Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

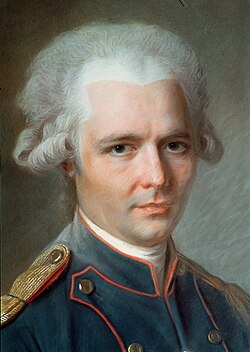

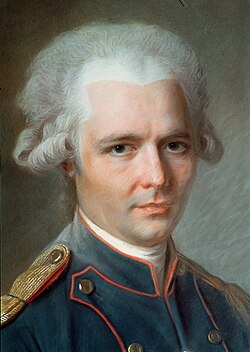

Pierre Choderlos de Laclos

View on Wikipedia

Pierre Ambroise François Choderlos de Laclos (French: [pjɛʁ ɑ̃bʁwaz fʁɑ̃swa ʃɔdɛʁlo də laklo]; 18 October 1741 – 5 September 1803) was a French novelist, official, Freemason and army general, best known for writing the epistolary novel Les Liaisons dangereuses (Dangerous Liaisons) (1782).

Key Information

A unique case in French literature, he was for a long time considered to be as scandalous a writer as the Marquis de Sade or Nicolas Restif de la Bretonne. He was a military officer with no illusions about human relations, and an amateur writer; however, his initial plan was to "write a work which departed from the ordinary, which made a noise, and which would remain on earth after his death"; from this point of view he mostly attained his goals with the fame of his masterwork Les Liaisons dangereuses. It is one of the masterpieces of novelistic literature of the 18th century, which explores the amorous intrigues of the aristocracy. It has inspired many critical and analytic commentaries, plays and films.

Biography

[edit]Born in Amiens into a bourgeois family, in 1761 Laclos began studies at the School of Artillery of La Fère, ancestor of the École Polytechnique.[1] As a young lieutenant, he briefly served in a garrison at La Rochelle until the end of the Seven Years' War (1763). Postings to Strasbourg (1765–1769), Grenoble (1769–1775) and Besançon (1775–1776) followed.

In 1763 Laclos became a Freemason in "L'Union" military lodge in Toul.[2]

Despite a promotion to the rank of captain (1771), Laclos grew increasingly bored with his artillery garrison duties and with the company of soldiers; he began to devote his free time to writing. His first works, several light poems, appeared in the Almanach des Muses. Later he wrote the libretto for an opéra comique, Ernestine, inspired by a novel by Marie Jeanne Riccoboni. The music was composed by the Chevalier de Saint Georges. Its premiere on 19 July 1777, in the presence of Queen Marie Antoinette, proved a failure. In the same year, he established a new artillery school in Valence, which would include Napoleon Bonaparte among its students in the mid-1780s. On his return to Besançon in 1778 Laclos was promoted second captain of the Engineers. In this period he wrote several works which showed his great admiration of Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

In 1776 Laclos requested and received affiliation with the "Henri IV" lodge in Paris. There he helped Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orléans leading the Grand Orient of France.[3] In 1777, in front of the Grand Orient's dignitaries, he delivered a speech in which he urged the initiation of women into Freemasonry.[4]

In 1779, he was sent to Île-d'Aix (in present-day Charente-Maritime) to assist Marc René, marquis de Montalembert in the construction of fortifications there against the British. However, he spent most of his time writing his new epistolary novel, Les Liaisons dangereuses, as well as a Letter to Madame de Montalembert. When he asked for and received six months of vacation, he spent the time in Paris, writing.

Durand Neveu published Les Liaisons dangereuses in four volumes on 23 March 1782; it became a widespread success: 1,000 copies sold in a month, an exceptional result for the time. Laclos was immediately ordered to return to his garrison in Brittany; in 1783 he was sent to La Rochelle to collaborate in the construction of the new arsenal. Here he met Marie-Soulange Duperré, whom he would marry on 3 May 1786,[5] and remain with for the rest of his life. The following year, he began a project of numbering the streets of Paris.

In 1788, Laclos left the army, entering the service of Louis Philippe, Duke of Orléans, for whom, after the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789, he carried out intense diplomatic activity.[clarification needed] In 1790/91 he was the editor of "Journal des amis de la constitution", connected with the Feuillants.[6][7] Captured by Republican ideals, he left the Duke to obtain a place as commissar in the Ministry of War. His reorganization has been credited[by whom?] as having a role in the French Revolutionary Army's victory in the Battle of Valmy (20 September 1792). Later, however, after the desertion (April 1793) of general Charles François Dumouriez, he was arrested as an Orleaniste, being freed after the Thermidorian Reaction of 27 July 1794.

He thenceforth spent some time in ballistic studies, which led him to the invention of the modern artillery shell.[8] In 1795 he requested reinstatement in the Army by the Committee of Public Safety; the request was ignored. His attempts to obtain a diplomatic position and to found a bank also proved unsuccessful. Eventually, Laclos met the young general and recently appointed (November 1799) First Consul, Napoleon Bonaparte, and joined his party. On 16 January 1800 he was reinstated in the Army as Brigadier General in the Army of the Rhine; he took part in the Battle of Biberach (9 May 1800).

Made commander-in-chief of Reserve Artillery in Italy (1803), Laclos died shortly afterward in the former convent of St. Francis of Assisi at Taranto, probably of dysentery and malaria. He was buried in the fort still bearing his name (Forte de Laclos) in the Isola di San Paolo near the city, built under his direction. Following the restoration of the House of Bourbon in southern Italy in 1815, his burial tomb was destroyed; it is believed[by whom?] that his bones were tossed into the sea.

Bibliography

[edit]Novels

[edit]- Les Liaisons dangereuses (1782)

Poems

[edit]- Poésies fugitives (1783)

Plays

[edit]- Ernestine (1777, opéra comique)[9]

Non-fiction

[edit]- Des Femmes et de leur éducation (1783)

- Folies philosophiques par un homme retiré du monde (1784)

- Instructions aux assemblées de bailliage (1789)

- Journal des amis de la Constitution (1790–1791)

- De la guerre et de la paix (1795)

- Continuation des causes secrètes de la révolution du neuf thermidor (1795)

References

[edit]- ^ (Pascale Hellégouarc’h, Gallica: Les essentiels Littérature

- ^ Dictionnaire Universelle de la Franc-Maçonnerie (Marc de Jode, Monique Cara and Jean-Marc CARA – ed. Larousse 2011)

- ^ Ce que la France doit aux francs-maçons (Laurent Kupferman and Emmanuel Pierrat – Grund ed. 2012)

- ^ Dictionnaire Universelle de la Franc-Maçonnerie, p. 181 (Marc de Jode, Monique Cara and Jean-Marc Cara – ed. Larousse 2011)

- ^ "Marie-Soulange Duperré" Pinterest retrieved March 1, 2017

- ^ "Journal des amis de la Constitution 13T/8/43". Archives du Calvados.

- ^ "Journal de la Société des amis de la constitution monarchique". Gallica. Société des amis de la constitution monarchique. 18 December 1790. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ Gillispie, Charles Coulston (1992). "Science and Secret Weapons Development in Revolutionary France, 1792-1804: A Documentary History". Historical Studies in the Physical and Biological Sciences. 23 (1): 105. doi:10.2307/27757692. JSTOR 27757692.

- ^ "Pierre Choderlos de Laclos (Œuvres) - aLaLettre". www.alalettre.com. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

Sources

[edit]- Bertaud, Jean-Paul (2003). Choderlos de Laclos l'auteur des Liaisons dangereuses. Paris: Fayard. ISBN 2-213-61642-6.

Further reading

[edit]- The Dangerous Memoir of Citizen Sade (2000) by A. C. H. Smith (A biographical novel, an account of the period of the Terror in the French Revolution, told by two writers who were incarcerated together and loathed each other: Laclos and the Marquis de Sade.)