Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Connectionism

View on Wikipedia

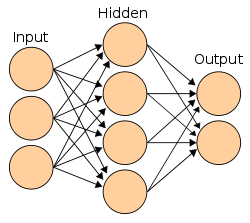

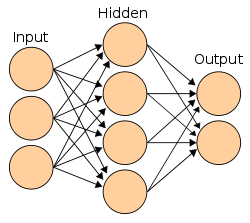

Connectionism is an approach to the study of human mental processes and cognition that utilizes mathematical models known as connectionist networks or artificial neural networks.[1]

Connectionism has had many "waves" since its beginnings. The first wave appeared 1943 with Warren Sturgis McCulloch and Walter Pitts both focusing on comprehending neural circuitry through a formal and mathematical approach,[2] and Frank Rosenblatt who published the 1958 paper "The Perceptron: A Probabilistic Model For Information Storage and Organization in the Brain" in Psychological Review, while working at the Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory.[3] The first wave ended with the 1969 book about the limitations of the original perceptron idea, written by Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert, which contributed to discouraging major funding agencies in the US from investing in connectionist research.[4] With a few noteworthy deviations, most connectionist research entered a period of inactivity until the mid-1980s. The term connectionist model was reintroduced in a 1982 paper in the journal Cognitive Science by Jerome Feldman and Dana Ballard.

The second wave blossomed in the late 1980s, following a 1987 book about Parallel Distributed Processing by James L. McClelland, David E. Rumelhart et al., which introduced a couple of improvements to the simple perceptron idea, such as intermediate processors (now known as "hidden layers") alongside input and output units, and used a sigmoid activation function instead of the old "all-or-nothing" function. Their work built upon that of John Hopfield, who was a key figure investigating the mathematical characteristics of sigmoid activation functions.[3] From the late 1980s to the mid-1990s, connectionism took on an almost revolutionary tone when Schneider,[5] Terence Horgan and Tienson posed the question of whether connectionism represented a fundamental shift in psychology and so-called "good old-fashioned AI," or GOFAI.[3] Some advantages of the second wave connectionist approach included its applicability to a broad array of functions, structural approximation to biological neurons, low requirements for innate structure, and capacity for graceful degradation.[6] Its disadvantages included the difficulty in deciphering how ANNs process information or account for the compositionality of mental representations, and a resultant difficulty explaining phenomena at a higher level.[7]

The current (third) wave has been marked by advances in deep learning, which have made possible the creation of large language models.[3] The success of deep-learning networks in the past decade has greatly increased the popularity of this approach, but the complexity and scale of such networks has brought with them increased interpretability problems.[8]

Basic principle

[edit]The central connectionist principle is that mental phenomena can be described by interconnected networks of simple and often uniform units. The form of the connections and the units can vary from model to model. For example, units in the network could represent neurons and the connections could represent synapses, as in the human brain. This principle has been seen as an alternative to GOFAI and the classical theories of mind based on symbolic computation, but the extent to which the two approaches are compatible has been the subject of much debate since their inception.[8]

Activation function

[edit]Internal states of any network change over time due to neurons sending a signal to a succeeding layer of neurons in the case of a feedforward network, or to a previous layer in the case of a recurrent network. Discovery of non-linear activation functions has enabled the second wave of connectionism.

Memory and learning

[edit]Neural networks follow two basic principles:

- Any mental state can be described as a n-dimensional vector of numeric activation values over neural units in a network.

- Memory and learning are created by modifying the 'weights' of the connections between neural units, generally represented as an n×m matrix. The weights are adjusted according to some learning rule or algorithm, such as Hebbian learning.[9]

Most of the variety among the models comes from:

- Interpretation of units: Units can be interpreted as neurons or groups of neurons.

- Definition of activation: Activation can be defined in a variety of ways. For example, in a Boltzmann machine, the activation is interpreted as the probability of generating an action potential spike, and is determined via a logistic function on the sum of the inputs to a unit.

- Learning algorithm: Different networks modify their connections differently. In general, any mathematically defined change in connection weights over time is referred to as the "learning algorithm".

Biological realism

[edit]Connectionist work in general does not need to be biologically realistic.[10][11][12][13][14][15][16] One area where connectionist models are thought to be biologically implausible is with respect to error-propagation networks that are needed to support learning,[17][18] but error propagation can explain some of the biologically-generated electrical activity seen at the scalp in event-related potentials such as the N400 and P600,[19] and this provides some biological support for one of the key assumptions of connectionist learning procedures. Many recurrent connectionist models also incorporate dynamical systems theory. Many researchers, such as the connectionist Paul Smolensky, have argued that connectionist models will evolve toward fully continuous, high-dimensional, non-linear, dynamic systems approaches.

Precursors

[edit]Precursors of the connectionist principles can be traced to early work in psychology, such as that of William James.[20] Psychological theories based on knowledge about the human brain were fashionable in the late 19th century. As early as 1869, the neurologist John Hughlings Jackson argued for multi-level, distributed systems. Following from this lead, Herbert Spencer's Principles of Psychology, 3rd edition (1872), and Sigmund Freud's Project for a Scientific Psychology (composed 1895) propounded connectionist or proto-connectionist theories. These tended to be speculative theories. But by the early 20th century, Edward Thorndike was writing about human learning that posited a connectionist type network.[21]

Hopfield networks had precursors in the Ising model due to Wilhelm Lenz (1920) and Ernst Ising (1925), though the Ising model conceived by them did not involve time. Monte Carlo simulations of Ising model required the advent of computers in the 1950s.[22]

The first wave

[edit]The first wave begun in 1943 with Warren Sturgis McCulloch and Walter Pitts both focusing on comprehending neural circuitry through a formal and mathematical approach. McCulloch and Pitts showed how neural systems could implement first-order logic: Their classic paper "A Logical Calculus of Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity" (1943) is important in this development here. They were influenced by the work of Nicolas Rashevsky in the 1930s and symbolic logic in the style of Principia Mathematica.[23][3]

Hebb contributed greatly to speculations about neural functioning, and proposed a learning principle, Hebbian learning. Lashley argued for distributed representations as a result of his failure to find anything like a localized engram in years of lesion experiments. Friedrich Hayek independently conceived the model, first in a brief unpublished manuscript in 1920,[24][25] then expanded into a book in 1952.[26]

The Perceptron machines were proposed and built by Frank Rosenblatt, who published the 1958 paper “The Perceptron: A Probabilistic Model For Information Storage and Organization in the Brain” in Psychological Review, while working at the Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory. He cited Hebb, Hayek, Uttley, and Ashby as main influences.

Another form of connectionist model was the relational network framework developed by the linguist Sydney Lamb in the 1960s.

The research group led by Widrow empirically searched for methods to train two-layered ADALINE networks (MADALINE), with limited success.[27][28]

A method to train multilayered perceptrons with arbitrary levels of trainable weights was published by Alexey Grigorevich Ivakhnenko and Valentin Lapa in 1965, called the Group Method of Data Handling. This method employs incremental layer by layer training based on regression analysis, where useless units in hidden layers are pruned with the help of a validation set.[29][30][31]

The first multilayered perceptrons trained by stochastic gradient descent[32] was published in 1967 by Shun'ichi Amari.[33] In computer experiments conducted by Amari's student Saito, a five layer MLP with two modifiable layers learned useful internal representations to classify non-linearily separable pattern classes.[30]

In 1972, Shun'ichi Amari produced an early example of self-organizing network.[34]

The neural network winter

[edit]There was some conflict among artificial intelligence researchers as to what neural networks are useful for. Around late 1960s, there was a widespread lull in research and publications on neural networks, "the neural network winter", which lasted through the 1970s, during which the field of artificial intelligence turned towards symbolic methods. The publication of Perceptrons (1969) is typically regarded as a catalyst of this event.[35][36]

The second wave

[edit]The second wave begun in the early 1980s. Some key publications included (John Hopfield, 1982)[37] which popularized Hopfield networks, the 1986 paper that popularized backpropagation,[38] and the 1987 two-volume book about the Parallel Distributed Processing (PDP) by James L. McClelland, David E. Rumelhart et al., which has introduced a couple of improvements to the simple perceptron idea, such as intermediate processors (known as "hidden layers" now) alongside input and output units and using sigmoid activation function instead of the old 'all-or-nothing' function.

Hopfield approached the field from the perspective of statistical mechanics, providing some early forms of mathematical rigor that increased the perceived respectability of the field.[3] Another important series of publications proved that neural networks are universal function approximators, which also provided some mathematical respectability.[39]

Some early popular demonstration projects appeared during this time. NETtalk (1987) learned to pronounce written English. It achieved popular success, appearing on the Today show.[40] TD-Gammon (1992) reached top human level in backgammon.[41]

Connectionism vs. computationalism debate

[edit]As connectionism became increasingly popular in the late 1980s, some researchers (including Jerry Fodor, Steven Pinker and others) reacted against it. They argued that connectionism, as then developing, threatened to obliterate what they saw as the progress being made in the fields of cognitive science and psychology by the classical approach of computationalism. Computationalism is a specific form of cognitivism that argues that mental activity is computational, that is, that the mind operates by performing purely formal operations on symbols, like a Turing machine. Some researchers argued that the trend in connectionism represented a reversion toward associationism and the abandonment of the idea of a language of thought, something they saw as mistaken. In contrast, those very tendencies made connectionism attractive for other researchers.

Connectionism and computationalism need not be at odds, but the debate in the late 1980s and early 1990s led to opposition between the two approaches. Throughout the debate, some researchers have argued that connectionism and computationalism are fully compatible, though full consensus on this issue has not been reached. Differences between the two approaches include the following:

- Computationalists posit symbolic models that are structurally similar to underlying brain structure, whereas connectionists engage in "low-level" modeling, trying to ensure that their models resemble neurological structures.

- Computationalists in general focus on the structure of explicit symbols (mental models) and syntactical rules for their internal manipulation, whereas connectionists focus on learning from environmental stimuli and storing this information in a form of connections between neurons.

- Computationalists believe that internal mental activity consists of manipulation of explicit symbols, whereas connectionists believe that the manipulation of explicit symbols provides a poor model of mental activity.

- Computationalists often posit domain specific symbolic sub-systems designed to support learning in specific areas of cognition (e.g., language, intentionality, number), whereas connectionists posit one or a small set of very general learning-mechanisms.

Despite these differences, some theorists have proposed that the connectionist architecture is simply the manner in which organic brains happen to implement the symbol-manipulation system. This is logically possible, as it is well known that connectionist models can implement symbol-manipulation systems of the kind used in computationalist models,[42] as indeed they must be able if they are to explain the human ability to perform symbol-manipulation tasks. Several cognitive models combining both symbol-manipulative and connectionist architectures have been proposed. Among them are Paul Smolensky's Integrated Connectionist/Symbolic Cognitive Architecture (ICS).[8][43] and Ron Sun's CLARION (cognitive architecture). But the debate rests on whether this symbol manipulation forms the foundation of cognition in general, so this is not a potential vindication of computationalism. Nonetheless, computational descriptions may be helpful high-level descriptions of cognition of logic, for example.

The debate was largely centred on logical arguments about whether connectionist networks could produce the syntactic structure observed in this sort of reasoning. This was later achieved although using fast-variable binding abilities outside of those standardly assumed in connectionist models.[42][44]

Part of the appeal of computational descriptions is that they are relatively easy to interpret, and thus may be seen as contributing to our understanding of particular mental processes, whereas connectionist models are in general more opaque, to the extent that they may be describable only in very general terms (such as specifying the learning algorithm, the number of units, etc.), or in unhelpfully low-level terms. In this sense, connectionist models may instantiate, and thereby provide evidence for, a broad theory of cognition (i.e., connectionism), without representing a helpful theory of the particular process that is being modelled. In this sense, the debate might be considered as to some extent reflecting a mere difference in the level of analysis in which particular theories are framed. Some researchers suggest that the analysis gap is the consequence of connectionist mechanisms giving rise to emergent phenomena that may be describable in computational terms.[45]

In the 2000s, the popularity of dynamical systems in philosophy of mind have added a new perspective on the debate;[46][47] some authors[which?] now argue that any split between connectionism and computationalism is more conclusively characterized as a split between computationalism and dynamical systems.

In 2014, Alex Graves and others from DeepMind published a series of papers describing a novel Deep Neural Network structure called the Neural Turing Machine[48] able to read symbols on a tape and store symbols in memory. Relational Networks, another Deep Network module published by DeepMind, are able to create object-like representations and manipulate them to answer complex questions. Relational Networks and Neural Turing Machines are further evidence that connectionism and computationalism need not be at odds.

Symbolism vs. connectionism debate

[edit]Smolensky's Subsymbolic Paradigm[49][50] has to meet the Fodor-Pylyshyn challenge[51][52][53][54] formulated by classical symbol theory for a convincing theory of cognition in modern connectionism. In order to be an adequate alternative theory of cognition, Smolensky's Subsymbolic Paradigm would have to explain the existence of systematicity or systematic relations in language cognition without the assumption that cognitive processes are causally sensitive to the classical constituent structure of mental representations. The subsymbolic paradigm, or connectionism in general, would thus have to explain the existence of systematicity and compositionality without relying on the mere implementation of a classical cognitive architecture. This challenge implies a dilemma: If the Subsymbolic Paradigm could contribute nothing to the systematicity and compositionality of mental representations, it would be insufficient as a basis for an alternative theory of cognition. However, if the Subsymbolic Paradigm's contribution to systematicity requires mental processes grounded in the classical constituent structure of mental representations, the theory of cognition it develops would be, at best, an implementation architecture of the classical model of symbol theory and thus not a genuine alternative (connectionist) theory of cognition.[55] The classical model of symbolism is characterized by (1) a combinatorial syntax and semantics of mental representations and (2) mental operations as structure-sensitive processes, based on the fundamental principle of syntactic and semantic constituent structure of mental representations as used in Fodor's "Language of Thought (LOT)".[56][57] This can be used to explain the following closely related properties of human cognition, namely its (1) productivity, (2) systematicity, (3) compositionality, and (4) inferential coherence.[58]

This challenge has been met in modern connectionism, for example, not only by Smolensky's "Integrated Connectionist/Symbolic (ICS) Cognitive Architecture",[59][60] but also by Werning and Maye's "Oscillatory Networks".[61][62][63] An overview of this is given for example by Bechtel & Abrahamsen,[64] Marcus[65] and Maurer.[66]

Recently, Heng Zhang and his colleagues have demonstrated that mainstream knowledge representation formalisms are, in fact, recursively isomorphic, provided they possess equivalent expressive power.[67] This finding implies that there is no fundamental distinction between using symbolic or connectionist knowledge representation formalisms for the realization of artificial general intelligence (AGI). Moreover, the existence of recursive isomorphisms suggests that different technical approaches can draw insights from one another.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy". iep.utm.edu. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- ^ McCulloch, Warren S.; Pitts, Walter (1943-12-01). "A logical calculus of the ideas immanent in nervous activity". The Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics. 5 (4): 115–133. doi:10.1007/BF02478259. ISSN 1522-9602.

- ^ a b c d e f Berkeley, Istvan S. N. (2019). "The Curious Case of Connectionism". Open Philosophy. 2019 (2): 190–205. doi:10.1515/opphil-2019-0018. S2CID 201061823.

- ^ Boden, Margaret (2006). Mind as Machine: A History of Cognitive Science. Oxford: Oxford U.P. p. 914. ISBN 978-0-262-63268-3.

- ^ Schneider, Walter (1987). "Connectionism: Is it a Paradigm Shift for Psychology?". Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 19: 73–83. doi:10.1515/opphil-2019-0018. S2CID 201061823.

- ^ Marcus, Gary F. (2001). The Algebraic Mind: Integrating Connectionism and Cognitive Science (Learning, Development, and Conceptual Change). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. pp. 27–28. ISBN 978-0-262-63268-3.

- ^ Smolensky, Paul (1999). "Grammar-based Connectionist Approaches to Language". Cognitive Science. 23 (4): 589–613. doi:10.1207/s15516709cog2304_9.

- ^ a b c Garson, James (27 November 2018). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University – via Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Novo, María-Luisa; Alsina, Ángel; Marbán, José-María; Berciano, Ainhoa (2017). "Connective Intelligence for Childhood Mathematics Education". Comunicar (in Spanish). 25 (52): 29–39. doi:10.3916/c52-2017-03. hdl:10272/14085. ISSN 1134-3478.

- ^ "Encephalos Journal". www.encephalos.gr. Retrieved 2018-02-20.

- ^ Wilson, Elizabeth A. (2016-02-04). Neural Geographies: Feminism and the Microstructure of Cognition. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-95876-5.

- ^ Di Paolo, E.A (1 January 2003). "Organismically-inspired robotics: homeostatic adaptation and teleology beyond the closed sensorimotor loop" (PDF). Dynamical Systems Approach to Embodiment and Sociality, Advanced Knowledge International. University of Sussex. S2CID 15349751. Retrieved 29 December 2023.

- ^ Zorzi, Marco; Testolin, Alberto; Stoianov, Ivilin P. (2013-08-20). "Modeling language and cognition with deep unsupervised learning: a tutorial overview". Frontiers in Psychology. 4: 515. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00515. ISSN 1664-1078. PMC 3747356. PMID 23970869.

- ^ Tieszen, R. (2011). "Analytic and Continental Philosophy, Science, and Global Philosophy". Comparative Philosophy. 2 (2): 4–22. doi:10.31979/2151-6014(2011).020206. Retrieved 29 December 2023.

- ^ Browne, A. (1997-01-01). Neural Network Perspectives on Cognition and Adaptive Robotics. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-7503-0455-9.

- ^ Pfeifer, R.; Schreter, Z.; Fogelman-Soulié, F.; Steels, L. (1989-08-23). Connectionism in Perspective. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-59876-9.

- ^ Crick, Francis (January 1989). "The recent excitement about neural networks". Nature. 337 (6203): 129–132. Bibcode:1989Natur.337..129C. doi:10.1038/337129a0. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 2911347. S2CID 5892527.

- ^ Rumelhart, David E.; Hinton, Geoffrey E.; Williams, Ronald J. (October 1986). "Learning representations by back-propagating errors". Nature. 323 (6088): 533–536. Bibcode:1986Natur.323..533R. doi:10.1038/323533a0. ISSN 1476-4687. S2CID 205001834.

- ^ Fitz, Hartmut; Chang, Franklin (2019-06-01). "Language ERPs reflect learning through prediction error propagation". Cognitive Psychology. 111: 15–52. doi:10.1016/j.cogpsych.2019.03.002. hdl:21.11116/0000-0003-474F-6. ISSN 0010-0285. PMID 30921626. S2CID 85501792.

- ^ Anderson, James A.; Rosenfeld, Edward (1989). "Chapter 1: (1890) William James Psychology (Brief Course)". Neurocomputing: Foundations of Research. A Bradford Book. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-262-51048-6.

- ^ Edward Thorndike (1931) Human Learning, page 122

- ^ Brush, Stephen G. (1967). "History of the Lenz-Ising Model". Reviews of Modern Physics. 39 (4): 883–893. Bibcode:1967RvMP...39..883B. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.39.883.

- ^ McCulloch, Warren S.; Pitts, Walter (1943-12-01). "A logical calculus of the ideas immanent in nervous activity". The Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics. 5 (4): 115–133. doi:10.1007/BF02478259. ISSN 1522-9602.

- ^ Hayek, Friedrich A. [1920] 1991. Beiträge zur Theorie der Entwicklung des Bewusstseins [Contributions to a theory of how consciousness develops]. Manuscript, translated by Grete Heinz.

- ^ Caldwell, Bruce (2004). "Some Reflections on F.A. Hayek's The Sensory Order". Journal of Bioeconomics. 6 (3): 239–254. doi:10.1007/s10818-004-5505-9. ISSN 1387-6996. S2CID 144437624.

- ^ Hayek, F. A. (2012-09-15). The Sensory Order: An Inquiry into the Foundations of Theoretical Psychology (1st ed.). The University of Chicago Press.

- ^ pp 124-129, Olazaran Rodriguez, Jose Miguel. A historical sociology of neural network research. PhD Dissertation. University of Edinburgh, 1991.

- ^ Widrow, B. (1962) Generalization and information storage in networks of ADALINE "neurons". In M. C. Yovits, G. T. Jacobi, & G. D. Goldstein (Ed.), Self-Organizing Svstems-1962 (pp. 435-461). Washington, DC: Spartan Books.

- ^ Ivakhnenko, A. G.; Grigorʹevich Lapa, Valentin (1967). Cybernetics and forecasting techniques. American Elsevier Pub. Co.

- ^ a b Schmidhuber, Jürgen (2022). "Annotated History of Modern AI and Deep Learning". arXiv:2212.11279 [cs.NE].

- ^ Ivakhnenko, A. G. (1973). Cybernetic Predicting Devices. CCM Information Corporation.

- ^ Robbins, H.; Monro, S. (1951). "A Stochastic Approximation Method". The Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 22 (3): 400. doi:10.1214/aoms/1177729586.

- ^ Amari, Shun'ichi (1967). "A theory of adaptive pattern classifier". IEEE Transactions. EC (16): 279–307.

- ^ Amari, S.-I. (November 1972). "Learning Patterns and Pattern Sequences by Self-Organizing Nets of Threshold Elements". IEEE Transactions on Computers. C-21 (11): 1197–1206. doi:10.1109/T-C.1972.223477. ISSN 0018-9340.

- ^ Olazaran, Mikel (1993-01-01), "A Sociological History of the Neural Network Controversy", in Yovits, Marshall C. (ed.), Advances in Computers Volume 37, vol. 37, Elsevier, pp. 335–425, doi:10.1016/S0065-2458(08)60408-8, ISBN 978-0-12-012137-3, retrieved 2024-08-07

- ^ Olazaran, Mikel (August 1996). "A Sociological Study of the Official History of the Perceptrons Controversy". Social Studies of Science. 26 (3): 611–659. doi:10.1177/030631296026003005. ISSN 0306-3127.

- ^ Hopfield, J J (April 1982). "Neural networks and physical systems with emergent collective computational abilities". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 79 (8): 2554–2558. Bibcode:1982PNAS...79.2554H. doi:10.1073/pnas.79.8.2554. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 346238. PMID 6953413.

- ^ Rumelhart, David E.; Hinton, Geoffrey E.; Williams, Ronald J. (October 1986). "Learning representations by back-propagating errors". Nature. 323 (6088): 533–536. Bibcode:1986Natur.323..533R. doi:10.1038/323533a0. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ Cybenko, G. (1989-12-01). "Approximation by superpositions of a sigmoidal function". Mathematics of Control, Signals and Systems. 2 (4): 303–314. Bibcode:1989MCSS....2..303C. doi:10.1007/BF02551274. ISSN 1435-568X.

- ^ Sejnowski, Terrence J. (2018). The deep learning revolution. Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England: The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-03803-4.

- ^ Sammut, Claude; Webb, Geoffrey I., eds. (2010), "TD-Gammon", Encyclopedia of Machine Learning, Boston, MA: Springer US, pp. 955–956, doi:10.1007/978-0-387-30164-8_813, ISBN 978-0-387-30164-8, retrieved 2023-12-25

- ^ a b Chang, Franklin (2002). "Symbolically speaking: a connectionist model of sentence production". Cognitive Science. 26 (5): 609–651. doi:10.1207/s15516709cog2605_3. ISSN 1551-6709.

- ^ Smolensky, Paul (1990). "Tensor Product Variable Binding and the Representation of Symbolic Structures in Connectionist Systems" (PDF). Artificial Intelligence. 46 (1–2): 159–216. doi:10.1016/0004-3702(90)90007-M.

- ^ Shastri, Lokendra; Ajjanagadde, Venkat (September 1993). "From simple associations to systematic reasoning: A connectionist representation of rules, variables and dynamic bindings using temporal synchrony". Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 16 (3): 417–451. doi:10.1017/S0140525X00030910. ISSN 1469-1825. S2CID 14973656.

- ^ Ellis, Nick C. (1998). "Emergentism, Connectionism and Language Learning" (PDF). Language Learning. 48 (4): 631–664. doi:10.1111/0023-8333.00063.

- ^ Van Gelder, Tim (1998), "The dynamical hypothesis in cognitive science", Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 21 (5): 615–28, discussion 629–65, doi:10.1017/S0140525X98001733, PMID 10097022, retrieved 28 May 2022

- ^ Beer, Randall D. (March 2000). "Dynamical approaches to cognitive science". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 4 (3): 91–99. doi:10.1016/s1364-6613(99)01440-0. ISSN 1364-6613. PMID 10689343. S2CID 16515284.

- ^ Graves, Alex (2014). "Neural Turing Machines". arXiv:1410.5401 [cs.NE].

- ^ P. Smolensky: On the proper treatment of connectionism. In: Behavioral and Brain Sciences. Band 11, 1988, S. 1-74.

- ^ P. Smolensky: The constituent structure of connectionist mental states: a reply to Fodor and Pylyshyn. In: T. Horgan, J. Tienson (Hrsg.): Spindel Conference 1987: Connectionism and the Philosophy of Mind. The Southern Journal of Philosophy. Special Issue on Connectionism and the Foundations of Cognitive Science. Supplement. Band 26, 1988, S. 137-161.

- ^ J.A. Fodor, Z.W. Pylyshyn: Connectionism and cognitive architecture: a critical analysis. Cognition. Band 28, 1988, S. 12-13, 33-50.

- ^ J.A. Fodor, B. McLaughlin: Connectionism and the problem of systematicity: why Smolensky's solution doesn't work. Cognition. Band 35, 1990, S. 183-184.

- ^ B. McLaughlin: The connectionism/classicism battle to win souls. Philosophical Studies, Band 71, 1993, S. 171-172.

- ^ B. McLaughlin: Can an ICS architecture meet the systematicity and productivity challenges? In: P. Calvo, J. Symons (Hrsg.): The Architecture of Cognition. Rethinking Fodor and Pylyshyn's Systematicity Challenge. MIT Press, Cambridge/MA, London, 2014, S. 31-76.

- ^ J.A. Fodor, B. McLaughlin: Connectionism and the problem of systematicity: Why Smolensky's solution doesn't work. Cognition. Band 35, 1990, S. 183-184.

- ^ J.A. Fodor: The language of thought. Harvester Press, Sussex, 1976, ISBN 0-85527-309-7.

- ^ J.A. Fodor: LOT 2: The language of thought revisited. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 2008, ISBN 0-19-954877-3.

- ^ J.A. Fodor, Z.W. Pylyshyn (1988), S. 33-48.

- ^ P. Smolenky: Reply: Constituent structure and explanation in an integrated connectionist / symbolic cognitive architecture. In: C. MacDonald, G. MacDonald (Hrsg.): Connectionism: Debates on psychological explanation. Blackwell Publishers. Oxford/UK, Cambridge/MA. Vol. 2, 1995, S. 224, 236-239, 242-244, 250-252, 282.

- ^ P. Smolensky, G. Legendre: The Harmonic Mind: From Neural Computation to Optimality-Theoretic Grammar. Vol. 1: Cognitive Architecture. A Bradford Book, The MIT Press, Cambridge, London, 2006a, ISBN 0-262-19526-7, S. 65-67, 69-71, 74-75, 154-155, 159-202, 209-210, 235-267, 271-342, 513.

- ^ M. Werning: Neuronal synchronization, covariation, and compositional representation. In: M. Werning, E. Machery, G. Schurz (Hrsg.): The compositionality of meaning and content. Vol. II: Applications to linguistics, psychology and neuroscience. Ontos Verlag, 2005, S. 283-312.

- ^ M. Werning: Non-symbolic compositional representation and its neuronal foundation: towards an emulative semantics. In: M. Werning, W. Hinzen, E. Machery (Hrsg.): The Oxford Handbook of Compositionality. Oxford University Press, 2012, S. 633-654.

- ^ A. Maye und M. Werning: Neuronal synchronization: from dynamics feature binding to compositional representations. Chaos and Complexity Letters, Band 2, S. 315-325.

- ^ Bechtel, W., Abrahamsen, A.A. Connectionism and the Mind: Parallel Processing, Dynamics, and Evolution in Networks. 2nd Edition. Blackwell Publishers, Oxford. 2002

- ^ G.F. Marcus: The algebraic mind. Integrating connectionism and cognitive science. Bradford Book, The MIT Press, Cambridge, 2001, ISBN 0-262-13379-2.

- ^ H. Maurer: Cognitive science: Integrative synchronization mechanisms in cognitive neuroarchitectures of the modern connectionism. CRC Press, Boca Raton/FL, 2021, ISBN 978-1-351-04352-6. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781351043526

- ^ Zhang, Heng; Jiang, Guifei; Quan, Donghui (2025-04-11). "A Theory of Formalisms for Representing Knowledge". Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. 39 (14): 15257–15264. arXiv:2412.11855. doi:10.1609/aaai.v39i14.33674. ISSN 2374-3468.

References

[edit]- Feldman, Jerome and Ballard, Dana. Connectionist models and their properties(1982). Cognitive Science. V6, Iissue 3 , pp205-254.

- Rumelhart, D.E., J.L. McClelland and the PDP Research Group (1986). Parallel Distributed Processing: Explorations in the Microstructure of Cognition. Volume 1: Foundations, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, ISBN 978-0-262-68053-0

- McClelland, J.L., D.E. Rumelhart and the PDP Research Group (1986). Parallel Distributed Processing: Explorations in the Microstructure of Cognition. Volume 2: Psychological and Biological Models, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, ISBN 978-0-262-63110-5

- Pinker, Steven and Mehler, Jacques (1988). Connections and Symbols, Cambridge MA: MIT Press, ISBN 978-0-262-66064-8

- Jeffrey L. Elman, Elizabeth A. Bates, Mark H. Johnson, Annette Karmiloff-Smith, Domenico Parisi, Kim Plunkett (1996). Rethinking Innateness: A connectionist perspective on development, Cambridge MA: MIT Press, ISBN 978-0-262-55030-7

- Marcus, Gary F. (2001). The Algebraic Mind: Integrating Connectionism and Cognitive Science (Learning, Development, and Conceptual Change), Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, ISBN 978-0-262-63268-3

- David A. Medler (1998). "A Brief History of Connectionism" (PDF). Neural Computing Surveys. 1: 61–101.

- Maurer, Harald (2021). Cognitive Science: Integrative Synchronization Mechanisms in Cognitive Neuroarchitectures of the Modern Connectionism, Boca Raton/FL: CRC Press, https://doi.org/10.1201/9781351043526, ISBN 978-1-351-04352-6

External links

[edit]- Dictionary of Philosophy of Mind entry on connectionism

- Garson, James. "Connectionism". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- A demonstration of Interactive Activation and Competition Networks Archived 2015-07-03 at the Wayback Machine

- Fieser, James; Dowden, Bradley (eds.). "Connectionism". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. ISSN 2161-0002. OCLC 37741658.

- Critique of connectionism

Connectionism

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Core Principles

Connectionism is a computational approach to modeling cognition that employs artificial neural networks (ANNs), consisting of interconnected nodes or units linked by adjustable weighted connections. These networks simulate cognitive processes by propagating activation signals through the connections, where the weights determine the strength and direction of influence between units, enabling the representation and transformation of information in a manner inspired by neural structures. This paradigm contrasts with symbolic approaches by emphasizing subsymbolic processing, where cognitive states emerge from the collective activity of many simple elements rather than rule-based manipulations of discrete symbols.[4] At the heart of connectionism lies the parallel distributed processing (PDP) framework, which describes cognition as arising from the simultaneous, interactive computations across a network of units. In PDP models, knowledge is stored not in isolated locations but in a distributed fashion across the connection weights, allowing representations to overlap and share resources for efficiency and flexibility. For instance, concepts or patterns are encoded such that activating part of a representation can recruit related knowledge through the weighted links, facilitating processes like generalization and associative recall without explicit programming. This distributed representation underpins the framework's ability to handle noisy or incomplete inputs gracefully, as seen in models where partial patterns activate complete stored information.[4] A fundamental principle of connectionism is emergent behavior, whereby complex cognitive capabilities—such as perception, learning, and decision-making—arise from local interactions governed by simple rules, without requiring a central executive or predefined algorithms. Units operate in parallel, adjusting activations based on incoming signals and propagating outputs, leading to network-level phenomena like pattern completion or error-driven adaptation that mimic human-like intelligence. This emergence highlights how high-level functions can self-organize from low-level dynamics, providing a unified account of diverse cognitive tasks through scalable, interactive architectures.[4] The term "connectionism" originated in early psychology with Edward Thorndike's theory of learning as stimulus-response bonds but gained renewed prominence in the 1980s through the PDP framework, revitalizing it as a cornerstone of modern cognitive science.[5][4]Activation Functions and Signal Propagation

In connectionist networks, processing units, often called nodes or neurons, function as the basic computational elements. Each unit receives inputs from other connected units, multiplies them by corresponding weights to compute a linear combination, adds a bias term, and applies an activation function to generate an output signal that can be transmitted to subsequent units. This mechanism allows individual units to transform and filter incoming information in a distributed manner across the network.[6] Activation functions determine the output of a unit based on its net input, introducing non-linearity essential for modeling complex mappings beyond linear transformations. The step function, an early form used in threshold-based models, outputs a binary value of 1 if the net input exceeds a threshold (typically 0) and 0 otherwise, providing a simple on-off response but lacking differentiability for gradient computations. The sigmoid function, defined mathematically as produces an S-shaped curve that bounds outputs between 0 and 1, ensuring smooth transitions and differentiability, which facilitates error propagation in multi-layer networks, though it can lead to vanishing gradients for large |x| due to saturation.[7] More recently, the rectified linear unit (ReLU), expressed as applies a piecewise linear transformation that zeros out negative inputs while passing positive ones unchanged, promoting sparsity, computational efficiency, and faster convergence in deep architectures by avoiding saturation for positive values, despite being non-differentiable at x=0.[8] These functions collectively enable non-linear decision boundaries, with properties like boundedness (sigmoid) or unboundedness (ReLU) influencing training dynamics and representational capacity.[6] Signal propagation, or forward pass, occurs by sequentially computing unit outputs across layers or connections. For a given unit, the net input is calculated as the weighted sum where are the weights from input units with activations and is the bias, followed by applying the activation function to yield the unit's output, which then serves as input to downstream units.[7] In feedforward networks, this process flows unidirectionally from input to output layers, enabling pattern recognition through layered transformations. Recurrent topologies, by contrast, permit feedback loops where outputs recirculate as inputs, supporting sequential or dynamic processing.[6] Weights play a pivotal role in modulating signal strength and directionality, with positive values amplifying (exciting) incoming signals and negative values suppressing (inhibiting) them, thus shaping the network's overall computation.[6] The arrangement of weights within the network topology—feedforward for acyclic processing or recurrent for cyclical interactions—dictates how signals propagate, influencing the model's ability to capture hierarchical features or temporal dependencies. During learning, these weights are adjusted via algorithms like backpropagation to refine signal transmission for better task performance.[7]Learning and Memory Mechanisms

In connectionist models, learning occurs through the adjustment of connection weights between units, enabling networks to acquire knowledge from data and adapt to patterns. Supervised learning, a cornerstone mechanism, involves error-driven updates where the network minimizes discrepancies between predicted and target outputs. The backpropagation algorithm, introduced by Rumelhart, Hinton, and Williams, computes gradients of the error with respect to weights by propagating errors backward through the network layers.[9] This process updates weights according to the rule , where is the learning rate, represents the error derivative at the unit, and is the input from the presynaptic unit; such adjustments allow multilayer networks to learn complex representations efficiently.[9] Unsupervised learning, in contrast, discovers structure in data without labeled targets, relying on intrinsic patterns to modify weights. The Hebbian learning rule, formulated by Hebb, posits that "cells that fire together wire together," strengthening connections between co-active units to form associations.[10] Mathematically, this is expressed as , where and are the activations of presynaptic and postsynaptic units, respectively, promoting synaptic potentiation based on correlated activity.[10] Competitive learning extends this through mechanisms like self-organizing maps (SOMs), developed by Kohonen, where units compete to represent input clusters, adjusting weights to preserve topological relationships in the data.[11] In SOMs, the winning unit and its neighbors update toward the input vector, enabling dimensionality reduction and feature extraction without supervision.[11] Memory in connectionist systems is stored as distributed patterns across weights rather than localized sites, facilitating robust recall. Attractor networks, exemplified by the Hopfield model, function as content-addressable memory by settling into stable states that represent stored patterns. In these recurrent networks, partial or noisy inputs evolve dynamically toward attractor basins via energy minimization, allowing associative completion; for instance, a fragment of a memorized image can reconstruct the full pattern through iterative updates. This distributed encoding enhances fault tolerance, as damage to individual connections degrades recall gradually rather than catastrophically. To achieve effective generalization—the ability to perform well on unseen data—connectionist models address overfitting, where networks memorize training examples at the expense of broader applicability. Regularization techniques mitigate this by constraining model complexity during training. Dropout, proposed by Srivastava et al., randomly deactivates a fraction of units (typically 20-50%) in each forward pass, preventing co-adaptation and effectively integrating an ensemble of thinner networks.[12] This simple method has demonstrably improved performance on tasks like image classification, for example, reducing the error rate from 1.6% to 1.25% on the MNIST dataset without additional computational overhead.[12] Such approaches ensure that learned representations capture underlying data invariances rather than noise.Biological Plausibility

Connectionist models draw a direct analogy between their computational units and biological neurons, with connection weights representing the strengths of synaptic connections between neurons. This mapping posits that units integrate incoming signals and propagate outputs based on activation thresholds, mirroring how neurons sum excitatory and inhibitory postsynaptic potentials to generate action potentials. A foundational principle underlying this correspondence is Hebbian learning, which states that "neurons that fire together wire together," leading to strengthened synapses through repeated coincident pre- and postsynaptic activity.[13] This rule finds empirical support in long-term potentiation (LTP), a persistent strengthening of synapses observed in hippocampal slices following high-frequency stimulation, providing a neurophysiological basis for weight updates in connectionist learning algorithms. While connectionist units analogize biological neurons as computational functions that receive inputs via dendrites and synapses, perform internal processing such as signal integration and thresholds, and produce outputs as action potentials along axons, the composition of these transformations in neural networks resembles function application in lambda calculus. However, lambda calculus operates as a pure, stateless, side-effect-free, and timeless formal system, which contrasts with the brain's stateful, dynamical, noisy, analog or mixed-signal, and impure nature.[14][1] Neuroscience evidence bolsters the biological grounding of early connectionist architectures, particularly through the discovery of oriented receptive fields in the visual cortex. Hubel and Wiesel's experiments on cats revealed simple and complex cells that respond selectively to edge orientations and movement directions, forming hierarchical feature detectors.[15] These findings directly influenced the design of multilayer networks, such as Fukushima's neocognitron, which incorporates cascaded layers of cells with progressively complex receptive fields to achieve shift-invariant pattern recognition, echoing the cortical hierarchy. Despite these alignments, traditional connectionist models exhibit significant limitations in biological fidelity, primarily by employing continuous rate-based activations that overlook the discrete, timing-sensitive nature of neural signaling. For instance, they neglect spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP), where the direction and magnitude of synaptic changes depend on the precise millisecond-scale order of pre- and postsynaptic spikes, as demonstrated in cultured hippocampal neurons.[16] Additionally, these models typically ignore neuromodulation, the process by which transmitters like dopamine or serotonin dynamically alter synaptic efficacy and plasticity rules across neural circuits, enabling context-dependent learning that is absent in standard backpropagation-based training.[17] To enhance biological realism, spiking neural networks (SNNs) extend connectionism by simulating discrete action potentials rather than continuous rates, incorporating temporal dynamics more akin to real neurons. A canonical example is the leaky integrate-and-fire (LIF) model, where the membrane potential evolves discretely according to: where is the leak factor (e.g., with the membrane time constant), with a spike emitted and reset when exceeds a threshold, followed by a refractory period; here, represents (scaled) input current. This formulation captures subthreshold integration and leakage, aligning closely with biophysical properties observed in cortical pyramidal cells.[18] SNNs thus bridge the gap toward more plausible simulations of brain-like computation, though they remain computationally intensive compared to rate-based predecessors.Historical Development

Early Precursors

The roots of connectionism trace back to ancient philosophical ideas of associationism, which posited that mental processes arise from the linking of ideas through principles such as contiguity and resemblance. Aristotle, in his work On Memory and Reminiscence, outlined early laws of association, suggesting that recollections are triggered by similarity (resemblance between ideas), contrast (opposition between ideas), or contiguity (proximity in time or space between experiences), laying a foundational framework for understanding how discrete mental elements connect to form coherent thought.[19] This perspective influenced later empiricists, notably John Locke in his Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690), who formalized the "association of ideas" as a mechanism where simple ideas combine into complex ones based on repeated experiences of contiguity or similarity, emphasizing the mind's passive role in forming connections without innate structures.[20] Locke's ideas shifted focus toward sensory-derived associations, prefiguring connectionist views of distributed mental representations over centralized symbols. In the 19th century, physiological psychology advanced these notions by linking associations to neural mechanisms, particularly through William James's Principles of Psychology (1890). James described the brain's "plasticity" as enabling the formation of neural pathways through habit, where repeated co-activations strengthen connections, akin to assembling neural groups for efficient processing.[21] He emphasized principles of neural assembly, wherein groups of neurons integrate to represent ideas or actions, and inhibition, where competing neural tendencies are suppressed to allow focused activity, as seen in his discussion of how the cerebral hemispheres check lower reflexes and select among impulses.[21] These concepts bridged philosophy and biology, portraying the mind as an emergent property of interconnected neural elements rather than isolated faculties.[21] The early 20th century saw further groundwork in cybernetics, which introduced feedback and systemic views of information processing in biological and mechanical systems. Norbert Wiener's Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine (1948) conceptualized nervous systems as feedback loops regulating behavior through circular causal processes, influencing connectionist ideas of adaptive networks.[22] Complementing this, Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts's seminal paper "A Logical Calculus of the Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity" (1943) modeled neurons as threshold logic gates capable of computing any logical function via interconnected nets, demonstrating how simple binary units could simulate complex mental operations without symbolic mediation.[23] However, these early logical models lacked mechanisms for learning or adaptation, treating networks as fixed structures rather than modifiable systems, a limitation that hindered their immediate application to dynamic cognition.[23] A key biological foundation was laid by Donald Hebb in his 1949 book The Organization of Behavior, proposing that the strength of neural connections increases when presynaptic and postsynaptic neurons fire simultaneously, providing the first learning rule for connectionist networks.[2]First Wave (1940s-1960s)

The First Wave of connectionism, spanning the 1940s to 1960s, emerged amid growing optimism in artificial intelligence following the 1956 Dartmouth Conference, where researchers envisioned neural network-inspired systems as a viable path to machine intelligence capable of learning from data. This period marked the transition from theoretical biological inspirations to practical computational models, with early successes in simple pattern recognition fueling expectations that such networks could mimic brain-like processing for complex tasks. A seminal contribution was Frank Rosenblatt's Perceptron, introduced in 1958 as a single-layer artificial neuron for binary classification tasks. The model processes input vectors through weighted connections to produce an output via a threshold activation, enabling it to learn linear decision boundaries from examples. Training occurs via a supervised learning rule that adjusts weights iteratively to minimize classification errors:where are the weights, is the learning rate, is the target output, is the model's output, and is the input vector. Rosenblatt demonstrated the Perceptron's ability to recognize patterns in noisy data, such as handwritten digits, positioning it as a foundational tool for adaptive computation.[24] Building on this, Bernard Widrow and Marcian Hoff developed the ADALINE (Adaptive Linear Neuron) in 1960, applying similar principles to pattern recognition in signal processing. Unlike the Perceptron, which updates weights only on errors, ADALINE employed the least mean squares algorithm to continuously adjust weights based on the difference between predicted and actual outputs, improving convergence for linear problems. This model excelled in applications like adaptive filtering for noise cancellation and early speech recognition, demonstrating practical utility in engineering contexts.[25] However, enthusiasm waned with the 1969 publication of Perceptrons by Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert, which rigorously analyzed the limitations of single-layer networks. The authors proved that Perceptrons and similar models cannot solve non-linearly separable problems, such as the XOR function, due to their reliance on linear separability—any decision boundary must be a hyperplane, precluding representations of exclusive-or logic. This mathematical critique highlighted fundamental constraints, tempering early optimism and shifting focus away from connectionist approaches.[26]