Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Sinbad the Sailor

View on Wikipedia

Sinbad the Sailor (/ˈsɪnbæd/; Arabic: سندباد البحري, romanized: Sindibādu l-Bahriyy lit. 'Sindibād of the Sea') is a fictional mariner and the hero of a story-cycle. He is described as hailing from Baghdad during the early Abbasid Caliphate (8th and 9th centuries CE.). In the course of seven voyages throughout the seas east of Africa and south of Asia, he has fantastic adventures in magical realms, encountering monsters and witnessing supernatural phenomena.

Origins and sources

[edit]The tales of Sinbad are a relatively late addition to the One Thousand and One Nights. They do not feature in the earliest 14th-century manuscript, and they appear as an independent cycle in 18th- and 19th-century collections. The tale reflects the trend within the Abbasid realm of Arab and Muslim sailors exploring the world. The stories display the folk and themes present in works of that time. The Abbasid reign was known as a period of great economic and social growth. Arab and Muslim traders would seek new trading routes and people to trade with. This process of growth is reflected in the Sinbad tales. The Sinbad stories take on a variety of different themes. Later sources include Abbasid works such as the "Wonders of the Created World", reflecting the experiences of 13th century Arab mariners who braved the Indian Ocean.[1]

The Sinbad cycle is set in the reign of the Abbasid Caliph Harun al-Rashid (786–809). The Sinbad tales are included in the first European translation of the Nights, Antoine Galland's Les mille et une nuits, contes arabes traduits en français, an English edition of which appeared in 1711 as The new Arabian winter nights entertainments[2] and went through numerous editions throughout the 18th century.

The earliest separate publication of the Sinbad tales in English found in the British Library is an adaptation as The Adventures of Houran Banow, etc. (Taken from the Arabian Nights, being the third and fourth voyages of Sinbad the Sailor.),[3] around 1770. An early US edition, The seven voyages of Sinbad the sailor. And The story of Aladdin; or, The wonderful lamp, was published in Philadelphia in 1794.[4] Numerous popular editions followed in the early 19th century, including a chapbook edition by Thomas Tegg. Its best known full translation was perhaps as tale 120 in Volume 6 of Sir Richard Burton's 1885 translation of The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night.[5][6][7]

Tales

[edit]Sinbad the Porter and Sinbad the Sailor

[edit]Like the 1001 Nights, the Sinbad story-cycle has a frame story which goes as follows: in the days of Harun al-Rashid, Caliph of Baghdad, a poor porter (one who carries goods for others in the market and throughout the city) pauses to rest on a bench outside the gate of a rich merchant's house, where he complains to God about the injustice of a world which allows the rich to live in ease while he must toil and yet remain poor. The owner of the house hears and sends for the porter, finding that they are both named Sinbad. The rich Sinbad tells the poor Sinbad that he became wealthy "by Fortune and Fate" in the course of seven wondrous voyages, which he then proceeds to relate.

First Voyage

[edit]After dissipating the wealth left to him by his father, Sinbad goes to sea to repair his fortune. He sets ashore on what appears to be an island, but this island proves to be a gigantic sleeping whale on which trees have taken root ever since the whale was young. Awakened by a fire kindled by the sailors, the whale dives into the depths, the ship departs without Sinbad, and Sinbad is only saved by a passing wooden trough sent by the grace of God. He is washed ashore on a densely wooded island. While exploring the deserted island, he comes across one of the king's grooms. When Sinbad helps save the king's mare from being drowned by a sea horse (not a seahorse, but a supernatural horse that lives underwater), the groom brings Sinbad to the king. The king befriends Sinbad, and he rises in the king's favor and becomes a trusted courtier. One day, the very ship on which Sinbad set sail docks at the island, and he reclaims his goods (still in the ship's hold). Sinbad gives the king his goods and in return the king gives him rich presents. Sinbad sells these presents for a great profit. Sinbad returns to Baghdad, where he resumes a life of ease and pleasure. With the ending of the tale, Sinbad the sailor makes Sinbad the porter a gift of a hundred gold pieces and bids him return the next day to hear more about his adventures.

Second Voyage

[edit]

On the second day of Sinbad's tale-telling (but the 549th night of Scheherazade's), Sinbad the sailor tells how he grew restless of his life of leisure, and set to sea again, "possessed with the thought of traveling about the world of men and seeing their cities and islands." Accidentally abandoned by his shipmates again, he finds himself stranded in an island which contains roc eggs. He attaches himself with the help of his turban to a roc and is transported to a valley of giant snakes which can swallow elephants; these serve as the rocs' natural prey. The floor of the valley is carpeted with diamonds, and merchants harvest these by throwing huge chunks of meat into the valley: the birds carry the meat back to their nests, and the men drive the birds away and collect the diamonds stuck to the meat. The wily Sinbad straps one of the pieces of meat to his back and is carried back to the nest along with a large sack full of precious gems. Rescued from the nest by the merchants, he returns to Baghdad with a fortune in diamonds, seeing many marvels along the way.

Third Voyage

[edit]

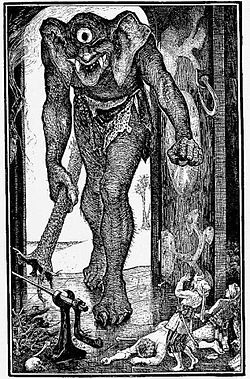

Sinbad sets sail again from Basra. But by ill chance, he and his companions are cast up on an island where they are captured by a "huge creature in the likeness of a man, black of colour, ... with eyes like coals of fire and large canine teeth like boar's tusks and a vast big gape like the mouth of a well. Moreover, he had long loose lips like camel's, hanging down upon his breast, and ears like two Jarms falling over his shoulder-blades, and the nails of his hands were like the claws of a lion." This monster begins eating the crew, beginning with the Reis (captain), who is the fattest. (Burton notes that the giant "is distinctly Polyphemus".)

Sinbad hatches a plan to blind the beast with the two red-hot iron spits with which the monster has been roasting the ship's company. He and the remaining men escape on a raft they constructed the day before. However, the giant's mate hits most of the escaping men with rocks and they are killed. After further adventures (including a gigantic python from which Sinbad escapes using his quick wits), he returns to Baghdad, wealthier than ever.

Fourth Voyage

[edit]Impelled by restlessness, Sinbad takes to the seas again and, as usual, is shipwrecked. The naked savages amongst whom he finds himself feed his companions a herb which robs them of their reason (Burton theorises that this might be bhang), prior to fattening them for the table. Sinbad realises what is happening and refuses to eat the madness-inducing plant. When the cannibals lose interest in him, he escapes. A party of itinerant pepper-gatherers transports him to their own island, where their king befriends him and gives him a beautiful and wealthy wife.

Too late Sinbad learns of a peculiar custom of the land: on the death of one marriage partner, the other is buried alive with his or her spouse, both in their finest clothes and most costly jewels. Sinbad's wife falls ill and dies soon after, leaving Sinbad trapped in a cavern, a communal tomb, with a jug of water and seven pieces of bread. Just as these meagre supplies are almost exhausted, another couple—the husband dead, the wife alive—are dropped into the cavern. Sinbad bludgeons the wife to death and takes her rations.

Such episodes continue; soon he has a sizable store of bread and water, as well as the gold and gems from the corpses, but is still unable to escape, until one day a wild animal shows him a passage to the outside, high above the sea. From here, a passing ship rescues him and carries him back to Baghdad, where he gives alms to the poor and resumes his life of pleasure.

Burton's footnote comments: "This tale is evidently taken from the escape of Aristomenes the Messenian from the pit into which he had been thrown, a fox being his guide. The Arabs in an early day were eager students of Greek literature." Similarly, the first half of the voyage resembles the Circe episode in The Odyssey, with certain differences: while a plant robs Sinbad's men of their reason in the Arab tales, it is Circe's magic which "fattened" Odysseus' men in The Odyssey. It is in an earlier episode, featuring the 'Lotus Eaters', that Odysseus' men are fed a similar magical fruit which robs them of their senses.

Fifth Voyage

[edit]

"When I had been a while on shore after my fourth voyage; and when, in my comfort and pleasures and merry-makings and in my rejoicing over my large gains and profits, I had forgotten all I had endured of perils and sufferings, the carnal man was again seized with the longing to travel and to see foreign countries and islands." Soon at sea once more, while passing a desert island Sinbad's crew spots a gigantic egg that Sinbad recognizes as belonging to a roc. Out of curiosity, the ship's passengers disembark to view the egg. They end up breaking it and have the chick inside as a meal. Sinbad immediately recognizes the folly of their behaviour and orders all back aboard ship. However, the infuriated parent rocs soon catch up with the vessel and destroy it by dropping giant boulders they have carried in their talons.[8]

Shipwrecked yet again, Sinbad is enslaved by the Old Man of the Sea, who rides on his shoulders with his legs twisted round Sinbad's neck and will not let go, riding him both day and night until Sinbad would welcome death. (Burton's footnote discusses possible origins for the old man—the orang-utan, the Greek god Triton—and favours the African custom of riding on slaves in this way).[9]

Eventually, Sinbad makes wine and tricks the Old Man into drinking some. Sinbad kills him after he drunkenly falls off. A ship carries him to the City of the Apes, a place whose inhabitants spend each night in boats off-shore, while their town is abandoned to man-eating apes. Yet through the apes, Sinbad recoups his fortune and eventually finds a ship which takes him home once more to Baghdad.

Sixth Voyage

[edit]

"My soul yearned for travel and traffic". Sinbad is shipwrecked yet again, this time quite violently as his ship is dashed to pieces on tall cliffs. There is no food to be had anywhere, and Sinbad's companions die of starvation until only he is left. He builds a raft and discovers a river running out of a cavern beneath the cliffs. The stream proves to be filled with precious stones and it becomes apparent that the island's streams flow with ambergris. He falls asleep as he journeys through the darkness and awakens in the city of the king of Serendib (Sri Lanka/Ceylon), "diamonds are in its rivers and pearls are in its valleys". The king marvels at what Sinbad tells him of the great Haroun al-Rashid, and asks that he take a present back to Baghdad on his behalf, a cup carved from a single ruby, with other gifts including a bed made from the skin of the serpent that swallowed an elephant[a] ("And whoso sitteth upon it never sickeneth"), and "A hundred thousand miskals of Sindh lign-aloesa.", and a slave-girl "like a shining moon". Sinbad returns to Baghdad, where the Caliph wonders greatly at the reports Sinbad gives of Serendib.

Seventh and Last Voyage

[edit]

The ever-restless Sinbad sets sail once more, with the usual result. Cast up on a desolate shore, he constructs a raft and floats down a nearby river to a great city. Here the chief of the merchants gives Sinbad his daughter in marriage, names him his heir, and conveniently dies. The inhabitants of this city are transformed once a month into birds, and Sinbad has one of the bird-people carry him to the uppermost reaches of the sky, where he hears the angels glorifying God, "whereat I wondered and exclaimed, 'Praised be God! Extolled be the perfection of God!'". But no sooner are the words out than there comes fire from heaven which all but consumes the bird-men. The bird-people are angry with Sinbad and set him down on a mountain-top, where he meets two youths, servants of God who give him a golden staff; returning to the city, Sinbad learns from his wife that the bird-men are devils, although she and her father were not of their number. And so, at his wife's suggestion, Sinbad sells all his possessions and returns with her to Baghdad, where at last he resolves to live quietly in the enjoyment of his wealth, and to seek no more adventures.

Burton includes a variant of the seventh tale, in which Haroun al-Rashid asks Sinbad to carry a return gift to the king of Serendib. Sinbad replies, "By Allah the Omnipotent, Oh my lord, I have taken a loathing to wayfare, and when I hear the words 'Voyage' or 'Travel,' my limbs tremble". He then tells the Caliph of his misfortune-filled voyages; Haroun agrees that with such a history "thou dost only right never even to talk of travel". Nevertheless, at the Caliph's command, Sinbad sets forth on this, his uniquely diplomatic voyage. The king of Serendib is well pleased with the Caliph's gifts (which include, among other things, the food tray of King Solomon) and showers Sinbad with his favour. On the return voyage, the usual catastrophe strikes: Sinbad is captured and sold into slavery. His master sets him to shooting elephants with a bow and arrow, which he does until the king of the elephants carries him off to the elephants' graveyard. Sinbad's master is so pleased with the huge quantities of ivory in the graveyard that he sets Sinbad free, and Sinbad returns to Baghdad, rich with ivory and gold. "Here I went in to the Caliph and, after saluting him and kissing hands, informed him of all that had befallen me; whereupon he rejoiced in my safety and thanked Almighty Allah; and he made my story be written in letters of gold. I then entered my house and met my family and brethren: and such is the end of the history that happened to me during my seven voyages. Praise be to Allah, the One, the Creator, the Maker of all things in Heaven and Earth!".

Some versions return to the frame story, in which Sinbad the Porter may receive a final generous gift from Sinbad the Sailor. In other versions the story cycle ends here, and there is no further mention of Sinbad the Porter.

Adaptations

[edit]Sinbad's quasi-iconic status in Western culture has led to his name being recycled for a wide range of uses in both serious and not-so-serious contexts, frequently with only a tenuous connection to the original tales. Many films, television series, animated cartoons, novels, and video games have been made, most of them featuring Sinbad not as a merchant who stumbles into adventure, but as a dashing dare-devil adventure-seeker.

Films

[edit]English language animated films

[edit]- Sinbad the Sailor (1935) is an animated short film produced and directed by Ub Iwerks.

- Popeye the Sailor Meets Sindbad the Sailor (1936) is a two-reel animated cartoon short subject in the Popeye Color Feature series, produced in Technicolor and released to theatres on 27 November 1936 by Paramount Pictures.[10] It was produced by Max Fleischer for Fleischer Studios, Inc. and directed by Dave Fleischer.

- Sinbad (1992) is an animated film originally released on 18 May 1992 and based on the classic Arabian Nights tale, Sinbad the Sailor, and produced by Golden Films.

- Sinbad: Beyond the Veil of Mists (2000) is the first feature-length computer animation film created exclusively using motion capture.[11] While many animators worked on the project, the human characters were entirely animated using motion capture.

- Sinbad: Legend of the Seven Seas (2003) is an American animated adventure film produced by DreamWorks Animation and distributed by DreamWorks Pictures. The film uses traditional animation and computer animation. It was directed by Tim Johnson.

Non-English language animated films

[edit]- Arabian naito: Shindobaddo no bôken (Arabian Nights: Adventures of Sinbad) (1962) (animated Japanese film).

- A Thousand and One Nights (1969) Story created by Osamu Tezuka, combination of other One Thousand and One Nights stories and the legends of Sinbad.

- Pohádky Tisíce a Jedné Noci (Tales of 1,001 Nights) (1974), a seven-part animated film in Czech by Karel Zeman.

- Doraemon: Nobita's Dorabian Nights[12] (1991).

- Sinbad (film trilogy) (2015–2016) is a series of Japanese animated family adventure films produced by Nippon Animation and Shirogumi.

- The Adventures of Sinbad (2013) is an Indian 2D animated film directed by Shinjan Neogi and Abhishek Panchal, and produced by Afzal Ahmed Khan.[13]

- Sinbad: Pirates of Seven Storm (2016) A Russian animated film by CTB Film Company.

Live-action English language films

[edit]- Arabian Nights is a 1942 adventure film directed by John Rawlins and starring Sabu, Maria Montez, Jon Hall and Leif Erickson. The film is derived from The Book of One Thousand and One Nights but owes more to the imagination of Universal Pictures than the original Arabian stories. Unlike other films in the genre (The Thief of Bagdad), it features no monsters or supernatural elements.[14]

- Sinbad the Sailor (1947) is a 1947 American Technicolor fantasy film directed by Richard Wallace and starring Douglas Fairbanks Jr., Maureen O'Hara, Walter Slezak, and Anthony Quinn. It tells the tale of the "eighth" voyage of Sinbad, wherein he discovers the lost treasure of Alexander the Great.

- Son of Sinbad (1955) is a 1955 American adventure film directed by Ted Tetzlaff. It takes place in the Middle East and consists of a wide variety of characters including over 127 women.

- The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958) is a 1958 Technicolor heroic fantasy adventure film directed by Nathan H. Juran and starring Kerwin Mathews, Torin Thatcher, Kathryn Grant, Richard Eyer, and Alec Mango. It was distributed by Columbia Pictures and produced by Charles H. Schneer.[15]

- Captain Sindbad (1963) is a 1963 independently made fantasy and adventure film, produced by Frank King and Herman King (King Brothers Productions), directed by Byron Haskin, that stars Guy Williams and Heidi Brühl. The film was shot at the Bavaria Film studios in Germany and was distributed by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.[16]

- The Golden Voyage of Sinbad (1973) a fantasy film directed by Gordon Hessler and featuring stop motion effects by Ray Harryhausen. It is the second of three Sinbad films released by Columbia Pictures.

- Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger (1977) is a fantasy film directed by Sam Wanamaker and featuring stop motion effects by Ray Harryhausen. The film stars Patrick Wayne, Taryn Power, Margaret Whiting, Jane Seymour, and Patrick Troughton. It is the third and final Sinbad film released by Columbia Pictures.

Live-action English language direct-to-video films

[edit]- Sinbad: The Battle of the Dark Knights (1998) – DTV film about a young boy that must go back in time to help Sinbad.

- The 7 Adventures of Sinbad (2010) is an American adventure film directed by Adam Silver and Ben Hayflick. As a mockbuster distributed by The Asylum, it attempts to capitalise on Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time and Clash of the Titans.[17]

- Sinbad and The Minotaur (2011) starring Manu Bennett is a 2011 Australian fantasy B movie directed by Karl Zwicky serving as an unofficial sequel to the 1947 Douglas Fairbanks Jr. film and Harryhausen's Sinbad trilogy.[18] It combines Arabian Nights hero Sinbad the Sailor with the Greek legend of the Minotaur.[19]

- Sinbad: The Fifth Voyage (2014) starring Shahin Sean Solimon, low-budget film.

- Sinbad and the War of the Furies (2016) An American action film starring John Hennigan, direct-to-streaming.

Live-action non-English language films

[edit]- Sinbad Khalashi, or Sinbad the Sailor is a 1930 Indian silent action-adventure film by Ramchandra Gopal Torney.[20]

- Sinbad Jahazi, or Sinbad the Sailor, is a 1952 Indian Hindi-language adventure film by Nanabhai Bhatt.[20]

- Sindbad ki Beti, or Daughter of Sindbad, is a 1958 Indian Hindi-language fantasy film by Ratilal. It follows the daughter of Sindbad as she goes out in search for her missing father.[20]

- Son of Sinbad is a 1958 Indian Hindi-language film by Nanabhai Bhatt. A sequel to Sinbad Jahazi, it follows the adventures of the son of Sinbad in high seas.[20]

- Sinbad contro i sette saraceni (Sinbad against the Seven Saracens). (Italian: Sindbad contro i sette saraceni, also known as Sinbad Against the 7 Saracens) is a 1964 Italian adventure film written and directed by Emimmo Salvi and starring Gordon Mitchell.[21][22] The film was released straight to television in the United States by American International Television in 1965.

- Sindbad Alibaba and Aladdin is a 1965 Indian Hindi-language fantasy-adventure musical film by Prem Narayan Arora. It starred Pradeep Kumar in the role of Sindbad.[20]

- Şehzade Sinbad (Prince Sinbad), alternately known as Şehzade Sinbad Kaf Dağı'nda (Prince Sinbad at the Mount Qaf) (1971) (Turkish film).

- Simbad e il califfo di Bagdad (Sinbad and the Caliph of Baghdad) (1973) (Italian film).

- Sinbad of the Seven Seas (1989) is a 1989 Italian fantasy film produced and directed by Enzo G. Castellari from a story by Luigi Cozzi, revolving around the adventures of Sinbad the Sailor. Sinbad must recover five magical stones to free the city of Basra from the evil spell cast by a wizard, which his journey takes him to mysterious islands and he must battle magical creatures in order to save the world.

Television

[edit]English-language series and films

[edit]- Sinbad Jr. and His Magic Belt (1965)

- The Freedom Force (TV Series) (1978)

- The Adventures of Sinbad (1979) – TV animated film.

- Mystery Science Theater 3000 (1993) episode: The Magic Voyage of Sinbad

- Scooby-Doo! in Arabian Nights (1994) is a television movie featuring a segment telling the tale of Sinbad, with Magilla Gorilla as Sinbad.

- The Fantastic Voyages of Sinbad the Sailor (1996–1998) is an American animated television series based on the Arabian Nights story of Sinbad the Sailor and produced by Fred Wolf Films that aired beginning 2 February 1998 on Cartoon Network.[23]

- The Adventures of Sinbad (1996–98) is a Canadian Action/Adventure Fantasy television series following on the story from the pilot of the same name.

- The Backyardigans (2007) episode: "Sinbad Sails Alone".

- Sinbad (2012) – A UK television series from Sky1.

- Sindbad & The 7 Galaxies (2016 by Sun TV, picked up by Toonavision in 2020) is an animated children's comedy adventure TV series[24] created by Raja Masilamani and IP owned by Creative Media Partners.[25]

Note: Sinbad was mentioned, but did not actually appear, in the Season 3 episode Been There, Done That of Xena Warrior Princess when one of the story's lovers tells Xena that he was hoping that Hercules would have appeared to save his village from its curse.

Non-English language series and films

[edit]- Arabian Nights: Sinbad's Adventures (Arabian Naitsu: Shinbaddo No Bôken, 1975).

- Manga Sekai Mukashi Banashi: The Arabian Nights: Adventures of Sinbad the Sailor (1976) Japanese anime TV series, Directed by Sadao Nozaki and Tatsuya Matano. Producer Yuji Tanno. The origins of this is a series called Manga Hajimete Monogatari This is dubbed in English and narrated by Telly Savalas.

- Alif Laila (1993–1997), an Indian television series based on the One Thousand and One Nights which aired on Doordarshan's DD National. Episodes titled "Sindbad Jahaazi" focus on the adventures of the sailor, where he is portrayed by Shahnawaz Pradhan.[26]

- Princess Dollie Aur Uska Magic Bag (2004–2006), an Indian teen fantasy adventure television series on Star Plus where Vaquar Shaikh portrays Sinbad, one of the main characters in the show along with Ali Baba and Hatim.

- Magi: The Labyrinth of Magic (2012), Magi: The Kingdom of Magic (2013) and Magi: Adventure of Sinbad (2016) are Japanese fantasy adventure manga series.

- Janbaaz Sindbad (2015–2016), an Indian adventure-fantasy television series based on Sinbad the Sailor which aired on Zee TV, starring Harsh Rajput in the titular role.

Note: A pair of foreign films that had nothing to do with the Sinbad character were released in North America, with the hero being referred to as "Sinbad" in the dubbed soundtrack. The 1952 Russian film Sadko (based on Rimsky-Korsakov's opera Sadko) was overdubbed and released in English in 1962 as The Magic Voyage of Sinbad, while the 1963 Japanese film Dai tozoku (whose main character was a heroic pirate named Sukezaemon) was overdubbed and released in English in 1965 as The Lost World of Sinbad.[citation needed]

Video games

[edit]- In 1978, Gottlieb manufacturing released a pinball machine named Sinbad,[27] the artwork featured characters from the movie Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger. Also released, in a shorter run, was an Eye of the Tiger pinball game.[28]

- In 1984, Sinbad was released by Atlantis Software.[29]

- In 1986, Sinbad and the Golden Ship was released by Mastertronic Ltd.[30]

- Another 1986 game called The Legend of Sinbad was released by Superior Software.[31]

- In 1987, Sinbad and the Throne of the Falcon was released by Cinemaware.[32]

- In 1996, the pinball game Tales of the Arabian Nights was released featuring Sinbad.[33] This game (manufactured by Williams Electronics) features Sinbad's battle with the Rocs and the Cyclops as side quests to obtain jewels. The game was adapted into the video game compilation Pinball Hall of Fame: The Williams Collection in 2009.

- In 2007, Sega released the Arabian Nights-themed Sonic and the Secret Rings, in which Knuckles the Echidna took the role of Sinbad.

Music

[edit]- In Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov's suite Scheherazade, the 1st, 2nd, and 4th movements focus on portions of the Sinbad story. Various components of the story have identifiable themes in the work, including rocs and the angry sea. In the climactic final movement, Sinbad's ship (6th voyage) is depicted as rushing rapidly toward cliffs and only the fortuitous discovery of the cavernous stream allows him to escape and make the passage to Serindib.

- The song "Sinbad the Sailor" in the soundtrack of the Indian film Rock On!! focuses on the story of Sinbad the Sailor in music form.

- Sinbad et la légende de Mizan (2013) A French stage musical. the musical comedy event in Lorraine. An original creation based on the history of Sinbad the Navy, heroes of 1001 nights. A quest to traverse the Orient, 30 artists on stage, mysteries, combats, music and enviable dances ... A new adventure for Sinbad, much more dangerous than all the others.

- Sinbad's adventures have appeared on various audio recordings as both readings and dramatizations, including Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves/Sinbad the Sailor (Riverside Records RLP 1451/Golden Wonderland GW 231, played by Denis Quilley), Sinbad the Sailor (Tale Spinners for Children on United Artists Records UAC 11020, played by Derek Hart), Sinbad the Sailor: A Tale from the Arabian Nights (Caedmon Records TC-1245/Fontana Records SFL 14105, read by Anthony Quayle), Sinbad the Sailor /The Adventures of Oliver Twist and Fagin (Columbia Masterworks ML 4072, read by Basil Rathbone), 1001 Nights: Sinbad the Sailor and Other Stories (Naxos Audio 8.555899, narrated by Bernard Cribbins) and The Arabian Nights (The Voyages of Sinbad the Sailor) (Disneyland Records STER-3988).

- "Nagisa no Sinbad" (渚のシンドバッド) was the 4th single released by Pink Lady, a popular Japanese duo in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The song has been covered by former idol group W and by the Japanese super group Morning Musume.

Literature

[edit]- In The Count of Monte Cristo, "Sinbad the Sailor" is but one of many pseudonyms used by Edmond Dantès.

- In his Ulysses, James Joyce uses "Sinbad the Sailor" as an alias for the character of W.B. Murphy and as an analogue to Odysseus. He also puns mercilessly on the name: Jinbad the Jailer, Tinbad the Tailor, Whinbad the Whaler, and so on.

- In Dylan Thomas' play for voices, Under Milk Wood, the barman of the Sailor's Arms pub is named Sinbad Sailors.

- Edgar Allan Poe wrote a tale called "The Thousand-and-Second Tale of Scheherazade". It depicts the 8th and final voyage of Sinbad the Sailor, along with the various mysteries Sinbad and his crew encounter; the anomalies are then described as footnotes to the story.

- Polish poet Bolesław Leśmian's Adventures of Sindbad the Sailor is a set of tales loosely based on the Arabian Nights.

- Hungarian writer Gyula Krúdy's Adventures of Sindbad is a set of short stories based on the Arabian Nights.

- In John Barth's "The Last Voyage of Somebody the Sailor", "Sinbad the Sailor" and his traditional travels frame a series of 'travels' by a 20th-century New Journalist known as 'Somebody the Sailor'.

- Pulitzer Prize winner Steven Millhauser has a story entitled "The Eighth Voyage of Sinbad" in his 1990 collection The Barnum Museum.

Comics

[edit]- "Sinbad the Sailor" (1920) artwork by Paul Klee (Swiss-German artist, 1879–1940).

- In 1950, St. John Publications published a one shot comic called Son of Sinbad.[34]

- In 1958, Dell Comics published a one shot comic based on the film The 7th Voyage of Sinbad.[35]

- In 1963, Gold Key Comics published a one shot comic based on the film Captain Sinbad.[36]

- In 1965, Dell Comics published a 3 issue series called Sinbad Jr.[37]

- In 1965 Gold Key Comics published a 2 issue mini-series called The Fantastic Voyages of Sinbad.[38]

- In 1974 Marvel Comics published a two issue series based on the film The Golden Voyage of Sinbad in Worlds Unknown #7[39] and #8.[40] They then published a one shot comic based on the film The 7th Voyage of Sinbad in 1975 with Marvel Spotlight #25.[41]

- In 1977, the British comic company General Book Distributors, published a one shot comic/magazine based on the film Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger.[42]

- In 1988, Catalan Communications published the one shot graphic novel The Last Voyage of Sinbad written by Jan Strnad and drawn by Richard Corben.[43]

- In 1989 Malibu Comics published a 4 issue mini-series called Sinbad,[44] and followed that up with another 4 issue mini-series called Sinbad Book II: In the House of God In 1991.[45]

- In 2001, Marvel Comics published a one shot comic that teamed Sinbad with the Fantastic Four called Fantastic 4th Voyage of Sinbad.[46]

- In 2007, Bluewater Comics published a 3 issue mini-series called Sinbad: Rogue of Mars.[47]

- In 2008, the Lerner Publishing Group published a graphic novel called Sinbad: Sailing into Peril.[48]

- In 2009, Zenescope Entertainment debuted Sinbad in their Grimm Fairy Tales universe having him appearing as a regular ongoing character. He first appeared in his own 14 issue series called 1001 Arabian Nights: The Adventures of Sinbad.[49] Afterwards he appeared in various issues of the Dream Eater saga,[50] as well as the 2011 Annual,[51] Giant-Size,[52] and Special Edition[53] one-shots.

- In 2012, a graphic novel called Sinbad: The Legacy, published by Campfire Books, was released.[54] He appears in the comic book series Fables written by Bill Willingham, and as the teenaged Alsind in the comic book series Arak, Son of Thunder—which takes place in the 9th century AD—written by Roy Thomas.

- In Alan Moore's The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Black Dossier, Sinbad appears as the Immortal Orlando's lover of thirty years, until he leaves for his 8th Voyage and never returns.

- In The Simpsons comic book series "Get Some Fancy Book Learnin'", Sinbad's adventures are parodied as "Sinbart the Sailor".

- "The Last Voyage of Sinbad" by Richard Corben and Jan Strnad originally appeared as "New Tales of the Arabian Nights" serialized in Heavy Metal magazine, issues #15–28 (1978–79) and was later collected and reprinted as a trade paperback book.

- Sinbad is a major character in the Japanese manga series Magi: The Labyrinth of Magic written and illustrated by Shinobu Ohtaka.

Theme parks

[edit]- Sinbad provides the theme for the dark ride Sinbad's Storybook Voyage at Tokyo DisneySea.

- Sinbad embarks on an adventure to save a trapped princess in the water-based boat ride, The Adventures of Sinbad at Lotte World in Seoul, South Korea.[55]

- The Efteling theme park at Kaatsheuvel in the Netherlands has a land themed after Sinbad called De Wereld van Sindbad (The World of Sinbad). It includes the indoor roller coaster Vogel Rok, themed after Sinbad's fifth voyage, and Sirocco, a teacups ride.

- The elaborate live-action stunt show The Eighth Voyage of Sinbad at the Universal Orlando Resort in Florida featured a story inspired by Sinbad's voyages.

Other references

[edit]- Actor and comedian David Adkins has performed under the stage name Sinbad since the 1980s.

- An LTR retrotransposon from the genome of the human blood fluke, Schistosoma mansoni, is named after Sinbad.[56] It is customary for mobile genetic elements like retrotransposons to be named after mythical, historical, or literary travelers; for example, the well-known mobile genetic elements Gypsy and Mariner.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The theme of a snake swallowing an elephant, originating here, was taken up by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry in The Little Prince.

References

[edit]- ^ Pinault 1998, pp. 721–722.

- ^ The new Arabian winter nights entertainments. Containing one thousand and eleven stories, told by the Sultaness of the Indies, to divert the Sultan from performing a bloody vow he had made to marry a virgin lady every day, and have her beheaded next morning, to avenge himself for the adultery committed by his first Sultaness. The whole containing a better account of the customs, manners, and religions of the Indians, Persians, Turks, Tartarians, Chineses, and other eastern nations, than is to be met with in any English author hitherto set forth. Faithfully translated into English from the Arabick manuscript of Haly Ulugh Shaschin., London: John de Lachieur, 1711.

- ^ The Adventures of Houran Banow, etc. (Taken from the Arabian Nights, being the third and fourth voyages of Sinbad the Sailor.), London: Thornhill and Sheppard, 1770.

- ^ The seven voyages of Sinbad the sailor. And The story of Aladdin; or, The wonderful lamp, Philadelphia: Philadelphia, 1794

- ^ Burton, Richard. "The Book of one thousand & one nights" (translation online). CA: Woll amshram. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ Marzolph, Ulrich; van Leeuwen, Richard (2004), The Arabian nights encyclopedia, vol. 1, pp. 506–8.

- ^ Irwin, Robert (2004), The Arabian nights: a companion.

- ^ JPG image. stefanmart.de

- ^ JPG image. stefanmart.de

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. pp. 122–123. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (2009). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons (3rd ed.). New York: Checkmark Books. p. 226. ISBN 978-0-8160-6600-1.

- ^ "映画ドラえもんオフィシャルサイト_Film History_12". dora-movie.com. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ^ "The Adventures of Sinbad". The Times of India.

- ^ Article on Arabian Nights at Turner Classic Movies accessed 10 January 2014

- ^ Swires, Steve (April 1989). "Nathan Juran: The Fantasy Voyages of Jerry the Giant Killer Part One". Starlog Magazine. No. 141. p. 61.

- ^ "Captain Sinbad (1963) – Byron Haskin | Synopsis, Characteristics, Moods, Themes and Related | AllMovie".

- ^ Dread Central – The Asylum Breeding a Mega Piranha

- ^ Sinbad and the Minotaur on IMDb

- ^ DVD review: Sinbad and the Minotaur

- ^ a b c d e Rajadhyaksha, Ashish; Willemen, Paul (1999). Encyclopaedia of Indian cinema. British Film Institute. ISBN 9780851706696. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- ^ Roberto Poppi, Mario Pecorari (15 May 2024). Dizionario del cinema italiano. I film. Gremese Editore, 2007. ISBN 978-8884405036.

- ^ Paolo Mereghetti (15 May 2024). Il Mereghetti – Dizionario dei film. B.C. Dalai Editore, 2010. ISBN 978-8860736260.

- ^ Erickson, Hal (2005). Television Cartoon Shows: An Illustrated Encyclopedia, 1949 Through 2003 (2nd ed.). McFarland & Co. p. 322. ISBN 978-1-4766-6599-3.

- ^ Milligan, Mercedes (27 January 2016). "'Sindbad & The 7 Galaxies' Launches with Presales". Animation Magazine. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- ^ Dickson, Jeremy (26 January 2019). "Creative Media Partners debuts Sindbad & the 7 Galaxies". KidScreen.

- ^ "Shahnawaz Pradhan who plays Hariz Saeed in 'Phantom' talks about the film's ban in Pakistan". dnaindia.com. 22 August 2015.

- ^ "Gottlieb 'Sinbad'". Internet Pinball Machine Database. IPDb. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Gottlieb 'Eye of the Tiger'". Internet Pinball Machine Database. IPDb. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Sinbad for ZX Spectrum (1984)". MobyGames. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Sinbad & the Golden Ship for ZX Spectrum (1986)". MobyGames. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Lemon – Commodore 64, C64 Games, Reviews & Music!". Lemon64.com. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Sinbad and the Throne of the Falcon – Amiga Game / Games – Download ADF, Review, Cheat, Walkthrough". Lemon Amiga. 23 August 2004. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Internet Pinball Machine Database: Williams 'Tales of the Arabian Nights'". Ipdb.org. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Son of Sinbad". Comics. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "The 7th Voyage Of Sinbad Comic No. 944 – 1958 (Movie)". A Date in Time. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Captain Sinbad". Comics. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Sinbad Jr". Comics. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "The Fantastic Voyages of Sinbad". Comics. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Worlds Unknown No. 7". Comics. 24 August 2006. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Worlds Unknown No. 8". Comics. 24 August 2006. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Marvel Spotlight No. 25". Comics. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "The Comic Book Database". Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "The Last Voyage of Sinbad". Comics. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Sinbad". Comics. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "The Comic Book Database". Comic Book DB. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Fantastic 4th Voyage of Sinbad". Comics. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Sinbad: Rogue of Mars". Comics. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ Comic vine, archived from the original (JPEG) on 12 November 2012.

- ^ "1001 Arabian Nights: The Adventures of Sinbad". Comics. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Grimm Fairy Tales: Dream Eater Saga". Comics. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ^ "Grimm Fairy Tales 2011 Annual". Comics. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ^ "Grimm Fairy Tales Giant-Size 2011". Comics. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ^ "Grimm Fairy Tales 2011 Special Edition". Comics. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ^ "Sinbad: Legend of the Seven Seas". Comic Corner. Camp fire graphic novels. 4 January 2012. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ^ "Lotte World Attractions". The Adventures of Sinbad.

- ^ Copeland, Claudia S.; Mann, Victoria H.; Morales, Maria E.; Kalinna, Bernd H.; Brindley, Paul J. (23 February 2005). "The Sinbad retrotransposon from the genome of the human blood fluke, Schistosoma mansoni, and the distribution of related Pao-like elements". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 5 (1): 20. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-5-20. ISSN 1471-2148. PMC 554778. PMID 15725362.

Sources

[edit]- Haddawy, Husain (1995). The Arabian Nights. Vol. 1. WW Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-31367-3.

- Pinault, D. (1998). "Sindbad". In Meisami, Julie Scott; Starkey, Paul (eds.). Encyclopedia of Arabic Literature. Vol. 2. Taylor & Francis. pp. 721–723. ISBN 9780415185721.

Further reading

[edit]- Beazley, Charles Raymond (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 141–142. This includes a detailed analysis of potential sources and comparable tales across contemporaneous and earlier texts.

- Copeland, CS; Mann, VH; Morales, ME; Kalinna, BH; Brindley, PJ (23 February 2005). "The Sinbad retrotransposon from the genome of the human blood fluke, Schistosoma mansoni, and the distribution of related Pao-like elements". BMC Evol Biol. 5 (1): 20. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-5-20. PMC 554778. PMID 15725362.

- Favorov, OV; Ryder, D (12 March 2004). "Sinbad: a neocortical mechanism for discovering environmental variables and regularities hidden in sensory input". Biol Cybern. 90 (3): 191–202. doi:10.1007/s00422-004-0464-8. PMID 15052482. S2CID 680298.

- Marcelli, A; Burattini, E; Mencuccini, C; Calvani, P; Nucara, A; Lupi, S; Sanchez Del Rio, M (1 May 1998). "Sinbad, a brilliant IR source from the DAPhiNE storage ring". Journal of Synchrotron Radiation. 5 (3). J Synchrotron Radiat: 575–7. Bibcode:1998JSynR...5..575M. doi:10.1107/S0909049598000661. PMID 15263583..

External links

[edit]- Mart, Stefan, Story of Sindbad the Sailor.

- Mart, Stefan (1933), "Sindbad the Sailor: 21 Illustrations by Stefan Mart", Tales of the Nations (illustrations)

Sinbad the Sailor

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Literary History

Sources in One Thousand and One Nights

The tales of Sinbad the Sailor form a distinct cycle of seven voyages embedded within the larger collection known as One Thousand and One Nights, also referred to as the Arabian Nights, a compilation of Middle Eastern folktales that draws from diverse oral and written traditions across regions including Iraq, Iran, Egypt, India, and Central Asia.[1] These stories, featuring the wealthy merchant Sinbad recounting his perilous adventures at sea, were integrated into the anthology as a self-contained narrative sequence, reflecting the broader theme of survival through storytelling prevalent in the collection.[3] The One Thousand and One Nights originated from oral folklore traditions that were gradually committed to writing, with the core compilation emerging during the Abbasid Caliphate in the 8th and 9th centuries, a period marked by cultural flourishing in Baghdad and extensive maritime trade along the Indian Ocean routes.[3] However, the Sinbad cycle itself represents a later addition, likely incorporated during Syrian or Egyptian recensions in the 14th to 15th centuries, as evidenced by surviving manuscripts from that era which postdate the anthology's earliest forms.[4] This timing aligns with the collection's evolution from a 10th-century Arabic base into more expansive versions influenced by regional storytelling practices.[1] In the narrative, the Sinbad tales are specifically positioned as accounts shared by the prosperous Sinbad the Sailor with a humble porter also named Sinbad, unfolding over seven consecutive nights in a Baghdad setting that echoes the frame story of Scheherazade entertaining her husband, the sultan, to postpone her execution.[5] This parallel structure reinforces the anthology's motif of tales-within-tales, where each voyage concludes with Sinbad rewarding the porter, mirroring the life-sustaining rhythm of Scheherazade's nightly narrations.[1] The Sinbad stories gained prominence in Europe through the French translation by Antoine Galland, published in 12 volumes between 1704 and 1717, which drew from a 14th- or 15th-century Syrian manuscript supplemented by oral sources from a Maronite storyteller in Paris.[4] Galland's version, adapted for Western readers by softening explicit elements, popularized the tales across the continent and beyond, with English adaptations following shortly after.[5] Earliest known evidence of the cycle appears in a now-lost Arabic manuscript acquired by Galland around 1701–1704, while a related 15th-century Syrian compilation confirms influences from non-Arabic sources, including Persian and Indian folklore, as seen in character names and motifs traceable to pre-Islamic traditions.[4][3]Manuscripts and Variations

The story of Sinbad the Sailor first appears in the Galland Manuscript, a 14th- or 15th-century Arabic compilation of One Thousand and One Nights originating from Syria and now held at the Bibliothèque nationale de France under call numbers MSS arabes 3609, 3610, and 3611. This three-volume manuscript contains 282 nights and approximately 35 stories, including the full cycle of Sinbad's seven voyages as an independent narrative sequence, and served as the primary source for Antoine Galland's French translation published between 1704 and 1717.[6] Galland, a French orientalist, received the manuscript in 1701 from a Syrian informant in Paris and incorporated Sinbad's tales into volumes 5 through 8 of his 12-volume Les Mille et Une Nuits, marking their introduction to Western audiences and influencing subsequent global adaptations.[4] Later Arabic traditions feature variations in Egyptian recensions, with 15th-century manuscripts and printed editions like the 1835 Bulaq edition from Cairo expanding or altering the cycle's integration into the larger Nights framework.[7] The Bulaq edition, based on earlier Egyptian compilations, includes Sinbad but rearranges voyage details, such as altering the sequence of encounters or omitting minor episodes for brevity.[1] These differences reflect regional scribal practices, with Syrian versions emphasizing fantastical elements and Egyptian ones incorporating more local folklore, leading to inconsistencies in voyage order across manuscripts.[8] Scholarly debates center on Sinbad's authorship and origins, attributing the tales to anonymous folk traditions rather than a single compiler, with roots in pre-Islamic seafaring narratives from Persian and Indian maritime lore.[2] Influences include ancient tales of merchants like those in the Persian Hezar Afsan (precursor to the Nights) and Indo-Persian trade epics, where motifs of perilous voyages echo earlier Zoroastrian and Buddhist seafaring stories predating Islam.[9] No pre-14th-century Arabic manuscripts contain the full Sinbad cycle, suggesting its compilation in the medieval Islamic period from oral sources, though some argue for a unified redactor drawing on 9th-century fragments.[10] In the 19th century, Richard Francis Burton's 1885 English translation, The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night, highlighted textual variations by restoring erotic and violent elements toned down in Galland's edition and earlier Arabic versions for moral reasons. Burton drew from the Bulaq and Calcutta II editions, noting how Syrian manuscripts preserved more vivid details in voyages like the third, involving the giant roc bird.[11] Modern scholarship advanced with Muhsin Mahdi's 1984 critical Arabic edition, published by Brill, which reconstructs the text from the Galland Manuscript as the oldest extant version, establishing a baseline for comparing variants and confirming Sinbad's late addition to the Nights core.[12] Post-2010 digitization efforts have enhanced access through digital archives, including scans of the Galland Manuscript available via the BnF's Gallica platform since around 2012, allowing scholars to analyze paleographic features and marginalia absent in printed editions.[13] Studies from the 2010s and 2020s, such as a 2014 article exploring Persian precursors and a 2024 analysis, further debate Indo-Persian roots by linking Sinbad's motifs—like encounters with serpents and diamond valleys—to 10th-century Indo-Iranian trade tales, suggesting transmission via Muslim mariners in the Indian Ocean.[14][8] These analyses underscore the cycle's evolution from oral folk narratives into a textual staple, with ongoing debates over its non-Arabic symbolic origins.[8]Narrative Structure

Frame Story

The frame story of Sinbad the Sailor is set in Baghdad during the Abbasid Caliphate, a period of cultural and economic flourishing in the Islamic Golden Age under Caliph Harun al-Rashid (r. 786–809 CE).[11] In this narrative framework, a poor porter named Sinbad—distinct from the wealthy sailor of the same name—labors through the city's bustling streets, carrying heavy loads for meager wages. Exhausted, he pauses to rest outside a grand mansion, where the aromas of a lavish feast waft from within, heightening his sense of hardship and inequality. Upon hearing the porter's lament about his impoverished life and the apparent injustice of fate favoring the rich, the opulent homeowner, Sinbad the Sailor—a prosperous merchant—invites the porter inside to join an ongoing banquet with other guests. The sailor, moved by the porter's complaints and the coincidence of their shared name, offers hospitality including food, wine, and rest, before explaining that his wealth stems not from idle fortune but from perilous adventures at sea. To illustrate this, he begins recounting his extraordinary voyages, transforming the evening into a storytelling session.[11] This encounter establishes a poignant contrast between the porter's daily toil and the sailor's adventure-forged riches, subtly introducing themes of destiny and divine providence that underpin the tales.[2] The frame unfolds across multiple banquets, with each of the sailor's seven voyages narrated on a separate night, allowing the porter to return home enriched by gifts—typically 100 sequins per evening—from the sailor's generosity. This cyclical structure mirrors the overarching narrative device of One Thousand and One Nights, where stories delay peril, here fostering camaraderie and moral reflection among the diners. By the conclusion, after the seventh voyage, the porter's fortunes have improved through the sailor's largesse, and he departs with renewed perspective, blessing the sailor for revealing the hidden paths of providence.[11] Manuscript variations affect the frame's details; for instance, in Antoine Galland's influential 18th-century French translation (1704–1717), drawn from a medieval Syrian manuscript and oral Syrian sources, the porter is named Hindbad, and dialogues are extended with more philosophical exchanges on fate, adapting the tale for European sensibilities while preserving the banquet sequence.[11] Later translations based on Egyptian recensions, such as Richard Francis Burton's 1885 English version, retain a more concise frame focused on the porter's immediate envy and the sailor's direct narration, emphasizing the embedded tales' autonomy within the larger collection.[11]Overview of the Seven Voyages

The seven voyages of Sinbad the Sailor follow a sequential structure in which each begins with the protagonist's growing dissatisfaction with his accumulated wealth and sedentary life in Baghdad, prompting him to embark on maritime expeditions that lead to perilous supernatural encounters and conclude with his safe return bearing even greater fortunes.[15] This cyclical pattern of departure, trial, and enrichment repeats across the voyages, embedding them as embedded tales within the larger frame of One Thousand and One Nights, where Sinbad recounts his adventures to a porter over multiple evenings.[1] The narrative progression exhibits an escalation in the nature of perils, starting with encounters dominated by natural disasters in the initial voyage and gradually incorporating more fantastical mythical creatures and profound moral trials in the later ones, ultimately leading to a theme of spiritual enlightenment by the seventh voyage.[2] Common elements unify the series, including recurring motifs of divine providence guiding Sinbad's survival, critiques of human hubris in defying accumulated wisdom from prior journeys, and depictions of exotic locales drawn from historical Indian Ocean trade routes, such as islands and seas evoking real-world commerce between the Arabian Peninsula, India, and Southeast Asia.[8] In terms of placement and length, the Sinbad voyages constitute a substantial segment of One Thousand and One Nights in key editions, spanning approximately 31 nights (from night 536 to 566 in the standard Burton translation) and comprising roughly 3-5% of the overall narrative volume, though this varies with manuscript expansions; they function as a self-contained cycle within the anthology's broader compilation of folk tales.[16] Scholarly analysis debates the unity of the voyages, with some viewing them as a cohesive narrative arc intentionally structured for thematic progression, while others argue they represent separately compiled tales integrated into the collection during its medieval evolution from Persian and Arabic oral traditions.[17][1]The Seven Voyages

First Voyage

Sinbad, a wealthy merchant from Baghdad, inherited a vast fortune from his father but soon squandered it through a life of idle luxury and entertainment. Restless and eager for change, he liquidated his remaining property into merchandise worth several thousand gold pieces and joined a group of merchants departing from Basrah on a ship headed for trading ports along the East African coast and in the Indian Ocean.[18] The voyage progressed favorably until the ship anchored at what the crew mistook for a verdant island, its surface resembling a rocky hillock encrusted with barnacles and seaweed. To prepare a meal, they kindled a fire atop it, but the "island" abruptly shuddered and submerged into the depths, revealing itself to be an enormous fish of whale-like proportions that had lain dormant for ages. Chaos ensued as the ship capsized; most aboard drowned, but Sinbad seized a large wooden tub and floated amid the wreckage until currents carried him to the shore of a nearby uninhabited island. There, exhausted but alive, he sustained himself with fruit from wild trees and spring water while awaiting rescue.[18] Exploring the island, Sinbad discovered a verdant meadow where grooms were tending a herd of mares, part of an ancient custom to lure wild stallions from the sea for breeding. Impressed by his courteous demeanor, the grooms brought him to their ruler, King Mihrjan, in the nearby city. The king, struck by Sinbad's intelligence and bearing, welcomed him as an honored guest, showered him with gifts, and arranged his marriage to the royal daughter, effectively adopting him into the family and appointing him as chief harbor-master. Under the king's patronage, Sinbad thrived, overseeing trade and accumulating substantial wealth through commerce in spices, silks, and other goods.[18] Months later, a merchant vessel arrived in the harbor, and Sinbad recognized it as the same ship from his outbound journey, its captain having presumed him lost at sea. Revealing his identity and displaying the ledger of his original cargo, Sinbad reclaimed his property, augmented it with profits from his new ventures, and loaded the ship with additional riches. With the king's blessing, he set sail for Basrah and thence to Baghdad, where he arrived prosperous beyond his former means. This first adventure established his enduring fortune and served as a cautionary reflection on the unpredictable perils of sea travel contrasted with the relative security of life on land.[18]Second Voyage

After returning from his first voyage with considerable wealth, Sinbad the Sailor, still restless in Baghdad, equipped a ship and set out as captain on his second voyage, accompanied by merchants eager for trade in distant lands. The vessel sailed successfully for some time, trading goods at various ports, until it anchored at a seemingly uninhabited island. There, the crew discovered what appeared to be a massive white dome, which proved to be the egg of the legendary giant roc bird. Despite warnings from Sinbad and the captain against disturbing it, some sailors chipped away at the shell, revealing a young chick inside; they killed and ate it, enraging the parent rocs upon their return. The enormous birds, with wings spanning dozens of feet, retaliated by dropping massive boulders onto the ship, shattering it and casting Sinbad and the survivors into the sea.[19] Clinging to a piece of wreckage, Sinbad drifted until he washed ashore on a rugged coast, where he encountered other merchants who had similarly survived shipwrecks. They explained the peril of the nearby Diamond Valley, a deep chasm inaccessible except by descent, teeming with venomous snakes as thick as beams that emerged at nightfall, but rich with diamonds, emeralds, and other gems scattered like gravel. To harvest these treasures, the merchants described their method: throwing large slabs of raw meat into the valley, where diamonds would stick to the bloodied surfaces; the rocs would then swoop down, snatch the meat in their talons to feed their young, and carry it to their mountain eyries. Inspired by tales of great fortunes made this way, Sinbad resolved to venture into the valley himself. He descended using ropes provided by the merchants, filled his pockets and a leather bag with the finest diamonds while evading the snakes by day, and at night sought shelter under a roc's fallen feather, which served as both protection and a prized souvenir of the roc's immense scale.[19] To escape, Sinbad followed the merchants' technique on a grander scale: he slaughtered a sheep, stuffed its carcass with the largest diamonds, and bound himself tightly inside it. A roc soon seized the bait and bore it aloft to its nest atop the mountain, where the waiting merchants frightened the bird away with shouts and stones, then cut Sinbad free, overjoyed at his safe return and the trove he brought. With his share of the gems, Sinbad rejoined a trading ship bound for Persian and Indian ports, where he sold the diamonds for vast sums in gold and silver, amassing even greater wealth than before. The return journey proved treacherous, as a fierce storm battered the vessel, but it eventually reached Basrah, from where Sinbad traveled overland to Baghdad. There, he settled into luxury, distributing alms generously and reflecting on the voyage's lesson in human ingenuity triumphing over nature's formidable perils. The roc feathers he retained became cherished artifacts, symbols of the voyage's wondrous encounters with mythical avian giants.[19]Third Voyage

After recovering from the hardships of his second voyage and amassing further wealth in Baghdad, Sinbad the Sailor felt an irrepressible urge to travel once more, joining a group of merchants on a ship departing from Basrah bound for the Indian Ocean trade routes. The vessel sailed successfully to several islands, where the crew bartered goods, but a fierce storm soon drove them toward an unknown shore identified in later accounts as near the Mountain of the Zughb. Upon anchoring, they were suddenly assaulted by swarms of ferocious apes—described as locust-like in number—that boarded the ship, severed the anchor ropes with their teeth, and made off with the cargo, stranding the terrified crew on the desolate island.[20] Exploring the island in search of rescue, the survivors discovered a massive, ruined castle haunted by a monstrous ogre, a cannibalistic giant as tall as a palm tree with a single eye and hideously deformed features, who seized them one by one and roasted them alive on iron spits over a blazing fire for his meals. Sinbad and his companions, witnessing the captain's gruesome fate, endured imprisonment in the creature's lair, surviving initially by their wits as the ogre deemed them too meager to eat immediately. In a desperate bid for freedom, they heated the spits in the fire and thrust them into the giant's eye, blinding him and causing him to bellow in agony; the men then fashioned a crude boat from the castle's timbers and fled into the sea. Pursued by a horde of similar rock-hurling ogres on the shore, most of the escapees perished when boulders sank their vessel, but Sinbad alone washed ashore on a nearby island after days adrift.[20] There, Sinbad faced yet another horror: enormous serpents that devoured his two remaining companions, prompting him to construct a protective enclosure of woven branches and thorns to shield himself through the night. Dawn brought salvation in the form of a passing merchant ship, which carried him to the prosperous island of Al-Salahitah, famed for its sandalwood groves and located near the coasts of Serendib (modern Sri Lanka) and Cape Comorin. Grateful for his rescue, the captain returned Sinbad's portion of the original cargo, allowing him to trade profitably in spices like cloves, ginger, and camphor across Hind and Sind, amassing a fortune far exceeding his previous gains. Upon returning to Basrah and then Baghdad, Sinbad distributed alms to the poor and reveled in his enhanced wealth, his third voyage underscoring the relentless physical endurance required to survive encounters with these monstrous humanoids.[20][1]Fourth Voyage

After amassing further wealth from his previous adventures, Sinbad the Sailor, driven by an unquenchable thirst for travel, sets out on his fourth voyage from Basra aboard a merchant vessel bound for distant ports. A violent storm shatters the ship off an unknown coast, drowning most aboard and leaving Sinbad to cling to a piece of wreckage until he washes ashore on a densely wooded island. There, he encounters a tribe of savage cannibals who capture shipwreck survivors, fattening them with a stupefying herb and rice before devouring them; Sinbad narrowly escapes detection by remaining hidden and subsisting on wild fruits.[21] Wandering inland, Sinbad reaches a settlement of pepper-gatherers who speak Arabic and rescue him, taking him to their king in the nearby city. Grateful, Sinbad presents the ruler with a saddle he fashions from local materials—an innovation unknown in the land—and is rewarded with a position as treasurer, allowing him to amass riches through trade. He soon marries a woman of noble birth, but discovers a gruesome local custom: upon the death of one spouse, the survivor is entombed alive with the deceased, provided only meager provisions to hasten their end. When his wife falls ill and dies shortly after, Sinbad is bound and lowered into a vast subterranean cavern filled with corpses, given a jug of water and seven small cakes of bread, sealing his apparent fate.[22] In the oppressive darkness of the tomb, Sinbad's survival instincts awaken a grim resolve; he realizes the cavern serves as a communal grave where multiple living victims are periodically interred. As attendants lower the next unfortunate—another widower or widow—he strikes them dead with a massive bone or stone, seizing their food and water to prolong his life, repeating this macabre act several times until he has gathered sufficient strength and supplies. This episode evokes the uncanny horror of suspended death, underscoring themes of fate's capricious cruelty and human tenacity in defying it.[21] Desperate to escape, Sinbad hears the sound of a wild beast or creature moving in the cavern and follows it through a narrow passage or pre-existing breach in the wall, emerging onto a rocky seashore. The cavern's floor, strewn with the jewels and valuables stripped from the dead, yields a fortune in diamonds, emeralds, and gold that he hauls to the surface. A passing ship spots him and takes him aboard, eventually returning him to Baghdad laden with treasures, which he generously distributes among the needy, including further gifts to Hindbad the porter. This voyage's supernatural undertones of apparent death and revival heighten the escalating otherworldliness of Sinbad's odyssey, blending terror with triumphant rebirth.[22][23]Fifth Voyage

In the fifth voyage, Sinbad, having amassed further wealth from previous expeditions, equips a vessel with a crew of merchants and sets sail from Basra, driven by an insatiable desire for adventure and trade. The ship reaches an island where the crew spots a massive roc egg; despite warnings, some sailors break it open and kill the chick inside. Enraged, the parent rocs attack by dropping huge rocks on the vessel, sinking it and forcing Sinbad to cling to wreckage until he washes ashore on another island.[24] There, Sinbad encounters the Old Man of the Sea, a grotesque, emaciated figure who silently clings to his neck like a parasite, forcing him to carry him about in search of wine. Unable to shake him off, Sinbad finds a gourd of grapes, ferments them into wine, and offers it to the old man, who drinks greedily and falls into a drunken stupor. Seizing the moment, Sinbad strikes him with a rock, killing him and freeing himself. Continuing onward, Sinbad reaches a city where he trades profitably in goods such as cocoa-nuts, pepper, and pearls, amassing significant riches.[24] Rescued by a passing ship, Sinbad returns to Basra and then Baghdad, where he distributes alms and reflects on the voyage's trials. This adventure highlights themes of cunning and endurance against supernatural oppression, with the Old Man of the Sea symbolizing burdensome fate overcome through ingenuity.[2]Sixth Voyage

In his sixth voyage, Sinbad the Sailor, restless despite the comforts of Baghdad following his previous adventures, assembled a crew and set sail from Basra toward uncharted eastern waters, driven by an insatiable curiosity for trade and discovery. As the ship ventured into strange seas, it was inexorably pulled toward a colossal magnetic mountain, a natural lodestone formation of immense power that attracted all iron objects, causing nails and bolts to be wrenched from the hull. The vessel shattered against the sheer cliffs, claiming many lives, but Sinbad survived by hastily constructing a small raft from wood and ropes devoid of metal, allowing him to drift away from the perilous attraction and reach a nearby shore. Washed ashore on a mysterious island, Sinbad encountered marvels of apparent mechanical ingenuity: fountains that operated without human intervention, spouting crystal-clear water in rhythmic patterns as if powered by hidden mechanisms, and flocks of lifelike mechanical birds that perched on trees, their wings fluttering with clockwork precision to mimic flight and song. These wonders belonged to the domain of a wise hermit, an aged scholar who lived in seclusion amid the island's groves, tending to the devices he claimed were gifts from ancient sages versed in the arts of automation and hydraulics. The hermit, recognizing Sinbad's fortitude, shared tales of the island's origins as a haven for inventors exiled from distant empires, emphasizing how such contrivances revealed the boundaries of human ingenuity in replicating nature's designs.[25] Guided by the hermit's knowledge, Sinbad explored further and discovered an underground sea accessed through cavernous tunnels, leading to vast subterranean cities carved from rock and illuminated by phosphorescent minerals, where echoes of long-lost civilizations lingered in abandoned halls. Navigating this hidden realm by coracle, he gathered metallic treasures—rare alloys and engraved maps depicting forgotten routes across impossible terrains—and emerged safely to rejoin civilization. Upon his return to Baghdad laden with these artifacts, Sinbad reflected on the voyage's lessons, underscoring the profound limits of human navigation against the boundless wonders of divine creation, a theme that reinforced his humility before nature's enigmas.[26]Seventh Voyage

Sinbad, having amassed great wealth from his previous voyages and vowed to remain in Baghdad, finds himself unable to resist the call of the sea and embarks on a seventh and final journey, departing from Basrah with a group of merchants bound for trade in distant lands. The ship encounters a fierce storm that drives it into the Sea of the Clime of the King, where enormous sea serpents dwell, capable of swallowing vessels whole; one such serpent rears up, its head like a mountain, filling the crew with terror as they prepare for death.[27] The storm subsides, but the ship wrecks on a reef amid monstrous fish that rise from the depths, their sizes defying belief and threatening to devour the survivors. Sinbad clings to a plank, drifting for days amid moral dilemmas of survival and despair, until he washes ashore on an island. There, he constructs a raft and navigates a river, arriving exhausted at a prosperous city where a virtuous sheikh takes pity on him, offering shelter, food, and eventually his daughter's hand in marriage. Sinbad prospers, inheriting the sheikh's estate upon his death and becoming a respected citizen.[27] The city's inhabitants reveal a monthly ritual: they anoint themselves with a special oil and transform into birds, flying to a sacred mountain to commune with the divine. Eager to join, Sinbad participates, soaring with them toward heaven where he hears the voice of God, but the overwhelming glory strikes him with celestial fire. Divine intervention prevents his fall into the abyss, depositing him safely on a distant mountain peak. Rescued by a local, he aids in slaying a giant serpent guarding hidden treasures with a magical golden rod, earning passage back to the city.[27] After 27 years away—the longest of his voyages in certain manuscripts—Sinbad sells his holdings, sails home to Baghdad, and renounces further sea travel, embracing the acceptance of fate and reflecting on the burdens of his hard-won wealth. He bequeaths riches to the porter Hindbad, concluding his tales and closing the frame narrative with the porter's gratitude.[27]Themes and Interpretations

Recurring Motifs and Symbolism

In the tales of Sinbad the Sailor, the sea emerges as a profound metaphor for the uncertainties of life and the workings of divine will, embodying both peril and transformative potential that tests the protagonist's faith and resilience across his voyages. Scholars interpret the ocean as a chaotic realm where human agency intersects with predestined fate, often invoking Islamic notions of submission to Allah's mercy amid unpredictable trials. For instance, the sea's relentless challenges symbolize the broader human struggle against existential instability, resolved only through divine intervention and personal endurance. Islands, in turn, represent sites of isolation or temptation, functioning as liminal spaces that mirror stages of spiritual and civilizational progression, from primitive isolation to ordered society. These locales underscore themes of temptation overcome by faith, as Sinbad navigates regressive impulses toward enlightenment and return to communal harmony.[2][28] Mythical creatures in the Sinbad narratives serve as potent symbols of hubris, fate, and the enigmatic unknown, embodying forces that challenge human limits without direct narrative recounting. The roc, a colossal bird, symbolizes the vastness and unpredictability of nature's dominion, reminding voyagers of their fragility before cosmic scales and the hubris of unchecked ambition. Serpents and other beasts evoke fateful encounters with the inscrutable, representing existential threats that demand cunning and piety for survival. The Old Man of the Sea, in particular, allegorizes burdensome attachments or the weight of the unfamiliar, illustrating how external forces can ensnare the soul until liberated through wit and divine favor. These elements collectively highlight the tales' exploration of human vulnerability to fate's whims, framed within a spiritual journey of growth.[29][8] Wealth accumulation in the Sinbad stories functions as a double-edged motif, juxtaposing material gain against spiritual depletion and portraying treasures as illusory lures in life's perilous cycle. Jewels and diamonds, often acquired through voyages' hardships, symbolize ephemeral riches that contrast with enduring faith, as seen in motifs where such valuables prove useless in isolation, underscoring their contextual value within society. This duality reflects a critique of avarice, where fortune's pursuit leads to loss and renewal, emphasizing spiritual wealth over temporal hoards in the cyclical pattern of departure and return. The valley of diamonds, for example, embodies this illusion, where abundance traps rather than liberates, highlighting the tales' meditation on fortune's deceptive nature.[15][30] Western interpretations of Sinbad, particularly through Antoine Galland's 18th-century translation, have infused the tales with Orientalist exoticism, framing the East as a realm of wondrous yet primitive otherness that captivated European imaginations. This lens exoticized Sinbad's adventures as emblematic of an enchanting, unchanging Orient, often stripping cultural nuances for romantic allure. Post-2000 postcolonial scholarship reexamines these readings, critiquing how such portrayals reinforced colonial binaries of East versus West, while reclaiming the narratives for hybrid identities and resistance to imperial gazes. Modern analyses highlight Sinbad's voyages as sites of cultural negotiation, challenging Orientalist stereotypes through lenses of globalization and diaspora.[31][32] Recent ecocritical readings of the Sinbad tales, particularly in 2020s scholarship, address underemphasized environmental motifs, portraying the voyages as pre-industrial reflections on human-nature interdependence and ecological displacement. The narratives depict nature's agency through seas, islands, and creatures, illustrating harmonious coexistence disrupted by human intrusion, with motifs of survival underscoring sustainability in resource-scarce settings. These analyses frame Sinbad's encounters as allegories for environmental balance, where exploitation leads to peril, advocating resistance to overreach in favor of respectful engagement with the natural world. Such interpretations reveal the tales' relevance to contemporary ecological concerns, emphasizing interconnectedness over domination.[33][34]Moral and Philosophical Elements

Sinbad's adventures recurrently illustrate the Islamic concept of qadar, or divine predestination, portraying his survivals from perils such as shipwrecks and monstrous encounters as manifestations of Allah's unalterable decree rather than mere luck or personal merit.[35] For instance, after escaping the Valley of Diamonds, Sinbad reflects, "From what Destiny doth write there is neither refuge nor flight," underscoring submission to divine will as a path to endurance.[35] This theme permeates his prayers during trials, invoking Allah for deliverance, as in his plea after being cast ashore: "Allah Almighty quickened me after I was virtually dead."[35] Such invocations highlight an ethical imperative of faith and patience (ṣabr), where human agency bows to predestined outcomes, fostering resilience amid chaos.[36] A central moral critique emerges in Sinbad's restlessness and avarice, which propel each voyage yet invite divine punishment, ultimately advocating contentment and moderation. Driven by "longing… to traffic and to make money by trade," Sinbad repeatedly ventures forth despite prior traumas, only to face losses that strip him of ill-gotten gains, such as plundered jewels.[35] By the seventh voyage, these cycles culminate in his retirement, foreswearing travel for family life, a resolution that promotes ethical restraint over endless ambition.[35] This narrative arc parallels other Arabian Nights tales like Ali Baba's, where greed (ḥirṣ) endangers prosperity, but Sinbad's story uniquely ties it to Islamic ethics of gratitude and charity, as he distributes wealth upon returns.[36] Philosophically, the voyages explore human limits against the vastness of God's creation, infused with Sufi undertones of the journey as a spiritual metaphor for inner purification and divine proximity. Encounters with symbolic creatures like the roc briefly evoke awe at natural wonders, prompting reflection on mortality and trust in providence, akin to Sufi asceticism.[37] More recent analyses interpret Sinbad's returns to Baghdad as existential cycles of alienation and reintegration, embodying 21st-century readings of perpetual striving amid absurdity.[8] In Islamic contexts, hospitality (ḍiyāfa) underscores communal ethics, with Sinbad receiving shelter from kings and captains, reflecting Quranic mandates of generosity to strangers.[38] Gender roles, however, remain conventional, portraying women as supportive wives or passive figures in arranged unions, reinforcing patriarchal norms without challenging them.[35]Adaptations in Film

Animated Films