Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

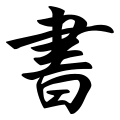

Polivanov system

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2024) |

|

| Japanese writing |

|---|

| Components |

| Uses |

| Transliteration |

Polivanov system is a system of transliterating the Japanese language into Russian Cyrillic script, either to represent Japanese proper names or terms in Russian or as an aid to Japanese language learning in those languages.[vague] The system was developed by Yevgeny Polivanov in 1917.

In terms of spelling the system is a middle ground between Kunrei-shiki and Hepburn romanisations, matching the former everywhere except for morae hu and tu, which are spelled as in Hepburn (fu and tsu), moras starting with z (which are spelled with dz, as in archaic Hepburn, but following the consistency of Kunrei-shiki with Jun being spelled as Dzyun) and syllabic n, which is changed to m before b, p and m as in traditional Hepburn.

The following cyrillization system for Japanese is known as the Yevgeny Polivanov system. Note that it has its own spelling conventions and does not necessarily constitute a direct phonetic transcription of the pronunciation into the standard Russian usage of the Cyrillic alphabet.

Main table

[edit]Hiragana and Katakana to Polivanov cyrillization correspondence table, for single/modified kana.[citation needed]

| Kana | Cyrillic | Hepburn | |

|---|---|---|---|

| あ | ア | а | a |

| か | カ | ка | ka |

| さ | サ | са | sa |

| た | タ | та | ta |

| な | ナ | на | na |

| は | ハ | ха | ha |

| ま | マ | ма | ma |

| や | ヤ | я | ya |

| ら | ラ | ра | ra |

| わ | ワ | ва | wa |

| ん | ン | -н | -n |

| が | ガ | га | ga |

| ざ | ザ | дза | za |

| だ | ダ | да | da |

| ば | バ | ба | ba |

| ぱ | パ | па | pa |

| Kana | Cyrillic | Hepburn | |

|---|---|---|---|

| い | イ | и/й | i |

| き | キ | ки | ki |

| し | シ | си | shi |

| ち | チ | ти | chi |

| に | ニ | ни | ni |

| ひ | ヒ | хи | hi |

| み | ミ | ми | mi |

| り | リ | ри | ri |

| ゐ | ヰ | ви | wi |

| ぎ | ギ | ги | gi |

| じ | ジ | дзи | ji |

| ぢ | ヂ | дзи | ji |

| び | ビ | би | bi |

| ぴ | ピ | пи | pi |

| Kana | Cyrillic | Hepburn | |

|---|---|---|---|

| う | ウ | у | u |

| く | ク | ку | ku |

| す | ス | су | su |

| つ | ツ | цу | tsu |

| ぬ | ヌ | ну | nu |

| ふ | フ | фу | fu |

| む | ム | му | mu |

| ゆ | ユ | ю | yu |

| る | ル | ру | ru |

| ぐ | グ | гу | gu |

| ず | ズ | дзу | zu |

| づ | ヅ | дзу | zu |

| ぶ | ブ | бу | bu |

| ぷ | プ | пу | pu |

| Kana | Cyrillic | Hepburn | |

|---|---|---|---|

| え | エ | э | e |

| け | ケ | кэ | ke |

| せ | セ | сэ | se |

| て | テ | тэ | te |

| ね | ネ | нэ | ne |

| へ | ヘ | хэ | he |

| め | メ | мэ | me |

| れ | レ | рэ | re |

| ゑ | ヱ | вэ | we |

| げ | ゲ | гэ | ge |

| ぜ | ゼ | дзэ | ze |

| で | デ | дэ | de |

| べ | ベ | бэ | be |

| ぺ | ペ | пэ | pe |

| Kana | Cyrillic | Hepburn | |

|---|---|---|---|

| お | オ | о | o |

| こ | コ | ко | ko |

| そ | ソ | со | so |

| と | ト | то | to |

| の | ノ | но | no |

| ほ | ホ | хо | ho |

| も | モ | мо | mo |

| よ | ヨ | ё | yo |

| ろ | ロ | ро | ro |

| を | ヲ | во | wo |

| ご | ゴ | го | go |

| ぞ | ゾ | дзо | zo |

| ど | ド | до | do |

| ぼ | ボ | бо | bo |

| ぽ | ポ | по | po |

| Kana | Cyrillic | Hepburn | |

|---|---|---|---|

| きゃ | キャ | кя | kya |

| しゃ | シャ | ся | sha |

| ちゃ | チャ | тя | cha |

| にゃ | ニャ | ня | nya |

| ひゃ | ヒャ | хя | hya |

| みゃ | ミャ | мя | mya |

| りゃ | リャ | ря | rya |

| ぎゃ | ギャ | гя | gya |

| じゃ | ジャ | дзя | ja |

| ぢゃ | ヂャ | дзя | ja |

| びゃ | ビャ | бя | bya |

| ぴゃ | ピャ | пя | pya |

| Kana | Cyrillic | Hepburn | |

|---|---|---|---|

| きゅ | キュ | кю | kyu |

| しゅ | シュ | сю | shu |

| ちゅ | チュ | тю | chu |

| にゅ | ニュ | ню | nyu |

| ひゅ | ヒュ | хю | hyu |

| みゅ | ミュ | мю | myu |

| りゅ | リュ | рю | ryu |

| ぎゅ | ギュ | гю | gyu |

| じゅ | ジュ | дзю | ju |

| ぢゅ | ヂュ | дзю | ju |

| びゅ | ビュ | бю | byu |

| ぴゅ | ピュ | пю | pyu |

| Kana | Cyrillic | Hepburn | |

|---|---|---|---|

| きょ | キョ | кё | kyo |

| しょ | ショ | сё | sho |

| ちょ | チョ | тё | cho |

| にょ | ニョ | нё | nyo |

| ひょ | ヒョ | хё | hyo |

| みょ | ミョ | мё | myo |

| りょ | リョ | рё | ryo |

| ぎょ | ギョ | гё | gyo |

| じょ | ジョ | дзё | jo |

| ぢょ | ヂョ | дзё | jo |

| びょ | ビョ | бё | byo |

| ぴょ | ピョ | пё | pyo |

Syllabic n (ん/ン) is spelled м (m) before b, p, m, and spelled нъ before vowels.

Grammar particles は and へ are written ва and э. Syllable を is written either во or о depending on pronunciation (albeit о is more preferred).

Diphthongs

[edit]It is permitted to use й instead of и in diphthongs (e.g. shinjitai → синдзитай, seinen → сэйнэн). However, и is always used on a morpheme clash: Kawai (kawa + i) → Каваи.

Yevgeny Polivanov recommended (but not prescribed as mandatory) to use й for Sino-Japanese (on'yomi) words, and и for native Japanese (kun'yomi) words. Another Polinanov's recommendation is to spell the diphthong ei as a long vowel э:, but this recommendation is almost never followed in practice. Instead, long vowel ē in the name ending -bē is often transliterated as -эй, e.g. Gonbē → Гомбэй.

Geminate consonants

[edit]Consonants are geminated exactly as they are in romaji: e.g. -kk- > -кк-.

Long vowels

[edit]Long vowels may be marked by macron as in Hepburn, but since letter ё has a diacritical mark already it is permitted and much more common to mark long vowels by using a colon (e.g. сё:гун). The sequence ei may be written э:, эй or эи. In regular texts long vowels are usually unmarked.

Vowel omission

[edit]Normally, vowels in the Polivanov system are always spelled, even if they are not pronounced. However, the voiceless u in the name ending -suke may be omitted:

Ryūnosuke → Рюноскэ.

Some translators tend to omit voiceless u in all cases when su (and, less often, tsu) is followed by a k-syllable, e.g. Akatsuki → Акацки, Daisuki → Дайски. However, this omission is considered non-standard.

Another non-standard (if not controversial) practice is omitting the voiceless u at the end of words, mostly in desu → дэс and masu → мас. This spelling can be found in some learning materials, but most professional translators oppose it, because native speakers may pronounce su at the end of the word with a distinctive u sound (especially in "feminine" speech).

Common mistakes and deviations

[edit]In English texts, Japanese names are written with the Hepburn system. Attempts may be made to transcribe these as if they were English, rather than following a dedicated Japanese Cyrillization scheme.

A common example of this is attempting to transcribe shi (Polivanov: си) as ши and ji (Polivanov: дзи) as джи. This is inadvisable for use in Russian, because ши is actually pronounced like шы in Russian, and джи like джы, thus making the vowel (/ɨ/) closer to Japanese /u/ than to Japanese /i/. Whereas, щи would have a correct vowel sound, but be pronounced more like Japanese sshi.

Equally often, people transcribe cha, chi, chu, cho as ча, чи, чу, чо. This is phonetically correct, but does not conform with the Polivanov scheme (тя, ти, тю, тё), which more closely resembles the Kunrei-shiki romanisations (tya, ti, tyu, tyo) for these particular characters.

Sometimes е, rather than э, is used for e, despite е being pronounced ye in Russian (though not in other languages). This is typically not done in the initial position, despite older romanisations such as "Yedo" doing so. In any case, it does not conform with the Polivanov scheme, although it is seen as more acceptable for words that are in general use (e.g. kamikaze > камикадзе instead of камикадзэ). Replacing ё (yo) with е (ye) is incorrect, however, as it will change the Japanese word too much.

The sound yo (Polivanov: ё), when in the initial position or after a vowel, is often written as йо (yo), which has the same pronunciation: Ёкосука -> Йокосука (Yokosuka), Тоёта -> Тойота (Toyota). Although, the spelling "йо" is not common in Russian words, these are more generally accepted for Japanese names than the transliterations using "ё". "Ё" is not often used in Japanese Cyrillization due to its facultative use in the Russian language (and possible substitution with the letter "Е" which would affect the pronunciation), but for professional translators, the use of ё is mandatory.[citation needed] Some personal names beginning with "Yo" (or used after a vowel) are written using "Ё" (e.g. Йоко for Yoko Ono, but Ёко for Yoko Kanno and all other Yokos).

Exceptions

[edit]Some proper names, for historical reasons, do not follow the above rules. For example, the geographical names of Japan in Russian are transmitted according to special instructions for the transfer of geographical names (other language names, for example from the Ainu language, do not fall under the Polivanov system).[1] Other Japanese names and concepts were adapted into Russian from other languages (for example, under the influence of Hepburn or other transliteration systems). Those include but are not limited to:[citation needed]

| English (Rōmaji) | Russian spelling | Cyrillization | Japanese |

|---|---|---|---|

| Japan (Nihon, Nippon) | Япония | Нихон, Ниппон | 日本 (にほん, にっぽん) |

| Tokyo (Tōkyō) | Токиo | То:кё: | 東京 (とうきょう) |

| Kyoto (Kyōto) | Киото | Кё:то | 京都 (きょうと) |

| Yokohama | Иокогама (also Йокохама) | Ёкохама | 横浜 (よこはま) |

| Yokosuka | Йокосука | Ёкосука | 横須賀 (よこすか) |

| Toyota | Тойота (Тоёта in older publications) | Тоёта | トヨタ (originally: 豊田) |

| jujitsu (jūjutsu) | джиу-джитсу | дзю:дзюцу | 柔術 (じゅうじゅつ) |

| yen (en) | иена | эн | 円 (えん) |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]External links

[edit]Polivanov system

View on GrokipediaHistory and Background

Origins and Development

The Polivanov system emerged in 1917 as a transliteration method for rendering Japanese into Russian Cyrillic script, created by linguist Yevgeny Dmitrievich Polivanov amid his extensive fieldwork on Japanese dialects and phonetics. Polivanov, who had traveled to Japan multiple times between 1914 and 1916 under the auspices of the Russo-Japanese Society to conduct psychophonetic studies, refined his approach to Japanese transcription during this period of direct immersion in the language. His work bridged his experiences in Tokyo and other regions with the needs of Russian orientalists, resulting in a system designed for phonetic accuracy within Cyrillic constraints.[4] The system's development was motivated by the post-Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905) thaw in bilateral relations, which spurred increased Russian interest in Japanese culture, language, and texts for diplomatic, academic, and economic purposes. Following the Portsmouth Treaty and subsequent agreements like the 1907 Russo-Japanese Convention, cultural exchanges intensified, including through organizations such as the Imperial Society of Oriental Studies, where Polivanov served. This context necessitated a reliable tool for Russian speakers to access Japanese proper names, literature, and scholarly materials without relying on Latin-based systems ill-suited to Cyrillic phonology.[5] Polivanov first detailed the system in his seminal 1917 article "O russkoj transkripcii japonskix slov" (On the Russian Transcription of Japanese Words), published in the inaugural issue of the Trudy japonskogo otdela Imperatorskogo obščestva vostokovedenija. In this work, he proposed mappings that prioritized Russian phonetic equivalents while partially drawing on established romanization conventions like Hepburn's for handling Japanese syllable structure. The article laid the foundational rules, emphasizing moraic representation and avoidance of typographical complexities, and it remains a cornerstone reference for the system's origins.[6]Creator and Historical Context

Yevgeny Dmitrievich Polivanov (1891–1938) was a prominent Russian and Soviet linguist, orientalist, and polyglot renowned for his expertise in Asian languages.[1] Born on February 28, 1891, in Smolensk, he graduated from the Japanese Division of the Oriental Practical Academy in St. Petersburg in 1911 and later from St. Petersburg University in 1912.[1] In the 1910s, Polivanov conducted extensive fieldwork in Japan, visiting Tokyo and other regions multiple times between 1914 and 1916 to study Japanese dialectology, during which he immersed himself in the language's phonetic and phonological features.[1] His early exposure to Japanese, combined with mastery of over 40 languages including Chinese, Korean, Uzbek, and Dungan, positioned him as a key figure in Soviet oriental studies.[7] The Polivanov system emerged in the early Soviet era, a period marked by heightened state interest in Asian languages to support diplomatic relations, intelligence operations, and geopolitical strategy amid tensions with Japan and expansion into Central Asia.[7] Polivanov, who joined the Communist Party in 1919 and worked with the Comintern, contributed to this effort through his teaching at institutions like the Communist University of the Toilers of the East and his development of phonetically accurate transliteration methods.[1] Beyond Japanese, his works on Caucasian and Turkic linguistics, including grammars of Turkmen and Uzbek, emphasized precise phonetic representation to aid in language standardization and cross-cultural communication in the multi-ethnic Soviet Union.[1] In 1917, he first outlined his Cyrillic-based transliteration for Japanese in a publication on Russian transcription of Japanese words, prioritizing fidelity to spoken sounds over orthographic conventions.[8] Polivanov's influence extended to shaping Soviet Japanology programs in the 1920s and 1930s, where he collaborated on major projects like the Japanese-Russian dictionary and promoted rigorous linguistic training for diplomats and scholars.[7] However, his career was abruptly ended by the Stalinist purges; arrested in March 1937 in Frunze (now Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan) on charges of treason, he was executed on January 25, 1938, in Moscow at the Kommunarka shooting ground, which curtailed the immediate dissemination of his transliteration system and other innovations. He was posthumously rehabilitated in 1963, allowing his phonetic-focused approaches to gain wider recognition in later Soviet linguistics.[1]Overview and Usage

Core Principles

The Polivanov system is fundamentally grounded in a phonetic transcription that approximates the moraic structure of Japanese using the Cyrillic alphabet, emphasizing the treatment of syllables—or more precisely, moras—as indivisible units rather than dissecting them into individual alphabetic components. This approach aligns the rhythmic equality of Japanese moras with the syllabic nature of Russian phonology, ensuring that transcriptions capture the language's prosodic features, such as the consistent timing of open syllables (typically consonant-vowel or vowel-only). By basing the system on the Tokyo dialect's pronunciation, it prioritizes auditory fidelity for Russian speakers while adapting Japanese sounds to the Cyrillic inventory without introducing foreign elements.[9] Central to the system's principles is the preservation of Japanese vowel qualities, mapping the five basic vowels (a, i, u, e, o) directly to their Russian Cyrillic counterparts (а, и, у, э, о) to avoid distortion and maintain the language's vowel purity and sequential harmony in compounds. Approximations for sounds before i and y use mappings like ти for chi and я/ю/ё for ya/yu/yo, with the soft sign (ь) used in specific cases like certain compounds to indicate softness, providing a natural approximation within Russian orthography. For simplicity and practicality in the Russian script, the system eschews unnecessary diacritics, limiting modifications to occasional markers like a colon (:) for long vowels, thereby facilitating readability without compromising core phonetic intent.[9][10] In relation to other romanization systems, the Polivanov method strikes a balance between the phonetically oriented Hepburn system—which closely mirrors English pronunciation—and the more systematic, mora-preserving Kunrei-shiki, but tailored specifically for Cyrillic to enhance accessibility and intuitive pronunciation for Russian audiences. This positioning underscores its role as a practical bridge, favoring cultural and linguistic adaptation over strict international phonetic notation. For instance, it briefly references basic mappings like か to ка to illustrate this fidelity, though detailed rules follow elsewhere.[9]Modern Applications and Comparisons

The Polivanov system remains the standard for transliterating Japanese proper names and terms into Russian Cyrillic in academic texts, dictionaries, and media, a practice that originated in Soviet-era Japanology and has persisted in post-1991 Russia due to its official status in scholarly and institutional contexts.[11][12] For instance, it is employed in Russian university curricula for Japanese studies and in publications by the Institute of Slavic Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences, ensuring consistency in representing Japanese linguistic elements for Russian-speaking audiences.[13] This widespread adoption underscores its role in facilitating access to Japanese cultural and scientific content within Russian intellectual traditions. In comparisons with other transliteration methods, the Polivanov system aligns more closely with the phonetic principles of the Hepburn romanization, prioritizing natural pronunciation over strict syllable mapping, whereas it diverges from the systematic Kunrei-shiki approach favored by the Japanese government. For example, Polivanov renders "shi" (し) as "си" and Hepburn as "shi", both approximating the palatal sibilant, while Kunrei-shiki uses "si"; "fu" (ふ) as "фу" in Polivanov, matching Hepburn's "fu", versus Kunrei-shiki's "hu".[13] Similarly, "tsu" (つ) becomes "цу" in Polivanov, akin to Hepburn's "tsu", contrasting with Kunrei-shiki's "tu," which can lead to less intuitive readings for non-specialists; this phonetic emphasis makes Polivanov particularly suitable for Russian phonology, where sounds like "си" and "фу" have direct equivalents.[14] A representative case is "Tokyo," uniformly transliterated as "Токио" across Polivanov and Hepburn but adapted systematically in Kunrei-shiki as "Tōkyō," highlighting Polivanov's balance between accessibility and accuracy in Cyrillic contexts.[13] Modern adaptations of the Polivanov system include digital tools that automate Cyrillic conversions from Japanese input, supporting its integration into contemporary workflows for translation and education as of 2025. Online platforms such as Russki Mat implement Polivanov for Cyrillic output alongside Hepburn, enabling users to generate transliterations for sentences and names efficiently.[15] Similarly, converters on sites like KanjiDB.ru apply Polivanov rules to process romaji or kana into Cyrillic, aiding linguists and enthusiasts in post-Soviet digital environments where manual transcription remains labor-intensive.[16] These tools reflect the system's ongoing relevance, with examples like "Shinjuku" rendered as "Синдзюку" in official Russian transliterations and persistent digital references, though broader AI language models as of November 2025 have yet to standardize its implementation beyond niche applications.[12]Core Transliteration Rules

Basic Consonant and Vowel Mappings

The Polivanov system provides a foundational set of mappings for the basic consonants and vowels in Japanese hiragana and katakana to Cyrillic, enabling a phonetic transcription that aligns Japanese syllabic structure with Russian orthography while preserving key distinctions in pronunciation. These mappings, which cover the standard 46 morae of the gojūon syllabary (excluding obsolete characters like ゐ and ゑ in modern usage), treat each kana as a syllable comprising a consonant (or semivowel) followed by a vowel, with voiced variants indicated by dakuten marks. This approach ensures readability for Russian speakers by adapting unfamiliar Japanese sounds to familiar Cyrillic equivalents, such as using ц for the affricate ts and adjusting the h-series for phonetic accuracy.[17] The core mappings are organized by the traditional kana rows (a, i, u, e, o), as shown in the table below. Hiragana and katakana share identical transliterations in this system, and palatalized forms (e.g., kya) follow the base mappings with y-vowel combinations like я, ю, ё. Voiced consonants (g, z, d, b) and glottalized/p-series (p) are derived by adding dakuten or handakuten to the unvoiced bases.| Row | a | i | u | e | o |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Vowels) | а (あ/ア) | и (い/イ) | у (う/ウ) | э (え/エ) | о (お/オ) |

| k/g | ка (か/カ) га (が/ガ) | ки (き/キ) ги (ぎ/ギ) | ку (く/ク) гу (ぐ/グ) | кэ (け/ケ) гэ (げ/ゲ) | ко (こ/コ) го (ご/ゴ) |

| s/z | са (さ/サ) дза (ざ/ザ) | си (し/シ) дзи (じ/ジ) | су (す/ス) дзу (ず/ズ) | сэ (се/セ) дзэ (ぜ/ゼ) | со (そ/ソ) дзо (ぞ/ゾ) |

| t/d | та (た/タ) да (だ/ダ) | ти (ち/チ) дзи (ぢ/ヂ) | цу (つ/ツ) дзу (づ/ヅ) | тэ (て/テ) дэ (で/デ) | то (と/ト) до (ど/ド) |

| n | на (な/ナ) | ни (に/ニ) | ну (ぬ/ヌ) | нэ (ね/ネ) | но (の/ノ) |

| h/b/p | ха (は/ハ) ба (ば/バ) па (ぱ/パ) | хи (ひ/ヒ) би (び/ビ) пи (ぴ/ピ) | фу (ふ/フ) бу (ぶ/ブ) пу (ぷ/プ) | хэ (へ/ヘ) бэ (べ/ベ) пэ (ぺ/ペ) | хо (ほ/ホ) бо (ぼ/ボ) по (ぽ/ポ) |

| m | ма (ま/マ) | ми (み/ミ) | му (む/ム) | мэ (め/メ) | мо (も/モ) |

| y | я (や/ヤ) | - | ю (ゆ/ユ) | - | ё (よ/ヨ) |

| r | ра (ら/ラ) | ри (り/リ) | ру (る/ル) | рэ (れ/レ) | ро (ろ/ロ) |

| w | ва (わ/ワ) | - | - | - | - |