Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

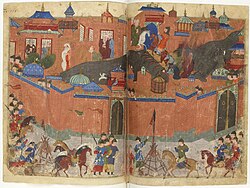

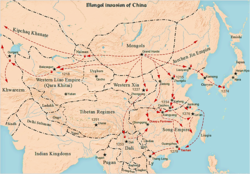

Mongol invasions and conquests

View on Wikipedia| Mongol invasions and conquests | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The Mongol Empire at its greatest extent (1206–1294) | |||||

| |||||

The Mongol invasions and conquests took place during the 13th and 14th centuries, creating the largest contiguous empire in history, the Mongol Empire (1206–1368), which by 1260 covered a significant portion of Eurasia. Historians regard the Mongol devastation as one of the deadliest episodes in history.[1][2]

At its height, the Mongol Empire included modern-day Mongolia, China, North Korea, South Korea, Myanmar, Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Kashmir, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Siberia, Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Turkey, Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova, Romania, and most of European Russia.[3]

Overview

[edit]The Mongol Empire developed in the course of the 13th century through a series of victorious campaigns throughout Eurasia. At its height, it stretched from the Pacific to Central Europe. It was later known as the largest contiguous land empire of all time. In contrast with later "empires of the sea" such as the European colonial powers, the Mongol Empire was a land power, fueled by the grass-foraging Mongol cavalry and cattle.[a] Thus most Mongol conquest and plundering took place during the warmer seasons, when there was sufficient grazing for their herds.[4] The rise of the Mongols was preceded by 15 years of wet and warm weather conditions from 1211 to 1225 that allowed favourable conditions for the breeding of horses, which greatly assisted their expansion.[5]

As the Mongol Empire began to fragment from 1260, conflict between the Mongols and Eastern European polities continued for centuries. Mongols continued to rule China into the 14th century under the Yuan dynasty, while Mongol rule in Persia persisted into the 15th century under the Timurid Empire. In the Indian subcontinent, the later Mughal Empire survived into the 19th century.

Central Asia

[edit]

Genghis Khan forged the initial Mongol Empire in Central Asia, starting with the unification of the nomadic tribes of the Merkits, Tatars, Keraites, Turks, Naimans and Mongols. The Buddhist Uighurs of Qocho surrendered and joined the empire. He then continued expansion via conquest of the Qara Khitai[6] and of the Khwarazmian Empire.

Large areas of Islamic Central Asia and northeastern Persia were seriously depopulated,[7] as every city or town that resisted the Mongols was destroyed. Each soldier was given a quota of enemies to execute according to circumstances. For example, after the conquest of Urgench, each Mongol warrior – in an army of perhaps two tumens (20,000 troops) – was required to execute 24 people, or nearly half a million people per said army.[8]

Against the Alans and the Cumans (Kipchaks), the Mongols used divide-and-conquer tactics by first warning the Cumans to end their support of the Alans, whom they then defeated,[9] before rounding on the Cumans.[10] The Alans were recruited into the Mongol forces and known as the Asud, with one unit called "Right Alan Guard" that was combined with "recently surrendered" soldiers. Mongols and Chinese soldiers stationed in the area of the former state of Qocho and in Besh Balikh established a Chinese military colony led by Chinese general Qi Kongzhi.[11]

During the Mongol attack on the Middle East ruled by the Mamluk Sultanate, most of the Mamluk military was composed of Kipchaks and the Golden Horde's supply of Kipchak fighters replenished the Mamluk armies and helped them fight off the Mongols.[9]

Hungary became a refuge for fleeing Cumans.[12]

The decentralized, stateless Kipchaks only converted to Islam after the Mongol conquest, unlike the centralized Karakhanid entity comprising the Yaghma, Qarluqs, and Oghuz who converted earlier to world religions.[13]

The Mongol conquest of the Kipchaks led to a merged society with a Mongol ruling class over a Kipchak-speaking populace which came to be known as Tatar, and which eventually absorbed Armenians, Italians, Greeks, and Crimean Goths in Crimea, the origin of the current Crimean Tatars.[14]

West Asia

[edit]

The Mongols conquered, by battle or voluntary surrender, the areas of present-day Iran, Iraq, the Caucasus, and parts of Syria and Turkey, with further Mongol raids reaching southwards into Palestine as far as Gaza in 1260 and 1300. The major battles were the siege of Baghdad, when the Mongols sacked the city which had been the center of Islamic power for 500 years and the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260 in southeastern Galilee, when the Muslim Bahri Mamluks were able to defeat the Mongols and decisively halt their advance for the first time. One thousand North Chinese engineer squads accompanied the Mongol Hulagu Khan during his conquest of the Middle East.[b]

East Asia

[edit]

Genghis Khan and his descendants launched progressive invasions of China, subjugating the Western Xia in 1209 before destroying them in 1227, defeating the Jin dynasty in 1234 and defeating the Song dynasty in 1279. They made the Kingdom of Dali into a vassal state in 1253 after the Dali King Duan Xingzhi defected to the Mongols and helped them conquer the rest of Yunnan, forced Korea to capitulate through nine invasions, but failed in their attempts to invade Japan, their fleets scattered by kamikaze storms.

The Mongols' greatest triumph was when Kublai Khan established the Yuan dynasty in China in 1271. The dynasty created a "Han Army" (漢軍) out of defected Jin troops and an army of defected Song troops called the "Newly Submitted Army" (新附軍).[16]

The Mongol force which invaded southern China was far greater than the force they sent to invade the Middle East in 1256.[17]

The Yuan dynasty established the top-level government agency Bureau of Buddhist and Tibetan Affairs to govern Tibet, which was conquered by the Mongols and put under Yuan rule. The Mongols also invaded Sakhalin Island between 1264 and 1308. Likewise, Korea (Goryeo) became a semi-autonomous vassal state of the Yuan dynasty for about 80 years.

North Asia

[edit]By 1206, Genghis Khan had conquered all Mongol and Turkic tribes in Mongolia and southern Siberia. In 1207 his eldest son Jochi subjugated the Siberian forest people, the Uriankhai, the Oirats, Barga, Khakas, Buryats, Tuvans, Khori-Tumed, and Yenisei Kyrgyz according to chapter 5 of the Secret History of the Mongols. He then organized the Siberians into three tumens. He gave the Telengits and Tolos along the Irtysh to an old companion, Qorchi. While the Barga, Tumed, Buriats, Khori, Keshmiti, and Bashkirs were organized in separate thousands, the Telengit, Tolos, Oirats and Yenisei Kirghiz were numbered into the regular tumens[18] Genghis created a settlement of Chinese craftsmen and farmers at Kem-kemchik after the first phase of the Mongol conquest of the Jin dynasty. The Khagans favored gyrfalcons, furs, women, and Kyrgyz horses for tribute.

Western Siberia came under the Golden Horde.[19] The descendants of Orda Khan, the eldest son of Jochi, directly ruled the area. In the swamps of western Siberia, dog sled Yam stations were set up to facilitate collection of tribute.

In 1270, Kublai Khan sent a Chinese official, with a new batch of settlers, to serve as judge of the Kyrgyz and Tuvan basin areas (益蘭州 and 謙州).[20] Ogedei's grandson Kaidu occupied portions of Central Siberia from 1275 on. The Yuan dynasty army under Kublai's Kipchak general Tutugh reoccupied the Kyrgyz lands in 1293. From then on, the Yuan dynasty controlled large portions of Central and Eastern Siberia.[21]

South Asia

[edit]From 1221 to 1327, the Mongol Empire launched several invasions into the Indian subcontinent. The Mongols occupied parts of northwestern South Asia for decades. However, they failed to penetrate past the outskirts of Delhi and were repelled from the interior of India. Centuries later, the Mughals, whose founder Babur had Mongol roots, established their own empire in India.

Southeast Asia

[edit]Kublai Khan's Yuan dynasty invaded Burma between 1277 and 1287, resulting in the capitulation and disintegration of the Pagan Kingdom. However, the invasion of 1301 was repulsed by the Burmese Myinsaing Kingdom. The Mongol invasions of Vietnam (Đại Việt) and Java resulted in defeat for the Mongols, although much of Southeast Asia agreed to pay tribute to avoid further bloodshed.[22][23][24][25][26][27]

The Mongol invasions played an indirect role in the establishment of major Tai states in the region by recently migrated Tais, who originally came from Southern China, in the early centuries of the second millennium.[28] Major Tai states such as Lan Na, Sukhothai, and Lan Xang appeared around this time.

Europe

[edit]

The Mongols invaded and destroyed Volga Bulgaria and Kievan Rus', before invading Poland, Bulgaria, Hungary and other territories. Over the course of three years (1237–1240), the Mongols razed all the major cities of Russia with the exceptions of Novgorod and Pskov.[29]

Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, the Pope's envoy to the Mongol Great Khan, traveled through Kiev in February 1246 and wrote:

They [the Mongols] attacked Russia, where they made great havoc, destroying cities and fortresses and slaughtering men; and they laid siege to Kiev, the capital of Russia; after they had besieged the city for a long time, they took it and put the inhabitants to death. When we were journeying through that land we came across countless skulls and bones of dead men lying about on the ground. Kiev had been a very large and thickly populated town, but now it has been reduced almost to nothing, for there are at the present time scarce two hundred houses there and the inhabitants are kept in complete slavery.[30]

The Mongol invasions displaced populations on a scale never seen before in central Asia or eastern Europe. Word of the Mongol hordes' approach spread terror and panic.[31] The violent character of the invasions acted as a catalyst for further violence between Europe's elites and sparked additional conflicts. The increase in violence in the affected eastern European regions correlates with a decrease in the elite's numerical skills, and has been postulated as a root of the Great Divergence.[32]

Death toll

[edit]Due to the lack of contemporary records, estimates of the violence associated with the Mongol conquests vary considerably.[33] Not including the mortality from the Plague in Europe, West Asia, or China[34] it is possible that between 20 and 60 million people were killed between 1206 and 1405 during the various campaigns of Genghis Khan, Kublai Khan, and Timur.[35][36] However, the book from which the figures originate has been criticized for its methodology[37] and the Chinese censuses on which the estimates are based are considered unreliable.[38] Nevertheless, the campaigns killed a large number of people and involved battles, sieges,[39] early biological warfare,[40] and massacres.[41][42]

See also

[edit]- Destruction under the Mongol Empire

- Slave trade in the Mongol Empire

- Division of the Mongol Empire

- List of wars by death toll

- Lists of battles of the Mongol invasion of Europe

- Mongol invasion of Europe

- Mongol military tactics and organization

- Political divisions and vassals of the Mongol Empire

- Timeline of the Mongol Empire

- The Mongol Invasion (trilogy)

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Of necessity, the Mongols did most of their conquering and plundering during the warmer seasons, when there was sufficient grass for their herds. [...] Fuelled by grass, the Mongol empire could be described as solar-powered; it was an empire of the land. Later empires, such as the British, moved by ship and were wind-powered, empires of the sea. The American empire, if it is an empire, runs on oil and is an empire of the air."[4]

- ^ "This called for the employment of engineers to engaged in mining operations, to build siege engines and artillery, and to concoct and use incendiary and explosive devices. For instance, Hulagu, who led Mongol forces into the Middle East during the second wave of the invasions in 1250, had with him a thousand squads of engineers, evidently of north Chinese (or perhaps Khitan) provenance."[15]

References

[edit]- ^ "What Was the Deadliest War in History?". WorldAtlas. 10 September 2018. Archived from the original on 2019-10-09. Retrieved 2019-02-04.

- ^ White, M. (2011). Atrocities: The 100 deadliest episodes in human history. WW Norton & Company. p270.

- ^ "Overview of the Mongol Empire | World Civilization". courses.lumenlearning.com. Retrieved 2024-12-05.

- ^ a b "Invaders". The New Yorker. 18 April 2005. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ Pederson, Neil; Hessl, Amy E.; Baatarbileg, Nachin; Anchukaitis, Kevin J.; Di Cosmo, Nicola (25 March 2014). "Pluvials, droughts, the Mongol Empire, and modern Mongolia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (12): 4375–4379. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.4375P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1318677111. PMC 3970536. PMID 24616521.

- ^ Sinor, Denis (April 1995). "Western Information on the Kitans and Some Related Questions". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 115 (2): 262–269. doi:10.2307/604669. JSTOR 604669.

- ^ World Timelines – Western Asia – AD 1250–1500 Later Islamic Archived 2010-12-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Central Asian world cities Archived 2012-01-18 at the Wayback Machine", University of Washington.

- ^ a b Halperin, Charles J. (2000). "The Kipchak Connection: The Ilkhans, the Mamluks and Ayn Jalut". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 63 (2): 229–245. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00007205. JSTOR 1559539. S2CID 162439703.

- ^ Sinor, Denis (1999). "The Mongols in the West". Journal of Asian History. 33 (1): 1–44. JSTOR 41933117.

- ^ Morris Rossabi (1983). China Among Equals: The Middle Kingdom and Its Neighbors, 10th–14th Centuries. University of California Press. pp. 255–. ISBN 978-0-520-04562-0. Archived from the original on 2024-01-01. Retrieved 2020-11-01.

- ^ Howorth, H. H. (1870). "On the Westerly Drifting of Nomades, from the Fifth to the Nineteenth Century. Part III. The Comans and Petchenegs". The Journal of the Ethnological Society of London. 2 (1): 83–95. JSTOR 3014440.

- ^ Golden, Peter B. (1998). "Religion among the Qípčaqs of Medieval Eurasia". Central Asiatic Journal. 42 (2): 180–237. JSTOR 41928154.

- ^ Williams, Brian Glyn (2001). "The Ethnogenesis of the Crimean Tatars. An Historical Reinterpretation". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 11 (3): 329–348. doi:10.1017/S1356186301000311. JSTOR 25188176. S2CID 162929705.

- ^ Josef W. Meri, Jere L. Bacharach, ed. (2006). Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia, Vol. II, L–Z, index. Routledge. p. 510. ISBN 978-0-415-96690-0. Archived from the original on 2024-01-01. Retrieved 2011-11-28.

- ^ Hucker 1985 Archived 2015-09-10 at the Wayback Machine, p. 66.

- ^ Smith, John Masson (1998). "Nomads on Ponies vs. Slaves on Horses". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 118 (1): 54–62. doi:10.2307/606298. JSTOR 606298.

- ^ C.P.Atwood-Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire, p. 502

- ^ Nagendra Kr Singh, Nagendra Kumar – International Encyclopaedia of Islamic Dynasties, p.271

- ^ History of Yuan 《 元史 》,

- ^ C.P.Atwood-Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire, p.503

- ^ Taylor 2013 Archived 2023-04-13 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 103, 120.

- ^ ed. Hall 2008 Archived 2016-10-22 at archive.today, p. 159 Archived 2023-04-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Werner, Jayne; Whitmore, John K.; Dutton, George (21 August 2012). Sources of Vietnamese Tradition. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231511100. Archived from the original on 1 January 2024. Retrieved 1 November 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Gunn 2011 Archived 2023-04-06 at the Wayback Machine, p. 112.

- ^ Embree, Ainslie Thomas; Lewis, Robin Jeanne (1 January 1988). Encyclopedia of Asian history. Scribner. ISBN 9780684189017. Archived from the original on 1 January 2024. Retrieved 4 June 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Woodside 1971 Archived 2023-04-05 at the Wayback Machine, p. 8.

- ^ Lieberman, Victor (2003). Strange Parallels: Volume 1, Integration on the Mainland: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c.800–1830 (Studies in Comparative World History) (Kindle ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521800860.

- ^ "BBC Russia Timeline". BBC News. 2012-03-06. Archived from the original on 2018-03-18. Retrieved 2018-03-31.

- ^ The Destruction of Kiev Archived 2011-04-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Diana Lary (2012). Chinese Migrations: The Movement of People, Goods, and Ideas over Four Millennia. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 49. ISBN 9780742567658. Archived from the original on 2023-07-29. Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- ^ Keywood, Thomas; Baten, Jörg (1 May 2021). "Elite violence and elite numeracy in Europe from 500 to 1900 CE: roots of the divergence". Cliometrica. 15 (2): 319–389. doi:10.1007/s11698-020-00206-1. hdl:10419/289019. S2CID 219040903.

- ^ "Twentieth Century Atlas – Historical Body Count". necrometrics.com. Archived from the original on 2022-01-20. Retrieved 2019-02-04.

- ^ Maddison, Angus (2007). Chinese Economic Performance in the Long Run. Development Centre Studies. doi:10.1787/9789264037632-en. ISBN 978-92-64-03763-2.[page needed]

- ^ McEvedy, Colin; Jones, Richard M. (1978). Atlas of World Population History. New York, NY: Puffin. p. 172. ISBN 9780140510768.

- ^ Graziella Caselli, Gillaume Wunsch, Jacques Vallin (2005). "Demography: Analysis and Synthesis, Four Volume Set: A Treatise in Population". Academic Press. p.34. ISBN 0-12-765660-X

- ^ Guinnane, Timothy W. (2023). "We Do Not Know the Population of Every Country in the World for the Past Two Thousand Years". The Journal of Economic History. 83 (3): 912–938. doi:10.1017/S0022050723000293. ISSN 0022-0507.

- ^ Durand, John D. (1960). "The population statistics of China, A.D. 2–1953". Population Studies. 13 (3): 210–214, 228–230. doi:10.1080/00324728.1960.10405043. ISSN 0032-4728.

- ^ "Mongol Siege of Kaifeng | Summary". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2022-01-14. Retrieved 2019-02-04.

- ^ Wheelis, Mark (September 2002). "Biological Warfare at the 1346 Siege of Caffa". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 8 (9): 971–975. doi:10.3201/eid0809.010536. PMC 2732530. PMID 12194776.

- ^ Morgan, D. O. (1979). "The Mongol Armies in Persia". Der Islam. 56 (1): 81–96. doi:10.1515/islm.1979.56.1.81. S2CID 161610216. ProQuest 1308651973.

- ^ Halperin, C. J. (1987). Russia and the Golden Horde: the Mongol impact on medieval Russian history (Vol. 445). Indiana University Press.

Further reading

[edit]- Boyle, John Andrew The Mongol World Enterprise, 1206–1370 (London 1977) ISBN 0860780023

- Hildinger, Erik. Warriors of the Steppe: A Military History of Central Asia, 500 B.C. to A.D. 1700

- May, Timothy. The Mongol Conquests in World History (London: Reaktion Books, 2011) online review; excerpt and text search

- Morgan, David. The Mongols (2nd ed. 2007)

- Rossabi, Morris. The Mongols: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2012)

- Saunders, J. J. The History of the Mongol Conquests (2001) excerpt and text search

- Srodecki, Paul. Fighting the ‘Eastern Plague'. Anti-Mongol Crusade Ventures in the Thirteenth Century. In: The Expansion of the Faith. Crusading on the Frontiers of Latin Christendom in the High Middle Ages, ed. Paul Srodecki and Norbert Kersken (Turnhout: Brepols 2022), ISBN 978-2-503-58880-3, pp. 303–327.

- Turnbull, Stephen. Genghis Khan and the Mongol Conquests 1190–1400 (2003) excerpt and text search

- Bayarsaikhan Dashdondog. The Mongols and the Armenians (1220–1335). BRILL (2010)

Primary sources

[edit]- Rossabi, Morris. The Mongols and Global History: A Norton Documents Reader (2011)

External links

[edit]Mongol invasions and conquests

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Prelude

Steppe Nomadism and Tribal Dynamics

The Eurasian steppe, a vast grassland expanse characterized by extreme seasonal variations—harsh winters with temperatures dropping below -40°C and arid summers—shaped the pastoral nomadism of 12th-century Mongols, who relied on mobile herding of sheep, goats, horses, cattle, and camels for subsistence, producing meat, dairy, hides, and wool while trading surplus animals and products for grains, iron, and textiles from sedentary neighbors.[8][9] This transhumant lifestyle necessitated portable felt yurts and seasonal migrations covering hundreds of kilometers annually to exploit sparse pastures, with horses serving as the economic and cultural cornerstone due to their role in transport, breeding (each household owning 10-20 mounts), and milk production alongside meat.[10] The system's resilience stemmed from diversified herds mitigating risks like dzuds (severe winter kills), though it engendered chronic resource scarcity, driving raids on settled societies for supplementary goods.[11] Social organization among Mongols centered on patrilineal clans (obog) grouped into tribes (aymag), forming loose, segmentary confederations without fixed hierarchies, where authority derived from kinship ties, personal charisma, and success in vendettas or alliances rather than institutionalized states.[12] Prominent pre-unification tribes included the Borjigins (Genghis Khan's clan), Tayichiuds, Merkits, Tatars, Keraites, and Naimans, each numbering tens of thousands and competing over grazing territories, brides, and tribute from weaker groups, with khans emerging via election among elders or through martial prowess to lead temporary coalitions.[13] Women held influence in clan decisions and could lead in absences, but patrilineal descent and bride-capture practices reinforced male dominance, while slaves from raids bolstered labor for herding and crafting.[12] Tribal dynamics were defined by endemic feuds and opportunistic warfare, where disputes over pastures or honor escalated into cycles of revenge killings, fostering a meritocratic warrior ethos in which males trained from childhood in mounted archery and horsemanship, enabling hit-and-run tactics with composite bows effective up to 300 meters.[10] Alliances shifted via marriages or anda (blood-brotherhood) pacts, but betrayal was common, as seen in the Jin dynasty's 1161-1206 manipulation of rival tribes like the Tatars against others, exacerbating fragmentation and preventing stable polities larger than 100,000 persons. This volatility, combined with external pressures from Chinese states and internal ecological stresses, created conditions ripe for a unifying figure, as fragmented loyalties prioritized survival through adaptability over rigid fealty.[11]Unification Under Genghis Khan

Temüjin, born circa 1162 near the Onon River as the son of Yesügei, a minor chieftain of the Borjigin clan, experienced early hardship after his father's poisoning by Tatars around age nine, leading to the family's abandonment by their tribe and years of poverty and nomadic scavenging. To assert authority, Temüjin killed his half-brother Bekter in a dispute over a fish and bird, an act that consolidated his leadership despite violating Mongol customs against fratricide. Captured briefly by the rival Tayichi'ud clan in his youth, he escaped with aid from a sympathetic guard, forging resilience and loyalty networks essential for his later ascent. Temüjin built initial power through strategic alliances, including a blood brotherhood (anda) with Jamukha and kinship ties to Togrul (Wang Khan) of the Keraites, whose support helped him rescue his wife Börte after her abduction by the Merkits in the late 1170s or early 1180s.[14] These partnerships enabled early raids, but tensions arose as Temüjin's egalitarian merit-based following clashed with Jamukha's traditionalist views favoring aristocratic rule, culminating in their split around 1186 and Temüjin's defeat by Jamukha's coalition at Dalan Baljut circa 1187–1190, where loyalists were brutally executed by boiling.[15] Regrouping with a core of devoted followers, Temüjin emphasized personal loyalty over tribal ties, attracting defectors through just governance and shared spoils.[16] From the late 1190s, Temüjin systematically subdued rival groups: he allied with Togrul to defeat the Tatars in 1202, executing their leaders in revenge for Yesügei's death and incorporating survivors into his forces. Turning on Togrul after perceived betrayal, Temüjin crushed the Keraites around 1203; he then overcame the Naimans in 1204 at the Battle of Chakirmaut, capturing their leader Tayang and eliminating Jamukha, who sought ritual death rather than submission.[16] Campaigns against remaining Merkits and other steppe nomads followed, dismantling tribal structures through mass executions of elites and absorption of warriors.[16] In 1206, at a kurultai (noble assembly) on the Onon River, Temüjin was acclaimed Chinggis Khan—"universal ruler"—formalizing the unification of Mongol and Turkic tribes into a confederation roughly four times the area of France, bound by decimal military organization, a written code (Yasa), and centralized command that prioritized capability over birth.[16] This synthesis of nomadic warfare prowess and administrative innovation ended centuries of inter-tribal fragmentation, enabling outward expansion.[16]Environmental Enablers of Expansion

The Eurasian Steppe's vast, open grasslands, extending over 8,000 kilometers from the Danube River to the Pacific Ocean, fostered a nomadic pastoral economy centered on herding sheep, goats, cattle, and especially horses, which were indispensable for mobility and warfare. This terrain's relative flatness and aridity in non-pluvial periods selected for hardy, self-sufficient horse breeds capable of foraging on sparse vegetation, allowing Mongol warriors to maintain remounts—typically three to five per rider—for sustained campaigns covering hundreds of kilometers without resupply.[17][18] Paleoclimatic evidence from tree-ring chronologies in central Mongolia reveals an unprecedented "Mongol Pluvial" from 1211 to 1225 CE, characterized by consistently above-average moisture (mean self-calibrating Palmer Drought Severity Index of 0.600) and warmer temperatures (anomaly of -0.118°C relative to long-term means), conditions not replicated in the prior 1,112 years.[19] This wetter regime enhanced grassland biomass production, enabling exponential growth in livestock herds, including the horses vital for cavalry forces estimated at over 100,000 by the 1220s, thereby amplifying the Mongols' logistical capacity for conquest.[19][18] These environmental factors converged to facilitate tribal unification under Temujin (later Genghis Khan) around 1206 CE, as resource abundance reduced inter-tribal competition over pastures and supported larger confederations capable of offensive warfare, contrasting with drier periods that historically fragmented steppe societies.[19][20] The steppe's connectivity to adjacent sedentary regions, combined with this climatic window, thus provided the ecological basis for the Mongols' outward expansion into China, Central Asia, and beyond, where horse-adapted tactics exploited similar open landscapes.[18]Military Framework

Cavalry Tactics and Archery Superiority

The Mongol army's core strength lay in its light cavalry, composed primarily of horse archers who could sustain high mobility across vast distances while delivering volleys of arrows. Each warrior maintained multiple horses—typically three to five—to rotate mounts, enabling non-stop travel at speeds up to 100 kilometers per day without exhausting their animals, a logistical edge that allowed rapid concentration of forces against slower infantry-based armies.[21] This mobility was honed through rigorous training starting in childhood, where boys as young as five learned to ride and shoot simultaneously, fostering innate proficiency in mounted archery that far surpassed the dismounted or heavy cavalry tactics of contemporaries like European knights or Chinese infantry.[22] Central to their superiority was the composite recurve bow, constructed from layers of horn, wood, and sinew, which achieved draw weights of 100 to 160 pounds and effective ranges of 200 to 300 meters—outdistancing most rival bows such as the English longbow's practical combat range of around 200 meters.[23] These bows delivered arrows with greater velocity and penetration due to their compact design and high energy storage, allowing archers to fire up to 10-12 aimed shots per minute from horseback without needing to halt, a feat enabled by thumb rings for precise control.[24] In contrast to the self bows used by many sedentary powers, the Mongol composite bow's reflexed shape provided superior power-to-size ratio, making it ideal for the dynamic warfare of the steppes and contributing to their ability to harass and dismantle formations before close engagement.[25] Tactical doctrine emphasized deception and encirclement, with feigned retreats—a hallmark steppe maneuver—used to lure overconfident pursuers into ambushes where flanking tumens (units of 10,000) could unleash devastating arrow storms from concealed positions.[26] This caracole tactic involved cavalry wheeling in coordinated circles to maintain continuous fire while evading counterattacks, exploiting the archers' accuracy and the horses' endurance to wear down numerically superior foes without risking direct melee until the enemy was disorganized.[27] Such methods proved decisive in engagements like the 1211 campaigns against the Jin dynasty, where Mongol horsemen's sustained ranged harassment collapsed fortified lines, demonstrating causal superiority rooted in integrated mobility, firepower, and discipline rather than mere numbers.[28]Siege Engineering and Adaptations

The Mongols, as steppe horsemen accustomed to mobile warfare, initially lacked sophisticated siege capabilities and preferred to compel surrenders through terror or outmaneuvering defenders.[29] To conquer walled cities, they adapted by systematically incorporating engineers from conquered civilizations, beginning with Chinese artisans captured from the Western Xia and Jin dynasties after campaigns in 1209–1227.[30] These specialists provided expertise in constructing trebuchets, catapults, and other engines, which the Mongols transported disassembled via wagon trains for on-site assembly.[30] In the invasion of the Khwarezmian Empire from 1219 to 1221, Mongol forces under Genghis Khan deployed thousands of Chinese engineers to reduce fortified centers like Otrar, which fell after a five-month siege involving battering rams, siege towers, and stone-throwing mangonels.[31] Persian engineers, conscripted following the Khwarezm conquest, further enhanced capabilities with advanced counterweight trebuchets and incendiary devices using naphtha.[32] By Ögedei's reign (1229–1241), these adaptations allowed rapid assaults on urban strongholds, as seen in the swift capture of Rus' cities with hybrid forces combining Mongol mobility and engineered artillery.[29] Later expansions under Möngke and Hülegü integrated gunpowder technologies, including bombs and flame-throwers derived from Chinese formulations, marking an early adoption of explosive siege warfare.[32] Against European stone castles during the 1241 invasion of Hungary, Mongols employed mining, ramp construction, and portable ballistae, though logistical strains limited prolonged engagements.[30] This pragmatic assimilation of foreign techniques—prioritizing effectiveness over cultural origin—transformed the Mongol army into a versatile besieging force capable of toppling diverse fortifications across Eurasia.[29]Logistics, Intelligence, and Psychological Warfare

The Mongol armies' logistical system relied on the mobility of nomadic pastoralism, with each warrior maintaining 3 to 5 horses for rotation, enabling sustained marches of up to 100 miles per day without reliance on fixed supply trains.[33] This horse-based approach minimized baggage, as warriors carried dried milk curds (airag) and blood from their mounts for sustenance during extended campaigns, supplemented by foraging, hunting, and requisitions from conquered populations.[33] The yam relay network, initiated under Genghis Khan around 1224 and expanded by Ögedei, established stations approximately 25 to 40 miles apart stocked with remount horses, fodder, and provisions, facilitating rapid movement of couriers, reinforcements, and light supplies across vast distances.[34] [35] These stations, manned by local levies, supported operational tempo by allowing armies to project power deep into enemy territory, as seen in the 1219–1221 invasion of Khwarezm where forces traversed over 1,000 miles from Mongolia while maintaining cohesion.[35] Intelligence gathering formed a cornerstone of Mongol strategy, employing nököd (companion scouts) and embedded spies to map terrain, assess fortifications, and identify political divisions prior to major offensives.[36] Genghis Khan dispatched merchant networks and disguised agents into target regions years in advance, as during the prelude to the 1219 Khwarezm campaign, where informants revealed internal rivalries and military dispositions, enabling precise strikes against divided foes.[37] Advanced parties of 1,000–10,000 riders reconnoitered routes and ambushes, relaying real-time data via signal flags, smoke, or mounted messengers to central command, which minimized surprises and maximized exploitation of enemy weaknesses.[36] This apparatus, drawing on steppe traditions of tribal surveillance, proved decisive in operations like the 1223 Battle of the Kalka River, where scouts detected Kipchak-Cuman alliances and facilitated encirclement.[37] Psychological warfare amplified Mongol military efficacy through deliberate terror and deception, cultivating a reputation for indiscriminate brutality to induce preemptive surrenders and erode enemy cohesion.[38] Tactics included mass executions of resistors—such as the 1219 slaughter of Nishapur's population, with skulls stacked into pyramids—and public displays of severed heads to signal defiance's cost, prompting cities like Merv to capitulate without siege in 1221.[38] Feigned retreats, a steppe-derived ruse, lured pursuers into ambushes, as at the 1221 Battle of Vâliyân where simulated routs drew Khwarezmian forces into arrow barrages, exploiting overconfidence.[39] Rumors amplified by defectors and spies further demoralized opponents, with Mongol envoys demanding submission under threat of annihilation, a method that secured tribute from distant realms without full mobilization.[39]Phases of Conquest

Genghis Khan's Core Campaigns (1206–1227)

Following his proclamation as Genghis Khan in 1206 and unification of Mongol tribes, Genghis initiated expansion southward against sedentary neighbors. The first target was the Tangut Western Xia kingdom, a vassal of the Jin dynasty, with initial raids launched in 1207 to test defenses and secure tribute.[40] A full-scale invasion followed in 1209, with Mongol forces besieging the capital Yinchuan after overrunning frontier garrisons; facing starvation and Mongol demands for submission, Emperor Li Dewang capitulated, pledging troops, tribute, and his daughter's hand in marriage, though tensions persisted due to Western Xia's alliances with Jin.[40] Emboldened, Genghis declared war on the Jin dynasty in 1211, mobilizing approximately 100,000-120,000 cavalry to cross the Gobi Desert and assault northern China.[41] At the Battle of Yehuling (Wild Fox Ridge) in 1211, Mongol archers decimated Jin field armies numbering over 200,000, enabling rapid advances that sacked cities like Zhongde and Xijing.[31] By 1213, Mongol tumens ravaged the heartland, prompting Jin Emperor Xuanzong to sue for peace, which Genghis rejected; the campaign culminated in the 1214-1215 siege of Zhongdu (modern Beijing), where Jin defenders endured famine until surrendering in May 1215, after which the city was razed and its population massacred or enslaved.[41] Jin forces regrouped but suffered further defeats, marking the effective collapse of their northern defenses by 1215.[31] Consolidation in Mongolia followed, interrupted by the 1218 incident at Otrar, where Khwarezmian governor Inalchuq executed a Mongol caravan of 450 merchants and envoys, provoking Genghis's wrath.[42] In 1219, Genghis dispatched an army estimated at 100,000-200,000, dividing into three columns: one besieged Otrar for five months until its fall in February 1220, with Inalchuq boiled in silver; simultaneous assaults captured Bukhara (February 1220) and Samarkand (March 1220), where defenders numbering 110,000 surrendered after internal betrayal and Mongol feigned retreats.[42] Shah Muhammad II fled westward, pursued by generals Jebe and Subutai to the Caspian Sea, where he died in exile; his son Jalal al-Din rallied at the Battle of Parwan in 1221 but was routed at the Indus River later that year, escaping to India despite Mongol numerical superiority.[42] Returning eastward in 1222-1225 via Afghanistan and the Caucasus—where Subutai's detachment defeated Georgians and probed Rus' principalities—Genghis addressed Western Xia's rebellion, allied with Jin against Mongols.[40] The 1226 campaign overran Tangut cities like Lingzhou, killing its leaders, and advanced on Yinchuan by 1227; as the capital fell amid dike breaches flooding Mongol camps, Genghis succumbed to illness or injury on August 18, 1227, aged 65, leaving the conquest incomplete but Western Xia vassalized under Mongol oversight.[43] These campaigns expanded Mongol territory from the Altai Mountains to the Indus, incorporating diverse peoples through terror, tribute extraction, and selective integration of engineers and artisans, while amassing wealth from plundered treasuries estimated in millions of ingots.[40]Ögedei's Western and Eastern Advances (1229–1241)

Following Ögedei Khan's confirmation as Great Khan in 1229 after a regency period, he convened a grand kurultai and initiated systematic conquests to fulfill Genghis Khan's ambitions, dispatching tumens across fronts while establishing administrative reforms to support expansion.[44] In the east, Ögedei resumed the assault on the Jin dynasty in 1230, coordinating with allied Song forces initially, but the campaign intensified with Mongol forces under commanders like Tolui besieging key cities.[45] The siege of Kaifeng, the Jin capital, began in April 1232 with approximately 15,000 Mongol troops encircling the city, enduring over a year of resistance involving early gunpowder weapons before its surrender in 1233 due to starvation and bombardment.[46] The Jin emperor Aizong fled to Caizhou, where Tolui's forces captured and executed him on February 9, 1234, extinguishing the dynasty after 23 years of intermittent warfare.[47] Ögedei also launched invasions into Korea starting in 1231, ordering general Saritai to cross the Yalu River and seize Uiju, initiating a series of campaigns against Goryeo that devastated northern regions but faced fierce guerrilla resistance and climatic challenges, compelling temporary withdrawals despite initial gains.[48] Following the Jin collapse, Mongol armies turned southward in 1234–1235, declaring war on the Song dynasty and conducting raids into Sichuan and Henan, though full conquest extended beyond Ögedei's reign due to Song naval defenses and terrain.[49] In the southwest, Ögedei dispatched Chormaqan Noyan with 30,000–50,000 troops in winter 1230 from Bukhara to consolidate Persia, where the commander subdued Isfahan, Hamadan, and other centers by 1231–1233, extending control over Khorasan and linking with later Transcaucasian operations while suppressing local revolts.[50] The most extensive western advances formed the Great Western Campaign ordered by Ögedei in 1235, led by Batu Khan (Jochi's son) with Subutai and other princes commanding up to 120,000–150,000 warriors across multiple tumens.[5] From 1236, forces subjugated Volga Bulgaria and pursued Kipchak-Cuman nomads across the steppes, then invaded Rus' principalities in 1237, destroying Ryazan in December and defeating Grand Prince Yuri II at the Battle of the Sit River on March 4, 1238, followed by the sack of Vladimir and Suzdal.[5] Kiev fell on December 6, 1240, after a siege employing stone-throwers and incendiaries, with massacres and conscription of survivors.[5] In 1241, the campaign penetrated deeper into Europe: a detachment under Orda Khan raided Poland, crushing Duke Henry II at the Battle of Legnica on April 9, while Batu and Subutai's main army annihilated King Béla IV's Hungarians at the Battle of Mohi on April 11, devastating the kingdom and advancing toward Vienna before Ögedei's death on December 11, 1241, prompted a withdrawal to confirm succession, halting momentum.[5] These operations incorporated auxiliary troops from subjugated peoples and demonstrated Mongol adaptability in combined arms tactics across diverse terrains.Later Successors' Invasions (1240s–1290s)

Following the death of Ögedei Khan in 1241, internal power struggles temporarily halted major Mongol offensives, but under Möngke Khan (r. 1251–1259), campaigns resumed with renewed vigor across multiple fronts. Möngke dispatched his brother Hulagu westward with an army estimated at 100,000–150,000 troops to subdue remaining Islamic strongholds.[51] Hulagu first targeted the Nizari Ismaili fortresses in Persia, systematically dismantling their network of mountain castles between 1253 and 1256 through sieges employing advanced trebuchets and sappers.[52] In 1258, Hulagu advanced on Baghdad, the Abbasid Caliphate's capital, which housed a population exceeding 1 million and served as a center of Islamic scholarship. Despite the Caliph al-Musta'sim's appeals and a Mongol demand for submission, the city resisted; after a 12-day siege beginning January 29, Mongol forces breached the walls, leading to widespread slaughter and destruction, with estimates of deaths ranging from 200,000 to over 1 million.[51][53] The caliph was executed by being trampled, ending the Abbasid dynasty after 500 years. Hulagu's forces then captured Aleppo and Damascus in early 1260, but Möngke's death prompted a withdrawal of main forces, leaving a detachment under Kitbuqa defeated by Mamluk Sultan Qutuz at the Battle of Ain Jalut on September 3, 1260, marking the easternmost limit of Mongol expansion in the Levant.[51] Concurrently, Möngke directed Kublai Khan eastward to consolidate gains in China. Kublai conquered the Dali Kingdom in 1253–1254, incorporating its territories into Mongol control. Against the Southern Song dynasty, initial probes in the 1250s yielded limited success due to Song naval superiority and fortified cities, but under Kublai (r. 1260–1294), who founded the Yuan dynasty in 1271, the siege of Xiangyang (1268–1273) proved pivotal; Mongol adoption of Muslim-engineered counterweight trebuchets forced its surrender, opening the Yangtze River basin.[54] The Song capital Lin'an fell in 1276, though pockets of resistance persisted until the naval Battle of Yamen on March 19, 1279, where Song forces were annihilated, drowning Emperor Bing and completing the conquest after over two decades of campaigning.[54] Kublai's ambitions extended overseas, launching invasions against Japan in 1274 and 1281 from Korean ports. The first assault involved approximately 15,000–40,000 troops landing in Hakata Bay, Kyushu, where samurai repelled them after brief clashes, aided by a storm that wrecked much of the fleet of around 900 ships.[55] The second, larger expedition in 1281 mobilized over 140,000 soldiers in 4,400 vessels; after initial landings and battles, a typhoon—later termed kamikaze or "divine wind"—devastated the armada, drowning tens of thousands and halting the invasion.[55] In Southeast Asia, Mongol forces under generals like Uriyangqadai invaded Dai Viet (Vietnam) in 1258 during the Song campaign, compelling temporary submission from the Tran dynasty through scorched-earth tactics and elephant warfare, though full conquest eluded them. Subsequent Yuan expeditions in 1285 and 1287–1288, involving up to 500,000 troops, faced guerrilla resistance, ambushes in tropical terrain, and disease, resulting in withdrawals after pyrrhic victories and tributary arrangements rather than annexation. Similar forays into Burma (1277, 1283, 1287) and Java (1293) yielded tribute but no lasting dominion due to logistical strains and local countermeasures. The Golden Horde, under Batu Khan's successors like Berke (r. 1257–1266), focused on consolidating Russian principalities through tribute extraction rather than new European incursions, though raids into Poland (1259, 1287) and the Balkans occurred on a smaller scale without territorial gains. Inter-khanate rivalries, such as Berke's war with Hulagu over Caucasian pastures (1262–1265), diverted resources from further expansion, signaling the fragmentation of unified Mongol conquest efforts by the late 13th century.[56]Regional Outcomes

Central Asia and Khwarezm

The Mongol conquest of the Khwarezmian Empire from 1219 to 1221 marked the decisive incorporation of Central Asia into the burgeoning Mongol domain, driven by Genghis Khan's response to provocations from Shah Ala ad-Din Muhammad II. The Khwarezmian realm, encompassing Transoxiana, Khorasan, and adjacent territories, had risen as a Turkic-Persian power under the shah's rule, controlling key Silk Road hubs like Samarkand and Bukhara. In 1218, a Mongol trade caravan was massacred in Otrar by the city's governor, Inalchuq, prompting Genghis to dispatch envoys demanding justice; the shah executed one and humiliated the others, igniting the invasion.[57][42] Genghis assembled a force of approximately 120,000 to 150,000 troops, dividing it among his sons Jochi, Chagatai, and Ögedei to pursue a multi-pronged assault.[58] The campaign commenced in autumn 1219 with the siege of Otrar, which resisted for five months until its fall in February 1220; Inalchuq was executed by having molten silver poured into his eyes and ears, as per Mongol retribution for the caravan's slaughter. Bukhara yielded in March 1220 after minimal resistance, its wooden fortifications burned and much of the population massacred or enslaved, though artisans were spared for relocation to Mongol territories. Samarkand, the empire's capital, surrendered shortly thereafter following a siege involving trebuchets and massed archery; Genghis personally oversaw the execution of up to 30,000 soldiers and officials, with the city's irrigation systems deliberately destroyed to render it uninhabitable.[42][59] The shah fled westward, pursued relentlessly, and perished in December 1220 on an island in the Caspian Sea from pleurisy.[60] Jalal al-Din Mingburnu, the shah's capable son, rallied remnants of the Khwarezmian forces, achieving a temporary victory over a Mongol detachment at the Battle of Parwan in 1221 through superior terrain use and infantry tactics. However, Genghis decisively crushed this resistance at the Battle of the Indus in November 1221, where Jalal al-Din escaped by swimming his horse across the river under pursuit, though his forces suffered heavy losses. The Mongols systematically razed resistant cities, including Urgench (Gurganj), where floods were unleashed to aid the assault, leading to near-total depopulation.[58][42] The conquest inflicted catastrophic demographic losses on Central Asia, with Persian chroniclers like Juvayni reporting figures such as 1.7 million deaths at Nishapur and over 1 million at Merv, though these estimates from post-conquest sources under Mongol patronage likely reflect policy-driven terror to deter rebellion rather than precise tallies and are subject to scholarly skepticism for potential inflation. Modern analyses suggest total fatalities in the millions across the region, depopulating urban centers and disrupting agricultural systems for generations, as evidenced by archaeological evidence of abandoned qanats and reduced settlement density.[61][58] The surviving Khwarezmian elite fragmented, with Jalal al-Din continuing guerrilla warfare until his death in 1231, but the empire's core was annexed as the Chagatai Khanate under Chagatai, integrating Central Asian resources into Mongol logistics for further expansions.[60] This phase underscored Mongol superiority in mobility, intelligence, and psychological intimidation, exploiting Khwarezmian disunity and overextended garrisons.[42]China and Korea

The Mongol conquest of northern China began under Genghis Khan with campaigns against the Western Xia (Tangut Empire). In 1209, Mongol forces invaded Western Xia after it withheld tribute, capturing the capital Yinchuan after a prolonged siege involving damming the Yellow River to flood defenses; the Tanguts submitted as vassals by 1210, providing troops and tribute.[62] Western Xia rebelled in 1223, prompting a second invasion in 1226; Genghis Khan besieged the capital again with around 180,000 troops, leading to its fall in 1227 just before his death, effectively annihilating the dynasty as a political entity.[31] Simultaneously, from 1211, Genghis Khan launched major offensives against the Jurchen Jin Dynasty, defeating its armies at the Battle of Badger Pass and Wild Fox Ridge, which killed over 90,000 Jin troops and opened northern China to Mongol control.[62] By 1215, the Mongols had captured Zhongdu (modern Beijing), forcing Jin relocation southward; under Ögedei Khan, the campaign resumed, culminating in the 1232-1233 siege of Kaifeng and the dynasty's collapse in 1234 after joint Mongol-Song efforts turned hostile toward the Song.[63] The Southern Song Dynasty initially allied with the Mongols against Jin but faced invasion thereafter; Möngke Khan's 1258-1259 campaign reached modern Hunan before his death, after which Kublai Khan assumed leadership.[64] Kublai proclaimed the Yuan Dynasty in 1271, completing the conquest by 1276 with the capture of the Song capital Lin'an and the Battle of Yamen in 1279, where the last Song resistance ended with over 200,000 deaths, integrating all China under Mongol rule.[56] In Korea, the Goryeo Kingdom endured six major Mongol invasions from 1231 to 1259 under Ögedei and his successors, beginning with Saritai's crossing of the Yalu River and conquest of northwestern territories.[65] Goryeo's court retreated to Ganghwa Island, employing scorched-earth tactics and naval defenses, which prolonged resistance despite Mongol forces numbering up to 30,000 per campaign and devastating the mainland, including the destruction of Kaesong in 1232.[66] By 1259, after installing puppet kings and extracting tribute, Goryeo submitted as a vassal, supplying 10,000 troops for Mongol wars and royal brides, while retaining internal autonomy until the Yuan's fall.[65]Persia and the Middle East

The Mongol conquest of Persia and the Middle East was primarily executed under Hulagu Khan, grandson of Genghis Khan, who was dispatched westward by Great Khan Möngke in 1253 with an army estimated at 130,000 troops.[67] Hulagu's forces first targeted the Nizari Ismaili Assassins, capturing their stronghold at Alamut in November 1256 after a prolonged siege, effectively dismantling their network of fortresses across Persia.[68] This paved the way for the campaign against the Abbasid Caliphate, culminating in the siege of Baghdad. In late 1257, Hulagu advanced on Baghdad, crossing the Tigris River on January 16, 1258, and capturing the western suburbs by January 22 after breaching defenses with catapults and flooding tactics.[52] The Abbasid Caliph al-Mustaʿsim surrendered on February 10, 1258, following the defeat of his 12,000-strong army, which suffered heavy losses.[52] The subsequent sack of the city resulted in the massacre of approximately 80,000 inhabitants, widespread destruction of infrastructure, and the execution of the caliph by strangulation, marking the end of the Abbasid dynasty and a profound blow to Islamic political unity.[52] Christians in Baghdad were largely spared due to intercession by Hulagu's Christian wife.[52] Following Baghdad's fall, Hulagu's armies invaded Syria in early 1260, swiftly capturing Aleppo after a brief siege and then Damascus, subjugating the remnants of the Ayyubid dynasty.[68] However, Hulagu withdrew much of his forces to Mongolia for the kurultai election after Möngke's death in 1259, leaving a smaller contingent under Kitbuqa Noyan. This detachment was decisively defeated by Mamluk forces led by Sultan Qutuz and Baybars at the Battle of Ain Jalut on September 3, 1260, halting Mongol expansion into Egypt and representing their first major reversal in the region.[69] Hulagu established the Ilkhanate in 1256, ruling over Persia, Mesopotamia, and parts of the Caucasus from bases in Azerbaijan, with Tabriz as a key capital.[67] The khanate consolidated control amid initial devastation, including depopulation from earlier Genghis-era raids that razed Persian cities like Herat and Nishapur in 1221–1222.[68] Successors such as Ghazan Khan (r. 1295–1304) adopted Islam in 1295, promoting administrative reforms, agricultural recovery, and patronage of Persian culture, though internal strife and failed campaigns against the Mamluks persisted until the dynasty's fragmentation after Abū Saʿīd's death in 1335 without heirs.[67] The Ilkhanate's rule facilitated eventual stabilization but at the cost of massive human losses, with contemporary accounts estimating millions dead across the invasions, though exact figures remain debated due to potential exaggeration in chronicles.[68]Eastern Europe and Rus' Principalities

The first Mongol contact with the Rus' principalities occurred at the Battle of the Kalka River on May 31, 1223, where a vanguard force led by generals Subutai and Jebe defeated a coalition of Rus' princes and Cuman nomads, resulting in heavy losses for the Eastern European forces due to tactical errors during pursuit of a feigned retreat.[70][71] This reconnaissance raid did not lead to immediate conquest, as the Mongols withdrew to pursue campaigns elsewhere.[72] The systematic invasion of the Rus' lands commenced in late 1237 under Batu Khan, grandson of Genghis Khan, with an army estimated at 120,000-150,000 troops targeting the fragmented principalities. Ryazan fell in December 1237 after a brief siege, its defenders slaughtered and the city razed, setting a pattern of rapid assaults using siege engines adapted from Chinese technology. Vladimir-Suzdal followed in February 1238, with the grand prince's capital captured and burned despite resistance, leading to the massacre of inhabitants.[73] Kozelsk resisted for seven weeks in early 1238, earning the moniker "Zhelezna" (Ironside) from the Mongols, but ultimately succumbed after prolonged bombardment.[74] By 1240, the Mongols turned south, besieging and sacking Kiev in December after breaching its walls with mangonels and trebuchets, effectively ending the city's dominance as the Rus' political center. The campaign devastated numerous principalities, including Chernigov and Galicia-Volhynia, with contemporary chronicles reporting widespread destruction and population losses estimated by some historians at up to 5% of the total Rus' populace. Surviving princes submitted, establishing a vassalage system under the Golden Horde, Batu's ulus centered at Sarai on the Volga, requiring tribute payments in silver, furs, and manpower, enforced through periodic censuses starting around 1259.[72][75] In spring 1241, Mongol tumens under Batu and Subutai extended operations westward into Eastern Europe proper, dividing forces to strike Poland and Hungary simultaneously to prevent reinforcements. On April 9, 1241, at the Battle of Legnica (Liegnitz), a Mongol detachment of approximately 10,000-20,000 under Orda and Baidar routed a Polish-led coalition of 20,000-30,000 including Teutonic Knights and Moravians, employing feigned retreats and archery to shatter the heavy cavalry charge led by Duke Henry II the Pious, who was killed and his head paraded on a spear. Concurrently, the main army crushed Hungarian forces under King Béla IV at the Battle of Mohi (Sajó River) on April 11, 1241, encircling the camp with night assault and fire arrows, inflicting catastrophic defeats that razed much of Hungary but spared deeper penetration due to logistical strains.[76][77] The European campaigns halted upon news of Great Khan Ögedei's death in December 1241, prompting Batu's recall for the kurultai succession, though raids persisted sporadically. Rus' principalities endured over two centuries of Horde overlordship, with princes securing legitimacy via yarlyks (charters) from the khan, fostering a tributary economy that integrated steppe fiscal practices while preserving local Orthodox hierarchies under nominal suzerainty.[78]South and Southeast Asia Attempts

The Mongol Empire's expansion into South Asia was limited primarily to raids and incursions from the northwest, originating from the Chagatai Khanate and occasionally the Ilkhanate, rather than full-scale conquest. In 1221, Genghis Khan pursued the Khwarazmian prince Jalal al-Din Mangburni across the Indus River into Punjab, sacking several cities but withdrawing without establishing control, as the primary campaign focused on Central Asia.[79] Subsequent attempts from the 1230s onward targeted the Delhi Sultanate, with forces under leaders like Bahadur Tair besieging Lahore in 1241 and attacking Multan in 1247, extracting temporary indemnities but failing to penetrate deeper due to fortified defenses and rapid Sultanate reinforcements.[80] Under Sultan Alauddin Khalji (r. 1296–1316), the Delhi Sultanate repelled multiple major incursions between 1297 and 1308, including the Battle of Kili in 1299 where Qutlugh Khwaja's Chagatai forces were defeated by combined Sultanate cavalry and infantry tactics, and further raids in 1305–1306 that ended in Mongol retreats after heavy losses.[79] [80] These failures stemmed from the Sultanate's strategic preparations, such as standing armies, frontier forts in Punjab and Sindh, and generals like Zafar Khan who exploited Mongol overextension; internal divisions among Mongol khanates, including succession disputes, further diluted coordinated efforts post-Genghis Khan.[80] Later feeble attempts, such as Tarmashirin's 1327 siege of Delhi, were lifted after ransom payments under the Tughlaq dynasty, marking the effective end of serious threats by the mid-14th century without any territorial gains south of the Indus.[79] In Southeast Asia, the Yuan dynasty under Kublai Khan pursued tributary submission through military expeditions starting in the 1270s, targeting kingdoms in Vietnam, Burma, and Java, but achieved only nominal suzerainty amid repeated withdrawals. The first probe into Dai Viet (Vietnam) occurred in 1258 with a force seeking routes against the Song, but full invasions followed in 1285 and 1287–1288, where Tran dynasty forces under generals like Tran Hung Dao employed scorched-earth tactics, river ambushes, and war elephants to harass Mongol supply lines, leading to retreats exacerbated by tropical diseases and monsoon floods.[54] Against the Pagan Kingdom in Burma, Yuan armies numbering around 12,000 invaded in 1277, defeating forces at Ngasaunggyan and occupying frontier posts, followed by advances in 1283–1284 and a decisive 1287 campaign that sacked the capital Bagan, forcing the king's flight and assassination; however, control remained fleeting as heat, jungle exhaustion, and local guerrilla resistance prevented sustained occupation, reducing Burma to intermittent tribute.[81] The 1292–1293 Java expedition, involving 20,000–30,000 troops and 1,000 ships dispatched to install a puppet ruler, initially succeeded in deposing Kertanegara but collapsed when local ally Raden Wijaya ambushed the Mongols, inflicting 3,000 casualties and prompting a full retreat amid unfamiliar terrain and logistical breakdowns.[81] [54] Overarching factors for these setbacks included the Mongols' steppe-adapted cavalry's vulnerability to humid climates, disease outbreaks, elongated supply chains across seas and rivers, and adaptive local strategies that avoided pitched battles, contrasting with successes on open Eurasian plains.[54]Imperial Administration and Integration

Yassa Legal Code and Meritocracy

The Yassa, also known as the Great Yasa, refers to a body of laws, decrees, and customs attributed to Genghis Khan, formalized following his unification of the Mongol tribes in 1206.[82] It functioned primarily as an oral tradition enforced through strict discipline rather than a comprehensive written codex, with no surviving original texts and scholarly debate over whether it constituted a unified legal code or a collection of ad hoc edicts and steppe customs adapted for imperial governance.[83] [84] Key provisions emphasized absolute obedience to the Khan, suppression of tribal feuds to foster unity among nomadic clans, and severe punishments for offenses such as theft, adultery, and desertion, often involving execution to deter disloyalty and maintain order in diverse conquest armies.[85] Enforcement relied on a hierarchy of darughachi overseers and collective responsibility within military units, where violations by one member could implicate the entire group, ensuring rapid compliance across vast territories.[86] The Yassa's structure promoted merit-based advancement by decoupling authority from birthright, allowing Genghis Khan to integrate conquered peoples and low-status Mongols into administrative and military roles based on demonstrated loyalty and competence rather than aristocratic lineage.[87] This meritocratic principle was evident in the reorganization of the army into decimal units—arban (10 men), jaghun (100), mingghan (1,000), and tumen (10,000)—drawn from multiple tribes to erode kinship-based factions and reward skill in combat and logistics.[88] Prominent examples include Subutai, born to a blacksmith family with no noble heritage, who rose to command over 65,000 troops and led campaigns from China to Hungary by 1241 due to tactical brilliance; and Jebe, a former enemy warrior adopted for marksmanship prowess, who directed invasions into Central Asia.[87] Such promotions extended to non-Mongols, like Chinese engineers integrated for siege technology, fostering an empire where administrative posts in conquered regions were allocated by ability to extract tribute and maintain stability, rather than ethnic or familial ties. This system of meritocracy, underpinned by Yassa mandates against nepotism and corruption, contributed causally to the Mongols' administrative efficiency and military adaptability, enabling governance over heterogeneous populations from 1206 onward without reliance on feudal hierarchies prevalent in contemporaneous empires like the Song Dynasty or Khwarezm.[83] However, its harsh enforcement—exemplified by the execution of elites for favoritism—reflected pragmatic realism in binding a fractious steppe society, though later successors like Ögedei occasionally deviated by favoring kin, diluting its purity.[82] Primary Persian and Arabic chronicles, such as those by Juvayni and Rashid al-Din, describe these mechanisms as instrumental in sustaining conquest momentum, though their accounts may idealize the Yassa to underscore Mongol legitimacy.[84]Tolerance Policies and Multiethnic Rule

The Mongol Empire's tolerance policies, codified in Genghis Khan's Yassa, emphasized religious freedom to foster stability and loyalty across diverse populations, prohibiting forced conversions and allowing open practice of shamanism, Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, and other faiths.[89] This approach reflected pragmatic governance rather than ideological commitment, as the nomadic Mongols, rooted in Tengrism, viewed foreign religions with benign neglect to avoid unrest that could disrupt tax collection and military conscription.[90] Clergy from various traditions received exemptions from military service and reduced taxation—such as qubchur levies—in exchange for prayers and administrative support, though violations of imperial law invited severe penalties regardless of religious status.[86] Under successors like Ögedei and Möngke, these policies extended to public religious debates and state patronage, including the construction of mosques, temples, and churches; for example, in China, Mongol rulers supported Islamic institutions while employing Nestorian Christians as envoys.[91] In Persia and the Ilkhanate, Hülegü Khan's administration tolerated Zoroastrian and Jewish officials, drawing on local expertise without imposing Mongol spiritual practices.[89] Such tolerance contrasted with contemporaneous empires like the Abbasids, where sectarian favoritism often prevailed, enabling the Mongols to integrate conquered elites who might otherwise resist.[92] Multiethnic rule complemented these policies through a merit-based bureaucracy that prioritized skill and loyalty over ethnic or tribal origin, allowing non-Mongols to ascend to high offices and counterbalance steppe aristocracy.[93] Genghis Khan's reorganization demoted hereditary nobles in favor of proven competence, incorporating Uighur scribes for their phonetic script adapted to Mongolian administration and Chinese accountants for fiscal precision.[94] In western conquests, Persian administrators like the vizier Rashid al-Din under Ghazan Khan managed tax systems and diplomacy, while Central Asian Muslims handled engineering in China under Kublai Khan, who appointed figures such as the Venetian Marco Polo to oversee trade.[93] This system deployed darughachi overseers from varied backgrounds to monitor provinces, ensuring accountability via the yam relay network, though it occasionally bred corruption among local intermediaries.[95] By leveraging ethnic diversity, the Mongols achieved administrative efficiency over 24 million square kilometers, with non-Mongol officials comprising up to 80% of bureaucratic roles in regions like the Yuan dynasty, where Semu ("various categories") peoples from Persia and Central Asia filled key posts.[93] Such integration mitigated ethnic tensions post-conquest, as seen in the Ilkhanate's reliance on Persian governors for revenue extraction, but required vigilant enforcement of the Yassa to prevent factionalism.[96] This meritocratic ethos, absent rigid Confucian exams initially, enabled rapid adaptation but waned under later khans favoring Mongol kin, contributing to fragmentation by the 14th century.[56]Infrastructure and Communication Networks

The Mongol Empire's Yam (or örtöö) system represented a pioneering postal relay network designed for efficient communication and logistics across Eurasia. Initiated by Genghis Khan around 1206 and formalized under Ögedei Khan following the 1229 kurultai, it featured stations spaced 20 to 40 miles apart, each equipped with fresh horses, fodder, guards, and provisions to support official couriers, envoys, and military dispatches.[97][98] Messengers utilized this infrastructure to traverse up to 200 miles per day by relay, enabling the empire to coordinate distant campaigns and governance with unprecedented speed; for instance, orders from Karakorum could reach frontier outposts in weeks rather than months.[99][35] To sustain the Yam, the Mongols invested in complementary infrastructure, including the repair and extension of overland routes that linked existing Silk Road paths with new highways. These efforts incorporated engineered bridges—such as pontoon crossings over rivers—and waystations with fortified enclosures, reducing travel hazards and supporting the Pax Mongolica's secure commerce.[87] In conquered territories like Khwarezm and northern China, local labor was mobilized to dredge canals and construct ferries, enhancing connectivity for grain transport and troop movements, though such projects prioritized military utility over civilian welfare.[97] The system's maintenance relied on a tax in kind from subject populations, funding up to 50 horses per station in high-traffic areas, which underscored the empire's merit-based administration in enforcing reliability.[100] This network not only amplified Mongol conquests by accelerating intelligence flows—critical in battles like the 1211 invasion of Jin—but also laid precedents for later Eurasian postal services, persisting in diluted forms under successors like the Yuan dynasty until the 14th century.[98][35]Consequences and Long-Term Effects

Demographic Disruptions and Genetic Traces

The Mongol invasions of the 13th century inflicted severe demographic shocks across Eurasia, with regional population declines estimated at 20-50% in heavily affected areas such as Persia and Central Asia, driven by direct warfare, massacres, famine, and disease.[101] In Khwarezmia, cities like Merv and Nishapur saw near-total depopulation following sieges in 1220-1221, where contemporary accounts report hundreds of thousands slain, corroborated by archaeological evidence of abandoned urban sites and reduced settlement density persisting for generations.[101] Similarly, the 1258 sack of Baghdad reduced Iraq's urban population from an estimated 1 million to under 250,000, exacerbating long-term stagnation through destruction of irrigation systems and agricultural collapse.[101] These disruptions facilitated nomadic influxes and ethnic shifts, with Turkic and Mongol pastoralists repopulating depopulated farmlands, altering settlement patterns that endured into the 14th century.[102] In China, the conquests from 1206-1279 contributed to population fluctuations, with northern regions experiencing localized declines of up to 30% amid prolonged warfare, though overall census figures rebounded under Yuan administration due to migration and recovery policies.[103] Eastern Europe and the Rus' principalities faced intermittent raids culminating in the 1237-1242 invasions, which halved populations in Kievan Rus' through killings and enslavement, prompting shifts toward fortified principalities and Slavic-Tatar admixture.[104] These events not only reduced carrying capacity—evidenced by reforestation and proxy climate data indicating temporary cooling from reduced emissions—but also reshaped labor demographics, with forced resettlements and tribute systems redistributing survivors.[101] Genetic studies reveal enduring paternal traces of Mongol expansion, primarily through the Y-chromosome haplogroup C2b1a1b1 (formerly C3*), originating in Mongolia around 1000 CE and radiating during conquests via elite reproductive success and coercive admixture.[105] This lineage, linked to Genghis Khan's patriline, appears in approximately 8% of males across a swath from northeast Asia to the Middle East, affecting an estimated 16 million contemporary men, with higher frequencies (up to 24%) in Mongolia and adjacent populations reflecting harem systems and survivor male biases.[105] In conquered regions like Kazakhstan and Persia, medieval Mongol markers constitute 10-20% of local Y-lineages, indicating male-mediated gene flow amid female continuity, while fainter signals (1-2%) extend to Russia and Anatolia, underscoring asymmetric demographic violence.[106] These traces diminish westward and southward, absent in uninvaded areas like Japan, confirming conquest-driven dispersal over voluntary migration.[107]Economic Revitalization via Pax Mongolica

The Pax Mongolica, spanning roughly the 13th and 14th centuries, refers to a period of relative political stability and security across the vast Mongol domains, which enabled the revitalization of long-distance trade networks disrupted by prior warfare and fragmentation.[108] This era, peaking from approximately 1280 to 1360, saw the Mongol administration suppress banditry and enforce safe passage along trade routes stretching from China to Eastern Europe, fostering a unified economic sphere.[109] By establishing relay stations known as yam, spaced 25 to 40 miles apart, the Mongols created an efficient communication and logistics system that merchants could utilize for rapid transit and information exchange, significantly reducing travel risks and times.[110] Mongol policies directly promoted commerce through standardization of weights, measures, and legal protections for traders, including exemptions from certain taxes and harsh penalties for route disruptions, which lowered transaction costs and encouraged participation from diverse ethnic merchants.[87] In the Yuan dynasty under Kublai Khan (r. 1260–1294), the introduction of paper currency and uniform tariffs further integrated markets, reviving the Silk Road's function as a conduit for goods like Chinese silk, porcelain, and spices eastward to westward-bound items such as European woolens, amber, and furs.[87] Trade volumes surged as a result, with cities like Tabriz in Persia and Samarkand in Central Asia emerging as bustling hubs where annual caravans carried commodities valued in the millions of dinars, stimulating local economies through taxation and ancillary services.[111] This economic integration not only boosted prosperity in conquered regions—evident in the rise of a privileged merchant class under Mongol patronage—but also facilitated the diffusion of technologies and agricultural techniques, such as improved irrigation in Persia, contributing to post-conquest recovery and growth rates estimated at 20-30% in trade-related sectors by the early 14th century.[110][87] However, the system's reliance on centralized Mongol authority meant that fragmentation after 1368, coupled with the Black Death's spread along these same routes, eventually undermined the Pax, though its legacy endured in heightened Eurasian interconnectivity.[112]Technological Transfers and Cultural Exchanges

The Pax Mongolica, the period of relative stability enforced by Mongol rule from approximately 1241 to 1368, enabled unprecedented technological and cultural diffusion across Eurasia by securing trade routes like the Silk Road and promoting the movement of artisans, scholars, and merchants under policies of religious tolerance and merit-based administration.[108][113] This era facilitated bidirectional exchanges, with Chinese innovations traveling westward while Persian and Islamic knowledge influenced Mongol-held territories in the East.[114] Militarily, the Mongols accelerated the spread of gunpowder technology after adopting it during the conquest of northern China in the 1230s, integrating Chinese fire lances, bombs, and early cannons into their siege warfare.[115] By the 1240s, these weapons appeared in campaigns against Eastern Europe and the Middle East, such as the use of explosive projectiles during the 1258 sack of Baghdad, exposing Persian engineers to Chinese-derived incendiaries and contributing to the evolution of gunpowder arms in the Islamic world.[116] The empire's integration of captured specialists further disseminated related techniques, including composite bow designs and stirrup innovations, which enhanced cavalry effectiveness across conquered regions.[30] Civilian technologies also proliferated, with Chinese paper-making, printing methods, and paper currency introduced to Persian administration under the Ilkhanate by the mid-13th century, streamlining bureaucratic records and trade documentation.[114] The compass, refined in Song China, reached Persian and European traders via Mongol networks, aiding navigation despite the empire's limited maritime focus.[117] In the opposite direction, Islamic advancements in optics and alchemy influenced Yuan dynasty scholars, as evidenced by the relocation of Persian craftsmen to China following the 1258 conquests.[118] Culturally, Mongol patronage of artisans—exempting them from taxes and conscription—fostered cross-regional collaborations, such as the blending of Chinese porcelain techniques with Persian ceramics in the 14th-century Ilkhanate workshops.[118] Religious exchanges thrived under shamanistic tolerance, enabling the revival of Nestorian Christianity across Central Asia and the transmission of Tibetan Buddhism from China to Mongolia by the 1250s.[113] Scholarly migrations, including Chinese astronomers and physicians to the Persian court of Hulagu Khan after 1256, produced hybrid works like revised calendars integrating Islamic and Chinese observations, though the depth of mutual influence varied by region and was often pragmatic rather than ideological.[114] These interactions, while opportunistic, laid groundwork for later Eurasian scientific convergences, distinct from the era's predominant military disruptions.[108]Evaluations and Controversies

Reassessed Death Toll Estimates