Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Greco-Roman world

View on WikipediaThis article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (November 2015) |

The Greco-Roman world /ˌɡriːkoʊˈroʊmən, ˌɡrɛkoʊ-/, also Greco-Roman civilization, Greco-Roman culture or Greco-Latin culture (spelled Græco-Roman or Graeco-Roman in British English), as understood by modern scholars and writers, includes the geographical regions and countries that culturally—and so historically—were directly and intimately influenced by the language, culture, government and religion of the Ancient Greeks and Romans. A better-known term is classical antiquity. In exact terms the area refers to the "Mediterranean world", the extensive tracts of land centered on the Mediterranean and Black Sea basins, the "swimming pool and spa" of the Greeks and the Romans, in which those peoples' cultural perceptions, ideas, and sensitivities became dominant in classical antiquity.

That process was aided by the universal adoption of Greek as the language of intellectual culture and commerce in the Eastern Mediterranean and of Latin as the language of public administration and of forensic advocacy, especially in the Western Mediterranean.

Greek and Latin were never the native languages of many or most of the rural peasants, who formed the great majority of the Roman Empire's population. However, they became the languages of the urban and cosmopolitan elites and the Empire's lingua franca for those who lived within the large territories and populations outside the Macedonian settlements and the Roman colonies. All Roman citizens of note and accomplishment, regardless of their ethnic extractions, spoke and wrote in Greek or Latin. Examples include the Roman jurist and imperial chancellor Ulpian of Phoenician origin; the mathematician and geographer Claudius Ptolemy of Greco-Egyptian ethnicity; and the theologian Augustine of Berber origin. Note too the historian Josephus Flavius, who was of Jewish origin but spoke and wrote in Greek.[citation needed]

Geographic extent

[edit]

Based on the above definition, the "cores" of the Greco-Roman world can be confidently stated to have been the coasts of the Mediterranean Sea, specifically the Italian Peninsula, Greece, Cyprus, the Iberian Peninsula (Spain, Portugal and Andorra), the Anatolian Peninsula (modern-day Turkey), Gaul (modern-day France), the Syrian region (modern-day Levantine countries, Central and Northern Syria, Lebanon, Israel and Palestine), Egypt and Roman Africa (corresponding to modern-day Tunisia, Eastern Algeria and Western Libya). Occupying the periphery of that world were the so-called "Roman Germany" (the modern-day Alpine countries of Austria and Switzerland and the Agri Decumates, southwestern Germany), the Illyricum (modern-day Northern Albania, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina and the coast of Croatia), the Macedonian region, Thrace (corresponding to modern-day Southeastern Bulgaria, Northeastern Greece and the European portion of Turkey), Moesia (roughly corresponding to modern-day Central Serbia, Kosovo, Northern Macedonia, Northern Bulgaria and Romanian Dobrudja), and Pannonia (corresponding to modern-day Western Hungary, the Austrian Länder of Burgenland, Eastern Slovenia and Northern Serbia).

Also included were Dacia (roughly corresponding to modern-day Romania and Moldavia), Nubia (a region roughly corresponding to the far south of Egypt and modern-day Northern Sudan), Mauretania (corresponding to modern-day Morocco, Western Algeria and Northern Mauritania), Arabia Petraea (corresponding to modern-day Hejaz region of Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Southern Syria and Egypt's Sinai Peninsula), and the Tauric Chersonesus (modern-day Crimea and the coast of Ukraine).

The Greco-Roman world had another "world" or empire to its east, the Persians, with which there was constant interaction: Xenophon's Anabasis (the 'March Upcountry'), the Greco-Persian wars, the famous battles of Marathon and Salamis, the Greek tragedy The Persians by Aeschylus, Alexander the Great's defeat of the Persian emperor Darius III and conquest of the Persian empire, or the later Roman generals' difficulties with the Persian armies, such as Pompey the Great, and of Marcus Licinius Crassus (conqueror of the slave general Spartacus), who was defeated in the field by a Persian force and was beheaded by them.[1]

Culture

[edit]In the schools of art, philosophy, and rhetoric, the foundations of education were transmitted throughout the lands of Greek and Roman rule. Within its educated class, spanning all of the "Greco-Roman" eras, the testimony of literary borrowings and influences are overwhelming proofs of a mantle of mutual knowledge. For example, several hundred papyrus volumes found in a Roman villa at Herculaneum are in Greek. The lives of Cicero and Julius Caesar are examples of Romans who frequented schools in Greece.

The installation, both in Greek and Latin, of Augustus's monumental eulogy, the Res Gestae, exemplifies the official recognition of the dual vehicles for the common culture. The familiarity of figures from Roman legend and history in the Parallel Lives by Plutarch is one example of the extent to which "universal history" was then synonymous with the accomplishments of famous Latins and Hellenes. Most educated Romans were likely bilingual in Greek and Latin.

Architecture

[edit]Graeco-Roman architecture in the Roman world followed the principles and styles that had been established by ancient Greece. That era's most representative building was the temple. Other prominent structures that represented that style included government buildings like the Roman Senate. The three primary styles of column design used in temples in classical Greece were Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian. Some examples of Doric architecture are the Parthenon and the Temple of Hephaestus in Athens, and the Erechtheum, next to the Parthenon, is Ionic.

Politics

[edit]Ancient Greece

[edit]

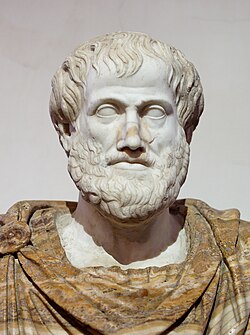

In Ancient Greece, several philosophers and historians analysed and described elements we now recognize as classical republicanism. Traditionally, the Greek concept of "politeia" was rendered into Latin as res publica. Consequently, political theory until relatively recently often used republic in the general sense of "regime". There is no single written expression or definition from this era that exactly corresponds with a modern understanding of the term "republic" but most of the essential features of the modern definition are present in the works of Plato, Aristotle, and Polybius. These include theories of mixed government and of civic virtue. For example, in The Republic, Plato places great emphasis on the importance of civic virtue (aiming for the good) together with personal virtue ('just man') on the part of the ideal rulers. Indeed, in Book V, Plato asserts that until rulers have the nature of philosophers (Socrates) or philosophers become the rulers, there can be no civic peace or happiness.[2]

A number of Ancient Greek city-states such as Athens and Sparta have been classified as "classical republics", because they featured extensive participation by the citizens in legislation and political decision-making. Aristotle considered Carthage to have been a republic as it had a political system similar to that of some of the Greek cities, notably Sparta, but avoided some of the defects that affected them.

Ancient Rome

[edit]

Both Livy, a Roman historian, and Plutarch, who is noted for his biographies and moral essays, described how Rome had developed its legislation, notably the transition from a kingdom to a republic, by following the example of the Greeks. Some of this history, composed more than 500 years after the events, with scant written sources to rely on, may be fictitious reconstruction.

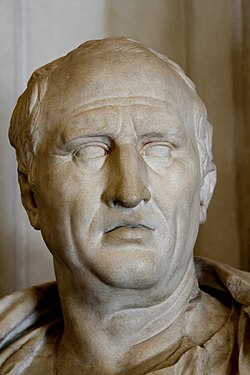

The Greek historian Polybius, writing in the mid-2nd century BCE, emphasized (in Book 6) the role played by the Roman Republic as an institutional form in the dramatic rise of Rome's hegemony over the Mediterranean. In his writing on the constitution of the Roman Republic,[3] Polybius described the system as being a "mixed" form of government. Specifically, Polybius described the Roman system as a mixture of monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy with the Roman Republic constituted in such a manner that it applied the strengths of each system to offset the weaknesses of the others. In his view, the mixed system of the Roman Republic provided the Romans with a much greater level of domestic tranquillity than would have been experienced under another form of government. Furthermore, Polybius argued, the comparative level of domestic tranquillity the Romans enjoyed allowed them to conquer the Mediterranean. Polybius exerted a great influence on Cicero as he wrote his politico-philosophical works in the 1st century BCE. In one of these works, De re publica, Cicero linked the Roman concept of res publica to the Greek politeia.

The modern term "republic", despite its derivation, is not synonymous with the Roman res publica.[4] Among the several meanings of the term res publica, it is most often translated "republic" where the Latin expression refers to the Roman state, and its form of government, between the era of the Kings and the era of the Emperors. This Roman Republic would, by a modern understanding of the word, still be defined as a true republic, even if not coinciding entirely. Thus, Enlightenment philosophers saw the Roman Republic as an ideal system because it included features like a systematic separation of powers.

Romans still called their state "Res Publica" in the era of the early emperors because, on the surface, the organization of the state had been preserved by the first emperors without significant alteration. Several offices from the Republican era, held by individuals, were combined under the control of a single person. These changes became permanent, and gradually conferred sovereignty on the Emperor.

Cicero's description of the ideal state, in De re Publica, does not equate to a modern-day "republic"; it is more like enlightened absolutism. His philosophical works were influential when Enlightenment philosophers such as Voltaire developed their political concepts.

In its classical meaning, a republic was any stable well-governed political community. Both Plato and Aristotle identified three forms of government: democracy, aristocracy, and monarchy. First Plato and Aristotle, and then Polybius and Cicero, held that the ideal republic is a mixture of these three forms of government. The writers of the Renaissance embraced this notion.

Cicero expressed reservations concerning the republican form of government. While in his theoretical works he defended monarchy, or at least a mixed monarchy/oligarchy, in his own political life, he generally opposed men, like Julius Caesar, Mark Antony, and Octavian, who were trying to realize such ideals. Eventually, that opposition led to his death and Cicero can be seen as a victim of his own Republican ideals.

Tacitus, a contemporary of Plutarch, was not concerned with whether a form of government could be analysed as a "republic" or a "monarchy".[5] He analysed how the powers accumulated by the early Julio-Claudian dynasty were all given by a State that was still notionally a republic. Nor was the Roman Republic "forced" to give away these powers: it did so freely and reasonably, certainly in Augustus' case, because of his many services to the state, freeing it from civil wars and disorder.

Tacitus was one of the first to ask whether such powers were given to the head of state because the citizens wanted to give them, or whether they were given for other reasons (for example, because one had a deified ancestor). The latter case led more easily to abuses of power. In Tacitus' opinion, the trend away from a true republic was irreversible only when Tiberius established power, shortly after Augustus' death in 14 CE (much later than most historians place the start of the Imperial form of government in Rome). By this time, too many principles defining some powers as "untouchable" had been implemented.[6]

By AD 211, with Caracalla's edict known as the Constitutio Antoniniana, and although one of the edict's main purposes was to increase tax revenue, all of the empire's free men became citizens with all the rights this entailed. As a result, even after the Fall of the Western Roman Empire, the people who remained within the lands (including Byzantium) that the empire comprised continued to call themselves Rhomaioi. (Hellenes had been referring to pagan, or non-Christian, Greeks until the Fourth Crusade.) Through attrition of Byzantine territory in the preceding 400 or so years from perceived friends and foes alike (Crusaders, Ottoman Turks, and others), Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire (the Eastern Roman Empire) fell to the Turks led by Mehmed II in 1453. There is a perception that these events led to the predecessor of Greek nationalism through the Ottoman era and even into modern times.

Religion

[edit]Greco-Roman mythology, sometimes called classical mythology, is the result of the syncretism between Roman and Greek myths, spanning the period of Great Greece at the end of Roman paganism. Along with philosophy and political theory, mythology is one of the greatest contributions of classical antiquity to Western society.[7]

From a historical point of view, early Christianity was born in the Greco-Roman world, which had a massive influence on Christian culture.[8]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Appian, The Civil Wars.

- ^ Paul A. Rahe, Republics ancient and modern: Classical Republicanism and the American Revolution (1992).

- ^ Polybius; Shuckburgh, Evelyn S. (2009). The Histories of Polybius. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9781139333740. ISBN 978-1139333740.

- ^ Mitchell, Thomas N. (2001). "Roman Republicanism: The Underrated Legacy". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 145 (2): 127–137. ISSN 0003-049X. JSTOR 1558267.

- ^ see for example Ann. IV, 32–33

- ^ Ann. I–VI

- ^ Entry on "mythology" in The Classical Tradition, edited by Anthony Grafton, Glenn W. Most, and Salvatore Settis (Harvard University Press, 2010), p. 614 and passim.

- ^ Marvin Perry, Myrna Chase, James Jacob, Margaret Jacob, Theodore H. Von Laue (1 January 2012). Western Civilization: Since 1400. Cengage Learning. p. XXIX. ISBN 978-1-111-83169-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Sources

[edit]- Sir William Smith (ed). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: Spottiswoode and Co, 1873.

- Simon Hornblower and Antony Spawforth (ed). Oxford Classical Dictionary. Oxford University Press, 2003.

- William Emerton Heitland. Agricola: A Study of Agriculture and Rustic Life in the Greco-Roman World from the Point of View of Labour. Cambridge: University Press, 1921

Greco-Roman world

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Chronology

Periodization and Key Phases

The Greco-Roman world is conventionally divided into chronological phases aligned with pivotal political, military, and cultural transformations in Greek and Roman societies, spanning approximately from the 8th century BCE to the 5th century CE in the West. This periodization emphasizes the transition from independent Greek city-states to Hellenistic kingdoms, followed by Roman hegemony, with key markers including the rise of the polis, Alexander the Great's conquests in 323 BCE, Rome's republican expansion after 509 BCE, and the imperial consolidation under Augustus in 27 BCE.[2][9] Such divisions facilitate analysis of continuity and rupture, though they reflect modern historiographical constructs influenced by ancient sources like Herodotus and Polybius, rather than rigid ancient categorizations.[10] Greek phases begin with the Archaic period (c. 800–480 BCE), during which post-Dark Age recovery led to the formation of poleis, alphabetic literacy by c. 750 BCE, and colonial foundations across the Mediterranean, numbering over 300 settlements by 600 BCE.[11] This era ended with the Greco-Persian Wars (499–449 BCE), transitioning to the Classical period (480–323 BCE), defined by Athenian naval supremacy after Salamis in 480 BCE, democratic institutions peaking under Pericles (c. 461–429 BCE), and conflicts like the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BCE), which involved over 1,000 battles and reduced populations in affected regions by up to 30%.[11] The Hellenistic period (323–31 BCE) ensued after Alexander's death, fragmenting his empire into successor states like the Ptolemaic (Egypt, lasting until 30 BCE) and Seleucid (Asia, controlling 50 million subjects at peak), fostering urban growth with foundations like Alexandria (population c. 500,000 by 200 BCE) and cultural Hellenization evidenced by Koine Greek's dominance.[12] Roman phases overlap with later Greek developments, starting from the Republic (509–27 BCE), initiated by the overthrow of the monarchy and Tarquin the Proud, featuring consular governance, territorial expansion to 4.4 million km² by 100 BCE, and civil wars culminating in Caesar's dictatorship (49–44 BCE) and Octavian's victory at Actium in 31 BCE.[9] The Empire (27 BCE–476 CE) formalized autocracy under Augustus, who commanded 28 legions totaling 150,000 men, ushering the Pax Romana (c. 27 BCE–180 CE) with trade volumes exceeding 100,000 tons annually via Mediterranean routes, administrative provinces numbering 45 by 117 CE under Trajan, and eventual crises including the 3rd-century invasions that halved the population from 60 million to 30 million.[9] The Western Empire's deposition of Romulus Augustulus in 476 CE marks a conventional endpoint, though Eastern continuity persisted until 1453 CE; these divisions prioritize Roman political succession over climatic or economic factors, which some analyses suggest drove migrations like the Gothic incursions of 376 CE.[13]Terminology and Conceptual Framework

The term "Greco-Roman" denotes cultural phenomena exhibiting traits derived from both ancient Greek and Roman sources, particularly in domains such as architecture, literature, and governance, where Roman adaptations often built upon Greek precedents established centuries earlier.[14] This nomenclature emerged in modern scholarship to encapsulate the intertwined legacies of these civilizations, reflecting Rome's extensive borrowing from Hellenistic traditions after subjugating Greek-influenced territories between 200 and 146 BCE.[15] The phrase avoids implying equivalence between the two, as Roman culture pragmatically assimilated Greek elements—such as philosophical schools from Athens—while innovating in engineering and law to suit imperial scale. Central to the conceptual framework is the notion of cultural syncretism, wherein Greek intellectual and artistic paradigms fused with Roman administrative and martial structures, yielding a hybrid system dominant across the Mediterranean basin from roughly the 8th century BCE to the 5th century CE.[16] Hellenization, initiated by Alexander the Great's conquests (336–323 BCE), propelled the dissemination of Koine Greek as a lingua franca, urban planning models like grid layouts, and polytheistic cults adapted to local contexts, extending Greek influence into Persia, Egypt, and beyond.[17] Romanization, conversely, involved the incremental adoption of Roman citizenship, infrastructure (e.g., aqueducts and roads totaling over 400,000 kilometers by the 2nd century CE), and legal norms by provincial elites, often driven by economic incentives and elite emulation rather than coercion alone.[18] These processes underscore causal dynamics of diffusion: elite mediation and material incentives facilitated integration, as evidenced by epigraphic records showing rising Latin inscriptions in Gaul from the 1st century BCE onward. This framework posits the Greco-Roman world not as discrete epochs but as a continuum of adaptive evolution, with the Hellenistic interlude (323–31 BCE) bridging Greek polities and Roman hegemony, fostering shared paradigms like rational discourse in ethics (e.g., Stoicism's endurance from Zeno in 300 BCE to Marcus Aurelius in 180 CE) and civic republicanism.[19] Geographically, it centers on the Mediterranean "inland sea," encompassing core regions from Iberia to Anatolia, where demographic flows—estimated at 50–60 million inhabitants by 150 CE—sustained trade networks exchanging 100,000 tons of grain annually from Egypt alone.[20] Scholarly analysis, informed by inscriptions, papyri, and archaeological strata, emphasizes empirical patterns over ideological narratives, revealing how environmental factors like navigable coasts enabled this synthesis while internal fractures, such as overreliance on slave labor (comprising up to 30% of Italy's population in the late Republic), presaged decline.[20]Geography and Demography

Territorial Extent and Core Regions

The Greco-Roman world was geographically centered on the Mediterranean basin, which facilitated trade, cultural exchange, and military expansion due to its enclosed seas, coastal plains, and navigable rivers. Core regions included the Greek mainland—encompassing the rugged Balkan Peninsula south of Macedonia, the Peloponnese, Attica, Thessaly, and Epirus—along with the Aegean and Ionian islands, which formed natural hubs for maritime connectivity.[21] These areas, characterized by mountainous terrain covering about 80% of the land and limited arable valleys, supported independent city-states like Athens and Sparta while encouraging overseas colonization. In Italy, the core focused on the central peninsula, particularly Latium around the Tiber River, where Rome originated as a strategic riverine and overland crossroads.[22] Southern Italy and Sicily, known as Magna Graecia, represented early extensions of Greek settlement from the 8th century BCE, with colonies like Syracuse and Tarentum integrating local Italic populations and serving as bridges to Etruscan and later Roman territories.[23] Asia Minor (modern western Turkey) emerged as a vital core periphery, incorporating Ionian Greek cities such as Miletus and Ephesus, which blended Hellenic culture with Anatolian influences.[24] The Mediterranean's climatic uniformity—mild winters and dry summers—underpinned agricultural staples like olives, grapes, and grains, sustaining dense populations in coastal lowlands while isolating interior highlands.[25] Territorial extent expanded dramatically during the Hellenistic period following Alexander the Great's conquests (336–323 BCE), reaching from Greece and Macedonia westward to Sicily, eastward across Asia Minor, the Levant, Mesopotamia, Persia, and into northwest India, with the Seleucid Empire alone spanning from Thrace to the Indus River by circa 300 BCE.[24] Ptolemaic Egypt controlled the Nile Valley and Cyprus, while Antigonid Macedonia retained Balkan holdings, creating a fragmented but interconnected Hellenistic sphere of roughly 4–5 million square kilometers at its height.[26] Roman consolidation from the 3rd century BCE onward unified much of this domain, incorporating the Hellenistic kingdoms by 31 BCE after Actium, and achieving maximum extent under Trajan in 117 CE: approximately 5 million square kilometers across Europe (from Britain and the Rhine-Danube frontiers to the Balkans), North Africa (Morocco to Egypt), and the Near East (to the Euphrates and temporarily Mesopotamia).[27] This imperial reach, often termed Mare Nostrum for the internalized Mediterranean, emphasized defensible natural barriers like the Alps, Pyrenees, and Sahara while prioritizing coastal and riverine control for logistics and defense.[28] Provincial cores such as Gaul (modern France), Hispania, and Egypt integrated via Roman infrastructure, with urban networks radiating from Rome and Alexandria, though peripheral zones like Germania beyond the Rhine remained unconquered due to logistical limits and tribal resistance.[29] Demarcation lines, including Hadrian's Wall in Britain (built 122 CE) and the African limes, reflected pragmatic boundaries balancing expansion costs against resource yields, with the empire's cohesion reliant on sea lanes rather than vast continental depth.[30] By the 4th century CE, territorial integrity eroded in the west due to barbarian incursions, but eastern cores like Anatolia and the Levant persisted under Byzantine continuity until later medieval shifts.[3]Population Dynamics and Urban Centers

The population of ancient Greece during the Classical period (c. 500–323 BCE) is estimated at 2–3 million across the mainland, islands, and colonies, with urban centers forming dense hubs amid predominantly rural agrarian societies. Athens, the largest polis, supported a total population of 200,000–300,000 in Attica at its 5th-century BCE peak, comprising roughly 30,000–50,000 adult male citizens, metics (resident foreigners), and slaves who outnumbered free inhabitants.[31][32] This density relied on maritime trade, tribute from the Delian League, and surrounding farmland, though high infant mortality rates (estimated at 200–300 per 1,000 births) and frequent warfare constrained sustained growth. Sparta, by contrast, prioritized a militarized citizen elite of about 8,000 adult males (homoioi), sustained by a helot underclass numbering 75,000–118,000 in Laconia around 480 BCE, resulting in a more dispersed, less urbanized structure focused on rural control rather than city expansion.[33] Hellenistic expansion following Alexander's conquests (323–31 BCE) shifted dynamics toward larger, cosmopolitan foundations like Alexandria in Egypt, which grew to 300,000–500,000 residents by the 2nd century BCE through immigration, royal patronage, and Nile Valley agriculture, fostering a multiethnic urban elite.[34] Overall Greek-world urbanization remained low at 10–20%, with cities under 10,000 inhabitants common, as populations fluctuated due to colonization, slave imports (often 20–30% of urban dwellers), and episodic famines or plagues.[32] Under Roman hegemony, the empire's population reached 50–70 million by the 2nd century CE, with Italy alone holding 5–7 million, driven by conquest-driven slavery (millions imported annually at peaks), rural-to-urban migration, and aqueduct-enabled food surpluses. Urbanization rates climbed to 15–20%, higher in the west (e.g., Gaul's oppida evolving into coloniae), but cities often stagnated or declined post-200 CE amid Antonine Plague losses (up to 25% in some regions) and economic decentralization. Rome itself peaked at 800,000–1 million inhabitants under Augustus (c. 27 BCE), subsisting on grain doles for 200,000–300,000 citizens and slaves, though archaeological surveys indicate densities of 100–400 persons per hectare in insulae housing.[35][36] Key urban centers exemplified these patterns, with Hellenistic and Roman foundations emphasizing monumental infrastructure like theaters and forums to integrate diverse populations:| City | Peak Period | Estimated Population | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Athens | Classical (5th c. BCE) | 200,000–300,000 | Including Attica; citizen core ~30,000 males.[31] |

| Alexandria | Hellenistic/Roman (2nd c. BCE–CE) | 300,000–600,000 | Multiethnic hub; library and lighthouse as attractors.[35][34] |

| Rome | Early Imperial (1st–2nd c. CE) | 800,000–1,000,000 | Relied on annona grain ships; fire-prone tenements.[35] |

| Antioch | Roman (2nd c. CE) | 200,000–400,000 | Trade nexus; earthquakes recurrently reduced numbers.[35] |

| Carthage | Roman (2nd c. CE) | 200,000–300,000 | Rebuilt post-Punic Wars; agricultural hinterland key.[34] |

_(30776483926).jpg/250px-L'Olympieion_(Athènes)_(30776483926).jpg)

_(30776483926).jpg)