Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Valencia CF

View on Wikipedia

Valencia Club de Fútbol, S. A. D. (Spanish: [baˈlenθja ˈkluβ ðe ˈfuðβol]; Valencian: València Club de Futbol [vaˈlensi.a ˈklub de fubˈbɔl]),[3] commonly referred to as Valencia CF or simply Valencia, is a Spanish professional football club based in Valencia, Spain, that currently plays in La Liga, the top tier of the Spanish league system. Valencia was founded in 1919 and has played its home games at the 49,430-seater Mestalla since its opening in 1923.[2]

Key Information

Valencia has won six La Liga titles, eight Copa del Rey titles, one Supercopa de España, and one Copa Eva Duarte. In European competitions, they have won two Inter-Cities Fairs Cups, one UEFA Cup, one UEFA Cup Winners' Cup, two UEFA Super Cups, and one UEFA Intertoto Cup. They have also reached two consecutive UEFA Champions League finals (2000 and 2001). The IFFHS named World’s Best Club to Valencia in 2004. Valencia were also members of the G-14 group of leading European football clubs and since its end has been part of the original members of the European Club Association.

Five former members of the club have been inducted into the FIFA International Football Hall of Fame, a project dedicated to preserving the memory of important figures in football history. These include Alfredo Di Stéfano, Mario Alberto Kempes, Romário, Jorge Valdano and Didier Deschamps. Valencia also has four personalities in the FIFA 100, its induction taking place in 2004 as part of the centenary celebrations of FIFA's creation. The ches club is the team with the most Zarra Trophy winners (5), the fourth in the Zamora Trophy (9) and fifth in the Pichichi Trophy (6) at the national level, at the international level it’s the third Spanish team with the most FIFA World Player nominees (9) and the fourth in the Ballon d'Or (23), it has ten nominations for the Golden Boy Award, one for the 2019 Kopa Trophy with Lee Kang-in and one for the 2024 Yashin Trophy with Giorgi Mamardashvili. It has been included three times in the UEFA Team of the Year, with Santiago Cañizares and Kily González in 2001 and David Villa in 2010, the last repeating in the FIFPro World XI in the same year.

Four Valencia players were part of the Spanish national team that won the 2010 FIFA World Cup: David Villa, who won the Silver Boot as the second-highest scorer, tied with Thomas Müller on five goals and the Bronze Ball as the third best player in the final phase of the championship, Carlos Marchena, David Silva and Juan Mata. Seven of its members have managed to win Olympic Games medals throughout its history: David Albelda and Miguel Ángel Angulo, silver in Sydney 2000; Fabián Ayala, gold in Athens 2004; Éver Banega, gold in Beijing 2008; Carlos Soler, silver in Tokyo 2020; Cristhian Mosquera and Diego López, gold in Paris 2024.

Over the years, the club has achieved a global reputation for their prolific youth academy, or "Acadèmia". Products of their academy include world-class talents such as Miguel Tendillo, Ricardo Arias, Fernando Gómez, Andrés Palop, Javier Farinos, Raúl Albiol, David Albelda, Vicente Rodríguez, Gaizka Mendieta and David Silva. Current stars of the game to have graduated in recent years include Isco, Jordi Alba, Paco Alcácer, Juan Bernat, José Gayà, Carlos Soler, Ferran Torres, Lee Kang-in, Cristhian Mosquera, and Javi Guerra.

Historically one of the biggest clubs in the world in terms of number of associates (registered paying supporters), with around 50,000 season ticket holders[4] at their peak, the club began to decline in the mid-2010s. Singaporean billionaire Peter Lim acquired the team in 2014.[5][6]

History

[edit]The club was established on 5 March 1919 and officially approved on 18 March 1919, with Octavio Augusto Milego Díaz as its first president; incidentally, the presidency was decided by a coin toss. The club played its first competitive match away from home on 21 May 1919 against Valencia Gimnástico, and lost the match 1–0.

Valencia moved into the Mestalla Stadium in 1923, having played its home matches at the Algirós ground since 7 December 1919. The first match at Mestalla pitted the home side against Castellón Castalia and ended in a 0–0 draw. In another match the day after, Valencia won 1–0 against the same opposition. Valencia CF won the Regional Championship in 1923, and was eligible to play in the domestic Copa del Rey cup competition for the first time in its history.

1940s: Emergence as a giant in Spanish football

[edit]

The Spanish Civil War halted the progress of the Valencia team until 1941, when it won the Copa del Rey, beating RCD Espanyol in the final. In the 1941–42 season, the club won its first Spanish La Liga championship title, although winning the Copa del Rey was more reputable than the championship at that time. The club maintained its consistency to capture the league title again in the 1943–44 season, as well as the 1946–47 league edition. They would conclude their decade of success by winning the 1949 Copa del Rey; this meant Valencia ended the decade with a record of three La Liga and two Copa del Rey titles. This success would help cement the club's name in Spanish football.

In the 1950s, Valencia failed to emulate the success of the previous decade, even though it grew as a club. A restructuring of Mestalla resulted in an increase in spectator capacity to 45,000, while the club had a number of Spanish and foreign stars. Players such as Spanish international Antonio Puchades and Dutch forward Faas Wilkes graced the pitch at Mestalla. In the 1952–53 season, the club finished as runners-up in La Liga, and in the following season, won the Copa del Rey, then known as the Copa del Generalísimo.

1960s: European successes in the Fairs Cup

[edit]While managing average league form in the early 1960s, Valencia had its first European success in the form of the Inter-Cities Fairs Cup (the forerunner to the UEFA Cup), defeating Barcelona in the final of the 1961–62 edition. The following edition of the tournament pitted Valencia against Croatian club Dinamo Zagreb in the final, which the Spanish side also won. Valencia reached a third consecutive Inter-Cities Fairs Cup final in the following season, but this time were defeated 2–1 by fellow Spanish club Zaragoza.

1970s to early 1980s: More domestic and European glory

[edit]

Former two-time European Footballer of the Year award winner Alfredo Di Stéfano was hired as Valencia coach in 1970, and immediately inspired his new club to their fourth La Liga championship and first since 1947. This secured Valencia its first qualification for the prestigious European Cup, contested by the various European domestic champions. Valencia reached the third round of the 1971–72 competition before losing both legs to Hungarian champions Újpesti Dózsa. In 1972 the club also finished runners-up both in La Liga and the domestic cup, losing to Real Madrid and Atlético Madrid, respectively. The most notable players of the 1970s era include Austrian midfielder Kurt Jara, forward Johnny Rep of the Netherlands and Argentinian forward Mario Kempes, who was consecutively La Liga top scorer in 1976–77 and 1977–78. Valencia would go on to win the Copa del Rey again in the 1978–79 season, and also capture the European Cup Winners' Cup the next season, after beating English club Arsenal in the final, and the European Super Cup against Nottingham Forest thanks to the away goals rule, with Kempes spearheading their success in Europe.

Mid to late 1980s: Stagnation and relegation

[edit]

In 1982, the club appointed Miljan Miljanić as coach. After a disappointing season, Valencia was in 17th place and faced relegation with seven games left to play. Koldo Aguirre replaced Miljanić as coach, and Valencia barely avoided relegation that year, relying on favorable results from other teams to ensure their own survival. In the 1983–84 and 1984–85 seasons, the club was heavily in debt under the presidency of Vicente Tormo. The club finally hit rock bottom when it was relegated at the end of the 1985–86 season, and riven with internal problems such as unpaid player and staff wages, as well as poor morale. The club was relegated for the first time after 55 years in Spanish top-flight football.

Arturo Tuzón was named the new club president, and he helped steer Valencia back to La Liga. Alfredo Di Stéfano returned as coach in 1986 and Valencia won promotion again following the 1986–87 season. Di Stéfano stayed on as coach until the 1987–88 season, when the team finished in 14th position in La Liga. Bulgarian forward Luboslav Penev joined the club in 1989, as Valencia aimed to consolidate their place in La Liga. In the 1988–89 La Liga season, Valencia finished third, which would signal their competitiveness going into the 1990s.

1990s: Re-emergence

[edit]

In the 1989–90 La Liga season, Valencia finished as runners-up to Real Madrid, and thus qualified for the UEFA Cup.

Guus Hiddink was appointed as head coach in the 1991–92 season, and the club finished fourth in the League and reached the quarter-finals of the Copa del Rey. In 1992, Valencia officially became a Sporting Limited Company, and retained Hiddink as their coach until 1993.

Brazilian coach Carlos Alberto Parreira, fresh from winning the 1994 FIFA World Cup with the Brazil national team, became manager at Mestalla in 1994. Parreira immediately signed Spanish goalkeeper Andoni Zubizarreta, Russian forward Oleg Salenko, and Predrag Mijatović, but failed to produce results expected of him. He was replaced by new coach José Manuel Rielo. The club's earlier successes continued to elude it, although it was not short of top coaching staff like Luis Aragonés and Jorge Valdano, as well as foreign star forwards like Brazilian Romário, Claudio López, Ariel Ortega from Argentina, and Adrian Ilie from Romania. In the 1995–96 La Liga season, Valencia finished second to Atlético Madrid, being unable to capture the title after a close fought race.

Valencia would struggle for the next two seasons, but the 1998–99 La Liga season would signal the start of one of the club's most successful periods in their history; they lifted their first trophy in nineteen years by winning the 1998–99 Copa del Rey under Claudio Ranieri, and also qualified for the UEFA Champions League.

2000s: Valencia returns to the top of Spanish and European football

[edit]Valencia started the 1999–2000 season by winning another title, beating Barcelona in the Spanish Super Cup. Valencia finished third in the league, four points behind champions Deportivo La Coruña, and level on points with second-placed Barça. The biggest success for the club, however, was in the Champions League; for the first time in its history, Valencia reached the European Cup final. However, in the final played in Paris on 24 May 2000, Real Madrid would beat Valencia 3–0.

The final would also be Claudio López's farewell, as he had agreed to sign for Italian side Lazio; also leaving was Farinós for Inter Milan and Gerard for Barcelona. The notable signings of that summer were John Carew, Rubén Baraja, Roberto Ayala, Vicente Rodríguez, and Brazilian left-back Fábio Aurélio. That season Valencia also bought Pablo Aimar in the winter transfer window. Baraja, Aimar, Vicente, and Ayala would soon become a staple of Valencia's dominance of the early 2000s in La Liga.

Valencia started the championship on the right foot and were top of the league after ten games. After the Christmas break, however, Valencia started to pay for the top demand that such a draining competition like the Champions League requires. After passing the two mini-league phases, Héctor Cúper's team eliminated English sides Arsenal in the quarter-finals and Leeds United in the semi-finals, reaching the final for the second consecutive year. In the final match against Bayern Munich, played in Milan at the San Siro on 23 May, Gaizka Mendieta gave Valencia the lead by scoring from the penalty spot right at the start of the match. Goalkeeper Santiago Cañizares then stopped a penalty from Mehmet Scholl, but Stefan Effenberg drew Bayern level after the break thanks to another penalty. After extra time, the match went to a penalty shoot-out, where a Mauricio Pellegrino miss gave Bayern Champions League glory and dealt Valencia a second-straight defeat in the final. Valencia went on to slip to fifth place in La Liga and out of the Champions League positions for the 2001–02 season. Going into the final league match, Valencia only needed a draw at the Camp Nou against Barcelona to seal Champions League qualification. However, Los Che lost to Barcelona 3–2, with a last minute goal completing a hat-trick from Rivaldo, resulting in Barcelona qualifying for the Champions League ahead of their side.

Valencia president D. Pedro Cortés resigned for personal reasons and left the club in July, with the satisfaction of overseeing the club win the Copa del Rey and Spanish Super Cup, as well as reaching two successive Champions League finals. D. Jaime Ortí replaced Cortés as president and expressed his intention of maintaining the good form that had made the club so admired on the European circuit. There were also some changes in the team and staff. Rafael Benítez, after helping Tenerife to promotion, replaced Héctor Cúper after the latter became the new coach at Inter in Italy. Among the playing squad, Gaizka Mendieta, Didier Deschamps, Luis Milla, and Zlatko Zahovič left, while Carlos Marchena, Mista, Curro Torres, Francisco Rufete, Gonzalo de los Santos, and Salva Ballesta all arrived.

From 1999 up until the end of the 2004 season, Valencia had one of their most successful periods in the club's history. With a total of two La Liga titles, a UEFA Cup, a Copa del Rey, and a UEFA Super Cup in those six years, no less than five first class titles and two Champions League finals had been achieved.

That first match against fellow title rivals Real Madrid produced a significant and important victory. This was followed by a record of eleven consecutive wins, breaking their existing record set in the 1970–71 season, which was also the club's La Liga title win under Alfredo Di Stéfano.

After a defeat in A Coruña against Deportivo on 9 December 2001, the team had to overcome Espanyol at the Estadi Olímpic Lluís Companys to avoid further backsliding behind the league leaders. at half-time, Valencia were 2–0 down, but a comeback in the second half saw them win 3–2.

In the second part of the season, Benítez's team suffered a temporary setback after losing 1–0 at the Santiago Bernabéu to Real Madrid, but in the coming six matches they recovered from this defeat and achieved four victories and two draws.

In one of these crucial games against Espanyol, Valencia were trailing 1–0 at half-time and down a player as well following the dismissal of Carboni. However, after a second half brace from Rubén Baraja, they would achieve a 2–1 comeback win. Furthermore, Real Madrid's defeat at the Anoeta to Real Sociedad left Valencia with a three-point lead at the top of the table.

Valencia's final game of the season was on 5 May 2002 at La Rosaleda against Málaga, a day that has gone down in Valencia's history. The team shut itself away in Benalmádena, close to the scene of the game, in order to gain focus. An early goal from Roberto Ayala and another close to half-time from Fábio Aurélio secured Valencia a fifth La Liga crown, 31 years after their last title win.

The 2002–03 season was a disappointing one for Valencia, as they failed in their attempt to retain the La Liga title and ended up outside of the Champions League spots in fifth, behind Celta Vigo. They were also knocked out in the quarter-finals of the Champions League by Inter Milan on away goals. The 2003–04 season saw Valencia trailing longtime leaders Real Madrid. In February, with 26 matches played, Madrid were eight points clear at the top of the table.[7] However, their form severely declined in the late stage of the season, and consecutive losses in their last five games of the campaign allowed Valencia to overtake them and claim the title, their second in three seasons. The club also added the UEFA Cup to this success, defeating Marseille 2–0 in the final.

In the summer of 2004, manager Benítez decided to depart Valencia, stating he had had problems with the club president; he would soon become head coach of Liverpool. He was replaced by former Valencia coach Claudio Ranieri, who had recently been sacked by Chelsea. Despite lifting the European Super Cup after defeating UEFA Champions League winners Porto, his second reign at the club was a disappointment; Valencia harboured realistic hopes of retaining their La Liga crown but, by February, found themselves in seventh place. Valencia had also been knocked out of the Champions League group phase, with Ranieri being sacked promptly in February. The 2004–05 season ended with Valencia outside of the UEFA Cup spots.

In the summer of 2005, Getafe coach Quique Flores was appointed as the new manager of Valencia and ended the season in third place, which in turn gained Valencia a place in the Champions League after a season away from the competition. The 2006–07 season was one with many difficulties; a campaign which started with realistic hopes of challenging for the title was disrupted with a huge list of injuries to key players, as well as internal arguments between Flores and new sporting director Amedeo Carboni. Valencia ended the season in fourth place and were knocked out of the Champions League in the quarter-finals by Chelsea 3–2 on aggregate, after they had knocked out Italian champions Inter in the second round. In the summer of 2007, the internal fight between Flores and Carboni was settled, with Carboni being replaced by Ángel Ruiz as the new sporting director of Valencia.

On 29 October 2007, the Valencia board of directors fired Flores after a string of disappointing performances, and caretaker manager Óscar Fernández took over on a temporary basis until a full-time manager was found, rumoured to be either Marcello Lippi or José Mourinho. A day later, Dutch manager Ronald Koeman announced he would be leaving PSV Eindhoven to sign for Valencia. However, Koeman's appointment failed to lead to improvement; in fact, Valencia even went on to drop to the 15th position in the league, just two points above the relegation zone. Despite their poor league form, Valencia would still go on to lift the Copa del Rey on 16 April 2008, following a 3–1 victory over Getafe at the Vicente Calderón. This was the club's seventh Copa title. Five days later, one day after a devastating 5–1 league defeat in Bilbao, Valencia fired Koeman and replaced him with Voro, who would guide Valencia as caretaker manager for the remainder of the season. He went on to win the first match since the sacking of Koeman, beating Osasuna 3–0. Voro would eventually drag Valencia from the relegation battle to a safe mid-table finish of tenth place, finally ending a disastrous league campaign for Los Che.

Highly rated Unai Emery was announced as the new head coach of Valencia on 22 May 2008. The start of the young manager's career looked to be promising, with the club winning four out of its first five games, a surge that saw the team rise to the top position of the La Liga table. Despite looking impressive in Europe, Los Che then hit a poor run of form in the league that saw them dip as low as seventh in the standings. Amid the slump emerged reports of a massive internal debt at the club exceeding 400 million euros, as well as that the players had been unpaid for weeks. The team's problems were compounded when they were knocked out of the UEFA Cup by Dynamo Kyiv on away goals. After a run where Valencia took only five points from ten games in La Liga, an announcement was made that the club had secured a loan that would cover the players' expenses until the end of the year. This announcement coincided with an upturn in form, and the club won six of its next eight games to surge back into the critical fourth place Champions' League spot. However, Los Che were then pushed down to sixth place in the league following defeats to top four rivals Atlético Madrid and Villarreal in two of their final three games, meaning they failed to qualify for the Champions League for a second successive season.

2010–2014: Debt issues and stability

[edit]

No solution had yet been found to address the massive debt Valencia was faced with, and rumors persisted that top talents such as David Villa, Juan Mata, and David Silva could leave the club to help balance the books. In the first season of the new decade, Valencia returned to the Champions League for the first time since the 2007–08 campaign, as they finished comfortably in third place in the 2009–10 La Liga standings. However, in the summer of 2010, due to financial reasons, David Villa and David Silva were sold to Barcelona and Manchester City, respectively, to reduce the club's massive debt. Despite the loss of two of the club's most important players, the team was able to finish comfortably in third place again in the 2010–11 La Liga for the second season running, although they would be eliminated from the Champions League by German side Schalke 04 in the round of 16. In the summer of 2011, then-captain Juan Mata was sold to Chelsea to further help Valencia's precarious financial situation. It was announced by club president Manuel Llorente that the club's debt had been decreased and that the work on the new stadium would restart as soon as possible, sometime in 2012.

During the 2012–13 season, Ernesto Valverde was announced as the new manager, but after failing to qualify for the Champions League, he stepped down and was replaced by Miroslav Đukić. On 5 July 2013, Amadeo Salvo was named as the new president of the club. Almost a month after Salvo was named president, on 1 August, Valencia sold star striker Roberto Soldado to English club Tottenham Hotspur for a reported fee of €30 million. Đukić was sacked six months into the 2013–14 season after just six wins in his first sixteen matches, Valencia's worst start to a season in fifteen years.[9] He was replaced by Juan Antonio Pizzi on 26 December 2013.[10] Under Pizzi, Valencia reached the semi-finals of the UEFA Europa League, where they lost to eventual winners Sevilla on away goals, and finished eighth in La Liga despite a disastrous start to the season.[11][12]

2014–present: Decline under Peter Lim's ownership

[edit]

In May 2014, Singaporean businessman Peter Lim was designated by the Fundación Valencia CF as the buyer of 70.4% of the shares owned by the club's foundation.[13][14] After months of negotiations between Lim and Bankia (the main creditor of the club), an agreement was reached in August 2014.[15] Juan Antonio Pizzi was unexpectedly sacked as head coach and replaced by Nuno Espírito Santo on 2 July 2014.[12][16] Later, Salvo revealed in an interview that hiring Nuno was one of the conditions Lim had insisted on when buying the club. This raised eyebrows in the media because of Nuno's close relationship with the football agent Jorge Mendes, whose first-ever client was Nuno.[17][18] Lim and Mendes were also close friends and business partners.[19] Regardless, Nuno's first season was a successful one. Notable signings included Álvaro Negredo, André Gomes and Enzo Pérez, who had just won the Player of the Year in the Portuguese Primeira Liga.[20][21][22] Valencia finished the 2014–15 season in fourth place, achieving Champions League qualification with 77 points, just one point ahead of Sevilla after a dramatic final week where they defeated Granada 4–0.[12][23]

On 2 July 2015, Amadeo Salvo resigned from his post as the executive president of Valencia, citing personal reasons. He was a popular figure among the fans.[24] On 10 August 2015, Nicolás Otamendi was sold to Manchester City for £32 million and Aymen Abdennour was signed from Monaco for £22 million as his replacement.[25][26] Valencia defeated Monaco in the Champions League play-off round with a 4–3 aggregate victory.[27] However, Valencia had a poor start to the 2015–16 league season, winning only five out of thirteen matches and failing to progress from the Champions League group stage. The fans were also increasingly concerned about the growing influence of Jorge Mendes in the club's activities.[28] On 29 November, Nuno resigned as manager and former Manchester United defender Gary Neville was hired as his replacement on 2 December.[29][30] Valencia went winless for nine matches before earning their first win under Neville in a 2–1 victory at home against Espanyol.[31] On 30 March 2016, Neville was sacked after recording the lowest win percentage in La Liga history for a Valencia manager with minimum of five matches, winning just three out of sixteen games. He was replaced by Pako Ayestarán, who had been brought in by Neville as the assistant coach just one month prior.[32][33] Valencia finished the season in twelfth place.

In the summer of 2016, André Gomes and Paco Alcácer were both sold to Barcelona and Shkodran Mustafi was sold to Arsenal, while Ezequiel Garay and former Manchester United player Nani were brought in.[34][35][36][37][38] Pako Ayestarán was sacked on 21 September 2016 after four straight defeats at the beginning of the 2016–17 season. Former Italy national team head coach Cesare Prandelli was hired as his replacement on 28 September.[39] However, he resigned after just three months on 30 December, claiming the club had made him false transfer promises.[40] Days later, on 7 January 2017, Valencia sporting director Jesús García Pitarch also resigned, saying he felt like he was being used as a shield for criticism by the club and that he could not defend something he no longer believed in.[41][42] Voro was named caretaker manager for the fifth time until the end of season, with Valencia in 17th position and in danger of relegation.[43] However, results improved under Voro and he steered Valencia clear off relegation, ultimately finishing the season in 12th place.[44] On 27 March, Mateu Alemany was named the new director general of Valencia.[45]

The club also announced club president Lay Hoon Chan had submitted her resignation and that she would be replaced by Anil Murthy.[46] After rumors arose of Lim's attempts at selling the club, Murthy assured the fans and local media that Valencia was a long-term project for both him and Lim, and they would not consider selling the club.[47][48] For the following season, former Villarreal coach Marcelino was named the new manager on 12 May.[49]

After a successful first season under Marcelino, the club secured fourth place in La Liga and a return to the Champions League. In Marcelino's second season, Valencia again finished fourth and also reached the semi-finals of the UEFA Europa League. On 25 May 2019, Valencia won the Copa del Rey, their first trophy since 2008, upsetting league winners Barcelona 2–1 in the final.[50]

Both Marcelino and sporting director Mateu Alemany, who were credited as the architects of this success,[51] were fired on 11 September 2019 after the former publicly criticized Lim.[51] He was replaced by the ultimately unsuccessful Albert Celades, who was sacked due to poor results, while sporting director César Sánchez resigned that same season,[51] making it six different managers and another six sporting directors by 2020.[52]

For the 2020–21 season, manager Javi Gracia was hired. He was put in charge of a team full of prospects and reserves after the club failed to sign any players during the summer transfer window,[53] but sold key players such as captain Dani Parejo.[54] Local wonderkid Ferran Torres was also sold to Manchester City for a price deemed half his market value.[5] Overall, Valencia sold players worth 85 million euros in order to rebalance the club's books.[55] At the beginning of the season, the club was unable to pay the salaries to the remaining players.[56] After six seasons under Peter Lim's ownership, Valencia had accumulated losses of 323 million euros,[57] In the following years, the playing squad was cut significantly in terms of quality and Lim's ownership has faced strong criticism in Valencia.[5][55][58]

In the 2021–22 season, José Bordalás was hired as head coach, following his five-season tenure with Getafe.[59] Valencia reached the Copa del Rey final final in Bordalás' first season in charge, but lost to Real Betis on penalties following a 1–1 draw.

In June 2022, Anil Murthy left after reportedly insulting the club's owner. Peter Lim's sons became club directors and Lay Hoon Chan returned as the club President.[60]

Stadium

[edit]

Valencia played its first years at the Algirós stadium, but moved to the Mestalla in 1923. In the 1950s, the Mestalla was restructured, which resulted in a capacity increase to 45,000 spectators. Today it holds 49,430 seats, making it the fifth largest stadium in Spain. It is also renowned for its steep terracing and for being one of the most intimidating atmospheres in Europe.[61]

On 20 May 1923, the Mestalla pitch was inaugurated with a friendly match between Valencia and Levante UD.

A long history has taken place on the Mestalla field since its very beginning, when the Valencia team was not yet in the Primera División. Back then, this stadium could hold 17,000 spectators, and at that time, the club started to show its potential in regional championships, which led the managers of the time to carry out the first alterations of Mestalla in 1927. The stadium's total capacity increased to 25,000 before it became severely damaged during the Civil War; the Mestalla was used as a concentration camp and a junk warehouse. It would only keep its structure, since the rest was a lonely plot of land with no terraces and a stand broken during the war. Once the Valencian pitch was renovated, the Mestalla stadium in which the team managed to bring home their first title in 1941.

During the 1950s, the Valencia ground experienced the deepest change in its whole history. That project resulted in a stadium with a capacity of 45,500 spectators, that eventually saw destruction by a flood in October 1957 that arose from the overflowing of the Turia River. Nevertheless, the Mestalla not only returned to normality, but also some more improvements were added, like artificial light, which was inaugurated during the 1959 Fallas festivities.

During the 1960s, the stadium kept the same appearance, while the urban view around it was quickly being transformed. Moreover, the ground held its first European matches, with Nottingham Forest being the first foreign team to play at the Mestalla, on 15 September 1961.

From 1969, the expression "Anem a Mestalla" ("Let's go to the Mestalla"), so common among the supporters, began to fall into oblivion. The reason of this was due to a proposed name change of the stadium to honor Luis Casanova Giner, the club's most successful president. Giner admitted he was completely overwhelmed by such honour, but requested in 1994 that the original name of Mestalla remained.

In 1972, the head office of the club, located in the back of the numbered terraces, was inaugurated. It consisted of an office of avant-garde style with a trophy hall, which held the founding flag of the club. In the summer of 1973, more goal seats, which meant the elimination of fourteen rows of standing terraces, were added to provide comfort. Club management also considered the possibility of moving the Mestalla from its present location, to land on the outskirts of the town, before deciding against it.

Mestalla also hosted the Spain national football team for the first time in 1925. It was chosen as the national team's group venue when Spain staged the 1982 FIFA World Cup,[62] and at the 1992 Summer Olympics held in Barcelona. All of Spain's matches up to the final were held at Mestalla, as they won Gold.[63] Mestalla has been the setting for important international matches, has held several Cup finals, and has also been the home of Levante. The ground also provided a temporary home for Castellón and Real Madrid for European games due to stadium development.

New stadium

[edit]

The 2008–09 season was due to be the last season at the Mestalla, with the club intending to move to their new 75,000-seater stadium Nou Mestalla in time for the 2009–10 season. However, due to the club being in financial crisis, work on the new stadium has been heavily delayed.[64] On 10 January 2025, it was reported that construction for Nou Mestalla has resumed and is set to be completed prior to the 2027–28 season.[65]

Club identity

[edit]Kit

[edit]Originally, Valencia's kit was composed of white shirts, black shorts and socks of the same colour. Through the years, however, these colours have alternated between white and black. The away kit has been shades of orange in recent years while third alternate kits have featured colors from the club crest—yellow, blood orange and blue.

| From 1980 to present | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period | Kit manufacturer | Shirt sponsor (Front) | Shirt sponsor (Back) | Shirt sponsor (sleeve) | Shorts sponsor |

| 1980–1982 | Adidas | None | None | None | None |

| 1982–1985 | Ressy | ||||

| 1985–1990 | Rasan | Caja Ahorros Valencia | |||

| 1990–1992 | Puma | ||||

| 1992–1993 | Mediterránia | ||||

| 1993–1994 | Luanvi | ||||

| 1994–1995 | Cip | ||||

| 1995–1998 | Ford | ||||

| 1998–2000 | Terra Mítica | ||||

| 2000–2001 | Nike | ||||

| 2001–2002 | Metrored | ||||

| 2002–2003 | Terra Mítica | ||||

| 2003–2004 | Toyota / Panasonic Toyota Racing | ||||

| 2004–2007 | |||||

| 2007–2008 | |||||

| Compac Encimeras | Canal Nou | ||||

| Valencia Experience | |||||

| 2008–2009 | |||||

| 2009–2011 | Kappa | Unibet | None | None | |

| 2011–2014 | Joma | Jinko Solar | |||

| 2014–2015 | Adidas | None | Gol Televisión/beIN Sports | ||

| 2015–2016 | Codere | ||||

| 2016–2017 | None | ||||

| 2017–2019 | BLU Products | Sesderma | Alfa Romeo | ||

| 2019–2021 | Puma | bwin | Libertex | Sailun Tyres | Škoda |

| 2021–2022 | SOCIOS.com | Samtrade FX | |||

| 2022–2023 | Cazoo | Herrero Brigantina | |||

| 2023–present | TM Real Estate Group[66] | None | Divina Seguros | ||

The team have also attracted smaller, local sponsors over the years. One example is Lamiplast, a Valencia-based furniture company.

Anthem

[edit]To celebrate the club's 75th anniversary the then president Arturo Tuzón commissioned Pablo Sánchez Torella to compose an anthem for the club. This was a pasodoble whose lyrics were later written by Ramón Gimeno Gil in the Valencian language. The anthem had its official presentation on the anniversary of the club on 21 September 1993.

Crest

[edit]

Valencia and the Balearic Islands were conquered by King James I of Aragon during the first half of the 13th century. After the conquest, the King gave them the status of independent kingdoms of whom he was also the king (but they were independent of Aragonese laws and institutions). The arms of Valencia show those of James I.

The unique crowned letters "L" besides the shield were granted by Peter IV. The reason for the letters was that the city had been loyal twice to the King, hence twice a letter "L" and a crown for the king.

There are several possible explanations for the bat; one is that bats are simply quite common in the area. The second theory is that on 9 October 1238, when James I was about to enter the city, re-conquering it from the Moors, a bat landed on the top of his flag, which he interpreted as a good omen. Following his victory, the bat were then added to the coat of arms.

In May 2013, it was reported that DC Comics had started a legal case against the club, claiming that the new bat image design was too similar to Batman.[67] The club issued a statement clarifying that it had intended to use a revised version of its bat logo for a line of casual clothing and applied for permission from the Office of Harmonisation of the Internal Market but the application was dropped after DC Comics filed an objection, not a lawsuit.[68] DC Comics again filed a complaint with the EU's office of IP opposing the trademark application made by Valencia for its centennial logo, claiming there is likely to be confusion with its Batman’s symbol.[69]

Players

[edit]Current squad

[edit]- As of 2 September 2025[70]

Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules; some limited exceptions apply. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

|

Reserve team

[edit]Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules; some limited exceptions apply. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

|

Out on loan

[edit]Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules; some limited exceptions apply. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

|

Coaching staff

[edit]| Current technical staff | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position | Staff | ||||||||||||||||

| Technical director | |||||||||||||||||

| Head coach | |||||||||||||||||

| Assistant head coach | |||||||||||||||||

| Field assistant coach | |||||||||||||||||

| Goalkeeping coach | |||||||||||||||||

| Team Manager | |||||||||||||||||

| Fitness coach | |||||||||||||||||

| Analyst | |||||||||||||||||

| Assistant fitness coach | |||||||||||||||||

| Assistant goalkeeping coach | |||||||||||||||||

| Chief of medical services | |||||||||||||||||

| Delegate | |||||||||||||||||

| Chief of kit man | |||||||||||||||||

Last updated: 28 December 2024

Source: Valencia CF

Notable coaches

[edit]| The following coaches have all won at least one major trophy when in charge of the club | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Period | Total | ||||||||||||

| Domestic | International | |||||||||||||

| LL | CdR | SC | UCL | UCWC | UEL | UIC | USC | |||||||

| 1939–42 | 2 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | – | |||||

| 1943–46 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | – | |||||

| 1946–48 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | – | |||||

| 1948–54 | 3 | - | 2 | 1 | - | - | - | - | – | |||||

| 1960–62 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | – | |||||

| 1962–63 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | – | |||||

| 1966–68 | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | – | |||||

| 1970–74, 1979–80, 1986–88 | 2 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | – | |||||

| 1979, 1980–82 | 2 | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | |||||

| 1997–99, 2004–05 | 3 | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 1999–01 | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | – | |||||

| 2001–04 | 3 | 2 | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | – | |||||

| 2007–08 | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | – | |||||

| 2017–19 | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | – | |||||

| Total | 1919– | 23 | 6 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | ||||

LL. = La Liga; CdR = Copa del Rey; SC = Supercopa de España; UCL = UEFA Champions League; UCWC = UEFA Cup Winners' Cup; UEL = UEFA Europa League; UIC = UEFA Intertoto Cup; USC = UEFA Super Cup

Gallery

[edit]-

Alejandro Scopelli, the first foreigner to win a trophy with Valencia, the 1962 Fairs Cup.

-

Alfredo Di Stéfano had three successful spells as coach of the club.

-

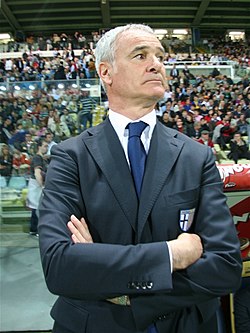

Claudio Ranieri coached Valencia on two occasions with mixed success.

-

Héctor Cúper tenure saw the club rise back to prominence in European football.

-

Rafael Benítez, Valencia's most successful coach, with two league titles and one UEFA Cup over the period of three years

Presidents

[edit]

|

|

|

Player records

[edit]

| Rank | Player | Nationality | Apps | Years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fernando | 556 | 1983–1998 | |

| 2 | Ricardo Arias | 521 | 1976–1992 | |

| 3 | David Albelda | 485 | 1995–2013 | |

| 4 | Miguel Ángel Angulo | 434 | 1996–2009 | |

| 5 | Manuel Mestre | 424 | 1956–1969 | |

| 6 | Santiago Cañizares | 416 | 1998–2008 | |

| 7 | Enrique Saura | 400 | 1975–1985 | |

| 8 | Dani Parejo | 383 | 2011–2020 | |

| 9 | José Gayá | 376 | 2012–present | |

| 10 | José Claramunt | 375 | 1966–1978 |

| Rank | Player | Nationality | Goals | Years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mundo |

238 |

1939–1950 | |

| 2 | Waldo Machado | 160 | 1961–1970 | |

| 3 | Mario Kempes | 149 | 1976–1981 1982–1984 | |

| 4 | Fernando | 143 | 1983–1998 | |

| 5 | David Villa | 130 | 2005–2010 | |

| 6 | Silvestre Igoa | 117 | 1941–1950 | |

| 7 | Manuel Badenes | 102 | 1950–1956 | |

| 8 | Vicente Seguí | 91 | 1946–1959 | |

| 9 | Luboslav Penev | 88 | 1989–1995 | |

| 10 | Epi Fernández | 87 | 1940–1949 |

Transfers

[edit]

| Record transfer fees paid by Valencia | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Player | Fee (€) | Paid to | Date | ||||||||||

| 1 | 40,000,000 | 2018 | ||||||||||||

| 2 | 35,000,000 | 2019 | ||||||||||||

| 3 | 30,000,000 | 2015 | ||||||||||||

| 4 | 28,000,000 | 2014 | ||||||||||||

| 5 | 25,000,000 | 2006 | ||||||||||||

| 2015 | ||||||||||||||

| 2018 | ||||||||||||||

| 8 | 24,000,000 | 2001 | ||||||||||||

| 9 | 22,000,000 | 2015 | ||||||||||||

| 10 | 20,000,000 | 2016 | ||||||||||||

| Record transfer fees received by Valencia | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pos. | Player | Fee (€) | Received from | Date | ||||||||||

| 1 | 48,000,000 | 2001 | ||||||||||||

| 2 | 45,000,000 | 2015 | ||||||||||||

| 3 | 41,500,000 | 2022 | ||||||||||||

| 4 | 41,000,000[71] | 2016 | ||||||||||||

| 5 | 40,400,000 | 2018 | ||||||||||||

| 6 | 40,000,000 | 2010 | ||||||||||||

| 7 | 35,000,000 | 2016 | ||||||||||||

| 8 | 33,000,000 | 2010 | ||||||||||||

| 9 | 32,000,000 | 2000 | ||||||||||||

| 10 | 30,000,000 | 2016 | ||||||||||||

| 2013 | ||||||||||||||

Seasons

[edit]- 90 seasons in La Liga

- 4 seasons in Segunda División

Honours

[edit]| Type | Competition | Titles | Seasons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic | La Liga | 6 | 1941–42, 1943–44, 1946–47, 1970–71, 2001–02, 2003–04 |

| Segunda División | 2 | 1930–31, 1986–87 | |

| Copa del Rey | 8 | 1941, 1948–49, 1954, 1966–67, 1978–79, 1998–99, 2007–08, 2018–19 | |

| Supercopa de España | 1 | 1999 | |

| Copa Eva Duarte | 1 | 1949 | |

| Continental | European Cup Winners' Cup | 1 | 1979–80 |

| UEFA Cup | 1 | 2003–04 | |

| European Super Cup/UEFA Super Cup | 2 | 1980, 2004 | |

| Inter-Cities Fairs Cup | 2 | 1961–62, 1962–63 | |

| UEFA Intertoto Cup | 1 | 1998 | |

| Regional | Levante Championship / Valencian Championship | 10 | 1922–23, 1924–25, 1925–26, 1926–27, 1930–31, 1931–32, 1932–33, 1933–34, 1936–37, 1939–40[72] |

Awards & recognitions

[edit]- IFFHS The World's Club Team of the Year: 2004

Valencia CF in international football

[edit]The Academy: Training Centre Foundation Valencia CF

[edit]Since May 2009, Valencia CF has had a training centre, this is the first multidisciplinary training center for a football club in Spain.[73]

The Training Centre Foundation Valencia CF "The Academy" offers university education,[74] classroom training, and online training related to sport and football (soccer).[75]

Valencia CF is one of the few clubs in Spain that organises a Sport Management MBA, the MBA in International Sport Management, currently performs with Valencia Catholic University Saint Vincent Martyr.[76]

On the 90th anniversary of Valencia CF, the academy opened with the University of Valencia the first university course that studied the history of a football club, Valencia CF is the first football club in Spain to be an object of study in college.[77]

Motorsports involvement

[edit]

Valencia CF were also involved in motorsports such as Formula One, Super GT, MotoGP, Moto2, Moto3, 250cc and Formula Nippon. Valencia CF was an official partner of Panasonic Toyota Racing in 2003 until 2008 to commemorate Toyota as their shirt sponsor. Valencia CF also sponsored all Toyota-engined Formula Nippon teams and also Toyota Super GT teams in GT500 and GT300 cars. In 2009, Valencia CF became an official partner of former 250cc team Stop And Go Racing Team and in 2014 of Aspar Team in MotoGP, Moto2 and Moto3 classes, respectively.

Esports involvement

[edit]In June 2016, Valencia opened an esports division with presences in Hearthstone, Rocket League and League of Legends – in the last case, they joined Beşiktaş, Santos, Schalke and PSG in acquiring League teams. They announced their League roster on 13 July, composed mostly of Spanish players, including some with European League of Legends Championship Series (EU LCS) experience.[78]

In November 2020, Valencia CF eSports launched a team on Arena of Valor in Thailand. The team consist of six Thai players, competing in the RoV Pro League competitions. They joined the local club Buriram United FC, and after that, French club Paris Saint-Germain FC in acquiring AoV teams.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]Sources

[edit]- Valencia Club de Fútbol (1919–1969), Bodas de Oro (in Spanish), de José Manuel Hernández Perpiñá. 1969, Talleres Tipográficos Vila, S.L.

- Historia del Valencia F.C. (in Spanish), de Jaime Hernández Perpiñá. 1974, Ediciones Danae, S.A. OCLC 2985617

- La Gran Historia del Valencia C.F. (in Spanish), de Jaime Hernández Perpiñá. 1994, Levante-EMV. ISBN 84-87502-36-9

- DVD Valencia C.F. (Historia Temática). Un histórico en la Liga. (in Spanish), 2003, Superdeporte. V-4342-2003

References

[edit]- ^ "Why are the Valencia players called 'Ches'?". La Liga. Archived from the original on 9 November 2019. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ a b "About Mestalla". Valencia CF. 11 March 2019. Archived from the original on 2 July 2019. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- ^ Valencia CF history in Valencian (named València CF in article) Archived 27 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine,

- ^ EFE (11 November 2008). "El club roza los 50.000 socios tras la nueva campaña de abonos". Superdeporte (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 9 February 2023. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ a b c Baillif, Elias. "Institution bafouée et résistance : Valence est-il (ir)récupérable ?". Eurosport. Archived from the original on 5 March 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ "'An abandoned club' - the staggering decline of Valencia". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 9 February 2023. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ "Stage 26, Primera Division season 2003-2004". www.resultsfromfootball.com. Archived from the original on 29 December 2019. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ^ "Albelda se retira del fútbol profesional". El País. 7 August 2013. Archived from the original on 2 August 2021. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- ^ "Djukic dismissed as Valencia coach". ESPN. 16 December 2013. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ "Antonio Pizzi hired by Valencia". ESPN. 26 December 2013. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ "Last-gasp Sevilla snatch final berth from Valencia". UEFA. 1 May 2014. Archived from the original on 16 September 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ a b c "Valencia sack coach Pizzi, Nuno tipped to take over". UEFA. 2 July 2014. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ "Peter Lim new owner of Valencia". Goal.com. 17 May 2014. Archived from the original on 22 August 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ^ "Singapore businessman Peter Lim buys Valencia". Today. 17 May 2014. Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ^ "Lim a signature away from Valencia takeover". Marca. Archived from the original on 16 August 2014. Retrieved 17 August 2014.

- ^ "Nuno takes up Valencia coaching reins". The Daily Telegraph. 3 July 2014. Archived from the original on 16 September 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ "Amadeo Salvo: "Si no viene Nuno, Lim no hubiera comprado el club"". 10 February 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Valencia sack coach Pizzi, Nuno tipped to take over". The Guardian. 22 September 2014. Archived from the original on 2 December 2016. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ "Lim y Mendes participan en un fondo que compra y vende jugadores". 19 January 2014. Archived from the original on 14 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ "Official VCF Announcement – Álvaro Negredo". Valencia CF. 2 September 2014. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ "Presentación oficial de Enzo Pérez como nuevo jugador del Valencia CF" [Official presentation of Enzo Pérez as new player of Valencia CF] (in Spanish). Valencia CF. 2 January 2015. Archived from the original on 3 January 2015. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ "Valencia regista André Gomes como emprestado pelo Benfica" [Valencia register André Gomes as loaned by Benfica]. Record (in Portuguese). 17 July 2014. Archived from the original on 20 July 2014. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- ^ "Valencia climb back above Sevilla in battle for fourth". Eurosport. 27 April 2015. Archived from the original on 17 April 2024. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ "Nani: Valencia sign former Man Utd winger on three-year deal". 5 July 2016. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 5 July 2016."Valencia president Salvo resigns as five members of staff depart".

- ^ "Nicolas Otamendi: Manchester City sign £32m Argentina defender". BBC Sport. 20 August 2015. Archived from the original on 21 August 2015. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ^ "Valencia sign Aymen Abdennour from Monaco". BBC. 29 August 2015. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ^ "Valencia become fifth Spanish team in Champions League". Eurosport. 26 August 2015. Archived from the original on 27 March 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ^ "How Jorge Mendes pulls Los Che strings". Sport 360. 10 November 2015. Archived from the original on 20 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ "Valencia: Nuno Espirito Santo resigns as coach at Spanish club". BBC. 29 November 2015. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ^ "Gary Neville appointed Valencia head coach until end of season". The Guardian. 2 December 2015. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ "Valencia 2–1 Espanyol". BBC Sport. 13 February 2016. Archived from the original on 14 February 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- ^ "Gary Neville's terrible record at Valencia in full". Goal. 30 March 2016. Archived from the original on 29 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ "Gary Neville sacked by Valencia after failing to turn fortunes around". ESPN. 30 March 2016. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ "Andre Gomes: Barcelona agree deal to sign Valencia midfielder". BBC Sport. 21 July 2016. Archived from the original on 16 March 2023. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ "Paco Alcácer signs for FC Barcelona". FC Barcelona. 30 August 2016. Archived from the original on 30 August 2016. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ^ "VCF official statement | Ezequiel Garay". Valencia CF. 31 August 2016. Archived from the original on 10 September 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^ "Shkodran Mustafi signs for Arsenal". Arsenal's official website. Archived from the original on 1 September 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^ "Nani: Valencia sign former Man Utd winger on three-year deal". British Broadcasting Corporation. 5 July 2016. Archived from the original on 8 July 2016. Retrieved 5 July 2016."Nani: 'United contract could have been best moment of my life – but it turned into the worst'". The Guardian. 17 August 2016. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- ^ "Struggling Valencia appoint Cesare Prandelli as new coach". As.com. 28 September 2016. Archived from the original on 1 October 2016. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- ^ "Cesare Prandelli quit Valencia over broken transfer promises". ESPN. 4 January 2017. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ "Valencia's Garcia Pitarch resigns & is replaced by Alexanko". sport-english. 7 January 2017. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ "García Pitarch: "Me he sentido como un paraguas"". epdeportes.es. 10 January 2017. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ "Voro takes Valencia helm again after Cesare Prandelli resigns". La Liga. 30 December 2016. Archived from the original on 4 January 2017. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ^ "VORO CONFIRMS HE IS TO BE REPLACED AS VALENCIA COACH". 6 May 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "DEPORTeS Mateu Alemany, nuevo director general del Valencia CF". elmundo.es. 27 March 2017. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ "Layhoon Chan to step down as president of Valencia". ESPN. 10 April 2017. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ "Owner Peter Lim 'would not sell Valencia for €1bn' – Anil Murthy". ESPN. 11 April 2017. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ "New Valencia president Anil Murthy vows to rebuild club for years to come – Anil Murthy". 3 July 2017. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ "Valencia name Marcelino Garcia Toral as sixth boss in two years". todayonline. 12 May 2017. Archived from the original on 19 June 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ^ "Valencia shock Barcelona in Copa del Rey final despite Messi's best efforts". The Guardian. 25 May 2019. Archived from the original on 10 June 2019. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ^ a b c "Lim's fortune rescued Valencia, but his missteps and assertion of authority is tearing them apart". ESPN. 10 July 2020. Archived from the original on 13 February 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ "Chaos reigns at Valencia as coach is sacked, sporting director quits". The Indian Express. 30 June 2020. Archived from the original on 13 February 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ "Valencia coach Gracia staying after offering resignation". Reuters. 8 October 2020. Archived from the original on 31 January 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ "Pressure on Peter Lim as Valencia sell Coquelin and Parejo to Villarreal". The Guardian. 12 August 2020. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ a b Panja, Tariq (5 February 2021). "They Hailed the New Owner as a Savior. Then They Got to Know Him". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 28 December 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ "Valencia, unable to pay players' wages, offer promissory notes". AS. 17 August 2020. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ "Peter Lim, dueño y prestamista del Valencia". El Mundo (in Spanish). 11 December 2020. Archived from the original on 13 February 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ Corrigan, Dermot. "'He had everything. And he destroyed it': Peter Lim's six years at Valencia". The Athletic. Archived from the original on 13 February 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ "Valencia Club de Fútbol". Valencia CF. Archived from the original on 26 October 2021. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ^ Kwek, Kimberly (20 August 2022). "Football: Chan Lay Hoon appointed Valencia president again, replaces Anil Murthy". The Straits Times. ISSN 0585-3923. Archived from the original on 9 April 2024. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ Toby Davis, "XI at 11: Great European Grounds[permanent dead link]", Setanta Sports, 23 April 2008. (in English)

- ^ "World Cup 1982 finals". RSSSF. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ^ "Football Tournament 1992 Olympiad". RSSSF. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ^ "World Soccer 5 April 2009". Archived from the original on 8 April 2009.

- ^ "Valencia CF to resume Nou Mestalla construction, targeting 2027 move". Página web oficial de LALIGA | LALIGA. Retrieved 14 January 2025.

- ^ "TM Real Estate Group becomes Valencia CF's Main Global Partner and Real Estate Partner - Valencia CF". www.valenciacf.com. Retrieved 4 August 2025.

- ^ Keegan, Mike (21 November 2014). "Holy Trademark! Batman creators DC take on Valencia over logo". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 21 November 2014. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ "Club Statement — DC Comics". Valencia CF. 25 November 2014. Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- ^ Azzoni, Tales (21 March 2019). "Valencia again targeted by Batman creators for bat logo". AP NEWS. Archived from the original on 18 April 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- ^ "PRIMER EQUIPO". valenciacf.com. Retrieved 9 September 2025.

- ^ Arsenal sign Mustafi for €41m Archived 12 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Marca, 30 August 2016

- ^ Spain - List of Champions of Levante - Campeonato Regional de Levante, Carles Lozano Ferrer, RSSSF, 25 October 2018

- ^ "Valencia Club de Fútbol". www.valenciacf.com. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012.

- ^ "Nostresport - Todo el deporte de Alicante, Castellón, Valencia". nostresport.com. Archived from the original on 17 December 2011.

- ^ "The Academy te entrena on line". www.levante-emv.com. 14 October 2010. Archived from the original on 29 December 2019. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ^ "Archidiocesis de Valencia". www.archivalencia.org. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 12 April 2012.

- ^ "Federaciones miembro - España - Noticias". UEFA. 10 November 2009. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 12 April 2012.

- ^ El Valencia CF eSports presenta su equip de League of Legends (Spanish) Archived 1 February 2022 at the Wayback Machine Valencia CF

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Valencia CF at the Wayback Machine (archived 17 June 2015)

- Valencia CF at UEFA

Valencia CF

View on GrokipediaHistory

Foundation and early years (1919–1939)

Valencia CF was founded on March 18, 1919, when a group of local football enthusiasts, including Gonzalo Medina, Octavio Augusto Milego Díaz, Fernando Marzal, and Andrés Bonilla, formalized the club's creation at a meeting in the Bar Torino in central Valencia.[1] This establishment effectively merged efforts from several amateur groups and extinct city teams, marking the birth of a unified professional entity dedicated to football and other sports.[6] Octavio Augusto Milego Díaz served as the club's first president, overseeing the initial organizational steps that positioned Valencia as a key player in the region's burgeoning football scene.[1] The club's inaugural match occurred on May 21, 1919, away at Castellón against Gimnástico FC, resulting in a 1-0 defeat, with the lineup featuring players such as Marco, Peris, Julio Gascó, and Marzal.[1] Home games began at the Camp d'Algirós ground, inaugurated on December 7, 1919, where Valencia honed its early competitive edge.[1] By 1923, the club had acquired the Mestalla site for 316,439 pesetas under president Ramón Leónarte, opening the stadium on May 20, 1923, which provided a permanent base for growing ambitions.[1] During this period, Valencia participated in the Campeonato Regional Valenciano, securing its first regional title on February 25, 1923, which qualified the team for its debut in the Copa de España that year.[1] Administrative advancements solidified the club's professional trajectory in 1928, when it joined the Segunda División for the 1928-29 season, with the first league match on February 17, 1929, yielding a 4-2 victory over Real Oviedo.[1] Promotion to La Liga followed in 1931 after a strong second-division campaign, reflecting the club's evolution from regional contender to national participant.[1] Key figures like Eduardo Cubells, the first Valencia player to earn an international cap for Spain in 1922, exemplified the emerging talent pool that drove early successes.[1] The Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) presented severe challenges, disrupting operations as many players departed and the military influenced club affairs, while Mestalla suffered damage from bombings.[1] Under the leadership of Josep Rodríguez Tortajada, Valencia maintained social and sporting activities amid the turmoil, though rumors of potential disbandment circulated due to the instability.[1] Despite these hardships, the club endured, preserving its structure for the post-war period.[1]Post-war emergence and domestic dominance (1940s)

Following the Spanish Civil War, which ended in 1939 and left Mestalla Stadium damaged by bombings, Valencia CF underwent significant recovery efforts under new leadership. President Luis Casanova, appointed in 1943, oversaw post-war renovations that expanded the stadium's capacity to around 25,000 spectators in the early 1940s, enabling the club to host larger crowds and solidify its position in La Liga.[7] This post-war resurgence marked the beginning of Valencia's emergence as a domestic powerhouse, with the club adapting to professional football's growing demands while promoting youth development. Valencia secured its first La Liga title in the 1941–42 season under coach Ramón "Moncho" Encinas, finishing with 19 wins, 4 draws, and 7 losses, scoring a league-high 85 goals.[1] The team repeated this success in 1943–44, guided by Eduardo Cubells, and claimed a third title in 1946–47 under Luis Casas Pasarín, clinching the latter on goal difference after a 6–0 victory over Sporting de Gijón.[8][9] These achievements were driven by the formidable "delantera eléctrica" forward line—featuring Epifanio Fernández "Epi," Antonio Puchades, Edmundo "Mundo" Suárez, Vicente Asensi, and Guillermo Gorostiza—who combined speed, skill, and prolific scoring, with Mundo netting 27 goals in the inaugural title campaign alone.[10][1] Suárez, a Barakaldo native and Valencia's all-time leading scorer with 266 goals, exemplified the era's attacking prowess.[11] Despite league dominance, Valencia endured heartbreak in the Copa del Rey, losing three consecutive finals from 1944 to 1946—all at Barcelona's Montjuïc Olympic Stadium, which fans dubbed a "jinx" venue—making the club the only Spanish side to suffer such a streak in the competition's history.[1] These defeats, to Athletic Bilbao (3–1 in 1944) and Real Madrid (twice, 2–1 in 1945 and 3–1 in 1946), intensified emerging rivalries with those clubs, highlighted by fierce league clashes that underscored Valencia's rise against Spain's traditional giants.[1] The decade closed with a 1949 Copa del Rey triumph, capping a period of sustained domestic contention.[12]European breakthroughs (1960s)

Valencia CF entered European competition for the first time in the 1961–62 Inter-Cities Fairs Cup, a tournament organized for clubs from cities hosting international trade fairs, with the club qualifying as Valencia's representative following their strong domestic performances in prior decades. Under the guidance of coach Alejandro Scopelli, the team navigated a challenging path, eliminating Nottingham Forest, Lausanne-Sport, and Hibernian before reaching the final against domestic rivals FC Barcelona. In the two-legged final, Valencia secured a commanding 6–2 victory in the first leg at Mestalla Stadium on September 8, 1962, thanks to goals from Waldo Machado (two), Vicente Guillot, and others, before drawing 1–1 in the return leg at Camp Nou on September 12, 1962, to win 7–3 on aggregate and claim their inaugural European trophy. Waldo, the Brazilian striker who became the club's all-time leading scorer with 157 goals during his tenure, and Guillot, his seamless midfield partner who provided precise support in attack, were instrumental in this breakthrough, exemplifying the squad's blend of technical skill and resilience.[1][13] The following season, 1962–63, Valencia defended their Fairs Cup title under new coach Milan Antolkovic, becoming only the second club after Barcelona to retain the competition. They progressed by overcoming Dunfermline Athletic in a playoff after a 6–6 aggregate draw, followed by victories over Austria Wien, Union Saint-Gilloise, and Birmingham City, culminating in the final against Dinamo Zagreb. Valencia triumphed 2–1 in the first leg away on June 23, 1963, with goals from Waldo and Enrique Urtiaga, then sealed the 4–1 aggregate win with a 2–0 home victory on June 26, 1963, scored by Ricardo Mañó and Héctor Núñez. This back-to-back success highlighted the tactical discipline instilled by Antolkovic, who emphasized a balanced approach leveraging the speed of forwards like Waldo and the defensive solidity of players such as José Sanchis in goal and Vicente Piquer at the back.[1][14] Despite these continental triumphs, La Liga form remained inconsistent, with a seventh-place finish in 1961–62 and similar mid-table results thereafter, as the club prioritized European campaigns amid a rebuilding phase under president Julio de Miguel, who took office in 1961.[1] Domestically, the 1960s saw Valencia secure their seventh Copa del Rey in 1966–67, ending a 13-year wait for major silverware, with a 2–1 final win over Athletic Bilbao on July 2, 1967, at Santiago Bernabéu Stadium; goals from José Jara and Paquito García proved decisive against a strong Basque side. This victory, achieved through a squad featuring emerging talents like Pepe Claramunt and Juan Cruz Sol alongside veterans, provided a morale boost amid ongoing La Liga struggles, where the team hovered around mid-table positions. The European breakthroughs of the early 1960s, rooted in the domestic dominance established in the 1940s, significantly elevated the club's prestige, transforming Valencia from a regional powerhouse into a recognized European contender and attracting greater international attention to Mestalla Stadium. These achievements laid the groundwork for future successes, underscoring the club's ability to compete at the highest levels despite fluctuating league performances.[1]Renewed success and challenges (1970s–1980s)

The 1970s marked a period of renewed domestic success for Valencia CF, culminating in their second La Liga title during the 1970–71 season. Under the guidance of coach Alfredo Di Stéfano, who had joined the club earlier that year, Valencia secured the championship on the final day of the campaign with a 4–0 victory over Granada CF, despite a concurrent loss in another match that initially threatened their position.[15] This triumph, achieved with a squad featuring key contributors like midfielders José Claramunt and Enrique Vidal, ended a 24-year league drought and qualified the club for the European Cup for the first time. Building on this momentum, Valencia experienced a surge in European competition during the late 1970s. The team, coached by Di Stéfano until 1974 and later by figures such as Pasieguito, advanced through domestic cups to reach the 1978–79 Copa del Rey final, which they won 2–1 against Real Madrid.[16] This victory propelled them into the 1979–80 European Cup Winners' Cup, where they defeated Barcelona in the semifinals before overcoming Arsenal FC 5–4 on penalties in the final at Heysel Stadium, claiming their first major European trophy. Players like forward Mario Kempes, who scored crucial goals, and skillful midfielder Daniel Solsona, who contributed eight goals in the 1978–79 La Liga season, were instrumental in this glory era, embodying the technical flair that defined the squad.[1] The following year, Valencia capitalized on their European success by winning the 1980 UEFA Super Cup against Nottingham Forest. In a two-legged tie, Valencia drew 1–1 at home and won 1–0 away, advancing on away goals thanks to a Fernando Morena strike, thus completing a rare continental double for a Spanish club at the time.[17] These achievements in the late 1970s elevated Valencia's profile, fostering growing fan support at Mestalla Stadium, where attendance figures rose significantly during title-winning campaigns, laying the groundwork for organized supporter groups. However, the 1980s brought stagnation and challenges, exacerbated by frequent managerial changes that disrupted team stability. After Di Stéfano's departure in 1982, coaches like Milorad Pavić, Alfredo Arias, and Otto Glória cycled through the role between 1983 and 1985, with none able to replicate prior success amid inconsistent league performances.[16] Financial difficulties intensified under president Vicente Tormo, leading to mounting debts from poor transfer dealings and operational costs, which forced the sale of key assets and weakened the squad.[12] This culminated in relegation from La Liga at the end of the 1984–85 season, as Valencia finished 20th in the table with only 18 points from 34 matches.[18] In the Segunda División, Valencia endured a turbulent 1985–86 campaign marked by further instability, but recovery came swiftly in 1986–87 under Di Stéfano's return as coach. Leading a revitalized side blending youth academy talents like Fernando Giner and veterans such as goalkeeper José Sanchis, the team secured promotion as champions with 58 points, returning to the top flight after one year.[19] Amid these ups and downs, fan loyalty deepened, with the formation of ultras groups such as Ultras Yomus in 1983 symbolizing the emergence of passionate, organized support that would define Valencia's terrace culture in subsequent decades.[20]Revival under new ownership (1990s)

The early 1990s marked a pivotal period of stabilization for Valencia CF following years of financial instability and inconsistent performance, as the club transitioned into a Sociedad Anónima Deportiva (SAD) in 1992, allowing for structured shareholding and improved economic governance.[21] This restructuring was overseen by president Arturo Tuzón, who had assumed leadership in the late 1980s after the club's relegation crisis, emphasizing debt reduction and long-term planning.[1] A key initiative under Tuzón was the inauguration of the Paterna Sports City in 1992, a modern training facility that enhanced youth integration by providing dedicated infrastructure for the club's academy, fostering talents who would soon break into the first team. Francisco Roig's election as president in March 1994 injected fresh capital through a significant share increase, further solidifying the club's finances and enabling strategic investments in the squad.[1] Under Roig and subsequent leadership, including Pedro Cortés who took over in December 1997, Valencia achieved consistent top-half finishes in La Liga throughout the decade, such as second place in 1995–96 and third in 1997–98, reflecting a return to competitiveness after mid-table struggles earlier in the 1990s.[22] Coaches like Guus Hiddink (1991–1994), Luis Aragonés (1995–1996), and Claudio Ranieri (1997–1998) played crucial roles in this revival, implementing disciplined tactics that maximized the potential of emerging homegrown players. The decade culminated in Valencia's first major trophy in 21 years with the 1998–99 Copa del Rey victory, defeating Atlético Madrid 3–0 in the final on June 26, 1999, at Seville's Estadio Olímpico.[23] This success, under Héctor Cúper's guidance from 1998, was powered by key figures including midfielder Gaizka Mendieta, who debuted in 1992 and became a creative linchpin, and forward Claudio López, whose pace and goals earned him the nickname "El Gato." The triumph, alongside a third-place La Liga finish in 1999–2000, secured the club's first Champions League qualification, positioning Valencia for greater European ambitions in the new millennium.[22]Golden era at the top (2000s)

The 2000s marked Valencia CF's most triumphant decade, characterized by sustained domestic and European excellence under strategic leadership and a talented squad. Following the foundations laid in the late 1990s, the club reached the UEFA Champions League final in 2000 against Real Madrid at the Stade de France, where they lost 3-0 on penalties after a 0-0 draw, managed by Héctor Cúper. The following year, under the same coach, Valencia returned to the final at the San Siro, drawing 1-1 with Bayern Munich before falling 5-4 in penalties, establishing them as a European powerhouse.[24] Cúper's tenure transitioned to Rafael Benítez in June 2001, who guided Valencia to their first La Liga title in 31 years during the 2001–02 season, clinching the championship with a 4-2 victory over Real Madrid on the final day.[25] Benítez's tactical acumen, emphasizing defensive solidity and quick counterattacks, propelled the team to another La Liga triumph in 2003–04, secured with a 1-0 win against Barcelona and confirmed by a 2-0 victory over Sevilla.[26] That same season, Valencia captured the UEFA Cup, defeating Marseille 2-0 in the final at the Ullevi Stadium in Gothenburg, with goals from Vicente and Mista. Their European success continued with a 2-1 victory over Porto in the 2004 UEFA Super Cup at the Stade Louis II, thanks to late strikes from Bernardo Corradi and Mohamed Sissoko.[27] Central to this golden era was president Jaume Ortí, who assumed office in July 2001 and oversaw the two La Liga titles and the UEFA Cup win before resigning in October 2004 amid internal pressures.[28] Key players included midfielder Gaizka Mendieta, whose versatility and set-piece expertise were pivotal in the early Champions League runs before his departure in 2001; Argentine playmaker Pablo Aimar, who joined in 2001 and provided creative flair with 27 goals in 162 appearances, contributing to both league titles and the UEFA Cup; and captain David Albelda, whose leadership in midfield anchored the team through multiple trophy campaigns.[29] As the decade progressed, Valencia announced ambitious infrastructure plans, with president Juan Bautista Soler unveiling the Nou Mestalla project in June 2006—a 75,000-capacity stadium designed by Mark Fenwick and Francisco Candela—to replace the aging Mestalla and support ongoing competitiveness.[30]Financial struggles and transition (2010–2019)

The early 2010s marked a period of severe financial distress for Valencia CF, exacerbated by the broader economic crisis in Spain. By 2013, the club's debt had ballooned to over €400 million, prompting urgent measures to ensure solvency.[31] This financial strain led to the sale of key players, including David Silva to Manchester City in 2010 for approximately €30 million and Juan Mata to Chelsea in 2011 for €27 million, as the club prioritized debt repayment over squad retention.[32] These transfers, while injecting vital funds, depleted the team's talent pool and contributed to inconsistent performances on the pitch.[33] In response to the escalating crisis, Amadeo Salvo assumed the role of club president in June 2013, focusing on stabilizing operations amid ongoing negotiations with creditors.[34] Under his leadership, Valencia achieved a degree of financial and competitive steadiness, finishing eighth in La Liga during the 2013–14 season and securing a spot in the UEFA Europa League.[35] The club also participated in the Champions League group stage in the 2012–13 campaign, finishing third in their group before dropping into the Europa League, where they advanced to the round of 32.[36] Salvo's tenure emphasized prudent management, including the sacking of manager Miroslav Đukić in December 2013 to refocus the squad.[37] The period culminated in a significant ownership transition in 2014, when Singaporean businessman Peter Lim acquired a 70.4% controlling stake in the club for €94 million in October, following months of negotiations.[38] Lim's arrival brought initial investments, enabling signings such as Nicolás Otamendi and André Gomes, and the appointment of Nuno Espírito Santo as manager in July 2014 on a three-year contract.[39] Under Nuno, Valencia mounted a strong resurgence in the 2014–15 season, reaching the Europa League round of 32 where they fell to Bayer Leverkusen 3–2 on penalties after a 1–1 aggregate, and finishing fourth in La Liga to qualify for the Champions League group stage in 2015–16.[40] However, early signs of fan discontent emerged due to perceived austerity measures and the club's shift toward a more commercial model, despite the on-field progress.[26]Ownership controversies and recent performance (2020–present)