Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Doomsday argument

View on Wikipedia

The doomsday argument (DA), or Carter catastrophe, is a probabilistic argument that aims to predict the total number of humans who will ever live. It argues that if a human's birth rank is randomly sampled from the set of all humans who will ever live, it is improbable that one would be at the extreme beginning. This implies that the total number of humans is unlikely to be much larger than the number of humans born so far.

The doomsday argument was originally proposed by the astrophysicist Brandon Carter in 1983,[1] leading to the initial name of the Carter catastrophe. The argument was subsequently championed by the philosopher John A. Leslie and has since been independently conceived by J. Richard Gott[2] and Holger Bech Nielsen.[3]

Summary

[edit]The premise of the argument is as follows: suppose that the total number of human beings who will ever exist is fixed. If so, the likelihood of a randomly selected person existing at a particular time in history would be proportional to the total population at that time. Given this, the argument posits that a person alive today should adjust their expectations about the future of the human race because their existence provides information about the total number of humans that will ever live.

If the total number of humans who were born or will ever be born is denoted by , then the Copernican principle suggests that any one human is equally likely to find themselves in any position of the total population .

is uniformly distributed on (0,1) even after learning the absolute position . For example, there is a 95% chance that is in the interval (0.05,1), that is . In other words, one can assume with 95% certainty that any individual human would be within the last 95% of all the humans ever to be born. If the absolute position is known, this argument implies a 95% confidence upper bound for obtained by rearranging to give .

If Leslie's figure[4] is used, then approximately 60 billion humans have been born so far, so it can be estimated that there is a 95% chance that the total number of humans will be less than 2060 billion = 1.2 trillion. Assuming that the world population stabilizes at 10 billion and a life expectancy of 80 years, it can be estimated that the remaining 1140 billion humans will be born in 9120 years. Depending on the projection of the world population in the forthcoming centuries, estimates may vary, but the argument states that it is unlikely that more than 1.2 trillion humans will ever live.

Aspects

[edit]Assume, for simplicity, that the total number of humans who will ever be born is 60 billion (N1), or 6,000 billion (N2).[5] If there is no prior knowledge of the position that a currently living individual, X, has in the history of humanity, one may instead compute how many humans were born before X, and arrive at say 59,854,795,447, which would necessarily place X among the first 60 billion humans who have ever lived.

It is possible to sum the probabilities for each value of N and, therefore, to compute a statistical 'confidence limit' on N. For example, taking the numbers above, it is 99% certain that N is smaller than 6 trillion.

Note that as remarked above, this argument assumes that the prior probability for N is flat, or 50% for N1 and 50% for N2 in the absence of any information about X. On the other hand, it is possible to conclude, given X, that N2 is more likely than N1 if a different prior is used for N. More precisely, Bayes' theorem tells us that P(N|X) = P(X|N)P(N)/P(X), and the conservative application of the Copernican principle tells us only how to calculate P(X|N). Taking P(X) to be flat, we still have to assume the prior probability P(N) that the total number of humans is N. If we conclude that N2 is much more likely than N1 (for example, because producing a larger population takes more time, increasing the chance that a low probability but cataclysmic natural event will take place in that time), then P(X|N) can become more heavily weighted towards the bigger value of N. A further, more detailed discussion, as well as relevant distributions P(N), are given below in the Rebuttals section.

The doomsday argument does not say that humanity cannot or will not exist indefinitely. It does not put any upper limit on the number of humans that will ever exist nor provide a date for when humanity will become extinct. An abbreviated form of the argument does make these claims, by confusing probability with certainty. However, the actual conclusion for the version used above is that there is a 95% chance of extinction within 9,120 years and a 5% chance that some humans will still be alive at the end of that period. (The precise numbers vary among specific doomsday arguments.)

Variations

[edit]This argument has generated a philosophical debate, and no consensus has yet emerged on its solution. The variants described below produce the DA by separate derivations.

Gott's formulation: "vague prior" total population

[edit]Gott specifically proposes the functional form for the prior distribution of the number of people who will ever be born (N). Gott's DA used the vague prior distribution:

- .

where

- P(N) is the probability prior to discovering n, the total number of humans who have yet been born.

- The constant, k, is chosen to normalize the sum of P(N). The value chosen is not important here, just the functional form (this is an improper prior, so no value of k gives a valid distribution, but Bayesian inference is still possible using it.)

Since Gott specifies the prior distribution of total humans, P(N), Bayes' theorem and the principle of indifference alone give us P(N|n), the probability of N humans being born if n is a random draw from N:

This is Bayes' theorem for the posterior probability of the total population ever born of N, conditioned on population born thus far of n. Now, using the indifference principle:

- .

The unconditioned n distribution of the current population is identical to the vague prior N probability density function,[note 1] so:

- ,

giving P (N | n) for each specific N (through a substitution into the posterior probability equation):

- .

The easiest way to produce the doomsday estimate with a given confidence (say 95%) is to pretend that N is a continuous variable (since it is very large) and integrate over the probability density from N = n to N = Z. (This will give a function for the probability that N ≤ Z):

Defining Z = 20n gives:

- .

This is the simplest Bayesian derivation of the doomsday argument:

- The chance that the total number of humans that will ever be born (N) is greater than twenty times the total that have been is below 5%

The use of a vague prior distribution seems well-motivated as it assumes as little knowledge as possible about N, given that some particular function must be chosen. It is equivalent to the assumption that the probability density of one's fractional position remains uniformly distributed even after learning of one's absolute position (n).

Gott's "reference class" in his original 1993 paper was not the number of births, but the number of years "humans" had existed as a species, which he put at 200,000. Also, Gott tried to give a 95% confidence interval between a minimum survival time and a maximum. Because of the 2.5% chance that he gives to underestimating the minimum, he has only a 2.5% chance of overestimating the maximum. This equates to 97.5% confidence that extinction occurs before the upper boundary of his confidence interval, which can be used in the integral above with Z = 40n, and n = 200,000 years:

This is how Gott produces a 97.5% confidence of extinction within N ≤ 8,000,000 years. The number he quoted was the likely time remaining, N − n = 7.8 million years. This was much higher than the temporal confidence bound produced by counting births, because it applied the principle of indifference to time. (Producing different estimates by sampling different parameters in the same hypothesis is Bertrand's paradox.) Similarly, there is a 97.5% chance that the present lies in the first 97.5% of human history, so there is a 97.5% chance that the total lifespan of humanity will be at least

- ;

In other words, Gott's argument gives a 95% confidence that humans will go extinct between 5,100 and 7.8 million years in the future.

Gott has also tested this formulation against the Berlin Wall and Broadway and off-Broadway plays.[6]

Leslie's argument differs from Gott's version in that he does not assume a vague prior probability distribution for N. Instead, he argues that the force of the doomsday argument resides purely in the increased probability of an early doomsday once you take into account your birth position, regardless of your prior probability distribution for N. He calls this the probability shift.

Heinz von Foerster argued that humanity's abilities to construct societies, civilizations and technologies do not result in self-inhibition. Rather, societies' success varies directly with population size. Von Foerster found that this model fits some 25 data points from the birth of Jesus to 1958, with only 7% of the variance left unexplained. Several follow-up letters (1961, 1962, ...) were published in Science showing that von Foerster's equation was still on track. The data continued to fit up until 1973. The most remarkable thing about von Foerster's model was it predicted that the human population would reach infinity or a mathematical singularity, on Friday, November 13, 2026. In fact, von Foerster did not imply that the world population on that day could actually become infinite. The real implication was that the world population growth pattern followed for many centuries prior to 1960 was about to come to an end and be transformed into a radically different pattern. Note that this prediction began to be fulfilled just in a few years after the "doomsday" argument was published.[note 2]

Reference classes

[edit]The reference class from which n is drawn, and of which N is the ultimate size, is a crucial point of contention in the doomsday argument argument. The "standard" doomsday argument hypothesis skips over this point entirely, merely stating that the reference class is the number of "people". Given that you are human, the Copernican principle might be used to determine if you were born exceptionally early, however the term "human" has been heavily contested on practical and philosophical reasons. According to Nick Bostrom, consciousness is (part of) the discriminator between what is in and what is out of the reference class, and therefore extraterrestrial intelligence might have a significant impact on the calculation.[citation needed]

The following sub-sections relate to different suggested reference classes, each of which has had the standard doomsday argument applied to it.

SSSA: Sampling from observer-moments

[edit]Nick Bostrom, considering observation selection effects, has produced a Self-Sampling Assumption (SSA): "that you should think of yourself as if you were a random observer from a suitable reference class". If the "reference class" is the set of humans to ever be born, this gives N < 20n with 95% confidence (the standard doomsday argument). However, he has refined this idea to apply to observer-moments rather than just observers. He has formalized this as:[7]

- The strong self-sampling assumption (SSSA): Each observer-moment should reason as if it were randomly selected from the class of all observer-moments in its reference class.

An application of the principle underlying SSSA (though this application is nowhere expressly articulated by Bostrom), is: If the minute in which you read this article is randomly selected from every minute in every human's lifespan, then (with 95% confidence) this event has occurred after the first 5% of human observer-moments. If the mean lifespan in the future is twice the historic mean lifespan, this implies 95% confidence that N < 10n (the average future human will account for twice the observer-moments of the average historic human). Therefore, the 95th percentile extinction-time estimate in this version is 4560 years.

Counterarguments

[edit]This section's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (November 2010) |

We are in the earliest 5%, a priori

[edit]One counterargument to the doomsday argument agrees with its statistical methods but disagrees with its extinction-time estimate. This position requires justifying why the observer cannot be assumed to be randomly selected from the set of all humans ever to be born, which implies that this set is not an appropriate reference class. By disagreeing with the doomsday argument, it implies that the observer is within the first 5% of humans to be born.

By analogy, if one is a member of 50,000 people in a collaborative project, the reasoning of the doomsday argument implies that there will never be more than a million members of that project, within a 95% confidence interval. However, if one's characteristics are typical of an early adopter, rather than typical of an average member over the project's lifespan, then it may not be reasonable to assume one has joined the project at a random point in its life. For instance, the mainstream of potential users will prefer to be involved when the project is nearly complete. However, if one were to enjoy the project's incompleteness, it is already known that he or she is unusual, before the discovery of his or her early involvement.

If one has measurable attributes that set one apart from the typical long-run user, the project doomsday argument can be refuted based on the fact that one could expect to be within the first 5% of members, a priori. The analogy to the total-human-population form of the argument is that confidence in a prediction of the distribution of human characteristics that places modern and historic humans outside the mainstream implies that it is already known, before examining n, that it is likely to be very early in N. This is an argument for changing the reference class.

For example, if one is certain that 99% of humans who will ever live will be cyborgs, but that only a negligible fraction of humans who have been born to date are cyborgs, one could be equally certain that at least one hundred times as many people remain to be born as have been.

Robin Hanson's paper sums up these criticisms of the doomsday argument:[8]

All else is not equal; we have good reasons for thinking we are not randomly selected humans from all who will ever live.

Human extinction is distant, a posteriori

[edit]The a posteriori observation that extinction level events are rare could be offered as evidence that the doomsday argument's predictions are implausible; typically, extinctions of dominant species happen less often than once in a million years. Therefore, it is argued that human extinction is unlikely within the next ten millennia. (Another probabilistic argument, drawing a different conclusion than the doomsday argument.)

In Bayesian terms, this response to the doomsday argument says that our knowledge of history (or ability to prevent disaster) produces a prior marginal for N with a minimum value in the trillions. If N is distributed uniformly from 1012 to 1013, for example, then the probability of N < 1,200 billion inferred from n = 60 billion will be extremely small. This is an equally impeccable Bayesian calculation, rejecting the Copernican principle because we must be 'special observers' since there is no likely mechanism for humanity to go extinct within the next hundred thousand years.

This response is accused of overlooking the technological threats to humanity's survival, to which earlier life was not subject, and is specifically rejected by most[by whom? – Discuss] academic critics of the doomsday argument (arguably excepting Robin Hanson).

The prior N distribution may make n very uninformative

[edit]Robin Hanson argues that N's prior may be exponentially distributed:[8]

Here, c and q are constants. If q is large, then our 95% confidence upper bound is on the uniform draw, not the exponential value of N.

The simplest way to compare this with Gott's Bayesian argument is to flatten the distribution from the vague prior by having the probability fall off more slowly with N (than inverse proportionally). This corresponds to the idea that humanity's growth may be exponential in time with doomsday having a vague prior probability density function in time. This would mean that N, the last birth, would have a distribution looking like the following:

This prior N distribution is all that is required (with the principle of indifference) to produce the inference of N from n, and this is done in an identical way to the standard case, as described by Gott (equivalent to = 1 in this distribution):

Substituting into the posterior probability equation):

Integrating the probability of any N above xn:

For example, if x = 20, and = 0.5, this becomes:

Therefore, with this prior, the chance of a trillion births is well over 20%, rather than the 5% chance given by the standard DA. If is reduced further by assuming a flatter prior N distribution, then the limits on N given by n become weaker. An of one reproduces Gott's calculation with a birth reference class, and around 0.5 could approximate his temporal confidence interval calculation (if the population were expanding exponentially). As (gets smaller) n becomes less and less informative about N. In the limit this distribution approaches an (unbounded) uniform distribution, where all values of N are equally likely. This is Page et al.'s "Assumption 3", which they find few reasons to reject, a priori. (Although all distributions with are improper priors, this applies to Gott's vague-prior distribution also, and they can all be converted to produce proper integrals by postulating a finite upper population limit.) Since the probability of reaching a population of size 2N is usually thought of as the chance of reaching N multiplied by the survival probability from N to 2N it follows that Pr(N) must be a monotonically decreasing function of N, but this doesn't necessarily require an inverse proportionality.[8]

Infinite expectation

[edit]Another objection to the doomsday argument is that the expected total human population is actually infinite.[9] The calculation is as follows:

- The total human population N = n/f, where n is the human population to date and f is our fractional position in the total.

- We assume that f is uniformly distributed on (0,1].

- The expectation of N is

For a similar example of counterintuitive infinite expectations, see the St. Petersburg paradox.

Self-indication assumption: The possibility of not existing at all

[edit]One objection is that the possibility of a human existing at all depends on how many humans will ever exist (N). If this is a high number, then the possibility of their existing is higher than if only a few humans will ever exist. Since they do indeed exist, this is evidence that the number of humans that will ever exist is high.[10]

This objection, originally by Dennis Dieks (1992),[11] is now known by Nick Bostrom's name for it: the "Self-Indication Assumption objection". It can be shown that some SIAs prevent any inference of N from n (the current population).[12]

The SIA has been defended by Matthew Adelstein, arguing that all alternatives to the SIA imply the soundness of the doomsday argument, and other even stranger conclusions.[13]

Caves' rebuttal

[edit]The Bayesian argument by Carlton M. Caves states that the uniform distribution assumption is incompatible with the Copernican principle, not a consequence of it.[14]

Caves gives a number of examples to argue that Gott's rule is implausible. For instance, he says, imagine stumbling into a birthday party, about which you know nothing:

Your friendly enquiry about the age of the celebrant elicits the reply that she is celebrating her (tp=) 50th birthday. According to Gott, you can predict with 95% confidence that the woman will survive between [50]/39 = 1.28 years and 39[×50] = 1,950 years into the future. Since the wide range encompasses reasonable expectations regarding the woman's survival, it might not seem so bad, till one realizes that [Gott's rule] predicts that with probability 1/2 the woman will survive beyond 100 years old and with probability 1/3 beyond 150. Few of us would want to bet on the woman's survival using Gott's rule. (See Caves' online paper below.)

Cave's example example exposes a weakness in J. Richard Gott's "Copernicus method" DA: it does not specify when the "Copernicus method" can be applied. But this criticism is less effective against more refined versions of the argument. Epistemological refinements of Gott's argument by philosophers such as Nick Bostrom specify that:

- Knowing the absolute birth rank (n) must give no information on the total population (N).

Careful DA variants specified with this rule aren't shown implausible by Caves' "Old Lady" example above, because the woman's age is given prior to the estimate of her lifespan. Since human age gives an estimate of survival time (via actuarial tables) Caves' Birthday party age-estimate could not fall into the class of DA problems defined with this proviso.

To produce a comparable "Birthday Party Example" of the carefully specified Bayesian DA, we would need to completely exclude all prior knowledge of likely human life spans; in principle this could be done (e.g.: hypothetical Amnesia chamber). However, this would remove the modified example from everyday experience. To keep it in the everyday realm the lady's age must be hidden prior to the survival estimate being made. (Although this is no longer exactly the DA, it is much more comparable to it.)

Without knowing the lady's age, the DA reasoning produces a rule to convert the birthday (n) into a maximum lifespan with 50% confidence (N). Gott's Copernicus method rule is simply: Prob (N < 2n) = 50%. How accurate would this estimate turn out to be? Western demographics are now fairly uniform across ages, so a random birthday (n) could be (very roughly) approximated by a U(0,M] draw where M is the maximum lifespan in the census. In this 'flat' model, everyone shares the same lifespan so N = M. If n happens to be less than (M)/2 then Gott's 2n estimate of N will be under M, its true figure. The other half of the time 2n underestimates M, and in this case (the one Caves highlights in his example) the subject will die before the 2n estimate is reached. In this "flat demographics" model Gott's 50% confidence figure is proven right 50% of the time.

Self-referencing doomsday argument rebuttal

[edit]Some philosophers have suggested that only people who have contemplated the doomsday argument (DA) belong in the reference class "human". If that is the appropriate reference class, Carter defied his own prediction when he first described the argument (to the Royal Society). An attendant could have argued thus:

Presently, only one person in the world understands the Doomsday argument, so by its own logic there is a 95% chance that it is a minor problem which will only ever interest twenty people, and I should ignore it.

Jeff Dewynne and Professor Peter Landsberg suggested that this line of reasoning will create a paradox for the doomsday argument:[9]

If a member of the Royal Society did pass such a comment, it would indicate that they understood the DA sufficiently well that in fact 2 people could be considered to understand it, and thus there would be a 5% chance that 40 or more people would actually be interested. Also, of course, ignoring something because you only expect a small number of people to be interested in it is extremely short sighted—if this approach were to be taken, nothing new would ever be explored, if we assume no a priori knowledge of the nature of interest and attentional mechanisms.

Conflation of future duration with total duration

[edit]Various authors have argued that the doomsday argument rests on an incorrect conflation of future duration with total duration. This occurs in the specification of the two time periods as "doom soon" and "doom deferred" which means that both periods are selected to occur after the observed value of the birth order. A rebuttal in Pisaturo (2009)[15] argues that the doomsday argument relies on the equivalent of this equation:

- ,

- where:

- X = the prior information;

- Dp = the data that past duration is tp;

- HFS = the hypothesis that the future duration of the phenomenon will be short;

- HFL = the hypothesis that the future duration of the phenomenon will be long;

- HTS = the hypothesis that the total duration of the phenomenon will be short—i.e., that tt, the phenomenon's total longevity, = tTS;

- HTL = the hypothesis that the total duration of the phenomenon will be long—i.e., that tt, the phenomenon's total longevity, = tTL, with tTL > tTS.

Pisaturo then observes:

- Clearly, this is an invalid application of Bayes' theorem, as it conflates future duration and total duration.

Pisaturo takes numerical examples based on two possible corrections to this equation: considering only future durations and considering only total durations. In both cases, he concludes that the doomsday argument's claim, that there is a "Bayesian shift" in favor of the shorter future duration, is fallacious.

This argument is also echoed in O'Neill (2014).[16] In this work O'Neill argues that a unidirectional "Bayesian Shift" is an impossibility within the standard formulation of probability theory and is contradictory to the rules of probability. As with Pisaturo, he argues that the doomsday argument conflates future duration with total duration by specification of doom times that occur after the observed birth order. According to O'Neill:

- The reason for the hostility to the doomsday argument and its assertion of a "Bayesian shift" is that many people who are familiar with probability theory are implicitly aware of the absurdity of the claim that one can have an automatic unidirectional shift in beliefs regardless of the actual outcome that is observed. This is an example of the "reasoning to a foregone conclusion" that arises in certain kinds of failures of an underlying inferential mechanism. An examination of the inference problem used in the argument shows that this suspicion is indeed correct, and the doomsday argument is invalid. (pp. 216-217)

Confusion over the meaning of confidence intervals

[edit]Gelman and Robert[17] assert that the doomsday argument confuses frequentist confidence intervals with Bayesian credible intervals. Suppose that every individual knows their number n and uses it to estimate an upper bound on N. Every individual has a different estimate, and these estimates are constructed so that 95% of them contain the true value of N and the other 5% do not. This, say Gelman and Robert, is the defining property of a frequentist lower-tailed 95% confidence interval. But, they say, "this does not mean that there is a 95% chance that any particular interval will contain the true value." That is, while 95% of the confidence intervals will contain the true value of N, this is not the same as N being contained in the confidence interval with 95% probability. The latter is a different property and is the defining characteristic of a Bayesian credible interval. Gelman and Robert conclude:

the Doomsday argument is the ultimate triumph of the idea, beloved among Bayesian educators, that our students and clients do not really understand Neyman–Pearson confidence intervals and inevitably give them the intuitive Bayesian interpretation.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The only probability density functions that must be specified a priori are:

- Pr(N) - the ultimate number of people that will be born, assumed by J. Richard Gott to have a vague prior distribution, Pr(N) = k/N

- Pr(n|N) - the chance of being born in any position based on a total population N - all DA forms assume the Copernican principle, making Pr(n|N) = 1/N

- ^ See, for example, Introduction to Social Macrodynamics by Andrey Korotayev et al.

References

[edit]- ^ Brandon Carter; McCrea, W. H. (1983). "The anthropic principle and its implications for biological evolution". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. A310 (1512): 347–363. Bibcode:1983RSPTA.310..347C. doi:10.1098/rsta.1983.0096. S2CID 92330878.

- ^ J. Richard Gott, III (1993). "Implications of the Copernican principle for our future prospects". Nature. 363 (6427): 315–319. Bibcode:1993Natur.363..315G. doi:10.1038/363315a0. S2CID 4252750.

- ^ Holger Bech Nielsen (1989). "Random dynamics and relations between the number of fermion generations and the fine structure constants". Acta Physica Polonica. B20: 427–468.

- ^ Oliver, Jonathan; Korb, Kevin (1998). "A Bayesian Analysis of the Doomsday Argument". Philosophy. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.49.5899.

- ^ Korb, K. (1998). "A refutation of the doomsday argument". Mind. 107 (426): 403–410. doi:10.1093/mind/107.426.403.

- ^ Timothy Ferris (July 12, 1999). "How to Predict Everything". The New Yorker. Retrieved September 3, 2010.

- ^ Bostrom, Nick (2005). "Self-Location and Observation Selection Theory". anthropic-principle.com. Retrieved 2023-07-02.

- ^ a b c "Critiquing the Doomsday Argument". mason.gmu.edu. Retrieved 2023-06-17.

- ^ a b Monton, Bradley; Roush, Sherri (2001-11-20). "Gott's Doomsday Argument". philsci-archive.pitt.edu. Retrieved 2023-06-17.

- ^ Olum, Ken D. (2002). "The doomsday argument and the number of possible observers". The Philosophical Quarterly. 52 (207): 164. arXiv:gr-qc/0009081. doi:10.1111/1467-9213.00260. S2CID 14707647.

- ^ Dieks, Dennis (2005-01-13). "Reasoning About the Future: Doom and Beauty". philsci-archive.pitt.edu. Retrieved 2023-06-17.

- ^ Bostrom, Nick (2002). Anthropic Bias: Observational Selection Effects in Science and Philosophy. New York & London: Routledge. pp. 124–126. ISBN 0-415-93858-9.

- ^ Adelstein, Matthew (2024). "Alternatives to the self-indication assumption are doomed". Synthese. 204 23: 1–17. doi:10.1007/s11229-024-04686-w.

- ^ Caves, Carlton M. (2008). "Predicting future duration from present age: Revisiting a critical assessment of Gott's rule". arXiv:0806.3538 [astro-ph].

- ^ Ronald Pisaturo (2009). "Past Longevity as Evidence for the Future". Philosophy of Science. 76: 73–100. doi:10.1086/599273. S2CID 122207511.

- ^ Ben O'Neill (2014). "Assessing the 'Bayesian Shift' in the Doomsday Argument". Journal of Philosophy. 111 (4): 198–218. doi:10.5840/jphil2014111412.

- ^ Andrew Gelman; Christian P. Robert (2013). "'Not Only Defended But Also Applied': The Perceived Absurdity of Bayesian Inference". The American Statistician. 67 (4): 1–5. arXiv:1006.5366. doi:10.1080/00031305.2013.760987. S2CID 10833752.

Further reading

[edit]- John A. Leslie, The End of the World: The Science and Ethics of Human Extinction, Routledge, 1998, ISBN 0-41518447-9.

- J. R. Gott III, Future Prospects Discussed, Nature, vol. 368, p. 108, 1994.

- This argument plays a central role in Stephen Baxter's science fiction book, Manifold: Time, Del Rey Books, 2000, ISBN 0-345-43076-X.

- The same principle plays a major role in the Dan Brown novel, Inferno, Corgy Books, ISBN 978-0-552-16959-2

- Poundstone, William, The Doomsday Calculation: How an Equation that Predicts the Future Is Transforming Everything We Know About Life and the Universe. 2019 Little, Brown Spark. Description & arrow/scrollable preview. Also summarised in Poundstone's essay, "Math Says Humanity May Have Just 760 Years Left". The Wall Street Journal, updated June 27, 2019. ISBN 9783164440707

External links

[edit]This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (November 2023) |

- The Doomsday argument category on PhilPapers

- A non-mathematical, unpartisan introduction to the DA

- Nick Bostrom's response to Korb and Oliver

- Nick Bostrom's annotated collection of references

- Kopf, Krtouš & Page's early (1994) refutation based on the SIA, which they called "Assumption 2".

- The Doomsday argument and the number of possible observers by Ken Olum In 1993 J. Richard Gott used his "Copernicus method" to predict the lifetime of Broadway shows. One part of this paper uses the same reference class as an empirical counter-example to Gott's method.

- A Critique of the Doomsday Argument by Robin Hanson

- A Third Route to the Doomsday Argument by Paul Franceschi, Journal of Philosophical Research, 2009, vol. 34, pp. 263–278

- Chambers' Ussherian Corollary Objection

- Caves' Bayesian critique of Gott's argument. C. M. Caves, "Predicting future duration from present age: A critical assessment", Contemporary Physics 41, 143-153 (2000).

- C.M. Caves, "Predicting future duration from present age: Revisiting a critical assessment of Gott's rule.

- "Infinitely Long Afterlives and the Doomsday Argument" by John Leslie shows that Leslie has recently modified his analysis and conclusion (Philosophy 83 (4) 2008 pp. 519–524): Abstract—A recent book of mine defends three distinct varieties of immortality. One of them is an infinitely lengthy afterlife; however, any hopes of it might seem destroyed by something like Brandon Carter's 'doomsday argument' against viewing ourselves as extremely early humans. The apparent difficulty might be overcome in two ways. First, if the world is non-deterministic then anything on the lines of the doomsday argument may prove unable to deliver a strongly pessimistic conclusion. Secondly, anything on those lines may break down when an infinite sequence of experiences is in question.

- Mark Greenberg, "Apocalypse Not Just Now" in London Review of Books

- Laster: A simple webpage applet giving the min & max survival times of anything with 50% and 95% confidence requiring only that you input how old it is. It is designed to use the same mathematics as J. Richard Gott's form of the DA, and was programmed by sustainable development researcher Jerrad Pierce.

- PBS Space Time The Doomsday Argument

Doomsday argument

View on GrokipediaHistorical Origins

Brandon Carter's Initial Formulation (1974)

Brandon Carter, a theoretical astrophysicist at the University of Cambridge, initially formulated the doomsday argument as part of his application of anthropic reasoning to cosmological and biological questions during a presentation at the Kraków symposium on "Confrontation of Cosmological Theories with Observational Data" in February 1973, with the proceedings published in 1974.[1] In his paper "Large Number Coincidences and the Anthropic Principle in Cosmology," Carter integrated the argument with the weak anthropic principle, which posits that the universe must permit the existence of observers like ourselves, and the Copernican principle, emphasizing that humans should not presume an atypical position in the sequence of all observers.[1] This framing highlighted observer selection effects, where the fact of our existence as latecomers—after approximately humans have already been born—constrains probabilistic inferences about the total human population .[8] The core probabilistic reasoning assumes that an individual's birth rank (our approximate position in the human lineage, around the th) is randomly sampled from the uniform distribution over 1 to , conditional on .[1] Carter employed a prior distribution for , reflecting ignorance about scale in a manner consistent with scale-invariant reasoning in cosmology.[1] The likelihood for then yields a posterior , normalized such that the cumulative probability for .[1] This implies a high probability that is not vastly larger than ; specifically, there is approximately 95% confidence that .[1] ![{\displaystyle P={\frac {19}{20}}}}[float-right] Under assumptions of modest future population growth or stabilization, this translates to human extinction occurring within a timeframe on the order of years from the present, as the remaining human births would deplete without exceeding the bounded total.[9] Carter's approach thus served as an early illustration of how self-selection among observers biases expectations away from scenarios with extraordinarily long human histories, privileging empirical positioning over optimistic priors about indefinite survival.[1] This initial presentation laid the groundwork for later elaborations but remained tied to first-principles probabilistic updating under anthropic constraints, without invoking multiverse or infinite measures.[1]John Leslie's Elaboration and Popularization (1980s–1990s)

Philosopher John Leslie substantially expanded Brandon Carter's initial doomsday argument formulation during the late 1980s and early 1990s, transforming it from an esoteric probabilistic observation into a prominent tool for assessing human extinction risks. In works such as his 1989 contributions and subsequent papers, Leslie emphasized the argument's reliance on self-locating uncertainty about one's position in the total sequence of human observers, positing that the low observed birth rank—approximately the 60-70 billionth human—indicates a modest total human population rather than an astronomically large one implied by indefinite survival.[10] This elaboration countered optimistic projections by conditioning probabilities on actual existence rather than hypothetical vast futures, aligning with a view that prioritizes observable data over unsubstantiated assumptions of perpetual growth. Leslie popularized the argument through accessible thought experiments, notably the urn analogy, wherein an observer unaware of drawing from a small urn (10 tickets) or large one (millions) who selects an early-numbered ticket rationally infers the smaller total, mirroring humanity's early temporal position as evidence against scenarios of trillions more future humans.[11] He detailed this in his 1993 paper "Doom and Probabilities," defending it against critiques like the possibility of selection biases by invoking Bayesian updating based on empirical observer ranks, and argued that dismissing the inference requires rejecting standard inductive reasoning.[12] These analogies rendered the argument intuitive, shifting focus from abstract cosmology to practical implications for species longevity. Culminating in his 1996 book The End of the World: The Science and Ethics of Human Extinction, Leslie integrated the doomsday reasoning with analyses of anthropogenic threats, estimating a substantial probability—around one in three for extinction by the third millennium—that doomsday looms soon unless risks are mitigated, without presupposing priors favoring eternal persistence.[13] He critiqued overreliance on technological salvation narratives, advocating instead for precautionary measures grounded in the argument's probabilistic caution, and linked it to ethical duties to future generations by highlighting how ignoring early-observer status underestimates extinction odds from events like nuclear conflict or environmental collapse. This work elevated the doomsday argument in philosophical discourse on anthropic principles and existential hazards, influencing subsequent debates on human survival probabilities.[14]J. Richard Gott's Independent Development (1993)

In 1993, astrophysicist J. Richard Gott III published "Implications of the Copernican Principle for Our Future Prospects" in Nature, independently deriving a probabilistic argument akin to the doomsday argument by assuming humans occupy a typical, non-privileged position within the total span of human existence.[15] Gott framed this under the Copernican principle, positing that observers should expect to find themselves neither unusually early nor late in any phenomenon's history, without relying on specific priors about its total length.[15] He illustrated the approach with temporal examples, such as a hypothetical random visit to the New York World's Fair in 1964 shortly after its opening, where the observed elapsed time since inception (t_p) implied a high likelihood of brief remaining duration, consistent with the fair's actual demolition the following year.[16] Gott's formulation treats the observer's position as uniformly distributed over the total duration T, yielding a posterior distribution for T given elapsed time t that reflects a "vague" prior uniform over logarithmic scales of duration, effectively P(T) \propto 1/T.[17] The likelihood P(t|T) = 1/T for T > t then produces P(T|t) \propto 1/T^2. Integrating this posterior, the probability that total duration satisfies N \leq 20n (where n analogs elapsed "units," such as births or time) is 95%, or P(N \leq 20n) = 19/20.[15] For a 95% confidence interval excluding the outermost 2.5% tails of the uniform fraction f = t/T, the remaining duration falls between t/39 and 39t.[17] Applied to humanity, Gott adapted this to cumulative human births as the measure of "existence," estimating around 50–60 billion humans born by 1993 and treating the current observer's birth rank as randomly sampled from total N.[5] This yields a 95% probability that fewer than about 19–39 times that number remain unborn, implying human extinction within roughly 8,000 years assuming sustained birth rates of approximately 100 million per year.[5] Gott emphasized this as a first-principles Bayesian update, avoiding strong assumptions about longevity by relying on the self-sampling uniformity and the vague logarithmic prior to derive conservative bounds on future prospects.[15]Core Logical Framework

Basic Probabilistic Reasoning

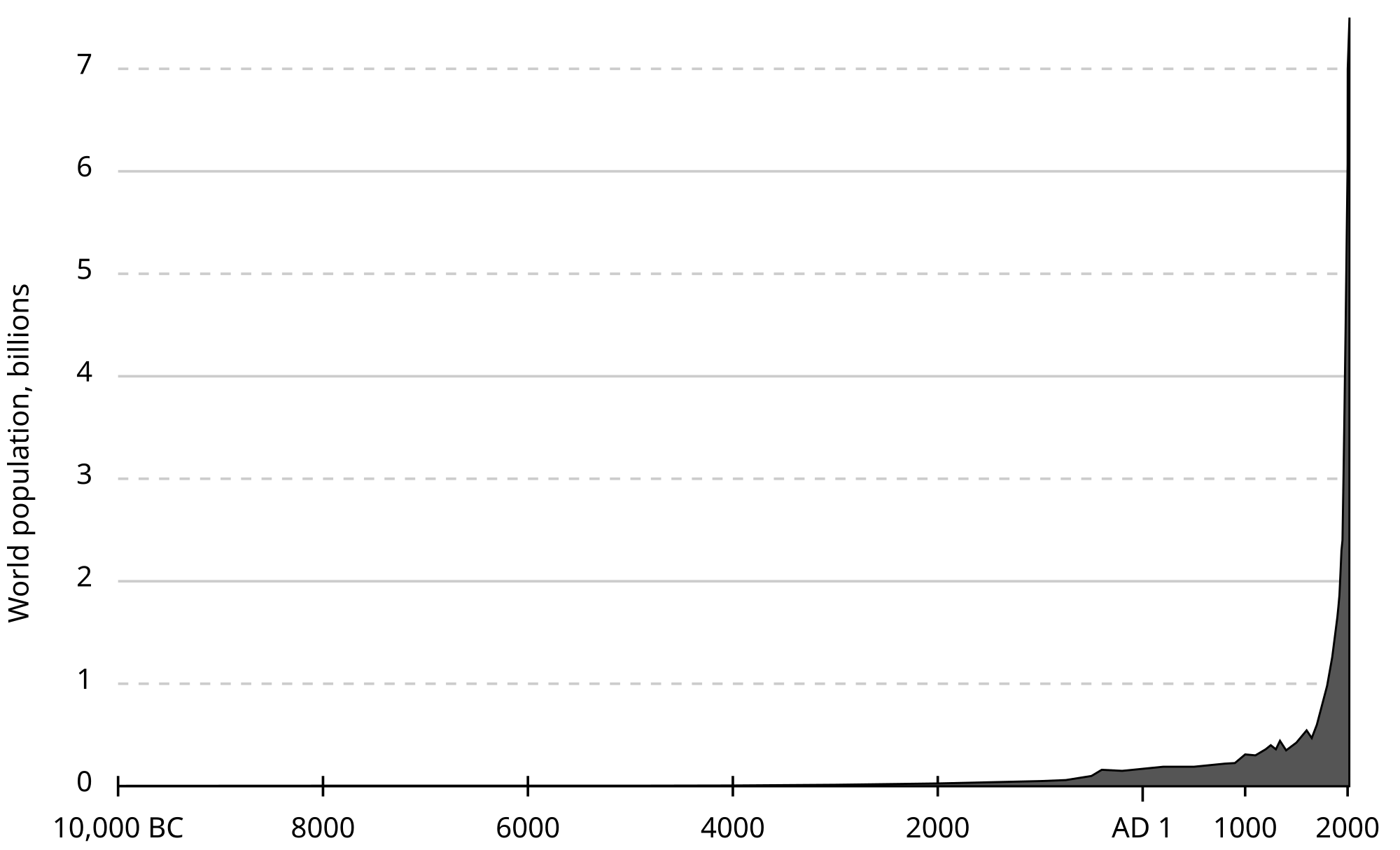

The basic probabilistic reasoning of the Doomsday argument treats an individual's birth rank n among all humans who will ever exist as a random sample uniformly drawn from the integers 1 to N, where N denotes the unknown total number of humans.[1] Observing n—empirically estimated at approximately 117 billion based on historical birth records through late 2025—serves as data that updates beliefs about N toward smaller values, as large N would make such an "early" rank unlikely under the sampling assumption. Demographers estimate that approximately 117 billion humans have been born since the emergence of modern Homo sapiens around 200,000–300,000 years ago. With the world population at about 8.2 billion in late 2025, people alive today represent roughly 7% of all humans who have ever lived, meaning the dead outnumber the living by about 14:1. These figures, primarily from the Population Reference Bureau (PRB), highlight that early human history featured very slow growth and high mortality (life expectancy often ~10–30 years), with most births occurring in recent centuries amid the population explosion post-Industrial Revolution.[3] In Bayesian terms, the likelihood P(n|N) equals 1/N for N ≥ n (and 0 otherwise), reflecting the uniform sampling.[1] A scale-invariant prior P(N) ∝ 1/N for N ≥ n—chosen for its lack of arbitrary scale preference in the absence of other information—yields a posterior P(N|n) ∝ 1/N2.[1] In the continuous approximation, normalization gives P(N|n) = n / N2 for N ≥ n, and the cumulative distribution follows as P(N ≤ Z | n) = 1 - n/Z for Z ≥ n.[1] This posterior implies high probability for N modestly exceeding n: for instance, P(N ≤ 20n | n) = 19/20 = 0.95.[1] With n ≈ 1.17 × 1011, total N < 2.34 × 1012 at 95% posterior probability, constraining future births to under 2 trillion despite past cumulative totals.[3] The logic incorporates an observer selection effect: birth ranks beyond N are impossible, so conditioning on existence biases against scenarios with small N and late ranks, but the observed relatively early n (as a fraction of potential vast N) countervails by favoring bounded totals.[1] Empirical demographic data, including decelerating global birth rates (from 140 million annually in 2015–2020 toward projected peaks near 141 million by 2040–2045 before decline), render assumptions of indefinite exponential growth or infinite N empirically unmotivated and inconsistent with observed trends toward population stabilization.[18] Counterarguments positing ad hoc expansions, such as interstellar colonization yielding unbounded humans, lack causal mechanisms grounded in current technological or biological constraints and fail to override the update from sampled n.[1]Key Assumptions: Random Sampling and Observer Selection

The Doomsday argument hinges on the self-sampling assumption (SSA), which holds that a given observer should reason as if they constitute a randomly selected member from the aggregate set of all observers within the pertinent reference class.[19][20] In its canonical formulation, this entails viewing one's birth order—estimated at approximately the 117 billionth human—as drawn uniformly at random from the interval spanning the first to the Nth human, where N denotes the ultimate total human population. Demographers estimate that approximately 117 billion humans have been born since the emergence of modern Homo sapiens around 200,000–300,000 years ago. With the world population at about 8.2 billion in late 2025, people alive today represent roughly 7% of all humans who have ever lived, meaning the dead outnumber the living by about 14:1. These figures, primarily from the Population Reference Bureau (PRB), highlight that early human history featured very slow growth and high mortality (life expectancy often ~10–30 years), with most births occurring in recent centuries amid the population explosion post-Industrial Revolution.[3][21][22] This random sampling premise presupposes an equiprobability across individuals (or, in some variants, observer-moments) without bias toward temporal position, thereby enabling Bayesian updating on the evidence of one's ordinal rank to constrain plausible values of N.[23] Critics of alternative anthropic principles, such as the self-indication assumption, argue that SSA aligns more closely with causal realism by conditioning solely on realized observers rather than potential ones, avoiding inflation of probabilities for unobserved worlds.[20] Complementing this is the observer selection effect, whereby the very act of self-observation filters evidentiary scenarios to those permitting the observer's existence and capacity to deliberate on such matters.[24] In the Doomsday context, this effect underscores that empirical data—such as the observed human population to date—conditions probabilistic inferences, privileging hypotheses under which an early-to-mid sequence observer like oneself emerges with high likelihood, as opposed to those mandating vast posteriors where such positioning would be anomalously improbable.[21] This selection mechanism counters dismissals invoking unverified multiplicities (e.g., simulated realities or infinite multiverses), which might dilute the sampling uniformity by positing countless non-actual duplicates; instead, it enforces a parsimonious focus on the concrete causal chain yielding detectable evidence.[25] Empirical grounding derives from elementary Bayesian principles: the likelihood P(n|N) approximates 1/N under uniform sampling, updating a prior distribution over N without presupposing extended futures or exotic physics.[1] Thus, the argument's validity pivots on these assumptions' alignment with probabilistic realism, where observer-centric evidence rigorously narrows existential timelines absent ad hoc expansions of the sample space.[24]Role of Reference Classes in the Argument

The reference class in the Doomsday argument represents the total population of observers—ordinarily defined as all humans who will ever exist—from which one's own existence is treated as a random draw ordered by birth rank. This class forms the foundation for the probabilistic inference, as the observer's position n within it updates beliefs about the overall size N, yielding a posterior distribution concentrated around values of N comparable to n rather than vastly exceeding it. Brandon Carter's 1983 formulation specified the class in terms of human observers capable of self-referential temporal awareness, rooted in demographic patterns of births rather than speculative extensions to non-human or hypothetical entities.[1] John Leslie reinforced this by insisting on a reference class aligned with causal and empirical continuity, such as the sequence of all Homo sapiens births, to preserve the argument's predictive power against doomsday; he cautioned against classes either too narrow (e.g., limited to modern eras) or excessively broad (e.g., encompassing undefined posthumans), which could arbitrarily weaken the sampling assumption. Cumulative human births, estimated at 117 billion as of late 2025, place contemporary individuals around the 95th percentile under uniform priors, empirically favoring classes at the human scale over more abstract ones that ignore observed population dynamics. Demographers estimate that approximately 117 billion humans have been born since the emergence of modern Homo sapiens around 200,000–300,000 years ago. With the world population at about 8.2 billion in late 2025, people alive today represent roughly 7% of all humans who have ever lived, meaning the dead outnumber the living by about 14:1. These figures, primarily from the Population Reference Bureau (PRB), highlight that early human history featured very slow growth and high mortality (life expectancy often ~10–30 years), with most births occurring in recent centuries amid the population explosion post-Industrial Revolution.[26][3] A key debate concerns the granularity of the reference class, pitting discrete units like individual human lives (tied to birth events) against continuous observer-moments (each instance of subjective experience). The birth-based class, central to Carter and Leslie's versions, implies a finite total N on the order of 10-20 times current cumulative births to render one's rank typical, consistent with historical growth data showing exponential but decelerating rates since the Industrial Revolution. Observer-moment classes, by contrast, could permit longer futures if future observers accrue more moments per life (e.g., through longevity or enhanced cognition), yet this hinges on unverified assumptions about experiential rates, which empirical neuroscience pegs at roughly constant for humans—about 3 billion seconds of consciousness per lifetime—without causal evidence for drastic future increases that would dilute the doomsday signal.[27][3]Formal Variants and Extensions

Self-Sampling Assumption (SSA) Approach

The Self-Sampling Assumption (SSA) posits that a given observer should reason as if they are a randomly selected member from the actual set of all observers in the relevant reference class, such as all humans who will ever exist.[21] This approach treats the observer's position within the sequence of births as uniformly distributed across the total number, conditional on the total N being fixed.[20] Applied to the Doomsday Argument, SSA implies that discovering one's birth rank n—estimated at approximately 117 billion for a typical human born around 2025—provides evidence favoring smaller values of N, as early ranks are more probable under small-N hypotheses.[21] Formally, SSA yields a likelihood function where the probability of observing birth rank n given total humans N is for and 0 otherwise, reflecting uniform random sampling from the realized population.[20] To compute the posterior , a prior on N is required; a scale-invariant prior (Jeffreys prior for positive scale parameters) is often employed to reflect ignorance about the order of magnitude of N.[21] The posterior then becomes for , derived via Bayes' theorem:normalized over where the integral .[20] The cumulative distribution under this posterior is for , obtained by integrating:

Setting yields the result.[20] Thus, the posterior median is (where ), and there is a 95% probability that .[21] For n ≈ 1.17 × 10^{11}, this predicts a median total human population of roughly 2.34 × 10^{11}, implying a substantial chance of extinction within centuries, assuming birth rates of order 10^8 per year.[20] In variants incorporating successive sampling—such as the Strong SSA (SSSA), which applies sampling to observer-moments rather than static observers—SSA reinforces doomy posteriors by modeling births as a sequential process, where early positions in a growing population still favor total durations not vastly exceeding current elapsed time.[22] This contrasts with priors expecting indefinitely long civilization survival, as the observed early rank updates strongly against such expansive scenarios under random sampling from the realized total.[21]

![{\displaystyle P(N\leq 40[200000])={\frac {39}{40}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4f7d1d256554fcc75d5f9282171232cb365d870f)

![{\displaystyle N={\frac {e^{U(0,q]}}{c}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d7fb9f82fbe59cac05f2d337963c9a78b9b13611)

![{\displaystyle E(N)=\int _{0}^{1}{n \over f}\,df=n[\ln(f)]_{0}^{1}=n\ln(1)-n\ln(0)=+\infty .}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1bfb1500abe5c99041c659984daa5842a642e338)

![{\displaystyle P(H_{TS}|D_{p}X)/P(H_{TL}|D_{p}X)=[P(H_{FS}|X)/P(H_{FL}|X)]\cdot [P(D_{p}|H_{TS}X)/P(D_{p}|H_{TL}X)]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/106a88e612192842779aa7d48552cdecabacc3cb)