreen must be reapplied within 2 hours in order to prevent UV light from penetrating to sunscreen-infused live skin cells.[91]

Aggravation of certain skin conditions

[edit]Ultraviolet radiation can aggravate several skin conditions and diseases, including[93] systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren's syndrome, Sinear Usher syndrome, rosacea, dermatomyositis, Darier's disease, Kindler–Weary syndrome and Porokeratosis.[94]

Eye damage

[edit]

The eye is most sensitive to damage by UV in the lower UVC band at 265–275 nm. Radiation of this wavelength is almost absent from sunlight at the surface of the Earth but is emitted by artificial sources such as the electrical arcs employed in arc welding. Unprotected exposure to these sources can cause "welder's flash" or "arc eye" (photokeratitis) and can lead to cataracts, pterygium and pinguecula formation. To a lesser extent, UVB in sunlight from 310 to 280 nm also causes photokeratitis ("snow blindness"), and the cornea, the lens, and the retina can be damaged.[95]

Protective eyewear is beneficial to those exposed to ultraviolet radiation. Since light can reach the eyes from the sides, full-coverage eye protection is usually warranted if there is an increased risk of exposure, as in high-altitude mountaineering. Mountaineers are exposed to higher-than-ordinary levels of UV radiation, both because there is less atmospheric filtering and because of reflection from snow and ice.[96][97] Ordinary, untreated eyeglasses give some protection. Most plastic lenses give more protection than glass lenses, because, as noted above, glass is transparent to UVA and the common acrylic plastic used for lenses is less so. Some plastic lens materials, such as polycarbonate, inherently block most UV.[98]

Degradation of polymers, pigments and dyes

[edit]

UV degradation is one form of polymer degradation that affects plastics exposed to sunlight. The problem appears as discoloration or fading, cracking, loss of strength or disintegration. The effects of attack increase with exposure time and sunlight intensity. The addition of UV absorbers inhibits the effect.

Sensitive polymers include thermoplastics and speciality fibers like aramids. UV absorption leads to chain degradation and loss of strength at sensitive points in the chain structure. Aramid rope must be shielded with a sheath of thermoplastic if it is to retain its strength.[citation needed]

Many pigments and dyes absorb UV and change colour, so paintings and textiles may need extra protection both from sunlight and fluorescent lamps, two common sources of UV radiation. Window glass absorbs some harmful UV, but valuable artifacts need extra shielding. Many museums place black curtains over watercolour paintings and ancient textiles, for example. Since watercolours can have very low pigment levels, they need extra protection from UV. Various forms of picture framing glass, including acrylics (plexiglass), laminates, and coatings, offer different degrees of UV (and visible light) protection.[99]

Applications

[edit]Because of its ability to cause chemical reactions and excite fluorescence in materials, ultraviolet radiation has a number of applications. The following table[100] gives some uses of specific wavelength bands in the UV spectrum.

- 13.5 nm: Extreme ultraviolet lithography

- 30–200 nm: Photoionization, ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy, standard integrated circuit manufacture by photolithography

- 230–365 nm: UV-ID, label tracking, barcodes

- 230–400 nm: Optical sensors, various instrumentation

- 240–280 nm: Disinfection, decontamination of surfaces and water (DNA absorption has a peak at 260 nm), germicidal lamps[49]

- 200–400 nm: Forensic analysis, drug detection

- 270–360 nm: Protein analysis, DNA sequencing, drug discovery

- 280–400 nm: Medical imaging of cells

- 300–320 nm: Light therapy in medicine

- 300–365 nm: Curing of polymers and printer inks

- 350–370 nm: Bug zappers (flies are most attracted to light at 365 nm)[101]

Photography

[edit]

Photographic film responds to ultraviolet radiation but the glass lenses of cameras usually block radiation shorter than 350 nm. Slightly yellow UV-blocking filters are often used for outdoor photography to prevent unwanted bluing and overexposure by UV rays. For photography in the near UV, special filters may be used. Photography with wavelengths shorter than 350 nm requires special quartz lenses which do not absorb the radiation. Digital cameras sensors may have internal filters that block UV to improve color rendition accuracy. Sometimes these internal filters can be removed, or they may be absent, and an external visible-light filter prepares the camera for near-UV photography. A few cameras are designed for use in the UV.[102]

Photography by reflected ultraviolet radiation is useful for medical, scientific, and forensic investigations, in applications as widespread as detecting bruising of skin, alterations of documents, or restoration work on paintings. Photography of the fluorescence produced by ultraviolet illumination uses visible wavelengths of light.[citation needed]

In ultraviolet astronomy, measurements are used to discern the chemical composition of the interstellar medium, and the temperature and composition of stars. Because the ozone layer blocks many UV frequencies from reaching telescopes on the surface of the Earth, most UV observations are made from space.[103]

Electrical and electronics industry

[edit]Corona discharge on electrical apparatus can be detected by its ultraviolet emissions. Corona causes degradation of electrical insulation and emission of ozone and nitrogen oxide.[104]

EPROMs (Erasable Programmable Read-Only Memory) are erased by exposure to UV radiation. These modules have a transparent (quartz) window on the top of the chip that allows the UV radiation in.

Fluorescent dye uses

[edit]Colorless fluorescent dyes that emit blue light under UV are added as optical brighteners to paper and fabrics. The blue light emitted by these agents counteracts yellow tints that may be present and causes the colors and whites to appear whiter or more brightly colored.

UV fluorescent dyes that glow in the primary colors are used in paints, papers, and textiles either to enhance color under daylight illumination or to provide special effects when lit with UV lamps. Blacklight paints that contain dyes that glow under UV are used in a number of art and aesthetic applications.[citation needed]

To help prevent counterfeiting of currency, or forgery of important documents such as driver's licenses and passports, the paper may include a UV watermark or fluorescent multicolor fibers that are visible under ultraviolet light. Postage stamps are tagged with a phosphor that glows under UV rays to permit automatic detection of the stamp and facing of the letter.

UV fluorescent dyes are used in many applications (for example, biochemistry and forensics). Some brands of pepper spray will leave an invisible chemical (UV dye) that is not easily washed off on a pepper-sprayed attacker, which would help police identify the attacker later.

In some types of nondestructive testing UV stimulates fluorescent dyes to highlight defects in a broad range of materials. These dyes may be carried into surface-breaking defects by capillary action (liquid penetrant inspection) or they may be bound to ferrite particles caught in magnetic leakage fields in ferrous materials (magnetic particle inspection).

Analytic uses

[edit]Forensics

[edit]UV is an investigative tool at the crime scene helpful in locating and identifying bodily fluids such as semen, blood, and saliva.[105] For example, ejaculated fluids or saliva can be detected by high-power UV sources, irrespective of the structure or colour of the surface the fluid is deposited upon.[106] UV–vis microspectroscopy is also used to analyze trace evidence, such as textile fibers and paint chips, as well as questioned documents.

Other applications include the authentication of various collectibles and art, and detecting counterfeit currency. Even materials not specially marked with UV sensitive dyes may have distinctive fluorescence under UV exposure or may fluoresce differently under short-wave versus long-wave ultraviolet.

Enhancing contrast of ink

[edit]Using multi-spectral imaging it is possible to read illegible papyrus, such as the burned papyri of the Villa of the Papyri or of Oxyrhynchus, or the Archimedes palimpsest. The technique involves taking pictures of the illegible document using different filters in the infrared or ultraviolet range, finely tuned to capture certain wavelengths of light. Thus, the optimum spectral portion can be found for distinguishing ink from paper on the papyrus surface.

Simple NUV sources can be used to highlight faded iron-based ink on vellum.[107]

Sanitary compliance

[edit]

Ultraviolet helps detect organic material deposits that remain on surfaces where periodic cleaning and sanitizing may have failed. It is used in the hotel industry, manufacturing, and other industries where levels of cleanliness or contamination are inspected.[108][109][110][111]

Perennial news features for many television news organizations involve an investigative reporter using a similar device to reveal unsanitary conditions in hotels, public toilets, hand rails, and such.[112][113]

Chemistry

[edit]UV/Vis spectroscopy is widely used as a technique in chemistry to analyze chemical structure, the most notable one being conjugated systems. UV radiation is often used to excite a given sample where the fluorescent emission is measured with a spectrofluorometer. In biological research, UV radiation is used for quantification of nucleic acids or proteins. In environmental chemistry, UV radiation could also be used to detect Contaminants of emerging concern in water samples.[114]

In pollution control applications, ultraviolet analyzers are used to detect emissions of nitrogen oxides, sulfur compounds, mercury, and ammonia, for example in the flue gas of fossil-fired power plants.[115] Ultraviolet radiation can detect thin sheens of spilled oil on water, either by the high reflectivity of oil films at UV wavelengths, fluorescence of compounds in oil, or by absorbing of UV created by Raman scattering in water.[116] UV absorbance can also be used to quantify contaminants in wastewater. Most commonly used 254 nm UV absorbance is generally used as a surrogate parameters to quantify NOM.[114] Another form of light-based detection uses an excitation-emission matrix (EEM) to detect and identify contaminants based on their fluorescence properties.[114][117] EEM could be used to discriminate different groups of NOM based on the difference in light emission and excitation of fluorophores. NOMs with certain molecular structures are reported to have fluorescent properties in a wide range of excitation/emission wavelengths.[118][114]

Ultraviolet lamps are also used as part of the analysis of some minerals and gems.

Material science uses

[edit]Fire detection

[edit]In general, ultraviolet detectors use either a solid-state device, such as one based on silicon carbide or aluminium nitride, or a gas-filled tube as the sensing element. UV detectors that are sensitive to UV in any part of the spectrum respond to irradiation by sunlight and artificial light. A burning hydrogen flame, for instance, radiates strongly in the 185- to 260-nanometer range and only very weakly in the IR region, whereas a coal fire emits very weakly in the UV band yet very strongly at IR wavelengths; thus, a fire detector that operates using both UV and IR detectors is more reliable than one with a UV detector alone. Virtually all fires emit some radiation in the UVC band, whereas the Sun's radiation at this band is absorbed by the Earth's atmosphere. The result is that the UV detector is "solar blind", meaning it will not cause an alarm in response to radiation from the Sun, so it can easily be used both indoors and outdoors.

UV detectors are sensitive to most fires, including hydrocarbons, metals, sulfur, hydrogen, hydrazine, and ammonia. Arc welding, electrical arcs, lightning, X-rays used in nondestructive metal testing equipment (though this is highly unlikely), and radioactive materials can produce levels that will activate a UV detection system. The presence of UV-absorbing gases and vapors will attenuate the UV radiation from a fire, adversely affecting the ability of the detector to detect flames. Likewise, the presence of an oil mist in the air or an oil film on the detector window will have the same effect.

Photolithography

[edit]Ultraviolet radiation is used for very fine resolution photolithography, a procedure wherein a chemical called a photoresist is exposed to UV radiation that has passed through a mask. The exposure causes chemical reactions to occur in the photoresist. After removal of unwanted photoresist, a pattern determined by the mask remains on the sample. Steps may then be taken to "etch" away, deposit on or otherwise modify areas of the sample where no photoresist remains.

Photolithography is used in the manufacture of semiconductors, integrated circuit components,[119] and printed circuit boards. Photolithography processes used to fabricate electronic integrated circuits presently use 193 nm UV and are experimentally using 13.5 nm UV for extreme ultraviolet lithography.

Polymers

[edit]Electronic components that require clear transparency for light to exit or enter (photovoltaic panels and sensors) can be potted using acrylic resins that are cured using UV energy. The advantages are low VOC emissions and rapid curing.

Certain inks, coatings, and adhesives are formulated with photoinitiators and resins. When exposed to UV light, polymerization occurs, and so the adhesives harden or cure, usually within a few seconds. Applications include glass and plastic bonding, optical fiber coatings, the coating of flooring, UV coating and paper finishes in offset printing, dental fillings, and decorative fingernail "gels".

UV sources for UV curing applications include UV lamps, UV LEDs, and excimer flash lamps. Fast processes such as flexo or offset printing require high-intensity light focused via reflectors onto a moving substrate and medium so high-pressure Hg (mercury) or Fe (iron, doped)-based bulbs are used, energized with electric arcs or microwaves. Lower-power fluorescent lamps and LEDs can be used for static applications. Small high-pressure lamps can have light focused and transmitted to the work area via liquid-filled or fiber-optic light guides.

The impact of UV on polymers is used for modification of the (roughness and hydrophobicity) of polymer surfaces. For example, a poly(methyl methacrylate) surface can be smoothed by vacuum ultraviolet.[120]

UV radiation is useful in preparing low-surface-energy polymers for adhesives. Polymers exposed to UV will oxidize, thus raising the surface energy of the polymer. Once the surface energy of the polymer has been raised, the bond between the adhesive and the polymer is stronger.

Biology-related uses

[edit]Air purification

[edit]UV-C light is used in air conditioning systems as a method of improving indoor air quality by disinfecting the air and preventing microbial growth. UV-C light is effective at killing or inactivating harmful microorganisms, such as bacteria, viruses, mold, and mildew. When integrated into an air conditioning system, the ultraviolet light is typically placed in areas like the air handler or near the evaporator coil. In air conditioning systems, UV-C light works by irradiating the airflow within the system, killing or neutralizing harmful microorganisms before they are recirculated into the indoor environment. The effectiveness of it in air conditioning systems depends on factors such as the intensity of the light, the duration of exposure, airflow speed, and the cleanliness of system components.[121][122]

Using a catalytic chemical reaction from titanium dioxide and UVC exposure, oxidation of organic matter converts pathogens, pollens, and mold spores into harmless inert byproducts. However, the reaction of titanium dioxide and UVC is not a straight path. Several hundreds of reactions occur prior to the inert byproducts stage and can hinder the resulting reaction creating formaldehyde, aldehyde, and other VOC's en route to a final stage. Thus, the use of titanium dioxide and UVC requires very specific parameters for a successful outcome. The cleansing mechanism of UV is a photochemical process. Contaminants in the indoor environment are almost entirely organic carbon-based compounds, which break down when exposed to high-intensity UV at 240 to 280 nm. Short-wave ultraviolet radiation can destroy DNA in living microorganisms.[123] UVC's effectiveness is directly related to intensity and exposure time.

UV has also been shown to reduce gaseous contaminants such as carbon monoxide and VOCs.[124][125][126] UV lamps radiating at 184 and 254 nm can remove low concentrations of hydrocarbons and carbon monoxide if the air is recycled between the room and the lamp chamber. This arrangement prevents the introduction of ozone into the treated air. Likewise, air may be treated by passing by a single UV source operating at 184 nm and passed over iron pentaoxide to remove the ozone produced by the UV lamp.

Sterilization and disinfection

[edit]

Ultraviolet lamps are used to sterilize workspaces and tools used in biology laboratories and medical facilities. Commercially available low-pressure mercury-vapor lamps emit about 86% of their radiation at 254 nanometers (nm), with 265 nm being the peak germicidal effectiveness curve. UV at these germicidal wavelengths damage a microorganism's DNA/RNA so that it cannot reproduce, making it harmless, (even though the organism may not be killed).[127] Since microorganisms can be shielded from ultraviolet rays in small cracks and other shaded areas, these lamps are used only as a supplement to other sterilization techniques.

UVC LEDs are relatively new to the commercial market and are gaining in popularity.[failed verification][128] Due to their monochromatic nature (±5 nm)[failed verification] these LEDs can target a specific wavelength needed for disinfection. This is especially important knowing that pathogens vary in their sensitivity to specific UV wavelengths. LEDs are mercury free, instant on/off, and have unlimited cycling throughout the day.[129]

Disinfection using UV radiation is commonly used in wastewater treatment applications and is finding an increased usage in municipal drinking water treatment. Many bottlers of spring water use UV disinfection equipment to sterilize their water. Solar water disinfection[130] has been researched for cheaply treating contaminated water using natural sunlight. The UVA irradiation and increased water temperature kill organisms in the water.

Ultraviolet radiation is used in several food processes to kill unwanted microorganisms. UV can be used to pasteurize fruit juices by flowing the juice over a high-intensity ultraviolet source. The effectiveness of such a process depends on the UV absorbance of the juice.

Pulsed light (PL) is a technique of killing microorganisms on surfaces using pulses of an intense broad spectrum, rich in UVC between 200 and 280 nm. Pulsed light works with xenon flash lamps that can produce flashes several times per second. Disinfection robots use pulsed UV.[131]

The antimicrobial effectiveness of filtered far-UVC (222 nm) light on a range of pathogens, including bacteria and fungi showed inhibition of pathogen growth, and since it has lesser harmful effects, it provides essential insights for reliable disinfection in healthcare settings, such as hospitals and long-term care homes.[132] UVC has also been shown to be effective at degrading SARS-CoV-2 virus.[133]

Biological

[edit]Birds, reptiles, insects such as bees, and mammals such as mice, reindeer, dogs, and cats can see near-ultraviolet wavelengths.[134] Many fruits, flowers, and seeds stand out more strongly from the background in ultraviolet wavelengths as compared to human color vision. Scorpions glow or take on a yellow to green color under UV illumination, thus assisting in the control of these arachnids. Many birds have patterns in their plumage that are invisible at usual wavelengths but observable in ultraviolet, and the urine and other secretions of some animals, including dogs, cats, and human beings, are much easier to spot with ultraviolet. Urine trails of rodents can be detected by pest control technicians for proper treatment of infested dwellings.

Butterflies use ultraviolet as a communication system for sex recognition and mating behavior. For example, in the Colias eurytheme butterfly, males rely on visual cues to locate and identify females. Instead of using chemical stimuli to find mates, males are attracted to the ultraviolet-reflecting color of female hind wings.[135] In Pieris napi butterflies it was shown that females in northern Finland with less UV-radiation present in the environment possessed stronger UV signals to attract their males than those occurring further south. This suggested that it was evolutionarily more difficult to increase the UV-sensitivity of the eyes of the males than to increase the UV-signals emitted by the females.[136]

Many insects use the ultraviolet wavelength emissions from celestial objects as references for flight navigation. A local ultraviolet emitter will normally disrupt the navigation process and will eventually attract the flying insect.

The green fluorescent protein (GFP) is often used in genetics as a marker. Many substances, such as proteins, have significant light absorption bands in the ultraviolet that are of interest in biochemistry and related fields. UV-capable spectrophotometers are common in such laboratories.

Ultraviolet traps called bug zappers are used to eliminate various small flying insects. They are attracted to the UV and are killed using an electric shock, or trapped once they come into contact with the device. Different designs of ultraviolet radiation traps are also used by entomologists for collecting nocturnal insects during faunistic survey studies.

Therapy

[edit]Ultraviolet radiation is helpful in the treatment of skin conditions such as psoriasis and vitiligo. Exposure to UVA, while the skin is hyper-photosensitive, by taking psoralens is an effective treatment for psoriasis. Due to the potential of psoralens to cause damage to the liver, PUVA therapy may be used only a limited number of times over a patient's lifetime.

UVB phototherapy does not require additional medications or topical preparations for the therapeutic benefit; only the exposure is needed. However, phototherapy can be effective when used in conjunction with certain topical treatments such as anthralin, coal tar, and vitamin A and D derivatives, or systemic treatments such as methotrexate and Soriatane.[137]

Herpetology

[edit]Reptiles need UVB for biosynthesis of vitamin D, and other metabolic processes.[138] Specifically cholecalciferol (vitamin D3), which is needed for basic cellular / neural functioning as well as the utilization of calcium for bone and egg production.[citation needed] The UVA wavelength is also visible to many reptiles and might play a significant role in their ability survive in the wild as well as in visual communication between individuals.[citation needed] Therefore, in a typical reptile enclosure, a fluorescent UV a/b source (at the proper strength / spectrum for the species), must be available for many[which?] captive species to survive. Simple supplementation with cholecalciferol (Vitamin D3) will not be enough as there is a complete biosynthetic pathway[which?] that is "leapfrogged" (risks of possible overdoses), the intermediate molecules and metabolites[which?] also play important functions in the animals health.[citation needed] Natural sunlight in the right levels is always going to be superior to artificial sources, but this might not be possible for keepers in different parts of the world.[citation needed]

It is a known problem that high levels of output of the UVa part of the spectrum can both cause cellular and DNA damage to sensitive parts of their bodies – especially the eyes where blindness is the result of an improper UVa/b source use and placement photokeratitis.[citation needed] For many keepers there must also be a provision for an adequate heat source this has resulted in the marketing of heat and light "combination" products.[citation needed] Keepers should be careful of these "combination" light/ heat and UVa/b generators, they typically emit high levels of UVa with lower levels of UVb that are set and difficult to control so that animals can have their needs met.[citation needed] A better strategy is to use individual sources of these elements and so they can be placed and controlled by the keepers for the max benefit of the animals.[139]

Evolutionary significance

[edit]The evolution of early reproductive proteins and enzymes is attributed in modern models of evolutionary theory to ultraviolet radiation. UVB causes thymine base pairs next to each other in genetic sequences to bond together into thymine dimers, a disruption in the strand that reproductive enzymes cannot copy. This leads to frameshifting during genetic replication and protein synthesis, usually killing the cell. Before formation of the UV-blocking ozone layer, when early prokaryotes approached the surface of the ocean, they almost invariably died out. The few that survived had developed enzymes that monitored the genetic material and removed thymine dimers by nucleotide excision repair enzymes. Many enzymes and proteins involved in modern mitosis and meiosis are similar to repair enzymes, and are believed to be evolved modifications of the enzymes originally used to overcome DNA damages caused by UV.[140]

Elevated levels of ultraviolet radiation, in particular UV-B, have also been speculated as a cause of mass extinctions in the fossil record.[141]

Photobiology

[edit]Photobiology is the scientific study of the beneficial and harmful interactions of non-ionizing radiation in living organisms, conventionally demarcated around 10 eV, the first ionization energy of oxygen. UV ranges roughly from 3 to 30 eV in energy. Hence photobiology entertains some, but not all, of the UV spectrum.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Maqbool, Muhammad (2023). An Introduction to Non-Ionizing Radiation. Bentham Science Publishers. ISBN 978-981-5136-90-6.

- ^ a b Ida, Nathan (2008). Engineering Electromagnetics, 2nd Ed. Springer Science and Business Media. p. 1122. ISBN 978-0-387-20156-6.

- ^ "Reference Solar Spectral Irradiance: Air Mass 1.5". Archived from the original on 27 January 2011. Retrieved 12 November 2009.

- ^ Haigh, Joanna D. (2007). "The Sun and the Earth's Climate: Absorption of solar spectral radiation by the atmosphere". Living Reviews in Solar Physics. 4 (2): 2. Bibcode:2007LRSP....4....2H. doi:10.12942/lrsp-2007-2.

- ^ Wacker, Matthias; Holick, Michael F. (1 January 2013). "Sunlight and Vitamin D". Dermato-endocrinology. 5 (1): 51–108. doi:10.4161/derm.24494. ISSN 1938-1972. PMC 3897598. PMID 24494042.

- ^ a b David Hambling (29 May 2002). "Let the light shine in". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 November 2014. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ Cronin, Thomas W.; Bok, Michael J. (15 September 2016). "Photoreception and vision in the ultraviolet". Journal of Experimental Biology. 219 (18): 2790–2801. Bibcode:2016JExpB.219.2790C. doi:10.1242/jeb.128769. hdl:11603/13303. ISSN 1477-9145. PMID 27655820. S2CID 22365933.

- ^ M A Mainster (2006). "Violet and blue light blocking intraocular lenses: photoprotection versus photoreception". British Journal of Ophthalmology. 90 (6): 784–792. doi:10.1136/bjo.2005.086553. PMC 1860240. PMID 16714268.

- ^ Lynch, David K.; Livingston, William Charles (2001). Color and Light in Nature (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-521-77504-5. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

Limits of the eye's overall range of sensitivity extends from about 310 to 1050 nanometers

- ^ Dash, Madhab Chandra; Dash, Satya Prakash (2009). Fundamentals of Ecology 3E. Tata McGraw-Hill Education. p. 213. ISBN 978-1-259-08109-5. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 18 October 2013.

Normally the human eye responds to light rays from 390 to 760 nm. This can be extended to a range of 310 to 1,050 nm under artificial conditions.

- ^ Bennington-Castro, Joseph (22 November 2013). "Want ultraviolet vision? You're going to need smaller eyes". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on 7 May 2016.

- ^ Hunt, D. M.; Carvalho, L. S.; Cowing, J. A.; Davies, W. L. (2009). "Evolution and spectral tuning of visual pigments in birds and mammals". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 364 (1531): 2941–2955. doi:10.1098/rstb.2009.0044. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 2781856. PMID 19720655.

- ^ Gbur, Gregory (25 July 2024). "The discovery of ultraviolet light". Skulls in the Stars. Retrieved 17 September 2024. citing to "Von den Herren Ritter und Böckmann" [From Misters Ritter and Böckmann]. Annalen der Physik (in German). 7 (4): 527. 1801.

- ^ Frercks, Jan; Weber, Heiko; Wiesenfeldt, Gerhard (1 June 2009). "Reception and discovery: the nature of Johann Wilhelm Ritter's invisible rays". Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A. 40 (2): 143–156. Bibcode:2009SHPSA..40..143F. doi:10.1016/j.shpsa.2009.03.014. ISSN 0039-3681.

- ^ Draper, J.W. (1842). "On a new Imponderable Substance and on a Class of Chemical Rays analogous to the rays of Dark Heat". The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 80: 453–461.

- ^ Draper, John W. (1843). "Description of the tithonometer, an instrument for measuring the chemical force of the indigo-tithonic rays". The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 23 (154): 401–415. doi:10.1080/14786444308644763. ISSN 1941-5966.

- ^ Beeson, Steven; Mayer, James W (23 October 2007). "12.2.2 Discoveries beyond the visible". Patterns of light: chasing the spectrum from Aristotle to LEDs. New York: Springer. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-387-75107-8.

- ^ Hockberger, Philip E. (December 2002). "A history of ultraviolet photobiology for humans, animals and microorganisms". Photochem. Photobiol. 76 (6): 561–79. doi:10.1562/0031-8655(2002)0760561AHOUPF2.0.CO2. PMID 12511035. S2CID 222100404.

- ^ Bolton, James; Colton, Christine (2008). The Ultraviolet Disinfection Handbook. American Water Works Association. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-1 58321-584-5.

- ^ The ozone layer also protects living beings from this. Lyman, Theodore (1914). "Victor Schumann". The Astrophysical Journal. 38 (1): 1–4. Bibcode:1914ApJ....39....1L. doi:10.1086/142050.

- ^ Coblentz, W. W. (4 November 1932). "The Copenhagen Meeting of the Second International Congress on Light". Science. 76 (1975): 412–415. Bibcode:1932Sci....76..412C. doi:10.1126/science.76.1975.412. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17831918.

- ^ "ISO 21348 Definitions of Solar Irradiance Spectral Categories" (PDF). Space Weather (spacewx.com). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ^ Gullikson, E.M.; Korde, R.; Canfield, L.R.; Vest, R.E. (1996). "Stable silicon photodiodes for absolute intensity measurements in the VUV and soft X-ray regions" (PDF). Journal of Electron Spectroscopy and Related Phenomena. 80: 313–316. Bibcode:1996JESRP..80..313G. doi:10.1016/0368-2048(96)02983-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 January 2009. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ "Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy". JASCO Inc. Retrieved 21 January 2025.

- ^ Bally, John; Reipurth, Bo (2006). The Birth of Stars and Planets. Cambridge University Press. p. 177.

- ^ Bark, Yu B.; Barkhudarov, E.M.; Kozlov, Yu N.; Kossyi, I.A.; Silakov, V.P.; Taktakishvili, M.I.; Temchin, S.M. (2000). "Slipping surface discharge as a source of hard UV radiation". Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics. 33 (7): 859–863. Bibcode:2000JPhD...33..859B. doi:10.1088/0022-3727/33/7/317. S2CID 250819933.

- ^ "Solar radiation" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 November 2012.

- ^ "Introduction to Solar Radiation". newport.com. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013.

- ^ "Reference Solar Spectral Irradiance: Air Mass 1.5". Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 12 November 2009.

- ^ Understanding UVA and UVB, archived from the original on 1 May 2012, retrieved 30 April 2012

- ^ Vanhaelewyn, Lucas; Prinsen, Els; Van Der Straeten, Dominique; Vandenbussche, Filip (2016), "Hormone-controlled UV-B responses in plants", Journal of Experimental Botany, 67 (15): 4469–4482, Bibcode:2016JEBot..67.4469V, doi:10.1093/jxb/erw261, hdl:10067/1348620151162165141, PMID 27401912, archived from the original on 8 July 2016

- ^ Calbó, Josep; Pagès, David; González, Josep-Abel (2005). "Empirical studies of cloud effects on UV radiation: A review". Reviews of Geophysics. 43 (2). RG2002. Bibcode:2005RvGeo..43.2002C. doi:10.1029/2004RG000155. hdl:10256/8464. ISSN 1944-9208. S2CID 26285358.

- ^ Burnett, M. E.; Wang, S. Q. (2011). "Current sunscreen controversies: a critical review". Photodermatology, Photoimmunology & Photomedicine. 27 (2): 58–67. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0781.2011.00557.x. PMID 21392107. S2CID 29173997.

- ^ Dransfield, G.P. (1 September 2000). "Inorganic Sunscreens". Radiation Protection Dosimetry. 91 (1–3): 271–273. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.rpd.a033216. ISSN 0144-8420.

- ^ "Soda Lime Glass Transmission Curve". Archived from the original on 27 March 2012. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- ^ "B270-Superwite Glass Transmission Curve". Präzisions Glas & Optik. Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ "Selected Float Glass Transmission Curve". Präzisions Glas & Optik. Archived from the original on 19 October 2015. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ a b Moehrle, Matthias; Soballa, Martin; Korn, Manfred (2003). "UV exposure in cars". Photodermatology, Photoimmunology & Photomedicine. 19 (4): 175–181. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0781.2003.00031.x. ISSN 1600-0781. PMID 12925188. S2CID 37208948.

- ^ "Optical Materials". Newport Corporation. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- ^ "Wood's glass". chemeurope.com.

- ^ "Insect-O-Cutor" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 June 2013.

- ^ Rodrigues, Sueli; Fernandes, Fabiano Andre Narciso (18 May 2012). Advances in Fruit Processing Technologies. CRC Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-4398-5153-1. Archived from the original on 5 March 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2022.

- ^ Minkin, J. L., & Kellerman, A. S. (1966). A bacteriological method of estimating effectiveness of UV germicidal lamps. Public Health Reports, 81(10), 875.

- ^ Klose, Jules Z.; Bridges, J. Mervin; Ott, William R. (June 1987). Radiometric standards in the V‑UV (PDF). NBS Measurement Services (Report). NBS Special Publication. U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology. 250–3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 June 2016.

- ^ Bhattarai, Trailokya; Ebong, Abasifreke; Raja, M.Y.A. (May 2024). "A Review of Light-Emitting Diodes and Ultraviolet Light-Emitting Diodes and Their Applications". Photonics. 11 (6): 491. Bibcode:2024Photo..11..491B. doi:10.3390/photonics11060491.

- ^ "What is the difference between 365 nm and 395 nm UV LED lights?". waveformlighting.com. Archived from the original on 22 May 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ Patil, Renuka Subhash; Thomas, Jomin; Patil, Mahesh; John, Jacob (2023). "settings Order Article Reprints Open AccessReview To Shed Light on the UV Curable Coating Technology: Current State of the Art and Perspectives". Journal of Composites Science. 7 (12): 513. doi:10.3390/jcs7120513.

- ^ Boyce, J.M. (2016). "Modern technologies for improving cleaning and disinfection of environmental surfaces in hospitals". Antimicrobial Resistance and Infection Control. 5 (1) 10. doi:10.1186/s13756-016-0111-x. PMC 4827199. PMID 27069623.

- ^ a b "Ultraviolet germicidal irradiation" (PDF). University of Liverpool. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 August 2016.

- ^ "UV‑C LEDs Enhance Chromatography Applications". GEN Eng News. Archived from the original on 4 November 2016.

- ^ "UV laser diode: 375 nm center wavelength". Thorlabs. Product Catalog. United States / Germany. Archived from the original on 15 December 2014. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- ^ Marshall, Chris (1996). A simple, reliable ultraviolet laser: The Ce:LiSAF (Report). Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Archived from the original on 20 September 2008. Retrieved 11 January 2008.

- ^ Paschotta, R. (2006), "Ultraviolet Lasers - an encyclopedia article", RP Photonics Encyclopedia, RP Photonics AG, doi:10.61835/78l, retrieved 1 July 2025

- ^ Paschotta, Dr Rüdiger (8 November 2006). "Ultraviolet Lasers". RP Photonics Encyclopedia. doi:10.61835/78l.

- ^ EVLaser. "Why are UV lasers used: applications, characteristics and types". EVlaser Industrial. Retrieved 19 October 2025.

- ^ a b c Strauss, C.E.M.; Funk, D.J. (1991). "Broadly tunable difference-frequency generation of VUV using two-photon resonances in H2 and Kr". Optics Letters. 16 (15): 1192–4. Bibcode:1991OptL...16.1192S. doi:10.1364/ol.16.001192. PMID 19776917. Archived from the original on 29 May 2024. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ^

Xiong, Bo; Chang, Yih-Chung; Ng, Cheuk-Yiu (2017). "Quantum-state-selected integral cross sections for the charge transfer collision of O+

2 (a4 Π u 5/2,3/2,1/2,−1/2: v+=1–2; J+) [ O+

2 (X2 Π g 3/2,1/2: v+=22–23; J+) ] + Ar at center-of-mass collision energies of 0.05–10.00 eV". Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 19 (43): 29057–29067. Bibcode:2017PCCP...1929057X. doi:10.1039/C7CP04886F. PMID 28920600. Archived from the original on 15 November 2017. - ^ "E‑UV nudges toward 10 nm". EE Times. Archived from the original on 15 October 2014. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- ^ Sivamani, R.K.; Crane, L.A.; Dellavalle, R.P. (April 2009). "The benefits and risks of ultraviolet tanning and its alternatives: The role of prudent sun exposure". Dermatologic Clinics. 27 (2): 149–154. doi:10.1016/j.det.2008.11.008. PMC 2692214. PMID 19254658.

- ^ Wacker, Matthias; Holick, Michael F. (1 January 2013). "Sunlight and Vitamin D". Dermato-endocrinology. 5 (1): 51–108. doi:10.4161/derm.24494. ISSN 1938-1972. PMC 3897598. PMID 24494042.

- ^ a b The known health effects of UV: Ultraviolet radiation and the INTERSUN Programme (Report). World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 16 October 2016.

- ^ Lamberg-Allardt, Christel (1 September 2006). "Vitamin D in foods and as supplements". Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. 92 (1): 33–38. doi:10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2006.02.017. ISSN 0079-6107. PMID 16618499.

- ^ Juzeniene, Asta; Moan, Johan (27 October 2014). "Beneficial effects of UV radiation other than via vitamin D production". Dermato-Endocrinology. 4 (2): 109–117. doi:10.4161/derm.20013. PMC 3427189. PMID 22928066.

- ^ "Health effects of ultraviolet radiation" Archived 8 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Government of Canada.

- ^ Herzinger, T.; Funk, J.O.; Hillmer, K.; Eick, D.; Wolf, D.A.; Kind, P. (1995). "Ultraviolet B irradiation-induced G2 cell cycle arrest in human keratinocytes by inhibitory phosphorylation of the cdc2 cell cycle kinase". Oncogene. 11 (10): 2151–2156. PMID 7478536.

- ^ Bhatia, Bhavnit K.; Bahr, Brooks A.; Murase, Jenny E. (2015). "Excimer laser therapy and narrowband ultraviolet B therapy for exfoliative cheilitis". International Journal of Women's Dermatology. 1 (2): 95–98. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2015.01.006. PMC 5418752. PMID 28491966.

- ^ Meyer-Rochow, Victor Benno (2000). "Risks, especially for the eye, emanating from the rise of solar UV-radiation in the Arctic and Antarctic regions". International Journal of Circumpolar Health. 59 (1): 38–51. PMID 10850006.

- ^ "Health effects of UV radiation". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 17 March 2015.

- ^ Ultraviolet Radiation Guide (PDF). Environmental Health Center (Report). Norfolk, Virginia: U.S.Navy. April 1992. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ "What is ultraviolet (UV) radiation?". cancer.org. Archived from the original on 3 April 2017. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ Torma, H.; Berne, B.; Vahlquist, A. (1988). "UV irradiation and topical vitamin A modulate retinol esterification in hairless mouse epidermis". Acta Derm. Venereol. 68 (4): 291–299. PMID 2459873.

- ^ a b Bernstein C, Bernstein H, Payne CM, Garewal H (June 2002). "DNA repair / pro-apoptotic dual-role proteins in five major DNA repair pathways: Fail-safe protection against carcinogenesis". Mutat. Res. 511 (2): 145–78. Bibcode:2002MRRMR.511..145B. doi:10.1016/S1383-5742(02)00009-1. PMID 12052432.

- ^ Davies, H.; Bignell, G.R.; Cox, C. (June 2002). "Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer" (PDF). Nature. 417 (6892): 949–954. Bibcode:2002Natur.417..949D. doi:10.1038/nature00766. PMID 12068308. S2CID 3071547. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- ^ Weller, Richard (10 June 2015). "Shunning the sun may be killing you in more ways than you think". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 9 June 2017.

- ^ Hogan, C. Michael (25 May 2012) [November 12, 2010]. "Sunlight". In Saundry, P.; Cleveland, C. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Earth. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013.

- ^ D'Orazio, John; Jarrett, Stuart; Amaro-Ortiz, Alexandra; Scott, Timothy (7 June 2013). "UV Radiation and the Skin". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 14 (6): 12222–12248. doi:10.3390/ijms140612222. ISSN 1422-0067. PMC 3709783. PMID 23749111.

- ^ Svobodová AR, Galandáková A, Sianská J, et al. (January 2012). "DNA damage after acute exposure of mice skin to physiological doses of UVB and UVA light". Arch. Dermatol. Res. 304 (5): 407–412. doi:10.1007/s00403-012-1212-x. PMID 22271212. S2CID 20554266.

- ^ Halliday GM, Byrne SN, Damian DL (December 2011). "Ultraviolet A radiation: Its role in immunosuppression and carcinogenesis". Semin. Cutan. Med. Surg. 30 (4): 214–21. doi:10.1016/j.sder.2011.08.002 (inactive 1 July 2025). PMID 22123419.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ Wurtmann, Elisabeth J.; Wolin, Sandra L. (1 February 2009). "RNA under attack: Cellular handling of RNA damage". Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 44 (1): 34–49. doi:10.1080/10409230802594043. ISSN 1040-9238. PMC 2656420. PMID 19089684.

- ^ Vind, Anna Constance; Wu, Zhenzhen; Firdaus, Muhammad Jasrie; Snieckute, Goda; Toh, Gee Ann; Jessen, Malin; Martínez, José Francisco; Haahr, Peter; Andersen, Thomas Levin; Blasius, Melanie; Koh, Li Fang; Maartensson, Nina Loeth; Common, John E.A.; Gyrd-Hansen, Mads; Zhong, Franklin L. (2024). "The ribotoxic stress response drives acute inflammation, cell death, and epidermal thickening in UV-irradiated skin in vivo". Molecular Cell. 84 (24): 4774–4789.e9. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2024.10.044. PMC 11671030. PMID 39591967.

- ^ a b Xu, C.; Green, Adele; Parisi, Alfio; Parsons, Peter G (2001). "Photosensitization of the sunscreen octyl p‑dimethylaminobenzoate b UV‑A in human melanocytes but not in keratinocytes". Photochemistry and Photobiology. 73 (6): 600–604. doi:10.1562/0031-8655(2001)073<0600:POTSOP>2.0.CO;2. PMID 11421064. S2CID 38706861.

- ^ a b Knowland, John; McKenzie, Edward A.; McHugh, Peter J.; Cridland, Nigel A. (1993). "Sunlight-induced mutagenicity of a common sunscreen ingredient". FEBS Letters. 324 (3): 309–313. Bibcode:1993FEBSL.324..309K. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(93)80141-G. PMID 8405372. S2CID 23853321.

- ^ Chatelaine, E.; Gabard, B.; Surber, C. (2003). "Skin penetration and sun protection factor of five UV filters: Effect of the vehicle". Skin Pharmacol. Appl. Skin Physiol. 16 (1): 28–35. doi:10.1159/000068291. PMID 12566826. S2CID 13458955. Archived from the original on 27 December 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- ^ Stephens TJ, Herndon JH, Colón LE, Gottschalk RW (February 2011). "The impact of natural sunlight exposure on the UV‑B – sun protection factor (UVB-SPF) and UVA protection factor (UVA-PF) of a UV‑A / UV‑B SPF 50 sunscreen". J. Drugs Dermatol. 10 (2): 150–155. PMID 21283919.

- ^ Couteau C, Couteau O, Alami-El Boury S, Coiffard LJ (August 2011). "Sunscreen products: what do they protect us from?". Int. J. Pharm. 415 (1–2): 181–184. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.05.071. PMID 21669263.

- ^ Garland C, Garland F, Gorham E (1992). "Could sunscreens increase melanoma risk?". Am. J. Public Health. 82 (4): 614–615. doi:10.2105/AJPH.82.4.614. PMC 1694089. PMID 1546792.

- ^ Westerdahl J, Ingvar C, Masback A, Olsson H (2000). "Sunscreen use and malignant melanoma". International Journal of Cancer. 87 (1): 145–150. doi:10.1002/1097-0215(20000701)87:1<145::AID-IJC22>3.0.CO;2-3. PMID 10861466.

- ^ Autier P, Dore JF, Schifflers E, et al. (1995). "Melanoma and use of sunscreens: An EORTC case control study in Germany, Belgium and France". Int. J. Cancer. 61 (6): 749–755. doi:10.1002/ijc.2910610602. PMID 7790106. S2CID 34941555.

- ^ Weinstock, M. A. (1999). "Do sunscreens increase or decrease melanoma risk: An epidemiologic evaluation". Journal of Investigative Dermatology Symposium Proceedings. 4 (1): 97–100. PMID 10537017. Archived from the original on 5 December 2022. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ Vainio, H.; Bianchini, F. (2000). "Commentary: Cancer-preventive effects of sunscreens are uncertain". Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health. 26 (6): 529–531. doi:10.5271/sjweh.578.

- ^ a b c Hanson, Kerry M.; Gratton, Enrico; Bardeen, Christopher J. (2006). "Sunscreen enhancement of UV-induced reactive oxygen species in the skin" (PDF). Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 41 (8): 1205–1212. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.06.011. PMID 17015167. S2CID 13999532. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 March 2020. Retrieved 6 September 2018.