Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Caribbean Community

View on Wikipedia

The Caribbean Community (abbreviated as CARICOM or CC) is an intergovernmental organisation that is a political and economic union of 15 member states (14 nation-states and one dependency) and five associated members throughout the Americas, the Caribbean and Atlantic Ocean.[1] It has the primary objective to promote economic integration and cooperation among its members, ensure that the benefits of integration are equitably shared, and coordinate foreign policy. The organisation was established in 1973,[11] by its four founding members signing the Treaty of Chaguaramas.

Key Information

The secretariat headquarters is in Georgetown, Guyana. CARICOM has been granted the official United Nations General Assembly observer status.[12]

History

[edit]CARICOM, originally The Caribbean Community and Common Market, was established by the Treaty of Chaguaramas which took effect on 1 August 1973.[13] Founding states were Barbados, Jamaica, Guyana and Trinidad and Tobago.

The Caribbean Community superseded the 1965–1972 Caribbean Free Trade Association organised to provide a continued economic linkage between the English-speaking countries of the Caribbean after the dissolution of the West Indies Federation, which lasted from 3 January 1958 to 31 May 1962.

A revised Treaty of Chaguaramas established The Caribbean Community including the CARICOM Single Market and Economy, security, foreign exchange and was signed by the CARICOM Heads of Government of the Caribbean Community on 5 July 2001 at their Twenty-Second Meeting of the Conference in Nassau, The Bahamas.[14] The revised treaty cleared the way to transform the idea of a common market CARICOM into the Caribbean (CARICOM) Single Market and Economy.

Haiti's membership in CARICOM remained effectively suspended from 29 February 2004 through early June 2006 following the 2004 Haitian coup d'état and the removal of Jean-Bertrand Aristide from the presidency.[15][16] CARICOM announced that no democratically elected government in CARICOM should have its leader deposed. The fourteen other heads of government sought to have Aristide fly from Africa to Jamaica and share his account of events with them, which infuriated the interim Haitian prime minister, Gérard Latortue, who announced he would take steps to take Haiti out of CARICOM.[17] CARICOM thus voted on suspending the participation of Haitian officials from the councils of CARICOM.[18][19] Following the presidential election of René Préval, Haitian officials were readmitted and Préval himself gave the opening address at the CARICOM Council of Ministers meeting in July.[20][21]

Since 2013 the CARICOM-bloc and with the Dominican Republic have been tied to the European Union via an Economic Partnership Agreements signed in 2008 known as CARIFORUM.[22] The treaty grants all members of the European Union and CARIFORUM equal rights in terms of trade and investment. Under Article 234 of the agreement, the European Court of Justice handles dispute resolution between CARIFORUM and European Union states.[23]

On 1 October 2025, four Caricom members—Barbados, Belize, Dominica, and St. Vincent and the Grenadines—implemented full freedom of movement, going beyond the freedom of movement only for skilled workers that other Caricom members have implemented.[24]

Agenda and goals

[edit]CARICOM was established by the English-speaking countries of the Caribbean and currently includes all the independent Anglophone island countries plus Belize, Guyana, Montserrat and Suriname, as well as all other British Caribbean territories and Bermuda as associate members. English was its sole working language into the 1990s. The organisation became multilingual with the addition of Dutch and Sranan Tongo-speaking Suriname in 1995 and the French and Haitian Creole-speaking Haiti in 2002. Furthermore, it added Spanish as the fourth official language in 2003. In July 2012, CARICOM announced they considered making French and Dutch official languages.[25] In 2001, the Conference of Heads of Governments signed a revised Treaty of Chaguaramas that cleared the way to transform the idea of a common market CARICOM into the CARICOM Single Market and Economy.[26] Part of the revised treaty establishes and implements the Caribbean Court of Justice. Its primary activities involve:

- Coordinating economic policies and development planning.

- Devising and instituting special projects for the less-developed countries within its jurisdiction.

- Operating as a regional single market for many of its members (Caricom Single Market).

- Handling regional trade disputes.

Organisational structure

[edit]The following is the overall structure of Caribbean Community (CARICOM).[27]

Administration and staff

[edit]| Institution | Abbreviation | Location | Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| Secretariat of the Caribbean Community | CCS | Georgetown | Guyana |

| Caricom heads of government | PCC | variable | |

| Conference of Heads of Governments | HGC | variable | |

| Assembly of Caribbean Community Parliamentarians | ACCP | variable | |

| Caribbean Community Administrative Tribunal | CCAT | Port of Spain | Trinidad and Tobago |

Chairmanship

[edit]The post of Chairman (Head of CARICOM) is held in rotation by the regional Heads of Government of CARICOM's 15 member states. These include Antigua and Barbuda, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Haiti, Montserrat, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, The Bahamas, Barbados, Guyana, Jamaica, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago.

Heads of government

[edit]CARICOM contains a quasi-Cabinet of the individual Heads of Government. These heads are given specialised portfolios of responsibility for regional development and integration.[28]

Secretariat

[edit]The Secretariat of the Caribbean Community is the Chief Administrative Organ for CARICOM. The Secretary-General of the Caribbean Community is the chief executive and handles foreign and community relations. Five years is the term of office of the Secretary-General, which may be renewed. The Deputy Secretary-General of the Caribbean Community handles human and Social Development. The General Counsel of the Caribbean Community handles trade and economic integration.

The goal statement of the CARICOM Secretariat is: "To contribute, in support of Member States, to the improvement of the quality of life of the People of the Community and the development of an innovative and productive society in partnership with institutions and groups working towards attaining a people-centred, sustainable and internationally competitive Community."[29]

Organs and bodies

[edit]| Organ | Description |

|---|---|

| CARICOM Heads of Government | Consisting of the various heads of Government from each member state |

| Standing Committee of Ministers | Ministerial responsibilities for specific areas, for example the Standing Committee of Ministers responsible for Health will consist of Ministers of Health from each member state |

Community Council

[edit]The Community Council comprises ministers responsible for community affairs and any other Minister designated by the member states at their discretion. It is one of the community's principal organs; the other is the Conference of the Heads of Government. Four other organs and three bodies support it.

| Secondary organ | Abbreviation |

|---|---|

| Council for Finance and Planning | COFAP |

| Council for Foreign and Community Relations | COFCOR |

| Council for Human and Social Development | COHSOD |

| Council for Trade and Economic Development | COTED |

| Body | Description |

|---|---|

| Legal Affairs Committee[30] | provides legal advice |

| Budget Committee | examines the draft budget and work programme of the Secretariat and submits recommendations to the Community Council. |

| Committee of the Central Bank Governors | provides recommendations to the COFAP on monetary and financial matters. |

Institutions

[edit]The following institutions are founded by or affiliated to the Caricom:[31]

Caricom Institutions

[edit]Functional cooperation

[edit]| Institution | Abbreviation | Location | Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caribbean Tourism Organization | CTO | Saint Michael | Barbados |

| Caribbean Council of Legal Education | CLE | several | |

| Caribbean Export Development Agency | Caribbean Export | Saint Michael | Barbados |

| Caribbean Regional Information and Translation Institute | CRITI | Paramaribo | Suriname |

Associate

[edit]| Institution | Abbreviation | Location | Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caribbean Congress of Labour | CCL | Saint Michael | Barbados |

| Caricom Private Sector Organization | CPSO | Saint Michael | Barbados |

| University of the West Indies | UWI | several | |

| University of Guyana | UG | Georgetown | Guyana |

| Caribbean Law Institute | CLI | Saint Michael | Barbados |

| Caribbean Development Bank | CDB | Saint Michael | Barbados |

Cancelled

[edit]The following institutions have been cancelled or merged into other ones:

| Institution | Abbreviation | Location | Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regional Educational Programme for Animal Health Assistants | REPAHA | New Amsterdam | Guyana |

| Caribbean Food Corporation | CFC | Saint Augustine | Trinidad and Tobago |

| Caribbean Environmental Health Institute | CEHI | Castries | Saint Lucia |

| The Caribbean Epidemiology Centre | CAREC | Port of Spain | Trinidad and Tobago |

| Caribbean Food and Nutrition Institute | CFNI | Kingston | Jamaica |

| Caribbean Health Research Council | CHRC | Saint Augustine | Trinidad and Tobago |

| Caribbean Regional Drug Testing Laboratory | CRDTL | Georgetown | Guyana |

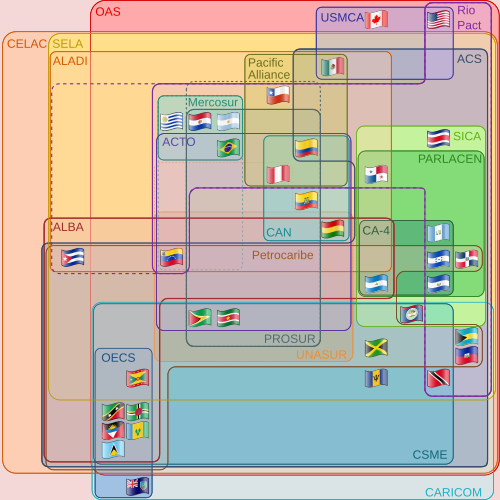

Relationship to other supranational Caribbean organisations

[edit]Parts of this article (those related to Anguilla and other associate CARICOM members) need to be updated. (February 2012) |

Association of Caribbean States

[edit]CARICOM was instrumental in the formation of the Association of Caribbean States (ACS) on 24 July 1994. The original idea for the Association came from a recommendation of the West Indian Commission, established in 1989 by the CARICOM heads of state and government. The Commission advocated both deepening the integration process (through the CARICOM Single Market and Economy) and complementing it through a separate regional organisation encompassing all states in the Caribbean.[33]

CARICOM accepted the commission's recommendations and opened dialogue with other Caribbean states, the Central American states and the Latin American nations of Colombia, Venezuela and Mexico which border the Caribbean, for consultation on the proposals of the West Indian Commission.[33]

At an October 1993 summit, the heads of state and government of CARICOM and the presidents of the then-Group of Three (Colombia, Mexico and Venezuela) formally decided to create an association grouping all states of the Caribbean basin. A work schedule for its formation was adopted. The aim was to create the association in less than a year, an objective which was achieved with the formal creation of the ACS.[33]

Community of Latin American and Caribbean States

[edit]CARICOM was also involved in the formation of the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) on 3 December 2010. The idea for CELAC originated at the Rio Group–Caribbean Community Unity Summit on 23 February 2010 in Mexico. This act caters to the integration of the Americas process, complimenting well-established initiatives of the Organization of American States.[34][35][36][37]

European Union: Economic Partnership Agreements

[edit]Since 2013, the CARICOM-bloc and the Dominican Republic have been tied to the European Union via an Economic Partnership Agreements known as CARIFORUM signed in 2008.[22] The treaty grants all members of the European Union and CARIFORUM equal rights in terms of trade and investment. Within the agreement under Article 234, the European Court of Justice also carries dispute resolution mechanisms between CARIFORUM and the states of the European Union.[23]

OHADAC Project

[edit]In May 2016, Caricom's court of original jurisdiction, the CCJ, signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with the ACP Legal Association based in Guadeloupe recognising and supporting the goals of implementing a harmonised business law framework in the Caribbean through ACP Legal Association's OHADAC Project.[38]

OHADAC is the acronym for the French "Organisation pour l'Harmonisation du Droit des Affaires en les Caraïbes", which translates into English as "Organisation for the Harmonisation of Business Law in the Caribbean". The OHADAC Project takes inspiration from a similar organisation in Africa and aims to enhance economic integration across the entire Caribbean and facilitate increased trade and international investment through unified laws and alternative dispute resolution methods.[38]

Member states

[edit]As of 2024[update] CARICOM has 15 full members, seven associate members and eight observers. The associated members are five British Overseas Territories, one constituent county of the Kingdom of the Netherlands and one French Overseas Territory. It is currently not established what the role of the associate members will be. The observers are states which engage in at least one of CARICOM's technical committees.[39][page needed]

Under Article 4 CARICOM breaks its 15 member states into two groups: Less Developed Countries (LDCs) and More Developed Countries (MDCs).[40]

The countries of CARICOM which are designated as Less Developed Countries (LDCs) are as follows:[40]

- Antigua and Barbuda

- Belize

- Commonwealth of Dominica

- Grenada

- Republic of Haiti

- Montserrat

- Federation of St. Kitts and Nevis

- St Lucia

- St Vincent and the Grenadines

The countries of CARICOM which are designated as More Developed Countries (MDCs) are:[40]

- Commonwealth of The Bahamas

- Barbados

- Co-operative Republic of Guyana

- Jamaica

- Republic of Suriname

- Republic of Trinidad and Tobago

| Status | Name | Join date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full member | 4 July 1974 | ||

| 4 July 1983 | Not a part of the customs union | ||

| 1 August 1973 | One of the four founding members | ||

| 1 May 1974 | |||

| 1 August 1973 | One of the four founding members | ||

| 2 July 2002 | Provisional membership on 4 July 1998 | ||

| 1 August 1973 | One of the four founding members | ||

| 1 May 1974 | British overseas territory | ||

| 26 July 1974 | Joined as Saint Christopher-Nevis-Anguilla | ||

| 1 May 1974 | |||

| 1 May 1974 | |||

| 4 July 1995 | |||

| 1 August 1973 | One of the four founding members | ||

| Associate | 4 July 1999 | British overseas territory | |

| 2 July 2003 | |||

| 2 July 1991 | |||

| 16 May 2002 | |||

| 28 July 2024 | Constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands | ||

| 20 February 2025 | French overseas territory | ||

| 2 July 1991 | British overseas territory | ||

| Observer | Constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands | ||

| Unincorporated territory of the United States | |||

| Constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands | |||

Thousands of Caricom nationals live within other member states of the Community.

An estimated 30,000 Jamaicans legally reside in other CARICOM member states,[41] mainly in The Bahamas (6,200), Antigua & Barbuda (estimated 12,000),[42] Barbados and Trinidad & Tobago).[41] Also, an estimated 150 Jamaicans live and work in Montserrat.[42] A 21 November 2013 estimated put 16,958 Jamaicans residing illegally in Trinidad & Tobago, as according to the records of the Office of the Chief Immigration Officer, their entry certificates would have since expired.[43] By October 2014, the estimated Jamaicans residing illegally in Trinidad and Tobago was 19,000 along with an estimated 7,169 Barbadians and 25,884 Guyanese residing illegally.[44] An estimated 8,000 Trinidadians and Tobagonians live in Jamaica.[45]

Barbados hosts a large diaspora population of Guyanese, of whom (in 2005) 5,032 lived there permanently as citizens, permanent residents, immigrants (with immigrant status) and Caricom skilled nationals; 3,200 were residing in Barbados temporarily under work permits, as students, or with "reside and work" status. A further 2,000–3,000 Guyanese were estimated to be living illegally in Barbados at the time.[46] Migration between Barbados and Guyana has deep roots, going back over 150 years, with the most intense period of Barbadian migration to then-British Guiana occurring between 1863 and 1886, although as late as the 1920s and 1930s Barbadians were still leaving Barbados for British Guiana.[47]

Migration between Guyana and Suriname also goes back a number of years. An estimated 50,000 Guyanese had migrated to Suriname by 1986[48][49] In 1987 an estimated 30–40,000 Guyanese were in Suriname.[50] Many Guyanese left Suriname in the 1970s and 1980s, either voluntarily or by expulsion. Citing a national security concern, over 5,000 were expelled in January 1985 alone.[51] In the instability Suriname experienced following independence, both coups and civil war.[49] In 2013, an estimated 11,530 Guyanese had emigrated to Suriname and 4,662 Surinamese to Guyana.[52]

Relationship with Cuba

[edit]In 2017, the Republic of Cuba and CARICOM signed the "CARICOM-Cuba Trade and Economic Cooperation Agreement"[53] to facilitate closer trade ties.[54] In December 2022, President of Cuba Miguel Díaz-Canel met in Bridgetown, Barbados with the Heads of State and Government of CARICOM. On the occasion of the 8th CARICOM-Cuba Summit to commemorate the 50th Anniversary of establishing diplomatic relations with the independent States of CARICOM and Cuba and the 20th Anniversary of CARICOM-Cuba Day. Cuba also accepted CARICOM's offer to deepen bilateral cooperation and to join robust discussions in the bloc's regional 'Joint Ministerial Taskforce on Food production and Security'.

Dialogue partners / accreditation to CARICOM

[edit]A number of global partners have established diplomatic representation to the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) Secretariat located in Georgetown, Guyana. Nations with non-resident representatives to CARICOM in italics:[55][56]

African Union Non accreditation, but as dialogue partner[57]

African Union Non accreditation, but as dialogue partner[57] Argentina[58]

Argentina[58] Australia[59]

Australia[59] Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Brazil

Brazil Canada[60]

Canada[60] Chile

Chile Colombia

Colombia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba El Salvador

El Salvador European Union

European Union Finland

Finland France

France Germany

Germany Greece

Greece India[61]

India[61] Indonesia

Indonesia Ireland

Ireland Israel[62]

Israel[62] Italy

Italy Japan[63]

Japan[63] Korea

Korea Latvia

Latvia Lithuania

Lithuania Mexico[64][65]

Mexico[64][65] Netherlands

Netherlands New Zealand[66][67]

New Zealand[66][67] Panama

Panama Portugal

Portugal Romania

Romania Singapore[68]

Singapore[68] Slovenia

Slovenia Sweden

Sweden Switzerland

Switzerland Turkey[69]

Turkey[69] United Kingdom

United Kingdom United States of America

United States of America Venezuela

Venezuela

Free-trade agreements

[edit]Statistics

[edit]| Member | Membership | Land area (km2)[71] | Population (2019) | GDP (PPP) Millions USD (2017)[72] | GDP Per Capita (PPP) USD (2017) | Human Development Index (2023)[73] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| associate | 91 | 15,174 | 175.4 | 12,200 | – | |

| full member | 442.6 | 104,084 | 2,390 | 26,300 | 0.851 | |

| full member | 10,010 | 385,340 | 9,339 | 25,100 | 0.820 | |

| full member | 430 | 287,010 | 4,919 | 17,500 | 0.811 | |

| full member | 22,806 | 398,050 | 3,230 | 8,300 | 0.721 | |

| associate | 54 | 63,779 | 5,198 | 85,700 | – | |

| associate | 151 | 32,206 | 500 | 42,300 | – | |

| associate | 264 | 64,420 | 2,507 | 43,800 | – | |

| full member | 751 | 74,679 | 851 | 12,000 | 0.761 | |

| full member | 344 | 108,825 | 1,590 | 14,700 | 0.791 | |

| full member | 214,970 | 786,508 | 6,367 | 8,300 | 0.776 | |

| full member | 27,560 | 11,242,856 | 19,880 | 1,800 | 0.554 | |

| full member | 10,831 | 2,728,864 | 26,200 | 9,200 | 0.720 | |

| full member | 102 | 5,220 | 43.8 | 8,500 | – | |

| full member | 261 | 56,345 | 1,528 | 26,800 | 0.840 | |

| full member | 606 | 180,454 | 2,384 | 13,500 | 0.748 | |

| full member | 389 | 109,803 | 1,281 | 11,600 | 0.798 | |

| full member | 156,000 | 573,085 | 7,928 | 13,900 | 0.722 | |

| full member | 5,128 | 1,359,193 | 42,780 | 31,200 | 0.807 | |

| associate | 948 | 37,910 | 632 | 29,100 | – | |

| Full members | members only | 432,510 | 18,400,316 | 130,711 | 15,247 | 0.751 |

Symbols

[edit]Standard

[edit]The flag of the Caribbean Community was chosen and approved in November 1983 at the Conference of Heads of Government Meeting in Port of Spain, Trinidad. The original design by the firm of WINART Studies in Georgetown, Guyana was substantially modified at the July 1983 Meeting of the Conference of Heads of Government.[74] The flag was first flown on 4 July 1984 in Nassau, The Bahamas at the fifth Meeting of the Conference of Heads of Government.[75]

The flag features a blue background, but the upper part is a light blue representing sky and the lower, a darker blue representing the Caribbean Sea. The yellow circle in the centre represents the sun on which is printed in black the logo of the Caribbean Community, two interlocking Cs. The two Cs are in the form of broken links in a chain, symbolising both unity and a break with the colonial past. The narrow ring of green around the sun represents the vegetation of the region.[74]

Song

[edit]For CARICOM's 40th anniversary, a competition to compose an official song or anthem for CARICOM was launched in April 2013[76] to promote choosing a song that promoted unity and inspired CARICOM identity and pride. A regional panel of judges comprising independent experts in music was nominated by member states and the CARICOM Secretariat. Three rounds of competition condensed 63 entries to a final three, from which judges chose Celebrating CARICOM by Michele Henderson of Dominica[76] in March 2014.[77] Henderson won a US$10,000 prize.[78] Her song was produced by her husband, Roland Delsol Jr., and arranged by Earlson Matthew. It also featured Michael Ferrol on drums and choral input from the St. Alphonsus Choir. It was re-produced for CARICOM by Carl Beaver Henderson of Trinidad and Tobago.[77]

A second-place entry titled My CARICOM came from Jamaican Adiel Thomas[76] who won US$5,000,[78] and a third-place song titled One CARICOM by Carmella Lawrence of St. Kitts and Nevis,[76] won US$2,500.[78] The other songs from the top-ten finalists (in no particular order) were:

- One Region one Caribbean from Anguilla,

- One Caribbean Family from Jamaica,

- CARICOM’s Light from St. Vincent & the Grenadines,

- We Are CARICOM from Dominica,

- Together As one from Dominica,

- Blessed CARICOM from Jamaica,

- Together We Rise from Jamaica.[77]

The first official performance of Celebrating CARICOM by Henderson took place on Tuesday 1 July 2014 at the opening ceremony for the Thirty-Fifth Regional Meeting of the Conference of Heads of Government in Antigua and Barbuda.[76]

Celebration

[edit]CARICOM Day

[edit]The celebration of CARICOM Day is the selected day some Caribbean Community (CARICOM) countries officially recognise the commemorative date of signing of the Treaty of Chaguaramas, the agreement that established CARICOM on 4 July 1973. The Treaty was signed in Chaguaramas, Trinidad & Tobago by then leaders of: Barbados, Guyana, Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago. CARICOM Day is recognised as an official public holiday in Guyana where the secretariat is based, and is observed on the first Monday of July. The government of Antigua and Barbuda has also implemented CARICOM Day as a holiday.

The day features activities that are organised by government entities such as parades, pageants, and campaigns to educate people about CARICOM.

Caribbean Festival of Arts – CARIFESTA

[edit]Caribbean Festival of Arts, commonly known as CARIFESTA, is an annual festival for promoting arts of the Caribbean with a different country hosting the event each year. It was started to provide a venue to "depict the life of the people of the Region, their heroes, morals, myths, traditions, beliefs, creativity and ways of expression"[79] by fostering a sense of Caribbean unity, and motivating artists by showing the best of their home country. It began under the auspices of Guyana's then President Forbes Burnham in 1972, who was inspired by other singular arts festivals in the region.

See also

[edit]- List of diplomatic missions in Guyana

- Association of Caribbean States

- EU/UK–CARIFORUM

- CARIFORUM–United Kingdom Economic Partnership Agreement

- CSME

- Caribbean Financial Action Task Force

- Caribbean Initiative

- Caribbean Agricultural Research and Development Institute (CARDI)

- Caribbean Accreditation Authority for Education in Medicine and other Health Professions

- Caribbean Knowledge and Learning Network

- Community of Latin American and Caribbean States

- Commonwealth of Nations

- Languages of the Caribbean

- List of regional organizations by population

- North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)

- North American Union (NAU)

- Organisation of African, Caribbean and Pacific States

- Organization of American States

- Petrocaribe

- Projects of the Caribbean Community

- Small Island Developing States

- Union of South American Nations (UNASUR)

- West Indies

References

[edit]- ^ a b Staff writer (2024). "Caribbean Community (CARICOM)". UIA Global Civil Society Database. uia.org. Brussels, Belgium: Union of International Associations. Yearbook of International Organizations Online. Retrieved 24 December 2024.

- ^ "Our Symbols — Caribbean Community (CARICOM)". Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ^ a b c "Who we are". Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- ^ "Spanish agreed as CARICOM second language". www.landofsixpeoples.com. Archived from the original on 18 August 2021. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- ^ a b "Our Culture". Archived from the original on 26 September 2020. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- ^ "The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Archived from the original on 10 May 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2007.

- ^ EU Style Structure Evident in CARICOM

- ^ a b "CARICOM – Caribbean Community 2021". countryeconomy.com. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- ^ "GDP, current prices. Purchasing power parity; billions of international dollars". IMF. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021.

- ^ List of countries by HDI

- ^ Ramjeet, Oscar (16 April 2009). "CARICOM countries will speak with one voice in meetings with US and Canadian leaders". Caribbean Net News. Archived from the original on 13 July 2016. Retrieved 16 April 2009.

- ^ "Intergovernmental Organizations". United Nations. Archived from the original on 23 May 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ^ "Original Treaty of Chaguaramas". Archived from the original on 11 October 2007.

- ^ "Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 November 2011.

- ^ "Aristide accuses U.S. of forcing him out". Canadian Broadcast Corporation. 2 March 2004. Archived from the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ "Aristide launches kidnap lawsuit". BBC News. 31 March 2004. Archived from the original on 9 December 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ "Haiti suspends ties with CARICOM". www.trinidadandtobagonews.com. Retrieved 14 April 2024.

- ^ "Haiti suspends ties with CARICOM". Trinidadandtobagonews.com. Archived from the original on 22 September 2009. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ "Haiti could return to CARICOM". The Gleaner. 10 February 2006. Archived from the original on 23 September 2010.

- ^ "BBCCaribbean.com | Haitian results in next two days". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 14 April 2024.

- ^ "Caricom and Haiti: The raising of the Caribbean's 'Iron Curtain'". The Gleaner. 8 October 2006. Archived from the original on 23 September 2010.

- ^ a b Caribbean moves afoot to restructure CARIFORUM Archived 17 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Peter Richards, Tuesday 12 April 2011

- ^ a b "Letter: Privy Council and EPA". The Gleaner. 8 October 2009. Archived from the original on 21 August 2014.

- ^ Gibbs, Anselm (1 October 2025). "Four Caribbean nations sign deal allowing citizens to move freely without visas or work permits". Associated Press. Retrieved 15 October 2025.

- ^ "Communiqué Issued at the Conclusion of the Thirty-Third Regular Meeting of the Conference of Heads of Government of the Caribbean Community, 4–6 July 2012, Gros Islet, Saint Lucia" Archived 16 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine, "Heads of Government recognized that, although English was the official language of the Community, the facility to communicate in their languages could enhance the participation of Haiti and Suriname in the integration process. They therefore requested the conduct of a study to examine the possibilities and implications, including costs, of introducing French and Dutch."

- ^ "CARICOM (Revised Treaty)" (PDF). (573 KB)

- ^ "Organisational structure" (PDF). CARICOM. 13 March 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 January 2010.

- ^ "Regional Portfolios of CARICOM Heads of Government". 2 May 2008. Archived from the original on 2 May 2008.

- ^ "Overview- CARICOM Secretariat". CARICOM. 19 September 2023. Archived from the original on 27 May 2022. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ Caricom Law: Website and online database of the CARICOM Legislative Drafting Facility (CLDF)

- ^ Caricom, Institutions Archived 4 May 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ CARICOM Regional Organisation for Standards and Quality (CROSQ)

- ^ a b c "Evolution of the Association of Caribbean States" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ "Mexidata (English) March 1, 2010". Mexidata.info. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ^ "Acuerdan crear Comunidad de Estados Latinoamericanos y Caribeños". Associated Press. 23 February 2010. Archived from the original on 9 June 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- ^ "América Latina crea una OEA sin Estados Unidos". El País. 23 February 2010. Archived from the original on 22 February 2022. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- ^ "Rio Group approves its expansion at Unity Summit". Archived from the original on 10 August 2016. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- ^ a b "CCJ signs MOU on harmonising business law in Caribbean". today.caricom.org. 20 May 2016. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- ^ CIA World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 2017. p. 971. ISBN 9781510712898. Archived from the original on 22 October 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- ^ a b c "Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 November 2011.

- ^ a b "30,000 Jamaicans residing in other CARICOM member states". Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ a b "PM Golding Calls on Jamaicans in Antigua & Barbuda to Co-Operate with Government & People There". Jamaica Information Service. 7 July 2008. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- ^ "Close to 17,000 Jamaicans residing illegally in Trinidad, newspapers says". Jamaica Observer. 26 November 2013. Archived from the original on 27 April 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ "7 000 illegal Bajans in T&T". NationNews. 16 October 2014. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- ^ "Bissessar celebrates new Trinidad &Tobago high commission". The Gleaner. 17 April 2015. Archived from the original on 20 April 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ "Guyanese, British and Americans among illegal immigrants living in Barbados". Carib News Now. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- ^ Lewis, Linden (1 August 2011). "Mudheads in Barbados: A Lived Experience". Stabroek News. Archived from the original on 29 January 2024.

- ^ "Languages of Suriname". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 27 April 2015.

- ^ a b Holbrook, David J.; Holbrook, Holly A. (2001). "Guyanese Creole Survey Report" (PDF). SIL International. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 March 2016.

- ^ "Guyanese vital in Suriname". guyana-cricket.com. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020.

- ^ "Nervous neighbours: Guyana and Suriname". 5 November 2008.

- ^ "Guyana Migration Profiles" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 April 2015. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ "CARICOM-Cuba Trade and Economic Cooperation Agreement". Retrieved 14 April 2024.

- ^ Rodriguez Parrilla, Bruno Eduardo (14 June 2019). "CARICOM-Cuba: Only integration will allow us to prosper". CubaDebate.cu (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- ^ AMBASSADORS ACCREDITED TO THE CARIBBEAN COMMUNITY (CARICOM) (As of December 2024)

- ^ Foreign Heads Of Missions Resident In Guyana Archived 2 February 2025 at the Wayback Machine, Guyana Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation

- ^ writer, Staff (24 October 2024). "CARICOM-African Union Memorandum of Understanding". Caribbean Community Secretariat. Archived from the original on 18 June 2025. Retrieved 25 May 2025.

- ^ Embassy of Argentina in Guyana

- ^ Australian High Commission Trinidad and Tobago

- ^ Canada and the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), Global Affairs Canada

- ^ Relations Archived 9 February 2025 at the Wayback Machine, High Commission of India, Georgetown, Guyana

- ^ Embassy of Israel, Panama

- ^ Countries and Regional Organizations the Embassy of Japan in T&T Covers

- ^ About the ambassador of MX to Guyana

- ^ MX Embassy to Guyana

- ^ NZ Embassies and consular services for Caribbean

- ^ NZ and the Americas, New Zealand Foreign Affairs & Trade

- ^ Singapore Plenipotentiary Representative to the Caribbean Community (Caricom)

- ^ "Türkiye's Relations with the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) / Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Foreign Affairs".

- ^ CARICOM Statistics: Statistical information compiled through the CARICOM Secretariat

- ^ "Land area rankings". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 20 October 2018. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ^ "Gross domestic product based on purchasing-power-parity (PPP) valuation of country GDP Archived 2015-02-09 at the Wayback Machine" (2013). World Economic Outlook Database 2014. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 23 December 2017..

- ^ Human Development Report 2025 - A matter of choice: People and possibilities in the age of AI. United Nations Development Programme. 6 May 2025. Archived from the original on 6 May 2025. Retrieved 6 May 2025.

- ^ a b "CARICOM: Our Symbols". Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ^ "Caribbean Community and Common Market". www.crwflags.com. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "History created as new CARICOM song is launched". Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ^ a b c "WORD Version of CARICOM song competition Fact Sheet". 3 July 2014. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- ^ a b c "CARICOM Song Competition: Terms of Reference" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 May 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ^ "History of CARIFESTA". CARICOM. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 15 March 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- Quinones de Longo, Clara (21 September 2005). "The Dominican Republic in Caricom? Yes, we can". Caribbean Net News. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2025.

- Staff writer (19 October 2006). "Bureau recommends re-examination of Dominican Republic's proposed membership in CARICOM". Caribbean News Now. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2025.

- Edwards, Al (27 October 2006). "How viable is a single Caribbean currency? Part II". Jamaica Observer. Archived from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 10 February 2025.

- Edwards, Al (27 October 2006). "How viable is a single Caribbean currency? Part III". Jamaica Observer (published 7 December 2006). Archived from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 10 February 2025.

- Ishmael, Odeen (July 2007). "Advancing Integration Between Caricom and Central America". Guyana Journal. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 11 February 2025.

- writer, writer, ed. (4 July 2010). "EDITORIAL: We may just have to dump CARICOM". Jamaica Gleaner. Retrieved 11 February 2025.

- Ramjeet, Oscar (5 July 2010). "Commentary: Gleaner newspaper suggests disbanding CARICOM". Caribbean New Now. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2025.

- Staff writer (12 July 2010). "Does Caricom have a future?". BBC Caribbean. BBC UK. Retrieved 11 February 2025.

- Staff writer (7 July 2010). "That elusive governance structure". BBC Caribbean. BBC UK. Retrieved 11 February 2025.

- CARICOM Representation Office in Haiti (CROH)

- Radio CARICOM: the voice of the Caribbean Community (Press Release)

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Official Blog Archived 30 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine CARICOM Today

- Caricom Trade Support Programme: Government of Trinidad and Tobago

- CARICOM Trade Support Programme Loan Archived 29 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Rapid Exchange System for Dangerous Non-food Consumer Goods (CARREX): Front end for Consumer Product Incident Reporting [permanent dead link]

Caribbean Community

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Historical Development

Pre-CARICOM Integration Efforts

The West Indies Federation represented the first major post-colonial attempt at political and economic union among British Caribbean territories, established on 3 January 1958 under the British West Indies Federation Order in Council.[11] It encompassed ten territories: Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Dominica, Grenada, Jamaica, Montserrat, Saint Kitts-Nevis-Anguilla, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Trinidad and Tobago, with a combined population of approximately 3 million and a federal capital in Port of Spain, Trinidad.[11] The federation's objectives centered on achieving collective self-government en route to full independence from Britain, harmonizing economic policies, and creating a customs union to address small market sizes and dependency on external trade, particularly with the UK and US.[12] A federal parliament with 45 representatives and a bicameral structure was instituted, alongside a British-appointed governor-general, but limited fiscal powers and reliance on contributions from member units hampered central authority.[13] Internal divisions, including disputes over fiscal equalization, representation, and external relations—exacerbated by Jamaica's and Trinidad's larger populations demanding greater influence—undermined the federation.[12] Jamaica held a referendum on 19 September 1961, where 54% voted against federation, prompting its withdrawal effective 19 August 1962; Trinidad and Tobago followed suit after a similar poll in January 1962.[14] The federation formally dissolved on 31 May 1962, reverting territories to individual paths toward independence, such as Jamaica's on 6 August 1962.[11] This failure highlighted challenges of political unification amid insular nationalisms and economic disparities but spurred reflection on looser economic cooperation as a viable alternative.[4] Post-federation, Commonwealth Caribbean heads of government convened multiple conferences to explore integration, including the 1963 Trinidad meeting and the 1965 Dickenson Bay conference in Antigua, which laid groundwork for trade liberalization.[15] These culminated in the Caribbean Free Trade Association (CARIFTA), formalized by the Dickenson Bay Agreement signed on 15 December 1965 by Antigua (representing the Leeward and Windward Islands), Barbados, Guyana, and Trinidad and Tobago.[15] Operational from 1 May 1968, CARIFTA sought to expand intra-regional trade—initially minimal at under 10% of members' total—through phased tariff reductions, elimination of quantitative restrictions, and harmonization of external tariffs, without deep political commitments.[16] Membership expanded in 1970 to include Dominica, Grenada, Saint Lucia, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines as full members, followed by Jamaica and Belize in 1971, reaching seven full participants by 1972.[17] CARIFTA's achievements included a tripling of intra-regional trade volumes by 1972 and establishment of institutions like the Commonwealth Caribbean Regional Secretariat, but persistent barriers such as non-tariff measures and unequal benefits among larger (e.g., Trinidad) and smaller economies limited deeper integration.[18] The 1967 Bridgetown conference of heads of government reinforced commitments to economic unity, setting the stage for CARICOM's broader framework by emphasizing functional cooperation over federation-style politics.[19] These efforts underscored a pragmatic shift toward market-oriented mechanisms, informed by the federation's collapse, to counterbalance small-state vulnerabilities in global trade.[20]Formation and the Treaty of Chaguaramas

The Caribbean Community (CARICOM) was formally established by the Treaty of Chaguaramas, signed on July 4, 1973, in Chaguaramas, Trinidad and Tobago, by the Heads of Government of Barbados, Guyana, Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago.[21] [1] These four nations served as the founding members, building on the framework of the Caribbean Free Trade Association (CARIFTA), which had been operational since 1968 but limited to tariff reductions without deeper economic harmonization.[17] The treaty's negotiation reflected post-colonial aspirations for regional self-reliance amid global economic pressures, including vulnerability to commodity price fluctuations and the need for collective bargaining in international trade.[21] The treaty's core provisions outlined the creation of a Caribbean Common Market to promote the free movement of goods, services, capital, and labor among members, alongside functional cooperation in areas such as health, education, culture, transport, and telecommunications.[1] It established principal institutions, including the Conference of Heads of Government as the supreme policy-making body, the Common Market Council for trade and economic integration, and a Secretariat headquartered in Georgetown, Guyana, to oversee implementation.[1] Unlike CARIFTA's focus solely on trade liberalization, the treaty emphasized accelerated economic development, improved living standards, full employment, and coordinated foreign policy to enhance the region's negotiating power with larger economies.[21] The treaty entered into force on August 1, 1973, for the signatory states, marking the official replacement of CARIFTA with CARICOM and initiating a phased approach to common market protocols, including the elimination of tariffs on intra-regional goods over specified timelines.[21] Subsequent accessions, such as those by Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, Grenada, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Montserrat on April 17, 1974 (effective May 1, 1974), expanded the community without altering the foundational treaty structure.[21] This formation laid the groundwork for ongoing revisions, but the original document prioritized pragmatic economic union over immediate political federation, reflecting lessons from the dissolved West Indies Federation of 1958–1962.[21]Post-Establishment Evolution and Treaty Revisions

Following the entry into force of the original Treaty of Chaguaramas on August 1, 1973, for its four founding members—Barbados, Guyana, Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago—CARICOM expanded its membership through subsequent accessions. Belize joined as a full member on May 1, 1974, followed by the Bahamas on July 4, 1983, which opted into the Community but not the Common Market until later protocols.[22] Suriname acceded on July 4, 1995, and Haiti became the fifteenth full member on July 2, 2002, marking the inclusion of a French-speaking state to broaden linguistic and cultural representation.[21] Associate membership grew in the 1990s, with the British Virgin Islands and Turks and Caicos Islands joining on July 2, 1991, Anguilla on July 4, 1999, and the Cayman Islands subsequently, enabling non-independent territories to participate in functional cooperation without full economic integration.[21] Early post-establishment efforts focused on establishing institutions and reducing trade barriers, but progress stalled amid economic disparities and external shocks, prompting calls for deeper integration. The 1989 Grand Anse Declaration by Heads of Government committed to transforming CARICOM into a more effective economic union, emphasizing human resource development and a single market.[6] This culminated in the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas, signed on July 5, 2001, in Nassau, Bahamas, by all member states except Haiti (which signed later).[23] The revised treaty entered into force on February 4, 2002, for ratifying states, establishing the Caribbean Community including the CARICOM Single Market and Economy (CSME).[24] It expanded objectives beyond the original common market to include free movement of goods, services, capital, and skilled nationals; harmonized economic policies; and a common external commercial policy, while retaining provisions for foreign policy coordination and functional cooperation in areas like health and education.[23] Subsequent revisions addressed implementation gaps in the CSME, which has seen partial rollout—such as the Common External Tariff adopted by most members by 2006 but with persistent non-tariff barriers. In April 2025, Jamaica signed a protocol amending the Revised Treaty, replacing Article 50 to allow accelerated integration initiatives by groups of at least three member states, aiming to bypass consensus delays on issues like digital trade and dispute settlement.[25] This reflects ongoing adaptations to sovereignty constraints and asymmetric capacities, with the CSME's full operationalization remaining incomplete as of 2025 due to varying national ratifications and enforcement challenges.[26]Core Mandate and Objectives

Economic Integration and Common Market Goals

The economic integration objectives of the Caribbean Community center on fostering a unified market to drive sustainable development, full employment, and coordinated growth among member states, with special measures for less developed countries (LDCs) such as Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, Grenada, Montserrat, Saint Lucia, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines.[6] These goals build on the original Treaty of Chaguaramas, signed on 4 July 1973, which established the Caribbean Community and Common Market to eliminate tariffs and trade barriers among members, and were deepened by the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas, signed on 5 July 2001 and entering into force on 4 February 2002 for ratifying states.[6] The revised treaty introduced the Caribbean Single Market and Economy (CSME) as the primary mechanism, aiming to create a single economic space through the free movement of goods, services, capital, and persons, thereby enhancing regional competitiveness, expanding trade with third countries, and promoting diversified production.[6] Central to the CSME is the removal of restrictions on intra-regional trade, including prohibitions on new barriers and phased elimination of existing ones, to establish free circulation of goods originating within the Community.[6] A Common External Tariff (CET) applies to non-Community imports, with rates managed by the Council for Trade and Economic Development (COTED) and adjustable based on supply-demand conditions, such as suspensions for insufficient regional production; for instance, Schedule IV protects Guyanese petroleum products via specific duties.[6] Rules of origin require goods to be "wholly obtained" in the Community or meet regional value content thresholds—typically 65-70% for more developed countries (MDCs) like Barbados and Trinidad and Tobago, with relaxed 50-60% thresholds for LDCs to facilitate their integration.[6] These measures support a market-led industrial policy focused on sustainable, competitive output, complemented by harmonized standards, mutual recognition agreements, and transit freedoms for goods and vessels.[6] The right of establishment and provision of services are liberalized under Articles 32-40, allowing Community nationals to set up businesses and offer services without discrimination, subject to phased programs that account for LDC vulnerabilities.[6] Capital movements face no restrictions except for balance-of-payments safeguards, while free movement of persons begins with skilled categories—university graduates, artisans, sports professionals, and media workers—granting rights to work, reside, and access social services upon proof of skills.[6] In July 2023, Heads of Government decided to extend full free movement to all nationals by March 2024, though implementation has progressed unevenly, with only four states committing to full rollout by October 2025 amid ongoing harmonization of immigration laws.[27][28] Policy coordination under the Community Council of Ministers and bodies like the Council for Finance and Planning (COFAP) targets fiscal and monetary convergence, including stable currencies, investment incentive harmonization, and competition rules enforced by a regional Competition Commission.[6] LDCs receive targeted support via special regimes (Article 142), a Development Fund for grants and technical aid, and transitional interventions to build competitiveness, addressing disparities that could otherwise hinder uniform integration.[6] Despite these frameworks, official assessments highlight persistent gaps in legal harmonization and enforcement, limiting realized benefits like intra-regional trade growth, which remains below potential due to non-tariff barriers and uneven ratification.[29]Political Coordination and Functional Cooperation Aims

The aims of political coordination within the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) center on harmonizing the foreign policies of member states to promote collective interests on the international stage. Article 17 of the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas, signed on July 5, 2001, mandates that member states pursue the "fullest possible co-ordination of their foreign policy" and "endeavour to adopt, wherever possible, common positions on international issues."[6] This coordination seeks to amplify the region's voice in global forums, such as negotiations on trade, climate change, and security, where small island states face disproportionate vulnerabilities. For instance, CARICOM has pursued unified stances in multilateral bodies like the United Nations and World Trade Organization, evidenced by joint advocacy for special treatment as small developing states since the treaty's inception.[23] However, implementation has varied due to differing national priorities, with successes in areas like debt relief campaigns but challenges in achieving consensus on bilateral relations with major powers.[30] Functional cooperation aims extend beyond economics to foster collaboration in social, cultural, health, educational, scientific, and technological domains, aiming to build regional resilience and human capital. Under Chapter Four of the Revised Treaty, member states commit to joint programs in these areas to address shared challenges, such as public health crises and educational disparities, with the Council for Human and Social Development overseeing implementation.[6] Specific initiatives include the Caribbean Public Health Agency (CARPHA), established in 2011 to coordinate responses to epidemics like COVID-19, and regional examinations like the Caribbean Secondary Education Certificate (CSEC), administered since 1972 to standardize qualifications across 16 countries.[23] These efforts have yielded measurable outcomes, such as harmonized disaster response protocols post-Hurricane Maria in 2017, but face constraints from limited funding and uneven member participation, with intra-regional projects often relying on external donors.[31] Overall, functional cooperation prioritizes pooling scarce resources for mutual benefit, contrasting with more fragmented national approaches.[22]Institutional and Organizational Structure

Principal Organs and Decision-Making Bodies

The principal organs of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) are the Conference of Heads of Government and the Community Council of Ministers, as defined in the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas signed on July 5, 2001.[6] These bodies hold ultimate authority over Community policies, with the Conference serving as the apex decision-making forum responsible for approving strategic directions, resolving disputes, and endorsing recommendations from subordinate organs.[32] The Conference convenes at least biannually, typically in July and intersessional meetings as needed, with decisions made by consensus among heads of government or their designated representatives from the 15 full member states.[33] Chairmanship rotates annually among member heads on a predetermined schedule, ensuring equitable leadership distribution; for instance, Jamaica assumed the chair on July 1, 2025, under Prime Minister Andrew Holness.[34] The Community Council of Ministers, comprising one minister per member state (usually responsible for foreign affairs, economic integration, or community affairs), acts as the executive arm to coordinate and implement Conference directives across economic, political, and functional cooperation spheres.[32] It meets as required to oversee progress on integration goals, such as the Caribbean Single Market and Economy (CSME), and refers matters to specialized ministerial councils for detailed policy formulation.[35] This structure promotes collective decision-making while respecting national sovereignty, with binding decisions requiring unanimity unless otherwise specified in protocols.[6] Supporting the principal organs are five ministerial-level Organs of the Community, each focused on delineated policy domains: the Council for Trade and Economic Development (COTED), which promotes intra-regional trade and CSME implementation; the Council for Finance and Planning (COFAP), addressing fiscal policy harmonization and development funding; the Council for Foreign and Community Relations (COFCOR), managing external diplomacy and international partnerships; the Council for Human and Social Development (COHSOD), handling health, education, and social cohesion initiatives; and the Council for National Security and Law Enforcement (CONSLE), coordinating responses to transnational crime and security threats.[32] These organs formulate recommendations for principal organ approval, with compositions drawn from relevant national ministers, and operate through technical committees for operational efficiency.[36] Three auxiliary Bodies further facilitate decision-making: the Legal Affairs Committee, which advises on treaty compliance and dispute resolution; the Budget Committee, responsible for Secretariat funding and financial oversight; and the Committee of Central Bank Governors, which harmonizes monetary policies and supports economic stability.[32] The CARICOM Secretariat, headquartered in Georgetown, Guyana, since 1973, functions as the central administrative organ under a Secretary-General (currently Carla Barnett, appointed February 1, 2021), executing decisions, conducting research, and managing day-to-day operations with a staff of approximately 70.[33] This institutional framework, evolved from the original 1973 Treaty, emphasizes consensus-driven governance to advance economic integration amid diverse member capacities, though implementation challenges persist due to varying national commitments.[6]Secretariat Operations and Administration

The CARICOM Secretariat functions as the principal administrative organ of the Caribbean Community, tasked with coordinating regional integration efforts and supporting Member States in enhancing the quality of life for Community citizens through innovative, sustainable, and competitive development. Headquartered in Turkeyen, Greater Georgetown, Guyana, since its establishment, the Secretariat maintains an additional office in Barbados to facilitate operations across the region. It operates under the directives of the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas, particularly Article 23, which designates it as the central mechanism for servicing Community Organs and implementing decisions.[37][32] Core operational functions, as outlined in Article 25 of the Revised Treaty, encompass servicing meetings of Organs and Bodies with follow-up on resulting determinations; preparing and circulating studies, position papers, and reports; mobilizing external financial and technical resources from donor agencies; undertaking research and disseminating information; managing projects; fostering technical cooperation; and maintaining custody of Community treaties, agreements, and documents. These activities emphasize coordination with donor institutions, foreign relations, and project execution to advance economic, political, and functional cooperation among members. The Secretariat also plays a pivotal role in information management and capacity-building initiatives, such as recent efforts to enhance trade data dissemination and disaster risk management.[38][32][39] Administratively, the Secretariat underwent a structural revision on March 10, 2022, aimed at refocusing its directorates and offices to bolster efficiency, strengthen service delivery to Member States, and align with evolving regional priorities like resilience and productivity. Strategic oversight is provided by the Executive Management Committee, comprising senior officials responsible for directing organizational operations and collaborating with the Conference of Heads of Government and Community Council of Ministers. The Budget Committee, composed of senior Member State officials, scrutinizes the Secretariat's annual draft work programme and budget, forwarding recommendations to the Community Council for approval, ensuring fiscal accountability in resource allocation for administrative and programmatic needs.[40][41][32] Under the leadership of Secretary-General Dr. Carla Natalie Barnett, appointed on August 15, 2021, the Secretariat emphasizes partnerships for resource mobilization and implementation support, as highlighted in statements from deputy leadership on leveraging external development aid. This administrative framework supports the broader mandate by facilitating evidence-based policy coordination, though challenges in budget growth—such as the voluntary freeze at approximately EC$45.5 million in 2009—underscore ongoing dependencies on Member State contributions and donor funding for sustained operations.[42][43][44]Chairmanship and Leadership Mechanisms

The chairmanship of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) is held by the Chairperson of the Conference of Heads of Government, the organization's supreme organ responsible for major decisions, including foreign policy coordination, membership admissions, and approval of treaties. The position rotates every six months among the heads of government of full member states, following a predetermined schedule published by the CARICOM Secretariat to promote equitable burden-sharing and prevent dominance by any single nation. This mechanism, outlined in operational protocols rather than explicit treaty mandates, alternates leadership to reflect the diverse sizes and influences of members, with rotations typically adhering to a sequence that balances more developed states like Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago with smaller ones like Grenada and Saint Lucia. For instance, the schedule from 2020 to 2035 specifies periods such as Grenada's tenure from July 1 to December 31, 2024, followed by Barbados from January 1 to June 30, 2025, and Jamaica from July 1 to December 31, 2025.[45][46] To ensure continuity across rotations, the Bureau of the Conference—comprising the incumbent Chairperson, the incoming Chairperson, and the outgoing Chairperson—serves as a sub-committee for ongoing coordination and agenda preparation. The Bureau meets as needed to address urgent matters, bridging gaps between semi-annual Conferences and maintaining momentum on initiatives like economic integration or crisis response. The Chairperson, during their term, represents CARICOM in international forums, convenes special meetings, and sets priorities for the Conference, which requires consensus for binding decisions on core issues. Adjustments to the rotation occur rarely but have been applied in response to domestic instability; for example, in January 2025, Barbados's Prime Minister Mia Mottley assumed the role ahead of Haiti's scheduled turn due to the latter's political turmoil, preserving institutional functionality without formal suspension.[47][48] Complementing the rotating chairmanship, the Secretary-General provides administrative leadership as head of the CARICOM Secretariat, appointed by the Conference for a five-year renewable term to implement decisions and manage daily operations. The current Secretary-General, Carla Barnett of Belize, assumed office on August 1, 2021, overseeing non-voting advisory roles in the Conference while directing functional cooperation in areas like trade and disaster response. This dual structure—rotational political leadership via the chairmanship and stable bureaucratic oversight—aims to balance member sovereignty with collective efficacy, though critics note that frequent turnovers can hinder long-term strategic focus compared to more permanent secretariats in other regional bodies.[49][32]Membership Composition

Full Member States and Their Contributions

The Caribbean Community (CARICOM) consists of 15 full member states, each with equal voting rights in decision-making bodies regardless of population or economic size. These states are Antigua and Barbuda, The Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Haiti, Jamaica, Montserrat, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago.[5] Full members subscribe to the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas, committing to economic integration, functional cooperation, and foreign policy coordination.[5] Founding members Barbados, Guyana, Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago signed the original Treaty of Chaguaramas on August 1, 1973, establishing CARICOM as the successor to the Caribbean Free Trade Association (CARIFTA) to deepen regional economic ties.[21] [3] Other states acceded shortly thereafter: Antigua and Barbuda, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Montserrat, Saint Lucia, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines in 1974; The Bahamas in 1983; Suriname in 1995; and Haiti as the first full French-speaking member on July 3, 2002.[21] [50] Saint Kitts and Nevis joined in 1974, achieving full status upon independence in 1983.[21] Contributions from full members include financial assessments to the CARICOM budget, hosting of principal organs, and leadership in policy implementation. Guyana hosts the CARICOM Secretariat in Georgetown, serving as the administrative hub since the organization's inception.[49] [2] Trinidad and Tobago hosts the CARICOM Implementation Agency for Crime and Security (IMPACS), supporting regional intelligence sharing and law enforcement coordination.[51] All members participate in biannual Conferences of Heads of Government, where they shape priorities such as the Caribbean Single Market and Economy (CSME), with larger economies like Trinidad and Tobago influencing energy policy due to its petroleum exports, though decisions require consensus.[5] [3] The equal representation principle ensures smaller states, such as those in the Eastern Caribbean, contribute disproportionately to per-capita regional initiatives like disaster response and human development programs.[5]Associate Members and Observers

The Caribbean Community accords associate membership to select non-sovereign Caribbean territories and entities, granting them rights to participate in functional cooperation initiatives, such as those in health, education, and disaster management, while allowing attendance at key meetings like the Conference of Heads of Government in an observer capacity without voting privileges or obligations to implement Community decisions.[52] This status facilitates regional engagement for dependencies lacking full sovereignty, aligning with CARICOM's broader aims of inclusive cooperation amid shared vulnerabilities like hurricanes and economic interdependence.[22] As of October 2025, CARICOM comprises six associate members, primarily British Overseas Territories and one Dutch constituent country:| Associate Member | Notes |

|---|---|

| Anguilla | British Overseas Territory; participates in sectors like tourism and financial services coordination.[52] |

| Bermuda | British Overseas Territory; focuses on insurance and reinsurance collaboration.[52] |

| British Virgin Islands | British Overseas Territory; engages in maritime and environmental initiatives.[52] |

| Cayman Islands | British Overseas Territory; contributes to financial regulation harmonization efforts.[52] |

| Turks and Caicos Islands | British Overseas Territory; involved in fisheries and climate resilience programs.[52] |

| Curaçao | Constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands; acceded on 28 July 2024 via agreement with CARICOM leadership, emphasizing trade and cultural ties.[2][53] |

Cases of Suspension, Withdrawal, or Exclusion

Haiti's participation in the Caribbean Community was suspended following the political upheaval of 2004, marking the only significant instance of membership interruption in CARICOM's history. On March 16, 2004, Haiti's interim Prime Minister Gérard Latortue announced the temporary suspension of the country's membership, citing tensions with CARICOM over the ousting of President Jean-Bertrand Aristide earlier that month.[55] This action followed CARICOM's emergency meetings, where Heads of Government condemned the removal of Aristide as an unacceptable extra-constitutional change and refused recognition of the interim administration until restoration of constitutional order and democratic elections.[56] [57] CARICOM maintained that Haiti remained a formal member but effectively halted engagement with the Latortue government, suspending participation in regional bodies and cooperation until democratic processes were reinstated.[58] The interruption lasted over two years, ending in June 2006 after the election of President René Préval, when CARICOM readmitted Haiti as a full participating member, underscoring the community's commitment to governance based on democratic elections.[59] No formal withdrawals from CARICOM have occurred since its founding in 1973, despite provisions in Article 27 of the Treaty of Chaguaramas allowing a member state to exit by providing written notice to the Secretariat.[60] Occasional political rhetoric, such as Jamaican discussions in the early 2010s about potential suspension or exit amid frustrations with economic integration, has not led to action.[61] Similarly, no member states have faced exclusion, reflecting the organization's emphasis on consensus and voluntary cooperation rather than punitive measures beyond the Haiti precedent.Economic Framework and Initiatives

Caribbean Single Market and Economy (CSME)

The Caribbean Single Market and Economy (CSME) constitutes the primary economic integration mechanism within the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), designed to foster a unified economic space through the liberalization of trade in goods and services, the free movement of capital, and the mobility of skilled labor among participating states. Established via the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas, signed on 5 July 2001 in Nassau, Bahamas, the CSME replaced earlier provisions of the original 1973 Treaty and entered provisional application for core elements such as goods trade liberalization starting 1 January 2006, with subsequent phases addressing services, capital, and persons.[23][6] As of 2024, 12 full CARICOM member states—Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago—have implemented key CSME protocols, while Haiti, Montserrat, and the Bahamas maintain partial or observer status due to ratification delays or domestic constraints.[62] Core objectives include the elimination of tariffs and non-tariff barriers on intra-regional goods trade, the harmonization of macroeconomic policies to support monetary coordination, and the establishment of common external tariffs against non-CARICOM imports to enhance competitiveness.[63] Provisions for the right of establishment allow CARICOM nationals to set up businesses across borders without discriminatory treatment, while skilled nationals—initially in categories such as university graduates, artisans, and media professionals—gain facilitated access to employment markets, with expansions to include service providers in sectors like nursing and engineering.[64] These measures aim to boost economic resilience against external shocks, such as commodity price volatility, by promoting intra-regional supply chains and reducing dependence on extra-regional markets.[65] Implementation has advanced unevenly, with full tariff removal on substantially all goods achieved by most participants by 2015, yet persistent non-tariff obstacles like disparate sanitary and phytosanitary standards and administrative delays have constrained services and capital flows.[31] Intra-CARICOM trade as a share of total exports rose gradually from under 5% in the 1980s to around 12-15% by 2018, reflecting modest gains in goods liberalization, though services trade integration lags due to regulatory fragmentation.[31] In agriculture and food products, a priority sector, intra-regional exchanges doubled between 2000 and 2023, driven by exports from Guyana, Belize, and Suriname displacing extra-regional imports in staples like rice and poultry.[66] Empirical assessments indicate that while the CSME has facilitated targeted mobility—evidenced by over 20,000 skilled certificates issued annually by 2023—broader free movement of labor remains limited by national security concerns and capacity gaps in border management.[67] Challenges to deeper integration stem from structural economic divergences, including the more developed economies of Trinidad and Tobago and Barbados versus less industrialized states reliant on services and remittances, which have slowed policy harmonization.[31] Over a decade after the 2001 commitment, key CSME institutions like the Caribbean Court of Justice's Original Jurisdiction for dispute settlement have adjudicated fewer than 50 cases by 2024, underscoring administrative inefficiencies and uneven ratification of protocols.[68] Recent efforts, including 2024-2025 data harmonization initiatives for free movement tracking, seek to address these through improved national reporting to the CSME Unit, but causal factors such as fiscal indiscipline and external debt burdens—averaging 70% of GDP across members—continue to impede capital mobility and joint investment funds.[67][69] Despite these hurdles, the framework has empirically supported resilience, as seen in coordinated responses to global supply disruptions post-2020, where intra-regional sourcing mitigated import shortfalls.[70]Free Trade Agreements and External Partnerships

The Caribbean Community coordinates its external trade relations through the Council for Trade and Economic Development (COTED), seeking progressive harmonization of policies with third countries to expand market access while protecting regional interests.[6] This approach has resulted in several bilateral and regional trade arrangements, primarily partial-scope agreements that provide preferential access rather than comprehensive free trade zones, supplemented by unilateral preferences from major partners like the United States via the Caribbean Basin Initiative and Canada through CARIBCAN.[71] The most significant reciprocal external agreement is the Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) between CARIFORUM states (CARICOM members plus the Dominican Republic) and the European Union, signed on October 15, 2008, and provisionally applied from December 2008 for most parties.[72] This WTO-compatible pact eliminates tariffs on substantially all trade in goods over time, liberalizes services and investment, and includes development cooperation provisions, though implementation has faced challenges related to rules of origin and capacity building.[73] Other key bilateral agreements include:- The CARICOM-Dominican Republic Free Trade Agreement, signed August 22, 1998, and entered into force February 5, 2002, offering reciprocal duty reductions for more developed CARICOM countries (MDCs) on select goods while applying most-favored-nation rates for less developed countries (LDCs).[74]

- The CARICOM-Costa Rica Free Trade Agreement, signed March 9, 2004, and phased into force starting November 15, 2005, covering goods with schedules for tariff elimination and provisions for future services negotiations.[75]

- The CARICOM-Colombia Agreement on Trade, Economic, and Technical Cooperation, signed July 24, 1994, and effective January 1, 1995, as a partial-scope pact granting preferential access for specified products, with ongoing negotiations in 2025 to expand coverage including Suriname and Haiti.[76][77]

- The CARICOM-Cuba Trade and Economic Cooperation Agreement, signed July 5, 2000, and effective January 1, 2001, providing reciprocal preferences for MDCs and non-reciprocal access for LDCs, focused on goods alongside technical cooperation.[78]

- The CARICOM-Venezuela Trade and Investment Agreement, signed October 1992 and effective January 1, 1993, as a one-way preferential arrangement granting CARICOM exports duty-free entry to Venezuela for listed goods, amid Venezuela's suspended CARICOM membership since 2017.[79]

Intra-Regional Trade Data and Economic Performance Metrics

Intra-regional trade within the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) constitutes a modest portion of members' overall external trade, reflecting limited economic interdependence despite integration initiatives like the Caribbean Single Market and Economy (CSME). In 2021, the total value of intra-CARICOM goods trade stood at approximately $1.6 billion, representing 11.8% of the bloc's total exports.[82] This share has shown stagnation or slight decline in recent years, with analyses citing persistent non-tariff barriers, disparate production capacities, and small domestic markets as contributing factors to subdued volumes.[83] Sector-specific metrics underscore uneven progress; for instance, intra-regional agricultural and food trade accounted for only 16.6% of total regional food imports as of 2017 data, with limited diversification in exports beyond staples like rice and poultry from Guyana and Jamaica.[84] Overall, CARICOM's intra-trade lags behind comparator blocs, such as the European Union (over 60% intra-share) or even Latin America and the Caribbean (around 14% in 2023), highlighting structural constraints like transport costs and regulatory harmonization gaps.[85] Economic performance metrics for CARICOM members reveal variable growth trajectories influenced minimally by intra-regional flows, given their low contribution to aggregate GDP. Regional real GDP growth averaged 3.6% in recent post-pandemic years, supported more by tourism rebound and remittances than internal trade dynamics.[86] Trade balances remain skewed toward extra-regional partners, with the United States absorbing about 30% of exports and supplying over 50% of imports in 2024, exacerbating vulnerabilities to global commodity price fluctuations and external demand shifts.[87]| Year | Intra-Regional Trade Value (USD) | Share of Total Exports (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 1,602,231,564 | 11.8 |