Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Romanization of Japanese

View on WikipediaThis article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (February 2021) |

|

| Japanese writing |

|---|

| Components |

| Uses |

| Transliteration |

The romanization of Japanese is the use of Latin script to write the Japanese language.[1] This method of writing is sometimes referred to in Japanese as rōmaji (ローマ字; lit. 'Roman letters', [ɾoːma(d)ʑi] ⓘ or [ɾoːmaꜜ(d)ʑi]).

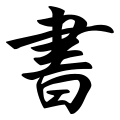

Japanese is normally written in a combination of logographic characters borrowed from Chinese (kanji) and syllabic scripts (kana) that also ultimately derive from Chinese characters.

There are several different romanization systems. The three main ones are Hepburn romanization, Kunrei-shiki romanization (ISO 3602) and Nihon-shiki romanization (ISO 3602 Strict). Variants of the Hepburn system are the most widely used.

Romanized Japanese may be used in any context where Japanese text is targeted at non-Japanese speakers who cannot read kanji or kana, such as for names on street signs and passports and in dictionaries and textbooks for foreign learners of the language. It is also used to transliterate Japanese terms in text written in English (or other languages that use the Latin script) on topics related to Japan, such as linguistics, literature, history, and culture.

All Japanese who have attended elementary school since World War II have been taught to read and write romanized Japanese. Therefore, almost all Japanese can read and write Japanese by using rōmaji. However, it is extremely rare in Japan to use it to write Japanese (except as an input tool on a computer or for special purposes such as logo design), and most Japanese are more comfortable in reading kanji and kana.

History

[edit]The earliest Japanese romanization system was based on Portuguese orthography. It was developed c. 1548 by a Japanese Catholic named Anjirō.[2][citation needed] Jesuit priests used the system in a series of printed Catholic books so that missionaries could preach and teach their converts without learning to read Japanese orthography. The most useful of these books for the study of early modern Japanese pronunciation and early attempts at romanization was the Nippo Jisho, a Japanese–Portuguese dictionary written in 1603. In general, the early Portuguese system was similar to Nihon-shiki in its treatment of vowels. Some consonants were transliterated differently: for instance, the /k/ consonant was rendered, depending on context, as either c or q, and the /ɸ/ consonant (now pronounced /h/, except before u) as f; and so Nihon no kotoba ("The language of Japan") was spelled Nifon no cotoba. The Jesuits also printed some secular books in romanized Japanese, including the first printed edition of the Japanese classic The Tale of the Heike, romanized as Feiqe no monogatari, and a collection of Aesop's Fables (romanized as Esopo no fabulas). The latter continued to be printed and read after the suppression of Christianity in Japan (Chibbett, 1977).

From the mid-19th century onward, several systems were developed, culminating in the Hepburn system, named after James Curtis Hepburn who used it in the third edition of his Japanese–English dictionary, published in 1887. The Hepburn system included representation of some sounds that have since changed. For example, Lafcadio Hearn's book Kwaidan shows the older kw- pronunciation; in modern Hepburn romanization, this would be written Kaidan (lit. 'ghost tales').[citation needed]

As a replacement for the Japanese writing system

[edit]In the Meiji era (1868–1912), some Japanese scholars advocated abolishing the Japanese writing system entirely and using rōmaji instead. The Nihon-shiki romanization was an outgrowth of that movement. Several Japanese texts were published entirely in rōmaji during this period, but it failed to catch on. Later, in the early 20th century, some scholars devised syllabary systems with characters derived from Latin (rather like the Cherokee syllabary) that were even less popular since they were not based on any historical use of the Latin script.

Today, the use of Nihon-shiki for writing Japanese is advocated by the Oomoto sect[3] and some independent organizations.[4] During the Allied occupation of Japan, the government of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP) made it official policy to romanize Japanese. However, that policy failed and a more moderate attempt at Japanese script reform followed.

Modern systems

[edit]

Hepburn

[edit]Hepburn romanization generally follows English phonology with Romance vowels. It is an intuitive method of showing Anglophones the pronunciation of a word in Japanese. It was standardized in the United States as American National Standard System for the Romanization of Japanese (Modified Hepburn), but that status was abolished on October 6, 1994. Hepburn is the most common romanization system in use today, especially in the English-speaking world.

The Revised Hepburn system of romanization uses a macron to indicate some long vowels and an apostrophe to note the separation of easily confused phonemes (usually, syllabic n ん from a following naked vowel or semivowel). For example, the name じゅんいちろう is written with the kana characters ju-n-i-chi-ro-u, and romanized as Jun'ichirō in Revised Hepburn. Without the apostrophe, it would not be possible to distinguish this correct reading from the incorrect ju-ni-chi-ro-u (じゅにちろう). This system is widely used in Japan and among foreign students and academics.

Nihon-shiki

[edit]Nihon-shiki romanization was originally invented as a method for Japanese to write their own language in Latin characters, rather than to transcribe it for Westerners as Hepburn was. It strictly follows the Japanese syllabary, with no adjustments for changes in pronunciation. It has also been standardized as ISO 3602 Strict. Also known as Nippon-shiki, rendered in the Nihon-shiki style of romanization the name is either Nihon-siki or Nippon-siki.

Kunrei-shiki

[edit]Kunrei-shiki romanization is a slightly modified version of Nihon-shiki which eliminates differences between the kana syllabary and modern pronunciation. For example, the characters づ and ず are pronounced identically in modern Japanese, and thus Kunrei-shiki and Hepburn ignore the difference in kana and represent the sound in the same way (zu). Nihon-shiki, on the other hand, will romanize づ as du, but ず as zu. Similarly for the pair じ and ぢ, they are both zi in Kunrei-shiki and ji in Hepburn, but are zi and di respectively in Nihon-shiki. See the table below for full details.

Kunrei-shiki has been standardized by the Japanese Government and the International Organization for Standardization as ISO 3602. Kunrei-shiki is taught to Japanese elementary school students in their fourth year of education.

Written in Kunrei-shiki, the name of the system would be rendered Kunreisiki.

Other variants

[edit]It is possible to elaborate these romanizations to enable non-native speakers to pronounce Japanese words more correctly. Typical additions include tone marks to note the Japanese pitch accent and diacritic marks to distinguish phonological changes, such as the assimilation of the moraic nasal /ɴ/ (see Japanese phonology).

JSL

[edit]JSL is a romanization system based on Japanese phonology, designed using the linguistic principles used by linguists in designing writing systems for languages that do not have any. It is a purely phonemic system, using exactly one symbol for each phoneme, and marking the pitch accent using diacritics. It was created for Eleanor Harz Jorden's system of Japanese language teaching. Its principle is that such a system enables students to internalize the phonology of Japanese better. Since it does not have any of the other systems' advantages for non-native speakers, and the Japanese already have a writing system for their language, JSL is not widely used outside the educational environment.

Non-standard romanization

[edit]In addition to the standardized systems above, there are many variations in romanization, used either for simplification, in error or confusion between different systems, or for deliberate stylistic reasons.

Notably, the various mappings that Japanese input methods use to convert keystrokes on a Roman keyboard to kana often combine features of all of the systems; when used as plain text rather than being converted, these are usually known as wāpuro rōmaji. (Wāpuro is a blend of wādo purosessā word processor.) Unlike the standard systems, wāpuro rōmaji requires no characters from outside the ASCII character set.

While there may be arguments in favour of some of these variant romanizations in specific contexts, their use, especially if mixed, leads to confusion when romanized Japanese words are indexed. This confusion never occurs when inputting Japanese characters with a word processor, because input Latin letters are transliterated into Japanese kana as soon as the IME processes what character is input.

Dzu

[edit]A common practice is to romanize づ as dzu, allowing to distinguish it from both ドゥ du and ず zu.[citation needed] For example, it can be seen in the style of romanization Google Translate adheres to. It is not to be conflated with the older form of Hepburn romanization, which used dzu for both ず and づ.[5]

Long vowels

[edit]In addition, the following three "non-Hepburn rōmaji" (非ヘボン式ローマ字, hi-Hebon-shiki rōmaji) methods of representing long vowels are authorized by the Japanese Foreign Ministry for use in passports.[6]

- oh for おお or おう (Hepburn ō).

- oo for おお or おう. This is valid JSL romanization. For Hepburn romanization, it is not a valid romanization if the long vowel belongs within a single word.

- ou for おう. This is also an example of wāpuro rōmaji.

Example words written in each romanization system

[edit]| English | Japanese | Kana spelling | Romanization | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revised Hepburn | Kunrei-shiki | Nihon-shiki | |||

| Roman characters | ローマ字 | ローマじ | rōmaji | rômazi | rômazi |

| Mount Fuji | 富士山 | ふじさん | Fujisan | Huzisan | Huzisan |

| tea | お茶 | おちゃ | ocha | otya | otya |

| governor | 知事 | ちじ | chiji | tizi | tizi |

| to shrink | 縮む | ちぢむ | chijimu | tizimu | tidimu |

| to continue | 続く | つづく | tsuzuku | tuzuku | tuduku |

Differences among romanizations

[edit]This chart shows in full the three main systems for the romanization of Japanese: Hepburn, Nihon-shiki and Kunrei-shiki:

| Hiragana | Katakana | Hepburn | Nihon-shiki | Kunrei-shiki | IPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| あ | ア | a | |||

| い | イ | i | |||

| う | ウ | u | ɯ | ||

| え | エ | e | |||

| お | オ | o | |||

| か | カ | ka | |||

| き | キ | ki | kʲi | ||

| く | ク | ku | kɯ | ||

| け | ケ | ke | |||

| こ | コ | ko | |||

| きゃ | キャ | kya | kʲa | ||

| きゅ | キュ | kyu | kʲɯ | ||

| きょ | キョ | kyo | kʲo | ||

| さ | サ | sa | |||

| し | シ | shi | si | ɕi | |

| す | ス | su | sɯ | ||

| せ | セ | se | |||

| そ | ソ | so | |||

| しゃ | シャ | sha | sya | ɕa | |

| しゅ | シュ | shu | syu | ɕɯ | |

| しょ | ショ | sho | syo | ɕo | |

| た | タ | ta | |||

| ち | チ | chi | ti | tɕi | |

| つ | ツ | tsu | tu | tsɯ | |

| て | テ | te | |||

| と | ト | to | |||

| ちゃ | チャ | cha | tya | tɕa | |

| ちゅ | チュ | chu | tyu | tɕɯ | |

| ちょ | チョ | cho | tyo | tɕo | |

| な | ナ | na | |||

| に | ニ | ni | ɲi | ||

| ぬ | ヌ | nu | nɯ | ||

| ね | ネ | ne | |||

| の | ノ | no | |||

| にゃ | ニャ | nya | ɲa | ||

| にゅ | ニュ | nyu | ɲɯ | ||

| にょ | ニョ | nyo | ɲo | ||

| は | ハ | ha | |||

| ひ | ヒ | hi | çi | ||

| ふ | フ | fu | hu | ɸɯ | |

| へ | ヘ | he | |||

| ほ | ホ | ho | |||

| ひゃ | ヒャ | hya | ça | ||

| ひゅ | ヒュ | hyu | çɯ | ||

| ひょ | ヒョ | hyo | ço | ||

| ま | マ | ma | |||

| み | ミ | mi | mʲi | ||

| む | ム | mu | mɯ | ||

| め | メ | me | |||

| も | モ | mo | |||

| みゃ | ミャ | mya | mʲa | ||

| みゅ | ミュ | myu | mʲɯ | ||

| みょ | ミョ | myo | mʲo | ||

| や | ヤ | ya | ja | ||

| ゆ | ユ | yu | jɯ | ||

| よ | ヨ | yo | jo | ||

| ら | ラ | ra | ɾa | ||

| り | リ | ri | ɾʲi | ||

| る | ル | ru | ɾɯ | ||

| れ | レ | re | ɾe | ||

| ろ | ロ | ro | ɾo | ||

| りゃ | リャ | rya | ɾʲa | ||

| りゅ | リュ | ryu | ɾʲu | ||

| りょ | リョ | ryo | ɾʲo | ||

| わ | ワ | wa | wa~ɰa | ||

| ゐ | ヰ | i | wi | i | |

| ゑ | ヱ | e | we | e | |

| を | ヲ | o | wo | o | |

| ゐゃ | ヰャ | iya | wya | iya | |

| ゐゅ | ヰュ | iyu | wyu | iyu | |

| ゐょ | ヰョ | iyo | wyo | iyo | |

| ん | ン | n-n'(-m) | n-n' | m~n~ŋ~ɴ | |

| が | ガ | ga | |||

| ぎ | ギ | gi | gʲi | ||

| ぐ | グ | gu | gɯ | ||

| げ | ゲ | ge | |||

| ご | ゴ | go | |||

| ぎゃ | ギャ | gya | gʲa | ||

| ぎゅ | ギュ | gyu | gʲɯ | ||

| ぎょ | ギョ | gyo | gʲo | ||

| ざ | ザ | za | za~dza | ||

| じ | ジ | ji | zi | ʑi~dʑi | |

| ず | ズ | zu | zɯ~dzɯ | ||

| ぜ | ゼ | ze | ze~dze | ||

| ぞ | ゾ | zo | zo~dzo | ||

| じゃ | ジャ | ja | zya | ʑa~dʑa | |

| じゅ | ジュ | ju | zyu | ʑɯ~dʑɯ | |

| じょ | ジョ | jo | zyo | ʑo~dʑo | |

| だ | ダ | da | |||

| ぢ | ヂ | ji | di | zi | ʑi~dʑi |

| づ | ヅ | zu | du | zu | zɯ~dzɯ |

| で | デ | de | |||

| ど | ド | do | |||

| ぢゃ | ヂャ | ja | dya | zya | ʑa~dʑa |

| ぢゅ | ヂュ | ju | dyu | zyu | ʑɯ~dʑɯ |

| ぢょ | ヂョ | jo | dyo | zyo | ʑo~dʑo |

| ば | バ | ba | |||

| び | ビ | bi | bʲi | ||

| ぶ | ブ | bu | bɯ | ||

| べ | ベ | be | |||

| ぼ | ボ | bo | |||

| びゃ | ビャ | bya | bʲa | ||

| びゅ | ビュ | byu | bʲɯ | ||

| びょ | ビョ | byo | bʲo | ||

| ぱ | パ | pa | |||

| ぴ | ピ | pi | pʲi | ||

| ぷ | プ | pu | pɯ | ||

| ぺ | ペ | pe | |||

| ぽ | ポ | po | |||

| ぴゃ | ピャ | pya | pʲa | ||

| ぴゅ | ピュ | pyu | pʲɯ | ||

| ぴょ | ピョ | pyo | pʲo | ||

| ゔ | ヴ | vu | βɯ | ||

This chart shows the significant differences among them. Despite the International Phonetic Alphabet, the /j/ sound in や, ゆ, and よ are never romanized with the letter J.

| Kana | Revised Hepburn | Nihon-shiki | Kunrei-shiki |

|---|---|---|---|

| うう | ū | û | |

| おう, おお | ō | ô | |

| し | shi | si | |

| しゃ | sha | sya | |

| しゅ | shu | syu | |

| しょ | sho | syo | |

| じ | ji | zi | |

| じゃ | ja | zya | |

| じゅ | ju | zyu | |

| じょ | jo | zyo | |

| ち | chi | ti | |

| つ | tsu | tu | |

| ちゃ | cha | tya | |

| ちゅ | chu | tyu | |

| ちょ | cho | tyo | |

| ぢ | ji | di | zi |

| づ | zu | du | zu |

| ぢゃ | ja | dya | zya |

| ぢゅ | ju | dyu | zyu |

| ぢょ | jo | dyo | zyo |

| ふ | fu | hu | |

| ゐ | i | wi | i |

| ゑ | e | we | e |

| を | o | wo | o |

| ん | n, n' ( m) | n n' | |

Spacing

[edit]Japanese is written without spaces between words, and in some cases, such as compounds, it may not be completely clear where word boundaries should lie, resulting in varying romanization styles. For example, 結婚する, meaning "to marry", and composed of the noun 結婚 (kekkon, "marriage") combined with する (suru, "to do"), is romanized as one word kekkonsuru by some authors but two words kekkon suru by others. Particles, like the possessive particle の in 君の犬 ("your dog"), are sometimes joined with the preceding term (kimino inu), or written as separate words (kimi no inu).

Kana without standardized forms of romanization

[edit]There is no universally accepted style of romanization for the smaller versions of the vowels and y-row kana when used outside the normal combinations (きゃ, きょ, ファ etc.), nor for the sokuon or small tsu kana っ/ッ when it is not directly followed by a consonant. Although these are usually regarded as merely phonetic marks or diacritics, they do sometimes appear on their own, such as at the end of sentences, in exclamations, or in some names. The detached sokuon, representing a final glottal stop in exclamations, is sometimes represented as an apostrophe or as t; for example, あっ! might be written as a'! or at!.[citation needed]

Historical romanizations

[edit]- 1603: Vocabvlario da Lingoa de Iapam (1603)

- 1604: Arte da Lingoa de Iapam (1604–1608)

- 1620: Arte Breve da Lingoa Iapoa (1620)

- 1848: Kaisei zoho Bango sen[7] (1848)

| あ | い | う | え | お | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1603 | a | i, j, y | v, u | ye | vo, uo | ||||

| 1604 | i | v | vo | ||||||

| 1620 | y | ||||||||

| 1848 | i | woe | e | o | |||||

| か | き | く | け | こ | きゃ | きょ | くゎ | ||

| 1603 | ca | qi, qui | cu, qu | qe, que | co | qia | qio, qeo | qua | |

| 1604 | qui | que | quia | quio | |||||

| 1620 | ca, ka | ki | cu, ku | ke | kia | kio | |||

| 1848 | ka | kfoe | ko | ||||||

| が | ぎ | ぐ | げ | ご | ぎゃ | ぎゅ | ぎょ | ぐゎ | |

| 1603 | ga | gui | gu, gv | gue | go | guia | guiu | guio | gua |

| 1604 | gu | ||||||||

| 1620 | ga, gha | ghi | gu, ghu | ghe | go, gho | ghia | ghiu | ghio | |

| 1848 | ga | gi | gfoe | ge | go | ||||

| さ | し | す | せ | そ | しゃ | しゅ | しょ | ||

| 1603 | sa | xi | su | xe | so | xa | xu | xo | |

| 1604 | |||||||||

| 1620 | |||||||||

| 1848 | si | sfoe | se | ||||||

| ざ | じ | ず | ぜ | ぞ | じゃ | じゅ | じょ | ||

| 1603 | za | ii, ji | zu | ie, ye | zo | ia, ja | iu, ju | io, jo | |

| 1604 | ji | ia | ju | jo | |||||

| 1620 | ie | iu | io | ||||||

| 1848 | zi | zoe | ze | ||||||

| た | ち | つ | て | と | ちゃ | ちゅ | ちょ | ||

| 1603 | ta | chi | tçu | te | to | cha | chu | cho | |

| 1604 | |||||||||

| 1620 | |||||||||

| 1848 | tsi | tsoe | |||||||

| だ | ぢ | づ | で | ど | ぢゃ | ぢゅ | ぢょ | ||

| 1603 | da | gi | zzu | de | do | gia | giu | gio | |

| 1604 | dzu | ||||||||

| 1620 | |||||||||

| 1848 | dsi | dsoe | |||||||

| な | に | ぬ | ね | の | にゃ | にゅ | にょ | ||

| 1603 | na | ni | nu | ne | no | nha | nhu, niu | nho, neo | |

| 1604 | nha | nhu | nho | ||||||

| 1620 | |||||||||

| 1848 | noe | ||||||||

| は | ひ | ふ | へ | ほ | ひゃ | ひゅ | ひょ | ||

| 1603 | fa | fi | fu | fe | fo | fia | fiu | fio, feo | |

| 1604 | fio | ||||||||

| 1620 | |||||||||

| 1848 | ha | hi | foe | he | ho | ||||

| ば | び | ぶ | べ | ぼ | びゃ | びゅ | びょ | ||

| 1603 | ba | bi | bu | be | bo | bia | biu | bio, beo | |

| 1604 | |||||||||

| 1620 | bia | biu | |||||||

| 1848 | boe | ||||||||

| ぱ | ぴ | ぷ | ぺ | ぽ | ぴゃ | ぴゅ | ぴょ | ||

| 1603 | pa | pi | pu | pe | po | pia | pio | ||

| 1604 | |||||||||

| 1620 | pia | ||||||||

| 1848 | poe | ||||||||

| ま | み | む | め | も | みゃ | みょ | |||

| 1603 | ma | mi | mu | me | mo | mia, mea | mio, meo | ||

| 1604 | |||||||||

| 1620 | mio | ||||||||

| 1848 | moe | ||||||||

| や | ゆ | よ | |||||||

| 1603 | ya | yu | yo | ||||||

| 1604 | |||||||||

| 1620 | |||||||||

| ら | り | る | れ | ろ | りゃ | りゅ | りょ | ||

| 1603 | ra | ri | ru | re | ro | ria, rea | riu | rio, reo | |

| 1604 | rio | ||||||||

| 1620 | riu | ||||||||

| 1848 | roe | ||||||||

| わ | ゐ | ゑ | を | ||||||

| 1603 | va, ua | vo, uo | |||||||

| 1604 | va | y | ye | vo | |||||

| 1620 | |||||||||

| 1848 | wa | wi | ije, ÿe | wo | |||||

| ん | |||||||||

| 1603 | n, m, ˜ (tilde) | ||||||||

| 1604 | n | ||||||||

| 1620 | n, m | ||||||||

| っ | |||||||||

| 1603 | -t, -cc-, -cch-, -cq-, -dd-, -pp-, -ss-, -tt, -xx-, -zz- | ||||||||

| 1604 | -t, -cc-, -cch-, -pp-, -cq-, -ss-, -tt-, -xx- | ||||||||

| 1620 | -t, -cc-, -cch-, -pp-, -ck-, -cq-, -ss-, -tt-, -xx- | ||||||||

Roman letter names in Japanese

[edit]The list below shows the Japanese readings of letters in Katakana, for spelling out words, or in acronyms. For example, NHK is read enu-eichi-kē (エヌ・エイチ・ケー). These are the standard names, based on the British English letter names (so Z is from zed, not zee), but in specialized circumstances, names from other languages may also be used. For example, musical keys are often referred to by the German names, so that B♭ is called bē (べー) from German B (German: [beː]).

- A; ē (エー, sometimes pronounced ei, エイ)

- B; bī (ビー)

- C; shī (シー, sometimes pronounced sī, スィー)

- D; dī (ディー, sometimes pronounced dē, デー)

- E; ī (イー)

- F; efu (エフ)

- G; jī (ジー)

- H; eichi or etchi (エイチ or エッチ)

- I; ai (アイ)

- J; jē (ジェー, sometimes pronounced jei, ジェイ)

- K; kē (ケー, sometimes pronounced kei, ケイ)

- L; eru (エル)

- M; emu (エム)

- N; enu (エヌ)

- O; ō (オー)

- P; pī (ピー)

- Q; kyū (キュー)

- R; āru (アール)

- S; esu (エス)

- T; tī (ティー)

- U; yū (ユー)

- V; bui or vī (ブイ or ヴィー)

- W; daburyū (ダブリュー)

- X; ekkusu (エックス)

- Y; wai (ワイ)

- Z; zetto (ゼット)

Sources: Kōjien (7th edition), Daijisen (online version).

Note: Daijisen does not mention the name vī, while Kōjien does.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Walter Crosby Eells (May 1952). "Language Reform in Japan". The Modern Language Journal. 36 (5): 210–213. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.1952.tb06122.x. JSTOR 318376.

- ^ "What is Romaji? Everything you need to know about Romaji Everything you need to know about Romaji". 17 July 2020.

- ^ "Oomoto.or.jp". Oomoto.or.jp. 2000-02-07. Retrieved 2011-02-25.

- ^ "Age.ne.jp". Age.ne.jp. Retrieved 2011-02-25.

- ^ "A Japanese-English and English-Japanese dictionary. By J. C. Hepburn".

- ^ "ヘボン式ローマ字と異なる場合(非ヘボン式ローマ字)". Kanagawa Prefectural Government. Retrieved 2018-08-19.

- ^ "Kaisei zoho Bango sen. (Lager image 104-002) | Japan-Netherlands Exchange in the Edo Period".

Sources

[edit]- Chibbett, David (1977). The History of Japanese Printing and Book Illustration. Kodansha International Ltd. ISBN 0-87011-288-0.

- Jun'ichirō Kida (紀田順一郎, Kida Jun'ichirō) (1994). Nihongo Daihakubutsukan (日本語大博物館) (in Japanese). Just System (ジャストシステム, Jasuto Shisutem). ISBN 4-88309-046-9.

- Tadao Doi (土井忠生) (1980). Hōyaku Nippo Jisho (邦訳日葡辞書) (in Japanese). Iwanami Shoten (岩波書店).

- Tadao Doi (土井忠生) (1955). Nihon Daibunten (日本大文典) (in Japanese). Sanseido (三省堂).

- Mineo Ikegami (池上岑夫) (1993). Nihongo Shōbunten (日本語小文典) (in Japanese). Iwanami Shoten (岩波書店).

- Hiroshi Hino (日埜博) (1993). Nihon Shōbunten (日本小文典) (in Japanese). Shin-Jinbutsu-Ôrai-Sha (新人物往来社).

Further reading

[edit]- (in Japanese) Hishiyama, Takehide (菱山 剛秀 Hishiyama Takehide), Topographic Department (測図部). "Romanization of Geographical Names in Japan." (地名のローマ字表記) (Archive) Geospatial Information Authority of Japan.

External links

[edit] Media related to Romanization of Japanese at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Romanization of Japanese at Wikimedia Commons- "Rōmaji sōdan shitsu" ローマ字相談室 (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2018-03-06. An extensive collection of materials relating to rōmaji, including standards documents and HTML versions of Hepburn's original dictionaries.

- The rōmaji conundrum by Andrew Horvat contains a discussion of the problems caused by the variety of confusing romanization systems in use in Japan today.

Romanization of Japanese

View on GrokipediaHistory

Early Efforts and Motivations

The earliest efforts to romanize Japanese began in the mid-16th century with the arrival of Portuguese Jesuit missionaries in Japan, starting in 1549 under Francis Xavier. These missionaries, seeking to learn the language for evangelical purposes, developed the first systematic romanization based on Portuguese orthography to transcribe Japanese sounds into the Latin alphabet, facilitating language instruction and the creation of religious materials. Anjirō, a Japanese convert who assisted Xavier after meeting him in 1547, helped with early language studies during time in Goa, contributing to these missionary efforts.[6][1] This phonetic approach reflected Portuguese influences, where vowels were rendered without initial length distinctions and nasals were emphasized (e.g., "Nangasaqui" for Nagasaki), diverging from Japanese phonology's simpler five-vowel system and lack of certain consonants like /f/ or /l/. The system prioritized missionary utility over precise phonological matching, often incorporating Latin-based conventions that suited European pronunciation. A seminal work emerged from these efforts: João Rodrigues' Arte da Lingoa de Iapam (1604–1608), a comprehensive Portuguese-language grammar of Japanese that included detailed romanized examples and pronunciation rules, serving as both a teaching tool and a record of early linguistic analysis.[7][8][9] Following Japan's seclusion policy after 1639, romanization efforts waned until the mid-19th century, when Commodore Matthew Perry's expeditions in 1853–1854 compelled the country to open to Western trade and diplomacy, spurring scholarly interest in Japanese language transcription. American missionary James Curtis Hepburn, arriving in 1859, motivated by the need to aid English-speaking learners and missionaries, compiled A Japanese and English Dictionary (1867), which introduced a more systematic romanization tailored for non-Portuguese speakers, emphasizing readability and consistency with English phonetics. This dictionary marked a pivotal step in standardizing romanization amid growing international exchange.[10][11]Development as a Writing Aid

During the Meiji period (1868–1912), Japanese intellectuals and reformers proposed romanization (rōmaji) as a means to modernize the nation and boost literacy rates by replacing the complex kanji and kana systems with a simpler alphabetic script, viewing it as essential for rapid education and communication in an industrializing society.[12] These efforts were driven by the need to align Japan with Western technological and educational standards, with early advocates arguing that rōmaji would democratize access to knowledge and facilitate international exchange.[13] One notable example was the 1873 proposal by educator Mori Arinori, who suggested radical script reform, including elements that influenced later rōmaji advocacy, to streamline learning and promote national unity.[13] In 1885, the Romaji Club (Rōmaji Kai) was established by a group of Japanese scholars and foreign residents to promote Hepburn romanization as a practical tool for education and telegraphy, conducting surveys and publishing materials to demonstrate its utility in simplifying written Japanese.[12] The club emphasized rōmaji's role in aiding literacy among the masses and in technical fields like international correspondence. By 1900, the Japanese government initiated experimental programs in select elementary schools to test rōmaji instruction, aiming to assess its potential as an auxiliary system for teaching kana and kanji more efficiently.[13] Debates intensified around rōmaji's use as a transitional "bridge" to mastering traditional scripts, particularly during the 1887 Genbun Itchi movement, which sought to unify spoken and written Japanese and incorporated rōmaji proponents who saw it as a phonetic aid to colloquial styles.[14] Legislative efforts to mandate rōmaji, including a failed 1900 bill to integrate it into national curricula and a 1946 proposal amid postwar reforms, highlighted ongoing tensions between simplification advocates and traditionalists concerned about cultural loss.[14] Following World War II, the General Headquarters (GHQ) of the Allied occupation encouraged rōmaji adoption to foster democratic literacy and accessibility, viewing it as a tool to empower citizens in a rebuilding society, though these initiatives ultimately faced resistance and were scaled back.[13]Evolution of Standardized Systems

The formalization of Japanese romanization systems gained momentum in the late 19th century amid Meiji-era efforts to modernize education and international communication. In 1885, physicist Aikitsu Tanakadate developed Nihon-shiki romanization, a phonemic system aligned closely with Japanese pronunciation principles, under the auspices of the Rōmaji-kai society he founded.[15] This system emphasized strict correspondence to kana orthography, serving as a foundation for subsequent domestic standards. The Hepburn system, originally devised by James Curtis Hepburn in 1867 and revised in 1886, saw growing adoption in international and diplomatic contexts during the late Meiji era, reflecting its accessibility to English speakers.[16] The early 20th century saw increased government involvement in standardizing romanization to support linguistic reform and national identity. Modifications to Nihon-shiki were discussed by educational committees in the early 20th century to simplify certain representations while retaining phonemic fidelity, though official endorsement came later.[15] A pivotal moment came in 1930 when Japan's Ministry of Education established a special commission to evaluate competing systems; its 1931 report favored Hepburn for its intuitive appeal to foreigners but ultimately influenced the 1937 cabinet ordinance adopting Kunrei-shiki as the national standard, balancing domestic phonology with practical modifications.[16] Internationally, this trajectory continued with the 1977 publication of ISO 3602, which endorsed Kunrei-shiki as the global standard for romanizing Japanese kana, promoting consistency in technical and scholarly applications.[17] Post-World War II occupation forces reshaped these standards amid broader language policy reforms. In 1946, the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP) issued a directive mandating Hepburn romanization for official government documents and communications, prioritizing intelligibility for English-speaking administrators during the Allied occupation.[16] This policy lacked enduring legal force, however, and upon Japan's sovereignty restoration, a 1954 cabinet ordinance reaffirmed Kunrei-shiki with minor adjustments, establishing it as the domestic official system despite persistent Hepburn usage in practice.[16] Concurrently, American linguist Eleanor Jorden developed the Japan Statistical Language (JSL) romanization in 1954 for U.S. military and linguistic training programs, introducing diacritics to distinguish pitch accent and morpheme boundaries for analytical purposes. By 1986, reflecting evolving international norms, the Japanese government allowed Hepburn romanization as an option for names on passports, accommodating global readability while upholding the 1954 law for other contexts.[18] In August 2025, a government panel recommended revising the official rules for the first time since 1954 to incorporate Hepburn-style elements, aiming to enhance international readability while maintaining core Kunrei principles.[5]Standard Systems

Hepburn Romanization

Hepburn romanization, also known as Hebon-shiki (ヘボン式), is a system for transcribing Japanese into the Latin alphabet, developed by American Presbyterian missionary and physician James Curtis Hepburn. It was first outlined in Hepburn's A Japanese and English Dictionary: With an English and Japanese Index, published in 1867, which marked the initial modern effort to standardize Japanese romanization for Western learners. The system underwent revisions, with the 1887 edition introducing refinements to better align with English phonetics, and the 1903 edition further simplifying certain representations.[19][18][20] The system operates on a moraic basis, dividing Japanese text into its phonetic units (morae) while prioritizing English-like spellings to approximate pronunciation for non-native speakers. For instance, the kana し is rendered as shi rather than si, and つ as tsu rather than tu, reflecting familiar English consonant-vowel combinations. Long vowels are indicated with macrons, such as ō for おう or ょう (e.g., kyō for きょう), and apostrophes are used to separate glides or prevent misreading, as in honya (本屋) to distinguish the moraic n from a syllabic one. Voiced sounds follow intuitive patterns, with じ transcribed as ji to evoke the affricate [dʑi]. These conventions make Hepburn particularly accessible for English speakers, contrasting with more phonemically strict systems like Kunrei-shiki, which prioritize Japanese phonological structure for domestic use.[21][22][23] Hepburn features two primary variants: the traditional form from the 1887 edition, which included representations like ye and yi for certain historical pronunciations (e.g., yefu for 衣), and the revised (or modified) form from 1903 onward, which streamlined these to e and i for simplicity and alignment with modern speech. The modified variant, further refined in the 1954 third edition of Kenkyusha's New Japanese-English Dictionary, eliminated archaic elements and standardized voiced consonant treatments, such as consistently using ji for both じ and ぢ in contemporary contexts. This revised system became the basis for the modified Hepburn adopted by institutions like the Library of Congress.[3][24] Hepburn romanization dominates in Western publications, academic works, and English-language media due to its phonetic intuitiveness. It is the standard in major dictionaries like Kenkyusha's New Japanese-English Dictionary, which has influenced global lexicography since its early editions, and is employed by over 90% of English-oriented Japanese resources in libraries and databases. In international contexts, including signage for tourists and subtitles in films, Hepburn's prevalence ensures consistent readability for non-Japanese audiences.[3][25][26]Kunrei-shiki Romanization

Kunrei-shiki Romanization, also known as the Monbushō or Cabinet system, originated as a practical adaptation of the earlier Nihon-shiki system, with its core framework developed under the auspices of Japan's Ministry of Education in the early 20th century and formally announced in a modified form on September 21, 1937, through a cabinet ordinance. This derivation aimed to simplify romanization for domestic educational and administrative purposes while maintaining a close alignment with the phonetic structure of modern standard Japanese. The system received further refinement post-World War II and was legally mandated as the official standard on December 9, 1954, via Cabinet Order No. 1, which prescribed its use for general written expressions of Japanese in official settings.[27][28] The defining principle of Kunrei-shiki is its strict one-to-one mapping between individual kana symbols and Roman letters, based on the traditional gojūon syllable chart, to facilitate straightforward transcription for Japanese learners and typists. For instance, the kana し is rendered as "si" rather than approximating its sound with "shi," つ as "tu," and ち as "ti," ensuring orthographic regularity without deviations for foreign phonetic conventions. Long vowels are indicated with a circumflex accent, such as ô for prolonged o (as in "Tôkyô" for とうきょう), while geminate consonants are doubled (e.g., "kakka" for かっか). This approach prioritizes consistency for native speakers over intuitive readability in English.[17][29] In practice, Kunrei-shiki serves as the prescribed method for teaching romaji in Japanese elementary schools, where fourth-grade students learn it as part of the national curriculum to build foundational literacy in Latin script. It remains mandatory for certain legal and governmental documents, such as official notifications, though passports use modified Hepburn. Internationally, the system was codified in the ISO 3602 standard in 1989, endorsing its application in bibliographic, scientific, and technical contexts for consistent transliteration of Japanese terms.[17][30][31] Critics, particularly linguists and international educators, argue that Kunrei-shiki's rigid adherence to kana order results in spellings that are counterintuitive for non-Japanese speakers, such as "sito" for しと (shito in English approximation), potentially hindering accurate pronunciation and accessibility for global audiences. This phonetic disconnect has contributed to its limited adoption outside Japan, where Hepburn romanization prevails due to its alignment with English sound patterns. In August 2025, a government panel recommended revising the Kunrei-shiki rules for the first time since 1954 to include Hepburn-style elements, aiming to enhance international readability while maintaining core principles.[32][33][5]Nihon-shiki Romanization

Nihon-shiki romanization, also known as Nippon-shiki, was developed by Japanese physicist Aikitsu Tanakadate in 1885 as a method for Japanese speakers to transcribe their language using the Latin alphabet in a systematic manner.[2] Tanakadate aimed to create a uniform system that prioritized the phonemic structure of Japanese over approximations influenced by foreign languages, intending it as a tool for scientific and educational consistency within Japan.[34] This approach contrasted with earlier systems by emphasizing a strict one-to-one correspondence between kana syllables and Roman letters, facilitating precise representation without ambiguity.[35] The system's key rules focus on phonemic accuracy, rendering kana directly without adjustments for pronunciation shifts common in spoken Japanese. For instance, the syllable し is romanized as si rather than shi, ち as ti instead of chi, and つ as tu rather than tsu, maintaining the original gojūon order of the kana chart.[36] The ha-row is transcribed with h- initials (ha, hi, hu, he, ho), and distinctions for ambiguous pairs like じ (zi) and ぢ (di), or づ (du) and ず (zu), are preserved to reflect phonemic differences. Long vowels are indicated with a circumflex accent, such as ô for おう or 長音符, and the small tsu (っ) denotes gemination, doubling the following consonant, as in kitte for 切手.[37] These conventions ensure a rigid, syllabary-based mapping that avoids diacritics except where necessary for clarity in linguistic analysis.[38] Nihon-shiki has seen limited standalone usage, primarily confined to academic and linguistic contexts where phonemic precision is essential, such as in phonological studies or early scientific texts.[2] It served as the foundational model for Kunrei-shiki romanization, which adapted its principles for broader official adoption while simplifying some mappings to align with modern pronunciation.[38] Among its advantages is the elimination of biases from English phonology present in systems like Hepburn, enabling unbiased transcription that supports detailed linguistic analysis and consistency for native speakers familiar with kana.[35]Other Formal Systems

Japan Statistical Language (JSL)

The Japan Statistical Language (JSL) romanization system was developed by linguist Eleanor Harz Jorden for her 1987 textbook Japanese: The Spoken Language (Part 1), as part of post-World War II efforts in Japanese language pedagogy for non-native speakers.[39] Jorden, who contributed significantly to Japanese language teaching, formalized the system in this seminal work, where it served as a tool for precise phonetic transcription and prosodic analysis.[39] Designed primarily for linguistic research and structured teaching, JSL prioritizes explicit representation of Japanese phonology over simplified readability, making it suitable for academic study rather than everyday use. Key rules of JSL emphasize moraic structure and phonetic details central to Japanese. Hyphens mark mora boundaries to clarify syllable timing, as in o-ka-a-san for おかあさん (mother), highlighting the long vowel as two morae. Apostrophes denote glides or semivowels, distinguishing transitions like kya from separate syllables. Pitch accent, a critical prosodic feature, is notated with diacritics or symbols such as ꜜ to indicate pitch fall, exemplified by haꜜsi for 橋 (bridge, high-low pattern) versus hasi without accent. These conventions align with JSL's foundation in modified Kunrei-shiki but adapt it for analytical depth, similar to Hepburn in core consonant-vowel mappings like ch and sh.[39] Additional features address advanced phonology for non-native learners, including notations for devoicing (e.g., high vowels like /i/ or /u/ rendered silently in certain contexts) and gemination (doubled consonants shown explicitly to preserve timing). The system thus provides a comprehensive framework for prosody, enabling instructors to teach intonation and rhythm systematically. Primarily employed in academic linguistics and select teaching materials, such as Jorden's later works, JSL remains influential in research but has not achieved widespread adoption outside specialized contexts.Modified Hepburn and Related Variants

The Modified Hepburn romanization emerged as a refined iteration of the original Hepburn system, with significant revisions published in 1908 to better align with evolving Japanese pronunciation and orthographic conventions. These updates, influenced by figures like Kanō Jigorō and endorsed by the Rōmaji Hirome-kai (Society for the Propagation of Romanization), eliminated representations for obsolete syllables such as yi and ye, which had been included in earlier versions to account for historical kana but were no longer relevant in modern speech.[40][41] By the 1940s and 1950s, the society further standardized this form through ongoing adjustments, solidifying it as the preferred system for educational and reference materials.[42] This modified version gained prominence in lexicography, serving as the basis for romanization in major Japanese-English dictionaries like the fourth edition of Kenkyusha's New Japanese-English Dictionary (1958), where it renders the syllabic nasal as m before labials (e.g., Shimbashi for 新橋) and prioritizes intuitive English-like spellings.[3] The system's adoption extended to international standards, with bodies like the United States Board on Geographic Names and the UK Permanent Committee on Geographical Names using it since the 1930s for official mappings and publications.[22] Specific adaptations of Modified Hepburn appear in simplified forms for casual publishing and digital contexts, often omitting macrons for long vowels (e.g., Tokyo instead of Tōkyō) to enhance accessibility without specialized typography. Today, Modified Hepburn dominates global applications, appearing on Japanese road signs, passports, and in major media outlets for its user-friendly approximation of pronunciation.[2] It is the default in software tools, including Google Translate's romanization output, facilitating widespread use in education, tourism, and digital interfaces.[43]Non-Standard and Informal Romanizations

Wāpuro Rōmaji for Input

Wāpuro rōmaji, also known as kana spelling, emerged in the late 1970s as a practical method for inputting Japanese text into early word processors, with the term "wāpuro" deriving from the Japanese abbreviation for "word processor" (wādo purosessā).[23] This system was particularly suited to devices like the NEC PC-9800 series, launched in 1982, which popularized personal computing in Japan and required efficient Roman alphabet-based entry on QWERTY keyboards lacking dedicated kana layouts.[44] The core conventions of wāpuro rōmaji rely on predictive typing, where users enter sequences of Roman letters that an input method editor (IME) converts to hiragana, katakana, or kanji based on common phonetic mappings. For instance, typing "konnichiwa" produces こんにちは, while non-standard spellings like "syu" for the palatalized syllable しゅ or "tyou" for ちょう allow flexibility without diacritics or macrons, representing long vowels through doubled vowels (e.g., "ou" for おう).[45] These mappings often overlap with basic Hepburn romanization in simple cases but prioritize typing efficiency over phonetic precision.[23] This approach offers significant advantages for digital input, enabling faster composition without memorizing kana keyboard arrangements or special characters, which are often unavailable on standard keyboards. It remains the dominant method in Japanese IMEs, supported in systems for both desktops and mobiles, facilitating seamless conversion to native script.[46] Wāpuro rōmaji evolved with mobile technology starting in the 1990s, integrating into feature phones and later smartphones via touch-based QWERTY interfaces, where romaji input became the preferred mode for its accessibility on small screens. Post-2020 advancements have incorporated neural networks and AI for enhanced error correction and prediction; for example, recurrent neural network-based language models (RNN-LMs) in modern IMEs like Google's Gboard improve conversion accuracy for ambiguous inputs by analyzing context, reducing typing errors in real-time Japanese text entry.[47][48]Handling Ambiguous Kana (e.g., づ, ぅ)

In Japanese romanization, certain kana present challenges due to their rarity in modern standard usage, historical obsolescence, or dialectal pronunciations that deviate from Tokyo Japanese norms. These include the yotsugana ぢ and づ, which are pronounced identically to じ and ず in contemporary speech (/dʑi/ and /dzɯ/ or /zɯ/), the small vowels ぅ, ぇ, and ぉ used primarily in katakana for foreign loanwords or to indicate short or modified sounds, and the obsolete wi (ゐ/ヰ) and we (ゑ/ヱ), which have been revived occasionally in proper names despite their elimination from everyday writing in 1946.[49][50] These forms often arise in kanji compounds, personal names, or regional varieties, leading to ambiguities in transcription since major systems prioritize phonetic representation over strict orthographic distinction.[51] Major romanization systems handle these kana with varying degrees of distinction, reflecting their focus on either phonemic accuracy or input practicality. In the Hepburn and Kunrei-shiki systems, づ is uniformly rendered as "zu" to match its standard pronunciation, while small ぅ, ぇ, and ぉ are transcribed as "u," "e," and "o" without indicating their reduced size, as they do not form full syllables. Similarly, wi and we are romanized as "wi" and "we" when encountered in names, though they are noted as archaic. Nihon-shiki, being more systematic, differentiates づ as "du" to preserve the original orthography, aiding in reverse conversion from romaji to kana, but this creates input ambiguities in Hepburn-style keyboards where "du" produces づ while "zu" yields ず.[49][37] These conventions ensure readability for English speakers in Hepburn but can obscure subtle historical or orthographic differences.[51] Inconsistencies arise particularly in proper names, where personal or historical preferences may override standard rules. For instance, the place name 沼津 (Numazu) uses づ but is conventionally romanized as "Numazu" with "zu" in Hepburn, not "Numadu," to align with pronunciation; however, some transliterations, especially in older texts or for emphasis on etymology, opt for "du" to distinguish it from ず-based forms. Likewise, surnames like 続 (tsuzuku-related compounds) are typically "Tsuzuki" rather than "Duzuki," though rare variants appear in dialectal contexts or creative works. The small vowels follow suit: in loanwords like ファビオ (Fabio), ぉ is simply "o," but this can lead to homograph ambiguities with full-sized counterparts. Obsolete wi and we appear in revived names, such as company branding (e.g., "Wi" in stylized logos), romanized directly without alteration.[52][37][53] Dialectal varieties exacerbate these issues, as standard systems like Hepburn are designed for central Japanese and inadequately capture regional phonetics. In Okinawan, for example, sounds akin to /du/ or /bu/—distinct from mainland /dzɯ/ or /bɯ/—may be romanized as "du" or "bu" in adapted Hepburn schemes to reflect local pronunciation, such as in words borrowed or influenced by Ryukyuan languages; however, no dedicated ISO standard exists for these, leading to ad hoc conventions in linguistic documentation. Similarly, historical or Ainu-influenced pronunciations in northern dialects introduce ambiguous sounds (e.g., uvular or fricative variants) that standard romaji struggles to represent, highlighting a coverage gap for non-Tokyo varieties.[54] Place name examples like 辻 (tsuji, "crossroads") avoid づ entirely in standard readings but illustrate broader challenges when compounded with ambiguous elements, as in 辻続き (tsuzuki-related toponyms), romanized as "tsuzuki" without "dzu" to prevent unnatural affrication.[55][56]Specific Conventions

Long Vowels and Macrons

In Japanese phonology, long vowels are phonemically distinct from short vowels, functioning as bimoraic units that extend the duration of a single vowel sound, often arising from sequences of identical vowels across mora boundaries. Unlike diphthongs, which are absent in standard Japanese, these long vowels maintain clear syllable separation; for instance, the long ō in Tōkyō (東京) represents a prolonged /o:/ sound derived from the kana sequence おう, treated as two moras rather than a gliding vowel combination.[57][58] Different romanization systems employ varied notations for these long vowels, reflecting their design priorities. The Hepburn system and Japan Statistical Language (JSL) use macrons (¯) over the vowel to denote length, as in tōkyō for 東京 or ōsaka for 大阪, providing a compact and visually distinct marker that aligns with international linguistic conventions. In contrast, Kunrei-shiki romanization indicates long vowels through doubled letters, such as tookyoo for 東京, emphasizing a phonetic transcription closer to kana structure without diacritics. Nihon-shiki, a precursor to Kunrei-shiki, traditionally employs a circumflex accent (^) for the same purpose, yielding forms like tôkyô in older texts, though this is less common in modern applications.[21][22] The representation of long vowels has sparked ongoing debates, particularly regarding the omission of macrons in informal and English-language contexts, where Tokyo supplants Tōkyō, potentially obscuring phonological distinctions and leading to mispronunciations by non-speakers. This practice persists in global media and branding for simplicity, despite its inaccuracy. During the 2010s, linguistic advocates and type designers pushed for greater adoption of macrons in official Japanese signage, such as at train stations and airports, to enhance clarity for tourists; however, many public displays continued to forgo them due to typographic constraints. In August 2025, a government panel recommended revising the standards to favor Hepburn-style elements, including macrons for long vowels while permitting alternatives like doubled vowels when technical limitations arise, with Cabinet approval expected within 2025 and implementation in 2026, marking a proposed shift toward precision in international communication.[59][5][60] Practical implementation of macrons benefits from Unicode standardization, where the combining macron (U+0304) allows seamless integration into digital text, enabling accurate rendering of forms like tō without requiring precomposed characters. This support has facilitated broader use in software, publications, and online resources since the early 2000s, though legacy systems occasionally default to omission.[59][61]Spacing and Word Boundaries

Japanese writing systems, such as kana and kanji, do not employ spaces to mark word boundaries, a feature stemming from the language's agglutinative structure where particles and affixes directly attach to stems. For instance, the phrase meaning "my house" (watashi no ie) appears as わたしの家 in hiragana-kanji mix or わたしのいえ in pure hiragana, with no visual separation between elements. This absence of spacing complicates romanization, as Latin script conventions demand clear delineation for readability in non-Japanese contexts, often requiring decisions on where to insert spaces, hyphens, or none at all to reflect morphological units without altering meaning.[21] Romanization conventions for spacing vary across systems and applications, though they generally prioritize separating major lexical items while handling particles and compounds contextually. In the Modified Hepburn system, commonly used in Western publications, spaces are inserted between nouns and following particles for clarity, as seen in examples like Tōkyō ga (東京が, "Tokyo [topic marker]"), though some variants attach particles directly (e.g., Tōkyō-ga). The Library of Congress guidelines, aligned with Hepburn principles, advocate separating particles from preceding words, such as kōfuku e no michi (幸福への道, "road to happiness"), while treating tight compounds as single units like wareware (我々, "we"). Kunrei-shiki, the official Japanese government system, employs minimal spacing, often rendering phrases with fewer breaks to mimic the continuous flow of kana, such as watasi no ie without intervening spaces between possessive elements. In contrast, the Japan Statistical Language (JSL) system, developed for linguistic analysis, uses hyphens to indicate grammatical connections, exemplified by watashi-no ie (私の家, "my house") to denote possession explicitly.[21][23][51] Style guides provide standardized approaches to these challenges. The Chicago Manual of Style (15th edition, 2003) endorses the Modified Hepburn system and recommends spacing nouns from particles while keeping compounds intact unless context demands division, promoting consistency in academic and editorial work. For official documents like passports, Japanese guidelines since the 1954 Cabinet Order (with updates aligning to ICAO standards by the 1980s) mandate no spaces or hyphens between family and given names, treating the full name as a continuous string (e.g., TanakaHiroshi), to ensure machine-readable uniformity despite deviations from strict Kunrei-shiki spelling.[62][63] Variations persist between academic, popular, and official uses, with academic writing favoring detailed spacing per guides like the Library of Congress for precision, while popular media often adopts looser conventions for natural flow. An emerging gap involves digital standards, where algorithms in search engines like Google accommodate both spaced and unspaced romanizations for better query matching; for example, the National Diet Library's 2008 word division guidelines inform cataloging and search optimization by defining morpheme-based breaks to enhance retrieval in digital libraries.[21][64]Punctuation and Diacritics

In Hepburn romanization, apostrophes are employed to denote glides formed by small kana or to separate the moraic nasal "n" from subsequent vowels and semivowels, preventing phonetic ambiguity; for instance, the combination きゃ (ki + small ya) is rendered as k'ya, and あんな (a n na) as an'na.[22] This convention aligns with English orthographic practices to clarify pronunciation for non-native readers.[37] The Japan Statistical Language (JSL) system utilizes hyphens to delineate mora boundaries, particularly in pedagogical contexts, aiding the visualization of Japanese's rhythmic structure; an example is o-ha-yō for おはよう (good morning), where hyphens separate each mora.[51] This approach emphasizes phonemic accuracy over seamless word flow. Punctuation in Japanese romanization generally adapts Western conventions, with full stops (periods) and commas used as in English, though Japanese typographic influence often results in no space preceding the comma or period for tighter integration with text.[21] Quotation marks for titles and dialogue typically follow double straight quotes (" "), mirroring English standards in Hepburn and related systems, while avoiding Japanese-style corner brackets in Latin script renderings.[23] Diacritics are minimal in most systems: Kunrei-shiki employs none beyond occasional circumflex accents (ˆ) for long vowels in certain implementations, such as Tôkyô for 東京, prioritizing simplicity.[17] In contrast, JSL incorporates diacritics to mark pitch accent, using a low-tone indicator like ꜜ placed beneath vowels to denote pitch drops, as in haꜜshi for 橋 (bridge) versus hashí for 箸 (chopsticks).[33] Some lesser-used variants, particularly in linguistic or international contexts, apply carons (ˇ) to represent palatalized sibilants, rendering chi as či and shi as ši for phonetic precision.[65] Hepburn adheres closely to English norms, avoiding additional diacritics except for optional macrons on long vowels. Notably, adaptations of romanization for Japanese Braille remain underexplored in post-2010 digital tools, with limited standardization for integrating diacritics and punctuation in accessible formats.[66]Comparisons and Applications

Key Differences Across Systems

The major Romanization systems for Japanese—primarily Hepburn, Kunrei-shiki, and Nihon-shiki—differ fundamentally in their approach to representing sounds: Hepburn is phonetic, aiming to approximate English-like pronunciation for non-native speakers, while Kunrei-shiki and Nihon-shiki are phonemic, systematically mapping kana to Latin letters without regard for English conventions.[2] For instance, the kana ち is rendered as "chi" in Hepburn to evoke its affricate sound [tɕi], whereas Kunrei-shiki and Nihon-shiki use "ti," reflecting the underlying phoneme and prioritizing kana consistency.[2] This phonetic emphasis in Hepburn makes it more intuitive for English speakers, who might mispronounce "ti" as [ti] rather than [tɕi], whereas the phonemic systems avoid digraphs like "ch" or "sh" to maintain a one-to-one correspondence with hiragana.[67] Vowel representation also varies significantly, with Hepburn employing macrons (e.g., ō, ū) to denote long vowels for clarity in international contexts, while Kunrei-shiki typically uses circumflexes (e.g., ô, û) to indicate length without macrons.[68] This difference affects readability: macrons in Hepburn distinguish long ō in words like Tōkyō from short o in Tokyo, preventing confusion, whereas circumflexes in Kunrei-shiki, such as Tôkyô, provide a distinct marker but may require specific typographic support.[2] Consonant clusters, particularly sokuon (gemination marked by small っ), are handled uniformly as doubles (e.g., "pp" in Sapporo) across systems, but Hepburn introduces digraphs like "ts" for つ to mimic English clusters, contrasting with the more rigid "tu" in phonemic systems.[2] In terms of adoption, Hepburn serves practical, export-oriented uses and accounts for approximately 75% of preferences in global and domestic readability tests, while Kunrei-shiki remains the official domestic standard taught in schools.[67] Hepburn's prevalence in international media, signage, and passports—used on nearly all public road signs—stems from its accessibility, whereas Kunrei-shiki's role in education reinforces systematic learning but limits its external application.[69] These divergences lead to practical impacts, such as confusion in place names like Atsugi (Hepburn) versus Atugi (Kunrei-shiki), where inconsistent spellings hinder recognition for travelers and contribute to ongoing standardization debates.[69] Surveys from the 2020s indicate that around 60-75% of Japanese respondents favor Hepburn for its phonetic clarity in everyday and international contexts.[67][69]Example Words in Multiple Romanizations

To illustrate the differences between major Romanization systems, the following table provides side-by-side transcriptions of common Japanese words, covering aspects such as long vowels, sibilants (e.g., shi/si), affricates (e.g., chi/ti, tsu/tu), and compounds. Examples include standard vocabulary, particles, names, and a modern internet slang term (e.g., "bucchake" for candidly speaking, popularized post-2015 in online contexts). Transcriptions follow standard conventions for each system: Hepburn uses macrons for long vowels and English-like approximations; Kunrei-shiki and Nihon-shiki use circumflexes or doubled vowels with phonetic consistency to kana; JSL employs doubled vowels and occasional hyphens to denote mora boundaries or emphasis.[51][37][17]| Japanese (Kana/Kanji) | English Meaning | Hepburn | Kunrei-shiki | Nihon-shiki | JSL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| とうきょう (東京) | Tokyo | Tōkyō | Tôkyô | Toôkyô | Tookyoo |

| ありがとう | thank you | Arigatō | Arigatô | Arigatoo | Arigatoo |

| ちいさい | small | Chiisai | Tiisai | Tiisai | Tiisai |

| つき (月) | moon | Tsuki | Tuki | Tuki | Tuki |

| すし (寿司) | sushi | Sushi | Susi | Susi | Susi |

| しあわせ | happiness | Shiawase | Siawase | Siawase | Siawase |

| コーヒー | coffee | Kōhī | Koohii | Koohii | Koohii |

| 富士 (富士山) | Mount Fuji | Fuji | Huzi | Huuzi | Huuzi |

| ちぢむ (縮む) | to shrink | Chijimu | Tizimu | Tizimu | Tizimu |

| ふうせん (風船) | balloon | Fūsen | Huusen | Huusen | Huusen |

| は (particle) | topic marker (wa) | Wa | Wa | Wa | Wa |

| すずき (鈴木) | Suzuki (name) | Suzuki | Suzuki | Suzuki | Suzuki |

| きょうと (京都) | Kyoto | Kyōto | Kyôto | Kyooto | Kyootoo |

| ぶっちゃけ | candidly (slang) | Bucchake | Buttyake | Buttyake | Buttyake |

| わらう (笑う) | to laugh (lol equivalent in netslang) | Warau | Warau | Warau | Warau |

Usage in Modern Contexts (e.g., Passports, Digital Tools)

In Japanese passports, the Hepburn romanization system has been mandated for personal names since 1986, with the transliteration fixed upon issuance and traditionally omitting macrons to indicate long vowels for simplicity and readability in international contexts.[2] This approach ensures consistency with global passport standards, though it has led to occasional mismatches with native pronunciation, such as rendering "Tōkyō" as "Tokyo." Recent developments in the 2020s include experimental trials to incorporate macrons on select documents, reflecting growing recognition of their utility in precise representation.[71] In digital tools and online applications, Hepburn romanization predominates for output and display, while wāpuro rōmaji serves as the primary method for user input via standard QWERTY keyboards. Wāpuro rōmaji, designed for efficient kana entry on early word processors, allows users to type approximations like "toukyou" which are then converted to "Tōkyō" in Hepburn style by input method editors (IMEs) in systems like Microsoft IME or Google Japanese Input. For web domains, Japan's .jp registration guidelines, overseen by the Japan Registry Services (JPRS), recommend Hepburn conventions to align with international usability, prohibiting certain Kunrei-shiki variants and favoring spellings like "shi" over "si" for broader accessibility.[72] Beyond official documents, Hepburn is widely adopted in transportation and media. Japan Railways (JR) Group employs Hepburn for station names and signage on rail passes and networks, facilitating navigation for international travelers, as seen in renderings like "Shinjuku" rather than "Sinzyuku."[73] In entertainment, subtitles for anime and video games often mix systems but favor Hepburn, prioritizing English-like phonetics for global audiences.[51] In August 2025, a government panel under the Agency for Cultural Affairs recommended revising the official Kunrei-shiki rules for the first time since 1954, incorporating Hepburn-style elements such as "chi" for ち and macrons for long vowels to improve international readability. As of November 2025, the revision is expected to be approved and gradually implemented, potentially affecting educational materials, official signage, and digital standards while maintaining compatibility with existing Hepburn usage in passports and international contexts.[5]References

- https://en.[wikipedia](/page/Wikipedia).org/wiki/JSL_romanization