Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

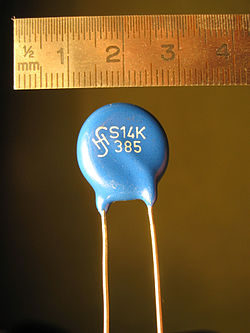

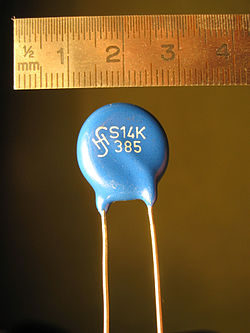

Varistor

View on Wikipedia

A varistor (a.k.a. voltage-dependent resistor (VDR)) is a surge protecting electronic component with an electrical resistance that varies with the applied voltage.[2] It has a nonlinear, non-ohmic current–voltage characteristic that is similar to that of a diode. Unlike a diode however, it has the same characteristic for both directions of traversing current. Traditionally, varistors were constructed by connecting two rectifiers, such as the copper-oxide or germanium-oxide rectifier in antiparallel configuration. At low voltage the varistor has a high electrical resistance which decreases as the voltage is raised. Modern varistors are primarily based on sintered ceramic metal-oxide materials which exhibit directional behavior only on a microscopic scale. This type is commonly known as the metal-oxide varistor (MOV).

Varistors are used as control or compensation elements in circuits either to provide optimal operating conditions or to protect against excessive transient voltages. When used as protection devices, they shunt the current created by the excessive voltage away from sensitive components when triggered.

The name varistor is a portmanteau of varying resistor. The term is only used for non-ohmic varying resistors. Variable resistors, such as the potentiometer and the rheostat, have ohmic characteristics.

History

[edit]The development of the varistor, in form of a new type of rectifier based on a cuprous oxide (Cu2O) layer on copper, originated in the work by L.O. Grondahl and P.H. Geiger in 1927.[3]

The copper-oxide varistor exhibited a varying resistance in dependence on the polarity and magnitude of applied voltage.[4] It was constructed from a small copper disk, on one side of which, a layer of cuprous oxide was formed. This arrangement provides low resistance to current flowing from the semiconducting oxide to the copper side, but a high resistance to current in the opposite direction, with the instantaneous resistance varying continuously with the voltage applied.

In the 1930s, small multiple-varistor assemblies of a maximum dimension of less than one inch and apparently indefinite useful lifetime found application in replacing bulky electron tube circuits as modulators and demodulators in carrier current systems for telephonic transmission.[4]

Other applications for varistors in the telephone plant included protection of circuits from voltage spikes and noise, as well as click suppression on receiver (ear-piece) elements to protect users' ears from popping noises when switching circuits. These varistors were constructed by layering an even number of rectifier disks in a stack and connecting the terminal ends and the center in an anti-parallel configuration, as shown in the photo of a Western Electric Type 3B varistor of June 1952 (below).

-

Western Electric 3B varistor made in 1952 for use as click suppressor in telephone sets

-

Circuit of the traditional construction of varistors used as click suppressors in telephony[5]

-

Western Electric Type 44A varistor for click suppression, mounted on a U1 telephone receiver element manufactured in 1958.

The Western Electric type 500 telephone set of 1949 introduced a dynamic loop equalization circuit using varistors that shunted relatively high levels of loop current on short central office loops to adjust the transmission and receiving signal levels automatically. On long loops, the varistors maintained a relatively high resistance and did not alter the signals significantly.[7]

Another type of varistor was made from silicon carbide (SiC) by R. O. Grisdale in the early 1930s. It was used to guard telephone lines from lightning.[8]

In the early 1970s, Japanese researchers recognized the semiconducting electronic properties of zinc oxide (ZnO) as being useful as a new varistor type in a ceramic sintering process, which exhibited a voltage-current function similar to that of a pair of back-to-back Zener diodes.[9][10] This type of device became the preferred method for protecting circuits from power surges and other destructive electric disturbances, and became known generally as the metal-oxide varistor (MOV). The randomness of orientation of ZnO grains in the bulk of this material provided the same voltage-current characteristics for both directions of current flow.

Composition, properties, and operation of the metal-oxide varistor

[edit]

The most common modern type of varistor is the metal-oxide varistor (MOV). This type contains a ceramic mass of zinc oxide (ZnO) grains, in a matrix of other metal oxides, such as small amounts of bismuth, cobalt, manganese oxides, sandwiched between two metal plates, which constitute the electrodes of the device. The boundary between each grain and a neighbor forms a diode junction, which allows current to flow in only one direction. The accumulation of randomly oriented grains is electrically equivalent to a network of back-to-back diode pairs, each pair in parallel with many other pairs.[11]

When a small voltage is applied across the electrodes, only a tiny current flows, caused by reverse leakage through the diode junctions. When a large voltage is applied, the diode junction breaks down due to a combination of thermionic emission and electron tunneling, resulting in a large current flow. The result of this behavior is a nonlinear current-voltage characteristic, in which the MOV has a high resistance at low voltages and a low resistance at high voltages.

Electrical characteristics

[edit]A varistor remains non-conductive as a shunt-mode device during normal operation when the voltage across it remains well below its "clamping voltage", thus varistors are typically used for suppressing line voltage surges. Varistors can fail for either of two reasons.

A catastrophic failure occurs from not successfully limiting a very large surge from an event like a lightning strike, where the energy involved is many orders of magnitude greater than the varistor can handle. Follow-through current resulting from a strike may melt, burn, or even vaporize the varistor. This thermal runaway is due to a lack of conformity in individual grain-boundary junctions, which leads to the failure of dominant current paths under thermal stress when the energy in a transient pulse (normally measured in joules) is too high (i.e. significantly exceeds the manufacture's "Absolute Maximum Ratings"). The probability of catastrophic failure can be reduced by increasing the rating, or using specially selected MOVs in parallel.[12]

Cumulative degradation occurs as more surges happen. For historical reasons, many MOVs have been incorrectly specified allowing frequent swells to also degrade capacity.[13] In this condition the varistor is not visibly damaged and outwardly appears functional (no catastrophic failure), but it no longer offers protection.[14] Eventually, it proceeds into a shorted circuit condition as the energy discharges create a conductive channel through the oxides.

The main parameter affecting varistor life expectancy is its energy (Joule) rating. Increasing the energy rating raises the number of (defined maximum size) transient pulses that it can accommodate exponentially as well as the cumulative sum of energy from clamping lesser pulses. As these pulses occur, the "clamping voltage" it provides during each event decreases, and a varistor is typically deemed to be functionally degraded when its "clamping voltage" has changed by 10%. Manufacturer's life-expectancy charts relate current, severity, and number of transients to make failure predictions based on the total energy dissipated over the life of the part.

In consumer electronics, particularly surge protectors, the MOV varistor size employed is small enough that eventually failure is expected.[15] Other applications, such as power transmission, use VDRs of different construction in multiple configurations engineered for long life span.[16]

Voltage rating

[edit]

MOVs are specified according to the voltage range that they can tolerate without damage. Other important parameters are the varistor's energy rating in joules, operating voltage, response time, maximum current, and breakdown (clamping) voltage. Energy rating is often defined using standardized transients such as 8/20 microseconds or 10/1000 microseconds, where 8 microseconds is the transient's front time and 20 microseconds is the time to half value.

Capacitance

[edit]Typical capacitance for consumer-sized (7–20 mm diameter) varistors are in the range of 100–2,500 pF. Smaller, lower-capacitance varistors are available with capacitance of ~1 pF for microelectronic protection, such as in cellular phones. These low-capacitance varistors are, however, unable to withstand large surge currents simply due to their compact PCB-mount size.

Response time

[edit]The response time of the MOV is not standardized. The sub-nanosecond MOV response claim is based on the material's intrinsic response time, but will be slowed down by other factors such as the inductance of component leads and the mounting method.[17] That response time is also qualified as insignificant when compared to a transient having an 8 µs rise-time, thereby allowing ample time for the device to slowly turn-on. When subjected to a very fast, <1 ns rise-time transient, response times for the MOV are in the 40–60 ns range.[18]

Applications

[edit]

A typical surge protector power strip is built using MOVs. Low-cost versions may use only one varistor, from the hot (live, active) to the neutral conductor. A better protector contains at least three varistors; one across each of the three pairs of conductors. [citation needed] Some standards mandate a triple varistor scheme so that catastrophic MOV failure does not create a fire hazard.[19][20]

Hazards

[edit]While a MOV is designed to conduct significant power for very short durations (about 8 to 20 microseconds), such as caused by lightning strikes, it typically does not have the capacity to conduct sustained energy. Under normal utility voltage conditions, this is not a problem. However, certain types of faults on the utility power grid can result in sustained over-voltage conditions. Examples include a loss of a neutral conductor or shorted lines on the high voltage system. Application of sustained over-voltage to a MOV can cause high dissipation, potentially resulting in the MOV device catching fire. The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) has documented many cases of catastrophic fires that have been caused by MOV devices in surge suppressors, and has issued bulletins on the issue.[21]

A series connected thermal fuse is one solution to catastrophic MOV failure. Varistors with internal thermal protection are also available.

There are several issues to be noted regarding behavior of transient voltage surge suppressors (TVSS) incorporating MOVs under over-voltage conditions. Depending on the level of conducted current, dissipated heat may be insufficient to cause failure, but may degrade the MOV device and reduce its life expectancy. If excessive current is conducted by a MOV, it may fail catastrophically to an open circuit condition, keeping the load connected but now without any surge protection. A user may have no indication that the surge suppressor has failed.

Under the right conditions of over-voltage and line impedance, it may be possible to cause the MOV to burst into flames,[22] the root cause of many fires[23] which is the main reason for NFPA's concern resulting in UL1449 in 1986 and subsequent revisions in 1998 and 2009. Properly designed TVSS devices must not fail catastrophically, instead resulting in the opening of a thermal fuse or something equivalent that only disconnects MOV devices.

Limitations

[edit]A MOV inside a transient voltage surge suppressor (TVSS) does not provide complete protection for electrical equipment. In particular, it provides no protection from sustained over-voltages that may result in damage to that equipment as well as to the protector device. Other sustained and harmful over-voltages may be lower and therefore ignored by a MOV device.

A varistor provides no equipment protection from inrush current surges (during equipment startup), from overcurrent (created by a short circuit), or from voltage sags (brownouts); it neither senses nor affects such events. Susceptibility of electronic equipment to these other electric power disturbances is defined by other aspects of the system design, either inside the equipment itself or externally by means such as a UPS, a voltage regulator or a surge protector with built-in overvoltage protection (which typically consists of a voltage-sensing circuit and a relay for disconnecting the AC input when the voltage reaches a danger threshold).

Comparison to other transient suppressors

[edit]Another method for suppressing voltage spikes is the transient-voltage-suppression diode (TVS). Although diodes do not have as much capacity to conduct large surges as MOVs, diodes are not degraded by smaller surges and can be implemented with a lower "clamping voltage". MOVs degrade from repeated exposure to surges[24] and generally have a higher "clamping voltage" so that leakage does not degrade the MOV. Both types are available over a wide range of voltages. MOVs tend to be more suitable for higher voltages, because they can conduct the higher associated energies at less cost.[25]

Another type of transient suppressor is the gas-tube suppressor. This is a type of spark gap that may use air or an inert gas mixture and often, a small amount of radioactive material such as Ni-63, to provide a more consistent breakdown voltage and reduce response time. Unfortunately, these devices may have higher breakdown voltages and longer response times than varistors. However, they can handle significantly higher fault currents and withstand multiple high-voltage hits (for example, from lightning) without significant degradation.

Multi-layer varistor

[edit]Multi-layer varistor (MLV) devices provide electrostatic discharge protection to electronic circuits from low to medium energy transients in sensitive equipment operating at 0–120 volts dc. They have peak current ratings from about 20 to 500 amperes, and peak energy ratings from 0.05 to 2.5 joules.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Resettable fuse, a current-sensitive device

- Trisil

References

[edit]- ^ "Standards for Resistor Symbols". EePower. EETech Media. Retrieved September 13, 2021.

- ^ Bell Laboratories (1983). S. Millman (ed.). A History of Engineering and Science in the Bell System, Physical Science (1925–1980) (PDF). AT&T Bell Laboratories. p. 413. ISBN 0-932764-03-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-12-26. Retrieved 2015-03-17.

- ^ Grondahl, L. O.; Geiger, P. H. (February 1927). "A new electronic rectifier". Journal of the A.I.E.E. 46 (3): 357–366. doi:10.1109/JAIEE.1927.6534186. S2CID 51645117.

- ^ a b American Telephone & Telegraph; C.F. Myers, L.S.c Crosboy (eds.); Principles of Electricity applied to Telephone and Telegraph Work, New York City (November 1938), p.58, 257

- ^ Automatic Electric Co., Bulletin 519, Type 47 Monophone (Chicago, 1953)

- ^ American National Standard,Graphic Symbols for Electrical and Electronics Diagrams, ANSI Y32.2-1975 p.27

- ^ AT&T Bell Laboratories, Technical Staff, R.F. Rey (ed.) Engineering and Operations in the Bell System, 2nd edition, Murray Hill (1983), p467

- ^ R.O. Grisdale, Silicon Carbide Varistors, Bell Laboratories Record 19 (October 1940), pp.46–51.

- ^ M. Matsuoka, Jpn. J. Appl. Phys., 10, 736 (1971).

- ^ Levinson L, Philip H.R., Zinc oxide Varistors—A Review, American Ceramic Society Bulletin 65(4), 639 (1986).

- ^ Introduction to Metal Oxide Varistors, www.powerguru.org

- ^ "The ABCs of MOVs" (PDF). Littelfuse, Inc. 1999. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-05-14. Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- ^ "Lower not better" (PDF). www.nist.gov. Retrieved 2021-12-11.

- ^ "MOV Failure Mode Identification" (PDF). University of South Florida. n.d. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-02-25. Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- ^ "Metal Oxide Varistor (MOV) – Electronic Circuits and Diagram-Electronics Projects and Design". 23 March 2011.

- ^ "GE TRANQUELLTM Surge Arresters" (PDF). GE Grid Solutions. 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-11-23. Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- ^ D. Månsson, R. Thottappillil, "Comments on ‘Linear and nonlinear filters suppressing UWB pulses’", IEEE Transactions on Electromagnetic Compatibility, vol. 47, no. 3, pp. 671–672, Aug. 2005.

- ^ "Detailed Comparison of Surge Suppression Devices". Archived from the original on 2010-11-05.

- ^ "UL1449 3rd Edition Overview – Surge Protection – Littelfuse". Archived from the original on 2018-11-01. Retrieved 2017-01-12.

- ^ USAGov. "USA.Gov Subscription Page" (PDF). publications.usa.gov. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ^ "Data Assessment for Electrical Surge Protection Devices". Fire Protection Research Foundation. 2014. Archived from the original on 2021-08-18. Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- ^ "Metal Oxide Varistors | Circuit Breakers Blog – Expert Safety and Usage Information". Circuit Breakers Blog. Retrieved 2013-01-14.

- ^ Pharr, Jim. "Surge Suppressor Fires". ESD Journal. Archived from the original on 2007-03-16. Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- ^ Winn L. Rosch (2003). Winn L. Rosch Hardware Bible (6th ed.). Que Publishing. p. 1052. ISBN 978-0-7897-2859-3.

- ^ Brown, Kenneth (March 2004). "Metal Oxide Varistor Degradation". IAEI Magazine. Archived from the original on 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2011-03-30.

External links

[edit]- The ABCs of MOVs Archived 2011-01-05 at the Wayback Machine — application notes from Littelfuse company

- Varistor testing Archived 2011-01-05 at the Wayback Machine from Littelfuse company

![Circuit of the traditional construction of varistors used as click suppressors in telephony[5]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/43/Varistor_circuit_historical_construction.png/120px-Varistor_circuit_historical_construction.png)

![Traditional varistor schematic symbol,[6] used today for the diac. It expresses the diode-like behavior in both directions of current flow.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/81/Diac.svg/97px-Diac.svg.png)