Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Data analysis

View on WikipediaData analysis is the process of inspecting, cleansing, transforming, and modeling data with the goal of discovering useful information, informing conclusions, and supporting decision-making.[1] Data analysis has multiple facets and approaches, encompassing diverse techniques under a variety of names, and is used in different business, science, and social science domains.[2] In today's business world, data analysis plays a role in making decisions more scientific and helping businesses operate more effectively.[3]

Data mining is a particular data analysis technique that focuses on statistical modeling and knowledge discovery for predictive rather than purely descriptive purposes, while business intelligence covers data analysis that relies heavily on aggregation, focusing mainly on business information. In statistical applications, data analysis can be divided into descriptive statistics, exploratory data analysis (EDA), and confirmatory data analysis (CDA).[4] EDA focuses on discovering new features in the data while CDA focuses on confirming or falsifying existing hypotheses.[5] Predictive analytics focuses on the application of statistical models for predictive forecasting or classification, while text analytics applies statistical, linguistic, and structural techniques to extract and classify information from textual sources, a variety of unstructured data. All of the above are varieties of data analysis.[6]

Data analysis process

[edit]

Data analysis is a process for obtaining raw data, and subsequently converting it into information useful for decision-making by users.[1] Statistician John Tukey, defined data analysis in 1961, as:

"Procedures for analyzing data, techniques for interpreting the results of such procedures, ways of planning the gathering of data to make its analysis easier, more precise or more accurate, and all the machinery and results of (mathematical) statistics which apply to analyzing data."[7]

There are several phases, and they are iterative, in that feedback from later phases may result in additional work in earlier phases.[8]

Data requirements

[edit]The data is necessary as inputs to the analysis, which is specified based upon the requirements of those directing the analytics (or customers, who will use the finished product of the analysis).[9] The general type of entity upon which the data will be collected is referred to as an experimental unit (e.g., a person or population of people). Specific variables regarding a population (e.g., age and income) may be specified and obtained. Data may be numerical or categorical (i.e., a text label for numbers).[8]

Data collection

[edit]Data may be collected from a variety of sources.[10] A list of data sources are available for study & research. The requirements may be communicated by analysts to custodians of the data; such as, Information Technology personnel within an organization.[11] Data collection or data gathering is the process of gathering and measuring information on targeted variables in an established system, which then enables one to answer relevant questions and evaluate outcomes. The data may also be collected from sensors in the environment, including traffic cameras, satellites, recording devices, etc. It may also be obtained through interviews, downloads from online sources, or reading documentation.[8]

Data processing

[edit]

Data integration is a precursor to data analysis: Data, when initially obtained, must be processed or organized for analysis. For instance, this may involve placing data into rows and columns in a table format (known as structured data) for further analysis, often through the use of spreadsheet(excel) or statistical software.[8]

Data cleaning

[edit]Once processed and organized, the data may be incomplete, contain duplicates, or contain errors.[12] The need for data cleaning will arise from problems in the way that the data is entered and stored.[12][13] Data cleaning is the process of preventing and correcting these errors. Common tasks include record matching, identifying inaccuracy of data, overall quality of existing data, deduplication, and column segmentation.[14][15]

Such data problems can also be identified through a variety of analytical techniques. For example; with financial information, the totals for particular variables may be compared against separately published numbers that are believed to be reliable.[16] Unusual amounts, above or below predetermined thresholds, may also be reviewed. There are several types of data cleaning that are dependent upon the type of data in the set; this could be phone numbers, email addresses, employers, or other values.[17] Quantitative data methods for outlier detection can be used to get rid of data that appears to have a higher likelihood of being input incorrectly. Text data spell checkers can be used to lessen the amount of mistyped words. However, it is harder to tell if the words are contextually (i.e., semantically and idiomatically) correct.

Exploratory data analysis

[edit]Once the datasets are cleaned, they can then begin to be analyzed using exploratory data analysis. The process of data exploration may result in additional data cleaning or additional requests for data; thus, the initialization of the iterative phases mentioned above.[18] Descriptive statistics, such as the average, median, and standard deviation, are often used to broadly characterize the data.[19][20] Data visualization is also used, in which the analyst is able to examine the data in a graphical format in order to obtain additional insights about messages within the data.[8]

Modeling and algorithms

[edit]Mathematical formulas or models (also known as algorithms), may be applied to the data in order to identify relationships among the variables; for example, checking for correlation and by determining whether or not there is the presence of causality. In general terms, models may be developed to evaluate a specific variable based on other variable(s) contained within the dataset, with some residual error depending on the implemented model's accuracy (e.g., Data = Model + Error).[21]

Inferential statistics utilizes techniques that measure the relationships between particular variables.[22] For example, regression analysis may be used to model whether a change in advertising (independent variable X), provides an explanation for the variation in sales (dependent variable Y), i.e. is Y a function of X? This can be described as (Y = aX + b + error), where the model is designed such that (a) and (b) minimize the error when the model predicts Y for a given range of values of X.[23]

Data product

[edit]A data product is a computer application that takes data inputs and generates outputs, feeding them back into the environment.[24] It may be based on a model or algorithm. For instance, an application that analyzes data about customer purchase history, and uses the results to recommend other purchases the customer might enjoy.[25][8]

Communication

[edit]

Once data is analyzed, it may be reported in many formats to the users of the analysis to support their requirements.[27] The users may have feedback, which results in additional analysis.

When determining how to communicate the results, the analyst may consider implementing a variety of data visualization techniques to help communicate the message more clearly and efficiently to the audience. Data visualization uses information displays (graphics such as, tables and charts) to help communicate key messages contained in the data. Tables are a valuable tool by enabling the ability of a user to query and focus on specific numbers; while charts (e.g., bar charts or line charts), may help explain the quantitative messages contained in the data.[28]

Quantitative messages

[edit]

Stephen Few described eight types of quantitative messages that users may attempt to communicate from a set of data, including the associated graphs.[29][30]

- Time-series: A single variable is captured over a period of time, such as the unemployment rate over a 10-year period. A line chart may be used to demonstrate the trend.

- Ranking: Categorical subdivisions are ranked in ascending or descending order, such as a ranking of sales performance (the measure) by salespersons (the category, with each salesperson a categorical subdivision) during a single period. A bar chart may be used to show the comparison across the salespersons.[31]

- Part-to-whole: Categorical subdivisions are measured as a ratio to the whole (i.e., a percentage out of 100%). A pie chart or bar chart can show the comparison of ratios, such as the market share represented by competitors in a market.[32]

- Deviation: Categorical subdivisions are compared against a reference, such as a comparison of actual vs. budget expenses for several departments of a business for a given time period. A bar chart can show the comparison of the actual versus the reference amount.[33]

- Frequency distribution: Shows the number of observations of a particular variable for a given interval, such as the number of years in which the stock market return is between intervals such as 0–10%, 11–20%, etc. A histogram, a type of bar chart, may be used for this analysis.

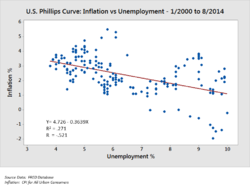

- Correlation: Comparison between observations represented by two variables (X,Y) to determine if they tend to move in the same or opposite directions. For example, plotting unemployment (X) and inflation (Y) for a sample of months. A scatter plot is typically used for this message.[34]

- Nominal comparison: Comparing categorical subdivisions in no particular order, such as the sales volume by product code. A bar chart may be used for this comparison.[35]

- Geographic or geo-spatial: Comparison of a variable across a map or layout, such as the unemployment rate by state or the number of persons on the various floors of a building. A cartogram is typically used.[29]

Analyzing quantitative data in finance

[edit]Author Jonathan Koomey has recommended a series of best practices for understanding quantitative data. These include:[16]

- Check raw data for anomalies prior to performing an analysis;

- Re-perform important calculations, such as verifying columns of data that are formula-driven;

- Confirm main totals are the sum of subtotals;

- Check relationships between numbers that should be related in a predictable way, such as ratios over time;

- Normalize numbers to make comparisons easier, such as analyzing amounts per person or relative to GDP or as an index value relative to a base year;

- Break problems into component parts by analyzing factors that led to the results, such as DuPont analysis of return on equity.

For the variables under examination, analysts typically obtain descriptive statistics, such as the mean (average), median, and standard deviation. They may also analyze the distribution of the key variables to see how the individual values cluster around the mean.[16]

McKinsey and Company named a technique for breaking down a quantitative problem into its component parts called the MECE principle. MECE means "Mutually Exclusive and Collectively Exhaustive".[36] Each layer can be broken down into its components; each of the sub-components must be mutually exclusive of each other and collectively add up to the layer above them. For example, profit by definition can be broken down into total revenue and total cost.[37]

Analysts may use robust statistical measurements to solve certain analytical problems. Hypothesis testing is used when a particular hypothesis about the true state of affairs is made by the analyst and data is gathered to determine whether that hypothesis is true or false.[38] For example, the hypothesis might be that "Unemployment has no effect on inflation", which relates to an economics concept called the Phillips Curve.[39] Hypothesis testing involves considering the likelihood of Type I and type II errors, which relate to whether the data supports accepting or rejecting the hypothesis.[40]

Regression analysis may be used when the analyst is trying to determine the extent to which independent variable X affects dependent variable Y (e.g., "To what extent do changes in the unemployment rate (X) affect the inflation rate (Y)?").[41]

Necessary condition analysis (NCA) may be used when the analyst is trying to determine the extent to which independent variable X allows variable Y (e.g., "To what extent is a certain unemployment rate (X) necessary for a certain inflation rate (Y)?").[41] Whereas (multiple) regression analysis uses additive logic where each X-variable can produce the outcome and the X's can compensate for each other (they are sufficient but not necessary),[42] necessary condition analysis (NCA) uses necessity logic, where one or more X-variables allow the outcome to exist, but may not produce it (they are necessary but not sufficient). Each single necessary condition must be present and compensation is not possible.[43]

Analytical activities of data users

[edit]

Users may have particular data points of interest within a data set, as opposed to the general messaging outlined above. Such low-level user analytic activities are presented in the following table. The taxonomy can also be organized by three poles of activities: retrieving values, finding data points, and arranging data points.[44][45][46]

| # | Task | General description |

Pro forma abstract |

Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Retrieve Value | Given a set of specific cases, find attributes of those cases. | What are the values of attributes {X, Y, Z, ...} in the data cases {A, B, C, ...}? | - What is the mileage per gallon of the Ford Mondeo?

- How long is the movie Gone with the Wind? |

| 2 | Filter | Given some concrete conditions on attribute values, find data cases satisfying those conditions. | Which data cases satisfy conditions {A, B, C...}? | - What Kellogg's cereals have high fiber?

- What comedies have won awards? - Which funds underperformed the SP-500? |

| 3 | Compute Derived Value | Given a set of data cases, compute an aggregate numeric representation of those data cases. | What is the value of aggregation function F over a given set S of data cases? | - What is the average calorie content of Post cereals?

- What is the gross income of all stores combined? - How many manufacturers of cars are there? |

| 4 | Find Extremum | Find data cases possessing an extreme value of an attribute over its range within the data set. | What are the top/bottom N data cases with respect to attribute A? | - What is the car with the highest MPG?

- What director/film has won the most awards? - What Marvel Studios film has the most recent release date? |

| 5 | Sort | Given a set of data cases, rank them according to some ordinal metric. | What is the sorted order of a set S of data cases according to their value of attribute A? | - Order the cars by weight.

- Rank the cereals by calories. |

| 6 | Determine Range | Given a set of data cases and an attribute of interest, find the span of values within the set. | What is the range of values of attribute A in a set S of data cases? | - What is the range of film lengths?

- What is the range of car horsepowers? - What actresses are in the data set? |

| 7 | Characterize Distribution | Given a set of data cases and a quantitative attribute of interest, characterize the distribution of that attribute's values over the set. | What is the distribution of values of attribute A in a set S of data cases? | - What is the distribution of carbohydrates in cereals?

- What is the age distribution of shoppers? |

| 8 | Find Anomalies | Identify any anomalies within a given set of data cases with respect to a given relationship or expectation, e.g. statistical outliers. | Which data cases in a set S of data cases have unexpected/exceptional values? | - Are there exceptions to the relationship between horsepower and acceleration?

- Are there any outliers in protein? |

| 9 | Cluster | Given a set of data cases, find clusters of similar attribute values. | Which data cases in a set S of data cases are similar in value for attributes {X, Y, Z, ...}? | - Are there groups of cereals w/ similar fat/calories/sugar?

- Is there a cluster of typical film lengths? |

| 10 | Correlate | Given a set of data cases and two attributes, determine useful relationships between the values of those attributes. | What is the correlation between attributes X and Y over a given set S of data cases? | - Is there a correlation between carbohydrates and fat?

- Is there a correlation between country of origin and MPG? - Do different genders have a preferred payment method? - Is there a trend of increasing film length over the years? |

| 11 | Contextualization | Given a set of data cases, find contextual relevancy of the data to the users. | Which data cases in a set S of data cases are relevant to the current users' context? | - Are there groups of restaurants that have foods based on my current caloric intake? |

Barriers to effective analysis

[edit]Barriers to effective analysis may exist among the analysts performing the data analysis or among the audience. Distinguishing fact from opinion, cognitive biases, and innumeracy are all challenges to sound data analysis.[47]

Confusing fact and opinion

[edit]You are entitled to your own opinion, but you are not entitled to your own facts.

Effective analysis requires obtaining relevant facts to answer questions, support a conclusion or formal opinion, or test hypotheses.[48] Facts by definition are irrefutable, meaning that any person involved in the analysis should be able to agree upon them. The auditor of a public company must arrive at a formal opinion on whether financial statements of publicly traded corporations are "fairly stated, in all material respects".[49] This requires extensive analysis of factual data and evidence to support their opinion.

Cognitive biases

[edit]There are a variety of cognitive biases that can adversely affect analysis. For example, confirmation bias is the tendency to search for or interpret information in a way that confirms one's preconceptions.[50] In addition, individuals may discredit information that does not support their views.[51]

Analysts may be trained specifically to be aware of these biases and how to overcome them.[52] In his book Psychology of Intelligence Analysis, retired CIA analyst Richards Heuer wrote that analysts should clearly delineate their assumptions and chains of inference and specify the degree and source of the uncertainty involved in the conclusions.[53] He emphasized procedures to help surface and debate alternative points of view.[54]

Innumeracy

[edit]Effective analysts are generally adept with a variety of numerical techniques. However, audiences may not have such literacy with numbers or numeracy; they are said to be innumerate.[55] Persons communicating the data may also be attempting to mislead or misinform, deliberately using bad numerical techniques.[56]

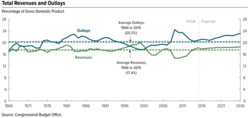

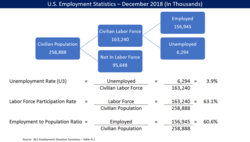

For example, whether a number is rising or falling may not be the key factor. More important may be the number relative to another number, such as the size of government revenue or spending relative to the size of the economy (GDP) or the amount of cost relative to revenue in corporate financial statements.[57] This numerical technique is referred to as normalization[16] or common-sizing. There are many such techniques employed by analysts, whether adjusting for inflation (i.e., comparing real vs. nominal data) or considering population increases, demographics, etc.[58]

Analysts may also analyze data under different assumptions or scenarios. For example, when analysts perform financial statement analysis, they will often recast the financial statements under different assumptions to help arrive at an estimate of future cash flow, which they then discount to present value based on some interest rate, to determine the valuation of the company or its stock.[59] Similarly, the CBO analyzes the effects of various policy options on the government's revenue, outlays and deficits, creating alternative future scenarios for key measures.[60]

Other applications

[edit]Analytics and business intelligence

[edit]Analytics is the "extensive use of data, statistical and quantitative analysis, explanatory and predictive models, and fact-based management to drive decisions and actions." It is a subset of business intelligence, which is a set of technologies and processes that uses data to understand and analyze business performance to drive decision-making.[61]

Education

[edit]In education, most educators have access to a data system for the purpose of analyzing student data.[62] These data systems present data to educators in an over-the-counter data format (embedding labels, supplemental documentation, and a help system and making key package/display and content decisions) to improve the accuracy of educators' data analyses.[63]

Practitioner notes

[edit]This section contains rather technical explanations that may assist practitioners but are beyond the typical scope of a Wikipedia article.[64]

Initial data analysis

[edit]The most important distinction between the initial data analysis phase and the main analysis phase is that during initial data analysis one refrains from any analysis that is aimed at answering the original research question. The initial data analysis phase is guided by the following four questions:[65]

Quality of data

[edit]The quality of the data should be checked as early as possible. Data quality can be assessed in several ways, using different types of analysis: frequency counts, descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, median), normality (skewness, kurtosis, frequency histograms), normal imputation is needed.[66]

- Analysis of extreme observations: outlying observations in the data are analyzed to see if they seem to disturb the distribution.[67]

- Comparison and correction of differences in coding schemes: variables are compared with coding schemes of variables external to the data set, and possibly corrected if coding schemes are not comparable.[68]

- Test for common-method variance. The choice of analyses to assess the data quality during the initial data analysis phase depends on the analyses that will be conducted in the main analysis phase.[69]

Quality of measurements

[edit]The quality of the measurement instruments should only be checked during the initial data analysis phase when this is not the focus or research question of the study.[70] One should check whether structure of measurement instruments corresponds to structure reported in the literature.

There are two ways to assess measurement quality:

- Confirmatory factor analysis

- Analysis of homogeneity (internal consistency), which gives an indication of the reliability of a measurement instrument.[71] During this analysis, one inspects the variances of the items and the scales, the Cronbach's α of the scales, and the change in the Cronbach's alpha when an item would be deleted from a scale[72]

Initial transformations

[edit]After assessing the quality of the data and of the measurements, one might decide to impute missing data, or to perform initial transformations of one or more variables, although this can also be done during the main analysis phase.[73]

Possible transformations of variables are:[74]

- Square root transformation (if the distribution differs moderately from normal)

- Log-transformation (if the distribution differs substantially from normal)

- Inverse transformation (if the distribution differs severely from normal)

- Make categorical (ordinal / dichotomous) (if the distribution differs severely from normal, and no transformations help)

Did the implementation of the study fulfill the intentions of the research design?

[edit]One should check the success of the randomization procedure, for instance by checking whether background and substantive variables are equally distributed within and across groups. If the study did not need or use a randomization procedure, one should check the success of the non-random sampling, for instance by checking whether all subgroups of the population of interest are represented in the sample.[75]

Other possible data distortions that should be checked are:

- dropout (this should be identified during the initial data analysis phase)

- Item non-response (whether this is random or not should be assessed during the initial data analysis phase)

- Treatment quality (using manipulation checks).[76]

Characteristics of data sample

[edit]In any report or article, the structure of the sample must be accurately described. It is especially important to exactly determine the size of the subgroup when subgroup analyses will be performed during the main analysis phase.[77]

The characteristics of the data sample can be assessed by looking at:

- Basic statistics of important variables

- Scatter plots

- Correlations and associations

- Cross-tabulations[78]

Final stage of the initial data analysis

[edit]During the final stage, the findings of the initial data analysis are documented, and necessary, preferable, and possible corrective actions are taken. Also, the original plan for the main data analyses can and should be specified in more detail or rewritten. In order to do this, several decisions about the main data analyses can and should be made:

- In the case of non-normals: should one transform variables; make variables categorical (ordinal/dichotomous); adapt the analysis method?

- In the case of missing data: should one neglect or impute the missing data; which imputation technique should be used?

- In the case of outliers: should one use robust analysis techniques?

- In case items do not fit the scale: should one adapt the measurement instrument by omitting items, or rather ensure comparability with other (uses of the) measurement instrument(s)?

- In the case of (too) small subgroups: should one drop the hypothesis about inter-group differences, or use small sample techniques, like exact tests or bootstrapping?

- In case the randomization procedure seems to be defective: can and should one calculate propensity scores and include them as covariates in the main analyses?[79]

Analysis

[edit]Several analyses can be used during the initial data analysis phase:[80]

- Univariate statistics (single variable)

- Bivariate associations (correlations)

- Graphical techniques (scatter plots)

It is important to take the measurement levels of the variables into account for the analyses, as special statistical techniques are available for each level:[81]

- Nominal and ordinal variables

- Frequency counts (numbers and percentages)

- Associations

- circumambulations (crosstabulations)

- hierarchical loglinear analysis (restricted to a maximum of 8 variables)

- loglinear analysis (to identify relevant/important variables and possible confounders)

- Exact tests or bootstrapping (in case subgroups are small)

- Computation of new variables

- Continuous variables

- Distribution

- Statistics (M, SD, variance, skewness, kurtosis)

- Stem-and-leaf displays

- Box plots

- Distribution

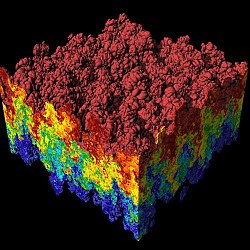

Nonlinear analysis

[edit]Nonlinear analysis is often necessary when the data is recorded from a nonlinear system. Nonlinear systems can exhibit complex dynamic effects including bifurcations, chaos, harmonics and subharmonics that cannot be analyzed using simple linear methods. Nonlinear data analysis is closely related to nonlinear system identification.[82]

Main data analysis

[edit]In the main analysis phase, analyses aimed at answering the research question are performed as well as any other relevant analysis needed to write the first draft of the research report.[83]

Exploratory and confirmatory approaches

[edit]In the main analysis phase, either an exploratory or confirmatory approach can be adopted. Usually the approach is decided before data is collected.[84] In an exploratory analysis no clear hypothesis is stated before analysing the data, and the data is searched for models that describe the data well.[85] In a confirmatory analysis, clear hypotheses about the data are tested.[86]

Exploratory data analysis should be interpreted carefully. When testing multiple models at once there is a high chance on finding at least one of them to be significant, but this can be due to a type 1 error. It is important to always adjust the significance level when testing multiple models with, for example, a Bonferroni correction.[87] Also, one should not follow up an exploratory analysis with a confirmatory analysis in the same dataset.[88] An exploratory analysis is used to find ideas for a theory, but not to test that theory as well.[88] When a model is found exploratory in a dataset, then following up that analysis with a confirmatory analysis in the same dataset could simply mean that the results of the confirmatory analysis are due to the same type 1 error that resulted in the exploratory model in the first place.[88] The confirmatory analysis therefore will not be more informative than the original exploratory analysis.[89]

Stability of results

[edit]It is important to obtain some indication about how generalizable the results are.[90] While this is often difficult to check, one can look at the stability of the results. Are the results reliable and reproducible? There are two main ways of doing that.

- Cross-validation. By splitting the data into multiple parts, we can check if an analysis (like a fitted model) based on one part of the data generalizes to another part of the data as well.[91] Cross-validation is generally inappropriate, though, if there are correlations within the data, e.g. with panel data.[92] Hence other methods of validation sometimes need to be used. For more on this topic, see statistical model validation.[93]

- Sensitivity analysis. A procedure to study the behavior of a system or model when global parameters are (systematically) varied. One way to do that is via bootstrapping.[94]

Free software for data analysis

[edit]Free software for data analysis include:

- DevInfo – A database system endorsed by the United Nations Development Group for monitoring and analyzing human development.[95]

- ELKI – Data mining framework in Java with data mining oriented visualization functions.

- KNIME – The Konstanz Information Miner, a user friendly and comprehensive data analytics framework.

- Orange – A visual programming tool featuring interactive data visualization and methods for statistical data analysis, data mining, and machine learning.

- Pandas – Python library for data analysis.

- PAW – FORTRAN/C data analysis framework developed at CERN.

- R – A programming language and software environment for statistical computing and graphics.[96]

- ROOT – C++ data analysis framework developed at CERN.

- SciPy – Python library for scientific computing.

- Julia – A programming language well-suited for numerical analysis and computational science.

Reproducible analysis

[edit]The typical data analysis workflow involves collecting data, running analyses, creating visualizations, and writing reports. However, this workflow presents challenges, including a separation between analysis scripts and data, as well as a gap between analysis and documentation. Often, the correct order of running scripts is only described informally or resides in the data scientist's memory. The potential for losing this information creates issues for reproducibility.

To address these challenges, it is essential to document analysis script content and workflow. Additionally, overall documentation is crucial, as well as providing reports that are understandable by both machines and humans, and ensuring accurate representation of the analysis workflow even as scripts evolve.[97]

Data analysis contests

[edit]Different companies and organizations hold data analysis contests to encourage researchers to utilize their data or to solve a particular question using data analysis. A few examples of well-known international data analysis contests are:

See also

[edit]- Actuarial science

- Analytics

- Augmented Analytics

- Business intelligence

- Data presentation architecture

- Exploratory data analysis

- List of datasets for machine-learning research

- List of data science software

- Machine learning

- Multiway data analysis

- Qualitative research

- Structured data analysis (statistics)

- Text mining

- Unstructured data

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b "Transforming Unstructured Data into Useful Information", Big Data, Mining, and Analytics, Auerbach Publications, pp. 227–246, 2014-03-12, doi:10.1201/b16666-14, ISBN 978-0-429-09529-0, retrieved 2021-05-29

- ^ "The Multiple Facets of Correlation Functions", Data Analysis Techniques for Physical Scientists, Cambridge University Press, pp. 526–576, 2017, doi:10.1017/9781108241922.013, ISBN 978-1-108-41678-8, retrieved 2021-05-29

- ^ Xia, B. S., & Gong, P. (2015). Review of business intelligence through data analysis. Benchmarking, 21(2), 300-311. doi:10.1108/BIJ-08-2012-0050

- ^ "Data Coding and Exploratory Analysis (EDA) Rules for Data Coding Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) Statistical Assumptions", SPSS for Intermediate Statistics, Routledge, pp. 42–67, 2004-08-16, doi:10.4324/9781410611420-6, ISBN 978-1-4106-1142-0, retrieved 2021-05-29

- ^ Samandar, Petersson; Svantesson, Sofia (2017). Skapandet av förtroende inom eWOM : En studie av profilbildens effekt ur ett könsperspektiv. Högskolan i Gävle, Företagsekonomi. OCLC 1233454128.

- ^ Goodnight, James (2011-01-13). "The forecast for predictive analytics: hot and getting hotter". Statistical Analysis and Data Mining: The ASA Data Science Journal. 4 (1): 9–10. doi:10.1002/sam.10106. ISSN 1932-1864. S2CID 38571193.

- ^ Tukey, John W. (March 1962). "John Tukey-The Future of Data Analysis-July 1961". The Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 33 (1): 1–67. doi:10.1214/aoms/1177704711. Archived from the original on 2020-01-26. Retrieved 2015-01-01.

- ^ a b c d e f Schutt, Rachel; O'Neil, Cathy (2013). Doing Data Science. O'Reilly Media. ISBN 978-1-449-35865-5.

- ^ "USE OF THE DATA", Handbook of Petroleum Product Analysis, Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc, pp. 296–303, 2015-02-06, doi:10.1002/9781118986370.ch18, ISBN 978-1-118-98637-0, retrieved 2021-05-29

- ^ Olusola, Johnson Adedeji; Shote, Adebola Adekunle; Ouigmane, Abdellah; Isaifan, Rima J. (7 May 2021). "Table 1: Data type and sources of data collected for this research". PeerJ. 9: e11387. doi:10.7717/peerj.11387/table-1.

- ^ MacPherson, Derek (2019-10-16), "Information Technology Analysts' Perspectives", Data Strategy in Colleges and Universities, Routledge, pp. 168–183, doi:10.4324/9780429437564-12, ISBN 978-0-429-43756-4, S2CID 211738958, retrieved 2021-05-29

- ^ a b Bohannon, John (2016-02-24). "Many surveys, about one in five, may contain fraudulent data". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aaf4104. ISSN 0036-8075.

- ^ Hancock, R.G.V.; Carter, Tristan (February 2010). "How reliable are our published archaeometric analyses? Effects of analytical techniques through time on the elemental analysis of obsidians". Journal of Archaeological Science. 37 (2): 243–250. Bibcode:2010JArSc..37..243H. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2009.10.004. ISSN 0305-4403.

- ^ "Data Cleaning". Microsoft Research. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- ^ Hellerstein, Joseph (27 February 2008). "Quantitative Data Cleaning for Large Databases" (PDF). EECS Computer Science Division: 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 October 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Perceptual Edge-Jonathan Koomey-Best practices for understanding quantitative data-February 14, 2006" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 5, 2014. Retrieved November 12, 2014.

- ^ Peleg, Roni; Avdalimov, Angelika; Freud, Tamar (2011-03-23). "Providing cell phone numbers and email addresses to Patients: the physician's perspective". BMC Research Notes. 4 (1): 76. doi:10.1186/1756-0500-4-76. ISSN 1756-0500. PMC 3076270. PMID 21426591.

- ^ "FTC requests additional data". Pump Industry Analyst. 1999 (48): 12. December 1999. doi:10.1016/s1359-6128(99)90509-8. ISSN 1359-6128.

- ^ "Exploring your Data with Data Visualization & Descriptive Statistics: Common Descriptive Statistics for Quantitative Data". 2017. doi:10.4135/9781529732795.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Murray, Daniel G. (2013). Tableau your data! : fast and easy visual analysis with Tableau Software. J. Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-61204-0. OCLC 873810654.

- ^ Evans, Michelle V.; Dallas, Tad A.; Han, Barbara A.; Murdock, Courtney C.; Drake, John M. (28 February 2017). Brady, Oliver (ed.). "Figure 2. Variable importance by permutation, averaged over 25 models". eLife. 6: e22053. doi:10.7554/elife.22053.004.

- ^ Watson, Kevin; Halperin, Israel; Aguilera-Castells, Joan; Iacono, Antonio Dello (12 November 2020). "Table 3: Descriptive (mean ± SD), inferential (95% CI) and qualitative statistics (ES) of all variables between self-selected and predetermined conditions". PeerJ. 8: e10361. doi:10.7717/peerj.10361/table-3.

- ^ Nwabueze, JC (2008-05-21). "Performances of estimators of linear model with auto-correlated error terms when the independent variable is normal". Journal of the Nigerian Association of Mathematical Physics. 9 (1). doi:10.4314/jonamp.v9i1.40071. ISSN 1116-4336.

- ^ Conway, Steve (2012-07-04). "A Cautionary Note on Data Inputs and Visual Outputs in Social Network Analysis". British Journal of Management. 25 (1): 102–117. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8551.2012.00835.x. hdl:2381/36068. ISSN 1045-3172. S2CID 154347514.

- ^ "Customer Purchases and Other Repeated Events", Data Analysis Using SQL and Excel®, Indianapolis, Indiana: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp. 367–420, 2016-01-29, doi:10.1002/9781119183419.ch8, ISBN 978-1-119-18341-9, retrieved 2021-05-31

- ^ Grandjean, Martin (2014). "La connaissance est un réseau" (PDF). Les Cahiers du Numérique. 10 (3): 37–54. doi:10.3166/lcn.10.3.37-54. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-09-27. Retrieved 2015-05-05.

- ^ Data requirements for semiconductor die. Exchange data formats and data dictionary, BSI British Standards, doi:10.3403/02271298, retrieved 2021-05-31

- ^ Visualizing Data About UK Museums: Bar Charts, Line Charts and Heat Maps. 2021. doi:10.4135/9781529768749. ISBN 9781529768749. S2CID 240967380.

- ^ a b "Stephen Few-Perceptual Edge-Selecting the Right Graph for Your Message-2004" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-10-05. Retrieved 2014-10-29.

- ^ "Stephen Few-Perceptual Edge-Graph Selection Matrix" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-10-05. Retrieved 2014-10-29.

- ^ Swamidass, P. M. (2000). "X-Bar Chart". Encyclopedia of Production and Manufacturing Management. p. 841. doi:10.1007/1-4020-0612-8_1063. ISBN 978-0-7923-8630-8.

- ^ "Chart C5.3. Percentage of 15-19 year-olds not in education, by labour market status (2012)". doi:10.1787/888933119055. Retrieved 2021-06-03.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Chart 7: Households: final consumption expenditure versus actual individual consumption". doi:10.1787/665527077310. Retrieved 2021-06-03.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Garnier, Elodie M.; Fouret, Nastasia; Descoins, Médéric (3 February 2020). "Table 2: Graph comparison between Scatter plot, Violin + Scatter plot, Heatmap and ViSiElse graph". PeerJ. 8: e8341. doi:10.7717/peerj.8341/table-2.

- ^ "Product comparison chart: Wearables". PsycEXTRA Dataset. 2009. doi:10.1037/e539162010-006. Retrieved 2021-06-03.

- ^ "Consultants Employed by McKinsey & Company", Organizational Behavior 5, Routledge, pp. 77–82, 2008-07-30, doi:10.4324/9781315701974-15, ISBN 978-1-315-70197-4, retrieved 2021-06-03

- ^ Carey, Malachy (November 1981). "On Mutually Exclusive and Collectively Exhaustive Properties of Demand Functions". Economica. 48 (192): 407–415. doi:10.2307/2553697. ISSN 0013-0427. JSTOR 2553697.

- ^ Heckman (1978). "Simple Statistical Models for Discrete Panel Data Developed and Applied to Test the Hypothesis of True State Dependence against the Hypothesis of Spurious State Dependence". Annales de l'inséé (30/31): 227–269. doi:10.2307/20075292. ISSN 0019-0209. JSTOR 20075292.

- ^ Munday, Stephen C. R. (1996), "Unemployment, Inflation and the Phillips Curve", Current Developments in Economics, London: Macmillan Education UK, pp. 186–218, doi:10.1007/978-1-349-24986-2_11, ISBN 978-0-333-64444-7, retrieved 2021-06-03

- ^ Louangrath, Paul I. (2013). "Alpha and Beta Tests for Type I and Type II Inferential Errors Determination in Hypothesis Testing". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2332756. ISSN 1556-5068.

- ^ a b Yanamandra, Venkataramana (September 2015). "Exchange rate changes and inflation in India: What is the extent of exchange rate pass-through to imports?". Economic Analysis and Policy. 47: 57–68. doi:10.1016/j.eap.2015.07.004. ISSN 0313-5926.

- ^ Feinmann, Jane. "How Can Engineers and Journalists Help Each Other?" (Video). The Institute of Engineering & Technology. doi:10.1049/iet-tv.48.859. Retrieved 2021-06-03.

- ^ Dul, Jan (2015). "Necessary Condition Analysis (NCA): Logic and Methodology of 'Necessary But Not Sufficient' Causality". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2588480. hdl:1765/77890. ISSN 1556-5068. S2CID 219380122.

- ^ Robert Amar, James Eagan, and John Stasko (2005) "Low-Level Components of Analytic Activity in Information Visualization" Archived 2015-02-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ William Newman (1994) "A Preliminary Analysis of the Products of HCI Research, Using Pro Forma Abstracts" Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mary Shaw (2002) "What Makes Good Research in Software Engineering?" Archived 2018-11-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Connectivity tool transfers data among database and statistical products". Computational Statistics & Data Analysis. 8 (2): 224. July 1989. doi:10.1016/0167-9473(89)90021-2. ISSN 0167-9473.

- ^ "Information relevant to your job", Obtaining Information for Effective Management, Routledge, pp. 48–54, 2007-07-11, doi:10.4324/9780080544304-16 (inactive 1 July 2025), ISBN 978-0-08-054430-4, retrieved 2021-06-03

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ Gordon, Roger (March 1990). "Do Publicly Traded Corporations Act in the Public Interest?". National Bureau of Economic Research Working Papers. Cambridge, MA. doi:10.3386/w3303.

- ^ Rivard, Jillian R (2014). Confirmation bias in witness interviewing: Can interviewers ignore their preconceptions? (Thesis). Florida International University. doi:10.25148/etd.fi14071109.

- ^ Papineau, David (1988), "Does the Sociology of Science Discredit Science?", Relativism and Realism in Science, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 37–57, doi:10.1007/978-94-009-2877-0_2, ISBN 978-94-010-7795-8, retrieved 2021-06-03

- ^ Bromme, Rainer; Hesse, Friedrich W.; Spada, Hans, eds. (2005). Barriers and Biases in Computer-Mediated Knowledge Communication. doi:10.1007/b105100. ISBN 978-0-387-24317-7.

- ^ Heuer, Richards (2019-06-10). Heuer, Richards J (ed.). Quantitative Approaches to Political Intelligence. doi:10.4324/9780429303647. ISBN 9780429303647. S2CID 145675822.

- ^ "Introduction" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-10-25. Retrieved 2021-10-25.

- ^ "Figure 6.7. Differences in literacy scores across OECD countries generally mirror those in numeracy". doi:10.1787/888934081549. Retrieved 2021-06-03.

- ^ Ritholz, Barry. "Bad Math that Passes for Insight". Bloomberg View. Archived from the original on 2014-10-29. Retrieved 2014-10-29.

- ^ Gusnaini, Nuriska; Andesto, Rony; Ermawati (2020-12-15). "The Effect of Regional Government Size, Legislative Size, Number of Population, and Intergovernmental Revenue on The Financial Statements Disclosure". European Journal of Business and Management Research. 5 (6). doi:10.24018/ejbmr.2020.5.6.651. ISSN 2507-1076. S2CID 231675715.

- ^ Taura, Toshiharu; Nagai, Yukari (2011). "Comparing Nominal Groups to Real Teams". Design Creativity 2010. London: Springer-Verlag London. pp. 165–171. ISBN 978-0-85729-223-0.

- ^ Gross, William H. (July 1979). "Coupon Valuation and Interest Rate Cycles". Financial Analysts Journal. 35 (4): 68–71. doi:10.2469/faj.v35.n4.68. ISSN 0015-198X.

- ^ "25. General government total outlays". doi:10.1787/888932348795. Retrieved 2021-06-03.

- ^ Davenport, Thomas; Harris, Jeanne (2007). Competing on Analytics. O'Reilly. ISBN 978-1-4221-0332-6.

- ^ Aarons, D. (2009). Report finds states on course to build pupil-data systems. Education Week, 29(13), 6.

- ^ Rankin, J. (2013, March 28). How data Systems & reports can either fight or propagate the data analysis error epidemic, and how educator leaders can help. Archived 2019-03-26 at the Wayback Machine Presentation conducted from Technology Information Center for Administrative Leadership (TICAL) School Leadership Summit.

- ^ Brödermann, Eckart J. (2018), "Article 2.2.1 (Scope of the Section)", Commercial Law, Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG, p. 525, doi:10.5771/9783845276564-525, ISBN 978-3-8452-7656-4, retrieved 2021-06-03

- ^ Adèr 2008a, p. 337.

- ^ Kjell, Oscar N. E.; Thompson, Sam (19 December 2013). "Descriptive statistics indicating the mean, standard deviation and frequency of missing values for each condition (N = number of participants), and for the dependent variables (DV)". PeerJ. 1: e231. doi:10.7717/peerj.231/table-1.

- ^ Practice for Dealing With Outlying Observations, ASTM International, doi:10.1520/e0178-16a, retrieved 2021-06-03

- ^ "Alternative Coding Schemes for Dummy Variables", Regression with Dummy Variables, Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc., pp. 64–75, 1993, doi:10.4135/9781412985628.n5, ISBN 978-0-8039-5128-0, retrieved 2021-06-03

- ^ Adèr 2008a, pp. 338–341.

- ^ Newman, Isadore (1998). Qualitative-quantitative research methodology : exploring the interactive continuum. Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 0-585-17889-5. OCLC 44962443.

- ^ Terwilliger, James S.; Lele, Kaustubh (June 1979). "Some Relationships Among Internal Consistency, Reproducibility, and Homogeneity". Journal of Educational Measurement. 16 (2): 101–108. doi:10.1111/j.1745-3984.1979.tb00091.x. ISSN 0022-0655.

- ^ Adèr 2008a, pp. 341–342.

- ^ Adèr 2008a, p. 344.

- ^ Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007, p. 87-88.

- ^ Random sampling and randomization procedures, BSI British Standards, doi:10.3403/30137438, retrieved 2021-06-03

- ^ Adèr 2008a, pp. 344–345.

- ^ Foth, Christian; Hedrick, Brandon P.; Ezcurra, Martin D. (18 January 2016). "Figure 4: Centroid size regression analyses for the main sample". PeerJ. 4: e1589. doi:10.7717/peerj.1589/fig-4.

- ^ Adèr 2008a, p. 345.

- ^ Adèr 2008a, pp. 345–346.

- ^ Adèr 2008a, pp. 346–347.

- ^ Adèr 2008a, pp. 349–353.

- ^ Billings S.A. "Nonlinear System Identification: NARMAX Methods in the Time, Frequency, and Spatio-Temporal Domains". Wiley, 2013

- ^ Adèr 2008b, p. 363.

- ^ "Exploratory Data Analysis", Python® for R Users, Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp. 119–138, 2017-10-13, doi:10.1002/9781119126805.ch4, hdl:11380/971504, ISBN 978-1-119-12680-5, retrieved 2021-06-03

- ^ "Engaging in Exploratory Data Analysis, Visualization, and Hypothesis Testing – Exploratory Data Analysis, Geovisualization, and Data", Spatial Analysis, CRC Press, pp. 106–139, 2015-07-28, doi:10.1201/b18808-8, ISBN 978-0-429-06936-9, S2CID 133412598, retrieved 2021-06-03

- ^ "Hypotheses About Categories", Starting Statistics: A Short, Clear Guide, London: SAGE Publications Ltd, pp. 138–151, 2010, doi:10.4135/9781446287873.n14, ISBN 978-1-84920-098-1, retrieved 2021-06-03

- ^ Liquet, Benoit; Riou, Jérémie (2013-06-08). "Correction of the significance level when attempting multiple transformations of an explanatory variable in generalized linear models". BMC Medical Research Methodology. 13 (1): 75. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-13-75. ISSN 1471-2288. PMC 3699399. PMID 23758852.

- ^ a b c Mcardle, John J. (2008). "Some ethical issues in confirmatory versus exploratory analysis". PsycEXTRA Dataset. doi:10.1037/e503312008-001. Retrieved 2021-06-03.

- ^ Adèr 2008b, pp. 361–362.

- ^ Adèr 2008b, pp. 361–371.

- ^ Benson, Noah C; Winawer, Jonathan (December 2018). "Bayesian analysis of retinotopic maps". eLife. 7. doi:10.7554/elife.40224. PMC 6340702. PMID 30520736. Supplementary file 1. Cross-validation schema. doi:10.7554/elife.40224.014

- ^ Hsiao, Cheng (2014), "Cross-Sectionally Dependent Panel Data", Analysis of Panel Data, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 327–368, doi:10.1017/cbo9781139839327.012, ISBN 978-1-139-83932-7, retrieved 2021-06-03

- ^ Hjorth, J.S. Urban (2017-10-19), "Cross validation", Computer Intensive Statistical Methods, Chapman and Hall/CRC, pp. 24–56, doi:10.1201/9781315140056-3, ISBN 978-1-315-14005-6, retrieved 2021-06-03

- ^ Sheikholeslami, Razi; Razavi, Saman; Haghnegahdar, Amin (2019-10-10). "What should we do when a model crashes? Recommendations for global sensitivity analysis of Earth and environmental systems models". Geoscientific Model Development. 12 (10): 4275–4296. Bibcode:2019GMD....12.4275S. doi:10.5194/gmd-12-4275-2019. ISSN 1991-9603. S2CID 204900339.

- ^ United Nations Development Programme (2018). "Human development composite indices". Human Development Indices and Indicators 2018. United Nations. pp. 21–41. doi:10.18356/ce6f8e92-en. S2CID 240207510.

- ^ Wiley, Matt; Wiley, Joshua F. (2019), "Multivariate Data Visualization", Advanced R Statistical Programming and Data Models, Berkeley, CA: Apress, pp. 33–59, doi:10.1007/978-1-4842-2872-2_2, ISBN 978-1-4842-2871-5, S2CID 86629516, retrieved 2021-06-03

- ^ Mailund, Thomas (2022). Beginning Data Science in R 4: Data Analysis, Visualization, and Modelling for the Data Scientist (2nd ed.). ISBN 978-148428155-0.

- ^ "The machine learning community takes on the Higgs". Symmetry Magazine. July 15, 2014. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- ^ "Data.Gov:Long-Term Pavement Performance (LTPP)". May 26, 2016. Archived from the original on November 1, 2017. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- ^ Nehme, Jean (September 29, 2016). "LTPP International Data Analysis Contest". Federal Highway Administration. Archived from the original on October 21, 2017. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

Bibliography

[edit]- Adèr, Herman J. (2008a). "Chapter 14: Phases and initial steps in data analysis". In Adèr, Herman J.; Mellenbergh, Gideon J.; Hand, David J (eds.). Advising on research methods : a consultant's companion. Huizen, Netherlands: Johannes van Kessel Pub. pp. 333–356. ISBN 9789079418015. OCLC 905799857.

- Adèr, Herman J. (2008b). "Chapter 15: The main analysis phase". In Adèr, Herman J.; Mellenbergh, Gideon J.; Hand, David J (eds.). Advising on research methods : a consultant's companion. Huizen, Netherlands: Johannes van Kessel Pub. pp. 357–386. ISBN 9789079418015. OCLC 905799857.

- Tabachnick, B.G. & Fidell, L.S. (2007). Chapter 4: Cleaning up your act. Screening data prior to analysis. In B.G. Tabachnick & L.S. Fidell (Eds.), Using Multivariate Statistics, Fifth Edition (pp. 60–116). Boston: Pearson Education, Inc. / Allyn and Bacon.

Further reading

[edit]- Adèr, H.J. & Mellenbergh, G.J. (with contributions by D.J. Hand) (2008). Advising on Research Methods: A Consultant's Companion. Huizen, the Netherlands: Johannes van Kessel Publishing. ISBN 978-90-79418-01-5

- Chambers, John M.; Cleveland, William S.; Kleiner, Beat; Tukey, Paul A. (1983). Graphical Methods for Data Analysis, Wadsworth/Duxbury Press. ISBN 0-534-98052-X

- Fandango, Armando (2017). Python Data Analysis, 2nd Edition. Packt Publishers. ISBN 978-1787127487

- Juran, Joseph M.; Godfrey, A. Blanton (1999). Juran's Quality Handbook, 5th Edition. New York: McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-07-034003-X

- Lewis-Beck, Michael S. (1995). Data Analysis: an Introduction, Sage Publications Inc, ISBN 0-8039-5772-6

- NIST/SEMATECH (2008) Handbook of Statistical Methods

- Pyzdek, T, (2003). Quality Engineering Handbook, ISBN 0-8247-4614-7

- Richard Veryard (1984). Pragmatic Data Analysis. Oxford : Blackwell Scientific Publications. ISBN 0-632-01311-7

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. (2007). Using Multivariate Statistics, 5th Edition. Boston: Pearson Education, Inc. / Allyn and Bacon, ISBN 978-0-205-45938-4

| Part of a series on Statistics |

| Data and information visualization |

|---|

| Major dimensions |

| Important figures |

| Information graphic types |

| Related topics |

| Computational physics |

|---|

|

Data analysis

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Scope

Data analysis is the process of inspecting, cleaning, transforming, and modeling data to discover useful information, inform conclusions, and support decision-making.[5] This involves applying statistical, logical, and computational techniques to raw data, enabling the extraction of meaningful patterns and insights from complex datasets.[1] The primary objectives include data summarization to condense large volumes into key takeaways, pattern detection to identify trends or anomalies, prediction to forecast future outcomes based on historical data, and causal inference to understand relationships between variables.[6] These goals facilitate evidence-based reasoning across various contexts, from operational improvements to strategic planning.[7] Data analysis differs from related fields in its focus and scope. Unlike data science, which encompasses broader elements such as machine learning engineering, software development, and large-scale data infrastructure, data analysis emphasizes the interpretation and application of data insights without necessarily involving advanced programming or model deployment.[8] In contrast to statistics, which provides the theoretical foundations and mathematical principles for handling uncertainty and variability, data analysis applies these principles practically to real-world datasets, often integrating domain-specific knowledge for actionable results.[9] Data analysis encompasses both qualitative and quantitative types, each suited to different data characteristics and inquiry goals. Quantitative analysis deals with numerical data, employing metrics and statistical models to measure and test hypotheses, such as calculating averages or correlations in sales figures.[10] Qualitative analysis, on the other hand, examines non-numerical data like text or observations to uncover themes and meanings, often through coding and thematic interpretation in user feedback studies.[10] Within these, subtypes include descriptive analysis, which summarizes what has happened (e.g., reporting average customer satisfaction scores), and diagnostic analysis, which investigates why events occurred (e.g., drilling down into factors causing a sales dip).[6] The scope of data analysis is inherently interdisciplinary, extending beyond traditional boundaries to applications in natural and social sciences, business, and humanities. In sciences, it supports hypothesis testing and experimental validation, such as analyzing genomic sequences in biology.[2] In business, it drives market trend identification and operational optimization, like forecasting demand in supply chains.[7] In humanities, it enables the exploration of cultural artifacts, including text mining in literature or network analysis of historical events, fostering deeper interpretations of human experiences.[11] This versatility underscores data analysis as a foundational tool for knowledge generation across domains.[12]Historical Development

The origins of data analysis trace back to the 17th century, when early statistical practices emerged to interpret demographic and mortality data. In 1662, John Graunt published Natural and Political Observations Made upon the Bills of Mortality, analyzing London's weekly death records to identify patterns in causes of death, birth rates, and population trends, laying foundational work in demography and vital statistics.[13] This systematic tabulation and inference from raw data marked one of the first instances of empirical data analysis applied to public health and social phenomena. By the 19th century, Adolphe Quetelet advanced these ideas in his 1835 treatise Sur l'homme et le développement de ses facultés, ou Essai de physique sociale, introducing "social physics" to apply probabilistic methods from astronomy to human behavior, crime rates, and social averages, establishing statistics as a tool for studying societal patterns.[14] The 20th century saw the formalization of statistical inference and the integration of computational tools, transforming data analysis from manual processes to rigorous methodologies. Ronald A. Fisher pioneered analysis of variance (ANOVA) in the 1920s and 1930s through works like Statistical Methods for Research Workers (1925) and The Design of Experiments (1935), developing techniques to assess experimental variability and significance in agricultural and biological data, which became cornerstones of modern inferential statistics.[15] World War II accelerated these advancements via operations research (OR), where teams at Bletchley Park and Allied commands used code-breaking, probability models, and data-driven simulations to optimize radar deployment, convoy routing, and bombing strategies, demonstrating the strategic value of analytical methods in high-stakes decision-making.[16] Post-war, the 1945 unveiling of ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer) at the University of Pennsylvania enabled automated numerical computations for complex problems, such as artillery trajectory calculations, shifting data analysis toward programmable electronic processing.[17] Key software milestones further democratized data analysis in the late 20th century. The Statistical Analysis System (SAS), initiated in 1966 at North Carolina State University under a U.S. Department of Agriculture grant, provided tools for analyzing agricultural experiments, evolving into a comprehensive suite for multivariate statistics and data management by the 1970s.[18] In 1993, Ross Ihaka and Robert Gentleman released the first version of R at the University of Auckland, an open-source language inspired by S for statistical computing, enabling reproducible analysis and visualization through extensible packages.[19] The big data era began with Apache Hadoop's initial release in 2006, an open-source framework for distributed storage and processing of massive datasets using MapReduce, addressing scalability challenges in web-scale data from sources like search engines.[20] By the 2010s, data analysis transitioned to automated, scalable paradigms incorporating artificial intelligence (AI), with deep learning frameworks like TensorFlow (2015)[21] and exponential growth in computational power enabling real-time, predictive techniques on vast datasets.[22] This shift from manual tabulation to AI-driven methods by the 2020s has supported applications in genomics, finance, and climate modeling, where neural networks automate pattern detection and inference at unprecedented scales.Data Analysis Process

Planning and Requirements

The planning and requirements phase of data analysis serves as the foundational step in the overall process, ensuring that subsequent activities are aligned with clear objectives and feasible within constraints. This stage involves systematically defining the scope, anticipating challenges, and outlining the framework to guide data acquisition, preparation, and interpretation. Effective planning minimizes inefficiencies and enhances the reliability of insights derived from the analysis.[23] Establishing goals begins with aligning the analysis to specific research questions or business problems, such as formulating hypotheses in scientific studies or defining key performance indicators (KPIs) in organizational contexts. For instance, in quantitative research, goals are articulated as relational (e.g., examining associations between variables) or causal (e.g., testing intervention effects), which directly influences the choice of analytical methods. This alignment ensures that the analysis addresses actionable problems, like predicting customer churn through targeted KPIs such as retention rates. In analytics teams, overarching goals focus on measurable positive impact, often quantified by organizational metrics like revenue growth or operational efficiency.[23][24] Data requirements assessment entails determining the necessary variables, sample size, and data sources to support the defined goals. Variables are identified based on their measurement levels—nominal (e.g., categories like gender), ordinal (e.g., rankings), interval (e.g., temperature), or ratio (e.g., weight)—to ensure compatibility with planned analyses. Sample size is calculated a priori using power analysis tools, aiming for at least 80% statistical power to detect meaningful effect sizes while controlling for alpha levels (typically 0.05). Sources are categorized as primary (e.g., surveys designed for the study) or secondary (e.g., existing databases), with requirements prioritizing validated instruments from literature to enhance reliability.[23][25] Ethical and legal considerations are integrated early to safeguard participant rights and ensure compliance. This includes reviewing privacy regulations such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), effective since May 2018, which mandates lawful processing, data minimization, and explicit consent for personal data handling in the European Union. Plans must address potential biases, such as selection bias in variable choice, through mitigation strategies like diverse sampling. For secondary data analysis, ethical protocols require verifying original consent scopes and anonymization to prevent re-identification risks. In big data contexts, equity and autonomy are prioritized by assessing how analysis might perpetuate disparities.[26][27] Resource planning involves budgeting for tools, timelines, and expertise while conducting risk assessments for data availability. This includes allocating personnel, such as statisticians for complex designs, and software like G*Power for sample size estimation, with timelines structured around project phases to avoid delays. Risks, such as incomplete data sources, are evaluated through feasibility studies, ensuring resources align with scope—e.g., open-source tools for cost-sensitive projects. In data science initiatives, this extends to hardware for large datasets and training for team skills.[25][28] Output specification defines success metrics and delivery formats to evaluate analysis effectiveness. Metrics include accuracy thresholds (e.g., model precision above 90%) or interpretability standards, tied to goals like hypothesis confirmation. Formats may specify reports, dashboards, or visualizations, ensuring outputs are actionable—e.g., executive summaries with confidence intervals for business decisions. Success is measured against KPIs such as return on investment (ROI) or insight adoption rates, avoiding vanity metrics in favor of those linked to organizational impact.[29][30]Data Acquisition

Data acquisition is the process of collecting and sourcing raw data from various origins to fulfill the objectives outlined in the planning phase of data analysis. This stage ensures that the data gathered aligns with the required scope, providing a foundation for subsequent analytical steps. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, data acquisition encompasses four primary methods: collecting new data, converting or transforming legacy data, sharing or exchanging data, and purchasing data from external providers.[31] These methods enable analysts to obtain relevant information efficiently, whether through direct measurement or integration of existing datasets. Sources of data in data analysis are diverse and can be categorized as primary or secondary. Primary sources involve original data collection, such as surveys, experiments, and sensor readings from Internet of Things (IoT) devices, which generate real-time environmental or operational metrics.[32] Secondary sources include existing databases, public repositories like the UCI Machine Learning Repository and Kaggle datasets, which offer pre-curated collections for machine learning and statistical analysis, as well as web scraping techniques that extract information from online platforms.[33][34][35] Internal organizational sources, such as customer records from customer relationship management (CRM) systems or transactional logs from enterprise resource planning (ERP) software, also serve as key inputs.[36] Collection techniques vary based on data structure and sampling strategies to ensure representativeness and feasibility. Structured data collection employs predefined formats, such as SQL queries on relational databases, yielding organized outputs like tables of numerical or categorical values suitable for quantitative analysis.[37] In contrast, unstructured data collection involves APIs to pull diverse content from sources like social media feeds or text documents, often requiring subsequent parsing to handle variability in formats such as images or free-form text.[36] Sampling methods further refine acquisition by selecting subsets from larger populations; random sampling assigns equal probability to each unit for unbiased representation, stratified sampling divides the population into homogeneous subgroups to ensure proportional inclusion of key characteristics, and convenience sampling selects readily available units for cost-effective but less generalizable results.[38] In the context of big data, acquisition must address the challenges of high volume, velocity, and variety, particularly since the 2010s with the proliferation of IoT devices. Distributed systems like Apache Hadoop and Apache Spark facilitate handling massive datasets through parallel processing, while streaming techniques enable real-time ingestion from IoT sensors, such as continuous data flows from smart manufacturing equipment generating terabytes daily.[39][40] These approaches support scalable acquisition by partitioning data across clusters, mitigating bottlenecks in traditional centralized storage. Initial quality checks during acquisition are essential to verify data integrity before deeper processing. Validation protocols assess completeness by flagging missing entries, relevance by confirming alignment with predefined criteria, and basic accuracy through range or format checks, as outlined in the DAQCORD guidelines for observational research.[41] For instance, real-time plausibility assessments in health data acquisition ensure values fall within expected physiological bounds, reducing downstream errors.[41] Cost and scalability trade-offs influence acquisition strategies, balancing manual and automated approaches. Manual collection, such as in-person surveys, incurs high labor costs but allows nuanced control, whereas automated methods like API integrations or web scrapers offer scalability for large volumes at lower marginal expense, though initial setup may require investment in infrastructure.[42] Economic models, such as net present value assessments, quantify these decisions; for example, acquiring external data becomes viable when costs fall below $0.25 per instance for high-impact applications like fraud detection.[39] Automated systems excel in handling growing data streams from IoT, providing elasticity without proportional cost increases.[39]Data Preparation and Cleaning

Data preparation and cleaning is a critical phase in the data analysis process, where raw data from various sources is transformed and refined to ensure quality, consistency, and usability for subsequent steps. This involves identifying and addressing imperfections such as incomplete records, anomalies, discrepancies across datasets, and disparities in scale, which can otherwise lead to biased or unreliable results. Effective preparation minimizes errors propagated into exploratory analysis or modeling, enhancing the overall integrity of insights derived.[43] Handling missing values is a primary concern, as incomplete data can occur due to non-response, errors in collection, or system failures, categorized by mechanisms like missing completely at random (MCAR), missing at random (MAR), or missing not at random (MNAR). One straightforward technique is deletion, including listwise deletion (removing entire rows with any missing value) or pairwise deletion (using available data per analysis); while simple and unbiased under MCAR, deletion reduces sample size, potentially introducing bias under MAR or MNAR and leading to loss of statistical power. Imputation methods offer alternatives by estimating missing values: mean imputation replaces them with the variable's observed mean, which is computationally efficient but underestimates variability and can bias correlations by shrinking them toward zero. Median imputation is a robust variant, less affected by extreme values, suitable for skewed distributions, though it similarly reduces variance. Advanced approaches like multiple imputation, which generates several plausible datasets by drawing from posterior distributions and analyzes them to incorporate uncertainty, provide more accurate estimates, particularly for MAR data, but require greater computational resources and assumptions about the data-generating mechanism.[44][45] Outlier detection and treatment address data points that significantly deviate from the norm, potentially stemming from measurement errors, rare events, or true anomalies that could skew analyses. The Z-score method calculates a point's distance from the mean in standard deviation units, flagging values where as outliers under the assumption of approximate normality; it is sensitive and effective for symmetric distributions but performs poorly with skewness or heavy tails, and treatment options include removal (risking valid data loss) or transformation to mitigate influence. The interquartile range (IQR) method, a non-parametric approach, defines outliers as values below or above , where ; robust to non-normality and outliers in the tails, it avoids normality assumptions but may overlook subtle deviations in large datasets, with treatments like winsorizing (capping at percentile bounds) preserving sample size while reducing extreme impact. Deciding on treatment involves domain knowledge to distinguish errors from informative extremes, as indiscriminate removal can distort distributions.[46][47] Data integration merges multiple datasets to create a cohesive view, resolving inconsistencies such as differing schemas, formats, or units that arise from heterogeneous sources. Techniques include schema matching to align attributes (e.g., standardizing "date of birth" across formats like MM/DD/YYYY and YYYY-MM-DD) and entity resolution to link records referring to the same real-world object, often using probabilistic matching on keys like identifiers. Merging can be horizontal (appending rows for similar structures) or vertical (joining on common fields), but challenges like duplicate entries or conflicting values require cleaning steps such as deduplication and conflict resolution via rules or majority voting, ensuring the integrated dataset maintains referential integrity without introducing artifacts. This process is foundational for analyses spanning sources, though it demands careful validation to avoid propagation of errors.[48] Normalization and scaling adjust feature ranges to promote comparability, preventing variables with larger scales from dominating distance-based or gradient-descent algorithms. Min-max scaling, also known as rescaling, transforms data to a bounded interval, typically [0, 1], using the formula: where is the feature vector; this preserves exact relationships and relative distances but is sensitive to outliers, which can compress the majority of data. It is particularly useful for algorithms assuming bounded inputs, like neural networks, though reapplication is needed if new data extends the range. Documentation during preparation is essential for traceability, involving detailed logging of transformations—such as imputation choices, outlier thresholds, integration mappings, and scaling parameters—in metadata files or version-controlled scripts. This practice enables reproducibility, facilitates auditing for compliance, and supports debugging by reconstructing the data lineage, reducing risks from untracked changes in collaborative environments.[49][43]Exploratory Analysis

Exploratory data analysis (EDA) involves initial examinations of datasets to reveal underlying structures, detect patterns, and identify potential issues before more formal modeling occurs. Coined by statistician John W. Tukey in his 1977 book, EDA emphasizes graphical and numerical techniques to summarize data characteristics and foster intuitive understanding, contrasting with confirmatory analysis that tests predefined hypotheses.[50] This phase is crucial for uncovering unexpected insights and guiding subsequent analytical steps. Univariate analysis focuses on individual variables to describe their distributions and central tendencies, providing a foundational view of the data. Common summary measures include the mean, which calculates the arithmetic average as the sum of values divided by the count; the median, the middle value in an ordered dataset; and the mode, the most frequent value.[51] These measures help assess skewness and outliers—for instance, the mean is sensitive to extreme values, while the median offers robustness in skewed distributions. Visual tools like histograms display frequency distributions, revealing shapes such as unimodal or bimodal patterns that indicate the data's variability and spread.[51][52] Bivariate and multivariate analyses extend this to relationships between two or more variables, aiding in the detection of associations and dependencies. Scatter plots visualize pairwise relationships, highlighting trends like positive or negative slopes, while correlation matrices summarize multiple pairwise correlations in a tabular format. The Pearson correlation coefficient, defined as , quantifies the strength and direction of linear relationships between continuous variables, ranging from -1 (perfect negative) to +1 (perfect positive).[53][54] For multivariate exploration, these techniques reveal interactions, such as how a third variable might influence bivariate patterns, without implying causation.[54] In high-dimensional datasets, previews of dimensionality reduction techniques like principal component analysis (PCA) offer insights into data structure by transforming variables into uncorrelated principal components that capture maximum variance. PCA computes components as linear combinations of original features, ordered by explained variance, enabling visualization of clusters or separations in reduced dimensions—typically the first two or three for plotting. This approach helps identify dominant patterns while previewing noise or redundancy, though full implementation follows initial EDA. EDA facilitates hypothesis generation by spotting anomalies, such as outliers deviating from expected distributions, or trends like seasonal variations in time-series data, which prompt questions for deeper investigation. Unlike formal hypothesis testing, this process relies on visual and summary inspections to inspire ideas, ensuring analyses remain data-driven rather than assumption-led.[50] Tools for EDA often include interactive environments like Jupyter notebooks, which integrate code, visualizations, and narratives for iterative exploration. Libraries such as Pandas for data summaries (e.g.,describe() for means and quartiles) and Matplotlib or Seaborn for plots (e.g., histograms via plt.hist()) enable rapid prototyping of univariate and bivariate views.[55] These setups support reproducible workflows, allowing analysts to document discoveries alongside code outputs.[55]