Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Harry Flashman

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2015) |

| Harry Flashman | |

|---|---|

| The Flashman Papers character | |

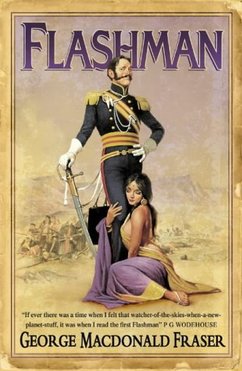

Cover illustration of Flashman by Gino D'Achille (2005 printing) | |

| First appearance | "Tom Brown's School Days" |

| Last appearance | "Flashman on the March" |

| Created by | Thomas Hughes |

| Portrayed by | Malcolm McDowell (Royal Flash) |

| In-universe information | |

| Full name | Harry Paget Flashman |

| Gender | Male |

| Family | Henry Buckley Flashman (father) Lady Alicia Paget (mother) |

| Spouse | Elspeth Morrison Irma, Grand Duchess of Strackenz Susie Willinck |

| Relatives | Jack Flashman (great-grandfather) |

| Nationality | British |

Sir Harry Paget Flashman VC, KCB, KCIE is a fictional character created by Thomas Hughes (1822–1896) in the semi-autobiographical Tom Brown's School Days (1857) and later developed by George MacDonald Fraser (1925–2008). Harry Flashman appears in a series of 12 of Fraser's books, collectively known as The Flashman Papers, with covers illustrated by Arthur Barbosa and Gino D'Achille. Flashman was played by Malcolm McDowell in the Richard Lester 1975 film Royal Flash.[1]

In Tom Brown's School Days (1857), Flashman is portrayed as a notorious Rugby School bully who persecutes Tom Brown and is finally expelled for drunkenness, at which point he simply disappears. Fraser decided to write the story of Flashman's later life, in which the school bully would be identified as an "illustrious Victorian soldier", experiencing many of the 19th-century wars and adventures of the British Empire and rising to high rank in the British Army, to be acclaimed as a great warrior, while still remaining "a scoundrel, a liar, a cheat, a thief, a coward—and, oh yes, a toady."[2] In the papers—which are purported to have been written by Flashman and discovered only after his death—he describes his own dishonourable conduct with complete candour. Fraser's Flashman is an antihero who often runs away from danger. Nevertheless, through a combination of luck and cunning, he usually ends each volume acclaimed as a hero.[3]

Flashman's origins

[edit]Fraser gave Flashman a lifespan from 1822 to 1915 and a birth-date of 5 May. He also provided Flashman's first and middle names, as Hughes's novel had given Flashman only one, using the names to make an ironic allusion to Henry Paget, 1st Marquess of Anglesey. Paget was one of the heroes of Waterloo, who cuckolded the Duke of Wellington's brother Henry Wellesley and later—in one of the period's more celebrated scandals—married Lady Anglesey, after Wellesley had divorced her for adultery.[4]

In Flashman, Flashman says that his great-grandfather, Jack Flashman, made the family fortune in America, trading in rum, slaves and "piracy too, I shouldn't wonder". Despite their wealth, the Flashmans "were never the thing"; Flashman quotes the diarist Henry Greville's comment that "the coarse streak showed through, generation after generation, like dung beneath a rosebush". Harry Flashman's equally fictional father, Henry Buckley Flashman, appears in Black Ajax (1997). Buckley, a bold young officer in the British cavalry, is said to have been wounded in action at Talavera in 1809, and then to have gained access to "society" by sponsoring bare-knuckle boxer Tom Molineaux (the first black man to contend for a championship). The character subsequently marries Flashman's mother Lady Alicia Paget, a fictional relation of the real Marquess of Anglesey. Buckley, it is related, also served as a Member of Parliament (MP) but was "sent to the knacker's yard at Reform". Beside politics, the older Flashman character has interests including drinking, fox hunting (riding to hounds), and women.

Character

[edit]Flashman is a large man, six feet two inches (1.88 m) tall and close to 13 stone (about 180 pounds or 82 kg). In Flashman and the Tiger, he mentions that one of his grandchildren has black hair and eyes, resembling him in his younger years. His dark colouring frequently enabled him to pass (in disguise) for a Pashtun. He claims only three natural talents: horsemanship, facility with foreign languages, and fornication. He becomes an expert cricket-bowler, but only through hard effort (he needed sporting credit at Rugby School, and feared to play rugby football). He can also display a winning personality when he wants to, and is very skilled at flattering those more important than himself without appearing servile.

As he admits in the Papers, Flashman is a coward, who will flee from danger if there is any way to do so, and has on some occasions collapsed in funk. He has one great advantage in concealing this weakness: when he is frightened, his face turns red, rather than white, so that observers think he is excited, enraged, or exuberant—as a hero ought to be.

After his expulsion from Rugby School for drunkenness, the young Flashman looks for an easy life. He has his wealthy father buy him an officer's commission in the fashionable 11th Regiment of Light Dragoons. The 11th, commanded by Lord Cardigan, later involved in the Charge of the Light Brigade, has just returned from India and are not likely to be posted abroad soon. Flashman throws himself into the social life that the 11th offered and becomes a leading light of Canterbury society. In 1840 the regiment is converted to Hussars with an elegant blue and crimson uniform, which assists Flashman in attracting female attention for the remainder of his military career.[5]

A duel with another officer over a French courtesan leads to his being temporarily stationed in Paisley, Scotland. There he meets and deflowers Elspeth Morrison, daughter of a wealthy textile manufacturer, whom he has to marry in a "shotgun wedding" under threat of a horsewhipping by her uncle. But marriage to the daughter of a mere businessman forces his transferral from the snobbish 11th Hussars. He is sent to India to make a career in the army of the East India Company. Unfortunately, his language talent and his habit of flattery bring him to the attention of the Governor-General. The Governor does him the (very much unwanted) favour of assigning him as aide to General Elphinstone in Afghanistan.

Flashman survives the ensuing retreat from Kabul (the worst British military debacle of Victoria's reign) by a mixture of sheer luck and unstinting cowardice. He becomes an unwitting hero: the defender of Piper's Fort, where he is the only surviving white man, and is found by the relieving troops clutching the flag and surrounded by enemy dead. Of course, Flashman had arrived at the fort by accident, collapsed in terror rather than fighting, been forced to stand and show fight by his subordinate, and is 'rumbled' for a complete coward. He had been trying to surrender the colours, not defend them. Happily for him, all inconvenient witnesses had been killed.

This incident sets the tone for Flashman's life. Over the following 60 years or so, he is involved in many of the major military conflicts of the 19th century—always in spite of his best efforts to evade his duty. He is often selected for especially dangerous jobs because of his heroic reputation. He meets many famous people, and survives some of the worst military disasters of the period (the First Anglo-Afghan War, the Charge of the Light Brigade, the Siege of Cawnpore, the Battle of the Little Bighorn, and the Battle of Isandlwana), always coming out with more heroic laurels. The date of his last adventure seems to have been around 1900, being involved in the Boxer Rebellion alongside US Marines.[6] He dies in 1915.

Despite his admitted cowardice, Flashman is a dab hand at fighting when he has to. Though he dodges danger as much as he can, and runs away when no one is watching, after the Piper's Fort incident, he usually controls his fear and often performs bravely. Almost every book contains one or more incidents where Flashman has to fight or perform some other daring action, and he holds up long enough to complete it. For instance, he is ordered to accompany the Light Brigade on its famous charge and rides all the way to the Russian guns. However, most of these acts of 'bravery' are performed only when he has absolutely no choice and to do anything else would result in his being exposed as a coward and losing his respected status in society, or being shot for desertion. When he can act like a coward with impunity, he invariably does.

Flashman surrenders to fear in front of witnesses only a few times, and is never caught out again. During the siege of Piper's Fort, in the first novel, Flashman cowers weeping in his bed at the start of the final assault; the only witness to this dies before relief comes. He breaks down while accompanying Rajah Brooke during a battle with pirates, but the noise drowns out his blubbering, and he recovers enough to command a storming party of sailors (placing himself right in the middle of the party, to avoid stray bullets). After the Charge of the Light Brigade, he flees in panic from the fighting in the battery—but mistakenly charges into an entire Russian regiment, adding to his heroic image.

In spite of his numerous character flaws, Flashman is represented as being a perceptive observer of his times ("I saw further than most in some ways"[7]). In its obituary[8] of George MacDonald Fraser, The Economist commented that realistic sharp-sightedness ("if not much else") was an attribute Flashman shared with his creator.[9]

Relationships

[edit]Flashman, an insatiable lecher, has sex with many different women over the course of his fictional adventures. His size, good looks, winning manner, and especially his splendid cavalry-style whiskers win over women from low to high, and his dalliances include famous ladies along with numerous prostitutes. In Flashman and the Great Game, about halfway through his life, he counted up his sexual conquests while languishing in a dungeon at Gwalior, "not counting return engagements", reaching a total of 478 up to that date (similar—albeit not equal—to the tally made by Mozart's Don Giovanni in the famous aria of Giovanni's henchman, Leporello). Passages in Royal Flash, Flashman and the Mountain of Light, Flashman and the Dragon, Flashman and the Redskins, and Flashman and the Angel of the Lord suggest that Flashman was well endowed.

He was a vigorous and exciting (if sometimes selfish and rapacious) lover, and some of his partners became quite fond of him—though by his own admission, others tried to kill him afterwards. The most memorable of these was Cleonie, a prostitute Flashman sold into slavery in Flashman and the Redskins. He was not above forcing himself on a partner by blackmail (e.g., Phoebe Carpenter in Flashman and the Dragon), and at least twice raped women (Narreeman, an Afghan dancing girl in Flashman, and an unnamed harem girl in Flashman's Lady).

Flashman's stories are dominated by his numerous amorous encounters. Several of them are with prominent historical personages. These women are sometimes window dressing, sometimes pivotal characters in the unpredictable twists and turns of the books. Historical women Flashman bedded included:

- Lola Montez (Marie Dolores Eliza Rosanna Gilbert James; Royal Flash).

- Jind Kaur, Dowager Maharani of Punjab (Flashman and the Mountain of Light).

- Lillie Langtry, actress and mistress of Edward VII (Flashman and the Tiger)

- Daisy Brooke, socialite and mistress of Edward VII (Flashman and the Tiger)

- Mangla, maid and confidant to Jind Kaur (Flashman and the Mountain of Light).

- Masteeat, Queen of the Wollo Gallas (Flashman on the March).

- Queen Ranavalona I of Madagascar (Flashman's Lady).

- The Silk One (aka Ko Dali's daughter), consort of Yakub Beg (Flashman at the Charge).

- Yehonala, Imperial Chinese concubine, later the Empress Dowager Cixi (Flashman and the Dragon).

- Lakshmibai, (Possibly) Rani of Jhansi and leader of the Indian Mutiny (Flashman in the Great Game).

He also lusted after (but never bedded):

- Fanny Duberly, a famous army wife (Flash for Freedom!).

- Angela Burdett-Coutts, who became the richest woman in England in her twenties. She nearly dislocated his thumb repelling a "friendly grope" at a house-party (Flashman's Lady).

- Florence Nightingale, a famous nurse and social reformer (Flashman in the Great Game).

- Agnes Salm-Salm, the American wife of German Prince Felix Salm-Salm, an associate in his doomed attempts to save Maximilian I of Mexico (Flashman on the March).

His fictional amours included:

- Judy Parsons, his father's mistress (Flashman). After a single bedding to satisfy joint lust, she and Flashman achieve a state of mutual dislike.

- Josette, mistress of Captain Bernier of the 11th Light Dragoons (Flashman).

- Elspeth Rennie Morrison, his wife.

- Fetnab, a dancing girl Flashy bought in Calcutta (Flashman) to teach him Hindustani, Hindi culture and purportedly ninety-seven ways of love making. Sold to a major in the artillery when Flashman is posted to Afghanistan.

- Mrs Betty Parker, wife of an officer of Bengal Light Cavalry (Flashman; unconsummated). Cited by Flashman as an example of the "inadequacies of education given to young Englishwomen" in the Victorian era.

- Baroness Pechmann, a Bavarian noblewoman (Royal Flash).

- Irma, Grand Duchess of Strackenz (Royal Flash). For involved political reasons Flashman marries her, in the guise of a Danish prince. After an unpromising start the cold and highly-strung Duchess becomes physically infatuated with him. Decades later she pays an official visit to Queen Victoria. Flashman, by now an aging courtier, observes his erstwhile royal spouse from a safe distance.

- An-yat-heh, an undercover agent of Harry Smith Parkes (Flashman and the Dragon).

- Aphrodite, one of Miss Susie's "gels" (Flashman and the Redskins).

- Cassy, an escaped slave who accompanied Flashman up the Mississippi (Flash for Freedom!).

- Caprice, a French intelligence agent (Flashman and the Tiger)

- Lady Geraldine (Flashman and the Dragon, mentioned)

- Gertrude, niece of Admiral Tegetthoff (Flashman on the March).

- Princess "Kralta", European princess and agent of Otto von Bismarck (Flashman and the Tiger)

- Cleonie Grouard (aka Mrs Arthur B. Candy), one of "Miss Susie's gels" (Flashman and the Redskins). With her he had a son, Frank Grouard.

- Mrs Leo Lade, mistress of a violently jealous duke (Flashman's Lady).

- "Lady Caroline Lamb", a slave on board the slaver Balliol College (Flash for Freedom!).

- Mrs Leslie, an unattached woman in the Meerut garrison (Flashman in the Great Game).

- Mrs Madison (Flashman and the Mountain of Light).

- Malee, a servant of Uliba-Wark (Flashman on the March).

- Annette Mandeville, a Mississippi planter's wife (Flash for Freedom! and again in Flashman and the Angel of the Lord).

- Penny/Jenny, a steamboat girl (Flash for Freedom!).

- Lady Plunkett, wife of a colonial judge (not quite consummated: Flashman and the Angel of the Lord).

- Hannah Poppelwell, agent of a Southern slaveholders' conspiracy (Flashman and the Angel of the Lord).

- Sara (Aunt Sara), sister-in-law of Count Pencherjevsky (Flashman at the Charge). Shares violent love-making with Flashman in a Russian steam-bath. Believed to be victim of a subsequent serf rising.

- Sonsee-Array (Takes-Away-Clouds-Woman), an Apache savage 'princess', daughter of Mangas Coloradas and Flashman's fourth wife (Flashman and the Redskins).

- Miranda Spring, daughter of John Charity Spring (Flashman and the Angel of the Lord).

- Szu-Zhan, a six-foot-eight Chinese bandit leader (Flashman and the Dragon).

- Uliba-Wark, an Abyssinian chieftainess and warrior (Flashman on the March).

- Valentina (Valla), married daughter of Russian nobleman and Cossack colonel Count Pencherjevsky (Flashman at the Charge). Has an affair with Flashman at her father's instigation. When charged with saving Valla from a rebellion of Pencherjevsky's serfs, Flashman attempts to escape pursuit by throwing her into the snow from a troika.

- White Tigress and Honey-and-Milk, two concubines of the Chinese merchant Whampoa (Flashman's Lady).

- Susie Willinck (aka "Miss Susie"), New Orleans madam and Flashman's third wife (Flash for Freedom! and Flashman and the Redskins).

- Madame Sabba, his "guide" at the Temple of Heaven, actually the lure in a robbery scheme (Flashman's Lady, unconsummated).

- Mam'selle Bomfomtalbellilaba, a guest at one of Ranavalona I of Madagascar's parties (Flashman's Lady, unconsummated).

- Hermia, an African-American slave (Flash for Freedom!).

- Phoebe Carpenter, the wife of a British clergyman in China (Flashman and the Dragon, unconsummated)

As well as bedding more or less any lass available, he married whenever it was politic to do so. During a posting to Scotland, he was forced to marry Elspeth to avoid "pistols for two with her fire-breathing uncle". He is still married to her decades later when writing the memoirs, though that does not stop him pursuing others. Nor does it prevent marrying them when his safety seems to require it; he marries Duchess Irma in Royal Flash and in Flashman and the Redskins he marries Susie Willnick as they escape New Orleans, and Sonsee-Array a few months later.

He was also once reminded of a woman that Elspeth claimed he flirted with named Kitty Stevens, though Flashman was unable to remember her.

He had a special penchant for royal ladies, and noted that his favourite amours (apart from his wife) were Lakshmibai, Ci Xi and Lola Montez: "a Queen, an Empress, and the foremost courtesan of her time: I dare say I'm just a snob." He also noted that, while civilized women were more than ordinarily partial to him, his most ardent admirers were among the savage of the species: "Elspeth, of course, is Scottish." And for all his raking, it was always Elspeth to whom he returned and who remained ultimately top of the list.

His lechery was so strong that it broke out even in the midst of rather hectic circumstances. While accompanying Thomas Henry Kavanagh on his daring escape from Lucknow, he paused for a quick rattle with a local prostitute, and during the battle of [[]], he found himself galloping one of Sharif Sahib's concubines without even realizing it but nonetheless continued to the climax of the battle and the tryst.

Flashman's relations with the highest-ranking woman of his era, Queen Victoria, are warm but platonic. He first meets her in 1842 when he receives a medal for his gallantry in Afghanistan[10] and reflects on what a honeymoon she and Prince Albert must have enjoyed. Subsequently, he and his wife received invitations to Balmoral Castle, to the delight of the snobbish Elspeth.[11] For his services during the Indian Mutiny, Victoria not only approved awarding Flashy the Victoria Cross, but loaded the KCB on top of it.[12]

Appearances

[edit]The Flashman Papers

[edit]Film

[edit]In 1975, Malcolm McDowell played Harry Flashman in Royal Flash, directed by Richard Lester. An earlier attempt by Lester to film the novel Flashman was unsuccessful; John Alderton had been cast in the role.[13]

References in other works

[edit]- In the Jackson Speed Memoirs, Robert Peecher borrows heavily from George MacDonald Fraser's Flashman in creating the Jackson Speed character.[14] Like Flashman, Speed is a womanizer and a coward who is undeservedly marked as a hero by those around him. Peecher also adopts the literary device used by Fraser of the "discovered" memoirs. Unlike the English Flashman, Speed is an American making appearances in the Mexican–American War, the U.S. Civil War, and other American conflicts of the 19th century.

- Writer Keith Laidler gave the Flashman story a new twist in The Carton Chronicles by revealing that Flashman is the natural son of Sydney Carton, hero of the Charles Dickens classic A Tale of Two Cities. Laidler has Sydney Carton changing his mind at the foot of the guillotine, escaping death and making wayward and amorous progress through the terrors of the French Revolution, during which time he spies for both the British and French, causes Danton's death, shoots Robespierre, and reminisces on a liaison among the hayricks at the "Leicestershire pile" of a married noblewoman, who subsequently gave birth to a boy—Flashman—on 5 May 1822.[15][16]

- Sandy Mitchell's Warhammer 40,000 character Commissar Ciaphas Cain is partially inspired by Flashman.[17]

- In comics, writer John Ostrander took Flashman as his model for his portrayal of the cowardly villain Captain Boomerang in the Suicide Squad series. In the letters page to the last issue in the series (#66), Ostrander acknowledges this influence directly. Flashman's success with the ladies is noticeably lacking in the Captain Boomerang character.

- In Kim Newman's alternative history novel The Bloody Red Baron (part of the Anno Dracula series), Flashman is cited as an example of a dishonourable officer in a character's internal monologue. In the later novella Aquarius (set in 1968, one year before the first volume of the Flashman Papers was published), it is mentioned that the fictional St Bartolph's College at the University of London had previously been home to the Harry Paget Flashman Refectory, until its recent renaming to Che Guevara Hall in an attempt to pacify campus activists.

- Flashman's portrait (unnamed, but with unmistakable background and characteristics) hangs in the home of the protagonist of The Peshawar Lancers, an alternative history novel by S. M. Stirling: the family claims to have had an ancestor who held Piper's Fort, as Flashman did; the protagonist claims his sole talents are for horsemanship and languages and has an Afghan in his service named "Ibrahim Khan" (cf. Ilderim Khan, Flashman's Afghan blood brother and servant); late in the book, he plays with Elias the Jew on a "black jade chess set" matching the description of the one Flashman stole from the Summer Palace in Flashman and the Dragon; the book's chief antagonist is named Ignatieff, a reference to Flashman's Russian nemesis Nikolai Ignatieff. Another allusion to Flashman by Stirling occurs in his short story "The Charge of Lee's Brigade", which appeared in the alternative history anthology Alternate Generals (1998, ed. by Harry Turtledove). Here, Sir Robert E. Lee is a British general in the Crimean War who orders an officer, obviously Flashman (cherrypicker trousers, rides like a Comanche in battle), to take part in a better-planned Charge of the Light Brigade. Flashman dies in the attack, demonstrating some courage despite what Lee perceives only as nervousness. So, in this version Flashman again ends up a hero. But—as he himself would have been quick to point out—he is a dead hero.

- Terry Pratchett was a fan of the Flashman series[18] and the Discworld character Rincewind is an inveterate coward with a talent for languages who is always running away from danger, but nevertheless through circumstance emerges with the appearance of an unlikely hero, for which reason he is then selected for further dangerous enterprises. In this he strongly resembles Flashman, although he is totally dissimilar in most other aspects[according to whom?]. The word "Rince" means an object that moves quickly so "Rincewind" may be a play on the name the Apache gave to Flashman which was shortened to "Windbreaker" from the full "White-Rider-Goes-So-Fast-He-Destroys-the-Wind-with-His-Speed". The Discworld novel Pyramids has a character named Fliemoe, the bully at the Ankh-Morpork Assassins' Guild school, who is a parody of the original version of Flashman from Tom Brown's Schooldays (including "toasting" new boys).[19] In the Assassins' Guild Yearbook and Diary, Fliemoe is described as having grown up to be "an unbelievable liar and an unsuccessful bully". His name is a play on that of Flashman's crony Speedicut—both "Speedicut" and "Flymo" are brand names of lawn mowers.

- An editorial piece in the 14 May 2011 edition of The Guardian newspaper on the subject of British Prime Minister David Cameron being labelled a "Flashman" was given a Harry Flashman by-line and was written in the style of Flashman's narrative.[20]

- Flashman's son, Harry II, is used as a character in some of the short stories created for the "Tales of the Shadowmen" series. He first appeared in the eighth volume. His son has several of the characteristics of his father, but appears to be less a coward.

- Flashman appears as a minor character in the novel Dickens of the Mounted by Eric Nicol. This novel is a fictionalized account of Francis Dickens and, like the Flashman books, is written in the form of a discovered memoir.

- Flashman is a character in Snooks North and South and Snooks The Presidents' Man by Peter Brian. The protagonist of these books is Snooks, who is another character from Tom Brown's School Days. In Brian's books, Snooks participates in the American Civil War under disreputable circumstances and conceals his identity by using Harry Flashman's name. So the events that would be attributed to Flashman actually occurred to Snooks.

- There is a card for Flashman in Pax Pamir, a board game about the Great Game. In the first Flashman novel, he is in Afghanistan for the First Anglo-Afghan War and participates in the British retreat from Kabul.

- Comic artist Mike Dorey created the character ‘Cadman the Fighting Coward' for The Victor who was based on Flashman. Gerald Cadman, originally of Prince Rupert's Horse “The Fighting 43rd”, was a cowardly and dishonest officer during the first world war. Like Flashman his cowardice did not stop him from winning many medals, including the Victoria Cross, the DSO, MC and various foreign decorations, none of which he deserved.[21]

- Blackadder, a noted BBC period sitcom series produced in the 1980s features 'Lord Flashheart', a womanising military hero whose character is heavily inspired by Flashman. Unlike Flashman, however, Lord Flashheart is portrayed as legitimately heroic, if incredibly egotistical.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Ebert, Roger. "Royal Flash movie review & film summary (1975) | Roger Ebert". rogerebert.com. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- ^ Fraser, G.M. (1969). Flashman. London: Barrie & Jenkins.

- ^ "George MacDonald Fraser [obituary]". The Economist. 2008.

- ^ George III et al., Arthur Aspinall, ed., The Later Correspondence of George III (Cambridge University Press, 1962), p. 293

- ^ Flashman, pp. 46 and 50.

- ^ Mr American

- ^ Flashman, p. 49.

- ^ "George MacDonald Fraser". The Economist. 10 January 2008.

- ^ The Economist, 10 January 2008.

- ^ Flashman, p. 247.

- ^ Flashman in the Great Game, pp. 1, 9, and 12.

- ^ Flashman in the Great Game

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (26 September 2025). "Claudia Cardinale's Ten Top Hollywood Films". Filmink. Retrieved 26 September 2025.

- ^ robpeecher (24 May 2013). "Harry Flashman and Jackson Speed".

- ^ Aziloth Books The Carton Chronicles: The Curious Tale of Flashman's true father "Welcome to Aziloth Books". Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- ^ Laidler, Keith, The Carton Chronicles: The Curious Tale of Flashman's True Father (Aziloth, 2010, ISBN 978-1-907523-01-4).

- ^ Mitchell, Sandy (30 April 2007). Ciaphas Cain, Hero of the Imperium. The Black Library. ISBN 978-1-84416-466-0.

- ^ "In the Words of the Master..." Archived from the original on 17 June 2011. Retrieved 5 October 2010. Excerpts from interviews with Terry Pratchett

- ^ "Annotated Pratchett File—Pyramids". Archived from the original on 10 March 2007. Retrieved 5 October 2010.

- ^ "Unthinkable? Flashman and the Prime Minister—Editorial". The Guardian. London. 14 May 2011.

- ^ Mike Dorey (10 February 1973). "Cadman the Fighting Coward". mikedorey.co.uk. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- Cannadine, David (9 December 2005). "How I Inspired Thatcher". BBC News. Retrieved 20 July 2010.

- Crampton, Robert (2 July 2022). "Rereading Flashman by George MacDonald Fraser". The Times. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- Ramsay, Allan (June 2003). "Flashman and the Victorian Social Conscience". Contemporary Review.

- Turner, E. S. (20 August 1992). "E.S. Turner shocks the sensitive". London Review of Books. pp. 10–11. ISSN 0260-9592. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

Harry Flashman

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Creation

Inspiration from Tom Brown's School Days

Harry Flashman first appeared as a minor character in Thomas Hughes' 1857 novel Tom Brown's School Days, a semi-autobiographical account of life at Rugby School under headmaster Thomas Arnold.[7] In the book, Flashman is depicted as a sixth-former around 17 years old, serving as the primary antagonist and school bully who terrorizes younger boys, including protagonist Tom Brown and his friend Harry East.[8] His traits include habitual drunkenness, cruelty, and a domineering presence enforced through physical intimidation and alliances with other older boys; he is ultimately expelled after being caught in a public inebriated brawl on the street.[9] Hughes portrays Flashman as a symbol of moral corruption and the excesses of unbridled youth, contrasting him with the virtuous ideals of Arnold's Christian muscularity that shape Tom's development.[10] George MacDonald Fraser, reading Hughes' novel as a boy, identified untapped potential in Flashman as a vehicle for exploring Victorian history from an irreverent, insider perspective.[5] Rather than the heroic mold of traditional adventure tales, Fraser envisioned Flashman as an adult anti-hero whose public acclaim for bravery masked private cowardice, lechery, and self-interest—traits hinted at in Hughes' bully but expanded into a full character study.[11] This inspiration led Fraser to frame the Flashman Papers as purportedly discovered Victorian memoirs, with the 1969 novel Flashman picking up immediately after the character's Rugby expulsion, thrusting him into the First Anglo-Afghan War (1839–1842).[12] Fraser's approach preserved Hughes' core depiction of Flashman as a "brute" and drunkard while inverting narrative expectations: the bully becomes an unreliable narrator whose "heroic" exploits reveal historical events' absurdities and the era's hypocrisies through unvarnished personal failings.[13] Fraser explicitly credited the brief sketch in Tom Brown's School Days—spanning just a few chapters—as the seed for the entire series, noting how Hughes' offhand mention of Flashman's later military career sparked curiosity about his survival despite evident flaws.[14] This reclamation transformed a cautionary villain into a lens for causal realism in imperial history, emphasizing how competence often arose from accident rather than virtue, without romanticizing the character's vices.[10] The result was a series that humanized Victorian adventurism by grounding it in empirical details of battles, politics, and social norms, drawn from primary sources, while subverting the moral didacticism of Hughes' original work.[7]George MacDonald Fraser's Development of the Series

George MacDonald Fraser, a Scottish author and former soldier in the Border Regiment during World War II, conceived the Flashman series in the years following his military service, drawing inspiration from the minor character Flashman in Thomas Hughes's 1857 novel Tom Brown's School Days.[15] Wondering what became of the expelled Rugby bully—a drunken, cowardly cad—Fraser imagined him enlisting in the British Army and stumbling through Victorian imperial adventures via sheer luck and self-interest, rather than heroism.[16] This premise allowed Fraser to subvert conventions of historical adventure fiction, portraying Flashman as an unreliable narrator whose first-person "memoirs" reveal unflattering truths about empire, warfare, and human nature.[5] In the mid-1960s, frustrated with his career in journalism, Fraser began writing the debut novel Flashman, set during the First Anglo-Afghan War of 1839–1842 and centering on the disastrous Retreat from Kabul, an event Fraser researched using primary sources like Lady Sale's journals for authenticity.[5] The book was published in 1969 by Barrie & Jenkins in the United Kingdom, framed as the first installment of the "Flashman Papers"—fictional manuscripts purportedly discovered in an attic trunk and edited by a scholarly persona of Fraser himself, complete with annotations and historical notes to blend fact and invention seamlessly.[17] This editorial device enabled Fraser to interweave real figures like Arthur Wellesley and events such as the Charge of the Light Brigade into subsequent volumes, prioritizing causal fidelity to history over anachronistic moralizing.[5] Fraser developed the series episodically, producing 11 novels and one short-story collection (Flashman and the Tiger, 1999) over nearly four decades, with each book spanning discrete periods of Flashman's life from the 1840s to the 1890s, such as the American Civil War in Flash for Freedom! (1971) or the Taiping Rebellion in Flashman and the Dragon (1985).[18] His method emphasized exhaustive archival research—visiting battlefields, consulting regimental records, and cross-verifying timelines—to ensure events unfolded realistically, even as Flashman's cowardice propelled the narrative; Fraser occasionally acknowledged minor errors, like a date discrepancy in one volume, corrected via reader correspondence.[5] The final novel, Flashman on the March (2005), explored the Abyssinian Campaign, after which Fraser, citing health issues, ceased writing despite outlines for unfinished tales.[5] This incremental expansion reflected Fraser's view of the Victorian era as an unparalleled canvas for military and imperial history, unburdened by modern ideological overlays.[5]Character Analysis

Core Traits: Cowardice, Lechery, and Self-Preservation

Flashman's cowardice is central to his character, as he candidly admits in the purported memoirs to being a poltroon who instinctively flees combat and danger, prioritizing personal safety over duty or honor. Throughout the series, this trait propels him into retreats during key historical events, such as the Afghan retreat from Kabul in 1842, where his attempts to desert lead to capture and subsequent misattributed heroism; yet, adverse luck and circumstance repeatedly position him as a reluctant participant in valorous outcomes. George MacDonald Fraser portrays this not as intermittent fear but as a consistent disposition, with Flashman scorning martial ideals and viewing bravery as folly for lesser men.[19][20] Complementing his timidity is an unabashed lechery, characterized by compulsive sexual pursuits that span prostitutes, aristocrats, and captives across continents, often involving seduction, coercion, or outright force without remorse. Flashman details these encounters with relish, attributing them to an overwhelming carnal drive that overrides propriety or consequence, as seen in his dalliances during the slave trade episodes of Flash for Freedom! (1971), where he engages with figures like a Dahomey slave under duress. Fraser uses these exploits to underscore Flashman's hedonism, framing them as emblematic of Victorian undercurrents rather than isolated vices, though they frequently intersect with his survival strategies.[21][22] Overarching these is Flashman's acute instinct for self-preservation, which Fraser depicts as his sole reliable virtue, manifesting in calculated toadying, fabrication, and opportunism to evade death or disgrace. This compels him to betray allies, fabricate alibis, and exploit chaos for advancement, as in his navigation of imperial intrigues where personal peril prompts immediate shifts in allegiance; for instance, lust yields to caution when risks mount, ensuring longevity amid treachery. Such pragmatism, while enabling survival through twelve volumes spanning 1839 to 1894, renders him amoral, with Fraser attributing this realism to plausible Victorian archetypes rather than caricature.[15][23][20]Moral Ambiguity and Historical Realism

Flashman's moral ambiguity arises from his unrepentant embrace of vices such as cowardice, deceit, lechery, and bullying, which propel him through historical crises without any redemptive arc or internal conflict. As a self-confessed cad, he rationalizes atrocities—including rape and betrayal—as survival imperatives, admitting in his purported memoirs to acts that would scandalize Victorian ideals of heroism, yet he garners acclaim through misattributed bravery and sheer luck. This portrayal subverts the chivalric tropes of era literature, presenting a protagonist whose "one virtue" is candid self-awareness of his monstrosity, fostering reader detachment while underscoring human capacity for moral flexibility under duress.[24] Fraser drew from the bully archetype in Thomas Hughes's Tom Brown's School Days (1857) to embody the flawed undercurrents of imperial agents, arguing that such figures mirrored the era's unpolished humanity rather than sanitized myths. Flashman's racism and self-interest, for instance, align with contemporaries' attitudes, as Fraser noted: "of course he is [racist]; why should he be different from the rest of humanity?" This ambiguity critiques imperial morality not through didactic judgment but by depicting self-serving actors thriving amid systemic hypocrisies, such as British officers' callous leadership in retreats like Kabul (1842), where incompetence claimed thousands of lives.[25][26] The series achieves historical realism through Fraser's exhaustive research into verifiable events—from the First Anglo-Afghan War to the Charge of the Light Brigade (1854)—integrating real figures like Lord Cardigan and embedding Flashman as an eyewitness to their unromanticized follies. Events unfold with precise details, such as the "superhuman stupidity" of British strategy in Afghanistan, exposing the empire's brutal mechanics without narrative glorification. Flashman's "shameless honesty as a memorialist" serves as a lens for causal candor, revealing how personal turpitude often intersected with geopolitical outcomes driven by chance and institutional failings rather than virtue.[25][26][24]Physical Appearance and Evolution Over Time

Harry Flashman is consistently described as a large, imposing man measuring six feet two inches in height and weighing close to thirteen stone, with a powerful, muscular physique that enhances his outward image as a dashing Victorian officer. His features include dark hair and eyes, complemented by a swarthy complexion sufficiently versatile for disguises in diverse settings, from Afghan frontiers to European courts. This handsome, bluff appearance—marked by a hearty demeanor—frequently deceives others into perceiving him as brave and capable, masking his innate cowardice.[27] Throughout the series, Flashman's physical form bears the cumulative marks of his involuntary exploits, including saber scars on his cheeks from German dueling episodes and various gunshot and blade wounds across his body, such as a bullet scar on his posterior. He develops a signature stiff, military mustache—waxed to precision and emblematic of his cavalry service—which he regards with particular vanity as an attractor of female attention, often dubbing them his "tart catchers." These adornments and injuries evolve as badges of his fabricated heroism, with the mustache becoming prominent in his mature years.[28] As the narrative spans Flashman's life from adolescence in the 1830s to advanced age nearing 1915, his appearance reflects the passage of time: hair grays, vigor wanes, and resilience to physical trauma declines, evidenced by a "glass jaw" in later confrontations and reduced capacity for the strenuous escapades of his youth. In volumes like Flashman and the Tiger, the elderly general contends with diminished stamina, cataloging a lifetime of ailments while maintaining an aura of weathered authority through his scarred, mustachioed visage.[29][30]Fictional Biography

Early Life and Rugby School Bullying

Harry Paget Flashman was born in 1822 to Henry Buckley Flashman, a member of Parliament, and Lady Alicia Paget, into a family of considerable wealth and social standing in Leicestershire.[31] His upbringing was privileged, fostering early indulgences in sports such as boxing and horsemanship, alongside a developing reputation for roguish behavior influenced by his father's lax oversight.[10] Flashman entered Rugby School during the headmastership of Thomas Arnold, where the institution's hierarchical structure amplified the power of senior boys like himself in the sixth form.[5] As a product of this environment, he embodied the era's public school ethos of fagging and dominance, quickly rising to prominence through physical prowess and intimidation rather than academic merit. His tenure at Rugby was marked by systematic bullying of younger pupils, including the fictional Tom Brown, whom he persecuted through demands for servitude, physical assaults, and coercion into vices like drinking and smoking.[8] Flashman later reflected on these acts in his purported memoirs as pragmatic self-assertion in a brutal setting, unrepentant about employing tactics such as whipping fags or forcing them to procure alcohol and tobacco.[20] Such conduct aligned with documented accounts of mid-19th-century English boarding schools, where unrestrained senior privileges often led to unchecked abuses until intervention by authorities like Arnold. Flashman's school career culminated in expulsion around 1839 for public drunkenness, an incident involving rowdy behavior on campus that exhausted the patience of school officials and relieved his victims.[10] This event, drawn from Thomas Hughes' depiction but expanded in George MacDonald Fraser's narratives, propelled him toward military enlistment amid the First Anglo-Afghan War, marking the end of his formal education.[32]Military Enlistment and Afghan Campaign (1839-1842)

Following his expulsion from Rugby School in the mid-1830s, Flashman secured a cornet's commission in the 11th Light Dragoons, a fashionable cavalry regiment stationed in Britain, through his father's influence and purchase, viewing military service as a path to indolence and social advancement rather than duty.[33] A scandal involving the seduction of his father's mistress and a resultant duel prompted his transfer to India in 1839, where he integrated into the British Indian Army's preparations for the First Anglo-Afghan War, an expedition aimed at deposing Dost Mohammad Khan and reinstalling the pro-British Shah Shuja to counter Russian expansionism in Central Asia.[20][34] Flashman maneuvered into the role of aide-de-camp to General William Elphinstone, the elderly and indecisive commander of the Kabul force, leveraging family connections amid the Army of the Indus's advance from the Indus River in late 1838.[20][35] The campaign's initial successes included the storming of Ghazni fortress on July 23, 1839, where British forces breached the walls after a brief siege, and the unopposed entry into Kandahar in September, followed by Kabul's occupation in early October after minimal resistance from Afghan irregulars.[36] Flashman's dispatches portray his contributions as peripheral—focused on personal intrigues, including liaisons with local women—while the occupation devolved into garrison ennui, with British troops numbering around 5,000 in Kabul by 1841, strained by supply shortages and tribal unrest.[20] Tensions escalated in late 1841 when Flashman was sent on a covert mission to secure safe passage through Gilzai tribal territories south of Kabul, only to be betrayed and captured by the vengeful Afghan warlord Gul Shah, a figure nursing grudges against British interlopers.[20] Imprisoned and tortured alongside his companion, the British sergeant Hudson, Flashman endured brutal interrogations and assaults before escaping through a combination of deceit, physical endurance, and opportunistic violence, fleeing toward friendly lines amid the gathering storm of rebellion.[20] The Afghan uprising ignited on November 2, 1841, with mobs overrunning British positions in Kabul; envoy Sir William Macnaghten was captured, bargained with, and barbarically dismembered during failed negotiations with Akbar Khan, son of the ousted Dost Mohammad.[35][34] Flashman, peripherally involved in these parleys, observed the hostage-taking of British women and officers, including Elphinstone himself, who capitulated to Akbar's terms for an escorted withdrawal.[20] The retreat commenced on January 6, 1842, from Kabul toward Jalalabad, 90 miles distant, involving approximately 4,500 British and Indian troops alongside 12,000 civilians, camp followers, and dependents; harried by Ghilzai snipers, deprived of food and shelter in sub-zero passes like Khurd Kabul, the column disintegrated over six days, with nearly all perishing from exposure, ambush, or massacre—only Dr. William Brydon, astride a wounded horse, arrived at Jalalabad on January 13 to confirm the catastrophe.[36] In his papers, Flashman claims evasion of total annihilation through earlier captivity by Akbar Khan's forces, subsequent bartering for survival, and a harrowing trek evading Afridi tribesmen; he staggered into the besieged Piper's Fort near Jalalabad, clutching salvaged regimental colors, which prompted his lionization as a defender of the standard despite his self-admitted flight and self-interest.[20] This fabricated heroism propelled his return to British favor, obscuring his cowardice amid the war's humbling toll of over 16,000 lives lost in the broader campaign.[35]Subsequent Adventures and Global Exploits

Following his narrow escape from the Anglo-Afghan War in early 1842, Flashman returned to England as a celebrated hero, though his acclaim stemmed from exaggerated tales of valor rather than genuine bravery. He soon married Elspeth Morrison, the beautiful but naive daughter of a prosperous Scottish merchant, in a union motivated more by her dowry than affection. Their honeymoon voyage in 1843 aboard a trading ship bound for the East Indies quickly devolved into chaos when pirates seized the vessel, abducting Elspeth while Flashman was press-ganged into service among them. Washed ashore in Madagascar, Flashman infiltrated the court of Queen Ranavalona I, whose reign from 1828 to 1861 was marked by the execution of up to 100,000 subjects through torture and famine to suppress Christianity and foreign influence. Posing as a white slave advisor, he navigated her sadistic whims—including ritual killings and forced labor—before engineering Elspeth's rescue from the pirate stronghold, returning to England by 1845 amid rumors of his exploits that bolstered his undeserved reputation.[37] In 1845–1846, Flashman was dispatched to India for the First Anglo-Sikh War, embroiled in the power struggles of the Sikh Empire under Maharaja Ranjit Singh's successors. As detailed in Flashman and the Mountain of Light, he became entangled in espionage surrounding the Koh-i-Noor diamond, a 105-carat gem seized by British forces after battles at Mudki and Ferozeshah, where Sikh artillery inflicted heavy casualties on British troops—over 2,300 killed or wounded in the latter engagement alone. Flashman's role involved smuggling the jewel and bedding Sikh nobility, all while fleeing combat and betraying allies to preserve his skin, culminating in the annexation of the Punjab by 1849. By 1847, back in Europe, he faced blackmail that thrust him into Royal Flash's intrigue: coerced into impersonating a lookalike Bavarian prince to thwart Otto von Bismarck's schemes during the 1848 revolutions. Flashman dueled, romanced actress Lola Montez, and witnessed uprisings across Germany and Austria, where barricades and riots claimed thousands of lives before Prussian forces restored order, escaping with his life but sowing chaos in diplomatic circles.[38][39] Flashman's transatlantic flight in 1848 to evade scandal led to Flash for Freedom!, where he captained a slave ship across the Atlantic, enduring the Middle Passage's horrors—chained Africans enduring mortality rates up to 20% from disease and abuse—before being captured in New Orleans. Sold into slavery himself, he joined the Underground Railroad, encountering a young Abraham Lincoln, who in 1849 defended him in a Kentucky courtroom amid debates over fugitive slave laws that presaged the Compromise of 1850. Subsequent years saw him in the Crimean War (1854–1855) during Flashman at the Charge, surviving the Charge of the Light Brigade at Balaclava on October 25, 1854, where 673 British cavalrymen suffered 247 casualties due to miscommunication. He later quelled the 1857 Indian Rebellion in Flashman in the Great Game, navigating sepoy mutinies that killed over 6,000 Britons, including the Cawnpore massacre. Global wanderings continued into the 1860 Taiping Rebellion in Flashman and the Dragon, China's civil war that claimed 20–30 million lives, where Flashman advised British forces at the sack of Nanking in 1864, and further exploits in America during the Sioux Wars and Little Bighorn in 1876. These episodes, spanning continents from Asia to the Americas, underscored Flashman's pattern of stumbling into history's pivotal conflicts through cowardice and opportunism, always emerging with honors he neither sought nor deserved.[38][40]Relationships and Interactions

Family and Domestic Life

Flashman's family origins trace to a prosperous background in Yorkshire, though specific details of his parents' lives remain sparsely documented in the papers. His marriage to Elspeth Rennie Morrison, daughter of a wealthy Scottish textile manufacturer with political connections, occurred under duress following Flashman's seduction of the then-teenage Elspeth, resulting in a shotgun wedding arranged by her father to preserve social propriety.[41][20] The couple's domestic arrangement relied heavily on Elspeth's inheritance, enabling a comfortable existence in a fashionable London residence supplemented by a country estate in Leicestershire.[41] Flashman and Elspeth had at least two children—a son who pursued a clerical career and a daughter—though Flashman's extended absences for military duties left much of the household management to Elspeth, characterized in the papers as beautiful, affectionate, yet impulsive and occasionally inattentive.[41] Recurring themes in Flashman's accounts highlight the strains of their union, marked by mutual infidelities amid his lechery and her flirtatious tendencies, yet tempered by his professed relief upon returning home after campaigns, which lent a rare note of domestic constancy to his otherwise tumultuous existence.[22] This interplay humanized Flashman amid his self-admitted vices, portraying Elspeth as both anchor and source of complication in his personal life.[22]Romantic Entanglements and Sexual Exploits

Flashman's marriage to Elspeth Morrison in 1839, following his seduction of the 16-year-old daughter of a wealthy Paisley manufacturer, forms the basis of his domestic life amid his peripatetic career. Arranged by her father to avert scandal after Flashman compromised her virtue during a drunken escapade, the union endures despite mutual suspicions of infidelity, with Flashman viewing Elspeth's beauty and occasional lapses as both allure and irritation.[42] [43] He maintains a possessive fondness for her, yet his compulsive lechery ensures chronic unfaithfulness, often rationalized as an irrepressible urge that complicates his self-preservation.[22] Prior to and during his early military service, Flashman's appetites manifest in opportunistic seductions that precipitate personal crises. At home in Leicestershire, he targets Judy Parsons, the mistress of his father, Henry Flashman, leading to humiliation when she rebuffs his advances after initial compliance.[20] In the 11th Light Dragoons, a dalliance with Josette, the French mistress of Captain Henri Bernier—a skilled duelist—sparks a challenge to a duel, from which Flashman schemes to escape through deceit rather than honor.[20] These incidents exemplify his predatory approach toward available women, prioritizing gratification over risk assessment, though luck and cunning typically extricate him. Across subsequent global exploits, Flashman's encounters escalate in diversity and danger, involving courtesans, slaves, and nobility from Europe to Asia, with the papers tallying approximately 480 conquests by the 1880s.[43] In Afghanistan (1839–1842), he rapes Narreeman, a dancing girl and assassin who had earlier attempted his murder, framing the act as vengeful retribution amid wartime brutality.[44] Later volumes depict entanglements like his liaison with the infamous Lola Montez during the 1840s Bavarian intrigue, and inducements via a minister's wife to smuggle opium into China in 1860, where sexual promises serve as bait for perilous missions.[45] [46] Such exploits, blending lust with historical tumult, underscore Fraser's portrayal of Victorian masculinity unvarnished by moral restraint, often entangling Flashman in intrigues where dalliance amplifies jeopardy.[25]Encounters with Historical Figures

Flashman interacts with a diverse array of historical figures across the novels, often portraying them with shrewd, unromanticized assessments drawn from Fraser's extensive historical research, revealing personal flaws and contextual brutalities without modern sanitization. These encounters span military commanders, political leaders, monarchs, and cultural icons, embedding Flashman's fictional cowardice amid real events like retreats, charges, and diplomatic intrigues.[31][47] In his early military career, Flashman serves under James Brudenell, 7th Earl of Cardigan, joining the 11th Hussars and participating in the disastrous First Anglo-Afghan War (1839–1842), where Cardigan's leadership exemplifies aristocratic incompetence amid catastrophic losses exceeding 16,000 British and Indian troops during the Kabul retreat.[31] Later, during the Crimean War in Flashman at the Charge, he witnesses the Charge of the Light Brigade under Cardigan's command on October 25, 1854, surviving the suicidal assault that claimed over 100 British lives due to miscommunication and poor tactics. Flashman also crosses paths with Florence Nightingale at Balmoral Castle, Queen Victoria's Scottish residence, observing her amid the era's medical reforms following the war's high mortality rates from disease.[22][31][47] Politically, Flashman meets Abraham Lincoln in 1848 at a Washington soirée depicted in Flash for Freedom!, describing the future president as witty and cunning but prejudiced, quoting him on Black people as a "troublesome and expensive nuisance" reflective of antebellum attitudes before Lincoln's evolution during the Civil War. He encounters Otto von Bismarck in Royal Flash (1842–1843), navigating the Prussian statesman's early ambitions amid impersonation schemes involving European royalty. Flashman also interacts with John Brown, the abolitionist, in the lead-up to the 1859 Harpers Ferry raid, highlighting Brown's fanaticism in Flashman and the Angel of the Lord. Benjamin Disraeli appears among his political acquaintances, as does Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, underscoring Flashman's opportunistic proximity to British imperial decision-makers.[31][47][48][5] Monarchical and imperial figures feature prominently, with Flashman receiving honors from Queen Victoria, who, along with the public, mistakes his survival for heroism, granting him the Victoria Cross despite his self-preserving flight in multiple crises from the Afghan War onward. He beds Lola Montez, the Irish dancer and mistress to King Ludwig I of Bavaria, during Bavarian intrigues in Royal Flash. In Flashman's Lady, Flashman becomes the reluctant lover of Queen Ranavalona I of Madagascar, whose tyrannical reign (1828–1861) involved mass executions estimated at 20,000–30,000, escaping her court amid ritual killings. Encounters extend to Yehonala (later Empress Dowager Cixi) in Flashman and the Dragon, during the Second Opium War, and James Bruce, 8th Earl of Elgin, who orders the 1860 burning of Beijing's Summer Palace in retaliation for torture and imprisonment of British envoys.[47][31][5][31] Later adventures include meetings with military notables like George Armstrong Custer in pre-Civil War contexts and Charles George Gordon ("Chinese Gordon") during imperial campaigns, as well as cultural figures such as Oscar Wilde and actresses Lillie Langtry and Daisy Greville, mistress to the future Edward VII. Flashman also knows the Duke of Wellington, whose post-Waterloo influence lingers into the 1840s, and Thomas Arnold, Rugby School's headmaster from his schooldays. These portrayals, grounded in primary sources and eyewitness accounts consulted by Fraser, prioritize causal realism over hagiography, exposing hypocrisies in empire-builders and reformers alike.[47][31][48]The Flashman Papers

Publication Chronology and Structure

The Flashman Papers series comprises twelve principal volumes authored by George MacDonald Fraser, spanning publication from 1969 to 2005, with each novel issued irregularly over the decades. The chronology reflects Fraser's intermittent output amid other writing commitments, beginning with the debut volume that introduced the framing device and concluding with a final installment released two years before Fraser's death in 2008.[49][50] The publication sequence is as follows:| Title | Year |

|---|---|

| Flashman | 1969 |

| Royal Flash | 1970 |

| Flash for Freedom! | 1971 |

| Flashman at the Charge | 1973 |

| Flashman in the Great Game | 1975 |

| Flashman's Lady | 1977 |

| Flashman and the Redskins | 1982 |

| Flashman and the Dragon | 1985 |

| Flashman and the Mountain of Light | 1990 |

| Flashman and the Angel of the Lord | 1994 |

| Flashman and the Tiger | 1999 |

| Flashman on the March | 2005 |

Key Novels and Their Historical Settings

The Flashman series comprises twelve principal novels, published between 1969 and 2005, each framed as excerpts from the supposed memoirs of Harry Flashman detailing his coerced participation in landmark British imperial conflicts and expeditions of the Victorian era. These works meticulously incorporate verifiable historical details, such as troop movements, battle outcomes, and key figures, while portraying Flashman's self-serving survival amid chaos.[50][18]| Novel Title | Publication Year | Primary Historical Setting(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Flashman | 1969 | First Anglo-Afghan War (1839–1842), including the retreat from Kabul.[51][3] |

| Royal Flash | 1970 | European upheavals of the 1840s, centered on the Schleswig-Holstein succession crisis and fictional parallels to mid-century princely intrigues.[4] |

| Flash for Freedom! | 1971 | Transatlantic slave trade and pre-Civil War America (1848–1849), encompassing the Atlantic crossing, U.S. plantation economy, and early abolitionist networks.[52][50] |

| Flashman at the Charge | 1973 | Crimean War (1854–1855), featuring the Charge of the Light Brigade at Balaclava and the Siege of Sevastopol.[53][18] |

| Flashman in the Great Game | 1975 | Indian Rebellion of 1857 (Sepoy Mutiny), including the Relief of Lucknow and Cawnpore Massacre.[50] |

| Flashman's Lady | 1977 | Post-Afghan expeditions (1843–1845), involving pirate strongholds in Madagascar and the Brooke Raj in Borneo.[50] |

| Flashman and the Redskins | 1980 | American West migrations (1849–1850 and 1875–1876), spanning the California Gold Rush, Oregon Trail, and Battle of the Little Bighorn.[54] |

| Flashman and the Dragon | 1985 | Taiping Rebellion in China (1860), amid the Arrow War and sack of Nanking.[50] |

| Flashman and the Mountain of Light | 1990 | First Anglo-Sikh War (1845–1846), including battles at Mudki, Ferozeshah, and Sobraon over the Koh-i-Noor diamond.[50] |

| Flashman and the Angel of the Lord | 1994 | Antebellum U.S. tensions (1858–1859), focused on John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry.[50] |

| Flashman and the Tiger | 1999 | Late-century episodes, including the Anglo-Zulu War at Isandlwana (1879) and other scattered Victorian campaigns.[50] |

| Flashman on the March | 2005 | British Expedition to Abyssinia (1867–1868), culminating in the capture of Emperor Tewodros II at Magdala.[55][50] |