Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Data and information visualization

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on Statistics |

| Data and information visualization |

|---|

| Major dimensions |

| Important figures |

| Information graphic types |

| Related topics |

| Information mapping |

|---|

| Topics and fields |

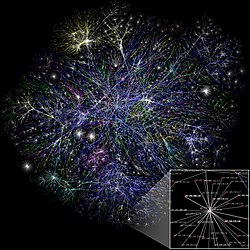

| Node–link approaches |

|

| See also |

Data and information visualization (data viz/vis or info viz/vis) is the practice of designing and creating graphic or visual representations of[2] quantitative and qualitative data and information with the help of static, dynamic or interactive visual items. These visualizations are intended to help a target audience visually explore and discover, quickly understand, interpret and gain important insights into otherwise difficult-to-identify structures, relationships, correlations, local and global patterns, trends, variations, constancy, clusters, outliers and unusual groupings within data.[3][4][5] When intended for the public to convey a concise version of information in an engaging manner,[3] it is typically called infographics.

Data visualization is concerned with presenting sets of primarily quantitative raw data in a schematic form, using imagery. The visual formats used in data visualization include charts and graphs, geospatial maps, figures, correlation matrices, percentage gauges, etc..

Information visualization deals with multiple, large-scale and complicated datasets which contain quantitative data, as well as qualitative, and primarily abstract information, and its goal is to add value to raw data, improve the viewers' comprehension, reinforce their cognition and help derive insights and make decisions as they navigate and interact with the graphical display. Visual tools used include maps for location based data; hierarchical[6] organisations of data; displays that prioritise relationships such as Sankey diagrams; flowcharts, timelines.

Emerging technologies like virtual, augmented and mixed reality have the potential to make information visualization more immersive, intuitive, interactive and easily manipulable and thus enhance the user's visual perception and cognition.[7] In data and information visualization, the goal is to graphically present and explore abstract, non-physical and non-spatial data collected from databases, information systems, file systems, documents, business data, which is different from scientific visualization, where the goal is to render realistic images based on physical and spatial scientific data to confirm or reject hypotheses.[8]

Effective data visualization is well-sourced, appropriately contextualized, and presented in a simple, uncluttered manner. The underlying data is accurate and up-to-date to ensure insights are reliable. Graphical items are well-chosen and aesthetically appealing, with shapes, colors and other visual elements used deliberately in a meaningful and non-distracting manner. The visuals are accompanied by supporting texts. Verbal and graphical components complement each other to ensure clear, quick and memorable understanding. Effective information visualization is aware of the needs and expertise level of the target audience.[9][2] Effective visualization can be used for conveying specialized, complex, big data-driven ideas to a non-technical audience in a visually appealing, engaging and accessible manner, and domain experts and executives for making decisions, monitoring performance, generating ideas and stimulating research.[9][3]

Data scientists, analysts and data mining specialists use data visualization to check data quality, find errors, unusual gaps, missing values, clean data, explore the structures and features of data, and assess outputs of data-driven models.[3] Data and information visualization can be part of data storytelling, where they are paired with a narrative structure, to contextualize the analyzed data and communicate insights gained from analyzing it to convince the audience into making a decision or taking action.[2][10] This can be contrasted with statistical graphics, where complex data are communicated graphically among researchers and analysts to help them perform exploratory data analysis or convey results of such analyses, where visual appeal, capturing attention to a certain issue and storytelling are less important.[11]

Data and information visualization is interdisciplinary, it incorporates principles found in descriptive statistics,[12] visual communication, graphic design, cognitive science and, interactive computer graphics and human-computer interaction.[13] Since effective visualization requires design skills, statistical skills and computing skills, it is both an art and a science.[14] Visual analytics combines statistical data analysis, data and information visualization, and human analytical reasoning through interactive visual interfaces to help users reach conclusions, gain actionable insights and make informed decisions which are otherwise difficult for computers to do. Research into how people read and misread types of visualizations helps to determine what types and features of visualizations are most understandable and effective.[15][16] Unintentionally poor or intentionally misleading and deceptive visualizations can function as powerful tools which disseminate misinformation, manipulate public perception and divert public opinion.[17] Thus data visualization literacy has become an important component of data and information literacy in the information age akin to the roles played by textual, mathematical and visual literacy in the past.[18]

Overview

[edit]

The field of data and information visualization has emerged "from research in human–computer interaction, computer science, graphics, visual design, psychology, photography and business methods. It is increasingly applied as a critical component in scientific research, digital libraries, data mining, financial data analysis, market studies, manufacturing production control, and drug discovery".[19]

Data and information visualization presumes that "visual representations and interaction techniques take advantage of the human eye's broad bandwidth pathway into the mind to allow users to see, explore, and understand large amounts of information at once. Information visualization focused on the creation of approaches for conveying abstract information in intuitive ways."[20]

Data analysis is an indispensable part of all applied research and problem solving in industry. The most fundamental data analysis approaches are visualization (histograms, scatter plots, surface plots, tree maps, parallel coordinate plots, etc.), statistics (hypothesis test, regression, PCA, etc.), data mining (association mining, etc.), and machine learning methods (clustering, classification, decision trees, etc.). Among these approaches, information visualization, or visual data analysis, is the most reliant on the cognitive skills of human analysts, and allows the discovery of unstructured actionable insights that are limited only by human imagination and creativity. The analyst does not have to learn any sophisticated methods to be able to interpret the visualizations of the data. Information visualization is also a hypothesis generation scheme, which can be, and is typically followed by more analytical or formal analysis, such as statistical hypothesis testing.

To communicate information clearly and efficiently, data visualization uses statistical graphics, plots, information graphics and other tools. Numerical data may be encoded using dots, lines, or bars, to visually communicate a quantitative message.[21] Effective visualization helps users analyze and reason about data and evidence.[22] It makes complex data more accessible, understandable, and usable, but can also be reductive.[23] Users may have particular analytical tasks, such as making comparisons or understanding causality, and the design principle of the graphic (i.e., showing comparisons or showing causality) follows the task. Tables are generally used where users will look up a specific measurement, while charts of various types are used to show patterns or relationships in the data for one or more variables.

Data visualization refers to the techniques used to communicate data or information by encoding it as visual objects (e.g., points, lines, or bars) contained in graphics. The goal is to communicate information clearly and efficiently to users. It is one of the steps in data analysis or data science. According to Vitaly Friedman (2008) the "main goal of data visualization is to communicate information clearly and effectively through graphical means. It doesn't mean that data visualization needs to look boring to be functional or extremely sophisticated to look beautiful. To convey ideas effectively, both aesthetic form and functionality need to go hand in hand, providing insights into a rather sparse and complex data set by communicating its key aspects in a more intuitive way. Yet designers often fail to achieve a balance between form and function, creating gorgeous data visualizations which fail to serve their main purpose — to communicate information".[24]

Indeed, Fernanda Viegas and Martin M. Wattenberg suggested that an ideal visualization should not only communicate clearly, but stimulate viewer engagement and attention.[25]

Data visualization is closely related to information graphics, information visualization, scientific visualization, exploratory data analysis and statistical graphics. In the new millennium, data visualization has become an active area of research, teaching and development. According to Post et al. (2002), it has united scientific and information visualization.[26]

In the commercial environment data visualization is often referred to as dashboards. Infographics are another very common form of data visualization.

Principles

[edit]Characteristics of effective graphical displays

[edit]The greatest value of a picture is when it forces us to notice what we never expected to see.

Edward Tufte has explained that users of information displays are executing particular analytical tasks such as making comparisons. The design principle of the information graphic should support the analytical task.[28] As William Cleveland and Robert McGill show, different graphical elements accomplish this more or less effectively. For example, dot plots and bar charts outperform pie charts.[29]

In his 1983 book The Visual Display of Quantitative Information,[30] Edward Tufte defines 'graphical displays' and principles for effective graphical display in the following passage: "Excellence in statistical graphics consists of complex ideas communicated with clarity, precision, and efficiency. Graphical displays should:

- show the data

- induce the viewer to think about the substance rather than about methodology, graphic design, the technology of graphic production, or something else

- avoid distorting what the data has to say

- present many numbers in a small space

- make large data sets coherent

- encourage the eye to compare different pieces of data

- reveal the data at several levels of detail, from a broad overview to the fine structure

- serve a reasonably clear purpose: description, exploration, tabulation, or decoration

- be closely integrated with the statistical and verbal descriptions of a data set.

Graphics reveal data. Indeed, graphics can be more precise and revealing than conventional statistical computations."[31]

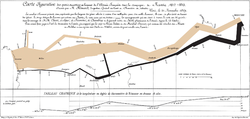

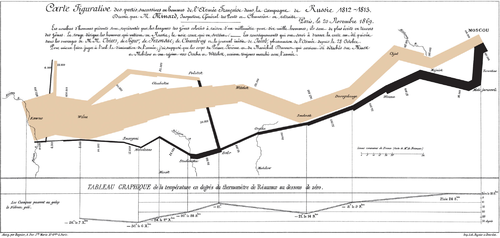

For example, the Minard diagram shows the losses suffered by Napoleon's army in the 1812–1813 period. Six variables are plotted: the size of the army, its location on a two-dimensional surface (x and y), time, the direction of movement, and temperature. The line width illustrates a comparison (size of the army at points in time), while the temperature axis suggests a cause of the change in army size. This multivariate display on a two-dimensional surface tells a story that can be grasped immediately while identifying the source data to build credibility. Tufte wrote in 1983 that: "It may well be the best statistical graphic ever drawn."[31]

Not applying these principles may result in misleading graphs, distorting the message, or supporting an erroneous conclusion. According to Tufte, chartjunk refers to the extraneous interior decoration of the graphic that does not enhance the message or gratuitous three-dimensional or perspective effects. Needlessly separating the explanatory key from the image itself, requiring the eye to travel back and forth from the image to the key, is a form of "administrative debris." The ratio of "data to ink" should be maximized, erasing non-data ink where feasible.[31]

The Congressional Budget Office summarized several best practices for graphical displays in a June 2014 presentation. These included: a) Knowing your audience; b) Designing graphics that can stand alone outside the report's context; and c) Designing graphics that communicate the key messages in the report.[32]

Useful criteria for a data or information visualization include:[33]

- It is based on (non-visual) data - that is, a data/info viz is not image processing and collage;

- It creates an image - specifically that the image plays the primary role in communicating meaning and is not an illustration accompanying the data in text form; and

- The result is readable.

Readability means that it is possible for a viewer to understand the underlying data, such as by making comparisons between proportionally sized visual elements to compare their respective data values; or using a legend to decode a map, like identifying coloured regions on a climate map to read temperature at that location. For greatest efficiency and simplicity of design and user experience, this readability is enhanced through the use of bijective mapping in that design of the image elements - where the mapping of representational element to data variable is unique.[34]

Kosara (2007)[33] also identifies the need for a visualisation to be "recognisable as a visualisation and not appear to be something else". He also states that recognisability and readability may not always be required in all types of visualisation e.g. "informative art" (which would still meet all three above criteria but might not look like a visualisation) or "artistic visualisation" (which similarly is still based on non-visual data to create an image, but may not be readable or recognisable).

Quantitative messages

[edit]

Author Stephen Few described eight types of quantitative messages that users may attempt to understand or communicate from a set of data and the associated graphs used to help communicate the message:

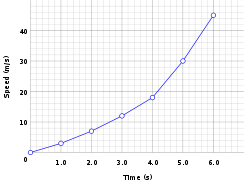

- Time-series: A single variable is captured over a period of time, such as the unemployment rate or temperature measures over a 10-year period. A line chart may be used to demonstrate the trend over time.

- Ranking: Categorical subdivisions are ranked in ascending or descending order, such as a ranking of sales performance (the measure) by sales persons (the category, with each sales person a categorical subdivision) during a single period. A bar chart may be used to show the comparison across the sales persons.

- Part-to-whole: Categorical subdivisions are measured as a ratio to the whole (i.e., a percentage out of 100%). A pie chart or bar chart can show the comparison of ratios, such as the market share represented by competitors in a market.

- Deviation: Categorical subdivisions are compared against a reference, such as a comparison of actual vs. budget expenses for several departments of a business for a given time period. A bar chart can show comparison of the actual versus the reference amount.

- Frequency distribution: Shows the number of observations of a particular variable for given interval, such as the number of years in which the stock market return is between intervals such as 0–10%, 11–20%, etc. A histogram, a type of bar chart, may be used for this analysis. A boxplot helps visualize key statistics about the distribution, such as median, quartiles, outliers, etc.

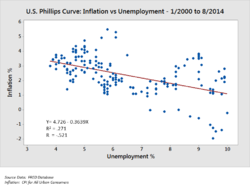

- Correlation: Comparison between observations represented by two variables (X,Y) to determine if they tend to move in the same or opposite directions. For example, plotting unemployment (X) and inflation (Y) for a sample of months. A scatter plot is typically used for this message.

- Nominal comparison: Comparing categorical subdivisions in no particular order, such as the sales volume by product code. A bar chart may be used for this comparison.

- Geographic or geospatial: Comparison of a variable across a map or layout, such as the unemployment rate by state or the number of persons on the various floors of a building. A cartogram is a typical graphic used.[21][36]

Analysts reviewing a set of data may consider whether some or all of the messages and graphic types above are applicable to their task and audience. The process of trial and error to identify meaningful relationships and messages in the data is part of exploratory data analysis.

Visual perception and data visualization

[edit]

A human can distinguish differences in line length, shape, orientation, distances, and color (hue) readily without significant processing effort; these are referred to as "pre-attentive attributes". For example, it may require significant time and effort ("attentive processing") to identify the number of times the digit "5" appears in a series of numbers; but if that digit is different in size, orientation, or color, instances of the digit can be noted quickly through pre-attentive processing.[37]

Compelling graphics take advantage of pre-attentive processing and attributes and the relative strength of these attributes. For example, since humans can more easily process differences in line length than surface area, it may be more effective to use a bar chart (which takes advantage of line length to show comparison) rather than pie charts (which use surface area to show comparison).[37]

Human perception/cognition and data visualization

[edit]Almost all data visualizations are created for human consumption. Knowledge of human perception and cognition is necessary when designing intuitive visualizations.[38] Cognition refers to processes in human beings like perception, attention, learning, memory, thought, concept formation, reading, and problem solving.[39] Human visual processing is efficient in detecting changes and making comparisons between quantities, sizes, shapes and variations in lightness. When properties of symbolic data are mapped to visual properties, humans can browse through large amounts of data efficiently. It is estimated that 2/3 of the brain's neurons can be involved in visual processing. Proper visualization provides a different approach to show potential connections, relationships, etc. which are not as obvious in non-visualized quantitative data. Visualization can become a means of data exploration.

Studies have shown individuals used on average 19% less cognitive resources, and 4.5% better able to recall details when comparing data visualization with text.[40]

History

[edit]There is no comprehensive history of data visualization. There are no accounts that span the entire development of visual thinking and visual representation of data, and which collate the contributions of disparate disciplines.[41] Michael Friendly and Daniel Denis of York University are engaged in a project that attempts to provide a comprehensive history of visualization. Data visualization is not a modern development. Since prehistory, stellar data, or information such as location of stars were visualized on the walls of caves (such as those found in Lascaux Cave in Southern France) since the Pleistocene era.[42] Physical artefacts such as Mesopotamian clay tokens (5500 BC), Inca quipus (2600 BC) and Marshall Islands stick charts (n.d.) can also be considered as visualizing quantitative information.[43][44]

The first documented data visualization can be tracked back to 1160 B.C. with the Turin Papyrus Map which accurately illustrates the distribution of geological resources and provides information about quarrying of those resources.[45] Such maps can be categorized as thematic cartography, which is a type of data visualization that presents and communicates specific data and information through a geographical illustration designed to show a particular theme connected with a specific geographic area. Earliest documented forms of data visualization were various thematic maps from different cultures and ideograms and hieroglyphs that provided and allowed interpretation of information illustrated. For example, Linear B tablets of Mycenae provided a visualization of information regarding Late Bronze Age era trades in the Mediterranean. The idea of coordinates was used by ancient Egyptian surveyors in laying out towns, earthly and heavenly positions were located by something akin to latitude and longitude at least by 200 BC, and the map projection of a spherical Earth into latitude and longitude by Claudius Ptolemy [c. 85–c. 165] in Alexandria would serve as reference standards until the 14th century.[45]

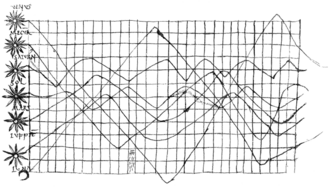

The invention of paper and parchment allowed further development of visualizations. One graph from the 10th or possibly 11th century is an illustration of planetary movements, used in an appendix of a textbook in monastery schools.[46] The graph apparently was meant to represent a plot of the inclinations of the planetary orbits as a function of the time. For this purpose, the zone of the zodiac was represented on a plane with a horizontal line divided into thirty parts as the time or longitudinal axis. The vertical axis designates the width of the zodiac. The horizontal scale appears to have been chosen for each planet individually for the periods cannot be reconciled. The accompanying text refers only to the amplitudes. The curves are apparently not related in time.

By the 16th century, techniques and instruments for precise observation and measurement of physical quantities, and geographic and celestial position were well-developed (for example, a "wall quadrant" constructed by Tycho Brahe [1546–1601], covering an entire wall in his observatory). Particularly important were the development of triangulation and other methods to determine mapping locations accurately.[41] Very early, the measure of time led scholars to develop innovative way of visualizing the data (e.g. Lorenz Codomann in 1596, Johannes Temporarius in 1596[47]).

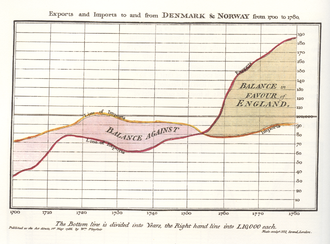

Mathematicians René Descartes and Pierre de Fermat developed analytic geometry and two-dimensional coordinate system which heavily influenced the practical methods of displaying and calculating values. Fermat and Blaise Pascal's work on statistics and probability theory laid the groundwork for what we now conceptualize as data.[41] These developments helped William Playfair, who saw potential for graphical communication of quantitative data, to generate and develop graphical methods of statistics.[38] In 1786, Playfair published the first presentation graphics.

In the second half of the 20th century, Jacques Bertin used quantitative graphs to represent information "intuitively, clearly, accurately, and efficiently".[38] John Tukey and Edward Tufte pushed the bounds of data visualization; Tukey with his new statistical approach of exploratory data analysis and Tufte with his book "The Visual Display of Quantitative Information" paved the way for refining data visualization techniques for more than statisticians. With the progression of technology came the progression of data visualization; starting with hand-drawn visualizations and evolving into more technical applications – including interactive designs leading to software visualization.[48]

The modern study of visualization started with computer graphics, which "has from its beginning been used to study scientific problems. However, in its early days the lack of graphics power often limited its usefulness. The recent emphasis on visualization started in 1987 with the special issue of Computer Graphics on Visualization in Scientific Computing. Since then there have been several conferences and workshops, co-sponsored by the IEEE Computer Society and ACM SIGGRAPH".[49] They have been devoted to the general topics of data visualization, information visualization and scientific visualization, and more specific areas such as volume visualization.

Programs like SAS, SOFA, R, Minitab, Cornerstone and more allow for data visualization in the field of statistics. Other data visualization applications, more focused and unique to individuals, programming languages such as D3, Python (through matplotlib, seaborn) and JavaScript and Java(through JavaFX) help to make the visualization of quantitative data a possibility. Private schools have also developed programs to meet the demand for learning data visualization and associated programming libraries, including free programs like The Data Incubator or paid programs like General Assembly.[50]

Beginning with the symposium "Data to Discovery" in 2013, ArtCenter College of Design, Caltech and JPL in Pasadena have run an annual program on interactive data visualization.[51] The program asks: How can interactive data visualization help scientists and engineers explore their data more effectively? How can computing, design, and design thinking help maximize research results? What methodologies are most effective for leveraging knowledge from these fields? By encoding relational information with appropriate visual and interactive characteristics to help interrogate, and ultimately gain new insight into data, the program develops new interdisciplinary approaches to complex science problems, combining design thinking and the latest methods from computing, user-centered design, interaction design and 3D graphics.

Terminology

[edit]Data visualization involves specific terminology, some of which is derived from statistics. For example, author Stephen Few defines two types of data, which are used in combination to support a meaningful analysis or visualization:

- Categorical: Represent groups of objects with a particular characteristic. Categorical variables can either be nominal or ordinal. Nominal variables for example gender have no order between them and are thus nominal. Ordinal variables are categories with an order, for sample recording the age group someone falls into.[52]

- Quantitative: Represent measurements, such as the height of a person or the temperature of an environment. Quantitative variables can either be continuous or discrete. Continuous variables capture the idea that measurements can always be made more precisely. While discrete variables have only a finite number of possibilities, such as a count of some outcomes or an age measured in whole years.[52]

The distinction between quantitative and categorical variables is important because the two types require different methods of visualization.

Two primary types of information displays are tables and graphs.

- A table contains quantitative data organized into rows and columns with categorical labels. It is primarily used to look up specific values. In the example above, the table might have categorical column labels representing the name (a qualitative variable) and age (a quantitative variable), with each row of data representing one person (the sampled experimental unit or category subdivision).

- A graph is primarily used to show relationships among data and portrays values encoded as visual objects (e.g., lines, bars, or points). Numerical values are displayed within an area delineated by one or more axes. These axes provide scales (quantitative and categorical) used to label and assign values to the visual objects. Many graphs are also referred to as charts.[53]

Eppler and Lengler have developed the "Periodic Table of Visualization Methods," an interactive chart displaying various data visualization methods. It includes six types of data visualization methods: data, information, concept, strategy, metaphor and compound.[54] In "Visualization Analysis and Design" Tamara Munzner writes "Computer-based visualization systems provide visual representations of datasets designed to help people carry out tasks more effectively." Munzner argues that visualization "is suitable when there is a need to augment human capabilities rather than replace people with computational decision-making methods."[55]

Techniques

[edit]| Name | Visual dimensions | Description / Example usages | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Bar chart |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Orthogonal (orthogonal composite) bar chart |

|

|

| Histogram |

|

| |

| Scatter plot (dot plot) |

|

| |

| Scatter plot (3D) |

|

| |

|

Network |

|

|

|

Pie chart |

|

|

|

Line chart |

|

|

|

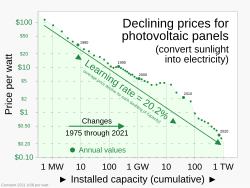

Semi-log or log-log (non-linear) charts |

|

|

|

Streamgraph (type of area chart) |

|

|

|

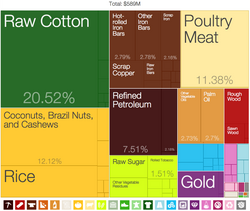

Treemap |

|

|

|

Gantt chart |

|

|

|

Heat map |

|

|

|

Stripe graphic |

|

|

|

Animated spiral graphic |

|

|

|

Box and Whisker Plot |

|

|

|

Flowchart | ||

|

Radar chart |

|

|

|

Venn diagram |

| |

| Iconography of correlations |

|

|

Other techniques

[edit]- Cartogram – Map distorting size to show another value

- Cladogram – Method of biological systematics in evolutionary biology (phylogeny)

- Concept map – Diagram showing relationships among conceptsping

- Dendrogram – Diagram with a treelike structure (classification)

- Information visualization reference model

- Grand tour – Data visualisation technique

- Graph drawing – Visualization of node-link graphs

- Hyperbolic tree – Mathematical tree in the hyperbolic plane

- Multidimensional scaling – Set of related ordination techniques used in information visualization

- Parallel coordinates – Chart displaying multivariate data

- Problem solving environment – Type of computer software

Interactivity

[edit]Interactive data visualization enables direct actions on a graphical plot to change elements and link between multiple plots.[58]

Interactive data visualization has been a pursuit of statisticians since the late 1960s. Examples of the developments can be found on the American Statistical Association video lending library.[59]

Common interactions include:

- Brushing: works by using the mouse to control a paintbrush, directly changing the color or glyph of elements of a plot. The paintbrush is sometimes a pointer and sometimes works by drawing an outline of sorts around points; the outline is sometimes irregularly shaped, like a lasso. Brushing is most commonly used when multiple plots are visible and some linking mechanism exists between the plots. There are several different conceptual models for brushing and a number of common linking mechanisms. Brushing scatterplots can be a transient operation in which points in the active plot only retain their new characteristics. At the same time, they are enclosed or intersected by the brush, or it can be a persistent operation, so that points retain their new appearance after the brush has been moved away. Transient brushing is usually chosen for linked brushing, as we have just described.

- Painting: Persistent brushing is useful when we want to group the points into clusters and then proceed to use other operations, such as the tour, to compare the groups. It is becoming common terminology to call the persistent operation painting,

- Identification: which could also be called labeling or label brushing, is another plot manipulation that can be linked. Bringing the cursor near a point or edge in a scatterplot, or a bar in a barchart, causes a label to appear that identifies the plot element. It is widely available in many interactive graphics, and is sometimes called mouseover.

- Scaling: maps the data onto the window, and changes in the area of the. mapping function help us learn different things from the same plot. Scaling is commonly used to zoom in on crowded regions of a scatterplot, and it can also be used to change the aspect ratio of a plot, to reveal different features of the data.

- Linking: connects elements selected in one plot with elements in another plot. The simplest kind of linking, one-to-one, where both plots show different projections of the same data, and a point in one plot corresponds to exactly one point in the other. When using area plots, brushing any part of an area has the same effect as brushing it all and is equivalent to selecting all cases in the corresponding category. Even when some plot elements represent more than one case, the underlying linking rule still links one case in one plot to the same case in other plots. Linking can also be by categorical variable, such as by a subject id, so that all data values corresponding to that subject are highlighted, in all the visible plots.

Other perspectives

[edit]There are different approaches on the scope of data visualization. One common focus is on information presentation, such as Friedman (2008). Friendly (2008) presumes two main parts of data visualization: statistical graphics, and thematic cartography.[60] In this line the "Data Visualization: Modern Approaches" (2007) article gives an overview of seven subjects of data visualization:[61]

- Articles & resources

- Displaying connections

- Displaying data

- Displaying news

- Displaying websites

- Mind maps

- Tools and services

All these subjects are closely related to graphic design and information representation.

From a computer science perspective, Frits Post in 2002 categorized the field into sub-fields:[26][62]

- Information visualization

- Interaction techniques and architectures

- Modelling techniques

- Multiresolution methods

- Visualization algorithms and techniques

- Volume visualization

Within The Harvard Business Review, Scott Berinato developed a framework to approach data visualisation.[63] To start thinking visually, users must consider two questions; 1) What you have and 2) what you're doing. The first step is identifying what data you want visualised. It is data-driven like profit over the past ten years or a conceptual idea like how a specific organisation is structured. Once this question is answered one can then focus on whether they are trying to communicate information (declarative visualisation) or trying to figure something out (exploratory visualisation). Scott Berinato combines these questions to give four types of visual communication that each have their own goals.[63]

These four types of visual communication are as follows;

- idea illustration (conceptual & declarative).[63]

- Used to teach, explain and/or simply concepts. For example, organisation charts and decision trees.

- idea generation (conceptual & exploratory).[63]

- Used to discover, innovate and solve problems. For example, a whiteboard after a brainstorming session.

- visual discovery (data-driven & exploratory).[63]

- Used to spot trends and make sense of data. This type of visual is more common with large and complex data where the dataset is somewhat unknown and the task is open-ended.

- everyday data-visualisation (data-driven & declarative).[63]

- The most common and simple type of visualisation used for affirming and setting context. For example, a line graph of GDP over time.

Applications

[edit]Data and information visualization insights are being applied in areas such as:[19]

- Scientific research

- Digital libraries

- Data mining

- Information graphics

- Financial data analysis

- Health care[64]

- Market studies

- Manufacturing production control

- Crime mapping

- eGovernance and Policy Modeling

- Digital Humanities

- Data Art

Organization

[edit]Notable academic and industry laboratories in the field are:

- Adobe Research

- IBM Research

- Google Research

- Microsoft Research

- Panopticon Software

- Scientific Computing and Imaging Institute

- Tableau Software

- University of Maryland Human-Computer Interaction Lab

Conferences in this field, ranked by significance in data visualization research,[65] are:

- IEEE Visualization: An annual international conference on scientific visualization, information visualization, and visual analytics. Conference is held in October.

- ACM SIGGRAPH: An annual international conference on computer graphics, convened by the ACM SIGGRAPH organization. Conference dates vary.

- Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI): An annual international conference on human–computer interaction, hosted by ACM SIGCHI. Conference is usually held in April or May.

- Eurographics: An annual Europe-wide computer graphics conference, held by the European Association for Computer Graphics. Conference is usually held in April or May.

For further examples, see: Category:Computer graphics organizations

Data presentation architecture

[edit]

Data presentation architecture (DPA) is a skill-set that seeks to identify, locate, manipulate, format and present data in such a way as to optimally communicate meaning and knowledge. Historically, data presentation architecture is attributed to Kelly Lautt:[a] "Data Presentation Architecture (DPA) is a rarely applied skill set critical for the success and value of Business Intelligence. Data presentation architecture weds the science of numbers, data and statistics in discovering valuable information from data and making it usable, relevant and actionable with the arts of data visualization, communications, organizational psychology and change management in order to provide business intelligence solutions with the data scope, delivery timing, format and visualizations that will most effectively support and drive operational, tactical and strategic behaviour toward understood business (or organizational) goals. DPA is neither an IT nor a business skill set but exists as a separate field of expertise. Often confused with data visualization, data presentation architecture is a much broader skill set that includes determining what data on what schedule and in what exact format is to be presented, not just the best way to present data that has already been chosen. Data visualization skills are one element of DPA."

Objectives

[edit]DPA has two main objectives:

- To use data to provide knowledge in the most efficient manner possible (minimize noise, complexity, and unnecessary data or detail given each audience's needs and roles)

- To use data to provide knowledge in the most effective manner possible (provide relevant, timely and complete data to each audience member in a clear and understandable manner that conveys important meaning, is actionable and can affect understanding, behavior and decisions)

Scope

[edit]With the above objectives in mind, the actual work of data presentation architecture consists of:

- Creating effective delivery mechanisms for each audience member depending on their role, tasks, locations and access to technology

- Defining important meaning (relevant knowledge) that is needed by each audience member in each context

- Determining the required periodicity of data updates (the currency of the data)

- Determining the right timing for data presentation (when and how often the user needs to see the data)

- Finding the right data (subject area, historical reach, breadth, level of detail, etc.)

- Utilizing appropriate analysis, grouping, visualization, and other presentation formats

Related fields

[edit]DPA work shares commonalities with several other fields, including:

- Business analysis in determining business goals, collecting requirements, mapping processes.

- Business process improvement in that its goal is to improve and streamline actions and decisions in furtherance of business goals

- Data visualization in that it uses well-established theories of visualization to add or highlight meaning or importance in data presentation.

- Digital humanities explores more nuanced ways of visualising complex data.

- Information architecture, but information architecture's focus is on unstructured data and therefore excludes both analysis (in the statistical/data sense) and direct transformation of the actual content (data, for DPA) into new entities and combinations.

- HCI and interaction design, since many of the principles in how to design interactive data visualisation have been developed cross-disciplinary with HCI.

- Visual journalism and data-driven journalism or data journalism: Visual journalism is concerned with all types of graphic facilitation of the telling of news stories, and data-driven and data journalism are not necessarily told with data visualisation. Nevertheless, the field of journalism is at the forefront in developing new data visualisations to communicate data.

- Graphic design, conveying information through styling, typography, position, and other aesthetic concerns.

See also

[edit]- Analytics

- Climate change art

- Computational visualistics

- Data management

- Data physicalization

- Data profiling

- Data warehouse

- imc FAMOS, graphical data analysis

- Information management

- List of information graphics software

- List of countries by economic complexity, example of Treemapping

- List of mathematical art software

- Patent visualisation

- Pirouette: Turning Points in Design

- Statistical inference

Notes

[edit]- ^ The first formal, recorded, public usages of the term data presentation architecture were at Microsoft Office 2007 launch events in Dec, Jan and Feb of 2007–08 in Edmonton, Calgary and Vancouver, in a presentation by Kelly Lautt describing a business intelligence system designed to improve service quality in a pulp and paper company. The term was recorded in public usage on December 16, 2009 in a Microsoft Canada presentation on the value of merging Business Intelligence with corporate collaboration processes.

References

[edit]- ^ Corbett, John. "Charles Joseph Minard: Mapping Napoleon's March, 1861". Center for Spatially Integrated Social Science. Archived from the original on 19 June 2003. (CSISS website has moved; use archive link for article)

- ^ a b c Nussbaumer Knaflic, Cole (2 November 2015). Storytelling with Data: A Data Visualization Guide for Business Professionals. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-119-00225-3.

- ^ a b c d Antony Unwin (31 January 2020). "Why Is Data Visualization Important? What Is Important in Data Visualization?". Harvard Data Science Review. 2 (1). doi:10.1162/99608f92.8ae4d525. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- ^ Ananda Mitra (2018), "Managing and Visualizing Unstructured Big Data", Encyclopedia of Information Science and Technology (4th ed.), IGI Global

- ^ Bhuvanendra Putchala; Lasya Sreevidya Kanala; Devi Prasanna Donepudi; Hari Kishan Kondaveeti (2023), "Applications of Big Data Analytics in Healthcare Informatics", in Narasimha Rao Vajjhala; Philip Eappen (eds.), Health Informatics and Patient Safety in Times of Crisis, IGI Global, pp. 175–194

- ^ Heer, Jeffrey, Bostock, Michael, Ogievetsky, Vadim (2010) A tour through the visualization zoo, Communications of the ACM, Volume 53, Issue 6 Pages 59 - 67 https://doi.org/10.1145/1743546.1743567

- ^ Olshannikova, Ekaterina; Ometov, Aleksandr; Koucheryavy, Yevgeny; Ollson, Thomas (2015), "Visualizing Big Data with augmented and virtual reality: challenges and research agenda.", Journal of Big Data, 2 (22) 22, doi:10.1186/s40537-015-0031-2

- ^ Card, Mackinlay, and Shneiderman (1999), Readings in Information Visualization: Using Vision to Think, Morgan Kaufmann, pp. 6–7

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "What is data visualization?". IBM. 28 September 2021. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- ^ Brent Dykes (2019), Effective Data Storytelling: How to Drive Change with Data, Narrative and Visuals, John Wiley & Sons, p. 16

- ^ David C. LeBlanc (2004), Statistics: Concepts and Applications for Science, Jones & Bartlett Learning, pp. 35–36

- ^ Grandjean, Martin (2022). "Data Visualization for History". Handbook of Digital Public History. pp. 291–300. doi:10.1515/9783110430295-024. ISBN 9783110430295.

- ^ E.H. Chi (2013), A Framework for Visualizing Information, Springer Science & Business Media, p. xxiii

- ^ Gershon, Nahum; Page, Ward (1 August 2001). "What storytelling can do for information visualization". Communications of the ACM. 44 (8): 31–37. doi:10.1145/381641.381653. S2CID 7666107.

- ^ Mason, Betsy (November 12, 2019). "Why scientists need to be better at data visualization". Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-110919-1.

- ^ O'Donoghue, Seán I.; Baldi, Benedetta Frida; Clark, Susan J.; Darling, Aaron E.; Hogan, James M.; Kaur, Sandeep; Maier-Hein, Lena; McCarthy, Davis J.; Moore, William J.; Stenau, Esther; Swedlow, Jason R.; Vuong, Jenny; Procter, James B. (2018-07-20). "Visualization of Biomedical Data". Annual Review of Biomedical Data Science. 1 (1): 275–304. doi:10.1146/annurev-biodatasci-080917-013424. hdl:10453/125943. S2CID 199591321. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ Leo Yu-Ho Lo; Ayush Gupta; Kento Shigyo; Aoyu Wu; Enrico Bertini; Huamin Qu, Misinformed by Visualization: What Do We Learn From Misinformative Visualizations?

- ^ Börner, K.; Bueckle, A.; Ginda, M. (2019), "Data visualization literacy: Definitions, conceptual frameworks, exercises, and assessments", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116 (6): 1857–1864, Bibcode:2019PNAS..116.1857B, doi:10.1073/pnas.1807180116, PMC 6369751, PMID 30718386

- ^ a b Benjamin B. Bederson and Ben Shneiderman (2003). The Craft of Information Visualization: Readings and Reflections, Morgan Kaufmann ISBN 1-55860-915-6.

- ^ James J. Thomas and Kristin A. Cook (Ed.) (2005). Illuminating the Path: The R&D Agenda for Visual Analytics Archived 2008-09-29 at the Wayback Machine. National Visualization and Analytics Center. p.30

- ^ a b "Stephen Few-Perceptual Edge-Selecting the Right Graph for Your Message-2004" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-10-05. Retrieved 2014-09-08.

- ^ "10 Examples of Interactive Map Data Visualizations". Tableau.

- ^ Engebretsen, Martin; Helen, Kennedy, eds. (2020-04-16). Data Visualization in Society. Amsterdam University Press. doi:10.5117/9789463722902_ch02. ISBN 978-90-485-4313-7.

- ^ Vitaly Friedman (2008) "Data Visualization and Infographics" Archived 2008-07-22 at the Wayback Machine in: Graphics, Monday Inspiration, January 14, 2008.

- ^ Viegas, Fernanda; Wattenberg, Martin (April 19, 2011). "How To Make Data Look Sexy". CNN. Archived from the original on May 6, 2011. Retrieved May 7, 2017.

- ^ a b Frits H. Post, Gregory M. Nielson and Georges-Pierre Bonneau (2002). Data Visualization: The State of the Art. Research paper TU delft, 2002. Archived 2009-10-07 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Tukey, John (1977). Exploratory Data Analysis. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-07616-0.

- ^ techatstate (7 August 2013). "Tech@State: Data Visualization - Keynote by Dr Edward Tufte". Archived from the original on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 29 November 2016 – via YouTube.

- ^ Cleveland, W. S.; McGill, R. (1985). "Graphical perception and graphical methods for analyzing scientific data". Science. 229 (4716): 828–33. Bibcode:1985Sci...229..828C. doi:10.1126/science.229.4716.828. PMID 17777913. S2CID 16342041.

- ^ Tufte, Edward R. (1983). The Visual Display of Quantitative Information (2nd ed.). Cheshire, Connecticut, US: Graphics Press LLC. ISBN 9780318029924.

- ^ a b c Tufte, Edward (1983). The Visual Display of Quantitative Information. Cheshire, Connecticut: Graphics Press. ISBN 0-9613921-4-2. Archived from the original on 2013-01-14. Retrieved 2019-08-10.

- ^ "Telling Visual Stories About Data - Congressional Budget Office". www.cbo.gov. Archived from the original on 2014-12-04. Retrieved 2014-11-27.

- ^ a b Kosara, Robert (16 July 2007). "Visualization Criticism - The Missing Link Between Information Visualization and Art". 2007 11th International Conference Information Visualization (IV '07). pp. 631–636. doi:10.1109/IV.2007.130. ISBN 978-0-7695-2900-4. ISSN 1550-6037.

- ^ Ziemkiewicz, C.; Kosara, R. (2009). "Embedding Information Visualization within Visual Representation". Advances in Information and Intelligent Systems. Studies in Computational Intelligence. Vol. 251. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 307–326. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-04141-9_15. ISBN 978-3-642-04140-2.

- ^ Buchanan, Larry; Letherby, Lauren (June 22, 2022). "Who Stops a 'Bad Guy With a Gun'?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 22, 2022.

Data source: Advanced Law Enforcement Rapid Response Training Center

- ^ "Stephen Few-Perceptual Edge-Graph Selection Matrix" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-10-05. Retrieved 2014-09-08.

- ^ a b "Steven Few-Tapping the Power of Visual Perception-September 2004" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-10-05. Retrieved 2014-10-08.

- ^ a b c "Data Visualization for Human Perception". The Interaction Design Foundation. Archived from the original on 2015-11-23. Retrieved 2015-11-23.

- ^ "Visualization" (PDF). SFU. SFU lecture. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-01-22. Retrieved 2015-11-22.

- ^ Graham, Fiona (2012-04-17). "Can images stop data overload?". BBC News. Retrieved 2020-07-30.

- ^ a b c Friendly, Michael (2008). "A Brief History of Data Visualization". Handbook of Data Visualization. Springer-Verlag. pp. 15–56. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-33037-0_2. ISBN 9783540330370. S2CID 62626937.

- ^ Whitehouse, D. (9 August 2000). "Ice Age star map discovered". BBC News. Archived from the original on 6 January 2018. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- ^ Dragicevic, Pierre; Jansen, Yvonne (2012). "List of Physical Visualizations and Related Artefacts". Archived from the original on 2018-01-13. Retrieved 2018-01-12.

- ^ Jansen, Yvonne; Dragicevic, Pierre; Isenberg, Petra; Alexander, Jason; Karnik, Abhijit; Kildal, Johan; Subramanian, Sriram; Hornbæk, Kasper (2015). "Opportunities and challenges for data physicalization". Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems: 3227–3236. Archived from the original on 2018-01-13. Retrieved 2018-01-12.

- ^ a b Friendly, Michael (2001). "Milestones in the history of thematic cartography, statistical graphics, and data visualization". Archived from the original on 2014-04-14.

- ^ Funkhouser, Howard Gray (January 1936). "A Note on a Tenth Century Graph". Osiris. 1: 260–262. doi:10.1086/368425. JSTOR 301609. S2CID 144492131.

- ^ "Data visualization: definition, examples, tools, advice [guide 2020]". Market research consulting. 2020-12-09. Retrieved 2020-12-09.

- ^ Friendly, Michael (2006). "A Brief History of Data Visualization" (PDF). York University. Springer-Verlag. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-05-08. Retrieved 2015-11-22.

- ^ G. Scott Owen (1999). History of Visualization Archived 2012-10-08 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed Jan 19, 2010.

- ^ "NY gets new boot camp for data scientists: It's free but harder to get into than Harvard". Venture Beat. Archived from the original on 2016-02-15. Retrieved 2016-02-21.

- ^ Interactive Data Visualization

- ^ a b Bulmer, Michael (2013). A Portable Introduction to Data Analysis. The University of Queensland: Publish on Demand Centre. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-1-921723-10-0.

- ^ "Steven Few-Selecting the Right Graph for Your Message-September 2004" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-10-05. Retrieved 2014-09-08.

- ^ Lengler, Ralph; Eppler, Martin. J. "Periodic Table of Visualization Methods". www.visual-literacy.org. Archived from the original on 16 March 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- ^ Munzner, Tamara; Maguire, Eamonn (2015). Visualization analysis & design. A.K. Peters visualization series. Boca Raton London New York: CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4665-0891-0.

- ^ Kahn, Brian (June 17, 2019). "This Striking Climate Change Visualization Is Now Customizable for Any Place on Earth". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on June 26, 2019. Developed in May 2018 by Ed Hawkins, University of Reading.

- ^ Mooney, Chris (11 May 2016). "This scientist just changed how we think about climate change with one GIF". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 6 February 2019.

Ed Hawkins took these monthly temperature data and plotted them in the form of a spiral, so that for each year, there are twelve points, one for each month, around the center of a circle – with warmer temperatures farther outward and colder temperatures nearer inward.

- ^ Swayne, Deborah (1999). "Introduction to the special issue on interactive graphical data analysis: What is interaction?". Computational Statistics. 14 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1007/PL00022700. S2CID 86788346.

- ^ American Statistics Association, Statistical Graphics Section. "Video Lending Library". Archived from the original on 2021-01-20. Retrieved 2021-02-17.

- ^ Michael Friendly (2008). "Milestones in the history of thematic cartography, statistical graphics, and data visualization" Archived 2008-09-11 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Data Visualization: Modern Approaches" Archived 2008-07-22 at the Wayback Machine. in: Graphics, August 2, 2007

- ^ Frits H. Post, Gregory M. Nielson and Georges-Pierre Bonneau (2002). Data Visualization: The State of the Art Archived 2009-10-07 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b c d e f Berinato, Scott (June 2016). "Visualizations That Really Work". Harvard Business Review: 92–100.

- ^ Faisal, Sarah; Blandford, Ann; Potts, Henry WW (2013). "Making sense of personal health information: Challenges for information visualization" (PDF). Health Informatics Journal. 19 (3): 198–217. doi:10.1177/1460458212465213. PMID 23981395. S2CID 3825148.

- ^ Kosara, Robert (11 November 2013). "A Guide to the Quality of Different Visualization Venues". eagereyes. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

Further reading

[edit]- Few, Stephen (2012). Show me the numbers: designing tables and graphs to enlighten (2 ed.). Analytics Press. ISBN 9780970601971. — Practical guide focusing on business applications of data visualisation.

- Healy, Kieran (2019). Data Visualisation: A Practical Introduction. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-18161-5. — Modern guide that balances technical skills with design principles, featuring R-based examples.

- Schwabish, Jonathan A. 2014. "An Economist's Guide to Visualizing Data." Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28 (1): 209–34. — Specialised guide for economic data visualisation with principles applicable across domains.

- Wilke, Claus O. (2018). Fundamentals of Data Visualisation. O'Reilly. ISBN 978-1-4920-3108-6. Archived from the original on 2019-10-19. Retrieved 2018-09-22. — Comprehensive guide focusing on principles of effective visualisation with real-world examples, available in print and open-access online resource.

- Tufte, Edward R. (2015). The visual display of quantitative information (2 ed.). Graphics Press. ISBN 9780961392147. — Classic foundational text on visualisation principles that remains influential decades after its first publication.

External links

[edit]- Milestones in the History of Thematic Cartography, Statistical Graphics, and Data Visualization, An illustrated chronology of innovations by Michael Friendly and Daniel J. Denis.

- Duke University-Christa Kelleher Presentation-Communicating through infographics-visualizing scientific & engineering information, 2015