Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Metalloprotein

View on Wikipedia

Metalloprotein is a generic term for a protein that contains a metal ion cofactor.[1][2] A large proportion of all proteins are part of this category. For instance, at least 1000 human proteins (out of ~20,000) contain zinc-binding protein domains[3] although there may be up to 3000 human zinc metalloproteins.[4]

Abundance

[edit]It is estimated that approximately half of all proteins contain a metal.[5] In another estimate, about one quarter to one third of all proteins are proposed to require metals to carry out their functions.[6] Thus, metalloproteins have many different functions in cells, such as storage and transport of proteins, enzymes and signal transduction proteins, or infectious diseases.[7]

Most metals in the human body are bound to proteins. For instance, the relatively high concentration of iron in the human body is mostly due to the iron in hemoglobin.

| Liver | Kidney | Lung | Heart | Brain | Muscle | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mn (manganese) | 138 | 79 | 29 | 27 | 22 | <4-40 |

| Fe (iron) | 16,769 | 7,168 | 24,967 | 5,530 | 4,100 | 3,500 |

| Co (cobalt) | <2-13 | <2 | <2-8 | --- | <2 | 150 (?) |

| Ni (nickel) | <5 | <5-12 | <5 | <5 | <5 | <15 |

| Cu (copper) | 882 | 379 | 220 | 350 | 401 | 85-305 |

| Zn (zinc) | 5,543 | 5,018 | 1,470 | 2,772 | 915 | 4,688 |

Coordination chemistry principles

[edit]In metalloproteins, metal ions are usually coordinated by nitrogen, oxygen or sulfur centers belonging to amino acid residues of the protein. These donor groups are often provided by side-chains on the amino acid residues. Especially important are the imidazole substituent in histidine residues, thiolate substituents in cysteine residues, and carboxylate groups provided by aspartate. Given the diversity of the metalloproteome, virtually all amino acid residues have been shown to bind metal centers. The peptide backbone also provides donor groups; these include deprotonated amides and the amide carbonyl oxygen centers. Lead(II) binding in natural and artificial proteins has been reviewed.[9]

In addition to donor groups that are provided by amino acid residues, many organic cofactors function as ligands. Perhaps most famous are the tetradentate N4 macrocyclic ligands incorporated into the heme protein. Inorganic ligands such as sulfide and oxide are also common.

Storage and transport metalloproteins

[edit]These are the second stage product of protein hydrolysis obtained by treatment with slightly stronger acids and alkalies.

Oxygen carriers

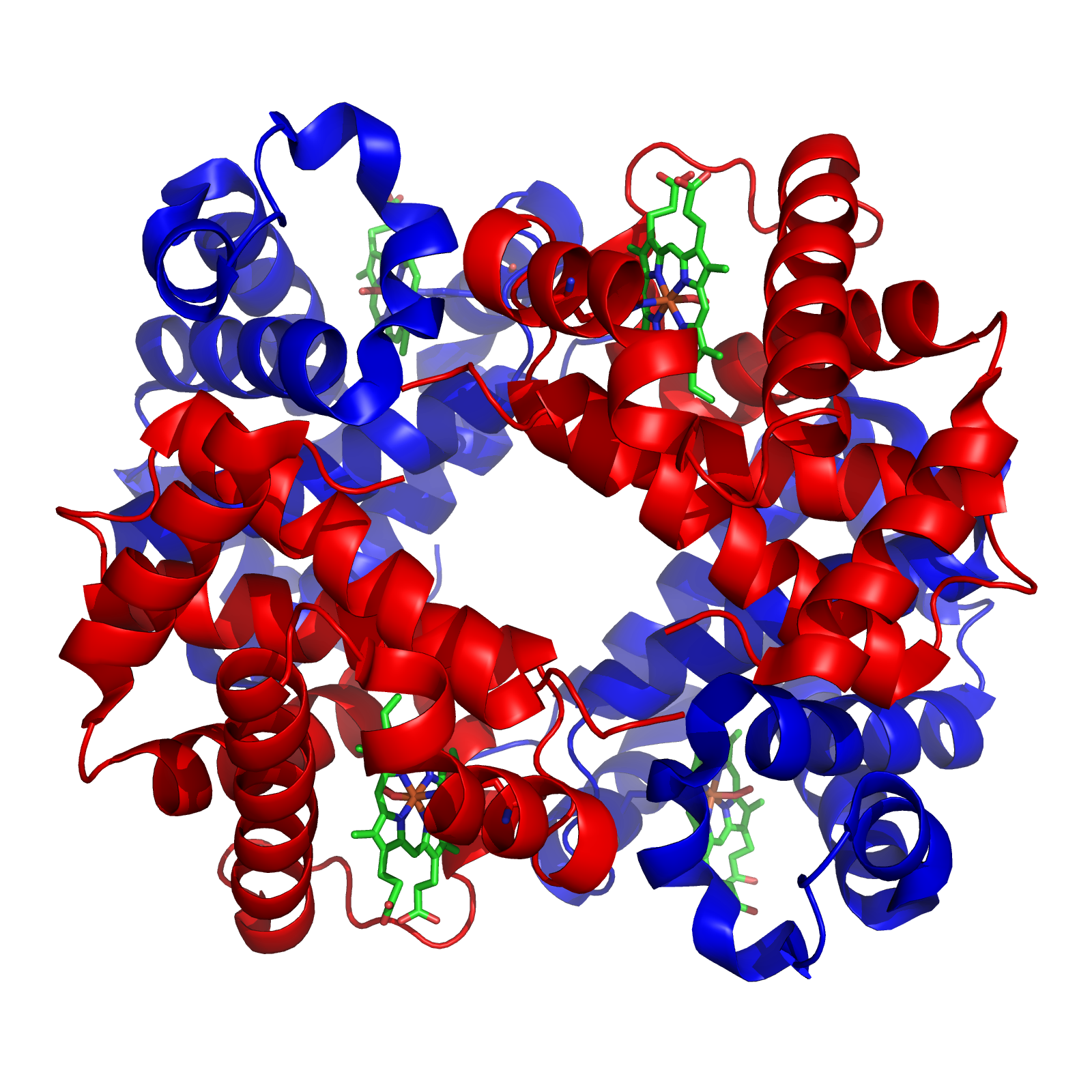

[edit]Hemoglobin, which is the principal oxygen-carrier in humans, has four subunits in which the iron(II) ion is coordinated by the planar macrocyclic ligand protoporphyrin IX (PIX) and the imidazole nitrogen atom of a histidine residue. The sixth coordination site contains a water molecule or a dioxygen molecule. By contrast the protein myoglobin, found in muscle cells, has only one such unit. The active site is located in a hydrophobic pocket. This is important as without it the iron(II) would be irreversibly oxidized to iron(III). The equilibrium constant for the formation of HbO2 is such that oxygen is taken up or released depending on the partial pressure of oxygen in the lungs or in muscle. In hemoglobin the four subunits show a cooperativity effect that allows for easy oxygen transfer from hemoglobin to myoglobin.[10]

In both hemoglobin and myoglobin it is sometimes incorrectly stated that the oxygenated species contains iron(III). It is now known that the diamagnetic nature of these species is because the iron(II) atom is in the low-spin state. In oxyhemoglobin the iron atom is located in the plane of the porphyrin ring, but in the paramagnetic deoxyhemoglobin the iron atom lies above the plane of the ring.[10] This change in spin state is a cooperative effect due to the higher crystal field splitting and smaller ionic radius of Fe2+ in the oxyhemoglobin moiety.

Hemerythrin is another iron-containing oxygen carrier. The oxygen binding site is a binuclear iron center. The iron atoms are coordinated to the protein through the carboxylate side chains of a glutamate and aspartate and five histidine residues. The uptake of O2 by hemerythrin is accompanied by two-electron oxidation of the reduced binuclear center to produce bound peroxide (OOH−). The mechanism of oxygen uptake and release have been worked out in detail.[11][12]

Hemocyanins carry oxygen in the blood of most mollusks, and some arthropods such as the horseshoe crab. They are second only to hemoglobin in biological popularity of use in oxygen transport. On oxygenation the two copper(I) atoms at the active site are oxidized to copper(II) and the dioxygen molecules are reduced to peroxide, O2−

2.[13][14]

Chlorocruorin (as the larger carrier erythrocruorin) is an oxygen-binding hemeprotein present in the blood plasma of many annelids, particularly certain marine polychaetes.

Cytochromes

[edit]Oxidation and reduction reactions are not common in organic chemistry as few organic molecules can act as oxidizing or reducing agents. Iron(II), on the other hand, can easily be oxidized to iron(III). This functionality is used in cytochromes, which function as electron-transfer vectors. The presence of the metal ion allows metalloenzymes to perform functions such as redox reactions that cannot easily be performed by the limited set of functional groups found in amino acids.[15] The iron atom in most cytochromes is contained in a heme group. The differences between those cytochromes lies in the different side-chains. For instance cytochrome a has a heme a prosthetic group and cytochrome b has a heme b prosthetic group. These differences result in different Fe2+/Fe3+ redox potentials such that various cytochromes are involved in the mitochondrial electron transport chain.[16]

Cytochrome P450 enzymes perform the function of inserting an oxygen atom into a C−H bond, an oxidation reaction.[17][18]

Rubredoxin

[edit]

Rubredoxin is an electron-carrier found in sulfur-metabolizing bacteria and archaea. The active site contains an iron ion coordinated by the sulfur atoms of four cysteine residues forming an almost regular tetrahedron. Rubredoxins perform one-electron transfer processes. The oxidation state of the iron atom changes between the +2 and +3 states. In both oxidation states the metal is high spin, which helps to minimize structural changes.

Plastocyanin

[edit]

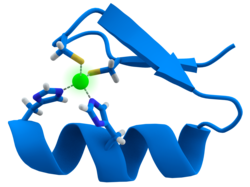

Plastocyanin is one of the family of blue copper proteins that are involved in electron transfer reactions. The copper-binding site is described as distorted trigonal pyramidal.[19] The trigonal plane of the pyramidal base is composed of two nitrogen atoms (N1 and N2) from separate histidines and a sulfur (S1) from a cysteine. Sulfur (S2) from an axial methionine forms the apex. The distortion occurs in the bond lengths between the copper and sulfur ligands. The Cu−S1 contact is shorter (207 pm) than Cu−S2 (282 pm). The elongated Cu−S2 bonding destabilizes the Cu(II) form and increases the redox potential of the protein. The blue color (597 nm peak absorption) is due to the Cu−S1 bond where S(pπ) to Cu(dx2−y2) charge transfer occurs.[20]

In the reduced form of plastocyanin, His-87 will become protonated with a pKa of 4.4. Protonation prevents it acting as a ligand and the copper site geometry becomes trigonal planar.

Metal-ion storage and transfer

[edit]Iron

[edit]Iron is stored as iron(III) in ferritin. The exact nature of the binding site has not yet been determined. The iron appears to be present as a hydrolysis product such as FeO(OH). Iron is transported by transferrin whose binding site consists of two tyrosines, one aspartic acid and one histidine.[21] The human body has no controlled mechanism for excretion of iron.[22] This can lead to iron overload problems in patients treated with blood transfusions, as, for instance, with β-thalassemia. Iron is actually excreted in urine[23] and is also concentrated in bile[24] which is excreted in feces.[25]

Copper

[edit]Ceruloplasmin is the major copper-carrying protein in the blood. Ceruloplasmin exhibits oxidase activity, which is associated with possible oxidation of Fe(II) into Fe(III), therefore assisting in its transport in the blood plasma in association with transferrin, which can carry iron only in the Fe(III) state.

Calcium

[edit]Osteopontin is involved in mineralization in the extracellular matrices of bones and teeth.

Metalloenzymes

[edit]Metalloenzymes all have one feature in common, namely that the metal ion is bound to the protein with one labile coordination site. As with all enzymes, the shape of the active site is crucial. The metal ion is usually located in a pocket whose shape fits the substrate. The metal ion catalyzes reactions that are difficult to achieve in organic chemistry.

Carbonic anhydrase

[edit]

In aqueous solution, carbon dioxide forms carbonic acid

- CO2 + H2O ⇌ H2CO3

This reaction is very slow in the absence of a catalyst, but quite fast in the presence of the hydroxide ion

- CO2 + OH− ⇌ HCO−

3

A reaction similar to this is almost instantaneous with carbonic anhydrase. The structure of the active site in carbonic anhydrases is well known from a number of crystal structures. It consists of a zinc ion coordinated by three imidazole nitrogen atoms from three histidine units. The fourth coordination site is occupied by a water molecule. The coordination sphere of the zinc ion is approximately tetrahedral. The positively-charged zinc ion polarizes the coordinated water molecule, and nucleophilic attack by the negatively-charged hydroxide portion on carbon dioxide proceeds rapidly. The catalytic cycle produces the bicarbonate ion and the hydrogen ion[2] as the equilibrium:

- H2CO3 ⇌ HCO−

3 + H+

favouring dissociation of carbonic acid at biological pH values.[26]

Vitamin B12-dependent enzymes

[edit]The cobalt-containing Vitamin B12 (also known as cobalamin) catalyzes the transfer of methyl (−CH3) groups between two molecules, which involves the breaking of C−C bonds, a process that is energetically expensive in organic reactions. The metal ion lowers the activation energy for the process by forming a transient Co−CH3 bond.[27] The structure of the coenzyme was famously determined by Dorothy Hodgkin and co-workers, for which she received a Nobel Prize in Chemistry.[28] It consists of a cobalt(II) ion coordinated to four nitrogen atoms of a corrin ring and a fifth nitrogen atom from an imidazole group. In the resting state there is a Co−C sigma bond with the 5′ carbon atom of adenosine.[29] This is a naturally occurring organometallic compound, which explains its function in trans-methylation reactions, such as the reaction carried out by methionine synthase.

Nitrogenase (nitrogen fixation)

[edit]The fixation of atmospheric nitrogen is an energy-intensive process, as it involves breaking the very stable triple bond between the nitrogen atoms. The nitrogenases catalyze the process. One such enzyme occurs in Rhizobium bacteria. There are three components to its action: a molybdenum atom at the active site, iron–sulfur clusters that are involved in transporting the electrons needed to reduce the nitrogen, and an abundant energy source in the form of magnesium ATP. This last is provided by a mutualistic symbiosis between the bacteria and a host plant, often a legume. The reaction may be written symbolically as

where Pi stands for inorganic phosphate. The precise structure of the active site has been difficult to determine. It appears to contain a MoFe7S8 cluster that is able to bind the dinitrogen molecule and, presumably, enable the reduction process to begin.[30] Some species of bacteria and archaea have also been shown to have Vanadium nitrogenases, which contain a VFe3S4 cluster and allows for an alternative pathway of nitrogen fixation in Molybdenum-deficient conditions.[31] The electrons are transported by the associated "P" cluster, which contains two cubical Fe4S4 clusters joined by sulfur bridges.[32]

Superoxide dismutase

[edit]

The superoxide ion, O−

2 is generated in biological systems by reduction of molecular oxygen. It has an unpaired electron, so it behaves as a free radical. It is a powerful oxidizing agent. These properties render the superoxide ion very toxic and are deployed to advantage by phagocytes to kill invading microorganisms. Otherwise, the superoxide ion must be destroyed before it does unwanted damage in a cell. The superoxide dismutase enzymes perform this function very efficiently.[33]

The formal oxidation state of the oxygen atoms is −1⁄2. In solutions at neutral pH, the superoxide ion disproportionates to molecular oxygen and hydrogen peroxide.

- 2 O−

2 + 2 H+ → O2 + H2O2

In biology this type of reaction is called a dismutation reaction. It involves both oxidation and reduction of superoxide ions. The superoxide dismutase (SOD) group of enzymes increase the rate of reaction to near the diffusion-limited rate.[34] The key to the action of these enzymes is a metal ion with variable oxidation state that can act either as an oxidizing agent or as a reducing agent.

- Oxidation: M(n+1)+ + O−

2 → Mn+ + O2 - Reduction: Mn+ + O−

2 + 2 H+ → M(n+1)+ + H2O2.

In human SOD, the active metal is copper, as Cu(II) or Cu(I), coordinated tetrahedrally by four histidine residues. This enzyme also contains zinc ions for stabilization and is activated by copper chaperone for superoxide dismutase (CCS). Other isozymes may contain iron, manganese or nickel. The activity of Ni-SOD involves nickel(III), an unusual oxidation state for this element. The active site nickel geometry cycles from square planar Ni(II), with thiolate (Cys2 and Cys6) and backbone nitrogen (His1 and Cys2) ligands, to square pyramidal Ni(III) with an added axial His1 side chain ligand.[35]

Chlorophyll-containing proteins

[edit]

Chlorophyll plays a crucial role in photosynthesis. It contains a magnesium enclosed in a chlorin ring. However, the magnesium ion is not directly involved in the photosynthetic function and can be replaced by other divalent ions with little loss of activity. Rather, the photon is absorbed by the chlorin ring, whose electronic structure is well-adapted for this purpose.

Initially, the absorption of a photon causes an electron to be excited into a singlet state of the Q band. The excited state undergoes an intersystem crossing from the singlet state to a triplet state in which there are two electrons with parallel spin. This species is, in effect, a free radical, and is very reactive and allows an electron to be transferred to acceptors that are adjacent to the chlorophyll in the chloroplast. In the process chlorophyll is oxidized. Later in the photosynthetic cycle, chlorophyll is reduced back again. This reduction ultimately draws electrons from water, yielding molecular oxygen as a final oxidation product.

Hydrogenase

[edit]Hydrogenases are subclassified into three different types based on the active site metal content: iron–iron hydrogenase, nickel–iron hydrogenase, and iron hydrogenase.[36] All hydrogenases catalyze reversible H2 uptake, but while the [FeFe] and [NiFe] hydrogenases are true redox catalysts, driving H2 oxidation and H+ reduction

- H2 ⇌ 2 H+ + 2 e−

the [Fe] hydrogenases catalyze the reversible heterolytic cleavage of H2.

- H2 ⇌ H+ + H−

Ribozyme and deoxyribozyme

[edit]Since discovery of ribozymes by Thomas Cech and Sidney Altman in the early 1980s, ribozymes have been shown to be a distinct class of metalloenzymes.[37] Many ribozymes require metal ions in their active sites for chemical catalysis; hence they are called metalloenzymes. Additionally, metal ions are essential for structural stabilization of ribozymes. Group I intron is the most studied ribozyme which has three metals participating in catalysis.[38] Other known ribozymes include group II intron, RNase P, and several small viral ribozymes (such as hammerhead, hairpin, HDV, and VS) and the large subunit of ribosomes. Several classes of ribozymes have been described.[39]

Deoxyribozymes, also called DNAzymes or catalytic DNA, are artificial DNA-based catalysts that were first produced in 1994.[40] Almost all DNAzymes require metal ions. Although ribozymes mostly catalyze cleavage of RNA substrates, a variety of reactions can be catalyzed by DNAzymes including RNA/DNA cleavage, RNA/DNA ligation, amino acid phosphorylation and dephosphorylation, and carbon–carbon bond formation.[41] Yet, DNAzymes that catalyze RNA cleavage reaction are the most extensively explored ones. 10-23 DNAzyme, discovered in 1997, is one of the most studied catalytic DNAs with clinical applications as a therapeutic agent.[42] Several metal-specific DNAzymes have been reported including the GR-5 DNAzyme (lead-specific),[43] the CA1-3 DNAzymes (copper-specific), the 39E DNAzyme (uranyl-specific)[44] and the NaA43 DNAzyme (sodium-specific).[45]

Signal-transduction metalloproteins

[edit]Calmodulin

[edit]

Calmodulin is an example of a signal-transduction protein. It is a small protein that contains four EF-hand motifs, each of which is able to bind a Ca2+ ion.

In an EF-hand loop protein domain, the calcium ion is coordinated in a pentagonal bipyramidal configuration. Six glutamic acid and aspartic acid residues involved in the binding are in positions 1, 3, 5, 7 and 9 of the polypeptide chain. At position 12, there is a glutamate or aspartate ligand that behaves as a bidentate ligand, providing two oxygen atoms. The ninth residue in the loop is necessarily glycine due to the conformational requirements of the backbone. The coordination sphere of the calcium ion contains only carboxylate oxygen atoms and no nitrogen atoms. This is consistent with the hard nature of the calcium ion.

The protein has two approximately symmetrical domains, separated by a flexible "hinge" region. Binding of calcium causes a conformational change to occur in the protein. Calmodulin participates in an intracellular signaling system by acting as a diffusible second messenger to the initial stimuli.[46][47]

Troponin

[edit]In both cardiac and skeletal muscles, muscular force production is controlled primarily by changes in the intracellular calcium concentration. In general, when calcium rises, the muscles contract and, when calcium falls, the muscles relax. Troponin, along with actin and tropomyosin, is the protein complex to which calcium binds to trigger the production of muscular force.

Transcription factors

[edit]

Many transcription factors contain a structure known as a zinc finger, a structural module in which a region of protein folds around a zinc ion. The zinc does not directly contact the DNA that these proteins bind to. Instead, the cofactor is essential for the stability of the tightly folded protein chain.[48] In these proteins, the zinc ion is usually coordinated by pairs of cysteine and histidine side-chains.

Other metalloenzymes

[edit]There are two types of carbon monoxide dehydrogenase: one contains iron and molybdenum, the other contains iron and nickel. Parallels and differences in catalytic strategies have been reviewed.[49]

Pb2+ (lead) can replace Ca2+ (calcium) as, for example, with calmodulin or Zn2+ (zinc) as with metallocarboxypeptidases.[50]

Some other metalloenzymes are given in the following table, according to the metal involved.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Banci L (2013). "Metallomics and the Cell: Some Definitions and General Comments". In Sigel A, Sigel H, Sigel RK (eds.). Metallomics and the Cell. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 12. Springer. pp. 1–13. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5561-1_1. ISBN 978-94-007-5561-1. PMID 23595668.

- ^ a b Shriver DF, Atkins PW (1999). "Charper 19, Bioinorganic chemistry". Inorganic chemistry (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-850330-9.

- ^ Human reference proteome in Uniprot, accessed 12 Jan 2018

- ^ Andreini C, Banci L, Bertini I, Rosato A (November 2006). "Zinc through the three domains of life". Journal of Proteome Research. 5 (11): 3173–8. doi:10.1021/pr0603699. PMID 17081069.

- ^ Thomson AJ, Gray HB (1998). "Bioinorganic chemistry" (PDF). Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 2 (2): 155–158. doi:10.1016/S1367-5931(98)80056-2. PMID 9667942.

- ^ Waldron KJ, Robinson NJ (January 2009). "How do bacterial cells ensure that metalloproteins get the correct metal?". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 7 (1): 25–35. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2057. PMID 19079350. S2CID 7253420.

- ^ Carver PL (2013). "Metal Ions and Infectious Diseases. An Overview from the Clinic". In Sigel A, Sigel H, Sigel RK (eds.). Interrelations between Essential Metal Ions and Human Diseases. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 13. Springer. pp. 1–28. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-7500-8_1. ISBN 978-94-007-7499-5. PMID 24470087.

- ^ Maret W (February 2010). "Metalloproteomics, metalloproteomes, and the annotation of metalloproteins". Metallomics. 2 (2): 117–25. doi:10.1039/b915804a. PMID 21069142.

- ^ Cangelosi V, Ruckthong L, Pecoraro VL (2017). "Chapter 10. Lead(II) Binding in Natural and Artificial Proteins". In Astrid S, Helmut S, Sigel RK (eds.). Lead: Its Effects on Environment and Health. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 17. de Gruyter. pp. 271–318. doi:10.1515/9783110434330-010. ISBN 9783110434330. PMC 5771651. PMID 28731303.

- ^ a b Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. doi:10.1016/C2009-0-30414-6. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8. Fig.25.7, p 1100 illustrates the structure of deoxyhemoglobin

- ^ Stenkamp, R. E. (1994). "Dioxygen and hemerythrin". Chem. Rev. 94 (3): 715–726. doi:10.1021/cr00027a008.

- ^ Wirstam M, Lippard SJ, Friesner RA (April 2003). "Reversible dioxygen binding to hemerythrin". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 125 (13): 3980–7. Bibcode:2003JAChS.125.3980W. doi:10.1021/ja017692r. PMID 12656634.

- ^ Karlin K, Cruse RW, Gultneh Y, Farooq A, Hayes JC, Zubieta J (1987). "Dioxygen–copper reactivity. Reversible binding of O2 and CO to a phenoxo-bridged dicopper(I) complex". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 109 (9): 2668–2679. Bibcode:1987JAChS.109.2668K. doi:10.1021/ja00243a019.

- ^ Kitajima N, Fujisawa K, Fujimoto C, Morooka Y, Hashimoto S, Kitagawa T, Toriumi K, Tatsumi K, Nakamura A (1992). "A new model for dioxygen binding in hemocyanin. Synthesis, characterization, and molecular structure of the μ-η2:η2-peroxo dinuclear copper(II) complexes, [Cu(Hb(3,5-R2pz)3)]2(O2) (R = isopropyl and Ph)". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 114 (4): 1277–1291. doi:10.1021/ja00030a025.

- ^ Messerschmidt A, Huber R, Wieghardt K, Poulos T (2001). Handbook of Metalloproteins. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-62743-2.

- ^ Moore GR, Pettigrew GW (1990). Cytochrome c: Structural and Physicochemical Aspects. Berlin: Springer.

- ^ Sigel A, Sigel H, Sigel RK, eds. (2007). The Ubiquitous Roles of Cytochrome 450 Proteins. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 3. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-01672-5.

- ^ Ortiz de Montellano P (2005). Cytochrome P450 Structure, Mechanism, and Biochemistry (3rd ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-0-306-48324-0.

- ^ Colman PM, Freeman HC, Guss JM, Murata M, Norris VA, Ramshaw JA, Venkatappa MP (1978). "X-Ray Crystal-Structure Analysis of Plastocyanin at 2.7 Å Resolution". Nature. 272 (5651): 319–324. Bibcode:1978Natur.272..319C. doi:10.1038/272319a0. S2CID 4226644.

- ^ Solomon EI, Gewirth AA, Cohen SL (1986). Spectroscopic Studies of Active Sites. Blue Copper and Electronic Structural Analogs. Vol. 307. pp. 236–266. doi:10.1021/bk-1986-0307.ch016. ISBN 978-0-8412-0971-8.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Anderson BF, Baker HM, Dodson EJ, Norris GE, Rumball SV, Waters JM, Baker EN (April 1987). "Structure of human lactoferrin at 3.2-A resolution". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 84 (7): 1769–73. doi:10.1073/pnas.84.7.1769. PMC 304522. PMID 3470756.

- ^ Wallace, Daniel F (May 2016). "The Regulation of Iron Absorption and Homeostasis". The Clinical Biochemist Reviews. 37 (2): 51–62. ISSN 0159-8090. PMC 5198508. PMID 28303071.

- ^ Rodríguez E, Díaz C (December 1995). "Iron, copper and zinc levels in urine: relationship to various individual factors". Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology. 9 (4): 200–9. Bibcode:1995JTEMB...9..200R. doi:10.1016/S0946-672X(11)80025-8. PMID 8808191.

- ^ Schümann K, Schäfer SG, Forth W (1986). "Iron absorption and biliary excretion of transferrin in rats". Research in Experimental Medicine. Zeitschrift für die Gesamte Experimentelle Medizin Einschliesslich Experimenteller Chirurgie. 186 (3): 215–9. doi:10.1007/BF01852047. PMID 3738220. S2CID 7925719.

- ^ "Biliary excretion of waste products". Archived from the original on 2017-03-26. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ Lindskog S (1997). "Structure and mechanism of carbonic anhydrase". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 74 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1016/S0163-7258(96)00198-2. PMID 9336012.

- ^ Sigel A, Sigel H, Sigel RK, eds. (2008). Metal–carbon bonds in enzymes and cofactors. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 6. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-84755-915-9.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1964". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 2008-10-06.

- ^ Hodgkin, D. C. (1965). "The Structure of the Corrin Nucleus from X-ray Analysis". Proc. R. Soc. A. 288 (1414): 294–305. Bibcode:1965RSPSA.288..294H. doi:10.1098/rspa.1965.0219. S2CID 95235740.

- ^ Orme-Johnson, W. H. (1993). Steifel, E. I.; Coucouvannis, D.; Newton, D. C. (eds.). Molybdenum enzymes, cofactors and model systems. Advances in chemistry, Symposium series no. 535. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society. pp. 257. ISBN 9780841227088.

- ^ Djurdjevic, Ivana; Trncik, Christian; Rhode, Michael; Gies, Jacob; Grunau, Katharina; Schneider, Florian; Andrade, Susana LA; Einsle, Oliver (March 23, 2020). "The Cofactors of Nitrogenases". Met Ions Life Sci. doi:10.1515/9783110589757-014. PMID 32851829.

- ^ Chan MK, Kim J, Rees DC (May 1993). "The nitrogenase FeMo-cofactor and P-cluster pair: 2.2 A resolution structures". Science. 260 (5109): 792–4. doi:10.1126/science.8484118. PMID 8484118.

- ^ Packer, L., ed. (2002). Superoxide Dismutase: 349 (Methods in Enzymology). Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-182252-1.

- ^ Heinrich P, Löffler G, Petrides PE (2006). Biochemie und Pathobiochemie (in German). Berlin: Springer. p. 123. ISBN 978-3-540-32680-9.

- ^ Barondeau DP, Kassmann CJ, Bruns CK, Tainer JA, Getzoff ED (June 2004). "Nickel superoxide dismutase structure and mechanism". Biochemistry. 43 (25): 8038–47. doi:10.1021/bi0496081. PMID 15209499.

- ^ Parkin, Alison (2014). "Understanding and Harnessing Hydrogenases, Biological Dihydrogen Catalysts". In Kroneck, Peter M. H.; Sosa Torres, Martha E. (eds.). The Metal-Driven Biogeochemistry of Gaseous Compounds in the Environment. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 14. Springer. pp. 99–124. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-9269-1_5. ISBN 978-94-017-9268-4. PMID 25416392.

- ^ Pyle AM (August 1993). "Ribozymes: a distinct class of metalloenzymes". Science. 261 (5122): 709–14. Bibcode:1993Sci...261..709P. doi:10.1126/science.7688142. PMID 7688142.

- ^ Shan S, Yoshida A, Sun S, Piccirilli JA, Herschlag D (October 1999). "Three metal ions at the active site of the Tetrahymena group I ribozyme". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (22): 12299–304. Bibcode:1999PNAS...9612299S. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.22.12299. PMC 22911. PMID 10535916.

- ^ Weinberg Z, Kim PB, Chen TH, Li S, Harris KA, Lünse CE, Breaker RR (August 2015). "New classes of self-cleaving ribozymes revealed by comparative genomics analysis". Nature Chemical Biology. 11 (8): 606–10. doi:10.1038/nchembio.1846. PMC 4509812. PMID 26167874.

- ^ Breaker RR, Joyce GF (December 1994). "A DNA enzyme that cleaves RNA". Chemistry & Biology. 1 (4): 223–9. doi:10.1016/1074-5521(94)90014-0. PMID 9383394.

- ^ Silverman SK (May 2015). "Pursuing DNA catalysts for protein modification". Accounts of Chemical Research. 48 (5): 1369–79. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00090. PMC 4439366. PMID 25939889.

- ^ Santoro SW, Joyce GF (April 1997). "A general purpose RNA-cleaving DNA enzyme". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 94 (9): 4262–6. Bibcode:1997PNAS...94.4262S. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.9.4262. PMC 20710. PMID 9113977.

- ^ Breaker RR, Joyce GF (December 1994). "A DNA enzyme that cleaves RNA". Chemistry & Biology. 1 (4): 223–9. doi:10.1016/1074-5521(94)90014-0. PMID 9383394.

- ^ Liu J, Brown AK, Meng X, Cropek DM, Istok JD, Watson DB, Lu Y (February 2007). "A catalytic beacon sensor for uranium with parts-per-trillion sensitivity and millionfold selectivity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (7): 2056–61. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.2056L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0607875104. PMC 1892917. PMID 17284609.

- ^ Torabi SF, Wu P, McGhee CE, Chen L, Hwang K, Zheng N, Cheng J, Lu Y (May 2015). "In vitro selection of a sodium-specific DNAzyme and its application in intracellular sensing". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 112 (19): 5903–8. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112.5903T. doi:10.1073/pnas.1420361112. PMC 4434688. PMID 25918425.

- ^ Stevens FC (August 1983). "Calmodulin: an introduction". Canadian Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 61 (8): 906–10. doi:10.1139/o83-115. PMID 6313166.

- ^ Chin D, Means AR (August 2000). "Calmodulin: a prototypical calcium sensor". Trends in Cell Biology. 10 (8): 322–8. doi:10.1016/S0962-8924(00)01800-6. PMID 10884684.

- ^ Berg JM (1990). "Zinc finger domains: hypotheses and current knowledge". Annual Review of Biophysics and Biophysical Chemistry. 19 (1): 405–21. doi:10.1146/annurev.bb.19.060190.002201. PMID 2114117.

- ^ Jeoung JH, Fesseler J, Goetzl S, Dobbek H (2014). "Carbon Monoxide. Toxic Gas and Fuel for Anaerobes and Aerobes: Carbon Monoxide Dehydrogenases". In Kroneck PM, Sosa Torres ME (eds.). The Metal-Driven Biogeochemistry of Gaseous Compounds in the Environment. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 14. Springer. pp. 37–69. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-9269-1_3. ISBN 978-94-017-9268-4. PMID 25416390.

- ^ Aoki K, Murayama K, Hu NH (2017). "Chapter 7. Solid State Structures of Lead Complexes with Relevance for Biological Systems". In Astrid S, Helmut S, Sigel RK (eds.). Lead: Its Effects on Environment and Health. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 17. de Gruyter. pp. 123–200. doi:10.1515/9783110434330-007. ISBN 9783110434330. PMID 28731300.

- ^ Romani, Andrea M. P. (2013). "Magnesium Homeostasis in Mammalian Cells". In Banci, Lucia (ed.). Metallomics and the Cell. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 12. Springer. pp. 69–118. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5561-1_4. ISBN 978-94-007-5561-1. ISSN 1868-0402. PMID 23595671.

- ^ Roth J, Ponzoni S, Aschner M (2013). "Manganese Homeostasis and Transport". In Banci L (ed.). Metallomics and the Cell. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 12. Springer. pp. 169–201. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5561-1_6. ISBN 978-94-007-5561-1. ISSN 1868-0402. PMC 6542352. PMID 23595673.

- ^ Dlouhy AC, Outten CE (2013). "The Iron Metallome in Eukaryotic Organisms". In Banci L (ed.). Metallomics and the Cell. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 12. Springer. pp. 241–78. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5561-1_8. ISBN 978-94-007-5561-1. ISSN 1868-0402. PMC 3924584. PMID 23595675.

- ^ Cracan V, Banerjee R (2013). "Chapter 10 Cobalt and Corrinoid Transport and Biochemistry". In Banci L (ed.). Metallomics and the Cell. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 12. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5561-10_10 (inactive 12 July 2025). ISBN 978-94-007-5561-1. ISSN 1868-0402.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ Sigel A, Sigel H, Sigel RK, eds. (2008). Nickel and Its Surprising Impact in Nature. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 2. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-01671-8.

- ^ Sydor AM, Zambie DB (2013). "Chapter 11. Nickel Metallomics: General Themes Guiding Nickel Homeostasis". In Banci L (ed.). Metallomics and the Cell. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 12. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5561-10_11 (inactive 12 July 2025). ISBN 978-94-007-5561-1. ISSN 1868-0402.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ Vest KE, Hashemi HF, Cobine PA (2013). "Chapter 13. The Copper Metallome in Eukaryotic Cells". In Banci L (ed.). Metallomics and the Cell. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 12. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5561-10_12 (inactive 12 July 2025). ISBN 978-94-007-5561-1. ISSN 1868-0402.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ Maret W (2013). "Chapter 14 Zinc and the Zinc Proteome". In Banci L (ed.). Metallomics and the Cell. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 12. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5561-10_14 (inactive 12 July 2025). ISBN 978-94-007-5561-1. ISSN 1868-0402.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ Peacock AF, Pecoraro V (2013). "Natural and Artificial Proteins Containing Cadmium". In Sigel A, Sigel H, Sigel RK (eds.). Cadmium: From Toxicity to Essentiality. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 11. Springer. pp. 303–337. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5179-8_10. ISBN 978-94-007-5178-1. PMID 23430777.

- ^ Freisinger EF, Vasac M (2013). "Cadmium in Metallothioneins". In Sigel A, Sigel H, Sigel RK (eds.). Cadmium: From Toxicity to Essentiality. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 11. Springer. pp. 339–372. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5179-8_11. ISBN 978-94-007-5178-1. PMID 23430778.

- ^ Mendel, Ralf R. (2013). "Chapter 15. Metabolism of Molybdenum". In Banci, Lucia (ed.). Metallomics and the Cell. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 12. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5561-10_15 (inactive 12 July 2025). ISBN 978-94-007-5561-1. ISSN 1868-0402.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ ten Brink, Felix (2014). "Living on Acetylene. A Primordial Energy Source". In Kroneck, Peter M. H.; Sosa Torres, Martha E. (eds.). The Metal-Driven Biogeochemistry of Gaseous Compounds in the Environment. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 14. Springer. pp. 15–35. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-9269-1_2. ISBN 978-94-017-9268-4. PMID 25416389.

External links

[edit]- Metalloprotein at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Catherine Drennan's Seminar: Snapshots of Metalloproteins

Metalloprotein

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Classification

Metalloproteins are proteins that contain one or more metal ions or metal clusters essential for their biological function, structure, or regulation, with the metals typically bound through coordination to amino acid side chains or cofactors either covalently or non-covalently.[5] These metals, which include transition and non-transition elements such as iron, zinc, copper, calcium, and molybdenum, serve as cofactors that enable diverse roles in cellular processes.[6] In humans, metalloproteins constitute approximately 30-40% of the proteome, highlighting their prevalence and critical importance in physiology.[7][8] The study of metalloproteins traces back to the 19th century, when hemoglobin was identified as an iron-containing protein responsible for oxygen transport in blood, marking one of the earliest recognized examples.[9] Modern structural insights emerged in the 1950s through X-ray crystallography, with the first atomic-resolution structures of myoglobin (1958) and hemoglobin (1960) revealing the precise coordination of heme-bound iron, which revolutionized understanding of metal-protein interactions.[10] These milestones shifted the field from biochemical characterization to detailed mechanistic analysis. Metalloproteins are classified in multiple ways to reflect their diversity. By metal type, they are grouped according to the incorporated element, such as iron-based (e.g., heme proteins like hemoglobin or non-heme iron-sulfur clusters in ferredoxins), zinc-based (e.g., zinc finger transcription factors), copper-based (e.g., blue copper proteins like plastocyanin), calcium-based (e.g., calmodulin for signaling), and molybdenum-based (e.g., nitrogenase for catalysis).[6][11] By function, they fall into categories including catalytic (enzymes like superoxide dismutase), transport and storage (e.g., transferrin for iron), electron transfer (e.g., cytochromes), structural (e.g., stabilizing protein folds), and regulatory (e.g., modulating enzyme activity).[12] By binding site, classifications distinguish heme (porphyrin-coordinated metals, primarily iron) from non-heme sites, and mononuclear (single metal ion) from polynuclear clusters (e.g., Fe-S clusters with 2-4 irons linked by sulfides).[11][13] These schemes underscore the adaptability of metalloproteins, with coordination geometries like octahedral or tetrahedral motifs briefly linking to broader chemical principles.[6]Coordination Chemistry Principles

Metalloproteins feature metal ions bound to protein scaffolds through coordination bonds, where the metal acts as a Lewis acid and protein-derived groups or exogenous molecules serve as Lewis bases. These interactions are governed by principles of coordination chemistry, including ligand donor atom identity, coordination number, and geometry, which dictate the electronic and functional properties of the site. The stability of these complexes arises from electrostatic attractions, covalent contributions, and thermodynamic factors, enabling precise control over reactivity in biological contexts.[14] Common ligands in metalloproteins include side chains from amino acids such as the imidazole nitrogen of histidine, the thiolate sulfur of cysteine, and the carboxylate oxygen of aspartate or glutamate, which provide nitrogen, sulfur, and oxygen donors, respectively. Non-protein ligands, like water molecules or dioxygen, often occupy remaining coordination sites, particularly in dynamic environments. These ligands are selected based on their ability to match the metal's electronic requirements, with histidine being prevalent due to its versatile imidazolate donor.[15][16] Coordination geometries in metalloproteins vary with the metal ion and ligand set, commonly adopting tetrahedral arrangements for zinc sites, octahedral for iron or magnesium, and square planar for copper in certain motifs. These geometries are influenced by ligand field theory, which describes how ligands split the d-orbitals of transition metals, affecting electronic transitions and reactivity. For octahedral complexes, the crystal field stabilization energy (CFSE) quantifies this splitting: where is the number of electrons in the orbitals, is the number in the orbitals, and is the octahedral splitting parameter. This energy stabilization favors specific geometries and oxidation states, enhancing site functionality.[17][14] The stability and selectivity of metal binding are largely explained by the hard-soft acid-base (HSAB) theory, which predicts preferential interactions between hard acids (e.g., high-charge-density ions like Zn²⁺) and hard bases (e.g., oxygen donors from carboxylates) versus soft acids (e.g., Cu⁺) and soft bases (e.g., sulfur from thiolates). Entropy effects further modulate binding, as chelation by multidentate ligands reduces translational and rotational freedom but releases solvent molecules, contributing favorably to the overall free energy. Coordination environment also tunes redox potentials; for instance, soft sulfur ligands stabilize lower oxidation states, shifting potentials to more negative values and facilitating electron transfer.[18][19][20] Spectroscopic methods are essential for characterizing these coordination sites. Ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy probes d-d transitions and charge-transfer bands, revealing geometry and ligand field strength. Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) detects unpaired electrons in paramagnetic metals like Cu²⁺ or Fe³⁺, providing information on spin state and ligand symmetry. Extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) determines metal-ligand distances and coordination numbers with atomic precision, even in non-crystalline samples. These techniques, often used in combination, offer complementary insights into site structure and dynamics.[14][21]Abundance and Distribution

Prevalence in Biological Systems

Metalloproteins are ubiquitous across all domains of life, constituting a significant portion of the proteome in diverse organisms. Estimates indicate that approximately 30% of all proteins in biological systems bind metal ions, with nearly half of all enzymes classified as metalloenzymes that require metal cofactors for catalytic activity.[7][22] In prokaryotes, the prevalence is particularly high, with bioinformatic analyses suggesting that 20-30% of the proteome in model organisms like Escherichia coli involves metal-binding proteins, including around 144 iron-sulfur cluster-containing proteins alone, representing over 3% of the total proteome. This proportion underscores the essential role of metalloproteins in prokaryotic metabolism and survival. The distribution of metalloproteins varies by organism type and environmental niche. They are present in bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes, but adaptations reflect physiological demands; for instance, aerobic bacteria and eukaryotes often feature iron-rich metalloproteins such as heme-containing cytochromes for oxygen handling, while nitrogen-fixing prokaryotes like Rhizobium species express molybdenum-dependent nitrogenase enzymes for N₂ reduction. In eukaryotes, zinc-binding proteins comprise about 9% of the proteome, higher than the 5-6% in prokaryotes, highlighting evolutionary divergences in metal utilization.[23] Within cells, metalloproteins localize to specific compartments based on function. Zinc enzymes, such as carbonic anhydrase, predominate in the cytosol for pH regulation and CO₂ transport, while iron-sulfur clusters are enriched in mitochondria for electron transfer in the respiratory chain. In plant chloroplasts, magnesium ions coordinate chlorophyll within photosystem proteins, enabling light harvesting and photosynthesis.[24] Proteomic analyses, particularly those combining mass spectrometry with inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS), have been instrumental in mapping these distributions and quantifying metal content, revealing previously underappreciated metalloproteins in viruses; for example, several SARS-CoV-2 proteins, including the papain-like protease, feature structural zinc-binding sites essential for viral replication.[25][26] Environmental metal availability profoundly influences metalloprotein expression and adaptation. In iron-limited conditions, bacteria like E. coli upregulate siderophore biosynthesis, such as enterobactin, to scavenge Fe³⁺ for incorporation into iron-dependent proteins like ribonucleotide reductase. Similarly, molybdenum scarcity can repress nitrogenase activity in diazotrophs, demonstrating how metalloproteins enable dynamic responses to nutrient stress.[27]Evolutionary Origins

The evolutionary origins of metalloproteins are rooted in the geochemical conditions of early Earth, where anaerobic oceans approximately 4 billion years ago were rich in bioavailable iron and nickel, facilitating the formation of simple iron-sulfur (Fe-S) clusters as primordial cofactors in prebiotic chemistry.[28] These clusters likely emerged in hydrothermal vent environments, where iron monosulfide minerals promoted the assembly of Fe-S structures essential for early electron transfer processes, predating cellular life.[29] In the last universal common ancestor (LUCA), estimated to have existed around 3.8–4.2 billion years ago, dedicated machineries for Fe-S cluster biosynthesis were already present, supporting metabolic functions in an anaerobic, acetogenic prokaryote.[30] Phylogenetic analyses indicate that these ancient Fe-S proteins, such as ferredoxins, were central to LUCA's energy metabolism, with evidence from comparative genomics showing their conservation across bacterial and archaeal lineages.[31] A pivotal milestone in metalloprotein diversification occurred during the Great Oxidation Event (GOE) around 2.4 billion years ago, when rising atmospheric oxygen levels oxidized soluble Fe²⁺ to insoluble Fe³⁺, reducing iron bioavailability while solubilizing previously inaccessible metals like copper (as Cu²⁺) and zinc.[32] This geochemical shift prompted evolutionary adaptations, enabling the rise of copper- and zinc-dependent proteins; for instance, copper enzymes such as cytochrome c oxidases emerged in aerobic bacteria post-GOE, replacing less efficient iron-based alternatives for oxygen reduction.[33] Similarly, zinc fingers and superoxide dismutases incorporating zinc proliferated in eukaryotes, reflecting a transition from iron-centric to more diverse metal utilization in oxygenated environments.[32] Molybdenum enzymes, integral to anaerobic metabolisms like nitrogen fixation, trace back to early prokaryotes, with phylogenomic studies post-2020 revealing their presence in LUCA and widespread horizontal gene transfer in ancient anaerobes, underscoring molybdenum's role in pre-GOE biogeochemical cycles.[34] Gene duplication and horizontal gene transfer (HGT) further drove the diversification of metalloprotein active sites, allowing adaptation to varying metal availabilities. For example, ancient ferredoxins underwent gene duplication to form modular electron transfer chains, evolving into complex systems like those in modern cytochromes through symmetrical microenvironment pairings.[35] HGT facilitated the spread of metalloprotein genes across domains; bacterial ferredoxins were transferred to archaea and eukaryotes, enabling the integration of Fe-S clusters into diverse respiratory pathways.[36] In molybdenum nitrogenases, HGT events dating to the early Archean distributed genes among prokaryotes, promoting nitrogen metabolism in anaerobic niches.[37] In contemporary contexts, evolutionary pressures from metal pollution have spurred the development of resistance mechanisms, such as cadmium-binding metallothioneins, which evolved from ancient zinc-binding scaffolds to sequester toxic cadmium ions in polluted environments.[38] These proteins, often arising via gene duplication in bacteria and plants exposed to industrial cadmium, exemplify ongoing metalloprotein adaptation to anthropogenic metal toxicity, with enhanced binding affinities conferring survival advantages.[39]Storage and Transport Functions

Oxygen Carriers

Oxygen carriers are metalloproteins specialized for the reversible binding and transport of molecular oxygen (O₂) to tissues, primarily through coordination to transition metal ions within protein active sites. In vertebrates, the most prominent examples are heme-containing proteins, where iron serves as the central metal. Hemoglobin (Hb), a tetrameric protein consisting of two α and two β subunits, facilitates cooperative oxygen binding in red blood cells, enabling efficient uptake in the lungs and release in peripheral tissues.[40] This cooperativity arises from allosteric transitions between tense (T) and relaxed (R) states, allowing the protein to adapt to varying physiological demands.[41] Myoglobin (Mb), in contrast, is a monomeric heme protein found in muscle tissues, functioning primarily as an oxygen storage molecule to support sustained contraction during periods of high demand.[42] Its higher oxygen affinity compared to hemoglobin ensures rapid release to mitochondria under hypoxic conditions. The three-dimensional structure of myoglobin, first elucidated by John Kendrew, revealed a compact globular fold with eight α-helices enclosing the heme prosthetic group.[43] The core mechanism of oxygen binding in these heme proteins involves ferrous iron (Fe²⁺) coordinated within a porphyrin ring. The iron is axially ligated by a proximal histidine residue, leaving a sixth coordination site available for O₂. Upon binding, the Fe²⁺ shifts from high-spin to low-spin, triggering conformational changes that facilitate subsequent bindings in hemoglobin. The overall reaction for hemoglobin oxygenation is represented as: This equilibrium is modulated by allosteric effectors such as 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate (2,3-BPG), which binds to the deoxyhemoglobin T-state in a central cavity, stabilizing it and reducing oxygen affinity to promote unloading in tissues.[44] The tetrameric architecture of hemoglobin, resolved by Max Perutz, underscores how subunit interfaces transmit these allosteric signals.[41] Beyond heme-based carriers, non-heme variants exist in invertebrates. Hemocyanin, a copper-containing oligomer, serves as the primary oxygen transporter in arthropods and mollusks, where it binds O₂ at binuclear Cu(I) sites, turning blue upon oxygenation due to charge-transfer transitions.[45] Each functional unit reversibly binds one O₂ molecule, with assembly into large multi-subunit complexes (up to 48 subunits in some mollusks) enabling high-capacity transport. Hemerythrin, found in marine worms such as sipunculids and priapulids, employs a non-heme diiron center for O₂ binding, forming a peroxo-bridged Fe(III)-Fe(III) complex in the oxygenated state without color change.[46] Physiologically, these proteins ensure tissue oxygenation by exploiting gradients in partial pressure (pO₂) and environmental factors. In hemoglobin, the Bohr effect describes the pH-dependent decrease in oxygen affinity, where lower pH (from CO₂ and H⁺ accumulation in active tissues) protonates specific residues, favoring O₂ release.[47] This heterotropic allostery enhances delivery efficiency, with up to 2.5 protons released per O₂ bound at physiological pH. Disruptions in hemoglobin function, such as the Glu6Val mutation in the β-globin chain causing sickle cell anemia, lead to polymerization of deoxyhemoglobin under low pO₂, resulting in distorted erythrocytes, vaso-occlusion, and hemolytic crises.[48] This single amino acid substitution, identified by Vernon Ingram, exemplifies how point mutations can profoundly impact metalloprotein stability and function.[48]Electron Transfer Proteins

Electron transfer proteins are a vital class of metalloproteins that mediate the movement of electrons in biological processes such as cellular respiration, photosynthesis, and metabolic pathways, primarily through redox-active metal centers including heme iron, iron-sulfur clusters, and copper ions. These proteins enable efficient energy transduction by shuttling electrons between donors and acceptors, often over distances of 10-14 Å via quantum mechanical tunneling, with rates optimized by the protein environment to minimize energy loss. The redox potentials of these metal centers, typically ranging from -0.5 V to +0.5 V versus the standard hydrogen electrode, dictate the thermodynamic favorability of electron flow, while structural features like the secondary coordination sphere fine-tune kinetics and specificity.[11] Cytochromes represent a major family of heme-containing electron transfer proteins, where the iron atom in the porphyrin ring cycles between Fe(II) and Fe(III) states. In mitochondrial respiration, cytochrome c serves as a soluble carrier in the electron transport chain (ETC), transferring electrons from complex III (cytochrome bc1) to complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase), with a standard redox potential of approximately +0.25 V that positions it ideally between ubiquinone (+0.06 V) and oxygen (+0.82 V). This protein exemplifies octahedral iron coordination, often with histidine and methionine axial ligands, which stabilizes the heme and modulates the potential by about 100-200 mV compared to bis-histidine coordination. In photosynthesis, cytochrome f in the b6f complex similarly facilitates electron transfer from photosystem II to plastocyanin. The efficiency of cytochrome-mediated transfer follows Marcus theory, which describes the rate constant for non-adiabatic electron tunneling as , where is the electronic coupling, the reorganization energy, and the driving force; in cytochromes, low values (around 0.5-1.0 eV) enable rates up to 10^6 s^{-1}.[11][49] Iron-sulfur proteins, including rubredoxins and ferredoxins, utilize Fe-S centers for electron transfer, particularly in anaerobic metabolism and photosynthetic electron flow. Rubredoxins feature a mononuclear iron atom tetrahedrally coordinated by four cysteine sulfurs, with redox potentials between -0.1 V and +0.05 V, enabling roles in bacterial respiration such as alkane hydroxylation in Pseudomonas oleovorans. Ferredoxins, containing [2Fe-2S], [3Fe-4S], or [4Fe-4S] clusters, exhibit lower potentials (-0.4 V to -0.3 V for plant-type [2Fe-2S]), facilitating electron delivery from photosystem I to NADP+ reductase in chloroplasts or in anaerobic pathways like nitrogen fixation. These clusters support delocalized electron transfer with reorganization energies of 0.6-0.8 eV, contributing to the ETC's complex I (NADH dehydrogenase) where multiple Fe-S centers bridge flavin to quinone.[11][11] Blue copper proteins, such as plastocyanins and azurins, employ type 1 copper sites for rapid electron transfer, characterized by a trigonal geometry with two histidines, a cysteine, and a weakly bound methionine. Plastocyanins, found in chloroplast thylakoids, shuttle electrons from cytochrome f to photosystem I with a redox potential of about +0.37 V, supporting photosynthetic charge separation. Azurins, in bacterial periplasm, perform analogous functions in denitrification with potentials around +0.30 V. The "entatic state" in these proteins enforces a strained Cu(II) geometry that resembles the reduced Cu(I) form, reducing reorganization energy to ~0.1-0.2 eV and accelerating self-exchange rates to 10^3-10^4 M^{-1} s^{-1}, far exceeding typical Cu^{2+/+} couples, as per Marcus theory predictions. This entatic control, induced by the protein scaffold, ensures minimal structural change during redox cycling, optimizing turnover in metabolic chains.[11]Metal Ion Storage and Transfer

Metalloproteins play a crucial role in the sequestration, storage, and controlled delivery of metal ions within biological systems, preventing toxicity from free ions while ensuring availability for essential processes. For iron homeostasis, ferritin serves as the primary intracellular storage protein, forming a spherical 24-subunit nanocage approximately 12 nm in diameter that encapsulates up to 4,500 Fe³⁺ ions in the form of a ferrihydrite mineral core, thereby maintaining iron in a non-toxic, bioavailable state.[50] In contrast, transferrin functions as the main serum transport protein, a bilobal glycoprotein that reversibly binds two Fe³⁺ ions per molecule in synergy with carbonate anions, facilitating safe circulation and delivery to cells via receptor-mediated endocytosis.[51] Copper management involves specialized proteins that handle its redox-active nature to avoid oxidative damage. Ceruloplasmin, a multidomain glycoprotein containing six to seven copper atoms, exhibits ferroxidase activity by oxidizing Fe²⁺ to Fe³⁺, which promotes iron loading into transferrin and accounts for about 95% of circulating copper transport in plasma.[52] Metallothioneins, small cysteine-rich proteins with up to 30 cysteine residues per subunit, bind Cu⁺ and Zn²⁺ ions through thiolate clusters, enabling intracellular storage, detoxification of excess metals, and regulation of their homeostasis across tissues.[53] For calcium, intracellular buffering is mediated by proteins like calbindin, which utilizes multiple EF-hand motifs—helical loops that coordinate Ca²⁺ with high affinity—to rapidly sequester ions and maintain cytosolic concentrations, thereby protecting against overload in neurons and other cells.[54] Similarly, parvalbumin, abundant in fast-twitch skeletal muscle fibers, employs EF-hand domains to bind Ca²⁺ transiently during contraction-relaxation cycles, accelerating relaxation by facilitating ion removal from troponin C.[55] Key mechanisms in metal ion handling distinguish apo-forms (metal-free proteins) from holo-forms (metal-bound), where metal insertion often stabilizes structure and enables function, as seen in the conformational shifts of ferritin and transferrin upon iron binding.[56] Dedicated chaperones ensure targeted delivery; for instance, the copper chaperone for superoxide dismutase (CCS), a dimeric protein with a dedicated copper-binding domain, specifically shuttles Cu⁺ to Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase (SOD1) via direct protein-protein interaction, inserting the ion into the enzyme's active site without releasing free copper.[57] Dysregulation of these systems underlies disorders such as hereditary hemochromatosis, where mutations in iron regulators like HFE lead to ferritin overload and excessive hepatic iron accumulation, causing tissue damage and fibrosis.[58] Likewise, Wilson's disease results from ATP7B mutations impairing copper export and ceruloplasmin maturation, leading to hepatic and neurological copper mishandling, with metallothioneins overwhelmed and free copper levels rising toxically.[59]Catalytic Functions

Hydrolase Enzymes

Hydrolase enzymes represent a key class of metalloproteins that catalyze the cleavage of chemical bonds through hydrolysis, often utilizing zinc ions to activate water molecules as nucleophiles. Carbonic anhydrase serves as a paradigmatic example, featuring a zinc(II) ion at its active site coordinated by three imidazole nitrogen atoms from histidine residues (His94, His96, and His119) in a tetrahedral geometry, which polarizes a bound water molecule to form a hydroxide nucleophile essential for catalysis.[60] This coordination enhances the enzyme's ability to interconvert carbon dioxide and bicarbonate, facilitating rapid physiological responses.[61] The catalytic mechanism of carbonic anhydrase involves the nucleophilic attack of the zinc-bound hydroxide on CO₂, forming a Zn-bound bicarbonate intermediate (Zn²⁺-HCO₃⁻) that dissociates to yield HCO₃⁻ and Zn²⁺-H₂O, followed by proton transfer (often via His64) to regenerate the active species. The process can be summarized as: This yields the overall reaction , with the enzyme achieving diffusion-limited kinetics at a turnover rate of approximately for the human α-isoform (hCA II).[62][63] Carbonic anhydrase exists in distinct isozyme classes: α-forms predominate in animals, β-forms in plants and some bacteria, and γ-forms primarily in bacteria, each adapted to specific cellular environments while sharing zinc-dependent catalysis.[64][65] Recent structural studies, including those from the 2020s, have revealed dynamic fluctuations in the zinc coordination sphere and active-site waters, underscoring how solvent dynamics contribute to product release and high efficiency.[60] Physiologically, carbonic anhydrase plays critical roles in pH regulation and CO₂ transport, enabling efficient gas exchange in tissues and blood by accelerating bicarbonate formation and buffering protons in erythrocytes and renal cells.[66][67] Inhibitors such as acetazolamide, which bind the zinc site and block hydroxide formation, are clinically used to reduce intraocular pressure in glaucoma treatment by decreasing aqueous humor production.[68] Beyond carbonic anhydrase, other zinc-dependent hydrolases include matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which feature a conserved zinc active site for hydrolyzing peptide bonds in extracellular matrix components like collagen, thereby driving tissue remodeling during development and wound healing.[69][70] Alkaline phosphatase, incorporating two zinc ions and one magnesium ion in its active site, catalyzes the hydrolysis of phosphate esters to release inorganic phosphate, supporting bone mineralization and nucleotide recycling.[71][72] These enzymes highlight the versatility of metal coordination in promoting nucleophilic water activation for diverse hydrolytic functions.Redox Enzymes

Redox enzymes are a class of metalloproteins that facilitate oxidation-reduction reactions essential for cellular metabolism, energy production, and defense against oxidative stress. These enzymes employ metal centers, such as copper, iron, and molybdenum, to mediate electron transfer, enabling the catalysis of reactions involving reactive oxygen species (ROS) and other substrates. By cycling between oxidation states, these metal ions lower activation energies and achieve high catalytic efficiencies, often approaching diffusion-limited rates.[73] A prominent example is superoxide dismutase (SOD), particularly the copper-zinc form (Cu/Zn-SOD), which catalyzes the dismutation of superoxide radicals (O₂⁻•) into hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) and molecular oxygen (O₂). The reaction proceeds via a redox cycle at the copper center, where Cu²⁺ is reduced to Cu⁺ by the first superoxide anion, followed by reoxidation of Cu⁺ by a second superoxide, with the zinc ion stabilizing the active site structure. This mechanism operates at a near-diffusion-controlled rate constant of approximately 10⁹ M⁻¹ s⁻¹, ensuring rapid detoxification of superoxide in aerobic organisms. The overall reaction is: Cu/Zn-SOD is ubiquitously expressed in eukaryotic cells, contributing to the first line of antioxidant defense by preventing superoxide accumulation, which can otherwise lead to damaging chain reactions.[74][75][76] Cytochrome P450 enzymes represent another key family of redox metalloproteins, utilizing a heme iron center to perform monooxygenation of substrates such as hydrocarbons, steroids, and xenobiotics. In this process, the iron cycles through Fe²⁺, Fe³⁺, and high-valent Fe(IV)=O states, activated by NADPH-derived electrons and molecular oxygen, to insert one oxygen atom into the substrate (RH) while reducing the other to water. The catalytic cycle involves hydrogen atom abstraction from the substrate by the Fe(IV)=O species, forming a substrate radical that rebounds to the iron-oxo complex, yielding the hydroxylated product (ROH). The simplified stoichiometry is: This radical rebound mechanism enables the diverse metabolic functions of P450s, including drug detoxification and biosynthesis of hormones, with over 50 human isoforms exhibiting substrate specificity.[73][77] Other notable redox enzymes include catalase, which employs a heme iron center to decompose hydrogen peroxide, and xanthine oxidase, featuring a molybdenum cofactor for purine oxidation. Catalase catalyzes the breakdown of H₂O₂ via a two-stage ping-pong mechanism: the first H₂O₂ oxidizes the Fe³⁺ heme to a Fe⁴⁺=O porphyrin cation radical (Compound I), which then reacts with a second H₂O₂ to regenerate the resting state while producing water and oxygen. The reaction is: This high-turnover process (up to 10⁷ s⁻¹) protects cells from H₂O₂-mediated damage in peroxisomes and mitochondria. In contrast, xanthine oxidase oxidizes hypoxanthine to xanthine and xanthine to uric acid at the molybdenum center, involving nucleophilic attack by a substrate enolate on an oxidized Mo(VI) followed by electron transfer to FAD and iron-sulfur clusters, generating superoxide as a byproduct. These enzymes collectively manage ROS levels, with SOD and catalase forming a coordinated antioxidant network that mitigates oxidative stress in biological systems.[78][79][76]Nitrogen-Fixing Enzymes

Nitrogenase is the primary metalloprotein complex responsible for biological nitrogen fixation, catalyzing the reduction of atmospheric dinitrogen (N₂) to ammonia (NH₃) in prokaryotes. This enzyme system consists of two main components: the Fe protein, a homodimer containing a single [4Fe-4S] cluster that serves as the electron donor, and the MoFe protein, an α₂β₂ heterotetramer housing two types of metalloclusters per αβ dimer—the P-cluster ([8Fe-7S]) for transient electron storage and transfer, and the iron-molybdenum cofactor (FeMoco), the site of N₂ reduction.[80] The FeMoco is a complex [MoFe₇S₉C] cluster featuring a central carbide (C⁴⁻) and coordinated by homocitrate, which stabilizes the structure and facilitates substrate binding within the α-subunit.[81] The catalytic mechanism follows the Lowe-Thorneley kinetic scheme, involving eight successive electron/proton transfers (E₀ to E₈ states) powered by the hydrolysis of 16 ATP molecules per N₂ reduced. The overall reaction is N₂ + 8 H⁺ + 8 e⁻ + 16 MgATP → 2 NH₃ + H₂ + 16 MgADP + 16 Pᵢ, with obligatory H₂ production arising from reductive elimination of accumulated hydrides at the FeMoco.[82] N₂ binds after four reducing equivalents accumulate as two [Fe–H–Fe] bridges (Janus intermediate, E₄), triggering H₂ release and initiating stepwise reduction via the alternating (A) pathway, which proceeds through diazene (N₂H₂) and hydrazine (N₂H₄) intermediates before N–N bond cleavage and release of two NH₃ molecules.[82] Alternative nitrogenase variants exist in certain bacteria, adapting to molybdenum scarcity: V-nitrogenase replaces FeMoco with an iron-vanadium cofactor (FeVco, [VFe₇S₉C-homocitrate]) in the VFe protein (α₂β₂δ₂ heterooctamer) paired with a homologous Fe protein, exhibiting lower N₂ reduction efficiency but broader substrate range; Fe-only nitrogenase uses an all-iron cofactor (FeFeco) in place of Mo or V, found in organisms like Azotobacter vinelandii under metal limitation, and operates via a similar reductive elimination mechanism but with even higher H₂ output and reduced activity.[83][84] In biological systems, nitrogenase functions in both free-living diazotrophs, such as Azotobacter species in aerobic soils, where it contributes modest fixed nitrogen yields (up to 20 kg N ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹), and symbiotic associations, notably Rhizobium bacteria in root nodules of legumes like soybeans, enabling high-efficiency fixation (up to 600 kg N ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹) by leveraging plant-derived carbohydrates.[85] The process demands substantial energy, equivalent to 16 ATP per N₂ molecule, often accounting for 20-25% of the host plant's photosynthate in symbiotic systems.[85][86] A major challenge is nitrogenase's extreme sensitivity to oxygen, which irreversibly inactivates the Fe protein and FeMoco through oxidative damage, necessitating anaerobic microenvironments in free-living bacteria via rapid respiration or in symbioses through legume nodule barriers and leghemoglobin protection.[87] Recent advances in the 2020s include synthetic FeMoco mimics, such as trigonal prismatic [Fe₆C] clusters capped by Mo or W, which replicate key structural motifs and enable electrocatalytic N₂ reduction, paving the way for bio-inspired ammonia production.[81] Ongoing efforts integrate these mimics into protein scaffolds for enhanced stability and activity under ambient conditions.[88]Photosynthetic Proteins

Photosynthetic proteins are metalloproteins that integrate light absorption, energy transfer, and electron transport in the process of photosynthesis, primarily utilizing magnesium in chlorophylls and transition metals like manganese, iron, and copper for catalytic and redox functions. These proteins enable the conversion of solar energy into chemical energy, with key components including light-harvesting complexes and reaction centers that coordinate metal centers to achieve high efficiency. In oxygenic photosynthesis, as found in plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, these metalloproteins facilitate the light-dependent reactions, where water is split to produce oxygen and reducing equivalents. Central to this process are the chlorophyll proteins in photosystems I and II (PSI and PSII), where magnesium-porphyrin complexes serve as the primary light-absorbing pigments. In PSII, the reaction center P680, a special pair of chlorophyll a molecules coordinated by magnesium, absorbs light at approximately 680 nm and initiates charge separation, driving electron transfer to the acceptor pheophytin. Coupled to this is the oxygen-evolving complex (OEC), a Mn4CaO5 cluster that catalyzes water oxidation via the Kok cycle, accumulating four oxidizing equivalents to produce dioxygen:The manganese ions in the OEC adopt distorted octahedral coordination, enabling sequential redox changes from Mn(III) to Mn(IV) states during the S0 to S4 transitions. Structural studies have revealed the cubane-like arrangement of three Mn and one Ca ions bridged by oxo ligands, with the fourth Mn loosely bound, facilitating substrate binding and O-O bond formation. This cluster's efficiency stems from its ability to couple proton-coupled electron transfer, minimizing energy loss. The cytochrome b6f complex links PSII to PSI in the photosynthetic electron transport chain, employing iron-sulfur clusters and heme groups for proton translocation. The Rieske Fe-S center, a [2Fe-2S] cluster with one histidine-ligated iron, accepts electrons from plastocyanin or cytochrome c6 and transfers them to the high-potential heme bH via the Rieske protein's conformational mobility. This complex operates via a modified Q-cycle, where plastoquinol oxidation at the Qo site bifurcates electrons: one to the Rieske center and the other across the membrane to heme bL, then bH, reducing plastoquinone at the Qi site while translocating protons. The hemes bL and bH, along with the c1 heme, coordinate iron in bis-histidine ligation, ensuring vectorial electron flow and contributing to the proton motive force. Light-harvesting complexes, such as LHCII, the major antenna in plants, bind multiple Mg-chlorophyll a and b molecules to capture a broad spectrum of light and funnel excitation energy to the reaction centers. LHCII, a trimeric protein rich in chlorophylls coordinated by axial ligands from histidine and water, achieves efficient energy transfer through Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET), where dipole-dipole interactions between pigments enable near-unity quantum efficiency over distances of 1-10 nm. Recent spectroscopic studies using two-dimensional electronic spectroscopy have refined models of this process, revealing coherent exciton delocalization and vibrational assistance that enhance transfer rates beyond classical Förster predictions, with quantum efficiencies approaching 95% under optimal conditions. The metalloprotein architecture of photosynthetic proteins traces its evolutionary origins to anoxygenic bacterial systems, such as those in purple bacteria, where type II reaction centers with Fe-S clusters preceded the emergence of oxygenic photosynthesis around 2.7-3 billion years ago in ancient cyanobacteria. This transition involved gene duplication and fusion events that integrated the Mn4Ca cluster into a PSI-like ancestor, enabling water as an electron donor and transforming Earth's atmosphere. Advances in 2020s spectroscopy, including time-resolved femtosecond techniques, have updated quantum efficiency models by quantifying vibronic couplings and environmental decoherence, showing how protein scaffolds tune metal-pigment interactions for robust energy conversion even under fluctuating light conditions.