Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Contour integration

View on Wikipedia| Part of a series of articles about |

| Calculus |

|---|

In the mathematical field of complex analysis, contour integration is a method of evaluating certain integrals along paths in the complex plane.[1][2][3]

Contour integration is closely related to the calculus of residues,[4] a method of complex analysis.

One use for contour integrals is the evaluation of integrals along the real line that are not readily found by using only real variable methods. It also has various applications in physics.[5]

Contour integration methods include:

- direct integration of a complex-valued function along a curve in the complex plane

- application of the Cauchy integral formula

- application of the residue theorem

One method can be used, or a combination of these methods, or various limiting processes, for the purpose of finding these integrals or sums.

Curves in the complex plane

[edit]In complex analysis, a contour is a type of curve in the complex plane. In contour integration, contours provide a precise definition of the curves on which an integral may be suitably defined. A curve in the complex plane is defined as a continuous function from a closed interval of the real line to the complex plane: .

This definition of a curve coincides with the intuitive notion of a curve, but includes a parametrization by a continuous function from a closed interval. This more precise definition allows us to consider what properties a curve must have for it to be useful for integration. In the following subsections we narrow down the set of curves that we can integrate to include only those that can be built up out of a finite number of continuous curves that can be given a direction. Moreover, we will restrict the "pieces" from crossing over themselves, and we require that each piece have a finite (non-vanishing) continuous derivative. These requirements correspond to requiring that we consider only curves that can be traced, such as by a pen, in a sequence of even, steady strokes, which stop only to start a new piece of the curve, all without picking up the pen.[6]

Directed smooth curves

[edit]Contours are often defined in terms of directed smooth curves.[6] These provide a precise definition of a "piece" of a smooth curve, of which a contour is made.

A smooth curve is a curve with a non-vanishing, continuous derivative such that each point is traversed only once (z is one-to-one), with the possible exception of a curve such that the endpoints match (). In the case where the endpoints match, the curve is called closed, and the function is required to be one-to-one everywhere else and the derivative must be continuous at the identified point (). A smooth curve that is not closed is often referred to as a smooth arc.[6]

The parametrization of a curve provides a natural ordering of points on the curve: comes before if . This leads to the notion of a directed smooth curve. It is most useful to consider curves independent of the specific parametrization. This can be done by considering equivalence classes of smooth curves with the same direction. A directed smooth curve can then be defined as an ordered set of points in the complex plane that is the image of some smooth curve in their natural order (according to the parametrization). Note that not all orderings of the points are the natural ordering of a smooth curve. In fact, a given smooth curve has only two such orderings. Also, a single closed curve can have any point as its endpoint, while a smooth arc has only two choices for its endpoints.

Contours

[edit]Contours are the class of curves on which we define contour integration. A contour is a directed curve which is made up of a finite sequence of directed smooth curves whose endpoints are matched to give a single direction. This requires that the sequence of curves be such that the terminal point of coincides with the initial point of for all such that . This includes all directed smooth curves. Also, a single point in the complex plane is considered a contour. The symbol is often used to denote the piecing of curves together to form a new curve. Thus we could write a contour that is made up of curves as

Contour integrals

[edit]The contour integral of a complex function is a generalization of the integral for real-valued functions. For continuous functions in the complex plane, the contour integral can be defined in analogy to the line integral by first defining the integral along a directed smooth curve in terms of an integral over a real valued parameter. A more general definition can be given in terms of partitions of the contour in analogy with the partition of an interval and the Riemann integral. In both cases the integral over a contour is defined as the sum of the integrals over the directed smooth curves that make up the contour.

For continuous functions

[edit]To define the contour integral in this way one must first consider the integral, over a real variable, of a complex-valued function. Let be a complex-valued function of a real variable, . The real and imaginary parts of are often denoted as and , respectively, so that Then the integral of the complex-valued function over the interval is given by

Now, to define the contour integral, let be a continuous function on the directed smooth curve . Let be any parametrization of that is consistent with its order (direction). Then the integral along is denoted and is given by[6]

This definition is well defined. That is, the result is independent of the parametrization chosen.[6] In the case where the real integral on the right side does not exist the integral along is said not to exist.

As a generalization of the Riemann integral

[edit]The generalization of the Riemann integral to functions of a complex variable is done in complete analogy to its definition for functions from the real numbers. The partition of a directed smooth curve is defined as a finite, ordered set of points on . The integral over the curve is the limit of finite sums of function values, taken at the points on the partition, in the limit that the maximum distance between any two successive points on the partition (in the two-dimensional complex plane), also known as the mesh, goes to zero.

Direct methods

[edit]Direct methods involve the calculation of the integral through methods similar to those in calculating line integrals in multivariate calculus. This means that we use the following method:

- parametrizing the contour

- The contour is parametrized by a differentiable complex-valued function of real variables, or the contour is broken up into pieces and parametrized separately.

- substitution of the parametrization into the integrand

- Substituting the parametrization into the integrand transforms the integral into an integral of one real variable.

- direct evaluation

- The integral is evaluated in a method akin to a real-variable integral.

Example

[edit]A fundamental result in complex analysis is that the contour integral of 1/z is 2πi, where the path of the contour is taken to be the unit circle traversed counterclockwise (or any positively oriented Jordan curve about 0). In the case of the unit circle there is a direct method to evaluate the integral

In evaluating this integral, use the unit circle |z| = 1 as a contour, parametrized by z(t) = eit, with t ∈ [0, 2π], then dz/dt = ieit and

which is the value of the integral. This result only applies to the case in which z is raised to power of -1. If the power is not equal to -1, then the result will always be zero.

Applications of integral theorems

[edit]Applications of integral theorems are also often used to evaluate the contour integral along a contour, which means that the real-valued integral is calculated simultaneously along with calculating the contour integral.

Integral theorems such as the Cauchy integral formula or residue theorem are generally used in the following method:

- a specific contour is chosen:

- The contour is chosen so that the contour follows the part of the complex plane that describes the real-valued integral, and also encloses singularities of the integrand so application of the Cauchy integral formula or residue theorem is possible

- application of Cauchy's integral theorem

- The integral is reduced to only an integration around a small circle about each pole.

- application of the Cauchy integral formula or residue theorem

- Application of these integral formulae gives us a value for the integral around the whole of the contour.

- division of the contour into a contour along the real part and imaginary part

- The whole of the contour can be divided into the contour that follows the part of the complex plane that describes the real-valued integral as chosen before (call it R), and the integral that crosses the complex plane (call it I). The integral over the whole of the contour is the sum of the integral over each of these contours.

- demonstration that the integral that crosses the complex plane plays no part in the sum

- If the integral I can be shown to be zero, or if the real-valued integral that is sought is improper, then if we demonstrate that the integral I as described above tends to 0, the integral along R will tend to the integral around the contour R + I.

- conclusion

- If we can show the above step, then we can directly calculate R, the real-valued integral.

Example 1

[edit]Consider the integral

To evaluate this integral, we look at the complex-valued function

which has singularities at i and −i. We choose a contour that will enclose the real-valued integral, here a semicircle with boundary diameter on the real line (going from, say, −a to a) will be convenient. Call this contour C.

There are two ways of proceeding, using the Cauchy integral formula or by the method of residues:

Using the Cauchy integral formula

[edit]Note that: thus

Furthermore, observe that

Since the only singularity in the contour is the one at i, then we can write

which puts the function in the form for direct application of the formula. Then, by using Cauchy's integral formula,

We take the first derivative, in the above steps, because the pole is a second-order pole. That is, (z − i) is taken to the second power, so we employ the first derivative of f(z). If it were (z − i) taken to the third power, we would use the second derivative and divide by 2!, etc. The case of (z − i) to the first power corresponds to a zero order derivative—just f(z) itself.

We need to show that the integral over the arc of the semicircle tends to zero as a → ∞, using the estimation lemma

where M is an upper bound on |f(z)| along the arc and L the length of the arc. Now, So

Using the method of residues

[edit]Consider the Laurent series of f(z) about i, the only singularity we need to consider. We then have

(See the sample Laurent calculation from Laurent series for the derivation of this series.)

It is clear by inspection that the residue is −i/4, so, by the residue theorem, we have

Thus we get the same result as before.

Contour note

[edit]As an aside, a question can arise whether we do not take the semicircle to include the other singularity, enclosing −i. To have the integral along the real axis moving in the correct direction, the contour must travel clockwise, i.e., in a negative direction, reversing the sign of the integral overall.

This does not affect the use of the method of residues by series.

Example 2 – Cauchy distribution

[edit]The integral

(which arises in probability theory as a scalar multiple of the characteristic function of the Cauchy distribution) resists the techniques of elementary calculus. We will evaluate it by expressing it as a limit of contour integrals along the contour C that goes along the real line from −a to a and then counterclockwise along a semicircle centered at 0 from a to −a. Take a to be greater than 1, so that the imaginary unit i is enclosed within the curve. The contour integral is

Since eitz is an entire function (having no singularities at any point in the complex plane), this function has singularities only where the denominator z2 + 1 is zero. Since z2 + 1 = (z + i)(z − i), that happens only where z = i or z = −i. Only one of those points is in the region bounded by this contour. The residue of f(z) at z = i is

According to the residue theorem, then, we have

The contour C may be split into a "straight" part and a curved arc, so that and thus

According to Jordan's lemma, if t > 0 then

Therefore, if t > 0 then

A similar argument with an arc that winds around −i rather than i shows that if t < 0 then and finally we have this:

(If t = 0 then the integral yields immediately to real-valued calculus methods and its value is π.)

Example 3 – trigonometric integrals

[edit]Certain substitutions can be made to integrals involving trigonometric functions, so the integral is transformed into a rational function of a complex variable and then the above methods can be used in order to evaluate the integral.

As an example, consider

We seek to make a substitution of z = eit. Now, recall and

Taking C to be the unit circle, we substitute to get:

The singularities to be considered are at Let C1 be a small circle about and C2 be a small circle about Then we arrive at the following:

Example 3a – trigonometric integrals, the general procedure

[edit]The above method may be applied to all integrals of the type

where P and Q are polynomials, i.e. a rational function in trigonometric terms is being integrated. Note that the bounds of integration may as well be π and −π, as in the previous example, or any other pair of endpoints 2π apart.

The trick is to use the substitution z = eit where dz = ieit dt and hence

This substitution maps the interval [0, 2π] to the unit circle. Furthermore, and so that a rational function f(z) in z results from the substitution, and the integral becomes which is in turn computed by summing the residues of f(z)1/iz inside the unit circle.

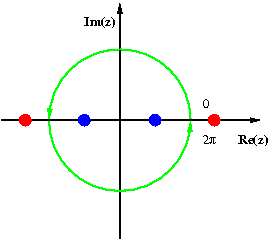

The image at right illustrates this for which we now compute. The first step is to recognize that

The substitution yields

The poles of this function are at 1 ± √2 and −1 ± √2. Of these, 1 + √2 and −1 − √2 are outside the unit circle (shown in red, not to scale), whereas 1 − √2 and −1 + √2 are inside the unit circle (shown in blue). The corresponding residues are both equal to −i√2/16, so that the value of the integral is

Example 4 – branch cuts

[edit]Consider the real integral

We can begin by formulating the complex integral

We can use the Cauchy integral formula or residue theorem again to obtain the relevant residues. However, the important thing to note is that z1/2 = e(Log z)/2, so z1/2 has a branch cut. This affects our choice of the contour C. Normally the logarithm branch cut is defined as the negative real axis, however, this makes the calculation of the integral slightly more complicated, so we define it to be the positive real axis.

Then, we use the so-called keyhole contour, which consists of a small circle about the origin of radius ε say, extending to a line segment parallel and close to the positive real axis but not touching it, to an almost full circle, returning to a line segment parallel, close, and below the positive real axis in the negative sense, returning to the small circle in the middle.

Note that z = −2 and z = −4 are inside the big circle. These are the two remaining poles, derivable by factoring the denominator of the integrand. The branch point at z = 0 was avoided by detouring around the origin.

Let γ be the small circle of radius ε, Γ the larger, with radius R, then

It can be shown that the integrals over Γ and γ both tend to zero as ε → 0 and R → ∞, by an estimation argument above, that leaves two terms. Now since z1/2 = e(Log z)/2, on the contour outside the branch cut, we have gained 2π in argument along γ. (By Euler's identity, eiπ represents the unit vector, which therefore has π as its log. This π is what is meant by the argument of z. The coefficient of 1/2 forces us to use 2π.) So

Therefore:

By using the residue theorem or the Cauchy integral formula (first employing the partial fractions method to derive a sum of two simple contour integrals) one obtains

Example 5 – the square of the logarithm

[edit]

This section treats a type of integral of which is an example.

To calculate this integral, one uses the function and the branch of the logarithm corresponding to −π < arg z ≤ π.

We will calculate the integral of f(z) along the keyhole contour shown at right. As it turns out this integral is a multiple of the initial integral that we wish to calculate and by the Cauchy residue theorem we have

Let R be the radius of the large circle, and r the radius of the small one. We will denote the upper line by M, and the lower line by N. As before we take the limit when R → ∞ and r → 0. The contributions from the two circles vanish. For example, one has the following upper bound with the ML lemma:

In order to compute the contributions of M and N we set z = −x + iε on M and z = −x − iε on N, with 0 < x < ∞:

which gives

Example 6 – logarithms and the residue at infinity

[edit]

We seek to evaluate

This requires a close study of

We will construct f(z) so that it has a branch cut on [0, 3], shown in red in the diagram. To do this, we choose two branches of the logarithm, setting and

The cut of z3⁄4 is therefore (−∞, 0] and the cut of (3 − z)1/4 is (−∞, 3]. It is easy to see that the cut of the product of the two, i.e. f(z), is [0, 3], because f(z) is actually continuous across (−∞, 0). This is because when z = −r < 0 and we approach the cut from above, f(z) has the value

When we approach from below, f(z) has the value

But

so that we have continuity across the cut. This is illustrated in the diagram, where the two black oriented circles are labelled with the corresponding value of the argument of the logarithm used in z3⁄4 and (3 − z)1/4.

We will use the contour shown in green in the diagram. To do this we must compute the value of f(z) along the line segments just above and just below the cut.

Let z = r (in the limit, i.e. as the two green circles shrink to radius zero), where 0 ≤ r ≤ 3. Along the upper segment, we find that f(z) has the value and along the lower segment,

It follows that the integral of f(z)/5 − z along the upper segment is −iI in the limit, and along the lower segment, I.

If we can show that the integrals along the two green circles vanish in the limit, then we also have the value of I, by the Cauchy residue theorem. Let the radius of the green circles be ρ, where ρ < 0.001 and ρ → 0, and apply the ML inequality. For the circle CL on the left, we find

Similarly, for the circle CR on the right, we have

Now using the Cauchy residue theorem, we have where the minus sign is due to the clockwise direction around the residues. Using the branch of the logarithm from before, clearly

The pole is shown in blue in the diagram. The value simplifies to

We use the following formula for the residue at infinity:

Substituting, we find and where we have used the fact that −1 = eπi for the second branch of the logarithm. Next we apply the binomial expansion, obtaining

The conclusion is that

Finally, it follows that the value of I is which yields

Evaluation with residue theorem

[edit]Using the residue theorem, we can evaluate closed contour integrals. The following are examples on evaluating contour integrals with the residue theorem.

Using the residue theorem, let us evaluate this contour integral.

Recall that the residue theorem states

where is the residue of , and the are the singularities of lying inside the contour (with none of them lying directly on ).

has only one pole, . From that, we determine that the residue of to be

Thus, using the residue theorem, we can determine:

Multivariable contour integrals

[edit]To solve multivariable contour integrals (i.e. surface integrals, complex volume integrals, and higher order integrals), we must use the divergence theorem. For now, let be interchangeable with . These will both serve as the divergence of the vector field denoted as . This theorem states:

In addition, we also need to evaluate where is an alternate notation of . The divergence of any dimension can be described as

Example 1

[edit]Let the vector field and be bounded by the following

The corresponding double contour integral would be set up as such:

We now evaluate . Meanwhile, set up the corresponding triple integral:

Example 2

[edit]Let the vector field , and remark that there are 4 parameters in this case. Let this vector field be bounded by the following:

To evaluate this, we must utilize the divergence theorem as stated before, and we must evaluate . Let

Thus, we can evaluate a contour integral with . We can use the same method to evaluate contour integrals for any vector field with as well.

Integral representation

[edit]In complex analysis, an integral representation expresses a function as a contour integral in the complex plane. Such representations are central to the theory of holomorphic functions and are closely tied to the fundamental theorems of complex integration.

One of the most important examples is Cauchy's integral formula, which provides a way to reconstruct an analytic function from its values on a surrounding contour:

Where is a function holomorphic on and inside the simple closed contour , is a point inside , and is the variable of integration. This formula shows that the values of inside the contour are determined by its values along the contour.

Examples

[edit]Inverse Laplace Transform

[edit]The inverse Laplace transform is defined by a complex contour integral known as the Bromwich integral:

This integral expresses a function in terms of its Laplace transform .

Sinc Function Representation

[edit]The following integral gives a representation the sinc function:

Although this is a real integral, methods from contour integration are often used in its derivation or evaluation.

Gamma Function

[edit]The Gamma function has the following integral representation:

Extensions of this definition involve contour integrals in the complex plane.

Riemann Zeta Function

[edit]The original definition of the Riemann zeta function via a Dirichlet series,

,

is only valid for , but

,

where the integration is done over the Hankel contour , is valid for all complex not equal to .

Applications

[edit]Integral representations are used to evaluate definite integrals, derive function identities, and solve differential equations. They also appear in complex asymptotic analysis, potential theory, and mathematical physics.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Stalker, John (1998). Complex Analysis: Fundamentals of the Classical Theory of Functions. Springer. p. 77. ISBN 0-8176-4038-X.

- ^ Bak, Joseph; Newman, Donald J. (1997). "Chapters 11 & 12". Complex Analysis. Springer. pp. 130–156. ISBN 0-387-94756-6.

- ^ Krantz, Steven George (1999). "Chapter 2". Handbook of Complex Variables. Springer. ISBN 0-8176-4011-8.

- ^ Mitrinović, Dragoslav S.; Kečkić, Jovan D. (1984). "Chapter 2". The Cauchy Method of Residues: Theory and Applications. Springer. ISBN 90-277-1623-4.

- ^ Mitrinović, Dragoslav S.; Kečkić, Jovan D. (1984). "Chapter 5". The Cauchy Method of Residues: Theory and Applications. Springer. ISBN 90-277-1623-4.

- ^ a b c d e Saff, Edward B.; Snider, Arthur David (2003). "Chapter 4". Fundamentals of Complex Analysis with Applications to Engineering, Science, and Mathematics (3rd ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-1390-7874-6.

Further reading

[edit]- Titchmarsh, E. C. (1939), The Theory of Functions (2nd ed.), Oxford University Press; reprinted, 1968, ISBN 0-19-853349-7

- Marko Riedel et al., Problème d'intégrale, Les-Mathematiques.net, in French.

- Marko Riedel et al., Integral by residue, math.stackexchange.com.

- W W L Chen, Introduction to Complex Analysis

- Various authors, sin límites ni cotas, es.ciencia.matematicas, in Spanish.

External links

[edit]- "Complex integration, method of", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

Contour integration

View on GrokipediaCurves and Paths in the Complex Plane

Directed Smooth Curves

In complex analysis, a directed smooth curve, also known as a contour or path, is a continuous function that is piecewise continuously differentiable, meaning it is differentiable on a finite number of subintervals of where the derivative is continuous and non-zero on each subinterval, ensuring differentiability almost everywhere to avoid singularities in the path.[5][6] This structure allows the curve to be composed of smooth segments joined at finitely many points, such as corners, while maintaining overall continuity, which is essential for defining paths suitable for integration without introducing discontinuities.[7] The parametrization of such a curve is given by , where and are real-valued functions that are piecewise continuously differentiable on , with the derivative satisfying almost everywhere to ensure the curve does not have stationary points.[7] The arc length element along the curve is then , which measures the infinitesimal displacement in the complex plane and provides a natural way to quantify the curve's length as .[6] The orientation of the directed smooth curve is determined by the direction of traversal as increases from to , assigning a consistent "forward" direction to the path.[7] The reversal of this orientation, denoted by , is the curve traversed in the opposite direction, defined by for , which effectively negates the direction while preserving the image of the curve in the complex plane.[8] Closed contours represent special cases of these directed smooth curves where , but their topological properties are addressed separately.[5]Closed Contours and Jordan Curves

A closed contour in the complex plane is a directed smooth curve such that , forming a loop that returns to its starting point.[9] These contours are constructed from directed smooth curves, where the endpoint of one segment coincides with the starting point of the next, ensuring continuity along the path.[10] The orientation of a closed contour is typically positive when traversed counterclockwise, which aligns with the standard convention for enclosing regions in the plane.[10] A simple closed contour is a special case where the curve does not intersect itself except at the initial and final point, maintaining a non-self-overlapping structure throughout its parametrization.[10] This property ensures that the contour bounds a well-defined region without complications from crossings. The Jordan curve theorem states that any simple closed contour in the complex plane divides into two disjoint connected components: a bounded interior region and an unbounded exterior region, both open sets with the contour as their common boundary.[11] For a positively oriented simple closed contour (counterclockwise traversal), the interior is the region enclosed by the curve, which is crucial for topological considerations in complex analysis, such as determining the domain for applying theorems like Cauchy's.[11][10] For practical purposes in integration, closed contours are often required to be rectifiable, meaning they have finite total arc length given by , where is continuous and the integral converges.[10] This finite length condition guarantees that the contour is of bounded variation, allowing for the well-defined existence of integrals along the path without divergence issues. Rectifiability is essential for simple closed contours as well, ensuring the Jordan decomposition holds in a measurable sense.[10]Definition and Properties of Contour Integrals

Formal Definition for Continuous Functions

In complex analysis, the contour integral of a continuous function along a directed smooth curve in the complex plane is formally defined using a parametrization of the curve. Suppose is a smooth parametrization of the curve with for , and is continuous on the image of . Then, the contour integral is given by where the right-hand side is the standard Riemann integral over the real interval .[12][13] The existence of this integral is guaranteed when is continuous on a compact curve , as continuity on a compact set ensures is bounded and uniformly continuous, allowing the Riemann integral to converge.[13] For piecewise smooth curves, the integral is defined by summing the integrals over each smooth segment.[12] The contour integral satisfies linearity: for complex constants and continuous functions on , This follows directly from the linearity of the Riemann integral.[14][13] Additional properties include additivity over concatenated curves: if , where and share an endpoint, then .[14] The reversal property states that , where traverses the curve in the opposite direction.[12] Furthermore, if on and the length of is , then the ML-inequality provides the bound .[14][13]Generalization from Riemann Integrals

Contour integration extends the concept of Riemann integrals from the real line to curves in the complex plane, providing a framework for evaluating integrals of complex-valued functions along directed paths. In the real case, for a real-valued function defined on a curve , the line integral with respect to arc length is given by , which measures the accumulation of weighted by the infinitesimal arc length .[15] This formulation relies on the scalar nature of real differentials and preserves orientation through the absolute value of the speed. In contrast, the complex contour integral for a complex-valued function along a parametrized curve is defined as , omitting the modulus and thus incorporating the direction and magnitude of the complex displacement .[1] This generalization treats as a complex differential , enabling the integral to capture vector-like behavior in the plane without the scalar restriction of arc length.[16] Writing where , the contour integral decomposes into real line integrals: , linking it directly to the real and imaginary components of the path.[1] This vector form highlights how contour integration unifies separate real integrals into a single complex expression, facilitating connections to theorems like Green's theorem in vector calculus.[15] The inclusion of in the integrand motivates the study of contour integrals by allowing tests for holomorphicity: a continuous function is holomorphic in a domain if for every closed contour in that domain (Morera's theorem), a property that, together with Cauchy's theorem, distinguishes complex from real integration.[17] This criterion underpins Cauchy's theorem and enables powerful analytic continuations. The foundations of contour integration were developed by Augustin-Louis Cauchy in the 1820s as part of his pioneering work on complex function theory, including studies on residues and definite integrals that extended real analysis to the complex plane.[18]Direct Computation of Contour Integrals

Parametrization Techniques

To compute a contour integral directly, where is a continuous complex function and is a directed smooth curve, one parametrizes the curve as with and as the endpoints, and then evaluates the real integral , assuming is differentiable with continuous derivative.[19] This approach reduces the complex line integral to a standard Riemann integral over the real parameter interval, leveraging real analysis techniques for evaluation.[20] Common parametrizations simplify this process for basic curves. For a straight line segment from to , use for , yielding .[21] For the unit circle centered at the origin, traversed counterclockwise, parametrize as for , so .[20] These choices ensure the parametrization is smooth and oriented correctly, facilitating substitution into the integral formula. For more intricate contours composed of multiple segments, such as polygonal paths or combinations of lines and arcs, decompose the contour into piecewise smooth parts , where each is parametrized separately over its interval, and sum the resulting integrals , provided continuity holds at the junctions .[19] This additive property allows handling of non-smooth but piecewise smooth curves common in applications. Direct parametrization is practical only for relatively simple functions and curves , as the resulting real integral may require advanced techniques like substitution or partial fractions; for complex topologies or non-elementary , the method becomes computationally tedious and inefficient.[3]Example: Integral Over a Straight Line and Circle

To illustrate direct computation of contour integrals via parametrization, consider the integral of the function along the straight line segment from to . Parametrize the path as for , so . The integral becomes This result matches the antiderivative evaluation , confirming the computation.[22] Next, evaluate the integral of over the unit circle , traversed counterclockwise. Parametrize the contour as for , so . The integral is since . This zero result holds because is entire (analytic everywhere), and the integral of an analytic function over a closed contour vanishes, as will be formalized later in Cauchy's theorem.[22] For numerical approximation after parametrization, the midpoint rule can be applied to the resulting real integral, treating the complex-valued integrand componentwise. For the straight-line example in (1), divide into subintervals of width , with midpoints for . The approximation is which converges to as . This method extends the standard midpoint rule for real integrals to the parametrized form.Fundamental Theorems in Contour Integration

Cauchy's Theorem

Cauchy's theorem is a foundational result in complex analysis that asserts the vanishing of contour integrals of holomorphic functions over closed paths. Specifically, if is holomorphic in a simply connected domain and is a simple closed contour in such that the interior of is also contained in , then This holds under the condition that is analytic throughout the domain enclosing and its interior, ensuring no singularities disrupt the integration.[23] The proof relies on Goursat's strengthened version of the theorem, which eliminates the need for continuous differentiability on the boundary. Goursat's theorem states that if is complex differentiable at every point in a triangular domain with boundary , then . The proof for triangles involves partitioning the domain into smaller sub-triangles and using estimates based on the differentiability condition , showing the integral over the boundary tends to zero as the partition refines. Extending this to simply connected domains, a primitive exists, satisfying . For a closed contour , the integral becomes since the path returns to the starting point.[24][23] An important extension is Morera's theorem, which serves as a converse under milder assumptions. If is continuous on a region and for every simple closed rectifiable curve in , then is holomorphic on . The proof constructs a primitive via line integrals from a fixed point and verifies differentiability, leveraging the zero-integral condition to confirm analyticity. This theorem is particularly useful for proving holomorphicity of functions defined by integrals or series.[25]Cauchy Integral Formula and Derivatives

The Cauchy integral formula expresses the value of a holomorphic function at an interior point of a contour in terms of an integral over the contour itself. Specifically, if is holomorphic on a domain containing a simple closed positively oriented contour and its interior, and is a point inside , then This formula, a direct consequence of Cauchy's theorem, allows evaluation of holomorphic functions using boundary integrals.[26] To derive the formula, consider the function for . This function is holomorphic in the region inside except at , where it has an isolated singularity. Let be small enough that the circle lies inside , and apply Cauchy's theorem to the annular region between and this small circle, yielding . As , the integral over the small circle approaches , since near , and thus .[27] The formula extends to higher derivatives by differentiating under the integral sign, justified by the uniform convergence of the differentiated integrand on . For the first derivative, In general, for the -th derivative where , This generalization follows from repeated differentiation, preserving holomorphy inside .[28] Cauchy estimates provide bounds on these derivatives, quantifying how rapidly holomorphic functions can grow. If on and is the distance from to , then This inequality, derived via the ML-inequality on the contour integral for , implies that derivatives are controlled by the maximum modulus on the boundary and the distance to it.[26]Residues and the Residue Theorem

Computing Residues

In complex analysis, the residue of a function at an isolated singularity is defined as the coefficient in its Laurent series expansion around , or equivalently, , where is any simple closed positively oriented contour encircling once and lying in a region where is analytic except at .[29] This integral representation isolates the contribution from the term in the series.[29] For a simple pole at (a pole of order 1), the residue can be computed directly as , assuming the limit exists and is finite.[29] This formula arises from the Laurent series, where the principal part is , and multiplying by yields .[29] For a function with analytic and , this simplifies to , which aligns with the Cauchy integral formula as a special case where the residue of at equals .[29] For a pole of order at , the residue is the coefficient from the Laurent series, given by .[29] Equivalently, if with analytic and , then , obtained by expanding in its Taylor series around and identifying the term that produces the contribution.[29] Essential singularities require extracting from the full Laurent series, as no finite-order formula applies due to the infinite principal part.[29] For example, the function has an essential singularity at , with Laurent series ; the coefficient of is , so .[29] The residue at infinity, , for a function analytic at infinity (except possibly at finite singularities), is defined as , where is a large positively oriented circle enclosing all finite singularities.[30] It can be computed via the substitution , yielding , which transforms the expansion at infinity into a Laurent series at .[30]Statement and Application of the Residue Theorem

The residue theorem, also known as Cauchy's residue theorem, provides a fundamental method for evaluating contour integrals in the complex plane. Suppose is analytic in a simply connected domain except for a finite number of isolated singularities inside a simple closed positively oriented contour that lies in and does not pass through any singularities. Then, where the sum is taken over all singularities enclosed by , and denotes the residue of at .[31] To apply the residue theorem for computing a contour integral, first identify all isolated singularities of lying inside the contour , assuming is traversed counterclockwise. Next, compute the residue at each such singularity using techniques such as Laurent series expansions or specific formulas for simple or higher-order poles. The integral is then obtained by summing these residues and multiplying the total by . This approach simplifies evaluation compared to direct parametrization, especially for functions with known singularities.[31] When a singularity lies on the contour , the standard residue theorem does not apply directly, as the function is not analytic on . In such cases, modify the contour by introducing a small semicircular indentation around the pole, typically of radius , to exclude it from the interior. The integral over the indented contour equals times the sum of residues inside, and the contribution from the semicircular indentation approaches times the residue at the pole, depending on the orientation (counterclockwise yields ; clockwise yields ). The original integral is recovered as the Cauchy principal value along the unindented path plus the half-residue contribution from the indentation.[32] Beyond integral evaluation, the residue theorem finds applications in stability analysis, particularly in control theory, where the locations and signs of residues of characteristic functions help determine system stability by assessing pole placements in the complex plane. For instance, residues are used to quantify sensitivities and participations in oscillatory stability studies of dynamic systems.[33]Applications to Evaluate Real Integrals

Trigonometric Integrals via Semicircular Contours

One common application of contour integration involves evaluating real integrals of the form or , where is a rational function that decays sufficiently fast at infinity and . These trigonometric integrals can be addressed by considering the complex function and integrating over a semicircular contour in the upper half-plane, consisting of the real axis from to and a semicircular arc of radius . As , the integral over the real axis approaches the desired integral (or its imaginary/real part), provided the contribution from vanishes. This approach leverages the residue theorem, where the contour integral equals times the sum of residues of at poles in the upper half-plane.[34] A key tool for ensuring the arc integral over tends to zero is Jordan's lemma. For , on the semicircle with , the term decays exponentially for since . If for large on , the integral's magnitude is bounded by for some , which approaches zero as . Thus, over upper half-plane poles, and the original trigonometric integral is the real or imaginary part accordingly.[4] The procedure typically involves: (1) expressing the trigonometric function via Euler's formula, e.g., ; (2) selecting the upper half-plane contour for to exploit decay; (3) identifying simple poles of in and computing residues of , often for simple poles; (4) applying the residue theorem and taking the limit ; (5) extracting the real or imaginary part. For instance, consider . Here, , poles at , with in the upper half-plane. The residue at is , so the contour integral is . Since the imaginary part (sine) integrates to zero by oddness, the cosine integral equals .[34] Semicircular contours are particularly suited for non-periodic trigonometric integrals over infinite domains, but contour methods also extend to periodic trigonometric integrals like , where is rational, using the unit circle contour instead. For example, to evaluate with , substitute , so and , transforming the integral to . The poles are roots of , , with the root inside the unit circle being the one with smaller magnitude. The residue at that pole yields the integral value via the residue theorem.[35]Integrals Involving Branch Cuts

In contour integration, multivalued functions such as the complex logarithm require careful handling due to their branch points, typically at and , where the function fails to be single-valued. To define a single-valued branch, a branch cut is introduced, often along the positive real axis, rendering the function analytic in the cut plane . The argument of is then restricted to , ensuring is holomorphic in this domain./01%3A_Complex_Algebra_and_the_Complex_Plane/1.11%3A_The_Function_log(z)) Integrals involving such functions, like those with fractional powers for non-integer , necessitate contours that respect the branch cut, either avoiding it or encircling it to capture the discontinuity. A common approach is the keyhole contour, which consists of a large circle of radius , a small circle of radius around the origin, and two nearly overlapping line segments parallel to the positive real axis, just above and below the cut, forming a narrow "keyhole" shape that avoids crossing the branch point at zero. As and , the integrals over the circular arcs vanish under suitable convergence conditions, leaving the contributions from the line segments related by the phase shift across the cut. The residue theorem applies to the enclosed poles, provided they lie away from the cut.[36] A representative example is the evaluation of for . Consider with the branch cut along and , so . The keyhole contour encloses the simple pole at , where the residue is . Thus, . The upper line segment contributes , while the lower contributes (noting the exponent is ). Combining yields , so . This result, known as a special case of the beta function reflection formula, highlights how the branch cut induces the phase factor enabling real integral evaluation.[36] Another specialized contour is the Hankel contour, used for integrals involving branch cuts along the negative real axis, such as in the representation of the Gamma function . The contour begins at −∞ along the upper side of the cut (where ), encircles the origin counterclockwise in a small circle of radius , and returns to −∞ along the lower side (), with the branch cut for along . The integral is , valid for and entire in except at non-positive integers, where the sine factor cancels poles. As , the small arc contribution vanishes, and for positive real , the contour collapses to the standard Euler integral. This representation is particularly useful for analytic continuation and asymptotic analysis.[37] In practice, contours involving branch cuts can often be deformed to simpler paths, provided the deformation avoids crossing singularities or the cut itself, preserving the integral value by Cauchy's theorem in regions of analyticity. For instance, the position of the branch cut may be shifted (e.g., from the positive to negative real axis) if the integrand remains analytic in the deformed region and encloses the same residues, simplifying computations while accounting for any induced phase changes. Such deformations are essential for handling complicated cut configurations in advanced applications./10%3A_Definite_Integrals_Using_the_Residue_Theorem/10.04%3A_Integrands_with_branch_cuts)Special Examples and Advanced Techniques

Cauchy Distribution and Probability Densities

The Cauchy distribution is a continuous probability distribution with probability density function This form ensures it is non-negative and symmetric about zero.[32] To confirm normalization, evaluate . The key integral is computed via contour integration in the complex plane by considering the function over a semicircular contour in the upper half-plane, consisting of the real interval and the semicircular arc of radius .[32] The integrand has simple poles where , at and ; only lies inside for large . The residue at is computed as By the residue theorem, . As , the integral over vanishes because on the arc, making the length times maximum value tend to zero. Thus, , confirming .[32] The moments of the Cauchy distribution are defined as for . Unlike the normalization case (), these integrals do not converge to finite values due to the heavy tails of the distribution, where as . Specifically, , which diverges for all .[38] Contour integration illustrates this non-convergence: to evaluate (up to the factor), consider over the same upper-half-plane semicircle . The poles remain at , off the real axis, so no indentation is needed. However, on the arc , ; the arc integral has magnitude bounded by , which tends to infinity as for , rather than vanishing. Thus, the residue theorem cannot be applied to extract the real-line integral, confirming the lack of finite moments. For odd , the integrand is odd, so the Cauchy principal value exists and equals zero by symmetry, but absolute convergence fails, precluding a well-defined moment.[32][38] A key application of contour integration to the Cauchy distribution is deriving its characteristic function , which equals . For , evaluate using the upper-half-plane contour for , as for , ensuring the arc integral vanishes by the Jordan lemma. The residue at is , so the contour integral is , yielding .[39] For , close in the lower half-plane (where the exponential decays for ), enclosing the pole at with residue . The contour is clockwise (negatively oriented), so the integral is . Since , , yielding overall. This non-differentiable form at further underscores the absence of moments.[39]Logarithmic Integrals and Residue at Infinity

Logarithmic integrals often arise in applications requiring the evaluation of real definite integrals from 0 to ∞ involving the natural logarithm, which introduces multivalued behavior in the complex plane. To handle this, contour integration employs a principal branch of the logarithm with a branch cut typically along the positive real axis, allowing the integral to be related to the residues of the complex function , where is a positive integer and is a rational function with appropriate poles. A representative example is the evaluation of . This can be computed using a semicircular contour in the upper half-plane, with the branch cut along the positive real axis and small indentations around the origin to avoid the branch point. The integrand has poles at in the upper half-plane and in the lower half-plane. The contour integral over this path yields times the residue at , accounting for the contribution from the large arc vanishing as the radius tends to infinity due to the behavior of . The real-axis contribution, adjusted for the branch, gives the desired integral as .[40] Alternatively, differentiation under the integral sign can be used: consider , which evaluates to for via contour methods, and then . This approach leverages the parameter differentiation to introduce the logarithmic factors while relying on residue calculus for the parameterized integral.[41] For more involved cases like the square of the logarithm with indentations at both 0 and ∞, a keyhole contour modified with small circles around these points is employed. The function is integrated over this contour, capturing residues at the poles and accounting for the branch jump across the cut. The contributions from the indentations at 0 and ∞ provide boundary terms, while the large and small arcs vanish appropriately, leading to the real integral via the residue sum. This method highlights the interplay between branch structure and pole locations for precise evaluation.[42] The residue at infinity extends the residue theorem to the extended complex plane, defined as , where . For a function analytic at infinity except possibly at finite poles, the sum of all residues, including at infinity, is zero. Consequently, for a large positively oriented contour enclosing all finite poles, . This is particularly useful for integrals over the entire real line when the arc contributions vanish, allowing evaluation via the single residue at infinity rather than summing multiple finite residues. In the context of principal value integrals involving logarithms, such as variants of , contours closing in the upper or lower half-plane are selected based on the imaginary part of the logarithm to ensure convergence. For the principal branch, closing in the upper half-plane captures the residue at , while the lower half-plane uses , with the principal value arising from symmetric indentations around singularities on the real axis. The integral equals zero because , as the substitution yields , implying .Multivariable and Parametric Extensions

Surface Integrals in Complex Variables

In several complex variables, the concept of contour integration generalizes to integrals of differential forms over surfaces embedded in ℂⁿ, where surfaces are typically real 2-dimensional submanifolds. For a 2-form ω defined on an open set in ℂ², the surface integral ∫_S ω over a parametrized oriented surface S ⊂ ℂ², with parametrization φ: U → S where U ⊂ ℝ² is an open set, is computed as ∫_U φ*ω, the integral of the pullback form over U with the induced orientation. This construction preserves the complex structure and allows for the analysis of holomorphic properties along the surface.[43] A key relation is provided by the generalized Stokes' theorem, which states that for a compact oriented surface S with boundary ∂S and a smooth 1-form α on a neighborhood of S, ∫S dα = ∫{∂S} α, where d denotes the exterior derivative. In the complex setting, this theorem applies to forms of various types, including (2,0)-forms like those involving dz and dw, and facilitates the evaluation of integrals by reducing them to lower-dimensional boundary contributions. The theorem holds in the broader framework of oriented manifolds and is essential for deriving integral representations in higher dimensions.[43] Consider the example of integrating the basic holomorphic (2,0)-form ω = dz ∧ dw over the distinguished boundary surface of the unit polydisk D = {(z, w) ∈ ℂ² : |z| < 1, |w| < 1}, which is the 2-dimensional torus Γ = { (z, w) : |z| = 1, |w| = 1 }. Parametrizing Γ by θ, ϕ ∈ [0, 2π) with z = e^{iθ}, w = e^{iϕ}, the pullback yields dz ∧ dw = -e^{i(θ + ϕ)} dθ ∧ dϕ, and the integral evaluates to zero due to the vanishing of the Fourier coefficients over full periods. However, this form relates to volume computations via Stokes' theorem: since dz ∧ dw = d(z dw), the integral over D (interpreted through boundary evaluation) connects to the complex volume measure, yielding the Euclidean volume of the polydisk as π² when paired with appropriate normalization factors for the full (2,2)-form.[44] For holomorphic 2-forms of the type ω = f(z, w) dz ∧ dw, where f is holomorphic on a domain containing S, the surface integral ties directly to multivariable extensions of Cauchy's theorem. Specifically, if S is the boundary of a suitable domain and f satisfies the Cauchy-Riemann equations in several variables, the integral ∫_S ω can be linked to the Cauchy integral formula: for a point (z₀, w₀) interior to the domain bounded by S, f(z₀, w₀) = \frac{1}{(2\pi i)^2} \int_S \frac{f(\zeta, \eta)}{(\zeta - z_0)(\eta - w_0)} d\zeta \wedge d\eta, generalizing the one-variable case to higher dimensions via wedge products of 1-forms. This formula holds for polydiscs and more general pseudoconvex domains, emphasizing the role of holomorphic forms in representation theory.[45] Applications of these surface integrals appear prominently in the study of several complex variables, particularly in Hartogs' extension theorem. This theorem asserts that if Ω ⊂ ℂⁿ (n ≥ 2) is open and K ⊂ Ω is compact with connected complement, then any holomorphic function on Ω \ K extends holomorphically to all of Ω. The proof relies on solving the inhomogeneous Cauchy-Riemann equation \bar{\partial} u = g using integral operators over surfaces like boundaries of pseudoconvex domains, where surface integrals of (0,1)-forms dual to holomorphic (n,0)-forms provide the necessary extensions, highlighting the absence of isolated singularities in higher dimensions unlike the one-variable case.[46]Integral Representations of Functions

Contour integrals provide powerful representations for special functions, enabling their extension to broader domains in the complex plane and yielding insights into their asymptotic behavior. These representations often involve carefully chosen contours that avoid singularities or branch cuts, leveraging the residue theorem to express the function in terms of integrals over paths where the integrand is analytic. Such formulations are essential for functions initially defined by series or real integrals, allowing analytic continuation and approximations for large parameters. One prominent example is the inverse Laplace transform, which recovers the original function from its transform via a contour integral along the Bromwich path—a vertical line parallel to the imaginary axis in the right half-plane, positioned to the right of all singularities. The formula is where is the Laplace transform of , and ensures convergence. This integral can be evaluated using residues by closing the contour appropriately, depending on the sign of .[47] The reciprocal of the Gamma function admits a contour integral representation via the Hankel contour, which starts at −∞ along the real axis, encircles the origin counterclockwise in a small circle, and returns to −∞. The representation is valid for all complex z except non-positive integers, where t^{-z} takes its principal value with the branch cut along the negative real axis; this form provides analytic continuation of the Gamma function.[48] For the Riemann zeta function, a contour integral provides an analytic continuation beyond , incorporating the pole at . The representation is where is a contour that starts at , loops around the origin counterclockwise, and returns to , avoiding the branch cut along the positive real axis; this form facilitates the functional equation through contour manipulation and residue computation.[49] These integral representations enable key applications, such as analytic continuation by deforming contours to regions where series diverge, thus defining functions meromorphically in the complex plane. Additionally, they support asymptotic expansions via methods like the saddle-point approximation or steepest descent, where the contour is shifted to pass through dominant saddle points, yielding series approximations for large or other parameters; for instance, the Stirling series for emerges from the Hankel representation.[50]References

- https://proofwiki.org/wiki/Definition:Contour/Closed/Complex_Plane

- https://proofwiki.org/wiki/Jordan_Curve_Theorem

![{\displaystyle z:[a,b]\to \mathbb {C} }](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ec4cdae12570b1d1b73fe6a9c373d34c590f9d6b)

![{\displaystyle [a,b]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9c4b788fc5c637e26ee98b45f89a5c08c85f7935)

![{\displaystyle \oint _{C}f(z)\,dz=\oint _{C}{\frac {\frac {1}{(z+i)^{2}}}{(z-i)^{2}}}\,dz=2\pi i\,\left.{\frac {d}{dz}}{\frac {1}{(z+i)^{2}}}\right|_{z=i}=2\pi i\left[{\frac {-2}{(z+i)^{3}}}\right]_{z=i}={\frac {\pi }{2}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/72188d37bdab77d054bf8c8852ce038b0417d5d2)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}&-{\frac {4i}{3}}\left[\oint _{C_{1}}{\frac {\frac {z}{\left(z+{\sqrt {3}}i\right)\left(z-{\sqrt {3}}i\right)\left(z+{\frac {i}{\sqrt {3}}}\right)}}{z-{\frac {i}{\sqrt {3}}}}}\,dz+\oint _{C_{2}}{\frac {\frac {z}{\left(z+{\sqrt {3}}i\right)\left(z-{\sqrt {3}}i\right)\left(z-{\frac {i}{\sqrt {3}}}\right)}}{z+{\frac {i}{\sqrt {3}}}}}\,dz\right]\\={}&-{\frac {4i}{3}}\left[2\pi i\left[{\frac {z}{\left(z+{\sqrt {3}}i\right)\left(z-{\sqrt {3}}i\right)\left(z+{\frac {i}{\sqrt {3}}}\right)}}\right]_{z={\frac {i}{\sqrt {3}}}}+2\pi i\left[{\frac {z}{\left(z+{\sqrt {3}}i\right)\left(z-{\sqrt {3}}i\right)\left(z-{\frac {i}{\sqrt {3}}}\right)}}\right]_{z=-{\frac {i}{\sqrt {3}}}}\right]\\={}&{\frac {8\pi }{3}}\left[{\frac {\frac {i}{\sqrt {3}}}{\left({\frac {i}{\sqrt {3}}}+{\sqrt {3}}i\right)\left({\frac {i}{\sqrt {3}}}-{\sqrt {3}}i\right)\left({\frac {i}{\sqrt {3}}}+{\frac {i}{\sqrt {3}}}\right)}}+{\frac {-{\frac {i}{\sqrt {3}}}}{\left(-{\frac {i}{\sqrt {3}}}+{\sqrt {3}}i\right)\left(-{\frac {i}{\sqrt {3}}}-{\sqrt {3}}i\right)\left(-{\frac {i}{\sqrt {3}}}-{\frac {i}{\sqrt {3}}}\right)}}\right]\\={}&{\frac {8\pi }{3}}\left[{\frac {\frac {i}{\sqrt {3}}}{\left({\frac {4}{\sqrt {3}}}i\right)\left(-{\frac {2}{i{\sqrt {3}}}}\right)\left({\frac {2}{{\sqrt {3}}i}}\right)}}+{\frac {-{\frac {i}{\sqrt {3}}}}{\left({\frac {2}{\sqrt {3}}}i\right)\left(-{\frac {4}{\sqrt {3}}}i\right)\left(-{\frac {2}{\sqrt {3}}}i\right)}}\right]\\={}&{\frac {8\pi }{3}}\left[{\frac {\frac {i}{\sqrt {3}}}{i\left({\frac {4}{\sqrt {3}}}\right)\left({\frac {2}{\sqrt {3}}}\right)\left({\frac {2}{\sqrt {3}}}\right)}}+{\frac {-{\frac {i}{\sqrt {3}}}}{-i\left({\frac {2}{\sqrt {3}}}\right)\left({\frac {4}{\sqrt {3}}}\right)\left({\frac {2}{\sqrt {3}}}\right)}}\right]\\={}&{\frac {8\pi }{3}}\left[{\frac {\frac {1}{\sqrt {3}}}{\left({\frac {4}{\sqrt {3}}}\right)\left({\frac {2}{\sqrt {3}}}\right)\left({\frac {2}{\sqrt {3}}}\right)}}+{\frac {\frac {1}{\sqrt {3}}}{\left({\frac {2}{\sqrt {3}}}\right)\left({\frac {4}{\sqrt {3}}}\right)\left({\frac {2}{\sqrt {3}}}\right)}}\right]\\={}&{\frac {8\pi }{3}}\left[{\frac {\frac {1}{\sqrt {3}}}{\frac {16}{3{\sqrt {3}}}}}+{\frac {\frac {1}{\sqrt {3}}}{\frac {16}{3{\sqrt {3}}}}}\right]\\={}&{\frac {8\pi }{3}}\left[{\frac {3}{16}}+{\frac {3}{16}}\right]\\={}&\pi .\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/148b7b3208377c854862d509f2052e2a1433f63b)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\int _{R}^{\varepsilon }{\frac {\sqrt {z}}{z^{2}+6z+8}}\,dz&=\int _{R}^{\varepsilon }{\frac {e^{{\frac {1}{2}}\operatorname {Log} z}}{z^{2}+6z+8}}\,dz\\[6pt]&=\int _{R}^{\varepsilon }{\frac {e^{{\frac {1}{2}}(\log |z|+i\arg {z})}}{z^{2}+6z+8}}\,dz\\[6pt]&=\int _{R}^{\varepsilon }{\frac {e^{{\frac {1}{2}}\log |z|}e^{{\frac {1}{2}}(2\pi i)}}{z^{2}+6z+8}}\,dz\\[6pt]&=\int _{R}^{\varepsilon }{\frac {e^{{\frac {1}{2}}\log |z|}e^{\pi i}}{z^{2}+6z+8}}\,dz\\[6pt]&=\int _{R}^{\varepsilon }{\frac {-{\sqrt {z}}}{z^{2}+6z+8}}\,dz\\[6pt]&=\int _{\varepsilon }^{R}{\frac {\sqrt {z}}{z^{2}+6z+8}}\,dz.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/93d4d0610e00fa1944ba7bf74af772ad3c9417ae)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}-i\pi ^{2}&=\left(\int _{R}+\int _{M}+\int _{N}+\int _{r}\right)f(z)\,dz\\[6pt]&=\left(\int _{M}+\int _{N}\right)f(z)\,dz&&\int _{R},\int _{r}{\mbox{ vanish}}\\[6pt]&=-\int _{\infty }^{0}\left({\frac {\log(-x+i\varepsilon )}{1+(-x+i\varepsilon )^{2}}}\right)^{2}\,dx-\int _{0}^{\infty }\left({\frac {\log(-x-i\varepsilon )}{1+(-x-i\varepsilon )^{2}}}\right)^{2}\,dx\\[6pt]&=\int _{0}^{\infty }\left({\frac {\log(-x+i\varepsilon )}{1+(-x+i\varepsilon )^{2}}}\right)^{2}\,dx-\int _{0}^{\infty }\left({\frac {\log(-x-i\varepsilon )}{1+(-x-i\varepsilon )^{2}}}\right)^{2}\,dx\\[6pt]&=\int _{0}^{\infty }\left({\frac {\log x+i\pi }{1+x^{2}}}\right)^{2}\,dx-\int _{0}^{\infty }\left({\frac {\log x-i\pi }{1+x^{2}}}\right)^{2}\,dx&&\varepsilon \to 0\\&=\int _{0}^{\infty }{\frac {(\log x+i\pi )^{2}-(\log x-i\pi )^{2}}{\left(1+x^{2}\right)^{2}}}\,dx\\[6pt]&=\int _{0}^{\infty }{\frac {4\pi i\log x}{\left(1+x^{2}\right)^{2}}}\,dx\\[6pt]&=4\pi i\int _{0}^{\infty }{\frac {\log x}{\left(1+x^{2}\right)^{2}}}\,dx\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/24d78280283f356694193503094a96eef3538b04)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}&=\iiint _{V}\left({\frac {\partial F_{x}}{\partial x}}+{\frac {\partial F_{y}}{\partial y}}+{\frac {\partial F_{z}}{\partial z}}\right)dV\\[6pt]&=\iiint _{V}\left({\frac {\partial \sin(2x)}{\partial x}}+{\frac {\partial \sin(2y)}{\partial y}}+{\frac {\partial \sin(2z)}{\partial z}}\right)dV\\[6pt]&=\iiint _{V}2\left(\cos(2x)+\cos(2y)+\cos(2z)\right)dV\\[6pt]&=\int _{0}^{1}\int _{0}^{3}\int _{-1}^{4}2(\cos(2x)+\cos(2y)+\cos(2z))\,dx\,dy\,dz\\[6pt]&=\int _{0}^{1}\int _{0}^{3}(10\cos(2y)+\sin(8)+\sin(2)+10\cos(z))\,dy\,dz\\[6pt]&=\int _{0}^{1}(30\cos(2z)+3\sin(2)+3\sin(8)+5\sin(6))\,dz\\[6pt]&=18\sin(2)+3\sin(8)+5\sin(6)\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/45501b475df2826f3e00a5b9e653c443cef66cf3)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}&=\iiiint _{V}\left({\frac {\partial F_{u}}{\partial u}}+{\frac {\partial F_{x}}{\partial x}}+{\frac {\partial F_{y}}{\partial y}}+{\frac {\partial F_{z}}{\partial z}}\right)\,dV\\[6pt]&=\iiiint _{V}\left({\frac {\partial u^{4}}{\partial u}}+{\frac {\partial x^{5}}{\partial x}}+{\frac {\partial y^{6}}{\partial y}}+{\frac {\partial z^{-3}}{\partial z}}\right)\,dV\\[6pt]&=\iiiint _{V}{\frac {4u^{3}z^{4}+5x^{4}z^{4}+5y^{4}z^{4}-3}{z^{4}}}\,dV\\[6pt]&=\iiiint _{V}{\frac {4u^{3}z^{4}+5x^{4}z^{4}+5y^{4}z^{4}-3}{z^{4}}}\,dV\\[6pt]&=\int _{0}^{1}\int _{-10}^{2\pi }\int _{4}^{5}\int _{-1}^{3}{\frac {4u^{3}z^{4}+5x^{4}z^{4}+5y^{4}z^{4}-3}{z^{4}}}\,dV\\[6pt]&=\int _{0}^{1}\int _{-10}^{2\pi }\int _{4}^{5}\left({\frac {4(3u^{4}z^{3}+3y^{6}+91z^{3}+3)}{3z^{3}}}\right)\,dy\,dz\,du\\[6pt]&=\int _{0}^{1}\int _{-10}^{2\pi }\left(4u^{4}+{\frac {743440}{21}}+{\frac {4}{z^{3}}}\right)\,dz\,du\\[6pt]&=\int _{0}^{1}\left(-{\frac {1}{2\pi ^{2}}}+{\frac {1486880\pi }{21}}+8\pi u^{4}+40u^{4}+{\frac {371720021}{1050}}\right)\,du\\[6pt]&={\frac {371728421}{1050}}+{\frac {14869136\pi ^{3}-105}{210\pi ^{2}}}\\[6pt]&\approx {576468.77}\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/31867f3ec2a46e4ab5a26d3ac674804a820d6f21)