Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

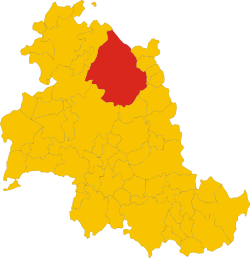

Gubbio

View on WikipediaGubbio (Italian pronunciation: [ˈɡubbjo]) is an Italian town and comune in the far northeastern part of the Italian province of Perugia (Umbria). It is located on the lowest slope of Mt. Ingino, a small mountain of the Apennines.

Key Information

History

[edit]Prehistory

[edit]The oldest evidence of human habitation in the Gubbio valley dates back to the Middle Palaeolithic, but only during the Neolithic period (6000–3000 BCE) does the earliest evidence of relatively permanent settlements emerge.[3] Agriculture and animal husbandry were introduced to the valley around the 6th to 5th millennium BCE.[4]: 67 Stone tools (made of local chert) and pottery have been found from this period. The styles and decorations of the pottery have a resemblance to contemporary finds from Marche and Lazio. At the excavated site of San Marco, east of Gubbio, archaeologists found a ditch with various almost-intact ceramic vessels, which may indicate a deliberate deposit as part of some sort of ritual.[3]

Little evidence has been found from the Chalcolithic period (3500–2300 BCE) in the Gubbio valley.[3]

Bronze Age

[edit]During the Middle to Late Bronze Age (1400–1200 BCE), there appears to have been a significant increase in population throughout the region.[3] Beginning around 1400 BCE, there appears to have been a major shift in the settlement pattern in the Gubbio valley: from dispersed habitation of the valley below to "the occupation of a single, strategically placed, upland site": Monte Ingino. This site, on a hilltop overlooking present-day Gubbio,[3] was "probably chosen because of its naturally defended position, good visibility of surrounding terrain, and access to surrounding pasture".[5]: 178 The settlement at Monte Ingino was polyfocal, with people inhabiting sites on the slopes below the summit (such as Via dei Consoli and Vescovado), while the mountaintop itself, with its harsher climate, was only occupied seasonally, during spring.[3] The valley below was under human use, as indicated by "sporadic finds", but no actual settlement existed there.[5]: 178

The summit of Monte Ingino was "undoubtedly" the focus of ritual activity.[5]: 178 An enormous amount of archaeological material has been found here, including some 30,000 pottery fragments and more than 25,000 animal bone fragments. These appear to have been part of some consumption ritual: a huge feast that served as a "communal display" to neighboring communities, who would have been able to see the smoke from the cooking fire;[3] this ritual may have been performed by specific individuals "while placed in this outpost above the territory over which they had to maintain control".[5]: 178 Later, in the Archaic period, this ritual appears to have become much more formalized.[3]

Later, around 1200–1100 BCE, another settlement area was established on the neighboring hilltop of Monte Asciano. This site served as a less prominent ritual center, and may have also been covered by a settlement, although only one hut has been excavated here. Occupation of Monte Asciano continued until about 950 BCE, when the local population all moved to the slopes below.[5]: 178–9

The Gubbio valley in the Bronze Age would have still been covered by "a moist woodland environment which remained relatively cool and moist during the summer months". This period is probably the first time when people started cutting down significant parts of these woods to clear space for agriculture. Agricultural technology at the time was probably similar to that of Northern Europe during the Iron Age, with light wooden ards pulled by animals. Barley may have been cultivated on some of the gentler slopes near Monte Ingino and Monte Asciano. Pigs, whose bones make up a large portion of the bones found, could have been kept close to the settlements, where they would have readily consumed household food scraps, and then also taken to local woodlands, which would have been a great food source for them. Cows, whose bones are rather uncommon, may have also been kept; they could have been pastured in either naturally open areas or artificial clearings. Sheep and goats were most likely kept and grazed in the uplands around the settlements (sheep bones are also fairly common among the bone samples).[4]: 91

Woodland resources would have been abundant due to the more extensive forest cover.[4]: 92 Red deer are attested from small amounts at Monte Ingino; roe deer are attested in small amounts at both Monte Ingino and Monte Asciano. Nuts and berries could have been foraged from the woodlands, as well as smaller game, and freshwater fish could be caught either in the perennial mountain stream between Monte Ingino and Monte Foce, or in the bigger streams (Saonda and Assino) down in the valley. Firewood would have been collected in these woodlands and brought back up to the sites in the hills, and flint would have been obtained from cobbles in the stream beds. Water supplies were probably derived either from the natural springs in the hills or from the seasonal streams between the hills.[4]: 92 [4]

Iron Age

[edit]Monte Asciano remained inhabited in the early Iron Age (1200–1000 BCE),[3] and the sites of Vescovado and Sant'Agostino primarily date from this period as well.[4]: 90

Ancient

[edit]Archaic period

[edit]By the Archaic period, the main area of settlement had shifted to the lower slopes of Monte Asciano, including Sant'Agostino. Monte Ascoli itself was used as a religious sanctuary during this period. Finds from this period include a drystone platform, dozens of bronze figurines dated to between the 5th and 3rd centuries BCE, and an aes rude probably dating from the 3rd century BCE.[3]

Umbrian period

[edit]As Ikuvium, it was an important town of the Umbri in pre-Roman times, made famous for the discovery there in 1444 of the Iguvine Tablets,[6] a set of bronze tablets that together constitute the largest surviving text in the Umbrian language.

According to Dorica Manconi, pre-Roman Ikuvium was located in a "well-defined" area in the vicinity of the present-day city.[7][3] It was "bounded by the cemeteries (S. Benedetto, Via Eraclito, etc.), between the river Camignano, the continuation of Via dei Consoli, Viale Parruccini and the wall so-called "del vallo", extending over about 34 hectares (84 acres) and surrounded by a huge area of land to be used for agriculture and stock-farming".[7] This is supported by a high number of archaeological finds in the area, including a vernice nera kiln possibly from the 3rd or 2nd century BCE as well as a necropolis at San Biagio. A number of smaller rural settlements also existed throughout the valley, dependent on the main town; the two best-known archaeologically were at Mocaiana and Casa Regni.[3]

Gubbio is one of only two Umbrian towns known to have minted its own coins before the Roman conquest (the other was Todi).[7]

Roman period

[edit]After the Roman conquest in the 2nd century BC – it kept its name as Iguvium – the city remained important, as attested by its Roman theatre, the second-largest surviving in the world.[citation needed]

Originally, Gubbio held strategic importance as controlling a major highway through the mountains. However, when the Via Flaminia was constructed c. 223 BCE, it bypassed Gubbio by several miles to the east. This caused Gubbio to lose much of its significance, and it declined gradually throughout the Imperial period.[8]

After the Social War, the people of Gubbio were enrolled in the Roman tribe Clustumina.[8]

The date of Gubbio's theatre is unknown, although its size, its layout, and the rustication on the exterior suggest that it was built during or after the reign of Claudius. The remains of a large structure nearby may represent a mill of some sort.[8] The Roman temple of the Guastaglia, within present-day Gubbio, has had its foundations excavated, and an inscription originally in the theatre (now in the Palazzo dei Consoli) records that the quattuorvir Gnaeus Satrius Rufus financed the restoration of the theatre and of a temple of Diana at Gubbio in the 1st century CE.[3]

A funerary inscription records one Vittorius Rufus as "avispex extispicus sacerdos publicus et privatus" — that is, someone who interpreted bird flight and entrails, as well as managed public and private rituals — and another lists a Sestus Vetiarius Surus with a similar title. This is unusual because this profession was not very common in the Roman world, but it had been important among the Umbri and Etruscans (and featured prominently in the Iguvine tablets), suggesting that these religious practices continued locally. In the Imperial period, the cults of Isis and her son Harpocrates were also imported from Egypt.[3]

Middle Ages

[edit]11th–13th centuries

[edit]Gubbio became very powerful at the beginning of the Middle Ages. The town sent 1000 knights to fight in the First Crusade under the lead of Girolamo of the prominent Gabrielli family, who, according to an undocumented local tradition, were the first to reach the Church of the Holy Sepulchre when Jerusalem was seized (1099).[citation needed]

In terms of vegetation and land use, data is largely not available until the early medieval period. In the 11th century, cultivation was limited to the land immediately around the city and around the curtis of the individual feudal castles. Toward the beginning of the 11th century, "the combination of demographic growth and the declining control by feudal lords over their land" led to a more favorable contract for peasants such as enfiteusi. As a result, woodland was cleared to make room for farmland, pastures were converted to farmland, and uncultivated areas were also put to more intensive agriculture. This agriculture included cereal crops, vines, olives, and fruit trees. Mixed cultivation, such as wheat interspersed with rows of vines, was introduced and especially well suited for hilly areas. Watermills had been introduced by this point (at least) and were an important part of the rural economy.[4]: 43

The following centuries in Gubbio were turbulent, featuring wars against the neighbouring towns of Umbria. One of these wars saw the miraculous intervention of its bishop, Ubald, who secured Gubbio an overwhelming victory (1151) and a period of prosperity. In the struggles of Guelphs and Ghibellines, the Gabrielli, such as the condottiero Cante dei Gabrielli (c. 1260–1335), fought for the Guelph faction, supporting the papacy. As Podestà of Florence, Cante exiled Dante Alighieri, ensuring his own lasting notoriety.[citation needed]

In the 13th century (1200s), there was "further economic expansion"; Gubbio had to expand its city walls and construct new buildings to accommodate a growing population. This was accompanied by opening up more land for agriculture, especially in hilly areas, and even the upper hills. Documents from this period mention place names suggesting woodlands (Cerqueto, Monte Acera, Colle Cerrone, Cerquattino, Sterpeto) indicate the expansion of farmland during this period.[4]: 43

14th–15th centuries

[edit]In the early 1300s, there was a major population increase; in addition to vines, olives, and fruit trees, new crops were introduced: flax and hemp. Landlords were now based in the city, and peasants had greater autonomy over the land; at the same time, the population growth meant that they had to expand cultivation into increasingly poor soil areas in order to support the larger urban population. Then the plague happened in 1348, killing almost half the population. Cultivation significantly decreased, and woodlands regrew. The rural economy shifted more toward animal husbandry, and farmland was turned into pasture. These trends continued into the early 1400s.[4]: 44

In 1350 Giovanni Gabrielli, count of Borgovalle seized power as the lord of Gubbio. His rule was short, and he was forced to hand over the town to Cardinal Gil Álvarez Carrillo de Albornoz, representing the Papal states (1354).

A few years later, Gabriello Gabrielli, the bishop of Gubbio, also proclaimed himself lord of Gubbio (Signor d'Agobbio). Betrayed by a group of noblemen which included many of his relatives, the bishop was forced to leave the town and seek refuge at his home castle at Cantiano.[citation needed]

In the 1400s, there was a major economic revival of the city of Gubbio, and accordingly the demand for grain and other agricultural produce increased. Again, land was cleared for cultivation, and peasants were encouraged to do so by the Comune: at one point, peasants were given an extremely favorable contract: a peasant who cleared more than three mine in a single year was granted ownership of that land as well as its harvest. The Comune issued an edict in 1422 stipulating that all landowners must have their lands sown with "good grain" or face a large fine in the Camera Comunale. These indicate how strong the demand was for grain. Also, flax and hemp were cultivated, indicating the commercial demand from the city. By the end of the 1400s, so much land had been turned over to farmland that shepherds's complaints are recorded saying that they could no longer find suitable pastureland and had to take their flocks into the Marche.[4]: 44

With the decline of the political prestige of the Gabrielli, Gubbio was thereafter incorporated into the territories of the House of Montefeltro. The lord of Urbino, Federico da Montefeltro rebuilt the ancient Palazzo Ducale in Gubbio, incorporating in it a studiolo veneered with intarsia like his studiolo at Urbino.[9]

Early modern period

[edit]16th–17th centuries

[edit]The maiolica industry at Gubbio reached its apogee in the first half of the 16th century, with metallic lustre glazes imitating gold and copper.[citation needed]

There was significant deforestation around the 16th century, both in the uplands and lowlands, and some of the steep slopes that today only support "limited scrub and woodland cover" may have had more significant forests before the 1500s, supported by thicker soils that have since been eroded away. Also, especially since the 16th century, ditches and levees have been constructed to control water flow, significantly altering the drainage patterns in the valley.[4]: 90–1

Gubbio became part of the Papal States in 1631, when the della Rovere family, to whom the Duchy of Urbino had been granted, was extinguished. In 1860 Gubbio was incorporated into the Kingdom of Italy along with the rest of the Papal States.[citation needed]

The name of the Pamphili family, a great papal family, originated in Gubbio then went to Rome under the pontificate of Pope Innocent VIII (1484–1492), and is immortalized by Diego Velázquez and his portrait of Pope Innocent X.[citation needed]

Geography

[edit]

Gubbio is located in an upland valley in the Apennine Mountains, in the northeastern part of the present-day region of Umbria. This particular part of Umbria is a transitional area, close to both Marche to the east and Tuscany to the west. As a result, Gubbio has historically had strong political and cultural ties to both of those regions.[3]

The Gubbio valley itself is arranged on a northwest-to-southeast axis. A steep limestone escarpment bounds the basin to the northeast. Unusually, streams flow through the Gubbio valley in two opposite directions, although both streams ultimately flow to the Tiber.[3] These two streams are the Assino and the Chiascio. Two smaller streams, both called Saonda, run along the western side of the basin; one is a tributary of the Assino and the other is a tributary of the Chiascio. There is no clear watershed between the two Saondas, which may explain why they have the same name.[4]: 19–20

The municipality borders Cagli (PU), Cantiano (PU), Costacciaro, Fossato di Vico, Gualdo Tadino, Perugia, Pietralunga, Scheggia e Pascelupo, Sigillo, Umbertide and Valfabbrica.[10]

Geology

[edit]The Gubbio Basin is a graben filled with river and lake sediments. Drainage is to the northwest and southwest; the rest is mostly surrounded by "marly-arenaceous formations on the hills", while to the north is a steep escarpment. The surrounding mountains are primarily limestone and marl.[4]: 18, 28 Sediment runoff from the escarpment created several alluvial fans below it, resulting in the central part of the valley being higher. This is the reason behind the unusual opposite-flowing streams in the valley.[3]

The origins lie during the Pleistocene, when tectonic activity simultaneously caused the basin to sink and the mountains to rise. There was once a lake in the basin. In the early Holocene, the lake disappeared and a stream system emerged.[4]: 28

Frazioni

[edit]The frazioni (territorial subdivisions) of the comune of Gubbio are the villages of: Belvedere, Bevelle, Biscina, Branca, Burano, Camporeggiano, Carbonesca, Casamorcia-Raggio, Cipolleto, Colonnata, Colpalombo, Ferratelle, Loreto, Magrano, Mocaiana, Monteleto, Monteluiano, Nogna, Padule, Petroia, Ponte d'Assi, Raggio, San Benedetto Vecchio, San Marco, San Martino in Colle, Santa Cristina, Scritto, Semonte, Spada, Torre Calzolari and Villa Magna.

Monuments and sites of interest

[edit]

The historical centre of Gubbio has a decidedly medieval aspect: the town is austere in appearance because of the dark grey stone, narrow streets, and Gothic architecture. Many houses in central Gubbio date to the 14th and 15th centuries, and were originally the dwellings of wealthy merchants. They often have a second door fronting on the street, usually just a few centimetres from the main entrance. This secondary entrance is narrower, and 30 centimetres (1 ft) or so above the actual street level. This type of door is called a porta dei morti (door of the dead) because it was proposed that they were used to remove the bodies of any who might have died inside the house. This is almost certainly false, but there is no agreement as to the purpose of the secondary doors. A more likely theory is that the door was used by the owners to protect themselves when opening to unknown persons, leaving them in a dominating position.

Religious architecture or sites

[edit]- Duomo: This cathedral was built in the late 12th century. The most striking feature is the rose-window in the façade with, at its sides, the symbols of the Evangelists: the eagle for John the Evangelist, the lion for Mark the Evangelist, the angel for Matthew the Apostle and the ox for Luke the Evangelist. The interior has a latine cross plan with a single nave. The most precious art piece is the wooden Christ over the altar, of the Umbrian school.

- San Francesco: This church from the second half of the 13th century is the sole religious edifice in the city having a nave with two aisles. The vaults are supported by octagonal pilasters. The frescoes on the left side date from the 15th century.

- Santa Maria Nuova: This is a typical Cistercian church of the 13th century. In the interior is a 14th-century fresco portraying the so-called Madonna del Belvedere (1413), by Ottaviano Nelli. It also has a work by Guido Palmeruccio. Also from the Cistercians is the Convent of St. Augustine, with some frescoes by Nelli.

- Basilica of Sant'Ubaldo, with a nave and four aisles is a sanctuary outside the city. Noteworthy are the marble altar and the great windows with episodes of the life of Ubald, patron of Gubbio. The finely sculpted portals and the fragmentary frescoes give a hint of the magnificent 15th-century decoration once boasted by the basilica.

- San Giovanni Battista, Gubbio: 13th-century church with one nave only with four transversal arches supporting the pitched roof, a model for later Gubbio churches.

- San Domenico, once known as San Martino

- Sant'Agostino

- Santa Croce della Foce

Secular architecture or sites

[edit]- Roman Theatre: This ancient open-air theater built in the 1st century BC using square blocks of local limestone. Traces of mosaic decoration have been found. Originally, the diameter of the cavea was 70 metres (230 ft) and could house up to 6,000 spectators.

- Roman Mausoleum: This Mausoleum is sometimes said to be of Gaius Pomponius Graecinus, but on no satisfactory grounds.

- Palazzo dei Consoli: Dating to the first half of the 14th century, this massive palace, is now a museum housing the Iguvine Tablets.

- Palazzo and Torre Gabrielli

- Palazzo Ducale: The Palace built from 1470 by Luciano Laurana or Francesco di Giorgio Martini for Federico da Montefeltro. Famous is the inner court, reminiscent of the Palazzo Ducale, Urbino.

- Museo Cante Gabrielli: This museum is housed in the Palazzo del Capitano del Popolo, which once belonged to the Gabrielli family.

- Vivian Gabriel Oriental Collection: This is a museum of Tibetan, Nepalese, Chinese and Indian art. The collection was donated to the municipality by Edmund Vivian Gabriel (1875–1950), British colonial officer and adventurer, a collateral descendant of the Gabrielli who were lords of Gubbio in the Middle Ages.

Culture

[edit]

Gubbio is home to the Corsa dei Ceri, a run held every year always on Saint Ubaldo Day, the 15th day of May, in which three teams, devoted to Ubald, Saint George and Saint Anthony the Great run through throngs of cheering supporters clad in the distinctive colours of yellow, blue and black, with white trousers and red belts and neckbands, up much of the mountain from the main square in front of the Palazzo dei Consoli to the basilica of St. Ubaldo, each team carrying a statue of their saint mounted on a wooden octagonal prism, similar to an hour-glass shape 4 metres (13 ft) tall and weighing about 280 kg (617 lb).

The race has strong devotional, civic, and historical overtones and is one of the best-known folklore manifestations in Italy; the Ceri was chosen as the heraldic emblem on the coat of arms of Umbria as a modern administrative region.

A celebration like the Corsa dei Ceri is held also in Jessup, Pennsylvania. In this small town the people carry out the same festivities as the residents of Gubbio do by "racing" the three statues through the streets during the Memorial Day weekend. This remains an important and sacred event in both towns.

Gubbio was also one of the centres of production of the Italian pottery (maiolica), during the Renaissance. The most important Italian potter of that period, Giorgio Andreoli, was active in Gubbio during the early 16th century.

The town's most famous story is that of "The Wolf of Gubbio"; a man-eating wolf that was tamed by St. Francis of Assisi and who then became a docile resident of the city. The legend is related to the 14th-century Little Flowers of St. Francis.

The Gubbio Layer

[edit]Gubbio is also known among geologists and palaeontologists as the discovery place of what was at first called the "Gubbio layer", a sedimentary layer enriched in iridium that was exposed by a roadcut outside of town. This thin, dark band of sediment marks the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary, also known as the K–T boundary or K–Pg boundary, between the Cretaceous and Paleogene geological periods about 66 million years ago, and was formed by infalling debris from the gigantic meteor impact probably responsible for the mass extinction of the dinosaurs. Its iridium, a heavy metal rare on Earth's surface, is plentiful in extraterrestrial material such as comets and asteroids. It also contains small globules of glassy material called tektites, formed in the initial impact. Discovered at Gubbio, the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary is also visible at many places all over the world. The characteristics of this boundary layer support the theory that a devastating meteorite impact, with accompanying ecological and climatic disturbance, was directly responsible for the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event.

Gubbio in fiction

[edit]In Hermann Hesse's novel Steppenwolf (1927) the isolated and tormented protagonist – a namesake of the wolf – consoles himself at one point by recalling a scene that the author might have beheld during his travels: "(...) that slender cypress on the hill over Gubbio that, though split and riven by a fall of stone, yet held fast to life and put forth with its last resources a new sparse tuft at the top".[11]

The town is a backdrop in Antal Szerb's novel Journey by Moonlight (1937) as well as Danièle Sallenave's Les Portes de Gubbio (1980).

The TV series Don Matteo, where the title character ministers to his parish while solving crimes, was shot on location in Gubbio between 2000 and 2011.

The 2024 novel What We Buried by Robert Rotenberg takes place in Canada and Gubbio. In particular, the novel involves the 40 "Martyrs of Gubbio", civilians seized from their homes by German soldiers late in WW2 and shot, in reprisal for the shooting of a German officer by partisans.

Other

[edit]Anna Moroni, a popular cook on the Italian daytime TV series La Prova del Cuoco, discusses Gubbio in many of her TV segments. She often cooks dishes from the region on TV, and she featured Gubbio in her first book.

Sport

[edit]A.S. Gubbio 1910 football club play in Serie C at the Pietro Barbetti Stadium.

Transportation

[edit]The city is served by Fossato di Vico–Gubbio railway station located in Fossato di Vico; until 1945 it also operated the Central Apennine railway (Ferrovia Appenino Centrale abbreviation FAC) with a narrow gauge which departed from Arezzo and reached as far as Fossato di Vico and in Gubbio had his own railway station located in via Beniamino Ubaldi 2, now completely demolished.

Twin towns – Sister cities

[edit]Gubbio is twinned with:

|

Notable people

[edit]- Giosuè Fioriti (born 1989), Italian footballer

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Superficie di Comuni Province e Regioni italiane al 9 ottobre 2011". Italian National Institute of Statistics. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ Population data from Istat

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Negro, Marianna; Whitehead, Nicholas; Malone, Caroline; Stoddart, Simon (2024). "Revisiting Gubbio: Settlement Patterns and Ritual from the Middle Palaeolithic to the Roman Era". Land. 13 (9): 1369. Bibcode:2024Land...13.1369N. doi:10.3390/land13091369.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Malone, Caroline; Stoddart, Simon, eds. (1994). Territory, Time and State: The Archaeological Development of the Gubbio Basin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-35568-0. Retrieved 30 January 2025.

- ^ a b c d e Stoddart, Simon (2020). Power and Place in Etruria: The Spatial Dynamics of a Mediterranean Civilization, 1200–500 BC. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-38075-1. Retrieved 31 January 2025.

- ^ Poultney, J. W. Bronze Tables of Iguvium 1959

- ^ a b c Manconi, Dorica (2018). "The Umbri". In Farney, Gary D.; Bradley, Guy (eds.). The Peoples of Ancient Italy. Boston/Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-1-61451-520-3. Retrieved 11 February 2025.

- ^ a b c Richardson Jr., L. (1976). "Iguvium". In Stillwell, Richard; MacDonald, William L.; Holland, Marian (eds.). The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Retrieved 11 February 2025.

- ^ The Studiolo from the Ducal Palace in Gubbio is reassembled in its entirety at the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Federico's father, Guidobaldo da Montefeltro, and his daughter Agnese di Montefeltro were born in Gubbio.

- ^ 42390 Gubbio on OpenStreetMap

- ^ Herman Hesse, Steppenwolf, chapter 1. ("For Madmen Only")

External links

[edit]Gubbio

View on GrokipediaHistory

Prehistory and Early Settlements

The Gubbio basin exhibits traces of intermittent human presence from the Middle Palaeolithic period (approximately 210,000–35,000 years ago), primarily in the form of lithic artifacts concentrated on relict fluvial terraces near Ponte d’Assi, suggesting opportunistic exploitation of valley resources by mobile hunter-gatherer groups.[6] Upper Palaeolithic (35,000–10,000 years ago) and Late Palaeolithic (10,000–6,000 years ago) evidence shifts to alluvial fans, with broader artifact scatters indicating gradual adaptation to post-glacial environmental changes, though no permanent structures have been identified.[6] The transition to the Neolithic (6,000–3,000 BC) introduced more sedentary patterns, as seen at the San Marco site south of the modern town, where surveys and excavations from 1985–1988 recovered impressed ware pottery, obsidian and flint lithics, and paleobotanical remains consistent with early agriculture and herding economies reliant on cereals and domesticated animals.[7][6] Chalcolithic occupation (3,500–2,300 BC) remains limited, with sparse ceramic finds suggesting continuity but low population density.[6] Bronze Age settlements (c. 1400–1200 BC) intensified on hilltops like Monte Ingino, yielding over 30,000 pottery fragments, more than 25,000 faunal bones from sheep, goats, and cattle, and a nearby cremation cemetery along Via dei Consoli, evidencing organized communities with metallurgical activity and ritual disposal practices.[6] Iron Age developments (c. 1200–1000 BC) at sites such as Monte Ansciano included enclosure walls, potential sanctuary features, and 12,000 faunal remains, reflecting proto-urban nucleation and religious continuity that underpinned the emergence of the Umbrian center Iguvium by the late Iron Age, as corroborated by later coinage and epigraphic evidence of pre-Roman significance.[6][8]Ancient and Roman Periods

Gubbio, known in antiquity as Ikuvium to the Umbrians, served as a significant settlement and likely the capital of the Umbri, an Italic people inhabiting central Italy prior to Roman dominance.[9] Archaeological evidence indicates continuous occupation on the hills of Mount Ingino from the pre-Roman era, positioning Ikuvium as a major religious center for the Umbrians, whose territory extended into areas now part of the Marches and Romagna.[10][11] The Iguvine Tablets, seven bronze inscriptions discovered near the Roman theater in the 15th century, provide the primary textual evidence of Umbrian culture, language, and religion, dating from approximately 200 BCE to the early 1st century BCE.[12] These tablets, the longest surviving document in any pre-Roman Italic language, detail ritual prescriptions and priestly duties, offering insights into pre-Roman Italic religious practices through their Umbrian script and content.[13] By the 4th century BCE, Ikuvium, renamed Iguvium under Roman influence, aligned with Rome, forging an alliance that persisted into the 3rd century BCE.[14] Following the Social War, Iguvium received full Roman citizenship in 89 BCE, integrating it firmly into the Roman municipal system.[15] During the Roman period, Iguvium flourished as a prosperous municipality, evidenced by urban development and infrastructure that remained in use through at least the 4th century CE.[16] Key Roman monuments include the theater, constructed in the late Republican era around 40 BCE, which exemplifies the city's adoption of Roman architectural and cultural elements.[17]Medieval Expansion and Conflicts

In the 11th century, Gubbio emerged as a prominent free commune in central Italy, leveraging its strategic position in the Apennines to expand territorial influence and economic reach through control of nearby castles and trade routes.[18] The city's military prowess was demonstrated in 1099 when it dispatched 1,000 knights under the command of Girolamo Gabrielli to participate in the First Crusade, signaling its capacity for large-scale mobilization and alliance with broader Christian endeavors.[18] This period marked initial expansion, including the acquisition of Cagli in 1199 and Castello di Certaltro in 1203, which bolstered Gubbio's regional dominance amid the competitive landscape of Umbrian communes.[18] A pivotal conflict arose in 1151 when Gubbio, led by Bishop Ubaldo Baldassini (serving 1128–1160), repelled a coalition of eleven neighboring cities spearheaded by rival Perugia, achieving a decisive victory that enhanced its prestige and earned imperial recognitions from figures including Frederick Barbarossa.[5][19] This triumph, attributed in local tradition to Ubaldo's intercession, temporarily curbed Perugian ambitions and solidified Gubbio's autonomy, though it submitted briefly to Perugia in 1183 before reclaiming independence.[18] Renewed hostilities erupted in 1216–1217 over contested fortresses such as Rocca Flea, culminating in Gubbio's defeat and the renunciation of several border strongholds, which constrained further territorial gains.[18] Gubbio aligned firmly with the Guelph faction, supporting papal authority against imperial claims, as affirmed by Pope Urban IV in 1263 through confirmed privileges and alliances like that with Charles d’Anjou.[18] Internal and external strife intensified in the early 14th century; Ghibellines seized the city in 1300, but Guelph forces, aided by Perugia and led by Cante de’ Gabrielli, restored control.[18] In 1310, Gubbio backed Perugia against Ghibelline-held Spoleto, perpetuating factional rivalries that drained resources without net expansion.[18] By 1354, Cardinal Gil Álbornoz imposed direct papal rule, eroding communal independence and shifting Gubbio toward subordination under the Duchy of Urbino in 1384, marking the eclipse of its medieval assertive phase.[18][5]Early Modern to Contemporary Era

In the early modern period, Gubbio transitioned from medieval autonomy to feudal oversight under the Dukes of Urbino, beginning with the Montefeltro family from 1384 to 1508 and continuing under the Della Rovere until 1631, during which the town experienced relative stability but diminished political independence.[5] Following the extinction of the Della Rovere line, Gubbio was incorporated into the Papal States in 1631, where it remained under ecclesiastical administration, marked by administrative centralization from Rome and a gradual economic shift toward agriculture and local crafts amid broader regional decline.[20] The Renaissance era saw a notable flourishing in ceramics, particularly maiolica production, with artisans like Giorgio Andreoli innovating lusterware techniques in the early 16th century, establishing Gubbio as a center for high-quality pottery exported across Europe.[14] The Napoleonic Wars briefly disrupted Papal control, as Gubbio was annexed to the Cisalpine Republic in 1798 and then the Roman Republic from 1798 to 1799, introducing secular reforms before restoration under the Papacy.[5] In the 19th century, the town endured as part of the Papal States until Italy's unification in 1861, after which it integrated into the Kingdom of Italy as part of the province of Perugia in Umbria, prompting a revival of traditional crafts like ceramics and textiles that had waned under prior stagnation.[14] [21] The 20th century brought wartime devastation during World War II, when on June 21, 1944, German forces executed 40 male civilians—ranging in age from 19 to 78—in retaliation for partisan attacks, an event commemorated annually at the Mausoleo dei Quaranta Martiri built in their honor.[22] Post-war reconstruction focused on infrastructure and heritage preservation, with Gubbio benefiting from Italy's economic miracle through mid-century industrialization in nearby areas and a pivot toward tourism leveraging its medieval core.[5] In the contemporary era, Gubbio has maintained political stability within the Italian Republic, emphasizing cultural continuity through events like the Corsa dei Ceri, a May 15 festival originating in medieval times but actively preserved as a UNESCO-recognized intangible heritage practice involving teams racing massive wooden candelabras up Mount Ingino in honor of patron saints.[14] Economic growth has centered on tourism, drawing over 200,000 visitors annually by the 2010s for its historic sites and festivals such as the Gubbio Summer Festival in July-August, while local governance has prioritized seismic retrofitting following Umbria's 1997 earthquakes to safeguard the town's dense medieval fabric.[23] ![Gubbio Corsa dei Ceri festival participants racing candelabras][float-right]Geography

Location, Terrain, and Geology

Gubbio is situated in the northeastern portion of the Province of Perugia, within the Umbria region of central Italy, at geographic coordinates 43°21′13″N 12°34′25″E.[24] The town lies approximately 47 kilometers northeast of Perugia and 220 kilometers north of Rome, positioned along the lowest slopes of Monte Ingino in the Apennine foothills.[25] Its average elevation reaches 576 meters above sea level, reflecting its placement in a structurally controlled basin amid the regional topography.[26] The terrain surrounding Gubbio consists of rugged, hilly landscapes characteristic of the Umbrian Apennines, with steep slopes ascending to peaks exceeding 800 meters on Monte Ingino and adjacent ridges.[27] The area features a combination of incised valleys, such as the nearby Bottaccione Gorge with its vertical limestone walls, and broader intermontane basins shaped by tectonic activity.[28] These landforms support dense forests, agricultural terraces, and sparse plateaus, contributing to the town's isolation and scenic isolation within the Tiber River valley system.[29] Geologically, Gubbio occupies the Umbria-Marche pelagic basin domain of the Northern Apennines, underlain by thick sequences of Mesozoic to Cenozoic marine sedimentary rocks, predominantly micritic limestones and marly limestones formed in deep-water environments from the Middle Jurassic through the Eocene.[30] The Bottaccione Gorge, incised north of the town between Monte Ingino and Monte Foce, exposes a continuous stratigraphic record including the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary, marked by an iridium-enriched clay layer linked to the Chicxulub asteroid impact 66 million years ago.[27][30] Extensional tectonics dominate the modern structure, with the 22-kilometer-long Gubbio normal fault delineating the southern basin margin and accommodating Quaternary subsidence.[31] These features, including karstic limestone formations derived from ancient marine microfossils, underscore the region's role as a key site for stratigraphic and paleontological research.[25]Climate and Environment

Gubbio features a temperate oceanic climate classified as Cfb under the Köppen-Geiger system, marked by cool summers, cold winters, and relatively even precipitation throughout the year, due to its inland location at an elevation of 522 meters amid the Umbrian Apennines. Average annual temperatures hover around 11.6°C, with July highs reaching approximately 27°C and January lows dipping to -1°C or below, occasionally experiencing frost and snowfall. Precipitation totals about 934 mm annually, peaking in November at around 103 mm, while July is the driest month with roughly 40 mm.[32][33] The local environment is shaped by rugged terrain, including steep slopes on Monte Ingino and proximity to the Monte Cucco Regional Park, which encompasses karst landscapes, caves, and dense mixed forests of beech, oak, and other deciduous trees covering much of the surrounding hills. This park, spanning northeastern Umbria, supports diverse ecosystems with varied flora below 1,000 meters, including aromatic plants and extensive woodlands that aid in biodiversity conservation. Fauna includes species like beetles (e.g., abundant Cetonia aurata in urban-periurban zones) and supports multifunctional coppice management practices typical of Umbrian forests.[34][35] Environmental efforts in the area align with regional Natura 2000 sites, emphasizing habitat restoration and sustainable forestry, though infrastructural barriers like roads pose fragmentation risks to connectivity. No major recent ecological crises are reported, but the hilly geology contributes to seismic activity, as Gubbio lies in a moderate-risk zone influenced by Apennine tectonics.[36][37][38]| Month | Avg High (°C) | Avg Low (°C) | Precipitation (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| January | 7.1 | 1.8 | 70 |

| February | 8.5 | 2.2 | 70 |

| March | 12.0 | 4.0 | 70 |

| April | 15.5 | 7.0 | 80 |

| May | 20.0 | 11.0 | 80 |

| June | 24.0 | 14.5 | 60 |

| July | 27.5 | 16.5 | 40 |

| August | 27.0 | 16.0 | 60 |

| September | 23.5 | 13.5 | 80 |

| October | 18.5 | 10.0 | 90 |

| November | 12.0 | 6.0 | 103 |

| December | 8.5 | 3.0 | 80 |

Frazioni and Surrounding Areas

The comune of Gubbio spans 525.77 km², encompassing 64 frazioni and over 80 smaller localities dispersed across valleys, hills, and Apennine foothills, making it the largest municipality in Umbria by area.[40] [41] These settlements range from rural hamlets focused on agriculture to semi-urban zones with residential and light industrial development, supporting the main town's economy through commuting and local production.[42] Key frazioni include Branca, a major suburban area in the Chiascio valley approximately 7 km northwest of central Gubbio, known for its residential expansion and industrial facilities; Padule, a rural hamlet with historical structures such as Castel d'Alfiolo and the Church of Santa Maria; and Semonte, elevated in the Serra di Burano with scattered farmsteads.[42] [43] Other significant localities encompass Camporeggiano, Colpalombo, Mocaiana, and Carbonesca, often featuring traditional stone-built clusters amid olive groves and woodlands.[42] [44] Surrounding areas border eight neighboring communes, including Gualdo Tadino to the west, Perugia to the southwest, and Marche-region municipalities like Cantiano and Fossato di Vico to the northeast, integrating Gubbio's territory into a transitional zone between Umbrian plains and the central Apennines.[45] This peripheral landscape supports forestry, truffle harvesting, and hiking trails, with natural boundaries defined by ridges like Monte Ingino (8 km east) and the Candigliano river basin.[43]Administration and Society

Government and Administrative Structure

Gubbio operates as a comune, the fundamental local administrative entity in Italy, nested within the Province of Perugia and the Umbria region, exercising delegated powers in areas such as urban planning, public services, and local taxation.[46] The executive branch is led by the sindaco (mayor), elected directly by residents for a five-year term, who appoints the giunta comunale (municipal executive board) comprising assessors responsible for specific portfolios like finance, culture, and infrastructure. The current mayor, Filippo Mario Stirati, has held office since at least 2014, overseeing operations from the municipal headquarters in Piazza Grande.[47] [48] Legislative authority resides with the Consiglio Comunale (City Council), a publicly elected body that approves budgets, bylaws, and strategic plans while monitoring executive actions; councilors are chosen concurrently with the mayor via proportional representation, ensuring representation of multiple political lists.[46] As of the most recent composition, the council features groups such as Gubbio Civica (7 members, aligned with the mayor's coalition), Città Futura (4 members), Liberi e Democratici (2 members), Fratelli d’Italia (2 members), and Forza Italia (2 members), alongside smaller lists like Gubbio Democratica and Rinascimento Eugubino.[49] This structure reflects Italy's post-1993 municipal reforms, emphasizing direct democracy and accountability at the local level.[49] The bureaucratic framework follows a departmental model, with sectors (settori) managing daily operations including administrative services, environmental protection, and economic development, as detailed in the organigramma approved via Deliberazione di Giunta Comunale (DGC) n. 57 on April 22, 2020, and updated through DGC n. 118 on July 29, 2020.[50] These units report to the giunta and support delegated regional and national functions, such as civil registry and waste management, under oversight from the mayor's office to ensure fiscal transparency and service delivery to approximately 32,000 residents.[50]Demographics and Population Trends

As of 2023, Gubbio's resident population stood at 30,388, distributed across 13,061 families in a municipal area of approximately 526 square kilometers, yielding a low population density of about 58 inhabitants per square kilometer.[1] [51] The gender composition shows a slight female majority, with 51.3% females and 48.7% males, while the average age of residents is 48.1 years, reflecting an aging demographic typical of rural Italian communes.[1] Foreign residents constitute 6.2% of the population, lower than the national average of around 10%, with immigration primarily from Eastern Europe, North Africa, and Asia providing modest demographic replenishment.[1] Population trends indicate gradual decline in recent years, with an average annual variation of -0.87% from 2018 to 2023, driven by a low birth rate of 5.5 per 1,000 inhabitants and a higher death rate of 13.1 per 1,000, resulting in a negative natural balance partially offset by net migration of +3.4 per 1,000.[52] [1] Projections estimate the population at 30,297 by 2025, continuing this downward trajectory amid broader Italian patterns of depopulation in inland, non-metropolitan areas due to out-migration of younger residents to urban centers for employment and low fertility rates below replacement levels.[51] Historically, Gubbio's population grew modestly by 4.2% from 1975 to 2015, stabilizing around 32,000 before the onset of accelerated aging and emigration pressures in the 21st century.[53]Economy

Historical Industries and Crafts

Gubbio's medieval economy featured organized guilds, known as the "Università delle Arti e Mestieri," which regulated crafts and trades from the Middle Ages onward, ensuring quality and apprenticeships in pottery, wool processing, and metalwork.[54] These guilds maintained continuity, with the potters' guild incorporating influences from nearby centers like Pesaro and Deruta by the 15th century.[55] Pottery production, particularly maiolica, emerged as a dominant craft in the 14th century, with early examples featuring wheel-turned household objects glazed in copper green or manganese brown over tin, decorated with geometric, floral, or zoomorphic motifs.[56] The technique advanced in the late 15th century under Mastro Giorgio Andreoli, who established a workshop around 1480 and pioneered lustreware, applying metallic finishes in gold, silver, green, and notably ruby red by approximately 1530, achieving international renown for historiated pieces with mythological and religious scenes.[56] [55] This innovation, including raised low-foot designs and embossed goblets like the "coppa abborchiata" from 1530, elevated Gubbio's ceramics within the Urbino Duchy, though the lustre secret faded after Andreoli's lineage.[57] Wool processing supported a significant guild activity, evidenced by the Logge dei Tiratori della Lana, medieval structures used for drying and stretching dyed woolen cloths by the woolworkers' guild (Arte della Lana).[58] This craft, tied to broader Umbrian textile traditions dating to the 12th century, involved dyeing and weaving, contributing to Gubbio's pre-industrial economy alongside ancillary pursuits like embroidery and wrought ironwork.[59] Revivals in the 19th century, such as Angelo Fabbri's rediscovery of metallic glazing, sustained pottery alongside these traditions into modern times.[55]Contemporary Economy and Tourism Impact

Gubbio's contemporary economy centers on manufacturing, with cement production as the primary industrial sector, complemented by traditional ceramics craftsmanship and services including tourism.[60] Ceramics, particularly maiolica, remain a notable artisanal activity, though scaled down from historical peaks, supporting local workshops and exports.[61] Tourism contributes significantly to the service sector, driven by the town's medieval heritage, Roman theater, and events like the Corsa dei Ceri festival. In 2024, the Gubbio territory recorded 143,257 tourist arrivals and 343,021 presences (overnight stays), reflecting a 4% increase in presences from 329,800 in 2023 and a 5% overall rise in arrivals and presences.[62][63] However, these figures position Gubbio as sixth among Umbrian territories for presences, behind leaders like Assisi (over 826,000 presences in the first seven months of 2024), indicating underperformance relative to regional peers.[64] The sector faces constraints, including limited hotel capacity despite rising visitors and disruptions from prolonged construction, which contributed to a decline in Easter 2025 presences compared to 2023.[63][65] Tourism bolsters local commerce, hospitality, and seasonal employment but remains secondary to manufacturing, aligning with Umbria's broader economic structure where industry and agriculture hold substantial weight.[66]Architecture and Monuments

Religious Sites and Structures

The religious landscape of Gubbio is dominated by medieval and Renaissance-era churches tied to local saints and Franciscan traditions, including the legend of Saint Francis taming the wolf of Gubbio in the early 13th century.[67] These structures underscore the town's role as a pilgrimage destination within the Diocese of Gubbio, established in the 5th century.[68] ![Afternoon sunlight streams through the rose window in the Church of San Giovanni.JPG][float-right] Prominent among them is the Basilica di Sant'Ubaldo, perched on Mount Ingino at 900 meters elevation and accessible via a funicular since 1960. Completed in 1527 on 12th-century foundations, it enshrines the incorrupt body of Saint Ubaldo Baldassini, Gubbio's 12th-century bishop and patron saint who died on May 16, 1160, after mediating communal conflicts.[69][70] The basilica's simple Renaissance facade and crypt draw pilgrims annually, especially on May 16 for the saint's feast, when ceri (statues) are carried there during the Corsa dei Ceri festival.[71] The Duomo dei Santi Mariano e Giacomo, Gubbio's cathedral since the 12th century, features a 13th-century Gothic interior with a single nave, ogival arches, and artworks including a polyptych by Allegretto Nuzi from 1360.[72][73] Dedicated to early Christian martyrs, its pink brick exterior and rose window overlook the upper town's historic core, with renovations in the 19th century preserving original frescoes and a 14th-century baptismal font.[68] The Chiesa di San Francesco della Pace, built in the late 13th century in the lower town near Piazza dei Quaranta Martiri, honors Saint Francis and houses 15th-century frescoes by Ottaviano Nelli depicting Franciscan scenes.[74] Adjacent is the smaller Chiesa dei Muratori, linked to the same Franciscan complex.[71] Other notable sites include the Chiesa Collegiata di San Giovanni Battista, a Romanesque-Gothic structure from the 14th century with a prominent rose window and baroque altar, serving as a collegiate church until secularization.[75] The Chiesa di San Marziale, dating to the 14th century, features fresco cycles and ties to local nobility patronage.[75] Scattered Dominican and Augustinian convents, such as San Domenico (13th century), further attest to Gubbio's monastic history amid the Apennine hills.[76]Secular Buildings and Archaeological Remains

The Palazzo dei Consoli, constructed between 1332 and 1349 under the design of Angelo da Orvieto with assistance from Matteo Gattapone, exemplifies Gothic civic architecture in Gubbio, standing 60 meters tall with a prominent bell tower and panoramic loggia overlooking the valley.[77][78] This structure served as a symbol of the town's medieval autonomy and power, housing administrative functions and now the Civic Museum, which includes artifacts from the 1st century BC onward.[79] Adjacent on Via dei Consoli, the Palazzo del Bargello represents another 14th-century Gothic palace, traditionally linked to the residence of the local police magistrate or headquarters of the civic militia, featuring the characteristic Porta dei Morti—a narrow door legendarily used for removing the dead without public processions.[80] The building, preserved across three floors, now accommodates the Museo della Balestra, showcasing medieval weaponry.[81] Archaeological remains in Gubbio highlight its ancient roots as Iguvium. The Roman Theatre, initiated in the 1st century BC and completed between 55 and 20 BC, stands as one of the best-preserved structures from the Roman period, located just outside the medieval city walls with a seating capacity estimated for several thousand spectators.[82] Nearby discoveries include the Iguvine Tablets, seven bronze inscriptions in the ancient Umbrian language unearthed in 1444 in fields adjacent to the theatre, providing key insights into pre-Roman religious and civic practices of the Iguvine people.[83] These tablets, acquired by the comune in the 15th century, are displayed in the Palazzo dei Consoli museum.[11]Culture and Heritage

Traditional Festivals and Customs

The most prominent traditional festival in Gubbio is the Festa dei Ceri, also known as the Corsa dei Ceri, held annually on May 15 to honor the city's patron saint, Ubaldo Baldassini.[84] This event features three teams of ceraioli—devotees of Sant'Ubaldo (in white), San Giorgio (in yellow and blue), and Sant'Antonio (in black)—who carry massive wooden ceri (octagonal structures resembling candles, each weighing about 400 kg and standing 4 meters tall) in a grueling race from the Piazza Grande through the steep streets and up Mount Ingino to the Basilica of Sant'Ubaldo, a distance of approximately 3 km with significant elevation gain.[85] [4] The tradition dates back at least to the 12th century, with legends attributing its origins to Saint Ubaldo's use of similar structures to quell a popular uprising in 1154, though some scholars suggest pre-Christian pagan roots linked to fertility rites for the goddess Ceres.[86] The race culminates without a declared winner among the saints, as the Cero of Sant'Ubaldo traditionally arrives first, symbolizing communal devotion rather than competition, though the event fosters intense rivalry and draws thousands of spectators.[87] Another longstanding custom is the Palio della Balestra, a crossbow tournament reenacting medieval competitions, where participants from Gubbio compete against those from Sansepolcro in shooting at a target from 40 meters.[88] This festival, rooted in Renaissance-era guilds, occurs on the third Sunday of September and emphasizes historical accuracy in attire and weaponry, preserving skills from Gubbio's past as a center of craftsmanship.[88] During the Christmas season, from December 8 to January 6, the San Martino district hosts a life-size nativity scene (presepe vivente), featuring over 120 life-sized statues depicting biblical scenes and medieval daily life along the neighborhood's medieval streets, transforming the area into an immersive representation of 1st-century Palestine adapted to local history.[89] Complementing this, Gubbio illuminates the world's largest Christmas tree outline on the slopes of Mount Ingino each December 7 to January 16, a 650-meter-tall display of 250,000 lights recognized by Guinness World Records since its inception in 1981, blending modern spectacle with seasonal piety.[90] Good Friday features the Processione del Cristo Morto, a solemn procession with the city's confraternities carrying a wooden statue of the Dead Christ through the streets, accompanied by hymns and candles, a rite observed for centuries to commemorate the Passion.[90] These events underscore Gubbio's deep Catholic heritage and communal identity, with participation often generational and tied to neighborhood loyalties.Archaeological Artifacts and Scientific Discoveries

The Iguvine Tablets, discovered in 1444 near the Church of San Pietro in Gubbio, consist of seven bronze panels engraved on both sides with inscriptions in the ancient Umbrian language, dating from the 3rd to 1st centuries BCE.[91] These artifacts detail religious rituals, sacrifices, and protocols of the Atiedian Brethren, a priesthood devoted to Jupiter, providing the longest surviving corpus of pre-Roman Italic texts and invaluable insights into pre-Roman central Italian religious practices and linguistics.[92] The tablets, acquired by the city in 1456, are housed in the Palazzo dei Consoli museum and have been recognized as a foundational epigraphic resource for reconstructing Umbrian society, often likened to a ritual breviary used in public ceremonies.[11] Archaeological excavations around Gubbio have also uncovered prehistoric evidence of human settlement, including Neolithic stone axes, ceramics, and weapons from local caves, indicating occupation since the Paleolithic era.[5] A notable Iron Age find is the 6th-century BCE "Tomba del Carro," a ditch grave containing a chariot burial, unearthed in 1983 and exemplifying early Italic funerary customs.[93] Roman-era artifacts, such as inscriptions and pottery from the ancient municipium of Iguvium, further attest to continuous habitation, though these are secondary to the Tablets' linguistic and ritual primacy. In paleontology and stratigraphy, the Bottaccione Gorge near Gubbio preserves a key exposure of the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) boundary, where geologist Walter Alvarez identified a thin clay layer in the late 1970s marked by an iridium concentration 30 times above normal crustal levels, signaling an extraterrestrial impact.[94] This 1980 discovery, corroborated by foraminiferal extinction patterns across the boundary, provided pivotal evidence for the asteroid impact hypothesis explaining the mass extinction event approximately 66 million years ago, including dinosaur demise.[30] The nearby Contessa section reinforces these findings with similar iridium anomalies and shocked quartz, establishing Gubbio's outcrops as global reference sites for K-Pg studies despite subsequent debates on volcanism's role.[95]Representation in Literature and Media

Gubbio features prominently in medieval hagiographic literature through the legend of Saint Francis of Assisi taming the Wolf of Gubbio, recounted in the Fioretti di San Francesco, a 14th-century compilation of anecdotes about the saint's life. In the narrative, a ferocious wolf terrorized the town's inhabitants by preying on livestock and people until Francis confronted it unarmed in 1220, securing a pact whereby the wolf ceased its attacks in exchange for the villagers feeding it daily; the animal reportedly lived peacefully among them for two more years until its natural death.[96] [97] This tale, emphasizing themes of compassion and reconciliation with nature, has inspired artistic depictions, including Sassetta's 15th-century panel painting San Francesco e il Lupo, which illustrates the encounter.[98] In modern literature, Gubbio appears as a setting in Antal Szerb's 1937 novel Journey by Moonlight, where the protagonist experiences introspective wanderings amid its medieval streets, evoking the town's atmospheric isolation.[99] Luigi Pirandello's 1916 novel Si Gira... (Quaderni di Serafino Gubbio, Operatore Cinematografico) features a protagonist named Serafino Gubbio, a cinematographer whose journals critique the dehumanizing effects of early film technology; while not explicitly set in the town, the surname directly references Gubbio, symbolizing rustic Italian origins amid industrial modernity.[100] The Wolf legend has been adapted into film, notably in Franco Zeffirelli's 1972 biographical drama Brother Sun, Sister Moon, which portrays Francis's life and includes scenes filmed in Gubbio depicting the taming episode to highlight the saint's affinity for animals.[101] Gubbio gained contemporary visibility through the Italian television series Don Matteo (2000–2020), with its initial seasons set in the town, following a priest solving crimes alongside local police; the production used Gubbio's architecture and streets extensively, boosting tourism by associating the location with the character's deductive escapades.[102] [103] The town's Corsa dei Ceri festival has appeared in documentaries, such as the 2007 PBS film Ubaldo, chronicling participants' devotion during the May 15 race honoring Saint Ubaldo.[104]Sports

Football and Local Teams

Associazione Sportiva Gubbio 1910, commonly known as Gubbio, is the primary professional football club based in Gubbio, Umbria, founded in 1910 as the football section of the multi-sport Società Sportiva Per Esercizi di Gubbio (SPES) by Don Bosone Rossi.[105] The club, nicknamed the Lupi (Wolves) for its aggressive playing style and wearing red-and-blue (rossoblù) kits, competes in Serie C Girone B, Italy's third tier, with home matches at Stadio Pietro Barbetti, a venue constructed in 1977 and renovated in 2011 to hold approximately 5,000 spectators.[106] [107] Key historical milestones include entry into Serie C in 1939, promotion to Serie B in 1947 via a 2-0 playoff victory over Baracca Lugo (followed by relegation the next season), and an unbeaten regional promotion in 1965 with 72 goals scored and 14 conceded in Promozione Regionale.[105] Further promotions came in 1958 to IV Serie, 1987 to C2 via a 1-0 playoff win against Poggibonsi, and 2010 to Lega Pro Prima Divisione after playoffs against San Marino, enabling a return to Serie B in 2011 after 63 years—the club's most recent top-flight proximity before relegation in 2012.[105] [108] Gubbio has experienced multiple relegations, including to Serie D in 1975, Interregionale in 1992, and Eccellenza in 1996, reflecting the challenges of sustaining higher-tier status for a small-town club.[105] In lower divisions, Gubbio has secured two Campionati Interregionali titles, six regional championships, and one regional cup, underscoring regional dominance amid national fluctuations. The club maintains a youth sector (settore giovanile) for developing local talent, integral to community engagement, though no other independent professional teams operate prominently in Gubbio, positioning AS Gubbio 1910 as the focal point for local football fandom. As of the 2025-2026 season, under coach Domenico Di Carlo, the squad averages 25.3 years old and competes mid-table in Serie C Girone B, with recent form showing mixed results including a 2-0 away win over Guidonia Montecelio 1937.[109] [110]Transportation

Road and Public Transit Networks

Gubbio's road network primarily consists of secondary state roads, with no direct connections to Italy's major motorways or autostrade, positioning the town as a destination reliant on regional access routes suited for scenic drives through Umbria's hilly terrain. The Strada Statale 298 Eugubina (SS 298), a winding provincial road, links Gubbio to Perugia approximately 40 kilometers southwest, offering a picturesque route that takes about one hour by car under normal conditions.[111] Similarly, the Strada Statale 219 di Gubbio e Pian d'Assino (SS 219) provides connectivity eastward to Umbertide and the Fossato di Vico area, facilitating links to broader regional infrastructure.[112] These strade statali handle local and tourist traffic, but their curvaceous paths and elevation changes—Gubbio sits at around 500 meters above sea level—necessitate cautious driving, particularly for larger vehicles. The town's medieval core imposes strict vehicle restrictions through a Zona a Traffico Limitato (ZTL), where non-resident cars are prohibited during specified hours, such as 20:30 to 06:00 on weekdays and 11:00 to 06:00 on weekends and holidays, to preserve historic streets and pedestrian safety.[113] Access requires prior registration and authorization, often unavailable to tourists; instead, designated parking lots on the periphery, such as those near Via Repubblica, serve as entry points for visitors entering the centro storico on foot.[114] Public transit in Gubbio centers on a bus network managed by Busitalia Sita Nord, part of the Umbria regional system, with no railway station within the commune itself. Key interurban lines, including E050, E052, and E055, connect Gubbio to Perugia (journey time approximately 60-75 minutes, fares €4-6) and other nearby locales like Fossato di Vico, where passengers can transfer to regional trains.[115][116] These services operate on fixed schedules, with frequencies varying from hourly during peak times to less frequent off-peak, and can be planned or tickets purchased via the SALGO app.[117] For longer distances, supplementary operators like Sulga Autolinee provide seasonal or direct buses to major hubs such as Rome or Florence, though reliability depends on demand and road conditions.[118] Intra-town mobility remains limited due to the steep topography, with residents and visitors often relying on walking or the separate funicular system for upper districts rather than extensive local bus routes.[112]Cable Car and Unique Access Systems

The Funivia Colle Eletto, operational since 1960, serves as Gubbio's primary mechanical link between the historic town center and the Basilica of Sant'Ubaldo atop Monte Ingino, facilitating access to the shrine housing the incorrupt body of the city's patron saint, Ubaldo Baldassini.[119] Constructed in the late 1950s amid growing tourism and local devotion, the system replaced arduous footpaths for pilgrims and visitors, covering a steep ascent of approximately 300 vertical meters from the lower station near Porta Romana at around 532 meters above sea level to the upper station at Colle Eletto.[120] [121] The funicular's design emphasizes efficiency over comfort, with a travel duration of 5 to 6 minutes per leg, powered by a cable-pulled mechanism typical of mid-20th-century alpine transport adaptations.[122] [123] Distinguishing the Funivia from conventional enclosed cable cars, its cabins consist of open-air metal baskets—often likened to oversized bird cages or ski lift gondolas—accommodating two standing passengers behind chest-high railings with no seating or protective roofing, exposing riders to the full 45-50 degree incline and windswept panoramas of Gubbio's medieval skyline and Apennine foothills.[124] [125] This minimalist engineering, while functional for short hauls, has earned descriptions of vertigo-inducing exposure, though safety records remain unmarred by major incidents since inception, underscoring reliable cable tension and periodic maintenance by regional operators.[126] Round-trip fares stand at €7 as of 2024, with operations typically spanning daily hours in peak seasons to support both devotional visits and the annual Ceri race logistics, where oversized wooden candles are occasionally maneuvered nearby.[123] Complementing the funicular, Gubbio's topography demands other adaptive access methods for its tiered medieval layout, including a network of inclined alleys and staircases carved into the hillside, but no comparable mechanical systems exist beyond pedestrian escalators absent in the core historic zones.[127] The Funivia thus represents the town's sole engineered vertical transit solution, integral to preserving accessibility without compromising the integrity of UNESCO-recognized urban fabric below.[128]International Relations

Twin Towns and Sister Cities

Gubbio maintains formal twinning agreements, known as gemellaggi in Italian, with eight cities across Europe and North America to encourage cultural, educational, and economic collaboration.[129] These relationships, some dating back decades, often highlight shared religious traditions or historical migrations, though not all are equally prominent in public records or search engine results.[129] The twin towns include:- Thann, France: Established through official ceremonies emphasizing historical ties, with ongoing events like the Crémation des Trois Sapins festival honoring Saint Ubaldo, Gubbio's patron saint.[130][131]

- Jessup, Pennsylvania, United States: Linked by the unique shared devotion to Saint Ubaldo, manifested in parallel festivals featuring processions of ceri (wooden octagonal candles carried by runners); Jessup's immigrant population from Gubbio in the early 20th century reinforced this bond.[132]

- Wertheim, Germany: Hosts regular meetings of Gubbio representatives with other twinned cities to strengthen ties in tourism and youth programs.[134]

- Lampertheim, Germany: Part of Gubbio's European network, though less frequently highlighted in recent public engagements.[129]

- Szentendre, Hungary: Focuses on youth exchanges and cultural projects, with Gubbio participating in events promoting friendship and local traditions.[135]

- Godmanchester, United Kingdom: Supports bilateral visits and community initiatives.[136]

- Huntingdon, United Kingdom: Complements Gubbio's UK connections through similar exchange programs.[136]

Notable People

Historical Figures

Ubaldo Baldassini, later canonized as Saint Ubaldo, was born around 1084 in Gubbio to a prominent local family and served as the city's bishop from 1129 until his death on May 16, 1160.[138] Known for his piety, diplomatic skills in mediating local conflicts, and defense of Gubbio against imperial forces in 1155, he was venerated as a saint soon after his death and formally canonized by Pope Lucius III in 1192.[139] His incorrupt body remains enshrined in the Basilica of Sant'Ubaldo atop Mount Ingino, where it has been preserved since 1194, and he is revered as Gubbio's principal patron saint, with annual festivals commemorating his legacy.[138] Federico da Montefeltro, born on June 7, 1422, at Castello di Petroia near Gubbio as the illegitimate son of Guidantonio da Montefeltro, rose to prominence as one of Renaissance Italy's most renowned condottieri.[140] After legitimization and succession to his father's titles, he ruled Urbino and extended influence over Gubbio, which fell under Montefeltro control by 1424, fostering cultural patronage including the construction of the Palazzo Ducale in Gubbio.[141] His military campaigns yielded territorial gains and wealth, enabling humanist endeavors like the Gubbio studiolo, a private study adorned with intarsia woodwork symbolizing intellectual virtues; he died in 1482 from a tournament injury.[140] Ottaviano Nelli, born circa 1370 in Gubbio, emerged as a leading late Gothic painter in Umbria, active until his death around 1444–1449.[142] His works, blending sacred themes with vernacular elements, include frescoes in Gubbio's churches such as the Madonna della Pioggia (1413) in the Duomo and altarpieces featuring expressive, rugged figures that influenced regional art.[14] Nelli's style, characterized by bold colors and narrative vitality, helped establish Gubbio as an artistic center in the early 15th century.[142] Giorgio Andreoli, known as Mastro Giorgio (c. 1465/1470–1553), was a pioneering ceramist born in Gubbio who specialized in maiolica lustreware, introducing iridescent gold and ruby finishes by the 1490s.[143] Working with his brothers, he elevated Gubbio's ceramics industry, producing pharmacopeia jars (albarelli) and dishes exported across Europe, with techniques involving third-fire application of metallic oxides for reflective effects.[57] His innovations, documented in signed pieces dated to 1525 and later, made Gubbio synonymous with high-quality luster ceramics until his workshop's dominance waned in the mid-16th century.[144]Modern Notables

Goffredo Fofi (15 April 1937 – 11 July 2025) was an Italian essayist, journalist, activist, and critic of film, literature, and theatre, born in Gubbio to a family of peasant origins.[145][146] His early life in the impoverished rural setting of Gubbio influenced his later focus on social issues, leading him to engage in activism inspired by figures like Danilo Dolci, whom he encountered as a teenager.[147] Fofi contributed to numerous publications, authoring works on cultural critique and participating in intellectual debates, often from a radical perspective that emphasized marginalized voices.[148] Vittoria Bottin (born 8 May 1997) is an Italian actress born in Gubbio.[149] She rose to prominence with her role in the 2020 HBO miniseries We Are Who We Are, directed by Luca Guadagnino, portraying a character in a coming-of-age story set among American military families in Italy.[150] Trained in acting and multilingual, Bottin has pursued a career in international film and television, leveraging her early start in regional theatre and film projects.[151]References

- https://www.[facebook](/page/Facebook).com/visitlackawannapa/posts/lackawannafunfact-did-you-know-that-jessup-pa-was-originally-known-as-saymour-th/1262680539190834/

.svg/250px-Map_of_comune_of_Gubbio_(province_of_Perugia,_region_Umbria,_Italy).svg.png)

.svg/1936px-Map_of_comune_of_Gubbio_(province_of_Perugia,_region_Umbria,_Italy).svg.png)