Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Timpani

View on Wikipedia

A timpanist | |

| Percussion instrument | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Kettledrums, Timps, Pauken |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 211.11-922 (Struck membranophone with membrane lapped on by a rim) |

| Developed | at least c. 6th century AD |

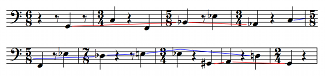

| Playing range | |

Ranges of individual sizes[1]  | |

| Related instruments | |

| Sound sample | |

|

| |

The timpani (/ˈtɪmpəni/;[2] Italian pronunciation: [ˈtimpani]) or kettledrums (also informally called timps)[2] are musical instruments in the percussion family. A type of drum categorised as a hemispherical drum, they consist of a membrane called a head stretched over a large bowl traditionally made of copper. Thus timpani are an example of kettledrums, also known as vessel drums and semispherical drums, whose body is similar to a section of a sphere whose cut conforms the head. Most modern timpani are pedal timpani and can be tuned quickly and accurately to specific pitches by skilled players through the use of a movable foot-pedal. They are played by striking the head with a specialized beater called a timpani stick or timpani mallet. Timpani evolved from military drums to become a staple of the classical orchestra by the last third of the 18th century. Today, they are used in many types of ensembles, including concert bands, marching bands, orchestras, and even in some rock bands.

Timpani is an Italian plural, the singular of which is timpano, though the singular may also be referred to as a timpanum. In English the term timpano is only widely in use by practitioners: a single drum is often referred to as a timpani, leading many to incorrectly pluralize the word as timpanis. A musician who plays timpani is a timpanist.

Etymology and alternative spellings

[edit]First attested in English in the late 19th century, the Italian word timpani derives from the Latin tympanum (pl. tympana), which is the latinisation of the Greek word τύμπανον (tumpanon, pl. tumpana), 'a hand drum',[3] which in turn derives from the verb τύπτω (tuptō), meaning 'to strike, to hit'.[4] Alternative spellings with y in place of either or both i's—tympani, tympany, or timpany—are occasionally encountered in older English texts.[5] Although the word timpani has been widely adopted in the English language, some English speakers choose to use the word kettledrums.[6] The German word for timpani is Pauken; the Swedish word is pukor in plural (from the word puka), the French and Spanish is timbales, not to be confused with the latin percussion instrument, which would actually supersede the timpani in the traditional Cuban ensemble known as Charanga.[7]

The tympanum is mentioned, along with a faux name origin, in the Etymologiae of St. Isidore of Seville:

Tympanum est pellis vel corium ligno ex una parte extentum. Est enim pars media symphoniae in similitudinem cribri. Tympanum autem dictum quod medium est, unde et margaritum medium tympanum dicitur; et ipsud ut symphonia ad virgulam percutitur.[8]

The tympanum is a skin or hide stretched over one end of a wooden frame. It is half of a symphonia (i.e. another type of drum) and it looks like a sieve. The tympanum is so named because it is a half, whence also the half-pearl is called a tympanum. Like the symphonia, it is struck with a drumstick.[9]

The reference comparing the tympanum to half a pearl is borrowed from Pliny the Elder.[10]

Construction

[edit]Basic timpani

[edit]The basic timpano consists of a drum head stretched across the opening of a bowl typically made of copper[11] or, in less expensive models, fiberglass or aluminum. In the Sachs–Hornbostel classification, this makes timpani membranophones. The head is affixed to a hoop (also called a flesh hoop),[6][12] which in turn is held onto the bowl by a counter hoop.[6][13] The counter hoop is usually held in place with a number of tuning screws called tension rods placed regularly around the circumference. The head's tension can be adjusted by loosening or tightening the rods. Most timpani have six to eight tension rods.[11]

The shape and material of the bowl's surface help to determine the drum's timbre. For example, hemispheric bowls produce brighter tones while parabolic bowls produce darker tones.[14] Modern timpani are generally made with copper due to its efficient regulation of internal and external temperatures relative to aluminum and fiberglass.[15]

Timpani come in a variety of sizes from about 33 inches (84 cm) in diameter down to piccoli timpani of 12 inches (30 cm) or less.[6] A 33-inch drum can produce C2 (the C below the bass clef), and specialty piccoli timpani can play up into the treble clef. In Darius Milhaud's 1923 ballet score La création du monde, the timpanist must play F♯4 (at the bottom of the treble clef).

Each drum typically has a range of a perfect fifth, or seven semitones.[6]

Machine timpani

[edit]Changing the pitch of a timpani by turning each tension rod individually is a laborious process. In the late 19th century, mechanical systems to change the tension of the entire head at once were developed. Any timpani equipped with such a system may be considered machine timpani, although this term commonly refers to drums that use a handle connected to a spider-type tuning mechanism.[11]

Pedal timpani

[edit]By far the most common type of timpani used today are pedal timpani, which allows the tension of the head to be adjusted using a pedal mechanism. Typically, the pedal is connected to the tension screws via an assembly of either cast metal or metal rods called the spider.

There are three types of pedal mechanisms in common use today:

- The ratchet clutch system uses a ratchet and pawl to hold the pedal in place. The timpanist must first disengage the clutch before using the pedal to tune the drum. When the desired pitch is achieved, the timpanist must then reengage the clutch. Because the ratchet engages in only a fixed set of positions, the timpanist must fine-tune the drum by means of a fine-tuning handle.

- In the balanced action system, a spring or hydraulic cylinder is used to balance the tension on the head so the pedal will stay in position and the head will stay at pitch. The pedal on a balanced action drum is sometimes called a floating pedal since there is no clutch holding it in place.

- The friction clutch or post and clutch system uses a clutch that moves along a post. Disengaging the clutch frees it from the post, allowing the pedal to move without restraint.

Professional-level timpani use either the ratchet or friction system and have copper bowls. These drums can have one of two styles of pedals. The Dresden pedal is attached at the side nearest the timpanist and is operated by ankle motion. A Berlin-style pedal is attached by means of a long arm to the opposite side of the timpani, and the timpanist must use their entire leg to adjust the pitch. In addition to a pedal, high-end instruments have a hand-operated fine-tuner, which allows the timpanist to make minute pitch adjustments. The pedal is on either the left or right side of the drum depending on the direction of the setup.

Most school bands and orchestras below a university level use less expensive, more durable timpani with copper, fiberglass, or aluminum bowls. The mechanical parts of these instruments are almost completely contained within the frame and bowl. They may use any of the pedal mechanisms, though the balanced action system is by far the most common, followed by the friction clutch system. Many professionals also use these drums for outdoor performances due to their durability and lighter weight. The pedal is in the center of the drum itself.

Chain timpani

[edit]

On chain timpani, the tension rods are connected by a roller chain much like the one found on a bicycle, though some manufacturers have used other materials, including steel cable. In these systems, all the tension screws can then be tightened or loosened by one handle. Though far less common than pedal timpani, chain and cable drums still have practical uses. Occasionally, a timpanist is forced to place a drum behind other items, so he cannot reach it with his foot. Professionals may also use exceptionally large or small chain and cable drums for special low or high notes.

Other tuning mechanisms

[edit]A rare tuning mechanism allows the pitch to be changed by rotating the drum itself. A similar system is used on rototoms. Jenco, a company better known for mallet percussion, made timpani tuned in this fashion.

In the early 20th century, Hans Schnellar, the timpanist of the Vienna Philharmonic, developed a tuning mechanism in which the bowl is moved via a handle that connects to the base and the head remains stationary. These instruments are referred to as Viennese timpani (Wiener Pauken) or Schnellar timpani.[16] Adams Musical Instruments developed a pedal-operated version of this tuning mechanism in the early 21st century.

Heads

[edit]Like most drumheads, timpani heads can be made from two materials: animal skin (typically calfskin or goatskin)[6] or plastic (typically PET film). Plastic heads are durable, weather-resistant, and relatively inexpensive. Thus, they are more commonly used than skin heads. However, many professional timpanists prefer skin heads because they produce a "warmer" timbre. Timpani heads are determined based on the size of the head, not the bowl. For example, a 23-inch (58 cm) drum may require a 25-inch (64 cm) head. This 2-inch (5 cm) size difference has been standardized by most timpani manufacturers since 1978.[17]

Sticks and mallets

[edit]

Timpani are typically struck with a special type of drum stick called a timpani stick or timpani mallet. Timpani sticks are used in pairs. They have two components: a shaft and a head. The shaft is typically made from hardwood or bamboo but may also be made from aluminum or carbon fiber. The head can be constructed from a number of different materials, though felt wrapped around a wooden core is the most common. Other core materials include compressed felt, cork, and leather.[18] Unwrapped sticks with heads of wood, felt, flannel, and leather are also common.[6] Wooden sticks are used as a special effect[19]—specifically requested by composers as early as the Romantic era—and in authentic performances of Baroque music. Wooden timpani sticks are also occasionally used to play the suspended cymbal.

Although not usually stated in the score (excepting the occasional request to use wooden sticks), timpanists will change sticks to suit the nature of the music. However, the choice during a performance is subjective and depends on the timpanist's preference and occasionally the wishes of the conductor. Thus, most timpanists own a great number of sticks.[6] The weight of the stick, size and latent surface area of the head, materials used for the shaft, core, and wrap, and method used to wrap the head all contribute to the timbre the stick produces.[20]

In the early 20th century and before, sticks were often made with whalebone shafts, wooden cores, and sponge wraps. Composers of that era often specified sponge-headed sticks. Modern timpanists execute such passages with felt sticks.

Popular grips

[edit]The two most common grips in playing the timpani are the German and French grips. In the German grip, the palm of the hand is approximately parallel with the drum head and the thumb should be on the side of the stick. In the French grip, the palm of the hand is approximately perpendicular with drum head and the thumb is on top of the stick. In both of these styles, the fulcrum is the contact between the thumb and middle finger. The index finger is used as a guide and to help lift the stick off of the drum.[21] The American grip is a hybrid of these two grips. Another known grip is known as the Amsterdam Grip, made famous by the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, which is similar to the Hinger grip, except the stick is cradled on the lower knuckle of the index finger.

In the modern ensemble

[edit]

Standard set

[edit]A standard set of timpani (sometimes called a console) consists of four drums: roughly 81 centimetres (32 in), 74 centimetres (29 in), 66 centimetres (26 in), and 58 centimetres (23 in) in diameter.[22] The range of this set is roughly D2 to A3. A great majority of the orchestral repertoire can be played using these four drums. However, contemporary composers have written for extended ranges. Igor Stravinsky specifically writes for a piccolo timpano in The Rite of Spring, tuned to B3. A piccolo drum is typically 51 centimetres (20 in) in diameter and can reach pitches up to C4.

Beyond this extended set of five instruments, any added drums are nonstandard. (Luigi Nono's Al gran sole carico d'amore requires as many as eleven drums, with actual melodies played on them in octaves by two players.) Many professional orchestras and timpanists own more than just one set of timpani, allowing them to execute music that cannot be more accurately performed using a standard set of four or five drums. Many schools and youth orchestra ensembles unable to afford purchase of this equipment regularly rely on a set of two or three timpani, sometimes referred to as "the orchestral three".[6] It consists of 74-centimetre (29 in), 66-centimetre (26 in), and 58-centimetre (23 in) drums. Its range extends down only to F2.

The drums are set up in an arc around the performer. Traditionally, North American, British, and French timpanists set their drums up with the lowest drum on the left and the highest on the right (commonly called the American system), while German, Austrian, and Greek players set them up in the reverse order, as to resemble a drum set or upright bass (the German system).[6] This distinction is not strict, as many North American players use the German setup and vice versa.

Players

[edit]

Throughout their education, timpanists are trained as percussionists, and they learn to play all instruments of the percussion family along with timpani. However, when appointed to a principal timpani chair in a professional ensemble, a timpanist is not normally required to play any other instruments. In his book Anatomy of the Orchestra, Norman Del Mar writes that the timpanist is "king of his own province", and that "a good timpanist really does set the standard of the whole orchestra." A qualified member of the percussion section sometimes doubles as associate timpanist, performing in repertoire requiring multiple timpanists and filling in for the principal timpanist when required.

Among the professionals who have been highly regarded for their virtuosity and impact on the development of the timpani in the 20th century are Saul Goodman, Hans Schnellar, Fred Hinger, Tom Freer, and Cloyd Duff.[23][24][25]

Concertos

[edit]A few solo concertos have been written for timpani, and are for timpani and orchestral accompaniment. The 18th-century composer Johann Fischer wrote a symphony for eight timpani and orchestra, which requires the solo timpanist to play eight drums simultaneously. Rough contemporaries Georg Druschetzky and Johann Melchior Molter also wrote pieces for timpani and orchestra. Throughout the 19th century and much of the 20th, there were few new timpani concertos. In 1983, William Kraft, principal timpanist of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, composed his Concerto for Timpani and Orchestra, which won second prize in the Kennedy Center Friedheim Awards. There have been other timpani concertos, notably, Philip Glass, considered one of the most influential composers of the late 20th century,[26] wrote a double concerto at the behest of soloist Jonathan Haas titled Concerto Fantasy for Two Timpanists and Orchestra, which features its soloists playing nine drums a piece.[27]

Performance techniques

[edit]Striking

[edit]For general playing, a timpanist will beat the head approximately 4 inches (10 cm) in from the edge.[22] Beating at this spot produces the round, resonant sound commonly associated with timpani. A timpani roll (most commonly signaled in a score by tr or three slashes) is executed by striking the timpani at varying velocities; the speed of the strokes are determined by the pitch of the drum, with higher pitched timpani requiring a quicker roll than timpani tuned to a lower pitch. While performing the timpani roll, mallets are usually held a few inches apart to create more sustain.[28] Anton Bruckner's Symphony No. 7 requires a continuous roll on a drum for over two and a half minutes. In general, timpanists do not use multiple bounce rolls like those played on the snare drum, as the soft nature of timpani sticks causes the rebound of the stick to be reduced, causing multiple bounce rolls to sound muffled.[6] However, when playing with wood mallets, timpanists sometimes use multiple bounce rolls.[29]

The tone quality can be altered without switching sticks or adjusting the tuning. For example, by playing closer to the edge, the sound becomes thinner.[6] A more staccato sound can be produced by changing the velocity of the stroke or playing closer to the center.[28]

Tuning

[edit]Prior to playing, the timpanist must clear the heads by equalizing the tension at each tuning screw. This is done so every spot is tuned to exactly the same pitch. When the head is clear, the timpani will produce an in-tune sound. If the head is not clear, the pitch will rise or fall after the initial impact of a stroke, and the drum will produce different pitches at different dynamic levels. Timpanists are required to have a well-developed sense of relative pitch and must develop techniques to tune in an undetectable manner and accurately in the middle of a performance. Tuning is often tested with a light tap from a finger, which produces a near-silent note.

Some timpani are equipped with tuning gauges, which provide a visual indication of the pitch. They are physically connected either to the counterhoop, in which case the gauge indicates how far the counterhoop is pushed down, or the pedal, in which case the gauge indicates the position of the pedal. These gauges are accurate when used correctly. However, when the instrument is disturbed in some fashion (transported, for example), the overall pitch can change, thus the markers on the gauges may not remain reliable unless they have been adjusted immediately preceding the performance. The pitch can also be changed by room temperature and humidity. This effect also occurs due to changes in weather, especially if an outdoor performance is to take place. Gauges are especially useful when performing music that involves fast tuning changes that do not allow the timpanist to listen to the new pitch before playing it. Even when gauges are available, good timpanists will check their intonation by ear before playing. Occasionally, timpanists use the pedals to retune while playing.

Portamento effects can be achieved by changing the pitch while it can still be heard. This is commonly called a glissando, though this use of the term is not strictly correct. The most effective glissandos are those from low to high notes and those performed during rolls. One of the first composers to call for a timpani glissando was Carl Nielsen, who used two sets of timpani playing glissandos at the same time in his Symphony No. 4 ("The Inextinguishable").

Pedaling refers to changing the pitch with the pedal; it is an alternate term for tuning. In general, timpanists reserve this term for passages where they must change the pitch in the midst of playing. Early 20th-century composers such as Nielsen, Béla Bartók, Samuel Barber, and Richard Strauss took advantage of the freedom that pedal timpani afforded, often giving the timpani the bass line.

Muffling

[edit]Since timpani have a long sustain, muffling or damping is an inherent part of playing. Often, timpanists will muffle notes so they only sound for the length indicated by the composer. However, early timpani did not resonate nearly as long as modern timpani, so composers often wrote a note when the timpanist was to hit the drum without concern for sustain. Today, timpanists must use their ear and the score to determine the length the note should sound.

The typical method of muffling is to place the pads of the fingers against the head while holding onto the timpani stick with the thumb and index finger. Timpanists are required to develop techniques to stop all vibration without making any sound from the contact of their fingers.[22]

Muffling is often referred to as muting, which can also refer to playing with mutes on them (see below).

Extended techniques

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2021) |

It is typical for only one timpani to be struck at a time, but occasionally composers will ask for two notes. This is called a double stop, a term borrowed from the string instrument vocabulary. Ludwig van Beethoven uses this effect in the slow third movement of his Ninth Symphony, as do Johannes Brahms in the second movement of his German Requiem and Aaron Copland in El Salón México. Some modern composers occasionally require more than two notes. In this case, a timpanist can hold two sticks in one hand much like a marimbist, or more than one timpanist can be employed. In his Overture to Benvenuto Cellini, for example, Hector Berlioz realizes fully voiced chords from the timpani by requiring three timpanists and assigning one drum to each. He goes as far as ten timpanists playing three- and four-part chords on sixteen drums in his Requiem, although with the introduction of pedal tuning, this number can be reduced.

Modern composers will often specify the beating spot to alter the sound of the drum. When the timpani are struck directly in the center, they have a sound that is almost completely devoid of tone and resonance. George Gershwin uses this effect in An American in Paris. Struck close to the edge, timpani produce a very thin, hollow sound. This effect is used by composers such as Bartók, Bernstein, and Kodály.

A variation of this is to strike the head while two fingers of one hand lightly press and release spots near the center. The head will then vibrate at a harmonic much like the similar effect on a string instrument.

Resonance can cause timpani not in use to vibrate, causing a quieter sound to be produced. Timpanists must normally avoid this effect, called sympathetic resonance, but composers have exploited it in solo pieces such as Elliott Carter's Eight Pieces for Four Timpani. Resonance is reduced by damping or muting the drums, and in some cases composers will specify that timpani be played con sordino (with mute) or coperti (covered), both of which indicate that mutes – typically small pieces of felt or leather – should be placed on the head.

Composers will sometimes specify that the timpani should be struck with implements other than timpani sticks. It is common in timpani etudes and solos for timpanists to play with their hands or fingers. Philip Glass's Concerto Fantasy utilizes this technique during a timpani cadenza. Also, Michael Daugherty's Raise The Roof calls for this technique to be used for a certain passage. Leonard Bernstein calls for maracas on timpani in his Symphony No. 1 Jeremiah and in his Symphonic Dances from West Side Story suite. Edward Elgar attempts to use the timpani to imitate the engine of an ocean liner in his Enigma Variations by requesting the timpanist play a soft roll with snare drum sticks. However, snare drum sticks tend to produce too loud a sound, and since this work's premiere, the passage has been performed by striking with coins. Benjamin Britten asks for the timpanist to use drumsticks in his War Requiem to evoke the sound of a field drum.

Robert W. Smith's Songs of Sailor and Sea calls for a "whale sound" on the timpani. This is achieved by moistening the thumb and rubbing it from the edge to the center of the head. Among other techniques used primarily in solo work, such as John Beck's Sonata for Timpani, is striking the bowls. Timpanists tend to be reluctant to strike the bowls at loud levels or with hard sticks since copper can be dented easily due to its soft nature.

On some occasions a composer may ask for a metal object, commonly an upside-down cymbal, to be placed upon the head and then struck or rolled while executing a glissando on the drum. Joseph Schwantner uses this technique in From A Dark Millennium. Carl Orff asks for cymbals resting on the head while the drum is struck in his later works. Additionally, Michael Daugherty utilizes this technique in his concerto Raise The Roof. In his piece From me flows what you call Time, Tōru Takemitsu calls for Japanese temple bowls to be placed on timpani.[30]

History

[edit]

Pre-orchestral history

[edit]The first recorded use of early Tympanum was in "ancient times when it is known that they were used in religious ceremonies by Hebrews."[22] The Moon of Pejeng, also known as the Pejeng Moon,[31] in Bali, the largest single-cast bronze kettledrum in the world,[32] is more than two thousand years old.[33] The Moon of Pejeng is "the largest known relic from Southeast Asia's Bronze Age period."[34] The drum is in the Pura Penataran Sasih temple."[35]

In 1188, Cambro-Norman chronicler Gerald of Wales wrote, "Ireland uses and delights in two instruments only, the harp namely, and the tympanum."[36]

Arabian nakers, the direct ancestors of most timpani, were brought to 13th-century Continental Europe by Crusaders and Saracens.[11] These drums, which were small (with a diameter of about 8 to 8+1⁄2 inches (20–22 cm)) and mounted to the player's belt, were used primarily for military ceremonies. This form of timpani remained in use until the 16th century. In 1457, a Hungarian legation sent by King Ladislaus V carried larger timpani mounted on horseback to the court of King Charles VII in France. This variety of timpani had been used in the Middle East since the 12th century. These drums evolved together with trumpets to be the primary instruments of the cavalry. This practice continues to this day in sections of the British Army, and timpani continued to be paired with trumpets when they entered the classical orchestra.[37]

The medieval European timpani were typically put together by hand in the southern region of France. Some drums were tightened together by horses tugging from each side of the drum by the bolts. Over the next two centuries, a number of technical improvements were made to the timpani. Originally, the head was nailed directly to the shell of the drum. In the 15th century, heads began to be attached and tensioned by a counterhoop tied directly to the shell. In the early 16th century, the bindings were replaced by screws. This allowed timpani to become tunable instruments of definite pitch.[6] The Industrial Revolution enabled the introduction of new construction techniques and materials, in particular machine and pedal tuning mechanisms. Plastic heads were introduced in the mid-20th century, led by Remo.[38]

Role in orchestra

[edit]"No written kettledrum music survives from the 16th century, because the technique and repertory were learned by oral tradition and were kept secret. An early example of trumpet and kettledrum music occurs at the beginning of Claudio Monteverdi's opera L'Orfeo (1607)."[39] Later in the Baroque era, Johann Sebastian Bach wrote a secular cantata titled Tönet, ihr Pauken! Erschallet, Trompeten!, which translates roughly to "Sound off, ye timpani! Sound, trumpets!" Naturally, the timpani are placed at the forefront: the piece starts with an unusual timpani solo and the chorus and timpani trade the melody back and forth. Bach reworked this movement in Part I of the Christmas Oratorio.

Mozart and Haydn wrote many works for the timpani and even started putting it in their symphonies and other orchestral works.

Ludwig van Beethoven revolutionized timpani music in the early 19th century. He not only wrote for drums tuned to intervals other than a fourth or fifth, but he gave a prominence to the instrument as an independent voice beyond programmatic use. For example, his Violin Concerto (1806) opens with four solo timpani strokes, and the scherzo of his Ninth Symphony (1824) sets the timpani (tuned an octave apart) against the orchestra in a sort of call and response.[40]

The next major innovator was Hector Berlioz. He was the first composer to indicate the exact sticks that should be used—"felt-covered", "wooden", etc. In several of his works, including Symphonie fantastique (1830), and his Requiem (1837), he demanded the use of several timpanists at once.[22]

Until the late 19th century, timpani were hand-tuned; that is, there was a sequence of screws with T-shaped handles, called taps, which altered the tension in the head when turned by players. Thus, tuning was a relatively slow operation, and composers had to allow a reasonable amount of time for players to change notes if they were called to tune in the middle of a work. The first 'machine' timpani, with a single tuning handle, was developed in 1812.[41] The first pedal timpani originated in Dresden in the 1870s and are called Dresden timpani for this reason.[11] However, since vellum was used for the heads of the drums, automated solutions were difficult to implement since the tension would vary unpredictably across the drum. This could be compensated for by hand-tuning, but not easily by a pedal drum. Mechanisms continued to improve in the early 20th century.

Despite these problems, composers eagerly exploited the opportunities the new mechanism had to offer. By 1915, Carl Nielsen was demanding glissandos on timpani in his Fourth Symphony—impossible on the old hand-tuned drums. However, it took Béla Bartók to more fully realize the flexibility the new mechanism had to offer. Many of his timpani parts require such a range of notes that it would be unthinkable to attempt them without pedal drums.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, timpani were almost always tuned with the dominant note of the piece on the low drum and the tonic on the high drum—a perfect fourth apart. Until the early 19th century the dominant (the note of the large drum) was written as G and the tonic (the note of the small drum) was written as C no matter what the actual key of the work was, and whether it was major or minor, with the actual pitches indicated at the top of the score (for example, Timpani in D–A for a work in D major or D minor).[11] This notation style however was not universal: Bach, Mozart, and Schubert (in his early works) used it, but their respective contemporaries Handel, Haydn, and Beethoven wrote for the timpani at concert pitch.[42]

In the 2010s, even though they are written at concert pitch, timpani parts continue to be most often[43] but not always[44] written with no key signature, no matter what key the work is in: accidentals are written in the staff, both in the timpanist's part and the conductor's score. By 1977 in Vienna, Alexander Rahbari, an outstanding Iranian-Austrian composer and conductor, commenced the concert with one of his own compositions, entitled Persian Mysticism Around G, which starts with a short introduction written for timpani (five timpani tuned in B♭-C-D-E♭-G). After a few bars fomenting the primary stormy passage, he uses an effective glissando effect produced by the back and forth switching of the timpani pedals, moving from B♭ up to C and then rolling down back to G (You can see the glissando notation and also listen to the whole timpani introduction on the right).[45] Rahbari also makes use of a series of acciaccatura during this opening section.

Outside the orchestra

[edit]

Later, timpani were adopted into other classical music ensembles such as concert bands. In the 1970s, marching bands and drum and bugle corps, which evolved both from traditional marching bands and concert bands, began to include marching timpani. Unlike concert timpani, marching versions had fiberglass shells to make them light enough to carry. Each player carried a single drum, which was tuned by a hand crank. Often, during intricate passages, the timpani players would put their drums on the ground by means of extendable legs, and perform more like conventional timpani, yet with a single player per drum. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, marching arts-based organizations' allowance for timpani and other percussion instruments to be permanently grounded became mainstream. This was the beginning of the end for marching timpani: eventually, standard concert timpani found their way onto the football field as part of the front ensemble, and marching timpani fell out of common usage. Timpani are still used by the Mounted Bands of the Household Division of the British Army[46] and of the Mounted Band of the Garde Républicaine in the French Army.

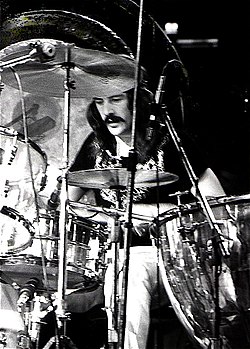

As rock and roll bands started seeking to diversify their sound, timpani found their way into the studio. In 1959 Leiber and Stoller made the innovative use of timpani in their production of the Drifters' recording, "There Goes My Baby." Starting in the 1960s, drummers for high-profile rock acts like The Beatles, Cream, Led Zeppelin, The Beach Boys, and Queen incorporated timpani into their music.[47] This led to the use of timpani in progressive rock. Emerson, Lake & Palmer recorded a number of rock covers of classical pieces that utilize timpani. Rush drummer Neil Peart added a tympani to his expanding arsenal of percussion for the Hemispheres (1978) and Permanent Waves (1980) albums and tours, and would later sample tympani in his drum solo, "The Rhythm Method" in 1988. More recently, the rock band Muse has incorporated timpani into some of their classically based songs, most notably in Exogenesis: Symphony, Part I (Overture). Jazz musicians also experimented with timpani. Sun Ra used it occasionally in his Arkestra (played, for example, by percussionist Jim Herndon on the songs "Reflection in Blue" and "El Viktor," both recorded in 1957). In 1964, Elvin Jones incorporated timpani into his drum kit on John Coltrane's four-part composition A Love Supreme. Butch Trucks, drummer with the Allman Brothers Band, made use of the timpani.

In his choral piece A Stopwatch and an Ordnance Map,[48] Samuel Barber employs three pedal timpani upon which are played glissandos.

Jonathan Haas is one of the few timpanists who markets himself as a soloist. Haas, who began his career as a solo timpanist in 1980, is notable for performing music from many genres including jazz, rock, and classical. He released an album with a rather unconventional jazz band called Johnny H. and the Prisoners of Swing. Philip Glass[49] with his Concerto Fantasy, commissioned by Haas, put two soloists in front of the orchestra, an atypical placement for the instruments. Haas also commissioned Susman's Floating Falling for timpani and cello.[50]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Samuel Z. Solomon, "How to Write for Percussion", pp. 65–66. Published by the author, 2002. ISBN 0-9744721-0-7

- ^ a b "timpani". www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com.

- ^ τύμπανον, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ τύπτω, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ "Tympani, Tympanist". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Grove, George (January 2001). Stanley Sadie (ed.). The New Grove Encyclopædia of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). Grove's Dictionaries of Music. Volume 18, pp826–837. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

- ^ Charley Gerard (2001). Music from Cuba: Mongo Santamaria, Chocolate Armenteros, and Other Stateside Cuban Musicians. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 67. ISBN 9780275966829. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- ^ Isidore of Seville, Etymologiae 3.22.10, Bill Thayer's edition of the Latin text at LacusCurtius online.

- ^ Barney, Stephen (2010). The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville. Cambridge University Press. p. 98.

- ^ Natural History IX. 35, 23. Quoted in Schlesinger, Kathleen (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 289.

- ^ a b c d e f Bridge, Robert. "Timpani Construction paper" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2016. Retrieved 18 February 2008.

- ^ "Definition of FLESH HOOP". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ^ "Definition of COUNTER HOOP". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ^ Power, Andrew (April 1983). "Sound Production of the Timpani, Part 1". Percussive Notes. 21 (4). Percussive Arts Society: 62–64.

- ^ Jones, Richard K. (March 2017). "In Search of the Missing Fundamental". The Well-Tempered Timpani. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- ^ Vibration patterns and sound analysis of the Viennese Timpani. Bertsch, Matthias. (2001), Proceedings of ISMA 2001

- ^ "Timpani Head Guide", Steve Weiss Music

- ^ Kallen, Stuart (2003). "One". The Instruments of Music. Farmington Hills, MI: Lucent Books. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-59018-127-0. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- ^ "T5 Wood". Vic Firth. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- ^ Slow Motion of Timpani Technique | Percussion Research. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- ^ Hoffman, Stewart. "Playing Timpani | Timpani Techniques | High School Percussion". stewarthoffmanmusic.com. Toronto, ON: Stewart Hoffman Music. Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Goodman, Saul (1988) [1948]. Modern Method for Tympani. Van Nuys, California: Alfred Publishing Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-7579-9100-4.

- ^ "Wiener Pauken – handmade timpani of Anton Mittermayr – timpani builder of Wiener Philharmoniker". www.wienerpauken.at.

- ^ "Percussive Arts Society Hall of Fame: Fred Hinger". Archived from the original on 18 June 2015. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ Atwood, Jim. "Percussive Arts Society Hall of Fame: Cloyd Duff". Pas.org. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ O'Mahony, John (24 November 2001), "The Guardian Profile: Philip Glass", The Guardian, London, retrieved 14 December 2015

- ^ "Concerto Fantasy for Two Timpanists and Orchestra" Archived 20 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Philip Glass Official Website

- ^ a b Jones, Brett (19 November 2013). "Percussion Performance:Timpani". School Band and Orchestra. Las Vegas, Nevada: Timeless Communications. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ "How and When to Play a Buzz Roll on Timpani". freepercussionlessons.com. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ "From me flows what you call Time". englisch. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- ^ For a thorough scholarly analysis of the Pejeng Moon and the type of drum named after it, see August Johan Bernet Kempers, "The Pejeng type," The Kettledrums of Southeast Asia: A Bronze Age World and Its Aftermath (Taylor & Francis, 1988), 327–340.

- ^ Iain Stewart and Ryan Ver Berkmoes, Bali & Lombok (Lonely Planet, 2007), 203.

- ^ Yayasan Bumi Kita and Anne Gouyon, The Natural Guide to Bali: Enjoy Nature, Meet the People, Make a Difference (Tuttle Publishing, 2005), 109.

- ^ Pringle, Robert (2004). Bali: Indonesia's Hindu Realm; A short history of. Short History of Asia Series. Allen & Unwin. pp. 28–40. ISBN 978-1-86508-863-1.

- ^ Rita A. Widiadana, "Get in touch with Bali's cultural heritage Archived 5 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine," The Jakarta Post (6 June 2002).

- ^ Topographia Hibernica, III.XI; tr. O'Meary, p. 94.

- ^ Seaman, Christopher; Richards, Michael (2013). Inside Conducting (1st ed.). Rochester: University of Rochester Press, Boydell & Brewer. pp. 149–150. ISBN 978-1-58046-411-6. JSTOR 10.7722/j.ctt3fgm4p.2.

- ^ "Company". Remo Inc. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ^ "Kettledrum; Musical Instrument". Encyclopædia Britannica. 19 August 2014.

- ^ Krentzer, Bill (December 1969). "The Beethoven Symphonies: Innovations of an Original Style in Timpani Scoring". Percussionist. 7 (2). Percussive Arts Society: 55–62.

- ^ Bowles, Edmund A. (1999). "The Impact of Technology on Musical Instruments". COSMOS Journal. Cosmos Club. Archived from the original on 12 July 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2008.

- ^ Del Mar, Norman (1981). The Anatomy of the Orchestra. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-04500-9.[page needed]

- ^ See, as an early 20th-century example, the orchestral score of Debussy's Pelléas et Mélisande: through no. 6 non-transposing parts have a key signature of one flat but the timpani part has no key signature, in bar 7 of no. 1 the timpani B♭ is written in the staff; nos. 29 to 30 non-transposing parts have a key signature of four sharps but, again, the timpani part has no key signature, and so on.

- ^ For an example where this is not done, i.e. where the timpani part carries the same signature as all the other parts, see the orchestral score of Prokofiev's Piano Concerto No. 1 in D♭ major, where, incidentally, transposing instrument parts are also written at concert pitch with the same key signature as all the other parts.

- ^ "Persian Mysticism". youtube.com. 3 February 2020. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021.

- ^ Beating Retreat page, showing image of mounted bands with timpani in 2008.

- ^ McNamee, David (27 April 2009). "Hey, what's that sound: Timpani". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- ^ "Samuel Barber – 'A Stopwatch and an Ordnance Map'". YouTube. 2 January 2017. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ "Philip Glass". philipglass.com.

- ^ ""Susman-Floating Falling"". Steve Weiss Music.

Further reading

[edit]- Adler, Samuel. The Study of Orchestration. W. W. Norton & Company, 3rd edition, 2002. ISBN 0-393-97572-X

- Del Mar, Norman. Anatomy of the Orchestra. University of California Press, 1984. ISBN 0-520-05062-2

- Ferrell, Robert G. "Percussion in Medieval and Renaissance Dance Music: Theory and Performance". 1997. Retrieved 22 February 2006.

- Montagu, Jeremy. Timpani & Percussion. Yale University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-300-09337-3

- Peters, Mitchell. Fundamental Method for Timpani. Alfred Publishing Co., 1993. ISBN 0-7390-2051-X

- Solomon, Samuel Z. How to Write for Percussion. Published by the author, 2002. ISBN 0-9744721-0-7

- Thomas, Dwight. Timpani: Frequently Asked Questions. Retrieved 4 February 2005.

- "Credits: Beatles for Sale". Allmusic. Retrieved 18 February 2005.

- "Credits: A Love Supreme". Allmusic. Retrieved 18 February 2005.

- "Credits: Tubular Bells". Allmusic. Retrieved 18 February 2005.

- "William Kraft Biography". Composer John Beal. Retrieved 21 May 2006.

- "Timpanist – Musician or Technician?". Cloyd E. Duff, Principal Timpani – retired – Cleveland Orchestra.

- "Timpani" Grove, George (January 2001). Stanley Sadie (ed.). The New Grove Encyclopædia of Music and Musicians. Vol. 18 (2nd ed.). Grove's Dictionaries of Music. 826–837. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of timpani at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of timpani at Wiktionary Media related to Timpani at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Timpani at Wikimedia Commons- The Well-Tempered Timpani—Timpani harmonics information

- Website of Guido Rückel, solo-timpanist of Munich Philharmonic; many timpani pictures

- Schlesinger, Kathleen (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 763–766.

- "534m Membranophones". SIL. Archived from the original on 10 July 2006. Retrieved 4 January 2007.

Timpani

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Terminology

Etymology

The term timpani is the plural form of the Italian timpano, meaning "drum" or "kettledrum," which originates from the Latin tympanum, a word denoting a type of drum or tambourine-like instrument employed in ancient rituals.[10][11] This Latin term itself traces back to the Ancient Greek týmpanon (τύμπανον), referring to a frame drum struck to produce a resonant sound, often in ceremonial contexts.[12] The connection to ancient instruments is evident in the Roman adoption of the tympanum, a handheld percussion device associated with religious rites, particularly those honoring deities like Cybele.[12] In English musical nomenclature, the instrument was commonly called "kettledrums" through much of the early modern period, but in the late 19th century, "timpani" gained prominence in English as orchestras increasingly adopted Italian terminology amid the influence of opera and symphonic traditions from Italy and Germany.[10] This linguistic shift reflected broader European standardization in orchestral scoring, where Italian terms became conventional for precision in notation and performance.[10] Parallel developments occurred in other languages, highlighting phonetic and cultural adaptations. The German Pauken (plural of Pauke), meaning "drums," derives from Middle High German pūke, likely an onomatopoeic term mimicking the instrument's booming sound, and became widespread in Germanic musical contexts by the Baroque era.[13] Similarly, the French timbales stems from timbale ("kettledrum"), borrowed from Italian timpano in the 16th century and adapted to denote paired drums in military and later orchestral use, underscoring France's role in refining percussion terminology during the Classical period.[14] These variants illustrate how the core Latin-Greek root evolved through regional phonetic shifts and cultural exchanges across Europe.[10]Alternative Names and Spellings

In English, timpani are commonly referred to as kettledrums or kettle drums, names that emerged in the 16th century to describe the instrument's distinctive hemispherical, kettle-like body.[15] The term "timpani" itself is the Italian plural form of "timpano," denoting a single drum, a usage borrowed into English where "timpani" functions as both singular and plural.[16] Archaic or variant spellings in older English texts occasionally include "tympani" or "tympanis," reflecting influences from the Latin "tympanum."[10] Across languages, regional names highlight cultural and functional nuances. In German, the instruments are known as Pauken, a term rooted in the medieval verb "puken" meaning "to beat," emphasizing their percussive role in orchestral settings with typically deeper tuning.[17] In French and Spanish, the standard term is timbales, which in orchestral contexts specifies tuned kettledrums but can also denote a pair of higher-pitched, single-headed drums in Latin American or jazz ensembles, influencing their perceived tuning and grouping.[7][18] In musical notation and scores, timpani are frequently abbreviated as "Timp." in English and international contexts or "Pk." (short for Pauken) in German editions, streamlining references for performers.[19][20]Historical Development

Pre-Orchestral Origins

The precursors to the timpani originated in ancient Middle Eastern civilizations, where early kettledrum-like instruments appeared as far back as the 13th century B.C. in Egypt, consisting of metal bowls covered with stretched animal skins for rhythmic signaling in rituals and daily life. [21] In the broader Middle East, the naqqāra—a pair of small kettledrums of differing sizes—developed around the 6th century A.D., serving as portable percussion in processions and military contexts across Persian and Arabic cultures. [22] By the 14th century, these naqqāra had become central to Ottoman military bands, known as mehter, where they were mounted on saddles and played to convey commands, intimidate foes, and synchronize troop movements during campaigns. [22] Medieval Europe saw the adoption of these Middle Eastern kettledrums through military encounters and trade, particularly via the Crusades in the 12th and 13th centuries, when Crusaders brought back naker drums—small naqqāra variants—for use in cavalry signals and tournaments. [9] By around 1500, the influence of Turkish janissary bands reached Renaissance courts in Hungary and Western Europe, where sultans' elite corps demonstrated their loud, processional music, inspiring noble households to incorporate paired kettledrums into ceremonial entries, hunts, and festivals as symbols of power and exotic prestige. [23] These drums remained status instruments, often played by mounted timpanists in livery to herald royalty. Early timpani featured hemispherical copper bowls, valued for their resonant tone, covered with natural animal-skin heads such as goat or calf vellum, which were tensioned manually using leather thongs, ropes, or early screw mechanisms around the rim. [9] Without pedals or any mechanical tuning aids, performers adjusted pitch by wedging or loosening the heads on-site, limiting rapid changes but suiting the static roles in military fanfares and rituals. [21]Orchestral Evolution

The timpani entered Western orchestral music in the early 17th century through opera, with Claudio Monteverdi's L'Orfeo (1607) marking one of the earliest scored uses, where paired with trumpets they provided ceremonial emphasis through sforzando chords in dramatic scenes.[24] By the Baroque period, the instrument had become a fixture in orchestras, typically deployed as a fixed-pitch pair tuned a fourth or fifth apart to the tonic and dominant of the prevailing key, reinforcing harmonic pillars in fanfares and supporting brass sections.[25] This configuration, rooted in military traditions where drums signaled on horseback, limited timpanists to diatonic roles but enabled rhythmic vitality in works by composers such as Johann Sebastian Bach and George Frideric Handel.[26] In the 19th century, composers expanded the timpani's expressive potential amid demands for greater agility and sonority. Joseph Haydn's Symphony No. 103 in E-flat major, "Paukenwirbel" (1795), stands as a milestone, opening with a solo timpani roll that builds suspense before the full orchestra enters, elevating the drums from supportive to thematic prominence.[27] Ludwig van Beethoven pushed boundaries by specifying tunings outside the tonic-dominant convention—such as the mediant in octaves for the "Ode to Joy" in Symphony No. 9 (1824)—and occasionally requiring three drums for expanded range, while his scores implied the need for faster retuning during modulations.[28] Hector Berlioz advanced these innovations in Symphonie fantastique (1830), employing up to four timpani tuned to the same pitch for thunderous unison effects in the "March to the Scaffold" and experimenting with sponge-headed mallets for muffled tones, thus treating the instrument as a coloristic and melodic voice.[29] The invention of machine timpani in 1812 by Johann Carl Erdmann introduced hand-operated tuning mechanisms via a single handle connected to tension rods, allowing quicker pitch changes and paving the way for pedal systems.[24] The 20th century saw the standardization of four pedal timpani in orchestral settings, with the pedal mechanism—invented in the 1870s in Dresden—facilitating precise, rapid chromatic tuning and glissandi, transforming the timpani into a versatile soloistic element.[7] This evolution enabled composers like Gustav Mahler to integrate extended solos and dynamic contrasts, as in the storm-like finale of Symphony No. 1 (1889, revised 1906), and Igor Stravinsky to deploy them for primal rhythms and ostinatos in The Rite of Spring (1913), where multiple drums underscore ritualistic intensity.Uses Beyond the Orchestra

Timpani, originating from military signaling roles in ancient and early modern armies, evolved into essential components of marching bands and drum corps by the 20th century. In modern drum and bugle corps competitions under Drum Corps International (DCI), timpani are integral to the front ensemble, delivering tuned melodic and rhythmic support amid high-mobility performances. The 1978 Racine Kilties pioneered the use of concert pedal timpani on the field, marking a shift toward incorporating orchestral percussion in competitive marching formats.[30] Today, many DCI ensembles, such as the Cavaliers and Boston Crusaders, feature dedicated timpanists who navigate challenging outdoor acoustics to blend with brass and battery sections.[31] Beyond marching traditions, timpani gained prominence in jazz, rock, and pop genres during the mid-20th century, often leveraging pedal mechanisms for dynamic pitch shifts and dramatic accents. In jazz, ensembles like Max Roach's M'Boom utilized timpani for improvisational solos and polyrhythmic textures, expanding the instrument's role beyond fixed orchestral settings.[32] Rock acts adopted it for explosive climaxes; for instance, The Beach Boys' 1966 album Pet Sounds employed timpani across tracks like "Wouldn't It Be Nice" to enrich harmonic layers and evoke emotional depth.[33] Similarly, drummer Stephen Perkins integrated timpani into Porno for Pyros' setup in the 1990s, infusing rock with symphonic resonance and tunable intensity.[34] In pop and film scores, pedal timpani create visceral tension through glissandi and rolls, as heard in Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), where they underscore cosmic awe and suspense. John Williams further exemplified this in Star Wars (1977), using timpani for heroic swells and battle motifs.[35] Cultural adaptations highlight timpani's global reach, with variants like the Indian naqqāra—pair of copper kettledrums—serving as core rhythmic elements in Hindustani classical music traditions. Played in ensembles such as naqqal groups, naqqāra provide layered tala cycles and improvisational cues in performances of ragas, maintaining a lineage from Mughal court music into contemporary concerts.[36] African talking drums, hourglass-shaped instruments tuned by lacing tension to mimic speech tones, have shaped modern percussion ensembles by inspiring tunable, gestural techniques in Western avant-garde groups. This influence appears in works by composers like Steve Reich, who drew on West African polyrhythms to blend talking drum expressivity with kettledrum precision in pieces like Drumming (1971).[37]Design and Construction

Core Components

The core components of timpani form the foundational structure that supports resonance and playability. The kettle, or bowl, is the primary resonant chamber, typically constructed from high-grade copper for its superior acoustic properties, though fiberglass and aluminum are also used in modern instruments for durability and lighter weight.[38][39] The bowl's hemispherical or parabolic shape, ranging from approximately 20 to 32 inches in diameter for standard orchestral models, significantly influences the instrument's tone and projection, with hemispherical designs producing brighter sounds and parabolic ones yielding warmer, darker timbres.[39][40] The frame and stand provide stability and ergonomic access for the performer. Historically, frames were often made of cast iron or wood to support the bowl, while modern designs favor lightweight aluminum alloys combined with steel reinforcements for enhanced portability and vibration transmission without unwanted damping.[41] These frames are typically rotatable, allowing the player to position the drum optimally, and feature height-adjustable legs or tripod bases to accommodate various performers and stage setups.[42] Securing the drumhead relies on the counterhoop and tension rods, which form a basic mechanical system for attachment. The counterhoop, a rigid circular rim, clamps the head in place over the bowl's edge, while 6 to 8 tension rods—often threaded screws in early hand-tuned models—allow manual adjustment to maintain even tension across the head.[39] This setup integrates with tuning systems to enable pitch changes during performance.[43]Tuning Systems

Early timpani were hand-tuned using individual tension rods or screws around the counterhoop, adjusted manually with a specialized key to alter the drumhead tension and thus the pitch.[9] This method required the player to tighten or loosen each rod sequentially, often starting opposite the striking area to ensure even tension, and was the standard practice until the early 19th century when orchestral demands for faster tuning grew.[7] By the 1810s, innovations like Gerhard Kramer's master screw mechanism linked multiple rods to a single handle, simplifying adjustments but still relying on manual operation.[7] The development of pedal timpani in the mid-19th century revolutionized pitch changes, enabling quick tuning without removing hands from sticks. In 1843, German machinist August Knocke patented the first pedal-operated system, but it was Carl Pittrich's 1881 Dresden model that popularized the design, featuring a foot pedal connected to a spiderweb of tension rods via a ratchet or clutch mechanism for locking pitches.[9] The Dresden system uses a central linkage that distributes tension evenly across the head when the pedal is depressed, allowing rapid shifts during performance.[44] A variant, the Berlin model, employs a similar pedal but with a more streamlined lever arm and finer adjustment capabilities, often preferred for its durability and precise control in professional settings.[45] These pedal systems, now dominant in orchestral use, support balanced action or locking mechanisms to maintain tension without constant foot pressure.[46] Less common alternatives include chain and rotary tuning systems, which offer specialized advantages in certain contexts. Chain systems link the tension rods with a continuous chain operated by a master handle or key, providing smoother and more consistent adjustments compared to individual rods, though they can be prone to wear over time.[47] Rotary mechanisms, typically found in educational or compact models, allow pitch changes by rotating the entire drum shell or a central handle connected to the tension assembly, facilitating easy tuning for beginners but limiting speed in dynamic performances.[48] These systems prioritize simplicity and portability over the rapid response of pedals, with chains excelling in even distribution but requiring periodic maintenance for chain integrity.[47] Post-2000 developments have introduced hybrid tuning aids, integrating electronic tools with traditional mechanisms to enhance precision. Electronic tuners, such as resonance-based devices like Sona, analyze head vibrations to guide adjustments without audible striking, enabling quiet and accurate tuning in rehearsal or performance environments.[49] Prototypes for semi-automated systems, including programmable pedals that preset multiple pitches via motorized tensioners, have emerged from patents like US7888568B2 (2011), aiming to minimize manual intervention while preserving acoustic integrity.[50] These innovations build on pedal designs but incorporate sensors for real-time feedback, though full auto-tuning remains experimental due to the need for subtle head tempering.[51]Drumheads and Materials

Timpani drumheads have traditionally been crafted from natural animal skins, primarily calfskin, which provides a warm, resonant tone prized in orchestral settings. Calfskin heads, typically sourced from young calves for their thin and uniform texture, produce a rich fundamental pitch with complex overtones due to the material's organic structure and slight irregularities. However, these heads are highly sensitive to environmental factors, such as humidity and temperature fluctuations, which cause natural tension variations and can lead to pitch instability or the need for frequent adjustments and maintenance.[52][53] The introduction of synthetic drumheads in the mid-20th century marked a significant advancement in timpani construction, offering greater reliability for professional performers. Developed by Remo Belli in 1957, the first commercially successful synthetic heads used Mylar (a polyester film) as the primary material, revolutionizing drumhead production by providing weather-resistant properties that maintain consistent tension and pitch regardless of humidity changes. Makers like Remo quickly adapted these innovations for timpani, producing heads that are more durable and cost-effective than calfskin, lasting longer under repeated use and costing approximately one-tenth as much.[54][55][56] Historically, drumheads were attached to the timpani shell using rudimentary methods, such as nailing the skin directly to the shell in early untunable models or employing rope tensioning with leather thongs around a counterhoop, which allowed basic tuning but often resulted in uneven stretching. By the 15th century, counterhoops became standard, tied with ropes for adjustment, though this system limited rapid retuning. Modern synthetic heads, in contrast, are secured via rod tension systems on the counterhoop, enabling precise and uniform application of pressure across the surface; some feature printed tuning dots or markers to visually indicate optimal tension points and pitch alignment during setup.[52] The evolution from animal hides to synthetic materials like Mylar has profoundly influenced the acoustic profile of timpani, shifting from the variable warmth and nuanced attack of calfskin—characterized by a softer initial strike and longer natural decay—to the brighter, more predictable sustain and sharper attack of plastics, which reduce unwanted overtones for cleaner ensemble integration. Calfskin offers a deeper, more organic resonance that blends well in acoustic halls but requires careful environmental control, whereas Mylar heads provide enhanced projection and stability, particularly in varied performance conditions, allowing timpanists to focus on expressive playing rather than maintenance. This material progression, accelerated post-1950s, reflects broader trends in instrument design toward reliability without sacrificing tonal depth.[53][57][58]Performance Equipment

Sticks and Mallets

Timpani mallets, also known as sticks, are specialized beaters designed to produce a wide range of tones on the instrument's drumhead, with variations primarily determined by the head's core material, covering, and overall construction. Hard mallets typically feature wood or plastic cores wrapped in firm felt, delivering bright and articulate attacks suitable for precise, rhythmic passages in styles like Baroque music. For instance, the Vic Firth American Custom T5 model uses a solid wood head on a hickory shaft, providing a sharp, penetrating sound ideal for special effects and staccato playing.[59] Similarly, plastic-cored mallets, such as those with hard phenolic cores and thin felt coverings, emphasize clarity and projection, often used in modern orchestral contexts requiring crisp articulation. Soft mallets, in contrast, employ yarn or wool coverings over softer cores like felt or cork, generating muffled, resonant tones that facilitate rolling passages and legato effects. These are essential for producing warm, blended sounds in Romantic and contemporary repertoire, with medium-hardness variants serving as general-purpose tools for balanced orchestral use. The Vic Firth T2 Cartwheel mallets, with their large, soft felt heads on hickory handles, excel in creating smooth rolls and sustained dynamics. Wool-headed models, such as the Sonor SCH8, offer a particularly velvety timbre, enhancing the instrument's fundamental pitch while reducing overtones for intimate passages.[60] Specialized mallets cater to niche applications, including sponge-headed types for jazz and fusion settings, where they yield a drier, less resonant impact akin to hand drumming. Cartwheel-style mallets, with oversized heads, are optimized for rapid rolls and volume swells, while historical bamboo-shafted sticks provide lightweight responsiveness favored in earlier traditions. Manufacturers like Vic Firth and Grover Pro Percussion emphasize balanced construction, with mallets typically weighing 40-60 grams each and measuring 35-40 cm in length to ensure ergonomic control across dynamics.[61][62] These designs allow brief adaptation to various grips for enhanced precision in performance.[63]Holding Grips

Timpani players employ specific holding grips to achieve optimal control, tone production, and endurance during performances. These grips position the mallets—thicker and heavier than snare drum sticks—to facilitate rebound, wrist motion, and finger independence, essential for the instrument's dynamic range and resonant sound.[64] The choice of grip influences the player's ability to execute nuanced rolls and articulate strikes while minimizing fatigue over extended orchestral sessions.[65] The matched grip, also known as the German grip, involves holding both mallets similarly with the palms facing downward and thumbs positioned parallel to the sticks, turned slightly inward so the sticks angle toward each other. The fulcrum rests between the thumb and index finger, with the remaining fingers curled underneath for support, allowing even power distribution and clear articulation on downstrokes. This grip, akin to standard snare drum technique, promotes balanced rebound and is favored in modern playing for its straightforward ergonomics, enabling efficient wrist rotation without excessive tension.[64][66] In contrast, the traditional French grip, often called the thumbs-up grip, positions the thumbs atop the sticks with palms facing inward, keeping the mallets parallel to each other. The fulcrum is primarily at the thumbs, with fingers nestled below to provide finesse and subtle control, particularly for sustained rolls and dynamic variations. This method emphasizes finger independence and relaxed wrist motion, reducing strain during prolonged performances and offering superior nuance for expressive playing, which is why it remains the preferred choice among many professional timpanists.[64][65] A variation, the American grip, serves as a hybrid between the German and French styles, with thumbs placed halfway between the side and top of the sticks, palms angled slightly outward. This positioning balances the fulcrum for versatile rebound and control, accommodating speed in rapid passages while maintaining ergonomic comfort through moderate wrist rotation. It adapts elements of both primary grips to suit individual hand sizes and preferences, enhancing overall adaptability without favoring one extreme.[64][66] Ergonomically, all grips prioritize a relaxed hold to prevent fatigue, with the butt of the mallet allowing slight free-play in the hand's groove for natural bounce. Finger control and wrist pivoting are key to varying tone and volume, ensuring sustained performance quality; these elements are often paired briefly with mallet types for tailored response.[67][64]Playing Techniques

Striking Methods

Timpani single strokes are fundamental for producing clear, articulated attacks in rhythmic passages, executed primarily through a wrist snap that initiates a piston-like motion of the mallet. This technique involves starting the mallet in an upward position, allowing it to descend vertically onto the head with controlled rebound facilitated by wrist rotation, ensuring a resonant tone without excessive arm involvement.[66] The location of the strike on the drumhead significantly influences the resulting tone; striking near the center emphasizes the fundamental pitch with a fuller bass response, while positions closer to the edge highlight higher harmonics, producing a brighter, more metallic timbre. For optimal fundamental tone production, players target precise zones approximately 4 inches from the rim, equivalent to about one-third of the head's radius, where vibrations propagate most evenly across the membrane. Varying these zones allows timpanists to tailor timbre for specific musical effects without altering pitch.[68][69] Rolls on timpani sustain tones over extended durations, most commonly achieved via single-stroke rolls using alternating sticks to leverage the instrument's natural resonance, with the mallets separated by 6-8 inches while striking at points approximately 2-4 inches from the rim for a legato quality. In scenarios requiring denser or faster continuity, double-stroke rolls—employing rapid paired bounces from each wrist—or buzz techniques, where mallets vibrate loosely against the head, provide alternative methods for rhythmic density while maintaining sustain. These roll variants adapt to the drum's size and pitch range, accelerating on smaller, higher-tuned instruments for even timbre.[70][71][72] Dynamic control in striking ranges from delicate pianissimo taps, using minimal velocity and softer mallets for subtle resonance, to powerful forte crashes achieved with greater force and harder sticks, which amplify projection and attack clarity. Stick choice—such as felt, wood, or cork heads—further modulates volume and timbre, with velocity variations directly correlating to intensity levels across the full dynamic spectrum. Specific holding grips, like the French or German styles, support these executions by optimizing wrist flexibility and mallet control.[73]Tuning and Adjustment

Timpani tuning begins prior to performance with the timpanist selecting a reference pitch, often from a pitch pipe, tuning fork, or electronic chromatic tuner, to establish the desired fundamental tone. The head tension is then adjusted by turning the tension rods—clockwise to increase tension and raise the pitch, or counterclockwise to decrease tension and lower the pitch—ensuring even distribution across all rods for uniform resonance.[74][43] Once initial tension is set, intonation checks are performed by striking the head and listening for clear overtones that align with the fundamental pitch, indicating proper "tempering" of the head for a sustained tone and rich harmonics. To settle any residual vibrations and stabilize the pitch, the timpanist "clears" the head by firmly playing it several times, allowing the membrane to fully respond before fine adjustments are made.[75][76] During performance, modern pedal mechanisms enable rapid on-the-fly pitch changes; depressing the pedal tightens the head for a higher pitch, while releasing it loosens the head for a lower one, often allowing semitone adjustments in mere seconds through balanced spring action and clutch systems that lock the position. Historically, before the widespread adoption of pedals in the 19th century, hand-tuning with T-handles or multiple screws was standard, a process that could take several minutes per drum and posed significant challenges in large ensembles where quick pitch shifts were impractical, limiting timpanists to static roles on tonic and dominant notes.[43][7][77] Some timpani heads feature visual tuning indicators, such as colored dots, to assist in consistent setup across performances.[78]Muffling and Extended Techniques

Muffling techniques are essential for timpanists to control the instrument's inherent long sustain and prevent unwanted resonance between notes. The primary method involves hand dampening, where the player places the pads of the fingertips lightly on the drumhead immediately after striking, often while maintaining grip on the mallet with the thumb and index finger of the same hand. This allows for precise cutoff of the sound, with variations such as using the pinky finger of the non-playing hand for a slightly shorter decay without fully stopping the vibration. In some cases, felt pads are applied directly to the head for more consistent muffling across multiple strikes, particularly in ensemble settings to avoid sympathetic ringing. Pedal mechanisms do not inherently dampen, but coordinated hand and foot actions enable rapid adjustments during performance.[79][80][81] Extended techniques on timpani push beyond conventional mallet strikes to explore timbral and textural possibilities, particularly in 20th- and 21st-century repertoire. Glissandi, for instance, are produced by depressing or releasing the tuning pedal while executing a continuous roll on the head, creating smooth pitch slides in either direction at any dynamic level; this effect gained prominence in modern orchestral writing, as exemplified in scores by composers like Krzysztof Penderecki for dramatic, sliding transitions. Finger strikes provide subtle, nuanced tones by lightly tapping the head with one or more fingers, yielding soft attacks and overtones suitable for atmospheric or intimate passages, often combined with partial dampening for controlled resonance. Octave harmonics, another early extended approach, involve striking near the edge while lightly touching the center to emphasize higher partials, though its faint result limited its adoption in later works.[7][82] In contemporary music, innovations further diversify timpani expression through prepared heads and integrated setups. Preparation entails placing objects such as coins, rubber, or small instruments on the drumhead to modify pitch, attack, and timbre, enabling metallic scrapes or muted thuds; representative examples include Stephen Ridley's Animism for prepared timpani and tape, which layers these alterations with electronic elements for evolving textures. Multi-percussion configurations treat the timpani as part of a broader station, incorporating auxiliary items like bowed cymbals placed on the head for hybrid bowed-percussive effects using rosined implements, a practice emerging in post-1970s experimental scores. Electronic amplification extends the instrument's range in blended ensembles, allowing processed signals to integrate with other amplified sounds for heightened presence or spatial effects in avant-garde compositions.[83][84]Role in Ensembles

Standard Configurations

In professional classical orchestras, the standard timpani configuration consists of four drums with diameters of 32 inches, 29 inches, 26 inches, and 23 inches, tuned chromatically to cover a range of approximately three octaves from around G2 to G4.[4][7] These drums are typically arranged in international style with the lowest-pitched drum on the player's left and pitch ascending to the right, facilitating efficient tuning and playing during performances.[85] Many ensembles expand to five drums by adding a 20-inch model for higher pitches, enhancing chromatic flexibility in modern repertoire.[70] Historical and genre-specific variations exist in timpani setups. In Baroque ensembles, configurations often limit to two fixed-pitch drums, typically tuned a fourth apart to the tonic and dominant of the key for rhythmic support.[25] Opera orchestras frequently employ five or six drums to accommodate broader pitch demands across extended scores, allowing for rapid chromatic adjustments.[7] For marching bands, portable single timpani units or compact sets on wheeled carts are used, prioritizing mobility over full orchestral arrays while maintaining tunable pitches for field or pit applications.[86][87] Timpani are positioned behind the string section in orchestral layouts, with the player oriented to face the conductor for clear visual cues and balanced ensemble integration.[88] Modern professional setups incorporate mobile carts to facilitate quick repositioning and transport between venues.[85] Size standards vary slightly between German and American scales, influencing optimal pitch ranges. In the American scale, the 32-inch drum typically resonates from D2 to A2, while German equivalents (around 81 cm) align closely but may emphasize slightly lower fundamentals for richer tone in European tuning traditions.[89][90] These differences ensure compatibility across international ensembles, with the 32-inch model serving as the bass foundation in both systems.[91]Notable Players

One of the earliest documented influential timpanists was Ernst Gotthold Benjamin Pfundt (1806–1871), who served as principal timpanist for the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra from 1835 until his death, performing under conductors like Felix Mendelssohn. Pfundt was distantly related to Robert Schumann by marriage (as his cousin-in-law).[92][93] Pfundt innovated timpani mallets by designing sponge-headed versions (Schwammschlägel) in 1849, which produced a softer tone suitable for orchestral settings, and he authored the seminal method book Die Pauken (1849), providing guidance on tuning, sticking, and performance practices that advanced the instrument's technical standards.[94] His work elevated the timpanist's role from military signaler to precise orchestral contributor, earning praise from composers like Hector Berlioz and Richard Wagner as one of Europe's premier players.[95] In the 20th century, Saul Goodman (1907–1996) became a cornerstone of timpani pedagogy as principal timpanist of the New York Philharmonic from 1926 to 1972, where his consistent tone and rhythmic precision defined the ensemble's sound.[96] Goodman authored Modern Method for Timpani (updated editions through 1990s), a foundational text that systematized exercises for technique development across two to five drums, muffling, and pedal work, influencing generations of players through its emphasis on fundamentals and orchestral excerpts.[97] Similarly, Cloyd Duff (1916–2000), principal timpanist of the Cleveland Orchestra from 1942 to 1981, innovated tuning practices by developing the "Duff Clearing Process," a method for adjusting head tension to achieve clear, resonant overtones, which remains a standard in professional training.[98] Duff's approach prioritized acoustic precision and endurance, contributing to the instrument's evolution in large-scale symphonic repertoire.[99] Contemporary timpanists continue to expand the instrument's visibility and standards. Jonathan Haas, a prolific soloist and educator, has performed the only solo timpani recital at Carnegie Hall's Weill Recital Hall and commissioned works like Philip Glass's Concerto Fantasy for Two Timpanists and Orchestra, showcasing advanced pedal techniques and extended ranges in recordings and concerts worldwide.[100] As a faculty member at The Juilliard School and NYU Steinhardt, Haas influences equipment standards through endorsements and clinics on maintenance, while promoting education via masterclasses that address modern innovations.[101] Timpanists like Haas often navigate multi-instrumentalist demands in orchestras, balancing timpani with auxiliary percussion, which requires exceptional endurance for long rolls and rapid tuning adjustments under performance pressure. This role demands precision in pitch control and rhythm, as even minor deviations can disrupt ensemble balance, underscoring the timpanist's critical yet physically taxing position.[102]Solos and Concertos