Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Musical instrument

View on Wikipedia

A musical instrument is a device created or adapted to make musical sounds. In principle, any object that produces sound can be considered a musical instrument—it is through purpose that the object becomes a musical instrument. A person who plays a musical instrument is known as an instrumentalist.

The history of musical instruments dates to the beginnings of human culture. Early musical instruments may have been used for rituals, such as a horn to signal success on the hunt, or a drum in a religious ceremony. Cultures eventually developed composition and performance of melodies for entertainment. Musical instruments evolved in step with changing applications and technologies.

The exact date and specific origin of the first device considered a musical instrument, is widely disputed. The oldest object identified by scholars as a musical instrument, is a simple flute, dated back 50,000–60,000 years. Many scholars date early flutes to about 40,000 years ago. Many historians believe that determining the specific date of musical instrument invention is impossible, as the majority of early musical instruments were constructed of animal skins, bone, wood, and other non-durable, bio-degradable materials. Additionally, some have proposed that lithophones, or stones used to make musical sounds—like those found at Sankarjang in India—are examples of prehistoric musical instruments.

Musical instruments developed independently in many populated regions of the world. However, contact among civilizations caused rapid spread and adaptation of most instruments in places far from their origin. By the post-classical era, instruments from Mesopotamia were in maritime Southeast Asia, and Europeans played instruments originating from North Africa. Development in the Americas occurred at a slower pace, but cultures of North, Central, and South America shared musical instruments.

By 1400, musical instrument development slowed in many areas and was dominated by the Occident. During the Classical and Romantic periods of music, lasting from roughly 1750 to 1900, many new musical instruments were developed. While the evolution of traditional musical instruments slowed beginning in the 20th century, the proliferation of electricity led to the invention of new electric and electronic instruments, such as electric guitars, synthesizers, and the theremin.

Musical instrument classification is a discipline in its own right, and many systems of classification have been used over the years. Instruments can be classified by their effective range, material composition, size, role, etc. However, the most common academic method, Hornbostel–Sachs, uses the means by which they produce sound. The academic study of musical instruments is called organology.

Definition and basic operation

[edit]

A musical instrument is used to make musical sounds. Once humans moved from making sounds with their bodies — for example, by clapping—to using objects to create music from sounds, musical instruments were born.[2]

Primitive instruments were probably designed to emulate natural sounds, and their purpose was ritual rather than entertainment.[3]

The concept of melody and the artistic pursuit of musical composition were probably unknown to early players of musical instruments. A person sounding a bone flute to signal the start of a hunt does so without thought of the modern notion of "making music".[3]

Musical instruments are constructed in a broad array of styles and shapes, using many different materials. Early musical instruments were made from "found objects" such as shells and plant parts.[3] As instruments evolved, so did the selection and quality of materials. Virtually every material in nature has been used by at least one culture to make musical instruments.[3]

One plays a musical instrument by interacting with it in some way — for example, by plucking the strings on a string instrument, striking the surface of a drum, or blowing into an animal horn.[3]

Archaeology

[edit]Researchers have discovered archaeological evidence of musical instruments in many parts of the world. One disputed artifact (the Divje Babe flute) has been dated to 67,000 years old, but consensus solidifies around artifacts dated back to around 37,000 years old and later. Artifacts made from durable materials or constructed using durable methods, have been found to survive. As such, the specimens found cannot be irrefutably placed as the earliest musical instruments.[4] Recent studies indicate early hominins produced their percussive instruments from such perishable materials as wood and animal hides which likely the passing of time destroyed the artifacts beyond recovery.[5][page needed]

Flutes

[edit]The Divje Babe Flute is a perforated bone discovered in 1995, in the northwest region of Slovenia by archaeologist Ivan Turk. Its origin is disputed, with many arguing that it is most likely the product of carnivores chewing the bone,[6] but Turk and others argue that it is a Neanderthal-made flute. With its age estimated between 43,400 and 67,000 years old, it would be the oldest known musical instrument and the only Neanderthal musical instrument.[7]

Mammoth bone and swan bone flutes have been found dating back to 30,000 to 37,000 years old in the Swabian Alps of Germany. The flutes were made in the Upper Paleolithic age, and are more commonly accepted as being the oldest known musical instruments.[8]

Sumerian city of Ur

[edit]Archaeological evidence of musical instruments was discovered in excavations at the Royal Cemetery in the Sumerian city of Ur.

These instruments, one of the first ensembles of instruments yet discovered, include nine lyres (the Lyres of Ur), two harps, a silver double flute, a sistrum, and cymbals. A set of reed-sounded silver pipes discovered in Ur was the likely predecessor of modern bagpipes.[9] The cylindrical pipes feature three side holes that allowed players to produce a whole-tone scale.[10]

These excavations, carried out by Leonard Woolley in the 1920s, uncovered non-degradable fragments of instruments and the voids left by the degraded segments that, together, have been used to reconstruct them.[11]

The graves these instruments were buried in have been carbon dated to between 2600 and 2500 BC, providing evidence that these instruments were used in Sumeria by this time.[12]

Jiahu site

[edit]Archaeologists in the Jiahu site of central Henan province of China have found flutes made of bones that date back 7,000 to 9,000 years,[13] representing some of the "earliest complete, playable, tightly-dated, multinote musical instruments" ever found.[13][14] The examination of these instruments reveals they were made with precision to generate specific notes thus showing Neolithic China's advanced knowledge of music scales and sound engineering.[15]

History

[edit]Scholars agree that there are no completely reliable methods of determining the exact chronology of musical instruments across cultures. Comparing and organizing instruments based on their complexity is misleading, since advancements in musical instruments have sometimes reduced complexity. For example, the construction of early slit drums involved felling and hollowing out large trees; later slit drums were made by opening bamboo stalks, a much simpler task.[16]

German musicologist Curt Sachs, one of the most prominent musicologists[17] and musical ethnologists[18] in modern times, argues that it is misleading to arrange the development of musical instruments by workmanship, since cultures advance at different rates and have access to different raw materials.

For example, contemporary anthropologists comparing musical instruments from two cultures that existed at the same time but differed in organization, culture, and handicraft cannot determine which instruments are more "primitive".[19]

Ordering instruments by geography is also not reliable, as it cannot always be determined when and how cultures contacted one another and shared knowledge. Sachs proposed that a geographical chronology until approximately 1400 is preferable, however, due to its limited subjectivity.[20] Beyond 1400, one can follow the overall development of musical instruments over time.[20]

The science of marking the order of musical instrument development relies on archaeological artifacts, artistic depictions, and literary references. Since data in one research path can be inconclusive, all three paths provide a better historical picture.[4]

Prehistoric

[edit]

Until the 19th century AD, European-written music histories began with mythological accounts mingled with scripture of how musical instruments were invented. Such accounts included Jubal, descendant of Cain and "father of all such as handle the harp and the organ" (Genesis 4:21) Pan, inventor of the pan pipes, and Mercury, who is said to have made a dried tortoise shell into the first lyre. Modern histories have replaced such mythology with anthropological speculation, occasionally informed by archeological evidence. Scholars agree that there was no definitive "invention" of the musical instrument since the term "musical instrument" is subjective and hard to define.[21]

Among the first devices external to the human body that are considered instruments are rattles, stampers, and various drums.[22] These instruments evolved due to the human motor impulse to add sound to emotional movements such as dancing.[23] Eventually, some cultures assigned ritual functions to their musical instruments, using them for hunting and various ceremonies.[24] Those cultures developed more complex percussion instruments and other instruments such as ribbon reeds, flutes, and trumpets. Some of these labels carry far different connotations from those used in modern day; early flutes and trumpets are so-labeled for their basic operation and function rather than resemblance to modern instruments.[25] Among early cultures for whom drums developed ritual, even sacred importance are the Chukchi people of the Russian Far East, the indigenous people of Melanesia, and many cultures of Africa. In fact, drums were pervasive throughout every African culture.[26] One East African tribe, the Wahinda, believed it was so holy that seeing a drum would be fatal to any person other than the sultan.[27]

Humans eventually developed the concept of using musical instruments to produce melody, which was previously common only in singing. Similar to the process of reduplication in language, instrument players first developed repetition and then arrangement. An early form of melody was produced by pounding two stamping tubes of slightly different sizes—one tube would produce a "clear" sound and the other would answer with a "darker" sound. Such instrument pairs also included bullroarers, slit drums, shell trumpets, and skin drums. Cultures who used these instrument pairs associated them with gender; the "father" was the bigger or more energetic instrument, while the "mother" was the smaller or duller instrument. Musical instruments existed in this form for thousands of years before patterns of three or more tones would evolve in the form of the earliest xylophone.[28] Xylophones originated in the mainland and archipelago of Southeast Asia, eventually spreading to Africa, the Americas, and Europe.[29] Along with xylophones, which ranged from simple sets of three "leg bars" to carefully tuned sets of parallel bars, various cultures developed instruments such as the ground harp, ground zither, musical bow, and jaw harp.[30] Recent research into usage wear and acoustics of stone artefacts has revealed a possible new class of prehistoric musical instrument, known as lithophones.[31][32]

Antiquity

[edit]Images of musical instruments begin to appear in Mesopotamian artifacts in 2800 BC or earlier. Beginning around 2000 BC, Sumerian and Babylonian cultures began delineating two distinct classes of musical instruments due to division of labor and the evolving class system. Popular instruments, simple and playable by anyone, evolved differently from professional instruments whose development focused on effectiveness and skill.[33] Despite this development, very few musical instruments have been recovered in Mesopotamia. Scholars must rely on artifacts and cuneiform texts written in Sumerian or Akkadian to reconstruct the early history of musical instruments in Mesopotamia. Even the process of assigning names to these instruments is challenging since there is no clear distinction among various instruments and the words used to describe them.[34]

Although Sumerian and Babylonian artists mainly depicted ceremonial instruments, historians have distinguished six idiophones used in early Mesopotamia: concussion clubs, clappers, sistra, bells, cymbals, and rattles.[35] Sistra are depicted prominently in a great relief of Amenhotep III,[36] and are of particular interest because similar designs have been found in far-reaching places such as Tbilisi, Georgia and among the Native American Yaqui tribe.[37] The people of Mesopotamia preferred stringed instruments, as evidenced by their proliferation in Mesopotamian figurines, plaques, and seals. Innumerable varieties of harps are depicted, as well as lyres and lutes, the forerunner of modern stringed instruments such as the violin.[38]

Musical instruments used by the Egyptian culture before 2700 BC bore striking similarity to those of Mesopotamia, leading historians to conclude that the civilizations must have been in contact with one another. Sachs notes that Egypt did not possess any instruments that the Sumerian culture did not also possess.[39] However, by 2700 BC the cultural contacts seem to have dissipated; the lyre, a prominent ceremonial instrument in Sumer, did not appear in Egypt for another 800 years.[39] Clappers and concussion sticks appear on Egyptian vases as early as 3000 BC. The civilization also made use of sistra, vertical flutes, double clarinets, arched and angular harps, and various drums.[40]

Little history is available in the period between 2700 BC and 1500 BC, as Egypt (and indeed, Babylon) entered a long violent period of war and destruction. This period saw the Kassites destroy the Babylonian empire in Mesopotamia and the Hyksos destroy the Middle Kingdom of Egypt. When the Pharaohs of Egypt conquered Southwest Asia in around 1500 BC, the cultural ties to Mesopotamia were renewed and Egypt's musical instruments also reflected heavy influence from Asiatic cultures.[39] Under their new cultural influences, the people of the New Kingdom began using oboes, trumpets, lyres, lutes, castanets, and cymbals.[41]

Unlike Mesopotamia and Egypt, professional musicians did not exist in Israel between 2000 and 1000 BC. While the history of musical instruments in Mesopotamia and Egypt relies on artistic representations, the culture in Israel produced few such representations. Scholars must therefore rely on information gleaned from the Bible and the Talmud.[42] The Hebrew texts mention two prominent instruments associated with Jubal: the ugab (pipes) and kinnor (lyre).[43] Other instruments of the period included the tof (frame drum), pa'amon (small bells or jingles), shofar, and the trumpet-like hasosra.[44]

The introduction of a monarchy in Israel during the 11th century BC produced the first professional musicians and with them a drastic increase in the number and variety of musical instruments.[45] However, identifying and classifying the instruments remains a challenge due to the lack of artistic interpretations. For example, stringed instruments of uncertain design called nevals and asors existed, but neither archaeology nor etymology can clearly define them.[46] In her book A Survey of Musical Instruments, American musicologist Sibyl Marcuse proposes that the nevel must be similar to vertical harp due to its relation to nabla, the Phoenician term for "harp".[47]

In Greece, Rome, and Etruria, the use and development of musical instruments stood in stark contrast to those cultures' achievements in architecture and sculpture. The instruments of the time were simple and virtually all of them were imported from other cultures.[48] Lyres were the principal instrument, as musicians used them to honor the gods.[49] Greeks played a variety of wind instruments they classified as aulos (reeds) or syrinx (flutes); Greek writing from that time reflects a serious study of reed production and playing technique.[10] Romans played reed instruments named tibia, featuring side-holes that could be opened or closed, allowing for greater flexibility in playing modes.[50] Other instruments in common use in the region included vertical harps derived from those of the Orient, lutes of Egyptian design, various pipes and organs, and clappers, which were played primarily by women.[51]

Evidence of musical instruments in use by early civilizations of India is almost completely lacking, making it impossible to reliably attribute instruments to the Munda and Dravidian language-speaking cultures that first settled the area. Rather, the history of musical instruments in the area begins with the Indus Valley civilization that emerged around 3000 BC. Various rattles and whistles found among excavated artifacts are the only physical evidence of musical instruments.[52] A clay statuette indicates the use of drums, and examination of the Indus script has also revealed representations of vertical arched harps identical in design to those depicted in Sumerian artifacts. This discovery is among many indications that the Indus Valley and Sumerian cultures maintained cultural contact. Subsequent developments in musical instruments in India occurred with the Rigveda, or hymns. These songs used various drums, shell trumpets, harps, and flutes.[53] Other prominent instruments in use during the early centuries AD were the snake charmer's double clarinet, bagpipes, barrel drums, cross flutes, and short lutes. In all, India had no unique musical instruments until the post-classical era.[54]

Musical instruments such as zithers appeared in Chinese writings around 12th century BC and earlier.[55] Early Chinese philosophers such as Confucius (551–479 BC), Mencius (372–289 BC), and Laozi shaped the development of musical instruments in China, adopting an attitude toward music similar to that of the Greeks. The Chinese believed that music was an essential part of character and community, and developed a unique system of classifying their musical instruments according to their material makeup.[56] In Vietnam, an archaeological discovery of a 2,000-year old stringed instrument gives important insights on early chordophones in Southeast Asia.[57]

Idiophones were extremely important in Chinese music, hence the majority of early instruments were idiophones. Poetry of the Shang dynasty mentions bells, chimes, drums, and globular flutes carved from bone, the latter of which has been excavated and preserved by archaeologists.[58] The Zhou dynasty saw percussion instruments such as clappers, troughs, wooden fish, and yǔ (wooden tiger). Wind instruments such as flute, pan-pipes, pitch-pipes, and mouth organs also appeared in this time period.[59] The xiao (an end-blown flute) and various other instruments that spread through many cultures, came into use in China during and after the Han dynasty.[60]

Although civilizations in Central America attained a relatively high level of sophistication by the eleventh century AD, they lagged behind other civilizations in the development of musical instruments. For example, they had no stringed instruments; all of their instruments were idiophones, drums, and wind instruments such as flutes and trumpets. Of these, only the flute was capable of producing a melody.[61] In contrast, pre-Columbian South American civilizations in areas such as modern-day Peru, Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia, and Chile were less advanced culturally but more advanced musically. South American cultures of the time used pan-pipes as well as varieties of flutes, idiophones, drums, and shell or wood trumpets.[62]

An instrument that can be attested to the Iron Age Celts is the carnyx, which is dated to c.300 BC. The end of the bell, which was crafted from bronze, was into the shape of a screaming animal head which was held high above their heads. When blown into, the carnyx would emit a deep, harsh sound; the head also had a tongue which clicked when vibrated. It is believed the intention of the instrument was to use it on the battleground to intimidate their opponents.[63][64]

Post-classical era/Middle Ages

[edit]During the period of time loosely referred to as the post-classical era and Europe in particular as the Middle Ages, China developed a tradition of integrating musical influence from other regions. The first record of this type of influence is in 384 AD, when China established an orchestra in its imperial court after a conquest in Turkestan. Influences from Middle East, Persia, India, Mongolia, and other countries followed. In fact, Chinese tradition attributes many musical instruments from this period to those regions and countries.[65] Cymbals gained popularity, along with more advanced trumpets, clarinets, pianos, oboes, flutes, drums, and lutes.[66] Some of the first bowed zithers appeared in China in the 9th or 10th century, influenced by Mongolian culture.[67]

India experienced similar development to China in the post-classical era; however, stringed instruments developed differently as they accommodated different styles of music. While stringed instruments of China were designed to produce precise tones capable of matching the tones of chimes, stringed instruments of India were considerably more flexible. This flexibility suited the slides and tremolos of Hindu music. Rhythm was of paramount importance in Indian music of the time, as evidenced by the frequent depiction of drums in reliefs dating to the post-classical era. The emphasis on rhythm is an aspect native to Indian music.[68] Historians divide the development of musical instruments in medieval India between pre-Islamic and Islamic periods due to the different influence each period provided.[69]

In pre-Islamic times, idiophones such as handbells, cymbals, and peculiar instruments resembling gongs came into wide use in Hindu music. The gong-like instrument was a bronze disk that was struck with a hammer instead of a mallet. Tubular drums, stick zithers (veena), short fiddles, double and triple flutes, coiled trumpets, and curved India horns emerged in this time period.[70] Islamic influences brought new types of drum, perfectly circular or octagonal as opposed to the irregular pre-Islamic drums.[71] Persian influence brought oboes and sitars, although Persian sitars had three strings and Indian version had from four to seven.[72] The Islamic culture also introduced double-clarinet instruments as the Alboka (from Arab, al-buq or "horn") nowadays only alive in Basque Country. It must be played using the technique of the circular breathing.

Southeast Asian musical innovations include those during a period of Indian influence that ended around 920 AD.[73] Balinese and Javanese music made use of xylophones and metallophones, bronze versions of the former.[74] The most prominent and important musical instrument of Southeast Asia was the gong. While the gong likely originated in the geographical area between Tibet and Burma, it was part of every category of human activity in maritime Southeast Asia including Java.[75]

The areas of Mesopotamia and the Arabian Peninsula experiences rapid growth and sharing of musical instruments once they were united by Islamic culture in the seventh century.[76] Frame drums and cylindrical drums of various depths were immensely important in all genres of music.[77] Conical oboes were involved in the music that accompanied wedding and circumcision ceremonies. Persian miniatures provide information on the development of kettle drums in Mesopotamia that spread as far as Java.[78] Various lutes, zithers, dulcimers, and harps spread as far as Madagascar to the south and modern-day Sulawesi to the east.[79]

Despite the influences of Greece and Rome, most musical instruments in Europe during the Middles Ages came from Asia. The lyre is the only musical instrument that may have been invented in Europe until this period.[80] Stringed instruments were prominent in Middle Age Europe. The central and northern regions used mainly lutes, stringed instruments with necks, while the southern region used lyres, which featured a two-armed body and a crossbar.[80] Various harps served Central and Northern Europe as far north as Ireland, where the harp eventually became a national symbol.[81] Lyres propagated through the same areas, as far east as Estonia.[82]

European music between 800 and 1100 became more sophisticated, more frequently requiring instruments capable of polyphony. The 9th-century Persian geographer Ibn Khordadbeh mentioned in his lexicographical discussion of music instruments that, in the Byzantine Empire, typical instruments included the urghun (organ), shilyani (probably a type of harp or lyre), salandj (probably a bagpipe) and the lyra.[83] The Byzantine lyra, a bowed string instrument, is an ancestor of most European bowed instruments, including the violin.[84]

The monochord served as a precise measure of the notes of a musical scale, allowing more accurate musical arrangements.[85] Mechanical hurdy-gurdies allowed single musicians to play more complicated arrangements than a fiddle would; both were prominent folk instruments in the Middle Ages.[86][87] Southern Europeans played short and long lutes whose pegs extended to the sides, unlike the rear-facing pegs of Central and Northern European instruments.[88] Idiophones such as bells and clappers served various practical purposes, such as warning of the approach of a leper.[89]

The ninth century revealed the first bagpipes, which spread throughout Europe and had many uses from folk instruments to military instruments.[90] The construction of pneumatic organs evolved in Europe starting in fifth-century Spain, spreading to England in about 700.[91] The resulting instruments varied in size and use from portable organs worn around the neck to large pipe organs.[92] Literary accounts of organs being played in English Benedictine abbeys toward the end of the tenth century are the first references to organs being connected to churches.[93] Reed players of the Middle Ages were limited to oboes; no evidence of clarinets exists during this period.[94]

Modern

[edit]Western Classical

[edit]Renaissance

[edit]Musical instrument development was dominated by the Occident from 1400 on, indeed, the most profound changes occurred during the Renaissance period.[21] Instruments took on other purposes than accompanying singing or dance, and performers used them as solo instruments. Keyboards and lutes developed as polyphonic instruments, and composers arranged increasingly complex pieces using more advanced tablature. Composers also began designing pieces of music for specific instruments.[21] In the latter half of the sixteenth century, orchestration came into common practice as a method of writing music for a variety of instruments. Composers now specified orchestration where individual performers once applied their own discretion.[95] The polyphonic style dominated popular music, and the instrument makers responded accordingly.[96]

Beginning in about 1400, the rate of development of musical instruments increased in earnest as compositions demanded more dynamic sounds. People also began writing books about creating, playing, and cataloging musical instruments; the first such book was Sebastian Virdung's 1511 treatise Musica getuscht und ausgezogen ('Music Germanized and Abstracted').[95] Virdung's work is noted as being particularly thorough for including descriptions of "irregular" instruments such as hunters' horns and cow bells, though Virdung is critical of the same. Other books followed, including Arnolt Schlick's Spiegel der Orgelmacher und Organisten ('Mirror of Organ Makers and Organ Players') the following year, a treatise on organ building and organ playing.[97] Of the instructional books and references published in the Renaissance era, one is noted for its detailed description and depiction of all wind and stringed instruments, including their relative sizes. This book, the Syntagma musicum by Michael Praetorius, is now considered an authoritative reference of sixteenth-century musical instruments.[98]

In the sixteenth century, musical instrument builders gave most instruments – such as the violin – the "classical shapes" they retain today. An emphasis on aesthetic beauty also developed; listeners were as pleased with the physical appearance of an instrument as they were with its sound. Therefore, builders paid special attention to materials and workmanship, and instruments became collectibles in homes and museums.[99] It was during this period that makers began constructing instruments of the same type in various sizes to meet the demand of consorts, or ensembles playing works written for these groups of instruments.[100]

Instrument builders developed other features that endure today. For example, while organs with multiple keyboards and pedals already existed, the first organs with solo stops emerged in the early fifteenth century. These stops were meant to produce a mixture of timbres, a development needed for the complexity of music of the time.[101] Trumpets evolved into their modern form to improve portability, and players used mutes to properly blend into chamber music.[102]

Baroque

[edit]

Beginning in the seventeenth century, composers began writing works to a higher emotional degree. They felt that polyphony better suited the emotional style they were aiming for and began writing musical parts for instruments that would complement the singing human voice.[96] As a result, many instruments that were incapable of larger ranges and dynamics, and therefore were seen as unemotional, fell out of favor. One such instrument was the shawm.[103] Bowed instruments such as the violin, viola, baryton, and various lutes dominated popular music.[104] Beginning in around 1750, however, the lute disappeared from musical compositions in favor of the rising popularity of the guitar.[105] As the prevalence of string orchestras rose, wind instruments such as the flute, oboe, and bassoon were readmitted to counteract the monotony of hearing only strings.[106]

In the mid-seventeenth century, what was known as a hunter's horn underwent a transformation into an "art instrument" consisting of a lengthened tube, a narrower bore, a wider bell, and a much wider range. The details of this transformation are unclear, but the modern horn or, more colloquially, French horn, had emerged by 1725.[107] The slide trumpet appeared, a variation that includes a long-throated mouthpiece that slid in and out, allowing the player infinite adjustments in pitch. This variation on the trumpet was unpopular due to the difficulty involved in playing it.[108] Organs underwent tonal changes in the Baroque period, as manufacturers such as Abraham Jordan of London made the stops more expressive and added devices such as expressive pedals. Sachs viewed this trend as a "degeneration" of the general organ sound.[109]

Classical and Romantic

[edit]

During the Classical and Romantic periods of music, lasting from roughly 1750 to 1900, many musical instruments capable of producing new timbres and higher volume were developed and introduced into popular music. The design changes that broadened the quality of timbres allowed instruments to produce a wider variety of expression. Large orchestras rose in popularity and, in parallel, the composers determined to produce entire orchestral scores that made use of the expressive abilities of modern instruments. Since instruments were involved in collaborations of a much larger scale, their designs had to evolve to accommodate the demands of the orchestra.[110]

Some instruments also had to become louder to fill larger halls and be heard over sizable orchestras. Flutes and bowed instruments underwent many modifications and design changes—most of them unsuccessful—in efforts to increase volume. Other instruments were changed just so they could play their parts in the scores. Trumpets traditionally had a "defective" range—they were incapable of producing certain notes with precision.[111] New instruments such as the clarinet, saxophone, and tuba became fixtures in orchestras. Instruments such as the clarinet also grew into entire "families" of instruments capable of different ranges: small clarinets, normal clarinets, bass clarinets, and so on.[110]

Accompanying the changes to timbre and volume was a shift in the typical pitch used to tune instruments. Instruments meant to play together, as in an orchestra, must be tuned to the same standard lest they produce audibly different sounds while playing the same notes. Beginning in 1762, the average concert pitch began rising from a low of 377 vibrations to a high of 457 in 1880 Vienna.[112] Different regions, countries, and even instrument manufacturers preferred different standards, making orchestral collaboration a challenge. Despite even the efforts of two organized international summits attended by noted composers like Hector Berlioz, no standard could be agreed upon.[113]

Twentieth century to present

[edit]

The evolution of traditional musical instruments slowed beginning in the 20th century.[114] Instruments such as the violin, flute, french horn, and harp are largely the same as those manufactured throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Gradual iterations do emerge; for example, the "New Violin Family" began in 1964 to provide differently sized violins to expand the range of available sounds.[115] The slowdown in development was a practical response to the concurrent slowdown in orchestra and venue size.[116] Despite this trend in traditional instruments, the development of new musical instruments exploded in the twentieth century, and the variety of instruments developed overshadows any prior period.[114]

The proliferation of electricity in the 20th century led to a new category of musical instruments: electronic instruments, or electrophones.[117] The vast majority produced in the first half of the 20th century were what Sachs called "electromechanical instruments"; they have mechanical parts that produce sound vibrations picked up and amplified by electrical components. Examples include Hammond organs and electric guitars.[117] Sachs also defined a subcategory of "radioelectric instruments" such as the theremin, which produces music through the player's hand movements around two antennas.[118]

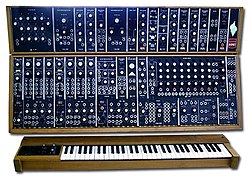

The latter half of the 20th century saw the evolution of synthesizers, which produce sound using circuits and microchips. In the late 1960s, Bob Moog and other inventors developed the first commercial synthesizers, such as the Moog synthesizer.[119] Whereas once they had filled rooms, synthesizers can now be embedded in any electronic device,[119] and are ubiquitous in modern music.[120] Samplers, introduced around 1980, allow users to sample and reuse existing sounds, and were important to the development of hip hop.[121] 1982 saw the introduction of MIDI, a standardized means of synchronizing electronic instruments.[122] The modern proliferation of computers and microchips has created an industry of electronic musical instruments.[123]

Classification

[edit]There are many different methods of classifying musical instruments. Various methods examine aspects such as the physical properties of the instrument (material, color, shape, etc.), the use for the instrument, the means by which music is produced with the instrument, the range of the instrument, and the instrument's place in an orchestra or other ensemble. Most methods are specific to a geographic area or cultural group and were developed to serve the unique classification requirements of the group.[124] The problem with these specialized classification schemes is that they tend to break down once they are applied outside of their original area. For example, a system based on instrument use would fail if a culture invented a new use for the same instrument. Scholars recognize Hornbostel–Sachs as the only system that applies to any culture and, more importantly, provides the only possible classification for each instrument.[125][126] The most common classifications are strings, brass, woodwind, and percussion.

Ancient systems

[edit]An ancient Hindu system named the Natya Shastra, written by the sage Bharata Muni and dating from between 200 BC and 200 AD, divides instruments into four main classification groups: instruments where the sound is produced by vibrating strings; percussion instruments with skin heads; instruments where the sound is produced by vibrating columns of air; and "solid", or non-skin, percussion instruments.[125] This system was similar to some degree in 12th-century Europe by Johannes de Muris, who used the terms tensibilia (stringed instruments), inflatibilia (wind instruments), and percussibilia (all percussion instruments).[127] In 1880, Victor-Charles Mahillon adapted the Natya Shastra and assigned Greek labels to the four classifications: chordophones (stringed instruments), membranophones (skin-head percussion instruments), aerophones (wind instruments), and autophones (non-skin percussion instruments).[125]

Hornbostel–Sachs

[edit]Erich von Hornbostel and Curt Sachs adopted Mahillon's scheme and published an extensive new scheme for classification in Zeitschrift für Ethnologie in 1914. Hornbostel and Sachs used most of Mahillon's system, but replaced the term autophone with idiophone.[125]

The original Hornbostel–Sachs system classified instruments into four main groups:

- Idiophones, which produce sound by vibrating the primary body of the instrument itself; they are sorted into concussion, percussion, shaken, scraped, split, and plucked idiophones, such as claves, xylophone, guiro, slit drum, mbira, and rattle.[128]

- Membranophones, which produce sound by a vibrating a stretched membrane; they may be drums (further sorted by the shape of the shell), which are struck by hand, with a stick, or rubbed, but kazoos and other instruments that use a stretched membrane for the primary sound (not simply to modify sound produced in another way) are also considered membranophones.[129]

- Chordophones, which produce sound by vibrating one or more strings; they are sorted according to the relationship between the string(s) and the sounding board or chamber. For example, if the strings are laid out parallel to the sounding board and there is no neck, the instrument is a zither whether it is plucked like an autoharp or struck with hammers like a piano. If the instrument has strings parallel to the sounding board or chamber and the strings extend past the board with a neck, then the instrument is a lute, whether the sound chamber is constructed of wood like a guitar or uses a membrane like a banjo.[130]

- Aerophones, which produce a sound with a vibrating column of air; they are sorted into free aerophones such as a bullroarer or whip, which move freely through the air; reedless aerophones such as flutes and recorders, which cause the air to pass over a sharp edge; reed instruments, which use a vibrating reed (this category may be further divided into two classifications: single-reeded and double-reeded instruments. Examples of the former are clarinets and saxophones, while the latter includes oboes and bassoons); and lip-vibrated aerophones such as trumpets, trombones and tubas, for which the lips themselves function as vibrating reeds.[131]

Sachs later added a fifth category, electrophones, such as theremins, which produce sound by electronic means.[117] Within each category are many subgroups. The system has been criticised and revised over the years, but remains widely used by ethnomusicologists and organologists.[127][132]

Schaeffner

[edit]Andre Schaeffner, a curator at the Musée de l'Homme, disagreed with the Hornbostel–Sachs system and developed his own system in 1932. Schaeffner believed that the pure physics of a musical instrument, rather than its specific construction or playing method, should always determine its classification. (Hornbostel–Sachs, for example, divides aerophones on the basis of sound production, but membranophones on the basis of the shape of the instrument). His system divided instruments into two categories: instruments with solid, vibrating bodies and instruments containing vibrating air.[133]

Range

[edit]Musical instruments are also often classified by their musical range in comparison with other instruments in the same family. This exercise is useful when placing instruments in context of an orchestra or other ensemble.

These terms are named after singing voice classifications:

- Soprano instruments: flute, violin, soprano saxophone, soprano sarrusophone, trumpet, clarinet, oboe, piccolo, glockenspiel, celesta

- Alto instruments: alto saxophone, alto sarrusophone, french horn, alto flute, english horn, alto clarinet, viola, alto horn, xylophone, vibraphone

- Tenor instruments: trombone, tenoroon, tenor saxophone, tenor sarrusophone, tenor violin, guitar, tenor drum, harpsichord, harp, marimba

- Baritone instruments: bassoon, baritone saxophone, baritone sarrusophone, bass clarinet, cello, baritone horn, euphonium

- Bass instruments: double bass, bass guitar, contrabassoon, bass saxophone, bass sarrusophone, tuba, bass drum

Some instruments fall into more than one category. For example, the cello may be considered tenor, baritone or bass, depending on how its music fits into the ensemble. The trombone and French horn may be alto, tenor, baritone, or bass depending on the range it is played in. Many instruments have their range as part of their name: soprano saxophone, tenor saxophone, baritone horn, alto flute, bass guitar, etc. Additional adjectives describe instruments above the soprano range or below the bass, for example the sopranino saxophone and contrabass clarinet. When used in the name of an instrument, these terms are relative, describing the instrument's range in comparison to other instruments of its family and not in comparison to the human voice range or instruments of other families. For example, a bass flute's range is from C3 to F♯6, while a bass clarinet plays about one octave lower.

Construction

[edit]

The materials used in making musical instruments vary greatly by culture and application. Many of the materials have special significance owing to their source or rarity. Some cultures worked substances from the human body into their instruments. In ancient Mexico, for example, the material drums were made from might contain actual human body parts obtained from sacrificial offerings. In New Guinea, drum makers would mix human blood into the adhesive used to attach the membrane.[134] Mulberry trees are held in high regard in China owing to their mythological significance—instrument makers would hence use them to make zithers. The Yakuts believe that making drums from trees struck by lightning gives them a special connection to nature.[135]

Musical instrument construction is a specialized trade that requires years of training, practice, and sometimes an apprenticeship. Most makers of musical instruments specialize in one genre of instruments; for example, a luthier makes only stringed instruments. Some make only one type of instrument such as a piano. Whatever the instrument constructed, the instrument maker must consider materials, construction technique, and decoration, creating a balanced instrument that is both functional and aesthetically pleasing.[136] Some builders are focused on a more artistic approach and develop experimental musical instruments, often meant for individual playing styles developed by the builder themself.

User interfaces

[edit]

Regardless of how the sound is produced, many musical instruments have a keyboard as the user interface. Keyboard instruments are any instruments that are played with a musical keyboard, which is a row of small keys that can be pressed. Every key generates one or more sounds; most keyboard instruments have extra means (pedals for a piano, stops and a pedal keyboard for an organ) to manipulate these sounds. They may produce sound by wind being fanned (organ) or pumped (accordion),[138][139] vibrating strings either hammered (piano) or plucked (harpsichord),[140][141] by electronic means (synthesizer),[142] or in some other way. Sometimes, instruments that do not usually have a keyboard, such as the glockenspiel, are fitted with one.[143] Though they have no moving parts and are struck by mallets held in the player's hands, they have the same physical arrangement of keys and produce soundwaves in a similar manner. The theremin, an electrophone, is played without physical contact by the player. The theremin senses the proximity of the player's hands, which triggers changes in its sound. More recently, a MIDI controller keyboard used with a digital audio workstation may have a musical keyboard and a bank of sliders, knobs, and buttons that change many sound parameters of a synthesizer.

Handedness

[edit]

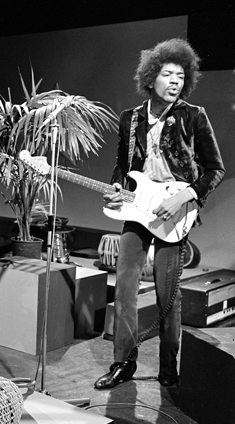

Many musical instruments are able to be played with either right of left handedness. However, some instruments can be made for the less frequent (≈10%) left handedness, such as guitars. Well known left handed players are Jimi Hendrix, Paul McCartney, and Antony Blinken.

Instrumentalist

[edit]A person who plays a musical instrument is known as an instrumentalist or instrumental musician.[144][145] Many instrumentalists are known for playing specific musical instruments such as guitarist (guitar), pianist (piano), bassist (bass), and drummer (drum). These different types of instrumentalists can perform together in a music group.[146] A person who is able to play a number of instruments is called a multi-instrumentalist.[147] According to David Baskerville in the book Music Business Handbook and Career Guide, the working hours of a full-time instrumentalist may average only three hours a day, but most musicians spent at least forty hours a week.[148]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Bagpiper, Abraham Bloemaert (1566 - 1651)". DomQuartier Salzburg, Residenzgalerie, Sammlung Online. Retrieved 29 July 2025.

- ^ Montagu 2007, p. 1

- ^ a b c d e Rault 2000, p. 9

- ^ a b Blades 1992, p. 34

- ^ Montagu 2007.

- ^ Chase & Nowell 1998, p. 549

- ^ Slovenian Academy of Sciences 1997, pp. 203–205

- ^ Canadian Broadcasting Corporation 2004

- ^ Collinson 1975, p. 10

- ^ a b Campbell, Greated & Myers 2004, p. 82

- ^ de Schauensee 2002, pp. 1–16

- ^ Moorey 1977, pp. 24–40

- ^ a b "Brookhaven Lab Expert Helps Date Flute Thought to be Oldest Playable Musical Instrument". Brookhaven National Laboratory. Archived from the original on 10 February 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2011.

- ^ "Jiahu (ca. 7000–5700 B.C.)". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. October 2000. Archived from the original on 9 August 2010. Retrieved 10 February 2011.

- ^ Zhang, Juzhong; Xiao, Xinghua; Lee, Yun Kuen (December 2004). "The early development of music. Analysis of the Jiahu bone flutes". Antiquity. 78 (302): 769–778. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00113432. ISSN 0003-598X.

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 60

- ^ Brown 2008

- ^ Baines 1993, p. 37

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 61

- ^ a b Sachs 1940, p. 63

- ^ a b c Sachs 1940, p. 297

- ^ Blades 1992, p. 36

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 26

- ^ Rault 2000, p. 34

- ^ Sachs 1940, pp. 34–52

- ^ Blades 1992, p. 51

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 35

- ^ Sachs 1940, pp. 52–53

- ^ Marcuse 1975, pp. 24–28

- ^ Sachs 1940, pp. 53–59

- ^ Caldwell, Duncan (2013). "A Possible New Class of Prehistoric Musical Instruments from New England: Portable Cylindrical Lithophones". American Antiquity. 78 (3): 520–535. doi:10.7183/0002-7316.78.3.520. S2CID 53959315.

- ^ "(PDF) Flint Tools as Portable Sound-Producing Objects in the Upper Palaeolithic Context: An Experimental Study". Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 67

- ^ Sachs 1940, pp. 68–69

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 69

- ^ Remnant 1989, p. 168

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 70

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 82

- ^ a b c Sachs 1940, p. 86

- ^ Rault 2000, p. 71

- ^ Sachs 1940, pp. 98–104

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 105

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 106

- ^ Sachs 1940, pp. 108–113

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 114

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 116

- ^ Marcuse 1975, p. 385

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 128

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 129

- ^ Campbell, Greated & Myers 2004, p. 83

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 149

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 151

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 152

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 161

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 185

- ^ Sachs 1940, pp. 162–164

- ^ Campos, Fredeliza Z.; Hull, Jennifer R.; Hồng, Vương Thu (2023). "In search of a musical past: evidence for early chordophones from Vietnam". Antiquity. 97 (391): 141–157. doi:10.15184/aqy.2022.170. ISSN 0003-598X.

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 166

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 178

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 189

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 192

- ^ Sachs 1940, pp. 196–201

- ^ "Deskford carnyx". Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ "Carnyx - Caledonians, Picts and Romans - Scotland's History". Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 207

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 218

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 216

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 221

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 222

- ^ Sachs 1940, pp. 222–228

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 229

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 231

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 236

- ^ Sachs 1940, pp. 238–239

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 240

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 246

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 249

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 250

- ^ Sachs 1940, pp. 251–254

- ^ a b Sachs 1940, p. 260

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 263

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 265

- ^ Kartomi 1990, p. 124

- ^ Grillet 1901, p. 29

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 269

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 271

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 274

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 273

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 278

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 281

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 284

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 286

- ^ Bicknell 1999, p. 13

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 288

- ^ a b Sachs 1940, p. 298

- ^ a b Sachs 1940, p. 351

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 299

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 301

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 302

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 303

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 307

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 328

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 352

- ^ Sachs 1940, pp. 353–357

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 374

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 380

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 384

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 385

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 386

- ^ a b Sachs 1940, p. 388

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 389

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 390

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 391

- ^ a b Remnant 1989, p. 183

- ^ Remnant 1989, p. 70

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 445

- ^ a b c Sachs 1940, p. 447

- ^ Sachs 1940, p. 448

- ^ a b Pinch & Trocco 2004, p. 7

- ^ "The 14 most important synths in electronic music history – and the musicians who use them". FACT Magazine: Music News, New Music. 15 September 2016. Archived from the original on 2 November 2019. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- ^ McNamee, David (28 September 2009). "Hey, what's that sound: Sampler". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 4 March 2014. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ Bateman, Tom (28 November 2012). "How MIDI changed the world of music". BBC News. Archived from the original on 27 April 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ Manning 2004, pp. 268–270

- ^ Montagu 2007, p. 210

- ^ a b c d Montagu 2007, p. 211

- ^ Kartomi 1990, p. 176

- ^ a b Rault 2000, p. 190

- ^ Marcuse 1975, p. 3

- ^ Marcuse 1975, p. 117

- ^ Marcuse 1975, p. 177

- ^ Marcuse 1975, p. 549

- ^ Campbell, Greated & Myers 2004, p. 39

- ^ Kartomi 1990, pp. 174–175

- ^ Rault 2000, p. 184

- ^ Rault 2000, p. 185

- ^ Rault 2000, p. 195

- ^ Organ built by M. P. Moller, 1940. USNA Music Department Archived 6 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine. United States Naval Academy. Retrieved on 2008-03-04.

- ^ Bicknell, Stephen (1999). "The organ case". In Thistlethwaite, Nicholas & Webber, Geoffrey (Eds.), The Cambridge Companion to the Organ, pp. 55–81. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-57584-2

- ^ Howard, Rob (2003) An A to Z of the Accordion and related instruments Stockport: Robaccord Publications ISBN 0-9546711-0-4

- ^ Fine, Larry. The Piano Book, 4th ed. Massachusetts: Brookside Press, 2001. ISBN 1-929145-01-2

- ^ Ripin (Ed) et al. Early Keyboard Instruments. New Grove Musical Instruments Series, 1989, PAPERMAC

- ^ Paradiso, JA. "Electronic music: new ways to play". Spectrum IEEE, 34(2):18–33, Dec 1997.

- ^ "Glockenspiel: Construction". Vienna Symphonic Library. Archived from the original on 30 April 2010. Retrieved 17 August 2009.

- ^ "Definition of instrumentalist". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 13 January 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ "Instrumental Musician". Government of Alberta. Archived from the original on 18 January 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ Serna, Desi (2013). Guitar Theory For Dummies: Book + Online Video & Audio Instruction. John Wiley & Sons. p. 271. ISBN 9781118646939. Archived from the original on 15 November 2023. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ^ "Definition of Multi-Instrumentalist". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 13 January 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ Baskerville, David (2006). Music Business Handbook and Career Guide. SAGE Publishing. pp. 469–471. ISBN 9781412904384. Archived from the original on 15 November 2023. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

References

[edit]- Baines, Anthony (1993), Brass Instruments: Their History and Development, Dover Publications, ISBN 978-0-486-27574-1

- Bicknell, Stephen (1999), The History of the English Organ, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-65409-8

- Blades, James (1992), Percussion Instruments and Their History, Bold Strummer Ltd, ISBN 978-0-933224-61-2

- Brown, Howard Mayer (2008), Sachs, Curt, Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, retrieved 5 June 2008

- Campbell, Murray; Greated, Clive A.; Myers, Arnold (2004), Musical Instruments: History, Technology, and Performance of Instruments of Western Music, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-816504-0

- Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (30 December 2004), Archeologists discover ice age dwellers' flute, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, archived from the original on 13 August 2010, retrieved 7 February 2009

- Chase, Philip G.; Nowell, April (August–October 1998), "Taphonomy of a Suggested Middle Paleolithic Bone Flute from Slovenia", Current Anthropology, 39 (4): 549, doi:10.1086/204771, S2CID 144800210

- Collinson, Francis M. (1975), The Bagpipe, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-7100-7913-8

- de Schauensee, Maude (2002), Two Lyres from Ur, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, ISBN 978-0-924171-88-8

- Grillet, Laurent (1901), Les ancetres du violon v.1, Paris

- Kartomi, Margaret J. (1990), On Concepts and Classifications of Musical Instruments, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-42548-1

- Manning, Peter (2004), Electronic and Computer Music, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-517085-6

- Marcuse, Sibyl (1975), A Survey of Musical Instruments, Harper & Row, ISBN 978-0-06-012776-3

- Montagu, Jeremy (2007), Origins and Development of Musical Instruments, The Scarecrow Press, ISBN 978-0-8108-5657-8

- Moorey, P.R.S. (1977), "What Do We Know About the People Buried in the Royal Cemetery?", Expedition, 20 (1): 24–40

- Pinch, Revor; Trocco, Frank (2004), Analog Days: The Invention and Impact of the Moog Synthesizer, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-01617-0

- Rault, Lucie (2000), Musical Instruments: A Worldwide Survey of Traditional Music-making, Thames & Hudson Ltd, ISBN 978-0-500-51035-3

- Remnant, Mary (1989), Musical Instruments: An Illustrated History from Antiquity to the Present, Batsford, ISBN 978-0-7134-5169-6

- Sachs, Curt (1940), The History of Musical Instruments, Dover Publications, ISBN 978-0-486-45265-4

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Slovenian Academy of Sciences (11 April 1997), "Early Music", Science, 276 (5310): 203–205, doi:10.1126/science.276.5310.203g, S2CID 220083771

Further reading

[edit]- Wade-Matthews, Max (2003). Musical Instruments: Illustrated Encyclopedia. Lorenz. ISBN 978-0-7548-1182-4.

- Music Library Association (1974). Committee on Musical Instrument Collections. A Survey of Musical Instrument Collections in the United States and Canada, conducted by a committee of the Music Library Association, William Lichtenwanger, chairman & compiler, ed. and produced by James W. Pruitt. Ann Arbor, Mich.: Music Library Association. xi, p. 137, ISBN 0-914954-00-8

- West, M.L. (May 1994). "The Babylonian Musical Notation and the Hurrian Melodic Texts". Music & Letters. 75 (2): 161–179. doi:10.1093/ml/75.2.161.

- Young, Phillip T. (1980). The Look of Music: Rare Musical Instruments, 1500–1900. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780919253001.

External links

[edit]- "Musical Instruments". Furniture. Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 1 July 2008.