Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Liver disease

View on Wikipedia

| Liver disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Hepatic disease |

| |

| A gross pathology specimen of liver metastases caused by pancreatic cancer | |

| Specialty | Hepatology, gastroenterology |

| Types | Fatty liver disease, Hepatitis (and several more)[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Liver function tests[2] |

| Treatment | Depends on type (See types) |

Liver disease, or hepatic disease, is any of many diseases of the liver.[1] If long-lasting it is termed chronic liver disease.[3] Although the diseases differ in detail, liver diseases often have features in common.

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Some of the signs and symptoms of a liver disease are the following:

- Jaundice[4]

- Confusion and altered consciousness caused by hepatic encephalopathy.[5]

- Thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy.[6]

- Risk of bleeding symptoms, particularly taking place in the gastrointestinal tract[7]

Types

[edit]There are more than a hundred different liver diseases. Some of the most common are:[8]

- Fascioliasis, a parasitic infection of liver caused by a liver fluke of the genus FascioIa, mostly FascioIa hepatica.[9]

- Hepatitis, inflammation of the liver, is caused by various viruses (viral hepatitis) also by some liver toxins (e.g. alcoholic hepatitis), autoimmunity (autoimmune hepatitis) or hereditary conditions.[10]

- Alcoholic liver disease is a hepatic manifestation of alcohol overconsumption, including fatty liver disease, alcoholic hepatitis, and cirrhosis. Analogous terms such as "drug-induced" or "toxic" liver disease are also used to refer to disorders caused by various drugs.[11]

- Fatty liver disease (hepatic steatosis) is a reversible condition where large vacuoles of triglyceride fat accumulate in liver cells.[12] Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is a spectrum of disease associated with obesity and metabolic syndrome.[13]

- Hereditary diseases that cause damage to the liver include hemochromatosis,[14] involving accumulation of iron in the body, and Wilson's disease. Liver damage is also a clinical feature of alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency[15] and glycogen storage disease type II.[16]

- In transthyretin-related hereditary amyloidosis, the liver produces a mutated transthyretin protein which has severe neurodegenerative or cardiopathic effects. Liver transplantation can be curative.[17]

- Gilbert's syndrome, a genetic disorder of bilirubin metabolism found in a small percent of the population, can cause mild jaundice.[18]

- Cirrhosis is the formation of fibrous tissue (fibrosis) in the place of liver cells that have died due to a variety of causes, including viral hepatitis, alcohol overconsumption, and other forms of liver toxicity. Cirrhosis causes chronic liver failure.[19]

- Primary liver cancer most commonly manifests as hepatocellular carcinoma or cholangiocarcinoma; rarer forms include angiosarcoma and hemangiosarcoma of the liver. (Many liver malignancies are secondary lesions that have metastasized from primary cancers in the gastrointestinal tract and other organs, such as the kidneys, lungs.)[20]

- Primary biliary cirrhosis is a serious autoimmune disease of the bile capillaries.[21]

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis is a serious chronic inflammatory disease of the bile duct, which is believed to be autoimmune in origin.[22]

- Budd–Chiari syndrome is the clinical picture caused by occlusion of the hepatic vein.[23]

-

Ground glass hepatocytes

-

Primary biliary cirrhosis

-

Budd–Chiari syndrome

Mechanisms

[edit]Liver diseases can develop through several mechanisms:

DNA damage

[edit]One general mechanism, increased DNA damage, is shared by some of the major liver diseases, including infection by hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus, heavy alcohol consumption, and obesity.[24]

Viral infection by hepatitis B virus, or hepatitis C virus causes an increase of reactive oxygen species. The increase in intracellular reactive oxygen species is about 10,000-fold with chronic hepatitis B virus infection and 100,000-fold following hepatitis C virus infection.[25] This increase in reactive oxygen species causes inflammation[25] and more than 20 types of DNA damage.[26] Oxidative DNA damage is mutagenic[27] and also causes epigenetic alterations at the sites of DNA repair.[28] Epigenetic alterations and mutations affect the cellular machinery that may cause the cell to replicate at a higher rate or result in the cell avoiding apoptosis, and thus contribute to liver disease.[29] By the time accumulating epigenetic and mutational changes eventually cause hepatocellular carcinoma, epigenetic alterations appear to have an even larger role in carcinogenesis than mutations. Only one gene, TP53, is mutated in more than 20% of liver cancers while 41 genes each have hypermethylated promoters (repressing gene expression) in more than 20% of liver cancers.[30]

Alcohol consumption in excess causes a build-up of acetaldehyde. Acetaldehyde and free radicals generated by metabolizing alcohol induce DNA damage and oxidative stress.[31][32][33] In addition, activation of neutrophils in alcoholic liver disease contributes to the pathogenesis of hepatocellular damage by releasing reactive oxygen species (which can damage DNA).[34] The level of oxidative stress and acetaldehyde-induced DNA adducts due to alcohol consumption does not appear sufficient to cause increased mutagenesis.[34] However, as reviewed by Nishida et al.,[28] alcohol exposure, causing oxidative DNA damage (which is repairable), can result in epigenetic alterations at the sites of DNA repair. Alcohol-induced epigenetic alterations of gene expression appear to lead to liver injury and ultimately carcinoma.[35]

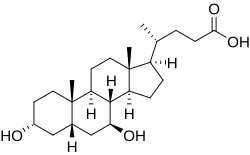

Obesity is associated with a higher risk of primary liver cancer.[36] As shown with mice, obese mice are prone to liver cancer, likely due to two factors. Obese mice have increased pro-inflammatory cytokines. Obese mice also have higher levels of deoxycholic acid, a product of bile acid alteration by certain gut microbes, and these microbes are increased with obesity. The excess deoxycholic acid causes DNA damage and inflammation in the liver, which, in turn, can lead to liver cancer.[37]

Other relevant aspects

[edit]Several liver diseases are due to viral infection. Viral hepatitides such as Hepatitis B virus and Hepatitis C virus can be vertically transmitted during birth via contact with infected blood.[38][39] According to a 2012 NICE publication, "about 85% of hepatitis B infections in newborns become chronic".[40] In occult cases, Hepatitis B virus is present by hepatitis B virus DNA, but testing for HBsAg is negative.[41] High consumption of alcohol can lead to several forms of liver disease including alcoholic hepatitis, alcoholic fatty liver disease, cirrhosis, and liver cancer.[42] In the earlier stages of alcoholic liver disease, fat builds up in the liver's cells due to increased creation of triglycerides and fatty acids and a decreased ability to break down fatty acids.[43] Progression of the disease can lead to liver inflammation from the excess fat in the liver. Scarring in the liver often occurs as the body attempts to heal and extensive scarring can lead to the development of cirrhosis in more advanced stages of the disease.[43] Approximately 3–10% of individuals with cirrhosis develop a form of liver cancer known as hepatocellular carcinoma.[43] According to Tilg, et al., gut microbiome could very well have an effect, be involved in the pathophysiology, on the various types of liver disease which an individual may encounter.[44] Insight into the exact causes and mechanisms mediating pathophysiology of the liver is quickly progressing due to the introduction new technological approaches like Single cell sequencing and kinome profiling [45]

Air pollutants

[edit]Particulate matter or carbon black are common pollutants. They have a direct toxic effect on the liver; cause inflammation of liver caused by and thereby impact lipid metabolism and fatty liver disease; and can translocate from the lungs to the liver.[46]

Because particulate matter and carbon black are very diverse and each has different toxicodynamics, detailed mechanisms of translocation are not clear. Water-soluble fractions of particulate matter are the most important part of translocation to the liver, through extrapulmonary circulation. When particulate matter gets into the bloodstream, it combines with immune cells and stimulates innate immune responses. Pro-inflammatory cytokines are released and cause disease progression.[46]

Diagnosis

[edit]A number of liver function tests are available to test the proper function of the liver. These test for the presence of enzymes in blood that are normally most abundant in liver tissue, metabolites or products. serum proteins, serum albumin, serum globulin, alanine transaminase, aspartate transaminase, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time.[2]

Imaging tests such as transient elastography, ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging can be used to show the liver tissue and the bile ducts. Liver biopsy can be performed to examine liver tissue to distinguish between various conditions; tests such as elastography may reduce the need for biopsy in some situations.[47]

In liver disease, prothrombin time is longer than usual.[6] In addition, the amounts of both coagulation factors and anticoagulation factors are reduced as a diseased liver cannot productively synthesize them as it did when healthy.[48] Nonetheless, there are two exceptions in this falling tendency: coagulation factor VIII and von Willebrand factor, a platelet adhesive protein.[48] Both inversely rise in the setting of hepatic insufficiency, thanks to the drop of hepatic clearance and compensatory productions from other sites of the body.[48] Fibrinolysis generally proceeds faster with acute liver failure and advanced stage liver disease, unlike chronic liver disease in which concentration of fibrinogen remains unchanged.[48]

A previously undiagnosed liver disease may become evident first after autopsy.[citation needed] Following are gross pathology images:

-

Diffuse cirrhosis

-

Macronodular cirrhosis

-

Nutmeg texture of congestive hepatopathy

Treatment

[edit]

Anti-viral medications are available to treat infections such as hepatitis B.[49] Other conditions may be managed by slowing down disease progression, for example:

- By using steroid-based drugs in autoimmune hepatitis.[50]

- Regularly removing a quantity of blood from a vein (venesection) in the iron overload condition, hemochromatosis.[51]

- Wilson's disease, a condition where copper builds up in the body, can be managed with drugs that bind copper, allowing it to be passed from the body in urine.[52]

- In cholestatic liver disease, (where the flow of bile is affected due to cystic fibrosis[53]) a medication called ursodeoxycholic acid may be given.[54]

Epidemiology

[edit]

Liver diseases, including conditions such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), alcohol-related liver disease (ALD), and viral hepatitis, are significant public health concerns worldwide. In the United States, NAFLD is the most common chronic liver condition, affecting approximately 24% of the population, with the prevalence rising due to increasing rates of obesity and metabolic syndrome.[55][56] Alcohol-related liver disease accounts for about 4.5% of liver-related deaths globally, underscoring the substantial burden of alcohol misuse.[57] Viral hepatitis, primarily hepatitis B and hepatitis C, remains a leading cause of liver cirrhosis and liver cancer worldwide, despite advances in antiviral therapies and vaccination efforts.[58] Additionally, recent studies have highlighted lean steatotic liver disease (SLD), a subset of NAFLD, affecting over 12% of U.S. adults even in the absence of obesity.[59] These data emphasize the importance of early detection and targeted interventions to manage liver disease and its associated complications effectively.

New research reports the prevalence of lean steatotic liver disease (SLD) in the United States using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2017-2023), researchers estimated the age-adjusted prevalence of lean SLD at 12.8%.[60] This includes 9.3% for lean metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, 1.3% for metabolic dysfunction and alcohol-related steatotic liver disease, and 1.0% for alcohol-related liver disease.[61]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Liver Diseases". MedlinePlus.

- ^ a b MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Liver function tests

- ^ "NHS Choices". Cirrhosis. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ^ "Liver Disease | NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Retrieved 2021-11-30.

- ^ "Alcoholic Liver Disease". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ a b Blonski W, Siropaides T, Reddy KR (2007). "Coagulopathy in liver disease". Current Treatment Options in Gastroenterology. 10 (6): 464–73. doi:10.1007/s11938-007-0046-7. ISSN 1092-8472. PMID 18221607. S2CID 23396752.

- ^ Tripodi A, Mannucci PM (2011-07-14). "The Coagulopathy of Chronic Liver Disease". New England Journal of Medicine. 365 (2). Massachusetts Medical Society: 147–156. doi:10.1056/nejmra1011170. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 21751907. S2CID 198152.

- ^ "Liver disease – NHS Choices". www.nhs.uk. Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- ^ "CDC – Fasciola". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- ^ "Hepatitis". MedlinePlus.

- ^ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Alcoholic liver disease

- ^ "Hepatic steatosis". Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- ^ "Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease – NHS Choices". www.nhs.uk. Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- ^ "Hemochromatosis". MedlinePlus.

- ^ "Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency". MedlinePlus.

- ^ Leslie N, Tinkle BT (1993). "Pompe Disease". In Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Wallace SE, Amemiya A, Bean LJ, Bird TD, Dolan CR, Fong CT (eds.). Glycogen Storage Disease Type II (Pompe Disease). Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle. PMID 20301438.

- ^ "Transthyretin amyloidosis". Genetics Home Reference. Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- ^ "Gilbert syndrome". Genetics Home Reference. Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- ^ "Cirrhosis: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". www.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- ^ "Liver cancer – Hepatocellular carcinoma: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". www.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- ^ "Primary biliary cirrhosis: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". www.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- ^ "Sclerosing cholangitis: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". www.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- ^ "Hepatic vein obstruction (Budd-Chiari): MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". www.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- ^ "Chronic Liver Disease/Cirrhosis | Johns Hopkins Medicine Health Library". 12 April 2022.

- ^ a b Iida-Ueno A, Enomoto M, Tamori A, Kawada N (21 April 2017). "Hepatitis B virus infection and alcohol consumption". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 23 (15): 2651–2659. doi:10.3748/wjg.v23.i15.2651. PMC 5403744. PMID 28487602.

- ^ Yu Y, Cui Y, Niedernhofer LJ, Wang Y (December 2016). "Occurrence, Biological Consequences, and Human Health Relevance of Oxidative Stress-Induced DNA Damage". Chemical Research in Toxicology. 29 (12): 2008–2039. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrestox.6b00265. PMC 5614522. PMID 27989142.

- ^ Dizdaroglu M (December 2012). "Oxidatively induced DNA damage: mechanisms, repair and disease". Cancer Letters. 327 (1–2): 26–47. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2012.01.016. PMID 22293091.

- ^ a b Nishida N, Kudo M (2013). "Oxidative stress and epigenetic instability in human hepatocarcinogenesis". Digestive Diseases. 31 (5–6): 447–53. doi:10.1159/000355243. PMID 24281019.

- ^ Shibata T, Aburatani H (June 2014). "Exploration of liver cancer genomes". Nature Reviews. Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 11 (6): 340–9. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2014.6. PMID 24473361. S2CID 8611393.

- ^ Ozen C, Yildiz G, Dagcan AT, Cevik D, Ors A, Keles U, Topel H, Ozturk M (May 2013). "Genetics and epigenetics of liver cancer". New Biotechnology. 30 (4): 381–4. doi:10.1016/j.nbt.2013.01.007. hdl:11693/20956. PMID 23392071.

- ^ Yu HS, Oyama T, Isse T, Kitagawa K, Pham TT, Tanaka M, Kawamoto T (December 2010). "Formation of acetaldehyde-derived DNA adducts due to alcohol exposure". Chemico-Biological Interactions. 188 (3): 367–75. Bibcode:2010CBI...188..367Y. doi:10.1016/j.cbi.2010.08.005. PMID 20813101.

- ^ Lee SM, Kim-Ha J, Choi WY, Lee J, Kim D, Lee J, Choi E, Kim YJ (July 2016). "Interplay of genetic and epigenetic alterations in hepatocellular carcinoma". Epigenomics. 8 (7): 993–1005. doi:10.2217/epi-2016-0027. PMID 27411963.

- ^ "Drinking alcohol causes cancer by 'damaging DNA' - Independent.ie". 5 January 2018.

- ^ a b Wang HJ, Gao B, Zakhari S, Nagy LE (August 2012). "Inflammation in alcoholic liver disease". Annual Review of Nutrition. 32: 343–68. doi:10.1146/annurev-nutr-072610-145138. PMC 3670145. PMID 22524187.

- ^ Shukla SD, Lim RW (2013). "Epigenetic effects of ethanol on the liver and gastrointestinal system". Alcohol Research. 35 (1): 47–55. PMC 3860425. PMID 24313164.

- ^ Aleksandrova K, Stelmach-Mardas M, Schlesinger S (2016). "Obesity and Liver Cancer". Obesity and Cancer. Recent Results in Cancer Research. Vol. 208. pp. 177–198. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-42542-9_10. ISBN 978-3-319-42540-5. PMID 27909908.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ "Gut Bugs Could Explain Obesity-Cancer Link | Science | AAAS". 2013-06-26.

- ^ Benova L, Mohamoud YA, Calvert C, Abu-Raddad LJ (September 2014). "Vertical transmission of hepatitis C virus: systematic review and meta-analysis". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 59 (6): 765–73. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu447. PMC 4144266. PMID 24928290.

- ^ Komatsu H (July 2014). "Hepatitis B virus: where do we stand and what is the next step for eradication?". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 20 (27): 8998–9016. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i27.8998 (inactive 12 July 2025). PMC 4112872. PMID 25083074.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ "Hepatitis B and C: ways to promote and offer testing to people at increased risk of infection | Guidance and guidelines | NICE". www.nice.org.uk. 12 December 2012. Retrieved 2015-06-24.

- ^ Samal J, Kandpal M, Vivekanandan P (January 2012). "Molecular mechanisms underlying occult hepatitis B virus infection". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 25 (1): 142–63. doi:10.1128/CMR.00018-11. PMC 3255968. PMID 22232374.

- ^ Suk KT, Kim MY, Baik SK (September 2014). "Alcoholic liver disease: treatment". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 20 (36): 12934–44. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i36.12934. PMC 4177474. PMID 25278689.

- ^ a b c Williams JA, Manley S, Ding WX (September 2014). "New advances in molecular mechanisms and emerging therapeutic targets in alcoholic liver diseases". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 20 (36): 12908–33. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i36.12908. PMC 4177473. PMID 25278688.

- ^ Tilg H, Cani PD, Mayer EA (December 2016). "Gut microbiome and liver diseases". Gut. 65 (12): 2035–2044. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312729. PMID 27802157.

- ^ Yu B, Mamedov R, Fuhler GM, Peppelenbosch MP (March 2021). "Drug Discovery in Liver Disease Using Kinome Profiling". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 22 (5): 2623. doi:10.3390/ijms22052623. PMC 7961955. PMID 33807722.

- ^ a b Kim JW, Park S, Lim CW, Lee K, Kim B (June 2014). "The role of air pollutants in initiating liver disease". Toxicological Research. 30 (2): 65–70. Bibcode:2014ToxRe..30...65K. doi:10.5487/TR.2014.30.2.065. PMC 4112066. PMID 25071914.

- ^ Tapper EB, Lok AS (August 2017). "Use of Liver Imaging and Biopsy in Clinical Practice". The New England Journal of Medicine. 377 (8): 756–768. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1610570. PMID 28834467. S2CID 205117722.

- ^ a b c d Barton CA (2016). "Treatment of Coagulopathy Related to Hepatic Insufficiency". Critical Care Medicine. 44 (10). Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health): 1927–1933. doi:10.1097/ccm.0000000000001998. ISSN 0090-3493. PMID 27635482. S2CID 11457839.

- ^ De Clercq E, Férir G, Kaptein S, Neyts J (June 2010). "Antiviral treatment of chronic hepatitis B virus infections". Viruses. 2 (6): 1279–305. doi:10.3390/v2061279. PMC 3185710. PMID 21994680.

- ^ Hirschfield GM, Heathcote EJ (2011-12-02). Autoimmune Hepatitis: A Guide for Practicing Clinicians. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-60761-569-9.

- ^ "Phlebotomy Treatment | Treatment and Management | Training & Education | Hemochromatosis (Iron Storage Disease) | NCBDDD | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- ^ "Wilson Disease". www.niddk.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2015-06-21. Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- ^ Suchy FJ, Sokol RJ, Balistreri WF (2014-02-20). Liver Disease in Children. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-72909-4.

- ^ Cheng K, Ashby D, Smyth RL (2017). "Ursodeoxycholic acid for liver disease related to cystic fibrosis". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9 (9) CD000222. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000222.pub4. PMC 6483662. PMID 28891588. Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- ^ Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M (2016). "Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease—Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes". Hepatology. 64 (1): 73–84. doi:10.1002/hep.28431. ISSN 0270-9139. PMID 26707365.

- ^ Younossi ZM, Golabi P, Paik JM, Henry A, Van Dongen C, Henry L (2023). "The global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): a systematic review". Hepatology. 77 (4): 1335–1347. doi:10.1097/HEP.0000000000000004. ISSN 0270-9139. PMC 10026948. PMID 36626630.

- ^ Rehm J, Shield KD (2019-12-13). "Global Burden of Alcohol Use Disorders and Alcohol Liver Disease". Biomedicines. 7 (4): 99. doi:10.3390/biomedicines7040099. ISSN 2227-9059. PMC 6966598. PMID 31847084.

- ^ Olaru ID, Beliz Meier M, Mirzayev F, Prodanovic N, Kitchen PJ, Schumacher SG, Denkinger CM (2023). "Global prevalence of hepatitis B or hepatitis C infection among patients with tuberculosis disease: systematic review and meta-analysis". eClinicalMedicine. 58 101938. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.101938. ISSN 2589-5370. PMC 10113747. PMID 37090436.

- ^ Kim D, Danpanichkul P, Wijarnpreecha K, Cholankeril G, Loomba R, Ahmed A (2025-01-11). "Current Burden of Lean Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease Among US Adults, 2017–2023". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 61 (5): 891–894. doi:10.1111/apt.18501. ISSN 0269-2813.

- ^ Kim D, Danpanichkul P, Wijarnpreecha K, Cholankeril G, Loomba R, Ahmed A (2025). "Current Burden of Lean Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease Among US Adults, 2017–2023". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 61 (5): 891–894. doi:10.1111/apt.18501. ISSN 1365-2036. PMID 39797575.

- ^ "Lean Steatotic Liver Disease Affects 12% of US Adults, Study Finds". HCP Live. 2025-01-16. Retrieved 2025-01-18.

Further reading

[edit]- Friedman LS, Keeffe EB (2011-08-03). Handbook of Liver Disease. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-1-4557-2316-4.

.jpg/250px-Human_liver_with_metastatic_lesions_from_primary_pancreas_carcinoma_(2).jpg)

.jpg)