Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Multigate device

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Nanoelectronics |

|---|

| Single-molecule electronics |

| Solid-state nanoelectronics |

| Related approaches |

| Portals |

|

|

A multigate device, multi-gate MOSFET or multi-gate field-effect transistor (MuGFET) refers to a metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistor (MOSFET) that has more than one gate on a single transistor. The multiple gates may be controlled by a single gate electrode, wherein the multiple gate surfaces act electrically as a single gate, or by independent gate electrodes. A multigate device employing independent gate electrodes is sometimes called a multiple-independent-gate field-effect transistor (MIGFET). The most widely used multi-gate devices are the FinFET (fin field-effect transistor) and the GAAFET (gate-all-around field-effect transistor), which are non-planar transistors, or 3D transistors.

Multi-gate transistors are one of the several strategies being developed by MOS semiconductor manufacturers to create ever-smaller microprocessors and memory cells, colloquially referred to as extending Moore's law (in its narrow, specific version concerning density scaling, exclusive of its careless historical conflation with Dennard scaling).[1] Development efforts into multigate transistors have been reported by the Electrotechnical Laboratory, Toshiba, Grenoble INP, Hitachi, IBM, TSMC, UC Berkeley, Infineon Technologies, Intel, AMD, Samsung Electronics, KAIST, Freescale Semiconductor, and others, and the ITRS predicted correctly that such devices will be the cornerstone of sub-32 nm technologies.[2] The primary roadblock to widespread implementation is manufacturability, as both planar and non-planar designs present significant challenges, especially with respect to lithography and patterning. Other complementary strategies for device scaling include channel strain engineering, silicon-on-insulator-based technologies, and high-κ/metal gate materials.

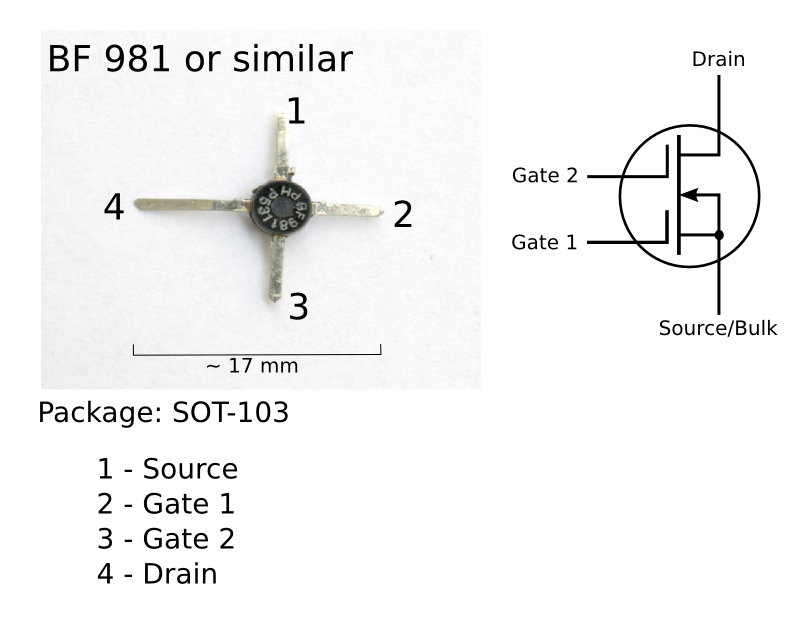

Dual-gate MOSFETs are commonly used in very high frequency (VHF) mixers and in sensitive VHF front-end amplifiers. They are available from manufacturers such as Motorola, NXP Semiconductors, and Hitachi.[3][4][5]

Types

[edit]

Dozens of multigate transistor variants may be found in the literature. In general, these variants may be differentiated and classified in terms of architecture (planar vs. non-planar design) and the number of channels/gates (2, 3, or 4).

Planar double-gate MOSFET (DGMOS)

[edit]A planar double-gate MOSFET (DGMOS) employs conventional planar (layer-by-layer) manufacturing processes to create double-gate MOSFET (metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistor) devices, avoiding more stringent lithography requirements associated with non-planar, vertical transistor structures. In planar double-gate transistors the drain–source channel is sandwiched between two independently fabricated gate/gate-oxide stacks. The primary challenge in fabricating such structures is achieving satisfactory self-alignment between the upper and lower gates.[6]

FlexFET

[edit]FlexFET is a planar, independently double-gated transistor with a damascene metal top gate MOSFET and an implanted JFET bottom gate that are self-aligned in a gate trench. This device is highly scalable due to its sub-lithographic channel length; non-implanted ultra-shallow source and drain extensions; non-epi raised source and drain regions; and gate-last flow. FlexFET is a true double-gate transistor in that (1) both the top and bottom gates provide transistor operation, and (2) the operation of the gates is coupled such that the top gate operation affects the bottom gate operation and vice versa.[7] FlexFET was developed and is manufactured by American Semiconductor, Inc.

FinFET

[edit]

FinFET (fin field-effect transistor) is a type of non-planar transistor, or "3D" transistor (not to be confused with 3D microchips).[8] The FinFET is a variation on traditional MOSFETs distinguished by the presence of a thin silicon "fin" inversion channel on top of the substrate, allowing the gate to make two points of contact: the left and right sides of the fin. The thickness of the fin (measured in the direction from source to drain) determines the effective channel length of the device. The wrap-around gate structure provides a better electrical control over the channel and thus helps in reducing the leakage current and overcoming other short-channel effects.

The first FinFET transistor type was called a depleted lean-channel transistor or "DELTA" transistor, which was first fabricated by Hitachi Central Research Laboratory's Digh Hisamoto, Toru Kaga, Yoshifumi Kawamoto and Eiji Takeda in 1989.[9][10][11] In the late 1990s, Digh Hisamoto began collaborating with an international team of researchers on further developing DELTA technology, including TSMC's Chenming Hu and a UC Berkeley research team including Tsu-Jae King Liu, Jeffrey Bokor, Xuejue Huang, Leland Chang, Nick Lindert, S. Ahmed, Cyrus Tabery, Yang-Kyu Choi, Pushkar Ranade, Sriram Balasubramanian, A. Agarwal and M. Ameen. In 1998, the team developed the first N-channel FinFETs and successfully fabricated devices down to a 17 nm process. The following year, they developed the first P-channel FinFETs.[12] They coined the term "FinFET" (fin field-effect transistor) in a December 2000 paper.[13]

In current usage the term FinFET has a less precise definition. Among microprocessor manufacturers, AMD, IBM, and Freescale describe their double-gate development efforts as FinFET[14] development, whereas Intel avoids using the term when describing their closely related tri-gate architecture.[15] In the technical literature, FinFET is used somewhat generically to describe any fin-based, multigate transistor architecture regardless of number of gates. It is common for a single FinFET transistor to contain several fins, arranged side by side and all covered by the same gate, that act electrically as one, to increase drive strength and performance.[16] The gate may also cover the entirety of the fin(s).

A 25 nm transistor operating on just 0.7 volt was demonstrated in December 2002 by TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company). The "Omega FinFET" design is named after the similarity between the Greek letter omega (Ω) and the shape in which the gate wraps around the source/drain structure. It has a gate delay of just 0.39 picosecond (ps) for the N-type transistor and 0.88 ps for the P-type.

In 2004, Samsung Electronics demonstrated a "Bulk FinFET" design, which made it possible to mass-produce FinFET devices. They demonstrated dynamic random-access memory (DRAM) manufactured with a 90 nm Bulk FinFET process.[12] In 2006, a team of Korean researchers from the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST) and the National Nano Fab Center developed a 3 nm transistor, the world's smallest nanoelectronic device, based on FinFET technology.[17][18] In 2011, Rice University researchers Masoud Rostami and Kartik Mohanram demonstrated that FINFETs can have two electrically independent gates, which gives circuit designers more flexibility to design with efficient, low-power gates.[19]

In 2012, Intel started using FinFETs for its future commercial devices. Leaks suggest that Intel's FinFET has an unusual shape of a triangle rather than rectangle, and it is speculated that this might be either because a triangle has a higher structural strength and can be more reliably manufactured or because a triangular prism has a higher area-to-volume ratio than a rectangular prism, thus increasing switching performance.[20]

In September 2012, GlobalFoundries announced plans to offer a 14-nanometer process technology featuring FinFET three-dimensional transistors in 2014.[21] The next month, the rival company TSMC announced start early or "risk" production of 16 nm FinFETs in November 2013.[22]

In March 2014, TSMC announced that it is nearing implementation of several 16 nm FinFETs die-on wafers manufacturing processes:[23]

- 16 nm FinFET (Q4 2014),

- 16 nm FinFET+ (cca[clarify] Q4 2014),

- 16 nm FinFET "Turbo" (estimated in 2015–2016).

AMD released GPUs using their Polaris chip architecture and made on 14 nm FinFET in June 2016.[24] The company has tried to produce a design to provide a "generational jump in power efficiency" while also offering stable frame rates for graphics, gaming, virtual reality, and multimedia applications.[25]

In March 2017, Samsung and eSilicon announced the tapeout for production of a 14 nm FinFET ASIC in a 2.5D package.[26][27]

Tri-gate transistor

[edit]A tri-gate transistor, also known as a triple-gate transistor, is a type of MOSFET with a gate on three of its sides.[28] A triple-gate transistor was first demonstrated in 1987, by a Toshiba research team including K. Hieda, Fumio Horiguchi and H. Watanabe. They realized that the fully depleted (FD) body of a narrow bulk Si-based transistor helped improve switching due to a reduced body-bias effect.[29][30] In 1992, a triple-gate MOSFET was demonstrated by IBM researcher Hon-Sum Wong.[31]

Intel announced this technology in September 2002.[32] Intel announced "triple-gate transistors" which maximize "transistor switching performance and decreases power-wasting leakage". A year later, in September 2003, AMD announced that it was working on similar technology at the International Conference on Solid State Devices and Materials.[33][34] No further announcements of this technology were made until Intel's announcement in May 2011, although it was stated at IDF 2011, that they demonstrated a working SRAM chip based on this technology at IDF 2009.[35]

On April 23, 2012, Intel released a new line of CPUs, termed Ivy Bridge, which feature tri-gate transistors.[36][37] Intel has been working on its tri-gate architecture since 2002, but it took until 2011 to work out mass-production issues. The new style of transistor was described on May 4, 2011, in San Francisco.[38] It was announced that Intel's factories were expected to make upgrades over 2011 and 2012 to be able to manufacture the Ivy Bridge CPUs.[39] It was announced that the new transistors would also be used in Intel's Atom chips for low-powered devices.[38]

Tri-gate fabrication was used by Intel for the non-planar transistor architecture used in Ivy Bridge, Haswell and Skylake processors. These transistors employ a single gate stacked on top of two vertical gates (a single gate wrapped over three sides of the channel), allowing essentially three times the surface area for electrons to travel. Intel reports that their tri-gate transistors reduce leakage and consume far less power than previous transistors. This allows up to 37% higher speed or a power consumption at under 50% of the previous type of transistors used by Intel.[40][41]

Intel explains: "The additional control enables as much transistor current flowing as possible when the transistor is in the 'on' state (for performance), and as close to zero as possible when it is in the 'off' state (to minimize power), and enables the transistor to switch very quickly between the two states (again, for performance)."[42] Intel has stated that all products after Sandy Bridge will be based upon this design.

The term tri-gate is sometimes used generically to denote any multigate FET with three effective gates or channels.[43]

Gate-all-around FET (GAAFET)

[edit]Gate-all-around FETs (GAAFETs) are the successor to FinFETs, as they can work at sizes below 7 nm. They were used by IBM to demonstrate 5 nm process technology.

GAAFET, also known as a surrounding-gate transistor (SGT),[44][45] is similar in concept to a FinFET except that the gate material surrounds the channel region on all sides. Depending on design, gate-all-around FETs can have two or four effective gates. Gate-all-around FETs have been successfully characterized both theoretically and experimentally.[46][47] They have also been successfully etched onto nanowires of InGaAs, which have a higher electron mobility than silicon.[48]

A gate-all-around (GAA) MOSFET was first demonstrated in 1988, by a Toshiba research team including Fujio Masuoka, Hiroshi Takato, and Kazumasa Sunouchi, who demonstrated a vertical nanowire GAAFET which they called a "surrounding gate transistor" (SGT).[49][50][45] Masuoka, best known as the inventor of flash memory, later left Toshiba and founded Unisantis Electronics in 2004 to research surrounding-gate technology along with Tohoku University.[51] In 2006, a team of Korean researchers from the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST) and the National Nano Fab Center developed a 3 nm transistor, the world's smallest nanoelectronic device, based on gate-all-around (GAA) FinFET technology.[52][18] GAAFET transistors may make use of high-k/metal gate materials. GAAFETs with up to 7 nanosheets have been demonstrated which allow for improved performance and/or reduced device footprint. The widths of the nanosheets in GAAFETs is controllable which more easily allows for the adjustment of device characteristics.[53]

As of 2020, Samsung and Intel have announced plans to mass produce GAAFET transistors (specifically MBCFET transistors) while TSMC has announced that they will continue to use FinFETs in their 3 nm node,[54] despite TSMC developing GAAFET transistors.[55]

Multi-bridge channel (MBC) FET

[edit]A multi-bridge channel FET (MBCFET) is similar to a GAAFET except for the use of nanosheets instead of nanowires.[56] MBCFET is a word mark (trademark) registered in the U.S. to Samsung Electronics.[57] Samsung plans on mass producing MBCFET transistors at the 3 nm node for its foundry customers.[58] Intel is also developing RibbonFET, a variation of MBCFET "nanoribbon" transistors.[59][60] Unlike FinFETs, both the width and the number of the sheets can be varied to adjust drive strength or the amount of current the transistor can drive at a given voltage. The sheets often vary from 8 to 50 nanometers in width. The width of the nanosheets is known as Weff, or effective width.[61][62]

Industry need

[edit]Planar transistors have been the core of integrated circuits for several decades, during which the size of the individual transistors has steadily decreased. As the size decreases, planar transistors increasingly suffer from the undesirable short-channel effect, especially "off-state" leakage current, which increases the idle power required by the device.[63]

In a multigate device, the channel is surrounded by several gates on multiple surfaces. Thus it provides better electrical control over the channel, allowing more effective suppression of "off-state" leakage current. Multiple gates also allow enhanced current in the "on" state, also known as drive current. Multigate transistors also provide a better analog performance due to a higher intrinsic gain and lower channel length modulation.[64] These advantages translate to lower power consumption and enhanced device performance. Nonplanar devices are also more compact than conventional planar transistors, enabling higher transistor density which translates to smaller overall microelectronics.

Integration challenges

[edit]The primary challenges to integrating nonplanar multigate devices into conventional semiconductor manufacturing processes include:

- Fabrication of a thin silicon "fin" tens of nanometers wide

- Fabrication of matched gates on multiple sides of the fin

Compact modeling

[edit]

BSIMCMG106.0.0,[65] officially released on March 1, 2012 by UC Berkeley BSIM Group, is the first standard model for FinFETs. BSIM-CMG is implemented in Verilog-A. Physical surface-potential-based formulations are derived for both intrinsic and extrinsic models with finite body doping. The surface potentials at the source and drain ends are solved analytically with poly-depletion and quantum mechanical effects. The effect of finite body doping is captured through a perturbation approach. The analytic surface potential solution agrees closely with the 2-D device simulation results. If the channel doping concentration is low enough to be neglected, computational efficiency can be further improved by a setting a specific flag (COREMOD = 1).

All of the important multi-gate (MG) transistor behavior is captured by this model. Volume inversion is included in the solution of Poisson's equation, hence the subsequent I–V formulation automatically captures the volume-inversion effect. Analysis of electrostatic potential in the body of MG MOSFETs provided a model equation for short-channel effects (SCE). The extra electrostatic control from the end gates (top/bottom gates) (triple or quadruple-gate) is also captured in the short-channel model.

See also

[edit]- Three-dimensional integrated circuit

- Semiconductor device

- Clock gating

- High-κ dielectric

- Next-generation lithography

- Extreme ultraviolet lithography

- Immersion lithography

- Strain engineering

- Very large scale integration (VLSI)

- Neuromorphic engineering

- Bit slicing

- 3D printing

- Silicon on insulator (SOI)

- MOSFET

- Floating-gate MOSFET

- Transistor

- BSIM

- High-electron-mobility transistor

- Field-effect transistor

- JFET

- Tetrode transistor

- Pentode transistor

- Memristor

- Quantum circuit

- Quantum logic gate

- Transistor model

- Die shrink

References

[edit]- ^ Risch, L. "Pushing CMOS Beyond the Roadmap", Proceedings of ESSCIRC, 2005, p. 63.

- ^ Table39b Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Motorola 3N201 Datasheet - Datasheetspdf.com". Datasheetpdf.com. Retrieved 2023-01-08.

- ^ "3SK45 Datasheet - Alldatasheet.com" (PDF). Retrieved 2023-01-08.

- ^ "BF1217WR Datasheet" (PDF). Retrieved 2023-01-08.

- ^ Wong, H-S.; Chan, K.; Taur, Y. (December 10, 1997). "Self-aligned (Top and bottom) double-gate MOSFET with a 25 nm thick silicon channel". International Electron Devices Meeting. IEDM Technical Digest. pp. 427–430. doi:10.1109/IEDM.1997.650416. ISBN 978-0-7803-4100-5. ISSN 0163-1918. S2CID 20947344.

- ^ Wilson, D.; Hayhurst, R.; Oblea, A.; Parke, S.; Hackler, D. "Flexfet: Independently-Double-Gated SOI Transistor With Variable Vt and 0.5V Operation Achieving Near Ideal Subthreshold Slope" SOI Conference, 2007 IEEE International [1]

- ^ "What is Finfet?". Computer Hope. April 26, 2017. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ^ "IEEE Andrew S. Grove Award Recipients". IEEE Andrew S. Grove Award. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ^ Colinge, J.P. (2008). FinFETs and Other Multi-Gate Transistors. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 11 & 39. ISBN 978-0-387-71751-7.

- ^ Hisamoto, D.; Kaga, T.; Kawamoto, Y.; Takeda, E. (December 1989). "A fully depleted lean-channel transistor (DELTA)-a novel vertical ultra thin SOI MOSFET". International Technical Digest on Electron Devices Meeting. pp. 833–836. doi:10.1109/IEDM.1989.74182. S2CID 114072236.

- ^ a b Tsu-Jae King, Liu (June 11, 2012). "FinFET: History, Fundamentals and Future". University of California, Berkeley. Symposium on VLSI Technology Short Course. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ Hisamoto, Digh; Hu, Chenming; Bokor, J.; King, Tsu-Jae; Anderson, E.; et al. (December 2000). "FinFET-a self-aligned double-gate MOSFET scalable to 20 nm". IEEE Transactions on Electron Devices. 47 (12): 2320–2325. Bibcode:2000ITED...47.2320H. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.211.204. doi:10.1109/16.887014.

- ^ "AMD Newsroom". Amd.com. 2002-09-10. Archived from the original on 2010-05-13. Retrieved 2015-07-07.

- ^ "Intel Silicon Technology Innovations". Intel.com. Archived from the original on September 3, 2011. Retrieved 2014-03-10.

- ^ Shimpi, Anand Lal. "Intel Announces first 22nm 3D Tri-Gate Transistors, Shipping in 2H 2011". www.anandtech.com. Archived from the original on July 19, 2012.

- ^ "Still Room at the Bottom.(nanometer transistor developed by Yang-kyu Choi from the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology )", Nanoparticle News, 1 April 2006, archived from the original on 6 November 2012

- ^ a b Lee, Hyunjin; et al. (2006). "Sub-5nm All-Around Gate FinFET for Ultimate Scaling". 2006 Symposium on VLSI Technology, 2006. Digest of Technical Papers. pp. 58–59. doi:10.1109/VLSIT.2006.1705215. hdl:10203/698. ISBN 978-1-4244-0005-8. S2CID 26482358.

- ^ Rostami, M.; Mohanram, K. (2011). "Dual-Vth$ Independent-Gate FinFETs for Low Power Logic Circuits". IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems. 30 (3): 337–349. doi:10.1109/TCAD.2010.2097310. hdl:1911/72088. S2CID 2225579.

- ^ "Intel's FinFETs are less fin and more triangle". EE Times. Archived from the original on 2013-05-31. Retrieved 2014-03-10.

- ^ "Globalfoundries looks leapfrog fab rivals with new process". EE Times. Archived from the original on 2013-02-02. Retrieved 2014-03-10.

- ^ "TSMC taps ARM's V8 on road to 16 nm FinFET". EE Times. Archived from the original on 2012-11-01. Retrieved 2014-03-10.

- ^ Josephine Lien; Steve Shen (31 March 2014). "TSMC likely to launch 16 nm FinFET+ process at year-end 2014, and "FinFET Turbo" later in 2015-16". DIGITIMES. Retrieved 2014-03-31.

- ^ Smith, Ryan. "The AMD Radeon RX 480 Preview: Polaris Makes Its Mainstream Mark". Archived from the original on June 30, 2016. Retrieved 2018-06-03.

- ^ "AMD Demonstrates Revolutionary 14nm FinFET Polaris GPU Architecture". AMD. 4 January 2016. Retrieved 2016-01-04.

- ^ "High-performance, high-bandwidth IP platform for Samsung 14LPP process technology". 2017-03-22.

- ^ "Samsung and eSilicon Taped Out 14nm Network Processor with Rambus 28G SerDes Solution". 2017-03-22.

- ^ Colinge, J.P. (2008). FinFETs and Other Multi-Gate Transistors. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-387-71751-7.

- ^ Hieda, K.; Horiguchi, Fumio; Watanabe, H.; Sunouchi, Kazumasa; Inoue, I.; Hamamoto, Takeshi (December 1987). "New effects of trench isolated transistor using side-wall gates". 1987 International Electron Devices Meeting. pp. 736–739. doi:10.1109/IEDM.1987.191536. S2CID 34381025.

- ^ Brozek, Tomasz (2017). Micro- and Nanoelectronics: Emerging Device Challenges and Solutions. CRC Press. pp. 116–7. ISBN 978-1-351-83134-5.

- ^ Wong, Hon-Sum (December 1992). "Gate-current injection and surface impact ionization in MOSFET's with a gate induced virtual drain". International Technical Digest on Electron Devices Meeting. pp. 151–154. doi:10.1109/IEDM.1992.307330. ISBN 0-7803-0817-4. S2CID 114058374.

- ^ High Performance Non-Planar Tri-gate Transistor Architecture; Dr. Gerald Marcyk. Intel, 2002

- ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ "AMD Details Its Triple-Gate Transistors". Xbitlabs.com. Archived from the original on 2014-03-10. Retrieved 2014-03-10.

- ^ "IDF 2011: Intel Looks to Take a Bite Out of ARM, AMD With 3D FinFET Tech". DailyTech. Archived from the original on 2014-03-10. Retrieved 2014-03-10.

- ^ Miller, Michael J. "Intel Releases Ivy Bridge: First Processor with "Tri-Gate" Transistor". PC Magazine. Archived from the original on 2019-12-28. Retrieved 2012-04-23.

- ^ "Intel Reinvents Transistors Using New 3-D Structure". Intel. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- ^ a b "Transistors go 3D as Intel re-invents the microchip". Ars Technica. 5 May 2011. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ Murray, Matthew (4 May 2011). "Intel's New Tri-Gate Ivy Bridge Transistors: 9 Things You Need to Know". PC Magazine. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ Cartwright J. (2011). "Intel enters the third dimension". Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2011.274. Retrieved 2015-05-10.

- ^ Intel to Present on 22-nm Tri-gate Technology at VLSI Symposium (ElectroIQ 2012) Archived April 15, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Below 22nm, spacers get unconventional: Interview with ASM". ELECTROIQ. Retrieved 2011-05-04.

- ^ Dan Grabham (2011-05-06). "Intel's Tri-Gate transistors: everything you need to know". TechRadar. Retrieved 2022-01-21.

- ^ Claeys, C.; Murota, J.; Tao, M.; Iwai, H.; Deleonibus, S. (2015). ULSI Process Integration 9. The Electrochemical Society. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-60768-675-0.

- ^ a b Ishikawa, Fumitaro; Buyanova, Irina (2017). Novel Compound Semiconductor Nanowires: Materials, Devices, and Applications. CRC Press. p. 457. ISBN 978-1-315-34072-2.

- ^ Singh, N.; Agarwal, A.; Bera, L. K.; Liow, T. Y.; Yang, R.; Rustagi, S. C.; Tung, C. H.; Kumar, R.; Lo, G. Q.; Balasubramanian, N.; Kwong, D. (2006). "High-Performance fully depleted Silicon Nanowire Gate-All-Around CMOS devices". IEEE Electron Device Letters. 27 (5): 383–386. Bibcode:2006IEDL...27..383S. doi:10.1109/LED.2006.873381. ISSN 0741-3106. S2CID 45576648.

- ^ Dastjerdy, E.; Ghayour, R.; Sarvari, H. (August 2012). "Simulation and analysis of the frequency performance of a new silicon nanowire MOSFET structure". Physica E. 45: 66–71. Bibcode:2012PhyE...45...66D. doi:10.1016/j.physe.2012.07.007.

- ^ Gu, J. J.; Liu, Y. Q.; Wu, Y. Q.; Colby, R.; Gordon, R. G.; Ye, P. D. (December 2011). "First experimental demonstration of gate-all-around III–V MOSFETs by top-down approach" (PDF). 2011 International Electron Devices Meeting. pp. 33.2.1–33.2.4. arXiv:1112.3573. doi:10.1109/IEDM.2011.6131662. ISBN 978-1-4577-0505-2. S2CID 2116042. Retrieved 2015-05-10.

- ^ Masuoka, Fujio; Takato, Hiroshi; Sunouchi, Kazumasa; Okabe, N.; Nitayama, Akihiro; Hieda, K.; Horiguchi, Fumio (December 1988). "High performance CMOS surrounding gate transistor (SGT) for ultra high density LSIs". Technical Digest, International Electron Devices Meeting. pp. 222–225. doi:10.1109/IEDM.1988.32796. S2CID 114148274.

- ^ Brozek, Tomasz (2017). Micro- and Nanoelectronics: Emerging Device Challenges and Solutions. CRC Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-1-351-83134-5.

- ^ "Company Profile". Unisantis Electronics. Archived from the original on 22 February 2007. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- ^ "Still Room at the Bottom". Nanoparticle News. 1 April 2006. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- ^ LaPedus, Mark (25 January 2021). "New Transistor Structures At 3nm/2nm". Semiconductor Engineering. Retrieved 23 December 2022.

- ^ Cutress, Ian. "Where are my GAA-FETs? TSMC to Stay with FinFET for 3nm". AnandTech.com. Archived from the original on August 26, 2020.

- ^ "TSMC Plots an Aggressive Course for 3 nm Lithography and Beyond - ExtremeTech". www.extremetech.com.

- ^ Cutress, Ian. "Samsung Announces 3 nm GAA MBCFET PDK, Version 0.1". AnandTech.com. Archived from the original on May 15, 2019.

- ^ "MBCFET Trademark of Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd. - Registration Number 5495359 - Serial Number 87447776 :: Justia Trademarks". trademarks.justia.com. Retrieved 2020-01-16.

- ^ "Samsung at foundry event talks about 3nm, MBCFET developments". techxplore.com.

- ^ "Scaling Down: Intel Boasts RibbonFET and PowerVia as Next IC Design Solution - News". www.allaboutcircuits.com. Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ^ Cutress, Ian. "Intel to use Nanowire/Nanoribbon Transistors in Volume 'in Five Years'". AnandTech.com. Archived from the original on June 22, 2020.

- ^ "Samsung's 3-nm Tech Shows Nanosheet Transistor Advantage". IEEE Spectrum.

- ^ "Nanosheets: IBM's Path to 5-Nanometer Transistors". IEEE Spectrum.

- ^ Subramanian V (2010). "Multiple gate field-effect transistors for future CMOS technologies". IETE Technical Review. 27 (6): 446–454. doi:10.4103/0256-4602.72582 (inactive 12 July 2025). Archived from the original on March 23, 2012.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ Subramanian (5 Dec 2005). "Device and circuit-level analog performance trade-offs: A comparative study of planar bulk FETs versus FinFETs". IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting, 2005. IEDM Technical Digest. pp. 898–901. doi:10.1109/IEDM.2005.1609503. ISBN 0-7803-9268-X. S2CID 32683938.

- ^ "BSIMCMG Model". UC Berkeley. Archived from the original on 2012-07-21.

External links

[edit]Multigate device

View on GrokipediaPrinciples and advantages

Basic operation

A multigate device is a variant of the metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistor (MOSFET) featuring two or more gates that surround the channel region, thereby enhancing electrostatic control over the channel potential compared to conventional single-gate MOSFETs.[2] This structure allows for superior modulation of carrier flow in the channel by applying voltages to multiple gates simultaneously, which collectively influence the electric field in the semiconductor body.[10] In multigate devices, channel conduction occurs through a thin silicon body where the multiple gates modulate the potential distribution in three-dimensional space, contrasting with the primarily two-dimensional control in single-gate devices that limits gate influence to one surface.[11] This 3D modulation enables more uniform field penetration into the channel volume, facilitating efficient inversion and transport of charge carriers from source to drain when the gate voltage exceeds the threshold. Short-channel effects, such as drain-induced barrier lowering and threshold voltage roll-off, are mitigated through volume inversion, where inversion charge carriers distribute throughout the channel volume rather than confining to the gate oxide interface, thereby strengthening gate dominance over the channel potential and reducing subthreshold leakage.[11][10] The basic current-voltage (I-V) characteristics of multigate devices exhibit enhanced performance, particularly in the subthreshold region, where the subthreshold swing ideally approaches the thermodynamic limit of 60 mV/decade at room temperature due to improved electrostatic integrity and minimal short-channel perturbations.[10] In the above-threshold regime, the drive current benefits from higher effective channel width without increasing the device footprint, leading to steeper I-V curves and better on-off ratios. For conceptual illustration, a double-gate configuration typically depicts a planar or fin-shaped silicon channel film sandwiched between two parallel gates separated by thin gate oxides, enabling symmetric control from opposite sides; in contrast, a surround-gate (or gate-all-around) setup shows a cylindrical or nanowire channel fully enveloped by a conformal gate electrode on all sides, maximizing capacitive coupling for the strongest short-channel effect suppression.[2]Performance benefits

Multigate devices provide superior electrostatic control over the channel compared to traditional single-gate MOSFETs, primarily by surrounding the channel with multiple gates, which effectively reduces off-state leakage current. This enhanced control suppresses subthreshold leakage paths, enabling significantly lower power consumption while maintaining performance. For instance, in simulations of 22 nm devices, double-gate MOSFETs exhibit an off-state current (Ioff) of 1.03 × 10^{-10} A/μm, over an order of magnitude lower than the 1.976 × 10^{-9} A/μm observed in conventional single-gate NMOS devices under similar conditions.[12] The multi-gate configuration increases the effective channel width and improves carrier transport, leading to enhanced on-state drive current (Ion) and transconductance (gm). By distributing the gate control around the channel, source/drain series resistance is reduced, boosting overall current drive without increasing the device footprint. Representative simulations show Ion values of 1.312 × 10^{-4} A/μm in double-gate structures, comparable to or exceeding single-gate devices while offering better efficiency.[12] This results in higher transconductance, with multigate devices demonstrating up to 20-30% improvement over planar MOSFETs at equivalent leakage levels due to minimized scattering and improved mobility.[13] Multigate devices excel in mitigating short-channel effects (SCEs), including drain-induced barrier lowering (DIBL) and threshold voltage (Vth) roll-off, through volumetric gate control that confines the electric field more effectively. DIBL, which degrades off-state performance in single-gate devices, is substantially reduced; for example, double-gate MOSFETs achieve a DIBL of 0.0422 V at 22 nm gate length, compared to 0.166 V in single-gate NMOS.[12] Similarly, Vth roll-off is minimized, preserving device stability as dimensions shrink. The subthreshold swing (SS), a key indicator of switching efficiency, approaches the theoretical Boltzmann limit of 60 mV/dec more closely in multigate devices, with values around 70-80 mV/dec versus 90-140 mV/dec in single-gate counterparts for short channels.[14] Electrostatic integrity is quantified by a lower natural scaling length (λ), often 20-50% smaller in double-gate versus single-gate structures, enhancing SCE immunity.[13] These improvements translate to superior on/off current ratios (Ion/Ioff), a critical metric for low-power, high-speed applications. Multigate devices typically achieve ratios exceeding 10^6-10^7, far surpassing the 10^4-10^5 common in single-gate MOSFETs at sub-20 nm scales. The following table summarizes representative performance metrics from TCAD simulations of 22 nm n-channel devices with low channel doping (1 × 10^{15} cm^{-3}) and 1.1 nm oxide thickness:| Parameter | Single-Gate NMOS | Double-Gate MOSFET |

|---|---|---|

| Subthreshold Swing (mV/dec) | 139.4 | 127.2 |

| DIBL (V) | 0.166 | 0.0422 |

| Ion (A/μm) | 1.6 × 10^{-4} | 1.312 × 10^{-4} |

| Ioff (A/μm) | 1.976 × 10^{-9} | 1.03 × 10^{-10} |

| Ion/Ioff Ratio | ~8.1 × 10^4 | ~1.3 × 10^6 |

Historical development

Early concepts

The concept of multigate devices emerged in the late 20th century as researchers sought to improve gate control over the channel in MOSFETs to mitigate short-channel effects during scaling. In 1980, Toshihiro Sekigawa proposed a planar double-gate MOSFET structure in a patent, envisioning two gates on opposite sides of a thin silicon film to enhance electrostatic control without relying on a bulk substrate.[17] This idea built on earlier thin-film transistor concepts but focused on silicon-on-insulator (SOI) compatibility for better isolation and reduced parasitic capacitance. Theoretical foundations were further developed in the mid-1980s, with a seminal 1984 publication introducing the XMOS double-gate SOI MOSFET, characterized by its cross-shaped channel resembling an "X" under dual gates for improved volume inversion.[18] The landmark 1987 paper by Francis Balestra and colleagues demonstrated through simulations and analysis that double-gate SOI transistors could achieve volume inversion, leading to significantly enhanced transconductance (up to 2.4 times higher) and reduced threshold voltage variability compared to single-gate devices, while suppressing short-channel effects in films thinner than 20 nm.[19] These works highlighted the potential for multigate structures to maintain ideal subthreshold slopes near 60 mV/decade, a key advantage over conventional MOSFETs. Early patents and papers in the late 1980s also explored vertical and surround-gate configurations to enable better scaling. In 1988, a Toshiba team led by Hiroshi Takato, Kazumasa Sunouchi, and Fujio Masuoka demonstrated the first gate-all-around (GAA) MOSFET, termed the surrounding-gate transistor (SGT), with a vertical cylindrical channel fully enveloped by the gate, achieving gate lengths as short as 0.1 μm and demonstrating superior short-channel effect immunity. The following year, 1989, saw the experimental fabrication of the DELTA (fully DEpleted Lean-channel TrAnsistor) by Digh Hisamoto and colleagues at Hitachi, a vertical double-gate SOI device with a fin-like silicon island standing on its edge, serving as an early prototype that operated with effective channel control in sub-100 nm regimes.[20] Experimental demonstrations accelerated in the 1990s, with IBM researchers achieving a milestone in 1997 through the fabrication of a self-aligned top-and-bottom double-gate SOI MOSFET featuring a 25 nm thick silicon channel. This prototype, developed by Hon-Sum Philip Wong and team, utilized wafer bonding and chemical-mechanical polishing to align gates precisely, yielding devices with gate lengths down to 50 nm, near-ideal subthreshold slopes of 65 mV/decade, and drive currents 20% higher than equivalent single-gate SOI transistors.[21] Early research identified significant fabrication challenges, particularly precise gate alignment in planar double-gate structures, where misalignment could lead to asymmetric operation, increased off-state leakage, and degraded short-channel control. Vertical and surround-gate designs partially addressed this by inherent symmetry but introduced complexities in etching uniform channels and depositing conformal gate dielectrics. These hurdles limited initial implementations to research prototypes pre-2000, paving the way for 3D architectures like fin-based concepts that transitioned from planar double-gate ideas toward more scalable geometries.Key advancements

The development of multigate devices accelerated in the early 2000s with the introduction of the FinFET architecture, pioneered by researchers at the University of California, Berkeley under Chenming Hu, who demonstrated the first functional FinFET devices in 2000, enabling superior gate control over the channel compared to planar transistors.[22] IBM followed with experimental demonstrations of FinFETs integrated into CMOS circuits around 2002, validating their scalability for sub-50 nm nodes through improved short-channel effects suppression.[23] These efforts laid the groundwork for industry adoption, shifting from theoretical multi-gate concepts to practical implementations that addressed leakage and performance limits in scaling beyond 90 nm. Intel marked a pivotal commercial milestone in 2011 by adopting tri-gate transistors— an evolution of FinFETs— in its 22 nm process node for the Ivy Bridge microprocessor, achieving up to 37% higher performance or 50% lower power than the prior 32 nm planar technology.[24] By 2014, Intel transitioned to second-generation FinFETs in its 14 nm process, incorporating optimized fin dimensions and high-k metal gates, which delivered 1.4x transistor density and sustained drive currents for Broadwell processors.[25] This adoption propelled multigate devices into high-volume production, influencing competitors like TSMC and Samsung to follow suit at similar nodes. Advancements in gate-all-around (GAA) architectures emerged as the next frontier, with Samsung announcing its multi-bridge-channel FET (MBCFET), a nanosheet-based GAA variant, in 2019 for the 3 nm node, promising 30% higher performance and 50% lower power than 5 nm FinFETs.[26] Samsung initiated production of 3 nm GAA chips in 2022, utilizing stacked nanosheets for enhanced electrostatic control and enabling denser logic integration.[27] Intel revealed its RibbonFET, another nanosheet GAA implementation, in 2021 for the Intel 20A node (equivalent to ~2 nm), but later shelved 20A in favor of the 18A node, targeting volume production of 18A in 2025 with backside power delivery (PowerVia) for reduced resistance and improved scaling.[28][29] In 2024-2025, innovations extended multigate concepts to novel materials and structures, including 2D multi-fin FETs using bismuth oxyselenide (Bi₂O₂Se) fins integrated via ledge-guided epitaxy, which achieved high on/off ratios exceeding 10⁸ and drive currents over 500 μA/μm for ultra-scaled logic applications below 1 nm effective channel length.[30] For power electronics, GaN-based GAAFETs advanced with high-k wrapped dielectrics, demonstrating cutoff frequencies above 1 THz and transconductance gains of 163% over conventional designs, suited for high-voltage RF and efficient switching in electric vehicles.[31] Node scaling milestones underscore the evolution: tri-gate at 22 nm enabled 2x density over 32 nm, FinFET refinements at 14 nm and 7 nm pushed gate lengths below 20 nm with EUV lithography, while 5 nm marked the FinFET limit before GAA at 3 nm and sub-2 nm projections, forecasting continued density doubling through stacked nanosheets and complementary FETs by 2025.[32] These advancements have driven multigate adoption across logic and memory, briefly referencing performance benefits like reduced variability for reliable circuit operation.Device architectures

Double-gate MOSFETs

The planar double-gate MOSFET (DGMOS) consists of a thin silicon body sandwiched between two opposing gates, each separated by a gate oxide layer, enabling superior electrostatic control over the channel potential from both sides compared to conventional single-gate structures.[33] This configuration suppresses short-channel effects by confining the channel depletion regions and reducing leakage currents, making it suitable for nanoscale applications. Double-gate MOSFETs operate in two primary modes depending on gate connectivity. In the tied-gate mode, both gates are electrically connected and driven by the same voltage, providing symmetric control and effectively doubling the gate capacitance for enhanced drive current.[33] Conversely, in the independent-gate mode, the gates are biased separately, allowing for multiple-independent-gate field-effect transistor (MIGFET) operation where one gate can modulate the channel while the other adjusts performance parameters like threshold voltage.[34] For symmetric structures, the threshold condition in both modes is governed by the average gate voltage, expressed as: where is the effective threshold voltage, and , are the voltages on the front and back gates, respectively; this simplifies to when gates are tied ().[35] A notable variant is the FlexFET, an SOI-based planar independent double-gate MOSFET that employs back-gate bias to achieve flexible dynamic threshold voltage tuning, enabling reconfigurability for low-power and high-performance circuits without altering the front-gate drive.[36] The simplicity of planar double-gate designs facilitated early scaling demonstrations, with prototypes in the 1990s and 2000s—such as those exploring ultrathin-body SOI integration—showcasing reduced subthreshold leakage and improved on-current densities for gate lengths down to 50 nm. However, these structures exhibit poor electrostatic control at the channel edges due to fringing fields and parasitic capacitances, limiting further width scaling and motivating the evolution toward three-dimensional architectures.[37]FinFETs

FinFETs feature a vertical silicon "fin" that serves as the channel, with the gate electrode wrapping around three sides of the fin in a tri-gate configuration, enabling superior electrostatic control over the channel compared to traditional planar MOSFETs.[38] This 3D architecture, first conceptualized as a double-gate structure but evolved into tri-gate for enhanced performance, allows for effective scaling below 20 nm gate lengths by suppressing short-channel effects through improved gate-to-channel coupling.[39] The tri-gate design specifically provides better control over the fin corners, mitigating leakage and variability issues that are more pronounced in double-gate fins.[40] Key structural parameters of FinFETs include fin width (W_fin), fin height (H_fin), and fin pitch, which directly influence drive current, capacitance, and density.[38] The effective channel width (W_eff) in a tri-gate FinFET is calculated as W_eff = 2 H_fin + W_fin for a single fin, allowing designers to tune performance by adjusting these dimensions while maintaining aspect ratios suitable for fabrication.[38] For instance, narrower fins (typically 5-10 nm) enhance gate control but require precise lithography to avoid variability, while taller fins increase W_eff and current drive at the cost of higher parasitics.[41] In logic applications, tri-gate FinFETs have been pivotal for high-performance computing, with widespread adoption in advanced nodes such as Intel's 14 nm, 10 nm, and 7 nm processes, TSMC's 16 nm and 7 nm technologies, and Samsung's 14 nm and 7 nm nodes, delivering up to 40-50% performance gains or power reductions over prior planar devices.[42] These implementations leverage the tri-gate's ability to operate at lower voltages with reduced leakage, enabling denser integration in microprocessors and SoCs.[43] Variations in FinFET design include single-, double-, and multi-fin configurations, where multiple parallel fins are used to scale drive current proportionally with the number of fins (n), as W_eff ≈ n (2 H_fin + W_fin), without significantly increasing the footprint.[38] Double-fin designs offer a balance for moderate current needs, while multi-fin setups (e.g., 3-4 fins) are employed in high-drive logic gates to boost on-state current by up to 2-4 times compared to single-fin devices.[44] Despite these advantages, FinFETs face challenges from fin width variability, stemming from lithography and etching non-uniformities, which can cause threshold voltage shifts of 50-100 mV and impact circuit yield in sub-10 nm nodes.[45] Additionally, parasitic capacitance—particularly outer and inner fringing components—increases with fin height and pitch, potentially degrading switching speeds by 10-20% in high-frequency applications unless mitigated through optimized spacer dielectrics.[46]Gate-all-around FETs

Gate-all-around field-effect transistors (GAAFETs) enclose the channel on all four sides with the gate electrode, providing multi-directional gate control around the charge channel for enhanced electrostatic control, reduced short-channel effects, improved speed, efficiency, and lower power consumption compared to previous designs like FinFETs in nanoscale devices.[47][48][15] This structure typically employs silicon nanowires or nanosheets as the channel material, where the gate dielectric and metal fully surround the channel to maximize gate-to-channel coupling. In nanowire GAAFETs, the cylindrical geometry leads to a specific expression for the gate capacitance, which is essential for understanding device performance and scaling. The gate capacitance for a cylindrical nanowire is given by where is the permittivity of the gate dielectric, is the gate length, is the gate oxide thickness, and is the channel radius. This formula highlights the logarithmic dependence on the oxide-to-channel radius ratio, allowing for precise modeling of capacitance in sub-5 nm regimes.[48][49] Nanosheet FETs (NSFETs), a variant of GAAFETs, utilize multiple horizontal silicon nanosheets stacked vertically as the channel, with the gate wrapping around each sheet individually. This stacked configuration increases the effective channel width, thereby boosting drive current while maintaining excellent gate control and suppressing leakage. For instance, NSFETs can achieve higher on-state currents per unit footprint compared to single-wire structures due to the parallel conduction paths provided by the sheets. The vertical stacking capability of GAAFETs enables advanced architectures like complementary field-effect transistors (CFETs), where n-type and p-type GAAFETs are stacked to deliver up to 30-50% area reduction and enhanced performance in classical computing applications.[50][51][52][53] Samsung's multi-bridge-channel FET (MBCFET) implements GAAFET technology at the 3 nm node using multiple parallel horizontal nanosheets as bridges, enabling tunable channel widths for optimized performance in logic and memory applications. This design allows for varied numbers of nanosheets in pull-up, pull-down, and pass-gate transistors, enhancing SRAM density and power efficiency. MBCFET production began in 2022, demonstrating up to 23% performance improvement and 45% power reduction over 5 nm FinFETs. This architecture is further evolved for Samsung's 2 nm SF2 process node, with risk production targeted for late 2025 and high-volume manufacturing in 2026.[27][49][54][55] Intel's RibbonFET represents another GAAFET evolution, featuring wider ribbon-like channels instead of narrow nanowires or sheets to support higher drive currents at 2 nm-class nodes like Intel 18A. Introduced for production in 2025, RibbonFET provides improved electrostatics and scalability for high-performance computing, integrated with backside power delivery for reduced resistance.[6][56] TSMC's N2 process employs nanosheet GAAFETs, building on pioneering research by IBM, as a successor to FinFETs, entering mass production in the second half of 2025. This architecture offers enhanced drive current, lower leakage, and up to 15% area reduction compared to the prior 3 nm FinFET node, with strong adoption in mobile and high-performance computing applications.[5][57] Recent advancements in 2024 and 2025 have focused on integrating two-dimensional (2D) materials, such as transition metal dichalcogenide (TMDC) nanosheets like monolayer MoS₂, into GAAFETs to overcome silicon's mobility limits at sub-3 nm scales. These 2D GAA structures, employing advanced gate stacks, exhibit on/off ratios exceeding 10⁸ and on-state currents over 400 μA/μm, with gate-first processes enabling scaling to 50 nm channels for future complementary FETs and better performance in classical computing. Additionally, GaN-based GAAFETs have emerged for RF and power applications, leveraging GaN's wide bandgap for high-frequency operation and efficiency, with designs incorporating high-k spacers achieving cutoff frequencies over 100 GHz and suitability for low-power RF circuitry.[58][59][60][16]Fabrication techniques

Structural formation

The structural formation of multigate devices involves precise patterning and etching processes to create three-dimensional channel geometries that enable multiple gates to surround the channel, enhancing electrostatic control. For FinFETs, which represent an early multigate architecture, fin formation begins with lithography to define narrow silicon fins on a bulk or silicon-on-insulator substrate. Advanced techniques such as extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography are employed for sub-10 nm features, allowing high-resolution patterning of fin widths typically below 10 nm.[61] Sidewall image transfer (SIT) is a key method to achieve dense, uniform fins by using sacrificial spacers to double the pattern density from a coarser lithographic mask, followed by selective etching to transfer the pattern into the silicon.[62] Dry etching, often via reactive ion etching (RIE) with plasmas like O₂ or Cl₂-based chemistries, shapes the fins to high aspect ratios (up to 10:1 or more), ensuring vertical sidewalls while minimizing damage to the channel surface.[63] In gate-all-around (GAA) FETs, such as nanosheet or nanowire variants, structural formation emphasizes vertical stacking of channel layers to maximize gate wrapping. Nanosheet stacking starts with epitaxial growth of alternating silicon (Si) and silicon-germanium (SiGe) layers on a substrate, where SiGe serves as sacrificial material due to its higher etch selectivity.[64] This superlattice is formed via chemical vapor deposition (CVD) at temperatures around 600–700°C, achieving layer thicknesses of 5–10 nm for channels and 10–20 nm for sacrificial layers, enabling stacked heights of 50–100 nm for multi-channel devices.[65] Channel release in GAA structures occurs after dummy gate removal, involving selective wet etching of the SiGe sacrificial layers using solutions like HCl or NH₄OH, which exploit the Ge content (typically 20–50%) for etch rates differing by over 100:1 compared to Si.[66] Inner spacers are formed prior to channel release by laterally etching the sacrificial layers under the gate sidewall and filling the voids with a low-k dielectric via atomic layer deposition (ALD), preventing parasitic capacitance between channel and source/drain regions. Gate stack deposition in multigate devices universally adopts high-k/metal gate (HKMG) processes to replace conventional polysilicon gates, integrated via the replacement metal gate (RMG) flow. After fin or nanosheet patterning and source/drain epitaxy, a dummy polysilicon gate is removed, exposing the channel for conformal deposition of high-k dielectrics (e.g., HfO₂, 1–2 nm equivalent oxide thickness) using ALD for uniform coverage on three or four sides.[67] Metal work-function layers (e.g., TiN or TaN) and fill metals (e.g., W or Al) follow via physical vapor deposition (PVD) or ALD, ensuring low threshold voltage variability in 3D geometries.[68] This RMG approach, critical for sub-10 nm nodes, avoids thermal budget issues from early high-k integration and supports gate lengths down to 20 nm.[69] Key tools enabling these formations include EUV lithography for patterning fins or stack templates with critical dimensions below 7 nm, offering resolutions unattainable by deep ultraviolet (DUV) alone, and ALD for precise, conformal deposition of dielectrics and metals with angstrom-level control. Dry etching tools, such as inductively coupled plasma (ICP) reactors, provide anisotropic profiles essential for high-aspect-ratio structures.[63] Process flows for double-gate MOSFETs and GAA FETs diverge after initial substrate preparation but share RMG integration. In double-gate flows, typically on SOI, fins are patterned and etched similarly to FinFETs, followed by gate oxidation or deposition on top and bottom surfaces, with source/drain formation via implantation or epitaxy.[70] GAA flows extend this by adding epitaxial superlattice growth post-fin etch, inner spacer insertion, and multi-step selective etches for channel release, culminating in wider gate wrapping but requiring more complex lithography for stack alignment.[71] These differences allow GAA to achieve superior short-channel control at scaled nodes while inheriting FinFET-compatible early steps.[64]Material and process innovations

The integration of high-k dielectrics such as HfO₂ and ZrO₂ into multigate devices has significantly reduced gate leakage currents while maintaining equivalent oxide thickness (EOT) below 0.5 nm, enabling better electrostatic control in FinFETs and gate-all-around (GAA) structures.[72][73] These materials replace traditional SiO₂, mitigating quantum tunneling effects in scaled channels and improving subthreshold swing in double-gate FinFETs.[74] Channel materials in multigate devices have evolved from bulk silicon to silicon-on-insulator (SOI) substrates for reduced parasitic capacitance, followed by strained SiGe nanowires to enhance hole mobility in p-type channels.[75] In 2023 prototypes, two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs) like MoS₂, WS₂, and WSe₂ have been incorporated as channel materials in wafer-scale transistors, with mobilities around 7–30 cm²/V·s for low-power applications.[76] Contact innovations, including raised source/drain regions formed via epitaxial growth of SiGe or SiC followed by nickel silicide formation, have lowered specific contact resistivity to around 10⁻⁹ Ω·cm² in advanced FinFETs, minimizing series resistance.[77] Recent fabrication processes leverage bottom-up vapor-liquid-solid (VLS) growth for precise nanowire alignment in multigate structures, achieving diameters as small as 10 nm with uniformity over large areas.[78] Complementary FET (CFET) designs incorporate 3D stacking of n- and p-channel nanowires, reducing footprint while maintaining thermal budgets below 700°C.[79] In 2025, hybrid III-V materials like GaN in GAA configurations have advanced RF and high-frequency applications.[80] EUV-assisted patterning has enabled sub-20 nm pitch resolution for these stacked architectures, supporting single-exposure fabrication of complex multigate layouts. As of 2025, high-NA EUV lithography has enabled sub-20 nm pitch resolutions for stacked GAA architectures.[81] Material choices, particularly high-k dielectrics and TMDC channels, have improved fabrication yields by 25–40% through reduced defect densities and enhanced interface quality, as evidenced by hysteresis reductions below 50 mV in 2D-based prototypes.[82][83]Integration and challenges

Circuit integration

In circuit integration, multigate devices such as FinFETs and gate-all-around (GAA) FETs require careful layout considerations to optimize performance and area efficiency. Fin pitch scaling enables higher drive current per unit footprint by allowing denser fin placement, though it introduces trade-offs like increased fringing capacitance between the gate and contacts.[84] To achieve desired drive strength, multiple fins are connected in parallel within a transistor, providing quantized width increments that enhance current capability while maintaining layout regularity.[85] Interconnect integration poses significant challenges due to the dense three-dimensional structures of multigate devices, which complicate local routing and increase parasitic effects. As cell sizes scale, the number of connection pins remains high, demanding innovative local interconnect layers to manage signal integrity and minimize resistance in the back-end-of-line (BEOL) stack.[86] These 3D architectures exacerbate routing congestion, necessitating advanced design rules for via placement and metal layer stacking to avoid delays from elevated capacitance and inductance.[86] The adoption of multigate devices has driven redesigns in SRAM and logic cells, particularly for nodes at 7 nm and beyond, enabling reduced cell heights through tighter fin or nanosheet pitches. In FinFET-based designs at 7 nm, standard cell heights are optimized to around 240-270 nm, facilitating up to 30% area savings compared to planar equivalents by aligning rows with consistent fin spacing.[87] For GAA FETs, further height reductions to approximately 120 nm at sub-3 nm nodes support buried power rails, enhancing density while preserving track utilization in place-and-route flows.[88] Power delivery in multigate circuits benefits from dynamic voltage and frequency scaling (DVFS) compatibility, allowing workload-adaptive voltage adjustments to balance performance and consumption without compromising the devices' superior electrostatic control.[89] Additionally, multi-threshold voltage (multi-Vt) options are implemented using independent gates in FinFETs, where separate front and back gate biases tune Vt dynamically, reducing leakage by up to 50% in logic paths while supporting granular power optimization.[90] Practical examples illustrate these integration strategies. TSMC's 5 nm FinFET process includes certified standard cell libraries with multi-Vt variants, enabling high-density designs for mobile and HPC applications through optimized fin parallelism and interconnect schemes.[91] Samsung's 3 nm GAA standard cells, introduced in production from 2022, leverage nanosheet stacking for flexible SRAM layouts, achieving 16% area reduction over equivalent 5 nm FinFET cells via enhanced channel control and reduced cell heights.[27][54] These advancements yield substantial density improvements, with TSMC's 5 nm FinFET nodes reaching approximately 171 million transistors per mm² through scaled layouts and efficient routing.[92] Samsung's initial 3 nm GAA process (3GAE) achieves approximately 150 million transistors per mm², representing an 18% density gain over its 5 nm baseline, driven by GAA's superior scaling in logic and memory cells.[93][94]Scalability and reliability issues

In FinFETs, edge effects at the fin tips introduce variability in fin height and width, leading to threshold voltage (Vt) mismatch across devices due to uneven gate control and increased scattering. This variability exacerbates device-to-device inconsistencies, particularly in high-density circuits where precise Vt matching is essential for performance uniformity.[95][96] Transitioning to gate-all-around (GAA) FETs, nanosheet structures face significant fabrication challenges during the release process, where selective etching of sacrificial layers can induce bending in the suspended nanosheets due to residual stress imbalances. This bending distorts channel dimensions, degrading electrostatic control and contributing to performance fluctuations. Additionally, inner spacer defects arise from incomplete etching or void formation at the source/drain interfaces, which compromise isolation and increase parasitic capacitances, thereby hindering scalability.[97][98][99] Reliability in multigate devices is further compromised by bias temperature instability (BTI), which causes threshold voltage shifts under prolonged bias and elevated temperatures, particularly in high-k dielectric stacks where trap generation at the interface accelerates degradation. Hot carrier injection (HCI) exacerbates this by injecting high-energy carriers into the gate dielectric, leading to interface state creation and reduced drive current over time, with effects more pronounced in scaled high-k/metal gate configurations. These mechanisms limit long-term operational stability in dense multigate arrays.[100][101][102] In stacked complementary FETs (CFETs), integration issues manifest as severe self-heating due to confined thermal paths in vertically stacked n- and p-channel structures, resulting in localized temperature rises that amplify leakage and aging rates. Parasitic coupling between stacked gates and channels introduces unintended capacitance, increasing power consumption and signal crosstalk in high-density layouts. These thermal and electrical interactions pose barriers to further vertical scaling.[103][104][105] As multigate devices approach sub-2 nm nodes in 2024-2025, quantum tunneling emerges as a critical hurdle, enabling band-to-band leakage that erodes subthreshold swing and off-state current control in GAA structures. As of late 2025, TSMC's N2 and Samsung's SF2 2 nm processes have entered mass production, though challenges like yield optimization and quantum effects persist.[5] In devices incorporating 2D materials like transition metal dichalcogenides, interface traps at the channel-dielectric boundary trap charge carriers, causing hysteresis, mobility degradation, and instability under bias. These quantum and interfacial effects challenge the feasibility of continued aggressive scaling.[79][106][16] To address these scalability and reliability hurdles, strain engineering applies tensile or compressive stress to channels via epitaxial stressors or process-induced relaxation, enhancing carrier mobility and mitigating Vt variability while reducing defect densities in multigate architectures. Redundancy designs, such as triple modular redundancy in critical paths or error-correcting layouts in memory cells, provide fault tolerance against variability and aging-induced failures, ensuring robust operation in advanced multigate systems.[107][108][109]Modeling and applications

Compact modeling

Compact modeling of multigate devices involves developing mathematical frameworks that accurately capture their electrical characteristics for efficient circuit simulation in tools like SPICE, enabling designers to predict device behavior without full-scale numerical simulations. These models must account for the unique geometry of multigate structures, such as multiple gate interfaces and three-dimensional charge distributions, while maintaining computational efficiency for large-scale integrated circuits. Surface-potential-based approaches are prevalent, as they provide a physically grounded description of carrier transport from subthreshold to strong inversion regimes.[110] The BSIM-MG (Berkeley Short-channel IGFET Model for Multi-Gate) and its successor BSIM-CMG (Common Multi-Gate) are industry-standard compact models adapted for multigate MOSFETs, including double-gate, tri-gate, and gate-all-around (GAA) configurations fabricated on SOI or bulk substrates. These models incorporate multi-gate capacitance formulations that treat the effective channel width as a function of fin height and number of gates, enhancing accuracy for short-channel effects like drain-induced barrier lowering. Mobility models in BSIM-CMG account for surface scattering and volume inversion in thin fins, using empirical parameters calibrated to measured data to predict degradation due to interface traps. Similarly, the PSP (Princeton Surface Potential) model has been extended for symmetric FinFETs with thin, undoped bodies, featuring analytical expressions for charge density and current that scale with fin dimensions, ensuring continuity across operating regions. For GAA FETs, surface potential-based approaches solve the three-dimensional Poisson equation to model the electrostatics around the cylindrical or nanosheet channel, capturing radial potential variations that planar models overlook. The Poisson equation in cylindrical coordinates is discretized analytically, yielding the surface potential as a function of gate voltage, channel radius, and doping, which serves as the core for deriving currents and capacitances. This method enables accurate prediction of volume inversion in ultra-narrow channels, where carriers distribute uniformly across the cross-section.[111] Key equations in these models include the threshold voltage for FinFETs, which varies with fin aspect ratio (height-to-width) due to corner effects and depletion width variations. The subthreshold current is modeled exponentially as , incorporating effective width scaled by the number of fins and gates, with mobility adjusted for multi-surface scattering. These formulations ensure smooth transitions to above-threshold operation.[112] Parameter extraction for these models typically bridges technology computer-aided design (TCAD) simulations with measured silicon data, optimizing parameters like threshold voltage and mobility through global fitting algorithms that minimize errors in I-V and C-V curves across multiple device geometries. Techniques such as derivative-free optimization or Bayesian inference are employed to handle the high dimensionality of multigate parameters, achieving root-mean-square errors below 2% for FinFETs down to 10 nm nodes. TCAD provides initial estimates by solving full 3D drift-diffusion equations, refined against fabricated device measurements to capture process variations. Limitations arise in ultra-thin channels below 5 nm, where quantum confinement effects—such as sub-band energy shifts—increase effective bandgap and threshold voltage by 50-200 mV, necessitating ballistic transport models that replace diffusive assumptions with Landauer formalism to account for non-local scattering. These quantum corrections, often implemented as density-gradient add-ons to Poisson solvers, are essential for GAA devices but increase model complexity, potentially slowing simulations by 10-20 times.[113][114]Industry adoption and future trends

The adoption of multigate devices began with Intel's introduction of tri-gate transistors in its 22 nm process node in 2011, marking the first commercial deployment of non-planar FinFET-like structures for improved performance and power efficiency in logic chips.[24] This was followed by widespread FinFET adoption at the 7 nm node, with TSMC initiating volume production in 2018 to enable high-density, low-power applications in mobile processors.[43] Samsung advanced to gate-all-around (GAA) architecture with its 3 nm process in 2022, achieving 23% higher performance and 45% lower power compared to prior 5 nm FinFET nodes through multi-bridge-channel FET (MBCFET) technology.[27] Intel progressed with RibbonFET, a GAA variant, in its 18A node (equivalent to ~1.8 nm class), entering production in 2025 for products such as Panther Lake processors.[115] Key market drivers for multigate adoption include the demands of mobile system-on-chips (SoCs), high-performance computing (HPC), and AI accelerators, where these devices deliver superior electrostatic control for reduced leakage and higher drive currents at low voltages.[116] In mobile SoCs, GAA structures enable compact designs with extended battery life, while in HPC and AI, they support dense integration for energy-efficient parallel processing in data centers and edge devices.[117] As of November 2025, GAA transistors have entered production for 2 nm nodes across major foundries, with TSMC's N2 using nanosheet GAAFET beginning volume production in late 2025, Samsung's SF2 employing second-generation MBCFET achieving yields sufficient for commercial output, and Intel's 18A utilizing RibbonFET.[5][118][119][120] The global FinFET and GAA market, encompassing multigate technologies, is projected to exceed USD 130 billion by 2030, driven by a compound annual growth rate of over 23% from applications in consumer electronics and computing.[121] Future trends in multigate devices emphasize complementary FET (CFET) stacking to achieve effective 1 nm scaling through vertical integration of n- and p-type transistors, potentially reducing footprint by 30-50% while maintaining performance.[122] Hybrid approaches incorporating 2D materials like transition metal dichalcogenides with III-V compounds in GAA channels are emerging to enhance mobility and electrostatics beyond silicon limits for sub-1 nm equivalents.[16] Additionally, designs are evolving to support quantum-resistant cryptography in secure HPC and AI systems, integrating hardened logic without compromising multigate efficiency. Representative case studies highlight practical impacts: Apple's A-series chips, such as the A12 Bionic in the 2018 iPhone XS using TSMC's 7 nm FinFET, achieved 67% higher transistor density over 10 nm for enhanced graphics and neural processing.[123] Similarly, Samsung's Exynos processors leverage MBCFET in 3 nm GAA for models like the Exynos 2500 released in 2025, offering adjustable channel widths for optimized SRAM in mobile AI tasks.[54][124]References

- https://en.wikichip.org/wiki/3_nm_lithography_process

- https://en.wikichip.org/wiki/5_nm_lithography_process