Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Geography

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Geography |

|---|

|

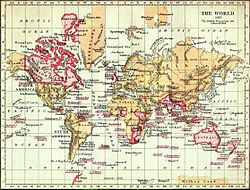

Geography (from Ancient Greek γεωγραφία geōgraphía; combining gê 'Earth' and gráphō 'write', literally 'Earth writing') is the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth.[1][2] Geography is an all-encompassing discipline that seeks an understanding of Earth and its human and natural complexities—not merely where objects are, but also how they have changed and come to be. While geography is specific to Earth, many concepts can be applied more broadly to other celestial bodies in the field of planetary science.[3] Geography has been called "a bridge between natural science and social science disciplines."[4]

Origins of many of the concepts in geography can be traced to Greek Eratosthenes of Cyrene, who may have coined the term "geographia" (c. 276 BC – c. 195/194 BC).[5] The first recorded use of the word γεωγραφία was as the title of a book by Greek scholar Claudius Ptolemy (100 – 170 AD).[1] This work created the so-called "Ptolemaic tradition" of geography, which included "Ptolemaic cartographic theory."[6] However, the concepts of geography (such as cartography) date back to the earliest attempts to understand the world spatially, with the earliest example of an attempted world map dating to the 9th century BCE in ancient Babylon.[7] The history of geography as a discipline spans cultures and millennia, being independently developed by multiple groups, and cross-pollinated by trade between these groups. The core concepts of geography consistent between all approaches are a focus on space, place, time, and scale.[8][9][10][11][12][13] Today, geography is an extremely broad discipline with multiple approaches and modalities. There have been multiple attempts to organize the discipline, including the four traditions of geography, and into branches.[14][4][15] Techniques employed can generally be broken down into quantitative[16] and qualitative[17] approaches, with many studies taking mixed-methods approaches.[18] Common techniques include cartography, remote sensing, interviews, and surveying.

Fundamentals

[edit]

Geography is a systematic study of the Earth (other celestial bodies are specified, such as "geography of Mars", or given another name, such as areography in the case of Mars, or selenography in the case of the Moon, or planetography for the general case), its features, and phenomena that take place on it.[19][20][21] For something to fall into the domain of geography, it generally needs some sort of spatial component that can be placed on a map, such as coordinates, place names, or addresses. This has led to geography being associated with cartography and place names. Although many geographers are trained in toponymy and cartology, this is not their main preoccupation. Geographers study the Earth's spatial and temporal distribution of phenomena, processes, and features as well as the interaction of humans and their environment.[22] Because space and place affect a variety of topics, such as economics, health, climate, plants, and animals, geography is highly interdisciplinary. The interdisciplinary nature of the geographical approach depends on an attentiveness to the relationship between physical and human phenomena and their spatial patterns.[23][24]

While narrowing down geography to a few key concepts is extremely challenging, and subject to tremendous debate within the discipline, several sources have approached the topic.[25] The 1st edition of the book "Key Concepts in Geography" broke down this into chapters focusing on "Space," "Place," "Time," "Scale," and "Landscape."[26] The 2nd edition of the book expanded on these key concepts by adding "Environmental systems," "Social Systems," "Nature," "Globalization," "Development," and "Risk," demonstrating how challenging narrowing the field can be.[25] Another approach used extensively in teaching geography are the Five themes of geography established by "Guidelines for Geographic Education: Elementary and Secondary Schools," published jointly by the National Council for Geographic Education and the Association of American Geographers in 1984.[27][28] These themes are Location, place, relationships within places (often summarized as Human-Environment Interaction), movement, and regions.[28][29] The five themes of geography have shaped how American education approaches the topic in the years since.[28][29]

Space

[edit]

Just as all phenomena exist in time and thus have a history, they also exist in space and have a geography.[30]

For something to exist in the realm of geography, it must be able to be described spatially.[30][31] Thus, space is the most fundamental concept at the foundation of geography.[8][9] The concept is so basic, that geographers often have difficulty defining exactly what it is. Absolute space is the exact site, or spatial coordinates, of objects, persons, places, or phenomena under investigation.[8] We exist in space.[10] Absolute space leads to the view of the world as a photograph, with everything frozen in place when the coordinates were recorded. Today, geographers are trained to recognize the world as a dynamic space where all processes interact and take place, rather than a static image on a map.[8][32]

Place

[edit]

Place is one of the most complex and important terms in geography.[10][11][12][13] In human geography, place is the synthesis of the coordinates on the Earth's surface, the activity and use that occurs, has occurred, and will occur at the coordinates, and the meaning ascribed to the space by human individuals and groups.[31][12] This can be extraordinarily complex, as different spaces may have different uses at different times and mean different things to different people. In physical geography, a place includes all of the physical phenomena that occur in space, including the lithosphere, atmosphere, hydrosphere, and biosphere.[13] Places do not exist in a vacuum and instead have complex spatial relationships with each other, and place is concerned how a location is situated in relation to all other locations.[34][35] As a discipline then, the term place in geography includes all spatial phenomena occurring at a location, the diverse uses and meanings humans ascribe to that location, and how that location impacts and is impacted by all other locations on Earth.[12][13] In one of Yi-Fu Tuan's papers, he explains that in his view, geography is the study of Earth as a home for humanity, and thus place and the complex meaning behind the term is central to the discipline of geography.[11]

Time

[edit]

Time is usually thought to be within the domain of history, however, it is of significant concern in the discipline of geography.[36][37][38] In physics, space and time are not separated, and are combined into the concept of spacetime.[39] Geography is subject to the laws of physics, and in studying things that occur in space, time must be considered. Time in geography is more than just the historical record of events that occurred at various discrete coordinates; but also includes modeling the dynamic movement of people, organisms, and things through space.[10] Time facilitates movement through space, ultimately allowing things to flow through a system.[36] The amount of time an individual, or group of people, spends in a place will often shape their attachment and perspective to that place.[10] Time constrains the possible paths that can be taken through space, given a starting point, possible routes, and rate of travel.[40] Visualizing time over space is challenging in terms of cartography, and includes Space-Prism, advanced 3D geovisualizations, and animated maps.[34][40][41][32]

Scale

[edit]

Scale in the context of a map is the ratio between a distance measured on the map and the corresponding distance as measured on the ground.[3][42] This concept is fundamental to the discipline of geography, not just cartography, in that phenomena being investigated appear different depending on the scale used.[43][44] Scale is the frame that geographers use to measure space, and ultimately to understand a place.[42]

Laws of geography

[edit]During the quantitative revolution, geography shifted to an empirical law-making (nomothetic) approach.[45][46] Several laws of geography have been proposed since then, most notably by Waldo Tobler and can be viewed as a product of the quantitative revolution.[47] In general, some dispute the entire concept of laws in geography and the social sciences.[34][48][49] These criticisms have been addressed by Tobler and others, such as Michael Frank Goodchild.[48][49] However, this is an ongoing source of debate in geography and is unlikely to be resolved anytime soon. Several laws have been proposed, and Tobler's first law of geography is the most generally accepted in geography. Some have argued that geographic laws do not need to be numbered. The existence of a first invites a second, and many have proposed themselves as that. It has also been proposed that Tobler's first law of geography should be moved to the second and replaced with another.[49] A few of the proposed laws of geography are below:

- Tobler's first law of geography: "Everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant."[34][48][49]

- Tobler's second law of geography: "The phenomenon external to a geographic area of interest affects what goes on inside."[48][50]

- Arbia's law of geography: "Everything is related to everything else, but things observed at a coarse spatial resolution are more related than things observed at a finer resolution."[43][48][44][51][52]

- Spatial heterogeneity: Geographic variables exhibit uncontrolled variance.[49][53][54]

- The uncertainty principle: "That the geographic world is infinitely complex and that any representation must therefore contain elements of uncertainty, that many definitions used in acquiring geographic data contain elements of vagueness, and that it is impossible to measure location on the Earth's surface exactly."[49]

Additionally, several variations or amendments to these laws exist within the literature, although not as well supported. For example, one paper proposed an amended version of Tobler's first law of geography, referred to in the text as the Tobler–von Thünen law,[47] which states: "Everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things, as a consequence of accessibility."[47]

Sub-disciplines

[edit]Geography is a branch of inquiry that focuses on spatial information on Earth. It is an extremely broad topic and can be broken down multiple ways.[15] There have been several approaches to doing this spanning at least several centuries, including "four traditions of geography" and into distinct branches.[55][14] The Four traditions of geography are often used to divide the different historical approach theories geographers have taken to the discipline.[14] In contrast, geography's branches describe contemporary applied geographical approaches.[4]

Four traditions

[edit]Geography is an extremely broad field. Because of this, many view the various definitions of geography proposed over the decades as inadequate. To address this, William D. Pattison proposed the concept of the "Four traditions of Geography" in 1964.[14][56][57] These traditions are the Spatial or Locational Tradition, the Man-Land or Human-Environment Interaction Tradition (sometimes referred to as Integrated geography), the Area Studies or Regional Tradition, and the Earth Science Tradition.[14][56][57] These concepts are broad sets of geography philosophies bound together within the discipline. They are one of many ways geographers organize the major sets of thoughts and philosophies within the discipline.[14][56][57]

Branches

[edit]

In another approach to the abovementioned four traditions, geography is organized into applied branches.[58][59] The UNESCO Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems organizes geography into the three categories of human geography, physical geography, and technical geography.[4][60][58][15] Some publications limit the number of branches to physical and human, describing them as the principal branches.[31] Human geography largely focuses on the built environment and how humans create, view, manage, and influence space.[61] Human geographers study people and their communities, cultures, economies, and environmental interactions by studying their relations with and across space and place.[31] Physical geography examines the natural environment and how organisms, climate, soil, water, and landforms produce and interact, studying spatial patterns in the natural environment, atmosphere, hydrosphere, biosphere, and geosphere.[31][62] The difference between these approaches led to the development of integrated geography, which combines physical and human geography and concerns the interactions between the environment and humans.[22] Technical geography involves studying and developing the tools and techniques used by geographers, such as remote sensing, cartography, and geographic information system.[63] Technical geography is interested in studying and applying techniques and methods to store, process, analyze, visualize, and use spatial data.[59] It is the newest of the branches, the most controversial, and often other terms are used in the literature to describe the emerging category. These branches use similar geographic philosophies, concepts, and tools and often overlap significantly. Geographers rarely focus on just one of these topics, often using one as their primary focus and then incorporating data and methods from the other branches. Often, geographers are asked to describe what they do by individuals outside the discipline[11] and are likely to identify closely with a specific branch, or sub-branch when describing themselves to lay people.

Physical

[edit]Physical geography (or physiography) focuses on geography as an Earth science.[64][65][66] It aims to understand the physical problems and the issues of lithosphere, hydrosphere, atmosphere, pedosphere, and global flora and fauna patterns (biosphere). Physical geography is the study of earth's seasons, climate, atmosphere, soil, streams, landforms, and oceans.[67] Physical geographers will often work in identifying and monitoring the use of natural resources.

- Physical geography can be divided into many broad categories, including:

-

Hydrology and hydrography

Human

[edit]Human geography (or anthropogeography) is a branch of geography that focuses on studying patterns and processes that shape human society.[68] It encompasses the human, political, cultural, social, and economic aspects. In industry, human geographers often work in city planning, public health, or business analysis.

- Human geography can be divided into many broad categories, such as:

Various approaches to the study of human geography have also arisen through time and include behavioral geography, culture theory, feminist geography, and geosophy.

Technical

[edit]Technical geography concerns studying and developing tools, techniques, and statistical methods employed to collect, analyze, use, and understand spatial data.[63][4][58][60] Technical geography is the most recently recognized, and controversial, of the branches. Its use dates back to 1749, when a book published by Edward Cave organized the discipline into a section containing content such as cartographic techniques and globes.[55] There are several other terms, often used interchangeably with technical geography to subdivide the discipline, including "techniques of geographic analysis,"[69] "Geographic Information Technology,"[1] "Geography method's and techniques,"[70] "Geographic Information Science,"[71] "geoinformatics," "geomatics," and "information geography". There are subtle differences to each concept and term; however, technical geography is one of the broadest, is consistent with the naming convention of the other two branches, has been in use since the 1700s, and has been used by the UNESCO Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems to divide geography into themes.[4][58][55] As academic fields increasingly specialize in their nature, technical geography has emerged as a branch of geography specializing in geographic methods and thought.[63] The emergence of technical geography has brought new relevance to the broad discipline of geography by serving as a set of unique methods for managing the interdisciplinary nature of the phenomena under investigation. While human and physical geographers use the techniques employed by technical geographers, technical geography is more concerned with the fundamental spatial concepts and technologies than the nature of the data.[63][59] It is therefore closely associated with the spatial tradition of geography while being applied to the other two major branches. A technical geographer might work as a GIS analyst, a GIS developer working to make new software tools, or create general reference maps incorporating human and natural features.[72]

- Technical geography can be divided into many broad categories, such as:

Methods

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2022) |

All geographic research and analysis start with asking the question "where," followed by "why there." Geographers start with the fundamental assumption set forth in Tobler's first law of geography, that "everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things."[34][35] As spatial interrelationships are key to this synoptic science, maps are a key tool. Classical cartography has been joined by a more modern approach to geographical analysis, computer-based geographic information systems (GIS).

In their study, geographers use four interrelated approaches:

- Analytical – Asks why we find features and populations in a specific geographic area.

- Descriptive – Simply specifies the locations of features and populations.

- Regional – Examines systematic relationships between categories for a specific region or location on the planet.

- Systematic – Groups geographical knowledge into categories that can be explored globally.

Quantitative methods

[edit]Quantitative methods in geography became particularly influential in the discipline during the quantitative revolution of the 1950s and 60s.[16] These methods revitalized the discipline in many ways, allowing scientific testing of hypotheses and proposing scientific geographic theories and laws.[73] The quantitative revolution heavily influenced and revitalized technical geography, and lead to the development of the subfield of quantitative geography.[63][16]

Quantitative cartography

[edit]Cartography is the art, science, and technology of making maps.[74] Cartographers study the Earth's surface representation with abstract symbols (map making). Although other subdisciplines of geography rely on maps for presenting their analyses, the actual making of maps is abstract enough to be regarded separately.[75] Cartography has grown from a collection of drafting techniques into an actual science.

Cartographers must learn cognitive psychology and ergonomics to understand which symbols convey information about the Earth most effectively and behavioural psychology to induce the readers of their maps to act on the information. They must learn geodesy and fairly advanced mathematics to understand how the shape of the Earth affects the distortion of map symbols projected onto a flat surface for viewing. It can be said, without much controversy, that cartography is the seed from which the larger field of geography grew.

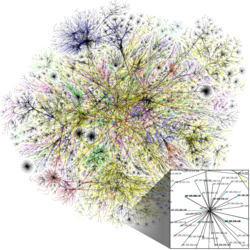

Geographic information systems

[edit]Geographic information systems (GIS) deal with storing information about the Earth for automatic retrieval by a computer in an accurate manner appropriate to the information's purpose.[76] In addition to all of the other subdisciplines of geography, GIS specialists must understand computer science and database systems. GIS has revolutionized the field of cartography: nearly all mapmaking is now done with the assistance of some form of GIS software. The science of using GIS software and GIS techniques to represent, analyse, and predict the spatial relationships is called geographic information science (GISc).[77]

Remote sensing

[edit]

Remote sensing is the art, science, and technology of obtaining information about Earth's features from measurements made at a distance.[78] Remotely sensed data can be either passive, such as traditional photography, or active, such as LiDAR.[78] A variety of platforms can be used for remote sensing, including satellite imagery, aerial photography (including consumer drones), and data obtained from hand-held sensors.[78] Products from remote sensing include Digital elevation model and cartographic base maps. Geographers increasingly use remotely sensed data to obtain information about the Earth's land surface, ocean, and atmosphere, because it: (a) supplies objective information at a variety of spatial scales (local to global), (b) provides a synoptic view of the area of interest, (c) allows access to distant and inaccessible sites, (d) provides spectral information outside the visible portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, and (e) facilitates studies of how features/areas change over time. Remotely sensed data may be analyzed independently or in conjunction with other digital data layers (e.g., in a geographic information system). Remote sensing aids in land use, land cover (LULC) mapping, by helping to determine both what is naturally occurring on a piece of land and what human activities are taking place on it.[79]

Geostatistics

[edit]Geostatistics deal with quantitative data analysis, specifically the application of a statistical methodology to the exploration of geographic phenomena.[80] Geostatistics is used extensively in a variety of fields, including hydrology, geology, petroleum exploration, weather analysis, urban planning, logistics, and epidemiology. The mathematical basis for geostatistics derives from cluster analysis, linear discriminant analysis and non-parametric statistical tests, and a variety of other subjects. Applications of geostatistics rely heavily on geographic information systems, particularly for the interpolation (estimate) of unmeasured points. Geographers are making notable contributions to the method of quantitative techniques.

Qualitative methods

[edit]Qualitative methods in geography are descriptive rather than numerical or statistical in nature.[81][17][45] They add context to concepts, and explore human concepts like beliefs and perspective that are difficult or impossible to quantify.[17] Human geography is much more likely to employ qualitative methods than physical geography. Increasingly, technical geographers are attempting to employ GIS methods to qualitative datasets.[17][82]

Qualitative cartography

[edit]

Qualitative cartography employs many of the same software and techniques as quantitative cartography.[82] It may be employed to inform on map practices, or to visualize perspectives and ideas that are not strictly quantitative in nature.[82][17] An example of a form of qualitative cartography is a Chorochromatic map of nominal data, such as land cover or dominant language group in an area.[83] Another example is a deep map, or maps that combine geography and storytelling to produce a product with greater information than a two-dimensional image of places, names, and topography.[84][85] This approach offers more inclusive strategies than more traditional cartographic approaches for connecting the complex layers that makeup places.[85]

Ethnography

[edit]Ethnographical research techniques are used by human geographers.[86] In cultural geography, there is a tradition of employing qualitative research techniques, also used in anthropology and sociology. Participant observation and in-depth interviews provide human geographers with qualitative data.

Geopoetics

[edit]Geopoetics is an interdisciplinary approach that combines geography and poetry to explore the interconnectedness between humans, space, place, and the environment.[87][88] Geopoetics is employed as a mixed methods tool to explain the implications of geographic research.[89] It is often employed to address and communicate the implications of complex topics, such as the anthropocene.[90][91][92][93][94]

Interviews

[edit]Geographers employ interviews to gather data and acquire valuable understandings from individuals or groups regarding their encounters, outlooks, and opinions concerning spatial phenomena.[95][96] Interviews can be carried out through various mediums, including face-to-face interactions, phone conversations, online platforms, or written exchanges.[45] Geographers typically adopt a structured or semi-structured approach during interviews involving specific questions or discussion points when utilized for research purposes.[95] These questions are designed to extract focused information about the research topic while being flexible enough to allow participants to express their experiences and viewpoints, such as through open-ended questions.[95]

Origin and history

[edit]The concept of geography is present in all cultures, and therefore the history of the discipline is a series of competing narratives, with concepts emerging at various points across space and time.[97] The oldest known world maps date back to ancient Babylon from the 9th century BC.[98] The best known Babylonian world map, however, is the Imago Mundi of 600 BC.[99] The map as reconstructed by Eckhard Unger shows Babylon on the Euphrates, surrounded by a circular landmass showing Assyria, Urartu, and several cities, in turn surrounded by a "bitter river" (Oceanus), with seven islands arranged around it so as to form a seven-pointed star.[100] The accompanying text mentions seven outer regions beyond the encircling ocean. The descriptions of five of them have survived.[101] In contrast to the Imago Mundi, an earlier Babylonian world map dating back to the 9th century BC depicted Babylon as being further north from the center of the world, though it is not certain what that center was supposed to represent.[98]

The ideas of Anaximander (c. 610–545 BC): considered by later Greek writers to be the true founder of geography, come to us through fragments quoted by his successors.[102] Anaximander is credited with the invention of the gnomon, the simple, yet efficient Greek instrument that allowed the early measurement of latitude.[102] Thales is also credited with the prediction of eclipses. The foundations of geography can be traced to ancient cultures, such as the ancient, medieval, and early modern Chinese. The Greeks, who were the first to explore geography as both art and science, achieved this through Cartography, Philosophy, and Literature, or through Mathematics. There is some debate about who was the first person to assert that the Earth is spherical in shape, with the credit going either to Parmenides or Pythagoras. Anaxagoras was able to demonstrate that the profile of the Earth was circular by explaining eclipses. However, he still believed that the Earth was a flat disk, as did many of his contemporaries. One of the first estimates of the radius of the Earth was made by Eratosthenes.[103]

The first rigorous system of latitude and longitude lines is credited to Hipparchus. He employed a sexagesimal system that was derived from Babylonian mathematics. The meridians were subdivided into 360°, with each degree further subdivided into 60 (minutes). To measure the longitude at different locations on Earth, he suggested using eclipses to determine the relative difference in time.[104] The extensive mapping by the Romans as they explored new lands would later provide a high level of information for Ptolemy to construct detailed atlases. He extended the work of Hipparchus, using a grid system on his maps and adopting a length of 56.5 miles for a degree.[105]

From the 3rd century onwards, Chinese methods of geographical study and writing of geographical literature became much more comprehensive than what was found in Europe at the time (until the 13th century).[106] Chinese geographers such as Liu An, Pei Xiu, Jia Dan, Shen Kuo, Fan Chengda, Zhou Daguan, and Xu Xiake wrote important treatises, yet by the 17th century advanced ideas and methods of Western-style geography were adopted in China.[citation needed]

During the Middle Ages, the fall of the Roman empire led to a shift in the evolution of geography from Europe to the Islamic world.[106] Muslim geographers such as Muhammad al-Idrisi produced detailed world maps (such as Tabula Rogeriana), while other geographers such as Yaqut al-Hamawi, Abu Rayhan Biruni, Ibn Battuta, and Ibn Khaldun provided detailed accounts of their journeys and the geography of the regions they visited. Turkish geographer Mahmud al-Kashgari drew a world map on a linguistic basis, and later so did Piri Reis (Piri Reis map). Further, Islamic scholars translated and interpreted the earlier works of the Romans and the Greeks and established the House of Wisdom in Baghdad for this purpose.[107] Abū Zayd al-Balkhī, originally from Balkh, founded the "Balkhī school" of terrestrial mapping in Baghdad.[108] Suhrāb, a late tenth century Muslim geographer accompanied a book of geographical coordinates, with instructions for making a rectangular world map with equirectangular projection or cylindrical equidistant projection.[109]

Abu Rayhan Biruni (976–1048) first described a polar equi-azimuthal equidistant projection of the celestial sphere.[110] He was regarded as the most skilled when it came to mapping cities and measuring the distances between them, which he did for many cities in the Middle East and the Indian subcontinent. He often combined astronomical readings and mathematical equations to develop methods of pin-pointing locations by recording degrees of latitude and longitude. He also developed similar techniques when it came to measuring the heights of mountains, depths of the valleys, and expanse of the horizon. He also discussed human geography and the planetary habitability of the Earth. He also calculated the latitude of Kath, Khwarezm, using the maximum altitude of the Sun, and solved a complex geodesic equation to accurately compute the Earth's circumference, which was close to modern values of the Earth's circumference.[111] His estimate of 6,339.9 km for the Earth radius was only 16.8 km less than the modern value of 6,356.7 km. In contrast to his predecessors, who measured the Earth's circumference by sighting the Sun simultaneously from two different locations, al-Biruni developed a new method of using trigonometric calculations based on the angle between a plain and mountain top, which yielded more accurate measurements of the Earth's circumference, and made it possible for it to be measured by a single person from a single location.[112]

The European Age of Discovery during the 16th and the 17th centuries, where many new lands were discovered and accounts by European explorers such as Christopher Columbus, Marco Polo, and James Cook revived a desire for both accurate geographic detail and more solid theoretical foundations in Europe. In 1650, the first edition of the Geographia Generalis was published by Bernhardus Varenius, which was later edited and republished by others including Isaac Newton.[113][114] This textbook sought to integrate new scientific discoveries and principles into classical geography and approach the discipline like the other sciences emerging, and is seen by some as the division between ancient and modern geography in the West.[113][114]

The Geographia Generalis contained both theoretical background and practical applications related to ship navigation.[114] The remaining problem facing both explorers and geographers was finding the latitude and longitude of a geographic location. While the problem of latitude was solved long ago, but that of longitude remained; agreeing on what zero meridians should be was only part of the problem. It was left to John Harrison to solve it by inventing the chronometer H-4 in 1760, and later in 1884 for the International Meridian Conference to adopt by convention the Greenwich meridian as zero meridians.[111]

The 18th and 19th centuries were the times when geography became recognized as a discrete academic discipline, and became part of a typical university curriculum in Europe (especially Paris and Berlin). The development of many geographic societies also occurred during the 19th century, with the foundations of the Société de Géographie in 1821, the Royal Geographical Society in 1830, Russian Geographical Society in 1845, American Geographical Society in 1851, the Royal Danish Geographical Society in 1876 and the National Geographic Society in 1888.[115] The influence of Immanuel Kant, Alexander von Humboldt, Carl Ritter, and Paul Vidal de la Blache can be seen as a major turning point in geography from philosophy to an academic subject.[116][117][118][119][120] Geographers such as Richard Hartshorne and Joseph Kerski have regarded both Humboldt and Ritter as the founders of modern geography, as Humboldt and Ritter were the first to establish geography as an independent scientific discipline.[121][122]

Over the past two centuries, the advancements in technology with computers have led to the development of geomatics and new practices such as participant observation and geostatistics being incorporated into geography's portfolio of tools. In the West during the 20th century, the discipline of geography went through four major phases: environmental determinism, regional geography, the quantitative revolution, and critical geography. The strong interdisciplinary links between geography and the sciences of geology and botany, as well as economics, sociology, and demographics, have also grown greatly, especially as a result of earth system science that seeks to understand the world in a holistic view. New concepts and philosophies have emerged from the rapid advancement of computers, quantitative methods, and interdisciplinary approaches. The 1962 book Theoretical Geography by William Bunge, which argued for a nomothetic approach to geography and that from a purely spatial perspective there was no real difference between human and physical geography, has been described by Kevin R. Cox as "perhaps the seminal text of the spatial-quantitative revolution."[123][124] In 1970, Waldo Tobler proposed the first law of geography, "everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things."[34][35] This law summarizes the first assumption geographers make about the world.

Related fields

[edit]Geology

[edit]

The discipline of geography, especially physical geography, and geology have significant overlap. In the past, the two have often shared academic departments at universities, a point that has led to conflict over resources.[125] Both disciplines do seek to understand the rocks on the Earth's surface and the processes that change them over time. Geology employs many of the tools and techniques of technical geographers, such as GIS and remote sensing to aid in geological mapping.[126] However, geology includes research that goes beyond the spatial component, such as the chemical analysis of rocks and biogeochemistry.[127]

History

[edit]The discipline of History has significant overlap with geography, especially human geography.[128][129] Like geology, history and geography have shared university departments. Geography provides the spatial context within which historical events unfold.[128] The physical geographic features of a region, such as its landforms, climate, and resources, shape human settlements, trade routes, and economic activities, which in turn influence the course of historical events.[128] Thus, a historian must have a strong foundation in geography.[128][129] Historians employ the techniques of technical geographers to create historical atlases and maps.

Planetary science

[edit]

While the discipline of geography is normally concerned with the Earth, the term can also be informally used to describe the study of other worlds, such as the planets of the Solar System and even beyond.[130] The study of systems larger than the Earth itself usually forms part of Astronomy or Cosmology, while the study of other planets is usually called planetary science. Alternative terms such as areography (geography of Mars) have been employed to describe the study of other celestial objects.[19][20][21] Ultimately, geography may be considered a subdiscipline within planetary science, and planetary science link geography with fields like astronomy and physics.[130]

See also

[edit]- Earth analog – Planet with environment similar to Earth's

- Geologic time scale – System that relates geologic strata to time

- Geophysics – Physics of the Earth and its vicinity

- History of Earth – Overview of Earth's history

- Terrestrial planet – Planet that is composed primarily of silicate rocks or metals

- Theoretical planetology – Scientific modeling of planets

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Dahlman, Carl; Renwick, William (2014). Introduction to Geography: People, Places & Environment (6th ed.). Pearson. ISBN 978-0-13-750451-0.

- ^ Springer, Simon (2017). "Earth Writing". GeoHumanities. 3 (1): 1. doi:10.1080/2373566X.2016.1272431. Retrieved 13 February 2025.

- ^ a b Burt, Tim (2009). Key Concepts in Geography: Scale, Resolution, Analysis, and Synthesis in Physical Geography (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 85–96. ISBN 978-1-4051-9146-3.

- ^ a b c d e f Sala, Maria (2009). Geography Volume I. Oxford, United Kingdom: EOLSS UNESCO. ISBN 978-1-84826-960-6.

- ^ Roller, Duane W. (2010). Eratosthenes' Geography. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-14267-8. Retrieved 29 January 2024.

- ^ Brentjes, Sonja (2009). "Cartography in Islamic Societies". International Encyclopedia of Human Geography. Elsevier. pp. 414–427. ISBN 978-0-08-044911-1. Retrieved 29 January 2024.

- ^ Kurt A. Raaflaub & Richard J. A. Talbert (2009). Geography and Ethnography: Perceptions of the World in Pre-Modern Societies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-4051-9146-3.

- ^ a b c d Thrift, Nigel (2009). Key Concepts in Geography: Space, The Fundamental Stuff of Geography (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 85–96. ISBN 978-1-4051-9146-3.

- ^ a b Kent, Martin (2009). Key Concepts in Geography: Space, Making Room for Space in Physical Geography (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 97–119. ISBN 978-1-4051-9146-3.

- ^ a b c d e Tuan, Yi-Fu (1977). Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-3877-2.

- ^ a b c d Tuan, Yi-Fu (1991). "A View of Geography". Geographical Review. 81 (1): 99–107. Bibcode:1991GeoRv..81...99T. doi:10.2307/215179. JSTOR 215179.

- ^ a b c d Castree, Noel (2009). Key Concepts in Geography: Place, Connections and Boundaries in an Interdependent World (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 85–96. ISBN 978-1-4051-9146-3.

- ^ a b c d Gregory, Ken (2009). Key Concepts in Geography: Place, The Management of Sustainable Physical Environments (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 173–199. ISBN 978-1-4051-9146-3.

- ^ a b c d e f Pattison, William (1964). "The Four Traditions of Geography". Journal of Geography. 63 (5): 211–216. Bibcode:1964JGeog..63..211P. doi:10.1080/00221346408985265.

- ^ a b c Tambassi, Timothy (2021). The Philosophy of Geo-Ontologies (2nd ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-3-030-78144-6.

- ^ a b c Fotheringham, A. Stewart; Brunsdon, Chris; Charlton, Martin (2000). Quantitative Geography: Perspectives on Spatial Data Analysis. Sage Publications Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7619-5948-9.

- ^ a b c d e Burns, Ryan; Skupin, Andre´ (2013). "Towards Qualitative Geovisual Analytics: A Case Study Involving Places, People, and Mediated Experience". Cartographica: The International Journal for Geographic Information and Geovisualization. 48 (3): 157–176. doi:10.3138/carto.48.3.1691. S2CID 3269642. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ Diriwächter, R. & Valsiner, J. (January 2006) Qualitative Developmental Research Methods in Their Historical and Epistemological Contexts. FQS. Vol 7, No. 1, Art. 8

- ^ a b "Areography". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- ^ a b Lowell, Percival (April 1902). "Areography". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 41 (170): 225–234. JSTOR 983554.

- ^ a b Sheehan, William (19 September 2014). "Geography of Mars, or Areography". Camille Flammarion's the Planet Mars. Astrophysics and Space Science Library. Vol. 409. pp. 435–441. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-09641-4_7. ISBN 978-3-319-09640-7.

- ^ a b Hayes-Bohanan, James (29 September 2009). "What is Environmental Geography, Anyway?". webhost.bridgew.edu. Bridgewater State University. Archived from the original on 26 October 2006. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ^ Baker, J.N.L (1963). The History of Geography. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-85328-022-4.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Hornby, William F.; Jones, Melvyn (29 June 1991). An introduction to Settlement Geography. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-28263-5. Archived from the original on 25 December 2016.

- ^ a b Clifford, Nicholas J.; Holloway, Sarah L.; Rice, Stephen P.; Valentine, Gill, eds. (2014). Key Concepts in Geography (2nd ed.). Sage. ISBN 978-1-4129-3022-2. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ^ Holloway, Sarah L.; Rice, Stephen P.; Valentine, Gill, eds. (2003). Key Concepts in Geography (1st ed.). Sage. ISBN 978-0-7619-7389-8.

- ^ Guidelines for Geographic Education: Elementary and Secondary Schools. The Council. 1984. ISBN 978-0-89291-185-1.

- ^ a b c Natoli, Salvatore J. (1 January 1994). "Guidelines for Geographic Education and the Fundamental Themes in Geography". Journal of Geography. 93 (1): 2–6. Bibcode:1994JGeog..93....2N. doi:10.1080/00221349408979676. ISSN 0022-1341.

- ^ a b Buchanan, Lisa Brown; Tschida, Christina M. (2015). "Exploring the five themes of geography using technology". The Ohio Social Studies Review. 52 (1): 29–39.

- ^ a b "Chapter 3: Geography's Perspectives". Rediscovering Geography: New Relevance for Science and Society. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 1997. p. 28. doi:10.17226/4913. ISBN 978-0-309-05199-6. Archived from the original on 7 May 2014. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Matthews, John; Herbert, David (2008). Geography: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-921128-9.

- ^ a b Chen, Xiang; Clark, Jill (2013). "Interactive three-dimensional geovisualization of space-time access to food". Applied Geography. 43: 81–86. Bibcode:2013AppGe..43...81C. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2013.05.012. Retrieved 7 December 2022.

- ^ Tuan, Yi-Fu (1991). "Language and the Making of Place: A Narrative-Descriptive Approach". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 81 (4): 684–696. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1991.tb01715.x.

- ^ a b c d e f Tobler, Waldo (1970). "A Computer Movie Simulating Urban Growth in the Detroit Region" (PDF). Economic Geography. 46: 234–240. doi:10.2307/143141. JSTOR 143141. S2CID 34085823. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 March 2019. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ a b c Tobler, Waldo (2004). "On the First Law of Geography: A Reply". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 94 (2): 304–310. Bibcode:2004AAAG...94..304T. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.2004.09402009.x. S2CID 33201684. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ a b Thrift, Nigel (1977). An Introduction to Time-Geography. Geo Abstracts, University of East Anglia. ISBN 0-90224667-4.

- ^ Thornes, John (2009). Key Concepts in Geography: Time, Change and Stability in Environmental Systems (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 119–139. ISBN 978-1-4051-9146-3.

- ^ Taylor, Peter (2009). Key Concepts in Geography: Time, From Hegemonic Change to Everyday life (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 140–152. ISBN 978-1-4051-9146-3.

- ^ Galison, Peter Louis (1979). "Minkowski's space–time: From visual thinking to the absolute world". Historical Studies in the Physical Sciences. 10: 85–121. doi:10.2307/27757388. JSTOR 27757388.

- ^ a b Miller, Harvey (2017). "Time Geography and Space–Time Prism". International Encyclopedia of Geography. pp. 1–19. doi:10.1002/9781118786352.wbieg0431. ISBN 978-0-470-65963-2.

- ^ Monmonier, Mark (1990). "Strategies For The Visualization Of Geographic Time-Series Data". Cartographica. 27 (1): 30–45. doi:10.3138/U558-H737-6577-8U31. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ a b Herod, Andrew (2009). Key Concepts in Geography: Scale, the local and the global (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 85–96. ISBN 978-1-4051-9146-3.

- ^ a b Arbia, Giuseppe; Benedetti, R.; Espa, G. (1996). ""Effects of MAUP on image classification"". Journal of Geographical Systems. 3: 123–141.

- ^ a b Smith, Peter (2005). "The laws of geography". Teaching Geography. 30 (3): 150. JSTOR 23756334.

- ^ a b c DeLyser, Dydia; Herbert, Steve; Aitken, Stuart; Crang, Mike; McDowell, Linda (November 2009). The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Geography (1st ed.). SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-1-4129-1991-3. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ Yano, Keiji (2001). "GIS and quantitative geography". GeoJournal. 52 (3): 173–180. doi:10.1023/A:1014252827646. S2CID 126943446.

- ^ a b c Walker, Robert Toovey (28 April 2021). "Geography, Von Thünen, and Tobler's first law: Tracing the evolution of a concept". Geographical Review. 112 (4): 591–607. doi:10.1080/00167428.2021.1906670. S2CID 233620037.

- ^ a b c d e Tobler, Waldo (2004). "On the First Law of Geography: A Reply". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 94 (2): 304–310. Bibcode:2004AAAG...94..304T. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.2004.09402009.x. S2CID 33201684. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Goodchild, Michael (2004). "The Validity and Usefulness of Laws in Geographic Information Science and Geography". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 94 (2): 300–303. Bibcode:2004AAAG...94..300G. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.2004.09402008.x. S2CID 17912938.

- ^ Tobler, Waldo (1999). "Linear pycnophylactic reallocation comment on a paper by D. Martin". International Journal of Geographical Information Science. 13 (1): 85–90. Bibcode:1999IJGIS..13...85T. doi:10.1080/136588199241472.

- ^ Hecht, Brent; Moxley, Emily (2009). "Terabytes of Tobler: Evaluating the First Law in a Massive, Domain-Neutral Representation of World Knowledge". Spatial Information Theory. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 5756. Springer. p. 88. Bibcode:2009LNCS.5756...88H. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-03832-7_6. ISBN 978-3-642-03831-0.

- ^ Otto, Philipp; Dogan, Osman; Taspınar, Suleyman (2023). "A Dynamic Spatiotemporal Stochastic Volatility Model with an Application to Environmental Risks". Econometrics and Statistics. arXiv:2211.03178. doi:10.1016/j.ecosta.2023.11.002. S2CID 253384426.

- ^ Zou, Muquan; Wang, Lizhen; Wu, Ping; Tran, Vanha (23 July 2022). "Mining Type-β Co-Location Patterns on Closeness Centrality in Spatial Data Sets". ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 11 (8): 418. Bibcode:2022IJGI...11..418Z. doi:10.3390/ijgi11080418.

- ^ Zhang, Yu; Sheng, Wu; Zhao, Zhiyuan; Yang, Xiping; Fang, Zhixiang (30 January 2023). "An urban crowd flow model integrating geographic characteristics". Scientific Reports. 13 (1): 1695. Bibcode:2023NatSR..13.1695Z. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-29000-5. PMC 9886992. PMID 36717687.

- ^ a b c Cave, Edward (1749). Geography reformed: a new system of general geography, according to an accurate analysis of the science in four parts. The whole illustrated with notes (2nd ed.). London: Edward Cave.

- ^ a b c Robinson, J. Lewis (1976). "A New Look at the Four Traditions of Geography". Journal of Geography. 75 (9): 520–530. Bibcode:1976JGeog..75..520R. doi:10.1080/00221347608980845. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ a b c Murphy, Alexander (27 June 2014). "Geography's Crosscutting Themes: Golden Anniversary Reflections on "The Four Traditions of Geography"". Journal of Geography. 113 (5): 181–188. Bibcode:2014JGeog.113..181M. doi:10.1080/00221341.2014.918639. S2CID 143168559.

- ^ a b c d Sala, Maria (2009). Geography – Vol. I: Geography (PDF). EOLSS UNESCO. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ a b c Dada, Anup (December 2022). "The Process of Geomorphology Related to Sub Branches of Physical Geography". Black Sea Journal of Scientific Research. 59 (3): 1–2. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- ^ a b Ormeling, Ferjan (2009). Geography – Vol. II: Technical Geography Core concepts in the mapping sciences (PDF). EOLSS UNESCO. p. 482. ISBN 978-1-84826-960-6.

- ^ Hough, Carole; Izdebska, Daria (2016). "Names and Geography". In Gammeltoft, Peder (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Names and Naming. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-965643-1.

- ^ Cotterill, Peter D. (1997). "What is geography?". AAG Career Guide: Jobs in Geography and related Geographical Sciences. American Association of Geographers. Archived from the original on 6 October 2006. Retrieved 9 October 2006.

- ^ a b c d e Haidu, Ionel (2016). "What is Technical Geography" (PDF). Geographia Technica. 11 (1): 1–5. doi:10.21163/GT_2016.111.01. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 January 2022. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ "1(b). Elements of Geography". www.physicalgeography.net.

- ^ Pidwirny, Michael; Jones, Scott (1999–2015). "Physical Geography".

- ^ Marsh, William M.; Kaufman, Martin M. (2013). Physical Geography: Great Systems and Global Environments. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-76428-5.

- ^ Lockyer, Norman (1900). "Physiography and Physical Geography". Nature. 63 (1626): 207–208. Bibcode:1900Natur..63..207R. doi:10.1038/063207a0. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ Johnston, Ron (2000). "Human Geography". In Johnston, Ron; Gregory, Derek; Pratt, Geraldine; et al. (eds.). The Dictionary of Human Geography. Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 353–360.

- ^ Getis, Arthur; Bjelland, Mark; Getis, Victoria (2018). Introduction to Geography (15th ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-1-259-57000-1.

- ^ Fundamentals of Physical Geography as a Discipline. New Delhi: National Council of Educational Research and Training. 2006. pp. 1–12. ISBN 81-7450-518-0.

- ^ Lake, Ron; Burggraf, David; Trninic, Milan; Rae, Laurie (2004). Geography Mark-Up Language: Foundation for the Geo-Web. John Wiley and Sons Inc. ISBN 0-470-87154-7.

- ^ Kretzschmar Jr., William A. (24 October 2013). Schlüter, Julia; Krug, Manfred (eds.). Research Methods in Language Variation and Change: Computer mapping of language data. Cambridge University Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-107-46984-6.

- ^ Gregory, Derek; Johnston, Ron; Pratt, Geraldine; Watts, Michael J.; Whatmore, Sarah (2009). The Dictionary of Human Geography (5th ed.). US & UK: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 611–612.

- ^ Kainz, Wolfgang (21 October 2019). "Cartography and the others – aspects of a complicated relationship". Geo-spatial Information Science. 23 (1): 52–60. doi:10.1080/10095020.2020.1718000. S2CID 214162170.

- ^ Jenks, George (December 1953). "An Improved Curriculum for Cartographic Training at the College and University Level". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 43 (2): 317–331. doi:10.2307/2560899. JSTOR 2560899.

- ^ DeMers, Michael (2009). Fundamentals of Geographic Information Systems (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons, inc. ISBN 978-0-470-12906-7.

- ^ Monmonier, Mark (1985). Technological Transition in Cartography. Univ of Wisconsin Pr. ISBN 978-0-299-10070-4.

- ^ a b c Jensen, John (2016). Introductory digital image processing: a remote sensing perspective. Glenview, IL: Pearson Education, Inc. p. 623. ISBN 978-0-13-405816-0.

- ^ Zhang, Chuanrong; Li, Xinba (September 2022). "Land Use and Land Cover Mapping in the Era of Big Data". Land. 11 (10): 1692. Bibcode:2022Land...11.1692Z. doi:10.3390/land11101692.

- ^ Krige, Danie G. (1951). "A statistical approach to some basic mine valuation problems on the Witwatersrand". J. of the Chem., Metal. and Mining Soc. of South Africa 52 (6): 119–139

- ^ Vibha, Pathak; Bijayini, Jena; Sanjay, Kaira (2013). "Qualitative research". Perspect Clin Res. 4 (3): 192. doi:10.4103/2229-3485.115389. PMC 3757586. PMID 24010063.

- ^ a b c Suchan, Trudy; Brewer, Cynthia (2000). "Qualitative Methods for Research on Mapmaking and Map Use". The Professional Geographer. 52 (1): 145–154. Bibcode:2000ProfG..52..145S. doi:10.1111/0033-0124.00212. S2CID 129100721.

- ^ Brewer, Cynthia (1994). "Color use guidelines for mapping and visualization". In MacEachren, A.M.; Taylor, D.R. Fraser (eds.). Visualization in Modern Cartography. Elsevier. pp. 123–134. ISBN 1-4832-8792-0. Retrieved 24 December 2023.

- ^ Bodenhamer, David J.; John Corrigan; Trevor M. Harris. 2015. Deep Maps and Spatial Narratives. Indiana University Press. DOI: 10.2307/j.ctt1zxxzr2

- ^ a b Butts, Shannon; Jones, Madison (20 May 2021). "Deep mapping for environmental communication design". Communication Design Quarterly. 9 (1): 4–19. doi:10.1145/3437000.3437001. S2CID 234794773.

- ^ Cook, Ian; Crang, Phil (1995). Doing Ethnographies.

- ^ Magrane, Eric (2015). "Situating Geopoetics". GeoHumanities. 1 (1): 86–102. doi:10.1080/2373566X.2015.1071674. S2CID 219396902.

- ^ Magrane, Eric; Russo, Linda; de Leeuw, Sarah; Santos Perez, Craig (2019). Geopoetics in Practice (1 ed.). London: Taylor & Francis. doi:10.4324/9780429032202. ISBN 978-0-367-14538-5. S2CID 203499214. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ Magrane, Eric; Johnson, Maria (2017). "An art–science approach to bycatch in the Gulf of California shrimp trawling fishery". Cultural Geographies. 24 (3): 487–495. Bibcode:2017CuGeo..24..487M. doi:10.1177/1474474016684129. S2CID 149158790.

- ^ Magrane, Eric (2021). "Climate geopoetics (the earth is a composted poem)". Dialogues in Human Geography. 11 (1): 8–22. doi:10.1177/2043820620908390. S2CID 213112503. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ Nassar, Aya (2021). "Geopoetics: Storytelling against mastery". Dialogues in Human Geography. 1: 27–30. doi:10.1177/2043820620986397. S2CID 232162263.

- ^ Engelmann, Sasha (2021). "Geopoetics: On organising, mourning, and the incalculable". Dialogues in Human Geography. 11: 31–35. doi:10.1177/2043820620986398. S2CID 232162320.

- ^ Acker, Maleea (2021). "Gesturing toward the common and the desperation: Climate geopoetics' potential". Dialogues in Human Geography. 11 (1): 23–26. doi:10.1177/2043820620986396. S2CID 232162312. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ Cresswell, Tim (2021). "Beyond geopoetics: For hybrid texts". Dialogues in Human Geography. 11: 36–39. doi:10.1177/2043820620986399. hdl:20.500.11820/b64b3dd4-c959-4a8e-877f-85d3058ce4b1. S2CID 232162314.

- ^ a b c Dixon, C.; Leach, B. (1977). Questionnaires and Interviews in Geographical Research (PDF). Geo Abstracts. ISBN 0-902246-97-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 April 2023. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- ^ Dixon, Chris; Leach, Bridget (1984). Survey Research in Underdeveloped Countries (PDF). Geo Books. ISBN 0-86094-135-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 September 2023. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- ^ Heffernan, Mike (2009). Key Concepts in Geography: Histories of Geography (2nd ed.). Sage. pp. 3–20. ISBN 978-1-4129-3022-2.

- ^ a b Raaflaub, Kurt A.; Talbert, Richard J.A. (2009). Geography and Ethnography: Perceptions of the World in Pre-Modern Societies. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4051-9146-3.

- ^ Siebold, Jim (1998). "Babylonian clay tablet, 600 B.C." henry-davis.com. Henry Davis Consulting Inc. Archived from the original on 9 November 2016. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ^ Delano Smith, Catherine (1996). "Imago Mundi's Logo the Babylonian Map of the World". Imago Mundi. 48: 209–211. doi:10.1080/03085699608592846. JSTOR 1151277.

- ^ Finkel, Irving (1995). A join to the map of the world: A notable discovery. British Museum Magazine. ISBN 978-0-7141-2073-7.

- ^ a b Kish, George (1978). A Source Book in Geography. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-82270-2. Archived from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ Tassoul, Jean-Louis; Tassoul, Monique (2004). A Concise History of Solar and Stellar Physics. London: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-11711-9.

- ^ Smith, Sir William (1846). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology: Earinus-Nyx. Vol. 2nd. London: Taylor and Walton. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ Sullivan, Dan (2000). "Mapmaking and its History". rutgers.edu. Rutgers University. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ^ a b Needham, Joseph (1959). Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth. Science and Civilization in China. Vol. 3. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd. ISBN 978-0-521-05801-8. Archived from the original on 25 September 2016.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Nawwab, Ismail I.; Hoye, Paul F.; Speers, Peter C. (5 September 2018). "Islam and Islamic History and The Middle East". islamicity.com. Archived from the original on 17 June 2016. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ^ Edson, Evelyn; Savage-Smith, Emilie (2007). "Medieval Views of the Cosmos". International Journal of the Classical Tradition. 13 (3): 61–63. JSTOR 30222166.

- ^ Tibbetts, Gerald R. (1997). "The Beginnings of a Cartographic Tradition". In Harley, John Brian; Woodward, David (eds.). The history of cartography. Vol. 2. Chicago: Brill. ISBN 0-226-31633-5. Archived from the original on 12 May 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ King, David A. (1996). Rashed, Roshdi (ed.). Astronomy and Islamic society: Qibla, genomics and timekeeping (PDF). Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science. Vol. 1. ISBN 978-0-203-71184-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 November 2016.

- ^ a b Aber, James Sandusky (2003). "Abu Rayhan al-Biruni". academic.emporia.edu. Emporia State University. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ^ Goodman, Lenn Evan (1992). Avicenna. Great Britain: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-01929-3. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

It was Biruni, not Avicenna, who found a way for a single man, at a single moment, to measure the earth's circumference, by trigonometric calculations based on angles measured from a mountaintop and the plain beneath it – thus improving on Eratosthenes' method of sighting the sun simultaneously from two different sites, applied in the ninth century by astronomers of the Khalif al-Ma'mun.

- ^ a b Baker, J. N. L. (1955). "The Geography of Bernhard Varenius". Transactions and Papers (Institute of British Geographers). 21 (21): 51–60. doi:10.2307/621272. JSTOR 621272.

- ^ a b c Warntz, William (1989). "Newton, the Newtonians, and the Geographia Generalis Varenii". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 79 (2): 165–191. doi:10.2307/621272. JSTOR 621272. Retrieved 9 June 2024.

- ^ Livingstone, David N.; Withers, Charles W. J. (15 July 2011). Geographies of Nineteenth-Century Science. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-226-48726-7.

- ^ Société de Géographie (2016). "Société de Géographie, Paris, France" [Who are we ? – Society of Geography]. socgeo.com (in French). Société de Géographie. Archived from the original on 6 November 2016. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ^ "About Us". rgs.org. Royal Geographical Society. Archived from the original on 18 October 2016. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ^ "Русское Географическое Общество (основано в 1845 г.)" [Russian Geographical Society]. rgo.ru (in Russian). Russian Geographical Society. Archived from the original on 24 May 2012. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ^ "History". amergeog.org. The American Geographical Society. Archived from the original on 17 October 2016. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ^ "National Geographic Society". state.gov. U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on 23 December 2019. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ^ Hartshorne, Richard (1939). "The pre-classical period of modern geography". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 29 (3): 35–48. doi:10.1080/00045603909357282 – via Taylor & Francis.

- ^ Kerski, Joseph J. (2016). Interpreting Our World: 100 Discoveries That Revolutionized Geography. ABC-Clio. p. 284. ISBN 978-1-61069-920-4.

- ^ Goodchild, Michael F (2008). "2 Theoretical Geography (1962): William Bunge". In Hubbard, Phil; Kitchin, Rob; Valentine, Gill (eds.). Key Texts in Human Geography. SAGE Publications Ltd. pp. 9–16. ISBN 978-1-4129-2261-6. Retrieved 18 March 2025.

- ^ Cox, Kevin R. (2001). "Bunge, W. 1962: Theoretical geography: Commentary 1". Progress in Human Geography. Classics in human geography revisited. 25 (1): 71–73. doi:10.1191/030913201673714256. Retrieved 18 March 2025.

- ^ Smith, Neil (1987). ""Academic War Over the Field of Geography": The Elimination of Geography at Harvard, 1947-1951". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 77 (2): 155–172. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1987.tb00151.x. JSTOR 2562763. S2CID 145064363.

- ^ Compton, Robert R. (1985). Geology in the field. New York: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-82902-7.

- ^ Gorham, Eville (1 January 1991). "Biogeochemistry: its origins and development". Biogeochemistry. 13 (3): 199–239. Bibcode:1991Biogc..13..199G. doi:10.1007/BF00002942. ISSN 1573-515X. S2CID 128563314.

- ^ a b c d Bryce, James (1902). "The Importance of Geography in Education". The Geographical Journal. 23 (3): 29–32. doi:10.2307/1775737. JSTOR 1775737.

- ^ a b Darby, Henry Clifford (2002). The Relations of History and Geography: Studies in England, France, and the United States. Exeter: University of Exeter Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-85989-699-3.

- ^ a b Kereszturi, Akos; Hyder, David (2012). "Planetary Science in Higher Education: Ideas and Experiences". Journal of Geography in Higher Education. 36 (4) 10.1080/03098265.2012.654466. doi:10.1080/03098265.2012.654466. Retrieved 30 April 2025.

External links

[edit]- Geography at the Encyclopaedia Britannica website

Geography

View on GrokipediaHistorical Foundations

Ancient and Classical Geography

Ancient geography originated in the descriptive accounts of early Greek writers, who integrated travel observations with speculative cosmology. Herodotus (c. 484–425 BC), in his Ἱστορίαι (Histories), offered the first extensive regional descriptions of known lands, dividing the world into three continents—Europe, Asia, and Libya (Africa)—based on Persian Empire territories and emphasizing environmental influences on societies, such as the Nile River's role in shaping Egyptian civilization as a "gift of the river."[7] His work prioritized empirical inquiry from inquiries (historia) over myth, though it included inaccuracies like inflated distances derived from hearsay.[8] Advancements in quantitative geography occurred during the Hellenistic period, notably with Eratosthenes of Cyrene (c. 276–194 BC), who earned the title "Father of Geography" for calculating Earth's circumference around 240 BC. Using the solstice sun's vertical incidence at Syene (modern Aswan) versus a 7.2-degree shadow angle at Alexandria—equivalent to 1/50th of a circle—and a known distance of approximately 5,000 stadia (roughly 800–925 km) between the cities, he estimated the meridian circumference at 252,000 stadia, approximating 39,000–46,000 km, remarkably close to the modern equatorial value of 40,075 km.[9] [10] This method relied on geometric principles and direct observations, demonstrating Earth's sphericity assumed from prior philosophers like Aristotle. Strabo (c. 64 BC–c. 24 AD), a Greco-Roman geographer, compiled the Geographica (c. 7 BC–23 AD), a 17-book encyclopedia synthesizing prior knowledge into regional descriptions of Europe, Asia, and Africa, emphasizing chorography (qualitative regional study) over pure mathematics.[11] He critiqued predecessors like Eratosthenes for errors in distances while advocating geography's utility for statesmanship and history, drawing from periploi (voyage accounts) and official records.[12] Claudius Ptolemy (c. 100–170 AD) advanced mathematical geography in his Geographia (c. 150 AD), cataloging latitudes and longitudes for about 8,000 places using a grid system and conic projections to minimize distortions, enabling world maps from the British Isles to India and Sri Lanka.[13] [14] Though reliant on second-hand data with systematic eastward longitude biases due to incomplete timekeeping, his framework influenced cartography for over a millennium, bridging Greek empiricism with Roman administrative needs.[15] These classical efforts prioritized habitable world's (oikoumene) delineation through observation and deduction, laying foundations for later sciences despite limitations in exploration beyond Eurasia and North Africa.Medieval to Enlightenment Developments

In medieval Europe, geographical representations primarily served theological and symbolic purposes through mappae mundi, such as the Hereford Mappa Mundi created around 1300, which depicted the known world with Jerusalem at the center and oriented east at the top, integrating biblical narratives with rudimentary spatial concepts.[16] These maps prioritized cosmological order over empirical accuracy, reflecting a worldview where geography reinforced Christian doctrine. Concurrently, in the Islamic world, scholars advanced descriptive and cartographic knowledge; Muhammad al-Idrisi, working under Roger II of Sicily, produced the Tabula Rogeriana in 1154, a silver disc map and accompanying text that synthesized traveler reports, Ptolemaic projections, and regional data to portray Europe, Asia, and North Africa with notable precision for the era, remaining the standard reference for three centuries.[17] The Renaissance marked a pivotal shift with the rediscovery and translation of Claudius Ptolemy's Geographia, originally from circa 150 AD, which Byzantine scholar Maximus Planudes recovered in the late 13th century, leading to its Western dissemination by around 1400 and influencing mathematical cartography through latitude-longitude grids and projective techniques.[18] The invention of the printing press around 1450 facilitated the mass production of maps, enabling Gerardus Mercator to develop his conformal projection in 1569 for nautical charting, which preserved angles for accurate rhumb lines, and Abraham Ortelius to compile Theatrum Orbis Terrarum in 1570, the first modern atlas with 53 maps systematically organized by region.[19] [20] Age of Discovery voyages, including Christopher Columbus's 1492 expedition, provided empirical data that corrected Ptolemaic errors and expanded known territories, fostering a transition from speculative to observation-based geography. During the Enlightenment, geography evolved toward systematic scientific inquiry, exemplified by Bernhardus Varenius's Geographia Generalis published in 1650, which delineated general geography—encompassing mathematical principles like sphericity and size calculations—and special geography focused on regional descriptions, establishing foundational dichotomies still influential in the discipline.[21] Immanuel Kant furthered this by delivering lectures on physical geography starting in 1756, delivered nearly 50 times until 1796, emphasizing empirical study of Earth's features, climates, and human distributions as essential for philosophical understanding of nature's laws without unsubstantiated teleology.[22] These works prioritized causal mechanisms and verifiable data over medieval symbolism, laying groundwork for geography's institutionalization as an empirical science.Modern Institutionalization

The institutionalization of geography as a distinct academic discipline emerged in the early 19th century, primarily in German universities, where it transitioned from ancillary studies in history, natural sciences, or theology to dedicated professorships and curricula. Carl Ritter, appointed as the first professor of geography at the University of Berlin in 1820, played a pivotal role by developing systematic regional geography courses that integrated physical and human elements, emphasizing teleological principles of divine order in spatial arrangements.[23] His lectures, attended by hundreds, established geography as a synthetic science bridging natural and moral worlds, influencing subsequent European scholars.[24] Alexander von Humboldt's contemporaneous empirical methodologies, derived from extensive fieldwork and quantitative analysis in works like Kosmos (1845–1862), provided a complementary foundation for physical and systematic geography, though he held no formal academic chair; his ideas promoted observation-based spatial correlations over Ritter's normative framework.[25] This German model spread through the Humboldtian university reforms, which prioritized research and teaching integration, leading to geography chairs at institutions like the University of Bonn (by 1833) and Leipzig.[26] By mid-century, geography gained recognition for practical applications, such as colonial administration and military strategy, prompting state support for its expansion. In Britain, institutionalization lagged until the late 19th century, driven by scholarly societies rather than immediate university departments; the Royal Geographical Society, formalized in 1830, advocated for academic integration, resulting in Oxford's first reader in geography in 1887 and Cambridge's in 1901, often tied to training for empire service.[27] The United States followed suit, with the first standalone geography department established at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1898, influenced by European models and figures like William Morris Davis, who introduced geomorphology at Harvard in the 1880s.[28] Professional associations, such as the American Geographical Society (founded 1851), further solidified the discipline by publishing journals and hosting conferences, including the first International Geographical Congress in 1871, which standardized methodologies and curricula.[29] By the early 20th century, geography departments proliferated across Europe and North America, with over 20 in German universities by 1914, reflecting its utility in education reforms emphasizing spatial literacy for national development.[30] This era marked geography's shift toward professionalization, evidenced by dedicated journals like Geographische Zeitschrift (1899), though debates persisted over its chorological versus idiographic orientations.[31]20th-Century Shifts and Quantitative Revolution

In the early decades of the 20th century, geography largely adhered to a regional paradigm emphasizing areal differentiation, as articulated by Richard Hartshorne in his 1939 work The Nature of Geography, which prioritized descriptive synthesis of unique place-specific characteristics over generalizable laws.[32] This idiographic approach, rooted in German traditions, dominated academic departments but faced criticism for lacking predictive power and scientific rigor, particularly amid post-World War II demands for policy-relevant analysis in urban planning and resource allocation.[32] By the late 1940s, influences from adjacent fields like economics and statistics began eroding this framework, setting the stage for methodological reform.[33] The quantitative revolution emerged in the 1950s, initially in the United States, where geographers at the University of Washington under William Garrison applied statistical techniques to spatial problems, such as transport networks and settlement patterns, marking a pivot toward nomothetic inquiry seeking universal spatial principles.[34] This phase accelerated between 1957 and 1960, driven by access to early computers for data processing and modeling; for instance, Garrison's students, including Brian Berry, developed factorial ecology models analyzing urban structures through multivariate statistics on 1960 U.S. Census data.[33] The approach formalized concepts like Tobler's First Law of Geography (1970), positing that "everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things," enabling empirical testing of distance-decay functions in phenomena such as migration and trade flows.[34] By the 1960s, the revolution gained international traction, exemplified by Peter Haggett's 1965 textbook Locational Analysis in Human Geography, which integrated systems theory, graph theory, and simulation models to dissect spatial organization at multiple scales.[35] Key advancements included gravity models for predicting interaction volumes—I_{ij} = k \cdot (P_i P_j / D_{ij}^b), where P denotes population and D distance, calibrated against real-world freight or retail data—and diffusion models tracing innovation spread, as in Torsten Hägerstrand's 1953 work on agricultural adoption in Sweden using Monte Carlo simulations.[34] Stabilization occurred around 1963, per Ian Burton's assessment, as quantitative methods permeated curricula, elevating geography's status in interdisciplinary applications like operations research for Cold War logistics.[33] While enhancing falsifiability through hypothesis-driven research, this shift abstracted human agency into probabilistic aggregates, prompting later debates on its reductionism despite yielding verifiable predictions in controlled spatial contexts.[32]Core Principles

Space, Place, and Landscape

In geography, space constitutes the fundamental geometric and relational framework for locating and analyzing phenomena on Earth's surface. Absolute space, derived from Newtonian principles, treats space as a fixed, homogeneous container defined by precise coordinates such as latitude and longitude, enabling unambiguous positioning independent of context.[36] Relative space, by contrast, conceptualizes positions dynamically in relation to surrounding features, landmarks, or other locations, incorporating variability from observer perspectives and social interactions.[37] [38] Geographer Yi-Fu Tuan, in his 1977 book Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience, further characterizes experiential space as embodying freedom, openness, and abstract potential, distinct from more constrained human engagements.[39] Place arises when undifferentiated space acquires meaning, identity, and human significance through lived experiences, attachments, and cultural practices. Tuan posits that places form via pauses in movement, where spaces accumulate memories, values, and functions, yielding security and familiarity amid spatial flux.[40] This transformation imbues locales with unique physical attributes—such as terrain or climate—and human elements like architecture or rituals, fostering senses of belonging and distinctiveness.[41] As core organizing concepts alongside environment, space and place underpin geographical inquiry by linking abstract extents to concrete, meaningful sites of interaction.[42] Landscape integrates space and place into the observable surface of Earth, comprising both natural landforms and human-induced modifications. Carl O. Sauer introduced the cultural landscape in 1925 as the natural environment reshaped by a cultural group's activities, technologies, and historical sequences, serving as a tangible record of human adaptation and agency.[43] [44] Landscapes thus manifest spatial patterns and place-specific traits, revealing causal interactions between biophysical conditions and societal processes, such as agricultural terracing in rugged terrains or urban sprawl altering flat plains. This holistic view emphasizes landscapes' dynamic evolution, where empirical observation deciphers underlying geographical laws of form and function.[45]Scale, Spatial Interaction, and Laws