Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

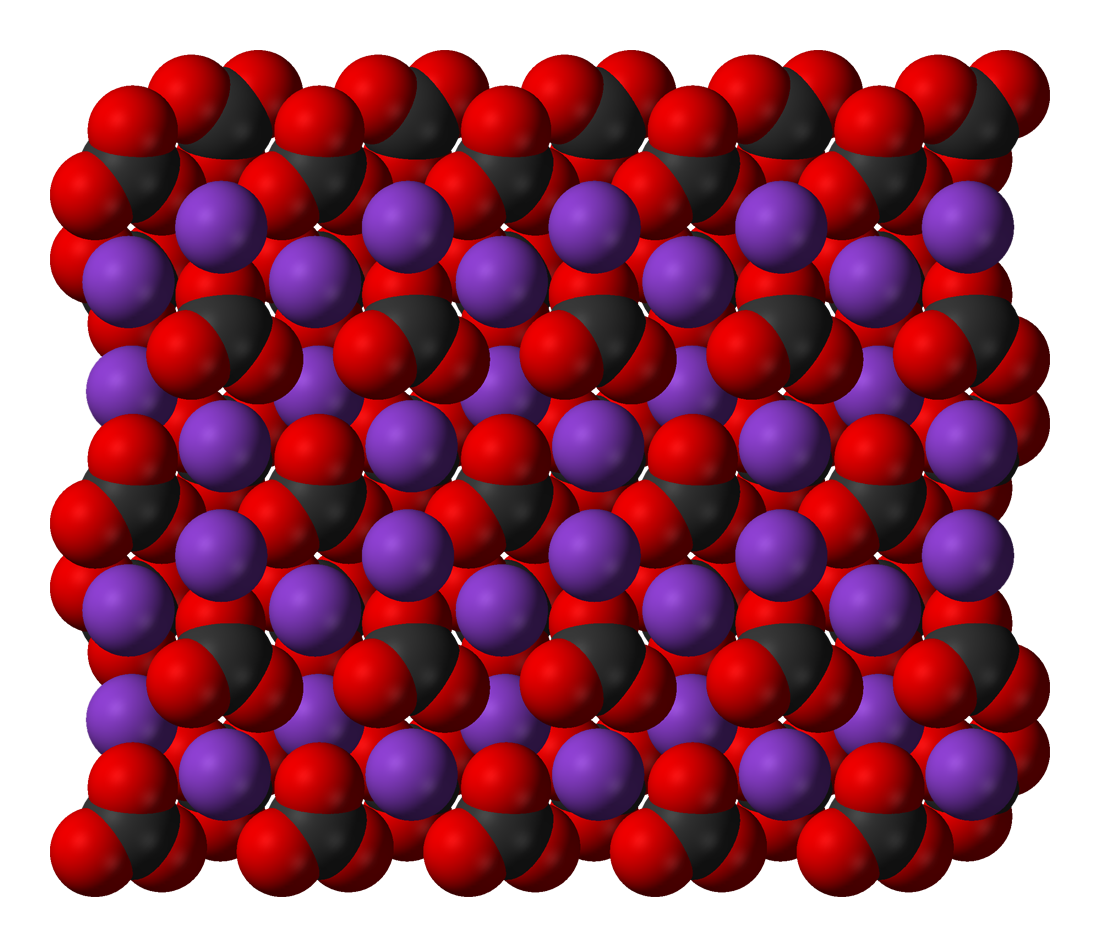

Potassium carbonate

View on Wikipedia | |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Potassium carbonate

| |

| Other names

Carbonate of potash, dipotassium carbonate, sub-carbonate of potash, pearl ash, pearlash, potash, salt of tartar, salt of wormwood.

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.008.665 |

| E number | E501(i) (acidity regulators, ...) |

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII |

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| K2CO3 | |

| Molar mass | 138.205 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | White, hygroscopic solid |

| Density | 2.43 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 891 °C (1,636 °F; 1,164 K) |

| Boiling point | Decomposes |

| 110.3 g/(100 mL) (20 °C) 149.2 g/(100 mL) (100 °C) | |

| Solubility | |

| Acidity (pKa) | 10.25 |

| −59.0·10−6 cm3/mol | |

| Thermochemistry[1] | |

Heat capacity (C)

|

114.4 J/(mol·K) |

Std molar

entropy (S⦵298) |

155.5 J/(mol·K) |

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−1151.0 kJ/mol |

Gibbs free energy (ΔfG⦵)

|

−1063.5 kJ/mol |

Enthalpy of fusion (ΔfH⦵fus)

|

27.6 kJ/mol |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Warning | |

| H302, H315, H319, H335 | |

| P261, P305+P351+P338 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | Non-flammable |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose)

|

1870 mg/kg (oral, rat)[2] |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | ICSC 1588 |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions

|

|

Other cations

|

|

Related compounds

|

|

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Potassium carbonate is the inorganic compound with the formula K2CO3. It is a white salt, which is soluble in water and forms a strongly alkaline solution. It is deliquescent, often appearing as a damp or wet solid. Potassium carbonate is used in production of dutch process cocoa powder,[3] production of soap and production of glass.[4] Commonly, it can be found as the result of leakage of alkaline batteries.[5] Potassium carbonate is a potassium salt of carbonic acid. This salt consists of potassium cations K+ and carbonate anions CO2−3, and is therefore an alkali metal carbonate.

History

[edit]Potassium carbonate is the primary component of potash and the more refined pearl ash or salt of tartar. Historically, pearl ash was created by baking potash in a kiln to remove impurities. The fine, white powder remaining was the pearl ash. The first patent issued by the US Patent Office was awarded to Samuel Hopkins in 1790 for an improved method of making potash and pearl ash.[6]

In late 18th-century North America, before the development of baking powder, pearl ash was used as a leavening agent for quick breads.[7][8]

Production

[edit]The modern commercial production of potassium carbonate is by reaction of potassium hydroxide with carbon dioxide:[4]

- 2 KOH + CO2 → K2CO3 + H2O

From the solution crystallizes the sesquihydrate K2CO3·1.5H2O ("potash hydrate"). Heating this solid above 200 °C (392 °F) gives the anhydrous salt. In an alternative method, potassium chloride is treated with carbon dioxide in the presence of an organic amine to give potassium bicarbonate, which is then calcined:

- 2 KHCO3 → K2CO3 + H2O + CO2

Applications

[edit]- (historically) for soap, glass, and dishware production;[citation needed]

- as a dietary potassium supplement, containing 56% of elemental potassium,[9] in tablet or powder form to address low blood potassium levels caused by inadequate nourishment, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, or potassium-depleting medications such as corticosteroids or diuretics;[10][11]

- as a mild drying agent where other drying agents, such as calcium chloride and magnesium sulfate, may be incompatible. It is not suitable for acidic compounds, but can be useful for drying an organic phase if one has a small amount of acidic impurity. It may also be used to dry some ketones; alcohols, and amines prior to distillation.[12]

- in cuisine, where it has many traditional uses. It is used in some types of Chinese noodles and mooncakes, as well as Asian grass jelly and Japanese ramen. German gingerbread recipes often use potassium carbonate as a baking agent.[13]

- in the alkalization of cocoa powder to produce Dutch process chocolate by balancing the pH (i.e., reduce the acidity) of natural cocoa beans; it also enhances aroma—the process of adding potassium carbonate to cocoa powder is usually called "Dutching" (and the products referred to as Dutch-processed cocoa powder), as the process was first developed in 1828 by Dutchman Coenraad Johannes van Houten;[citation needed]

- as a buffering agent in the production of mead or wine;[citation needed]

- in antique documents, it is reported to have been used to soften hard water;[14]

- as a fire suppressant in extinguishing deep-fat fryers and various other oil/fat/grease related fires;[citation needed][citation needed]

- in condensed aerosol fire suppression, although as the byproduct of potassium nitrate;[citation needed]

- as an ingredient in welding fluxes, and in the flux coating on arc-welding rods;[citation needed]

- as an animal feed ingredient to satisfy the potassium requirements of farmed animals such as broiler breeder chickens;[citation needed]

- as an acidity regulator in Swedish snus snuff tobacco.[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ CRC handbook of chemistry and physics: a ready-reference book of chemical and physical data. William M. Haynes, David R. Lide, Thomas J. Bruno (2016-2017, 97th ed.). Boca Raton, Florida. 2016. ISBN 978-1-4987-5428-6. OCLC 930681942.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Chambers, Michael. "ChemIDplus - 584-08-7 - BWHMMNNQKKPAPP-UHFFFAOYSA-L - Potassium carbonate [USP] - Similar structures search, synonyms, formulas, resource links, and other chemical information". chem.sis.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2014-08-12.

- ^ "The Difference Between Natural and Alkalized Cacao Powder and its Uses". Cocoa Supply BV - NL-BIO-01. 14 March 2022. Retrieved 10 August 2025.

- ^ a b H. Schultz; G. Bauer; E. Schachl; F. Hagedorn; P. Schmittinger (2005). "Potassium Compounds". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a22_039. ISBN 3-527-30673-0.

- ^ List, Jenny (October 19, 2022). "Crusty Leaking Cells Kill Your Tech. Just What's Going On?". Hackaday. Archived from the original on May 30, 2023.

- ^ "Milestones in U.S. patenting". www.uspto.gov. Archived from the original on 2023-03-22. Retrieved 2023-08-04.

- ^ See references to "pearl ash" in "American Cookery" by Amelia Simmons, printed by Hudson & Goodwin, Hartford, 1796.

- ^ Civitello, Linda (2017). Baking powder wars: the cutthroat food fight that revolutionized cooking. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. pp. 18–22. ISBN 978-0-252-04108-2.

- ^ Zakiah, K.; Maulana, M. R.; Widowati, L. R.; Mutakin, J. (2021). "Applications of guano and K2CO3 on soil potential-P, potential-K on Andisols". IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 648 012185. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/648/1/012185.

- ^ "Office of Dietary Supplements - Potassium". Archived from the original on 2022-08-11. Retrieved 2024-12-18.

- ^ "Potassium Carbonate: What is it and where is it used?". Archived from the original on 2024-07-17. Retrieved 2024-12-18.

- ^ Leonard, J.; Lygo, B.; Procter, G. "Advanced Practical Organic Chemistry" 1998, Stanley Thomas Publishers Ltd

- ^ Dunk, Anja (2021). Advent. London: Quadrille. pp. 13, 24, 26. ISBN 978 1 78713 726 4.

- ^ Lydia M. Child (1832). The American Frugal Housewife.

Bibliography

[edit]- A Dictionary of Science, Oxford University Press, New York, 2004

- Yu. Platonov, Andrew; Evdokimov, Andrey; Kurzin, Alexander; D. Maiyorova, Helen (29 June 2002). "Solubility of Potassium Carbonate and Potassium Hydrocarbonate in Methanol". Journal of Chemical & Engineering Data. 47 (5): 1175–1176. doi:10.1021/je020012v.

External links

[edit]Potassium carbonate

View on GrokipediaProperties

Physical Properties

Potassium carbonate appears as a white, odorless, hygroscopic powder or granules that readily absorbs moisture from the air, leading to deliquescence in humid conditions.[1][5] This property makes it challenging to store without proper sealing, as it can form a damp or wet solid upon exposure to moist air.[1] The compound has a density of 2.43 g/cm³ at 20°C, reflecting its compact crystalline structure in the solid state.[6] It melts at 891°C, transitioning to a liquid phase before reaching its decomposition temperature of approximately 1200°C, at which point it breaks down without boiling.[5][7] Potassium carbonate exhibits high solubility in water, dissolving at 112 g/100 mL at 20°C to form a strongly alkaline solution; it is also soluble in glycerol but insoluble in ethanol and acetone.[5][1] Its specific heat capacity is approximately 0.83 J/g·K for the solid, indicating moderate capacity to store thermal energy. Thermal conductivity of the solid is low, around 0.44 W/m·K, which limits rapid heat transfer in bulk applications.| Property | Value | Conditions | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density | 2.43 g/cm³ | 20°C | Alfa Chemistry |

| Melting Point | 891°C | - | Fisher SDS |

| Decomposition Temperature | ~1200°C | - | Save My Exams |

| Solubility in Water | 112 g/100 mL | 20°C | Fisher SDS |

| Specific Heat Capacity | 0.83 J/g·K | Solid | JESTEC |

| Thermal Conductivity | 0.44 W/m·K | Solid | JESTEC |