Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Glioblastoma.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Glioblastoma

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

Not found

Glioblastoma

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

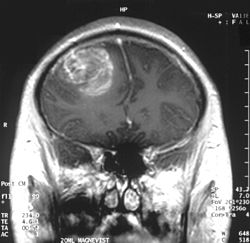

Glioblastoma, also known as glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), is a highly aggressive grade IV astrocytic tumor that originates from glial cells, particularly astrocytes, within the brain or, rarely, the spinal cord.[1][2] It represents the most common primary malignant brain tumor in adults, accounting for more than half of all gliomas and approximately 15% of all primary brain tumors.[3][4] Characterized by rapid proliferation, extensive infiltration into surrounding healthy tissue, and resistance to therapy, it typically affects individuals aged 45 to 70, with a higher incidence in males.[5][4]

Common symptoms of glioblastoma arise from increased intracranial pressure and disruption of brain function, including persistent headaches (often worsening in the morning), nausea and vomiting, seizures, cognitive impairments such as confusion or memory loss, personality changes, and neurological deficits like weakness, vision or speech difficulties, and balance problems.[2][1] The exact cause remains unknown in most cases, involving genetic mutations that lead to uncontrolled cell growth, though risk factors include prior exposure to ionizing radiation and rare inherited syndromes such as Li-Fraumeni or Lynch syndrome.[2] In the United States, an estimated 24,820 new cases of malignant brain and spinal cord tumors are diagnosed annually, with glioblastoma comprising a significant portion, particularly among adults.[6]

Diagnosis typically begins with a neurological examination to assess deficits in strength, coordination, reflexes, and sensory function, followed by imaging such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast or computed tomography (CT) scans to visualize the tumor's location, size, and characteristics.[7][1] A definitive diagnosis requires a biopsy or surgical resection to examine tissue under a microscope, confirming the presence of malignant cells and determining the tumor's grade based on World Health Organization criteria.[7][1] Treatment usually involves maximal safe surgical resection to remove as much tumor as possible, followed by radiation therapy and chemotherapy, often with temozolomide, to target residual cells; additional options may include tumor-treating fields (TTFields) or targeted therapies for specific molecular subtypes.[7][1]

Despite multimodal treatment, the prognosis for glioblastoma remains poor, with a median overall survival of approximately 14-16 months with standard treatment (maximal safe surgical resection, radiotherapy, and temozolomide chemotherapy). The addition of tumor-treating fields (TTFields) can extend median survival to around 20-21 months in some patients. The five-year survival rate is typically 5-10%. No major changes to these figures have been reported for 2025 or 2026. Survival is influenced by factors such as age, tumor location, extent of resection, and molecular markers like MGMT methylation status.[8][9] The tumor's heterogeneity, ability to evade the blood-brain barrier, and high recurrence rate—often within the original radiation field—underscore the need for ongoing research into immunotherapy, precision medicine, and novel drug delivery methods to improve outcomes.[1][5]