Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

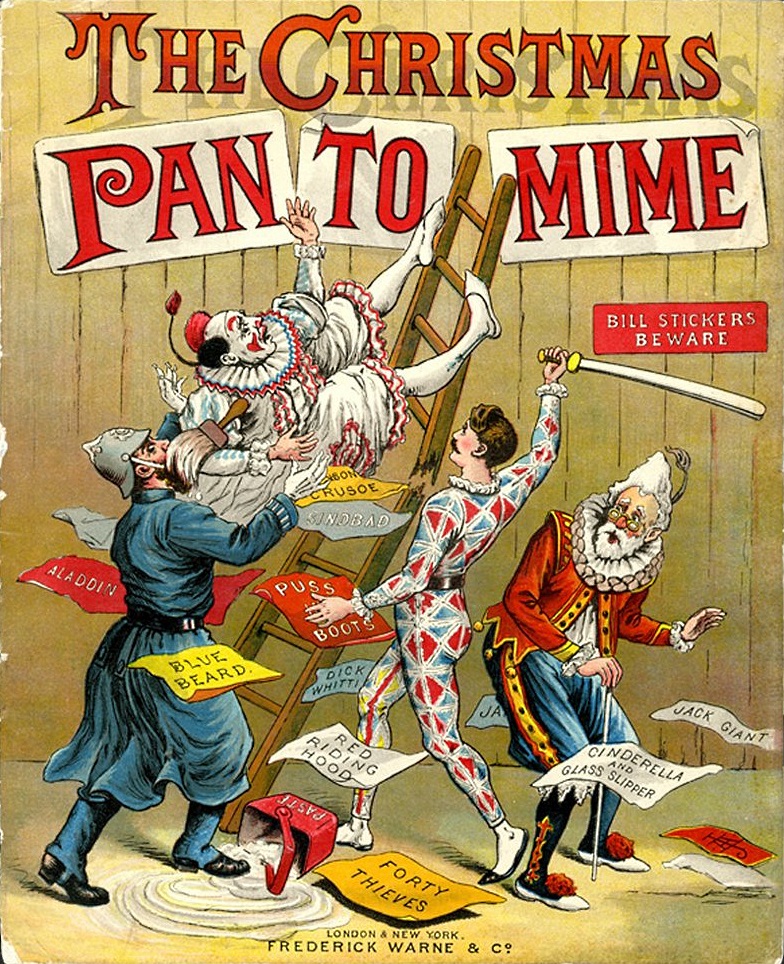

Pantomime

View on WikipediaThis article has an unclear citation style. (June 2023) |

Pantomime (/ˈpæntəˌmaɪm/;[1] informally panto)[2] is a type of musical comedy stage production designed for family entertainment, generally combining broad and topical humour and cross-dressing actors with a story more or less based on a well-known fairy tale, fable or folk tale.[3][4] Pantomime is a participatory form of theatre developed in England in the 18th century in which the audience is encouraged and expected to sing along with certain parts of the music and to shout out phrases to the performers.

The origins of pantomime reach back to ancient Greek classical theatre. It developed partly from the 16th century commedia dell'arte tradition of Italy and partly from other European and British stage traditions, such as 17th-century masques and music hall.[3] An important part of the pantomime, until the late 19th century, was the harlequinade.[5] Modern pantomime is performed throughout the United Kingdom, Ireland and (to a lesser extent) in other English-speaking countries, especially during the Christmas and New Year season, and includes songs, gags, slapstick comedy and dancing.

Outside the British Isles, the word "pantomime" is often understood to mean miming, rather than the theatrical form described here.[1]

History

[edit]Ancient Rome

[edit]

The word pantomime was adopted from the Latin word pantomimus,[6] which in turn derives from the Greek word παντόμιμος (pantomimos), consisting of παντο- (panto-) meaning "all", and μῖμος (mimos), meaning a dancer who acted all the roles or all the story.[7][8][9] The Roman pantomime drew upon the Greek tragedy and other Greek genres from its inception, although the art was instituted in Ancient Rome and little is known of it in pre-Roman Greece.[10][11] The English word came to be applied to the performance itself.[citation needed] According to a lost oration by Aelius Aristides, the pantomime was known for its erotic content and the effeminacy of its dancing;[12] Aristides's work was responded to by Libanius, in his oration "On Behalf of the Dancers", written probably around 361 AD.[citation needed]

Roman pantomime was a production, usually based upon myth or legend, for a solo male dancer—clad in a long silk tunic and a short mantle (pallium) that was often used as a "prop"—accompanied by a sung libretto (called the fabula saltica or "dance-story") rendered by a singer or chorus (though Lucian states that originally the pantomime himself was the singer).[13] Music was supplied by flute and the pulse of an iron-shod shoe called a scabellum. Performances might be in a private household, with minimal personnel, or else lavish theatrical productions involving a large orchestra and chorus and sometimes an ancillary actor. The dancer danced all the roles, relying on masks, stock poses and gestures and a hand-language (cheironomy) so complex and expressive that the pantomime's hands were commonly compared to an eloquent mouth.[14] Pantomime differed from mime by its more artistic nature and relative lack of farce and coarse humour,[8] though these were not absent from some productions.[citation needed]

Roman pantomime was immensely popular from the end of the first century BC until the end of the sixth century AD,[14] a form of entertainment that spread throughout the empire where, because of its wordless nature, it did more than any other art to foster knowledge of the myths and Roman legends that formed its subject-matter – tales such as those of the love of Venus and Mars and of Dido and Aeneas – while in Italy its chief exponents were celebrities, often the protegés of influential citizens, whose followers wore badges proclaiming their allegiance and engaged in street-fights with rival groups, while its accompanying songs became widely known.[failed verification] Yet, because of the limits imposed upon Roman citizens' dance, the populism of its song-texts and other factors, the art was as much despised as adored,[14] and its practitioners were usually slaves or freedmen.[citation needed]

Because of the low status and the disappearance of its libretti, the Roman pantomime received little modern scholarly attention until the late 20th century, despite its great influence upon Roman culture as perceived in Roman art, in statues of famous dancers, graffiti, objects and literature.[7] After the renaissance of classical culture, Roman pantomime was a decisive influence upon modern European concert dance, helping to transform ballet from a mere entertainment, a display of technical virtuosity, into the dramatic ballet d'action. It became an antecedent which, through writers and ballet-masters of the 17th and 18th centuries such as Claude-François Ménestrier (1631–1705), John Weaver (1673–1760), Jean-Georges Noverre (1727–1810) and Gasparo Angiolini (1731–1803), earned it respectability and attested to the capability of dance to render complex stories and express human emotion.[14]

Development in Britain

[edit]In the Middle Ages, the Mummers Play was a traditional English folk play, based loosely on the Saint George and the Dragon legend, usually performed during Christmas gatherings, which contained the origin of many of the archetypal elements of the pantomime, such as stage fights, coarse humour and fantastic creatures,[15] gender role reversal, and good defeating evil.[16] Precursors of pantomime also included the masque, which grew in pomp and spectacle from the 15th to the 17th centuries.[3][17]

Commedia dell'arte and early English adaptation

[edit]

The development of English pantomime was also strongly influenced by the continental commedia dell'arte, a form of popular theatre that arose in Italy in the Early Modern Period. This was a "comedy of professional artists" travelling from province to province in Italy and then France, who improvised and told comic stories that held lessons for the crowd, changing the main character depending on where they were performing. Each "scenario" used some of the same stock characters. These included the innamorati (young lovers); the vecchi (old men) such as Pantalone; and zanni (servants) such as Arlecchino, Colombina, Scaramouche and Pierrot.[3][18][19] Italian masque performances in the 17th century sometimes included the Harlequin character.[20]

In the 17th century, adaptations of the commedia characters became familiar in English entertainments.[21] From these, the standard English harlequinade developed, depicting the eloping lovers Harlequin and Columbine, pursued by the girl's father Pantaloon and his comic servants Clown and Pierrot.[21][22] In English versions, by the 18th century, Harlequin became the central figure and romantic lead.[23] The basic plot of the harlequinade remained essentially the same for more than 150 years, except that a bumbling policeman was added to the chase.[21]

In the first two decades of the 18th century, two rival London theatres, Lincoln's Inn Fields Theatre and the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane (the patent theatres) presented productions that began seriously with classical stories that contained elements of opera and ballet and ended with a comic "night scene". Tavern Bilkers, by John Weaver, the dancing master at Drury Lane, is cited as the first pantomime produced on the English stage.[24] This production was not a success, and Weaver waited until 1716 to produce his next pantomimes, including The Loves of Mars and Venus – a new Entertainment in Dancing after the manner of the Antient Pantomimes.[18] The same year he produced a pantomime on the subject of Perseus and Andromeda. After this, pantomime was regular feature at Drury Lane.[25] In 1717 at Lincoln's Inn, actor and manager John Rich introduced Harlequin into the theatres' pantomimes under the name of "Lun" (for "lunatic").[26][27] He gained great popularity for his pantomimes, especially beginning with his 1724 production of The Necromancer; or, History of Dr. Faustus.[28]

These early pantomimes were silent, or "dumb show", performances consisting of only dancing and gestures. Spoken drama was allowed in London only in the two (later three) patent theatres until Parliament changed this restriction in 1843.[29] A large number of French performers played in London following the suppression of unlicensed theatres in Paris.[18] Although this constraint was only temporary, English pantomimes remained primarily visual for some decades before dialogue was introduced. An 18th-century author wrote of David Garrick: "He formed a kind of harlequinade, very different from that which is seen at the Opéra-Comique in Paris, where harlequin and all the characters speak."[30] The majority of these early pantomimes were re-tellings of a story from ancient Greek or Roman literature, with a break between the two acts during which the harlequinade's zany comic business was performed. The theatre historian David Mayer explains the use of the "batte" or slapstick and the transformation scene that led to the harlequinade:

Rich gave his Harlequin the power to create stage magic in league with offstage craftsmen who operated trick scenery. Armed with a magic sword or bat (actually a slapstick), Rich's Harlequin treated his weapon as a wand, striking the scenery to sustain the illusion of changing the setting from one locale to another. Objects, too, were transformed by Harlequin's magic bat.[18]

Pantomime gradually became more topical and comic, often involving spectacular and elaborate theatrical effects as far as possible. Colley Cibber, David Garrick and others competed with Rich and produced their own pantomimes, and pantomime continued to grow in popularity.[31]

1806–1836

[edit]By the early 1800s, the pantomime's classical stories were often supplanted by stories adapted from European fairy tales, fables, folk tales, classic English literature or nursery rhymes.[18][32] Also, the harlequinade grew in importance until it often was the longest and most important part of the entertainment. Pantomimes usually had dual titles that gave an often humorous idea of both the pantomime story and the harlequinade. "Harlequin and ________", or "Harlequin _______; or, the ________". In the second case, harlequin was used as an adjective, followed by words that described the pantomime "opening", for example: Harlequin Cock Robin and Jenny Wren; or, Fortunatus and the Water of Life, the Three Bears, the Three Gifts, the Three Wishes, and the Little Man who Woo'd the Little Maid. Harlequin was the first word (or the first word after the "or") because Harlequin was initially the most important character. The titles continued to include the word Harlequin even after the first decade of the 1800s, when Joseph Grimaldi came to dominate London pantomime and made the character, Clown, a colourful agent of chaos, as important in the entertainment as Harlequin. At the same time, Harlequin began to be portrayed in a more romantic and stylised way.[33]

Grimaldi's performances elevated the role by "acute observation upon the foibles and absurdities of society, and his happy talent of holding them up to ridicule. He is the finest practical satyrist [sic] that ever existed. ... He was so extravagantly natural, that the most saturnine looker-on acknowledged his sway; and neither the wise, the proud, or the fair, the young nor the old, were ashamed to laugh till tears coursed down their cheeks at Joe and his comicalities."[34] Grimaldi's performances were important in expanding the importance of the harlequinade until it dominated the pantomime entertainment.[35]

By the 1800s, therefore, children went to the theatre around the Christmas and New Year holiday (and often at Easter or other times) primarily to witness the craziness of the harlequinade chase scene. It was the most exciting part of the "panto", because it was fast-paced and included spectacular scenic magic as well as slapstick comedy, dancing and acrobatics. The presence of slapstick in this part of the show evolved from the characters found in Italian commedia dell'arte.[18] The plot of the harlequinade was relatively simple; the star-crossed lovers, Harlequin and Columbine, run away from Columbine's foolish father, Pantaloon, who is being slowed down in his pursuit of them by his servant, Clown, and by a bumbling policeman. After the time of Grimaldi, Clown became the principal schemer trying to thwart the lovers, and Pantaloon was merely his assistant.[35]

The opening "fairy story" was often blended with a story about a love triangle: a "cross-grained" old father who owns a business and whose pretty daughter is pursued by two suitors. The one she loves is poor but worthy, while the father prefers the other, a wealthy fop. Another character is a servant in the father's establishment. Just as the daughter is to be forcibly wed to the fop, or just as she was about to elope with her lover, the good fairy arrives.[34] This was followed by what was often the most spectacular part of the production, the magical transformation scene.[36] In early pantomimes, Harlequin possessed magical powers that he used to help himself and his love interest escape. He would tap his wooden sword (a derivative of the Commedia dell'arte slapstick or "batte") on the floor or scenery to make a grand transition of the world around him take place. The scene would switch from being inside some house or castle to, generally speaking, the streets of the town with storefronts as the backdrop. The transformation sequence was presided over by a Fairy Queen or Fairy Godmother character.[18] The good fairy magically transformed the leads from the opening fairy story into their new identities as the harlequinade characters. Following is an example of the speech that the fairy would give during this transformation:

Lovers stand forth. With you we shall begin.

You will be fair Columbine – you Harlequin.

King Jamie there, the bonnie Scottish loon,

Will be a famous cheild for Pantaloon.

Though Guy Fawkes now is saved from rocks and axe,

I think he should pay the powder-tax.

His guyish plots blown up – nay, do not frown;

You've always been a guy – now be a Clown.[36]

This passage is from a pantomime adaptation of the Guy Fawkes story. The fairy creates the characters of the harlequinade in the most typical fashion of simply telling the characters what they will change into. The principal male and female characters from the beginning plotline, often both played by young women,[29] became the lovers Columbine and Harlequin, the mother or father of Columbine became Pantaloon, and the servant or other comic character became Clown. They would transition into the new characters as the scenery around them changed and would proceed in the "zany fun" section of the performance.[36] From the time of Grimaldi, Clown would see the transformed setting and cry: "Here We Are Again!"[35] The harlequinade began with various chase scenes, in which Harlequin and Columbine manage to escape from the clutches of Clown and Pantaloon, despite the acrobatic leaps of the former through windows, atop ladders, often because of well-meaning but misguided actions of the policeman. Eventually, there was a "dark scene", such as a cave or forest, in which the lovers were caught, and Harlequin's magic wand was seized from his grasp by Clown, who would flourish it in triumph. The good fairy would then reappear, and once the father agreed to the marriage of the young lovers, she would transport the whole company to a grand final scene.[34]

1837 to the end of the harlequinade

[edit]Despite its visible decline by 1836, the pantomime still fought to stay alive.[37] After 1843, when theatres other than the original patent theatres were permitted to perform spoken dialogue, the importance of the silent harlequinade began to decrease, while the importance of the fairy-tale part of the pantomime increased.[32] Two writers who helped to elevate the importance and popularity of the fairy-tale portion of the pantomime were James Planché and Henry James Byron. They emphasized puns and humorous word play, a tradition that continues in pantomime today.[32] As manager of Drury Lane in the 1870s, Augustus Harris produced and co-wrote a series of extraordinarily popular pantomimes, focusing on the spectacle of the productions, that pushed this transition by emphasizing comic business in the pantomime opening and grand processionals.[38] By the end of the 19th century, the harlequinade had become merely a brief epilogue to the pantomime, dwindling into a brief display of dancing and acrobatics.[39] It lingered for a few decades longer but finally disappeared, although a few of its comic elements had been incorporated into the pantomime stories.[23] The last harlequinade was played at the Lyceum Theatre in 1939.[40] Well-known pantomime artists of this era included William Payne,[41] his sons, the Payne Brothers,[42] Vesta Tilley, Dan Leno, Herbert Campbell, Little Tich,[38] Clarice Mayne, Dorothy Ward[43] and Cullen and Carthy.[44]

Modern traditions and conventions

[edit]Traditionally performed around Christmas with family audiences, British pantomime continues as a popular form of theatre, incorporating song, dance, buffoonery, slapstick, cross-dressing, in-jokes, topical references, audience participation, and mild sexual innuendo.[45] Scottish comedian Craig Ferguson, in his 2020 memoir, summarizes contemporary pantomime as classic folklore and fairy tales loosely retold in a slapstick theatrical comedy-musical, writing: "Think Mamma Mia! featuring the Three Stooges but with everyone's back catalogue, not just ABBA's", and furthermore including audience participation reminiscent of showings of the film The Rocky Horror Picture Show.[46]

Stories

[edit]

Pantomime story lines and scripts usually make no direct reference to Christmas and are almost always based on traditional children's stories, particularly the fairy tales of Charles Perrault, Joseph Jacobs, Hans Christian Andersen and the Grimm Brothers. Some of the most popular pantomime stories include Cinderella, Aladdin, Dick Whittington and His Cat and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,[5] as well as Jack and the Beanstalk, Peter Pan, Puss in Boots and Sleeping Beauty.[47] Other traditional stories include Mother Goose, Beauty and the Beast, Robinson Crusoe, The Wizard of Oz, Babes in the Wood (combined with elements of Robin Hood), Little Red Riding Hood, Goldilocks and the Three Bears, Sinbad, St. George and the Dragon, Bluebeard, The Little Mermaid and Thumbelina.[27][48] Prior to about 1870, many other stories were made into pantomimes.[32][49]

While the familiarity of the audience with the original children's story is generally assumed, plot lines are almost always adapted for comic or satirical effect, and characters and situations from other stories are often interpolated into the plot. For instance "panto" versions of Aladdin may include elements from Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves or other Arabian Nights tales; while Jack and the Beanstalk might include references to nursery rhymes and other children's stories involving characters called "Jack", such as Jack and Jill. Certain familiar scenes tend to recur, regardless of plot relevance, and highly unlikely resolution of the plot is common. Straight retellings of the original stories are rare.[50]

Performance conventions

[edit]The form has a number of conventions, some of which have changed or weakened a little over the years, and by no means all of which are obligatory. Some of these conventions were once common to other genres of popular theatre such as melodrama.[51]

- The leading male juvenile character (the principal boy) is traditionally played by a young woman in male garments (such as breeches). Her romantic partner is usually the principal girl, a female ingénue.

- An older woman (the pantomime dame – often the hero's mother) is usually played by a man in drag.[52]

- Risqué double entendre, often wringing innuendo out of perfectly innocent phrases. This is not intended to be understood by children in the audience and is for the entertainment of the adults.

- Audience participation, including calls of "He's behind you!" (or "Look behind you!"), and "Oh, yes it is!" and "Oh, no it isn't!" The audience is always encouraged to hiss or jeer at the villain and "awwwww" the poor victims, such as the rejected dame, who is usually enamoured with one of the male characters.[53]

- Music may be original but is more likely to combine well-known tunes with re-written lyrics. At least one "audience participation" song is traditional: one half of the audience may be challenged to sing "their" chorus louder than the other half. Children in the audience may even be invited on stage to sing along with members of the cast at the end of the performance.

- The animal, played by an actor in "animal skin" or animal costume. It is often a pantomime horse or cow (though could even be a camel if appropriate to the setting), played by two actors in a single costume, one as the head and front legs, the other as the body and back legs.

- The good fairy enters from stage right (left from the audience's perspective) and the villain enters from stage left (right from the audience's perspective). This convention goes back to the medieval mystery plays, where the right side of the stage symbolised Heaven and the left side symbolised Hell.

- A slapstick comedy routine (slosh scene) may be performed, often a decorating or baking scene, with humour based on throwing messy substances. Until the 20th century, British pantomimes often concluded with a harlequinade, a free-standing entertainment of slapstick. Since then, the slapstick has been incorporated into the main body of the show.

- In the 19th century, until the 1880s, pantomimes typically included a transformation scene in which a Fairy Queen magically transformed the pantomime characters into the characters of the harlequinade, who then performed the harlequinade.[39][52]

- The Chorus, who can be considered extras on-stage, and often appear in multiple scenes (but as different characters) and who perform a variety of songs and dances throughout the show. Because of their multiple roles, they may have as much stage-time as the lead characters themselves.

- At some point during the performance, characters including the Dame and the comic will sit on a bench and sing a cheerful song to forget their fears. The thing they fear, often a ghost, appears behind them, but at first the characters ignore the audience's warnings of danger. The characters soon circle the bench, followed by the ghost, as the audience cries "It's behind you!" One by one, the characters see the ghost and run off, until at last the Dame and the ghost come face to face, whereupon the ghost, frightened by the visage of the Dame, runs away.[53]

Guest stars

[edit]Another pantomime tradition is to engage celebrity guest stars, a practice that dates back to the late 19th century, when Augustus Harris was proprietor of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, and hired well-known variety artists for his pantomimes. Contemporary pantomime productions are often adapted to allow the star to showcase their well-known act, even when such a spot has little relation to the pantomime's plot. Critic Michael Billington has argued that if the star enters into the spirit of the entertainment, he or she likely adds to its overall effect, while if it becomes a "showcase for a star" who "stands outside the action", the celebrity's presence likely detracts, notwithstanding the marketing advantage that the star brings to the piece.[54] Billington said that Ian McKellen in a 2004 Aladdin "lets down his hair and lifts up his skirt to reveal a nifty pair of legs and an appetite for double entendre: when told by decorators that 'your front porch could do with a good lick', McKellen adopts a suitable look of mock-outrage. ... At least we can tell our grandchildren that we saw McKellen's Twankey and it was huge."[54]

Roles

[edit]Major

[edit]The main roles within pantomime are usually as follows:[55]

| Role | Role description | Played by |

|---|---|---|

| Principal boy | Main character in the pantomime, a hero or charismatic rogue | Traditionally a young woman in men's clothing |

| Panto dame | Normally the hero's mother | Traditionally a middle-aged man in drag |

| Principal girl | Normally the hero's love interest | Young woman |

| Comic lead | Does physical comedy and relates to children in the audience. Is usually paired with the Dame as a comedy double act, and is frequently the Dame's "son". | Man or woman |

| Benevolent magical being | A fairy, genie or good spirit who helps the hero to defeat the villain, usually through magical means. | Man or woman |

| Villain | The pantomime antagonist. Often a wicked wizard, witch or demon. | Man or woman |

Minor

[edit]| Role | Role description | Played by |

|---|---|---|

| Patriarch | Traditionally the father (occasionally the mother) of the principal girl: often a high status character such as a King, Queen, Emperor, Sultan or Baron, although they can also be involved in comedy routines with the Dame and the Comic. | Man or Woman |

| Animals, etc. | e.g. Jack's cow | "Pantomime horse" or puppet(s) |

| Chorus | Members often have several minor roles | |

| Dancers | Usually a group of young boys and girls |

Venues

[edit]

Pantomime is performed in the United Kingdom, Ireland, Switzerland, Australasia, Canada, Jamaica, South Africa, Malta and Andorra, among other places. It is performed mostly during the Christmas and New Year season.[56][57]

United Kingdom and Ireland

[edit]Many theatres in cities and towns throughout the United Kingdom and Ireland continue to present an annual professional pantomime. Pantomime is also popular with amateur dramatics societies throughout the UK and Ireland, and during the pantomime season (roughly speaking, late November to February) productions are staged in many village halls and similar venues across the country.

Kitty Gurnos-Davies states in her doctoral dissertation that pantomime is responsible for 20% of all live performances in the UK in any one year.[58] The 2018–2019 season saw pantomime performances generating over £60m for the first time in recorded British history.[59]

Andorra

[edit]It was first produced more than a decade ago in Andorra by the English-speaking Mums' group, from the British expatriate community, in the Teatre de les Fontetes in the parish of La Massana. Now it is produced by English and English-speaking international volunteers as part of the Advent celebrations supported by the Comú de La Massana,[60] the local businesses[61] and the Club International d'Andorra[62] to raise money for the less privileged children of Andorra.[63]

Australia

[edit]

Pantomimes in Australia at Christmas were once very popular, but the genre has declined greatly since the middle of the 20th century. Several later professional productions did not recover their costs.[64]

Canada

[edit]Christmas pantomimes are performed yearly at the Hudson Village Theatre in Quebec.[65] Since 1996, Ross Petty Productions has staged pantomimes at Toronto's Elgin Theatre each Christmas season.[66] Pantomimes imported from England were produced at the Royal Alexandra Theatre in the 1980s.[67][68] The White Rock Players Club in White Rock, BC have presented an annual pantomime in the Christmas season since 1954.[69] The Royal Canadian Theatre Company produces pantomimes in British Columbia, written by Ellie King.[70] Since 2013, Theatre Replacement has been producing East Van Panto in partnership with The Cultch in Vancouver.[71][72]

Jamaica

[edit]The National Pantomime of Jamaica was started in 1941 by educators Henry Fowler and Greta Fowler, pioneers of the Little Theatre Movement in Jamaica. Among the first players was Louise Bennett-Coverley. Other notable players have included Oliver Samuels, Charles Hyatt, Willard White, Rita Marley and Dawn Penn. The annual pantomime opens on Boxing Day at the Little Theatre in Kingston and is strongly influenced by aspects of Jamaican culture, folklore and history.[73][74]

Malta

[edit]Pantomime was imported to Malta in the British colonial era for a British expatriate audience and, in the early 20th century, adapted by Maltese producers for Maltese audiences.[75] While in many former territories of the British empire pantomime declined in popularity after independence, as it was seen as a symbol of colonial rule, the genre remains strong in Malta.[76]

Switzerland

[edit]Pantomime was brought to Switzerland by British immigrants and is performed regularly in Geneva since 1972 and Basel since 1994, in a hangar at Basel Airport. The Geneva Amateur Operatic Society has performed pantomimes annually since 1972.[77] Since 2009, the Basel English Panto Group[78] has performed at the Scala Basel each December.[79]

United Arab Emirates

[edit]Annual pantomimes have been running at Christmas in the UAE (and elsewhere in the GCC) since 2007.[80] They are mainly performed by Dubai Panto[81] (a trade name of h2 Productions.ae[82]) in conjunction with Outside the Box Events LLC.[83] They have increased to three pantomimes at Christmas since 2021: two in Dubai and one in Abu Dhabi.[84][85][86] One of the locations for Dubai pantomimes is at the theatre on the Queen Elizabeth 2 cruise ship.[87] The other is in the theatre at the Erth Hotel, Abu Dhabi (formerly the Armed Forces Officers Club and Hotel).[88]

United States

[edit]

Pantomime as performed in Britain was seldom seen in the United States until recent decades. As a consequence, Americans commonly understand the word "pantomime" to refer to the art of mime as it is practised by mime artists.[1]

According to Russell A. Peck of the University of Rochester, the earliest pantomime productions in the US were Cinderella pantomime productions in New York in March 1808, New York again in August 1808, Philadelphia in 1824, and Baltimore in 1839.[89] A production at Olympic Theatre in New York of Humpty Dumpty ran for at least 943 performances between 1868 and 1873,[90] (one source says 1,200 performances),[5] becoming the longest-running pantomime in history.[5]

In 1993, there was a production of Cinderella at the UCLA Freud Theatre, starring Zsa Zsa Gabor.[91] Since 2004, People's Light and Theatre Company, in Malvern, Pennsylvania, has been presenting an annual Christmas pantomime season.[92] Stages Repertory Theatre in Houston, Texas, has been performing original pantomime-style musicals during the Christmas holidays since 2008.[93] Lythgoe Family Productions has produced Christmas pantomimes since 2010 in California.[94]

See also

[edit]- ITV Panto

- Victorian burlesque

- Weihnachtsmärchen (Christmas fairy tale)

- Purim spiel

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c "pantomime". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ Lawner, p. 16.

- ^ a b c d Reid-Walsh, Jacqueline. "Pantomime", The Oxford Encyclopedia of Children's Literature, Jack Zipes (ed.), Oxford University Press (2006), ISBN 9780195146561

- ^ Mayer (1969), p. 6.

- ^ a b c d "The History of Pantomime", It's-Behind-You.com, 2002, accessed 10 February 2013

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary s.v. pantomime

- ^ a b Hall, p. 3.

- ^ a b Pantomimus, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Liddell, Henry George and Robert Scott. παντόμιμος, A Greek–English Lexicon, Perseus Digital Library, accessed 16 November 2013

- ^ Lincoln Kirstein, Dance, Dance Horizons Incorporated, New York, 1969, pp. 40–42, 48

- ^ Broadbent, pp. 21–34.

- ^ Mesk, J., Des Aelius Aristides Rede gegen die Tänzer, WS 30 (1908)

- ^ Quoted in Lincoln Kirstein, Dance, Dance Horizons Incorporated, New York, 1969, p. 50.

- ^ a b c d Alessandra Zanobi. Ancient Pantomime and its Reception, Oxford University Archive of Performances of Greek and Roman Drama

- ^ Barrow, Mandy. "Mummers' Plays", Project Britain, 2013, accessed 21 April 2016.

- ^ Barrow, Mandy. "Christmas Pantomimes", Project Britain, 2013, accessed 21 April 2016

- ^ Burden, Michael. "The English Pantomime Masque" Archived 2016-04-26 at the Wayback Machine, Abstract of symposium paper for French and English Pantomime (2007), University of Oxford, accessed 21 April 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g Mayer, David. "Pantomime, British", Oxford Encyclopedia of Theatre and Performance, Oxford University Press, 2003, accessed 21 October 2011 (subscription required)

- ^ Broadbent, chapter 12.

- ^ Broadbent, chapter 10.

- ^ a b c "Early pantomime", Victoria and Albert Museum, accessed 21 October 2011

- ^ Smith, p. 228

- ^ a b Hartnoll, Phyllis and Peter Found (eds). "Harlequinade", The Concise Oxford Companion to the Theatre, Oxford Reference Online, Oxford University Press, 1996, accessed 21 October 2011. (subscription required)

- ^ Broadbent, chapter 14. Broadbent spends the first half of his book tracing the ancient and European origins of pantomime.

- ^ Broadbent, chapter 14.

- ^ Dircks, Phyllis T. "Rich, John (1692–1761)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edition, May 2011, accessed 21 October 2011

- ^ a b Chaffee and Crick, p. 278

- ^ Broadbent, chapter 15.

- ^ a b Haill, Catherine. Pantomime Archived 2011-11-08 at the Wayback Machine, University of East London, accessed 17 January 2012

- ^ Davies, Thomas. Memoirs of the life of David Garrick, New edition, 1780, I. x. 129, quoted in the Oxford English Dictionary.

- ^ Broadbent, chapters 14 and 15.

- ^ a b c d "The Origin of Popular Pantomime Stories", Victoria and Albert Museum, accessed January 8, 2016.

- ^ McConnell Stott, pp. 95–100.

- ^ a b c Broadbent, chapter 16

- ^ a b c Moody, Jane. "Grimaldi, Joseph (1778–1837)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edition, January 2008, accessed 21 October 2011.

- ^ a b c Wilson, p.?.

- ^ Mayer, p. 309.

- ^ a b Mayer, p. 324

- ^ a b Crowther, Andrew. "Clown and Harlequin", W. S. Gilbert Society Journal, vol. 3, issue 23, Summer 2008, pp. 710–12.

- ^ The Development of Pantomime, Its-Behind-You.com, accessed 3 January 2014

- ^ Boase, G. C. Payne, William Henry Schofield (1803–1878)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edition, May 2007, accessed 22 October 2011

- ^ The Olio, 4 September 1871, p. 41, quoted in Rees, p. 16

- ^ W. MacQueen-Pope, The Melodies Linger On: The Story of Music Hall, London: W. H. Allen (1950), p. 340

- ^ "Gleams from the spotlight". Sporting Chronicle. 27 September 1916. p. 1.

- ^ Christopher, David (2002). "British Culture: An Introduction", p. 74, Routledge; and "It's Behind You", The Economist, 20 December 2014

- ^ Ferguson, Craig (2020). Riding the Elephant: A Memoir of Altercations, Humiliations, Hallucinations, and Observations, New York, Penguin, pp. 89–91, ISBN 9780525533924

- ^ Bowie-Sell, Daisy (17 December 2010). "Top ten pantomimes for Christmas". The Telegraph. The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 22 December 2010. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ^ Broadbent, chapter 19

- ^ Jeffrey Richards (2015). The Golden Age of Pantomime: Slapstick, Spectacle and Subversion in Victorian England. I.B. Tauris. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-78076-293-7.

- ^ Origins of Panto Stories, Limelight scripts, retrieved 2018-08-19

- ^ Smith, p. 200

- ^ a b Serck, Linda. "Oh yes it is: Why pantomime is such a British affair", BBC News, 3 January 2016

- ^ a b Taylor, Millie. "Audience Participation, Community and Ritual", British Pantomime Performance, p. 130, Intellect Books, 2007. ISBN 1841501743. Another bench scene is described in the same source at pp. 44–45.

- ^ a b Billington, Michael. "Aladdin: Old Vic, London", The Guardian, 20 December 2004. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- ^ Lipton, Martina. "Localism and Modern British Pantomime", A World of Popular Entertainments, Gillian Arrighi and Victor Emeljanow (eds.), Cambridge Scholars Publishing (2012) ISBN 1443838047 p. 56.

- ^ Roberts, Chris. Heavy Words Lightly Thrown: The Reason Behind Rhyme, Thorndike Press, 2006 (ISBN 0786285176)

- ^ Smith, p. 287.

- ^ Gurnos-Davies, Katherine (2021). Objects and agents: women, materiality, and the making of contemporary theatre, Doctoral dissertation, University of Oxford, p. 71. Retrieved 9 November 2023

- ^ Carpani, Jessica (2019-12-23). "Panto ticket sales gross over £60m for the first time, as millennials head to the theatre with parents". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 2023-11-09.

- ^ https://www.lamassana.ad/butlletins_web/AD400_desembre_2018/AF%20butlleti%20AD400%20baixa.pdf [dead link]

- ^ "English Language School la Massana".

- ^ "Pantomime – Theatre Group – International Club of Andorra". 23 September 2010.

- ^ "Servei Especialitzat d'Atenció a la Infància i l'Adolescència (SEAIA)".

- ^ Blake, Elissa (24 June 2014). "British pantomime ready to take Sydney by storm". Sydney Morning Herald.

- ^ "Cinderella". Archived from the original on 22 December 2013. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- ^ Flowers, Ellen; Pim, Gordon (September 2013). "Ontario's theatrical heritage in the spotlight" (PDF). Heritage Matters. Ontario Heritage Trust. p. 6.

- ^ "Mum's not the word with theatre genie's pantomimes"[dead link], National Post, accessed 24 November 2014.

- ^ "Goldilocks and the Three Bears, Royal Alexandra Theatre, Toronto"], Its-behind-you.com, accessed 24 November 2014.

- ^ Past Productions" Archived 2014-12-21 at the Wayback Machine, White Rock Players' Club, retrieved 26 April 2018.

- ^ Alexandra, Kristi. "Sleeping Beauty brings King's panto history to Surrey", Surrey Now, 18 December 2014. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- ^ "EAST VAN PANTO | Theatre Replacement". theatrereplacement.org. Retrieved 2020-12-27.

- ^ "How a Vancouver theatre company turned a small holiday panto into one of the city's hottest tickets | CBC Radio". CBC. Retrieved 2020-12-27.

- ^ "History", Little Theatre Movement, 2004, accessed 24 December 2013

- ^ Heap, Brian. "Theatre: National Pantomime", Skywritings, No. 90, pp. 64–66, December 1993, accessed 24 December 2013.

- ^ "The true home of panto". Timesofmalta.com. 23 December 2019. Retrieved 21 December 2024.

- ^ Spiteri, Stephanie. "The history and development of Pantomime in Malta", Masters Thesis, University of Malta, 2014

- ^ "Past Shows", Geneva Amateur Operatic Society. Retrieved 17 August 2024

- ^ "Basel English Panto Group", accessed 24 August 2019

- ^ Baumhofer, Emma. "Taking centre stage: English live shows" Archived 2019-08-24 at the Wayback Machine, Hello Switzerland, 11 May 2015

- ^ "Family Theatre Shows in Dubai". Time Out Dubai. 7 September 2021. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ "The Dubai Pantomime". www.dubaipanto.com. Retrieved 2022-07-11.

- ^ "H2 Productions Middle East". www.h2productions.ae. Retrieved 2022-07-11.

- ^ "Events Company | Outside The Box Events". otbe. Retrieved 2022-07-11.

- ^ "Christmas 2019 Family Fun Watching A Pantomime". Time Out Dubai. 29 October 2019. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ "A Family Friendly Pantomime is Coming to Dubai for Christmas". Time Out Dubai. 27 October 2020. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ Buckridge, Miles (2 November 2021). "All The Christmas Shows Coming to this Abu Dhabi Theatre". What's On Abu Dhabi.

- ^ "QE2.com". 11 July 2022. See also "Theatre by QE2 | Dubai". Theatre by QE2 v2. Retrieved 2022-07-11.

- ^ "Erth Abu Dhabi". Theatre By Erth. Retrieved 2022-07-11.

- ^ Peck, Russell A. Pantomime, Burlesque, and Children's Drama Archived 2011-02-26 at the Wayback Machine, Lib.rochester.edu, accessed 10 June 2010.

- ^ Broadbent, p. 215.

- ^ "Zsa Zsa Gabor in Panto Cinderella". Los Angeles Times. 14 December 1993.

- ^ Cantell, Mary. "People’s Light & Theatre presents 10th Holiday Panto – Cinderella: A Musical Panto", Montgomery News, November 15, 2013

- ^ "Stages' Panto Mother Goose". broadwayworld.com. 27 November 2012. Retrieved 26 April 2018.; "Preview: Panto Cinderella is a British Tradition". Houston Chronicle. 8 December 2008. Retrieved 26 April 2018.; "Panto Bring Texas Laughs to British Genre". Houston Chronicle. 9 November 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2018.; "Panto Mine: A New Holiday Tradition Takes Hold in Houston". CultureMap. 10 December 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- ^ "Lythgoe Family Productions Presents CINDERELLA, 11/27-12/19". broadwayworld.com. 28 September 2010.; "Panto Baby: A Snow White Christmas opens Nov. 30th". British Weekly. 26 November 2011. Retrieved 26 April 2018.; "Theater review: Cinderella Christmas at the El Portal". Los Angeles Times. 23 December 2011. Retrieved 26 April 2018.; "A Snow White Christmas puts Southern California imprint on British theater tradition". Los Angeles Times. 11 December 2012. Retrieved 26 April 2018.; and "Pasadena Playhouse Mike Stoller and wife gave crucial $1 million". Los Angeles Times. 23 January 2013. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

Sources

[edit]- Broadbent, R.J. (1901). A History of Pantomime. London: Simpkin Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co., Ltd.

- Chaffee, Judith and Olly Crick, The Routledge Companion to Commedia dell'Arte (Routledge, 2015) ISBN 978-0-415-74506-2

- Hall, E. and R. Wyles, eds., New Directions in Ancient Pantomime (Oxford, 2008).

- Lawner, Lynne (1998). Harlequin on the Moon. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

- Mayer, David III (1969). Harlequin in His Element: The English Pantomime, 1806–1836. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-37275-1.

- McConnell Stott, Andrew (2009). The Pantomime Life of Joseph Grimaldi. Edinburgh: Canongate Books. ISBN 978-1-84767-295-7.

- Richards, Jeffrey. The Golden Age of Pantomime: Slapstick, Spectacle and Subversion in Victorian England (I. B. Tauris, 2014). ISBN 1780762933

- Smith, Winifred (1964). The Commedia dell'Arte. New York: Benjamin Blom.

- Wilson, A. E. (1949). The Story of Pantomime. London: Home & Van Thal.

External links

[edit]- MusicalTalk Podcast – discussing British pantomime, its origins and traditions.

- Geneva Amateur Operatic Society

- Pantomime Shows in UK. Archived 2009-11-26 at the Wayback Machine.

- The Secret Pantomime Society

- Theatre Britain

- Madrid Players

- Panto in Wales seen through American eyes

- "Pantomime" (Archived 2011-11-08 at the Wayback Machine) by Catherine Haill, V & A

- "The Rise and Fall of the Pantomime Harlequinade"