Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Baluster

View on Wikipedia

A baluster (/ˈbæləstər/ ⓘ) is an upright support, often a vertical moulded shaft, square, or lathe-turned form found in stairways, parapets, and other architectural features. In furniture construction it is known as a spindle. Common materials used in its construction are wood, stone, and less frequently metal and ceramic. A group of balusters supporting a guard railing, coping, or ornamental detail is known as a balustrade.[1][2]

The term baluster shaft is used to describe forms such as a candlestick, upright furniture support, and the stem of a brass chandelier.[citation needed]

The term banister (also bannister) refers to a baluster or to the system of balusters and handrail of a stairway.[3] It may be used to include its supporting structures, such as a supporting newel post.[4]

In the UK, there are different height requirements for domestic and commercial balustrades, as outlined in Approved Document K.[5]

Etymology

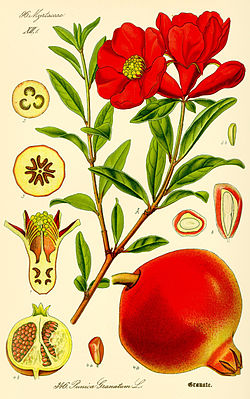

[edit]According to the Oxford English Dictionary, "baluster" is derived through the French: balustre, from Italian: balaustro, from balaustra, "pomegranate flower" [from a resemblance to the swelling form of the half-open flower (illustration, below right)],[6][7] from Latin balaustrium, from Greek βαλαύστριον (balaustrion).

History

[edit]The earliest examples of balusters are those shown in the bas-reliefs representing the Assyrian palaces, where they were employed as functional window balustrades and apparently had Ionic capitals.[1] As an architectural element alone the balustrade did not seem to have been known to either the Greeks or the Romans,[1][8] but baluster forms are familiar in the legs of chairs and tables represented in Roman bas-reliefs,[9] where the original legs or the models for cast bronze ones were shaped on the lathe, or in Antique marble candelabra, formed as a series of stacked bulbous and disc-shaped elements, both kinds of sources familiar to Quattrocento designers.

The application to architecture was a feature of the early Renaissance architecture: late fifteenth-century examples are found in the balconies of palaces at Venice and Verona. These quattrocento balustrades are likely to be following yet-unidentified Gothic precedents. They form balustrades of colonettes[10] as an alternative to miniature arcading.

Rudolf Wittkower withheld judgement as to the inventor of the baluster[11] and credited Giuliano da Sangallo with using it consistently as early as the balustrade on the terrace and stairs at the Medici villa at Poggio a Caiano (c 1480),[12] and used balustrades in his reconstructions of antique structures. Sangallo passed the motif to Bramante (his Tempietto, 1502) and Michelangelo, through whom balustrades gained wide currency in the 16th century.

Wittkower distinguished two types, one symmetrical in profile that inverted one bulbous vase-shape over another, separating them with a cushionlike torus or a concave ring, and the other a simple vase shape, whose employment by Michelangelo at the Campidoglio steps (c 1546), noted by Wittkower, was preceded by very early vasiform balusters in a balustrade round the drum of Santa Maria delle Grazie (c 1482), and railings in the cathedrals of Aquileia (c 1495) and Parma, in the cortile of San Damaso, Vatican, and Antonio da Sangallo's crowning balustrade on the Santa Casa at Loreto installed in 1535, and liberally in his model for the Basilica of Saint Peter.[13] Because of its low center of gravity, this "vase-baluster" may be given the modern term "dropped baluster".[14]

Materials used

[edit]

Balusters may be made of carved stone, cast stone, plaster, polymer, polyurethane/polystyrene, polyvinyl chloride (PVC), precast concrete, wood, or wrought iron. Cast-stone balusters were a development of the 18th century in Great Britain (see Coade stone), and cast iron balusters a development largely of the 1840s.[citation needed] As balusters and balustrades have evolved, they can now be made from various materials with a few popular choices being timber, glass and stainless steel.[citation needed]

Profiles and style changes

[edit]

The baluster, being a turned structure, tends to follow design precedents that were set in woodworking and ceramic practices, where the turner's lathe and the potter's wheel are ancient tools. The profile a baluster takes is often diagnostic of a particular style of architecture or furniture, and may offer a rough guide to date of a design, though not of a particular example.

Some complicated Mannerist baluster forms can be read as a vase set upon another vase. The high shoulders and bold, rhythmic shapes of the Baroque vase and baluster forms are distinctly different from the sober baluster forms of Neoclassicism, which look to other precedents, like Greek amphoras. The distinctive twist-turned designs of balusters in oak and walnut English and Dutch[16] seventeenth-century furniture, which took as their prototype the Solomonic column that was given prominence by Bernini, fell out of style after the 1710s.

Once it had been taken from the lathe, a turned wood baluster could be split and applied to an architectural surface, or to one in which architectonic themes were more freely treated, as on cabinets made in Italy, Spain and Northern Europe from the sixteenth through the seventeenth centuries.[17] Modern baluster design is also in use for example in designs influenced by the Arts and Crafts movement in a 1905 row of houses in Etchingham Park Road Finchley London England.

Outside Europe, the baluster column appeared as a new motif in Mughal architecture, introduced in Shah Jahan's interventions in two of the three great fortress-palaces, the Red Fort of Agra and Delhi,[18] in the early seventeenth century. Foliate baluster columns with naturalistic foliate capitals, unexampled in previous Indo-Islamic architecture according to Ebba Koch, rapidly became one of the most widely used forms of supporting shaft in Northern and Central India in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[19]

The modern term baluster shaft is applied to the shaft dividing a window in Saxon architecture. In the south transept of the Abbey in St Albans, England, are some of these shafts, supposed to have been taken from the old Saxon church. Norman bases and capitals have been added, together with plain cylindrical Norman shafts.[1]

Balusters are normally separated by at least the same measurement as the size of the square bottom section. Placing balusters too far apart diminishes their aesthetic appeal, and the structural integrity of the balustrade they form. Balustrades normally terminate in heavy newel posts, columns, and building walls for structural support.

Balusters may be formed in several ways. Wood and stone can be shaped on the lathe, wood can be cut from square or rectangular section boards, while concrete, plaster, iron, and plastics are usually formed by molding and casting. Turned patterns or old examples are used for the molds.

Gallery

[edit]-

Balusters influenced by the Arts and Crafts movement in a 1905 row of houses in Etchingham Park Road (Finchley, London)

-

Ornate upper bronze balustrade, lower vasiform stone balustrade, and bronze central rail supported by decorative bronze metalwork at Brown University's Orwig Music Library

-

Balustrade of turned wood balusters of Quema Ancestral House a typical bahay na bato

-

Stone balustrade at Schloss Veitshöchheim near Würzburg, Germany

-

Balustrade in the form of a serpent, Mueang Chiang Mai, Chiang Mai, Thailand

-

Bronze balustrade, formerly of Saint Servatius bridge of 1836, now in Maastricht, Netherlands

-

Simple balustrade of turned wood balusters of a style common in North America

-

Marble balustrade in San Gaetano, Brescia, Italy

-

Stairway Balustrade by Florence Truelson, 1937 (National Gallery of Art), USA

-

The balustrade of Cameron's Gallery at Tsarskoye Selo, Russia

See also

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Baluster". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 297.

- ^ "A row of balusters surmounted by a rail or coping" 1644. OED; "AskOxford". Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2007-06-26.

- ^ "AskOxford". Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2007-06-26.

- ^ "banister". Retrieved 28 April 2018 – via The Free Dictionary.

- ^ "Balustrade Regulations UK: Official Rules & Regs Explained". Universal Industrial Services. 9 September 2024. Retrieved 21 January 2025.

- ^ The early sixteenth-century theoretical writer Diego da Sangredo (Medidas del Romano, 1526) detected this derivation, N. Llewellyn noted, in "Two notes on Diego da Sangredo: 2. The baluster and the pomegranate flower", in Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 40 (1977:240-300); Paul Davies and David Hemsoll's detailed history, "Renaissance Balusters and the Antique", in Architectural History 26 (1983:1–23, 117–122) p.8 notes uses of the word in fifteenth-century documents and explores its connotations for sixteenth-century designers, pp 12ff.

- ^ "Balaústre: o que é, como usar, onde comprar? Veja + exemplos lindos!". Balaústres (in Brazilian Portuguese). 2021-08-03. Retrieved 2021-11-21.

- ^ Wittkower 1974

- ^ Davies and Hemsoll 1983:2.

- ^ A colonette is a miniature column, used decoratively.

- ^ H. Siebenhüner, in tracing the baluster's career, found its origin in the profile of the round base of Donatello's Judith and Holofernes, c 1460 (Siebenhüner, "Docke", in Reallexikon zur Deutsche Kunstgeschichte, vol. 4 (1988), pp. 102-107).

- ^ Davies and Hemsol 1983 note the earliest uses of both types of baluster in fictive classicising thrones and architecture in paintings. They instance an earlier use in real architecture on the main façade of the Palazzo Ducale, Urbino, where Luciano Laurana was employed (p. 6 and pl. 3j).

- ^ These earlier appearances were adduced by Davies and Hemsol 1983:7f.

- ^ Davies and Hemsol 1983:1.

- ^ Hong Kong Investor With Eye on the Past Acquires Landmark Bradbury Building, Los Angeles Times

- ^ Twist-turned legs on a backstool feature prominently in a conversation piece of a couple in an elaborately fashionable Dutch interior, painted by Eglon van der Neer (1678): illustration.

- ^ The architectural invention of the applied half-baluster, with a caveat concerning "the fallacy of first recorded appearances", by Filippino Lippi in the painted architecture all'antica of his St. Philip revealing the Demon in the Strozzi Chapel, Santa Maria Novella, Florence, and in Michelangelo's planned use in the Medici Chapel, is explored by Paul Joannides, "Michelangelo, Filippino Lippi and the Half-Baluster", The Burlington Magazine 123 No. 936 (March 1981:152–154).

- ^ "There are no free-standing baluster columns of Shah Jahan's reign in the Fort at Lahore", according to Ebba Koch ("The Baluster Column: A European Motif in Mughal Architecture and Its Meaning", Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 45 (1982:251–262) p. 252) but balustrades are a feature of all three.

- ^ Ebba Koch 1982:251–262.

General and cited references

[edit]- Wittkower, Rudolf (1974). "Chapter Three: The Renaissance Caluster and Palladio". Palladio and English Palladianism. Margot Wittkower (foreword). London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 9780500850015. OCLC 905449767. (Links are to the 1983 American edition.)