Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Stem cell

View on Wikipedia| Stem cell | |

|---|---|

Transmission electron micrograph of a mesenchymal stem cell displaying typical ultrastructural characteristics | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | cellula praecursoria |

| MeSH | D013234 |

| TH | H1.00.01.0.00028, H2.00.01.0.00001 |

| FMA | 63368 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

In multicellular organisms, stem cells are undifferentiated or partially differentiated cells that can change into various types of cells and proliferate indefinitely to produce more of the same stem cell. They are the earliest type of cell in a cell lineage.[1] They are found in both embryonic and adult organisms, but they have slightly different properties in each. They are usually distinguished from progenitor cells, which cannot divide indefinitely, and precursor or blast cells, which are usually committed to differentiating into one cell type.

In mammals, roughly 50 to 150 cells make up the inner cell mass during the blastocyst stage of embryonic development, around days 5–14. These have stem-cell capability. In vivo, they eventually differentiate into all of the body's cell types (making them pluripotent). This process starts with the differentiation into the three germ layers – the ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm – at the gastrulation stage. However, when they are isolated and cultured in vitro, they can be kept in the stem-cell stage and are known as embryonic stem cells (ESCs).

Adult stem cells are found in a few select locations in the body, known as niches, such as those in the bone marrow or gonads. They exist to replenish rapidly lost cell types and are multipotent or unipotent, meaning they only differentiate into a few cell types or one type of cell. In mammals, they include, among others, hematopoietic stem cells, which replenish blood and immune cells, basal cells, which maintain the skin epithelium, and mesenchymal stem cells, which maintain bone, cartilage, muscle and fat cells. Adult stem cells are a small minority of cells; they are vastly outnumbered by the progenitor cells and terminally differentiated cells that they differentiate into.[1]

Research into stem cells grew out of findings by Canadian biologists Ernest McCulloch, James Till and Andrew J. Becker at the University of Toronto and the Ontario Cancer Institute in the 1960s.[2][3] As of 2016[update], the only established medical therapy using stem cells is hematopoietic stem cell transplantation,[4] first performed in 1958 by French oncologist Georges Mathé. Since 1998 however, it has been possible to culture and differentiate human embryonic stem cells (in stem-cell lines). The process of isolating these cells has been controversial, because it typically results in the destruction of the embryo. Sources for isolating ESCs have been restricted in some European countries and Canada, but others such as the UK and China have promoted the research.[5] Somatic cell nuclear transfer is a cloning method that can be used to create a cloned embryo for the use of its embryonic stem cells in stem cell therapy.[6] In 2006, a Japanese team led by Shinya Yamanaka discovered a method to convert mature body cells back into stem cells. These were termed induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs).[7]

History

[edit]The term stem cell was coined by Theodor Boveri and Valentin Haecker in late 19th century.[8] Pioneering works in theory of blood stem cell were conducted in the beginning of 20th century by Artur Pappenheim, Alexander A. Maximow, Franz Ernst Christian Neumann.[8]

The key properties of a stem cell were first defined by Ernest McCulloch and James Till at the University of Toronto and the Ontario Cancer Institute in the early 1960s. They discovered the blood-forming stem cell, the hematopoietic stem cell (HSC), through their pioneering work in mice. McCulloch and Till began a series of experiments in which bone marrow cells were injected into irradiated mice. They observed lumps in the spleens of the mice that were linearly proportional to the number of bone marrow cells injected. They hypothesized that each lump (colony) was a clone arising from a single marrow cell (stem cell). In subsequent work, McCulloch and Till, joined by graduate student Andrew John Becker and senior scientist Louis Siminovitch, confirmed that each lump did in fact arise from a single cell. Their results were published in Nature in 1963. In that same year, Siminovitch was a lead investigator for studies that found colony-forming cells were capable of self-renewal, which is a key defining property of stem cells that Till and McCulloch had theorized.[9]

The first therapy using stem cells was a bone marrow transplant performed by French oncologist Georges Mathé in 1956 on five workers at the Vinča Nuclear Institute in Yugoslavia who had been affected by a criticality accident. The workers all survived.[10]

In 1981, embryonic stem (ES) cells were first isolated and successfully cultured using mouse blastocysts by British biologists Martin Evans and Matthew Kaufman. This allowed the formation of murine genetic models, a system in which the genes of mice are deleted or altered in order to study their function in pathology. In 1991, a process that allowed the human stem cell to be isolated was patented by Ann Tsukamoto. By 1998, human embryonic stem cells were first isolated by American biologist James Thomson, which made it possible to have new transplantation methods or various cell types for testing new treatments. In 2006, Shinya Yamanaka's team in Kyoto, Japan converted fibroblasts into pluripotent stem cells by modifying the expression of only four genes. The feat represents the origin of induced pluripotent stem cells, known as iPS cells.[7]

In 2011, a female maned wolf, run over by a truck, underwent stem cell treatment at the Zoo Brasília, this being the first recorded case of the use of stem cells to heal injuries in a wild animal.[11][12]

Properties

[edit]The classical definition of a stem cell requires that it possesses two properties:

- Self-renewal: the ability to go through numerous cycles of cell growth and cell division, known as cell proliferation, while maintaining the undifferentiated state.

- Potency: the capacity to differentiate into specialized cell types. In the strictest sense, this requires stem cells to be either totipotent or pluripotent—to be able to give rise to any mature cell type, although multipotent or unipotent progenitor cells are sometimes referred to as stem cells. Apart from this, it is said that stem cell function is regulated in a feedback mechanism.

Self-renewal

[edit]Two mechanisms ensure that a stem cell population is maintained (does not shrink in size):

1. Asymmetric cell division: a stem cell divides into one mother cell, which is identical to the original stem cell, and another daughter cell, which is differentiated.

When a stem cell self-renews, it divides and disrupts the undifferentiated state. This self-renewal demands control of cell cycle as well as upkeep of multipotency or pluripotency, which all depends on the stem cell.[13]

H.

Stem cells use telomerase, a protein that restores telomeres, to protect their DNA and extend their cell division limit (the Hayflick limit).[14]

Potency meaning

[edit]

A: Stem cell colonies that are not yet differentiated.

B: Nerve cells, an example of a cell type after differentiation.

Potency specifies the differentiation potential (the potential to differentiate into different cell types) of the stem cell.[15]

- Totipotent (also known as omnipotent) stem cells can differentiate into embryonic and extraembryonic cell types. Such cells can construct a complete, viable organism.[15] These cells are produced from the fusion of an egg and sperm cell. Cells produced by the first few divisions of the fertilized egg are also totipotent.[16]

- Pluripotent stem cells are the descendants of totipotent cells and can differentiate into nearly all cells,[15] i.e. cells derived from any of the three germ layers.[17]

- Multipotent stem cells can differentiate into a number of cell types, but only those of a closely related family of cells.[15]

- Oligopotent stem cells can differentiate into only a few cell types, such as lymphoid or myeloid stem cells.[15]

- Unipotent cells can produce only one cell type, their own,[15] but have the property of self-renewal, which distinguishes them from non-stem cells

Identification

[edit]In practice, stem cells are identified by whether they can regenerate tissue. For example, the defining test for bone marrow or hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) is the ability to transplant the cells and save an individual without HSCs. This demonstrates that the cells can produce new blood cells over a long term. It should also be possible to isolate stem cells from the transplanted individual, which can themselves be transplanted into another individual without HSCs, demonstrating that the stem cell was able to self-renew.

Properties of stem cells can be illustrated in vitro, using methods such as clonogenic assays, in which single cells are assessed for their ability to differentiate and self-renew.[18][19] Stem cells can also be isolated by their possession of a distinctive set of cell surface markers. However, in vitro culture conditions can alter the behavior of cells, making it unclear whether the cells shall behave in a similar manner in vivo. There is considerable debate as to whether some proposed adult cell populations are truly stem cells.[20]

Embryonic

[edit]Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) are the cells of the inner cell mass of a blastocyst, formed prior to implantation in the uterus.[21] In human embryonic development the blastocyst stage is reached 4–5 days after fertilization, at which time it consists of 50–150 cells. ESCs are pluripotent and give rise during development to all derivatives of the three germ layers: ectoderm, endoderm and mesoderm. In other words, they can develop into each of the more than 200 cell types of the adult body when given sufficient and necessary stimulation for a specific cell type. They do not contribute to the extraembryonic membranes or to the placenta.

During embryonic development the cells of the inner cell mass continuously divide and become more specialized. For example, a portion of the ectoderm in the dorsal part of the embryo specializes as 'neurectoderm', which will become the future central nervous system (CNS).[22] Later in development, neurulation causes the neurectoderm to form the neural tube. At the neural tube stage, the anterior portion undergoes encephalization to generate or 'pattern' the basic form of the brain. At this stage of development, the principal cell type of the CNS is considered a neural stem cell.

The neural stem cells self-renew and at some point transition into radial glial progenitor cells (RGPs). Early-formed RGPs self-renew by symmetrical division to form a reservoir group of progenitor cells. These cells transition to a neurogenic state and start to divide asymmetrically to produce a large diversity of many different neuron types, each with unique gene expression, morphological, and functional characteristics. The process of generating neurons from radial glial cells is called neurogenesis. The radial glial cell, has a distinctive bipolar morphology with highly elongated processes spanning the thickness of the neural tube wall. It shares some glial characteristics, most notably the expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP).[23][24] The radial glial cell is the primary neural stem cell of the developing vertebrate CNS, and its cell body resides in the ventricular zone, adjacent to the developing ventricular system. Neural stem cells are committed to the neuronal lineages (neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes), and thus their potency is restricted.[22]

Nearly all research to date has made use of mouse embryonic stem cells (mES) or human embryonic stem cells (hES) derived from the early inner cell mass. Both have the essential stem cell characteristics, yet they require very different environments in order to maintain an undifferentiated state. Mouse ES cells are grown on a layer of gelatin as an extracellular matrix (for support) and require the presence of leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) in serum media. A drug cocktail containing inhibitors to GSK3B and the MAPK/ERK pathway, called 2i, has also been shown to maintain pluripotency in stem cell culture.[25] Human ESCs are grown on a feeder layer of mouse embryonic fibroblasts and require the presence of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF or FGF-2).[26] Without optimal culture conditions or genetic manipulation,[27] embryonic stem cells will rapidly differentiate.

A human embryonic stem cell is also defined by the expression of several transcription factors and cell surface proteins. The transcription factors Oct-4, Nanog, and Sox2 form the core regulatory network that ensures the suppression of genes that lead to differentiation and the maintenance of pluripotency.[28] The cell surface antigens most commonly used to identify hES cells are the glycolipids stage specific embryonic antigen 3 and 4, and the keratan sulfate antigens Tra-1-60 and Tra-1-81. The molecular definition of a stem cell includes many more proteins and continues to be a topic of research.[29]

By using human embryonic stem cells to produce specialized cells like nerve cells or heart cells in the lab, scientists can gain access to adult human cells without taking tissue from patients. They can then study these specialized adult cells in detail to try to discern complications of diseases, or to study cell reactions to proposed new drugs.

Because of their combined abilities of unlimited expansion and pluripotency, embryonic stem cells remain a theoretically potential source for regenerative medicine and tissue replacement after injury or disease.,[30] however, there are currently no approved treatments using ES cells. The first human trial was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in January 2009.[31] However, the human trial was not initiated until October 13, 2010, in Atlanta for spinal cord injury research. On November 14, 2011, the company conducting the trial (Geron Corporation) announced that it will discontinue further development of its stem cell programs.[32] Differentiating ES cells into usable cells while avoiding transplant rejection are just a few of the hurdles that embryonic stem cell researchers still face.[33] Embryonic stem cells, being pluripotent, require specific signals for correct differentiation – if injected directly into another body, ES cells will differentiate into many different types of cells, causing a teratoma. Many nations currently have moratoria or limitations on either human ES cell research or the production of new human ES cell lines due to their ethical controversies.

-

Human embryonic stem cell colony on mouse embryonic fibroblast feeder layer

The use of embryonic stem cells has generated significant ethical and political controversy. Central to the debate is the moral status of the human embryo, as deriving ES typically involves the destruction of early-stage embryos. Critics argue that this practice violates the sanctity of human life, and therefore is unacceptable.

Mesenchymal stem cells

[edit]

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) or mesenchymal stromal cells, also known as medicinal signaling cells are known to be multipotent, which can be found in adult tissues, for example, in the muscle, liver, bone marrow and adipose tissue. Mesenchymal stem cells usually function as structural support in various organs as mentioned above, and control the movement of substances. MSC can differentiate into numerous cell categories as an illustration of adipocytes, osteocytes, and chondrocytes, derived by the mesodermal layer.[34] Where the mesoderm layer provides an increase to the body's skeletal elements, such as relating to the cartilage or bone. The term "meso" means middle, infusion originated from the Greek, signifying that mesenchymal cells are able to range and travel in early embryonic growth among the ectodermal and endodermal layers. This mechanism helps with space-filling thus, key for repairing wounds in adult organisms that have to do with mesenchymal cells in the dermis (skin), bone, or muscle.[35]

Mesenchymal stem cells are known to be essential for regenerative medicine. They are broadly studied in clinical trials. Since they are easily isolated and obtain high yield, high plasticity, which makes able to facilitate inflammation and encourage cell growth, cell differentiation, and restoring tissue derived from immunomodulation and immunosuppression. MSC comes from the bone marrow, which requires an aggressive procedure when it comes to isolating the quantity and quality of the isolated cell, and it varies by how old the donor. When comparing the rates of MSC in the bone marrow aspirates and bone marrow stroma, the aspirates tend to have lower rates of MSC than the stroma. MSC are known to be heterogeneous, and they express a high level of pluripotent markers when compared to other types of stem cells, such as embryonic stem cells.[34] MSCs injection leads to wound healing primarily through stimulation of angiogenesis.[36]

Cell cycle control

[edit]Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) have the ability to divide indefinitely while keeping their pluripotency, which is made possible through specialized mechanisms of cell cycle control.[37] Compared to proliferating somatic cells, ESCs have unique cell cycle characteristics—such as rapid cell division caused by shortened G1 phase, absent G0 phase, and modifications in cell cycle checkpoints—which leaves the cells mostly in S phase at any given time.[37][38] ESCs' rapid division is demonstrated by their short doubling time, which ranges from 8 to 10 hours, whereas somatic cells have doubling time of approximately 20 hours or longer.[39] As cells differentiate, these properties change: G1 and G2 phases lengthen, leading to longer cell division cycles. This suggests that a specific cell cycle structure may contribute to the establishment of pluripotency.[37]

Particularly because G1 phase is the phase in which cells have increased sensitivity to differentiation, shortened G1 is one of the key characteristics of ESCs and plays an important role in maintaining undifferentiated phenotype. Although the exact molecular mechanism remains only partially understood, several studies have shown insight on how ESCs progress through G1—and potentially other phases—so rapidly.[38]

The cell cycle is regulated by complex network of cyclins, cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdk), cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (Cdkn), pocket proteins of the retinoblastoma (Rb) family, and other accessory factors.[39] Foundational insight into the distinctive regulation of ESC cell cycle was gained by studies on mouse ESCs (mESCs).[38] mESCs showed a cell cycle with highly abbreviated G1 phase, which enabled cells to rapidly alternate between M phase and S phase. In a somatic cell cycle, oscillatory activity of Cyclin-Cdk complexes is observed in sequential action, which controls crucial regulators of the cell cycle to induce unidirectional transitions between phases: Cyclin D and Cdk4/6 are active in the G1 phase, while Cyclin E and Cdk2 are active during the late G1 phase and S phase; and Cyclin A and Cdk2 are active in the S phase and G2, while Cyclin B and Cdk1 are active in G2 and M phase.[39] However, in mESCs, this typically ordered and oscillatory activity of Cyclin-Cdk complexes is absent. Rather, the Cyclin E/Cdk2 complex is constitutively active throughout the cycle, keeping retinoblastoma protein (pRb) hyperphosphorylated and thus inactive. This allows for direct transition from M phase to the late G1 phase, leading to absence of D-type cyclins and therefore a shortened G1 phase.[38] Cdk2 activity is crucial for both cell cycle regulation and cell-fate decisions in mESCs; downregulation of Cdk2 activity prolongs G1 phase progression, establishes a somatic cell-like cell cycle, and induces expression of differentiation markers.[40]

In human ESCs (hESCs), the duration of G1 is dramatically shortened. This has been attributed to high mRNA levels of G1-related Cyclin D2 and Cdk4 genes and low levels of cell cycle regulatory proteins that inhibit cell cycle progression at G1, such as p21CipP1, p27Kip1, and p57Kip2.[37][41] Furthermore, regulators of Cdk4 and Cdk6 activity, such as members of the Ink family of inhibitors (p15, p16, p18, and p19), are expressed at low levels or not at all. Thus, similar to mESCs, hESCs show high Cdk activity, with Cdk2 exhibiting the highest kinase activity. Also similar to mESCs, hESCs demonstrate the importance of Cdk2 in G1 phase regulation by showing that G1 to S transition is delayed when Cdk2 activity is inhibited and G1 is arrest when Cdk2 is knocked down.[37] However unlike mESCs, hESCs have a functional G1 phase. hESCs show that the activities of Cyclin E/Cdk2 and Cyclin A/Cdk2 complexes are cell cycle-dependent and the Rb checkpoint in G1 is functional.[39]

ESCs are also characterized by G1 checkpoint non-functionality, even though the G1 checkpoint is crucial for maintaining genomic stability. In response to DNA damage, ESCs do not stop in G1 to repair DNA damages but instead, depend on S and G2/M checkpoints or undergo apoptosis. The absence of G1 checkpoint in ESCs allows for the removal of cells with damaged DNA, hence avoiding potential mutations from inaccurate DNA repair.[37] Consistent with this idea, ESCs are hypersensitive to DNA damage to minimize mutations passed onto the next generation.[39]

Fetal

[edit]The primitive stem cells located in the organs of fetuses are referred to as fetal stem cells.[42]

There are two types of fetal stem cells:

- Fetal proper stem cells come from the tissue of the fetus proper and are generally obtained after an abortion. These stem cells are not immortal but have a high level of division and are multipotent.

- Extraembryonic fetal stem cells come from extraembryonic membranes, and are generally not distinguished from adult stem cells. These stem cells are acquired after birth, they are not immortal but have a high level of cell division, and are pluripotent.[43]

Adult

[edit]

Adult stem cells, also called somatic (from Greek σωματικóς, "of the body") stem cells, are stem cells which maintain and repair the tissue in which they are found.[44]

There are four known accessible sources of autologous adult stem cells in humans:

- Bone marrow, which requires extraction by harvesting, usually from pelvic bones via surgery.[45]

- Adipose tissue (fat cells), which requires extraction by liposuction.[46]

- Blood, which requires extraction through apheresis, wherein blood is drawn from the donor (similar to a blood donation), and passed through a machine that extracts the stem cells and returns other portions of the blood to the donor.[47]

- Menstrual fluid[48]

Stem cells can also be taken from umbilical cord blood just after birth. Of all stem cell types, autologous harvesting involves the least risk. By definition, autologous cells are obtained from one's own body, just as one may bank their own blood for elective surgical procedures.[citation needed]

Pluripotent adult stem cells are rare and generally small in number, but they can be found in umbilical cord blood and other tissues.[49] Bone marrow is a rich source of adult stem cells,[50] which have been used in treating several conditions including liver cirrhosis,[51] chronic limb ischemia[52] and endstage heart failure.[53] The quantity of bone marrow stem cells declines with age and is greater in males than females during reproductive years.[54] Much adult stem cell research to date has aimed to characterize their potency and self-renewal capabilities.[55] DNA damage accumulates with age in both stem cells and the cells that comprise the stem cell environment. This accumulation is considered to be responsible, at least in part, for increasing stem cell dysfunction with aging (see DNA damage theory of aging).[56]

Most adult stem cells are lineage-restricted (multipotent) and are generally referred to by their tissue origin (mesenchymal stem cell, adipose-derived stem cell, endothelial stem cell, dental pulp stem cell, etc.).[57][58] Muse cells (multi-lineage differentiating stress enduring cells) are a recently discovered pluripotent stem cell type found in multiple adult tissues, including adipose, dermal fibroblasts, and bone marrow. While rare, muse cells are identifiable by their expression of SSEA-3, a marker for undifferentiated stem cells, and general mesenchymal stem cells markers such as CD90, CD105. When subjected to single cell suspension culture, the cells will generate clusters that are similar to embryoid bodies in morphology as well as gene expression, including canonical pluripotency markers Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog.[59]

Adult stem cell treatments have been successfully used for many years to treat leukemia and related bone/blood cancers through bone marrow transplants.[60] Adult stem cells are also used in veterinary medicine to treat tendon and ligament injuries in horses.[61]

The use of adult stem cells in research and therapy is not as controversial as the use of embryonic stem cells, because the production of adult stem cells does not require the destruction of an embryo. Additionally, in instances where adult stem cells are obtained from the intended recipient (an autograft), the risk of rejection is essentially non-existent. Consequently, more US government funding is being provided for adult stem cell research.[62]

With the increasing demand of human adult stem cells for both research and clinical purposes (typically 1–5 million cells per kg of body weight are required per treatment) it becomes of utmost importance to bridge the gap between the need to expand the cells in vitro and the capability of harnessing the factors underlying replicative senescence. Adult stem cells are known to have a limited lifespan in vitro and to enter replicative senescence almost undetectably upon starting in vitro culturing.[63]

Hematopoietic stem cells

[edit]Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are vulnerable to DNA damage and mutations that increase with age.[64] This vulnerability may explain the increased risk of slow growing blood cancers (myeloid malignancies) in the elderly.[64] Several factors appear to influence HSC aging including responses to the production of reactive oxygen species that may cause DNA damage and genetic mutations as well as altered epigenetic profiling.[65]

Amniotic

[edit]Also called perinatal stem cells, these multipotent stem cells are found in amniotic fluid and umbilical cord blood. These stem cells are very active, expand extensively without feeders and are not tumorigenic. Amniotic stem cells are multipotent and can differentiate in cells of adipogenic, osteogenic, myogenic, endothelial, hepatic and also neuronal lines.[66] Amniotic stem cells are a topic of active research.

Use of stem cells from amniotic fluid overcomes the ethical objections to using human embryos as a source of cells. Roman Catholic teaching forbids the use of embryonic stem cells in experimentation; accordingly, the Vatican newspaper "Osservatore Romano" called amniotic stem cells "the future of medicine".[67]

It is possible to collect amniotic stem cells for donors or for autologous use: the first US amniotic stem cells bank[68][69] was opened in 2009 in Medford, MA, by Biocell Center Corporation[70][71][72] and collaborates with various hospitals and universities all over the world.[73]

Induced pluripotent

[edit]Adult stem cells have limitations with their potency; unlike embryonic stem cells (ESCs), they are not able to differentiate into cells from all three germ layers. As such, they are deemed multipotent.

However, reprogramming allows for the creation of pluripotent cells, induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), from adult cells. These are not adult stem cells, but somatic cells (e.g. epithelial cells) reprogrammed to give rise to cells with pluripotent capabilities. Using genetic reprogramming with protein transcription factors, pluripotent stem cells with ESC-like capabilities have been derived.[74][75][76] The first demonstration of induced pluripotent stem cells was conducted by Shinya Yamanaka and his colleagues at Kyoto University.[77] They used the transcription factors Oct3/4, Sox2, c-Myc, and Klf4 to reprogram mouse fibroblast cells into pluripotent cells.[74][78] Subsequent work used these factors to induce pluripotency in human fibroblast cells.[79] Junying Yu, James Thomson, and their colleagues at the University of Wisconsin–Madison used a different set of factors, Oct4, Sox2, Nanog and Lin28, and carried out their experiments using cells from human foreskin.[74][80] However, they were able to replicate Yamanaka's finding that inducing pluripotency in human cells was possible.

Induced pluripotent stem cells differ from embryonic stem cells. They share many similar properties, such as pluripotency and differentiation potential, the expression of pluripotency genes, epigenetic patterns, embryoid body and teratoma formation, and viable chimera formation,[77][78] but there are many differences within these properties. The chromatin of iPSCs appears to be more "closed" or methylated than that of ESCs.[77][78] Similarly, the gene expression pattern between ESCs and iPSCs, or even iPSCs sourced from different origins.[77] There are thus questions about the "completeness" of reprogramming and the somatic memory of induced pluripotent stem cells. Despite this, inducing somatic cells to be pluripotent appears to be viable.

As a result of the success of these experiments, Ian Wilmut, who helped create the first cloned animal Dolly the Sheep, has announced that he will abandon somatic cell nuclear transfer as an avenue of research.[81]

The ability to induce pluripotency benefits developments in tissue engineering. By providing a suitable scaffold and microenvironment, iPSC can be differentiated into cells of therapeutic application, and for in vitro models to study toxins and pathogenesis.[82]

Induced pluripotent stem cells provide several therapeutic advantages. Like ESCs, they are pluripotent. They thus have great differentiation potential; theoretically, they could produce any cell within the human body (if reprogramming to pluripotency was "complete").[77] Moreover, unlike ESCs, they potentially could allow doctors to create a pluripotent stem cell line for each individual patient.[83] Frozen blood samples can be used as a valuable source of induced pluripotent stem cells.[84] Patient specific stem cells allow for the screening for side effects before drug treatment, as well as the reduced risk of transplantation rejection.[83] Despite their current limited use therapeutically, iPSCs hold great potential for future use in medical treatment and research.

Cell cycle control

[edit]The key factors controlling the cell cycle also regulate pluripotency. Thus, manipulation of relevant genes can maintain pluripotency and reprogram somatic cells to an induced pluripotent state.[39] However, reprogramming of somatic cells is often low in efficiency and considered stochastic.[85]

With the idea that a more rapid cell cycle is a key component of pluripotency, reprogramming efficiency can be improved. Methods for improving pluripotency through manipulation of cell cycle regulators include: overexpression of Cyclin D/Cdk4, phosphorylation of Sox2 at S39 and S253, overexpression of Cyclin A and Cyclin E, knockdown of Rb, and knockdown of members of the Cip/Kip family or the Ink family.[39] Furthermore, reprogramming efficiency is correlated with the number of cell divisions happened during the stochastic phase, which is suggested by the growing inefficiency of reprogramming of older or slow diving cells.[86]

Lineage

[edit]Lineage is an important procedure to analyze developing embryos. Since cell lineages shows the relationship between cells at each division. This helps in analyzing stem cell lineages along the way which helps recognize stem cell effectiveness, lifespan, and other factors. With the technique of cell lineage mutant genes can be analyzed in stem cell clones that can help in genetic pathways. These pathways can regulate how the stem cell perform.[87]

To ensure self-renewal, stem cells undergo two types of cell division (see Stem cell division and differentiation diagram). Symmetric division gives rise to two identical daughter cells both endowed with stem cell properties. Asymmetric division, on the other hand, produces only one stem cell and a progenitor cell with limited self-renewal potential. Progenitors can go through several rounds of cell division before terminally differentiating into a mature cell. It is possible that the molecular distinction between symmetric and asymmetric divisions lies in differential segregation of cell membrane proteins (such as receptors) between the daughter cells.[88]

An alternative theory is that stem cells remain undifferentiated due to environmental cues in their particular niche. Stem cells differentiate when they leave that niche or no longer receive those signals. Studies in Drosophila germarium have identified the signals decapentaplegic and adherens junctions that prevent germarium stem cells from differentiating.[89][90]

In the United States, Executive Order 13505 established that federal money can be used for research in which approved human embryonic stem-cell (hESC) lines are used, but it cannot be used to derive new lines.[91] The National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guidelines on Human Stem Cell Research, effective July 7, 2009, implemented the Executive Order 13505 by establishing criteria which hESC lines must meet to be approved for funding.[92] The NIH Human Embryonic Stem Cell Registry can be accessed online and has updated information on cell lines eligible for NIH funding.[93] There are 486 approved lines as of January 2022.[94]

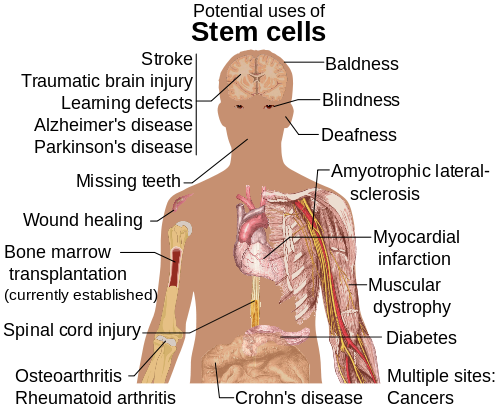

Therapies

[edit]Stem cell therapy is the use of stem cells to treat or prevent a disease or condition. Bone marrow transplant is a form of stem cell therapy that has been used for many years because it has proven to be effective in clinical trials.[95][96] Stem cell implantation may help in strengthening the left-ventricle of the heart, as well as retaining the heart tissue to patients who have suffered from heart attacks in the past.[97]

For over 50 years, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) has been used to treat people with conditions such as leukaemia and lymphoma; this is the only widely practiced form of stem-cell therapy.[95][96][98] As of 2016[update], the only established therapy using stem cells is hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.[4] This usually takes the form of a bone-marrow transplantation, but the cells can also be derived from umbilical cord blood. Research is underway to develop various sources for stem cells as well as to apply stem-cell treatments for neurodegenerative diseases[99][30]>[100] and conditions such as diabetes and heart disease.

Advantages

[edit]Stem cell treatments may lower symptoms of the disease or condition that is being treated. The lowering of symptoms may allow patients to reduce the drug intake of the disease or condition. Stem cell treatment may also provide knowledge for society to further stem cell understanding and future treatments.[101] The physicians' creed would be to do no injury, and stem cells make that simpler than ever before. Surgical processes by their character are harmful. Tissue has to be dropped as a way to reach a successful outcome. One may prevent the dangers of surgical interventions using stem cells. Additionally, there's a possibility of disease, and whether the procedure fails, further surgery may be required. Risks associated with anesthesia can also be eliminated with stem cells.[102] On top of that, stem cells have been harvested from the patient's body and redeployed in which they're wanted. Since they come from the patient's own body, this is referred to as an autologous treatment. Autologous remedies are thought to be the safest because there's likely zero probability of donor substance rejection.

Disadvantages

[edit]Stem cell treatments may require immunosuppression because of a requirement for radiation before the transplant to remove the person's previous cells, or because the patient's immune system may target the stem cells. One approach to avoid the second possibility is to use stem cells from the same patient who is being treated.

Pluripotency in certain stem cells could also make it difficult to obtain a specific cell type. It is also difficult to obtain the exact cell type needed, because not all cells in a population differentiate uniformly. Undifferentiated cells can create tissues other than desired types.[103]

Some stem cells form tumors after transplantation;[104] pluripotency is linked to tumor formation especially in embryonic stem cells, fetal proper stem cells, induced pluripotent stem cells. Fetal proper stem cells form tumors despite multipotency.[105]

Ethical concerns are also raised about the practice of using or researching embryonic stem cells. Harvesting cells from the blastocyst results in the death of the blastocyst. The concern is whether or not the blastocyst should be considered as a human life.[106] The debate on this issue is mainly a philosophical one, not a scientific one.

Stem cell tourism

[edit]Stem cell tourism is the part of the medical tourism industry in which patients travel to obtain stem cell procedures.[107]

The United States has had an explosion of "stem cell clinics".[108] Stem cell procedures are highly profitable for clinics. The advertising sounds authoritative but the efficacy and safety of the procedures is unproven. Patients sometimes experience complications, such as spinal tumors[109] and death. The high expense can also lead to financial problems.[109] According to researchers, there is a need to educate the public, patients, and doctors about this issue.[110]

According to the International Society for Stem Cell Research, the largest academic organization that advocates for stem cell research, stem cell therapies are under development and cannot yet be said to be proven.[111][112] Doctors should inform patients that clinical trials continue to investigate whether these therapies are safe and effective but that unethical clinics present them as proven.[113]

Research

[edit]Some of the fundamental patents covering human embryonic stem cells are owned by the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation (WARF) – they are patents 5,843,780, 6,200,806, and 7,029,913 invented by James A. Thomson. WARF does not enforce these patents against academic scientists, but does enforce them against companies.[114]

In 2006, a request for the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) to re-examine the three patents was filed by the Public Patent Foundation[115] on behalf of its client, the non-profit patent-watchdog group Consumer Watchdog (formerly the Foundation for Taxpayer and Consumer Rights).[114] In the re-examination process, which involves several rounds of discussion between the USPTO and the parties, the USPTO initially agreed with Consumer Watchdog and rejected all the claims in all three patents,[116] however in response, WARF amended the claims of all three patents to make them more narrow, and in 2008 the USPTO found the amended claims in all three patents to be patentable. The decision on one of the patents (7,029,913) was appealable, while the decisions on the other two were not.[117][118] Consumer Watchdog appealed the granting of the '913 patent to the USPTO's Board of Patent Appeals and Interferences (BPAI) which granted the appeal, and in 2010 the BPAI decided that the amended claims of the '913 patent were not patentable.[119] However, WARF was able to re-open prosecution of the case and did so, amending the claims of the '913 patent again to make them more narrow, and in January 2013 the amended claims were allowed.[120]

In July 2013, Consumer Watchdog announced that it would appeal the decision to allow the claims of the '913 patent to the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC), the federal appeals court that hears patent cases.[121] At a hearing in December 2013, the CAFC raised the question of whether Consumer Watchdog had legal standing to appeal; the case could not proceed until that issue was resolved.[122]

Conditions

[edit]

Diseases and conditions where stem cell treatment is being investigated include:

- Diabetes[123]

- Androgenic Alopecia and hair loss[124][125]

- Rheumatoid arthritis[123]

- Parkinson's disease[123]

- Alzheimer's disease[123]

- Respiratory disease[126]

- Osteoarthritis[123]

- Stroke and traumatic brain injury repair[127]

- Learning disability due to congenital disorder[128]

- Spinal cord injury repair[129]

- Heart infarction[130]

- Anti-cancer treatments[127]

- Baldness reversal[131]

- Replace missing teeth[132]

- Repair hearing[133]

- Restore vision[134] and repair damage to the cornea[135]

- Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis[136]

- Crohn's disease[137]

- Wound healing[138]

- Male infertility due to absence of spermatogonial stem cells.[139] In recent studies, scientists have found a way to solve this problem by reprogramming a cell and turning it into a spermatozoon. Other studies have proven the restoration of spermatogenesis by introducing human iPSC cells in mice testicles. This could mean the end of azoospermia.[140]

- Female infertility: oocytes made from embryonic stem cells. Scientists have found the ovarian stem cells, a rare type of cells (0.014%) found in the ovary. They could be used as a treatment not only for infertility, but also for premature ovarian insufficiency (POI).[141] New research posted in Science Direct suggests that ovarian follicles could be triggered to grow in the ovarian environment by using stem cells present in bone marrow. This study was conducted by infusing human bone marrow stem cells into immune-deficient mice to improve fertilization.[142] Another study conducted using mice with damaged ovarian function from chemothearpy found that in vivo therapy with bone marrow stem cells can heal the damaged ovaries.[143] Both of these studies are proof-of-concept and need to be furthered tested, but they have the possibility improve fertility for individuals who have POI from chemotherapy treatment.

- Critical Limb Ischemia[144]

Production

[edit]Research is underway to develop various sources for stem cells.[145]

Organoids

[edit]Research is attempting to generating organoids using stem cells, which would allow for further understanding of human development, organogenesis, and modeling of human diseases.[146] Engineered 'synthetic organizer' (SO) cells can instruct stem cells to grow into specific tissues and organs. The program used native and synthetic cell adhesion protein molecules (CAMs) that help make cells sticky. The organizer cells self-assembled around mouse ESCs. These cells were engineered to produce morphogens (signaling molecules) that direct cellular development based on their concentration. Delivered morphogens disperse, leaving higher concentrations closer to the source and lower concentrations further away. These gradients signal cells' ultimate roles, such as nerve, skin cell, or connective tissue. The engineered organizer cells were also fitted with a chemical switch that enabled the researchers to turn the delivery of cellular instructions on and off, as well as a 'suicide switch' for eliminating the cells when needed. SOs carry spatial and biochemical information, allowing considerable discretion in organoid formation.[147]

Risks

[edit]Hepatotoxicity and drug-induced liver injury account for a substantial number of failures of new drugs in development and market withdrawal, highlighting the need for screening assays such as stem cell-derived hepatocyte-like cells, that are capable of detecting toxicity early in the drug development process.[148]

Dormancy

[edit]In August 2021, researchers in the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre at the University Health Network published their discovery of a dormancy mechanism in key stem cells which could help develop cancer treatments in the future.[149]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Atala A, Lanza R (2012). Handbook of Stem Cells. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-385943-3.

- ^ Becker AJ, McCulloch EA, Till JE (February 1963). "Cytological demonstration of the clonal nature of spleen colonies derived from transplanted mouse marrow cells". Nature. 197 (4866): 452–4. Bibcode:1963Natur.197..452B. doi:10.1038/197452a0. hdl:1807/2779. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 13970094. S2CID 11106827.

- ^ Siminovitch L, McCulloch EA, Till JE (December 1963). "The distribution of colony-forming cells among spleen colonies". Journal of Cellular and Comparative Physiology. 62 (3): 327–336. doi:10.1002/jcp.1030620313. hdl:1807/2778. PMID 14086156. S2CID 43875977.

- ^ a b Müller AM, Huppertz S, Henschler R (July 2016). "Hematopoietic Stem Cells in Regenerative Medicine: Astray or on the Path?". Transfusion Medicine and Hemotherapy. 43 (4): 247–254. doi:10.1159/000447748. PMC 5040947. PMID 27721700.

- ^ Ralston, Michelle (17 July 2008). "Stem Cell Research Around the World". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project.

- ^ Tuch, B. E. (September 2006). "Stem cells: a clinical update". Australian Family Physician. 35 (9): 719–721. PMID 16969445. ProQuest 216301343.

- ^ a b Ferreira L (2014-01-03). "Stem Cells: A Brief History and Outlook". Stem Cells: A Brief History and Outlook – Science in the News. WordPress. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ a b Ramalho-Santos, Miguel; Willenbring, Holger (June 2007). "On the Origin of the Term 'Stem Cell'". Cell Stem Cell. 1 (1): 35–38. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2007.05.013. PMID 18371332.

- ^ MacPherson C. "The Accidental Discovery of Stem Cells". USask News. University of Saskatchewan. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ Johnston, Wm. Robert. "Vinca reactor accident, 1958". www.johnstonsarchive.net. Archived from the original on 27 January 2011. Retrieved 2024-12-28.

- ^ Boyle, Rebecca (2011-01-15). "Injured Brazilian Wolf Is First Wild Animal Treated With Stem Cells". Popular Science. Retrieved 2024-12-28.

- ^ suporte (2011-01-11). "Tratamento". CFMV (in Brazilian Portuguese). Conselho Federal de Medicina Veterinária. Retrieved 2024-12-28.

- ^ He S, Nakada D, Morrison SJ (2009). "Mechanisms of stem cell self-renewal". Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 25: 377–406. doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113248. PMID 19575646.

- ^ Cong YS, Wright WE, Shay JW (September 2002). "Human telomerase and its regulation". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 66 (3): 407–425, table of contents. doi:10.1128/MMBR.66.3.407-425.2002. PMC 120798. PMID 12208997.

- ^ a b c d e f Schöler HR (2007). "The Potential of Stem Cells: An Inventory". In Nikolaus Knoepffler, Dagmar Schipanski, Stefan Lorenz Sorgner (eds.). Humanbiotechnology as Social Challenge. Ashgate Publishing. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-7546-5755-2.

- ^ Mitalipov S, Wolf D (2009). "Totipotency, pluripotency and nuclear reprogramming". Engineering of Stem Cells. Advances in Biochemical Engineering/Biotechnology. Vol. 114. Springer. pp. 185–199. Bibcode:2009esc..book..185M. doi:10.1007/10_2008_45. ISBN 978-3-540-88805-5. PMC 2752493. PMID 19343304.

- ^ Ulloa-Montoya F, Verfaillie CM, Hu WS (July 2005). "Culture systems for pluripotent stem cells". Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering. 100 (1): 12–27. doi:10.1263/jbb.100.12. PMID 16233846.

- ^ Friedenstein AJ, Deriglasova UF, Kulagina NN, Panasuk AF, Rudakowa SF, Luriá EA, Ruadkow IA (1974). "Precursors for fibroblasts in different populations of hematopoietic cells as detected by the in vitro colony assay method". Experimental Hematology. 2 (2): 83–92. PMID 4455512. INIST PASCAL7536501060 NAID 10025700209.

- ^ Friedenstein AJ, Gorskaja JF, Kulagina NN (September 1976). "Fibroblast precursors in normal and irradiated mouse hematopoietic organs". Experimental Hematology. 4 (5): 267–274. PMID 976387.

- ^ Sekhar L, Bisht N (2006-09-01). "Stem Cell Therapy". Apollo Medicine. 3 (3): 271–6. doi:10.1016/S0976-0016(11)60209-3.

- ^ Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, Waknitz MA, Swiergiel JJ, Marshall VS, Jones JM (November 1998). "Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts". Science. 282 (5391): 1145–47. Bibcode:1998Sci...282.1145T. doi:10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. PMID 9804556.

- ^ a b Gilbert, Scott F. (2014). Developmental Biology. Sinauer Associates. ISBN 978-0-87893-978-7.[page needed]

- ^ Rakic P (October 2009). "Evolution of the neocortex: a perspective from developmental biology". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 10 (10): 724–735. doi:10.1038/nrn2719. PMC 2913577. PMID 19763105.

- ^ Noctor SC, Flint AC, Weissman TA, Dammerman RS, Kriegstein AR (February 2001). "Neurons derived from radial glial cells establish radial units in neocortex". Nature. 409 (6821): 714–720. Bibcode:2001Natur.409..714N. doi:10.1038/35055553. PMID 11217860. S2CID 3041502.

- ^ Ying QL, Wray J, Nichols J, Batlle-Morera L, Doble B, Woodgett J, Cohen P, Smith A (May 2008). "The ground state of embryonic stem cell self-renewal". Nature. 453 (7194): 519–523. Bibcode:2008Natur.453..519Y. doi:10.1038/nature06968. PMC 5328678. PMID 18497825.

- ^ "Culture of Human Embryonic Stem Cells (hESC)". National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 2010-01-06. Retrieved 2010-03-07.

- ^ Chambers I, Colby D, Robertson M, Nichols J, Lee S, Tweedie S, Smith A (May 2003). "Functional expression cloning of Nanog, a pluripotency sustaining factor in embryonic stem cells". Cell. 113 (5): 643–655. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00392-1. hdl:1842/843. PMID 12787505. S2CID 2236779.

- ^ Boyer LA, Lee TI, Cole MF, Johnstone SE, Levine SS, Zucker JP, Guenther MG, Kumar RM, Murray HL, Jenner RG, Gifford DK, Melton DA, Jaenisch R, Young RA (September 2005). "Core transcriptional regulatory circuitry in human embryonic stem cells". Cell. 122 (6): 947–956. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.020. PMC 3006442. PMID 16153702.

- ^ Adewumi O, Aflatoonian B, Ahrlund-Richter L, Amit M, Andrews PW, Beighton G, et al. (The International Stem Cell Initiative) (July 2007). "Characterization of human embryonic stem cell lines by the International Stem Cell Initiative". Nature Biotechnology. 25 (7): 803–816. doi:10.1038/nbt1318. PMID 17572666. S2CID 13780999.

- ^ a b Mahla RS (2016). "Stem Cells Applications in Regenerative Medicine and Disease Therapeutics". International Journal of Cell Biology. 2016 (7): 1–24. doi:10.1155/2016/6940283. PMC 4969512. PMID 27516776.

- ^ Winslow R, Mundy A (23 January 2009). "First Embryonic Stem-Cell Trial Gets Approval from the FDA". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "Embryonic Stem Cell Therapy At Risk? Geron Ends Clinical Trial". ScienceDebate.com. Archived from the original on 2014-08-22. Retrieved 2011-12-11.

- ^ Wu DC, Boyd AS, Wood KJ (May 2007). "Embryonic stem cell transplantation: potential applicability in cell replacement therapy and regenerative medicine". Frontiers in Bioscience. 12 (8–12): 4525–35. doi:10.2741/2407. PMID 17485394. S2CID 6355307.

- ^ a b Zomer HD, Vidane AS, Gonçalves NN, Ambrósio CE (2015-09-28). "Mesenchymal and induced pluripotent stem cells: general insights and clinical perspectives". Stem Cells and Cloning: Advances and Applications. 8: 125–134. doi:10.2147/SCCAA.S88036. PMC 4592031. PMID 26451119.

- ^ Caplan AI (September 1991). "Mesenchymal stem cells". Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 9 (5): 641–650. doi:10.1002/jor.1100090504. PMID 1870029. S2CID 22606668.

- ^ Krasilnikova, O. A.; Baranovskii, D. S.; Lyundup, A. V.; Shegay, P. V.; Kaprin, A. D.; Klabukov, I. D. (2022-04-27). "Stem and Somatic Cell Monotherapy for the Treatment of Diabetic Foot Ulcers: Review of Clinical Studies and Mechanisms of Action". Stem Cell Reviews and Reports. 18 (6): 1974–85. doi:10.1007/s12015-022-10379-z. ISSN 2629-3277. PMID 35476187. S2CID 248402820.

- ^ a b c d e f Koledova Z, Krämer A, Kafkova LR, Divoky V (November 2010). "Cell-cycle regulation in embryonic stem cells: centrosomal decisions on self-renewal". Stem Cells and Development. 19 (11): 1663–78. doi:10.1089/scd.2010.0136. PMID 20594031.

- ^ a b c d Barta T, Dolezalova D, Holubcova Z, Hampl A (March 2013). "Cell cycle regulation in human embryonic stem cells: links to adaptation to cell culture". Experimental Biology and Medicine. 238 (3): 271–5. doi:10.1177/1535370213480711. PMID 23598972. S2CID 2028793.

- ^ a b c d e f g Zaveri L, Dhawan J (2018). "Cycling to Meet Fate: Connecting Pluripotency to the Cell Cycle". Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 6 57. doi:10.3389/fcell.2018.00057. PMC 6020794. PMID 29974052.

- ^ Koledova Z, Kafkova LR, Calabkova L, Krystof V, Dolezel P, Divoky V (February 2010). "Cdk2 inhibition prolongs G1 phase progression in mouse embryonic stem cells". Stem Cells and Development. 19 (2): 181–194. doi:10.1089/scd.2009.0065. PMID 19737069.

- ^ Becker KA, Ghule PN, Therrien JA, Lian JB, Stein JL, van Wijnen AJ, Stein GS (December 2006). "Self-renewal of human embryonic stem cells is supported by a shortened G1 cell cycle phase". Journal of Cellular Physiology. 209 (3): 883–893. doi:10.1002/jcp.20776. PMID 16972248. S2CID 24908771.

- ^ Ariff Bongso; Eng Hin Lee, eds. (2005). "Stem cells: their definition, classification and sources". Stem Cells: From Benchtop to Bedside. World Scientific. p. 5. ISBN 978-981-256-126-8. OCLC 443407924.

- ^ Moore, Keith L.; Persaud, T. V. N.; Torchia, Mark G. (2013). Before We are Born: Essentials of Embryology and Birth Defects. Saunders/Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4377-2001-3.[page needed]

- ^ "What is a stem cell". anthonynolan.org. Anthony Nolan. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ "Bone marrow (stem cell) donation: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2021-10-17.

- ^ Coughlin RP, Oldweiler A, Mickelson DT, Moorman CT (October 2017). "Adipose-Derived Stem Cell Transplant Technique for Degenerative Joint Disease". Arthroscopy Techniques. 6 (5): e1761 – e1766. doi:10.1016/j.eats.2017.06.048. PMC 5795060. PMID 29399463.

- ^ "autologous stem cell transplant". www.cancer.gov. 2011-02-02. Retrieved 2022-06-26.

- ^ Lv, Haining; Hu, Yali; Cui, Zhanfeng; Jia, Huidong (2018). "Human menstrual blood: a renewable and sustainable source of stem cells for regenerative medicine". Stem Cell Research & Therapy. 9 (1) 325. doi:10.1186/s13287-018-1067-y. PMC 6249727. PMID 30463587.

- ^ Ratajczak MZ, Machalinski B, Wojakowski W, Ratajczak J, Kucia M (May 2007). "A hypothesis for an embryonic origin of pluripotent Oct-4(+) stem cells in adult bone marrow and other tissues". Leukemia. 21 (5): 860–7. doi:10.1038/sj.leu.2404630. PMID 17344915. S2CID 21433689.

- ^ Narasipura SD, Wojciechowski JC, Charles N, Liesveld JL, King MR (January 2008). "P-Selectin coated microtube for enrichment of CD34+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells from human bone marrow". Clinical Chemistry. 54 (1): 77–85. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2007.089896. PMID 18024531.

- ^ Terai S, Ishikawa T, Omori K, Aoyama K, Marumoto Y, Urata Y, Yokoyama Y, Uchida K, Yamasaki T, Fujii Y, Okita K, Sakaida I (October 2006). "Improved liver function in patients with liver cirrhosis after autologous bone marrow cell infusion therapy". Stem Cells. 24 (10): 2292–98. doi:10.1634/stemcells.2005-0542. PMID 16778155. S2CID 5649484.

- ^ Subrammaniyan R, Amalorpavanathan J, Shankar R, Rajkumar M, Baskar S, Manjunath SR, Senthilkumar R, Murugan P, Srinivasan VR, Abraham S (September 2011). "Application of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells in six patients with advanced chronic critical limb ischemia as a result of diabetes: our experience". Cytotherapy. 13 (8): 993–9. doi:10.3109/14653249.2011.579961. PMID 21671823. S2CID 27251276.

- ^ Madhusankar N (2007). "Use of Bone Marrow derived Stem Cells in Patients with Cardiovascular Disorders". Journal of Stem Cells and Regenerative Medicine. 3 (1): 28–29. PMC 3908115. PMID 24693021.

- ^ Dedeepiya VD, Rao YY, Jayakrishnan GA, Parthiban JK, Baskar S, Manjunath SR, Senthilkumar R, Abraham SJ (2012). "Index of CD34+ Cells and Mononuclear Cells in the Bone Marrow of Spinal Cord Injury Patients of Different Age Groups: A Comparative Analysis". Bone Marrow Research. 2012: 1–8. doi:10.1155/2012/787414. PMC 3398573. PMID 22830032.

- ^ Gardner RL (March 2002). "Stem cells: potency, plasticity and public perception". Journal of Anatomy. 200 (Pt 3): 277–282. doi:10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00029.x. PMC 1570679. PMID 12033732.

- ^ Behrens A, van Deursen JM, Rudolph KL, Schumacher B (March 2014). "Impact of genomic damage and ageing on stem cell function". Nature Cell Biology. 16 (3): 201–7. doi:10.1038/ncb2928. PMC 4214082. PMID 24576896.

- ^ Barrilleaux B, Phinney DG, Prockop DJ, O'Connor KC (November 2006). "Review: ex vivo engineering of living tissues with adult stem cells". Tissue Engineering. 12 (11): 3007–19. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.328.2873. doi:10.1089/ten.2006.12.3007. PMID 17518617.

- ^ Gimble JM, Katz AJ, Bunnell BA (May 2007). "Adipose-derived stem cells for regenerative medicine". Circulation Research. 100 (9): 1249–60. doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000265074.83288.09. PMC 5679280. PMID 17495232.

- ^ Kuroda Y, Kitada M, Wakao S, Nishikawa K, Tanimura Y, Makinoshima H, Goda M, Akashi H, Inutsuka A, Niwa A, Shigemoto T, Nabeshima Y, Nakahata T, Nabeshima Y, Fujiyoshi Y, Dezawa M (May 2010). "Unique multipotent cells in adult human mesenchymal cell populations". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (19): 8639–43. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.8639K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0911647107. PMC 2889306. PMID 20421459.

- ^ "Bone Marrow Transplant". ucsfchildrenshospital.org.

- ^ Kane, Ed (2008-05-01). "Stem-cell therapy shows promise for horse soft-tissue injury, disease". DVM Newsmagazine. Archived from the original on 2008-12-11. Retrieved 2008-06-12.

- ^ "Stem Cell FAQ". US Department of Health and Human Services. 2004-07-14. Archived from the original on 2009-01-09.

- ^ Oliveira PH, da Silva CL, Cabral JM (2014). "Genomic Instability in Human Stem Cells: Current Status and Future Challenges". Stem Cells. 32 (11): 2824–32. doi:10.1002/stem.1796. PMID 25078438. S2CID 41335566.

- ^ a b Zhang L, Mack R, Breslin P, Zhang J (November 2020). "Molecular and cellular mechanisms of aging in hematopoietic stem cells and their niches". J Hematol Oncol. 13 (1) 157. doi:10.1186/s13045-020-00994-z. PMC 7686726. PMID 33228751.

- ^ Montazersaheb S, Ehsani A, Fathi E, Farahzadi R (2022). "Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms Involved in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Aging as a Clinical Prospect". Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022 2713483. doi:10.1155/2022/2713483. PMC 8993567. PMID 35401928.

- ^ De Coppi P, Bartsch G, Siddiqui MM, Xu T, Santos CC, Perin L, Mostoslavsky G, Serre AC, Snyder EY, Yoo JJ, Furth ME, Soker S, Atala A (January 2007). "Isolation of amniotic stem cell lines with potential for therapy". Nature Biotechnology. 25 (1): 100–6. doi:10.1038/nbt1274. PMID 17206138. S2CID 6676167.

- ^ "Vatican newspaper calls new stem cell source 'future of medicine'". Catholic News Agency. 3 February 2010.

- ^ "European Biotech Company Biocell Center Opens First U.S. Facility for Preservation of Amniotic Stem Cells in Medford, Massachusetts". Reuters. 2009-10-22. Archived from the original on 2009-10-30. Retrieved 2010-03-14.

- ^ "Europe's Biocell Center opens Medford office – Daily Business Update". The Boston Globe. 2009-10-22. Retrieved 2010-03-14.

- ^ "The Ticker". Boston Herald. BostonHerald.com. 2009-10-22. Retrieved 2010-03-14.

- ^ "Biocell Center opens amniotic stem cell bank in Medford". Mass High Tech Business News. 2009-10-23. Archived from the original on 2012-10-14. Retrieved 2012-08-26.

- ^ "World's First Amniotic Stem Cell Bank Opens In Medford". wbur.org. 22 October 2009. Retrieved 2010-03-14.

- ^ "Biocell Center Corporation Partners with New England's Largest Community-Based Hospital Network to Offer a Unique..." (Press release). Medford, Mass.: Prnewswire.com. Retrieved 2010-03-14.

- ^ a b c "Making human embryonic stem cells". The Economist. 2007-11-22.

- ^ Brand M, Palca J, Cohen A (2007-11-20). "Skin Cells Can Become Embryonic Stem Cells". National Public Radio.

- ^ "Breakthrough Set to Radically Change Stem Cell Debate". News Hour with Jim Lehrer. 2007-11-20. Archived from the original on 2014-01-22. Retrieved 2017-09-15.

- ^ a b c d e Kimbrel EA, Lanza R (December 2016). "Pluripotent stem cells: the last 10 years". Regenerative Medicine. 11 (8): 831–847. doi:10.2217/rme-2016-0117. PMID 27908220.

- ^ a b c Takahashi K, Yamanaka S (August 2006). "Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors". Cell. 126 (4): 663–676. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. hdl:2433/159777. PMID 16904174. S2CID 1565219.

- ^ Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, Yamanaka S (November 2007). "Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors". Cell. 131 (5): 861–872. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. hdl:2433/49782. PMID 18035408. S2CID 8531539.

- ^ Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane JL, Tian S, Nie J, Jonsdottir GA, Ruotti V, Stewart R, Slukvin II, Thomson JA (December 2007). "Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells". Science. 318 (5858): 1917–20. Bibcode:2007Sci...318.1917Y. doi:10.1126/science.1151526. PMID 18029452. S2CID 86129154.

- ^ "His inspiration comes from the research by Prof Shinya Yamanaka at Kyoto University, which suggests a way to create human embryo stem cells without the need for human eggs, which are in extremely short supply, and without the need to create and destroy human cloned embryos, which is bitterly opposed by the pro life movement." Highfield R (2007-11-16). "Dolly creator Prof Ian Wilmut shuns cloning". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 2009-07-30.

- ^ Maldonado M, Luu RJ, Ico G, Ospina A, Myung D, Shih HP, Nam J (September 2017). "Lineage- and developmental stage-specific mechanomodulation of induced pluripotent stem cell differentiation". Stem Cell Research & Therapy. 8 (1) 216. doi:10.1186/s13287-017-0667-2. PMC 5622562. PMID 28962663.

- ^ a b Robinton, DA; Daley, GQ (January 2012). "The promise of induced pluripotent stem cells in research and therapy". Nature. 481 (7381): 295–305. Bibcode:2012Natur.481..295R. doi:10.1038/nature10761. PMC 3652331. PMID 22258608.

- ^ Staerk J, Dawlaty MM, Gao Q, Maetzel D, Hanna J, Sommer CA, Mostoslavsky G, Jaenisch R (July 2010). "Reprogramming of human peripheral blood cells to induced pluripotent stem cells". Cell Stem Cell. 7 (1): 20–24. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2010.06.002. PMC 2917234. PMID 20621045.

- Lay summary in: "Frozen blood a source of stem cells, study finds". NewsDaily. Reuters. 2010-07-01. Archived from the original on 2010-07-03.

- ^ Chen X, Hartman A, Guo S (2015-09-01). "Choosing Cell Fate Through a Dynamic Cell Cycle". Current Stem Cell Reports. 1 (3): 129–138. doi:10.1007/s40778-015-0018-0. PMC 5487535. PMID 28725536.

- ^ Hindley C, Philpott A (April 2013). "The cell cycle and pluripotency". The Biochemical Journal. 451 (2): 135–143. doi:10.1042/BJ20121627. PMC 3631102. PMID 23535166.

- ^ Fox, D.T.; Morris, L.X.; Nystul, T.; Spradling, A.C. (2008). "Lineage analysis of stem cells". StemBook. doi:10.3824/stembook.1.33.1. PMID 20614627.

- ^ Beckmann, Julia; Scheitza, Sebastian; Wernet, Peter; Fischer, Johannes C.; Giebel, Bernd (15 June 2007). "Asymmetric cell division within the human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell compartment: identification of asymmetrically segregating proteins". Blood. 109 (12): 5494–5501. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-11-055921. PMID 17332245.

- ^ Xie, Ting; Spradling, Allan C (July 1998). "decapentaplegic Is Essential for the Maintenance and Division of Germline Stem Cells in the Drosophila Ovary". Cell. 94 (2): 251–260. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81424-5. PMID 9695953. S2CID 11347213.

- ^ Song, X.; Zhu, CH; Doan, C; Xie, T (7 June 2002). "Germline Stem Cells Anchored by Adherens Junctions in the Drosophila Ovary Niches". Science. 296 (5574): 1855–7. Bibcode:2002Sci...296.1855S. doi:10.1126/science.1069871. PMID 12052957. S2CID 25830121.

- ^ "Executive Order: Removing barriers to responsible scientific research involving human stem cells". whitehouse.gov. 9 March 2009 – via National Archives.

- ^ "National Institutes of Health Guidelines on Human Stem Cell Research". Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ "NIH Human Embryonic Stem Cell Registry". Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- ^ "NIH Human Embryonic Stem Cell Registry". Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- ^ a b Murnaghan, Ian. "Why Perform a Stem Cell Transplant? – Explore Stem Cells". www.explorestemcells.co.uk. Retrieved 2024-12-28.

- ^ a b "Stem Cell and Bone Marrow Transplants for Cancer - NCI". www.cancer.gov. 2015-04-29. Retrieved 2024-12-28.

- ^ Stamm C, Westphal B, Kleine HD, Petzsch M, Kittner C, Klinge H, et al. (January 2003). "Autologous bone-marrow stem-cell transplantation for myocardial regeneration". Lancet. 361 (9351): 45–46. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12110-1. PMID 12517467. S2CID 23858666.

- ^ Karanes C, Nelson GO, Chitphakdithai P, Agura E, Ballen KK, Bolan CD, Porter DL, Uberti JP, King RJ, Confer DL (2008). "Twenty years of unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplantation for adult recipients facilitated by the National Marrow Donor Program". Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 14 (9 Suppl): 8–15. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.06.006. PMID 18721775.

- ^ Lyon, Louisa (2018-10-01). "Stem cell therapies in neurology: the good, the bad and the unknown". Brain. 141 (10): e77. doi:10.1093/brain/awy221. ISSN 0006-8950. PMID 30202947.

- ^ "Tế bào gốc là gì". Mirai Care (in Vietnamese). Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ Master Z, McLeod M, Mendez I (March 2007). "Benefits, risks and ethical considerations in translation of stem cell research to clinical applications in Parkinson's disease". Journal of Medical Ethics. 33 (3): 169–173. doi:10.1136/jme.2005.013169. JSTOR 27719821. PMC 2598267. PMID 17329391.

- ^ "Comprehensive Stem Cell Training Course". R3 Medical Training. Retrieved 2021-05-15.

- ^ Moore KL, Persaud TV, Torchia MG (2000-03-04). "Before We Are Born: Essentials of Embryology and Birth Defects, 5th edition". Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health. 45 (2). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, Elsevier: 192. doi:10.1016/s1526-9523(99)00026-4. ISSN 1526-9523.

- ^ Healy, Bernadine. "Why Embryonic Stem Cells are obsolete". US News and world report. Retrieved Aug 17, 2015.

- ^ Ballantyne, Coco. "Fetal stem cells cause tumor in a teenage boy". Scientific American.

- ^ Lo, Bernard; Parham, Lindsay (May 2009). "Ethical Issues in Stem Cell Research". Endocrine Reviews. 30 (3). NIH: 204–213. doi:10.1210/er.2008-0031. PMC 2726839. PMID 19366754.

- ^ Bauer, G; Elsallab, M; Abou-El-Enein, M (September 2018). "Concise Review: A Comprehensive Analysis of Reported Adverse Events in Patients Receiving Unproven Stem Cell-Based Interventions". Stem Cells Translational Medicine. 7 (9): 676–685. doi:10.1002/sctm.17-0282. PMC 6127222. PMID 30063299.

- ^ Blackwell, Tom (2016-07-13). "Study reveals explosion of unproven stem-cell treatment in U.S. — and many Canadians are seeking them out". National Post. Retrieved 2022-03-22.

- ^ a b Berkowitz, Aaron L.; Miller, Michael B.; Mir, Saad A.; Cagney, Daniel; Chavakula, Vamsidhar; Guleria, Indira; Aizer, Ayal; Ligon, Keith L.; Chi, John H. (14 July 2016). "Glioproliferative Lesion of the Spinal Cord as a Complication of 'Stem-Cell Tourism'". New England Journal of Medicine. 375 (2): 196–8. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1600188. PMID 27331440.

- ^ Bowman, Michelle; Racke, Michael; Kissel, John; Imitola, Jaime (1 November 2015). "Responsibilities of Health Care Professionals in Counseling and Educating Patients With Incurable Neurological Diseases Regarding 'Stem Cell Tourism': Caveat Emptor". JAMA Neurology. 72 (11): 1342–5. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.1891. PMID 26322563.

- ^ "Communicating About Unproven Stem Cell Treatments to the Public".

- ^ Tsou, Amy (February 2015). "Ethical Considerations When Counseling Patients About Stem Cell Tourism". Continuum: Lifelong Learning in Neurology. 21 (1 Spinal Cord Disorders): 201–5. doi:10.1212/01.CON.0000461094.76563.be. PMID 25651226.

- ^ Du, Li; Rachul, Christen; Guo, Zhaochen; Caulfield, Timothy (9 March 2016). "Gordie Howe's 'Miraculous Treatment': Case Study of Twitter Users' Reactions to a Sport Celebrity's Stem Cell Treatment". JMIR Public Health and Surveillance. 2 (1): e8. doi:10.2196/publichealth.5264. PMC 4869214. PMID 27227162.

- ^ a b "How a University's Patents May Limit Stem-Cell Research". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2024-12-28.

- ^ "Public Patent Foundation - GuideStar Profile". www.guidestar.org. Retrieved 2024-12-28.

- ^ Jenei, Stephen (April 3, 2007). "WARF Stem Cell Patents Knocked Down in Round One". Patent Baristas. Retrieved 2024-12-28.

- ^ Jenei, Stephen (March 3, 2008). "Ding! WARF Wins Round 2 As Stem Cell Patent Upheld". Patent Baristas. Retrieved 2024-12-28.

- ^ Holden, Constance (March 12, 2008). "WARF Goes 3 for 3 on Patents". Science Now. Retrieved 2024-12-28.

- ^ McKeown, Scott (2010-05-10). "BPAI Rejects WARF Stem Cell Patent Claims in Inter Partes Reexamination Appeal". Patents Post-Grant. Retrieved 2024-12-28.

- ^ "The Foundation For Taxpayer & Consumer Rights, Requester And Appellant V. Patent Of Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation, Appeal 2012-011693, Reexamination Control 95/000,154 Patent 7,029,913". e-foia.uspto.gov. Archived from the original on 2013-02-20. Retrieved 2024-12-28.

- ^ "Consumer Watchdog, PPF Seek Invalidation of WARF's Stem Cell Patent". GenomeWeb. 2013-07-03. Retrieved 2024-12-28.

- ^ Antoinette Konski for Personalized Medicine Bulletin. February 3, 2014 U.S. Government and USPTO Urges Federal Circuit to Dismiss Stem Cell Appeal

- ^ a b c d e "Stemcells Redirection". stemcells.nih.gov. 2009. Archived from the original on 2018-06-19. Retrieved 2024-12-28.

- ^ "Treating Hair Loss with Stem Cell & PRP Therapy". Stem Cells LA. 2019-02-20. Retrieved 2020-05-30.

- ^ Gentile, Pietro; Garcovich, Simone; Bielli, Alessandra; Scioli, Maria Giovanna; Orlandi, Augusto; Cervelli, Valerio (November 2015). "The Effect of Platelet-Rich Plasma in Hair Regrowth: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial". Stem Cells Translational Medicine. 4 (11): 1317–23. doi:10.5966/sctm.2015-0107. ISSN 2157-6564. PMC 4622412. PMID 26400925.

- ^ Hynds, R (2022). "Exploiting the potential of lung stem cells to develop pro-regenerative therapies". Biology Open. 11 (10) bio059423. doi:10.1242/bio.059423. PMC 9581519. PMID 36239242.

- ^ a b Steinberg, Douglas (26 November 2000). "Stem Cells Tapped to Replenish Organs". The Scientist Magazine.

- ^ "Israeli scientists reverse brain birth defects using stem cells". ISRAEL21c. 2008-12-25. Retrieved 2024-12-28.

- ^ Kang KS, Kim SW, Oh YH, Yu JW, Kim KY, Park HK, Song CH, Han H (2005). "A 37-year-old spinal cord-injured female patient, transplanted of multipotent stem cells from human UC blood, with improved sensory perception and mobility, both functionally and morphologically: a case study". Cytotherapy. 7 (4): 368–373. doi:10.1080/14653240500238160. PMID 16162459. S2CID 33471639.

- ^ Strauer BE, Schannwell CM, Brehm M (April 2009). "Therapeutic potentials of stem cells in cardiac diseases". Minerva Cardioangiologica. 57 (2): 249–267. PMID 19274033.

- ^ DeNoon, Daniel J. (4 November 2004). "Hair Cloning Nears Reality as Baldness Cure". WebMD.

- ^ Yen AH, Sharpe PT (January 2008). "Stem cells and tooth tissue engineering". Cell and Tissue Research. 331 (1): 359–372. doi:10.1007/s00441-007-0467-6. PMID 17938970. S2CID 23765276.

- ^ "Gene therapy is first deafness 'cure'". New Scientist. February 14, 2005.

- ^ "Stem cells used to restore vision". BBC News. 2005-04-28.

- ^ Hanson C, Hardarson T, Ellerström C, Nordberg M, Caisander G, Rao M, Hyllner J, Stenevi U (March 2013). "Transplantation of human embryonic stem cells onto a partially wounded human cornea in vitro". Acta Ophthalmologica. 91 (2): 127–130. doi:10.1111/j.1755-3768.2011.02358.x. PMC 3660785. PMID 22280565.

- ^ Vastag B (April 2001). "Stem cells step closer to the clinic: paralysis partially reversed in rats with ALS-like disease". JAMA. 285 (13): 1691–93. doi:10.1001/jama.285.13.1691. PMID 11277806.

- ^ Anderson, Querida (15 June 2008). "Osiris Trumpets Its Adult Stem Cell Product". Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology News. 28 (12).

- ^ Gurtner, Geoffrey C.; Callaghan, Matthew J.; Longaker, Michael T. (February 2007). "Progress and Potential for Regenerative Medicine". Annual Review of Medicine. 58 (1): 299–312. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.58.082405.095329. PMID 17076602.

- ^ Hanna V, Gassei K, Orwig KE (2015). "Stem Cell Therapies for Male Infertility: Where Are We Now and Where Are We Going?". In Carrell D, Schlegel P, Racowsky C, Gianaroli L (eds.). Biennial Review of Infertility. Springer. pp. 17–39. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-17849-3_3. ISBN 978-3-319-17849-3. Bone marrow transplantation is, as of 2009, the only established use of stem cells.

- ^ Valli H, Phillips BT, Shetty G, Byrne JA, Clark AT, Meistrich ML, Orwig KE (January 2014). "Germline stem cells: toward the regeneration of spermatogenesis". Fertility and Sterility. 101 (1): 3–13. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.10.052. PMC 3880407. PMID 24314923.

- ^ White YA, Woods DC, Takai Y, Ishihara O, Seki H, Tilly JL (February 2012). "Oocyte formation by mitotically active germ cells purified from ovaries of reproductive-age women". Nature Medicine. 18 (3): 413–421. doi:10.1038/nm.2669. PMC 3296965. PMID 22366948.

- ^ Herraiz, Sonia; Buigues, Anna; Díaz-García, César; Romeu, Mónica; Martínez, Susana; Gómez-Seguí, Inés; Simón, Carlos; Hsueh, Aaron J.; Pellicer, Antonio (May 2018). "Fertility rescue and ovarian follicle growth promotion by bone marrow stem cell infusion". Fertility and Sterility. 109 (5): 908–918.e2. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.01.004. ISSN 0015-0282. PMID 29576341.

- ^ Badawy, Ahmed; Sobh, Mohamed A.; Ahdy, Mohamed; Abdelhafez, Mohamed Sayed (2017-06-15). "Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell repair of cyclophosphamide-induced ovarian insufficiency in a mouse model". International Journal of Women's Health. 9: 441–7. doi:10.2147/IJWH.S134074. PMC 5479293. PMID 28670143.

- ^ Liew, Aaron; O'Brien, Timothy (2012-07-30). "Therapeutic potential for mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in critical limb ischemia". Stem Cell Research & Therapy. 3 (4): 28. doi:10.1186/scrt119. ISSN 1757-6512. PMC 3580466. PMID 22846185.

- ^ Bubela T, Li MD, Hafez M, Bieber M, Atkins H (November 2012). "Is belief larger than fact: expectations, optimism and reality for translational stem cell research". BMC Medicine. 10 133. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-10-133. PMC 3520764. PMID 23131007.

- ^ Ader M, Tanaka EM (December 2014). "Modeling human development in 3D culture". Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 31: 23–28. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2014.06.013. PMID 25033469.

- ^ McClure, Paul (2024-12-27). "Stem cells 'instructed' to form specific tissues and organs". New Atlas. Retrieved 2024-12-28.

- ^ Greenhough, Sebastian; Hay, David C. (April 2012). "Stem Cell-Based Toxicity Screening: Recent Advances in Hepatocyte Generation". Pharmaceutical Medicine. 26 (2): 85–89. doi:10.1007/BF03256896. S2CID 15893493.

- ^ García-Prat, Laura; Kaufmann, Kerstin B.; Schneiter, Florin; Voisin, Veronique; Murison, Alex; Chen, Jocelyn; Chan-Seng-Yue, Michelle; Gan, Olga I.; McLeod, Jessica L.; Smith, Sabrina A.; Shoong, Michelle C.; Parris, Darrien; Pan, Kristele; Zeng, Andy G.X.; Krivdova, Gabriela; Gupta, Kinam; Takayanagi, Shin-Ichiro; Wagenblast, Elvin; Wang, Weijia; Lupien, Mathieu; Schroeder, Timm; Xie, Stephanie Z.; Dick, John E. (August 2021). "TFEB-mediated endolysosomal activity controls human hematopoietic stem cell fate". Cell Stem Cell. 28 (10): 1838–50.e10. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2021.07.003. hdl:20.500.11850/510219. PMID 34343492. S2CID 236915618.

Further reading

[edit]- Manzo, Carlo; Torreno-Pina, Juan A.; Massignan, Pietro; Lapeyre, Gerald J.; Lewenstein, Maciej; Garcia Parajo, Maria F. (25 February 2015). "Weak Ergodicity Breaking of Receptor Motion in Living Cells Stemming from Random Diffusivity". Physical Review X. 5 (1) 011021. arXiv:1407.2552. Bibcode:2015PhRvX...5a1021M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevX.5.011021. S2CID 73582473.

External links

[edit]- "National Institutes of Health: Stem Cell Information". stemcells.nih.gov. Retrieved 2024-12-28.

- "Stem cells — Latest research and news". Nature. Retrieved 2024-12-28.

Stem cell

View on GrokipediaFundamental Properties

Self-Renewal and Proliferation