Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Crustacean

View on Wikipedia

| Crustaceans | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Clade: | Pancrustacea |

| Subphylum: | Crustacea |

| Groups included | |

| |

| Cladistically included but traditionally excluded taxa | |

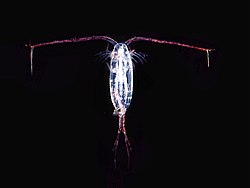

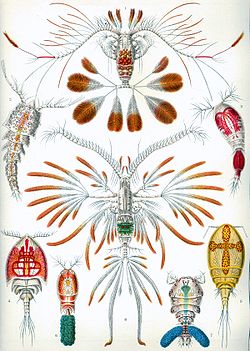

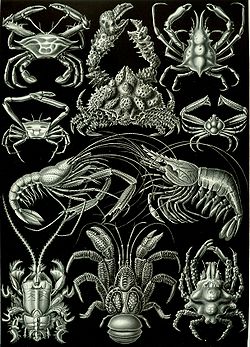

Crustaceans (from Latin word "crustacea" meaning: "those with shells" or "crusted ones") are invertebrate animals that constitute one group of arthropods that are traditionally a part of the subphylum Crustacea (/krəˈsteɪʃə/), a large, diverse group of mainly aquatic arthropods including the more familiar decapods (shrimps, prawns, crabs, lobsters and crayfish), seed shrimps, branchiopods, fish lice, krill, remipedes, isopods, barnacles, copepods, opossum shrimps, amphipods and mantis shrimp.[2] The crustacean group can be treated as a subphylum under the clade Mandibulata. It is now well accepted that the hexapods (insects and entognathans) emerged deep in the crustacean group, with the completed pan-group referred to as Pancrustacea.[3] The three classes Cephalocarida, Branchiopoda and Remipedia are more closely related to the hexapods than they are to any of the other crustaceans (oligostracans and multicrustaceans).[4]

The 67,000 described species range in size from Stygotantulus stocki at 0.1 mm (0.004 in), to the Japanese spider crab with a leg span of up to 3.8 m (12.5 ft) and a mass of 20 kg (44 lb). Like other arthropods, crustaceans have an exoskeleton, which they moult to grow. They are distinguished from other groups of arthropods, such as insects, myriapods and chelicerates, by the possession of biramous (two-parted) limbs, and by their larval forms, such as the nauplius stage of branchiopods and copepods.

Most crustaceans are free-living aquatic animals, but some are terrestrial (e.g. woodlice, sandhoppers), some are parasitic (e.g. Rhizocephala, fish lice, tongue worms) and some are sessile (e.g. barnacles). The group has an extensive fossil record, reaching back to the Cambrian. More than 7.9 million tons of crustaceans per year are harvested by fishery or farming for human consumption,[5] consisting mostly of shrimp and prawns. Krill and copepods are not as widely fished, but may be the animals with the greatest biomass on the planet, and form a vital part of the food chain. The scientific study of crustaceans is known as carcinology (alternatively, malacostracology, crustaceology or crustalogy), and a scientist who works in carcinology is a carcinologist.

Anatomy

[edit]

The body of a crustacean is composed of segments, which are grouped into three regions: the cephalon or head,[6] the pereon or thorax,[7] and the pleon or abdomen.[8] The head and thorax may be fused together to form a cephalothorax,[9] which may be covered by a single large carapace.[10] The crustacean body is protected by the hard exoskeleton, which must be moulted for the animal to grow. The shell around each somite can be divided into a dorsal tergum, ventral sternum and a lateral pleuron. Various parts of the exoskeleton may be fused together.[11]: 289

Each somite, or body segment can bear a pair of appendages: on the segments of the head, these include two pairs of antennae, the mandibles and maxillae;[6] the thoracic segments bear legs, which may be specialised as pereiopods (walking legs) and maxillipeds (feeding legs).[7] Malacostraca and Remipedia (and the hexapods) have abdominal appendages. All other classes of crustaceans have a limbless abdomen, except from a telson and caudal rami which is present in many groups.[12][13] The abdomen in malacostracans bears pleopods,[8] and ends in a telson, which bears the anus, and is often flanked by uropods to form a tail fan.[14] The number and variety of appendages in different crustaceans may be partly responsible for the group's success.[15]

Crustacean appendages are typically biramous, meaning they are divided into two parts; this includes the second pair of antennae, but not the first, which is usually uniramous, the exception being in the Class Malacostraca where the antennules may be generally biramous or even triramous.[16][17] It is unclear whether the biramous condition is a derived state which evolved in crustaceans, or whether the second branch of the limb has been lost in all other groups. Trilobites, for instance, also possessed biramous appendages.[18]

The main body cavity is an open circulatory system, where blood is pumped into the haemocoel by a heart located near the dorsum.[19] Malacostraca have haemocyanin as the oxygen-carrying pigment, while copepods, ostracods, barnacles and branchiopods have haemoglobins.[20] The alimentary canal consists of a straight tube that often has a gizzard-like "gastric mill" for grinding food and a pair of digestive glands that absorb food; this structure goes in a spiral format.[21] Structures that function as kidneys are located near the antennae. A brain exists in the form of ganglia close to the antennae, and a collection of major ganglia is found below the gut.[22]

In many decapods, the first (and sometimes the second) pair of pleopods are specialised in the male for sperm transfer. Many terrestrial crustaceans (such as the Christmas Island red crab) mate seasonally and return to the sea to release the eggs. Others, such as woodlice, lay their eggs on land, albeit in damp conditions. In most decapods, the females retain the eggs until they hatch into free-swimming larvae.[23]

Ecology

[edit]

Most crustaceans are aquatic, living in either marine or freshwater environments, but a few groups have adapted to life on land, such as terrestrial crabs, terrestrial hermit crabs, and woodlice. Marine crustaceans are as ubiquitous in the oceans as insects are on land.[24][25] Most crustaceans are also motile, moving about independently, although a few taxonomic units are parasitic and live attached to their hosts (including sea lice, fish lice, whale lice, tongue worms, and Cymothoa exigua, all of which may be referred to as "crustacean lice"), and adult barnacles live a sessile life – they are attached headfirst to the substrate and cannot move independently. Some branchiurans are able to withstand rapid changes of salinity and will also switch hosts from marine to non-marine species.[26]: 672 Krill are the bottom layer and most important part of the food chain in Antarctic animal communities.[27]: 64 Some crustaceans are significant invasive species, such as the Chinese mitten crab, Eriocheir sinensis,[28] and the Asian shore crab, Hemigrapsus sanguineus.[29] Since the opening of the Suez Canal, close to 100 species of crustaceans from the Red Sea and the Indo-Pacific realm have established themselves in the eastern Mediterranean sub-basin, with often significant impact on local ecosystems.[30]

Life cycle

[edit]

Mating system

[edit]Most crustaceans have separate sexes, and reproduce sexually. In fact, a recent study explains how the male T. californicus decide which females to mate with by dietary differences, preferring when the females are algae-fed instead of yeast-fed.[31] A small number are hermaphrodites, including barnacles, remipedes,[32] and Cephalocarida.[33] Some may even change sex during the course of their life.[33] Parthenogenesis is also widespread among crustaceans, where viable eggs are produced by a female without needing fertilisation by a male.[31] This occurs in many branchiopods, some ostracods, some isopods, and certain "higher" crustaceans, such as the Marmorkrebs crayfish.

Eggs

[edit]In many crustaceans, the fertilised eggs are released into the water column, while others have developed a number of mechanisms for holding on to the eggs until they are ready to hatch. Most decapods carry the eggs attached to the pleopods, while peracarids, notostracans, anostracans, and many isopods form a brood pouch from the carapace and thoracic limbs.[31] Female Branchiura do not carry eggs in external ovisacs but attach them in rows to rocks and other objects.[34]: 788 Most leptostracans and krill carry the eggs between their thoracic limbs; some copepods carry their eggs in special thin-walled sacs, while others have them attached together in long, tangled strings.[31]

Larvae

[edit]Crustaceans exhibit a number of larval forms, of which the earliest and most characteristic is the nauplius. This has three pairs of appendages, all emerging from the young animal's head, and a single naupliar eye. In most groups, there are further larval stages, including the zoea (pl. zoeæ or zoeas[35]). This name was given to it when naturalists believed it to be a separate species.[36] It follows the nauplius stage and precedes the post-larva. Zoea larvae swim with their thoracic appendages, as opposed to nauplii, which use cephalic appendages, and megalopa, which use abdominal appendages for swimming. It often has spikes on its carapace, which may assist these small organisms in maintaining directional swimming.[37] In many decapods, due to their accelerated development, the zoea is the first larval stage. In some cases, the zoea stage is followed by the mysis stage, and in others, by the megalopa stage, depending on the crustacean group involved.

Providing camouflage against predators, the otherwise black eyes in several forms of swimming larvae are covered by a thin layer of crystalline isoxanthopterin that gives their eyes the same color as the surrounding water, while tiny holes in the layer allow light to reach the retina.[38] As the larvae mature into adults, the layer migrates to a new position behind the retina where it works as a backscattering mirror that increases the intensity of light passing through the eyes, as seen in many nocturnal animals.[39]

DNA repair

[edit]In an effort to understand whether DNA repair processes can protect crustaceans against DNA damage, basic research was conducted to elucidate the repair mechanisms used by Penaeus monodon (black tiger shrimp).[40] Repair of DNA double-strand breaks was found to be predominantly carried out by accurate homologous recombinational repair. Another, less accurate process, microhomology-mediated end joining, is also used to repair such breaks. The expression pattern of DNA repair related and DNA damage response genes in the intertidal copepod Tigriopus japonicus was analyzed after ultraviolet irradiation.[41] This study revealed increased expression of proteins associated with the DNA repair processes of non-homologous end joining, homologous recombination, base excision repair and DNA mismatch repair.

Classification and phylogeny

[edit]

The name "crustacean" dates from the earliest works to describe the animals, including those of Pierre Belon and Guillaume Rondelet, but the name was not used by some later authors, including Carl Linnaeus, who included crustaceans among the "Aptera" in his Systema Naturae.[42] The earliest nomenclatural valid work to use the name "Crustacea" was Morten Thrane Brünnich's Zoologiæ Fundamenta in 1772,[43] although he also included chelicerates in the group.[42]

The subphylum Crustacea comprises almost 67,000 described species,[44] which is thought to be just 1⁄10 to 1⁄100 of the total number as most species remain as yet undiscovered.[45] Although most crustaceans are small, their morphology varies greatly and includes both the largest arthropod in the world – the Japanese spider crab with a leg span of 3.7 metres (12 ft)[46] – and the smallest, the 100-micrometre-long (0.004 in) Stygotantulus stocki.[47] Despite their diversity of form, crustaceans are united by the special larval form known as the nauplius.

The exact relationships of the Crustacea to other taxa are not completely settled as of April 2012[update]. Studies based on morphology led to the Pancrustacea hypothesis,[48] in which Crustacea and Hexapoda (insects and allies) are sister groups. More recent studies using DNA sequences suggest that Crustacea is paraphyletic, with the hexapods nested within a larger Pancrustacea clade.[49][50]

The traditional classification of Crustacea based on morphology recognised four to six classes.[51] Bowman and Abele (1982) recognised 652 extant families and 38 orders, organised into six classes: Branchiopoda, Remipedia, Cephalocarida, Maxillopoda, Ostracoda, and Malacostraca.[51] Martin and Davis (2001) updated this classification, retaining the six classes but including 849 extant families in 42 orders. Despite outlining the evidence that Maxillopoda was non-monophyletic, they retained it as one of the six classes, although did suggest that Maxillipoda could be replaced by elevating its subclasses to classes.[52] Since then phylogenetic studies have confirmed the polyphyly of Maxillopoda and the paraphyletic nature of Crustacea with respect to Hexapoda.[53][54][55][56] Recent classifications recognise ten to twelve classes in Crustacea or Pancrustacea, with several former maxillopod subclasses now recognised as classes (e.g. Thecostraca, Tantulocarida, Mystacocarida, Copepoda, Branchiura and Pentastomida).[57][58]

The following cladogram shows the updated relationships between the different extant groups of the paraphyletic Crustacea in relation to the class Hexapoda.[54]

| Pancrustacea | Crustacea | |

According to this diagram, the Hexapoda are deep in the Crustacea tree, and any of the Hexapoda is distinctly closer to e.g. a Multicrustacean than an Oligostracan is.

Fossil record

[edit]

Crustaceans have a rich and extensive fossil record, most of the major groups of crustaceans appear in the fossil record before the end of the Cambrian, namely the Branchiopoda, Maxillopoda (including barnacles and tongue worms) and Malacostraca; there is some debate as to whether or not Cambrian animals assigned to Ostracoda are truly ostracods, which would otherwise start in the Ordovician.[59] The only classes to appear later are the Cephalocarida,[60] which have no fossil record, and the Remipedia, which were first described from the fossil Tesnusocaris goldichi, but do not appear until the Carboniferous.[61] Most of the early crustaceans are rare, but fossil crustaceans become abundant from the Carboniferous period onwards.[62]

Within the Malacostraca, no fossils are known for krill,[63] while both Hoplocarida and Phyllopoda contain important groups that are now extinct as well as extant members (Hoplocarida: mantis shrimp are extant, while Aeschronectida are extinct;[64] Phyllopoda: Canadaspidida are extinct, while Leptostraca are extant).[65] Cumacea and Isopoda are both known from the Carboniferous,[66][67] as are the first true mantis shrimp.[68] In the Decapoda, prawns and polychelids appear in the Triassic,[69][70] and shrimp and crabs appear in the Jurassic.[71][72] The fossil burrow Ophiomorpha is attributed to ghost shrimps, whereas the fossil burrow Camborygma is attributed to crayfishes. The Permian–Triassic deposits of Nurra preserve the oldest (Permian: Roadian) fluvial burrows ascribed to ghost shrimps (Decapoda: Axiidea, Gebiidea) and crayfishes (Decapoda: Astacidea, Parastacidea), respectively.[73]

However, the great radiation of crustaceans occurred in the Cretaceous, particularly in crabs, and may have been driven by the adaptive radiation of their main predators, bony fish.[72] The first true lobsters also appear in the Cretaceous.[74]

Consumption by humans

[edit]

Many crustaceans are consumed by humans, and nearly 10,700,000 tons were harvested in 2007; the vast majority of this output is of decapod crustaceans: crabs, lobsters, shrimp, crawfish, and prawns.[75] Over 60% by weight of all crustaceans caught for consumption are shrimp and prawns, and nearly 80% is produced in Asia, with China alone producing nearly half the world's total.[75] Non-decapod crustaceans are not widely consumed, with only 118,000 tons of krill being caught,[75] despite krill having one of the greatest biomasses on the planet.[76]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Frederick Schram (1979). "British Carboniferous Malacostraca". Fieldiana Geology. 40.

- ^ Calman, William Thomas (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 552.

- ^ Rota-Stabelli, Omar; Kayal, Ehsan; Gleeson, Dianne; et al. (2010). "Ecdysozoan Mitogenomics: Evidence for a Common Origin of the Legged Invertebrates, the Panarthropoda". Genome Biology and Evolution. 2: 425–440. doi:10.1093/gbe/evq030. PMC 2998192. PMID 20624745.

- ^ Koenemann, Stefan; Jenner, Ronald A.; Hoenemann, Mario; et al. (2010-03-01). "Arthropod phylogeny revisited, with a focus on crustacean relationships". Arthropod Structure & Development. 39 (2–3): 88–110. Bibcode:2010ArtSD..39...88K. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2009.10.003. ISSN 1467-8039. PMID 19854296.

- ^ "The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2018 – Meeting the sustainable development goals" (PDF). fao.org. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2018.

- ^ a b "Cephalon". Crustacean Glossary. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ a b "Thorax". Crustacean Glossary. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ a b "Abdomen". Crustacean Glossary. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ "Cephalothorax". Crustacean Glossary. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ "Carapace". Crustacean Glossary. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ P. J. Hayward; J. S. Ryland (1995). Handbook of the marine fauna of north-west Europe. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-854055-7. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ Fritsch, Martin; Richter, Stefan (September 5, 2022). "How body patterning might have worked in the evolution of arthropods—A case study of the mystacocarid Derocheilocaris remanei (Crustacea, Oligostraca)". Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution. 338 (6): 342–359. Bibcode:2022JEZB..338..342F. doi:10.1002/jez.b.23140. PMID 35486026. S2CID 248430846.

- ^ Morphology of the brain in Hutchinsoniella macracantha (Cephalocarida, Crustacea) – page 290

- ^ "Telson". Crustacean Glossary. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ Elizabeth Pennisi (July 4, 1997). "Crab legs and lobster claws". Science. 277 (5322): 36. doi:10.1126/science.277.5322.36. S2CID 83148200.

- ^ "Antennule". Crustacean Glossary. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Archived from the original on 2013-11-05. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ "Crustaceamorpha: appendages". University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ N. C. Hughes (February 2003). "Trilobite tagmosis and body patterning from morphological and developmental perspectives". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 43 (1): 185–206. doi:10.1093/icb/43.1.185. PMID 21680423.

- ^ Akira Sakurai. "Closed and Open Circulatory System". Georgia State University. Archived from the original on 2016-09-17. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ Klaus Urich (1994). "Respiratory pigments". Comparative Animal Biochemistry. Springer. pp. 249–287. ISBN 978-3-540-57420-0.

- ^ H. J. Ceccaldi. Anatomy and physiology of digestive tract of Crustaceans Decapods reared in aquaculture (PDF). AQUACOP, IFREMER. Actes de Colloque 9. pp. 243–259.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)[permanent dead link] - ^ Ghiselin, Michael T. (2005). "Crustacean". Encarta. Microsoft.

- ^ Burkenroad, M. D. (1963). "The evolution of the Eucarida (Crustacea, Eumalacostraca), in relation to the fossil record". Tulane Studies in Geology. 2 (1): 1–17.

- ^ "Crabs, lobsters, prawns and other crustaceans". Australian Museum. January 5, 2010. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ "Benthic animals". Icelandic Ministry of Fisheries and Agriculture. Archived from the original on 2014-05-11. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ Alan P. Covich; James H. Thorp (1991). "Crustacea: Introduction and Peracarida". In James H. Thorp; Alan P. Covich (eds.). Ecology and Classification of North American Freshwater Invertebrates (1st ed.). Academic Press. pp. 665–722. ISBN 978-0-12-690645-5. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ Virtue, P. D.; Nichols, P. D.; Nicols, S. (1997). "Dietary-related mechanisms of survival in Euphasia superba: biochemical changes during long term starvation and bacteria as a possible source of nutrition.". In Bruno Battaglia; Valencia, José; Walton, D. W. H. (eds.). Antarctic communities: species, structure, and survival. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-48033-8. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ Gollasch, Stephan (October 30, 2006). "Eriocheir sinensis" (PDF). Global Invasive Species Database. Invasive Species Specialist Group. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-12-24. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ John J. McDermott (1999). "The western Pacific brachyuran Hemigrapsus sanguineus (Grapsidae) in its new habitat along the Atlantic coast of the United States: feeding, cheliped morphology and growth". In Schram, Frederick R.; Klein, J. C. von Vaupel (eds.). Crustaceans and the biodiversity crisis: Proceedings of the Fourth International Crustacean Congress, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, July 20–24, 1998. Koninklijke Brill. pp. 425–444. ISBN 978-90-04-11387-9. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ Galil, Bella; Froglia, Carlo; Noël, Pierre (2002). Briand, Frederic (ed.). CIESM Atlas of Exotic Species in the Mediterranean: Vol 2 Crustaceans. Paris, Monaco: CIESM Publishers. p. 192. ISBN 92-990003-2-8.

- ^ a b c d "Crustacean (arthropod)". Encyclopædia Britannica. 5 May 2023.

- ^ G. L. Pesce. "Remipedia Yager, 1981".

- ^ a b D. E. Aiken; V. Tunnicliffe; C. T. Shih; L. D. Delorme. "Crustacean". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2011-06-07. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ Alan P. Covich; James H. Thorp (2001). "Introduction to the Subphylum Crustacea". In James H. Thorp; Alan P. Covich (eds.). Ecology and classification of North American freshwater invertebrates (2nd ed.). Academic Press. pp. 777–798. ISBN 978-0-12-690647-9. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ "Zoea". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Calman, William Thomas (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 356.

- ^ W. F. R. Weldon (July 1889). "Note on the function of the spines of the Crustacean zoœa" (PDF). Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 1 (2): 169–172. Bibcode:1889JMBUK...1..169W. doi:10.1017/S0025315400057994. S2CID 54759780. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-17.

- ^ Shavit, Keshet, et al, A tunable reflector enabling crustaceans to see but not be seen, Science, February 16, 2023, and published in volume 379, issue 6633, February 17, 2023

- ^ Duff, Meg (February 16, 2023). ""Disco Eye-Glitter" Makes Baby Crustaceans Invisible". Slate – via slate.com.

- ^ Srivastava, Shikha; Dahal, Sumedha; Naidu, Sharanya J.; Anand, Deepika; Gopalakrishnan, Vidya; Kooloth Valappil, Rajendran; Raghavan, Sathees C. (24 January 2017). "DNA double-strand break repair in Penaeus monodon is predominantly dependent on homologous recombination". DNA Research. 24 (2): 117–128. doi:10.1093/dnares/dsw059. PMC 5397610. PMID 28431013.

- ^ Rhee, J. S.; Kim, B. M.; Choi, B. S.; Lee, J. S. (2012). "Expression pattern analysis of DNA repair-related and DNA damage response genes revealed by 55K oligomicroarray upon UV-B irradiation in the intertidal copepod, Tigriopus japonicus". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. Toxicology & Pharmacology. 155 (2): 359–368. doi:10.1016/j.cbpc.2011.10.005. PMID 22051804.

- ^ a b Lipke B. Holthuis (1991). "Introduction". Marine Lobsters of the World. FAO Species Catalogue, Volume 13. Food and Agriculture Organization. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-92-5-103027-1.[permanent dead link]

- ^ M. T. Brünnich (1772). Zoologiæ fundamenta prælectionibus academicis accomodata. Grunde i Dyrelaeren (in Latin and Danish). Copenhagen & Leipzig: Fridericus Christianus Pelt. pp. 1–254.

- ^ Zhi-Qiang Zhang (2011). Z.-Q. Zhang (ed.). "Animal biodiversity: an outline of higher-level classification and survey of taxonomic richness - Phylum Arthropoda von Siebold, 1848" (PDF). Zootaxa. 4138: 99–103.

- ^ "Crustaceans — bugs of the sea". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ "Japanese Spider Crabs Arrive at Aquarium". Oregon Coast Aquarium. Archived from the original on 2010-03-23. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ Craig R. McClain; Alison G. Boyer (June 22, 2009). "Biodiversity and body size are linked across metazoans". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 276 (1665): 2209–2215. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0245. PMC 2677615. PMID 19324730.

- ^ J. Zrzavý; P. Štys (May 1997). "The basic body plan of arthropods: insights from evolutionary morphology and developmental biology". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 10 (3): 353–367. doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.1997.10030353.x. S2CID 84906139.

- ^ Jerome C. Regier; Jeffrey W. Shultz; Andreas Zwick; April Hussey; Bernard Ball; Regina Wetzer; Joel W. Martin; Clifford W. Cunningham (February 25, 2010). "Arthropod relationships revealed by phylogenomic analysis of nuclear protein-coding sequences". Nature. 463 (7284): 1079–1083. Bibcode:2010Natur.463.1079R. doi:10.1038/nature08742. PMID 20147900. S2CID 4427443.

- ^ Björn M. von Reumont; Ronald A. Jenner; Matthew A. Wills; Emiliano Dell'Ampio; Günther Pass; Ingo Ebersberger; Benjamin Meyer; Stefan Koenemann; Thomas M. Iliffe; Alexandros Stamatakis; Oliver Niehuis; Karen Meusemann; Bernhard Misof (March 2012). "Pancrustacean phylogeny in the light of new phylogenomic data: support for Remipedia as the possible sister group of Hexapoda". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 29 (3): 1031–1045. doi:10.1093/molbev/msr270. PMID 22049065.

- ^ a b Joel W. Martin; George E. Davis (2001). An Updated Classification of the Recent Crustacea (PDF). Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. pp. 1–132. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-12. Retrieved 2009-12-14.

- ^ Huys, Rony (2003). "An Updated Classification of the Recent Crustacea". review. Journal of Crustacean Biology. 23 (2): 495–497. Bibcode:2003JCBio..23..495H. doi:10.1163/20021975-99990355.

- ^ Oakley, Todd H.; Wolfe, Joanna M.; Lindgren, Annie R.; Zaharoff, Alexander K. (January 2013). "Phylotranscriptomics to bring the understudied into the fold: monophyletic ostracoda, fossil placement, and pancrustacean phylogeny". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 30 (1): 215–233. doi:10.1093/molbev/mss216. PMID 22977117.

- ^ a b Schwentner, M; Combosch, DJ; Nelson, JP; Giribet, G (2017). "A Phylogenomic Solution to the Origin of Insects by Resolving Crustacean-Hexapod Relationships". Current Biology. 27 (12): 1818–1824.e5. Bibcode:2017CBio...27E1818S. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.05.040. PMID 28602656.

- ^ Lozano-Fernandez, Jesus; Giacomelli, Mattia; Fleming, James F.; Chen, Albert; Vinther, Jakob; Thomsen, Philip Francis; Glenner, Henrik; Palero, Ferran; Legg, David A.; Iliffe, Thomas M.; Pisani, Davide; Olesen, Jørgen (2019). "Pancrustacean Evolution Illuminated by Taxon-Rich Genomic-Scale Data Sets with an Expanded Remipede Sampling". Genome Biology and Evolution. 11 (8): 2055–2070. doi:10.1093/gbe/evz097. PMC 6684935. PMID 31270537.

- ^ Bernot, James P.; Owen, Christopher L.; Wolfe, Joanna M.; Meland, Kenneth; Olesen, Jørgen; Crandall, Keith A. (2023). "Major Revisions in Pancrustacean Phylogeny and Evidence of Sensitivity to Taxon Sampling". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 40 (8) msad175. doi:10.1093/molbev/msad175. PMC 10414812. PMID 37552897.

- ^ Brusca, Richard C. (2016). Invertebrates (3rd ed.). Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates. p. 222. ISBN 978-1-60535-375-3.

- ^ Giribet, G.; Edgecombe, G.D. (2020). The Invertebrate Tree of Life. Princeton University Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-6911-7025-1. Retrieved 27 May 2023.

- ^ Olney, Matthew. "Ostracods". An insight into micropalaeontology. University College, London. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ Hessler, R. R. (1984). "Cephalocarida: living fossil without a fossil record". In N. Eldredge; S. M. Stanley (eds.). Living Fossils. New York: Springer Verlag. pp. 181–186. ISBN 978-3-540-90957-6.

- ^ Koenemann, Stefan; Schram, Frederick R.; Hönemann, Mario; Iliffe, Thomas M. (12 April 2007). "Phylogenetic analysis of Remipedia (Crustacea)". Organisms Diversity & Evolution. 7 (1): 33–51. Bibcode:2007ODivE...7...33K. doi:10.1016/j.ode.2006.07.001.

- ^ "Fossil Record". Fossil Groups: Crustacea. University of Bristol. Archived from the original on 2016-09-07. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ "Antarctic Prehistory". Australian Antarctic Division. July 29, 2008. Archived from the original on September 30, 2009. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- ^ Jenner, Ronald A.; Hof, Cees H. J.; Schram, Frederick R. (1998). "Palaeo- and archaeostomatopods (Hoplocarida: Crustacea) from the Bear Gulch Limestone, Mississippian (Namurian), of central Montana". Contributions to Zoology. 67 (3): 155–186. doi:10.1163/18759866-06703001.

- ^ Briggs, Derek (January 23, 1978). "The morphology, mode of life, and affinities of Canadaspis perfecta (Crustacea: Phyllocarida), Middle Cambrian, Burgess Shale, British Columbia". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 281 (984): 439–487. Bibcode:1978RSPTB.281..439B. doi:10.1098/rstb.1978.0005.

- ^ Schram, Frederick; Hof, Cees H. J.; Mapes, Royal H. & Snowdon, Polly (2003). "Paleozoic cumaceans (Crustacea, Malacostraca, Peracarida) from North America". Contributions to Zoology. 72 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1163/18759866-07201001.

- ^ Schram, Frederick R. (August 28, 1970). "Isopod from the Pennsylvanian of Illinois". Science. 169 (3948): 854–855. Bibcode:1970Sci...169..854S. doi:10.1126/science.169.3948.854. PMID 5432581. S2CID 31851291.

- ^ Hof, Cees H. J. (1998). "Fossil stomatopods (Crustacea: Malacostraca) and their phylogenetic impact". Journal of Natural History. 32 (10 & 11): 1567–1576. Bibcode:1998JNatH..32.1567H. doi:10.1080/00222939800771101.

- ^ Crean, Robert P. D. (November 14, 2004). "Dendrobranchiata". Order Decapoda. University of Bristol. Archived from the original on February 29, 2012. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- ^ Karasawa, Hiroaki; Takahashi, Fumio; Doi, Eiji; Ishida, Hideo (2003). "First notice of the family Coleiidae Van Straelen (Crustacea: Decapoda: Eryonoides) from the upper Triassic of Japan". Paleontological Research. 7 (4): 357–362. Bibcode:2003PalRe...7..357K. doi:10.2517/prpsj.7.357. S2CID 129330859.

- ^ Chace, Fenner A. Jr.; Manning, Raymond B. (1972). "Two new caridean shrimps, one representing a new family, from marine pools on Ascension Island (Crustacea: Decapoda: Natantia)". Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology. 131 (131): 1–18. doi:10.5479/si.00810282.131. S2CID 53067015.

- ^ a b Wägele, J. W. (December 1989). "On the influence of fishes on the evolution of benthic crustaceans". Zeitschrift für Zoologische Systematik und Evolutionsforschung. 27 (4): 297–309. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0469.1989.tb00352.x.

- ^ Baucon, A.; Ronchi, A.; Felletti, F.; Neto de Carvalho, C. (2014). "Evolution of Crustaceans at the edge of the end-Permian crisis: ichnonetwork analysis of the fluvial succession of Nurra (Permian-Triassic, Sardinia, Italy)". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 410: 74. Bibcode:2014PPP...410...74B. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2014.05.034. Archived from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ Tshudy, Dale; Donaldson, W. Steven; Collom, Christopher; et al. (2005). "Hoploparia albertaensis, a new species of clawed lobster (Nephropidae) from the Late Coniacean, shallow-marine Bad Heart Formation of northwestern Alberta, Canada". Journal of Paleontology. 79 (5): 961–968. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2005)079[0961:HAANSO]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 131067067.

- ^ a b c "FIGIS: Global Production Statistics 1950–2007". Food and Agriculture Organization. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ Nicol, Steven; Endo, Yoshinari (1997). Krill Fisheries of the World. Fisheries Technical Paper. Vol. 367. Food and Agriculture Organization. ISBN 978-92-5-104012-6.

Sources

[edit]- Schram, Frederick (1986). Crustaceans. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-503742-5.

- Powers, M., Hill, G., Weaver, R., & Goymann, W. (2020). An experimental test of mate choice for red carotenoid coloration in the marine copepod Tigriopus californicus. Ethology., 126(3), 344–352. An experimental test of mate choice for red carotenoid coloration in the marine copepod Tigriopus californicus

External links

[edit] Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- "Encyclopedia Americana - Wikipedia". Encyclopedia Americana. Vol. 8. 1920.

- Clark, Hubert Lyman; Ingersoll, Ernest (1905). "Crustacea". New International Encyclopedia. Vol. 5.

- Crustacea.net, an online resource on the biology of crustaceans

- Crustacea Archived October 9, 2007, at the Wayback Machine: Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

- Crustacea: Tree of Life Web Project

- The Crustacean Society Archived 2011-11-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Natural History Collections: Crustacea: University of Edinburgh

- Crustaceans (Crustacea) on the shore of Singapore

- Crustacea(crabs, lobsters, shrimps, prawns, barnacles) Archived 2012-01-11 at the Wayback Machine: Biodiversity Explorer

.jpg/250px-Sally_Lightfoot_crab_(4202519454).jpg)

.jpg/2000px-Sally_Lightfoot_crab_(4202519454).jpg)