Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Beta oxidation

View on WikipediaIn biochemistry and metabolism, beta oxidation (also β-oxidation) is the catabolic process by which fatty acid molecules are broken down in the cytosol in prokaryotes and in the mitochondria in eukaryotes to generate acetyl-CoA. Acetyl-CoA enters the citric acid cycle, generating NADH and FADH2, which are electron carriers used in the electron transport chain. It is named as such because the beta carbon of the fatty acid chain undergoes oxidation and is converted to a carbonyl group to start the cycle all over again. Beta-oxidation is primarily facilitated by the mitochondrial trifunctional protein, an enzyme complex associated with the inner mitochondrial membrane, although very long chain fatty acids are oxidized in peroxisomes.

The overall reaction for one cycle of beta oxidation is:

- Cn-acyl-CoA + FAD + NAD+ + H2O + CoA → Cn-2-acyl-CoA + FADH2 + NADH + H+ + acetyl-CoA

Activation and membrane transport

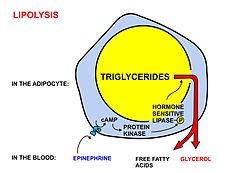

[edit]Free fatty acids cannot penetrate any biological membrane due to their negative charge. Free fatty acids must cross the cell membrane through specific transport proteins, such as the SLC27 family fatty acid transport protein.[1] Once in the cytosol, the following processes bring fatty acids into the mitochondrial matrix so that beta-oxidation can take place.

- Long-chain-fatty-acid—CoA ligase catalyzes the reaction between a fatty acid with ATP to give a fatty acyl adenylate, plus inorganic pyrophosphate, which then reacts with free coenzyme A to give a fatty acyl-CoA ester and AMP.

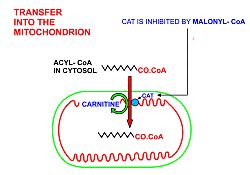

- If the fatty acyl-CoA has a long chain, then the carnitine shuttle must be utilized (shown in the table below):

- Acyl-CoA is transferred to the hydroxyl group of carnitine by carnitine palmitoyltransferase I, located on the cytosolic faces of the outer and inner mitochondrial membranes.

- Acyl-carnitine is shuttled inside by a carnitine-acylcarnitine translocase, as a carnitine is shuttled outside.

- Acyl-carnitine is converted back to acyl-CoA by carnitine palmitoyltransferase II, located on the interior face of the inner mitochondrial membrane. The liberated carnitine is shuttled back to the cytosol, as an acyl-carnitine is shuttled into the matrix.

- If the fatty acyl-CoA contains a short chain, these short-chain fatty acids can simply diffuse through the inner mitochondrial membrane.

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

General mechanism of beta oxidation

[edit]

Once the fatty acid is inside the mitochondrial matrix, beta-oxidation occurs by cleaving two carbons every cycle to form acetyl-CoA. The process consists of 4 steps.[2]

- A long-chain fatty acid is dehydrogenated to create a trans double bond between C2 and C3. This is catalyzed by acyl CoA dehydrogenase to produce trans-delta 2-enoyl CoA. It uses FAD as an electron acceptor and it is reduced to FADH2.

- Trans-delta 2-enoyl CoA is hydrated at the double bond to produce L-3-hydroxyacyl CoA by enoyl-CoA hydratase.

- L-3-hydroxyacyl CoA is dehydrogenated again to create 3-ketoacyl CoA by 3-hydroxyacyl CoA dehydrogenase. This enzyme uses NAD as an electron acceptor.

- Thiolysis occurs between C2 and C3 (alpha and beta carbons) of 3-ketoacyl CoA. Thiolase enzyme catalyzes the reaction when a new molecule of coenzyme A breaks the bond by nucleophilic attack on C3. This releases the first two carbon units, as acetyl CoA, and a fatty acyl CoA minus two carbons. The process continues until all of the carbons in the fatty acid are turned into acetyl CoA.

This acetyl-CoA then enters the mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA cycle). Both the fatty acid beta-oxidation and the TCA cycle produce NADH and FADH2, which are used by the electron transport chain to generate ATP.

Fatty acids are oxidized by most of the tissues in the body. However, some tissues such as the red blood cells of mammals (which do not contain mitochondria) and cells of the central nervous system do not use fatty acids for their energy requirements, but instead use carbohydrates (red blood cells and neurons) or ketone bodies (neurons only).

Because many fatty acids are not fully saturated or do not have an even number of carbons, several different mechanisms have evolved, described below.

Even-numbered saturated fatty acids

[edit]Once inside the mitochondria, each cycle of β-oxidation, liberating a two carbon unit (acetyl-CoA), occurs in a sequence of four reactions:[3]

| Description | Diagram | Enzyme | End product |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dehydrogenation by FAD: The first step is the oxidation of the fatty acid by Acyl-CoA-Dehydrogenase. The enzyme catalyzes the formation of a trans-double bond between the C-2 and C-3 by selectively remove hydrogen atoms from the β-carbon. The regioselectivity of this step is essential for the subsequent hydration and oxidation reactions. |  |

acyl CoA dehydrogenase | trans-Δ2-enoyl-CoA |

| Hydration: The next step is the hydration of the bond between C-2 and C-3. The reaction is stereospecific, forming only the L isomer. Hydroxyl group is positioned suitable for the subsequent oxidation reaction by 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase to create a β-keto group. |  |

enoyl CoA hydratase | L-β-hydroxyacyl CoA |

| Oxidation by NAD+: The third step is the oxidation of L-β-hydroxyacyl CoA by NAD+. This converts the hydroxyl group into a keto group. |  |

3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase | β-ketoacyl CoA |

| Thiolysis: The final step is the cleavage of β-ketoacyl CoA by the thiol group of another molecule of Coenzyme A. The thiol is inserted between C-2 and C-3. |  |

β-ketothiolase | An acetyl-CoA molecule, and an acyl-CoA molecule that is two carbons shorter |

This process continues until the entire chain is cleaved into acetyl CoA units. The final cycle produces two separate acetyl CoAs, instead of one acyl CoA and one acetyl CoA. For every cycle, the Acyl CoA unit is shortened by two carbon atoms. Concomitantly, one molecule of FADH2, NADH and acetyl CoA are formed.

Odd-numbered saturated fatty acids

[edit]

Fatty acids with an odd number of carbons are found in the lipids of plants and some marine organisms. Many ruminant animals form a large amount of 3-carbon propionate during the fermentation of carbohydrates in the rumen.[4] Long-chain fatty acids with an odd number of carbon atoms are found particularly in ruminant fat and milk.[5]

Chains with an odd-number of carbons are oxidized in the same manner as even-numbered chains, but the final products are propionyl-CoA and acetyl-CoA.

Propionyl-CoA is first carboxylated using a bicarbonate ion into a D-stereoisomer of methylmalonyl-CoA. This reaction involves a biotin co-factor, ATP and the enzyme propionyl-CoA carboxylase.[6] The bicarbonate ion's carbon is added to the middle carbon of propionyl-CoA, forming a D-methylmalonyl-CoA. However, the D-conformation is enzymatically converted into the L-conformation by methylmalonyl-CoA epimerase. It then undergoes intramolecular rearrangement, which is catalyzed by methylmalonyl-CoA mutase (requiring B12 as a coenzyme) to form succinyl-CoA. The succinyl-CoA formed then enters the citric acid cycle.

However, whereas acetyl-CoA enters the citric acid cycle by condensing with an existing molecule of oxaloacetate, succinyl-CoA enters the cycle as a principal in its own right. Thus, the succinate just adds to the population of circulating molecules in the cycle and undergoes no net metabolization while in it. When this infusion of citric acid cycle intermediates exceeds cataplerotic demand (such as for aspartate or glutamate synthesis), some of them can be extracted to the gluconeogenesis pathway, in the liver and kidneys, through phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase, and converted to free glucose.[7]

Unsaturated fatty acids

[edit]β-Oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids poses a problem since the location of a cis-bond can prevent the formation of a trans-Δ2 bond which is essential for continuation of β-Oxidation as this conformation is ideal for enzyme catalysis. This is handled by additional two enzymes, Enoyl CoA isomerase and 2,4 Dienoyl CoA reductase.[8]

β-oxidation occurs normally until the acyl CoA (because of the presence of a double bond) is not an appropriate substrate for acyl CoA dehydrogenase, or enoyl CoA hydratase:

- If the acyl CoA contains a cis-Δ3 bond, then cis-Δ3-Enoyl CoA isomerase will convert the bond to a trans-Δ2 bond, which is a regular substrate.

- If the acyl CoA contains a cis-Δ4 double bond, then its dehydrogenation yields a 2,4-dienoyl intermediate, which is not a substrate for enoyl CoA hydratase. However, the enzyme 2,4 Dienoyl CoA reductase reduces the intermediate, using NADPH, into trans-Δ3-enoyl CoA. This compound is converted into a suitable intermediate by 3,2-Enoyl CoA isomerase and β-Oxidation continues.

Peroxisomal beta-oxidation

[edit]Fatty acid oxidation also occurs in peroxisomes when the fatty acid chains are too long to be processed by the mitochondria. The same enzymes are used in peroxisomes as in the mitochondrial matrix and acetyl-CoA is generated. Very long chain (greater than C-22) fatty acids, branched fatty acids,[9] some prostaglandins and leukotrienes[10] undergo initial oxidation in peroxisomes until octanoyl-CoA is formed, at which point it undergoes mitochondrial oxidation.[11]

One significant difference is that oxidation in peroxisomes is not coupled to ATP synthesis. Instead, the high-potential electrons are transferred to O2, which yields hydrogen peroxide. The enzyme catalase, found primarily in peroxisomes and the cytosol of erythrocytes (and sometimes in mitochondria[12]), converts the hydrogen peroxide into water and oxygen.

Peroxisomal β-oxidation also requires enzymes specific to the peroxisome and to very long fatty acids. There are four key differences between the enzymes used for mitochondrial and peroxisomal β-oxidation:

- The NADH formed in the third oxidative step cannot be reoxidized in the peroxisome, so reducing equivalents are exported to the cytosol.

- β-oxidation in the peroxisome requires the use of a peroxisomal carnitine acyltransferase (instead of carnitine acyltransferase I and II used by the mitochondria) for transport of the activated acyl group into the mitochondria for further breakdown.

- The first oxidation step in the peroxisome is catalyzed by the enzyme acyl-CoA oxidase.

- The β-ketothiolase used in peroxisomal β-oxidation has an altered substrate specificity, different from the mitochondrial β-ketothiolase.

Peroxisomal oxidation is induced by a high-fat diet and administration of hypolipidemic drugs like clofibrate.

Energy yield

[edit]Even-numbered saturated fatty acids

[edit]Theoretically, the ATP yield for each oxidation cycle where two carbons are broken down at a time is 17, as each NADH produces 3 ATP, FADH2 produces 2 ATP and a full rotation of Acetyl-CoA in citric acid cycle produces 12 ATP.[13] In practice, it is closer to 14 ATP for a full oxidation cycle as 2.5 ATP per NADH molecule is produced, 1.5 ATP per each FADH2 molecule is produced and Acetyl-CoA produces 10 ATP per rotation of the citric acid cycle[13](according to the P/O ratio). This breakdown is as follows:

| Source | ATP | Total |

|---|---|---|

| 1 FADH2 | x 1.5 ATP | = 1.5 ATP (Theoretically 2 ATP)[13] |

| 1 NADH | x 2.5 ATP | = 2.5 ATP (Theoretically 3 ATP)[13] |

| 1 Acetyl CoA | x 10 ATP | = 10 ATP (Theoretically 12 ATP) |

| 1 Succinyl CoA | x 4 ATP | = 4 ATP |

| Total | = 14 ATP |

For an even-numbered saturated fat (Cn), 0.5 * n - 1 oxidations are necessary, and the final process yields an additional acetyl CoA. In addition, two equivalents of ATP are lost during the activation of the fatty acid. Therefore, the total ATP yield can be stated as:

or

For instance, the ATP yield of palmitate (C16, n = 16) is:

Represented in table form:

| Source | ATP | Total |

|---|---|---|

| 7 FADH2 | x 1.5 ATP | = 10.5 ATP |

| 7 NADH | x 2.5 ATP | = 17.5 ATP |

| 8 Acetyl CoA | x 10 ATP | = 80 ATP |

| Activation | = -2 ATP | |

| Total | = 106 ATP |

Odd-numbered saturated fatty acid

[edit]

For an odd-numbered saturated fat (Cn), 0.5 * n - 1.5 oxidations are necessary, and the final process yields 8 acetyl CoA and 1 propionyl CoA. It is then converted to a succinyl CoA by a carboxylation reaction and generates additional 5 ATP (1 ATP is consumed in carboxylation process generating a net of 4 ATP). In addition, two equivalents of ATP are lost during the activation of the fatty acid. Therefore, the total ATP yield can be stated as:

or

For instance, the ATP yield of Nonadecylic acid (C19, n = 19) is:

Represented in table form:

| Source | ATP | Total |

|---|---|---|

| 8 FADH2 | x 1.5 ATP | = 12 ATP |

| 8 NADH | x 2.5 ATP | = 20 ATP |

| 8 Acetyl CoA | x 10 ATP | = 80 ATP |

| 1 Succinyl CoA | x 4 ATP | = 4 ATP |

| Activation | = -2 ATP | |

| Total | = 114 ATP |

Clinical significance

[edit]There are at least 25 enzymes and specific transport proteins in the β-oxidation pathway.[16] Of these, 18 have been associated with human disease as inborn errors of metabolism.

Furthermore, studies indicate that lipid disorders are involved in diverse aspects of tumorigenesis, and fatty acid metabolism makes malignant cells more resistant to a hypoxic environment. Accordingly, cancer cells can display irregular lipid metabolism with regard to both fatty acid synthesis and mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation (FAO) that are involved in diverse aspects of tumorigenesis and cell growth.[17] Several specific β-oxidation disorders have been identified.

Medium-chain acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase (MCAD) deficiency

[edit]Medium-chain acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase (MCAD) deficiency[18] is the most common fatty acid β-oxidation disorder and a prevalent metabolic congenital error It is often identified through newborn screening. Although children are normal at birth, symptoms usually emerge between three months and two years of age, with some cases appearing in adulthood.

Medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD) plays a crucial role in mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation, a process vital for generating energy during extended fasting or high-energy demand periods. This process, especially important when liver glycogen is depleted, supports hepatic ketogenesis. The specific step catalyzed by MCAD involves the dehydrogenation of acyl-CoA. This step converts medium-chain acyl-CoA to trans-2-enoyl-CoA, which is then further metabolized to produce energy in the form of ATP.

Symptoms

- Affected children, who seem healthy initially, may experience symptoms like low blood sugar without ketones (hypoketotic hypoglycemia) and vomiting

- Can escalate to lethargy, seizures and coma, typically triggered by illness

- Acute episodes may also involve enlarged liver (hepatomegaly) and liver issues

- Sudden death

Treatments

- Administering simple carbohydrates

- Avoiding fasting

- Frequent feedings for infants

- For toddlers, a diet with less than 30% of total energy from fat

- Administering 2 g/kg of uncooked cornstarch at bedtime for sufficient overnight glucose

- Preventing hypoglycemia, especially due to excessive fasting.

- Avoiding infant formulas with medium-chain triglycerides as the main fat source

Long-chain hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (LCHAD) deficiency

[edit]Long-chain hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (LCHAD) deficiency[19] is a mitochondrial effect of impaired enzyme function.

LCHAD performs the dehydrogenation of hydroxyacyl-CoA derivatives, facilitating the removal of hydrogen and the formation of a keto group. This reaction is essential for the subsequent steps in beta oxidation that lead to the production of acetyl-CoA, NADH, and FADH2, which are important for generating ATP, the energy currency of the cell.

Long-chain hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (LCHAD) deficiency is a condition that affects mitochondrial function due to enzyme impairments. LCHAD deficiency is specifically caused by a shortfall in the enzyme long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase. This leads to the body's inability to transform specific fats into energy, especially during fasting periods.

Symptoms

- Severe Phenotype: symptoms appear soon after birth and include hypoglycemia, hepatomegaly, brain dysfunction (encephalopathy) and often cardiomyopathy

- Intermediate Phenotype: characterized by hypoketotic hypoglycemia and is triggered by infection or fasting during infancy

- Mild (Late-Onset) Phenotype: presents as muscle weakness (myopathy) and nerve disease (neuropathy)

- Long-Term Complications: can include peripheral neuropathy and eye damage (retinopathy)

Treatments

- Regular feeding to avoid fasting

- Use of medium-chain triglyceride (MCT) or triheptanoin supplements and carnitine supplements

- Low-fat diet

- Hospitalization with intravenous fluids containing at least 10% dextrose

- Bicarbonate therapy for severe metabolic acidosis

- Management of high ammonia levels and muscle breakdown

- Cardiomyopathy management

- Regular monitoring of nutrition, blood and liver tests with annual fatty acid profile

- Growth, development, heart and neurological assessments and eye evaluations

Very long-chain acyl-Coenzyme A dehydrogenase (VLCAD) deficiency

[edit]Very long-chain acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase deficiency (VLCAD deficiency) is a genetic disorder that affects the body's ability to break down certain fats. In the β-oxidation cycle, VLCAD's role involves the removal of two hydrogen atoms from the acyl-CoA molecule, forming a double bond and converting it into trans-2-enoyl-CoA. This crucial first step in the cycle is essential for the fatty acid to undergo further processing and energy production. When there is a deficiency in VLCAD, the body struggles to effectively break down long-chain fatty acids. This can lead to a buildup of these fats and a shortage of energy, particularly during periods of fasting or increased physical activity.[20]

Symptoms

- Severe Early-Onset Cardiac and Multiorgan Failure Form: symptoms appear within days of birth and include hypertrophic/dilated cardiomyopathy, fluid around heart (pericardial effusion), heart rhythm problems (arrhythmias), hepatomegaly and occasional intermittent hypoglycemia

- Hepatic or Hypoketotic Hypoglycemic Form: typically appears in early childhood with hypoketotic hypoglycemia

- Later-Onset Episodic Myopathic Form: presents with muscle breakdown after exercise (intermittent rhabdomyolysis), muscle cramps and pain, exercise intolerance and low blood sugar

Treatments

- Low-fat diet

- Use of medium-chain triglyceride (MCT) supplements

- Regular, frequent feeding, especially for infants and children

- Snacks high in complex carbohydrates before bedtime

- Guided and limited exercise for older individuals

- Administration of high-energy fluids intravenously

- Avoiding L-carnitine and IV fats

- Plenty of fluids and urine alkalization for muscle breakdown

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Anderson, Courtney M.; Stahl, Andreas (2013). "SLC27 fatty acid transport proteins". Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 34 (2–3): 516–528. doi:10.1016/j.mam.2012.07.010. PMC 3602789. PMID 23506886.

- ^ Houten, Sander Michel; Wanders, Ronald J. A. (2010). "A general introduction to the biochemistry of mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation". Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease. 33 (5): 469–477. doi:10.1007/s10545-010-9061-2. ISSN 0141-8955. PMC 2950079. PMID 20195903.

- ^ Talley, Jacob T.; Mohiuddin, Shamim S. (2023), "Biochemistry, Fatty Acid Oxidation", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 32310462, retrieved 2023-12-03

- ^ Nelson DL, Cox MM (2005). Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry (4th ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman and Company. pp. 648–649. ISBN 978-0-7167-4339-2.

- ^ Rodwell VW. Harper's Illustrated Biochemistry (31st ed.). McGraw-Hill Publishing Company.

- ^ Schulz, Horst (1991-01-01), Vance, Dennis E.; Vance, Jean E. (eds.), Chapter 3 Oxidation of fatty acids, New Comprehensive Biochemistry, vol. 20, Elsevier, pp. 87–110, doi:10.1016/s0167-7306(08)60331-2, ISBN 978-0-444-89321-5, retrieved 2023-12-03

- ^ King M. "Gluconeogenesis: Synthesis of New Glucose". Subsection: "Propionate". themedicalbiochemistrypage.org, LLC. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ^ Schulz, Horst (1991-01-28). "Beta oxidation of fatty acids". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Lipids and Lipid Metabolism. 1081 (2): 109–120. doi:10.1016/0005-2760(91)90015-A. ISSN 0005-2760. PMID 1998729.

- ^ Singh I (February 1997). "Biochemistry of peroxisomes in health and disease". Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 167 (1–2): 1–29. doi:10.1023/A:1006883229684. PMID 9059978. S2CID 22864478.

- ^ Gibson GG, Lake BG (2013-04-08). Peroxisomes: Biology and Importance in Toxicology and Medicine. CRC Press. pp. 69–. ISBN 978-0-203-48151-6.

- ^ Lazarow PB (March 1978). "Rat liver peroxisomes catalyze the beta oxidation of fatty acids". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 253 (5): 1522–8. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)34897-4. PMID 627552.

- ^ Bai J, Cederbaum AI (2001). "Mitochondrial catalase and oxidative injury". Biological Signals and Receptors. 10 (3–4): 3189–199. doi:10.1159/000046887. PMID 11351128. S2CID 33795198.

- ^ a b c d Rodwell, Victor (2015). Harper's illustrated Biochemistry, 30th edition. USA: McGraw Hill Education. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-07-182537-5.

- ^ Jain P, Singh S, Arya A (January 2021). "A student centric method for calculation of fatty acid energetics: Integrated formula and web tool". Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education. 1 (1): 492–499. doi:10.1002/bmb.21486. PMID 33427394. S2CID 231577993.

- ^ "Biosynthesis of Iso-Fatty Acids in Myxobacteria: Iso-Even Fatty Acids Are Derived by a-Oxidation from Iso-Odd Fatty Acids". doi:10.1021/ja043570y.s001. Retrieved 2023-11-07.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Tein I (2013). "Disorders of fatty acid oxidation". Pediatric Neurology Part III. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol. 113. pp. 1675–88. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-59565-2.00035-6. ISBN 9780444595652. PMID 23622388.

- ^ Ezzeddini R, Taghikhani M, Salek Farrokhi A, Somi MH, Samadi N, Esfahani A, Rasaee, MJ (May 2021). "Downregulation of fatty acid oxidation by involvement of HIF-1α and PPARγ in human gastric adenocarcinoma and its related clinical significance". Journal of Physiology and Biochemistry. 77 (2): 249–260. doi:10.1007/s13105-021-00791-3. PMID 33730333. S2CID 232300877.

- ^ Vishwanath, Vijay A. (2016). "Fatty Acid Beta-Oxidation Disorders: A Brief Review". Annals of Neurosciences. 23 (1): 51–55. doi:10.1159/000443556. ISSN 0972-7531. PMC 4934411. PMID 27536022.

- ^ Prasun, Pankaj; LoPiccolo, Mary Kate; Ginevic, Ilona (1993). "Long-Chain Hydroxyacyl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency / Trifunctional Protein Deficiency". GeneReviews. PMID 36063482.

- ^ Leslie, Nancy D.; Saenz-Ayala, Sofia (1993), Adam, Margaret P.; Feldman, Jerry; Mirzaa, Ghayda M.; Pagon, Roberta A. (eds.), "Very Long-Chain Acyl-Coenzyme A Dehydrogenase Deficiency", GeneReviews®, Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle, PMID 20301763, retrieved 2023-12-04

Further reading

[edit]- Berg JM, Tymoczko JL, Stryer L (2002). "Certain Fatty Acids Require Additional Steps for Degradation". Biochemistry (5th ed.). New York: W H Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-4684-3.

External links

[edit]- Silva P. "The chemical logic behind fatty acid metabolism". Universidade Fernando Pessoa. Archived from the original on 16 March 2010.

- "Fatty acid oxidation animation". Cengage Learning. Archived from the original on 2012-05-08. Retrieved 2007-05-02.

- Jain, P.; Singh, S.; Arya, A. (2021). "Integrated formulae for calculating fatty acid ATP yield". Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education. 49 (3): 492–499. doi:10.1002/bmb.21486. PMID 33427394. S2CID 231577993.