Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Quechua people

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

| Person | Runa / Nuna |

|---|---|

| People | Runakuna / Nunakuna |

| Language | Runasimi / Nunasimi |

Quechua people (/ˈkɛtʃuə/,[7][8] US also /ˈkɛtʃwɑː/;[9] Spanish: [ˈketʃwa]) , Quichua people or Kichwa people are Indigenous peoples of South America who speak the Quechua languages, which originated among the Indigenous people of Peru. Although most Quechua speakers are native to Peru, there are some significant populations in Ecuador, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, and Argentina.

The most common Quechua dialect is Southern Quechua. The Kichwa people of Ecuador speak the Kichwa dialect; in Colombia, the Inga people speak Inga Kichwa.

The Quechua word for a Quechua speaker is runa or nuna ("person"); the plural is runakuna or nunakuna ("people"). "Quechua speakers call themselves Runa -- simply translated, "the people".[10]

Some historical Quechua people are:

- The Chanka people lived in the Huancavelica, Ayacucho, and Apurímac regions of Peru.

- The Huanca people of the Junín Region of Peru spoke Quechua before the Incas did.

- The Inca established the largest empire of the pre-Columbian era.

- The Chincha, an extinct merchant kingdom of the Chincha Islands of Peru.

- The Qolla inhabited the Potosí, Oruro, and La Paz departments of Bolivia.

- The Cañari of Ecuador adopted the Quechua language from the Inca.

Historical and sociopolitical background

[edit]The speakers of Quechua total some 5.1 million people in Peru, 1.8 million in Bolivia, 2.5 million in Ecuador (Hornberger and King, 2001), and according to Ethnologue (2006) 33,800 in Chile, 55,500 in Argentina, and a few hundred in Brazil. Only a slight sense of common identity exists among these speakers spread all over Peru, Bolivia and Ecuador. The various Quechua dialects are in some cases so different from one another that mutual understanding is not possible. Quechua was spoken not only by the Incas, but also by long-term enemies of the Inca Empire, including the Huanca (Wanka is a Quechua dialect spoken today in the Huancayo area) and the Chanka (the Chanca dialect of Ayacucho) of Peru, and the Kañari (Cañari) in Ecuador. Quechua was spoken by some of these people, for example, the Wanka, before the Incas of Cusco, while other people, especially in Bolivia but also in Ecuador, adopted Quechua only in Inca times or afterward.[citation needed]

Quechua became Peru's second official language in 1969 under the military dictatorship of Juan Velasco Alvarado. There have been later tendencies toward nation-building among Quechua speakers, particularly in Ecuador (Kichwa) but also in Bolivia, where there are only slight linguistic differences from the original Peruvian version. An indication of this effort is the umbrella organization of the Kichwa people in Ecuador, ECUARUNARI (Ecuador Runakunapak Rikcharimuy). Some Christian organizations also refer to a "Quechua people", such as the Christian shortwave radio station HCJB, "The Voice of the Andes" (La Voz de los Andes).[11] The term "Quechua Nation" occurs in such contexts as the name of the Education Council of the Quechua Nation (Consejo Educativo de la Nación Quechua, CENAQ), which is responsible for Quechua instruction or bilingual intercultural schools in the Quechua-speaking regions of Bolivia.[12][13] Some Quechua speakers say that if nation-states in Latin America had been built following the European pattern, they would be a single, independent nation.[citation needed]

Material culture and social history

[edit]

Despite their ethnic diversity and linguistic distinctions, the various Quechua ethnic groups have numerous cultural characteristics in common. They also share many of these with the Aymara or other Indigenous peoples of the central Andes.

Traditionally, Quechua identity is locally oriented and inseparably linked in each case with the established economic system. It is based on agriculture in the lower altitude regions, and on pastoral farming in the higher regions of the Puna. The typical Andean community extends over several altitude ranges and thus includes the cultivation of a variety of arable crops and/or livestock. The land is usually owned by the local community (ayllu) and is either cultivated jointly or redistributed annually.

Beginning with the colonial era and intensifying after the South American states had gained their independence, large landowners appropriated all or most of the land and forced the Native population into bondage (known in Ecuador as Huasipungo, from Kichwa wasipunku, "front door"). Harsh conditions of exploitation repeatedly led to revolts by the Indigenous farmers, which were forcibly suppressed. The largest of these revolts occurred in 1780–1781 under the leadership of Husiy Qawriyil Kunturkanki.

Some Indigenous farmers re-occupied their ancestors' lands and expelled the landlords during the takeover of governments by dictatorships in the middle of the 20th century, such as in 1952 in Bolivia (Víctor Paz Estenssoro) and 1968 in Peru (Juan Velasco Alvarado). The agrarian reforms included the expropriation of large landowners. In Bolivia, there was a redistribution of the land to the Indigenous population as their private property. This disrupted traditional Quechua and Aymara culture based on communal ownership, but ayllus has been retained up to the present time in remote regions, such as in the Peruvian Quechua community of Q'ero.

The struggle for land rights continues up to the present time to be a political focal point of everyday Quechua life. The Kichwa ethnic groups of Ecuador which are part of the ECUARUNARI association were recently able to regain communal land titles or the return of estates—in some cases through militant activity. Especially the case of the community of Sarayaku has become well known among the Kichwa of the lowlands, who after years of struggle were able to successfully resist expropriation and exploitation of the rain forest for petroleum recovery.[citation needed]

A distinction is made between two primary types of joint work. In the case of mink'a, people work together for projects of common interest (such as the construction of communal facilities). Ayni is, in contrast, reciprocal assistance, whereby members of an ayllu help a family to accomplish a large private project, for example, house construction, and in turn can expect to be similarly helped later with a project of their own.

In almost all Quechua ethnic groups, many traditional handicrafts are an important aspect of material culture. This includes a tradition of weaving handed down from Inca times or earlier, using cotton, wool (from llamas, alpacas, guanacos, and vicuñas), and a multitude of natural dyes, and incorporating numerous woven patterns (pallay). Houses are usually constructed using air-dried clay bricks (tika, or in Spanish adobe), or branches and clay mortar ("wattle and daub"), with the roofs being covered with straw, reeds, or puna grass (ichu).

The disintegration of the traditional economy, for example, regionally through mining activities and accompanying proletarian social structures, has usually led to a loss of both ethnic identity and the Quechua language. This is also a result of steady migration to large cities (especially Lima), which has resulted in acculturation by Hispanic society there.

Foods and crops

[edit]

Quechua people cultivate and eat a variety of foods. They domesticated potatoes, which originated in the region, and cultivated thousands of potato varieties, which are used for food and medicine. Climate change is threatening their potato and other traditional crops but they are undertaking conservation and adaptation efforts.[14][15] Quinoa is another staple crop grown by the Quechua people.[16] Ch’arki (the origin of the English word jerky) is a dried (and sometimes salted) meat. It was traditionally made from llama meat that was sun- and freeze-dried in the Andean sun and cold nights, but is now also often made from horse and beef, with variation among countries.[17][18]

Pachamanca, a Quechua word for a pit cooking technique used in Peru, includes several types of meat such as chicken, beef, pork, lamb, and/or mutton; tubers such as potatoes, sweet potatoes, yucca, uqa/ok’a (oca in Spanish), and mashwa; other vegetables such as maize/corn and fava beans; seasonings; and sometimes cheese in a small pot and/or tamales.[19][20]

Guinea pigs are also raised for meat.[16] Other foods and crops include the meat of llamas and alpacas as well as beans, barley, hot peppers, coriander, and peanuts.[14][16]

Examples of recent persecution of Quechuas

[edit]

Up to the present time, Quechuas continue to be victims of political conflicts and ethnic persecution. In the internal conflict in Peru in the 1980s between the government and Sendero Luminoso about three-quarters of the estimated 70,000 death toll were Quechuas, whereas the war parties were without exception whites and mestizos (people with mixed descent from both Natives and Spaniards).[21]

The forced sterilization policy under Peruvian president Alberto Fujimori affected almost exclusively Quechua and Aymara women, a total of about 270,000 (and 22,000 men) according to official figures.[22] The sterilization program lasted for over five years between 1996 and 2001. During this period, women were coerced into forced sterilization.[23] Sterilizations were often performed under dangerous and unsanitary conditions, as the doctors were pressured to perform operations under unrealistic government quotas, which made it impossible to properly inform women and receive their consent.[24] The Bolivian film director Jorge Sanjinés dealt with the issue of forced sterilization in 1969 in his Quechua-language feature film Yawar Mallku.

Quechuas have been left out of their nation's regional economic growth in recent years. The World Bank has identified eight countries on the continent to have some of the highest inequality rates in the world. The Quechuas have been subject to these severe inequalities, as many of them have a much lower life expectancy than the regional average, and many communities lack access to basic health services.[25]

Perceived ethnic discrimination continues to play a role at the parliamentary level. When the newly elected Peruvian members of parliament Hilaria Supa Huamán and María Sumire swore their oath of office in Quechua—for the first time in the history of Peru in an Indigenous language—the Peruvian parliamentary president Martha Hildebrandt and the parliamentary officer Carlos Torres Caro refused their acceptance.[26]

Mythology

[edit]Practically all Quechuas in the Andes have been nominally Catholic since colonial times. Nevertheless, traditional religious forms persist in many regions, blended with Christian elements – a fully integrated syncretism. Quechua ethnic groups also share traditional religions with other Andean peoples, particularly belief in Mother Earth (Pachamama), who grants fertility and to whom burnt offerings and libations are regularly made. Also important are the mountain spirits (apu) as well as lesser local deities (wak'a), who are still venerated especially in southern Peru.

The Quechuas came to terms with their repeated historical experience of tragedy in the form of various myths. These include the figure of Nak'aq or Pishtaco ("butcher"), the white murderer who sucks out the fat from the bodies of the Indigenous peoples he kills,[27] and a song about a bloody river.[28] In their myth of Wiraquchapampa,[29] the Q'ero people describe the victory of the Apus over the Spaniards. Of the myths still alive today, the Inkarrí myth common in southern Peru is especially interesting; it forms a cultural element linking the Quechua groups throughout the region from Ayacucho to Cusco.[29][30][31] Some Quechuas consider classic products of the region such as corn beer, chicha, coca leaves, and local potatoes as having a religious significance, but this belief is not uniform across communities.

Contribution in modern medicine

[edit]Quinine, which is found naturally in the bark of the cinchona tree, is known to be used by Quechuas people for malaria-like symptoms.

When chewed, coca acts as a mild stimulant and suppresses hunger, thirst, pain, and fatigue; it is also used to alleviate altitude sickness. Coca leaves are chewed during work in the fields as well as during breaks in construction projects in Quechua provinces. Coca leaves are the raw material from which cocaine, one of Peru's most historically important exports, is chemically extracted.

Traditional clothing

[edit]

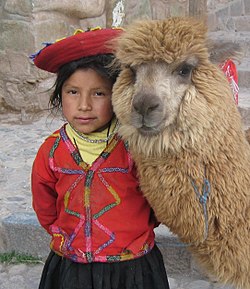

Many Indigenous women wear colorful traditional attire, complete with bowler-style hats. The hat has been worn by Quechua and Aymara women since the 1920s when it was brought to the country by British railway workers. They are still commonly worn today.[32]

The traditional dress worn by Quechua women today is a mixture of styles from Pre-Spanish days and Spanish Colonial peasant dress. Starting at puberty, Quechua girls begin wearing multiple layers of petticoats and skirts, showing off the family's wealth and making her a more desirable bride. Married women also wear multiple layers of petticoats and skirts. Younger Quechua men generally wear Western-style clothing, the most popular being synthetic football shirts and tracksuit trousers. In certain regions, women also generally wear Western-style clothing. Older men still wear dark wool knee-length handwoven bayeta pants. A woven belt called a chumpi which protects the lower back when working in the fields is also worn. Men's fine dress includes a woolen waistcoat, similar to a sleeveless juyuna as worn by women but referred to as a chaleco, and often richly decorated.

The most distinctive part of men's clothing is the handwoven poncho. Nearly every Quechua man and boy has a poncho, generally red decorated with intricate designs. Each district has a distinctive pattern. In some communities such as Huilloc, Patacancha, and many villages in the Lares Valley ponchos are worn as daily attire. However, most men use their ponchos on special occasions such as festivals, village meetings, weddings, etc.

As with the women, ajotas, sandals made from recycled tires, are the standard footwear. They are cheap and durable.

A ch'ullu, a knitted hat with earflaps, is frequently worn. The first ch'ullu that a child receives is traditionally knitted by their father. In the Ausangate region, chullos are often ornately adorned with white beads and large tassels called t'ikas. Men sometimes wear a felt hat called a sombrero over the top of the ch'ullu decorated with centillo, finely decorated hat bands. Since ancient times men have worn small woven pouches called ch'uspa used to carry their coca leaves.[33]

Quechua-speaking ethnic groups

[edit]

The following list of Quechua ethnic groups is only a selection and delimitations vary. In some cases, these are village communities of just a few hundred people, in other cases ethnic groups of over a million.

- Inca (historic)

Peru

[edit]Lowlands

[edit]Highlands

[edit]Ecuador

[edit]Highlands

[edit]Lowlands

[edit]Bolivia

[edit]Colombia

[edit]Notable people

[edit]- Túpac Amaru II, Revolutionary

- Angélica Mendoza de Ascarza, Peruvian human rights activist

- Kimberly Barzola, American community organizer and artist

- Benjamin Bratt, American actor

- Manco Cápac, Sapa Inca

- Luzmila Carpio, Bolivian musician

- Andrónico Rodríguez, Bolivian trade unionist and politician

- Martín Chambi, Peruvian photographer

- Renata Flores Rivera,[34] Peruvian musician

- Oswaldo Guayasamín, Ecuadorian painter

- Ollanta Humala, former President of Peru

- Antauro Humala, Peruvian ethnocacerist

- Josh Keaton, American actor

- Q'orianka Kilcher, American Actress

- Nancy Iza Moreno, Kichwa leader[35]

- Leonidas Iza, Ecuadorian activist and Indigenous leader

- Delfín Quishpe, Ecuadorian musician and politician

- Tarcila Rivera Zea, Peruvian activist

- Izkia Siches, Chilean physician and politician

- Magaly Solier, Peruvian actress and musician

- Diego Quispe Tito, Painter

- Francisco Tito Yupanqui, Sculptor

- Alejandro Toledo, former President of Peru

- Edison Flores, Peruvian footballer

- Renato Tapia, Peruvian footballer

- Tania Pariona Tarqui, Peruvian politician

See also

[edit]- Kichwa

- Inkarrí

- Yanantin

- Sumak kawsay

- Andean textiles

- Chuspas

- Chakitaqlla

- Chinchaypujio District

- Quechuan languages

- Indigenous peoples in Argentina

- Indigenous peoples in Bolivia

- Indigenous peoples of Peru

- Indigenous peoples in Ecuador

- Secret of the Incas movie with conversation and singing in Quechua

References

[edit]- ^ "Peru | Joshua Project".

- ^ "Bolivia | Joshua Project".

- ^ "Ecuador | Joshua Project".

- ^ "Argentina | Joshua Project".

- ^ "Colombia | Joshua Project".

- ^ "Chile | Joshua Project".

- ^ "Quechua - meaning of Quechua in Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English". Ldoceonline.com. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ Oxford Living Dictionaries, British and World English

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 9781405881180

- ^ "Language in Peru | Frommer's".

- ^ CUNAN CRISTO JESUS BENDICIAN HCJB: "El Pueblo Quichua".

- ^ "CEPOs". Cepos.bo. 28 June 2013. Archived from the original on 28 June 2013. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ [1][permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "Climate Change Threatens Quechua and Their Crops in Peru's Andes - Inter Press Service". Ipsnews.net. 29 December 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ "The Quechua: Guardians of the Potato". Culturalsurvival.org. 15 February 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ a b c "Quechua - Introduction, Location, Language, Folklore, Religion, Major holidays, Rites of passage". Everyculture.com. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ Kelly, Robert L.; Thomas, David Hurst (1 January 2013). Archaeology: Down to Earth. Cengage Learning. pp. 141–. ISBN 978-1-133-60864-6.

- ^ Noble, Judith; Lacasa, Jaime (2010). Introduction to Quechua: Language of the Andes (2nd ed.). Dog Ear Publishing. pp. 325–. ISBN 978-1-60844-154-9.

- ^ Yang, Ina (30 June 2015). "Peru's Pitmasters Bury Their Meat in the Earth, Inca-Style". Npr.org. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ "Oca". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Archived from the original on 5 October 2023. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ Orin Starn: Villagers at Arms: War and Counterrevolution in the Central-South Andes. In Steve Stern (ed.): Shining and Other Paths: War and Society in Peru, 1980–1995. Duke University Press, Durham and London, 1998, ISBN 0-8223-2217-X

- ^ "Peru forced sterilisations case reaches key stage". BBC News. 1 March 2021.

- ^ Carranza Ko, Ñusta (4 September 2020). "Making the Case for Genocide, the Forced Sterilization of Indigenous Peoples of Peru". Genocide Studies and Prevention. 14 (2): 90–103. doi:10.5038/1911-9933.14.2.1740. ISSN 1911-0359.

- ^ Kovarik, Jacquelyn (25 August 2019). "Silenced No More in Peru". NACLA Report on the Americas. 51 (3): 217–222. doi:10.1080/10714839.2019.1650481. ISSN 1071-4839. S2CID 203153827.

- ^ "Discriminated against for speaking their own language". World Bank. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- ^ "Archivo - Servindi - Servicios de Comunicación Intercultural". Servindi.org. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ Examples (Ancash Quechua with Spanish translation) at "Kichwa kwintukuna patsaatsinan". Archived from the original on 19 December 2007. Retrieved 12 May 2009. and (in Chanka Quechua) "Nakaq (Nak'aq)". Archived from the original on 12 March 2010. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- ^ Karneval von Tambobamba. In: José María Arguedas: El sueño del pongo, cuento quechua y Canciones quechuas tradicionales. Editorial Universitaria, Santiago de Chile 1969. Online: "Runasimipi Takikuna". Archived from the original on 5 June 2009. Retrieved 12 May 2009. (auf Chanka-Quechua). German translation in: Juliane Bambula Diaz and Mario Razzeto: Ketschua-Lyrik. Reclam, Leipzig 1976, p. 172

- ^ a b Thomas Müller and Helga Müller-Herbon: Die Kinder der Mitte. Die Q'ero-Indianer. Lamuv Verlag, Göttingen 1993, ISBN 3-88977-049-5

- ^ Jacobs, Philip. "Inkarrí (Inkarriy, Inka Rey) - Q'iru (Q'ero), Pukyu, Wamanqa llaqtakunamanta". Runasimi.de. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ Juliane Bambula Diaz und Mario Razzeto: Ketschua-Lyrik. Reclam, Leipzig 1976, pp. 231 ff.

- ^ "La Paz and Tiwanaku: colour, bowler hats and llama fetuses - Don't Forget Your Laptop!". 10 September 2011. Archived from the original on 10 September 2011. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ "My Peru - A Guide to the Culture and Traditions of the Andean Communities of Peru". Myperu.org. Archived from the original on 11 August 2017. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ Barrientos, Brenda. "Renata Flores & Her Music Are An Act of Indigenous Resistance". www.refinery29.com. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- ^ Isuma TV

Dixon, Melissa, "Against all odds: UM grad charts new course with $90,000 fellowship" [1]

External links

[edit]- Quichua, Peoples of the World Foundation

- World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples - Bolivia : Highland Aymara and Quechua, UNHCR

- ^ Montana Kaimin May 2, 2024

Quechua people

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Historical Development

Pre-Inca Origins

The Quechua languages, which define the ethnic identity of the Quechua people, originated in the Andean highlands of central Peru, with proto-Quechua likely spoken by agricultural communities in regions such as modern-day Ayacucho and Junín departments.[8] Linguistic reconstruction indicates that the initial expansion and divergence of proto-Quechua dialects began around 2,000 years ago, well before the formation of the Inca Empire in the 15th century AD.[9] This timeline positions early Quechua speakers among pre-Inca highland populations practicing subsistence farming, camelid herding, and adaptation to diverse altitudinal zones through vertical ecological exploitation.[10] Direct archaeological evidence linking specific sites to proto-Quechua speakers remains elusive due to the absence of pre-Columbian writing systems and the perishable nature of linguistic artifacts, forcing reliance on comparative linguistics and indirect cultural correlations.[8] Hypotheses suggest ties to earlier horizons like the Wari (Huari) culture (circa 600–1000 AD), which flourished in central Peru and exhibited administrative complexity and highland settlement patterns consistent with proto-Quechua dispersal, though genetic and material evidence does not conclusively confirm linguistic continuity.[11] The oldest attested dialect varieties, such as those in the Huánuco-Huaylas region, preserve archaic features supporting an origin in coastal-influenced highland zones before southward migration.[8] Pre-Inca Quechua communities existed as decentralized groups of agropastoralists, exploiting potatoes, quinoa, and llamas in terraced landscapes, with social organization centered on kin-based ayllus that persisted into later periods.[12] Their linguistic homeland in central-southern Peru facilitated gradual diffusion northward and southward via trade routes and intermarriage, predating Inca mitmaq resettlement policies by centuries.[13] Estimates place the proto-language's coherence around the mid-1st millennium AD, with diversification driven by geographic isolation in sierra valleys rather than imperial expansion.[9] This pre-Inca foundation underscores the Quechua as an indigenous Andean continuum, independent of later imperial overlays.Integration into the Inca Empire

The Inca Empire, centered in the Cusco region where a dialect of Southern Quechua was spoken natively, began its major phase of expansion under Pachacuti (r. 1438–1471), incorporating pre-existing Quechua-speaking groups such as the Huancas in the central Andean highlands. These communities, already present before Inca dominance, were integrated through military conquest and administrative reorganization, allying with or submitting to Inca forces during campaigns against rivals like the Chancas around 1438. Integration involved reciprocal labor systems (ayni and minka) and mandatory tribute (mit'a), compelling Quechua populations to support imperial agriculture, road construction spanning over 40,000 kilometers, and terrace farming that sustained an estimated 10–12 million subjects empire-wide.[14][5] To unify diverse ethnic groups—including Aymara, Puquina, and other non-Quechua speakers—the Incas imposed their Cusco Quechua as the administrative lingua franca, standardizing communication for governance, quipu record-keeping, and religious propagation centered on Inti worship. This policy, enforced from the early 1400s when Cusco became the empire's capital, facilitated control over conquered territories extending from southern Colombia to central Chile by 1525, significantly expanding Quechua's demographic footprint through mitmaq resettlement policies that relocated tens of thousands of families to strategic frontiers. While local languages persisted in daily use, Quechua's prestige as the elite and official tongue fostered cultural assimilation, with ethnohistorical accounts indicating Quechua speakers formed a core loyal base for Inca military expansions under subsequent rulers like Topa Inca Yupanqui (r. 1471–1493).[14] Archaeological evidence from sites like Hatun Xaukipampa reveals integrated Quechua communities contributing to specialized crafts, such as textile production and metallurgy, under imperial oversight, reinforcing economic interdependence. This era marked the coalescence of a broader Quechua ethnic identity, distinct from purely local affiliations, as Inca patronage elevated Quechua language and customs across the Tawantinsuyu, though without fully eradicating substrate influences from conquered polities. By the empire's peak, Quechua variants were spoken by a substantial portion of the population, laying foundations for its post-conquest persistence despite Spanish disruptions.[5]Spanish Colonial Period

The Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire in 1532 subjected Quechua-speaking populations, who formed the ethnic core of the empire's highland societies, to direct colonial rule under the Viceroyalty of Peru.[15] Francisco Pizarro's forces, aided by internal Inca divisions and native auxiliaries, captured Atahualpa at Cajamarca, leading to the empire's fragmentation and the imposition of encomienda grants that allocated Quechua communities as tribute-paying labor pools to Spanish settlers.[16] This system extracted goods and services, often exacerbating exploitation through abuse by encomenderos despite royal protections like the New Laws of 1542. Demographic catastrophe followed, with Quechua populations decimated by Old World diseases, warfare, and overwork; in the Cusco heartland, native numbers fell by over 90 percent from the 1530s onward, reducing an estimated pre-conquest Andean total of 8-10 million to around 600,000 by 1620.[15][17] Viceroy Francisco de Toledo's reforms in the 1570s centralized control via the mita, a rotational draft reviving Inca precedents but intensifying coercion, compelling one-seventh of adult males from 16 highland provinces—predominantly Quechua—to labor in silver mines like Potosí for 12-24 month shifts under harsh conditions, contributing to sustained population stagnation in affected regions.[16] Evangelization efforts relied on Quechua as a vehicular language for conversion, with Dominican and Jesuit missionaries producing the first Christian texts, including the 1584 Doctrina Christiana y Catecismo para Instrucción de Indios, to catechize highland communities through translations that adapted Andean concepts to Catholic doctrine.[18] Policies of reducciones forcibly resettled dispersed ayllus into nucleated villages for surveillance and Christianization, eroding traditional social structures while fostering syncretic practices blending huaca worship with saints' cults, though outright resistance persisted via hidden rituals.[19] Quechua's utility as a lingua franca facilitated administrative records and mestizo mediation but declined with Spanish linguistic dominance by the 18th century, amid growing literacy restrictions on indigenous use.[18] Late colonial unrest culminated in the 1780-1781 Túpac Amaru II rebellion, led by José Gabriel Condorcanqui—a curaca of partial Inca descent—who rallied Quechua peasants against corregidores' extortions, executing officials and mobilizing up to 100,000 followers through Quechua orations invoking Inca restoration before Spanish reprisals crushed the uprising, executing leaders and imposing stricter controls.[20] This event underscored enduring Quechua agency against exploitative tribute and labor demands, foreshadowing independence-era shifts.[21]Post-Independence Era

Following the achievement of independence from Spain—Peru in 1821, Bolivia in 1825, and Ecuador in 1830—Quechua-speaking communities in the Andean republics faced systemic exclusion from political power, which was consolidated by creole elites favoring Spanish language and culture.[22] Governments promoted a unitary national identity that marginalized indigenous customs, with Quechua losing any brief post-independence revival as an administrative language in favor of Spanish dominance.[23] Rural Quechua populations, comprising the majority in highland areas, were relegated to subsistence agriculture and peonage on expanding haciendas, where communal lands were privatized through liberal reforms that benefited landowners.[24] Economic pressures intensified exploitation, as Quechua laborers supplied mines and estates in Bolivia and Peru, enduring poverty and tribute-like obligations despite the formal abolition of colonial forced labor systems.[25] In Peru, the War of the Pacific (1879–1883) exacerbated grievances through wartime devastation, inflated taxes, and administrative abuses, culminating in the Atusparia Revolt of 1885 in Ancash—a major peasant uprising led by indigenous leader Pedro Pablo Atusparia against local officials, involving thousands of Quechua highlanders who briefly captured Huaraz before suppression.[26] [27] Similar unrest occurred in Ecuador's 1871 Cotopaxi Rebellion, where Quechua indigenous protested hacienda encroachments and tribute demands, reflecting broader Andean resistance to republican policies.[28] These events underscored the failure of independence to deliver equity, as indigenous demands for land restitution and autonomy were met with military repression, perpetuating Quechua subordination into the late 19th century.[29] Demographically resilient in rural enclaves, Quechua groups preserved oral traditions and agriculture amid demographic stability estimated at several million across the Andes, though urban migration remained minimal until the 20th century.[30]20th and 21st Century Developments

In Peru, the military government of Juan Velasco Alvarado implemented a radical agrarian reform starting in 1969, expropriating large haciendas and redistributing land to peasant cooperatives, many of which were predominantly Quechua communities previously subjected to exploitative labor systems.[31][32] This reform benefited hundreds of thousands of indigenous peasants by granting them property titles and access to state resources, though it also led to administrative challenges and dependency on government cooperatives.[33] Concurrently, Velasco's regime elevated Quechua's status by lifting speaking bans in 1972 and recognizing it as a national language in 1975, mandating its inclusion in education from 1976 and legal proceedings where it predominated.[34] In Bolivia, the 1953 National Revolution had earlier redistributed lands to indigenous ayllus, disrupting but also empowering traditional Quechua communal structures.[35] Massive rural-to-urban migration accelerated from the mid-20th century, driven by economic opportunities, land pressures, and agrarian changes, drawing millions of Quechua speakers to cities like Lima, Cusco, and La Paz.[36][37] By the late 20th century, this urbanization fostered large peri-urban shantytowns with Quechua cultural enclaves but accelerated language shift toward Spanish due to discrimination and assimilation pressures in urban settings.[38] The Peruvian internal conflict from 1980 to 2000, initiated by the Maoist Shining Path insurgency, devastated Quechua highland regions such as Ayacucho and Huancavelica, where three-quarters of the over 69,000 victims were Quechua-speaking peasants targeted for resisting guerrilla coercion or state forces' reprisals.[39] The violence eroded community structures, economies, and trust, with long-term psychological and social scars persisting in affected areas.[39] Into the 21st century, constitutional reforms in Peru (1993, reinforcing bilingual education), Bolivia, and Ecuador granted Quechua co-official status in indigenous-majority zones and promoted intercultural policies, though implementation lagged due to inadequate funding and entrenched discrimination.[34][12] In Bolivia, the Movement for Socialism (MAS) under Evo Morales from 2006 expanded indigenous political inclusion, benefiting Quechua communities through resource nationalization and reserved legislative seats introduced in 2009.[40] Ecuador's Kichwa (Quechua-speaking) populations gained influence via the CONAIE confederation's mobilizations, contributing to the 2008 constitution's plurinational framework.[41] Cultural revitalization efforts, including bilingual schooling and global promotion of Quechua music and textiles, have countered erosion, yet persistent poverty and urban language loss challenge demographic vitality.[12][38]Language and Linguistic Identity

Origins and Characteristics of Quechua

The Quechua languages descend from Proto-Quechua, an ancestral form believed to have originated in the central Peruvian highlands approximately 2,000 years ago, predating the Inca Empire by over a millennium.[9] This proto-language likely emerged among agropastoral communities in the Andean interior, where it underwent early contact with neighboring linguistic families, including the precursor to Aymara, influencing shared vocabulary in agriculture and herding.[42] Divergence into distinct branches began around this period, with Proto-Quechua splitting into Central (Quechua I) and Peripheral (Quechua II) varieties; the latter further subdivided into Southern and Northern (Ecuadorian) forms, driven by migrations and regional adaptations over centuries.[9] By over 1,000 years ago, significant dialectal variation had developed across central and southern Peru, with the Inca Empire (circa 1400–1532 CE) accelerating spread through administrative use of the Cuzco dialect as a lingua franca, extending it southward to Bolivia and northward to Ecuador.[9][43] Quechua exemplifies an agglutinative language family, where morphemes attach sequentially to roots to convey grammatical meaning, primarily through suffixation with high segmentability and minimal fusion.[44][45] Nominal morphology includes an elaborate case system (e.g., genitive, accusative, locative) marked by suffixes, optional pluralization via -kuna, and possessive marking through person-indexing suffixes identical to verbal subject markers, but lacks grammatical gender or definite articles.[46] Verbal structure features rich inflection for person, tense (including direct/experienced and reported/hearsay pasts), aspect, and evidentiality, alongside derivational suffixes like -chi- for causatives or -naya- for desideratives, enabling polyvalent semantic shifts based on context and position.[44][45] Suffix order follows rigid templates with combinatory restrictions, often prioritizing syntactic organization over strict scopal hierarchy, and nominalization serves as the core mechanism for subordination.[45] Syntactically, Quechua employs subject-object-verb (SOV) order as canonical but allows flexibility due to case-marking, with topic-focus structures highlighted by enclitics such as -qa for topics and -mi for focus or validation.[44] Phonologically, it maintains a compact inventory: three vowel phonemes (/a/, /i/, /u/, with allophonic variants like , in some contexts) and consonants featuring three stop series (voiceless unaspirated, aspirated, and ejective/glottalized) across places of articulation, but no phonemic voiced obstruents in core dialects.[44][46] Stress predictably falls on the penultimate syllable, subject to adjustments for emotive or derivational endings.[44] Historically oral, Quechua adopted a Roman-based orthography post-Spanish contact (from 1560 CE), with a unified system introduced in Peru in 1975 to better reflect phonological contrasts.[46]Dialectal Variations

The Quechua language family encompasses numerous dialects that form a dialect continuum across the Andean region, with varying degrees of mutual intelligibility between adjacent varieties but often low comprehension between distant ones.[47] Traditional linguistic classification, established by Alfredo Torero in 1964, divides Quechua into two primary branches: Quechua I (Central Peruvian) and Quechua II (Peripheral).[48] Quechua I is geographically restricted to the Andean highlands of central and northern Peru, while Quechua II extends more broadly to northern and southern Peru, Ecuador, southern Colombia, Bolivia, northern Chile, and northwestern Argentina.[47] Quechua I dialects, spoken in regions such as Huánuco, Huancayo, and Yauyos, represent an older stratum of the family and exhibit typological features like portmanteau suffixes in verbal inflections for categories such as aspect and number, distinguishing them from Quechua II varieties.[45] These dialects often preserve proto-forms and show less influence from Inca standardization. In contrast, Quechua II is subdivided into three main subgroups: Northern Peruvian (II-A), Ecuadorian-Northern (II-B), and Southern (II-C). The Northern Peruvian subgroup occupies areas north of Lima, featuring transitional phonologies; the Ecuadorian-Northern dialects, including those in Imbabura and Chimborazo provinces, display innovations such as the merger of velar stops /k/ and /q/.[47] The Southern subgroup (II-C), the largest by speaker population with over 6 million users as of recent estimates, predominates in Cuzco, Ayacucho, Puno in Peru, and highland Bolivia, characterized by phonemic distinctions in aspirated and glottalized stops (e.g., /p', t', k', ph, th, kh/).[47] Dialectal variations extend to phonology, vocabulary, and morphology, influenced by substrate languages, Spanish contact, and geographic isolation. For instance, Southern dialects like Cuzco Quechua maintain a 26-consonant inventory with uvulars and ejectives, while some Central varieties simplify these systems.[47] Vocabulary divergences can reach 20-30% between branches, affecting mutual intelligibility, which drops below 50% between Quechua I and distant Quechua II forms.[47] Standardization efforts, such as Peru's 1975 unified alphabet and Bolivia's Southern Quechua norms, aim to bridge gaps but have limited uptake due to entrenched local varieties. Overall, the family includes at least 15-45 distinct spoken dialects, with ongoing debate on whether to treat them as a single macrolanguage or separate languages.[45]Current Status and Revitalization Efforts

Quechua, comprising numerous dialects across the Quechua I and Quechua II branches, is currently spoken by an estimated 8 to 12 million people, with the largest populations in Peru (approximately 4.7 million), Bolivia (around 2 million), and Ecuador (where the Kichwa variety predominates with over 1 million speakers).[38][49] Despite these figures, the language family faces endangerment at the dialect level, as intergenerational transmission declines and many rural varieties shift toward Spanish dominance, particularly in urbanizing areas where economic opportunities favor monolingual Spanish proficiency.[50][38] Quechua holds co-official status in Peru alongside Spanish, as established under the 1975 constitution following earlier recognition in 1969; in Bolivia, it is one of three co-official indigenous languages under the 2009 constitution; and in Ecuador, the Kichwa variant received official recognition in 2008.[51][52] Revitalization initiatives have intensified since the early 2000s, focusing on education, media, and policy to counter linguistic shift. In Peru, bilingual intercultural education programs integrate Quechua into primary schooling in highland regions, though implementation varies due to teacher shortages and material scarcity; similar efforts in Bolivia emphasize Quechua in public schools under the Plurinational State's framework, while Ecuador's Ministry of Education promotes Kichwa immersion in indigenous communities.[52][53] Community-driven projects, such as radio broadcasts in multiple dialects across the three countries, have expanded access, with stations producing content in Quechua I and II varieties to reach remote audiences.[38] Digital tools and hemispheric reclamation programs, including apps and online courses, further support urban diaspora speakers, though systemic challenges like social stigmatization and inadequate standardization persist, limiting widespread vitality.[54][38]Demographics and Geographic Distribution

Population Estimates and Trends

Estimates of the Quechua population, encompassing both ethnic self-identifiers and speakers of Quechua languages, range from 8 to 12 million individuals primarily residing in the Andean highlands of South America.[2][38] These figures derive from national censuses distinguishing between mother-tongue speakers and broader ethnic affiliation, with self-identification often exceeding active language use due to cultural heritage claims among bilingual or Spanish-dominant descendants.[55] In Peru, which hosts the largest concentration, the 2017 national census enumerated 5,176,809 individuals self-identifying as Quechua, comprising approximately 16.6% of the country's 31.2 million inhabitants.[56] Concurrently, about 13.9% of Peruvians reported speaking Quechua, equating to roughly 4.3 million speakers, though urban bilingualism blurs precise counts.[57] Bolivia's 2012 census recorded 1,837,105 Quechua self-identifiers, representing a significant portion of the nation's 41% indigenous population share, with speakers numbering around 2 million amid similar ethnic-linguistic overlaps.[58] In Ecuador, the Kichwa subgroup totals approximately 800,000 ethnic members, including about 527,000 speakers, concentrated in the Sierra and Amazonian regions.[59] Smaller communities persist in Argentina (around 100,000), Chile (under 20,000), Colombia, and trace diaspora elsewhere, adding several hundred thousand to continental totals.[2]| Country | Estimated Quechua/Kichwa Population | Basis | Year/Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peru | 5,176,809 | Ethnic self-ID | 2017 (INEI census via IWGIA)[56] |

| Bolivia | 1,837,105 | Ethnic self-ID | 2012 census[58] |

| Ecuador | ~800,000 | Ethnic (incl. speakers) | Recent estimates[59] |

| Others | ~200,000–500,000 | Speakers/ethnic | Varied censuses[2] |

Distribution in Peru

The Quechua constitute Peru's largest indigenous population, with 5,176,809 individuals self-identifying as such in the 2017 national census conducted by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática (INEI), equivalent to 22.3% of the population aged 12 and older.[62] Of these, approximately 3,799,780 reported Quechua as their first language, representing 13.9% of the total Peruvian population.[63] This group is overwhelmingly concentrated in the Andean sierra, the highland backbone of Peru spanning central and southern departments, where they form the demographic majority in numerous rural districts and provinces adapted to high-altitude agriculture and pastoralism. Primary regions of settlement include Áncash, Apurímac, Ayacucho, Cusco, Huancavelica, Huánuco, Junín, and Pasco in the central Andes, alongside southern extensions into Puno and Tacna; these areas align with historical Quechua dialect clusters such as Yaru (Huánuco), Central (Junín), and Southern (Cusco-Ayacucho).[64] Within these departments, Quechua communities predominate in intermontane valleys and altiplano fringes, with densities highest in provinces like Andahuaylas (Apurímac) and Huamanga (Ayacucho), where linguistic and ethnic continuity reflects pre-colonial polities like the Chanka and Huanca.[64] Urbanization and rural-to-urban migration, driven by economic pressures since the mid-20th century, have dispersed Quechua populations to coastal lowlands, particularly Lima, where over 1 million Quechua descendants reside in peripheral districts, sustaining ayllu-derived social networks amid mestizo majorities.[65] Demographic trends indicate stability in self-identification but a gradual shift toward bilingualism, with Quechua monolingualism confined to remote highland enclaves; the 2017 census marked an increase in reported speakers from 3.36 million in 2007, countering earlier declines attributed to Spanish-dominant education policies.[63] Distribution remains uneven, with sierra departments accounting for over 80% of Quechua speakers, while Amazonian and coastal regions host negligible native populations, though transient labor migration introduces small pockets elsewhere.[66]Distribution in Bolivia

The Quechua people in Bolivia are predominantly located in the Andean highlands, with the highest concentrations in the central and southern departments of Potosí, Chuquisaca, and Cochabamba, where they form a significant portion of rural communities engaged in subsistence agriculture and herding. These regions feature high-altitude plateaus and valleys conducive to traditional crops like potatoes, quinoa, and maize, sustaining Quechua ayllus (kinship-based communities). Smaller populations extend into Oruro and northern Potosí, but Quechua presence diminishes in the western Altiplano dominated by Aymara groups and the eastern lowlands with Amazonian indigenous peoples.[58] According to Bolivia's 2012 National Census by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE), 1,281,116 individuals self-identified as Quechua, representing approximately 13% of the national population of 10.2 million at the time. Quechua was the first language for 1,680,384 people (16.75% of those aged 4 and older), with departmental breakdowns showing 54.4% of Potosí's population, 43% of Chuquisaca's, and 40% of Cochabamba's learning Quechua as their mother tongue. These figures reflect both ethnic self-identification and linguistic data, though overlap exists as many bilingual mestizos maintain Quechua cultural ties.[67][68][69] Urban migration has led to growing Quechua communities in cities like Cochabamba and Sucre, where rural-to-urban movement for economic opportunities has increased since the 1990s, diluting traditional rural distributions but preserving language use in markets and neighborhoods. No comprehensive census has occurred since 2012 due to logistical and political delays, but projections from INE and organizations like IWGIA suggest the Quechua population remains around 1.5-1.8 million as of 2023, stable in relative terms amid national growth to approximately 12.3 million, though intergenerational language shift toward Spanish poses risks to vitality in peripheral areas.[70][58]Distribution in Ecuador

The Kichwa, the Ecuadorian branch of the Quechua people, constitute the largest indigenous nationality in the country, with an estimated population of around 800,000 individuals organized into over 400 communities.[59] This figure aligns with self-identification data from indigenous organizations, though official language speaker counts from earlier censuses report approximately 527,000 Kichwa speakers, representing about 40% of the total indigenous linguistic diversity.[71] The Kichwa are subdivided into highland (Sierra) and Amazonian groups, with the former comprising the majority concentrated in the Andean regions and the latter in the eastern lowlands. In the Sierra, approximately 60% of Andean Kichwa reside in the central-northern provinces, including Imbabura (home to the prominent Otavalo and Caranqui subgroups), Pichincha (Quitu-Kara and Runa communities around Quito), Chimborazo (high indigenous density with Puruhá influences), Tungurahua (Salasaca and Chibuleo), Cotopaxi, and Bolívar.[72] Southern Sierra populations, about 7% of the Andean total, are found in Cañar (Kañari) and Azuay provinces, while smaller numbers, roughly 8%, have migrated to coastal areas and the Galápagos Islands.[72] Chimborazo Province stands out for its high concentration, where indigenous peoples, predominantly Kichwa, form nearly 38% of the local population.[71] Amazonian Kichwa communities, numbering around 55,000 to 109,000 based on speaker estimates, are distributed across provinces such as Napo (along the Napo River), Orellana, Pastaza (including Northern Pastaza and Sarayaku on the Bobonaza River), Sucumbíos, and parts of Morona Santiago.[73][74] These groups maintain semi-nomadic or riverine settlements, with key populations in Napo (over 46,000 speakers) and Orellana (about 30,000).[74] Recent trends indicate ongoing rural-to-urban migration, particularly among highland Kichwa, contributing to growing indigenous presence in cities like Quito and Otavalo, where nearly 30% of the population in some areas traces Kichwa roots.[75]Presence in Other Countries

Quechua communities exist in Argentina, primarily in the northern provinces of Santiago del Estero and Jujuy, where local dialects such as Santiagueño Quechua are spoken by an estimated 60,000 to 100,000 people.[76] These populations trace their roots to pre-colonial Andean expansions and maintain agricultural lifestyles intertwined with Spanish influences.[77] In Chile, Quechua speakers number around 8,200 individuals, mainly in the northern regions near the Bolivian border, often identifying with South Bolivian Quechua variants spoken by migrant or border communities of up to 15,000.[78][79] Their presence is limited compared to dominant indigenous groups like the Mapuche, with Quechua serving as a minority language in highland areas.[80] Colombia hosts smaller Quechua populations, estimated at a few thousand, concentrated in southern departments bordering Ecuador, where Inga Quechua dialects persist among indigenous groups totaling around 3,688 speakers per linguistic surveys.[2] These communities, part of broader Quechuan diaspora influences, face assimilation pressures but retain ties to Andean cultural practices.[81] Beyond these, negligible Quechua presences appear in other South American nations like Venezuela, stemming from migration rather than native settlement, with no significant demographic data reported.[82] Overall, these extraterritorial groups total under 200,000, underscoring the Quechua's core Andean distribution while highlighting diaspora dynamics.[49]Social Organization and Economy

Traditional Kinship and Community Structures

The ayllu serves as the foundational social and economic unit in traditional Quechua society, functioning as a corporate kin group that collectively owns and manages land through kinship ties spanning multiple generations.[83] This structure emphasizes bilateral descent, where affiliation traces through both paternal and maternal lines, often extending three to four generations with a patrilateral bias in practice.[84] Land rights within the ayllu are inalienable and redistributed among member households based on family size and needs, ensuring communal access to ecological niches via vertical control of resources from valleys to highlands.[85] Kinship terminology in Quechua communities distinguishes parallel cousins from cross-cousins, reflecting preferences for exogamous marriages outside the immediate ayllu to forge alliances while prohibiting unions within close kin groups.[86] Household units, typically comprising a nuclear family within the broader ayllu, operate under patriarchal authority where senior males oversee agricultural decisions and ritual obligations, though women hold significant roles in textile production, herding, and household economy.[87] Inheritance follows bilateral principles, with land parcels and livestock divided partibly among sons and daughters at marriage or upon parental death, supplemented by communal ayllu allocations to prevent fragmentation.[88] Community cohesion relies on reciprocal labor systems such as ayni (symmetrical exchange between kin) and minka (asymmetrical communal work for collective projects like irrigation or harvests), fostering interdependence and social obligations enforceable through customary sanctions.[89] Leadership within the ayllu vests in a kuraka or headman, selected for wisdom and lineage, who mediates disputes, represents the group externally, and coordinates with higher Inca-derived hierarchies in pre-colonial times.[85] These structures promoted resilience in the harsh Andean environment by pooling labor and resources, though colonial impositions and modern state interventions have eroded their autonomy in many regions.[90]Agricultural Practices and Subsistence Economy

The Quechua people's traditional agricultural practices center on subsistence farming adapted to the high-altitude Andean environment, where they cultivate a diverse array of crops including potatoes (with over 400 varieties preserved in some communities), quinoa, maize, and cañihua, often using intercropping, cover crops, and plot rotation to maintain soil fertility and biodiversity.[91][92] These methods support self-sufficiency within ayllu community systems, spanning multiple ecological zones from valleys to highlands to enable year-round production of tubers, grains, and legumes.[93] Key techniques include terracing steep slopes to create arable land, channeling water for irrigation, and constructing raised fields known as waru waru in the Lake Titicaca basin, where platforms up to 1.2 meters high and 2–20 meters wide are surrounded by canals for frost protection, flood control, and nutrient recycling from aquatic plants.[94][95][96] Originating over 2,000 years ago among pre-Inca groups and refined by the Inca, waru waru systems extend growing seasons and boost yields by up to 300% compared to flat fields in harsh conditions, as demonstrated in experimental revivals since the 1980s involving local Quechua farmers.[97][98] Livestock herding complements cropping, with llamas and alpacas raised for wool, meat, pack transport, and manure fertilizer, particularly in higher pastures where agriculture is limited; communities in regions like Ollagüe integrate pastoralism with minimal crop cultivation due to arid conditions.[99][7] This mixed economy emphasizes reciprocity and communal labor, such as minka work exchanges, sustaining household needs while minimizing external dependencies, though yields remain vulnerable to climate variability without modern inputs.[100]Modern Economic Adaptations and Challenges

Many Quechua communities have adapted to modern economic pressures through rural-to-urban migration, particularly in Peru since the 1980s, driven by armed conflicts, limited rural opportunities, and agricultural decline, leading migrants to informal urban sectors like construction, domestic work, and vending in cities such as Lima.[101] This migration often involves circular patterns where remittances support rural households, enabling diversification beyond subsistence farming into small-scale commerce or seasonal labor.[102] In Ecuador's highlands, Quichua (Quechua) farmers have increasingly taken up day labor in commercial agriculture to supplement incomes strained by land scarcity and market fluctuations.[103] Rural adaptations include leveraging cultural heritage for tourism, as seen in Peruvian Quechua villages where community-led initiatives promote homestays and guided treks, generating supplemental revenue while preserving traditional crafts like weaving and alpaca herding.[104] Agricultural practices incorporate resilient indigenous techniques, such as intercropping, crop rotation, and native potato varieties, which aid adaptation to variable climates in Andean regions of Peru and Ecuador.[105][91] Persistent challenges include high poverty rates and economic marginalization, with Quechua speakers in Peru comprising 60% of those lacking health service access as of 2014, exacerbated by language-based discrimination limiting urban job prospects.[106] Mining operations in southern Peru's "corridor" and Bolivia's highlands have displaced communities through land expropriation, water contamination, and health impacts, fueling conflicts where over one-third of development disputes affect indigenous groups, often prioritizing national exports over local benefits.[107][108] Climate variability compounds these issues, with droughts and erratic rainfall reducing crop yields and threatening herd viability, as observed in Peruvian Andean farms where traditional storage methods persist but fail against prolonged extremes.[109][110] Indigenous children also exhibit lower socioeconomic aspirations, perpetuating intergenerational poverty traps in Peru.[111]Cultural Practices

Material Culture and Technology

Quechua material culture emphasizes textiles produced through intricate weaving techniques using backstrap looms, primarily by women, with fibers from alpaca, llama, and sheep wool. These textiles, including luxury cumbi fabrics from fine alpaca fibers, served utilitarian, ceremonial, and trade purposes in pre-Columbian Andean societies.[112] Weaving remains a communal activity, often involving extended families and incorporating symbolic patterns that encode cultural knowledge.[113] Agricultural technology features the chakitaqlla, a foot plow adapted for highland soils, enabling tillage on steep terraces known as andenes that maximize arable land in the Andes. Quechua farmers continue employing these tools alongside raised fields and crop rotation systems, sustaining potato, quinoa, and maize cultivation despite challenging elevations above 3,000 meters.[114] Such methods, refined over millennia, support yields in regions with frost-prone microclimates.[115] Pottery production among Quechua groups, particularly in eastern Ecuadorian communities, relies on hand-coiling and open firing of local clays to create utilitarian vessels like drinking bowls and storage jars. These ceramics, decorated with incised or painted motifs, persist in daily use despite modern alternatives.[116] Pre-Columbian metallurgy in Quechua-influenced Andean cultures involved hammering and alloying copper with gold or silver for decorative items, such as tumi knives and jewelry, rather than utilitarian tools, reflecting symbolic rather than functional priorities. Limited to cold-working and annealing without bellows-driven smelting for iron, this technology prioritized aesthetic alloys over durable implements.[117] Traditional housing employs adobe bricks or stone with thatched roofs, constructed using basic tools like wooden hoes and clod breakers, adapted to seismic activity.[118]Traditional Attire and Symbolism

Quechua women typically wear the pollera, a voluminous pleated skirt woven from wool and often consisting of multiple layers, fastened at the waist with a wide chumpi belt that features intricate geometric patterns.[119] Over the shoulders, they drape the lliclla, a rectangular shawl or mantle pinned with a tupu (metal pin), which functions as a cloak, head covering, and carrier for infants or goods.[120] Headwear includes embroidered hats or monteras varying by region, such as the bowler-style hats adopted in some Bolivian and Peruvian communities since the early 20th century.[121] These garments are handwoven on backstrap looms using fibers from sheep, alpaca, or llama wool, dyed with natural pigments from plants like cochineal insects for red hues and minerals for earth tones.[112] Quechua men traditionally don a poncho—a rectangular woolen cloth folded and worn over the shoulders—for protection against high-altitude cold, paired with loose trousers, a shirt, and a woven ch'uspa pouch for carrying coca leaves used in rituals and daily sustenance.[122] Knitted chullo hats with earflaps provide warmth and display community-specific motifs, while belts or sashes secure the ensemble and signify marital status or role.[119] Footwear consists of ushtanku sandals made from untreated leather or woven fibers, suited to rugged Andean terrain.[112] Regional variations persist, with Bolivian Quechua favoring more layered polleras and Peruvian groups emphasizing finer alpaca weaves.[121] The symbolism embedded in Quechua attire reflects a cosmological worldview, with textile patterns encoding narratives of nature, ancestry, and reciprocity (ayni).[6] Common motifs include the inti (sun) for life-giving energy, ch'aska (stars) for guidance, llamas for communal bonds and fertility, and geometric designs like stepped crosses (chakana) symbolizing the integration of upper (hanan), middle (kay pacha), and lower (ukhu) worlds.[123] Colors hold significance—red evokes blood and vitality, black the fertile earth—while tocapu squares, inherited from Inca elites, denote status or protection against malevolent forces.[112] These elements, persisting from pre-Columbian times, serve as visual records of mythology and environmental harmony, with women as primary weavers transmitting knowledge across generations.[124] In contemporary contexts, such attire reinforces ethnic identity amid modernization, though synthetic materials occasionally supplement traditional ones.[120]Cuisine and Culinary Innovations

The Quechua people's cuisine relies on staples domesticated in the Andean highlands, including potatoes (Solanum tuberosum) and quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa), which provided reliable nutrition amid variable altitudes and climates. Potatoes, originating from wild species in the Andes, were selectively bred by Quechua and predecessor groups into over 4,000 varieties by pre-Columbian times, with ongoing cultivation preserving more than 2,000 cultivars in community-managed areas like Peru's Potato Park, established by seven Quechua communities in 2002 to safeguard agrobiodiversity against erosion from modern monocultures.[125] [126] Quinoa, domesticated approximately 5,000 years ago by Quechua- and Aymara-speaking peoples in regions spanning modern Bolivia and Peru, offered a complete protein source resilient to frost and drought, termed chisiya mama ("mother grain") in Quechua for its foundational role in diets and rituals.[127] [128] Culinary innovations emphasize preservation and efficient resource use, such as chuño, a freeze-drying process where potatoes are repeatedly frozen by night frosts, trampled to remove water, and sun-dried, yielding lightweight, storable products viable for up to five years without spoilage and suitable for high-altitude transport.[129] This technique, refined over millennia, minimized post-harvest losses in the absence of refrigeration and supported population growth by enabling surplus storage.[128] Similarly, pachamanca ("earth pot" in Quechua) represents an ancient communal cooking method using a pit lined with heated stones to slow-cook layered meats (e.g., guinea pig or llama), tubers like potatoes and oca, maize, and herbs such as huacatay, infusing flavors through earthen retention of heat and moisture for 4-6 hours.[130][131] Dishes often combine these elements simply, as in quinoa-based soups (sopa de quinua) thickened with potatoes or fermented potato pulp (tocosh), which imparts probiotic qualities through lactic fermentation lasting weeks.[132] These practices, documented in ethnographic studies of high-Andean (Allin Mikuy or "good food") traditions, underscore causal adaptations to environmental constraints—high UV exposure, thin soils, and seasonal frosts—prioritizing nutrient-dense, low-input foods over imported grains.[132][133] Modern Quechua communities continue these methods, integrating them into sustainable agroecology to counter biodiversity loss from industrial agriculture.[126]Mythology, Religion, and Worldview

The traditional religion of the Quechua people, rooted in pre-Inca Andean beliefs, centered on a polytheistic system honoring natural forces and ancestors through rituals and offerings. Central deities included Viracocha, regarded as the creator god who shaped the world and humanity, and Inti, the sun god considered the ancestor of Inca rulers and a source of life-giving energy.[134][135] Pachamama, the earth mother goddess, embodied fertility and sustenance, demanding respect through libations and sacrifices to ensure agricultural prosperity.[136] Other figures like Apus, spirits of mountains, and Mama Quilla, the moon goddess, were venerated for their roles in weather, tides, and protection.[36] Quechua cosmology divided existence into three interconnected realms: Hanan Pacha, the upper world of celestial beings and harmony; Kay Pacha, the earthly realm of human activity; and Uku Pacha, the inner or underworld associated with death and regeneration.[137] These planes, symbolized by the condor (sky), puma (earth), and serpent (underworld), reflected a worldview emphasizing balance and cyclical renewal rather than linear progress.[138] Sacred sites known as huacas—natural features like rocks or springs—served as portals for communion with these forces, where offerings of coca leaves, chicha (corn beer), or animal fat maintained reciprocity.[36] A core principle of Quechua worldview was ayni, a system of mutual reciprocity governing social and spiritual exchanges to sustain community and cosmic equilibrium.[139] This ethic extended to nature, where humans offered payment (ch'alla) to Pachamama for her bounty, fostering causal interdependence over exploitation.[140] Rituals reinforced this, such as communal feasts and divinations using coca leaves to interpret omens and align actions with supernatural will.[36] Following Spanish conquest in the 16th century, Quechua religion underwent forced Christianization, leading to widespread adoption of Roman Catholicism overlaid with indigenous elements.[89] Syncretism manifested in equating Catholic saints with Andean deities—Inti with the Christ child, for instance—and incorporating Pachamama rituals into festivals like Corpus Christi.[141] Despite official doctrine, traditional beliefs persisted covertly, with many Quechua viewing the Christian God as a supreme huaca while maintaining offerings to earth spirits for practical efficacy.[142] In contemporary times, this hybrid faith prevails, though evangelical Protestantism has gained ground in some communities, challenging syncretic practices.[143]