Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

TRAPPIST-1e

View on Wikipedia

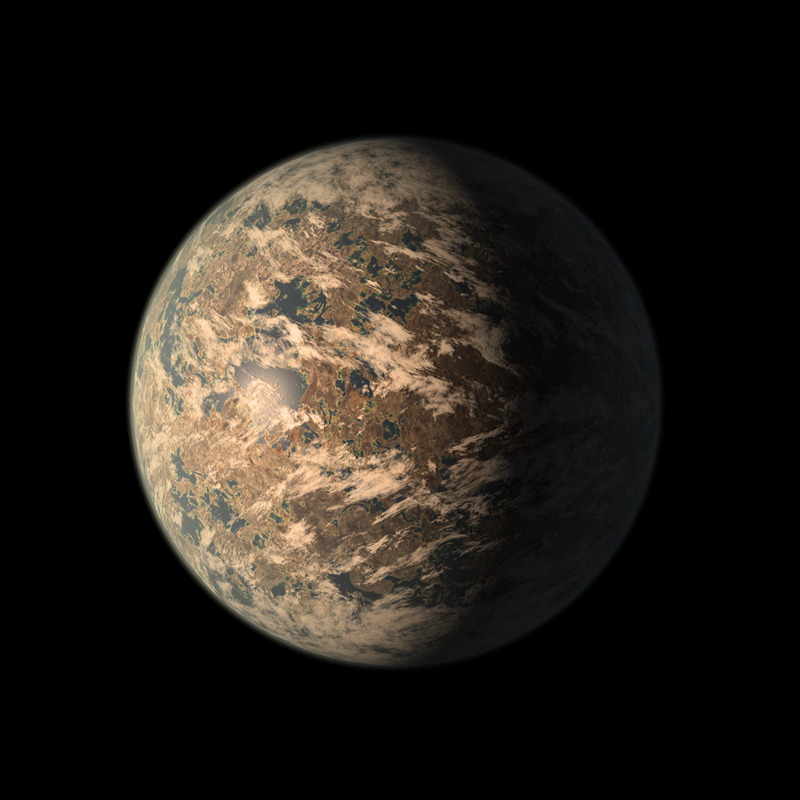

Artist's impression of TRAPPIST-1e from 2018, depicted here as a tidally locked planet with a liquid ocean. The actual appearance of the exoplanet is currently unknown, but based on its density, it is likely not entirely covered in water. | |

| Discovery[1] | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Michaël Gillon et al. |

| Discovery site | Spitzer Space Telescope |

| Discovery date | 22 February 2017 |

| Transit | |

| Orbital characteristics[2] | |

| 0.02925±0.00025 AU | |

| Eccentricity | 0.00510±0.00058[3] |

| 6.101013±0.000035 d | |

| Inclination | 89.793°±0.048° |

| 108.37°±8.47°[3] | |

| Star | TRAPPIST-1[4] |

| Physical characteristics[2] | |

| 0.920+0.013 −0.012 R🜨 | |

| Mass | 0.692±0.022 M🜨 |

Mean density | 4.885+0.168 −0.182 g/cm3 |

| 0.817±0.024 g 8.01±0.24 m/s2 | |

| Temperature | Teq: 249.7±2.4 K (−23.5 °C; −10.2 °F)[5] |

| Atmosphere | |

| Composition by volume | None or mostly N2, with trace amounts of CH4 and CO2[6] |

TRAPPIST-1e is a rocky, close-to-Earth-sized exoplanet orbiting within the habitable zone around the ultracool dwarf star TRAPPIST-1, located 40.7 light-years (12.5 parsecs; 385 trillion kilometers; 239 trillion miles) away from Earth in the constellation of Aquarius. Astronomers used the transit method to find the exoplanet, a method that measures the dimming of a star when a planet crosses in front of it.

The exoplanet was one of seven discovered orbiting the star using observations from the Spitzer Space Telescope.[1][7] Three of the seven (e, f, and g) are in the habitable zone/"goldilocks" zone.[8][9] TRAPPIST-1e is similar to Earth's mass, radius, density, gravity, temperature, and stellar flux.[3][10] It is also confirmed that TRAPPIST-1e lacks a cloud-free hydrogen-dominated atmosphere, meaning that if the planet has an atmosphere it is more likely to have a compact atmosphere like the terrestrial planets in the Solar System.[11]

In November 2018, researchers determined that of the seven exoplanets in the multi-planetary system, TRAPPIST-1e has the best chance of being an Earth-like ocean planet, and the one most worthy of further study regarding habitability.[12] According to the Habitable Exoplanets Catalog, TRAPPIST-1e is among the best potentially habitable exoplanets discovered.[13] The most recent observation in 2025 was unable to conclude with confidence if there was an atmosphere or not, though it could rule out certain atmosphere scenarios.

Physical characteristics

[edit]Mass, radius, density, composition and temperature

[edit]TRAPPIST-1e was detected with the transit method, where the planet blocked a small percentage of its host star's light when passing between it and Earth. This allowed scientists to accurately determine the planet's radius at 0.920 R🜨, with a small uncertainty of about 83 km (52 mi). Transit-timing variations and advanced computer simulations helped constrain the planet's mass, which turned out to be 0.692 M🜨, or about 15% less massive than Venus.[2] TRAPPIST-1e has 82% the surface gravity of Earth, the third-lowest in the system. Its radius and mass are also the third-least among the TRAPPIST-1 planets.[2]

With both the radius and mass of TRAPPIST-1e determined with low error margins, scientists could accurately calculate the planet's density, surface gravity, and composition. Initial density estimates in 2018 suggested it has a density of 5.65 g/cm3, about 1.024 times Earth's density of 5.51 g/cm3. TRAPPIST-1e appeared to be unusual in its system, as it was the only planet with a density consistent with a pure rock-iron composition, and the only one with a higher density than Earth (TRAPPIST-1c also appeared to be entirely rock, but with a lower density than TRAPPIST-1e). The higher density of TRAPPIST-1e implies an Earth-like composition and a solid rocky surface. This also appeared to be unusual among the TRAPPIST-1 planets, as most were thought to have densities consistent with being completely covered in either a thick steam/hot CO2 atmosphere, a global liquid ocean, or an ice shell.[3] However, refined estimates show that all planets in the system have similar densities, consistent with rocky compositions, with TRAPPIST-1e having a somewhat lower but still Earth-like bulk density.[2]

The planet has a calculated equilibrium temperature of 246.1 K (−27.1 °C; −16.7 °F) given an albedo of 0, also known as its "blackbody" temperature.[10] For a more realistic Earth-like albedo however, this provides an unrealistic picture of the surface temperature of the planet. Earth's equilibrium temperature is 255 K;[14][better source needed] it is Earth's greenhouse gases that raise its surface temperatures to the levels we experience. If TRAPPIST-1e has a thick atmosphere, its surface could be much warmer than its equilibrium temperature.

Host star

[edit]The planet orbits an (late M-type) ultracool dwarf star named TRAPPIST-1. The star has a mass of 0.089 M☉ – near the boundary between a brown dwarf and low-mass star – and a radius of 0.121 R☉. It has a temperature of 2,516 K (2,243 °C; 4,069 °F) and is 7.6 billion years old. In comparison, the Sun is 4.6 billion years old[15] and has a temperature of 5,778 K (5,505 °C; 9,941 °F).[16] The star is metal-rich, with a metallicity ([Fe/H]) of 0.04, or 109% the solar amount. This is particularly odd as such low-mass stars near the boundary between brown dwarfs and hydrogen-fusing stars should be expected to have considerably less metal content than the Sun. Its luminosity (L☉) is 0.0522% of that of the Sun.

The star's apparent magnitude, or how bright it appears from Earth's perspective, is 18.8. Therefore, it is far too dim to be seen with the naked eye.

Orbit

[edit]TRAPPIST-1e orbits its host star quite closely. One full revolution around TRAPPIST-1 takes only 6.099 Earth days (~146 hours) to complete. It orbits at a distance of 0.02928285 AU (4.4 million km; 2.7 million mi), or just under 3% the separation between Earth and the Sun. For comparison, the closest planet in the Solar System, Mercury, takes 88 days to orbit the Sun at a distance of 0.38 AU (57 million km; 35 million mi). Despite its close proximity to its host star, TRAPPIST-1e gets only about 60% the starlight that Earth gets from the Sun due to the low luminosity of its star. The star would cover an angular diameter of about 2.17 degrees from the surface of the planet, and so would appear about four times larger than the Sun does from Earth.

Atmosphere

[edit]Transit observations with James Webb Space Telescope suggested no clear answer about the existence of an atmosphere, but it did rule out many atmosphere scenarios. See the "Habitability" studies below.

Habitability

[edit]

The exoplanet was announced to be orbiting within the habitable zone of its parent star, the region where, with the correct conditions and atmospheric properties, liquid water may exist on the surface of the planet. TRAPPIST-1e has a radius of around 0.91 R🜨, so it is likely a rocky planet. Its host star is a red ultracool dwarf, with only about 8% of the mass of the Sun (close to the boundary between brown dwarfs and hydrogen-fusing stars). As a result, stars like TRAPPIST-1 have the potential to remain stable for up to 12 trillion years, which is over 2,000 times longer than the Sun.[17] Because of this ability to live for such a long period of time, it is likely TRAPPIST-1 will be one of the last remaining stars in the Universe, when the gas needed to form new stars will be exhausted, and the existing stars begin to die off.

2018 studies

[edit]Despite being likely tidally locked – meaning one hemisphere permanently faces the star while the other does not – which may reduce the habitability of the planet, more detailed studies of TRAPPIST-1e and the other TRAPPIST-1 planets released in 2018 determined that the planet is in fact one of the most Earth-sized worlds found, with 91% the radius, 77% the mass, 102.4% the density (5.65 g/cm3), and 93% the surface gravity. TRAPPIST-1e is confirmed to be a terrestrial planet with a solid, rocky surface. It is cool enough for liquid water to pool on the surface, but not so cold that it would freeze like on TRAPPIST-1f, g, and h.[3]

The planet receives a stellar flux 60.4% that of Earth, about a third lower than that of Earth but significantly more than that of Mars.[10] Its equilibrium temperature ranges from 225 K (−48 °C; −55 °F)[18] to 246.1 K (−27.1 °C; −16.7 °F),[10] depending on how much light the planet reflects into space. Both of these are between those of Earth and Mars as well. In addition, its atmosphere is confirmed to not be dense or thick enough to harm the habitability potential as well, according to models by the University of Washington.[11] The atmosphere, if it is dense enough, may also help to transfer additional heat to the dark side of the planet.

2024 studies

[edit]According to a 2024 study, based on modeling, TRAPPIST-1e could be having its atmosphere stripped by its host star, possibly as a result of its short orbital period, which would make it inhospitable to life. The same phenomenon could impact the atmospheres of the other planets in this system.[19][20]

2025 studies

[edit]Based on four observations of TRAPPIST-1e using the James Webb Space Telescope's NIRSpec instrument, researchers were unable to find conclusive evidence for or against the presence of an atmosphere. The analysis showed two models the data could adequately explain. The first is a flat-line model, which could mean two things: TRAPPIST-1e is a bare rock; or it has an atmosphere of an unknown type completely hidden by a high, thick cloud deck. The second model is a range of nitrogen-rich atmospheres, with nitrogen as the dominant gas. Within the nitrogen scenarios, there is a "tentative preference" for trace amounts of methane (CH4) mixed in. The authors conclude that the primary limitation in studying TRAPPIST-1e is mitigating the effects of its active star. To overcome this, a new program of 15 additional JWST observations is underway. This program will observe back-to-back transits of TRAPPIST-1e and its neighboring planet, TRAPPIST-1b, which is believed to be a bare rock. By using the signal from the bare rock planet to correct for the star's activity, it may be possible to reveal whether TRAPPIST-1e has an atmosphere.[6][21]

Discovery

[edit]A team of astronomers headed by Michaël Gillon[22] used the TRAPPIST (Transiting Planets and Planetesimals Small Telescope) telescope at the La Silla Observatory in the Atacama Desert, Chile,[23] to observe TRAPPIST-1 and search for orbiting planets. By utilising transit photometry, they discovered three Earth-sized planets orbiting the dwarf star; the innermost two are tidally locked to their host star while the outermost appears to lie either within the system's habitable zone or just outside of it.[24][25] The team made their observations from September–December 2015 and published its findings in the May 2016 issue of the journal Nature.[23][7]

The original claim and presumed size of the planet was revised when the full seven-planet system was revealed in 2017:

- "We already knew that TRAPPIST-1, a small, faint star some 40 light years away, was special. In May 2016, a team led by Michaël Gillon at Belgium’s University of Liege announced it was closely orbited by three planets that are probably rocky: TRAPPIST-1b, c and d ...

- "As the team kept watching shadow after shadow cross the star, three planets no longer seemed like enough to explain the pattern. "At some point we could not make sense of all these transits," Gillon said.

- "Now, after using the space-based Spitzer telescope to stare at the system for almost three weeks straight, Gillon and his team have solved the problem: TRAPPIST-1 has four more planets.

- "The planets closest to the star, TRAPPIST-1b and c, are unchanged. But there's a new third planet, which has taken the d moniker, and what had looked like d before turned out to be glimpses of e, f, and g. There's a planet h, too, drifting farthest out, and only spotted once."[26]

Gallery

[edit]Videos

[edit]-

Video (01:32) – Artistic representation of TRAPPIST-1 exoplanets transiting their host star.

-

Video (01:10) – Fly-around animation of the planets of the TRAPPIST-1 system, including TRAPPIST-1e.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Gillon, Michaël; Triaud, Amaury H.M.J.; et al. (23 February 2017). "Seven temperate terrestrial planets around the nearby ultracool dwarf star TRAPPIST-1". Nature. 542 (7642): 456–460. arXiv:1703.01424. Bibcode:2017Natur.542..456G. doi:10.1038/nature21360. PMC 5330437. PMID 28230125.

- ^ a b c d e Agol, Eric; Dorn, Caroline; Grimm, Simon L.; Turbet, Martin; et al. (1 February 2021). "Refining the Transit-timing and Photometric Analysis of TRAPPIST-1: Masses, Radii, Densities, Dynamics, and Ephemerides". The Planetary Science Journal. 2 (1): 1. arXiv:2010.01074. Bibcode:2021PSJ.....2....1A. doi:10.3847/psj/abd022. S2CID 222125312.

- ^ a b c d e Grimm, Simon L.; Demory, Brice-Olivier; et al. (21 January 2018). "The nature of the TRAPPIST-1 exoplanets". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 613 (A68). 21. arXiv:1802.01377. Bibcode:2018A&A...613A..68G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201732233. S2CID 3441829. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- ^ van Grootel, Valerie; Fernandes, Catarina S.; et al. (5 December 2017). "Stellar parameters for TRAPPIST-1". The Astrophysical Journal. 853 (1): 30. arXiv:1712.01911. Bibcode:2018ApJ...853...30V. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/aaa023. S2CID 54034373.

- ^ Ducrot, E.; Gillon, M.; Delrez, L.; Agol, E.; et al. (1 August 2020). "TRAPPIST-1: Global results of the Spitzer Exploration Science Program Red Worlds". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 640: A112. arXiv:2006.13826. Bibcode:2020A&A...640A.112D. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201937392. ISSN 0004-6361. S2CID 220041987.

- ^ a b Glidden, Ana; Ranjan, Sukrit; Seager, Sara; Espinoza, Néstor; et al. (10 September 2025). "JWST-TST DREAMS: Secondary Atmosphere Constraints for the Habitable Zone Planet TRAPPIST-1 e". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 990 (2): L53. arXiv:2509.05407. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/adf62e.

- ^ a b Gillon, Michaël; Jehin, Emmanuël; et al. (2 May 2016). "Temperate Earth-sized planets transiting a nearby ultracool dwarf star". Nature. 533 (7602): 221–224. arXiv:1605.07211. Bibcode:2016Natur.533..221G. doi:10.1038/nature17448. PMC 5321506. PMID 27135924.

- ^ NASA (21 February 2017). "NASA telescope reveals largest batch of Earth-size, habitable-zone planets around single star". NASA.gov. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- ^ NASA; Jet Propulsion Laboratory (22 February 2017). "TRAPPIST-1 Planet Lineup". NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). NASA. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- ^ a b c d Delrez, Laetitia; Gillon, Michael; et al. (9 January 2018). "Early 2017 observations of TRAPPIST-1 with Spitzer". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 475 (3): 3577. arXiv:1801.02554. Bibcode:2018MNRAS.475.3577D. doi:10.1093/mnras/sty051. S2CID 54649681. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- ^ a b de Wit, Julien; Wakeford, Hannah R.; et al. (5 February 2018). "Atmospheric reconnaissance of the habitable-zone Earth-sized planets orbiting TRAPPIST-1". Nature Astronomy. 2 (3). Nature: 214–219. arXiv:1802.02250. Bibcode:2018NatAs...2..214D. doi:10.1038/s41550-017-0374-z. S2CID 119085332. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- ^ Kelley, Peter (21 November 2018). "Study brings new climate models of small star TRAPPIST 1's seven intriguing worlds". EurekAlert!. University of Washington. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ^ "The Habitable Exoplanets Catalog". Planetary Habitability Laboratory @ UPR Arecibo (phl.upr.edu). University of Puerto Rico at Arecibo. 6 December 2021. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ "Equilibrium Temperatures of Planets". burro.case.edu. n.d. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- ^ Williams, Matt (22 December 2015). "What is the Life Cycle Of The Sun?". Universe Today. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- ^ Cain, Fraser (8 October 2013). "What Color is the Sun?". Universe Today. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- ^ Adams, Fred C.; Laughlin, Gregory; Graves, Genevieve J.M. (December 2004). "Red Dwarfs and the End of the Main Sequence". Gravitational Collapse: From massive stars to planets. Vol. 22. Revista Mexicana de Astronomía y Astrofísica (Serie de Conferencias). pp. 46–49. Bibcode:2004RMxAC..22...46A.

- ^ Mendez, Abel (2021). "HEC: Exoplanets Calculator". Planetary Habitability Laboratory @ UPR Arecibo. University of Puerto Rico at Arecibo. Archived from the original on 18 October 2021. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- ^ Cohen, Ofer; Glocer, Alex; et al. (February 2024). "Heating of the Atmospheres of Short-orbit Exoplanets by Their Rapid Orbital Motion through an Extreme Space Environment". The Astrophysical Journal. 962 (2): 157. arXiv:2401.14459. Bibcode:2024ApJ...962..157C. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ad206a.

- ^ Robert Lea (28 February 2024). "Possibly habitable Trappist-1 exoplanet caught destroying its own atmosphere". Space.com. Retrieved 1 April 2024.

- ^ Andrews, Robin George (8 September 2025). "Hopeful Hint of an Earthlike Atmosphere on a Distant Planet". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 September 2025.

- ^ Michaël Gillon is part of the Institut d'Astrophysique et Géophysique at the University of Liège: "AGO - Department of Astrophysics, Geophysics and Oceanography". ago.ulg.ac.be. Belgium: University of Liège. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- ^ a b Sample, Ian (2 May 2016). "Could these newly-discovered planets orbiting an ultracool dwarf host life?". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- ^ Gillon, Michaël; de Wit, Julien; Hook, Richard (2 May 2016). "Three Potentially Habitable Worlds Found Around Nearby Ultracool Dwarf Star". ESO.org. European Southern Observatory. eso1615. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- ^ Bennett, Jay (2 May 2016). "Three Newly Discovered Planets Are the Best Bets for Life Outside the Solar System". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- ^ Sokol, Joshua (22 February 2017). "Exoplanet discovery: Seven Earth-size exoplanets may have water". Space. New Scientist. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

TRAPPIST-1e

View on GrokipediaDiscovery and nomenclature

Initial detection

TRAPPIST-1e was first detected as part of the TRAPPIST Ultra-cool Dwarf Transit Survey (TUDTS), a ground-based photometric program aimed at identifying Earth-sized exoplanets transiting nearby ultracool dwarfs within their habitable zones.[1] The survey utilized the 0.6-meter TRAPPIST (Transiting Planets and Planetesimals Small Telescope) robotic telescope installed at the La Silla Observatory in Chile, which monitored the ultracool dwarf star TRAPPIST-1—a late M8-type star located approximately 12 parsecs from Earth—for periodic brightness dips indicative of planetary transits.[1] Initial observations of TRAPPIST-1 began in late 2015, leading to the detection of three inner transiting planets (designated b, c, and d) announced in May 2016. To resolve ambiguities in the light curve and search for additional planets, follow-up observations were conducted using NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope, which provided continuous monitoring in the infrared to minimize atmospheric interference.[1] Starting in September 2016, Spitzer observed TRAPPIST-1 for nearly 500 hours over 20 days, revealing four additional shallow transit signals beyond the initial three planets.[7] Among these, the signal for TRAPPIST-1e was identified through detailed analysis of the transit timing variations and photometric data, confirming it as an Earth-sized planet orbiting in the habitable zone of the system.[1] The full seven-planet configuration, including TRAPPIST-1e as the innermost of the newly detected worlds, was announced by Michaël Gillon and collaborators on February 22, 2017, in a paper published in Nature.[1] This detection highlighted the potential of ultracool dwarfs as hosts for compact multi-planet systems amenable to transit surveys.[1]Confirmation and naming

The existence of TRAPPIST-1e, along with the other planets in the system, was confirmed through the extensive Spitzer observations conducted in late 2016, supplemented by ground-based photometry from the TRAPPIST telescope and the Very Large Telescope (VLT) at Paranal Observatory, which corroborated the initial signals and provided light curves to distinguish true planetary transits from stellar variability.[1] The planet was formally named TRAPPIST-1e in accordance with the International Astronomical Union's nomenclature for exoplanets, where letters 'b' through 'h' denote the planets in ascending order of orbital periods around the host star TRAPPIST-1, positioning 'e' as the fourth innermost world.[1] No informal or provisional names have been adopted for TRAPPIST-1e or its siblings. Early parameter estimates derived from these transit data indicated a radius of approximately 0.92 Earth radii (R⊕) for TRAPPIST-1e, establishing it as an Earth-sized planet, though no direct mass determination was possible at this stage due to the faint radial-velocity signal of the ultracool dwarf host star.[1] The comprehensive confirmation of the seven Earth-sized planets orbiting TRAPPIST-1, including TRAPPIST-1e, was detailed in a seminal paper by Gillon et al., published in Nature in 2017, marking a milestone in the study of compact multi-planet systems around low-mass stars.[1]The TRAPPIST-1 system

Host star characteristics

TRAPPIST-1 is an ultracool dwarf star of spectral class M8V, classified as a late-type M dwarf due to its low effective temperature and small size. Located in the constellation Aquarius at a distance of 40.5 light-years (12.4 parsecs) from Earth, it hosts a compact system of seven Earth-sized planets.[8][9] The star's fundamental parameters are as follows:| Parameter | Value | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Mass | 0.0898 ± 0.0023 M⊙ | Agol et al. (2021)[10] |

| Radius | 0.1192 ± 0.0013 R⊙ | Agol et al. (2021)[10] |

| Effective temperature | 2566 ± 26 K | Agol et al. (2021)[10] |

| Bolometric luminosity | (5.5 ± 0.3) × 10^{-4} L⊙ | Agol et al. (2021)[10] |

| Age | 7.6 ± 2.2 Gyr | Burgasser & Mamajek (2017)[11] |

System architecture and planets

The TRAPPIST-1 system comprises seven rocky, Earth-sized planets designated b through h, which orbit their ultracool dwarf host star in a tightly packed, near-resonant chain, enabling detailed characterization through transit observations. This compact architecture, with all planetary orbits confined within approximately 0.06 AU of the star, facilitates the detection of transit timing variations (TTV) that have been crucial for estimating planetary masses.[13] TRAPPIST-1e occupies the fourth position in this sequence, lying within the system's habitable zone and receiving about 0.65 times the average stellar insolation that Earth experiences from the Sun. The planets span a narrow range of sizes, with radii between roughly 0.76 and 1.13 Earth radii, and masses estimated via TTV analyses from approximately 0.33 to 1.37 Earth masses, positioning TRAPPIST-1e as one of the more Earth-like members in both dimensions.[14]Physical properties

Size, mass, and density

TRAPPIST-1e has a radius of 0.920 ± 0.012 Earth radii, determined from the depth of its transits across the host star as observed by the Spitzer Space Telescope and other facilities.[15] This measurement reflects the planet's size relative to Earth, placing it among the terrestrial worlds in the TRAPPIST-1 system. The planet's mass is 0.692 ± 0.022 Earth masses, derived from detailed analysis of transit-timing variations (TTVs) that capture gravitational interactions among the planets, refining earlier estimates from initial discoveries.[15] These TTVs, combined with N-body simulations, provide constraints on the orbital dynamics and bulk properties. From the mass and radius, the mean density is calculated as 4.885 ± 0.18 g/cm³, a value consistent with a predominantly rocky composition similar to Earth's.[15] The surface gravity on TRAPPIST-1e is approximately 0.817 g, or 8.01 m/s², computed using the formula , where is the planetary mass and is the radius.[15] This lower gravity compared to Earth's arises from the planet's reduced mass despite its near-Earth size.Composition and internal structure

TRAPPIST-1e is characterized as a rocky planet, with its bulk density of approximately 4.89 g/cm³ indicating a differentiated interior dominated by refractory materials.[16] This high density supports the presence of an iron-rich core comprising about 25–28% of the planet's total mass, overlaid by a silicate mantle that constitutes roughly 65–70% of the mass, and potentially a thin crust.[16][17] The core-mantle boundary is inferred from interior structure models that account for the planet's mass and radius constraints, suggesting a core radius of around 0.4–0.5 times the planet's radius under Earth-like compositional assumptions depleted in iron (approximately 21 wt% Fe).[16] The planet's density effectively rules out a substantial hydrogen-helium envelope, with models limiting any gaseous layer to less than 1% of the total mass, as thicker envelopes would reduce the bulk density below observed values.[16] Instead, the interior is consistent with a volatile-poor to moderately volatile-enriched rocky composition, without evidence for extended gas layers.[17] Interior structure models further indicate the potential for a water or ice layer, with volatile mass fractions estimated at 5–20% depending on formation scenarios and atmospheric escape histories.[18] These models, incorporating multi-phase water layers (including supercritical, liquid, and condensed ice phases), predict that such a hydrosphere could overlie the silicate mantle, though confirmation awaits direct observational constraints on the planet's full mass-radius profile.[18]Orbital dynamics

Key orbital parameters

TRAPPIST-1e orbits its ultracool dwarf host star at a close distance, completing one revolution in approximately 6.1 days, placing it within the system's habitable zone alongside planets f and g. This short orbital period results from the planet's proximity to the star, with key parameters derived from extensive transit timing variations (TTVs) and photometric observations using telescopes such as Spitzer and ground-based facilities. The orbit is nearly circular, as indicated by a low eccentricity value, and highly inclined relative to the line of sight, enabling frequent transits observable from Earth. The following table summarizes the primary orbital parameters for TRAPPIST-1e:| Parameter | Value | Unit | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Semi-major axis | 0.02925 ± 0.00016 | AU | Agol et al. (2021)[15] |

| Orbital period | 6.101013 ± 0.000035 | days | Agol et al. (2021)[15] |

| Eccentricity | 0.00510 ± 0.00038 | - | Agol et al. (2021)[15] |

| Inclination | 89.75° ± 0.05° | degrees | Ducrot et al. (2020)[19] |