Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Mathematical constant

View on Wikipedia

A mathematical constant is a number whose value is fixed by an unambiguous definition, often referred to by a special symbol (e.g., an alphabet letter), or by mathematicians' names to facilitate using it across multiple mathematical problems.[1] Constants arise in many areas of mathematics, with constants such as e and π occurring in such diverse contexts as geometry, number theory, statistics, and calculus.

Some constants arise naturally by a fundamental principle or intrinsic property, such as the ratio between the circumference and diameter of a circle (π). Other constants are notable more for historical reasons than for their mathematical properties. The more popular constants have been studied throughout the ages and computed to many decimal places.

All named mathematical constants are definable numbers, and usually are also computable numbers (Chaitin's constant being a significant exception).

Basic mathematical constants

[edit]These are constants which one is likely to encounter during pre-college education in many countries.

Pythagoras' constant √2

[edit]

The square root of 2, often known as root 2 or Pythagoras' constant, and written as √2, is the unique positive real number that, when multiplied by itself, gives the number 2. It is more precisely called the principal square root of 2, to distinguish it from the negative number with the same property.

Geometrically the square root of 2 is the length of a diagonal across a square with sides of one unit of length; this follows from the Pythagorean theorem. It is an irrational number, possibly the first number to be known as such, and an algebraic number. Its numerical value truncated to 50 decimal places is:

Alternatively, the quick approximation 99/70 (≈ 1.41429) for the square root of two was frequently used before the common use of electronic calculators and computers. Despite having a denominator of only 70, it differs from the correct value by less than 1/10,000 (approx. 7.2 × 10−5).

Its simple continued fraction is periodic and given by:

Archimedes' constant π

[edit]

The constant π (pi) has a natural definition in Euclidean geometry as the ratio between the circumference and diameter of a circle. It may be found in many other places in mathematics: for example, the Gaussian integral, the complex roots of unity, and Cauchy distributions in probability. However, its ubiquity is not limited to pure mathematics. It appears in many formulas in physics, and several physical constants are most naturally defined with π or its reciprocal factored out. For example, the ground state wave function of the hydrogen atom is

where is the Bohr radius.

π is an irrational number, transcendental number and an algebraic period.

The numeric value of π is approximately:

Unusually good approximations are given by the fractions 22/7 and 355/113.

Memorizing as well as computing increasingly more digits of π is a world record pursuit.

Euler's number e

[edit]

Euler's number e, also known as the exponential growth constant, appears in many areas of mathematics, and one possible definition of it is the value of the following expression:

The constant e is intrinsically related to the exponential function .

The Swiss mathematician Jacob Bernoulli discovered that e arises in compound interest: If an account starts at $1, and yields interest at annual rate R, then as the number of compounding periods per year tends to infinity (a situation known as continuous compounding), the amount of money at the end of the year will approach eR dollars.

The constant e also has applications to probability theory, where it arises in a way not obviously related to exponential growth. As an example, suppose that a slot machine with a one in n probability of winning is played n times, then for large n (e.g., one million), the probability that nothing will be won will tend to 1/e as n tends to infinity.

Another application of e, discovered in part by Jacob Bernoulli along with French mathematician Pierre Raymond de Montmort, is in the problem of derangements, also known as the hat check problem.[2] Here, n guests are invited to a party, and at the door each guest checks his hat with the butler, who then places them into labelled boxes. The butler does not know the name of the guests, and hence must put them into boxes selected at random. The problem of de Montmort is: what is the probability that none of the hats gets put into the right box. The answer is

which, as n tends to infinity, approaches 1/e.

e is an irrational number and a transcendental number.

The numeric value of e is approximately:

The imaginary unit i

[edit]

The imaginary unit or unit imaginary number, denoted as i, is a mathematical concept which extends the real number system to the complex number system The imaginary unit's core property is that i2 = −1. The term "imaginary" was coined because there is no (real) number having a negative square.

There are in fact two complex square roots of −1, namely i and −i, just as there are two complex square roots of every other real number (except zero, which has one double square root).

In contexts where the symbol i is ambiguous or problematic, j or the Greek iota (ι) is sometimes used. This is in particular the case in electrical engineering and control systems engineering, where the imaginary unit is often denoted by j, because i is commonly used to denote electric current.

The golden ratio φ

[edit]

The number φ, also called the golden ratio, turns up frequently in geometry, particularly in figures with pentagonal symmetry. Indeed, the length of a regular pentagon's diagonal is φ times its side. The vertices of a regular icosahedron are those of three mutually orthogonal golden rectangles. Also, it is related to the Fibonacci sequence, related to growth by recursion.[3] Kepler proved that it is the limit of the ratio of consecutive Fibonacci numbers.[4] The golden ratio has the slowest converging continued fraction of any irrational number.[5] It is, for that reason, one of the worst cases of Lagrange's approximation theorem and it is an extremal case of the Hurwitz inequality for diophantine approximations to irrational numbers. This may be why angles close to the golden ratio often show up in phyllotaxis (the growth of plants).[6] It is approximately equal to:

or, more precisely

Constants in advanced mathematics

[edit]These are constants which are encountered frequently in higher mathematics.

The Euler–Mascheroni constant γ

[edit]

Euler's constant or the Euler–Mascheroni constant is defined as the limiting difference between the harmonic series and the natural logarithm:

It appears frequently in mathematics, especially in number theoretical contexts such as Mertens' third theorem or the growth rate of the divisor function. It has relations to the gamma function and its derivatives as well as the zeta function and there exist many different integrals and series involving .

Despite the ubiquity of the Euler-Mascheroni constant, many of its properties remain unknown. That includes the major open questions of whether it is a rational or irrational number and whether it is algebraic or transcendental. In fact, has been described as a mathematical constant "shadowed only and in importance."[7]

The numeric value of is approximately:

Apéry's constant ζ(3)

[edit]Apery's constant is defined as the sum of the reciprocals of the cubes of the natural numbers:It is the special value of the Riemann zeta function at . The quest to find an exact value for this constant in terms of other known constants and elementary functions originated when Euler famously solved the Basel problem by giving . To date no such value has been found and it is conjectured that there is none.[8] However, there exist many representations of in terms of infinite series.

Apéry's constant arises naturally in a number of physical problems, including in the second- and third-order terms of the electron's gyromagnetic ratio, computed using quantum electrodynamics.[9]

is known to be an irrational number which was proven by the French mathematician Roger Apéry in 1979. It is however not known whether it is algebraic or transcendental.

The numeric value of Apéry's constant is approximately:

Catalan's constant G

[edit]Catalan's constant is defined by the alternating sum of the reciprocals of the odd square numbers:

It is the special value of the Dirichlet beta function at . Catalan's constant appears frequently in combinatorics and number theory and also outside mathematics such as in the calculation of the mass distribution of spiral galaxies.[10]

Questions about the arithmetic nature of this constant also remain unanswered, having been called "arguably the most basic constant whose irrationality and transcendence (though strongly suspected) remain unproven."[11] There exist many integral and series representations of Catalan's constant.

It is named after the French and Belgian mathematician Charles Eugène Catalan.

The numeric value of is approximately:

The Feigenbaum constants α and δ

[edit]

Iterations of continuous maps serve as the simplest examples of models for dynamical systems.[12] Named after mathematical physicist Mitchell Feigenbaum, the two Feigenbaum constants appear in such iterative processes: they are mathematical invariants of logistic maps with quadratic maximum points[7] and their bifurcation diagrams. Specifically, the constant α is the ratio between the width of a tine and the width of one of its two subtines, and the constant δ is the limiting ratio of each bifurcation interval to the next between every period-doubling bifurcation.

The logistic map is a polynomial mapping, often cited as an archetypal example of how chaotic behaviour can arise from very simple non-linear dynamical equations. The map was popularized in a seminal 1976 paper by the Australian biologist Robert May,[13] in part as a discrete-time demographic model analogous to the logistic equation first created by Pierre François Verhulst. The difference equation is intended to capture the two effects of reproduction and starvation.

The Feigenbaum constants in bifurcation theory are analogous to π in geometry and e in calculus. Neither of them is known to be irrational or even transcendental. However proofs of their universality exist.[14]

The respective approximate numeric values of δ and α are:

Mathematical curiosities

[edit]Simple representatives of sets of numbers

[edit]Some constants, such as the square root of 2, Liouville's constant and Champernowne constant:

are not important mathematical invariants but retain interest being simple representatives of special sets of numbers, the irrational numbers,[16] the transcendental numbers[17] and the normal numbers (in base 10)[18] respectively. The discovery of the irrational numbers is usually attributed to the Pythagorean Hippasus of Metapontum who proved, most likely geometrically, the irrationality of the square root of 2. As for Liouville's constant, named after French mathematician Joseph Liouville, it was the first number to be proven transcendental.[19]

Chaitin's constant Ω

[edit]In the computer science subfield of algorithmic information theory, Chaitin's constant is the real number representing the probability that a randomly chosen Turing machine will halt, formed from a construction due to Argentine-American mathematician and computer scientist Gregory Chaitin. Chaitin's constant, though not being computable, has been proven to be transcendental and normal. Chaitin's constant is not universal, depending heavily on the numerical encoding used for Turing machines; however, its interesting properties are independent of the encoding.

Notation

[edit]Representing constants

[edit]It is common to express the numerical value of a constant by giving its decimal representation (or just the first few digits of it). For two reasons this representation may cause problems. First, even though rational numbers all have a finite or ever-repeating decimal expansion, irrational numbers don't have such an expression making them impossible to completely describe in this manner. Also, the decimal expansion of a number is not necessarily unique. For example, the two representations 0.999... and 1 are equivalent[20][21] in the sense that they represent the same number.

Calculating digits of the decimal expansion of constants has been a common enterprise for many centuries. For example, German mathematician Ludolph van Ceulen of the 16th century spent a major part of his life calculating the first 35 digits of pi.[22] Using computers and supercomputers, some of the mathematical constants, including π, e, and the square root of 2, have been computed to more than one hundred billion digits. Fast algorithms have been developed, some of which — as for Apéry's constant — are unexpectedly fast.

Some constants differ so much from the usual kind that a new notation has been invented to represent them reasonably. Graham's number illustrates this as Knuth's up-arrow notation is used.[23][24]

It may be of interest to represent them using continued fractions to perform various studies, including statistical analysis. Many mathematical constants have an analytic form, that is they can be constructed using well-known operations that lend themselves readily to calculation. Not all constants have known analytic forms, though; Grossman's constant[25] and Foias' constant[26] are examples.

Symbolizing and naming of constants

[edit]Symbolizing constants with letters is a frequent means of making the notation more concise. A common convention, instigated by René Descartes in the 17th century and Leonhard Euler in the 18th century, is to use lower case letters from the beginning of the Latin alphabet or the Greek alphabet when dealing with constants in general.

However, for more important constants, the symbols may be more complex and have an extra letter, an asterisk, a number, a lemniscate or use different alphabets such as Hebrew, Cyrillic or Gothic.[24]

Embree–Trefethen constant

Brun's constant for twin prime

Champernowne constants

cardinal number aleph naught

Sometimes, the symbol representing a constant is a whole word. For example, American mathematician Edward Kasner's 9-year-old nephew coined the names googol and googolplex.[24][27]

Other names are either related to the meaning of the constant (universal parabolic constant, twin prime constant, ...) or to a specific person (Sierpiński's constant, Josephson constant, and so on).

Selected mathematical constants

[edit]| Symbol | Value | Name | Rational | Algebraic | Period | Field | Known digits | First described |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0000000000... | Zero | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Gen | all | c. 500 BC | |

| 1.0000000000... | One | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Gen | all | Prehistory | |

| 0 + 1i | Imaginary unit | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | Gen, Ana | all | 1500s | |

| 3.1415926535... | Pi, Archimedes' constant | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | Gen, Ana | 2.0 × 1014[28] | c. 2600 BC | |

| 2.7182818284... | e, Euler's number | ✗ | ✗ | ? | Gen, Ana | 3.5 × 1013[28] | 1618 | |

| 1.4142135623... | Square root of 2, Pythagoras' constant | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | Gen | 2.0 × 1013[28] | c. 800 BC | |

| 1.7320508075... | Square root of 3, Theodorus' constant | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | Gen | 3.1 × 1012[28] | c. 800 BC | |

| 1.6180339887... | Golden ratio | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | Gen | 2.0 × 1013[28] | c. 200 BC | |

| 1.2599210498... | Cube root of two | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | Gen | 1.0 × 1012[28] | c. 380 BC | |

| 0.6931471805... | Natural logarithm of 2 | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | Gen, Ana | 3.0 × 1012[28] | 1619 | |

| 0.5772156649... | Euler–Mascheroni constant | ? | ? | ? | Gen, NuT | 1.3 × 1012[28] | 1735 | |

| 1.2020569031... | Apéry's constant | ✗ | ? | ✓ | Ana | 2.0 × 1012[28] | 1780 | |

| 0.9159655941... | Catalan's constant | ? | ? | ✓ | Com | 1.2 × 1012[28] | 1832 | |

| 2.6220575542... | Lemniscate constant | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | Ana | 1.2 × 1012[28] | 1700s | |

| 1.2824271291... | Glaisher–Kinkelin constant | ? | ? | ? | Ana | 5.0 × 105[29] | 1860 | |

| 2.6854520010... | Khinchin's constant | ? | ? | ? | NuT | 1.1 × 105[30] | 1934 | |

| 4.6692016091... | Feigenbaum constants | ? | ? | ? | ChT | 1,000+[31] | 1975 | |

| 2.5029078750... | ? | ? | ? | 1,000+[32] | 1979 |

Abbreviations used:

- Gen – General, NuT – Number theory, ChT – Chaos theory, Com – Combinatorics, Ana – Mathematical analysis

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Constant". mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2020-08-08.

- ^ Grinstead, C.M.; Snell, J.L. "Introduction to probability theory". p. 85. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2007-12-09.

- ^ Livio, Mario (2002). The Golden Ratio: The Story of Phi, The World's Most Astonishing Number. New York: Broadway Books. ISBN 0-7679-0815-5.

- ^ Tatersall, James (2005). Elementary number theory in nine chapters (2nd ed.).

- ^ "The Secret Life of Continued Fractions"

- ^ Fibonacci Numbers and Nature - Part 2 : Why is the Golden section the "best" arrangement?, from Dr. Ron Knott's Fibonacci Numbers and the Golden Section, retrieved 2012-11-29.

- ^ a b Finch, Steven (2003). Mathematical constants. Cambridge University Press. p. 67. ISBN 0-521-81805-2.

- ^ Simoson, Andrew (2023-03-01). "In Pursuit of Zeta-3". The Mathematical Intelligencer. 45 (1): 85–87. doi:10.1007/s00283-022-10184-z. ISSN 1866-7414.

- ^ Steven Finch. "Apéry's constant". MathWorld.

- ^ Wyse, A. B.; Mayall, N. U. (January 1942), "Distribution of Mass in the Spiral Nebulae Messier 31 and Messier 33.", The Astrophysical Journal, 95: 24–47, Bibcode:1942ApJ....95...24W, doi:10.1086/144370

- ^ Bailey, David H.; Borwein, Jonathan M.; Mattingly, Andrew; Wightwick, Glenn (2013), "The computation of previously inaccessible digits of and Catalan's constant", Notices of the American Mathematical Society, 60 (7): 844–854, doi:10.1090/noti1015, MR 3086394

- ^ Collet & Eckmann (1980). Iterated maps on the inerval as dynamical systems. Birkhauser. ISBN 3-7643-3026-0.

- ^ May, Robert (1976). Theoretical Ecology: Principles and Applications. Blackwell Scientific Publishers. ISBN 0-632-00768-0.

- ^ Lanford III, Oscar (1982). "A computer-assisted proof of the Feigenbaum conjectures". Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 6 (3): 427–434. doi:10.1090/S0273-0979-1982-15008-X.

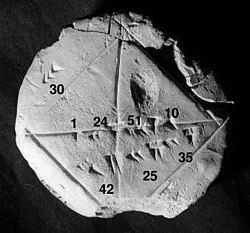

- ^ Fowler, David; Eleanor Robson (November 1998). "Square Root Approximations in Old Babylonian Mathematics: YBC 7289 in Context". Historia Mathematica. 25 (4): 368. doi:10.1006/hmat.1998.2209.

Photograph, illustration, and description of the root(2) tablet from the Yale Babylonian Collection

High resolution photographs, descriptions, and analysis of the root(2) tablet (YBC 7289) from the Yale Babylonian Collection - ^ Bogomolny, Alexander. "Square root of 2 is irrational".

- ^ Aubrey J. Kempner (Oct 1916). "On Transcendental Numbers". Transactions of the American Mathematical Society. 17 (4). Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, Vol. 17, No. 4: 476–482. doi:10.2307/1988833. JSTOR 1988833.

- ^ Champernowne, David (1933). "The Construction of Decimals Normal in the Scale of Ten". Journal of the London Mathematical Society. 8 (4): 254–260. doi:10.1112/jlms/s1-8.4.254.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Liouville's Constant". MathWorld.

- ^ Rudin, Walter (1976) [1953]. Principles of mathematical analysis (3e ed.). McGraw-Hill. p.61 theorem 3.26. ISBN 0-07-054235-X.

- ^ Stewart, James (1999). Calculus: Early transcendentals (4e ed.). Brooks/Cole. p. 706. ISBN 0-534-36298-2.

- ^ Ludolph van Ceulen Archived 2015-07-07 at the Wayback Machine – biography at the MacTutor History of Mathematics archive.

- ^ Knuth, Donald (1976). "Mathematics and Computer Science: Coping with Finiteness. Advances in Our Ability to Compute are Bringing Us Substantially Closer to Ultimate Limitations". Science. 194 (4271): 1235–1242. doi:10.1126/science.194.4271.1235. PMID 17797067. S2CID 1690489.

- ^ a b c "mathematical constants". Archived from the original on 2012-09-07. Retrieved 2007-11-27.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Grossman's constant". MathWorld.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Foias' constant". MathWorld.

- ^ Edward Kasner and James R. Newman (1989). Mathematics and the Imagination. Microsoft Press. p. 23.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Records set by y-cruncher". www.numberworld.org. Retrieved 2024-08-22.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Glaisher-Kinkelin Constant Digits". mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2024-10-05.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Khinchin's Constant Digits". mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2024-10-05.

- ^ "A006890 - OEIS". oeis.org. Retrieved 2024-08-22.

- ^ "A006891 - OEIS". oeis.org. Retrieved 2024-08-22.

External links

[edit]- Constants – from Wolfram MathWorld

- Inverse symbolic calculator (CECM, ISC) (tells you how a given number can be constructed from mathematical constants)

- On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences (OEIS)

- Simon Plouffe's inverter

- Steven Finch's page of mathematical constants (BROKEN LINK)

- Steven R. Finch, "Mathematical Constants," Encyclopedia of mathematics and its applications, Cambridge University Press (2003).

- Xavier Gourdon and Pascal Sebah's page of numbers, mathematical constants and algorithms

Mathematical constant

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Overview

Definition of a Mathematical Constant

A mathematical constant is a fixed, well-defined value that does not vary within mathematical expressions or contexts, typically representing a specific number of intrinsic interest across various branches of mathematics. These values are often denoted by dedicated symbols and arise from fundamental definitions, geometric properties, limiting processes, or solutions to equations, providing unchanging foundations for theorems and calculations. While mathematical constants are typically real numbers, the term can encompass important complex numbers in broader contexts.[1][2] In contrast to variables, which represent quantities that can take on different values depending on the situation or input, mathematical constants remain invariant and independent of any variables. Parameters, while appearing fixed within a single model or problem, differ from constants in that they can be adjusted or varied when considering different scenarios or generalizations, serving more as placeholders for specific choices rather than universally fixed entities.[6][7] Mathematical constants can emerge in diverse ways, reflecting their origins in mathematical structures. For instance, some arise purely from geometric definitions, such as π, the constant ratio of a circle's circumference to its diameter in Euclidean geometry. Others are explicitly defined to extend mathematical systems, like the imaginary unit , introduced as a solution to the equation , where . Additional constants emerge from analytical limits or infinite processes, exemplified by , which arises as the base of the natural exponential function through limiting expressions in calculus.[8]Properties and Classifications

Mathematical constants exhibit several fundamental properties that distinguish them from rational numbers and highlight their intrinsic complexity. A primary property is irrationality, meaning these constants have non-terminating, non-repeating decimal expansions and cannot be expressed as a ratio of integers.[9] For instance, constants like and are irrational, as their decimal representations continue indefinitely without pattern.[10] Another key property is transcendence, where a constant is not the root of any non-zero polynomial equation with rational coefficients, making it "transcend" algebraic structures.[11] Transcendental constants, such as and , are necessarily irrational but form a broader class.[11] Additionally, most mathematical constants are computable, meaning there exists an algorithm that can approximate them to arbitrary precision in finite steps, as formalized in computability theory.[12] Classifications of mathematical constants are based on their algebraic nature and domain. Algebraic constants are roots of polynomials with integer coefficients; for example, satisfies .[9] In contrast, transcendental constants evade such polynomial roots, encompassing numbers like and that arise in analytic contexts.[11] Complex constants, such as the imaginary unit (satisfying ), are algebraic within the complex numbers but extend classifications beyond reals.[9] Proofs of these properties often rely on advanced techniques in number theory. The Lindemann-Weierstrass theorem states that if are distinct algebraic numbers, then for algebraic , which implies the transcendence of (via Hermite's 1873 application) and (via Lindemann's 1882 use of ).[13] This theorem provides a cornerstone for establishing transcendence in exponential forms.[13] Mathematical constants frequently serve as invariants in key theorems across disciplines, preserving essential relations under transformations. In geometry, acts as an invariant ratio of circumference to diameter, underpinning theorems like those on circle areas.[10] In analysis, appears as a base for limits and series in theorems like the fundamental theorem of calculus.[10] In algebra, constants like the golden ratio invariant in Fibonacci recurrences and quadratic equations.[10]Historical Development

Ancient and Classical Constants

The earliest known mathematical constants emerged from ancient Greek inquiries into geometry and proportion, fundamentally shaping the understanding of numbers and reality. Around 500 BCE, the Pythagoreans, a philosophical school founded by Pythagoras of Samos (c. 570–495 BCE), discovered the constant through the application of the Pythagorean theorem to an isosceles right triangle with legs of length 1, yielding a hypotenuse of . This revelation came as a shock, as it demonstrated that could not be expressed as a ratio of whole numbers, challenging their core belief that all phenomena could be reduced to rational numerical relations. The proof of its irrationality, attributed to the Pythagorean Hippasus of Metapontum (c. 5th century BCE), proceeded by contradiction: assuming in lowest terms leads to both and being even, contradicting the assumption, thus establishing as irrational. Legend holds that Hippasus was punished—possibly drowned—for revealing this secret, underscoring the philosophical turmoil it caused within the sect.[14][15] In the 3rd century BCE, Archimedes of Syracuse advanced the study of constants with his approximation of , the ratio of a circle's circumference to its diameter, in his treatise Measurement of a Circle. Employing the method of exhaustion, Archimedes inscribed and circumscribed regular polygons around a circle of diameter 1, progressively increasing the number of sides from 6 (hexagons) to 96. This yielded tight bounds: , or approximately 3.1408 < < 3.1429, providing the most precise ancient estimate. Proofs of 's irrationality and transcendence came much later, with Johann Heinrich Lambert proving irrationality in 1761 using continued fractions and Ferdinand von Lindemann proving transcendence in 1882. Archimedes' polygonal approach not only quantified but also laid groundwork for integral calculus by squeezing bounds ever tighter.[16][3] Euclid of Alexandria (fl. 300 BCE) systematized geometric constants in his seminal work Elements, particularly through proportions derived from line divisions. In Book II, Proposition 11, Euclid described dividing a line segment at point in "extreme and mean ratio," where , defining the golden ratio . This constant appeared in constructions of regular pentagons, dodecahedrons, and icosahedrons across Books II, IV, and XIII, emphasizing its role in harmonious geometric figures. Although the Fibonacci sequence (1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, ...) was introduced centuries later by Leonardo of Pisa (Fibonacci) in 1202 CE, the ratios of consecutive terms converge to , a connection first noted in the 16th century but rooted in Euclid's proportional framework.[17] These constants profoundly influenced ancient philosophy and architecture, embodying cosmic harmony. The Pythagoreans viewed numbers as the essence of reality, with constants like and simple ratios (e.g., 2:1 for octaves) revealing the universe's musical order, where vibrating strings produced consonant intervals only at whole-number proportions—extending to the "harmony of the spheres," a metaphysical idea of celestial bodies moving in numerical rhythm. In architecture, Egyptian structures like the Great Pyramid of Giza (c. 2580–2560 BCE) exhibit proportions approximating (perimeter-to-height ratio ≈ 2) and (slope secant ≈ 1.618), but scholars debate intentionality, attributing them to practical ratios like 11:14 rather than deliberate constants. Nonetheless, such approximations highlight early intuitive grasp of these values in monumental design, bridging mathematics and cultural symbolism.[14][18]Modern Discoveries and Naming

The emergence of mathematical constants in the modern era, particularly from the 17th century onward, coincided with advancements in calculus and analysis, leading to formalized discoveries and systematic naming conventions. One of the earliest such constants arose in the context of compound interest. In 1683, Swiss mathematician Jacob Bernoulli identified the limit while investigating continuous compounding, approximating its value as 2.718 and recognizing its fundamental role in growth processes.[19] This constant, now known as Euler's number , was later denoted by the letter in a 1731 letter from Leonhard Euler to Christian Goldbach, where Euler explored its properties in exponential functions and natural logarithms.[19] Parallel developments in algebra during the 16th century laid groundwork for another key constant, the imaginary unit , which addressed solutions to equations like . Italian mathematicians, including Rafael Bombelli in his 1572 work Algebra, first employed square roots of negative numbers to solve cubic equations, treating them as formal tools despite their counterintuitive nature.[20] Euler formalized in 1777, integrating it into complex analysis and establishing its notation as a standard in mathematics.[21] In the 18th and 19th centuries, constants from infinite series and harmonic progressions gained prominence. Euler introduced the Euler-Mascheroni constant in his 1734 paper De Progressionibus harmonicis observationes, defining it as the difference between the harmonic series and the natural logarithm.[22] This constant, later symbolized by in honor of both Euler and Lorenzo Mascheroni's contributions to its computation, exemplifies the era's focus on analytic limits. By the 20th century, discoveries extended to zeta function values; French mathematician Roger Apéry proved the irrationality of in 1979, earning it the name Apéry's constant for its unexpected non-rational nature amid rational even-indexed zeta values.[23] Naming practices for these constants evolved to reflect discovery contexts, prioritizing eponyms, symbolic letters, and descriptors for clarity and attribution. Constants like and honor key figures such as Euler, while Apéry's constant directly commemorates its prover, a trend seen also in Mitchell Feigenbaum's 1975 discovery of the Feigenbaum constant in chaos theory's period-doubling bifurcations.[24] Greek letters, such as for the golden ratio or for the Euler-Mascheroni constant, became conventional for their availability beyond Latin alphabets and historical ties to analysis, as Mascheroni first used in 1790 computations.[25] Descriptive terms, like "imaginary unit," persisted for conceptual novelty, ensuring constants' integration into broader mathematical frameworks without ambiguity.[26]Fundamental Constants

Pythagoras' Constant (√2)

Pythagoras' constant, denoted , is defined as the positive real number that, when squared, equals 2, representing the length of the diagonal of a unit square with side length 1.[27] Its approximate decimal value is 1.414213562, making it the first known irrational number discovered in ancient mathematics.[27] The irrationality of was established by members of the Pythagorean school around the 5th century BCE, challenging the belief that all lengths could be expressed as ratios of integers. Legend attributes the discovery to Hippasus of Metapontum, who reportedly faced severe repercussions, including drowning, for revealing this "secret" that contradicted the Pythagorean doctrine that all is number.[15] The classical proof proceeds by contradiction: assume where and are coprime positive integers; then , implying is even (as is even), so for some integer ; substituting yields or , so is even, contradicting the assumption of coprimality. Thus, cannot be rational.[28] The continued fraction expansion of is , a periodic form characteristic of quadratic irrationals. This yields optimal rational approximations, or convergents, such as , , , and , which provide increasingly accurate estimates while satisfying .[27] In geometry, arises centrally in isosceles right triangles, known as 45-45-90 triangles, where the hypotenuse equals the leg length multiplied by , as derived from the Pythagorean theorem: for legs of length , the hypotenuse is . This relation underpins proofs of the Pythagorean theorem itself, such as those using similar triangles or area dissections, and extends to applications in coordinate geometry for distances like the line from to .[29]Archimedes' Constant (π)

Archimedes' constant, denoted by the Greek letter , is a fundamental mathematical constant defined as the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter in Euclidean geometry, expressed as . This ratio remains invariant for all circles regardless of size, with an approximate numerical value of . The constant arises naturally in the study of circles and spheres, underpinning formulas for their area () and volume (), where is the radius. Its irrational nature ensures that these geometric properties cannot be expressed exactly using finite algebraic operations on integers.[30][31] Early approximations of were achieved through geometric methods, notably by Archimedes of Syracuse in the 3rd century BCE. In his work Measurement of a Circle, Archimedes employed inscribed and circumscribed regular polygons with up to 96 sides to bound between and , yielding or approximately . This polygon exhaustion technique provided the first rigorous bounds, demonstrating 's value more precisely than prior estimates like the Babylonian approximation of 3.125. Centuries later, in the 17th century, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz derived an infinite series expansion using the arctangent function, given by This alternating series, independently discovered by James Gregory, offered a computational method for approximating to arbitrary precision, though it converges slowly.[32][33][34] The transcendental nature of —meaning it is not algebraic and thus not a root of any non-zero polynomial with rational coefficients—was established by Ferdinand von Lindemann in 1882 through his proof in Über die Ludolph'sche Zahl. Building on the Lindemann-Weierstrass theorem, which shows that implies the transcendence of via Euler's identity, this result resolved ancient questions like the impossibility of constructing a square with the same area as a given circle using straightedge and compass alone. Beyond geometry, is indispensable in analysis and physics. In trigonometry, it defines the period of sine and cosine functions over , essential for modeling periodic phenomena. Fourier series, which expand functions as sums of sines and cosines, incorporate in normalization factors, enabling applications in signal processing and solving partial differential equations for wave and heat propagation. In physics, appears in equations for circular orbits, oscillatory systems, and quantum wave functions, such as the time-independent Schrödinger equation for hydrogen atoms.[35][36][37][38]Euler's Number (e)

Euler's number, denoted , is a fundamental mathematical constant defined as the limit This limit arises from the concept of continuous compounding in interest calculations and represents the base of the natural exponential growth. Equivalently, can be expressed through its infinite series expansion where the factorial grows rapidly, ensuring rapid convergence of the series. These definitions highlight 's role as the unique base for which the exponential function aligns seamlessly with calculus operations. A key property of is that it serves as the base of the natural logarithm, , satisfying and for . The exponential function is distinctive because its derivative is itself: . This self-derivative property simplifies the solution of linear differential equations, making the eigenfunction of the differentiation operator. In 1815, Joseph Fourier proved is irrational using its series expansion, showing that assuming in lowest terms leads to a contradiction via partial sums and remainders bounded between 0 and 1 for sufficiently large denominators. Charles Hermite extended this in 1873 by proving 's transcendence, demonstrating it satisfies no nonzero polynomial equation with rational coefficients through approximations via integrals and polynomial identities.[39][40][41][42] The constant underpins numerous applications in analysis and applied mathematics. In differential equations, it models continuous growth and decay processes, such as population dynamics or radioactive decay, where solutions often take the form for growth rate . For instance, the equation has the explicit solution involving , directly leveraging the derivative property. In probability theory, appears in the probability density function of the normal distribution, which describes many natural phenomena due to the central limit theorem, with the exponential term ensuring the bell-shaped curve decays from the mean . These roles establish as indispensable for modeling real-world continuous processes.[43]The Golden Ratio (φ)

The golden ratio, denoted by the Greek letter φ (phi), is an irrational number defined algebraically as the positive root of the quadratic equation , given explicitly by . This value emerges from the condition where a line segment is divided into two parts such that the ratio of the whole to the longer part equals the ratio of the longer part to the shorter part. As an algebraic number of degree 2, φ satisfies minimal polynomial properties that distinguish it from transcendental constants, while its continued fraction expansion [1; 1, 1, 1, ...]—an infinite sequence of 1s—demonstrates its irrationality and makes it particularly resistant to rational approximations.[44] Geometrically, φ appears in the structure of regular pentagons and related figures, where the ratio of a diagonal to a side length equals φ exactly. For instance, in a regular pentagon with side length 1, the diagonals intersect such that each is divided in the golden ratio by the intersection point, a property that extends to pentagrams and decagons. This geometric recurrence underscores φ's role in symmetric polygons derived from the circle, as seen in the vertex angles of 36° and 72° in isosceles triangles associated with pentagons. Additionally, the limit of the ratios of consecutive terms in the Fibonacci sequence—defined by F_1 = 1, F_2 = 1, and F_n = F_{n-1} + F_{n-2} for n > 2—converges to φ, linking it to recursive growth patterns: . In nature, phyllotaxis, the spiral arrangement of leaves, florets, or seeds in plants like sunflowers and pinecones, often adheres to the golden angle of approximately 137.5° (derived as ), which optimizes packing density and light interception through biophysical efficiency.[44][45][46] Culturally, φ has influenced artistic and architectural design for its perceived aesthetic harmony, appearing in proportions that evoke balance and beauty. For example, dimensions of the Parthenon in Athens, constructed between 447 and 432 BCE, have been interpreted to incorporate golden ratios in facade widths to heights and column spacings, though such attributions are sometimes debated as retrospective impositions rather than intentional designs. In modern contexts, φ features in optimization algorithms, notably the golden-section search method, which iteratively narrows an interval to locate the extremum of a unimodal function by dividing segments in the ratio φ:1, achieving efficiency comparable to ternary search with fewer evaluations. This application highlights φ's utility in numerical methods for solving real-world problems in engineering and computer science.[44][47][48]The Imaginary Unit (i)

The imaginary unit is defined as the positive square root of , satisfying the equation . This constant extends the real number system to the field of complex numbers, where elements are expressed as with real coefficients and . The powers of follow a periodic cycle of length four: , , , , after which the pattern repeats, providing a foundational structure for complex arithmetic.[49] The concept of the imaginary unit originated in the 16th century amid efforts to solve cubic equations. In 1572, Italian engineer Rafael Bombelli formally introduced complex numbers in his treatise L'Algebra, employing them as an algebraic tool despite their counterintuitive nature, which he termed "sophistic" or imaginary.[50] Initial resistance persisted, but by the 19th century, complex numbers achieved full integration into mathematical analysis. Augustin-Louis Cauchy laid key groundwork in his 1814 memoir on definite integrals, where he extended integration techniques to complex variables, establishing rigorous foundations for complex function theory.[51] Carl Friedrich Gauss further solidified their acceptance, coining the term "complex numbers" in 1831 and proving the Fundamental Theorem of Algebra, which relies on the completeness of the complex plane.[52] A hallmark property of is Euler's formula, , which unifies exponential and trigonometric functions in the complex domain. Setting yields Euler's identity, , elegantly linking , , , 1, and 0. This relation, first published by Leonhard Euler in 1748, can be outlined via Taylor series expansions: the series for is , separating into real and imaginary parts as , matching the known series for and .[53] Although is algebraic as a root of , its role in this identity connects it to the transcendental constants and .[54] The imaginary unit enables the solution of polynomial equations over the complexes, as per the Fundamental Theorem of Algebra: every non-constant polynomial with complex coefficients possesses exactly as many roots (counting multiplicity) as its degree, all within the complex numbers.[52] In electrical engineering, underpins phasor analysis for alternating current circuits, representing sinusoidal signals as complex vectors to compute impedances, phase differences, and power via operations like addition and multiplication in the complex plane.[55] In quantum mechanics, is indispensable in the time-dependent Schrödinger equation, , where it governs the unitary evolution of the wave function , ensuring probability conservation and capturing interference phenomena.Advanced Analytic Constants

Euler-Mascheroni Constant (γ)

The Euler-Mascheroni constant, denoted by γ, is defined as the limit where is the -th harmonic number.[5] This constant arises naturally from the divergence of the harmonic series, capturing the difference between the partial sum of the reciprocals and the natural logarithm. Its numerical value is approximately 0.5772156649015328606065120900824024310421.[5] Leonhard Euler first introduced this constant in 1734 in his paper "De Progressionibus harmonicis observationes," where he explored properties of harmonic progressions and computed early approximations.[5] Euler conjectured that γ is irrational, a belief that persists among mathematicians, though no proof has been established as of 2025; moreover, its transcendence remains an open question.[5] One integral representation of γ is understood in the sense of a principal value to handle the divergences at both ends.[5] This form highlights γ's connection to exponential and logarithmic behaviors, facilitating analytic continuations and series expansions in various contexts. In the theory of the gamma function Γ(z), γ appears as the negative of the digamma function at 1, γ = -ψ(1), where ψ(z) = Γ'(z)/Γ(z), providing a key link to special functions and asymptotic expansions.[5] Similarly, in number theory, γ features in the asymptotics of the prime number theorem through Mertens' theorems; for instance, the product over primes p ≤ x of (1 - 1/p) behaves as e^{-γ} / \ln x as x → ∞, quantifying the distribution of primes.[5]Apéry's Constant (ζ(3))

Apéry's constant, denoted ζ(3), is the value of the Riemann zeta function at s=3, defined as the infinite series ∑_{n=1}^∞ 1/n^3.[56] This constant approximates to 1.2020569032 and represents the sum of the reciprocals of the cubes of positive integers.[56] In 1979, Roger Apéry proved the irrationality of ζ(3) using a method involving sequences and linear recurrences that lead to a continued fraction expansion. The proof constructs integer sequences a_n and related terms b_n approximating ζ(3), satisfying a three-term recurrence relation that demonstrates ζ(3) cannot be rational, as the approximations converge too rapidly for a rational number.[57] This result was groundbreaking, as prior to Apéry, the irrationality of ζ(3) was an open question despite known closed forms for even zeta values. ζ(3) connects to polylogarithms as the special case Li_3(1), where the polylogarithm Li_s(z) generalizes the series to ∑ z^n / n^s, and appears in multiple zeta values as a depth-one term. In quantum field theory, ζ(3) arises in Feynman diagram evaluations, such as contributions to the electron's anomalous magnetic moment at third order in the fine-structure constant and periods of massless φ^4 theory graphs at six loops.[58] High-precision computations of ζ(3) employ accelerated series derived from Wilf-Zeilberger pairs, yielding rapidly convergent hypergeometric representations that surpass the slow convergence of the defining series.[59] For instance, one such family includes terms like ∑ (-1)^{n-1} (56n^2 - 32n + 5) / [n^3 (2n choose n)^2 (3n choose n) (2n-1)^2 ], enabling evaluation to thousands of decimal places efficiently via binary splitting or asymptotic expansions.[59][56]Catalan's Constant (G)

Catalan's constant, denoted by , is defined by the infinite alternating series which converges to approximately 0.915965594.[60] This series was introduced by the Belgian mathematician Eugène Charles Catalan in a 1865 memoir where he provided equivalent series expansions and integral expressions for its computation.[61] Despite extensive study, it remains an open problem whether is irrational, a conjecture that has persisted since its discovery and is unproven as of 2025.[62] Alternative representations of include its expression as the value of the Dirichlet beta function at 2, , where .[60] It also arises in integral forms derived from Fourier series expansions, such as which connects to the Fourier series of periodic functions involving arctangents.[63] These representations highlight 's ties to analytic number theory and special functions. In applications, frequently appears in combinatorial estimates, such as asymptotic approximations for the number of self-avoiding walks or alternating sign matrices, where it provides precise corrections in summation formulas.[60] Additionally, it emerges in the evaluation of certain elliptic integrals, including complete elliptic integrals of the first kind in parametric forms that yield series involving for specific moduli.Dynamical and Special Constants

Feigenbaum Constants (α and δ)

The Feigenbaum constants, denoted δ and α, arise in the study of period-doubling bifurcations within nonlinear dynamical systems, particularly in the logistic map defined by the iteration , where and is a control parameter. The constant δ, approximately 4.6692016091, represents the universal accumulation rate of bifurcation points, given by the limit , where is the value of at which the system undergoes a period-doubling bifurcation to period . Similarly, α, approximately 2.5029078751, is the scaling factor describing the geometric contraction of the bifurcation intervals near the onset of chaos, relating the widths of successive "tines" in the bifurcation diagram.[24] These constants were discovered by physicist Mitchell Feigenbaum in 1975 through numerical computations on a programmable calculator, while exploring the logistic map and other unimodal maps. Feigenbaum observed that the ratios of bifurcation intervals converged to the same value regardless of the specific form of the nonlinear map, a phenomenon he formalized in his seminal 1978 paper, establishing quantitative universality in the transition to chaos via period doubling. This universality holds for a broad class of one-dimensional maps with a quadratic maximum, independent of fine details such as the exact shape of the nonlinearity.[64][65] Both δ and α are irrational and believed to be transcendental, though this remains unproven despite extensive computation of their decimal expansions to millions of digits. Their independence from map-specific features underscores a deep structural similarity in the renormalization group approach to chaotic attractors, where successive rescalings reveal self-similar patterns governed by these fixed-point values. Computations confirm their appearance across diverse quadratic maps, reinforcing their role as invariants in bifurcation theory.[66][67] The Feigenbaum constants find applications in modeling complex behaviors in dynamical systems, including the prediction of chaos onset in fluid turbulence, where period-doubling cascades mimic instabilities in flows like Taylor-Couette systems. They also inform analyses of electronic circuits exhibiting chaotic oscillations and chemical reaction networks, providing quantitative tools to characterize scaling near critical parameters without relying on system-specific simulations.[68]Chaitin's Constant (Ω)

Chaitin's constant, denoted , is a real number between 0 and 1 that represents the probability that a randomly generated program for a universal prefix-free Turing machine will halt. It is formally defined as the infinite sum where is the set of all halting self-delimiting (prefix-free) programs for the machine, and denotes the length of in bits. This construction encodes the total measure of all programs that terminate, leveraging the Kraft inequality to ensure the sum converges to a value less than or equal to 1.[69] Introduced by Gregory J. Chaitin in his 1971 presentation at the Courant Institute Symposium on Computational Complexity, the constant was fully detailed in his subsequent publication, where it served as a tool to explore the boundaries of formal axiomatic systems. Chaitin linked to Gödel's incompleteness theorems by demonstrating an information-theoretic reformulation: any consistent formal system with limited descriptive complexity cannot prove the halting of sufficiently many programs, thereby failing to determine more than a finite prefix of 's binary expansion. This connection arises because the initial segments of reveal whether specific programs halt, directly tying the constant to undecidable propositions in arithmetic.[69] possesses profound properties in algorithmic information theory. It is uncomputable, as an algorithm to compute its digits would enable solving the halting problem for arbitrary programs by checking convergence against partial sums. Furthermore, is Martin-Löf random (algorithmically random), meaning its binary expansion cannot be compressed by any computable process and exhibits no discernible patterns beyond pure chance; this randomness implies that is a normal number in base 2, with every finite sequence of bits appearing with the expected frequency. Being uncomputable, is also transcendental, as all algebraic numbers admit computable approximations to arbitrary precision.[69] The implications of extend to the foundations of mathematics and computation, highlighting inherent limitations in formal reasoning. In Kolmogorov complexity terms, the bits of represent irreducible facts about program behavior, underscoring that no theory can capture the full complexity of halting without exceeding its own informational bounds. This has influenced developments in randomness theory, showing how uncomputability manifests in concrete numerical form and reinforcing the incompleteness of any sufficiently powerful axiomatic system.[69]Representatives of Number Sets

Mathematical constants known as representatives of number sets are specially constructed real numbers that exemplify defining properties of vast infinite classes, such as the transcendentals or normal numbers, thereby aiding in the demonstration of their structural characteristics within the real line. The Champernowne constant, , exemplifies normal numbers through its explicit concatenation of the base-10 representations of all positive integers.[70] This construction ensures that every possible finite sequence of digits appears in its decimal expansion with asymptotic frequency for sequences of length , establishing its normality in base 10.[70] Kurt Mahler later proved that is transcendental, confirming its irrationality beyond mere algebraic considerations. As a constructed normal transcendental, it supports conjectures positing that almost all real numbers—specifically, those in the sense of Lebesgue measure—are normal, providing a tangible counterpoint to the rarity of non-normal irrationals like certain algebraic constants. The Liouville constant, , serves as a prototype for Liouville numbers, a subclass of transcendentals built via an ad hoc series to violate bounds on rational approximations achievable by algebraic numbers. Joseph Liouville designed this sum, placing a 1 at decimal position for each and zeros elsewhere, to ensure denominators in its partial sums grow slower than any algebraic number of fixed degree permits under his own approximation theorem. This renders transcendental by construction, as its rational approximations satisfy for arbitrarily large , a property impossible for algebraic irrationals. These representatives underscore the density of transcendentals in the reals: the set of Liouville numbers, including constants like , forms a dense subset, implying transcendentals are both uncountable and prevalent across intervals.[71] Champernowne's concatenation method highlights algorithmic constructions for normality, while Liouville's factorial series illustrates tailored sums for transcendence proofs, both enabling targeted demonstrations of infinite set properties without relying on uncomputable elements.Notation and Computation

Symbolization and Naming Conventions

Mathematical constants are frequently denoted using symbols from the Greek alphabet to distinguish them from variables and other elements in equations, a convention that leverages the rich symbolic tradition of ancient Greek mathematics while accommodating the needs of modern notation. For instance, the circle constant is represented by the lowercase Greek letter π, introduced by Welsh mathematician William Jones in 1706 to signify the ratio of a circle's circumference to its diameter, drawing from the Greek word περίφερεια (periphery) or περίμετρος (perimeter).[25] Similarly, the golden ratio employs the lowercase φ, proposed by American mathematician Mark Barr in the early 20th century, likely alluding to the ancient Greek sculptor Phidias, whose works exemplified proportional harmony associated with this value.[25] The Euler-Mascheroni constant uses the lowercase γ, first adopted by Italian geometer Lorenzo Mascheroni in his 1790 work Adnotationes ad calculum integralem Euleri, though Leonhard Euler had earlier referred to it with the letter C.[25] Typographic conventions further differentiate constants through font styles: according to ISO 80000-2, mathematical constants such as , , and should be set in upright (Roman) type to avoid confusion with italicized variables, ensuring clarity in printed and digital formats.[72] Boldface or other emphases are occasionally used in multivariable contexts or to highlight specific instances, but these are not universal and depend on the publishing standards of the discipline. Naming conventions for mathematical constants vary, reflecting their discovery, properties, or utility, with eponyms, descriptive terms, and functional designations being prevalent. Eponyms honor discoverers or key contributors, as seen in "Euler's number" , introduced by Leonhard Euler in 1728 for the base of the natural logarithm, chosen possibly as an unused vowel or abbreviation for "exponential."[25] Descriptive names evoke inherent qualities, such as "golden ratio" for φ, emphasizing its aesthetically pleasing proportions in geometry and nature. Functional names tie the constant to defining operations, like the Riemann zeta function , where the uppercase Ζ (later lowercase ζ) was selected by Bernhard Riemann in 1859 to denote the infinite series , facilitating analytic number theory. The evolution of these symbolization practices transitioned from verbal descriptions in ancient and medieval texts—where constants like π were expressed in words such as "the ratio of the circumference to the diameter"—to compact symbolic notation, accelerated in the 1700s by the printing press and efforts of mathematicians like Euler, who standardized many forms in works such as his 1748 Introductio in analysin infinitorum.[25] This period marked a shift toward universality, reducing ambiguity and enabling broader dissemination across European mathematical traditions. Modern conventions, codified in standards like ISO 80000-2 since 2009, prioritize unambiguous typography and consistent usage to support international collaboration, prohibiting overloaded symbols and recommending upright fonts for fixed constants to maintain precision in complex expressions.[72]Approximation and Representation Methods

Mathematical constants are approximated using various analytical techniques that leverage their integral representations or recursive properties. Series expansions, particularly those derived from Taylor or Fourier series, provide efficient ways to compute values to arbitrary precision. For instance, Machin-like formulas express constants like π as linear combinations of arctangent terms, which can be expanded using the Leibniz series for arctan(x) = ∑ (-1)^n x^{2n+1}/(2n+1) for |x| < 1, enabling rapid convergence through terms with small arguments.[73] Continued fractions offer another powerful method, representing constants as infinite nested fractions [a_0; a_1, a_2, ...], where the convergents provide optimal rational approximations with controlled denominators, useful for bounding errors in diophantine approximations.[74] Binary splitting enhances the computation of hypergeometric series by recursively dividing the sum into binary tree structures, minimizing intermediate precision loss and arithmetic operations, which is particularly effective for constants like π or the Riemann zeta function at integer arguments. The Chudnovsky algorithm, a rapidly converging series based on elliptic integrals, has been instrumental in achieving record-breaking precision for π. As of April 2025, π has been computed to 300 trillion decimal digits using this method on optimized software like y-cruncher, surpassing previous benchmarks and demonstrating the scalability of such algorithms on modern hardware. These computations often incorporate error bounds derived from the remainder terms in the series; for example, in alternating series expansions, the error is less than the first omitted term, providing rigorous guarantees on accuracy without full evaluation.[75] Constants are represented in multiple number systems to suit different computational or theoretical needs. Decimal expansions are standard for real-valued constants, offering intuitive readability, while hexadecimal representations facilitate binary machine arithmetic, reducing conversion overhead in programming. In number theory, p-adic representations extend constants into completions of the rationals at prime p, written as formal series ∑ a_k p^k with a_k in {0, ..., p-1} converging in the p-adic metric, enabling analysis of local properties like those of π in p-adic fields. Approximations in these systems include explicit error bounds, such as the p-adic valuation providing the exact order of precision. High-precision computations are supported by specialized software libraries. The Wolfram Mathematica system evaluates constants like π or e to thousands or millions of digits using built-in functions such as N[Pi, dps], incorporating advanced algorithms for arbitrary-precision arithmetic.[76] Similarly, the mpmath Python library implements multiprecision floating-point operations, with lazy evaluation of constants via mpmath.pi() or mpmath.e(), allowing users to specify decimal places and supporting series-based evaluations for research applications.[77]Selected Constants Table

Irrational and Transcendental Constants

The following table lists selected irrational and transcendental mathematical constants, including their approximate values to 10 decimal places, established or conjectured statuses regarding irrationality and transcendence (as of 2025), and references to relevant sections in this encyclopedia entry for further details.| Constant | Symbol | Approximate Value | Status | Source Section Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Square root of 2 | √2 | 1.4142135624 | Irrational (algebraic) | Representatives of Number Sets |

| Pi | π | 3.1415926536 | Transcendental | Archimedes' Constant (π) |

| Euler's number | e | 2.7182818285 | Transcendental | Euler's Number (e) |

| Golden ratio | φ | 1.6180339887 | Irrational (algebraic) | The Golden Ratio (φ) |

| Euler-Mascheroni constant | γ | 0.5772156649 | Irrationality unproven | Euler-Mascheroni Constant (γ) |

| Apéry's constant | ζ(3) | 1.2020569032 | Irrational (transcendence unproven) | Apéry's Constant (ζ(3)) |

| Catalan's constant | G | 0.9159655942 | Irrationality unproven | Catalan's Constant (G) |

| Brun's constant | B₂ | 1.9021605831 | Irrationality unproven | Advanced Analytic Constants |

| Khinchin's constant | K | 2.6854520010 | Irrationality unproven | Advanced Analytic Constants |

Other Notable Constants

The following table presents selected other notable mathematical constants arising from dynamical systems, concatenated sequences, logarithmic integrals, and specialized series expansions. These constants are distinct from the primary irrational and transcendental ones, often emerging in contexts like chaos theory, number construction, and analytic number theory.| Symbol | Approximate Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| δ | 4.669201609102990 | The first Feigenbaum constant, representing the universal ratio of distances between successive period-doubling bifurcations in nonlinear maps approaching chaos, as derived from renormalization group analysis of iterative functions.[24] |

| α | 2.502907875095893 | The second Feigenbaum constant, quantifying the scaling factor between distances of successive elements in period-doubled attractors near the onset of chaos in one-dimensional maps.[24] |

| C_{10} | 0.123456789101112... | Champernowne's constant in base 10, constructed by concatenating the decimal representations of positive integers in order, proven to be normal (every digit sequence appears with equal frequency) and transcendental.[78] |

| μ | 1.451369234883381 | Soldner's constant, the unique positive real number where the logarithmic integral li(μ) = 0, arising in the analysis of the prime number theorem via the integral representation li(x) = ∫_0^x dt / ln t (principal value).[79] |

| B | 1.456074948582690 | Backhouse's constant, the limit of the absolute value of the ratio of consecutive coefficients q_{n+1}/q_n in the power series Q(x) = 1/P(x) = ∑ q_k x^k, where P(x) = 1 + ∑_{k=1}^∞ p_k x^k and p_k is the kth prime, connecting to the radius of convergence of prime-related series.[80] |

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\gamma &=\lim _{n\to \infty }\left(-\ln n+\sum _{k=1}^{n}{\frac {1}{k}}\right)\\[5px]\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b69917b4e04047078b06e12f4259da5e2bea524d)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{3}]{2}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9ca071ab504481c2bb76081aacb03f5519930710)