Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Related rates

View on WikipediaThis article contains instructions or advice. (October 2015) |

| Part of a series of articles about |

| Calculus |

|---|

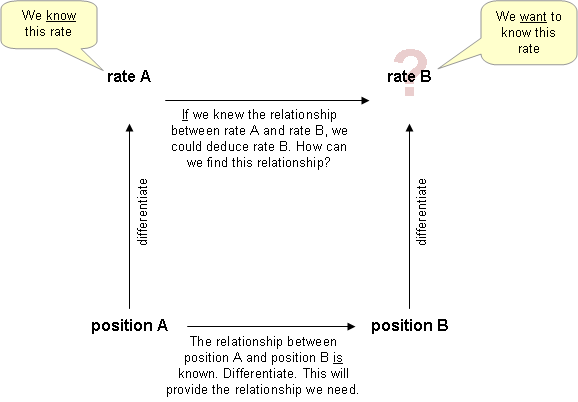

In differential calculus, related rates problems involve finding a rate at which a quantity changes by relating that quantity to other quantities whose rates of change are known. The rate of change is usually with respect to time. Because science and engineering often relate quantities to each other, the methods of related rates have broad applications in these fields. Differentiation with respect to time or one of the other variables requires application of the chain rule,[1] since most problems involve several variables.

Fundamentally, if a function is defined such that , then the derivative of the function can be taken with respect to another variable. We assume is a function of , i.e. . Then , so

Written in Leibniz notation, this is:

Thus, if it is known how changes with respect to , then we can determine how changes with respect to and vice versa. We can extend this application of the chain rule with the sum, difference, product and quotient rules of calculus, etc.

For example, if then

Procedure

[edit]The most common way to approach related rates problems is the following:[2]

- Identify the known variables, including rates of change and the rate of change that is to be found. (Drawing a picture or representation of the problem can help to keep everything in order)

- Construct an equation relating the quantities whose rates of change are known to the quantity whose rate of change is to be found.

- Differentiate both sides of the equation with respect to time (or other rate of change). Often, the chain rule is employed at this step.

- Substitute the known rates of change and the known quantities into the equation.

- Solve for the wanted rate of change.

Errors in this procedure are often caused by plugging in the known values for the variables before (rather than after) finding the derivative with respect to time. Doing so will yield an incorrect result, since if those values are substituted for the variables before differentiation, those variables will become constants; and when the equation is differentiated, zeroes appear in places of all variables for which the values were plugged in.

Example

[edit]A 10-meter ladder is leaning against the wall of a building, and the base of the ladder is sliding away from the building at a rate of 3 meters per second. How fast is the top of the ladder sliding down the wall when the base of the ladder is 6 meters from the wall?

The distance between the base of the ladder and the wall, x, and the height of the ladder on the wall, y, represent the sides of a right triangle with the ladder as the hypotenuse, h. The objective is to find dy/dt, the rate of change of y with respect to time, t, when h, x and dx/dt, the rate of change of x, are known.

Step 1:

Step 2: From the Pythagorean theorem, the equation

describes the relationship between x, y and h, for a right triangle. Differentiating both sides of this equation with respect to time, t, yields

Step 3: When solved for the wanted rate of change, dy/dt, gives us

Step 4 & 5: Using the variables from step 1 gives us:

Solving for y using the Pythagorean Theorem gives:

Plugging in 8 for the equation:

It is generally assumed that negative values represent the downward direction. In doing such, the top of the ladder is sliding down the wall at a rate of 9/4 meters per second.

Physics examples

[edit]Because one physical quantity often depends on another, which, in turn depends on others, such as time, related-rates methods have broad applications in Physics. This section presents an example of related rates kinematics and electromagnetic induction.

Relative kinematics of two vehicles

[edit]

For example, one can consider the kinematics problem where one vehicle is heading West toward an intersection at 80 miles per hour while another is heading North away from the intersection at 60 miles per hour. One can ask whether the vehicles are getting closer or further apart and at what rate at the moment when the North bound vehicle is 3 miles North of the intersection and the West bound vehicle is 4 miles East of the intersection.

Big idea: use chain rule to compute rate of change of distance between two vehicles.

Plan:

- Choose coordinate system

- Identify variables

- Draw picture

- Big idea: use chain rule to compute rate of change of distance between two vehicles

- Express c in terms of x and y via Pythagorean theorem

- Express dc/dt using chain rule in terms of dx/dt and dy/dt

- Substitute in x, y, dx/dt, dy/dt

- Simplify.

Choose coordinate system: Let the y-axis point North and the x-axis point East.

Identify variables: Define y(t) to be the distance of the vehicle heading North from the origin and x(t) to be the distance of the vehicle heading West from the origin.

Express c in terms of x and y via the Pythagorean theorem:

Express dc/dt using chain rule in terms of dx/dt and dy/dt:

| Apply derivative operator to entire function | |

| Square root is outside function; Sum of squares is inside function | |

| Distribute differentiation operator | |

| Apply chain rule to x(t) and y(t)} | |

| Simplify. |

Substitute in x = 4 mi, y = 3 mi, dx/dt = −80 mi/hr, dy/dt = 60 mi/hr and simplify

Consequently, the two vehicles are getting closer together at a rate of 28 mi/hr.

Electromagnetic induction of conducting loop spinning in magnetic field

[edit]The magnetic flux through a loop of area A whose normal is at an angle θ to a magnetic field of strength B is

Faraday's law of electromagnetic induction states that the induced electromotive force is the negative rate of change of magnetic flux through a conducting loop.

If the loop area A and magnetic field B are held constant, but the loop is rotated so that the angle θ is a known function of time, the rate of change of θ can be related to the rate of change of (and therefore the electromotive force) by taking the time derivative of the flux relation

If for example, the loop is rotating at a constant angular velocity ω, so that θ = ωt, then

References

[edit]- ^ "Related Rates". Whitman College. Retrieved 2013-10-27.

- ^ Kreider, Donald. "Related Rates". Dartmouth. Retrieved 2013-10-27.

![{\displaystyle ={\frac {1}{2}}\left(x^{2}+y^{2}\right)^{-1/2}\left[{\frac {d}{dt}}(x^{2})+{\frac {d}{dt}}(y^{2})\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0cac44ff401de75f61defce749e25bb50a849da7)

![{\displaystyle ={\frac {1}{2}}\left(x^{2}+y^{2}\right)^{-1/2}\left[2x{\frac {dx}{dt}}+2y{\frac {dy}{dt}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/03bcdbf3a0028b507ab49e620ee2a2fa1eec1185)