Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Optical illusion

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2025) |

In visual perception, an optical illusion (also called a visual illusion[2]) is an illusion caused by the visual system and characterized by a visual percept that arguably appears to differ from reality. Illusions come in a wide variety; their categorization is difficult because the underlying cause is often not clear[3] but a classification[1][4] proposed by Richard Gregory is useful as an orientation. According to that, there are three main classes: physical, physiological, and cognitive illusions, and in each class there are four kinds: Ambiguities, distortions, paradoxes, and fictions.[4] A classical example for a physical distortion would be the apparent bending of a stick half immersed in water; an example for a physiological paradox is the motion aftereffect (where, despite movement, position remains unchanged).[4] An example for a physiological fiction is an afterimage.[4] Three typical cognitive distortions are the Ponzo, Poggendorff, and Müller-Lyer illusion.[4] Cognitive visual illusions are the result of unconscious inferences and are perhaps those most widely known.[4]

Pathological visual illusions arise from pathological changes in the physiological visual perception mechanisms causing the aforementioned types of illusions; they are discussed e.g. under visual hallucinations.

Optical illusions, as well as multi-sensory illusions involving visual perception, can also be used in the monitoring and rehabilitation of some psychological disorders, including phantom limb syndrome[5] and schizophrenia.[6]

Physical visual illusions

[edit]A familiar phenomenon and example for a physical visual illusion is when mountains appear to be much nearer in clear weather with low humidity (Foehn) than they are. This is because haze is a cue for depth perception,[7] signalling the distance of far-away objects (Aerial perspective).

The classical example of a physical illusion is when a stick that is half immersed in water appears bent. This phenomenon was discussed by Ptolemy (c. 150)[8] and was often a prototypical example for an illusion.

Physiological visual illusions

[edit]Physiological illusions, such as the afterimages[9] following bright lights, or adapting stimuli of excessively longer alternating patterns (contingent perceptual aftereffect), are presumed to be the effects on the eyes or brain of excessive stimulation or interaction with contextual or competing stimuli of a specific type—brightness, color, position, tile, size, movement, etc. The theory is that a stimulus follows its individual dedicated neural path in the early stages of visual processing and that intense or repetitive activity in that or interaction with active adjoining channels causes a physiological imbalance that alters perception.

The Hermann grid illusion and Mach bands are two illusions that are often explained using a biological approach. Lateral inhibition, where in receptive fields of the retina receptor signals from light and dark areas compete with one another, has been used to explain why we see bands of increased brightness at the edge of a color difference when viewing Mach bands. Once a receptor is active, it inhibits adjacent receptors. This inhibition creates contrast, highlighting edges. In the Hermann grid illusion, the gray spots that appear at the intersections at peripheral locations are often explained to occur because of lateral inhibition by the surround in larger receptive fields.[10] However, lateral inhibition as an explanation of the Hermann grid illusion has been disproved.[11][12][13][14][15] More recent empirical approaches to optical illusions have had some success in explaining optical phenomena with which theories based on lateral inhibition have struggled.[16]

Cognitive illusions

[edit]

Cognitive illusions are assumed to arise by interaction with assumptions about the world, leading to "unconscious inferences", an idea first suggested in the 19th century by the German physicist and physician Hermann Helmholtz.[17] Cognitive illusions are commonly divided into ambiguous illusions, distorting illusions, paradox illusions, or fiction illusions.

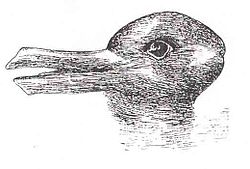

- Ambiguous illusions are pictures or objects that elicit a perceptual "switch" between the alternative interpretations. The Necker cube is a well-known example; other instances are the Rubin vase and the "squircle", based on Kokichi Sugihara's ambiguous cylinder illusion.[18]

- Distorting or geometrical-optical illusions are characterized by distortions of size, length, position or curvature. A striking example is the Café wall illusion. Other examples are the famous Müller-Lyer illusion and Ponzo illusion.

- Paradox illusions (or impossible object illusions) are generated by objects that are paradoxical or impossible, such as the Penrose triangle or impossible staircase seen, for example, in M. C. Escher's Ascending and Descending and Waterfall. The triangle is an illusion dependent on a cognitive misunderstanding that adjacent edges must join.

- Fictions are when a figure is perceived even though it is not in the stimulus, like with the Kanizsa triangle, using illusory contours.[19][20]

Specific examples of typical cognitive illusions include:

- The Ponzo illusion, where two parallel lines of the same length appear to be different sizes due to their placement within converging lines that create a false sense of depth.

- The Poggendorff illusion, where two straight lines partially obsecured by an intervening shape, typically a rectangle, appears misaligned when, in fact, they are collinear.

- The Müller-Lyer illusion, where two lines of the same length appear to be different lengths due to the outward or inward pointing arrow-like fins attached to their ends.[4]

Explanation of cognitive illusions

[edit]Perceptual organization

[edit]

To make sense of the world it is necessary to organize incoming sensations into information which is meaningful. Gestalt psychologists believe one way this is done is by perceiving individual sensory stimuli as a meaningful whole.[21] Gestalt organization can be used to explain many illusions including the rabbit–duck illusion where the image as a whole switches back and forth from being a duck then being a rabbit and why in the figure–ground illusion the figure and ground are reversible.[citation needed]

In addition, gestalt theory can be used to explain the illusory contours in the Kanizsa's triangle. A floating white triangle, which does not exist, is seen. The brain has a need to see familiar simple objects and has a tendency to create a "whole" image from individual elements.[21] Gestalt means "form" or "shape" in German. However, another explanation of the Kanizsa's triangle is based in evolutionary psychology and the fact that in order to survive it was important to see form and edges. The use of perceptual organization to create meaning out of stimuli is the principle behind other well-known illusions including impossible objects. The brain makes sense of shapes and symbols putting them together like a jigsaw puzzle, formulating that which is not there to that which is believable.[citation needed]

The gestalt principles of perception govern the way different objects are grouped. Good form is where the perceptual system tries to fill in the blanks in order to see simple objects rather than complex objects. Continuity is where the perceptual system tries to disambiguate which segments fit together into continuous lines. Proximity is where objects that are close together are associated. Similarity is where objects that are similar are seen as associated. Some of these elements have been successfully incorporated into quantitative models involving optimal estimation or Bayesian inference.[22][23]

The double-anchoring theory, a popular but recent theory of lightness illusions, states that any region belongs to one or more frameworks, created by gestalt grouping principles, and within each frame is independently anchored to both the highest luminance and the surround luminance. A spot's lightness is determined by the average of the values computed in each framework.[24]

Monocular depth and motion perception

[edit]

Illusions can be based on an individual's ability to see in three dimensions even though the image hitting the retina is only two dimensional. The Ponzo illusion is an example of an illusion which uses monocular cues of depth perception to fool the eye. But even with two-dimensional images, the brain exaggerates vertical distances when compared with horizontal distances, as in the vertical–horizontal illusion where the two lines are exactly the same length.

In the Ponzo illusion the converging parallel lines tell the brain that the image higher in the visual field is farther away, therefore, the brain perceives the image to be larger, although the two images hitting the retina are the same size. The optical illusion seen in a diorama/false perspective also exploits assumptions based on monocular cues of depth perception. The M.C. Escher painting Waterfall exploits rules of depth and proximity and our understanding of the physical world to create an illusion. Like depth perception, motion perception is responsible for a number of sensory illusions. Film animation is based on the illusion that the brain perceives a series of slightly varied images produced in rapid succession as a moving picture. Likewise, when we are moving, as we would be while riding in a vehicle, stable surrounding objects may appear to move. We may also perceive a large object, like an airplane, to move more slowly than smaller objects, like a car, although the larger object is actually moving faster. The phi phenomenon is yet another example of how the brain perceives motion, which is most often created by blinking lights in close succession.

The ambiguity of direction of motion due to lack of visual references for depth is shown in the spinning dancer illusion. The spinning dancer appears to be moving clockwise or counterclockwise depending on spontaneous activity in the brain where perception is subjective. Recent studies show on the fMRI that there are spontaneous fluctuations in cortical activity while watching this illusion, particularly the parietal lobe because it is involved in perceiving movement.[25]

Binocular illusions

[edit]Illusions in binocular vision refer to situations which are exclusive for binocular viewing.

Illusory disparities

[edit]Binocular depth information is abstracted from binocular disparities. In general this information is more trustworthy than monocular depth information.

Two identical objects behind each other have the same retinal images as two similar objects next to each other. At a small distance between A and B the brain chooses to see option C,D. This results in an illusion if the real objects are present at positions A,B and not at C,D (double-nail illusion).

This illusion illustrates binocular ghost images and has many Variants and conflicts with tactile, motor and monocular cues (multi-modal illusion).

Edge detection

[edit]

When a thin object like a razor blade is held in the midsagittal plane, then it is seen at a right angle to the viewing direction (Midsagittal-strip illusion).

This illusion suggests that the visual system detects the disparity of edges (rims) with equal contrast sign only.

Depth of surfaces

[edit]

When a black disc is present hovering in front of a white disc, then this can be perceived as it physically is, or as a truncated white cone. If a physical white cone with a black top is presented, then this can be perceived as it physically is, or as a black disc hovering above a white disc. In other words, the observer cannot distinguish between seeing a disc on a pin above a white background, and a white truncated cone with a black top-plane (Ambiguous 3D-surfaces).

This illusion suggests that the visual system detects the disparity (depth) of equal-sign edges and fills in the orientation of surfaces in between.

Delayed signals

[edit]

When viewing the swinging movement of the rain wiper of a car, and holding a grey filter or dark sunglass in front of one of the eyes, the pendulum appears to make an elliptical movement in depth. It even appears to move through the glass. (Pulfrich illusion).

This is suggests that the signals of the covered eye are processed with a delay.

Interaction with monocular depth cues

[edit]When stereoimages are swapped (pseudoscopy) binocular depth is inversed and conflicts with monocular depth cues. Perceived depth appears to correspond with the inversed disparity, but the apparent size of objects looks different. Nearby objects appear bigger and far objects appear smaller than normal.

Color and brightness constancies

[edit]

Perceptual constancies are sources of illusions. Color constancy and brightness constancy are responsible for the fact that a familiar object will appear the same color regardless of the amount of light or color of light reflecting from it. An illusion of color difference or luminosity difference can be created when the luminosity or color of the area surrounding an unfamiliar object is changed. The luminosity of the object will appear brighter against a black field (that reflects less light) than against a white field, even though the object itself did not change in luminosity. Similarly, the eye will compensate for color contrast depending on the color cast of the surrounding area.

In addition to the gestalt principles of perception, water-color illusions contribute to the formation of optical illusions. Water-color illusions consist of object-hole effects and coloration. Object-hole effects occur when boundaries are prominent where there is a figure and background with a hole that is 3D volumetric in appearance. Coloration consists of an assimilation of color radiating from a thin-colored edge lining a darker chromatic contour. The water-color illusion describes how the human mind perceives the wholeness of an object such as top-down processing. Thus, contextual factors play into perceiving the brightness of an object.[26]

Object

[edit]

Just as it perceives color and brightness constancies, the brain has the ability to understand familiar objects as having a consistent shape or size. For example, a door is perceived as a rectangle regardless of how the image may change on the retina as the door is opened and closed. Unfamiliar objects, however, do not always follow the rules of shape constancy and may change when the perspective is changed. The Shepard tables illusion[27] is an example of an illusion based on distortions in shape constancy.

Future perception

[edit]Researcher Mark Changizi of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in New York has a more imaginative take on optical illusions, saying that they are due to a neural lag which most humans experience while awake. When light hits the retina, about one-tenth of a second goes by before the brain translates the signal into a visual perception of the world. Scientists have known of the lag, yet they have debated how humans compensate, with some proposing that our motor system somehow modifies our movements to offset the delay.[28]

Changizi asserts that the human visual system has evolved to compensate for neural delays by generating images of what will occur one-tenth of a second into the future. This foresight enables humans to react to events in the present, enabling humans to perform reflexive acts like catching a fly ball and to maneuver smoothly through a crowd.[29] In an interview with ABC Changizi said, "Illusions occur when our brains attempt to perceive the future, and those perceptions don't match reality."[30] For example, an illusion called the Hering illusion looks like bicycle spokes around a central point, with vertical lines on either side of this central, so-called vanishing point.[31] The illusion tricks us into thinking we are looking at a perspective picture, and thus according to Changizi, switches on our future-seeing abilities. Since we are not actually moving and the figure is static, we misperceive the straight lines as curved ones. Changizi said:

Evolution has seen to it that geometric drawings like this elicit in us premonitions of the near future. The converging lines toward a vanishing point (the spokes) are cues that trick our brains into thinking we are moving forward—as we would in the real world, where the door frame (a pair of vertical lines) seems to bow out as we move through it—and we try to perceive what that world will look like in the next instant.[29]

Pathological visual illusions (distortions)

[edit]A pathological visual illusion is a distortion of a real external stimulus[32] and is often diffuse and persistent. Pathological visual illusions usually occur throughout the visual field, suggesting global excitability or sensitivity alterations.[33] Alternatively visual hallucination is the perception of an external visual stimulus where none exists.[32] Visual hallucinations are often from focal dysfunction and are usually transient.

Types of visual illusions include oscillopsia, halos around objects, illusory palinopsia (visual trailing, light streaking, prolonged indistinct afterimages), akinetopsia, visual snow, micropsia, macropsia, teleopsia, pelopsia, metamorphopsia, dyschromatopsia, intense glare, blue field entoptic phenomenon, and purkinje trees.

These symptoms may indicate an underlying disease state and necessitate seeing a medical practitioner. Etiologies associated with pathological visual illusions include multiple types of ocular disease, migraines, hallucinogen persisting perception disorder, head trauma, and prescription drugs. If a medical work-up does not reveal a cause of the pathological visual illusions, the idiopathic visual disturbances could be analogous to the altered excitability state seen in visual aura with no migraine headache. If the visual illusions are diffuse and persistent, they often affect the patient's quality of life. These symptoms are often refractory to treatment and may be caused by any of the aforementioned etiologies, but are often idiopathic. There is no standard treatment for these visual disturbances.

Connections to psychological disorders

[edit]The rubber hand illusion (RHI)

[edit]

The rubber hand illusion (RHI), a multi-sensory illusion involving both visual perception and touch, has been used to study how phantom limb syndrome affects amputees over time.[5] Amputees with the syndrome actually responded to RHI more strongly than controls, an effect that was often consistent for both the sides of the intact and the amputated arm.[5] However, in some studies, amputees actually had stronger responses to RHI on their intact arm, and more recent amputees responded to the illusion better than amputees who had been missing an arm for years or more.[5] Researchers believe this is a sign that the body schema, or an individual's sense of their own body and its parts, progressively adapts to the post-amputation state.[5] Essentially, the amputees were learning to no longer respond to sensations near what had once been their arm.[5] As a result, many have suggested the use of RHI as a tool for monitoring an amputee's progress in reducing their phantom limb sensations and adjusting to the new state of their body.[5]

Other research used RHI in the rehabilitation of amputees with prosthetic limbs.[34] After prolonged exposure to RHI, the amputees gradually stopped feeling a dissociation between the prosthetic (which resembled the rubber hand) and the rest of their body.[34] This was thought to be because they adjusted to responding to and moving a limb that did not feel as connected to the rest of their body or senses.[34]

RHI may also be used to diagnose certain disorders related to impaired proprioception or impaired sense of touch in non-amputees.[34]

Illusions and schizophrenia

[edit]

Schizophrenia, a mental disorder often marked by hallucinations, also decreases a person's ability to perceive high-order optical illusions.[6] This is because schizophrenia impairs one's capacity to perform top-down processing and a higher-level integration of visual information beyond the primary visual cortex, V1.[6] Understanding how this specifically occurs in the brain may help in understanding how visual distortions, beyond imaginary hallucinations, affect schizophrenic patients.[6] Additionally, evaluating the differences between how schizophrenic patients and unaffected individuals see illusions may enable researchers to better identify where specific illusions are processed in the visual streams.[6]

One study on schizophrenic patients found that they were extremely unlikely to be fooled by a three dimensional optical illusion, the hollow face illusion, unlike non-affected volunteers.[35] Based on fMRI data, researchers concluded that this resulted from a disconnection between their systems for bottom-up processing of visual cues and top-down interpretations of those cues in the parietal cortex.[35] In another study on the motion-induced blindness (MIB) illusion (pictured right), schizophrenic patients continued to perceive stationary visual targets even when observing distracting motion stimuli, unlike non schizophrenic controls, who experienced motion induced blindness.[36] The schizophrenic test subjects demonstrated impaired cognitive organization, meaning they were less able to coordinate their processing of motion cues and stationary image cues.[36]

In art

[edit]Artists who have worked with optical illusions include M. C. Escher,[37] Bridget Riley, Salvador Dalí, Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Patrick Bokanowski, Marcel Duchamp, Jasper Johns, Oscar Reutersvärd, Victor Vasarely and Charles Allan Gilbert. Contemporary artists who have experimented with illusions include Jonty Hurwitz, Sandro del Prete, Octavio Ocampo, Dick Termes, Shigeo Fukuda, Patrick Hughes, István Orosz, Rob Gonsalves, Gianni A. Sarcone, Ben Heine and Akiyoshi Kitaoka. Optical illusion is also used in film by the technique of forced perspective.

Op art is a style of art that uses optical illusions to create an impression of movement, or hidden images and patterns. Trompe-l'œil uses realistic imagery to create the optical illusion that depicted objects exist in three dimensions.

Tourists attractions employing large-scale illusory art allowing visitors to photograph themselves in fantastic scenes have opened in several Asian countries, such as the Trickeye Museum and Hong Kong 3D Museum.[38][39]

Cognitive processes hypothesis

[edit]The hypothesis claims that visual illusions occur because the neural circuitry in our visual system evolves, by neural learning, to a system that makes very efficient interpretations of usual 3D scenes based in the emergence of simplified models in our brain that speed up the interpretation process but give rise to optical illusions in unusual situations. In this sense, the cognitive processes hypothesis can be considered a framework for an understanding of optical illusions as the signature of the empirical statistical way vision has evolved to solve the inverse problem.[40]

Research indicates that 3D vision capabilities emerge and are learned jointly with the planning of movements.[41] That is, as depth cues are better perceived, individuals can develop more efficient patterns of movement and interaction within the 3D environment around them.[41] After a long process of learning, an internal representation of the world emerges that is well-adjusted to the perceived data coming from closer objects. The representation of distant objects near the horizon is less "adequate".[further explanation needed] In fact, it is not only the Moon that seems larger when we perceive it near the horizon. In a photo of a distant scene, all distant objects are perceived as smaller than when we observe them directly using our vision.

Gallery

[edit]-

Motion aftereffect: this video produces a distortion illusion when the viewer looks away after watching it.

-

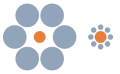

Ebbinghaus illusion: the orange circle on the left appears smaller than that on the right, but they are in fact the same size.

-

Café wall illusion: the parallel horizontal lines in this image appear sloped.

-

Checker version: the diagonal checker squares at the larger grid points make the grid appear distorted.

-

Checker version with horizontal and vertical central symmetry

-

Lilac chaser: if the viewer focuses on the black cross in the center, the location of the disappearing dot appears green.

-

Motion illusion: contrasting colors create the illusion of motion.

-

Watercolor illusion: this shape's yellow and blue border create the illusion of the object being pale yellow rather than white[42]

-

Phenakistoscope which is spun displaying the illusion of motion of a man bowing and a woman curtsying to each other in a circle at the outer edge of the disc, 1833

-

A hybrid image constructed from low-frequency components of a photograph of Marilyn Monroe (left inset) and high-frequency components of a photograph of Albert Einstein (right inset). The Einstein image is clearer in the full image.

-

An ancient Roman geometric mosaic. The cubic texture induces a Necker-cube-like optical illusion.

-

A set of colorful spinning disks that create illusion. The disks appear to move backwards and forwards in different regions.

-

Pinna-Brelstaff illusion: the two circles seem to move when the viewer's head is moving forwards and backwards while looking at the black dot.[47]

-

The Spinning Dancer appears to move both clockwise and counter-clockwise.

-

Forced perspective: the man is made to appear to be supporting the Leaning Tower of Pisa in the background.

-

Scintillating grid illusion: Dark dots seem to appear and disappear rapidly at random intersections, hence the label "scintillating".

-

Building rooms where the furniture is attached to the ceiling makes it appear the two men are upside down.

-

Illusion on the floor of the Florence Cathedral

-

In 3D: the two pins A and B appear at positions C en D ( Double-nail illusion)

-

In 3D: plane CD is seen, AB is not. (Midsagittal-strip illusion).

-

In 3D: cone or disc (Ambiguous 3D- surfaces).

See also

[edit]![]() Media related to Optical illusion at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Optical illusion at Wikimedia Commons

- Auditory illusion

- Barberpole illusion (Barber's pole)

- Camouflage

- Chronostasis (stopped-clock illusion)

- Closed-eye hallucination/visualization

- Contour rivalry

- Ebbinghaus illusion

- Emmert's law

- Flashed face distortion effect

- Fraser spiral illusion

- Gravity hill

- Human reactions to infrasound

- Hidden faces

- Infinity edge pool

- Kinetic depth effect

- List of optical illusions

- Mirage

- Motion silencing illusion

- Multistable perception

- Rabbit–duck illusion

- The dress

- Troxler's fading

- Visual space

- Watercolour illusion

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Gregory, Richard (1991). "Putting illusions in their place". Perception. 20 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1068/p200001. PMID 1945728. S2CID 5521054.

- ^ In the scientific literature the term "visual illusion" is preferred because the older term gives rise to the assumption that the optics of the eye were the general cause for illusions (which is only the case for so-called physical illusions). "Optical" in the term derives from the Greek optein = "seeing", so the term refers to an "illusion of seeing", not to optics as a branch of modern physics. A regular scientific source for illusions are the journals Perception and i-Perception

- ^ Bach, Michael; Poloschek, C. M. (2006). "Optical Illusions" (PDF). Adv. Clin. Neurosci. Rehabil. 6 (2): 20–21. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 20, 2021. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gregory, Richard L. (1997). "Visual illusions classified" (PDF). Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 1 (5): 190–194. doi:10.1016/s1364-6613(97)01060-7. PMID 21223901. S2CID 42228451.

- ^ a b c d e f g DeCastro, Thiago Gomes; Gomes, William Barbosa (2017-05-25). "Rubber Hand Illusion: Evidence for a multisensory integration of proprioception". Avances en Psicología Latinoamericana. 35 (2): 219. doi:10.12804/revistas.urosario.edu.co/apl/a.3430. ISSN 2145-4515.

- ^ a b c d e King, Daniel J.; Hodgekins, Joanne; Chouinard, Philippe A.; Chouinard, Virginie-Anne; Sperandio, Irene (2017-06-01). "A review of abnormalities in the perception of visual illusions in schizophrenia". Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 24 (3): 734–751. doi:10.3758/s13423-016-1168-5. ISSN 1531-5320.

- ^ Goldstein, E. Bruce (2002). Sensation and Perception. Pacific Grove, CA: Wadsworth. ISBN 0-534-53964-5., Chpt. 7

- ^ Wade, Nicholas J. (1998). A natural history of vision. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- ^ "After Images". worqx.com. Archived from the original on April 22, 2015.

- ^ Pinel, J. (2005) Biopsychology (6th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. ISBN 0-205-42651-4

- ^ Lingelbach B, Block B, Hatzky B, Reisinger E (1985). "The Hermann grid illusion -- retinal or cortical?". Perception. 14 (1): A7.

- ^ Geier J, Bernáth L (2004). "Stopping the Hermann grid illusion by simple sine distortion". Perception. Malden Ma: Blackwell. pp. 33–53. ISBN 978-0631224211.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ Schiller, Peter H.; Carvey, Christina E. (2005). "The Hermann grid illusion revisited". Perception. 34 (11): 1375–1397. doi:10.1068/p5447. PMID 16355743. S2CID 15740144. Archived from the original on December 12, 2011. Retrieved October 3, 2011.

- ^ Geier J, Bernáth L, Hudák M, Séra L (2008). "Straightness as the main factor of the Hermann grid illusion". Perception. 37 (5): 651–665. doi:10.1068/p5622. PMID 18605141. S2CID 21028439.

- ^ Bach, Michael (2008). "Die Hermann-Gitter-Täuschung: Lehrbucherklärung widerlegt (The Hermann grid illusion: the classic textbook interpretation is obsolete)". Ophthalmologe. 106 (10): 913–917. doi:10.1007/s00347-008-1845-5. PMID 18830602. S2CID 1573891.

- ^ Howe, Catherine Q.; Yang, Zhiyong; Purves, Dale (2005). "The Poggendorff illusion explained by natural scene geometry". PNAS. 102 (21): 7707–7712. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.7707H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0502893102. PMC 1093311. PMID 15888555.

- ^ David Eagleman (April 2012). Incogito: The Secret Lives of the Brain. Vintage Books. pp. 33–. ISBN 978-0-307-38992-3. Archived from the original on October 12, 2013. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- ^ Gili Malinsky (July 22, 2019). "An optical illusion that seems to be both a circle and a square is baffling the internet — here's how it works". Insider.

- ^ Petry, Susan; Meyer, Glenn E. (December 6, 2012). The Perception of Illusory Contours. Springer; 1987th edition. p. 696. ISBN 9781461247609.

- ^ Gregory, R. L. (1972). "Cognitive Contours". Nature. 238 (5358): 51–52. Bibcode:1972Natur.238...51G. doi:10.1038/238051a0. PMID 12635278. S2CID 4285883. Retrieved September 4, 2021.

- ^ a b Myers, D. (2003). Psychology in Modules, (7th ed.) New York: Worth. ISBN 0-7167-5850-4

- ^ Yoon Mo Jung and Jackie (Jianhong) Shen (2008), J. Visual Comm. Image Representation, 19(1):42–55, First-order modeling and stability analysis of illusory contours.

- ^ Yoon Mo Jung and Jackie (Jianhong) Shen (2014), arXiv:1406.1265, Illusory shapes via phase transition Archived 2017-11-24 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Bressan, P (2006). "The Place of White in a World of Grays: A Double-Anchoring Theory of Lightness Perception". Psychological Review. 113 (3): 526–553. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.113.3.526. hdl:11577/1560501. PMID 16802880.

- ^ Bernal, B., Guillen, M., & Marquez, J. (2014). The spinning dancer illusion and spontaneous brain fluctuations: An fMRI study. Neurocase (Psychology Press), 20(6), 627-639.

- ^ Tanca, M.; Grossberg, S.; Pinna, B. (2010). "Probing Perceptual Antinomies with the Watercolor Illusion and Explaining How the Brain Resolves Them" (PDF). Seeing & Perceiving. 23 (4): 295–333. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.174.7709. doi:10.1163/187847510x532685. PMID 21466146. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2017.

- ^ Bach, Michael (January 4, 2010) [16 August 2004]. "Shepard's "Turning the Tables"". michaelbach.de. Michael Bach. Archived from the original on December 27, 2009. Retrieved January 27, 2010.

- ^ Bryner, Jeanna. "Scientist: Humans Can See Into Future". Fox News. Archived from the original on September 16, 2016. Retrieved July 13, 2018.

- ^ a b "Key to All-Optical Illusions Discovered" Archived 2008-09-05 at the Wayback Machine, Jeanna Bryner, Senior Writer, LiveScience.com 6/2/08. His research on this topic is detailed in the May/June 2008 issue of the journal Cognitive Science.

- ^ NIERENBERG, CARI (February 7, 2008). "Optical Illusions: When Your Brain Can't Believe Your Eyes". ABC News. Retrieved July 13, 2018.

- ^ Barile, Margherita. "Hering Illusion". mathworld. Wolfram. Retrieved July 13, 2018.

- ^ a b Pelak, Victoria. "Approach to the patient with visual hallucinations". www.uptodate.com. Archived from the original on August 26, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ^ Gersztenkorn, D; Lee, AG (July 2, 2014). "Palinopsia revamped: A systematic review of the literature". Survey of Ophthalmology. 60 (1): 1–35. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2014.06.003. PMID 25113609.

- ^ a b c d Christ, Oliver; Reiner, Miriam (2014-07-01). "Perspectives and possible applications of the rubber hand and virtual hand illusion in non-invasive rehabilitation: Technological improvements and their consequences". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. Applied Neuroscience: Models, methods, theories, reviews. A Society of Applied Neuroscience (SAN) special issue. 44: 33–44. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.02.013. ISSN 0149-7634

- ^ a b Dima, Danai; Roiser, Jonathan P.; Dietrich, Detlef E.; Bonnemann, Catharina; Lanfermann, Heinrich; Emrich, Hinderk M.; Dillo, Wolfgang (July 15, 2009). "Understanding why patients with schizophrenia do not perceive the hollow-mask illusion using dynamic causal modelling". NeuroImage. 46 (4): 1180–1186. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.03.033. ISSN 1053-8119. PMID 19327402. S2CID 10008080.

- ^ a b Tschacher, Wolfgang; Schuler, Daniela; Junghan, Ulrich (January 31, 2006). "Reduced perception of the motion-induced blindness illusion in schizophrenia". Schizophrenia Research. 81 (2): 261–267. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2005.08.012. ISSN 0920-9964. PMID 16243490. S2CID 10752733.

- ^ Seckel, Al (2017). Masters of Deception: Escher, Dalí & the Artists of Optical Illusion. Sterling. p. 320. ISBN 9781402705779.

- ^ "3-D museums: Next big thing for Asia tourism?". CNBC. August 28, 2014.

- ^ Seow, Bei Yi (June 13, 2014). "3-D art wows visitors | the Straits Times". The Straits Times.

- ^ Gregory, Richard L. (1997). "Knowledge in perception and illusion" (PDF). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 352 (1358): 1121–7. Bibcode:1997RSPTB.352.1121G. doi:10.1098/rstb.1997.0095. PMC 1692018. PMID 9304679. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 4, 2005.

- ^ a b Sweet, Barbara; Kaiser, Mary (August 2011). "Depth Perception, Cueing, and Control" (PDF). AIAA Modeling and Simulation Technologies Conference. NASA Ames Research Center. doi:10.2514/6.2011-6424. hdl:2060/20180007277. ISBN 978-1-62410-154-0. S2CID 16425060 – via American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics.

- ^ Bangio Pinna; Gavin Brelstaff; Lothar Spillman (2001). "Surface color from boundaries: a new watercolor illusion". Vision Research. 41 (20): 2669–2676. doi:10.1016/s0042-6989(01)00105-5. PMID 11520512. S2CID 16534759.

- ^ Hoffmann, Donald D. (1998). Visual Intelligence. How we create what we see. Norton., p.174

- ^ Stephen Grossberg; Baingio Pinna (2012). "Neural Dynamics of Gestalt Principles of Perceptual Organization: From Grouping to Shape and Meaning" (PDF). Gestalt Theory. 34 (3+4): 399–482. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 4, 2013. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- ^ Pinna, B.; Gregory, R.L.; Spillmann, L. (2002). "Shifts of Edges and Deformations of Patterns". Perception. 31 (12): 1503–1508. doi:10.1068/p3112pp. PMID 12916675. S2CID 220053062.

- ^ Pinna, Baingio (2009). "Pinna illusion". Scholarpedia. 4 (2): 6656. Bibcode:2009SchpJ...4.6656P. doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.6656.

- ^ Baingio Pinna; Gavin J. Brelstaff (2000). "A new visual illusion of relative motion" (PDF). Vision Research. 40 (16): 2091–2096. doi:10.1016/S0042-6989(00)00072-9. PMID 10878270. S2CID 11034983. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 5, 2013.

References

[edit]- Bach, Michael; Poloschek, C. M. (2006). "Optical Illusions" (PDF). Adv. Clin. Neurosci. Rehabil. 6 (2): 20–21. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 20, 2021. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- Changizi, Mark A.; Hsieh, Andrew; Nijhawan, Romi; Kanai, Ryota; Shimojo, Shinsuke (2008). "Perceiving the Present and a Systematization of Illusions" (PDF). Cognitive Science. 32 (3): 459–503. doi:10.1080/03640210802035191. PMID 21635343.

- Eagleman, D. M. (2001). "Visual Illusions and Neurobiology" (PDF). Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2 (12): 920–6. doi:10.1038/35104092. PMID 11733799. S2CID 205023280.

- Gregory, Richard (1991). "Putting illusions in their place". Perception. 20 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1068/p200001. PMID 1945728. S2CID 5521054.

- Gregory, Richard (1997). "Knowledge in perception and illusion" (PDF). Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. 352 (1358): 1121–1128. Bibcode:1997RSPTB.352.1121G. doi:10.1098/rstb.1997.0095. PMC 1692018. PMID 9304679.

- Purves, D.; Lotto, R.B.; Nundy, S. (2002). "Why We See What We Do". American Scientist. 90 (3): 236–242. doi:10.1511/2002.9.784.

- Purves, D.; Williams, M. S.; Nundy, S.; Lotto, R. B. (2004). "Perceiving the intensity of light". Psychological Review. 111 (1): 142–158. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1008.6441. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.111.1.142. PMID 14756591.

- Renier, L.; Laloyaux, C.; Collignon, O.; Tranduy, D.; Vanlierde, A.; Bruyer, R.; De Volder, A. G. (2005). "The Ponzo illusion using auditory substitution of vision in sighted and early blind subjects". Perception. 34 (7): 857–867. doi:10.1068/p5219. PMID 16124271. S2CID 17265107.

- Renier, L.; Bruyer, R.; De Volder, A. G. (2006). "Vertical-horizontal illusion present for sighted but not early blind humans using auditory substitution of vision". Perception & Psychophysics. 68 (4): 535–542. doi:10.3758/bf03208756. PMID 16933419.

- Yang, Z.; Purves, D. (2003). "A statistical explanation of visual space". Nature Neuroscience. 6 (6): 632–640. doi:10.1038/nn1059. PMID 12754512. S2CID 610068.

- Dixon, E.; Shapiro, A.; Lu, Z. (2014). "Scale-Invariance in brightness illusions implicates object-level visual processing". Scientific Reports. 4: 3900. Bibcode:2014NatSR...4E3900D. doi:10.1038/srep03900. PMC 3905277. PMID 24473496.

Further reading

[edit]- Purves, Dale; et al. (2008). "Visual illusions:An Empirical Explanation". Scholarpedia. 3 (6): 3706. Bibcode:2008SchpJ...3.3706P. doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.3706.

- David Cycleback. 2018. Understanding Human Minds and Their Limits. Publisher Bookboon.com ISBN 978-87-403-2286-6

![Watercolor illusion: this shape's yellow and blue border create the illusion of the object being pale yellow rather than white[42]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/20/Subjectively_constructed_water-color.svg/120px-Subjectively_constructed_water-color.svg.png)

![Subjective cyan filter, left: subjectively constructed cyan square filter above blue circles, right: small cyan circles inhibit filter construction[43][44]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/ca/Optical_illusion_-_subjectively_constructed_cyan_sqare_filter_above_blue_cirles.gif/120px-Optical_illusion_-_subjectively_constructed_cyan_sqare_filter_above_blue_cirles.gif)

![Pinna's illusory intertwining effect[45] and Pinna illusion (scholarpedia).[46] The picture shows squares spiralling in, although they are arranged in concentric circles.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/45/Pinna%27s_illusory_intertwining_effect.gif/120px-Pinna%27s_illusory_intertwining_effect.gif)

![Pinna-Brelstaff illusion: the two circles seem to move when the viewer's head is moving forwards and backwards while looking at the black dot.[47]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b1/Revolving_circles.svg/120px-Revolving_circles.svg.png)