Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

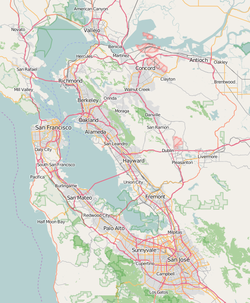

Mill Valley, California

View on Wikipedia

Mill Valley is a city in Marin County, California, United States, located about 14 miles (23 km) north of San Francisco via the Golden Gate Bridge and 52 miles (84 km) from Napa Valley. The population was 14,231 at the 2020 census.

Key Information

Mill Valley is located on the western and northern shores of Richardson Bay, and the eastern slopes of Mount Tamalpais. Beyond the flat coastal area and marshlands, it occupies narrow wooded canyons, mostly of second-growth redwoods, on the southeastern slopes of Mount Tamalpais. The Mill Valley 94941 ZIP Code also includes the following adjacent unincorporated communities: Almonte, Alto, Homestead Valley, Tamalpais Valley, and Strawberry. The Muir Woods National Monument is also located just outside the city limits.

History

[edit]Coast Miwok

[edit]The first people known to inhabit Marin County, the Coast Miwok, arrived approximately 6,500 years ago. The territory of the Coast Miwok encompasses all of Marin County, north to Bodega Bay and southern Sonoma County. More than 600 village sites have been identified, including 14 sites in the Mill Valley area. Nearby archaeological discoveries include rock carvings and grain-grinding sites on Ring Mountain.[9] The pre-Missionization population of the Coast Miwok is estimated to have been between 1,500 (Alfred L. Kroeber's estimate for the year 1770 AD)[10] and 2,000 (Sherburne F. Cook's estimate for the same year[11]). The pre-Spanish era Coast Miwok population may have even been as high as 5,000. Cook speculated that by 1848, their population had decreased to merely 300, from foreign disease-exposure and Spanish violence, and was down to 60 by 1880. As of 2011, there are over 1,000 registered members of the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria, which includes both the Coast Miwok and the Southern Pomo, all of whom can date their ancestry back to 14 survivors as original tribal ancestors.[12][13]

In Mill Valley, on Locust Avenue (between Sycamore and Walnut avenues), there is now a metal plaque set in the sidewalk in the area believed to be the birthplace of Chief Marin in 1781; the plaque was dedicated on May 8, 2009.[14] The village site was first identified by Nels Nelson in 1907, and his excavation revealed tools, burials and food debris, among other things, just beyond the driveway of a residence on Locust Ave. At that time, the mound was 20 feet (6.1 m) high. Shell mounds have been discovered in areas by streams and along Richardson Bay, including in the Strawberry and Almonte neighborhoods.

Another famous Mill Valley site was in the Manzanita area, underneath the Fireside Inn, previously known as the Manzanita Roadhouse (and the Manzanita Hotel, Emil Plasberg's Top Rail, and Top Rail Tavern); the bulk of such establishments were notoriously regarded during the time of United States Prohibition-era gin joints and brothels. The Manzanita was located near the intersection of U.S. Route 101 and California State Route 1. Built in 1916, the "Blind Pig" roadhouse was located outside of the dry laws that were enforced more strictly within the city itself.

In 1776, with the foundation of Mission San Francisco de Asís (commonly known as Mission Dolores), the Coast Miwok of southern Marin began to slowly enter the mission; first, those from Sausalito came, followed by those from areas now known as Mill Valley, Belvedere, Tiburón and Bolinas. They called themselves the "Huimen" people. At the mission, they were taught the Catholic faith, lost all of their known freedom, and over three-quarters died as a result of exposure to foreign diseases, to which the Native Americans lacked immunity. Nearly just as many people died from violent acts perpetrated by the Spaniards and Europeans. As a result of the high death rate at Mission Dolores, it was decided to build a new Mission San Rafael, built in 1817. Over 200 surviving Coast Miwok were taken there from Mission Dolores and Mission San Jose—including the 17 survivors of the Huimen Coast Miwok of the Richardson Bay area California Missions.[15]

Early settlers

[edit]By 1834, the Mission era had ended and California was under the control of the Mexican government. They took Miwok ancestral lands, divided them and gave them to Mexican soldiers or relatives who had connections with the Mexican governor. The huge tracts of land, called ranchos by the Mexican settlers, or Californios, soon covered the area. The Miwoks who had not died or fled were often employed under a state of indentured servitude to the California land grant owners. That same year, the governor of Alta California, José Figueroa, awarded to John T. Reed the first land grant in Marin, Rancho Corte Madera del Presidio. Just west of that, Rancho Saucelito was transferred to William A. Richardson in 1838 after being originally awarded to Nicolas Galindo in 1835. William Richardson also married a well-connected woman; both he and Reed were originally from Europe. Richardson's name was later applied to Richardson Bay, an arm of the San Francisco Bay that brushes up against the eastern edge of Mill Valley. The Richardson rancho contained everything south and west of the Corte Madera and Larkspur areas with the Pacific Ocean, San Francisco Bay, and Richardson Bay as the other three borders. The former encompassed what is now southern Corte Madera, the Tiburon Peninsula, and Strawberry Point.[16]

In 1836, John Reed married Hilaria Sanchez, the daughter of a commandante in the San Francisco Presidio. He built the first sawmill in the county on the Cascade Creek (now Old Mill Park) in the mid-1830s on Richardson's rancho and settled near what is now Locke Lane and LaGoma Avenue.[17] The mill cut wood for the San Francisco Presidio. He raised cattle and horses and had a brickyard and stone quarry. Reed also did brisk businesses in hunting, skins, tallow, and other products until his death in 1843 at 38 years of age.[18] Richardson sold butter, milk and beef to San Francisco during the Gold Rush. Shortly thereafter, he made several poor investments and wound up massively in debt to many creditors. On top of losing his Mendocino County rancho, he was forced to deed the 640-acre (2.6 km2) Rancho Saucelito to his wife, Maria Antonia Martinez, daughter of the commandante of the Presidio, in order to protect her. The rest of the rancho, including the part of what is now Mill Valley that did not already belong to Reed's heirs, was given to his administrator Samuel Reading Throckmorton. At his death in 1856 at 61 years old, Richardson was almost destitute.[19]

Throckmorton came to San Francisco in 1850 as an agent for an eastern mining business before working for Richardson. As payment of a debt, Throckmorton acquired a large portion of Rancho Saucelito in 1853–54 and built his own rancho, "The Homestead," on what is now Linden Lane and Montford Avenue. The descendants of ranch superintendent Jacob Gardner continue to be active in Marin. Some of the rest of his land was leased out for dairy farming to Portuguese settlers.[17] A majority of the immigrants came from the Azores. Those who were unsuccessful at gold mining came north to the Marin Headlands and later brought their families. In Mill Valley, Ranch "B" is one of the few remaining dairy farm buildings and is located near the parking lot at the Tennessee Valley trailhead.[20] Throckmorton also suffered devastating financial problems before his death in 1887. His surname would later be applied to one of the major thoroughfares in Mill Valley. Richardson and Reed had never formalized the boundary lines separating their ranchos. Richardson's heirs successfully sued Reed's heirs in 1860 claiming the mill was built on their property. The border was officially marked as running along the Arroyo Corte Madera del Presidio along present-day Miller Avenue. Everything to the east of the creek was Reed property, and everything to the west was Richardson land. It was Richardson's territory that would soon become part of Mill Valley when Throckmorton's daughter Suzanna was forced to relinquish several thousand acres to the San Francisco Savings & Union Bank to satisfy a debt of $100,000 against the estate in 1889.[21]

In 1873, San Francisco physician Dr. John Cushing discovered 320 "lost" acres between the Reed and Richardson boundaries between present-day Corte Madera Avenue, across the creek, and into West Blithedale Canyon. Using the Homestead Act he petitioned the government and managed to acquire the land. Before his death in 1879 he had built a sanitarium in the peaceful canyon.[17] In Sausalito the North Pacific Coast Railroad had laid down tracks to a station near present-day Highway 101 at Strawberry.[22] Seeing the financial advantages of a railroad his descendants then turned the hospital into the Blithedale Hotel after the land title was finally granted in 1884. The sanitarium was enlarged, cottages were built up along the property, and horse-drawn carriages were purchased to pick up guests at the Alto station. Within a few years, several other summer resort hotels had cropped up in the canyon including the Abbey, the Eastland, and the Redwood Lodge.[23] Fishing, hunting, hiking, swimming, horseback riding, and other activities increased in popularity as people came to the area as vacationers or moved in and commuted to San Francisco for work. Meanwhile, Reed's mill deforested much of the surrounding redwoods, meaning that most of the redwoods growing today are second- or third-growth. The King family (King Street) owned property near the Cushing land. One of its buildings was a small adobe house which is believed to have predated the King farm.[13] The Blithedale Hotel used it as a milk house. The adobe structure is still standing and connected to a house on West Blithedale Avenue; it is the oldest structure in Mill Valley.

The San Francisco Savings & Union Bank organized the Tamalpais Land & Water Company in 1889 as an agency for disposing of the Richardson land gained from the Throckmorton debt. The board of directors was President Joseph Eastland, Secretary Louis L. Janes (Janes Street), Thomas Magee (Magee Avenue), Albert Miller (Miller Avenue), and Lovell White (Lovell Avenue).[24] Eastland, who had been president of the North Pacific Coast Railroad in 1877 and retained an interest, pushed to extend the railroad into the area in 1889. Though Reed, Richardson, and the Cushings were crucial to bringing people to the Mill Valley area, it was Eastland who really propelled the area and set the foundation for the city today. He had founded power companies all around the San Francisco Bay area, was on the board of several banks, and had control of several commercial companies.[17] The Tamalpais Land & Water Co. hired Michael M. O'Shaughnessy, already a noted engineer to lay out roads, pedestrian paths, and step-systems for what the developers hoped would become a new city. He also built the Cascade Dam & Reservoir for water supply, and set aside land plots for churches, schools, and parks.

On May 31, 1890, nearly 3,000 people attended The Tamalpais Land & Water Co. land auction near the now-crumbling sawmill. More than 200 acres (0.81 km2) were sold that day in the areas of present-day Throckmorton, Cascade, Lovell, Summit, and Miller Avenues and extending to the west side of Corte Madera Avenue. By 1892, there were two schools in the area and a few churches.[17] The auction also brought into Mill Valley architects, builders, and craftsmen. Harvey A. Klyce was one of the most prominent of the architects and designed many private homes and public buildings in the area, including the Masonic Lodge in 1904.[25] Before his death in 1894, Eastland built a large summer home, "Burlwood", constructed on Throckmorton Avenue in 1892 that still stands though much of the original land has been parceled off. Burlwood was the first home in the town to have electricity, and when telephones were installed only he and Mrs. Cushing, the owner of the Blithedale Hotel, had service.[24] After the land auctions the area was known as both "Eastland" and "Mill Valley".[26]

Janes, by then the resident director of Tamalpais Land & Water Co. (and eventually the city's first town clerk), and Sidney B. Cushing, president of the San Rafael Gas & Electric Co. set out to bring a railroad up Mt. Tamalpais. The Mt. Tamalpais Scenic Railway opened in 1896 (with Cushing as president) and ran from the town center (present-day Lytton Square) all the way to the summit. In 1907, the railroad added a branch line into "Redwood Canyon", and in 1908, the canyon became Muir Woods, a national monument. The railroad built the Muir Inn (with a fine restaurant) and overnight cabins for visitors. The Mt. Tamalpais & Muir Woods Scenic Railway, "The Crookedest Railroad in the World" and its unique Gravity Cars[27] brought thousands of tourists to the Tavern of Tamalpais on the mountain summit (built in 1896, rebuilt after the 1923 fire, and razed in 1950 by the California State Parks),[28] the West Point Inn (built in 1904, by the scenic railway, operated commercially until 1943, closed briefly and then run by volunteers to the present day),[29] and the Muir Woods Inn (burned in 1913, rebuilt in 1914, destroyed in 1930).[30] The tracks were removed in 1930 after the 1929 fire. This occurred as a result of a drop in ridership due to increased usage of automobiles rather than trains for recreation and construction of the Panoramic Highway and connecting road to Ridgecrest in 1929. Rails connected Mill Valley with neighboring cities and commuters to San Francisco via ferries.[citation needed]

Incorporation through WWII

[edit]

By 1900, the population was nearing 900 and the locals pushed out the Tamalpais Land & Water Co. in favor of incorporation. Organizations and clubs cropped up including the Outdoor Art Club (1902) (organized by Laura Lyon White),[31][32] Masonic Lodge (1903)[33] which celebrated its centennial in 2003[34] and the Dipsea Race (1905), the latter marking its 100th anniversary in 2010.[35] The second big population boom came after the 1906 Great earthquake. While much of San Francisco and Marin County was devastated, many fled to Mill Valley and most never left. In that year alone the population grew to over 1,000 permanent residents.[36] Creeks were bridged over or dammed, more roads laid down and oiled, and cement sidewalks poured. Tamalpais High School opened in 1908, the first city hall was erected in 1908, and Andrew Carnegie's library in 1910. The Post Office opened under the name "Eastland", however after many objections it was changed to "Mill Valley" in 1904.[17] The very first Mountain Play was performed at the Mountain Theater on Mt. Tam in 1913.[37]

By the 1920s, most roads were paved over, mail delivery was in full swing, and the population was at its highest at more than 2,500 citizens. Mill Valley Italian settlers made wine during Prohibition, while some local bar owners made bootleg whiskey under the dense foliage around the local creeks.[38] January 1922 saw the first of several years of snow in Marin County, coating Mt. Tam white. Two years later the Sulphur Springs, a natural hot spring where locals could revive their lagging spirits, was covered over and turned in the playground of the Old Mill Elementary School.1929 was a year of great change for Mill Valley. The Great Fire raged for several days in early July and nearly destroyed the fledgling city. It ravaged much of Mt. Tam (including the Tavern and 117 homes) and the city itself was spared only by a change in wind direction.[17] In October of that year, the Mt. Tamalpais and Muir Woods Scenic Railway ran for the last time. The fire caused great devastation to tourism and tourist destinations, but the railroads were also crushed by the automobile. Panoramic Highway, running between Mill Valley and Stinson Beach was built in 1929–1930. The stock market crash of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression crippled what little railroad tourism there was to the point where the tracks were eventually taken up in 1931.

During the Great Depression, many famous local landmarks were constructed with the help of the Works Progress Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corps, including the Mead Theater at Tam High (named after school board Trustee Ernest Mead), the Mountain Theater rock seating, and the Golden Gate Bridge in 1934–1937.[38] The latter event suspended ferry commuting between Marin and the city from 1941 through 1970[39] and helped increase the Marin population. With the demise of the railroads came the introduction of local bus service. Greyhound moved into the former train depot in Lytton Square in October 1940. In Sausalito, Marinship brought over 75,000 people to Marin, many of whom moved to Mill Valley permanently. At the height of the War, nearly 400 locals were fighting, including many volunteer firemen and government officials. By 1950, 1 in 10 Mill Valleyans were living in a "Goheen Home". George C. Goheen built the so-called "defense homes" for defense workers throughout the 1940s and 1950s in the Alto neighborhood.[38]

1950s to present

[edit]This section possibly contains original research. (October 2024) |

With a population just over 7,000 by 1950,[38] Mill Valley was still relatively rural. Workers commuted to San Francisco on the Greyhound bus when the streets were not flooding in heavy rain,[citation needed] and there still were not any traffic lights. The military built the Mill Valley Air Force Station to protect the area during the Korean War. In 1956, a group of Beat poets and writers lived briefly in the Perry house, most notably Jack Kerouac and San Francisco Renaissance Beat poet Gary Snyder. The house and its land is now owned by the Marin County Open Space District. By the beginning of the 1960s, however, the population swelled. The Mill Valley Fall Arts Festival became a permanent annual event and the old Carnegie library was replaced with an award-winning library at 375 Throckmorton Ave. Designed by architect Donn Emmons, the new library was formally dedicated on September 18, 1966.[40] The 1970s saw a change in attitude and population. Mill Valley became an area associated with great wealth, with many people making their millions[citation needed] in San Francisco and moving north. New schools and neighborhoods cropped up, though the city maintained its defense of redwoods and protected open space.

Cascade Dam, built in 1893, was closed in 1972 and drained four years later in an attempt to curb the "hordes"[citation needed] of young people using the reservoir for nude sunbathing and swimming. Youth subculture would come under attack again in 1974 when the City Council banned live music, first at the Sweetwater and later at the Old Mill Tavern, both now defunct.[38] In 1977, the Lucretia Hanson Little History Room in the library opened and became the base of operations for the Mill Valley Historical Society. Marin County was hit with one of the worst droughts on record beginning in 1976 and peaking in 1977, brought on by a combination of several seasons of low rainfall and a refusal to import water from the Russian River, instead relying solely on rain water from Mt. Tam and the West Marin watersheds to fill the then-six reservoirs. By June 1977, the County managed to pipe in water from the Sacramento River Delta, staving off disaster. The rainfall during the winter of 1977-78 was one of the heaviest on record.[41] The Mill Valley Film Festival, now part of the California Film Institute, began in 1978 at the Sequoia Theatre.

The 1980s and 1990s saw the decline of small businesses in Mill Valley. Local establishments like Lockwood's Pharmacy closed in 1981 after running almost continuously for 86 years. Old Mill Tavern, O'Leary's, and the Unknown Museum shut their doors, as did Red Cart Market and Tamalpais Hardware. In their places came boutiques, upscale clothing stores, coffee shops, art galleries, and gourmet grocery stores. Downtown Plaza and Lytton Square were remodeled to fit the new attitude. The population in the city alone swelled over 13,000 and many of the old, narrow, winding streets grew clogged with traffic congestion.[38] The Public Library expanded with a new Children's Room, a downstairs Fiction Room, and Internet computers.[42] It also joined MARINet, a consortium of all the public libraries in Marin, to allow patrons greater access to information. MARINet now has an online catalogue of all the materials, both physical and electronic, in the Marin public libraries, which patrons can order, pick up, and drop off materials at any of the participating libraries.[43] The Old Mill also got a facelift; it was rebuilt to the same specifications as the original in 1991. The 1990s also saw another influx of affluence. Many new homeowners gutted homes built in the 19th and early 20th centuries or tore them down altogether.

The dawn of the new millennium brought reflection on the past, as the city celebrated 100 years of incorporation. Soon after Mill Valley got its brand new Community Center at 180 Camino Alto,[44] adjacent to Mill Valley Middle School.

On January 31, 2008, Mill Valley's sewage treatment plant spilled 2.45 million gallons of sewage into the San Francisco Bay.[45] This marked the second such spill in Mill Valley within a week (the previous one spilled 2.7 million gallons), and the most recent of several that occurred in Marin County in early 2008.[46] Mill Valley's treatment plant attributed the spills to "human error".[46] The spills caused distress in Mill Valley's administrative government, which remains outspoken about "dedicating itself to the protection of air quality, waste reduction, water and energy conservation, and the protection of wildlife and habitat" in Mill Valley.[47]

Geography

[edit]

According to the United States Census Bureau the city has a total area of 4.9 square miles (13 km2), of which 4.8 square miles (12 km2) is land and 0.08 square miles (0.21 km2) of (1.73%) water.[6]

The Mill Valley 94941 area lies between Mt. Tamalpais on the west, the city of Tiburon on the east, the City of Corte Madera on the north, and the Golden Gate National Recreational Area (GGNRA) on the south. Two streams flow from the slopes of Mt. Tamalpais through Mill Valley to the bay: the Arroyo Corte Madera del Presidio; and Cascade Creek. Mill Valley is surrounded by hundreds of acres of state, federal, and county park lands. In addition, there are many municipally maintained open-space reserves, parks, and coastal habitats which, when taken together, ensconce Mill Valley in a natural wilderness.

Mill Valley and the Homestead Valley Land Trust maintains many minimally disturbed wildland areas and preserves which are open to the public from sunrise to dusk every day. Several nature trails allow access as well as providing gateway access to neighboring state and federal park lands, and the Mt. Tamalpais Watershed[48] wildland on the broad eastern face of Mt. Tamalpais that overlooks Mill Valley. These are undeveloped natural areas and contain many species of wild animals, including some large predators like the coyote, the bobcat, and the cougar.

Climate

[edit]

Mill Valley has a mild Mediterranean climate which results in relatively wet winters and very dry summers. Winter lows rarely drop below freezing and summer highs rarely peak 90 °F (32 °C) with 90% of the annual rain falling in November through March. Wind speeds average lower than national averages in winter months and higher in summer, and often become quite gusty in the canyon regions of town. California coastal fog often affects Mill Valley, making relative humidity highly variable. The wetter winter months tend to make for a more consistent daily relative humidity around 70–90% (slightly higher than US averages). During the summer months, however, while the morning fog often keeps morning humidity normal, in a typical 70–80% range, by afternoon after the fog burns off, the humidity regularly plummets to around 30% as one would expect in this dry seasonal climate.[49]

| Climate data for Mill Valley, California | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 79 (26) |

79 (26) |

87 (31) |

96 (36) |

102 (39) |

110 (43) |

111 (44) |

106 (41) |

106 (41) |

101 (38) |

87 (31) |

77 (25) |

111 (44) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 56 (13) |

61 (16) |

65 (18) |

71 (22) |

76 (24) |

82 (28) |

85 (29) |

84 (29) |

82 (28) |

75 (24) |

63 (17) |

56 (13) |

71 (22) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 41 (5) |

43 (6) |

44 (7) |

46 (8) |

49 (9) |

52 (11) |

53 (12) |

54 (12) |

53 (12) |

50 (10) |

45 (7) |

41 (5) |

48 (9) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 20 (−7) |

21 (−6) |

27 (−3) |

31 (−1) |

23 (−5) |

39 (4) |

41 (5) |

40 (4) |

37 (3) |

30 (−1) |

26 (−3) |

18 (−8) |

18 (−8) |

| Average rainfall inches (mm) | 9.60 (244) |

9.10 (231) |

7.05 (179) |

2.56 (65) |

1.20 (30) |

0.24 (6.1) |

0.01 (0.25) |

0.12 (3.0) |

0.50 (13) |

2.33 (59) |

7.47 (190) |

7.29 (185) |

47.47 (1,206) |

| Source: http://www.weather.com/weather/wxclimatology/monthly/graph/94941 | |||||||||||||

Mill Valley is also affected by microclimate conditions in the several box canyons with steep north-facing slopes and dense forests which span the southern and western city limits, which, along with the coastal fog, all conspire to make many of the dense forested regions of Mill Valley noticeably cooler and moister, on average, than other regions of town. This microclimate is what makes for the favorable ecology required by the Coastal Redwood forests which still cover much of the town and surrounding area, and have played such a pivotal role throughout the history of Mill Valley.

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1910 | 2,551 | — | |

| 1920 | 2,554 | 0.1% | |

| 1930 | 4,164 | 63.0% | |

| 1940 | 4,847 | 16.4% | |

| 1950 | 7,331 | 51.2% | |

| 1960 | 10,411 | 42.0% | |

| 1970 | 12,942 | 24.3% | |

| 1980 | 12,967 | 0.2% | |

| 1990 | 13,038 | 0.5% | |

| 2000 | 13,600 | 4.3% | |

| 2010 | 13,903 | 2.2% | |

| 2020 | 14,231 | 2.4% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[50] | |||

2020

[edit]The 2020 United States census reported that Mill Valley had a population of 14,231. The population density was 2,976.0 inhabitants per square mile (1,149.0/km2). The racial makeup of Mill Valley was 81.7% White, 1.0% African American, 0.2% Native American, 6.0% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 1.8% from other races, and 9.2% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 6.0% of the population.[51]

The census reported that 98.8% of the population lived in households, 1.0% lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and 0.2% were institutionalized.[51]

There were 5,988 households, out of which 30.9% included children under the age of 18, 50.4% were married-couple households, 4.8% were cohabiting couple households, 30.1% had a female householder with no partner present, and 14.8% had a male householder with no partner present. 31.9% of households were one person, and 17.8% were one person aged 65 or older. The average household size was 2.35.[51] There were 3,733 families (62.3% of all households).[52]

The age distribution was 22.5% under the age of 18, 5.4% aged 18 to 24, 16.4% aged 25 to 44, 32.1% aged 45 to 64, and 23.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 48.7 years. For every 100 females, there were 87.7 males.[51]

There were 6,502 housing units at an average density of 1,359.7 units per square mile (525.0 units/km2), of which 5,988 (92.1%) were occupied. Of these, 66.1% were owner-occupied, and 33.9% were occupied by renters.[51]

In 2023, the US Census Bureau estimated that 18.9% of the population were foreign-born. Of all people aged 5 or older, 84.9% spoke only English at home, 1.2% spoke Spanish, 11.8% spoke other Indo-European languages, 1.9% spoke Asian or Pacific Islander languages, and 0.1% spoke other languages. Of those aged 25 or older, 98.9% were high school graduates and 77.1% had a bachelor's degree.[53]

The median household income in 2023 was $208,466, and the per capita income was $120,115. About 1.7% of families and 5.0% of the population were below the poverty line.[54]

2010

[edit]The 2010 United States census[55] reported that Mill Valley had a population of 13,903. The population density was 2,868.2 inhabitants per square mile (1,107.4/km2). The racial makeup of Mill Valley was 12,341 (88.8%) White, 118 (0.8%) African American, 23 (0.2%) Native American, 755 (5.4%) Asian, 14 (0.1%) Pacific Islander, 152 (1.1%) from other races, and 500 (3.6%) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 622 persons (4.5%).

The Census reported that 99.5% of the population lived in households and 0.5% were institutionalized.

There were 6,084 households, out of which 1,887 (31.0%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 2,984 (49.0%) were opposite-sex married couples living together, 465 (7.6%) had a female householder with no husband present, 178 (2.9%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 306 (5.0%) unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 55 (0.9%) same-sex married couples or partnerships. 2,016 households (33.1%) were made up of individuals, and 888 (14.6%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.27. There were 3,627 families (59.6% of all households); the average family size was 2.94.

The population was spread out, with 3,291 people (23.7%) under the age of 18, 459 people (3.3%) aged 18 to 24, 2,816 people (20.3%) aged 25 to 44, 4,714 people (33.9%) aged 45 to 64, and 2,623 people (18.9%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 46.6 years. For every 100 females, there were 85.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 80.8 males.

There were 6,534 housing units at an average density of 1,348.0 units per square mile (520.5 units/km2), of which 3,974 (65.3%) were owner-occupied, and 2,110 (34.7%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 1.2%; the rental vacancy rate was 4.5%. 9,861 people (70.9% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 3,966 people (28.5%) lived in rental housing units.

Government

[edit]Federal and state

[edit]In the United States House of Representatives, Mill Valley is in California's 2nd congressional district, represented by Democrat Jared Huffman.[56] From 2008 to 2012, Huffman represented Marin County in the California State Assembly.

In the California State Legislature, Mill Valley is in:

- the 12th Assembly district, represented by Democrat Damon Connolly[57]

- the 2nd senatorial district, represented by Democrat Mike McGuire.

According to the California Secretary of State, as of February 10, 2019, Mill Valley has 10,189 registered voters. Of those, 6,270 (61.5%) are registered Democrats, 965 (9.5%) are registered Republicans, and 2,605 (25.6%) have declined to state a political party.[58]

Cityscape

[edit]

The combination of Mill Valley's idyllic location nestled beneath Mount Tamalpais coupled with its relative ease of access to nearby San Francisco has made it a popular home for many high-income commuters. Over the last 30 years, following a trend that is endemic throughout the Bay Area, home prices have climbed in Mill Valley (the median price for a single-family home was in excess of $1.5 million as of 2005), which has had the effect of pushing out some residents who can no longer afford to live in the area.[citation needed] This trend has also transformed Mill Valley's commercial activity, with nationally recognized music store Village Music having closed, then replaced in 2008 by more commercial establishments.[59]

In July 2005, CNN/Money and Money magazine ranked Mill Valley tenth on its list of the 100 Best Places to Live in the United States.[60] In 2007, MSN and Forbes magazine ranked Mill Valley seventy-third on its "Most expensive zip codes in America" list.[61]

While Mill Valley has retained elements of its earlier artistic culture through galleries, festivals, and performances, its stock of affordable housing has diminished,[62] forcing some residents to leave the area. This trend has also affected some of the city's well-known cultural centers like Village Music and the Sweetwater Saloon. As of April 2007, only one affordable housing project was underway: an initiative to renovate and expand a century old but now abandoned local landmark roadhouse and saloon called the Fireside Inn.[63] This renovation was completed in the fall of 2008 and provided around 50 low-income apartments, with around 30 dedicated to low-income seniors and the remainder going to low-income families.[64]

Neighborhoods and unincorporated areas

[edit]Strawberry is an unincorporated census-designated place to the east of the City of Mill Valley. The other CDP with a Mill Valley mailing address is Tamalpais-Homestead Valley. Smaller unincorporated areas include Alto and Almonte. Muir Beach is in the Mill Valley School District, but it is in the Sausalito mailing area.

Neighborhoods in the Mill Valley area:

| Almonte | "Alto" Sutton Manor | Blithedale Canyon | Boyle Park | Cascade Canyon | Country Club | Downtown | East Blithedale Corridor |

| Edgewood Cypress | Enchanted Knolls | Eucalyptus Knolls | Homestead Valley | Kite Hill | Land of Peter Pan | Marin Terrace | Marin View |

| Middle Ridge | Mill Valley Heights | Mill Valley Meadows | Miller Avenue | Molino Edgewood | Muir Woods | Old Mill | Panoramic Highway |

| Scott Highlands | Scott Valley | Sequoia Valley | Shelter Bay | Shelter Ridge | Strawberry | Sycamore | Sycamore Park |

| Tam Junction | Tamalpais Valley | Tamalpais Park | Tennessee Valley | Vernal Heights | Warner Canyon |

City recreational parks

[edit]

Mill Valley maintains many recreational parks which often contain playgrounds, wooded trails and other designated areas specifically designed for playing various sports.[65]

Education

[edit]Public schools

[edit]

Public schools are managed by the Mill Valley School District. There are five elementary schools and one middle school, Mill Valley Middle School, a four-time winner of the California Distinguished School Award.[66] The local high school, Tamalpais High School, is part of the Tamalpais Union High School District, whose five campuses serve central and southern Marin County. North Bridge Academy, a private school located in downtown Mill Valley, serves 2nd - 8th grade students with dyslexia.[67] Marin Horizon School is an independent school serving students in grades PK-8. Founded in 1977, the school enrolls 296 students.

Mill Valley Public Library

[edit]

The municipal library overlooks Old Mill Park and provides many picturesque reading locations, as well as free computer and Internet access. The Mill Valley library first digitized its vast holdings under the stewardship of Thelma Weber Percy, who was determined to see the Mill Valley Public Library come into the computer age. Recently they have begun offering Museum Passes to 94941 residents for free entry to Bay Area museums.[68] As part of the City of Mill Valley's decision to "go Green", the library has a Sustainability Collection with books and DVDs with information about how to become more environmentally friendly.[69]

The Mill Valley Public Library is also home to the Lucretia Hanson Little History Room, which has thousands of books, photographs, newspapers, pamphlets, artifacts, and oral histories on the history of California, Marin County, and Mill Valley.[70]

Annual events

[edit]Mill Valley is the home of several annual events, many of which attract national and international followings:

In media

[edit]Mill Valley has also been home to many artists, actors, authors, musicians, and TV personalities, and it is the setting for or is mentioned in many artworks. For example:

- Actress and comedian Eve Arden was born there in 1908.[73]

- Actress and dancer Monica Barbaro, nominated for an Academy Award in 2025, grew up there and graduated from Tamalpais High School.

- Rock music stars such as Michael Bloomfield, John and Mario Cipollina, Clarence Clemons, Dan Hicks, Sammy Hagar, Janis Joplin, Huey Lewis, Lee Michaels,[74] Bonnie Raitt, Pete Sears, and Bob Weir have called Mill Valley home at some point.

- Famed music executive/producer and film director George Daly worked originally with Janis Joplin and Huey Lewis, then both Mill Valley residents, along with Marin's Carlos Santana, and Mill Valley singer-songwriter Tim Hockenberry (of TV's America's Got Talent successes); Daly also co-directed and co-wrote the Gary Yost Mill Valley-focused movie The Invisible Peak, concerning the razing of the Mount Tamalpais West Peak during the Cold War. The multiple award-winning film, narrated by Peter Coyote, was featured in multiple US film festivals, including the Mill Valley Film Festival.

- Jerry Garcia—who recorded music in a Mill Valley recording studio—also once called Mill Valley home.

- Author John Gray, who writes the Men are from Mars, Women are from Venus books, is a long time Mill Valley resident.

- Award-winning sports journalist Ann Killion was born and raised in Mill Valley.

- Printmaker and author Tom Killion was born and raised in Mill Valley.[75][76]

- Writer Ki Longfellow lived on Hillside Avenue.

- Composer John Anthony Lennon was raised in Mill Valley.

- John Lennon and Yoko Ono summered in Mill Valley in the early 1970s, having left some of his own graffiti on the wall of the residence "The Maya the Merrier."

- Music producer-songwriter Scott Mathews' home is up on Mount Tamalpais, while his private recording studio and office is run out of his other Mill Valley house on the banks of Richardson Bay.[77]

- Jack Finney was a Mill Valley author whose best-known works include The Body Snatchers, the basis for the influential and classic 1956 movie Invasion of the Body Snatchers, and all its remakes. He moved with his young family from New York City to Mill Valley, where he wrote his most famous novel in the early 1950s.

- Artist and Marin County-native Zio Ziegler completed a mural titled "The Mysterious Thing" on side of the CineArts Sequoia theater in 2016.[78]

In film

[edit]- The film Serial (1980) starring Martin Mull, Tuesday Weld and Sally Kellerman was shot almost entirely on location in Mill Valley and nearby Tiburon.[79]

- The Tamalpais High School marching band appeared, as the Spring Street Settlement House marching band on Mission Street in San Francisco, in Woody Allen's film Take the Money and Run (1969).[80][81][82]

- In Paul Verhoeven’s film Basic Instinct (1992) a subplot character, Hazel Dobkins, was a murderer fictionally visited by Sharon Stone’s character, Catherine Tramell, at "26 Albion Road in Mill Valley", but actually located at 26 Liberty Street in Petaluma.[83][84][85][86][87][88]

- In George Lucas' film American Graffiti (1973), the sock hop dance scenes were filmed in the high school's boys' gymnasium.[89]

- Naval aviator Dieter Dengler built a home on Mount Tamalpais, near the Mountain Home Inn, and lived there until his death in 2001; parts of the biographical documentary about him, Little Dieter Needs to Fly (1997) were filmed there.

In literature

[edit]- It is the setting for resident author Jack Finney's novel The Body Snatchers (1954), although the film, Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), and subsequent movie adaptations of the book have been set elsewhere.

- Writer Jack Kerouac and beat poet Gary Snyder shared a Mill Valley cabin in 1955-56[90] around 370 Montford Ave. in Homestead Valley. The cabin's coincidental location in Marin County and its adjacent location to a meadow where horses grazed, combined with Snyder's expertise in Asian languages and cultures, inspired Snyder name the cabin "Marin-An" (Japanese translation: "Horse Grove Hermitage")[90] It was during this stay in Mill Valley that Kerouac's recent budding interest in Zen Buddhism was greatly expanded by Snyder's expertise in the subject. Kerouac's novel The Dharma Bums (1958) was consequently composed while living here and contains many semi-fictionalized accounts of his and Snyder's lives while living at Marin-An.[91]

- The fictional character Charley Furuseth, in Jack London's 1904 novel The Sea-Wolf (1904), had a summer cottage here.

- American writer Cyra McFadden, while living in Mill Valley in the 1970s, wrote a column for the Pacific Sun newspaper entitled, The Serial, which satirized the trendy lifestyles of the affluent residents of Marin County.[92] She later turned her column ideas into a novel, The Serial: A Year in the Life of Marin County (1977), which focused on the fictional exploits of a Mill Valley couple, Kate and Harvey Holroyd, who never quite fit into the Marin "scene". The highly successful book was later adapted as a comedy film called Serial (1980), starring Tuesday Weld and Martin Mull.

In music

[edit]- The song "Mill Valley", recorded in 1970 and released on the album Miss Abrams and the Strawberry Point 4th Grade Class,[93] reached #90 on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100 and #5 Easy Listening.[94] While the school is in the Mill Valley School District, it is not within the city limits.

- The song “Sunday Sunny Mill Valley Groove Day” was written by Doug Sahm and recorded by the Sir Douglas Quintet in 1968.

- The instrumental "Girl from Mill Valley", composed by Nicky Hopkins and appearing on the Jeff Beck Group album Beck-Ola (1969).[95]

- The cover art for Sports (1983), the third album of Huey Lewis and the News, features a photo of the band at the 2 AM Club, a bar located in Mill Valley, where the band had performed during its early days.[96]

In television

[edit]- The fictional character B.J. Hunnicutt, from the TV show M*A*S*H, called Mill Valley home.

- The television show Quantum Leap's Episode 406 "Raped" is set in Mill Valley in 1980.

- In the Star Trek universe, it is home to the 602 Club.

- Fictional character Doris Martin from The Doris Day Show called Mill Valley home.

- In the syndicated version of the 1980 American sitcom Too Close for Comfort, Henry Rush was owner and editor of the Marin Bugler newspaper in Mill Valley.

- On the Netflix-produced teen drama series 13 Reasons Why, shot around Marin and Sonoma counties, the protagonist visits the Fernwood Cemetery.

- The fictional characters Larry and Abby Finkelstein from the TV show Dharma and Greg lived at 1421 Bank Lane in Mill Valley.[97]

Notable residents

[edit]- Vera Allison (1902–1993), jeweler, painter[98]

- Eve Arden, actress

- Milly Bennett, journalist

- Michael Bloomfield, blues guitarist

- Dana Carvey, actor and comedian

- David Crosby, singer-songwriter

- Tilden Daken, landscape painter

- George Michael Gaethke (1898–1982), printmaker, painter[98]

- Anagarika Govinda, author and teacher[99]

- Sammy Hagar, singer-songwriter and guitarist[100]

- David Harris (activist), journalist and activist

- Mariel Hemingway, actress

- Margaux Hemingway

- Jon Hendricks, jazz lyricist and singer

- Lane Ryo Hirabayashi, historian

- Salem Ilese, singer-songwriter

- Snatam Kaur, singer, songwriter and author

- Bridgit Mendler, singer-songwriter

- Van Morrison, singer-songwriter

- Kathleen Quinlan, Emmy & Academy nominated actress

- Howard Rheingold, critic, writer, and teacher

- Kenny Rosenberg (born 1995), baseball pitcher for the Los Angeles Angels

- DJ Shadow, disc jockey

- Grace Slick, singer-songwriter

- Jim Sugar, photographer

- Monty Tipton, racing driver

- John L. Wasserman, critic and columnist (San Francisco Chronicle)

- Bob Weir, musician

- Lawrence Donegan, journalist and musician[101]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "California Cities by Incorporation Date". California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Archived from the original (Word) on October 17, 2013. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ^ "City Council". City of Mill Valley. Retrieved October 9, 2025.

- ^ a b "Final Maps | California Citizens Redistricting Commission". Retrieved October 9, 2025.

- ^ "California's 2nd Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC. Retrieved October 9, 2025.

- ^ "Current Board of Supervisors". County of Marin. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ a b "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 30, 2021.

- ^ "Mill Valley". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ "Mill Valley (city) QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ C. Michael Hogan. 2008. Ring Mountain, The Megalithic Portal, ed. A. Burnham

- ^ Kroeber, Alfred L. 1925. Handbook of the Indians of California. Washington, D.C.: Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin No. 78. (Chapter 30, The Miwok); available at Yosemite Online Library

- ^ Cook, Sherburne. 1976. The Conflict Between the California Indian and White Civilization. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-03143-1.

- ^ "FIGR". Graton Rancheria. Archived from the original on March 6, 2018. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ a b "Oral Histories". Mill Valley Public Library. July 21, 2011. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ "Birth of Marin's namesake marked in Mill Valley neighborhood". Marinij.com. March 19, 2015. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ Goerke, Betty. 2007. Chief Marin, Leader, Rebel, and Legend: A History of Marin County's Namesake and his People. Berkeley, CA: Heyday Books. ISBN 978-1-59714-053-9

- ^ Robinson, Jen. "My choice for leisure, learning, living". co.marin.ca.us. Marin County Free Library. Archived from the original on November 14, 2008. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g "A Brief History of Mill Valley". Mill Valley Public Library. July 21, 2011. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ Robinson, Jen. "Corte Madera del Presidio (Corte de Madera del Presidio) Rancho". My choice for leisure, learning, living. Marin County Free Library. Archived from the original on November 10, 2009. Retrieved June 23, 2020 – via co.marin.ca.us.

- ^ Robinson, Jen. "Saucelito (Sausalito) Rancho". My choice for leisure, learning, living. Marin County Free Library. Archived from the original on February 11, 2012. Retrieved June 23, 2020 – via co.marin.ca.us.

- ^ "Portuguese Dairy Farmers". Golden Gate National Recreation Area (U.S. National Park Service). Retrieved February 26, 2017.

- ^ "History of Early Mill Valley". December 13, 2001. Archived from the original on December 13, 2001. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ "VIGNETTE > The Railroad on Miller Avenue". Mill Valley Historical Society. July 12, 2013. Retrieved August 5, 2025.

- ^ "Into the canyon (May 4, 2007)". Pacific Sun. September 14, 2007. Archived from the original on September 14, 2007. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ a b "Mill Valley". mill-valley.freemasonry.biz. September 6, 2006. Archived from the original on September 6, 2006. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ "Some of The Men who Built Masonry and the Lodge". mill-valley.freemasonry.biz. August 10, 2004. Archived from the original on August 10, 2004. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- ^ Durham, David L. (1998). California's Geographic Names: A Gazetteer of Historic and Modern Names of the State. Quill Driver Books. p. 664. ISBN 978-1-884995-14-9.

- ^ "Gravity Car Barn". May 6, 2009. Archived from the original on May 6, 2009. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- ^ Robinson, Jen (June 24, 2016). "Railroad". My choice for leisure, learning, living. Marin County Free Library. Archived from the original on February 18, 2012. Retrieved February 27, 2017 – via co.marin.ca.us.

- ^ "The West Point Inn - Marin, San Francisco, Mount Tamalpais, Hiking". July 21, 2006. Archived from the original on July 21, 2006. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ Robinson, Jen (June 24, 2016). "Muir Woods Inn". My choice for leisure, learning, living. Marin County Free Library. Archived from the original on February 18, 2012. Retrieved February 27, 2017 – via co.marin.ca.us.

- ^ "The Outdoor Art Club". March 27, 2009. Archived from the original on March 27, 2009. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Binkley, Cameron (2005). "A Cult of Beauty: The Public Life and Civic Work of Laura Lyon White". California History. 82 (2): 40–61. doi:10.2307/25161804. JSTOR 25161804.

- ^ "Freemasonry: History of Mill Valley Lodge #356". August 7, 2004. Archived from the original on August 7, 2004. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- ^ "Centennial Celebration". April 9, 2004. Archived from the original on April 9, 2004. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- ^ "The Dipsea Race". Dipsea.org. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ Matthew Stafford. "Marin County Genealogy - Marin County - Our Towns - Mill Valley". Sfgenealogy.org. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ "Mountain Play". April 30, 2007. Archived from the original on April 30, 2007. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Spring 2000 Review. Mill Valley Historical Society. 2000.

- ^ "History of Golden Gate Ferry Service". Goldengateferry.org. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ "1960s". Mill Valley Public Library. July 21, 2011. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ Pyfer, Chip (March 2007). "When Marin Went Dry". Marin Magazine. Marin County, California. Archived from the original on February 16, 2012. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ "1990s". Mill Valley Public Library. July 21, 2011. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ "MARINet Libraries Catalog". Marinet.lib.ca.us. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ "Parks and Recreation". City of Mill Valley. February 24, 2008. Archived from the original on February 24, 2008. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ "Second massive sewage spill in bay revealed". Marinij.com. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ a b "6,000-gallon sewage spill in San Rafael". Marinij.com. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ "City of Mill Valley : Mill Valley's Commitment to the Environment". June 3, 2008. Archived from the original on June 3, 2008. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ "MMWD: Recreation". May 27, 2005. Archived from the original on May 27, 2005. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ "Mill Valley, California (CA 94941) profile: population, maps, real estate, averages, homes, statistics, relocation, travel, jobs, hospitals, schools, crime, moving, houses, news, sex offenders". City-data.com. October 13, 2008. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e "Mill Valley city, California; DP1: Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics - 2020 Census of Population and Housing". US Census Bureau. Retrieved May 29, 2025.

- ^ "Mill Valley city, California; P16: Household Type - 2020 Census of Population and Housing". US Census Bureau. Retrieved May 29, 2025.

- ^ "Mill Valley city, California; CP02: Comparative Social Characteristics in the United States - 2023 ACS 5-Year Estimates Comparison Profiles". US Census Bureau. Retrieved May 29, 2025.

- ^ "Mill Valley city, California; DP03: Selected Economic Characteristics - 2023 ACS 5-Year Estimates Comparison Profiles". US Census Bureau. Retrieved May 29, 2025.

- ^ "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA - Mill Valley city". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- ^ "California's 2nd Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC. Retrieved March 1, 2013.

- ^ "Members | Assembly Internet". Assembly.ca.gov. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ "CA Secretary of State – Report of Registration – February 10, 2019" (PDF). ca.gov. Retrieved March 12, 2019.

- ^ "Swan song for Mill Valley music mecca". Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved February 26, 2017.

- ^ "MONEY Magazine: Best places to live 2005". CNN. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ^ "Stock quotes, financial tools, news and analysis - MSN Money". Moneycentral.msn.com. January 31, 2017. Archived from the original on April 18, 2007. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ "Anne Solem: Mill Valley's housing dilemma". Marinij.com. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ "Marin Independent Journal - Housing project gets a boost". September 29, 2007. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ "Fireside Inn in Mill Valley transformation turns heads". Marinij.com. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ "City of Mill Valley : Parks". May 11, 2008. Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ California School Recognition Program distinguished school honorees, accessed January 26, 2008 Archived October 11, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "California School Directory: North Bridge Academy". California Department of Education. October 2, 2023. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ "Marinet". Marinet.lib.ca.us. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ "History Room". Mill Valley Public Library. July 21, 2011. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ "The Dipsea Race". Dipsea.org. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ "Mill Valley Film Festival |". Mvff.com. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ "Eve Arden, 82; Portrayed TV's Beloved 'Our Miss Brooks'". Los Angeles Times. November 13, 1990. Retrieved October 16, 2019.

- ^ "Mr. Piano Power". Sounds. Spotlight Publications. August 28, 1971. p. 3.

- ^ "Tom Killion". In The Make. Retrieved June 18, 2018.

- ^ "California's Wild Edge; Prints by Tom Killion". Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History (SCMAH). January 12, 2018. Archived from the original on September 20, 2018. Retrieved June 18, 2018.

- ^ "Marin producer behind hit single | Archives". Marinscope.com. February 22, 2012. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ "New Zio Ziegler Mural 'The Mysterious Thing" Debuts, Dazzles Above Playa Deck". Enjoy Mill Valley. Retrieved June 17, 2019.

- ^ "'Serial' benefit premiere Friday in Marin". Argus-Courier. March 26, 1980. p. 10A.

- ^ "Screening Room: Paul Feig: The Rules of the Game BY STEVE POND". Directors Guild of America. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ Calvillo, Frank (January 23, 2018). "TAKE THE MONEY AND RUN…But Leave This Woody Allen Title Behind". Medium. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ "Take The Money And Run". June 2, 2012. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ "Filming Locations for Basic Instinct (1992)". The Worldwide Guide to Movie Locations. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ "Basic Instinct". Norton's Movie Maps. Retrieved May 8, 2020.[dead link]

- ^ "Petaluma, California in the movies". chillybin.com. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ "26 Liberty St". google maps. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ "Basic Instinct (1992) Filming Locations". The Movie District. Archived from the original on February 25, 2015. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ Barton-Fumo, Margaret (December 26, 2016). Paul Verhoeven: Interviews. Univ. Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9781496810168. Retrieved May 8, 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Tam High to mark its 100th year with fanfare". Marin Independent Journal. September 19, 2007. Retrieved October 16, 2019.

- ^ a b "Inventory of the Gary Snyder Papers". Content.cdlib.org. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ "History of Homestead Valley, Part II". April 5, 2003. Archived from the original on April 5, 2003. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ McFadden, Cyra. "The Serial" (PDF). Pacific Sun. p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 7, 2007. Retrieved June 29, 2007.

- ^ "Miss Abrams and The Strawberry Point 4th Grade Class". January 1, 2000 – via Amazon.

- ^ "Billboard Online - Now www.billboard.com". December 27, 1996. Archived from the original on December 27, 1996. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Beck-Ola : Jeff Beck". AllMusic. Retrieved November 15, 2024.

- ^ "2 AM Club". Rockandrollroadmap.com. January 5, 2016. [verification needed]

- ^ The Television Treasury: Onscreen Details from Sitcoms, Dramas and Other Scripted Series, 1947-2019. McFarland. May 21, 2020. ISBN 9781476640327.

- ^ a b Hughes, Edan Milton (1986). Artists in California, 1786-1940. San Francisco, CA: Hughes Publishing Company. pp. 18, 168. ISBN 978-0-9616112-0-0 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Gehi, Reema. "Painting a portrait". Mumbai Mirror. Retrieved December 18, 2016.

- ^ Mueller, Christina (November 10, 2022). "Sammy Hagar: The Red Rocker on His Cocktail Book With Guy Fieri, Cabo Wabo Cantina and More". Marin Magazine. Retrieved January 11, 2025.

- ^ "With all of Mill Valley behind him, Niall Shiels-Donegan's electric U.S. Amateur run continues". NBC Sports. August 15, 2025. Retrieved August 19, 2025.

External links

[edit]Mill Valley, California.

Mill Valley, California

View on GrokipediaMill Valley is a residential city in Marin County, California, with a population of 14,203 at the 2020 United States census. Located approximately 14 miles north of San Francisco at the base of Mount Tamalpais and surrounded by redwood forests, it functions primarily as an affluent commuter suburb offering access to outdoor recreation areas such as Muir Woods National Monument and extensive hiking trails.[1] The city spans about 5 square miles, with a population density of roughly 2,800 people per square mile, and features a median age of 47.2 years and a median household income exceeding $208,000 as of 2023, reflecting its high socioeconomic status and low poverty rate of under 5%.[2] Originally settled in the mid-19th century around a sawmill that processed local redwoods for lumber, Mill Valley incorporated in 1900 after transitioning from dairy ranching and early tourism linked to the Mount Tamalpais and Muir Woods Railway.[3] Its economy relies heavily on professional services, with many residents commuting to the San Francisco Bay Area for employment in technology, finance, and other high-wage sectors, while local amenities include a compact downtown with shops, restaurants, and cultural events like the Mill Valley Film Festival.[2] The community's defining characteristics include stringent preservation of its natural environment and small-town aesthetic amid rapid regional growth, though this has contributed to median home prices surpassing $2 million and ongoing debates over housing density and infrastructure capacity.[1] Demographically, over 80% of residents identify as white, with high educational attainment—more than 80% holding at least a bachelor's degree—supporting a lifestyle oriented toward environmentalism and outdoor pursuits rather than heavy industry or large-scale commercial development.[2]

History

Indigenous Peoples and Pre-Settlement Era

The Coast Miwok people inhabited the region encompassing present-day Mill Valley and broader Marin County for several thousand years prior to European contact, as evidenced by archaeological findings including shell middens and stone tools. Sites such as the Anamás Midden in Mill Valley contain layers of discarded oyster shells, fish bones, and mammal remains, indicating sustained human activity dating back millennia, with some Marin County shellmounds estimated at up to 5,000 years old based on excavation depths and associated artifacts.[4][5][6] These middens, accumulated from shellfish processing near Richardson Bay, reflect localized resource exploitation rather than large-scale settlement, with over 600 village sites identified across Coast Miwok territory through surface surveys and ethnohistorical mapping.[7] Pre-contact population densities were low, with estimates for the Hookooekoo area—encompassing Richardson Bay and adjacent valleys like Mill Valley—ranging from 2,000 individuals across multiple small villages, supported by records of dispersed family-based groups rather than centralized communities.[7] Broader Marin County figures suggest several thousand Coast Miwok, inferred from mission-era baptismal tallies and archaeological site densities, though precise counts remain uncertain due to the nomadic nature of their bands and lack of written records. Subsistence relied on hunting terrestrial game such as deer and rabbits, fishing in streams and bays, and gathering coastal shellfish, with seasonal patterns dictating movement: spring and summer focused on estuarine resources near Richardson Bay for clams and fish, while fall emphasized acorn collection from oak woodlands in surrounding hills for year-round staple processing into meal.[8] Tools like mortars and pestles found in local sites corroborate acorn leaching and grinding practices, while bow-and-arrow points indicate hunting efficiency tied to the diverse topography of valleys and ridges.[9] This resource use aligned with ecological availability, minimizing permanent structures in favor of temporary dome-shaped dwellings adapted to migratory cycles.[8]Early European Settlement and Mill Town Origins

European settlement in the Mill Valley area began under Mexican rule with the granting of Rancho Corte Madera del Presidio, a 7,845-acre tract encompassing parts of present-day Mill Valley, to Irish immigrant John Thomas Reed in 1834 by Governor José Figueroa.[10] Reed, who arrived in California in 1826, established operations on the rancho to supply lumber to the Presidio of San Francisco, leveraging the abundant coastal redwoods in the region's canyons.[11] Following the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which transferred California to U.S. control, confirmation of Mexican land grants proceeded amid American influx, though disputes over titles persisted into the 1850s and 1860s.[11] The establishment of a sawmill by Reed around 1833-1835 on Cascade Creek marked the inception of the area's mill town economy, processing redwood logs hauled by oxen from nearby forests to meet demand for construction materials in the growing San Francisco Bay Area.[12] Powered by water from a dammed creek, this facility, the first in Marin County, facilitated resource extraction driven by the post-Gold Rush population surge, which increased California's inhabitants from about 15,000 in 1848 to over 300,000 by 1860, spurring timber needs.[13] Logging focused on second-growth redwoods in Cascade Canyon, with lumber shipped via waterways to urban centers, laying the foundation for transient laborer settlements around the mill site, now Old Mill Park.[14] By the 1850s, the valley featured Reed's sawmill, homestead, and scattered farms alongside nearby ranches like Samuel Throckmorton's on adjacent Rancho Saucelito, attracting workers for logging and initial agriculture.[14] In the 1860s, partitioning of larger ranchos into smaller dairy operations expanded settlement, with leases granted to Portuguese immigrants from the Azores who introduced intensive dairying on cleared grazing lands, supplementing the timber economy with milk production for San Francisco markets.[15] This dual reliance on timber harvesting and pastoral farming characterized early demographic growth, with laborers and smallholders forming nascent communities amid the redwood groves.[16]Incorporation, Railroads, and Industrial Growth

Mill Valley incorporated as a city on September 1, 1900, following elections in August that year, amid growing local advocacy to establish municipal governance independent of earlier land companies.[17] This formalization occurred as the community, previously known as Eastland, benefited from rail infrastructure that had begun transforming the area decades prior. The North Pacific Coast Railroad, a narrow-gauge line, extended service to Mill Valley by 1875, enabling efficient transport of lumber from local sawmills to San Francisco markets and supporting initial industrial activity centered on timber harvesting.[18] The completion of the Mill Valley and Mt. Tamalpais Scenic Railway in August 1896 marked a pivotal development, constructing an 8.19-mile line with 281 curves from the Mill Valley depot to the summit of Mt. Tamalpais, dubbed the "crookedest railroad in the world."[19] This tourist-oriented extension, distinct from freight-focused lines, ferried passengers via steam locomotives and gravity cars, drawing visitors to panoramic views and fostering commuter links to urban centers.[20] Rail access facilitated timber extraction from redwood groves while spurring residential and commercial expansion, with population estimates rising from approximately 900 residents in 1900 to 2,554 by 1920.[21] Industrial growth diversified beyond logging as railroads supported small-scale manufacturing and retail establishments by the 1910s. Lumber-related operations, including mills and supply yards, thrived initially due to reliable transport, but tourism influxes prompted investments in hospitality and services, evidenced by new depots and commercial districts.[22] The scenic railway's operations, peaking before its 1930 closure, underscored this shift, with annual passenger volumes exceeding capacity demands and contributing to economic vitality through visitor spending.[23]Mid-20th Century Development and Suburbanization

During World War II, Mill Valley residents mobilized in support of the national war effort, facing rationing, blackouts, and uncertainty following the Pearl Harbor attack in December 1941.[24] The local economy maintained stability amid broader Marin County contributions, such as the Marinship Shipyard in nearby Sausalito, which employed thousands in Liberty ship construction, though Mill Valley itself saw limited direct industrial expansion.[25] Access to Mount Tamalpais was restricted, with the gravity railroad closing to civilians for security reasons until postwar disuse.[26] Postwar suburbanization accelerated due to Mill Valley's proximity to San Francisco, facilitated by the 1937 Golden Gate Bridge and expanding roadways, drawing commuters from the urban core.[27] The population grew from 4,847 in 1940 to 7,241 in 1950, surging to 10,411 by 1960 and 12,942 by 1970, driven by a Bay Area housing boom that emphasized single-family homes.[28][29][30] This expansion reflected California's statewide construction of millions of units, with Mill Valley incorporating mid-century modern styles amid ranch-style and tract developments tailored to returning veterans and growing families.[31] In the 1960s and 1970s, rapid growth prompted environmental activism in Marin County, including Mill Valley, which balanced development with preservation through anti-logging campaigns and regulatory ordinances.[32] Local efforts by groups like the Marin Conservation League resisted Douglas fir clear-cutting on ridges near Mill Valley, contributing to countywide logging restrictions starting in 1968 and the 1973 Countywide Plan that designated corridors for urban limits and rural protection.[33][34] These measures helped safeguard redwood groves and open spaces, such as those in Cascade Canyon, amid broader sustainable development pushes that curbed unchecked suburban sprawl.[35]Recent Historical Events and Preservation Efforts

In the 1980s, Mill Valley advanced its historic preservation through targeted restorations, including the city's initiation of a historically accurate reconstruction of the Old Mill in Old Mill Park, a site tied to the town's 19th-century lumber industry origins. This project followed intermittent preservation work amid flood damage and aimed to restore the structure's original water-powered design elements using period-appropriate materials.[36] Building on the 1975 adoption of Historic Overlay (H-O) zoning—which designated 27 properties for protection, including elements of the Old Mill area—the community emphasized individual landmark safeguards over broad district formations during the 1980s and 1990s. These measures, combined with resident opposition to high-density proposals that threatened scenic and architectural integrity, empirically constrained urban infill, fostering stable low-density development patterns amid Marin County's broader suburban pressures. For instance, zoning enforcement limited multifamily projects, preserving over 40% of the city's land as open space by the early 2000s and supporting a population increase of only about 10% from 1980 to 2000, compared to faster regional growth.[37] Into the 2000s and 2010s, preservation extended to trail networks integral to the town's historic recreational identity, with Marin County Parks facilitating expansions like enhanced connectivity in the Mt. Tamalpais State Park vicinity, including segments linking Mill Valley to coastal paths. These enhancements, often in partnership with local conservation groups, bolstered empirical outcomes of earlier policies by integrating historic rail corridors—remnants of the 1890s Mt. Tamalpais Scenic Railway—into modern pedestrian infrastructure, thereby sustaining ecological buffers and deterring incompatible development. Ongoing maintenance of sites like the Old Mill has similarly reinforced tourism draws, though quantifiable revenue attribution remains tied to broader visitor economies rather than isolated metrics.[38]Geography

Location and Topography

Mill Valley is situated in Marin County, California, approximately 14 miles north of San Francisco across the Golden Gate Bridge.[39][40] The city's central coordinates are 37°54′21″N 122°32′43″W.[41] This positioning places it within the North Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area, bordered by Richardson Bay to the east and the slopes of Mount Tamalpais to the west. The city covers a land area of 4.78 square miles.[42] Its topography features a marked elevation gradient, beginning near sea level along the shores of Richardson Bay and ascending steeply westward toward the base of Mount Tamalpais, with elevation changes exceeding 1,300 feet over short distances.[43] This rugged terrain, characterized by canyons and forested hills, constrains urban expansion and shapes residential and infrastructural development patterns. Mill Valley lies adjacent to Muir Woods National Monument, approximately 4 miles northwest, and serves as the gateway to Mount Tamalpais State Park.[44] The proximity to these protected coastal redwood ecosystems and mountainous features imposes topographic limitations on land use, promoting clustered settlement in flatter valley floors while preserving steeper slopes.[45]

Geological Features and Natural Resources

Mill Valley lies within the geological province of the California Coast Ranges, underlain predominantly by the Franciscan Complex, a late Mesozoic accretionary prism of accreted oceanic and trench sediments and volcanics formed during subduction. This complex features highly deformed and metamorphosed rocks, including graywacke sandstone, argillite shale, ribbon chert, and pillow basalts, with local exposures of high-grade metamorphic blocks such as eclogite and blueschist.[46][47] The Franciscan rocks in the Mill Valley area exhibit intense folding, faulting, and shearing from tectonic accretion, contributing to the rugged topography of Mount Tamalpais.[48] Proximal fault systems, including segments of the Hayward-Rodgers Creek fault zone extending into Marin County, traverse or border the region, facilitating seismic activity through strike-slip motion. These faults have generated historical earthquakes, such as the 1868 Hayward event (magnitude ~6.8), underscoring the area's vulnerability to ground shaking and associated hazards like landslides on steep Franciscan slopes.[49][50] The principal historical natural resources were timber from coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) groves and mixed oak woodlands covering the uplands, harvested intensively from the 1850s onward to supply sawmills—originating the town's name from early redwood milling operations along local creeks. Redwood logging peaked in the late 19th century, with old-growth stands felled for lumber, but extraction declined sharply after 1900 due to depletion and conservation efforts, culminating in the 1908 federal protection of Muir Woods and subsequent state park designations prohibiting commercial harvest.[51] Oak resources supported secondary uses like fuel and construction but faced similar curtailment under modern preservation regimes.[52] Watersheds draining the Franciscan terrain, such as Arroyo Seco Creek—a perennial stream originating on Mount Tamalpais' eastern flanks—feed into networks like Cascade and Old Mill creeks, channeling runoff that sustains the Mount Tamalpais watershed's reservoirs. This system provides about 75% of Marin County's municipal water supply via rainfall infiltration and surface diversion, with annual yields varying from 10-15 billion gallons in wet years to under 5 billion in dry ones, influencing local hydrology and restricting development to maintain recharge.[53][54] Current land use policies, enforced through federal, state, and county protections, preclude resource extraction, prioritizing watershed integrity and seismic stability over historical exploitation patterns.[55]Climate and Environment

Climatic Patterns and Data

Mill Valley exhibits a Mediterranean climate (Köppen Csb), featuring mild, wet winters and cool, dry summers moderated by its proximity to the Pacific Ocean and San Francisco Bay. Average annual precipitation totals approximately 41 inches, with roughly 78 rainy days concentrated in the wet season from October to May, where over 90% of rainfall occurs, primarily November through March due to Pacific storm tracks. Summers remain arid, with negligible precipitation from May to October, often influenced by coastal fog that suppresses daytime highs and enhances overnight cooling.[56][43] The cool season spans December to March, with average daily highs of 56–59°F and lows of 43–46°F; January marks the coldest month at a mean of about 50°F. The warm season extends from June to October, yielding average highs of 69–72°F and lows of 52–54°F, peaking in September. Year-round humidity remains low, with no muggy days, and temperatures comfortable 86% of the time, rarely exceeding 82°F or falling below 36°F based on 1980–2016 historical data from weather stations and reanalysis models.[43] Extreme temperatures are infrequent owing to marine layer effects; recorded highs have reached 97°F (October 2024) and 96°F (July 2024) during regional heat waves, while lows dip toward freezing only occasionally in winter. Long-term records indicate summer maxima seldom surpass 90°F, aligning with the area's topographic sheltering by Mount Tamalpais.[57][58][43]| Month | Avg. High (°F) | Avg. Low (°F) | Avg. Precipitation (inches) |

|---|---|---|---|

| January | 56 | 43 | 4.5 |

| February | 59 | 44 | 4.3 |

| March | 61 | 45 | 3.0 |

| April | 63 | 46 | 1.5 |

| May | 66 | 49 | 0.6 |

| June | 69 | 52 | 0.2 |

| July | 70 | 53 | 0.0 |

| August | 71 | 53 | 0.0 |

| September | 72 | 54 | 0.2 |

| October | 69 | 52 | 1.2 |

| November | 63 | 48 | 3.0 |

| December | 56 | 43 | 4.5 |

Environmental Risks and Management