Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Indian Rebellion of 1857

View on Wikipedia

| Indian Rebellion of 1857 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

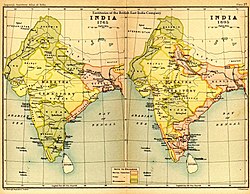

A 1912 map of Northern India, showing the centres of the rebellion. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

The Earl Canning George Anson † Sir Patrick Grant Sir Colin Campbell Sir Hugh Rose Sir Henry Havelock † Sir James Outram Sir Henry Lawrence (DOW) James Neill † John Nicholson † Surendra Bikram Shah Dhir Shamsher Rana[1] Randhir Singh Sir Yusef Ali Khan | |||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

6,000 British killed, including civilians[a][2] Based on a rough comparison of the sketchy pre-1857 regional demographic data and the first 1871 Census of India, probably 800,000 Indians were killed, and very likely more, both in the rebellion and in the famines and epidemics of disease that were caused as a result in its immediate aftermath.[2] | |||||||||

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a major uprising in India in 1857–58 against the rule of the British East India Company, which functioned as a sovereign power on behalf of the British Crown.[5][6] The rebellion began on 10 May 1857 in the form of a mutiny of sepoys of the company's army in the garrison town of Meerut, 40 miles (64 km) northeast of Delhi. It then erupted into other mutinies and civilian rebellions chiefly in the upper Gangetic plain and central India,[b][7][c][8] though incidents of revolt also occurred farther north and east.[d][9] The rebellion posed a military threat to British power in that region,[e][10] and was contained only with the rebels' defeat in Gwalior on 20 June 1858.[11] On 1 November 1858, the British granted amnesty to all rebels not involved in murder, though they did not declare the hostilities to have formally ended until 8 July 1859.

The name of the revolt is contested, and it is variously described as the Sepoy Mutiny, the Indian Mutiny, the Great Rebellion, the Revolt of 1857, the Indian Insurrection, and the First War of Independence.[f][12]

The Indian rebellion was fed by resentments born of diverse perceptions, including invasive British-style social reforms, harsh land taxes, summary treatment of some rich landowners and princes,[13][14] and scepticism about British claims that their rule offered material improvement to the Indian economy.[g][15] Many Indians rose against the British; however, many also fought for the British, and the majority remained seemingly compliant to British rule.[h][15] Violence, which sometimes betrayed exceptional cruelty, was inflicted on both sides: on British officers and civilians, including women and children, by the rebels, and on the rebels and their supporters, including sometimes entire villages, by British reprisals; the cities of Delhi and Lucknow were laid waste in the fighting and the British retaliation.[i][15]

After the outbreak of the mutiny in Meerut, the rebels quickly reached Delhi, whose 81-year-old Mughal ruler, Bahadur Shah Zafar, was declared the Emperor of Hindustan. Soon, the rebels had captured large tracts of the North-Western Provinces and Awadh (Oudh). The East India Company's response came rapidly as well. With help from reinforcements, Kanpur was retaken by mid-July 1857, and Delhi by the end of September.[11] However, it then took the remainder of 1857 and the better part of 1858 for the rebellion to be suppressed in Jhansi, Lucknow, and especially the Awadh countryside.[11] Other regions of Company-controlled India—Bengal province, the Bombay Presidency, and the Madras Presidency, remained largely calm.[j][8][11] In the Punjab, the Sikh princes crucially helped the British by providing both soldiers and support.[k][8][11] The large princely states, Hyderabad, Mysore, Travancore, and Kashmir, as well as the smaller ones of Rajputana, did not join the rebellion, serving the British, in the Governor-General Lord Canning's words, as "breakwaters in a storm".[16]

In some regions, most notably in Awadh, the rebellion took on the attributes of a patriotic revolt against British oppression.[17] However, the rebel leaders proclaimed no articles of faith that presaged a new political system.[l][18] Even so, the rebellion proved to be an important watershed in Indian and British Empire history.[m][12][19] It led to the dissolution of the East India Company, and forced the British to reorganize the army, the financial system, and the administration in India, through passage of the Government of India Act 1858.[20] India was thereafter administered directly by the British government in the new British Raj.[16] On 1 November 1858, Queen Victoria issued a proclamation to Indians, which while lacking the authority of a constitutional provision,[n][21] promised rights similar to those of other British subjects.[o][p][22] In the following decades, when admission to these rights was not always forthcoming, Indians were to pointedly refer to the Queen's proclamation in growing avowals of a new nationalism.[q][r][24]

East India Company's expansion in India

[edit]

Although the British East India Company had established a presence in India as far back as 1612,[25] and earlier administered the factory areas established for trading purposes, its victory in the Battle of Plassey in 1757 marked the beginning of its firm foothold in eastern India. The victory was consolidated in 1764 at the Battle of Buxar, when the East India Company army defeated Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II. After his defeat, the emperor granted the company the right to the "collection of Revenue" in the provinces of Bengal (modern day Bengal, Bihar, and Odisha), known as "Diwani" to the company.[26] The Company soon expanded its territories around its bases in Bombay and Madras; later, the Anglo-Mysore Wars (1766–1799) and the Anglo-Maratha Wars (1772–1818) led to control of even more of India.[27]

In 1806, the Vellore Mutiny was sparked by new uniform regulations that created resentment amongst both Hindu and Muslim sepoys.[28]

After the turn of the 19th century, Governor-General Wellesley began what became two decades of accelerated expansion of Company territories. This was achieved either by subsidiary alliances between the company and local rulers or by direct military annexation.[29] The subsidiary alliances created the princely states of the Hindu maharajas and the Muslim nawabs. Punjab, North-West Frontier Province, and Kashmir were annexed after the Second Anglo-Sikh War in 1849; however, Kashmir was immediately sold under the 1846 Treaty of Amritsar to the Dogra Dynasty of Jammu and thereby became a princely state. The border dispute between Nepal and British India, which sharpened after 1801, had caused the Anglo-Nepalese War of 1814–16 and brought the defeated Gurkhas under British influence. In 1854, Berar was annexed, and the state of Oudh was added two years later. For practical purposes, the company was the government of much of India.[citation needed]

Causes of the rebellion

[edit]The Indian Rebellion of 1857 occurred as the result of an accumulation of factors over time, rather than any single event.[citation needed]

The sepoys were Indian soldiers who were recruited into the company's army. Just before the rebellion, there were over 300,000 sepoys in the army, compared to about 50,000 British. The East India Company's forces were divided into three presidency armies: Bombay, Madras, and Bengal. The Bengal Army recruited higher castes, such as Brahmins, Rajputs and Bhumihar, mostly from the Awadh and Bihar regions, and even restricted the enlistment of lower castes in 1855.[30] In contrast, the Madras Army and Bombay Army were "more localized, caste-neutral armies" that "did not prefer high-caste men".[31] The domination of higher castes in the Bengal Army has been blamed in part for initial mutinies that led to the rebellion.[citation needed]

| Rebellions in British India |

|---|

| East India Company |

|

| British Raj |

|

In 1772, when Warren Hastings was appointed Fort William's first Governor-General, one of his first undertakings was the rapid expansion of the company's army. Since the sepoys from Bengal – many of whom had fought against the Company in the Battles of Plassey and Buxar – were now suspect in British eyes, Hastings recruited farther west from the high-caste rural Rajputs and Bhumihar of Awadh and Bihar, a practice that continued for the next 75 years. However, in order to forestall any social friction, the company also took action to adapt its military practices to the requirements of their religious rituals. Consequently, these soldiers dined in separate facilities; in addition, overseas service, considered polluting to their caste, was not required of them, and the army soon came officially to recognise Hindu festivals. "This encouragement of high caste ritual status, however, left the government vulnerable to protest, even mutiny, whenever the sepoys detected infringement of their prerogatives."[32] Stokes argues that "The British scrupulously avoided interference with the social structure of the village community which remained largely intact."[33]

After the annexation of Oudh (Awadh) by the East India Company in 1856, many sepoys were disquieted both from losing their perquisites, as landed gentry, in the Oudh courts, and from the anticipation of any increased land-revenue payments that the annexation might bring about.[34] Other historians have stressed that by 1857, some Indian soldiers, interpreting the presence of missionaries as a sign of official intent, were convinced that the company was masterminding mass conversions of Hindus and Muslims to Christianity.[35] Although earlier in the 1830s, evangelicals such as William Carey and William Wilberforce had successfully clamoured for the passage of social reform, such as the abolition of sati and allowing the remarriage of Hindu widows, there is little evidence that the sepoys' allegiance was affected by this.[34]

However, changes in the terms of their professional service may have created resentment. As the extent of the East India Company's jurisdiction expanded with victories in wars or annexation, the soldiers were now expected not only to serve in less familiar regions, such as in Burma, but also to make do without the "foreign service" remuneration that had previously been their due.[36]

A major cause of resentment that arose ten months prior to the outbreak of the rebellion was the General Service Enlistment Act of 25 July 1856. As noted above, men of the Bengal Army had been exempted from overseas service. Specifically, they were enlisted only for service in territories to which they could march. Governor-General Lord Dalhousie saw this as an anomaly, since all sepoys of the Madras and Bombay Armies and the six "General Service" battalions of the Bengal Army had accepted an obligation to serve overseas if required. As a result, the burden of providing contingents for active service in Burma, readily accessible only by sea, and China had fallen disproportionately on the two smaller Presidency Armies. As signed into effect by Lord Canning, Dalhousie's successor as Governor-General, the act required only new recruits to the Bengal Army to accept a commitment for general service. However, serving high-caste sepoys were fearful that it would be eventually extended to them, as well as preventing sons following fathers into an army with a strong tradition of family service.[37]: 261

There were also grievances over the issue of promotions, based on seniority. This, as well as the increasing number of British officers in the battalions,[38][better source needed] made promotion slow, and many Indian officers did not reach commissioned rank until they were too old to be effective.[39]

The Enfield rifle

[edit]

The immediate flashpoint for the 1857 uprising is often associated with the introduction of the Pattern 1853 Enfield rifle-musket into the Bengal Army. These rifles used paper cartridges that were pre-greased to allow smooth loading. To load the rifle, a soldier tore open the cartridge, traditionally with his teeth, before pouring the powder down the barrel and ramming home the bullet and wadding.[40]

In early 1857, rumours began circulating among sepoys that the grease used on these cartridges was derived from cow tallow, offensive to Hindus, and pig lard, offensive to Muslims. These rumours caused deep alarm because biting the cartridge could be perceived as a violation of religious practice.[41]

Modern historians emphasize that it was the belief in these rumours, rather than the confirmed presence of animal fat, that inflamed tensions. Kim Wagner argues that there is little direct evidence that large numbers of greased cartridges were actually issued to Indian troops before the revolt.[42] Instead, the affair reflects a broader climate of distrust in which fears of religious pollution merged with anxieties about British intentions toward Indian society and religion.[43]

British officials became aware of the rumours through reports of disputes between sepoys and labourers at military depots such as Dum Dum and Barrackpore.[44] In response, the Company ordered that future cartridges be supplied without grease and allowed sepoys to apply their own lubricant.[45] However, this measure failed to calm fears and, in some cases, reinforced the suspicion that the authorities were concealing the truth.[42]

The "greased cartridge affair" thus became a powerful symbol of British cultural insensitivity and fed into broader grievances over pay, conditions of service, and the perception that the Company was seeking to erode traditional religious and social structures. Historians now view the controversy less as a single cause and more as a catalyst that helped turn widespread discontent into open rebellion.[46]

Civilian disquiet

[edit]Civilian participation in the rebellion was diverse and regionally varied, involving three main groups: the traditional feudal nobility, rural landlords known as taluqdars, and the peasantry.[47]

The feudal nobility included princes and chieftains whose power had been curtailed by British expansionist policies such as the Doctrine of Lapse, which denied recognition to adopted heirs of deceased rulers. Many nobles, such as Nana Sahib and Rani of Jhansi, had initially been willing to accept British supremacy but rebelled when their legal and hereditary claims were rejected. For instance, the Rani of Jhansi resisted British authority after her adopted son was denied recognition as her late husband's successor.[48][49] In regions like Indore and Sagar, where princely privileges were not directly threatened, many rulers remained loyal to the British even when local sepoys revolted.[50]

The taluqdars, particularly in Oudh and Bihar, played a decisive role in the uprising. British land-revenue policies and annexations had stripped many taluqdars of their traditional estates, transferring large portions of land to peasant farmers.[51] During the rebellion, Rajput taluqdars provided much of the leadership in Oudh, while in Bihar, figures like Kunwar Singh emerged as prominent leaders.[47] As the rebellion spread, taluqdars reasserted control over their lost territories, often with the support of peasants bound to them by kinship and feudal loyalty. British officials were surprised at the lack of resistance from these peasant groups, many of whom actively joined the revolt.[51]

Heavy land-revenue assessments imposed by the Company also contributed to widespread rural discontent. Many landowners were forced into debt or bankruptcy, creating deep resentment toward both the British and moneylenders who profited from these policies.[52][53] Moneylenders became symbolic targets of popular anger, alongside Company officials.[54]

Despite the widespread participation of civilians, the rebellion was geographically uneven. Even within rebellious regions of north-central India, some districts remained calm. For example, the prosperous Muzaffarnagar district, which benefited from a Company-sponsored irrigation project, stayed largely loyal to British authority despite its proximity to Meerut, where the uprising began.[55]

-

Charles Canning, 1st Earl Canning, the Governor-General of India during the rebellion.

-

Lord Dalhousie, Governor-General of India (1848–1856), who devised the Doctrine of Lapse.

-

Lakshmibai, Rani of Jhansi, one of the principal rebel leaders who lost her kingdom through the Doctrine of Lapse.

-

Bahadur Shah Zafar, the last Mughal emperor, declared symbolic leader of the rebellion, later exiled to Burma.

Reformist policies introduced by the Company were also viewed with suspicion by many Indians. Utilitarian and evangelical-inspired reforms, such as the abolition of sati[56] and the legalisation of widow remarriage, were interpreted by some as attempts to undermine traditional Indian religions and promote Christian conversion.[57][58] Historian Christopher Bayly has described the uprising as, in part, a "clash of knowledges," in which traditional religious and social authorities, including pandits, maulvis, and astrologers, perceived British colonial educational and medical policies as a direct threat to established hierarchies.[59] Testimonies collected after the rebellion, such as those recorded in the 1858 Parliamentary Blue Books, reveal that British-run schools were especially controversial.[60] Many parents feared that the exclusion of religious instruction and the introduction of secular subjects like mathematics and Western science, as well as the education of girls, undermined traditional moral and spiritual values.[61]

The colonial justice system was also widely perceived as biased. Official reports, such as the East India (Torture) 1855–1857 Blue Books laid before the House of Commons, documented that Company officers accused of brutality against Indians were often shielded by extended appeals processes and rarely faced meaningful punishment.[62]

Finally, the economic policies of the East India Company, including high taxation and export-oriented trade practices, were deeply resented by many communities. These policies disrupted traditional industries and contributed to widespread hardship, further fueling rebellion.[63]

The Bengal Army

[edit]

Each of the three "Presidencies" into which the East India Company divided India for administrative purposes maintained its own army. Of these, the Army of the Bengal Presidency was the largest. Unlike the other two presidency armies, it recruited heavily from among high-status Hindus and comparatively wealthy Muslims. Muslims formed a larger percentage of the 18 irregular cavalry units,[64] while Hindus were mainly found in the 84 regular infantry and cavalry regiments. About 75% of the cavalry was composed of Indian Muslims, while roughly 80% of the infantry consisted of Hindus.[65]

During the early years of Company rule, authorities tolerated and even encouraged the social and religious practices of their recruits. The Bengal Army’s regular infantry was drawn almost exclusively from the landowning Rajput and Brahmin communities of Bihar and Oudh, collectively known as Purbiyas. From the 1840s onward, administrative reforms introduced in Calcutta began to erode many of these long-standing privileges. Having grown accustomed to high social and ritual standing, the sepoys became increasingly sensitive to policies or actions they perceived as threatening their religious purity or social status.[66][30]

The sepoys also grew dissatisfied with other aspects of army life. Pay was relatively low, and following the annexations of Oudh and the Punjab, soldiers no longer received extra allowances (batta or bhatta) for service there, as these regions were no longer classified as "foreign missions". Relations between British junior officers and sepoys deteriorated as many officers increasingly treated their men as racial inferiors. In 1856, the Company introduced a new Enlistment Act making all units in the Bengal Army theoretically liable for overseas service. Although intended only for new recruits, many serving sepoys feared it might be applied retroactively. Hindu soldiers in particular were alarmed, as sea voyages under cramped shipboard conditions made it impossible to follow essential religious practices, raising fears of ritual defilement and social ostracism.[37]: 243 [67]

Onset of the rebellion

[edit]

Several months of increasing tensions coupled with various incidents preceded the actual rebellion. On 26 February 1857 the 19th Bengal Native Infantry (BNI) regiment became concerned that new cartridges they had been issued were wrapped in paper greased with cow and pig fat, which had to be opened by mouth thus affecting their religious sensibilities. Their Colonel confronted them supported by artillery and cavalry on the parade ground, but after some negotiation withdrew the artillery, and cancelled the next morning's parade.[68]

Mangal Pandey

[edit]On 29 March 1857 at the Barrackpore parade ground, near Calcutta, 29-year-old Mangal Pandey of the 34th BNI, angered by the recent actions of the East India Company, declared that he would rebel against his commanders. Informed about Pandey's behaviour Sergeant-Major James Hewson went to investigate, only to have Pandey shoot at him. Hewson raised the alarm.[69] When his Adjutant Lt. Henry Baugh came out to investigate the unrest, Pandey opened fire but hit Baugh's horse instead.[70]

General John Hearsey came out to the parade ground to investigate, and claimed later that Mangal Pandey was in some kind of "religious frenzy". He ordered the Indian commander of the Quarter Guard Jemadar Ishwari Prasad to arrest Mangal Pandey, but the Jemadar refused. The quarter guard and other sepoys present, with the single exception of a soldier called Shaikh Paltu, drew back from restraining or arresting Mangal Pandey. Shaikh Paltu restrained Pandey from continuing his attack.[70][71]

After failing to incite his comrades into an open and active rebellion, Mangal Pandey tried to take his own life, by placing his musket to his chest and pulling the trigger with his toe. He managed only to wound himself. He was court-martialled on 6 April and hanged two days later.[citation needed]

The Jemadar Ishwari Prasad was sentenced to death and hanged on 21 April. The regiment was disbanded and stripped of its uniforms because it was felt that it harboured ill-feelings towards its superiors, particularly after this incident. Shaikh Paltu was promoted to the rank of havildar in the Bengal Army but was murdered shortly before the 34th BNI dispersed.[72]

Sepoys in other regiments thought these punishments were harsh. The demonstration of disgrace during the formal disbanding helped foment the rebellion in view of some historians. Disgruntled ex-sepoys returned home to Awadh with a desire for revenge.[citation needed]

Unrest during April 1857

[edit]During April, there were unrest and fires at Agra, Allahabad and Ambala. At Ambala in particular, which was a large military cantonment where several units had been collected for their annual musketry practice, it was clear to General Anson, Commander-in-Chief of the Bengal Army, that some sort of rebellion over the cartridges was imminent. Despite the objections of the civilian Governor-General's staff, he agreed to postpone the musketry practice and allow a new drill by which the soldiers tore the cartridges with their fingers rather than their teeth. However, he issued no general orders making this standard practice throughout the Bengal Army and, rather than remain at Ambala to defuse or overawe potential trouble, he then proceeded to Simla, the cool hill station where many high officials spent the summer.[citation needed]

Although there was no open revolt at Ambala, there was widespread arson during late April. Barrack buildings (especially those belonging to soldiers who had used the Enfield cartridges) and British officers' bungalows were set on fire.[73]

Meerut

[edit]

At Meerut, a large military cantonment, 2,357 Indian sepoys and 2,038 British soldiers were stationed along with 12 British-manned guns. The station held one of the largest concentrations of British troops in India and this was later cited[by whom?] as evidence that the original rising was a spontaneous outbreak rather than a pre-planned plot.[37]: 278

Although the state of unrest within the Bengal Army was well known, on 24 April Lieutenant Colonel George Carmichael-Smyth, the unsympathetic commanding officer of the 3rd Bengal Light Cavalry, which was composed mainly of Indian Muslims,[74] ordered 90 of his men to parade and perform firing drills. All except five of the men on parade refused to accept their cartridges. On 9 May, the remaining 85 men were court martialled, and most were sentenced to 10 years' imprisonment with hard labour. Eleven comparatively young soldiers were given five years' imprisonment. The entire garrison was paraded and watched as the condemned men were stripped of their uniforms and placed in shackles. As they were marched off to jail, the condemned soldiers berated their comrades for failing to support them.[citation needed]

The next day was Sunday. Some Indian soldiers warned off-duty junior British officers that plans were afoot to release the imprisoned soldiers by force, but the senior officers to whom this was reported took no action. There was also unrest in the city of Meerut itself, with angry protests in the bazaar and some buildings being set on fire. In the evening, most British officers were preparing to attend church, while many of the British soldiers were off duty and had gone into canteens or into the bazaar in Meerut. The Indian troops, led by the 3rd Cavalry, broke into revolt. British junior officers who attempted to quell the first outbreaks were killed by the rebels. British officers' and civilians' quarters were attacked, and four civilian men, eight women and eight children were killed. Crowds in the bazaar attacked off-duty soldiers there. About 50 Indian civilians, some of them officers' servants who tried to defend or conceal their employers, were killed by the sepoys.[75] While the action of the sepoys in freeing their 85 imprisoned comrades appears to have been spontaneous, some civilian rioting in the city was reportedly encouraged by Kotwal (chief police officer) Dhan Singh Gurjar.[76]

Some sepoys (especially from the 11th Bengal Native Infantry) escorted trusted British officers and women and children to safety before joining the revolt.[77] Some officers and their families escaped to Rampur, where they found refuge with the Nawab.[citation needed]

The British historian Philip Mason notes that it was inevitable that most of the sepoys and sowars from Meerut should have made for Delhi on the night of 10 May. It was a strong walled city located only forty miles away, it was the ancient capital and present seat of the nominal Mughal Emperor, and there were no British troops in garrison there, in contrast to Meerut.[37]: 278 No effort was made to pursue them.[citation needed]

Delhi

[edit]

Early on 11 May, the first parties of the 3rd Cavalry reached Delhi. From beneath the windows of Emperor Bahadur Shah II's apartments in the palace, they called on the Emperor to acknowledge and lead them. He did nothing at this point, apparently treating the sepoys as ordinary petitioners, but others in the palace were quick to join the revolt. During the day, the revolt spread. British officials and dependents, Indian Christians and shop keepers within the city were killed, some by sepoys and others by crowds of rioters.[78]: 71–73

There were three battalion-sized regiments of Bengal Native Infantry stationed in or near the city. Some detachments quickly joined the rebellion, while others held back but also refused to obey orders to take action against the rebels. In the afternoon, a violent explosion in the city was heard for several miles. Fearing that the arsenal, which contained large stocks of arms and ammunition, would fall intact into rebel hands, the nine British Ordnance officers there had opened fire on the sepoys, including the men of their own guard. When resistance appeared hopeless, they blew up the arsenal. Six of the nine officers survived, but the blast killed many in the streets and nearby houses and other buildings.[79] The news of these events finally tipped the sepoys stationed around Delhi into open rebellion. The sepoys were later able to salvage at least some arms from the arsenal. A magazine 3 km (1.9 mi) outside Delhi, containing up to 3,000 barrels of gunpowder, was captured without resistance.[citation needed]

Many fugitive British officers and civilians had congregated at the Flagstaff Tower on the ridge north of Delhi, where telegraph operators were sending news of the events to other British stations. When it became clear that the help expected from Meerut was not coming, they made their way in carriages to Karnal. Those who became separated from the main body or who could not reach the Flagstaff Tower also set out for Karnal on foot. Some were helped by villagers on the way; others were killed.[citation needed]

The next day, Bahadur Shah held his first formal court in years.[when?] It was attended by many[quantify] excited sepoys. The emperor was alarmed by the turn events had taken, but eventually accepted the sepoys' allegiance and agreed to give his countenance to the rebellion. On 16 May, up to 50 British who had been held prisoner in the palace or had been discovered hiding in the city were killed by some of the emperor's servants in a courtyard outside the palace.[80][81]

Supporters and opposition

[edit]

The news of the events at Meerut and Delhi spread rapidly, provoking uprisings among sepoys and disturbances in many districts. In many cases, it was the behaviour of British military and civilian authorities themselves which precipitated disorder. Learning of the fall of Delhi, many Company administrators hastened to remove themselves, their families and servants to places of safety. At Agra, 160 miles (260 km) from Delhi, no fewer than 6,000 assorted non-combatants converged on the Fort.[82]

The military authorities also reacted in disjointed manner. Some officers trusted their sepoys, but others tried to disarm them to forestall potential uprisings. At Benares and Allahabad, the disarmings were bungled, also leading to local revolts.[83]: 52–53

In 1857, the Bengal Army had 86,000 men, of which 12,000 were British, 16,000 Sikh and 1,500 Gurkha. There were 311,000 native soldiers in India altogether, 40,160 British soldiers (including units of the British Army) and 5,362 officers.[84] Fifty-four of the Bengal Army's 74 regular Native Infantry Regiments mutinied, but some were immediately destroyed or broke up, with their sepoys drifting away to their homes. A number of the remaining 20 regiments were disarmed or disbanded to prevent or forestall mutiny. Only twelve of the original Bengal Native Infantry regiments survived to pass into the new Indian Army.[85] All ten of the Bengal Light Cavalry regiments mutinied.[citation needed]

The Bengal Army also contained 29 irregular cavalry and 42 irregular infantry regiments. Of these, a substantial contingent from the recently annexed state of Awadh mutinied en masse. Another large contingent from Gwalior also mutinied, even though that state's king (Jayajirao Scindia) supported the British. The remainder of the irregular units were raised from a wide variety of sources and were less affected by the concerns of mainstream Indian society. Some irregular units actively supported the company: three Gurkha and five of six Sikh infantry units, and the six infantry and six cavalry units of the recently raised Punjab Irregular Force.[86][87]

On 1 April 1858, the number of Indian soldiers in the Bengal army loyal to the company was 80,053.[88][89] However large numbers were hastily raised in the Punjab and North-West Frontier after the outbreak of the Rebellion.[citation needed]

The Bombay army had three mutinies in its 29 regiments, whilst the Madras Army had none at all, although elements of one of its 52 regiments refused to volunteer for service in Bengal.[90] Nonetheless, most of southern India remained passive, with only intermittent outbreaks of violence. Many parts of the region were ruled by the Nizams or the Mysore royalty, and were thus not directly under British rule.[citation needed]

Although most of the mutinous sepoys in Delhi were Hindus, a significant proportion of the insurgents were Muslims. The proportion of ghazis grew to be about a quarter of the local fighting force by the end of the siege and included a regiment of suicide ghazis from Gwalior who had vowed never to eat again and to fight until they met certain death at the hands of British troops.[91] However, most Muslims did not share the rebels' dislike of the British administration[92] and their ulema could not agree on whether to declare a jihad.[93] Some Islamic scholars such as Maulana Muhammad Qasim Nanautavi and Maulana Rashid Ahmad Gangohi took up arms against the colonial rule,[94] but many Muslims, among them ulema from both the Sunni and Shia sects, sided with the British.[95] Various Ahl-i-Hadith scholars and colleagues of Nanautavi rejected the jihad.[96] The most influential member of Ahl-i-Hadith ulema in Delhi, Maulana Sayyid Nazir Husain Dehlvi, resisted pressure from the mutineers to call for a jihad and instead declared in favour of British rule, viewing the Muslim-British relationship as a legal contract which could not be broken unless their religious rights were breached.[97]

The Sikhs and Pathans of the Punjab and North-West Frontier Province supported the British and helped in the recapture of Delhi.[98] The Sikhs in particular feared reinstatement of Mughal rule in northern India[99] because they had been persecuted by the Mughal Empire. They also felt disdain towards the Purbiyas or 'Easterners' (Biharis and those from the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh) in the Bengal Army. The Sikhs felt that the bloodiest battles of the First and Second Anglo-Sikh wars (Chillianwala and Ferozeshah), had been won by British troops, while the Hindustani sepoys had refused to meet the Sikhs in battle.[100] These feelings were compounded when Hindustani sepoys were assigned a very visible role as garrison troops in Punjab and awarded profit-making civil posts in the Punjab.[99]

The varied groups in the support and opposing of the uprising is seen as a major cause of its failure.[citation needed]

The revolt

[edit]Initial stages

[edit]

Bahadur Shah II was proclaimed the Emperor of the whole of India. Most contemporary and modern accounts suggest that he was coerced by the sepoys and his courtiers to sign the proclamation against his will.[101] In spite of the significant loss of power that the Mughal dynasty had suffered in the preceding centuries, their name still carried great prestige across northern India.[91] Civilians, nobility and other dignitaries took an oath of allegiance. The emperor issued coins in his name, one of the oldest ways of asserting imperial status. The adhesion of the Mughal emperor, however, turned the Sikhs of the Punjab away from the rebellion, as they did not want to return to Islamic rule, having fought many wars against the Mughal rulers. The province of Bengal was largely quiet throughout the entire period. The British, who had long ceased to take the authority of the Mughal Emperor seriously, were astonished at how the ordinary people responded to Bahadur Shah's call for war.[91]

Initially, the Indian rebels were able to push back Company forces, and captured several important towns in Haryana, Bihar, the Central Provinces and the United Provinces. When British troops were reinforced and began to counterattack, the mutineers were especially handicapped by their lack of centralized command and control. Although the rebels produced some natural leaders such as Bakht Khan, whom the Emperor later nominated as commander-in-chief after his son Mirza Mughal proved ineffectual, for the most part they were forced to look for leadership to rajahs and princes. Some of these were to prove dedicated leaders, but others were self-interested or inept.[citation needed]

In the countryside around Meerut, a general Gurjar uprising posed the largest threat to the British. In Parikshitgarh near Meerut, Gurjars declared Rao Kadam Singh (Kuddum Singh) their leader, and expelled Company police. Kadam Singh Gurjar led a large force, estimates varying from 2,000 to 10,000.[102] Bulandshahr and Bijnor also came under the control of Gurjars under Walidad Khan and Maho Singh respectively. Contemporary sources report that nearly all the Gurjar villages between Meerut and Delhi participated in the revolt, in some cases with support from Jullundur, and it was not until late July that, with the help of local Jats, and the princely states, the British managed to regain control of the area.[102]

The Imperial Gazetteer of India states that throughout the Indian Rebellion of 1857, Gurjars and Ranghars proved the "most irreconcilable enemies" of the British in the Bulandshahr area.[103]

Mufti Nizamuddin, a renowned scholar of Lahore, issued a Fatwa against the British forces and called upon the local population to support the forces of Rao Tula Ram. Casualties were high at the subsequent engagement at Narnaul (Nasibpur). After the defeat of Rao Tula Ram on 16 November 1857, Mufti Nizamuddin was arrested, and his brother Mufti Yaqinuddin and brother-in-law Abdur Rahman (alias Nabi Baksh) were arrested in Tijara. They were taken to Delhi and hanged.[104]

Siege of Delhi

[edit]

The British were slow to strike back at first. It took time for troops stationed in Britain to make their way to India by sea, although some regiments moved overland through Persia from the Crimean War, and some regiments already en route for China were diverted to India.[citation needed]

It took time to organise the British troops already in India into field forces, but eventually two columns left Meerut and Simla. They proceeded slowly towards Delhi and fought, killed, and hanged numerous Indians along the way. Two months after the first outbreak of rebellion at Meerut, the two forces met near Karnal. The combined force, including two Gurkha units serving in the Bengal Army under contract from the Kingdom of Nepal, fought the rebels' main army at Badli-ke-Serai and drove them back to Delhi.[citation needed]

The company's army established a base on the Delhi ridge to the north of the city and the Siege of Delhi began. The siege lasted roughly from 1 July to 21 September. However, the encirclement was hardly complete, and for much of the siege the besiegers were outnumbered and it often seemed that it was the Company forces and not Delhi that were under siege, as the rebels could easily receive resources and reinforcements. For several weeks, it seemed likely that disease, exhaustion and continuous sorties by rebels from Delhi would force the besiegers to withdraw, but the outbreaks of rebellion in the Punjab were forestalled or suppressed, allowing the Punjab Movable Column of British, Sikh and Pashtun soldiers under John Nicholson to reinforce the besiegers on the Ridge on 14 August.[105] On 30 August the rebels offered terms, which were refused.[106]

-

The Jantar Mantar observatory in Delhi in 1858, damaged in the fighting

-

Mortar damage to Kashmiri Gate, Delhi, 1858

-

Hindu Rao's house in Delhi, now a hospital, was extensively damaged in the fighting.

-

The Bank of Delhi was attacked by mortar and gunfire.

An eagerly awaited heavy siege train joined the besieging force, and from 7 September, the siege guns battered breaches in the walls and silenced the rebels' artillery.[107]: 478 An attempt to storm the city through the breaches and the Kashmiri Gate was launched on 14 September.[107]: 480 The attackers gained a foothold within the city but suffered heavy casualties, including John Nicholson. Major General Archdale Wilson, the British commander, wished to withdraw, but was persuaded to hold on by his junior officers. After a week of street fighting, the British reached the Red Fort. Bahadur Shah Zafar had already fled to Humayun's tomb.

The troops of the besieging force proceeded to loot and pillage the city. A large number of citizens were killed in retaliation for the British and Indian civilians that had been slaughtered by the rebels. During the street fighting, artillery was set up in the city's main mosque. Neighbourhoods within range were bombarded; the homes of the Muslim nobility that housed innumerable cultural, artistic, literary and monetary riches were destroyed.[citation needed]

The British soon arrested Bahadur Shah Zafar, and the next day the British Major William Hodson had his sons Mirza Mughal and Mirza Khizr Sultan and grandson Mirza Abu Bakr shot under his own authority at the Khooni Darwaza (the bloody gate) near Delhi Gate. On hearing the news, Zafar reacted with shocked silence, while his wife Zinat Mahal was content, as she believed her son was now Zafar's heir.[108] Shortly after the fall of Delhi, the victorious attackers organised a column that relieved another besieged Company force in Agra, and then pressed on to Cawnpore, which had also recently been retaken. This gave the Company forces a continuous, although still tenuous, line of communication from the east to the west of India.[citation needed]

Cawnpore (Kanpur)

[edit]

In June, sepoys under General Wheeler in Cawnpore (now Kanpur) rebelled and besieged the British entrenchment. Wheeler was not only a veteran and respected soldier but also married to an Indian woman. He had relied on his own prestige and his cordial relations with local landholder and hereditary prime minister Nana Sahib to thwart rebellion, and took comparatively few measures to prepare fortifications and lay in supplies and ammunition.[citation needed]

Advised by his trusted consultant Azimullah Khan, Nana Sahib led the rebels at Kanpur rather than join the Mughals in Delhi.[109] The besieged endured three weeks of the Siege of Cawnpore with little water or food, suffering continuous casualties among men, women and children. On 25 June Nana Sahib made an offer of safe passage to Allahabad. With barely three days' food rations remaining, the British agreed, provided they could keep their small arms and that the evacuation should take place in daylight on the morning of the 27th (the Nana Sahib wanted the evacuation to take place on the night of the 26th). Early in the morning of 27 June, the British party left their entrenchment and made their way to the river where boats provided by the Nana Sahib were waiting to take them to Allahabad.[110] Several sepoys who had stayed loyal to the company were removed by the mutineers and killed, either because of their loyalty or because "they had become Christian". A few injured British officers trailing the column were also apparently hacked to death by angry sepoys. After the British party had largely arrived at the dock, which was surrounded by sepoys positioned on both banks of the Ganges,[111] with clear lines of fire, firing broke out and the boats were abandoned by their crew, and caught or were set[112] on fire using pieces of red-hot charcoal.[113] The British party tried to push the boats off but all except three remained stuck. One boat with over a dozen wounded men initially escaped, but later grounded, was caught by mutineers and pushed back down the river towards the carnage at Cawnpore. Towards the end, rebel cavalry rode into the water to finish off any survivors.[113] After the firing ceased the survivors were rounded up and the men shot.[113] By the time the massacre was over, most of the male members of the party were dead while the surviving women and children were removed and held hostage to be later killed in the Bibighar massacre.[114] Only four men eventually escaped alive from Cawnpore on one of the boats: two private soldiers, a lieutenant, and Captain Mowbray Thomson, who wrote a first-hand account of his experiences entitled The Story of Cawnpore (London, 1859).[citation needed]

During his trial, Tatya Tope denied the existence of any such plan and described the incident in the following terms: the British had already boarded the boats and Tatya Tope raised his right hand to signal their departure. That very moment someone from the crowd blew a loud bugle, which created disorder and in the ongoing bewilderment, the boatmen jumped off the boats. The rebels started shooting indiscriminately. Nana Sahib, who was staying in Savada Kothi (Bungalow) nearby, was informed about what was happening and immediately came to stop it.[115] Some British histories allow that it might well have been the result of accident or error; someone accidentally or maliciously fired a shot, the panic-stricken British opened fire, and it became impossible to stop the massacre.[83]: 56

The surviving women and children were taken to Nana Sahib and then confined first to the Savada Kothi and then to the home of the local magistrate's clerk (the Bibighar)[116] where they were joined by refugees from Fatehgarh. Overall, five men and 206 women and children were confined in the Bibigarh for about two weeks. In one week 25 were brought out, dead from dysentery and cholera.[112] Meanwhile, a Company relief force that had advanced from Allahabad defeated the Indians and by 15 July it was clear that Nana Sahib would not be able to hold Cawnpore and a decision was made by Nana Sahib and other leading rebels that the hostages must be killed. After the sepoys refused to carry out this order, two Muslim butchers, two Hindu peasants and one of Nana's bodyguards went into the Bibigarh. Armed with knives and hatchets, they murdered the women and children.[117] After the massacre, the walls were covered in bloody handprints, and the floor littered with parts of human limbs.[118] The dead and the dying were thrown down a nearby well. When the 50-foot (15 m) deep well was filled with remains to within 6 feet (1.8 m) of the top,[119] the remainder were thrown into the Ganges.[120]

Historians have given many reasons for this act of cruelty. With Company forces approaching Cawnpore, some believed that they would not advance if there were no hostages to save. Or perhaps it was to ensure that no information was leaked after the fall of Cawnpore. Other historians have suggested that the killings were an attempt to undermine Nana Sahib's relationship with the British.[117] Perhaps it was due to fear, the fear of being recognised by some of the prisoners for having taken part in the earlier firings.[114]

-

Photograph entitled, "The Hospital in General Wheeler's entrenchment, Cawnpore". (1858) The hospital was the site of the first major loss of British lives in Cawnpore

-

1858 picture of Sati Chaura Ghat on the banks of the Ganges River, where on 27 June 1857 many British men lost their lives and the surviving women and children were taken prisoner by the rebels.

-

Bibigarh house where British women and children were killed and the well where their bodies were found, 1858.

-

The Bibighar Well site where a memorial had been built. Samuel Bourne, 1860.

The killing of the women and children hardened British attitudes against the sepoys. The British public was aghast, and the anti-Imperial and pro-Indian proponents lost all of their support. Cawnpore became a war cry for the British and their allies for the rest of the conflict. Nana Sahib disappeared near the end of the rebellion, and it is not known what happened to him.[citation needed]

Other British accounts[121][122][123] state that indiscriminate punitive measures were taken in early June, two weeks before the murders at the Bibighar (but after those at both Meerut and Delhi), specifically by Lieutenant Colonel James George Smith Neill of the Madras Fusiliers, commanding at Allahabad, while moving towards Cawnpore. At the nearby town of Fatehpur, a mob had attacked and murdered the local British population. On this pretext, Neill ordered all villages beside the Grand Trunk Road to be burned and their inhabitants to be hanged. Neill's methods were "ruthless and horrible",[83]: 53 and far from intimidating the population, may well have induced previously undecided sepoys and communities to revolt.[citation needed]

Neill was killed in action at Lucknow on 26 September and was never called to account for his punitive measures, though contemporary British sources lionised him and his "gallant blue caps".[s] When the British retook Cawnpore, the soldiers took their sepoy prisoners to the Bibighar and forced them to lick the bloodstains from the walls and floor.[124] They then hanged or "blew from the cannon", the traditional Mughal punishment for mutiny, the majority of the sepoy prisoners. Although some claimed the sepoys took no actual part in the killings themselves, they did not act to stop it and this was acknowledged by Captain Thompson after the British departed Cawnpore for a second time.[citation needed]

Lucknow

[edit]

Very soon after the events at Meerut, rebellion erupted in the state of Awadh (also known as Oudh, in modern-day Uttar Pradesh), which had been annexed barely a year before. The British Commissioner resident at Lucknow, Sir Henry Lawrence, had enough time to fortify his position inside the Residency compound. The defenders, including loyal sepoys, numbered some 1700 men. The rebels' assaults were unsuccessful, so they began a barrage of artillery and musket fire into the compound. Lawrence was one of the first casualties. He was succeeded by John Eardley Inglis. The rebels tried to breach the walls with explosives and bypass them via tunnels that led to underground close combat.[107]: 486 After 90 days of siege, the defenders were reduced to 300 loyal sepoys, 350 British soldiers and 550 non-combatants.[citation needed]

On 25 September, a relief column under the command of Sir Henry Havelock and accompanied by Sir James Outram (who in theory was his superior) fought its way from Cawnpore to Lucknow in a brief campaign, in which the numerically small column defeated rebel forces in a series of increasingly large battles. This became known as 'The First Relief of Lucknow', as this force was not strong enough to break the siege or extricate themselves, and so was forced to join the garrison. In October, another larger army under the new Commander-in-Chief, Sir Colin Campbell, was finally able to relieve the garrison and on 18 November, they evacuated the defended enclave within the city, the women and children leaving first. They then conducted an orderly withdrawal, firstly to Alambagh 4 miles (6.4 km) north where a force of 4,000 were left to construct a fort, then to Cawnpore, where they defeated an attempt by Tantia Tope to recapture the city in the Second Battle of Cawnpore.[citation needed]

In March 1858, Campbell once again advanced on Lucknow with a large army, meeting up with the force at Alambagh, this time seeking to suppress the rebellion in Awadh. He was aided by a large Nepalese contingent advancing from the north under Jung Bahadur Kunwar Rana.[125] General Dhir Shamsher Kunwar Rana, the youngest brother of Jung Bahadur, also led the Nepalese forces in various parts of India including Lucknow, Benares and Patna.[1][126] Campbell's advance was slow and methodical, with a force under General Outram crossing the river on cask bridges on 4 March to enable them to fire artillery in flank. Campbell drove the large but disorganised rebel army from Lucknow with the final fighting taking place on 21 March.[107]: 491 There were few casualties to Campbell's own troops, but his cautious movements allowed large numbers of the rebels to disperse into Awadh. Campbell was forced to spend the summer and autumn dealing with scattered pockets of resistance while losing men to heat, disease and guerrilla actions.[citation needed]

Jhansi

[edit]

Jhansi State was a Maratha-ruled princely state in Bundelkhand. When the Raja of Jhansi died without a biological male heir in 1853, it was annexed to the British Raj by the Governor-General of India under the doctrine of lapse. His widow Rani Lakshmi Bai, the Rani of Jhansi, protested against the denial of rights of their adopted son. When war broke out, Jhansi quickly became a centre of the rebellion. A small group of Company officials and their families took refuge in Jhansi Fort, and the Rani negotiated their evacuation. However, when they left the fort they were massacred by the rebels over whom the Rani had no control; the British suspected the Rani of complicity, despite her repeated denials.[citation needed]

By the end of June 1857, the company had lost control of much of Bundelkhand and eastern Rajputana. The Bengal Army units in the area, having rebelled, marched to take part in the battles for Delhi and Cawnpore. The many princely states that made up this area began warring amongst themselves. In September and October 1857, the Rani led the successful defence of Jhansi against the invading armies of the neighbouring rajas of Datia and Orchha.[citation needed]

On 3 February, Sir Hugh Rose broke the 3-month siege of Saugor. Thousands of local villagers welcomed him as a liberator, freeing them from rebel occupation.[127]

In March 1858, the Central India Field Force, led by Sir Hugh Rose, advanced on and laid siege to Jhansi. The Company forces captured the city, but the Rani fled in disguise.[citation needed]

After being driven from Jhansi and Kalpi, on 1 June 1858 Rani Lakshmi Bai and a group of Maratha rebels captured the fortress city of Gwalior from the Scindia rulers, who were British allies. This might have reinvigorated the rebellion, but the Central India Field Force very quickly advanced against the city. The Rani died on 17 June, the second day of the Battle of Gwalior, probably killed by a carbine shot from the 8th King's Royal Irish Hussars according to the account of three independent Indian representatives. The Company forces recaptured Gwalior within the next three days. In descriptions of the scene of her last battle, she was compared to Joan of Arc by some commentators.[128]

Indore

[edit]Colonel Henry Marion Durand, the then-Company resident at Indore, had brushed away any possibility of uprising in Indore. However, on 1 July, sepoys in Holkar's army revolted and opened fire on the cavalry pickets of the Bhopal Contingent (a locally raised force with British officers). When Colonel Travers rode forward to charge, the Bhopal Cavalry refused to follow. The Bhopal Infantry also refused orders and instead levelled their guns at British sergeants and officers. Since all possibility of mounting an effective deterrent was lost, Durand decided to gather up all the British residents and escape, although 39 British residents of Indore were killed.[129]

Bihar

[edit]The rebellion in Bihar was mainly concentrated in the Western regions of the state; however, there were also some outbreaks of plundering and looting in Gaya district.[130] One of the central figures was Kunwar Singh, the 80-year-old Rajput Zamindar of Jagdishpur (Bhojpur district), whose estate was in the process of being sequestrated by the Revenue Board, instigated and assumed the leadership of revolt in Bihar.[131] His efforts were supported by his brother Babu Amar Singh and his commander-in-chief Hare Krishna Singh.[132]

On 25 July, mutiny erupted in the garrisons of Danapur. Mutinying sepoys from the 7th, 8th and 40th regiments of Bengal Native Infantry quickly moved towards the city of Arrah and were joined by Kunwar Singh and his men.[133] Mr. Boyle, a British railway engineer in Arrah, had already prepared an outbuilding on his property for defence against such attacks.[134] As the rebels approached Arrah, all British residents took refuge at Mr. Boyle's house.[135] A siege soon ensued – eighteen civilians and 50 loyal sepoys from the Bengal Military Police Battalion under the command of Herwald Wake, the local magistrate, defended the house against artillery and musketry fire from an estimated 2000 to 3000 mutineers and rebels.[136]

On 29 July 400 men were sent out from Danapur to relieve Arrah, but this force was ambushed by the rebels around a mile away from the siege house, severely defeated, and driven back. On 30 July, Major Vincent Eyre, who was going up the river with his troops and guns, reached Buxar and heard about the siege. He immediately disembarked his guns and troops (the 5th Fusiliers) and started marching towards Arrah, disregarding direct orders not to do so.[137] On 2 August, some 6 miles (9.7 km) short of Arrah, the Major was ambushed by the mutineers and rebels. After an intense fight, the 5th Fusiliers charged and stormed the rebel positions successfully.[136] On 3 August, Major Eyre and his men reached the siege house and successfully ended the siege.[138][139]

After receiving reinforcements, Major Eyre pursued Kunwar Singh to his palace in Jagdispur; however, Singh had left by the time Eyre's forces arrived. Eyre then proceeded to destroy the palace and the homes of Singh's brothers.[136]

In addition to Kunwar Singh's efforts, there were also rebellions carried out by Hussain Baksh Khan, Ghulam Ali Khan and Fateh Singh among others in Gaya, Nawada and Jehanabad districts.[140]

In Barkagarh Estate of South Bihar (now in Jharkhand), a major rebellion was led by Thakur Vishwanath Shahdeo who was part of the Nagavanshi dynasty.[141] He was motivated by disputes he had with the Christian Kol tribals who had been grabbing his land and were implicitly supported by the British authorities. The rebels in South Bihar asked him to lead them and he readily accepted this offer. He organised a Mukti Vahini (Liberation Regiment) with the assistance of nearby zamindars including Pandey Ganpat Rai and Nadir Ali Khan.[141]

Other regions

[edit]Punjab and Afghan Frontier

[edit]

What was then referred to by the British as the Punjab was a very large administrative division, centred on Lahore. It included not only the present-day Indian and Pakistani Punjabi regions but also the North West Frontier districts bordering Afghanistan.[citation needed]

Much of the region had been the Sikh Empire, ruled by Ranjit Singh until his death in 1839. The empire had then fallen into disorder, with court factions and the Khalsa (Orthodox Sikhs) contending for power at the Lahore Durbar (court). After two Anglo-Sikh Wars, the entire region was annexed by the East India Company in 1849. In 1857, the region still contained the highest numbers of both British and Indian troops.[citation needed]

The inhabitants of the Punjab were not as sympathetic to the sepoys as they were elsewhere in India, which limited many of the outbreaks in the Punjab to disjointed uprisings by regiments of sepoys isolated from each other. In some garrisons, notably Ferozepore, indecision on the part of the senior British officers allowed the sepoys to rebel, but the sepoys then left the area, mostly heading for Delhi.[citation needed] At the most important garrison, that of Peshawar close to the Afghan frontier, many comparatively junior officers ignored their nominal commander, General Reed, and took decisive action. They intercepted the sepoys' mail, thus preventing their coordinating an uprising, and formed a force known as the "Punjab Movable Column" to move rapidly to suppress any revolts as they occurred. When it became clear from the intercepted correspondence that some of the sepoys at Peshawar were on the point of open revolt, the four most disaffected Bengal Native regiments were disarmed by the two British infantry regiments in the cantonment, backed by artillery, on 22 May. This decisive act induced many local chieftains to side with the British.[142]: 276

Jhelum in Punjab saw a mutiny of native troops against the British. Here 35 British soldiers of Her Majesty's 24th Regiment of Foot (South Wales Borderers) were killed by mutineers on 7 July 1857. Among the dead was Captain Francis Spring, the eldest son of Colonel William Spring. To commemorate this event St. John's Church Jhelum was built and the names of those 35 British soldiers are carved on a marble lectern present in that church.[citation needed]

The final large-scale military uprising in the Punjab took place on 9 July, when most of a brigade of sepoys at Sialkot rebelled and began to move to Delhi.[143] They were intercepted by John Nicholson with an equal British force as they tried to cross the Ravi River. After fighting steadily but unsuccessfully for several hours, the sepoys tried to fall back across the river but became trapped on an island. Three days later, Nicholson annihilated the 1,100 trapped sepoys in the Battle of Trimmu Ghat.[142]: 290–293

The British had been recruiting irregular units from Sikh and Pashtun communities even before the first unrest among the Bengal units, and the numbers of these were greatly increased during the rebellion, 34,000 fresh levies eventually being pressed into service.[144]

At one stage, faced with the need to send troops to reinforce the besiegers of Delhi, the Commissioner of the Punjab (Sir John Lawrence) suggested handing the coveted prize of Peshawar to Dost Mohammad Khan of Afghanistan in return for a pledge of friendship. The British agents in Peshawar and the adjacent districts were horrified. Referring to the massacre of a retreating British Army in 1842, Herbert Edwardes wrote, "Dost Mahomed would not be a mortal Afghan ... if he did not assume our day to be gone in India and follow after us as an enemy. British cannot retreat – Kabul would come again."[142]: 283 In the event Lord Canning insisted on Peshawar being held, and Dost Mohammad, whose relations with Britain had been equivocal for over 20 years, remained neutral.[citation needed]

In September 1858 Rai Ahmad Khan Kharal, head of the Kharal tribe, led an insurrection in the Neeli Bar district, between the Sutlej, Ravi and Chenab rivers. The rebels held the forests of Gogaira and had some initial successes against the British forces in the area, besieging Major Crawford Chamberlain at Chichawatni. A squadron of Punjabi cavalry sent by Sir John Lawrence raised the siege. Ahmed Khan was killed but the insurgents found a new leader in Mahr Bahawal Fatyana, who maintained the uprising for three months until Government forces penetrated the jungle and scattered the rebel tribesmen.[78]: 343–344

Bengal and Tripura

[edit]In September 1857, sepoys took control of the treasury in Chittagong.[145] The treasury remained under rebel control for several days. Further mutinies on 18 November saw the 2nd, 3rd and 4th companies of the 34th Bengal Infantry Regiment storming the Chittagong Jail and releasing all prisoners. The mutineers were eventually suppressed by the Gurkha regiments.[146] The mutiny also spread to Kolkata and later Dhaka, the former Mughal capital of Bengal. Residents in the city's Lalbagh area were kept awake at night by the rebellion.[147] Sepoys joined hands with the common populace in Jalpaiguri to take control of the city's cantonment.[145] In January 1858, many sepoys received shelter from the royal family of the princely state of Hill Tippera.[145]

The interior areas of Bengal proper were already experiencing growing resistance to Company rule due to the Muslim Faraizi movement.[145]

Gujarat

[edit]In central and north Gujarat, the rebellion was sustained by landowner jagirdars, taluqdar and thakurs with the support of armed communities of Bhil, Koli, Pathans and Arabs, unlike the mutiny by sepoys in north India. Their main opposition of British was due to Inam commission. The Bet Dwarka island, along with Okhamandal region of Kathiawar peninsula which was under the Gaekwad of Baroda State, saw a revolt by the Waghers in January 1858 who, by July 1859, controlled that region. In October 1859, a joint offensive by British, Gaekwad and other princely states troops ousted the rebels and recaptured the region.[148][149][150]

Orissa

[edit]During the rebellion, Surendra Sai was one of the many people broken out of Hazaribagh jail by mutineers.[151] In the middle of September Surendra established himself in Sambalpur's old fort. He quickly organised a meeting with the Assistant Commissioner (Captain Leigh), and Leigh agreed to ask the government to cancel his and his brother's imprisonment while Surendra dispersed his followers. This agreement was soon broken, however, when on 31 September escaped the town and make for Khinda, where his brother was located with a 1,400-man force.[151] The British quickly moved to send two companies from the 40th Madras Native Infantry from Cuttack on 10 October, and after a forced march reached Khinda on 5 November, only to find the place abandoned as the rebels retreated to the jungle. Much of the country of Sambalpur was under the rebels' control, and they maintained a hit and run guerrilla war for quite some time. In December the British made further preparations to crush the uprising in Sambalpur, and it was temporarily transferred from the Chota Nagpur Division into the Orissa Division of the Bengal Presidency. On the 30th a major battle was fought in which Surendra's brother was killed and the mutineers were routed. In January the British achieved minor successes, capturing a few major villages like Kolabira, and in February calm began to be restored. However, Surendra still held out, and the jungle hampered British parties from capturing him. Additionally, any native daring to collaborate with the British were terrorized along with their family. After a new policy that promised amnesty for mutineers, Surendra surrendered in May 1862.[151]

Shamli

[edit]In September 1857, Shamli, then a tahsil of Muzaffarnagar district in the North-Western Provinces (now Uttar Pradesh), witnessed a local uprising during the Indian Rebellion of 1857. Chaudhary Mohar Singh, a Jat zamindar of Maulaheri, led villagers and allied groups in attacking the tahsil headquarters, setting fire to government offices and briefly seizing control of the town. The action disrupted British administration and supply routes in the region.[152][153]

British troops subsequently recaptured Shamli, and executed Mohar Singh. Contemporary colonial accounts describe his body being displayed publicly as a warning to others.[154][155]

British Empire

[edit]The authorities in British colonies with an Indian population, sepoy or civilian, took measures to secure themselves against copycat uprisings. In the Straits Settlements and Trinidad the annual Hosay processions were banned,[156] riots broke out in penal settlements in Burma and the Settlements, in Penang the loss of a musket provoked a near riot,[157] and security was boosted especially in locations with an Indian convict population.[158]

Consequences

[edit]Death toll and atrocities

[edit]

Both sides committed atrocities against civilians.[t][15]

In Oudh alone, some estimates put the toll at 150,000 Indians killed during the war, with 100,000 of them being civilians. The capture of Delhi, Allahabad, Kanpur and Lucknow by British forces were followed by general massacres.[159]

Another notable atrocity was carried out by General Neill who massacred thousands of Indian mutineers and Indian civilians suspected of supporting the rebellion.[160]

The rebels' murder of British women, children and wounded soldiers (including sepoys who sided with the British) at Cawnpore, and the subsequent printing of the events in the British papers, left many British soldiers outraged and seeking revenge. Aside from hanging mutineers, the British had some "blown from cannon", (an old Mughal punishment adopted many years before in India), in which sentenced rebels were tied over the mouths of cannons and blown to pieces when the cannons were fired.[161][162] A particular act of cruelty on behalf of the British troops at Cawnpore included forcing many Muslim or Hindu rebels to eat pork or beef, as well as licking buildings freshly stained with blood of the dead before subsequent public hangings.[162]

Practices of torture included "searing with hot irons...dipping in wells and rivers till the victim is half suffocated... squeezing the testicles...putting pepper and red chillies in the eyes or introducing them into the private parts of men and women...prevention of sleep...nipping the flesh with pinners...suspension from the branches of a tree...imprisonment in a room used for storing lime..."[163]

British soldiers also committed sexual violence against Indian women as a form of retaliation against the rebellion.[164][165] As towns and cities were captured from the sepoys, the British soldiers took their revenge on Indian civilians by committing atrocities and rapes against Indian women.[166][167][168][169][170]

Most of the British press, outraged by the stories of alleged rape committed by the rebels against British women, as well as the killings of British civilians and wounded British soldiers, did not advocate clemency of any kind towards the Indian population.[171] Governor General Canning ordered moderation in dealing with native sensibilities and earned the scornful sobriquet "Clemency Canning" from the press[172] and later parts of the British public.

In terms of sheer numbers, the casualties were much higher on the Indian side. A letter published after the fall of Delhi in the Bombay Telegraph and reproduced in the British press testified to the scale of the Indian casualties:

.... All the city's people found within the walls of the city of Delhi when our troops entered were bayoneted on the spot, and the number was considerable, as you may suppose, when I tell you that in some houses forty and fifty people were hiding. These were not mutineers but residents of the city, who trusted to our well-known mild rule for pardon. I am glad to say they were disappointed.[173]

From the end of 1857, the British had begun to gain ground again. Lucknow was retaken in March 1858. On 8 July 1858, a peace treaty was signed, and the rebellion ended. The last rebels were defeated in Gwalior on 20 June 1858. By 1859, rebel leaders Bakht Khan and Nana Sahib had either been slain or had fled.[citation needed]

Edward Vibart, a 19-year-old officer whose parents, younger brothers, and two of his sisters had died in the Cawnpore massacre,[174] recorded his experience:

The orders went out to shoot every soul.... It was literally murder... I have seen many bloody and awful sights lately but such a one as I witnessed yesterday I pray I never see again. The women were all spared but their screams on seeing their husbands and sons butchered, were most painful... Heaven knows I feel no pity, but when some old grey bearded man is brought and shot before your very eyes, hard must be that man's heart I think who can look on with indifference ...[175]

Some British troops adopted a policy of "no prisoners". One officer, Thomas Lowe, remembered how on one occasion his unit had taken 76 prisoners – they were just too tired to carry on killing and needed a rest, he recalled. Later, after a quick trial, the prisoners were lined up with a British soldier standing a couple of yards in front of them. On the order "fire", they were all simultaneously shot, "swept... from their earthly existence".[citation needed]

The aftermath of the rebellion has been the focus of new work using Indian sources and population studies. In The Last Mughal, historian William Dalrymple examines the effects on the Muslim population of Delhi after the city was retaken by the British and finds that intellectual and economic control of the city shifted from Muslim to Hindu hands because the British, at that time, saw an Islamic hand behind the mutiny.[176]

Approximately 6,000 of the 40,000 British living in India were killed.[2]

Reaction in Britain

[edit]

The scale of the punishments handed out by the British "Army of Retribution" was considered largely appropriate and justified in a Britain shocked by embellished reports of atrocities carried out against British troops and civilians by the rebels.[177] Accounts of the time frequently reach the "hyperbolic register", according to Christopher Herbert, especially in the often-repeated claim that the "Red Year" of 1857 marked "a terrible break" in British experience.[173] Such was the atmosphere – a national "mood of retribution and despair" that led to "almost universal approval" of the measures taken to pacify the revolt.[178]: 87

Incidents of rape allegedly committed by Indian rebels against British women and girls appalled the British public. These atrocities were often used to justify the British reaction to the rebellion. British newspapers printed various eyewitness accounts of the rape of English women and girls. One such account was published by The Times, regarding an incident where 48 English girls as young as 10 had been raped by Indian rebels in Delhi. Karl Marx criticized this story as false propaganda, and pointed out that the story was written by a clergyman in Bangalore, far from the events of the rebellion, with no evidence to support his allegation.[179] Individual incidents captured the public's interest and were heavily reported by the press. One such incident was that of General Wheeler's daughter Margaret being forced to live as her captor's concubine, though this was reported to the Victorian public as Margaret killing her rapist then herself.[180] Another version of the story suggested that Margaret had been killed after her abductor had argued with his wife over her.[181]

During the aftermath of the rebellion, a series of exhaustive investigations were carried out by British police and intelligence officials into reports that British women prisoners had been "dishonoured" at the Bibighar and elsewhere. One such detailed enquiry was at the direction of Lord Canning. The consensus was that there was no convincing evidence of such crimes having been committed, although numbers of British women and children had been killed outright.[182]

The term 'Sepoy' or 'Sepoyism' became a derogatory term for nationalists, especially in Ireland.[183]

Reorganisation

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2017) |

Bahadur Shah II was arrested at Humayun's Tomb and tried for treason by a military commission assembled at Delhi and exiled to Rangoon where he died in 1862, bringing the Mughal dynasty to an end. In 1877 Queen Victoria took the title of Empress of India on the advice of Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli.[184]

The rebellion saw the end of the East India Company's rule in India. In August, by the Government of India Act 1858, the company's ruling powers over India were transferred to the British Crown.[185] A new British government department, the India Office, was created to handle the governance of India, and its head, the Secretary of State for India, was entrusted with formulating Indian policy. The Governor-General of India gained a new title, Viceroy of India, and implemented the policies devised by the India Office. Some former East India Company territories, such as the Straits Settlements, became colonies in their own right. The British colonial administration embarked on a program of reform, trying to integrate Indian higher castes and rulers into the government and abolishing attempts at Westernization. The Viceroy stopped land grabs, decreed religious tolerance and admitted Indians into civil service, albeit mainly as subordinates.[citation needed]

Essentially the old East India Company bureaucracy remained, though there was a major shift in attitudes. In looking for the causes of the Rebellion the authorities alighted on two things: religion and the economy. On religion it was felt that there had been too much interference with indigenous traditions, both Hindu and Muslim. On the economy it was now believed that the previous attempts by the company to introduce free market competition had undermined traditional power structures and bonds of loyalty placing the peasantry at the mercy of merchants and moneylenders. In consequence the new British Raj was constructed in part around a conservative agenda, based on a preservation of tradition and hierarchy.[citation needed]

On a political level it was also felt that the previous lack of consultation between rulers and ruled had been another significant factor in contributing to the uprising. In consequence, Indians were drawn into government at a local level. Though this was on a limited scale a crucial precedent had been set, with the creation of a new 'white collar' Indian elite, further stimulated by the opening of universities at Calcutta, Bombay and Madras, a result of the Indian Universities Act. So, alongside the values of traditional and ancient India, a new professional middle class was starting to arise, in no way bound by the values of the past. Their ambition can only have been stimulated by Queen Victoria's Proclamation of November 1858, in which it is expressly stated, "We hold ourselves bound to the natives of our Indian territories by the same obligations of duty which bind us to our other subjects...it is our further will that... our subjects of whatever race or creed, be freely and impartially admitted to offices in our service, the duties of which they may be qualified by their education, ability and integrity, duly to discharge."[citation needed]

Acting on these sentiments, Lord Ripon, viceroy from 1880 to 1885, extended the powers of local self-government and sought to remove racial practices in the law courts by the Ilbert Bill. But a policy at once liberal and progressive at one turn was reactionary and backward at the next, creating new elites and confirming old attitudes. The Ilbert Bill had the effect only of causing a white mutiny and the end of the prospect of perfect equality before the law. In 1886 measures were adopted to restrict Indian entry into the civil service.[citation needed]

Military Reorganisation

[edit]

The Bengal Army dominated the Presidency armies before 1857 and a direct result after the rebellion was the scaling back of the size of the Bengali contingent in the army.[186] The Brahmin presence in the Bengal Army was reduced because of their perceived primary role as mutineers. The British looked for increased recruitment in the Punjab for the Bengal army as a result of the apparent discontent that resulted in the Sepoy conflict.[187]