Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

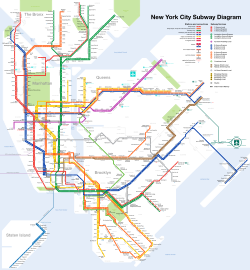

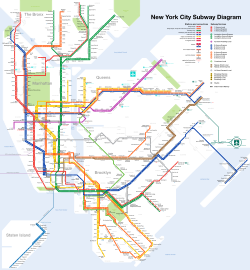

Transit map

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2014) |

A transit map is a topological map in the form of a schematic diagram used to illustrate the routes and stations within a public transport system—whether this be bus, tram, rapid transit, commuter rail or ferry routes.[1] Metro maps, subway maps, or tube maps of metropolitan railways are some common examples.[2][3]

The primary function of a transit map is facilitating the passengers' orientation and navigation, helping them to efficiently use the public transport system and identify which stations function as interchange between lines.[2]

Transit maps can usually be found in the transit vehicles, at the platforms or in printed timetables. They are also accessible through digital platforms like mobile apps and websites, ensuring widespread availability and convenience for passengers.[4][5]

History

[edit]The mapping of transit systems was at first generally geographically accurate, but abstract route-maps of individual lines (usually displayed inside the carriages) can be traced back as early as 1908 (London's District line), and certainly there are examples from European and American railroad cartography as early as the 1890s where geographical features have been removed and the routes of lines have been artificially straightened out. But it was George Dow of the London and North Eastern Railway who was the first to launch a diagrammatic representation of an entire rail transport network (in 1929); his work is seen by historians of the subject as being part of the inspiration for Harry Beck when he launched his iconic London Underground map in 1933.

After this pioneering work, many transit authorities worldwide imitated the diagrammatic look for their own networks, some while continuing to also publish hybrid versions that were geographically accurate.

Early maps of the Berlin U-Bahn, Berlin S-Bahn, Boston T, Paris Métro, and New York City Subway also exhibited some elements of the diagrammatic form.[6][7][8][9]

The 2007 edition of the Madrid Metro map, designed by the RaRo Agency, took the idea of a simple diagram one step further by becoming one of the first produced for a major network to remove diagonal lines altogether; it is constituted just by horizontal and vertical lines only at right angles to each other.[10] After many complaints over its disadvantages, the company reverted to the previous map in 2013.[11]

Transit maps are now increasingly digitized and can be shown in many forms online.[5]

Elements

[edit]

Transit maps use symbols and abstract representation of the location's geography to illustrate the lines, stations and transfer points of the system while still serving as a tool of physical navigation in the city.

Stations are marked with symbols that break the line's continuity, along with their names, so they may be referred to on other maps or travel itineraries. Further help may be granted through the inclusion of important tourist attractions and other locations such as the city center; these may be identified through symbols or wording.

Color coding allows the map to specify each route in an easy way, allowing the users to quickly identify where each specific route goes; if it does not go to the desired destination, the colors and symbols allow the user to identify a feasible point of transfer between lines.

Symbols such as aircraft may be used to illustrate airports, and symbols of trains may be used to identify stations that allow transfer to other modes, such as commuter or intercity train services.

Use by transit systems

[edit]Many transit authorities publish multiple maps of their systems; this can be done by isolating one mode of transport, for instance only rapid transit or only bus, onto a single map, or instead the authorities publish maps covering only a limited area, but with greater detail. Another modification is to produce geographically accurate maps of the system, to allow users to better understand the routes. Even if official geographical accurate maps are not available, these can often be obtained from unofficial sources since the information is available from other sources.

With the widespread use of zone pricing[citation needed] for fare calculation, systems that span more than one zone need a system to inform the use which zone a particular station is located in. Common ways include varying the tone of the background color, or by running a weak line along the zone boundaries.

Iconic status

[edit]There are a growing number of books, websites and works of art on the subject of urban rail and metro map design and use. There are now hundreds of examples of diagrams in an urban rail or metro map style that are used to represent everything from other transit networks like buses and national rail services to sewerage systems and Derbyshire public houses.

One of the most well-known adaptations of an urban rail map was The Great Bear, a lithograph by Simon Patterson. First shown in 1992 and nominated for the Turner Prize, The Great Bear replaces station names on the London Underground map with those of explorers, saints, film stars, philosophers and comedians. Other artists such as Scott Rosenbaum, and Ralph Gray have also taken the iconic style of the urban rail map and made new artistic creations ranging from the abstract to the Solar System. Following the success of these the idea of adapting other urban rail and metro maps has spread so that now almost every major subway or rapid transit system with a map has been doctored with different names, often anagrams of the original station name.

Some maps including those for the rapid transit systems of New York City, Washington D.C., Boston, Montreal, Denver, London have been recreated to include the names of local pubs.[12][13]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The current subway map is at https://new.mta.info/map/5256.

References

[edit]- ^ Hanniel, Iddo; Shai, Hirsch. "Topological Maps". doc.cgal.org. Archived from the original on June 1, 2023. Retrieved March 8, 2025.

- ^ a b Guo, Zhan (April 16, 2011). "Mind the map! The impact of transit maps on path choice in public transit". Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice. 45 (7): 625–639. Bibcode:2011TRPA...45..625G. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2011.04.001. Archived from the original on October 12, 2022 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

A transit map is a schematic diagram that depicts the locations, directions, and connections of stations and lines in a public transit system.

- ^ Prabhakar, Archana; Grison, Elise; Morgagni, Simone; Lhuillier, Simon (April 21, 2022). "Transit maps: do they shape our minds?" (PDF). 3rd Schematic Mapping Workshop. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 17, 2025 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Tyler, Richard (February 12, 2025). "Blind inventor leads the way in the US capital". www.thetimes.com. Archived from the original on March 8, 2025. Retrieved March 8, 2025.

- ^ a b Matters, Transport for London | Every Journey. "Tube". Transport for London. Archived from the original on March 4, 2025. Retrieved March 8, 2025.

- ^ "Transit Maps: Historical Maps: Berlin S- and U-Bahn Maps, 1910-1936". Transit Maps. April 25, 2012. Archived from the original on January 4, 2024. Retrieved June 2, 2025.

- ^ "Old Maps of Boston Transit". Flickr. Archived from the original on March 8, 2025. Retrieved March 8, 2025.

- ^ "Transit Maps: Historical Map: Paris Métro, 1913". Transit Maps. September 14, 2012. Archived from the original on December 7, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2025.

- ^ Stewart, Jules (July 5, 2023). "Untangling the New York City subway". Geographical. Archived from the original on March 6, 2025. Retrieved March 8, 2025.

- ^ "Transit Maps: Official Map: Metro de Madrid, Spain, 2012". Transit Maps. March 27, 2012. Archived from the original on March 8, 2025. Retrieved March 8, 2025.

- ^ Álvarez, Pilar (May 31, 2013). "Metro recupera el plano geográfico". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- ^ "Pubway Maps". Unquestionable Taste. Archived from the original on January 13, 2015. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

- ^ "Tube Map Shows The Cheapest Pint Near Every Tube Station". Londonist. July 17, 2019.

Further reading

[edit]- Mr Beck's Underground Map, Ken Garland, Capital Transport, London, 1994. ISBN 1-85414-168-6

- No Need To Ask, David Leboff and Tim Demuth, Capital Transport, London, 1999. ISBN 1-85414-215-1

- Metro Maps of the World, Mark Ovenden, Capital Transport, London, 2003. ISBN 1-85414-288-7

- Das Berliner U- und S-Bahnnetz, Alfred B. Gottwaldt, TransPress, Stuttgart, 2004. ISBN 3-613-71227-X

- Telling the passenger where to get off, Andrew Dow, Capital Transport, London, 2005. ISBN 1-85414-291-7

- Underground Maps After Beck, Maxwell J. Roberts, Capital Transport, London, 2005. ISBN 1-85414-286-0

- Transit Maps of the world, Mark Ovenden, Penguin books, New York, 2007. ISBN 978-0-14-311265-5

External links

[edit]- Subways Transport, an extensive site with archive maps on virtually every urban rail system in the world.

- Urban Rail