Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

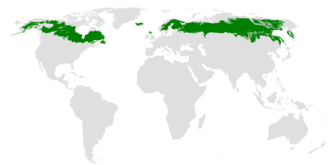

Taiga

View on Wikipedia

| Taiga | |

|---|---|

| |

The taiga is found throughout the high northern latitudes, between the tundra and the temperate forest, from about 50°N to 70°N, but with considerable regional variation. | |

| Ecology | |

| Biome |

|

| Geography | |

| Countries |

|

| Climate type |

|

Taiga or tayga (/ˈtaɪɡə/ TY-gə; Russian: тайга́, IPA: [tɐjˈɡa]), also known as boreal forest or snow forest, is a biome characterized by coniferous forests consisting mostly of pines, spruces, and larches. The taiga, or boreal forest, is the world's largest land biome.[1] In North America, it covers most of inland Canada, Alaska, and parts of the northern contiguous United States.[2] In Eurasia, it covers most of Sweden, Finland, much of Russia from Karelia in the west to the Pacific Ocean (including much of Siberia), much of Norway and Estonia, some of the Scottish Highlands,[citation needed] some lowland/coastal areas of Iceland, and areas of northern Kazakhstan, northern Mongolia, and northern Japan (on the island of Hokkaido).[3]

The principal tree species, depending on the length of the growing season and summer temperatures, vary across the world. The taiga of North America is mostly spruce; Scandinavian and Finnish taiga consists of a mix of spruce, pines and birch; Russian taiga has spruces, pines and larches depending on the region; and the Eastern Siberian taiga is a vast larch forest.[3]

Taiga in its current form is a relatively recent phenomenon, having only existed for the last 12,000 years since the beginning of the Holocene epoch, covering land that had been mammoth steppe or under the Scandinavian Ice Sheet in Eurasia and under the Laurentide Ice Sheet in North America during the Late Pleistocene.

Although at high elevations taiga grades into alpine tundra through Krummholz, it is not exclusively an alpine biome, and unlike subalpine forest, much of taiga is lowlands.

The term "taiga" is not used consistently by all cultures. In the English language, "boreal forest" is used in the United States and Canada in referring to more southerly regions, while "taiga" is used to describe the more northern, barren areas approaching the tree line and the tundra. Hoffman (1958) discusses the origin of this differential use in North America and how this differentiation distorts established Russian usage.[4]

Climate change is a threat to taiga,[5] and how the carbon dioxide absorbed or emitted[6] should be treated by carbon accounting is controversial.[7]

Climate and geography

[edit]

Taiga covers 17 million square kilometres (6.6 million square miles) or 11.5% of the Earth's land area,[8] second only to deserts and xeric shrublands.[1] The largest areas are located in Russia and Canada. In Sweden taiga is associated with the Norrland terrain.[9]

Temperature

[edit]After the permanent ice caps and tundra, taiga is the terrestrial biome with the lowest annual average temperatures, with mean annual temperature generally varying from −5 to 5 °C (23 to 41 °F).[10] Extreme winter minimums in the northern taiga are typically lower than those of the tundra. There are taiga areas of eastern Siberia and interior Alaska-Yukon where the mean annual temperature reaches down to −10 °C (14 °F),[11][12] and the lowest reliably recorded temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere were recorded in the taiga of northeastern Russia.

Taiga has a subarctic climate with very large temperature range between seasons. −20 °C (−4 °F) would be a typical winter day temperature and 18 °C (64 °F) an average summer day, but the long, cold winter is the dominant feature. This climate is classified as Dfc, Dwc, Dsc, Dfd and Dwd in the Köppen climate classification scheme,[13] meaning that the short summers (24 h average 10 °C (50 °F) or more), although generally warm and humid, only last 1–3 months, while winters, with average temperatures below freezing, last 5–7 months.

In Siberian taiga the average temperature of the coldest month is between −6 °C (21 °F) and −50 °C (−58 °F).[14] There are also some much smaller areas grading towards the oceanic Cfc climate with milder winters, whilst the extreme south and (in Eurasia) west of the taiga reaches into humid continental climates (Dfb, Dwb) with longer summers.

According to some sources, the boreal forest grades into a temperate mixed forest when mean annual temperature reaches about 3 °C (37 °F).[15] Discontinuous permafrost is found in areas with mean annual temperature below freezing, whilst in the Dfd and Dwd climate zones continuous permafrost occurs and restricts growth to very shallow-rooted trees like Siberian larch.

Growing season

[edit]

The growing season, when the vegetation in the taiga comes alive, is usually slightly longer than the climatic definition of summer as the plants of the boreal biome have a lower temperature threshold to trigger growth than other plants. Some sources claim 130 days growing season as typical for the taiga.[1]

In Canada and Scandinavia, the growing season is often estimated by using the period of the year when the 24-hour average temperature is +5 °C (41 °F) or more.[16] For the Taiga Plains in Canada, growing season varies from 80 to 150 days, and in the Taiga Shield from 100 to 140 days.[17]

Other sources define growing season by frost-free days.[18] Data for locations in southwest Yukon gives 80–120 frost-free days.[19] The closed canopy boreal forest in Kenozersky National Park near Plesetsk, Arkhangelsk Province, Russia, on average has 108 frost-free days.[20]

The longest growing season is found in the smaller areas with oceanic influences; in coastal areas of Scandinavia and Finland, the growing season of the closed boreal forest can be 145–180 days.[21] The shortest growing season is found at the northern taiga–tundra ecotone, where the northern taiga forest no longer can grow and the tundra dominates the landscape when the growing season is down to 50–70 days,[22][23] and the 24-hr average of the warmest month of the year usually is 10 °C (50 °F) or less.[24]

High latitudes mean that the sun does not rise far above the horizon, and less solar energy is received than further south. But the high latitude also ensures very long summer days, as the sun stays above the horizon nearly 20 hours each day, or up to 24 hours, with only around 6 hours of daylight, or none, occurring in the dark winters, depending on latitude. The areas of the taiga inside the Arctic Circle have midnight sun in mid-summer and polar night in mid-winter.

Precipitation

[edit]The taiga experiences relatively low precipitation throughout the year (generally 200–750 mm (7.9–29.5 in) annually, 1,000 mm (39 in) in some areas), primarily as rain during the summer months, but also as snow or fog. Snow may remain on the ground for as long as nine months in the northernmost extensions of the taiga biome.[25]

The fog, especially predominant in low-lying areas during and after the thawing of frozen Arctic seas, stops sunshine from getting through to plants even during the long summer days. As evaporation is consequently low for most of the year, annual precipitation exceeds evaporation, and is sufficient to sustain the dense vegetation growth including large trees. This explains the striking difference in biomass per square metre between the Taiga and the Steppe biomes, (in warmer climates), where evapotranspiration exceeds precipitation, restricting vegetation to mostly grasses.

In general, taiga grows to the south of the 10 °C (50 °F) July isotherm, occasionally as far north as the 9 °C (48 °F) July isotherm,[26] with the southern limit more variable. Depending on rainfall, and taiga may be replaced by forest steppe south of the 15 °C (59 °F) July isotherm where rainfall is very low, but more typically extends south to the 18 °C (64 °F) July isotherm, and locally where rainfall is higher, such as in eastern Siberia and adjacent Outer Manchuria, south to the 20 °C (68 °F) July isotherm.

In these warmer areas the taiga has higher species diversity, with more warmth-loving species such as Korean pine, Jezo spruce, and Manchurian fir, and merges gradually into mixed temperate forest or, more locally (on the Pacific Ocean coasts of North America and Asia), into coniferous temperate rainforests where oak and hornbeam appear and join the conifers, birch and Populus tremula.

Glaciation

[edit]The area currently classified as taiga in Europe and North America (except Alaska) was recently glaciated. As the glaciers receded they left depressions in the topography that have since filled with water, creating lakes and bogs (especially muskeg soil) found throughout the taiga.

-

The taiga in the river valley near Verkhoyansk, Russia, at 67°N, experiences the coldest winter temperatures in the northern hemisphere, but the extreme continentality of the climate gives an average daily high of 22 °C (72 °F) in July

-

Lakes and other water bodies are common in the taiga. The Helvetinjärvi National Park, Finland, is situated in the closed canopy taiga (mid-boreal to south-boreal)[27] with mean annual temperature of 4 °C (39 °F).[28]

Soils

[edit]

Taiga soil tends to be young and poor in nutrients, lacking the deep, organically enriched profile present in temperate deciduous forests.[29] The colder climate hinders development of soil, and the ease with which plants can use its nutrients.[29] The relative lack of deciduous trees, which drop huge volumes of leaves annually, and grazing animals, which contribute significant manure, are also factors. The diversity of soil organisms in the boreal forest is high, comparable to the tropical rainforest.[30]

Fallen leaves and moss can remain on the forest floor for a long time in the cool, moist climate, which limits their organic contribution to the soil. Acids from evergreen needles further leach the soil, creating spodosol, also known as podzol,[31] and the acidic forest floor often has only lichens and some mosses growing on it. In clearings in the forest and in areas with more boreal deciduous trees, there are more herbs and berries growing, and soils are consequently deeper.

Flora

[edit]

Since North America and Eurasia were originally connected by the Bering land bridge, a number of animal and plant species, more animals than plants, were able to colonize both land masses, and are globally-distributed throughout the taiga biome (see Circumboreal Region). Others differ regionally, typically with each genus having several distinct species, each occupying different regions of the taiga. Taigas also have some small-leaved deciduous trees, like birch, alder, willow, and poplar. These grow mostly in areas further south of the most extreme winter weather.

The Dahurian larch tolerates the coldest winters of the Northern Hemisphere, in eastern Siberia. The very southernmost parts of the taiga may have trees such as oak, maple, elm and lime scattered among the conifers, and there is usually a gradual transition into a temperate, mixed forest, such as the eastern forest-boreal transition of eastern Canada. In the interior of the continents, with the driest climates, the boreal forests might grade into temperate grassland.

There are two major types of taiga. The southern part is the closed canopy forest, consisting of many closely-spaced trees and mossy groundcover. In clearings in the forest, shrubs and wildflowers are common, such as the fireweed and lupine. The other type is the lichen woodland or sparse taiga, with trees that are farther-spaced and lichen groundcover; the latter is common in the northernmost taiga.[32] In the northernmost taiga, the forest cover is not only more sparse, but often stunted in growth form; moreover, ice-pruned, asymmetric black spruce (in North America) are often seen, with diminished foliage on the windward side.[33]

In Canada, Scandinavia and Finland, the boreal forest is usually divided into three subzones: The high boreal (northern boreal/taiga zone), the middle boreal (closed forest), and the southern boreal, a closed-canopy, boreal forest with some scattered temperate, deciduous trees among the conifers.[34] Commonly seen are species such as maple, elm and oak. This southern boreal forest experiences the longest and warmest growing season of the biome. In some regions, including Scandinavia and western Russia, this subzone is commonly used for agricultural purposes.

The boreal forest is home to many types of berries. Some species are confined to the southern and middle closed-boreal forest (such as wild strawberry and partridgeberry); others grow in most areas of the taiga (such as cranberry and cloudberry). Some berries can grow in both the taiga and the lower arctic (southern regions) tundra, such as bilberry, bunchberry and lingonberry.

The forests of the taiga are largely coniferous, dominated by larch, spruce, fir and pine. The woodland mix varies according to geography and climate; for example, the Eastern Canadian forests ecoregion (of the higher elevations of the Laurentian Mountains and the northern Appalachian Mountains) in Canada is dominated by balsam fir Abies balsamea, while further north, the Eastern Canadian Shield taiga (of northern Quebec and Labrador) is mostly black spruce Picea mariana and tamarack larch Larix laricina.

Evergreen species in the taiga (spruce, fir, and pine) have a number of adaptations specifically for survival in harsh taiga winters, although larch, which is extremely cold-tolerant,[35] is deciduous. Taiga trees tend to have shallow roots to take advantage of the thin soils, while many of them seasonally alter their biochemistry to make them more resistant to freezing, called "hardening".[36] The narrow conical shape of northern conifers, and their downward-drooping limbs, also help them shed snow.[36]

Because the sun is low in the horizon for most of the year, it is difficult for plants to generate energy from photosynthesis. Pine, spruce and fir do not lose their leaves seasonally and are able to photosynthesize with their older leaves in late winter and spring when light is good but temperatures are still too low for new growth to commence. The adaptation of evergreen needles limits the water lost due to transpiration and their dark green color increases their absorption of sunlight. Although precipitation is not a limiting factor, the ground freezes during the winter months and plant roots are unable to absorb water, so desiccation can be a severe problem in late winter for evergreens.

Although the taiga is dominated by coniferous forests, some broadleaf trees also occur, including birch, aspen, willow, and rowan. Many smaller herbaceous plants, such as ferns and occasionally ramps grow closer to the ground. Periodic stand-replacing wildfires (with return times of between 20 and 200 years) clear out the tree canopies, allowing sunlight to invigorate new growth on the forest floor. For some species, wildfires are a necessary part of the life cycle in the taiga; some, e.g. jack pine have cones which only open to release their seed after a fire, dispersing their seeds onto the newly cleared ground; certain species of fungi (such as morels) are also known to do this. Grasses grow wherever they can find a patch of sun; mosses and lichens thrive on the damp ground and on the sides of tree trunks. In comparison with other biomes, however, the taiga has low botanical diversity.

Coniferous trees are the dominant plants of the taiga biome. Very few species, in four main genera, are found: the evergreen spruce, fir and pine, and the deciduous larch. In North America, one or two species of fir, and one or two species of spruce, are dominant. Across Scandinavia and western Russia, the Scots pine is a common component of the taiga, while taiga of the Russian Far East and Mongolia is dominated by larch. Rich in spruce and Scots pine (in the western Siberian plain), the taiga is dominated by larch in Eastern Siberia, before returning to its original floristic richness on the Pacific shores. Two deciduous trees mingle throughout southern Siberia: birch and Populus tremula.[14]

-

Conifer cones and morels after fire in a boreal forest.

-

Moss (Ptilium crista-castrensis) cover on the floor of taiga

Fauna

[edit]

The boreal forest/taiga supports a relatively small variety of highly specialized and adapted animals, due to the harshness of the climate. Canada's boreal forest includes 85 species of mammals, 130 species of fish, and an estimated 32,000 species of insects.[37] Insects play a critical role as pollinators, decomposers, and as a part of the food web. Many nesting birds, rodents, and small carnivorous mammals rely on them for food in the summer months.

The cold winters and short summers make the taiga a challenging biome for reptiles and amphibians, which depend on environmental conditions to regulate their body temperatures. There are only a few species in the boreal forest, including red-sided garter snake, common European adder, blue-spotted salamander, northern two-lined salamander, Siberian salamander, wood frog, northern leopard frog, boreal chorus frog, American toad, and Canadian toad. Most hibernate underground in winter.

Fish of the taiga must be able to withstand cold water conditions and be able to adapt to life under ice-covered water. Species in the taiga include Alaska blackfish, northern pike, walleye, longnose sucker, white sucker, various species of cisco, lake whitefish, round whitefish, pygmy whitefish, Arctic lamprey, various grayling species, brook trout (including sea-run brook trout in the Hudson Bay area), chum salmon, Siberian taimen, lenok and lake chub.

The taiga is mainly home to a number of large herbivorous mammals, such as Alces alces (moose), and a few subspecies of Rangifer tarandus (reindeer in Eurasia; caribou in North America). Some areas of the more southern closed boreal forest have populations of other Cervidae species, such as the maral, elk, Sitka black-tailed deer, and roe deer. While normally a polar species, some southern herds of muskoxen reside in the taiga of Russia's Far East and North America. The Amur-Kamchatka region of far eastern Russia also supports the snow sheep, the Russian relative of the American bighorn sheep, wild boar, and long-tailed goral.[38][39] The largest animal in the taiga is the wood bison of northern Canada/Alaska; additionally, some numbers of the American plains bison have been introduced into the Russian far-east, as part of the taiga regeneration project called Pleistocene Park, in addition to Przewalski's horse.[40]

Small mammals of the taiga biome include rodent species such as the beaver, squirrel, chipmunk, marmot, lemming, North American porcupine and vole, as well as a small number of lagomorph species, such as the pika, snowshoe hare and mountain hare. These species have adapted to survive the harsh winters in their native ranges. Some larger mammals, such as bears, eat heartily during the summer in order to gain weight, and then go into hibernation during the winter. Other animals have adapted layers of fur or feathers to insulate them from the cold.

Predatory mammals of the taiga must be adapted to travel long distances in search of scattered prey, or be able to supplement their diet with vegetation or other forms of food (such as raccoons). Mammalian predators of the taiga include Canada lynx, Eurasian lynx, stoat, Siberian weasel, least weasel, sable, American marten, North American river otter, European otter, American mink, wolverine, Asian badger, fisher, timber wolf, Mongolian wolf, coyote, red fox, Arctic fox, grizzly bear, American black bear, Asiatic black bear, Ussuri brown bear, polar bear (only small areas of northern taiga), Siberian tiger, and Amur leopard.

More than 300 species of birds have their nesting grounds in the taiga.[41] Siberian thrush, white-throated sparrow, and black-throated green warbler migrate to this habitat to take advantage of the long summer days and abundance of insects found around the numerous bogs and lakes. Of the 300 species of birds that summer in the taiga, only 30 stay for the winter.[42] These are either carrion-feeding or large raptors that can take live mammal prey, such as the golden eagle, rough-legged buzzard (also known as the rough-legged hawk), Steller's sea eagle (in coastal northeastern Russia-Japan), great gray owl, snowy owl, barred owl, great horned owl, crow and raven. The only other viable adaptation is seed-eating birds, which include several species of grouse, capercaillie and crossbills.

Fire

[edit]

Fire has been one of the most important factors shaping the composition and development of boreal forest stands;[43] it is the dominant stand-renewing disturbance through much of the Canadian boreal forest.[44] The fire history that characterizes an ecosystem is its fire regime, which has 3 elements: (1) fire type and intensity (e.g., crown fires, severe surface fires, and light surface fires), (2) size of typical fires of significance, and (3) frequency or return intervals for specific land units.[45] The average time within a fire regime to burn an area equivalent to the total area of an ecosystem is its fire rotation (Heinselman 1973)[46] or fire cycle (Van Wagner 1978).[47] However, as Heinselman (1981) noted,[45] each physiographic site tends to have its own return interval, so that some areas are skipped for long periods, while others might burn two-times or more often during a nominal fire rotation.

The dominant fire regime in the boreal forest is high-intensity crown fires or severe surface fires of very large size, often more than 10,000 ha (100 km2), and sometimes more than 400,000 ha (4000 km2).[45] Such fires kill entire stands. Fire rotations in the drier regions of western Canada and Alaska average 50–100 years, shorter than in the moister climates of eastern Canada, where they may average 200 years or more. Fire cycles also tend to be long near the tree line in the subarctic spruce-lichen woodlands. The longest cycles, possibly 300 years, probably occur in the western boreal in floodplain white spruce.[45]

Amiro et al. (2001) calculated the mean fire cycle for the period 1980 to 1999 in the Canadian boreal forest (including taiga) at 126 years.[44] Increased fire activity has been predicted for western Canada, but parts of eastern Canada may experience less fire in future because of greater precipitation in a warmer climate.[48]

The mature boreal forest pattern in the south shows balsam fir dominant on well-drained sites in eastern Canada changing centrally and westward to a prominence of white spruce, with black spruce and tamarack forming the forests on peats, and with jack pine usually present on dry sites except in the extreme east, where it is absent.[49] The effects of fires are inextricably woven into the patterns of vegetation on the landscape, which in the east favour black spruce, paper birch, and jack pine over balsam fir, and in the west give the advantage to aspen, jack pine, black spruce, and birch over white spruce. Many investigators have reported the ubiquity of charcoal under the forest floor and in the upper soil profile.[50] Charcoal in soils provided Bryson et al. (1965) with clues about the forest history of an area 280 km north of the then-current tree line at Ennadai Lake, District Keewatin, Northwest Territories.[51]

Two lines of evidence support the thesis that fire has always been an integral factor in the boreal forest: (1) direct, eye-witness accounts and forest-fire statistics, and (2) indirect, circumstantial evidence based on the effects of fire, as well as on persisting indicators.[49] The patchwork mosaic of forest stands in the boreal forest, typically with abrupt, irregular boundaries circumscribing homogenous stands, is indirect but compelling testimony to the role of fire in shaping the forest. The fact is that most boreal forest stands are less than 100 years old, and only in the rather few areas that have escaped burning are there stands of white spruce older than 250 years.[49]

The prevalence of fire-adaptive morphologic and reproductive characteristics of many boreal plant species is further evidence pointing to a long and intimate association with fire. Seven of the ten most common trees in the boreal forest—jack pine, lodgepole pine, aspen, balsam poplar (Populus balsamifera), paper birch, tamarack, black spruce – can be classed as pioneers in their adaptations for rapid invasion of open areas. White spruce shows some pioneering abilities, too, but is less able than black spruce and the pines to disperse seed at all seasons. Only balsam fir and alpine fir seem to be poorly adapted to reproduce after fire, as their cones disintegrate at maturity, leaving no seed in the crowns.

The oldest forests in the northwest boreal region, some older than 300 years, are of white spruce occurring as pure stands on moist floodplains.[52] Here, the frequency of fire is much less than on adjacent uplands dominated by pine, black spruce and aspen. In contrast, in the Cordilleran region, fire is most frequent in the valley bottoms, decreasing upward, as shown by a mosaic of young pioneer pine and broadleaf stands below, and older spruce–fir on the slopes above.[49] Without fire, the boreal forest would become more and more homogeneous, with the long-lived white spruce gradually replacing pine, aspen, balsam poplar, and birch, and perhaps even black spruce, except on the peatlands.[53]

Climate change

[edit]During the last quarter of the twentieth century, the zone of latitude occupied by the boreal forest experienced some of the greatest temperature increases on Earth. Winter temperatures have increased more than summer temperatures. In summer, the daily low temperature has increased more than the daily high temperature.[54] The number of days with extremely cold temperatures (e.g., −20 to −40 °C; −4 to −40 °F) has decreased irregularly but systematically in nearly all the boreal region, allowing better survival for tree-damaging insects.[55] In Fairbanks, Alaska, the length of the frost-free season has increased from 60 to 90 days in the early twentieth century to about 120 days a century later.

It has been hypothesized that the boreal environments have only a few states which are stable in the long term - a treeless tundra/steppe, a forest with >75% tree cover and an open woodland with ~20% and ~45% tree cover. Thus, continued climate change would be able to force at least some of the presently existing taiga forests into one of the two woodland states or even into a treeless steppe - but it could also shift tundra areas into woodland or forest states as they warm and become more suitable for tree growth.[56]

In keeping with this hypothesis, several studies published in the early 2010s found that there was already a substantial drought-induced tree loss in the western Canadian boreal forests since the 1960s: although this trend was weak or even non-existent in the eastern forests,[57][58] it was particularly pronounced in the western coniferous forests.[59] However, in 2016, a study found no overall Canadian boreal forest trend between 1950 and 2012: while it also found improved growth in some southern boreal forests and dampened growth in the north (contrary to what the hypothesis would suggest), those patterns were statistically weak.[60]

A 2018 Landsat reanalysis confirmed that there was a drying trend and a loss of forest in western Canadian forests and some greening in the wetter east, but it had also concluded that most of the forest loss attributed to climate change in the earlier studies had instead constituted a delayed response to anthropogenic disturbance.[61] Subsequent research found that even in the forests where biomass trends did not change, there was a substantial shift towards the deciduous broad-leaved trees with higher drought tolerance over the past 65 years,[62] and another Landsat analysis of 100,000 undisturbed sites found that the areas with low tree cover became greener in response to warming, but tree mortality (browning) became the dominant response as the proportion of existing tree cover increased.[63]

While the majority of studies on boreal forest transitions have been done in Canada, similar trends have been detected in the other countries. Summer warming has been shown to increase water stress and reduce tree growth in dry areas of the southern boreal forest in central Alaska and portions of far eastern Russia.[64] In Siberia, the taiga is converting from predominantly needle-shedding larch trees to evergreen conifers in response to a warming climate. This is likely to further accelerate warming, as the evergreen trees will absorb more of the sun's rays. Given the vast size of the area, such a change has the potential to affect areas well outside of the region.[65] In much of the boreal forest in Alaska, the growth of white spruce trees are stunted by unusually warm summers, while trees on some of the coldest fringes of the forest are experiencing faster growth than previously.[66] Lack of moisture in the warmer summers are also stressing the birch trees of central Alaska.[67]

In addition to these observations, there has also been work on projecting future forest trends. A 2018 study of the seven tree species dominant in the Eastern Canadian forests found that while 2 °C warming alone increases their growth by around 13% on average, water availability is much more important than temperature and further warming of up to 4 °C would result in substantial declines unless matched by increases in precipitation.[68] A 2019 study suggested that the forest plots commonly used to evaluate boreal forest response to climate change tend to have less evolutionary competition between trees than the typical forest, and that with strong competition, there was little net growth in response to warming.[69]

Climatic change only stimulated growth for trees under weak competition in central boreal forests. A 2021 paper had confirmed that the boreal forests are much more strongly affected by climate change than the other forest types in Canada and projected that most of the eastern Canadian boreal forests would reach a tipping point around 2080 under the RCP 8.5 scenario which represents the largest potential increase in anthropogenic emissions.[70] Another 2021 study projected that under the "moderate" SSP2-4.5 scenario, boreal forests would experience a 15% worldwide increase in biomass by the end of the century, but this would be more than offset by the 41% biomass decline in the tropics.[71]

In 2022, the results of a 5-year warming experiment in North America had shown that the juveniles of tree species which currently dominate the southern margins of the boreal forests fare the worst in response to even 1.5 °C or +3.1 °C of warming and the associated reductions in precipitation. While the temperate species which would benefit from such conditions are also present in the southern boreal forests, they are both rare and have slower growth rates.[72]

A 2022 assessment of tipping points in the climate system designated two inter-related tipping points associated with climate change - the die-off of taiga at its southern edge and the area's consequent reversion to grassland (similar to the Amazon rainforest dieback) and the opposite process to the north, where the rapid warming of the adjacent tundra areas converts them to taiga. While both of these processes can already be observed today, the assessment believes that they would likely not become unstoppable (and thus meet the definition of a tipping point) until global warming of around 4 °C. However, the certainty level is still limited and it is possible that 1.5 °C would be sufficient for either tipping point; on the other hand, the southern die-off may not be inevitable until 5 °C, while the replacement of tundra with taiga may require 7.2 °C.[73][74]

Once the "right" level of warming is met, either process would take at least 40–50 years to finish, and is more likely to unfold over a century or more. While the southern die-off would involve the loss of around 52 billion tons of carbon, the net result is cooling of around 0.18 °C globally and between 0.5 °C to 2 °C regionally. Likewise, boreal forest expansion into tundra has a net global warming effect of around 0.14 °C globally and 0.5 °C to 1 °C regionally, even though new forest growth captures around 6 billion tons of carbon. In both cases, this is due to the snow-covered ground having a much greater albedo than the forests.[73][74] According to a later study, disappearing of boreal forests can also increase warming despite the effect on albedo, while the conclusion about cooling from deforestation in these areas made by previous studies results from the failure of models to properly capture the effects of evapotranspiration.[75]

Primary boreal forests hold 1,042 billion tonnes of carbon, more than currently found in the atmosphere, 2 times more than all human caused GHG emissions since the year 1870. In a warmer climate their ability to store carbon will be reduced.[76]

Other threats

[edit]Human activities

[edit]

Some of the larger cities situated in this biome are Murmansk,[77] Arkhangelsk, Yakutsk, Anchorage,[78] Yellowknife, Tromsø, Luleå, and Oulu.

Large areas of Siberia's taiga have been harvested for lumber since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Previously, the forest was protected by the restrictions of the Soviet Ministry of Forestry, but with the collapse of the Union, the restrictions regarding trade with Western nations have vanished. Trees are easy to harvest and sell well, so loggers have begun harvesting Russian taiga evergreen trees for sale to nations previously forbidden by Soviet law.[79]

Insects

[edit]Recent years[when?] have seen outbreaks of insect pests in forest-destroying plagues: the spruce-bark beetle (Dendroctonus rufipennis) in Yukon and Alaska;[80] the mountain pine beetle in British Columbia; the aspen-leaf miner; the larch sawfly; the spruce budworm (Choristoneura fumiferana);[81] the spruce coneworm.[82]

Pollution

[edit]The effect of sulphur dioxide on woody boreal forest species was investigated by Addison et al. (1984),[83] who exposed plants growing on native soils and tailings to 15.2 μmol/m3 (0.34 ppm) of SO2 on CO2 assimilation rate (NAR). The Canadian maximum acceptable limit for atmospheric SO2 is 0.34 ppm. Fumigation with SO2 significantly reduced NAR in all species and produced visible symptoms of injury in 2–20 days. The decrease in NAR of deciduous species (trembling aspen [Populus tremuloides], willow [Salix], green alder [Alnus viridis], and white birch [Betula papyrifera]) was significantly more rapid than of conifers (white spruce, black spruce [Picea mariana], and jack pine [Pinus banksiana]) or an evergreen angiosperm (Labrador tea) growing on a fertilized Brunisol.

These metabolic and visible injury responses seemed to be related to the differences in S uptake owing in part to higher gas exchange rates for deciduous species than for conifers. Conifers growing in oil sands tailings responded to SO2 with a significantly more rapid decrease in NAR compared with those growing in the Brunisol, perhaps because of predisposing toxic material in the tailings. However, sulphur uptake and visible symptom development did not differ between conifers growing on the 2 substrates.

Acidification of precipitation by anthropogenic, acid-forming emissions has been associated with damage to vegetation and reduced forest productivity, but 2-year-old white spruce that were subjected to simulated acid rain (at pH 4.6, 3.6, and 2.6) applied weekly for 7 weeks incurred no statistically significant (P 0.05) reduction in growth during the experiment compared with the background control (pH 5.6) (Abouguendia and Baschak 1987).[84] However, symptoms of injury were observed in all treatments, the number of plants and the number of needles affected increased with increasing rain acidity and with time. Scherbatskoy and Klein (1983)[85] found no significant effect of chlorophyll concentration in white spruce at pH 4.3 and 2.8, but Abouguendia and Baschak (1987)[84] found a significant reduction in white spruce at pH 2.6, while the foliar sulphur content significantly greater at pH 2.6 than any of the other treatments.

Protection

[edit]

The taiga stores enormous quantities of carbon, more than the world's temperate and tropical forests combined, much of it in wetlands and peatland.[86] In fact, current estimates place boreal forests as storing twice as much carbon per unit area as tropical forests.[87] Wildfires could use up a significant part of the global carbon budget, so fire management at about 12 dollars per tonne of carbon not released[6] is very cheap compared to the social cost of carbon.

Some nations are discussing protecting areas of the taiga by prohibiting logging, mining, oil and gas production, and other forms of development. Responding to a letter signed by 1,500 scientists calling on political leaders to protect at least half of the boreal forest,[88] two Canadian provincial governments, Ontario and Quebec, offered election promises to discuss measures in 2008 that might eventually classify at least half of their northern boreal forest as "protected".[89][90] Although both provinces admitted it would take decades to plan, working with Aboriginal and local communities and ultimately mapping out precise boundaries of the areas off-limits to development, the measures were touted to create some of the largest protected areas networks in the world once completed. Since then, however, very little action has been taken.

For instance, in February 2010 the Canadian government established limited protection for 13,000 square kilometres of boreal forest by creating a new 10,700-square-kilometre park reserve in the Mealy Mountains area of eastern Canada and a 3,000-square-kilometre waterway provincial park that follows alongside the Eagle River from headwaters to sea.[91]

Natural disturbance

[edit]One of the biggest areas of research and a topic still full of unsolved questions is the recurring disturbance of fire and the role it plays in propagating the lichen woodland.[92] The phenomenon of wildfire by lightning strike is the primary determinant of understory vegetation, and because of this, it is considered to be the predominant force behind community and ecosystem properties in the lichen woodland.[93] The significance of fire is clearly evident when one considers that understory vegetation influences tree seedling germination in the short term and decomposition of biomass and nutrient availability in the long term.[93]

The recurrent cycle of large, damaging fire occurs approximately every 70 to 100 years.[94] Understanding the dynamics of this ecosystem is entangled with discovering the successional paths that the vegetation exhibits after a fire. Trees, shrubs, and lichens all recover from fire-induced damage through vegetative reproduction as well as invasion by propagules.[95] Seeds that have fallen and become buried provide little help in re-establishment of a species. The reappearance of lichens is reasoned to occur because of varying conditions and light/nutrient availability in each different microstate.[95] Several different studies have been done that have led to the formation of the theory that post-fire development can be propagated by any of four pathways: self replacement, species-dominance relay, species replacement, or gap-phase self replacement.[92]

Self-replacement is simply the re-establishment of the pre-fire dominant species. Species-dominance relay is a sequential attempt of tree species to establish dominance in the canopy. Species replacement is when fires occur in sufficient frequency to interrupt species dominance relay. Gap-Phase Self-Replacement is the least common and so far has only been documented in Western Canada. It is a self replacement of the surviving species into the canopy gaps after a fire kills another species. The particular pathway taken after fire disturbance depends on how the landscape is able to support trees as well as fire frequency.[96] Fire frequency has a large role in shaping the original inception of the lower forest line of the lichen woodland taiga.

It has been hypothesized by Serge Payette that the spruce-moss forest ecosystem was changed into the lichen woodland biome due to the initiation of two compounded strong disturbances: large fire and the appearance and attack of the spruce budworm.[97] The spruce budworm is a deadly insect to the spruce populations in the southern regions of the taiga. J.P. Jasinski confirmed this theory five years later stating, "Their [lichen woodlands] persistence, along with their previous moss forest histories and current occurrence adjacent to closed moss forests, indicate that they are an alternative stable state to the spruce–moss forests".[98]

Taiga ecoregions

[edit]See also

[edit]- Birds of North American boreal forests

- Boreal Forest Conservation Framework

- Drunken trees – effect of global warming on the taiga

- Fire and carbon cycling in boreal forests

- Intact forest landscape

- Agafia Lykov

- Scandinavian and Russian taiga

- Success of fire suppression in northern forests

- Taiga Rescue Network (TRN)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Berkeley: The forest biome". Ucmp.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 20 June 2019. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ "List of Plants & Animals in the Canadian Wilderness". Trails.com. 27 July 2010. Archived from the original on 14 September 2018. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- ^ a b "Taiga | Plants, Animals, Climate, Location, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 4 May 2023.

- ^ Hoffmann, Robert S. (1958). "The Meaning of the Word "Taiga"". Ecology. 39 (3): 540–541. Bibcode:1958Ecol...39..540H. doi:10.2307/1931768. JSTOR 1931768.

- ^ Graham, Karen (19 May 2021). "'Zombie fires' may become more common as the climate warms". Digital Journal. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ a b Phillips, Carly (27 April 2022). "Carbon Emissions from Boreal Forest Wildfires". Union of Concerned Scientists. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ "How should the world's nations account for the carbon absorbed by their forests? We better figure it out". Bellona.org. 18 May 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ "Taiga biological station: FAQ". Wilds.m.ca. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ Sporrong, Ulf (2003). "The Scandinavian landscape and its resources". In Helle, Knut (ed.). The Cambridge History of Scandinavia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 22. ISBN 978-0-521-47299-9.

- ^ "Marietta the Taiga and Boreal forest". Marietta.edu. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ "Yakutsk climate". Worldclimate.com. 4 February 2007. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ "Interior Alaska-Yukon lowland taiga". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ "radford:Taiga climate". Radford.edu. Archived from the original on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ a b Encyclopedia Universalis édition 1976 Vol. 2 ASIE – Géographie physique, p. 568 (in French)

- ^ "The eastern forest – boreal transition". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ "Canada: Taiga Shield reference" (PDF). Enr.gov.nt.ca. Retrieved 28 February 2022.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Climate of Canadian ecozones". Geography.ridley.on.ca. Archived from the original on 5 May 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ "Taiga". Blueplanetbiomes. Archived from the original on 10 April 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ "Southwest Yukon:Frost-free days". Yukon.taiga.net. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ "Kenozersky National Park". Wild-russia.org. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ "University of Helsinki: Carabid diversity in Finnish taiga" (PDF). Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ "Tundra". Blueplanetbiomes. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ "NatureWorks:Tundra". Nhptv.org. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ "The Arctic". saskschools.ca. Archived from the original on 10 April 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ A.P. Sayre, Taiga, (New York: Twenty-First Century Books, 1994) 16.

- ^ Arno & Hammerly 1984, Arno et al. 1995

- ^ "Finland vegetation zone and freshwater biome" (PDF). 113.139. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 September 2011. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ^ "Tampere/Pirkkala, Finland Weather History and Climate Data". Worldclimate.com. 4 February 2007. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ a b Sayre, 19.

- ^ "Study reveals for first time true diversity of life in soils across the globe, new species discovered". Physorg.com. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ^ Sayre, 19–20.

- ^ Sayre, 12–13.

- ^ C. Michael Hogan, Black Spruce: Picea mariana, GlobalTwitcher.com, ed. Nicklas Stromberg, November, 2008 Archived 5 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ George H. La Roi. "Boreal forest". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ^ "Forest". forest.jrc.ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- ^ a b Sayre, 23.

- ^ "Canada's Boreal Forest". Hinterland Who's Who. Archived from the original on 3 January 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ "North American Elk". Hinterland Who's Who. Archived from the original on 3 January 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ "Western roe deer". Borealforest.org. Archived from the original on 26 May 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ "Government of Canada to Send Wood Bison to Russian Conservation Project". Parks Canada. 23 January 2012. Archived from the original on 9 February 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ^ "Boreal Forest". Boreal Songbird Initiative. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ Sayre, 28.

- ^ Rowe, J. S. (1955). "Factors influencing white spruce reproduction in Manitoba and Saskatchewan". Can. Dep. Northern Affairs and National Resources. For. Branch, For. Res. Div., Ottawa ON, Project MS-135, Silv. Tech. Note 3.

- ^ a b Amiro, B. D.; Stocks, B. J.; Alexander, M. E.; Flannigan, M. D.; Wotton, B. M. (2001). "Fire, climate change, carbon and fuel management in the Canadian boreal forest". Int. J. Wildland Fire. 10 (4): 405–13. doi:10.1071/WF01038.

- ^ a b c d Heinselman, M. L. (1981). "Fire intensity and frequency as factors in the distribution and structure of northern ecosystems". Proceedings of the Conference: Fire Regimes in Ecosystem Properties, Dec. 1978, Honolulu, Hawaii. USDA. For. Serv., Washington DC, Gen. Tech. Rep. WO-26. pp. 7–57.

- ^ Heinselman, M. L. (1973). "Fire in the virgin forests of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area, Minnesota". Quat. Res. 3 (3): 329–82. Bibcode:1973QuRes...3..329H. doi:10.1016/0033-5894(73)90003-3. S2CID 18430692.

- ^ Van Wagner, C. E. (1978). "Age-class distribution and the forest cycle". Can. J. For. Res. 8: 220–27. doi:10.1139/x78-034.

- ^ Flannigan, M. D.; Bergeron, Y.; Engelmark, O.; Wotton, B. M. (1998). "Future wildfire in circumboreal forests in relation to global warming". J. Veg. Sci. 9 (4): 469–76. Bibcode:1998JVegS...9..469F. doi:10.2307/3237261. JSTOR 3237261.

- ^ a b c d Rowe, J. S.; Scotter, G. W. (1973). "Fire in the boreal forest". Quaternary Res. 3 (3): 444–64. Bibcode:1973QuRes...3..444R. doi:10.1016/0033-5894(73)90008-2. S2CID 129118655. [E3680, Coates et al. 1994]

- ^ La Roi, G. H. (1967). "Ecological studies in the boreal spruce–fir forests of the North American taiga. I. Analysis of the vascular flora". Ecol. Monogr. 37 (3): 229–53. Bibcode:1967EcoM...37..229L. doi:10.2307/1948439. JSTOR 1948439.

- ^ Bryson, R. A.; Irving, W. H.; Larson, J. A. (1965). "Radiocarbon and soil evidence of former forest in the southern Canadian tundra". Science. 147 (3653): 46–48. Bibcode:1965Sci...147...46B. doi:10.1126/science.147.3653.46. PMID 17799777. S2CID 46218641.

- ^ Rowe, J. S. (1970). "Spruce and fire in northwest Canada and Alaska". In Komarek, E. V. (ed.). Proc. 10th Annual Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference, Tallahassee FL. pp. 245–54.

- ^ Raup, H. M.; Denny, C. S. (1950). "Photointerpretation of the terrain along the southern part of the Alaska highway". US Geol. Surv. Bull. 963-D: 95–135. Bibcode:1950usgs.rept....6R. doi:10.3133/b963D.

- ^ Wilmking, M. (9 October 2009). "Coincidence and Contradiction in the Warming Boreal Forest". Geophysical Research Letters. 32 (15): L15715. Bibcode:2005GeoRL..3215715W. doi:10.1029/2005GL023331.

- ^ Seidl, Rupert; Thom, Dominik; Kautz, Markus; Martin-Benito, Dario; Peltoniemi, Mikko; Vacchiano, Giorgio; Wild, Jan; Ascoli, Davide; Petr, Michal; Honkaniemi, Juha; Lexer, Manfred J.; Trotsiuk, Volodymyr; Mairota, Paola; Svoboda, Miroslav; Fabrika, Marek; Nagel, Thomas A.; Reyer, Christopher P. O. (31 May 2017). "Forest disturbances under climate change". Nature. 7 (6): 395–402. Bibcode:2017NatCC...7..395S. doi:10.1038/nclimate3303. PMC 5572641. PMID 28861124.

- ^ Scheffer, Marten; Hirota, Marina; Holmgren, Milena; Van Nes, Egbert H.; Chapin, F. Stuart (26 December 2012). "Thresholds for boreal biome transitions". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (52): 21384–21389. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10921384S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1219844110. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3535627. PMID 23236159.

- ^ Peng, Changhui; Ma, Zhihai; Lei, Xiangdong; Zhu, Qiuan; Chen, Huai; Wang, Weifeng; Liu, Shirong; Li, Weizhong; Fang, Xiuqin; Zhou, Xiaolu (20 November 2011). "A drought-induced pervasive increase in tree mortality across Canada's boreal forests". Nature Climate Change. 1 (9): 467–471. Bibcode:2011NatCC...1..467P. doi:10.1038/nclimate1293.

- ^ Ma, Zhihai; Peng, Changhui; Zhu, Qiuan; Chen, Huai; Yu, Guirui; Li, Weizhong; Zhou, Xiaolu; Wang, Weifeng; Zhang, Wenhua (30 January 2012). "Regional drought-induced reduction in the biomass carbon sink of Canada's boreal forests". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (7): 2423–2427. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109.2423M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1111576109. PMC 3289349. PMID 22308340.

- ^ Chen, Han Y. H.; Luo, Yong (2 July 2015). "Net aboveground biomass declines of four major forest types with forest ageing and climate change in western Canada's boreal forests". Global Change Biology. 21 (10): 3675–3684. Bibcode:2015GCBio..21.3675C. doi:10.1111/gcb.12994. PMID 26136379. S2CID 25403205.

- ^ Girardin, Martin P.; Bouriaud, Olivier; Hogg, Edward H.; Kurz, Werner; Zimmermann, Niklaus E.; Metsaranta, Juha M.; de Jong, Rogier; Frank, David C.; Esper, Jan; Büntgen, Ulf; Guo, Xiao Jing; Bhatti, Jagtar (12 December 2016). "No growth stimulation of Canada's boreal forest under half-century of combined warming and CO2 fertilization". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (52): E8406 – E8414. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113E8406G. doi:10.1073/pnas.1610156113. PMC 5206510. PMID 27956624.

- ^ Sulla-Menashe, Damien; Woodcock, Curtis E; Friedl, Mark A (4 January 2018). "Canadian boreal forest greening and browning trends: an analysis of biogeographic patterns and the relative roles of disturbance versus climate drivers". Environmental Research Letters. 13 (1): 014007. Bibcode:2018ERL....13a4007S. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/aa9b88. S2CID 158470300.

- ^ Hisano, Masumi; Ryo, Masahiro; Chen, Xinli; Chen, Han Y. H. (16 May 2021). "Rapid functional shifts across high latitude forests over the last 65 years". Global Change Biology. 27 (16): 3846–3858. Bibcode:2021GCBio..27.3846H. doi:10.1111/gcb.15710. PMID 33993581. S2CID 234744857.

- ^ Berner, Logan T.; Goetz, Scott J. (24 February 2022). "Satellite observations document trends consistent with a boreal forest biome shift". Global Change Biology. 28 (10): 3846–3858. Bibcode:2022GCBio..28.3275B. doi:10.1111/gcb.16121. PMC 9303657. PMID 35199413.

- ^ "Boreal Forests and Climate Change - Changes in Climate Parameters and Some Responses, Effects of Warming on Tree Growth on Productive Sites". Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ Shuman, Jacquelyn Kremper; Shugart, Herman Henry; O'Halloran, Thomas Liam (25 March 2011). "Russian boreal forests undergoing vegetation change, study shows". Global Change Biology. 17 (7): 2370–84. Bibcode:2011GCBio..17.2370S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02417.x. S2CID 86357569. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ^ "Fairbanks Daily News-Miner – New study states boreal forests shifting as Alaska warms". Newsminer.com. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ^ Morello, Lauren. "Forest Changes in Alaska Reveal Changing Climate". Scientific American. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ^ D'Orangeville, Loïc; Houle, Daniel; Duchesne, Louis; Phillips, Richard P.; Bergeron, Yves; Kneeshaw, Daniel (10 August 2018). "Beneficial effects of climate warming on boreal tree growth may be transitory". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 3213. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9.3213D. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-05705-4. PMC 6086880. PMID 30097584.

- ^ Luo, Yong; McIntire, Eliot J. B.; Boisvenue, Céline; Nikiema, Paul P.; Chen, Han Y. H. (17 June 2019). "Climatic change only stimulated growth for trees under weak competition in central boreal forests". Journal of Ecology. 9: 36–46. doi:10.1111/1365-2745.13228. S2CID 196649104.

- ^ Boulanger, Yan; Puigdevall, Jesus Pascual (3 April 2021). "Boreal forests will be more severely affected by projected anthropogenic climate forcing than mixedwood and northern hardwood forests in eastern Canada". Landscape Ecology. 36 (6): 1725–1740. Bibcode:2021LaEco..36.1725B. doi:10.1007/s10980-021-01241-7. S2CID 226959320.

- ^ Larjavaara, Markku; Lu, Xiancheng; Chen, Xia; Vastaranta, Mikko (12 October 2021). "Impact of rising temperatures on the biomass of humid old-growth forests of the world". Carbon Balance and Management. 16 (1): 31. Bibcode:2021CarBM..16...31L. doi:10.1186/s13021-021-00194-3. PMC 8513374. PMID 34642849.

- ^ Reich, Peter B.; Bermudez, Raimundo; Montgomery, Rebecca A.; Rich, Roy L.; Rice, Karen E.; Hobbie, Sarah E.; Stefanski, Artur (10 August 2022). "Even modest climate change may lead to major transitions in boreal forests". Nature. 608 (7923): 540–545. Bibcode:2022Natur.608..540R. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05076-3. PMID 35948640. S2CID 251494296.

- ^ a b Armstrong McKay, David; Abrams, Jesse; Winkelmann, Ricarda; Sakschewski, Boris; Loriani, Sina; Fetzer, Ingo; Cornell, Sarah; Rockström, Johan; Staal, Arie; Lenton, Timothy (9 September 2022). "Exceeding 1.5°C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points". Science. 377 (6611) eabn7950. doi:10.1126/science.abn7950. hdl:10871/131584. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 36074831. S2CID 252161375.

- ^ a b Armstrong McKay, David (9 September 2022). "Exceeding 1.5°C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points – paper explainer". climatetippingpoints.info. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ M. Makarieva, Anastassia; V. Nefiodov, Andrei; Rammig, Anja; Donato Nobre, Antonio (20 July 2023). "Re-appraisal of the global climatic role of natural forests for improved climate projections and policies". Frontiers in Forests and Global Change. 6. arXiv:2301.09998. Bibcode:2023FrFGC...650191M. doi:10.3389/ffgc.2023.1150191.

- ^ "Primary Forests: Boreal, Temperate, Tropical". Woodwell Climate Research Center. Woodwell Climate Research Center, INTACT, Griffits University, GEOS institute, Frankfurt Zoological Society, Australian Rainforest Conservation Society. 17 December 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- ^ "Murmansk climate". Worldclimate.com. 4 February 2007. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ "Anchorage climate". Worldclimate.com. 4 February 2007. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ "Taiga Deforestation". American.edu. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ "A New Method to Reconstruct Bark Beetle Outbreaks". Colorado.edu. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ "Spruce budworm and sustainable management of the boreal forest". Cfs.nrcan.gc.ca. 5 December 2007. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ "ALASKA'S CHANGING BOREAL FOREST" (PDF). Fs.fed.us. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ Addison, P.A.; Malhotra, S.S.; Khan, A.A. 1984. "Effect of sulfur dioxide on woody boreal forest species grown on native soils and tailings". J. Environ. Qual. 13(3):333–36.

- ^ a b Abouguendia, Z.M.; Baschak, L.A. 1987. "Response of two western Canadian conifers to simulated acidic precipitation". Water, Air and Soil Pollution 33:15–22.

- ^ Scherbatskoy, T.; Klein, R.M. 1983. "Response of spruce Picea glauca and birch Betula alleghaniensis foliage to leaching by acidic mists". J. Environ. Qual. 12:189–95.

- ^ Ruckstuhl, K. E.; Johnson, E. A.; Miyanishi, K. (July 2008). "Boreal forest and global change". Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 363 (1501): 2245–49. doi:10.1098/rstb.2007.2196. PMC 2387060. PMID 18006417.

- ^ "Report: The Carbon the World Forgot". Boreal Songbird Initiative. 12 May 2014.

- ^ "1,500 Scientists Worldwide Call for Protection of Canada's Boreal Forest". Boreal Songbird Initiative. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- ^ Gillespie, Kerry (15 July 2008). "Ontario to protect vast tract". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on 29 February 2012. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- ^ Marsden, William (16 November 2008). "Charest promises to protect north". Montreal Gazette. Archived from the original on 5 April 2011. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- ^ Braun, David (7 February 2010). "Boreal landscapes added to Canada's parks Boreal landscapes added to Canada's parks". NatGeo News Watch: News Editor David Braun's Eye on the World. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 15 February 2010. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- ^ a b Kurkowski, 1911.

- ^ a b Nilsson, 421.

- ^ Johnson, 212.

- ^ a b Johnson, 200

- ^ Kurkowski, 1912.

- ^ Payette, 289.

- ^ Jasinski, 561.

- General references

- Arno, S. F. & Hammerly, R. P. (1984). Timberline. Mountain and Arctic Forest Frontiers. Seattle: The Mountaineers. ISBN 0-89886-085-7.

- Arno, S. F.; Worral, J. & Carlson, C. E. (1995). "Larix lyallii: Colonist of tree line and talus sites". In Schmidt, W. C. & McDonald, K. J. (eds.). Ecology and Management of Larix Forests: A Look Ahead. USDA Forest Service General Technical Report GTR-INT-319. pp. 72–78.

- Hoffmann, Robert S. (1958). "The Meaning of the Word 'Taiga'". Ecology. 39 (3): 540–541. Bibcode:1958Ecol...39..540H. doi:10.2307/1931768. JSTOR 1931768.

- Jasinski, J. P. (2005). "The Creation of Alternative Stable States in Southern Boreal Forest: Quebec, Canada". Ecological Monographs. 75 (4): 561–583. Bibcode:2005EcoM...75..561J. doi:10.1890/04-1621.

- Johnson, E. A. (1981). "Vegetation Organization and Dynamics of Lichen Woodland Communities in the Northwest Territories". Ecology. 62 (1): 200–215. doi:10.2307/1936682. JSTOR 1936682. S2CID 86749540.

- Kurkowski, Thomas (2008). "Relative Importance of Different Secondary Successional Pathways in an Alaskan Boreal Forest". Canadian Journal of Forest Research. 38 (7): 1911–1923. Bibcode:2008CaJFR..38.1911K. doi:10.1139/X08-039. S2CID 17586608.

- Payette, Serge (2000). "Origin of the lichen woodland at its southern range limit in eastern Canada: the catastrophic impact of insect defoliators and fire on the spruce-moss forest". Canadian Journal of Forest Research. 30 (2): 288–305. Bibcode:2000CaJFR..30..288P. doi:10.1139/x99-207.

- Nilsson, M. C. (2005). "Understory vegetation as a forest ecosystem driver, evidence from the northern Swedish boreal forest". Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 3 (8): 421–428. doi:10.1890/1540-9295(2005)003[0421:UVAAFE]2.0.CO;2.

Further reading

[edit]- Day, Trevor; Richard Garratt (2006). Taiga. Facts On File. ISBN 978-0-8160-5329-2.

- Gawthrop, Daniel (1999). Vanishing Halo: Saving the Boreal Forest. Greystone Books/David Suzuki Foundation. ISBN 978-0-89886-681-0.

- Sayre, April Pulley (1994). Taiga. Twenty-First Century Books. ISBN 978-0-8050-2830-0.

External links

[edit]- The Conservation Value of the North American Boreal Forest from an Ethnobotanical perspective a report by the Boreal Songbird Initiative

- Boreal Canadian Initiative

- Boreal Forests Project Regeneration

- International Boreal Conservation campaign

- Tundra and Taiga

- Threats to Boreal Forests Greenpeace

- Campaign against lumber giant Weyerhaeuser's logging practices in the Canadian boreal forest Rainforest Action Network

- Arctic and Taiga Canadian Geographic

- Terraformers Canadian Taiga Conservation Foundation

- Coniferous Forest, Earth Observatory Archived 4 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine NASA

- Taiga Rescue Network (TRN) Archived 6 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine A network of NGOs, indigenous peoples or individuals that works to protect the boreal forests.

- Index of Boreal Forests/Taiga ecoregions at bioimages.Vanderbilt.edu

- The Canadian Boreal Forest The Nature Conservancy and its partners

- Slater museum of natural history: Taiga

- Taiga Biological Station—founded by William (Bill) Pruitt Jr., University of Manitoba.

![Lakes and other water bodies are common in the taiga. The Helvetinjärvi National Park, Finland, is situated in the closed canopy taiga (mid-boreal to south-boreal)[27] with mean annual temperature of 4 °C (39 °F).[28]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/53/Helvetinj%C3%A4rvi.JPG/250px-Helvetinj%C3%A4rvi.JPG)