Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

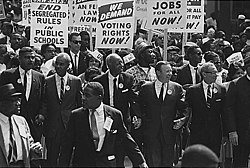

Political demonstration

View on Wikipedia

| Part of the Politics series |

| Democracy |

|---|

|

|

A political demonstration is an action by a mass group or collection of groups of people in favor of a political or other cause or people partaking in a protest against a cause of concern; it often consists of walking in a mass march formation and either beginning with or meeting at a designated endpoint, or rally, in order to hear speakers. It is different from mass meeting.

Demonstrations may include actions such as blockades and sit-ins. They can be either nonviolent or violent, with participants often referring to violent demonstrations as "militant." Depending on the circumstances, a demonstration may begin as nonviolent and escalate to violence. Law enforcement, such as riot police, may become involved in these situations. Police involvement at protests is ideally to protect the participants and their right to assemble. However, officers don't always fulfill this responsibility and it's well-documented that many cases of protest intervention result in power abuse.[1] It may be to prevent clashes between rival groups, or to prevent a demonstration from spreading and turning into a riot.

History

[edit]The term has been in use since the mid-19th century, as was the term "monster meeting", which was coined initially with reference to the huge assemblies of protesters inspired by Daniel O'Connell (1775–1847) in Ireland.[2] Demonstrations are a form of activism, usually taking the form of a public gathering of people in a rally or walking in a march. Thus, the opinion is demonstrated to be significant by gathering in a crowd associated with that opinion.

Demonstrations can promote a viewpoint (either positive or negative) regarding a public issue, especially relating to a perceived grievance or social injustice. A demonstration is usually considered more successful if more people participate. Research shows that anti-government demonstrations occur more frequently in affluent countries than in poor ones.[3]

Widely recognized political demonstrations include the Boston Tea Party, March on Washington, and the recent George Floyd protests.[4] However, political demonstrations have been occurring for many centuries before these famous ones.

Types

[edit]

There are many types of demonstrations, including a variety of elements. These may include:

- Marches, in which a parade demonstrate while moving along a set route.

- Rallies, in which people gather to listen to speakers or musicians.

- Picketing, in which people surround an area (normally an employer).

- Sit-ins, in which demonstrators occupy an area, sometimes for a stated period but sometimes indefinitely, until they feel their issue has been addressed, or they are otherwise convinced or forced to leave.

- Nudity, in which they protest naked – here the antagonist may give in before the demonstration happens to avoid embarrassment.

Demonstrations are sometimes spontaneous gatherings, but are also utilized as a tactical choice by movements. They often form part of a larger campaign of nonviolent resistance, often also called civil resistance. Demonstrations are generally staged in public, but private demonstrations are certainly possible, especially if the demonstrators wish to influence the opinions of a small or very specific group of people. Demonstrations are usually physical gatherings, but virtual or online demonstrations are certainly possible.

Topics of demonstrations often deal with political, economic, and social issues. Particularly with controversial issues, sometimes groups of people opposed to the aims of a demonstration may themselves launch a counter-demonstration with the aim of opposing the demonstrators and presenting their view. Clashes between demonstrators and counter-demonstrators may turn violent.

Government-organized demonstrations are demonstrations which are organized by a government. The Islamic Republic of Iran,[5][6] the People's Republic of China,[7] Republic of Cuba,[8] the Soviet Union[9] and Argentina,[10] among other nations, have had government-organized demonstrations.

Times and locations

[edit]

Sometimes the date or location chosen for the demonstration is of historical or cultural significance, such as the anniversary of some event that is relevant to the topic of the demonstration.

Locations are also frequently chosen because of some relevance to the issue at hand. For example, if a demonstration is targeted at issues relating to foreign nation, the demonstration may take place at a location associated with that nation, such as an embassy of the nation in question.

While fixed demonstrations may take place in pedestrian zones, larger marches usually take place on roads. It may happen with or without an official authorization.

Nonviolence or violence

[edit]Protest marches and demonstrations are a common nonviolent tactic. They are thus one tactic available to proponents of strategic nonviolence. However, the reasons for avoiding the use of violence may also derive, not from a general doctrine of nonviolence or pacifism, but from considerations relating to the particular situation that is faced, including its legal, cultural and power-political dimensions: this has been the case in many campaigns of civil resistance.[11]

A common tactic used by nonviolent campaigners is the "dilemma demonstration." Activist trainer Daniel Hunter describes this term as covering "actions that force the target to either let you do what you want, or be shown as unreasonable as they stop you from doing it".[12] A study by Srdja Popovic and Sophia McClennen won the 2020 Brown Democracy Medal for its examination of 44 examples of dilemma demonstrations and the ways in which they were used to achieve goals within civil resistance campaigns.[13]

Some demonstrations and protests can turn, at least partially, into riots or mob violence against objects such as automobiles and businesses, bystanders and the police.[14] Police and military authorities often use non-lethal force or less-lethal weapons, such as tasers, rubber bullets, pepper spray, and tear gas against demonstrators in these situations.[15] Sometimes violent situations are caused by the preemptive or offensive use of these weapons which can provoke, destabilize, or escalate a conflict.

The protests following the murder of George Floyd are well-known examples of political demonstrations addressing racial injustice and police brutality. These demonstrations, which spread across the United States and around the world, brought attention to systemic issues within law enforcement and the broader society. This movement highlighted the importance of political demonstrations in driving social change and influencing public policy, but also showed how protests can turn violent through police intervention.[16]

As a known tool to prevent the infiltration by agents provocateurs,[17] the organizers of large or controversial assemblies may deploy and coordinate demonstration marshals, also called stewards.[18][19]

Policing

[edit]Protest policing or public order policing is part of a state’s response to political dissent and social movements. Police maintenance of public order during protest is an essential component of liberal democracy, with military response to protest being more common under authoritarian regimes.[20]

Australasian, European, and North American democratic states have all experienced increased surveillance of protest movements and more militarized protest policing since 1995 and through the first decades of the 21st century.[21][22]

Criminalization of dissent is legislation or law enforcement that penalizes political dissent. It may also be accomplished through media that controls public discourse to delegitimize critics of the state. Study of protest criminalization places protest policing in a broader framework of criminology and sociology of law.[21]Law by country

[edit]

International

[edit]The right to demonstrate peacefully is guaranteed by international conventions, in particular by the articles 21 and 22 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (right of peaceful assembly and right of association). Its implementation is monitored by the United Nations special rapporteur on the right of peaceful assembly and association. In 2019, its report expressed alarm at the restrictions on the freedom of peaceful assembly:[23]

The Special Rapporteur has expressed concern regarding laws adopted in many countries that impose harsh restrictions on assemblies, including provisions relating to blanket bans, geographical restrictions, mandatory notifications and authorizations. [...] The need for prior authorization in order to hold peaceful protests [is] contrary to international law [...].

Australia

[edit]A report released by the Human Rights Law Centre in 2024 states that based on British common law, "Australian courts regard [the right to assembly] as a core part of a democratic system of government." However, there are a number of limitations placed on demonstrations and protest under state, territory and federal legislation, with forty-nine laws introduced regarding them since 2004.[24]

Brazil

[edit]Freedom of assembly in Brazil is granted by art. 5th, item XVI, of the Constitution of Brazil (1988).

Egypt

[edit]Germany

[edit]In Germany, the right to protest is considered a fundamental right in the Grundgesetz.[25] For open-air assemblies, this right may be restricted.[25]

Russia

[edit]Freedom of assembly in the Russian Federation is granted by Art. 31 of the Constitution adopted in 1993:

Citizens of the Russian Federation shall have the right to gather peacefully, without weapons, and to hold meetings, rallies, demonstrations, marches and pickets.[26]

Demonstrations and protests are further regulated by the Federal Law of the Russian Federation No.54-FZ "On Meetings, Rallies, Demonstrations, Marches and Pickets". If the assembly in public is expected to involve more than one participant, its organisers are obliged to notify executive or local self-government authorities of the upcoming event few days in advance in writing. However, legislation does not foresee an authorisation procedure, hence the authorities have no right to prohibit an assembly or change its place unless it threatens the security of participants or is planned to take place near hazardous facilities, important railways, viaducts, pipelines, high voltage electric power lines, prisons, courts, presidential residences or in the border control zone. The right to gather can also be restricted in close proximity of cultural and historical monuments.

Singapore

[edit]Public demonstrations in Singapore are not common, in part because cause-related events require a licence from the authorities. Such laws include the Public Entertainment and Meetings Act and the Public Order Act.

Ukraine

[edit]United Kingdom

[edit]

Under the Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005 and the Terrorism Act 2006, there are areas designated as 'protected sites' where people are not allowed to go. Previously, these were military bases and nuclear power stations, but the law changed in 2007 to include other, generally political areas, such as Downing Street, the Palace of Westminster, and the headquarters of MI5 and MI6. Previously, trespassers to these areas could not be arrested if they had not committed another crime and agreed to be escorted out, but this will change[when?] following amendments to the law.[27]

Human rights groups fear the powers could hinder peaceful protest. Nick Clegg, the then Liberal Democrat home affairs spokesman, said: "I am not aware of vast troops of trespassers wanting to invade MI5 or MI6, still less running the gauntlet of security checks in Whitehall and Westminster to make a point. It's a sledgehammer to crack a nut." Liberty, the civil liberties pressure group, said the measure was "excessive".[28]

One of the biggest demonstration in the UK was the people vote march, on 19 October 2019, with around 1 million demonstrators related to the Brexit.

In 2021, the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom ruled that blocking roads can be a lawful way to demonstrate.[29]

United States

[edit]The First Amendment of the United States Constitution specifically allows the freedom of assembly as part of a measure to facilitate the redress of such grievances. "Amendment I: Congress shall make no law ... abridging ... the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances."[30]

A growing trend in the United States has been the implementation of "free speech zones", or fenced-in areas which are often far-removed from the event which is being protested; critics of free-speech zones argue that they go against the First Amendment of the United States Constitution by their very nature, and that they lessen the impact the demonstration might otherwise have had. In many areas it is required to get permission from the government to hold a demonstration.[31]

See also

[edit]- Civil resistance

- Crowd control

- Fare strike

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

- List of uprisings led by women

- Mass mobilization

- Nonviolent resistance

- Right to protest

- Petition

- List of rallies and protest marches in Washington, D.C.

- List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States

References

[edit]- ^ "The Role of Police at Protests | ACLU of New Jersey". www.aclu-nj.org. 2023-05-03. Retrieved 2025-02-07.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary

- ^ Shishkina, Alisa; Bilyuga, Stanislav; Korotayev, Andrey (2017). "GDP Per Capita and Protest Activity: A Quantitative Reanalysis". Cross-Cultural Research. 52 (4): 106939711773232. ISSN 1069-3971.

- ^ Whipps, Heather; published, Brandon Specktor (2020-06-04). "10 Historically Significant Political Protests". livescience.com. Retrieved 2025-03-04.

- ^ Analysis: Iran Sends Terror-Group Supporters To Arafat's Funeral Procession Archived 2004-11-14 at the Wayback Machine "...state-organized rallies..."

- ^ "Why Washington and Tehran are headed for a showdown" Archived 2020-10-28 at the Wayback Machine The Hedge Fund Journal 16 April 2006.

- ^ Global News, No. GL99-072 Archived 2021-04-23 at the Wayback Machine China News Digest, 3 June 1989.

- ^ Cubans ponder life without Fidel Archived 2007-03-12 at the Wayback Machine The Washington Times 2 August 2006.

- ^ "Democracy in the Former Soviet Union: 1991–2004" Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Power and Interest News Report 28 December 2004

- ^ Nicolás Pizzi (2012-07-29). "Militancia todo terreno: Sacan a presos de la cárcel para actos del kirchnerismo" [All-terrain militants: Prisoners are taken out of jail to take part in Kirchnerist demonstrations] (in Spanish). Clarín. Retrieved July 29, 2012.

- ^ Adam Roberts and Timothy Garton Ash (eds.), Civil Resistance and Power Politics: The Experience of Non-violent Action from Gandhi to the Present, Oxford University Press, 2009, especially at pp. 14–20.[1] Includes chapters by specialists on the various movements

- ^ Hunter, Daniel (2024-07-29). "Strengthen a Campaign with Dilemma Demonstrations". The Commons Social Change Library. Retrieved 2024-09-19.

- ^ VanHise, James L. (2021-09-21). "Dilemma Actions: The Power of Putting your Opponent in a Bind". The Commons Social Chnage Library. Retrieved 2024-09-19.

- ^ The Design of Protest. University of Texas Press. 2018. doi:10.7560/315767. ISBN 978-1-4773-1577-4.

- ^ "How American police gear up to respond to protests". www.cnn.com. Retrieved 2025-02-10.

- ^ "Race and Policing". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2025-03-03.

- ^ Stratfor (2004) Radical, Anarchist Groups Pose Their Own Threat, Archived 2012-03-07 at the Wayback Machine, published by Stratfor, June 4, 2004 quote:

Another common tactic is to infiltrate legitimate demonstrations in the attempt to stir widespread violence and rioting, seen most recently in a spring anti-Iraq war gathering in Vancouver, Canada. This has become so commonplace that sources within activist organizations have told STRATFOR they police their own demonstrations to prevent infiltration by fringe groups.

- ^ Belyaeva et al. (2007) Guidelines on Freedom of Peaceful Assembly, Archived 2021-03-23 at the Wayback Machine, published by OSCE's Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights. Alternative version Archived 2010-06-25 at the Wayback Machine, Sections § 7–8, 156–162

- ^ Bryan, Dominic The Anthropology of Ritual: Monitoring and Stewarding Demonstrations in Northern Ireland, Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine, Anthropology in Action, Volume 13, Numbers 1–2, January 2006, pp.22–31(10)

- ^ Porta, Donatella Della; Reiter, Herbert Reiter. Policing Protest: The Control of Mass Demonstrations in Western Democracies. U of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-1-4529-0333-0.

- ^ a b Selmini, Rossella; Di Ronco, Anna (November 2023). "The Criminalization of Dissent and Protest". Crime and Justice. 52: 197–231. doi:10.1086/727553. hdl:11585/958859. ISSN 0192-3234.

- ^ Wood, Lesley J. (2014). Crisis and control: the militarization of protest policing. Toronto: Between the Lines. ISBN 978-0-7453-3388-5.

- ^ "Report of the Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association (Clément Nyaletsossi Voulé)". undocs.org. 11 September 2019. p. 13. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ Mejia-Canales, David; Human Rights Law Centre (2024-08-26). "Protest in Peril: Our Shrinking Democracy". The Commons Social Change Library. Retrieved 2024-09-19.

- ^ a b "Art 8 GG - Einzelnorm". www.gesetze-im-internet.de. Retrieved 2025-05-08.

- ^ "Chapter 2 of the Constitution of the Russian Federation". Archived from the original on 2010-03-04. Retrieved 2012-07-17.

- ^ Morris, Steven, "New powers against trespassers at key sites Archived 2021-03-31 at the Wayback Machine", The Guardian, 24 March 2007. Retrieved on 23 June 2007.

- ^ Brown, Colin, "No-go Britain: Royal Family and ministers protected from protesters by new laws Archived 2007-06-06 at the Wayback Machine", The Independent, 4 June 2007. Retrieved on 23 June 2007.

- ^ Lizzie Dearden (25 June 2021). "Supreme Court backs protesters and rules blocking roads can be 'lawful' way to demonstrate". The Independent. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ "America's Founding Documents". 30 October 2015.

- ^ Kellie Pantekoek, Esq. (12 October 2023).'Protest Laws by State'. FindLaw.

External links

[edit]- Special Rapporteur of the United Nations on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association

- 10 Principles for the proper management of assemblies (by Special Rapporteurs of the United Nations)

- "Controlling Public Protest: First Amendment Implications", article about restrictions that may be imposed on public protests, in the FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin (1994)

Political demonstration

View on GrokipediaDefinition and scope

Core definition and elements

A political demonstration is a form of collective public action in which individuals or groups assemble to visibly express support for or opposition to a specific political issue, policy, authority figure, or regime, typically aiming to influence public opinion, policymakers, or societal norms through heightened visibility and disruption.[1][11] Such events distinguish themselves by their intentional use of spatial occupation and symbolic displays to amplify grievances, often seeking to coerce change by demonstrating the scale of discontent or solidarity.[12] Core elements of political demonstrations include:- Public assembly in accessible spaces: Demonstrations occur in streets, squares, or other communal areas to ensure broad witnessability, enabling participants to disrupt normal routines and capture media attention, which amplifies their message beyond immediate attendees.[13][14]

- Expressive and symbolic tactics: Participants employ placards, chants, speeches, marches, or performance art to convey grievances, demands, or claims, transforming abstract political positions into tangible, observable phenomena that signal collective resolve.[14]

- Grievance articulation and objectives: At their foundation, demonstrations articulate specific political dissatisfactions—such as policy failures or institutional biases—and pursue outcomes like reform, accountability, or regime shift, often through non-coercive means that leverage numbers for moral or persuasive pressure.[1][15]

- Disruption and spectacle: To counter institutional inertia, elements of confrontation, spectacle, or temporary disruption are common, heightening urgency and forcing engagement from authorities or bystanders, though these can vary from orderly vigils to more assertive blockades.[15][16]

Distinctions from related forms of assembly

Political demonstrations differ from general public assemblies, such as religious gatherings or cultural events, in their specific intent to advance political objectives, including influencing government policy, challenging authorities, or mobilizing public support for ideological causes, rather than fostering social or spiritual communion.[2][17] This political focus distinguishes them from non-partisan assemblies, where the primary aim is not contention with state power but communal participation.[18] Unlike riots, which legal definitions characterize as violent disturbances involving three or more persons acting with a common unlawful purpose, such as vandalism or assault, political demonstrations emphasize nonviolent expression, even if tensions can lead to escalation.[19][20] U.S. federal and state laws, for instance, protect organized public disapproval in demonstrations under the First Amendment's assembly clause, provided they remain peaceful, whereas riots trigger criminal charges for breaching the peace through destructive acts.[21] Demonstrations also contrast with rallies, which typically involve stationary gatherings centered on speeches or performances to rally supporters for a cause, often in controlled venues, whereas demonstrations frequently incorporate mobile elements like marches along public routes to amplify visibility and disruption.[22] Strikes, another related form, center on economic leverage through labor withdrawal rather than broad political signaling, though they may include assembly components; data from labor histories show strikes succeeding via workplace halts in 60-70% of U.S. cases from 1880-1930, independent of demonstrative scale.[23][1] In scholarly analyses, demonstrations are differentiated from petitions or lobbying by their reliance on physical mass presence to create causal pressure through visibility and potential inconvenience, rather than written appeals or private advocacy, enabling direct empirical measurement of discontent via attendance numbers—e.g., the 1963 March on Washington drew 250,000 participants to signal civil rights urgency.[11] This embodied form contrasts with discursive or electoral assemblies, like voting, where individual participation lacks the collective spectacle that demonstrations leverage for media amplification and policy impact.[24]Historical overview

Pre-modern origins

The earliest recorded instances of organized political demonstrations emerged in ancient Rome through the secessio plebis, a form of mass withdrawal by plebeians to compel concessions from the patrician elite. In 494 BCE, amid heavy indebtedness and exclusion from political power following military service, the plebeians abandoned the city for the Sacred Mount outside Rome, halting labor, military participation, and economic activity until the patricians agreed to create the office of Tribune of the Plebs to protect commoner interests.[25] This tactic recurred in 449 BCE, when plebeians again seceded to the Aventine Hill, securing ratification of the Twelve Tables—a codified legal framework—and further entrenching tribunician veto power over patrician decisions.[26] These secessions functioned as nonviolent collective actions akin to general strikes, demonstrating plebeian leverage through disruption rather than violence, and laid foundational precedents for using mass assembly and abstention to extract political reforms.[27] In ancient Greece, political expression more commonly occurred through formal assemblies like the Athenian ekklesia, but spontaneous protests and riots supplemented these structures during periods of elite overreach. Archaic city-states such as Megara witnessed crowd actions blending revelry, ritual, and dissent against aristocratic rule, where lower classes gathered publicly to challenge reciprocity breakdowns between rich and poor, often escalating into riots that pressured oligarchs.[28] The Athenian Revolution of 508–507 BCE involved popular uprisings against the tyrant Hippias, with citizens mobilizing en masse to support Cleisthenes' reforms, which restructured tribes and councils to dilute aristocratic control and foster broader participation.[29] Such events highlight early reliance on public gatherings to voice grievances, though they blurred into revolts rather than sustained demonstrations, reflecting causal pressures from inequality and exclusion in pre-democratic polities. Medieval Europe saw political demonstrations evolve into larger-scale popular revolts, often triggered by fiscal burdens and feudal inequities, with crowds assembling to petition or coerce authorities. The Jacquerie in France (1358) mobilized thousands of peasants in armed gatherings against noble exactions during the Hundred Years' War, destroying manor houses in a wave of localized protests that underscored rural discontent with seigneurial rights.[30] Similarly, England's Peasants' Revolt of 1381 drew 50,000–100,000 participants to London, marching on the capital to demand abolition of poll taxes and serfdom, culminating in direct confrontations with royal officials before suppression.[31] Urban uprisings, such as those in Flemish cities during the 14th century, involved guild members and artisans parading and rioting against patrician monopolies, revealing how economic grievances fueled public assemblies that tested monarchical tolerance for collective action.[32] These pre-modern episodes, while frequently violent, established patterns of mass mobilization for redress, driven by tangible causal factors like taxation and status hierarchies rather than abstract ideologies.[33]19th and 20th century developments

In the nineteenth century, political demonstrations expanded significantly due to urbanization, industrialization, and expanding suffrage, transitioning from localized gatherings to coordinated mass actions aimed at electoral and social reform. In Britain, the Chartist movement (1838–1857) mobilized working-class participants through petitions and marches demanding universal male suffrage, with events like the 1842 general strike involving coordinated stoppages across industrial centers and drawing tens of thousands to rallies.[34] Similarly, in Ireland, Daniel O'Connell's "monster meetings" of the 1840s for Catholic emancipation and repeal of the Act of Union attracted up to 300,000 attendees at nonviolent assemblies, establishing precedents for large-scale, orderly public advocacy despite risks of suppression.[35] In the United States, agrarian discontent post-Civil War fueled protests by farmers' organizations like the Patrons of Husbandry (Grange), which orchestrated rallies and legislative lobbying against railroad monopolies and monetary policies, challenging the dominance of the two major parties.[36] European revolutions of 1848 exemplified the era's volatile demonstrations, where crowds in cities like Paris, Vienna, and Berlin erected barricades and held assemblies to demand constitutional governments and national unification, often escalating to armed confrontations that toppled regimes temporarily but highlighted demonstrations' role in catalyzing political change.[34] Abolitionist and women's rights campaigns further institutionalized protests; U.S. conventions such as Seneca Falls in 1848 drew hundreds to deliberate on suffrage and equality, evolving into public marches by the 1850s, while transatlantic networks amplified tactics like petition drives and public speeches.[37] Labor unrest, including strikes in textile mills and mines, increasingly incorporated marches to publicize grievances, though frequent violence underscored limited legal protections for assembly. The twentieth century marked refinements in demonstration strategies, with greater emphasis on nonviolence, media amplification, and international influence, particularly through anti-colonial and suffrage efforts. Women's suffrage movements organized parades, such as the 1913 Woman Suffrage Procession in Washington, D.C., which involved 5,000 marchers asserting voting rights and influencing public opinion toward the Nineteenth Amendment's ratification in 1920.[38] In India, Mahatma Gandhi's satyagraha campaigns, including the 1930 Salt March covering 240 miles and sparking arrests of over 60,000 participants, demonstrated civil disobedience's efficacy against colonial rule, inspiring global activists with disciplined, symbolic mass actions.[39] Pre-World War II labor and anti-fascist demonstrations grew in scale and organization; U.S. events like the 1932 Bonus Army march, where 43,000 veterans encamped in Washington seeking war debt payments, exposed governmental responses to economic protest, while European street rallies against rising authoritarianism in the 1930s often clashed with police, foreshadowing totalitarian suppression of assembly.[40] These developments coincided with emerging legal frameworks, such as U.S. Supreme Court rulings affirming assembly rights, and technological advances like radio broadcasts, which extended demonstrations' reach beyond physical crowds.[35] Overall, the period saw protests shift toward strategic nonviolence and broader participation, laying groundwork for postwar expansions while revealing persistent tensions between state authority and public expression.Post-1945 global proliferation

Following the end of World War II in 1945, political demonstrations proliferated worldwide amid decolonization, the establishment of the United Nations in 1945—which codified assembly rights in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights—and the expansion of mass media enabling rapid mobilization and visibility. In the immediate postwar period, labor strikes surged, with over 4,600 strikes involving 4.6 million workers in the United States alone during 1945–1946, reflecting economic grievances and demands for better conditions after wartime controls lifted. Similar unrest occurred globally, as in the 1945–1946 strike waves in Europe and Asia tied to reconstruction and inflation. Decolonization fueled protests in Africa and Asia; for instance, mass demonstrations contributed to Ghana's independence from Britain in 1957, marking the first sub-Saharan African nation to gain sovereignty post-1945.[41] The 1960s marked a peak in global protest activity, driven by civil rights struggles, anti-colonial sentiments, and opposition to the Vietnam War. In the United States, the Civil Rights Movement featured landmark events like the 1963 March on Washington, where approximately 250,000 participants advocated for racial equality and economic justice.[42] Concurrently, 1968 witnessed synchronized uprisings across continents: in France, May 1968 protests involved up to 10 million strikers demanding social reforms; in Czechoslovakia, the Prague Spring demonstrations challenged Soviet influence until suppressed; and in Mexico, student protests culminated in the Tlatelolco massacre on October 2, 1968, killing hundreds. These events exemplified a transnational wave fueled by postwar economic growth, youth radicalism, and Cold War tensions, surpassing prior scales of coordination.[43] In Eastern Europe and the Soviet sphere, spontaneous demonstrations erupted against communist regimes, such as the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, where over 200,000 protested Soviet control, leading to brief reforms before invasion.[44] Subsequent decades saw further proliferation, particularly in the 1980s and early 1990s, as anti-authoritarian movements leveraged demonstrations to dismantle dictatorships. Poland's Solidarity trade union organized strikes and rallies from 1980, peaking with millions participating in 1989 Round Table talks that precipitated the regime's fall. The 1989 Eastern European revolutions relied heavily on mass protests, including the Velvet Revolution in Czechoslovakia with daily demonstrations of up to 500,000 in Prague, contributing to communism's collapse across the Warsaw Pact nations without widespread violence. Anti-apartheid protests in South Africa intensified globally, with domestic townships like Soweto hosting sustained actions from the 1976 uprising onward, pressuring the regime toward 1994 elections.[45] Empirical analyses indicate sustained growth in protest frequency post-1945, with waves in the late 1960s, late 1980s, and early 1990s giving way to even higher incidence; for example, mass anti-government protests rose 11.5% annually from 2009 to 2019, exceeding historical benchmarks and spanning all regions, from sub-Saharan Africa's rapid increase to Middle East and North Africa hotspots.[46] This escalation correlates with urbanization, improved transportation, and digital precursors like fax machines in 1989, though mainstream sources often emphasize progressive causes while underreporting conservative or economic drivers in non-Western contexts, reflecting institutional biases toward framing unrest through ideological lenses. Demonstrations evolved from localized strikes to globalized tactics, influencing policy in democracies via public pressure and challenging autocracies through sheer numbers, though success varied by regime response and internal cohesion.[47]Motivations and typology

Underlying drivers

Political demonstrations are fundamentally propelled by perceived grievances that render the status quo intolerable, often rooted in material hardships, institutional failures, or violations of normative expectations. Empirical analyses of protest participation reveal that economic dissatisfaction—such as unemployment spikes, inflation surges, or austerity measures—serves as a primary catalyst, as these conditions erode living standards and amplify relative deprivation among affected populations. For example, structural adjustment programs implemented in the 1980s and 1990s correlated with heightened protest frequency in developing economies, where fiscal restraints and price liberalizations directly intensified household vulnerabilities, prompting collective mobilization against policy-induced suffering.[48] Similarly, cross-national datasets indicate that protests surge during periods of economic downturns, with participants citing livelihood threats as a core motivator over abstract ideological appeals. Political drivers center on erosions of accountability and representation, including corruption scandals, electoral manipulations, or suppressions of dissent, which foster widespread distrust in governing elites. Studies of global protest events underscore how perceptions of elite capture—where ruling coalitions prioritize self-enrichment over public welfare—escalate mobilization, as evidenced in the Arab Spring uprisings triggered by revelations of regime graft in Tunisia on December 17, 2010.[49] Quantitative assessments further link lower democracy scores and higher corruption indices to elevated protest incidence, with non-democratic regimes experiencing 20-30% more unrest episodes due to blocked institutional channels for redress.[50] Instrumental motivations, such as demands for policy reversals or leadership changes, dominate participant surveys, though expressive elements like signaling moral outrage against perceived injustices also sustain engagement.[51] Social and psychological factors amplify these drivers through networks of solidarity and moral imperatives, where individual participation hinges on shared identities and anticipated reciprocity from peers. Research in social psychology identifies a sense of injustice—triggered by events like police brutality or discriminatory laws—as a pivotal mobilizer, heightening efficacy beliefs and reducing free-rider inhibitions in collective action.[52] Moral obligations, derived from ethical commitments to equity or rights, independently predict attendance, particularly among youth confronting intergenerational inequities, as seen in climate strikes where aspirational concerns for future viability outweighed immediate personal costs.[53][54] However, these dynamics interact with opportunity structures; protests proliferate when grievances align with weakened state repression or elite divisions, enabling coordination via digital tools that lower organizational barriers since the 2010s.[3]Classification by form and objective

Political demonstrations are categorized by form, which denotes the tactical methods and organizational structures used to assemble and express dissent, and by objective, which specifies the underlying demands or goals aimed at influencing political outcomes. Empirical analyses of global protest events from 2006 to 2020 identify marches as the predominant form, occurring in 61.3% of documented cases, often involving coordinated movement along public routes to maximize visibility and media coverage.[55] Assemblies and rallies follow closely, featured in 59.0% of events, typically stationary gatherings centered on speeches, chants, or performances to rally participants and convey messages to authorities.[55] Other common forms include blockades (21.6%), which disrupt infrastructure to compel attention, and occupations (20.8%), entailing prolonged seizure of spaces like public buildings or squares to symbolize sustained resistance.[55] Less frequent but notable tactics encompass strikes, civil disobedience actions such as sit-ins, and digital mobilizations, with over 250 nonviolent methods cataloged across datasets, reflecting adaptations to local contexts and technological shifts.[55] Hybrid forms blending multiple tactics, like marches culminating in rallies, amplify impact by combining mobility with oratory, as observed in labor protests where walkouts transition to street demonstrations. Disruptive forms, including property occupations or traffic impediments, carry higher risks of escalation but signal urgency, contrasting with symbolic or expressive forms like vigils that prioritize moral suasion over confrontation. These tactical choices are shaped by resource availability, perceived regime tolerance, and strategic calculations, with nonviolent methods prevailing in democratic settings due to lower repression costs. By objective, demonstrations cluster around demands for systemic reform, with "real democracy"—encompassing anti-corruption and participatory governance—driving 27.7% of events, as in widespread mobilizations against electoral fraud or elite capture.[55] Socio-economic grievances, particularly jobs, wages, and labor conditions, motivate 18.4% of protests, fueling strikes and marches in response to austerity or inequality spikes, such as those against pension reforms in Chile (2016).[55] Corruption ranks highly at 19.9%, often intersecting with governance failures, while environmental and climate justice objectives account for 13%, evident in blockades targeting fossil fuel projects.[55] Identity-based goals, including ethnic/racial justice (e.g., Black Lives Matter actions in the US, 2020) and women's rights (7.4%), pursue recognition and policy shifts, whereas anti-international institution protests (11.4%) critique bodies like the IMF for imposing unpopular reforms.[55] Objectives may overlap, as economic demands frequently embed political critiques, but pure instrumental aims—to extract concessions like policy reversals—differ from expressive ones signaling solidarity or moral outrage. Success correlates with alignment between form and objective; for instance, disruptive tactics suit urgent economic demands, while rallies bolster long-term advocacy for rights. These classifications, derived from event catalogs, underscore protests' role in aggregating grievances, though outcomes hinge on mobilization scale and elite responses rather than form alone.Strategic dynamics

Nonviolent versus violent approaches

Political demonstrations can adopt nonviolent approaches, emphasizing peaceful assembly, civil disobedience, and symbolic actions to exert pressure without physical harm, or violent approaches involving property damage, clashes with authorities, or targeted attacks to coerce change through fear or disruption. Nonviolent strategies typically prioritize mass participation, moral persuasion, and institutional disruption, such as strikes or boycotts, whereas violent tactics aim for direct confrontation or sabotage but risk escalating state repression. Empirical analyses of civil resistance campaigns from 1900 to 2006, covering over 300 cases, indicate that nonviolent efforts achieved their goals in 53% of instances, compared to 26% for violent ones, attributing higher success to nonviolence's ability to mobilize larger, more diverse crowds—including potential defectors from regime forces—and to generate domestic and international legitimacy that undermines authoritarian narratives.[56][57] Mechanistically, nonviolent demonstrations foster broader societal buy-in by avoiding alienation of moderates and by exposing regime brutality through disproportionate responses, as seen in the 1963 March on Washington, where over 250,000 participants advocated civil rights without violence, contributing to legislative victories like the Civil Rights Act of 1964 by highlighting peaceful demands against systemic injustice. In contrast, violent escalations, such as the 2021 U.S. Capitol riot involving assaults on police and property destruction, often provoke unified backlash, erode public sympathy, and invite severe countermeasures, resulting in minimal policy shifts and heightened polarization rather than sustained concessions. Studies further reveal that nonviolent campaigns are roughly twice as likely to transition to democracy, with violent ones correlating with prolonged instability or authoritarian backsliding, due to normalized coercion and fractured coalitions.[58][59] While nonviolence's edge holds in aggregate data, critics contend it falters against ultra-repressive states unwilling to concede legitimacy, citing cases like the Syrian uprising's violent turn after initial nonviolent protests in 2011 led to civil war without regime change, or arguing that datasets undercount "defensive" violence within ostensibly nonviolent movements. Nonetheless, comparative reviews of 65 quantitative studies affirm nonviolent revolutions yield superior institutional reforms, such as improved governance and reduced corruption, over violent counterparts, which often entrench elite capture or cycles of retribution. Strategic choices thus hinge on context: nonviolence leverages scale and resilience for long-term gains in semi-open systems, while violence may deter in low-stakes scenarios but historically amplifies risks of failure and societal costs.[60][61]Mobilization and organizational factors

Mobilization for political demonstrations typically occurs through interpersonal networks, where individuals are recruited by acquaintances already engaged in activism, amplifying participation beyond isolated grievances. Empirical analyses of protest recruitment, such as those examining online diffusion models, demonstrate that ties to prior participants predict involvement, with network density correlating to higher turnout rates in events like the 2011 Egyptian uprising.[62] This relational mechanism addresses free-rider problems inherent in collective action, as trust and reciprocity incentivize commitment over individualistic calculations.[63] Resource mobilization theory posits that effective demonstrations require access to material and immaterial assets, including funding, communication channels, and skilled coordinators, rather than widespread discontent alone. Studies applying this framework to historical movements, such as U.S. civil rights campaigns, find that groups with formalized resource bases—via affiliations with unions or NGOs—sustain larger, more persistent actions compared to ad hoc gatherings.[64] For instance, logistical support like transportation and legal aid has been quantified as boosting attendance by 20-50% in documented labor strikes.[65] Organizational structures further determine demonstration viability, with hierarchical leadership enabling strategic planning, such as route selection and media outreach, while decentralized models foster adaptability but risk fragmentation. Research on nonviolent campaigns reveals that protests led by coalitions with predefined roles—evident in the 1989 Velvet Revolution—achieve greater cohesion and bargaining power against authorities.[66] In contrast, leaderless efforts, often amplified by social media, mobilize quickly but frequently dissipate without sustained infrastructure, as seen in Occupy Wall Street's 2011 decline due to internal disorganization.[67] Digital tools have transformed mobilization by lowering barriers to coordination, enabling viral dissemination of event details across platforms like Twitter during the 2019 Hong Kong protests, where geolocated posts correlated with localized spikes in attendance.[68] However, reliance on such networks demands robust offline backups, as algorithmic suppression or internet shutdowns—imposed in over 100 instances globally since 2016—can halve projected turnout without pre-existing organizational redundancies.[69] Overall, hybrid models integrating digital outreach with traditional institutions yield the highest empirical success rates in scaling participation.[70]Empirical effectiveness

Key studies and metrics

A seminal empirical dataset on the effectiveness of political demonstrations is the Nonviolent and Violent Campaigns and Outcomes (NAVCO) dataset, developed by Erica Chenoweth and colleagues, which codes 323 maximalist campaigns—those seeking regime change, secession, or territorial liberation—conducted between 1900 and 2006. Nonviolent campaigns succeeded in attaining their objectives 53 percent of the time, double the 26 percent success rate for violent campaigns.[56] This advantage stems from nonviolent methods attracting broader participation, averaging over 11 percent of the population versus under 1 percent for violent efforts, thereby facilitating defections among security forces, bureaucrats, and economic elites that underpin regimes.[56]| Campaign Type | Success Rate | Dataset Scope | Key Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nonviolent | 53% | 1900–2006 (323 campaigns) | Peak participation >3.5% of population correlates with 100% success in observed cases[71] |

| Violent | 26% | 1900–2006 (323 campaigns) | Lower participation and loyalty shifts |