Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

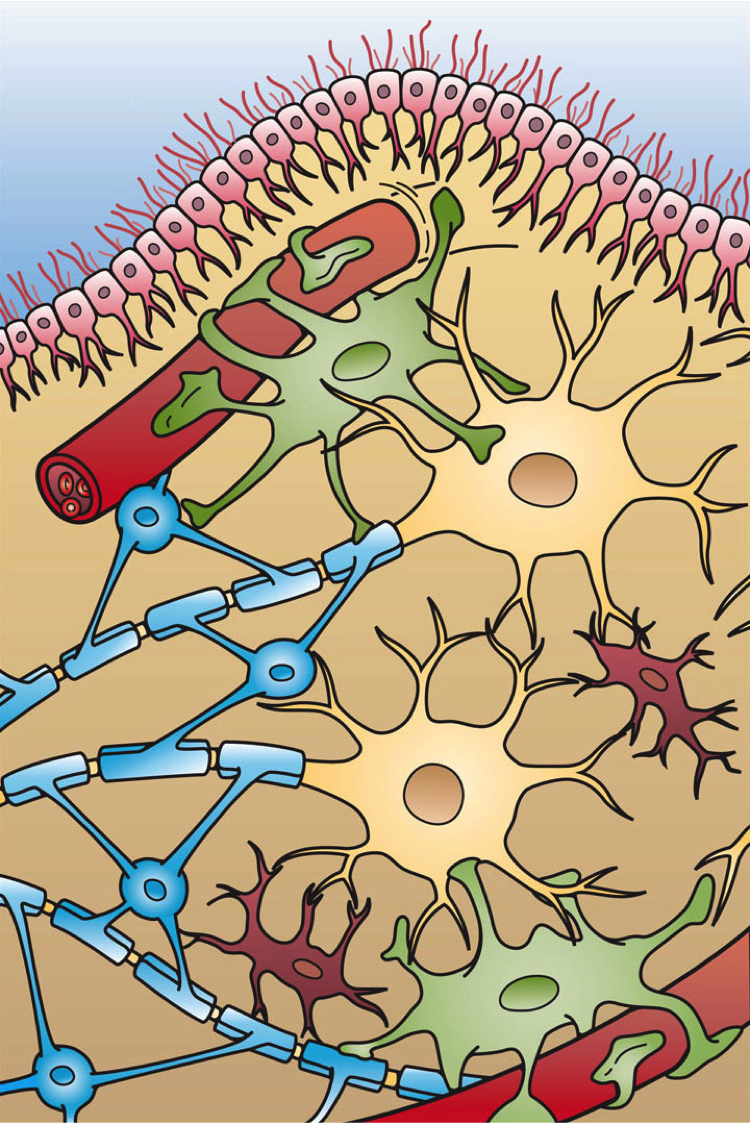

| Glia | |

|---|---|

Illustration of the four different types of glial cells found in the central nervous system: ependymal cells (light pink), astrocytes (green), microglial cells (dark red) and oligodendrocytes (light blue) | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Neuroectoderm for macroglia, and hematopoietic stem cells for microglia |

| System | Nervous system |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D009457 |

| TA98 | A14.0.00.005 |

| TH | H2.00.06.2.00001 |

| FMA | 54536 54541, 54536 |

| Anatomical terms of microanatomy | |

Glia, also called glial cells (gliocytes) or neuroglia, are non-neuronal cells in the central nervous system (the brain and the spinal cord) and in the peripheral nervous system that do not produce electrical impulses. The neuroglia make up more than one half the volume of neural tissue in the human body.[1] They maintain homeostasis, form myelin, and provide support and protection for neurons.[2] In the central nervous system, glial cells include oligodendrocytes (that produce myelin), astrocytes, ependymal cells and microglia, and in the peripheral nervous system they include Schwann cells (that produce myelin), and satellite cells.

Function

[edit]Glia have four main functions:

- to structurally support neurons, holding them in place

- to supply nutrients and oxygen to neurons

- to insulate one neuron from another

- to destroy pathogens and remove dead neurons.

They also play a role in neurotransmission and synaptic connections,[3] and in physiological processes such as breathing.[4][5][6] While glia were thought to outnumber neurons by a ratio of 10:1, studies using newer methods and reappraisal of historical quantitative evidence suggests an overall ratio of less than 1:1, with substantial variation between different brain tissues.[7][8]

Glial cells have far more cellular diversity and functions than neurons, and can respond to and manipulate neurotransmission in many ways. Additionally, they can affect both the preservation and consolidation of memories.[1]

Glia were discovered in 1856, by the pathologist Rudolf Virchow in his search for a "connective tissue" in the brain.[9] The term derives from Greek γλία and γλοία "glue"[10] (English: /ˈɡliːə/ or /ˈɡlaɪə/), and suggests the original impression that they were the glue of the nervous system.

Types

[edit]

Macroglia

[edit]Derived from ectodermal tissue.

| Location | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| CNS | Astrocytes |

Astrocytes (also called astroglia) have numerous projections that link neurons to their blood supply while forming the blood–brain barrier. They regulate the external chemical environment of neurons by removing excess potassium ions and recycling neurotransmitters released during synaptic transmission. Astrocytes may regulate vasoconstriction and vasodilation by producing substances such as arachidonic acid, whose metabolites are vasoactive. Astrocytes signal each other using ATP. The gap junctions (also known as electrical synapses) between astrocytes allow the messenger molecule IP3 to diffuse from one astrocyte to another. IP3 activates calcium channels on cellular organelles, releasing calcium into the cytoplasm. This calcium may stimulate the production of more IP3 and cause release of ATP through channels in the membrane made of pannexins. The net effect is a calcium wave that propagates from cell to cell. Extracellular release of ATP and consequent activation of purinergic receptors on other astrocytes may also mediate calcium waves in some cases. In general, there are two types of astrocytes, protoplasmic and fibrous, similar in function but distinct in morphology and distribution. Protoplasmic astrocytes have short, thick, highly branched processes and are typically found in gray matter. Fibrous astrocytes have long, thin, less-branched processes and are more commonly found in white matter. It has recently been shown that astrocyte activity is linked to blood flow in the brain, and that this is what is actually being measured in fMRI.[11] They also have been involved in neuronal circuits playing an inhibitory role after sensing changes in extracellular calcium.[12] Human astrocytes are larger and more abundant than any other animals'.[13] |

| CNS | Oligodendrocytes |

Oligodendrocytes are cells that coat axons in the CNS with their cell membrane, forming a specialized membrane differentiation called myelin, producing the myelin sheath. The myelin sheath provides insulation to the axon that allows electrical signals to propagate more efficiently.[14] |

| CNS | Ependymal cells |

Ependymal cells, also named ependymocytes, line the spinal cord and the ventricular system of the brain. These cells are involved in the creation and secretion of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and beat their cilia to help circulate the CSF and make up the blood-CSF barrier. They are also thought to act as neural stem cells.[15] |

| CNS | Radial glia |

Radial glia cells arise from neuroepithelial cells after the onset of neurogenesis. Their differentiation abilities are more restricted than those of neuroepithelial cells. In the developing nervous system, radial glia function both as neuronal progenitors and as a scaffold upon which newborn neurons migrate. In the mature brain, the cerebellum and retina retain characteristic radial glial cells. In the cerebellum, these are Bergmann glia, which regulate synaptic plasticity. In the retina, the radial Müller cell is the glial cell that spans the thickness of the retina and, in addition to astroglial cells,[16] participates in a bidirectional communication with neurons.[17] |

| PNS | Schwann cells |

Similar in function to oligodendrocytes, Schwann cells provide myelination to axons in the peripheral nervous system (PNS). They also have phagocytotic activity and clear cellular debris that allows for regrowth of PNS neurons.[18] |

| PNS | Satellite cells |

Satellite glial cells are small cells that surround neurons in sensory, sympathetic, and parasympathetic ganglia.[19] These cells help regulate the external chemical environment. Like astrocytes, they are interconnected by gap junctions and respond to ATP by elevating the intracellular concentration of calcium ions. They are highly sensitive to injury and inflammation and appear to contribute to pathological states, such as chronic pain.[20] |

| PNS | Enteric glial cells |

Are found in the intrinsic ganglia of the digestive system. Glia cells are thought to have many roles in the enteric system, some related to homeostasis and muscular digestive processes.[21] |

Microglia

[edit]Microglia are specialized macrophages capable of phagocytosis that protect neurons of the central nervous system.[22] They are derived from the earliest wave of mononuclear cells that originate in the blood islands of the yolk sac early in development, and colonize the brain shortly after the neural precursors begin to differentiate.[23]

These cells are found in all regions of the brain and spinal cord. Microglial cells are small relative to macroglial cells, with changing shapes and oblong nuclei. They are mobile within the brain and multiply when the brain is damaged. In the healthy central nervous system, microglia processes constantly sample all aspects of their environment (neurons, macroglia and blood vessels). In a healthy brain, microglia direct the immune response to brain damage and play an important role in the inflammation that accompanies the damage. Many diseases and disorders are associated with deficient microglia, such as Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease and ALS.

Other

[edit]Pituicytes from the posterior pituitary are glial cells with characteristics in common to astrocytes.[24] Tanycytes in the median eminence of the hypothalamus are a type of ependymal cell that descend from radial glia and line the base of the third ventricle.[25] Drosophila melanogaster, the fruit fly, contains numerous glial types that are functionally similar to mammalian glia but are nonetheless classified differently.[26]

Total number

[edit]In general, neuroglial cells are smaller than neurons. There are approximately 85 billion glial cells in the human brain, about the same number as neurons.[8] Glial cells make up about half the total volume of the brain and spinal cord.[27] The glia to neuron-ratio varies from one part of the brain to another. The glia to neuron-ratio in the cerebral cortex is 3.72 (60.84 billion glia (72%); 16.34 billion neurons), while that of the cerebellum is only 0.23 (16.04 billion glia; 69.03 billion neurons). The ratio in the cerebral cortex gray matter is 1.48, with 3.76 for the gray and white matter combined.[27] The ratio of the basal ganglia, diencephalon and brainstem combined is 11.35.[27]

The total number of glial cells in the human brain is distributed into the different types with oligodendrocytes being the most frequent (45–75%), followed by astrocytes (19–40%) and microglia (about 10% or less).[8]

Development

[edit]

Most glia are derived from ectodermal tissue of the developing embryo, in particular the neural tube and crest. The exception is microglia, which are derived from hematopoietic stem cells. In the adult, microglia are largely a self-renewing population and are distinct from macrophages and monocytes, which infiltrate an injured and diseased CNS.

In the central nervous system, glia develop from the ventricular zone of the neural tube. These glia include the oligodendrocytes, ependymal cells, and astrocytes. In the peripheral nervous system, glia derive from the neural crest. These PNS glia include Schwann cells in nerves and satellite glial cells in ganglia.

Capacity to divide

[edit]Glia retain the ability to undergo cell divisions in adulthood, whereas most neurons cannot. The view is based on the general inability of the mature nervous system to replace neurons after an injury, such as a stroke or trauma, where very often there is a substantial proliferation of glia, or gliosis, near or at the site of damage. However, detailed studies have found no evidence that 'mature' glia, such as astrocytes or oligodendrocytes, retain mitotic capacity. Only the resident oligodendrocyte precursor cells seem to keep this ability once the nervous system matures.

Glial cells are known to be capable of mitosis. By contrast, scientific understanding of whether neurons are permanently post-mitotic,[28] or capable of mitosis,[29][30][31] is still developing. In the past, glia had been considered[by whom?] to lack certain features of neurons. For example, glial cells were not believed to have chemical synapses or to release transmitters. They were considered to be the passive bystanders of neural transmission. However, recent studies have shown this to not be entirely true.[32]

Functions

[edit]Some glial cells function primarily as the physical support for neurons. Others provide nutrients to neurons and regulate the extracellular fluid of the brain, especially surrounding neurons and their synapses. During early embryogenesis, glial cells direct the migration of neurons and produce molecules that modify the growth of axons and dendrites. Some glial cells display regional diversity in the CNS and their functions may vary between the CNS regions.[33]

Neuron repair and development

[edit]Glia are crucial in the development of the nervous system and in processes such as synaptic plasticity and synaptogenesis. Glia have a role in the regulation of repair of neurons after injury. In the central nervous system (CNS), glia suppress repair. Glial cells known as astrocytes enlarge and proliferate to form a scar and produce inhibitory molecules that inhibit regrowth of a damaged or severed axon. In the peripheral nervous system (PNS), glial cells known as Schwann cells (or also as neuri-lemmocytes) promote repair. After axonal injury, Schwann cells regress to an earlier developmental state to encourage regrowth of the axon. This difference between the CNS and the PNS, raises hopes for the regeneration of nervous tissue in the CNS. For example, a spinal cord may be able to be repaired following injury or severance.

Myelin sheath creation

[edit]Oligodendrocytes are found in the CNS and resemble an octopus: they have a bulbous cell body with up to fifteen arm-like processes. Each process reaches out to an axon and spirals around it, creating a myelin sheath. The myelin sheath insulates the nerve fiber from the extracellular fluid and speeds up signal conduction along the nerve fiber.[34] In the peripheral nervous system, Schwann cells are responsible for myelin production. These cells envelop nerve fibers of the PNS by winding repeatedly around them. This process creates a myelin sheath, which not only aids in conductivity but also assists in the regeneration of damaged fibers.

Neurotransmission

[edit]Astrocytes are crucial participants in the tripartite synapse.[35][36][37][38] They have several crucial functions, including clearance of neurotransmitters from within the synaptic cleft, which aids in distinguishing between separate action potentials and prevents toxic build-up of certain neurotransmitters such as glutamate, which would otherwise lead to excitotoxicity. Furthermore, astrocytes release gliotransmitters such as glutamate, ATP, and D-serine in response to stimulation.[39]

Clinical significance

[edit]

While glial cells in the PNS frequently assist in regeneration of lost neural functioning, loss of neurons in the CNS does not result in a similar reaction from neuroglia.[18] In the CNS, regrowth will only happen if the trauma was mild, and not severe.[40] When severe trauma presents itself, the survival of the remaining neurons becomes the optimal solution. However, some studies investigating the role of glial cells in Alzheimer's disease are beginning to contradict the usefulness of this feature, and even claim it can "exacerbate" the disease.[41] In addition to affecting the potential repair of neurons in Alzheimer's disease, scarring and inflammation from glial cells have been further implicated in the degeneration of neurons caused by amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.[42]

In addition to neurodegenerative diseases, a wide range of harmful exposure, such as hypoxia, or physical trauma, can lead to the result of physical damage to the CNS.[40] Generally, when damage occurs to the CNS, glial cells cause apoptosis among the surrounding cellular bodies.[40] Then, there is a large amount of microglial activity, which results in inflammation, and, finally, there is a heavy release of growth inhibiting molecules.[40]

History

[edit]Although glial cells and neurons were probably first observed at the same time in the early 19th century, unlike neurons whose morphological and physiological properties were directly observable for the first investigators of the nervous system, glial cells had been considered to be merely "glue" that held neurons together until the mid-20th century.[43]

Glia were first described in 1856 by the pathologist Rudolf Virchow in a comment to his 1846 publication on connective tissue. A more detailed description of glial cells was provided in the 1858 book 'Cellular Pathology' by the same author.[44]

When markers for different types of cells were analyzed, Albert Einstein's brain was discovered to contain significantly more glia than normal brains in the left angular gyrus, an area thought to be responsible for mathematical processing and language.[45] However, out of the total of 28 statistical comparisons between Einstein's brain and the control brains, finding one statistically significant result is not surprising, and the claim that Einstein's brain is different is not scientific (cf. multiple comparisons problem).[46]

Not only does the ratio of glia to neurons increase through evolution, but so does the size of the glia. Astroglial cells in human brains have a volume 27 times greater than in mouse brains.[47]

These important scientific findings may begin to shift the neurocentric perspective into a more holistic view of the brain which encompasses the glial cells as well. For the majority of the twentieth century, scientists had disregarded glial cells as mere physical scaffolds for neurons. Recent publications have proposed that the number of glial cells in the brain is correlated with the intelligence of a species.[48] Moreover, evidences are demonstrating the active role of glia, in particular astroglia, in cognitive processes like learning and memory.[49][50]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Fields, R. Douglas; Araque, Alfonso; Johansen-Berg, Heidi; Lim, Soo-Siang; Lynch, Gary; Nave, Klaus-Armin; Nedergaard, Maiken; Perez, Ray; Sejnowski, Terrence; Wake, Hiroaki (October 2014). "Glial Biology in Learning and Cognition". The Neuroscientist. 20 (5): 426–31. doi:10.1177/1073858413504465. ISSN 1073-8584. PMC 4161624. PMID 24122821.

- ^ Jessen KR, Mirsky R (August 1980). "Glial cells in the enteric nervous system contain glial fibrillary acidic protein". Nature. 286 (5774): 736–37. Bibcode:1980Natur.286..736J. doi:10.1038/286736a0. PMID 6997753. S2CID 4247900.

- ^ Wolosker H, Dumin E, Balan L, Foltyn VN (July 2008). "D-amino acids in the brain: D-serine in neurotransmission and neurodegeneration". The FEBS Journal. 275 (14): 3514–26. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06515.x. PMID 18564180. S2CID 25735605.

- ^ Swaminathan, Nikhil (Jan–Feb 2011). "Glia – the other brain cells". Discover. Archived from the original on 2014-02-08. Retrieved 2011-06-06.

- ^ Gourine AV, Kasymov V, Marina N, et al. (July 2010). "Astrocytes control breathing through pH-dependent release of ATP". Science. 329 (5991): 571–75. Bibcode:2010Sci...329..571G. doi:10.1126/science.1190721. PMC 3160742. PMID 20647426.

- ^ Beltrán-Castillo S, Olivares MJ, Contreras RA, Zúñiga G, Llona I, von Bernhardi R, et al. (2017). "D-serine released by astrocytes in brainstem regulates breathing response to CO2 levels". Nat Commun. 8 (1) 838. Bibcode:2017NatCo...8..838B. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00960-3. PMC 5635109. PMID 29018191.

- ^ von Bartheld, Christopher S. (November 2018). "Myths and truths about the cellular composition of the human brain: A review of influential concepts". Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy. 93: 2–15. doi:10.1016/j.jchemneu.2017.08.004. ISSN 1873-6300. PMC 5834348. PMID 28873338.

- ^ a b c von Bartheld, Christopher S.; Bahney, Jami; Herculano-Houzel, Suzana (2016-12-15). "The search for true numbers of neurons and glial cells in the human brain: A review of 150 years of cell counting". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 524 (18): 3865–95. doi:10.1002/cne.24040. ISSN 1096-9861. PMC 5063692. PMID 27187682.

- ^ "Classic Papers". Network Glia. Max Delbrueck Center für Molekulare Medizin (MDC) Berlin-Buch. Archived from the original on 8 May 2020. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ^ γλοία, γλία. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Swaminathan, N (2008). "Brain-scan mystery solved". Scientific American Mind. Oct–Nov (5): 7. doi:10.1038/scientificamericanmind1008-7b.

- ^ Torres A (2012). "Extracellular Ca2+ Acts as a Mediator of Communication from Neurons to Glia". Science Signaling. 5 Jan 24 (208): 208. doi:10.1126/scisignal.2002160. PMC 3548660. PMID 22275221.

- ^ "The Root of Thought: What do Glial Cells Do?". Scientific American. 2009-10-27. Archived from the original on 2023-06-12. Retrieved 2023-06-12.

- ^ Baumann N, Pham-Dinh D (April 2001). "Biology of oligodendrocyte and myelin in the mammalian central nervous system". Physiological Reviews. 81 (2): 871–927. doi:10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.871. PMID 11274346.

- ^ Johansson CB, Momma S, Clarke DL, Risling M, Lendahl U, Frisén J (January 1999). "Identification of a neural stem cell in the adult mammalian central nervous system". Cell. 96 (1): 25–34. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80956-3. PMID 9989494. S2CID 9658786.

- ^ Newman EA (October 2003). "New roles for astrocytes: regulation of synaptic transmission". Trends in Neurosciences. 26 (10): 536–42. doi:10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00237-6. PMID 14522146. S2CID 14105472.

- ^ Campbell K, Götz M (May 2002). "Radial glia: multi-purpose cells for vertebrate brain development". Trends in Neurosciences. 25 (5): 235–38. doi:10.1016/s0166-2236(02)02156-2. PMID 11972958. S2CID 41880731.

- ^ a b Jessen KR, Mirsky R (September 2005). "The origin and development of glial cells in peripheral nerves". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 6 (9): 671–82. doi:10.1038/nrn1746. PMID 16136171. S2CID 7540462.

- ^ Hanani, M. "Satellite glial cells in sensory ganglia: from form to function". Brain Res. Rev. 48:457–76, 2005

- ^ Ohara PT, Vit JP, Bhargava A, Jasmin L (December 2008). "Evidence for a role of connexin 43 in trigeminal pain using RNA interference in vivo". Journal of Neurophysiology. 100 (6): 3064–73. doi:10.1152/jn.90722.2008. PMC 2604845. PMID 18715894.

- ^ Bassotti G, Villanacci V, Antonelli E, Morelli A, Salerni B (July 2007). "Enteric glial cells: new players in gastrointestinal motility?". Laboratory Investigation. 87 (7): 628–32. doi:10.1038/labinvest.3700564. PMID 17483847.

- ^ Brodal, 2010: p. 19

- ^ "Never-resting microglia: physiological roles in the healthy brain and pathological implications". A Sierra, ME Tremblay, H Wake – 2015 – books.google.com

- ^ Miyata, S; Furuya, K; Nakai, S; Bun, H; Kiyohara, T (April 1999). "Morphological plasticity and rearrangement of cytoskeletons in pituicytes cultured from adult rat neurohypophysis". Neuroscience Research. 33 (4): 299–306. doi:10.1016/s0168-0102(99)00021-8. PMID 10401983. S2CID 24687965.

- ^ Rodríguez, EM; Blázquez, JL; Pastor, FE; Peláez, B; Peña, P; Peruzzo, B; Amat, P (2005). Hypothalamic Tanycytes: A Key Component of Brain–Endocrine Interaction (PDF). International Review of Cytology. Vol. 247. pp. 89–164. doi:10.1016/s0074-7696(05)47003-5. hdl:10366/17544. PMID 16344112.

- ^ Freeman, Marc R. (2015-02-26). "DrosophilaCentral Nervous System Glia". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 7 (11) a020552. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a020552. ISSN 1943-0264. PMC 4632667. PMID 25722465.

- ^ a b c Azevedo FA, Carvalho LR, Grinberg LT, et al. (April 2009). "Equal numbers of neuronal and nonneuronal cells make the human brain an isometrically scaled-up primate brain". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 513 (5): 532–41. doi:10.1002/cne.21974. PMID 19226510. S2CID 5200449.

- ^ Herrup K, Yang Y (May 2007). "Cell cycle regulation in the postmitotic neuron: oxymoron or new biology?". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 8 (5): 368–78. doi:10.1038/nrn2124. PMID 17453017. S2CID 12908713.

- ^ Goldman SA, Nottebohm F (April 1983). "Neuronal production, migration, and differentiation in a vocal control nucleus of the adult female canary brain". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 80 (8): 2390–94. Bibcode:1983PNAS...80.2390G. doi:10.1073/pnas.80.8.2390. PMC 393826. PMID 6572982.

- ^ Eriksson PS, Perfilieva E, Björk-Eriksson T, et al. (November 1998). "Neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus". Nature Medicine. 4 (11): 1313–17. doi:10.1038/3305. PMID 9809557.

- ^ Gould E, Reeves AJ, Fallah M, Tanapat P, Gross CG, Fuchs E (April 1999). "Hippocampal neurogenesis in adult Old World primates". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (9): 5263–67. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.5263G. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.9.5263. PMC 21852. PMID 10220454.

- ^ Fields, R. Douglas (2009). The Other Brain. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-9142-2.[page needed]

- ^ Werkman, Inge L.; Lentferink, Dennis H.; Baron, Wia (2020-07-09). "Macroglial diversity: white and grey areas and relevance to remyelination". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 78 (1): 143–71. doi:10.1007/s00018-020-03586-9. ISSN 1420-9071. PMC 7867526. PMID 32648004.

- ^ Saladin, K (2011). Human anatomy (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 357. ISBN 978-0-07-122207-5.

- ^ Newman, Eric A. (2003). "New roles for astrocytes: Regulation of synaptic transmission". Trends in Neurosciences. 26 (10): 536–42. doi:10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00237-6. PMID 14522146. S2CID 14105472.

- ^ Halassa MM, Fellin T, Haydon PG (2007). "The tripartite synapse: roles for gliotransmission in health and disease". Trends Mol Med. 13 (2): 54–63. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2006.12.005. PMID 17207662.

- ^ Perea G, Navarrete M, Araque A (2009). "Tripartite synapses: astrocytes process and control synaptic information". Trends Neurosci. 32 (8): 421–31. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2009.05.001. hdl:10261/62092. PMID 19615761. S2CID 16355401.

- ^ Santello M, Calì C, Bezzi P (2012). "Gliotransmission and the Tripartite Synapse". Synaptic Plasticity. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 970. pp. 307–31. doi:10.1007/978-3-7091-0932-8_14. ISBN 978-3-7091-0931-1. PMID 22351062.

- ^ Martineau M, Parpura V, Mothet JP (2014). "Cell-type specific mechanisms of D-serine uptake and release in the brain". Front Synaptic Neurosci. 6: 12. doi:10.3389/fnsyn.2014.00012. PMC 4039169. PMID 24910611.

- ^ a b c d Puves, Dale (2012). Neuroscience (5th ed.). Sinauer Associates. pp. 560–80. ISBN 978-0-87893-646-5.

- ^ Lopategui Cabezas, I.; Batista, A. Herrera; Rol, G. Pentón (2014). "Papel de la glía en la enfermedad de Alzheimer. Futuras implicaciones terapéuticas". Neurología. 29 (5): 305–09. doi:10.1016/j.nrl.2012.10.006. PMID 23246214.

- ^ Valori, Chiara F.; Brambilla, Liliana; Martorana, Francesca; Rossi, Daniela (2013-08-03). "The multifaceted role of glial cells in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 71 (2): 287–97. doi:10.1007/s00018-013-1429-7. ISSN 1420-682X. PMC 11113174. PMID 23912896. S2CID 14388918.

- ^ Fan, Xue; Agid, Yves (August 2018). "At the Origin of the History of Glia". Neuroscience. 385: 255–71. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2018.05.050. PMID 29890289. S2CID 48360939.

- ^ Kettenmann H, Verkhratsky A (December 2008). "Neuroglia: the 150 years after". Trends in Neurosciences. 31 (12): 653–59. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2008.09.003. PMID 18945498. S2CID 7135630.

- ^ Diamond MC, Scheibel AB, Murphy GM Jr, Harvey T, "On the Brain of a Scientist: Albert Einstein" Archived 2019-09-26 at the Wayback Machine, Experimental Neurology 1985; 198–204", Retrieved February 18, 2017

- ^ Hines, Terence (2014-07-01). "Neuromythology of Einstein's brain". Brain and Cognition. 88: 21–25. doi:10.1016/j.bandc.2014.04.004. ISSN 0278-2626. PMID 24836969. S2CID 43431697.

- ^ Koob, Andrew (2009). The Root of Thought. FT Press. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-13-715171-4.

- ^ Aw, B.L. "5 Reasons why Glial Cells Were So Critical to Human Intelligence". Scientific Brains. Archived from the original on 1 May 2015. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ Volterra, Andrea; Meldolesi, Jacopo (2004). "Quantal Release of Transmitter: Not Only from Neurons but from Aastrocytes as Well?". Neuroglia. pp. 190–201. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195152227.003.0014. ISBN 978-0-19-515222-7.

- ^ Oberheim, Nancy Ann; Wang, Xiaohai; Goldman, Steven; Nedergaard, Maiken (2006). "Astrocytic complexity distinguishes the human brain" (PDF). Trends in Neurosciences. 29 (10): 547–53. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2006.08.004. PMID 16938356. S2CID 17945890. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-02-21. Retrieved 2023-02-21.

Bibliography

[edit]- Brodal, Per (2010). "Glia". The central nervous system: structure and function. Oxford University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-19-538115-3.

- Kettenmann and Ransom, Neuroglia, Oxford University Press, 2012, ISBN 978-0-19-979459-1 |http://ukcatalogue.oup.com/product/9780199794591.do#.UVcswaD3Ay4%7C Archived 2014-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Puves, Dale (2012). Neuroscience (5th ed.). Sinauer Associates. pp. 560–80. ISBN 978-0-87893-646-5.

Further reading

[edit]- Barres BA (November 2008). "The mystery and magic of glia: a perspective on their roles in health and disease". Neuron. 60 (3): 430–40. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.013. PMID 18995817.

- Role of glia in synapse development Archived 2012-02-07 at the Wayback Machine

- Overstreet, LS (February 2005). "Quantal transmission: not just for neurons". Trends in Neurosciences. 28 (2): 59–62. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2004.11.010. PMID 15667925. S2CID 40224065.

- Peters A (May 2004). "A fourth type of neuroglial cell in the adult central nervous system". Journal of Neurocytology. 33 (3): 345–57. doi:10.1023/B:NEUR.0000044195.64009.27. PMID 15475689. S2CID 39470375.

- Volterra A, Steinhäuser C (August 2004). "Glial modulation of synaptic transmission in the hippocampus". Glia. 47 (3): 249–57. doi:10.1002/glia.20080. PMID 15252814. S2CID 10169165.

- Huang YH, Bergles DE (June 2004). "Glutamate transporters bring competition to the synapse". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 14 (3): 346–52. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2004.05.007. PMID 15194115. S2CID 10725242.

- Artist ADSkyler (uses concepts of neuroscience and found inspiration from Glia)

External links

[edit]- "The Other Brain" Archived 2017-01-09 at the Wayback Machine – The Leonard Lopate Show (WNYC) "Neuroscientist Douglas Field, explains how glia, which make up approximately 85 percent of the cells in the brain, work. In The Other Brain: From Dementia to Schizophrenia, How New Discoveries about the Brain Are Revolutionizing Medicine and Science, he explains recent discoveries in glia research and looks at what breakthroughs in brain science and medicine are likely to come."

- "Network Glia" Archived 2021-04-24 at the Wayback Machine A homepage devoted to glial cells.

Overview

Definition and General Role

Glia, also known as glial cells or neuroglia, are a diverse class of non-neuronal cells in the nervous system that provide essential support to neurons and maintain overall neural function. The term "glia" originates from the Greek word glía, meaning "glue," which historically described their perceived role in binding nervous tissue together. In the human brain, glia constitute nearly half of all cells, with approximately 85 billion glial cells coexisting with about 86 billion neurons. In the cerebral cortex, glia outnumber neurons at a ratio of roughly 3.7:1, with 60.8 billion non-neuronal cells compared to 16.3 billion neurons. These cells are found in both the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS). Glia fulfill critical general roles in the nervous system, including the maintenance of homeostasis by regulating ion concentrations, neurotransmitter clearance, and metabolic support for neurons. They provide a structural framework that organizes neural architecture and insulates neuronal processes, while also modulating neuronal activity through influences on synaptic transmission and plasticity. These functions ensure the efficient operation of neural circuits without glia directly propagating electrical signals. In contrast to neurons, which possess axons and dendrites for specialized signal conduction and typically generate action potentials, glia lack these extensions and do not fire action potentials in the conventional sense. Instead, glia display varied morphologies—ranging from star-shaped to elongated forms—that enable their supportive and regulatory capabilities across diverse neural environments.Evolutionary and Comparative Aspects

Glia emerged alongside neurons during the early evolution of bilaterian animals, with radial glial cells representing an ancestral form that served as progenitors for both neuronal and glial lineages in the last common ancestor of Protostomia and Deuterostomia.[8] This early diversification is evidenced by the presence of radial glia-like cells in diverse bilaterian clades, including annelids and insects, where they contribute to nervous system patterning and support neuronal migration.[9] In comparative terms, glial cells in invertebrates exhibit simpler organization and functions compared to the complex macroglia of vertebrates. For instance, in Drosophila melanogaster, wrapping glia ensheath axons to provide structural support and facilitate waste clearance of neuronal debris, without forming compact myelin sheaths.[10] In contrast, vertebrate macroglia, such as oligodendrocytes, develop intricate multi-layered myelin for electrical insulation, reflecting adaptations to larger, more complex nervous systems.[11] Certain glial functions show remarkable conservation across species, particularly in axon ensheathment. In Caenorhabditis elegans, cephalic sheath glia wrap neuronal processes in a manner analogous to vertebrate oligodendrocytes, promoting neurite stability and synaptic organization, though lacking the lipid-rich myelin characteristic of vertebrates.[12] This conserved ensheathment mechanism underscores the evolutionary continuity of glial-neuronal interactions from nematodes to mammals.[11] Non-mammalian vertebrates display unique glial adaptations tailored to ecological demands, such as extensive myelination in sharks to enable rapid nerve conduction in aquatic environments. In elasmobranchs like the bamboo shark (Chiloscyllium punctatum), oligodendrocyte-derived myelin sheaths develop early in embryogenesis and cover a high proportion of axons, supporting efficient signal propagation over long distances.[13] This adaptation highlights how glial myelination evolved to enhance nervous system performance in diverse vertebrate lineages.[14]Classification and Anatomy

Macroglia

Macroglia, also known as macroglial cells, constitute the primary supportive glial population in the central nervous system (CNS), encompassing several distinct subtypes that provide structural framework.[15] These cells derive from neuroepithelial progenitors and are characterized by their larger size relative to microglia, with specialized morphologies adapted to their locations.[16] Astrocytes are star-shaped macroglial cells featuring numerous branching processes that extend to contact neuronal synapses, blood vessels, and the pial surface, forming a supportive network within neural tissue.[17] They exhibit two main morphological subtypes: protoplasmic astrocytes, which have bushy, highly branched processes and predominate in the CNS gray matter; and fibrous astrocytes, characterized by longer, less branched, fiber-like processes and found primarily in white matter.[18][16] Oligodendrocytes are compact macroglial cells in the CNS with a rounded cell body and thin processes that extend to wrap around axons, forming multilayered myelin sheaths to insulate multiple axonal segments from a single cell.[19] Each oligodendrocyte can myelinate up to 50 axons, enabling efficient coverage of white matter tracts.[20] Ependymal cells form a ciliated, cuboidal to columnar epithelial layer that lines the ventricles of the brain and the central canal of the spinal cord, with apical cilia and microvilli facilitating fluid dynamics.[21][16] Anatomically, astrocytes are predominantly distributed in gray matter regions, where their extensive processes interdigitate with neuronal elements, while oligodendrocytes are concentrated in white matter tracts to support myelinated fiber bundles.[22] Ependymal cells are confined to the ventricular system and spinal canal interfaces.[15]Microglia

Microglia serve as the primary resident immune cells of the central nervous system (CNS), originating from primitive myeloid progenitors in the yolk sac during early embryonic development. Unlike macroglia, such as astrocytes and oligodendrocytes, which derive from neuroepithelial cells of the neural tube, microglia arise from hematopoietic stem cells that migrate into the developing brain around embryonic day 9.5 in mice, establishing a self-renewing population independent of bone marrow contributions in adulthood. In their resting state, microglia exhibit a highly ramified morphology characterized by an elongated soma and extensive, branched processes that extend throughout the brain parenchyma, enabling constant environmental monitoring. Upon activation in response to injury or pathological signals, these cells undergo morphological transformation, retracting their processes and adopting an amoeboid form with a rounded soma and increased motility, facilitating rapid migration to sites of disturbance.[23] Microglia perform ongoing surveillance of the CNS parenchyma through dynamic extension and retraction of their processes, making brief contacts with neuronal synapses at a frequency of approximately once per hour under homeostatic conditions.[24] This vigilant patrolling enables swift responses to localized injury, such as laser-induced damage, where processes converge on the site within minutes to contain and isolate affected areas. Comprising approximately 10-15% of all cells in the adult brain, microglia are evenly distributed across regions, maintaining densities typically ranging from 5,000 to 15,000 cells per mm³, varying by brain region, to ensure comprehensive coverage.[25][26]Other Glial Types

Enteric glia constitute a specialized population of glial cells within the enteric nervous system (ENS) of the gastrointestinal tract, where they provide structural and functional support to enteric neurons in a manner analogous to astrocytes in the central nervous system.[27] These cells are distributed throughout the myenteric and submucosal plexuses, exhibiting diverse morphologies including multipolar and bipolar forms, and they express glial markers such as S100β and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP).[28] Their primary roles include maintaining gut homeostasis by regulating neuronal signaling, supporting epithelial barrier integrity, and modulating immune responses in the intestinal environment.[29] Satellite glial cells are non-myelinating glia that envelop the cell bodies of neurons in peripheral nervous system (PNS) ganglia, such as dorsal root ganglia and autonomic ganglia, forming a protective sheath that isolates neuronal somata from the extracellular space.[30] These cells share molecular features with astrocytes, including expression of GFAP and glutamine synthetase, and they facilitate ion homeostasis, neurotransmitter uptake, and trophic support for sensory and autonomic neurons.[31] In the PNS, satellite glia contribute to the overall glial framework alongside Schwann cells, enhancing neuronal survival and responsiveness to environmental cues.[30] Schwann cells are the primary myelinating glia of the PNS, featuring an elongated structure where each cell envelops a single axonal segment with its plasma membrane to produce a myelin sheath.[32][33] Bergmann glia represent a unique subclass of radial astrocytes located specifically in the cerebellar cortex, where their elongated processes extend from the Purkinje cell layer to the pial surface, forming a scaffold that organizes the molecular layer.[34] During cerebellar development, these cells guide the radial migration of granule cell precursors toward the internal granule layer, ensuring proper foliation and lamination of the cerebellar structure.[35] In mature cerebellum, Bergmann glia maintain synaptic stability by ensheathing Purkinje cell dendrites and modulating extracellular potassium levels, thereby supporting coordinated motor functions.[34] Müller cells serve as the predominant glial elements in the vertebrate retina, spanning the entire retinal thickness with their radial processes that contact photoreceptors, synaptic layers, and the vitreous humor, thereby providing mechanical stability and metabolic provisioning.[36] These cells express enzymes for neurotransmitter recycling, such as glutamine synthetase for glutamate metabolism, and they transport nutrients like glucose and antioxidants to energy-demanding photoreceptors while regulating the retinal extracellular environment.[37] Additionally, Müller cells contribute to retinal optics by acting as light-guiding fibers, minimizing scattering to enhance visual acuity.[38]Number and Distribution

In the adult human brain, the total number of glial cells is estimated at approximately 85 billion, roughly equal to the number of neurons, debunking earlier claims of a much higher glial population. This figure encompasses all major glial types across the central nervous system (CNS), with regional variations reflecting functional specializations; for instance, astrocyte density is notably higher in the cerebral cortex compared to subcortical structures. These estimates derive from systematic analyses of postmortem brain tissue from multiple individuals, highlighting a glia-to-neuron ratio of about 1:1 overall.[39] Glia-to-neuron ratios vary significantly by brain region, underscoring heterogeneous cellular organization. In the cerebral cortex, the ratio reaches approximately 3.7:1, driven largely by macroglial populations supporting complex synaptic networks. Conversely, the cerebellum exhibits a much lower ratio of 0.23:1, where neuronal density is exceptionally high to facilitate rapid motor coordination. In the peripheral nervous system (PNS), ratios are generally lower than in cortical regions, with Schwann cells associating closely with individual axons rather than forming expansive networks.[40][41] Spatial distribution patterns of glial cells further reveal their organized arrangement. Macroglia, including astrocytes and oligodendrocytes, tend to cluster around neurons, synapses, and vasculature, forming intimate tripartite structures that enable localized metabolic and structural support. Microglia, by contrast, are uniformly dispersed throughout the brain parenchyma, maintaining a vigilant, even coverage to detect and respond to disturbances. In the PNS, satellite glial cells envelop neuronal somata in ganglia, while Schwann cells align along axonal lengths.[42] These quantifications rely on rigorous methodological approaches to ensure accuracy and avoid biases from tissue shrinkage or sampling errors. Traditional stereology, employing tools like the optical disector and fractionator probes, enables unbiased estimation of cell numbers through systematic sampling of histological sections. Complementary techniques, such as the isotropic fractionator, homogenize brain tissue to count intact nuclei via fluorescence microscopy, providing rapid whole-brain assessments. For dynamic distribution studies, two-photon microscopy allows non-invasive imaging of labeled glial cells in living animal models, revealing real-time spatial patterns at cellular resolution.[43][44]Development and Physiology

Embryonic Origins and Differentiation

Glial cells in the central nervous system (CNS) primarily originate from the neural tube during embryonic development. Macroglia, including astrocytes and oligodendrocytes, arise from radial glial cells, which serve as neural progenitor cells lining the ventricular zone of the neural tube. These radial glia initially support neurogenesis but transition to gliogenesis, generating glial lineages through asymmetric divisions and differentiation cues. In mammals, gliogenesis occurs predominantly after the peak of neurogenesis, ensuring the establishment of a neuronal framework before glial support structures form. This temporal sequence is evident in rodent models, where gliogenesis initiates around embryonic day 12 (E12) and peaks between E12 and postnatal day 7 (P7), driven by environmental signals such as bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) and fibroblast growth factors (FGFs). Oligodendrocytes, responsible for myelination in the CNS, are specified from oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs) derived from radial glia or, in ventral regions, from Nkx2.1-expressing progenitors in the ventral forebrain. Key transcription factors orchestrate this process: Olig2 is essential for OPC commitment and maintenance, while Sox9 promotes glial fate by repressing neurogenic programs and activating downstream glial genes.[45] Astrocytes differentiate from radial glia in response to similar signaling pathways, with NFIA playing a critical role in promoting astrogliogenesis by regulating gene expression for cytoskeletal and extracellular matrix components. This differentiation is regionally specific, occurring later in dorsal telencephalon compared to ventral regions, and contributes to the diversity of astrocytic subtypes. In the peripheral nervous system (PNS), glial cells such as Schwann cells and satellite cells derive from neural crest cells, multipotent progenitors that migrate from the dorsal neural tube around E8-E9 in mice. These crest cells differentiate into Schwann cell precursors under the influence of neuregulin-1 signaling from axons, leading to myelinating and non-myelinating Schwann cell subtypes. Microglia, the immune-specialized glia, originate from yolk sac erythro-myeloid progenitors that invade the CNS early in development, distinct from the neural tube or crest lineages.Proliferative Capacity and Maintenance

During embryonic development, radial glia serve as the primary neural stem cells in the ventricular zone, capable of self-renewal and asymmetric division to produce neurons and glial progenitors.[46] These cells exhibit stem-like properties, generating intermediate progenitors and directly contributing to cortical layering through their radial processes.[47] As neurogenesis wanes late in development, radial glia transition into astrocytes, adopting mature astrocytic morphologies and functions while retaining some proliferative potential in specific contexts.[48] This transformation involves downregulation of stem cell markers and upregulation of glial-specific proteins like GFAP, ensuring a shift from progenitor roles to supportive ones in the postnatal brain.[49] In adulthood, gliogenesis persists but is regionally restricted, primarily occurring in the subventricular zone (SVZ) where neural stem cells—derived from embryonic radial glia—generate new oligodendrocytes to support myelination and circuit maintenance.[50] These SVZ progenitors, often identified as type B cells, proliferate and differentiate into oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs), which integrate into white matter tracts throughout life. In contrast, astrocyte renewal is limited, with most mature astrocytes arising from local symmetric divisions during early postnatal stages rather than ongoing adult replacement, contributing to the relative stability of astrocytic populations. However, recent studies show that neural stem cells in the adult hippocampus can generate astrocytes through asymmetric or direct differentiation, contributing to limited but ongoing astrogliogenesis in neurogenic niches.[51] Microglia maintain their numbers through local self-renewal via proliferation, independent of peripheral hematopoiesis or bone marrow-derived monocytes under homeostatic conditions.[52] This process involves balanced proliferation and apoptosis, allowing microglia to repopulate territories without infiltration from circulating precursors, as demonstrated in fate-mapping studies using conditional ablation models.[53] Glial proliferation is tightly regulated by signaling pathways and environmental cues; for instance, Notch signaling inhibits division in radial glia and astrocytes, promoting quiescence and preventing excessive gliogenesis during development.[54] Conversely, brain injury activates proliferative responses in glia, including reactive astrogliosis and microglial expansion, driven by factors like cytokines and hypoxia to facilitate repair, though this can lead to scar formation if dysregulated.[55]Cellular Interactions with Neurons

During brain development, radial glia cells serve as scaffolds that guide the radial migration of neurons from the ventricular zone to their final laminar positions in the cerebral cortex. These elongated processes of radial glia provide a physical substrate for neuronal somata to climb via contact-mediated adhesion, ensuring proper layering and organization of the cortical architecture. This contact guidance mechanism is essential for the inside-out pattern of cortical development observed in mammals, where later-born neurons migrate past earlier ones to form superficial layers. Seminal studies in primate models demonstrated that disrupting radial glial integrity impairs neuronal migration, leading to cortical malformations such as lissencephaly. Astrocytes play a critical role in synaptogenesis by actively pruning excess synapses through phagocytosis, thereby refining neural circuits during development and homeostasis. This process involves the recognition and engulfment of synaptic components, particularly those marked for elimination, via specific receptors on astrocytic processes. In particular, astrocytes utilize the multiple EGF-like domains 10 (MEGF10) and Mertk phagocytic pathways to internalize synaptic elements, with neuronal activity strongly influencing the efficiency of this elimination. Genetic ablation of MEGF10 in mice results in increased synaptic density in the retinogeniculate system and hippocampus, highlighting its necessity for circuit maturation. This activity-dependent pruning helps sculpt functional connectivity, preventing overexcitation and supporting learning-induced plasticity.[56][57] Gap junctions formed by connexin proteins facilitate direct metabolic and electrical coupling between glia and neurons, enabling the exchange of ions, metabolites, and second messengers. In astrocytes, connexin 43 (Cx43) and connexin 30 (Cx30) predominate, forming hemichannels and intercellular channels that allow bidirectional communication, such as the transfer of glucose-derived metabolites from glia to neurons under energy demand. This coupling supports neuronal homeostasis by synchronizing astrocytic networks to buffer extracellular potassium and supply energy substrates during high activity. Studies in connexin-deficient models reveal disrupted metabolic support, leading to impaired neuronal function and increased vulnerability to excitotoxicity. Notably, while oligodendrocytes also express connexins for intraglial coupling, direct gap junctions between neurons and glia are uncommon; instead, astrocytic connexins like Cx43 facilitate metabolic and signaling support to neurons.[58][59] Calcium signaling in glia orchestrates gliotransmitter release that modulates neuronal excitability, bridging glial sensing of synaptic activity to circuit-level regulation. Intracellular Ca²⁺ waves in astrocytes, triggered by neuronal glutamate or mechanical stimuli, propagate via inositol trisphosphate (IP₃) receptors and lead to the exocytotic or channel-mediated release of ATP as a key gliotransmitter. Released ATP acts on neuronal purinergic receptors (P2X and P2Y) to either excite or inhibit depending on the neuronal subtype; for instance, it enhances pyramidal neuron firing while suppressing parvalbumin interneuron activity, thus fine-tuning network oscillations. This Ca²⁺-dependent mechanism ensures gliotransmission is activity-gated, preventing tonic interference with synaptic transmission. Dysregulation of astrocytic Ca²⁺ signaling, as seen in Orai1 knockout models, alters ATP release and heightens seizure susceptibility by desynchronizing neuronal excitability.[60][61]Functions

Structural and Metabolic Support

Astrocytes, a major type of glial cell in the central nervous system, provide essential structural support to neurons and vasculature by forming extensive networks of processes that stabilize the brain's architecture. These processes, particularly the endfeet, envelop blood vessels, creating perivascular networks that anchor the vasculature and prevent its displacement during physiological stresses or mechanical forces. This scaffolding role is critical for maintaining the integrity of the neurovascular unit, as astrocytic endfeet cover nearly the entire surface of cerebral capillaries, facilitating physical stability and enabling efficient exchange between blood and brain tissue.[62] Disruptions in these endfoot formations, such as those observed in pathological conditions, lead to vascular instability and impaired tissue support.[63] In addition to structural scaffolding, glia play a pivotal role in metabolic support by shuttling nutrients to neurons, which rely heavily on astrocytic supply for energy demands. Astrocytes uptake glucose from the bloodstream primarily through glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) located on their endfeet, converting it into lactate via glycolysis within their cytoplasm. This lactate is then exported to neurons through monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs), such as MCT1 and MCT4 on astrocytes and MCT2 on neurons, supporting oxidative metabolism and synaptic activity, in addition to direct neuronal glucose uptake.[64] This astrocyte-neuron lactate shuttle is particularly vital during high-energy states like learning and memory consolidation, where astrocytic glycogen stores serve as a rapid reserve.[65] Glial cells also maintain ion homeostasis, a key aspect of metabolic support, by regulating extracellular potassium levels to prevent neuronal hyperexcitability. Astrocytes express inwardly rectifying potassium channel 4.1 (Kir4.1), which facilitates spatial buffering by taking up excess potassium ions released during neuronal firing and redistributing them through gap junctions or across the astrocytic membrane.[66] This process is essential for restoring baseline extracellular potassium concentrations, with Kir4.1 accounting for the majority of astrocytic potassium conductance, particularly in perineuronal processes.[67] Loss of Kir4.1 function disrupts this buffering, leading to elevated extracellular potassium and associated neurological dysfunction.[68] Furthermore, astrocytes contribute to the formation and maintenance of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) by inducing tight junctions in endothelial cells through secreted signaling molecules. Astrocytic endfeet release factors such as sonic hedgehog and angiotensin II that promote the assembly of tight junction proteins like claudin-5 and occludin in the endothelial monolayer, enhancing barrier impermeability to protect the neural environment.[69] Coculture studies demonstrate that direct contact or soluble signals from astrocytes upregulate these junctional complexes, underscoring their inductive role in BBB development during brain vascularization.[70] This glial-endothelial interaction ensures selective nutrient passage while excluding toxins, with astrocytic ablation resulting in junctional breakdown and barrier compromise.[71]Myelination and Axonal Insulation

Myelination is a specialized process carried out by macroglial cells in which oligodendrocytes in the central nervous system (CNS) and Schwann cells in the peripheral nervous system (PNS) produce multilayered sheaths of myelin that insulate axons, facilitating efficient neural signal transmission.[72] Oligodendrocytes can myelinate multiple axons simultaneously, whereas each Schwann cell typically wraps a single axonal segment.[73] This insulation is essential for saltatory conduction, where action potentials propagate rapidly by jumping between unmyelinated gaps.[74] The myelin sheath consists primarily of lipids, comprising approximately 70-85% of its dry mass, with the remainder being proteins.[75] Key lipids include cholesterol (about 40%), phospholipids (40%), and glycolipids (20%), such as galactocerebroside and sphingomyelin, which contribute to the sheath's compact, hydrophobic structure.[76] In the CNS, major proteins include myelin basic protein (MBP, ~30% of total protein) and proteolipid protein (PLP, ~38%), which stabilize the multilayered wraps and maintain compactness.[77] During myelination, glial processes extend along the axon and spiral around it, forming concentric layers of plasma membrane that fuse to create the myelin sheath, with periodic interruptions known as nodes of Ranvier.[78] These nodes concentrate voltage-gated sodium channels, enabling saltatory conduction where the action potential regenerates only at these sites.[79] The process begins with axonal contact by the glial cell, followed by proliferation and wrapping, guided by axonal signals like neuregulin.[80] Biophysically, myelin enhances conduction velocity by 50- to 100-fold, elevating it from less than 1 m/s in unmyelinated axons to 50-100 m/s, primarily through saltatory propagation and reduced energy expenditure.[81] A key mechanism is the reduction in axonal membrane capacitance, as myelin increases the effective thickness (d) of the insulating layer; capacitance (C) is given by the formulawhere is the permittivity, A is the surface area, and d is the distance between conductive layers (the axoplasm and extracellular fluid).[82] This decrease in C minimizes the charge required to depolarize the membrane during action potential propagation.[83] Following demyelination, such as from injury or disease, both oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells exhibit remyelination potential, often occurring spontaneously and restoring partial conduction efficiency.[84] In the CNS, oligodendrocyte progenitor cells differentiate to form new sheaths, while in the PNS, Schwann cells dedifferentiate, proliferate, and remyelinate.[85] This regenerative capacity highlights glia's role in axonal repair, though full restoration varies by context.[86]