Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pressure point

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Pressure point (穴位) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 穴位 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 急所 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kana | きゅうしょ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Alternative medicine |

|---|

|

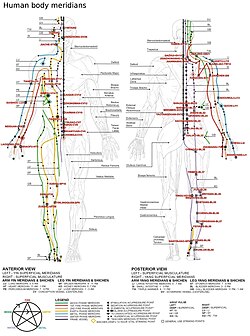

Pressure points[a] derive from the supposed meridian points in Traditional Chinese Medicine, Indian Ayurveda and Siddha medicine, and martial arts. They refer to areas on the human body that may produce significant pain or other effects when manipulated in a specific manner.[2]

History

[edit]

The earliest known concept of pressure points can be seen in the South Indian Varma kalai based on Siddha.[3][2] The concept of pressure points is also present in the old school Japanese martial arts; in a 1942 article in the Shin Budo magazine, Takuma Hisa asserted the existence of a tradition attributing the first development of pressure-point attacks to Shinra Saburō Minamoto no Yoshimitsu (1045–1127).[4]

Hancock and Higashi (1905) published a book which pointed out a number of vital points in Japanese martial arts.[5]

Accounts of pressure-point fighting appeared in Chinese Wuxia fiction novels and became known by the name of Dim Mak, or "Death Touch", in western popular culture in the 1960s.

While it is undisputed that there are sensitive points on the human body where even comparatively weak pressure may induce significant pain or serious injury, the association of kyūsho with notions of death have been harshly criticized.[6][failed verification]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Andrew Nathaniel Nelson, The Original Modern Reader's Japanese-English Character Dictionary, Tuttle Publishing, 2004, p.399. [1]

- ^ a b Zarrilli, Phillip B. "To Heal and/or To Harm: The Vital Spots (Marmmam/Varmam) in Two South Indian Martial Traditions". Kalarippayattu. Department of Drama at the University of Exeter. Archived from the original on 9 Feb 2016. Retrieved 2016-03-01.

- ^ Institute, Suresh K Manoharan, Thirumoolar Varmalogy. "Thirumoolar Varmalogy Institute - Articles - History of Varmakalai". www.varmam.org. Retrieved 2016-03-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ It is also called Internal point. Takuma Hisa Sensei, Shin Budo magazine, November 1942. republished as Hisa, Takuma (Summer 1990). "Daito-Ryu Aiki Budo". Aiki News. 85. Archived from the original on 2007-10-11. Retrieved 2007-07-18. "Yoshimitsu [...] dissected corpses brought back from wars in order to explore human anatomy and mastered a decisive counter-technique as well as discovering lethal atemi. Yoshimitsu then mastered a technique for killing with a single blow. Through such great efforts, he mastered the essence of aiki and discovered the secret techniques of Aiki Budo. Therefore, Yoshimitsu is the person who is credited with being the founder of the original school of Daito-ryu."

- ^ H. Irving Hancock; Katsukuma Higashi (1905). The Complete Kano Jiu-Jitsu (Judo). G. P. Putnam's Sons. ISBN 978-0-486-20639-4. OCLC 650089326.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Felix Mann: "...acupuncture points are no more real than the black spots that a drunkard sees in front of his eyes." (Mann F. Reinventing Acupuncture: A New Concept of Ancient Medicine. Butterworth Heinemann, London, 1996,14.), quoted by Matthew Bauer in Chinese Medicine Times Archived 2009-01-22 at the Wayback Machine, vol 1 issue 4, Aug. 2006, "The Final Days of Traditional Beliefs? - Part One"