Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Probability distribution

View on Wikipedia| Part of a series on statistics |

| Probability theory |

|---|

|

In probability theory and statistics, a probability distribution is a function that gives the probabilities of occurrence of possible events for an experiment.[1][2] It is a mathematical description of a random phenomenon in terms of its sample space and the probabilities of events (subsets of the sample space).[3]

For instance, if X is used to denote the outcome of a coin toss ("the experiment"), then the probability distribution of X would take the value 0.5 (1 in 2 or 1/2) for X = heads, and 0.5 for X = tails (assuming that the coin is fair). More commonly, probability distributions are used to compare the relative occurrence of many different random values.

Probability distributions can be defined in different ways and for discrete or for continuous variables. Distributions with special properties or for especially important applications are given specific names.

Introduction

[edit]A probability distribution is a mathematical description of the probabilities of events, subsets of the sample space. The sample space, often represented in notation by is the set of all possible outcomes of a random phenomenon being observed. The sample space may be any set: a set of real numbers, a set of descriptive labels, a set of vectors, a set of arbitrary non-numerical values, etc. For example, the sample space of a coin flip could be Ω = {"heads", "tails"}.

To define probability distributions for the specific case of random variables (so the sample space can be seen as a numeric set), it is common to distinguish between discrete and continuous random variables. In the discrete case, it is sufficient to specify a probability mass function assigning a probability to each possible outcome (e.g. when throwing a fair die, each of the six digits “1” to “6”, corresponding to the number of dots on the die, has probability The probability of an event is then defined to be the sum of the probabilities of all outcomes that satisfy the event; for example, the probability of the event "the die rolls an even value" is In contrast, when a random variable takes values from a continuum then by convention, any individual outcome is assigned probability zero. For such continuous random variables, only events that include infinitely many outcomes such as intervals have probability greater than 0.

For example, consider measuring the weight of a piece of ham in the supermarket, and assume the scale can provide arbitrarily many digits of precision. Then, the probability that it weighs exactly 500 g must be zero because no matter how high the level of precision chosen, it cannot be assumed that there are no non-zero decimal digits in the remaining omitted digits ignored by the precision level.

However, for the same use case, it is possible to meet quality control requirements such as that a package of "500 g" of ham must weigh between 490 g and 510 g with at least 98% probability. This is possible because this measurement does not require as much precision from the underlying equipment.

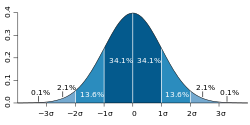

Continuous probability distributions can be described by means of the cumulative distribution function, which describes the probability that the random variable is no larger than a given value (i.e., P(X ≤ x) for some x. The cumulative distribution function is the area under the probability density function from -∞ to x, as shown in figure 1.[4]

Most continuous probability distributions encountered in practice are not only continuous but also absolutely continuous. Such distributions can be described by their probability density function. Informally, the probability density of a random variable describes the infinitesimal probability that takes any value — that is as becomes is arbitrarily small. The probability that lies in a given interval can be computed rigorously by integrating the probability density function over that interval.[5]

General probability definition

[edit]Let be a probability space, be a measurable space, and be a -valued random variable. Then the probability distribution of is the pushforward measure of the probability measure onto induced by . Explicitly, this pushforward measure on is given by for

Any probability distribution is a probability measure on (in general different from , unless happens to be the identity map).[citation needed]

A probability distribution can be described in various forms, such as by a probability mass function or a cumulative distribution function. One of the most general descriptions, which applies for absolutely continuous and discrete variables, is by means of a probability function whose input space is a σ-algebra, and gives a real number probability as its output, particularly, a number in .

The probability function can take as argument subsets of the sample space itself, as in the coin toss example, where the function was defined so that P(heads) = 0.5 and P(tails) = 0.5. However, because of the widespread use of random variables, which transform the sample space into a set of numbers (e.g., , ), it is more common to study probability distributions whose argument are subsets of these particular kinds of sets (number sets),[6] and all probability distributions discussed in this article are of this type. It is common to denote as the probability that a certain value of the variable belongs to a certain event .[7][8]

The above probability function only characterizes a probability distribution if it satisfies all the Kolmogorov axioms, that is:

- , so the probability is non-negative

- , so no probability exceeds

- for any countable disjoint family of sets

The concept of probability function is made more rigorous by defining it as the element of a probability space , where is the set of possible outcomes, is the set of all subsets whose probability can be measured, and is the probability function, or probability measure, that assigns a probability to each of these measurable subsets .[9]

Probability distributions usually belong to one of two classes. A discrete probability distribution is applicable to the scenarios where the set of possible outcomes is discrete (e.g. a coin toss, a roll of a die) and the probabilities are encoded by a discrete list of the probabilities of the outcomes; in this case the discrete probability distribution is known as probability mass function. On the other hand, absolutely continuous probability distributions are applicable to scenarios where the set of possible outcomes can take on values in a continuous range (e.g. real numbers), such as the temperature on a given day. In the absolutely continuous case, probabilities are described by a probability density function, and the probability distribution is by definition the integral of the probability density function.[7][5][8] The normal distribution is a commonly encountered absolutely continuous probability distribution. More complex experiments, such as those involving stochastic processes defined in continuous time, may demand the use of more general probability measures.

A probability distribution whose sample space is one-dimensional (for example real numbers, list of labels, ordered labels or binary) is called univariate, while a distribution whose sample space is a vector space of dimension 2 or more is called multivariate. A univariate distribution gives the probabilities of a single random variable taking on various different values; a multivariate distribution (a joint probability distribution) gives the probabilities of a random vector – a list of two or more random variables – taking on various combinations of values. Important and commonly encountered univariate probability distributions include the binomial distribution, the hypergeometric distribution, and the normal distribution. A commonly encountered multivariate distribution is the multivariate normal distribution.

Besides the probability function, the cumulative distribution function, the probability mass function and the probability density function, the moment generating function and the characteristic function also serve to identify a probability distribution, as they uniquely determine an underlying cumulative distribution function.[10]

Terminology

[edit]Some key concepts and terms, widely used in the literature on the topic of probability distributions, are listed below.[1]

Basic terms

[edit]- Random variable: takes values from a sample space; probabilities describe which values and set of values are more likely taken.

- Event: set of possible values (outcomes) of a random variable that occurs with a certain probability.

- Probability function or probability measure: describes the probability that the event occurs.[11]

- Cumulative distribution function: function evaluating the probability that will take a value less than or equal to for a random variable (only for real-valued random variables).

- Quantile function: the inverse of the cumulative distribution function. Gives such that, with probability , will not exceed .

Discrete probability distributions

[edit]- Discrete probability distribution: for many random variables with finitely or countably infinitely many values.

- Probability mass function (pmf): function that gives the probability that a discrete random variable is equal to some value.

- Frequency distribution: a table that displays the frequency of various outcomes in a sample.

- Relative frequency distribution: a frequency distribution where each value has been divided (normalized) by a number of outcomes in a sample (i.e. sample size).

- Categorical distribution: for discrete random variables with a finite set of values.

Absolutely continuous probability distributions

[edit]- Absolutely continuous probability distribution: for many random variables with uncountably many values.

- Probability density function (pdf) or probability density: function whose value at any given sample (or point) in the sample space (the set of possible values taken by the random variable) can be interpreted as providing a relative likelihood that the value of the random variable would equal that sample.

Related terms

[edit]- Support: set of values that can be assumed with non-zero probability (or probability density in the case of a continuous distribution) by the random variable. For a random variable , it is sometimes denoted as .

- Tail:[12] the regions close to the bounds of the random variable, if the pmf or pdf are relatively low therein. Usually has the form , or a union thereof.

- Head:[12] the region where the pmf or pdf is relatively high. Usually has the form .

- Expected value or mean: the weighted average of the possible values, using their probabilities as their weights; or the continuous analog thereof.

- Median: the value such that the set of values less than the median, and the set greater than the median, each have probabilities no greater than one-half.

- Mode: for a discrete random variable, the value with highest probability; for an absolutely continuous random variable, a location at which the probability density function has a local peak.

- Quantile: the q-quantile is the value such that .

- Variance: the second moment of the pmf or pdf about the mean; an important measure of the dispersion of the distribution.

- Standard deviation: the square root of the variance, and hence another measure of dispersion.

- Symmetry: a property of some distributions in which the portion of the distribution to the left of a specific value (usually the median) is a mirror image of the portion to its right.

- Skewness: a measure of the extent to which a pmf or pdf "leans" to one side of its mean. The third standardized moment of the distribution.

- Kurtosis: a measure of the "fatness" of the tails of a pmf or pdf. The fourth standardized moment of the distribution.

Cumulative distribution function

[edit]In the special case of a real-valued random variable, the probability distribution can equivalently be represented by a cumulative distribution function instead of a probability measure. The cumulative distribution function of a random variable with regard to a probability distribution is defined as

The cumulative distribution function of any real-valued random variable has the properties:

- is non-decreasing;

- is right-continuous;

- ;

- and ; and

- .

Conversely, any function that satisfies the first four of the properties above is the cumulative distribution function of some probability distribution on the real numbers.[13]

Any probability distribution can be decomposed as the mixture of a discrete, an absolutely continuous and a singular continuous distribution,[14] and thus any cumulative distribution function admits a decomposition as the convex sum of the three according cumulative distribution functions.

Discrete probability distribution

[edit]

A discrete probability distribution is the probability distribution of a random variable that can take on only a countable number of values[15] (almost surely)[16] which means that the probability of any event can be expressed as a (finite or countably infinite) sum: where is a countable set with . Thus the discrete random variables (i.e. random variables whose probability distribution is discrete) are exactly those with a probability mass function . In the case where the range of values is countably infinite, these values have to decline to zero fast enough for the probabilities to add up to 1. For example, if for , the sum of probabilities would be .

Well-known discrete probability distributions used in statistical modeling include the Poisson distribution, the Bernoulli distribution, the binomial distribution, the geometric distribution, the negative binomial distribution and categorical distribution.[3] When a sample (a set of observations) is drawn from a larger population, the sample points have an empirical distribution that is discrete, and which provides information about the population distribution. Additionally, the discrete uniform distribution is commonly used in computer programs that make equal-probability random selections between a number of choices.

Cumulative distribution function

[edit]A real-valued discrete random variable can equivalently be defined as a random variable whose cumulative distribution function increases only by jump discontinuities—that is, its cdf increases only where it "jumps" to a higher value, and is constant in intervals without jumps. The points where jumps occur are precisely the values which the random variable may take. Thus the cumulative distribution function has the form The points where the cdf jumps always form a countable set; this may be any countable set and thus may even be dense in the real numbers.

Dirac delta representation

[edit]A discrete probability distribution is often represented with Dirac measures, also called one-point distributions (see below), the probability distributions of deterministic random variables. For any outcome , let be the Dirac measure concentrated at . Given a discrete probability distribution, there is a countable set with and a probability mass function . If is any event, then or in short,

Similarly, discrete distributions can be represented with the Dirac delta function as a generalized probability density function , where which means for any event [17]

Indicator-function representation

[edit]For a discrete random variable , let be the values it can take with non-zero probability. Denote These are disjoint sets, and for such sets It follows that the probability that takes any value except for is zero, and thus one can write as except on a set of probability zero, where is the indicator function of . This may serve as an alternative definition of discrete random variables.

One-point distribution

[edit]A special case is the discrete distribution of a random variable that can take on only one fixed value, in other words, a Dirac measure. Expressed formally, the random variable has a one-point distribution if it has a possible outcome such that [18] All other possible outcomes then have probability 0. Its cumulative distribution function jumps immediately from 0 before to 1 at . It is closely related to a deterministic distribution, which cannot take on any other value, while a one-point distribution can take other values, though only with probability 0. For most practical purposes the two notions are equivalent.

Absolutely continuous probability distribution

[edit]An absolutely continuous probability distribution is a probability distribution on the real numbers with uncountably many possible values, such as a whole interval in the real line, and where the probability of any event can be expressed as an integral.[19] More precisely, a real random variable has an absolutely continuous probability distribution if there is a function such that for each interval the probability of belonging to is given by the integral of over :[20][21] This is the definition of a probability density function, so that absolutely continuous probability distributions are exactly those with a probability density function. In particular, the probability for to take any single value (that is, ) is zero, because an integral with coinciding upper and lower limits is always equal to zero. If the interval is replaced by any measurable set , the according equality still holds:

An absolutely continuous random variable is a random variable whose probability distribution is absolutely continuous.

There are many examples of absolutely continuous probability distributions: normal, uniform, chi-squared, and others.

Cumulative distribution function

[edit]Absolutely continuous probability distributions as defined above are precisely those with an absolutely continuous cumulative distribution function. In this case, the cumulative distribution function has the form where is a density of the random variable with regard to the distribution .

Note on terminology: Absolutely continuous distributions ought to be distinguished from continuous distributions, which are those having a continuous cumulative distribution function. Every absolutely continuous distribution is a continuous distribution but the inverse is not true, there exist singular distributions, which are neither absolutely continuous nor discrete nor a mixture of those, and do not have a density. An example is given by the Cantor distribution. Some authors however use the term "continuous distribution" to denote all distributions whose cumulative distribution function is absolutely continuous, i.e. refer to absolutely continuous distributions as continuous distributions.[7]

For a more general definition of density functions and the equivalent absolutely continuous measures see absolutely continuous measure.

Kolmogorov definition

[edit]In the measure-theoretic formalization of probability theory, a random variable is defined as a measurable function from a probability space to a measurable space . Given that probabilities of events of the form satisfy Kolmogorov's probability axioms, the probability distribution of is the image measure of , which is a probability measure on satisfying .[22][23][24]

Other kinds of distributions

[edit]

Absolutely continuous and discrete distributions with support on or are extremely useful to model a myriad of phenomena,[7][4] since most practical distributions are supported on relatively simple subsets, such as hypercubes or balls. However, this is not always the case, and there exist phenomena with supports that are actually complicated curves within some space or similar. In these cases, the probability distribution is supported on the image of such curve, and is likely to be determined empirically, rather than finding a closed formula for it.[25]

One example is shown in the figure to the right, which displays the evolution of a system of differential equations (commonly known as the Rabinovich–Fabrikant equations) that can be used to model the behaviour of Langmuir waves in plasma.[26] When this phenomenon is studied, the observed states from the subset are as indicated in red. So one could ask what is the probability of observing a state in a certain position of the red subset; if such a probability exists, it is called the probability measure of the system.[27][25]

This kind of complicated support appears quite frequently in dynamical systems. It is not simple to establish that the system has a probability measure, and the main problem is the following. Let be instants in time and a subset of the support; if the probability measure exists for the system, one would expect the frequency of observing states inside set would be equal in interval and , which might not happen; for example, it could oscillate similar to a sine, , whose limit when does not converge. Formally, the measure exists only if the limit of the relative frequency converges when the system is observed into the infinite future.[28] The branch of dynamical systems that studies the existence of a probability measure is ergodic theory.

Note that even in these cases, the probability distribution, if it exists, might still be termed "absolutely continuous" or "discrete" depending on whether the support is uncountable or countable, respectively.

Random number generation

[edit]Most algorithms are based on a pseudorandom number generator that produces numbers that are uniformly distributed in the half-open interval [0, 1). These random variates are then transformed via some algorithm to create a new random variate having the required probability distribution. With this source of uniform pseudo-randomness, realizations of any random variable can be generated.[29]

For example, suppose U has a uniform distribution between 0 and 1. To construct a random Bernoulli variable for some 0 < p < 1, define We thus have Therefore, the random variable X has a Bernoulli distribution with parameter p.[29]

This method can be adapted to generate real-valued random variables with any distribution: for be any cumulative distribution function F, let Finv be the generalized left inverse of also known in this context as the quantile function or inverse distribution function: Then, Finv(p) ≤ x if and only if p ≤ F(x). As a result, if U is uniformly distributed on [0, 1], then the cumulative distribution function of X = Finv(U) is F.

For example, suppose we want to generate a random variable having an exponential distribution with parameter — that is, with cumulative distribution function so , and if U has a uniform distribution on [0, 1) then has an exponential distribution with parameter [29]

Although from a theoretical point of view this method always works, in practice the inverse distribution function is unknown and/or cannot be computed efficiently. In this case, other methods (such as the Monte Carlo method) are used.

Common probability distributions and their applications

[edit]The concept of the probability distribution and the random variables which they describe underlies the mathematical discipline of probability theory, and the science of statistics. There is spread or variability in almost any value that can be measured in a population (e.g. height of people, durability of a metal, sales growth, traffic flow, etc.); almost all measurements are made with some intrinsic error; in physics, many processes are described probabilistically, from the kinetic properties of gases to the quantum mechanical description of fundamental particles. For these and many other reasons, simple numbers are often inadequate for describing a quantity, while probability distributions are often more appropriate.

The following is a list of some of the most common probability distributions, grouped by the type of process that they are related to. For a more complete list, see list of probability distributions, which groups by the nature of the outcome being considered (discrete, absolutely continuous, multivariate, etc.)

All of the univariate distributions below are singly peaked; that is, it is assumed that the values cluster around a single point. In practice, actually observed quantities may cluster around multiple values. Such quantities can be modeled using a mixture distribution.

Linear growth (e.g. errors, offsets)

[edit]- Normal distribution (Gaussian distribution), for a single such quantity; the most commonly used absolutely continuous distribution

Exponential growth (e.g. prices, incomes, populations)

[edit]- Log-normal distribution, for a single such quantity whose log is normally distributed

- Pareto distribution, for a single such quantity whose log is exponentially distributed; the prototypical power law distribution

Uniformly distributed quantities

[edit]- Discrete uniform distribution, for a finite set of values (e.g. the outcome of a fair dice)

- Continuous uniform distribution, for absolutely continuously distributed values

Bernoulli trials (yes/no events, with a given probability)

[edit]- Basic distributions:

- Bernoulli distribution, for the outcome of a single Bernoulli trial (e.g. success/failure, yes/no)

- Binomial distribution, for the number of "positive occurrences" (e.g. successes, yes votes, etc.) given a fixed total number of independent occurrences

- Negative binomial distribution, for binomial-type observations but where the quantity of interest is the number of failures before a given number of successes occurs

- Geometric distribution, for binomial-type observations but where the quantity of interest is the number of failures before the first success; a special case of the negative binomial distribution

- Related to sampling schemes over a finite population:

- Hypergeometric distribution, for the number of "positive occurrences" (e.g. successes, yes votes, etc.) given a fixed number of total occurrences, using sampling without replacement

- Beta-binomial distribution, for the number of "positive occurrences" (e.g. successes, yes votes, etc.) given a fixed number of total occurrences, sampling using a Pólya urn model (in some sense, the "opposite" of sampling without replacement)

Categorical outcomes (events with K possible outcomes)

[edit]- Categorical distribution, for a single categorical outcome (e.g. yes/no/maybe in a survey); a generalization of the Bernoulli distribution

- Multinomial distribution, for the number of each type of categorical outcome, given a fixed number of total outcomes; a generalization of the binomial distribution

- Multivariate hypergeometric distribution, similar to the multinomial distribution, but using sampling without replacement; a generalization of the hypergeometric distribution

Poisson process (events that occur independently with a given rate)

[edit]- Poisson distribution, for the number of occurrences of a Poisson-type event in a given period of time

- Exponential distribution, for the time before the next Poisson-type event occurs

- Gamma distribution, for the time before the next k Poisson-type events occur

Absolute values of vectors with normally distributed components

[edit]- Rayleigh distribution, for the distribution of vector magnitudes with Gaussian distributed orthogonal components. Rayleigh distributions are found in RF signals with Gaussian real and imaginary components.

- Rice distribution, a generalization of the Rayleigh distributions for where there is a stationary background signal component. Found in Rician fading of radio signals due to multipath propagation and in MR images with noise corruption on non-zero NMR signals.

Normally distributed quantities operated with sum of squares

[edit]- Chi-squared distribution, the distribution of a sum of squared standard normal variables; useful e.g. for inference regarding the sample variance of normally distributed samples (see chi-squared test)

- Student's t distribution, the distribution of the ratio of a standard normal variable and the square root of a scaled chi squared variable; useful for inference regarding the mean of normally distributed samples with unknown variance (see Student's t-test)

- F-distribution, the distribution of the ratio of two scaled chi squared variables; useful e.g. for inferences that involve comparing variances or involving R-squared (the squared correlation coefficient)

As conjugate prior distributions in Bayesian inference

[edit]- Beta distribution, for a single probability (real number between 0 and 1); conjugate to the Bernoulli distribution and binomial distribution

- Gamma distribution, for a non-negative scaling parameter; conjugate to the rate parameter of a Poisson distribution or exponential distribution, the precision (inverse variance) of a normal distribution, etc.

- Dirichlet distribution, for a vector of probabilities that must sum to 1; conjugate to the categorical distribution and multinomial distribution; generalization of the beta distribution

- Wishart distribution, for a symmetric non-negative definite matrix; conjugate to the inverse of the covariance matrix of a multivariate normal distribution; generalization of the gamma distribution[30]

Some specialized applications of probability distributions

[edit]- The cache language models and other statistical language models used in natural language processing to assign probabilities to the occurrence of particular words and word sequences do so by means of probability distributions.

- In quantum mechanics, the probability density of finding the particle at a given point is proportional to the square of the magnitude of the particle's wavefunction at that point (see Born rule). Therefore, the probability distribution function of the position of a particle is described by , probability that the particle's position x will be in the interval a ≤ x ≤ b in dimension one, and a similar triple integral in dimension three. This is a key principle of quantum mechanics.[31]

- Probabilistic load flow in power-flow study explains the uncertainties of input variables as probability distribution and provides the power flow calculation also in term of probability distribution.[32]

- Prediction of natural phenomena occurrences based on previous frequency distributions such as tropical cyclones, hail, time in between events, etc.[33]

Fitting

[edit]Probability distribution fitting or simply distribution fitting is the fitting of a probability distribution to a series of data concerning the repeated measurement of a variable phenomenon. The aim of distribution fitting is to predict the probability or to forecast the frequency of occurrence of the magnitude of the phenomenon in a certain interval.

There are many probability distributions (see list of probability distributions) of which some can be fitted more closely to the observed frequency of the data than others, depending on the characteristics of the phenomenon and of the distribution. The distribution giving a close fit is supposed to lead to good predictions.

In distribution fitting, therefore, one needs to select a distribution that suits the data well.See also

[edit]- Conditional probability distribution

- Empirical probability distribution

- Histogram

- Joint probability distribution

- Probability measure

- Quasiprobability distribution

- Riemann–Stieltjes integral application to probability theory

Lists

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Everitt, Brian (2006). The Cambridge Dictionary of Statistics (3rd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-24688-3. OCLC 161828328.

- ^ Ash, Robert B. (2008). Basic probability theory (Dover ed.). Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publications. pp. 66–69. ISBN 978-0-486-46628-6. OCLC 190785258.

- ^ a b Evans, Michael; Rosenthal, Jeffrey S. (2010). Probability and statistics: the science of uncertainty (2nd ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman and Co. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-4292-2462-8. OCLC 473463742.

- ^ a b Dekking, Michel (1946–) (2005). A Modern Introduction to Probability and Statistics : Understanding why and how. London, UK: Springer. ISBN 978-1-85233-896-1. OCLC 262680588.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "1.3.6.1. What is a Probability Distribution". www.itl.nist.gov. Retrieved 2020-09-10.

- ^ Walpole, R.E.; Myers, R.H.; Myers, S.L.; Ye, K. (1999). Probability and statistics for engineers. Prentice Hall.

- ^ a b c d Ross, Sheldon M. (2010). A First Course in Probability,. Pearson. ISBN 9780136079095.

- ^ a b DeGroot, Morris H.; Schervish, Mark J. (2002). Probability and Statistics. Addison-Wesley.

- ^ Billingsley, Patrick (1986). Probability and Measure. Wiley. ISBN 9780471804789.

- ^ Shephard, N.G. (1991). "From characteristic function to distribution function: a simple framework for the theory". Econometric Theory. 7 (4): 519–529. doi:10.1017/S0266466600004746. S2CID 14668369.

- ^ Chapters 1 and 2 of Vapnik (1998)

- ^ a b More information and examples can be found in the articles Heavy-tailed distribution, Long-tailed distribution, fat-tailed distribution

- ^ Erhan, Çınlar (2011). Probability and stochastics. New York: Springer. p. 57. ISBN 9780387878584.

- ^ see Lebesgue's decomposition theorem

- ^ Erhan, Çınlar (2011). Probability and stochastics. New York: Springer. p. 51. ISBN 9780387878591. OCLC 710149819.

- ^ Cohn, Donald L. (1993). Measure theory. Birkhäuser.

- ^ Khuri, André I. (March 2004). "Applications of Dirac's delta function in statistics". International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology. 35 (2): 185–195. doi:10.1080/00207390310001638313. ISSN 0020-739X. S2CID 122501973.

- ^ Fisz, Marek (1963). Probability Theory and Mathematical Statistics (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 129. ISBN 0-471-26250-1.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Rosenthal, Jeffrey (2000). A First Look at Rigorous Probability Theory. World Scientific.

- ^ Chapter 3.2 of DeGroot & Schervish (2002)

- ^ Bourne, Murray. "11. Probability Distributions - Concepts". www.intmath.com. Retrieved 2020-09-10.

- ^ Stroock, Daniel W. (1999). Probability Theory, An Analytic View (Rev. ed.). Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0521663496. OCLC 43953136.

- ^ Kolmogorov, Andrey (1950) [1933]. Foundations of the Theory of Probability. New York, USA: Chelsea Publishing Company. pp. 21–24.

- ^ Joyce, David (2014). "Axioms of Probability" (PDF). Clark University. Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- ^ a b Alligood, Kathleen T.; Sauer, T.D.; Yorke, J.A. (1996). Chaos: an introduction to dynamical systems. Springer.

- ^ Rabinovich, M.I.; Fabrikant, A.L. (1979). "Stochastic self-modulation of waves in nonequilibrium media". J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 77: 617–629. Bibcode:1979JETP...50..311R.

- ^ Section 1.9 of Ross, S.M.; Peköz, E.A. (2007). A second course in probability (PDF).

- ^ Walters, Peter (2000). An Introduction to Ergodic Theory. Springer.

- ^ a b c Dekking, Frederik Michel; Kraaikamp, Cornelis; Lopuhaä, Hendrik Paul; Meester, Ludolf Erwin (2005), "Why probability and statistics?", A Modern Introduction to Probability and Statistics, Springer London, pp. 1–11, doi:10.1007/1-84628-168-7_1, ISBN 978-1-85233-896-1

- ^ Bishop, Christopher M. (2006). Pattern recognition and machine learning. New York: Springer. ISBN 0-387-31073-8. OCLC 71008143.

- ^ Chang, Raymond; Thoman, John W. (2014). Physical Chemistry for the Chemical Sciences. [Mill Valley, California]: University Science Books. pp. 403–406. ISBN 978-1-68015-835-9. OCLC 927509011.

- ^ Chen, P.; Chen, Z.; Bak-Jensen, B. (April 2008). "Probabilistic load flow: A review". 2008 Third International Conference on Electric Utility Deregulation and Restructuring and Power Technologies. pp. 1586–1591. doi:10.1109/drpt.2008.4523658. ISBN 978-7-900714-13-8. S2CID 18669309.

- ^ Maity, Rajib (2018-04-30). Statistical methods in hydrology and hydroclimatology. Singapore. ISBN 978-981-10-8779-0. OCLC 1038418263.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Sources

[edit]- den Dekker, A. J.; Sijbers, J. (2014). "Data distributions in magnetic resonance images: A review". Physica Medica. 30 (7): 725–741. doi:10.1016/j.ejmp.2014.05.002. PMID 25059432.

- Vapnik, Vladimir Naumovich (1998). Statistical Learning Theory. John Wiley and Sons.

External links

[edit]- "Probability distribution", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

- Field Guide to Continuous Probability Distributions, Gavin E. Crooks.

- Distinguishing probability measure, function and distribution, Math Stack Exchange

Probability distribution

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Introduction

A probability distribution is a mathematical function that describes the possible outcomes of a random variable and assigns probabilities to those outcomes, providing a complete characterization of the uncertainty inherent in random processes.[1] This framework allows for the quantification of likelihoods, enabling predictions about the behavior of systems influenced by chance, from simple experiments to complex natural phenomena.[5] The origins of probability distributions trace back to the 17th century, when mathematicians Blaise Pascal and Pierre de Fermat exchanged correspondence in 1654 to resolve problems arising from games of chance, such as dividing stakes in interrupted dice games.[6] Their work laid the groundwork for systematic approaches to calculating odds and expectations in gambling scenarios, marking the birth of probability as a mathematical discipline.[6] The field was later formalized in a rigorous axiomatic framework by Andrey Kolmogorov in his 1933 monograph Foundations of the Theory of Probability, which defined probability measures on abstract spaces and unified disparate ideas into a coherent theory.[7] Probability distributions play a central role across diverse fields by modeling randomness in real-world data and processes. In statistics, they underpin inference, hypothesis testing, and estimation techniques essential for drawing conclusions from samples.[1] In physics, distributions describe particle behaviors and thermodynamic systems, such as the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution for molecular speeds.[5] Finance relies on them for risk assessment and option pricing, as seen in models like the Black-Scholes framework that assume log-normal asset returns.[8] In machine learning, probabilistic distributions form the basis for algorithms in supervised and unsupervised learning, facilitating tasks like generative modeling and uncertainty quantification.[9] Distributions are broadly classified into discrete and continuous types, reflecting the nature of the random variable's possible values. Discrete distributions apply to scenarios with countable outcomes, such as the number of heads in a series of coin flips, where each specific count has a nonzero probability.[1] Continuous distributions, in contrast, handle uncountable outcomes over intervals, like human heights measured in real numbers, where probabilities are assigned to ranges rather than exact points.[1] The cumulative distribution function serves as a fundamental tool for unifying these cases, capturing the probability that the random variable falls below a given value.[1]Definition

In probability theory, a random variable is a measurable function defined on a probability space , where is the sample space, is a -algebra of events, and is a probability measure, such that for every real number , the set belongs to .[10] This measurability ensures that probabilities of events defined in terms of can be consistently assigned. The probability distribution of a random variable is the induced probability measure on the Borel -algebra of , defined by for every Borel set , which assigns probabilities to the possible outcomes or ranges of .[10] This distribution satisfies Kolmogorov's axioms: non-negativity, meaning for all Borel sets ; additivity for disjoint countable unions, if the are disjoint; and normalization, .[10] In general, the probability distribution describes the law of , where for discrete random variables it is given by the probabilities at each point in the support, and for continuous random variables by a density function such that probabilities are obtained via integration over intervals.[10] The total probability over the support satisfies ensuring the measure is normalized across all possible outcomes.[10]Terminology

A random variable is a function that assigns a real number to each outcome in a probability space, mapping the sample space to the real numbers.[11] Random variables are classified as discrete if their possible values form a countable set, such as the integers, or continuous if they can take any value in a continuous interval of the real numbers.[12][13] The support of a probability distribution is the smallest closed set of points such that the probability of the random variable taking a value outside this set is zero, representing the set where the distribution assigns positive probability.[14][15] Parameters of a probability distribution are numerical characteristics that define its shape and location, such as the mean and variance, which respectively indicate the central tendency and spread of the distribution.[16][17] For discrete random variables, the probability mass function (PMF) is the function that assigns to each possible value the probability that the random variable equals that value.[18][19] For continuous random variables, the probability density function (PDF) is a non-negative function whose integral over any interval gives the probability that the random variable falls within that interval; such distributions are absolutely continuous with respect to the Lebesgue measure, meaning the cumulative distribution function is the integral of the PDF.[20] The expectation, also known as the mean, of a random variable is the weighted average of its possible values, where the weights are the probabilities.[21][22] The variance measures the expected squared deviation of the random variable from its mean, quantifying the dispersion of the distribution.[23][24] Two random variables are independent if the occurrence of one does not affect the probability distribution of the other, formally meaning that the joint probability is the product of the marginal probabilities for all pairs of values.[25][26] The cumulative distribution function serves as a unifying concept that defines the probability that the random variable is less than or equal to a given value, applicable to both discrete and continuous cases.[13]Cumulative Distribution Function

Properties

The cumulative distribution function (CDF) of a random variable , denoted , is defined as for , mapping to the interval .[27] This function encapsulates the probability that takes a value less than or equal to , providing a complete probabilistic description of the distribution.[28] Key properties of the CDF include non-decreasing monotonicity, right-continuity, and specific boundary behaviors. Specifically, is non-decreasing, meaning that if , then , reflecting the accumulation of probability as increases.[27] It is right-continuous at every point, so .[28] The limits satisfy and , ensuring the total probability sums to 1 over the entire real line.[27] For discrete distributions, the CDF exhibits jumps at points where the random variable has positive probability mass, with the jump size equal to ; in contrast, for continuous distributions, the CDF is continuous everywhere.[28] The explicit form of the CDF depends on whether the distribution is discrete or continuous. For a discrete random variable with probability mass function , the CDF is given by summing the probabilities up to .[27] For a continuous random variable with probability density function , it is representing the integral of the density from negative infinity to .[27] The CDF uniquely determines the probability distribution of , as any two random variables with the same CDF induce identical probability measures.[29] This uniqueness theorem ensures that the CDF serves as the canonical representation for characterizing distributions in probability theory.[30]Relation to Other Functions

The cumulative distribution function (CDF) serves as a foundational tool for deriving other key functions that characterize the distribution of a random variable . For continuous random variables, the probability density function (PDF) is directly related to the CDF through differentiation, where , assuming the CDF is absolutely continuous and differentiable.[27] This relationship implies that the CDF can be recovered by integrating the PDF: .[31] For discrete random variables, the probability mass function (PMF) is obtained via finite differences of the CDF, specifically , which for support on integers simplifies to .[19] Conversely, the CDF is the cumulative sum of the PMF: .[27] Another important function derived from the CDF is the quantile function, defined as the generalized inverse for , which provides the value below which a proportion of the distribution lies.[32] This function is particularly useful for computing percentiles and in simulation methods, such as inverse transform sampling, where uniform random variables are transformed to follow the target distribution. The quantile function inverts the CDF in the sense that and , with equality holding under continuity and strict monotonicity.[32] The survival function, often denoted , represents the probability and is widely used in reliability engineering and survival analysis to model the probability of an event not occurring by time .[33] It complements the CDF by focusing on tail probabilities and is non-increasing, with approaching 0 as goes to infinity. Additionally, the CDF enables straightforward computation of probabilities over intervals: for any real numbers , , which holds for both continuous and discrete cases due to the right-continuity of the CDF.[34] This property underscores the CDF's role in bounding and calculating distributional intervals efficiently.[27]Discrete Probability Distributions

Definition and Examples

A discrete probability distribution describes the probabilities associated with a random variable whose possible values form a countable set, such as the integers or a finite list. In this framework, the probability that the random variable takes a specific value is given by , where is the probability mass function satisfying for all and over the support, ensuring the total probability sums to unity.[35][18] These distributions assign positive probability only to countable points, with zero probability for intervals between points. The cumulative distribution function is a step function, jumping at each point with positive probability.[36] Prominent examples include the Bernoulli distribution, which models a single trial with success probability (e.g., coin flip, where and ), and the discrete uniform distribution on , which assigns equal probability to each integer (e.g., die roll).[37][38]Probability Mass Function

The probability mass function (PMF) of a discrete random variable is defined as the function , which assigns to each possible value in the support of the probability that equals .[18] This function fully characterizes the distribution of , providing the probabilities for all discrete outcomes.[39] The PMF satisfies two fundamental properties: for all in the sample space, ensuring non-negative probabilities, and , guaranteeing that the total probability over all possible outcomes is unity.[18] The support of the PMF consists of the set of all where , which may be finite, countably infinite, or a subset of the integers.[19] Key properties of the PMF enable the computation of important distributional characteristics. The expected value, or mean, of is given by , representing the long-run average value of the random variable. The variance, which measures the spread of the distribution, is , where .[23] To compute the PMF for specific distributions, standard formulas are applied. For the binomial distribution with parameters (number of trials) and (success probability), the PMF is for . For the Poisson distribution with parameter (average rate), it is for .[40] The PMF relates to the probability generating function (PGF) of , defined as , which encodes the probabilities as coefficients in its power series expansion and facilitates calculations for sums of independent random variables.[41]Continuous Probability Distributions

Definition and Examples

A continuous probability distribution, specifically an absolutely continuous one, describes the probabilities associated with a random variable whose possible values form an uncountable set, such as an interval on the real line. In this framework, the probability that the random variable falls within an open interval is computed as the integral , where is the probability density function satisfying for all and .[42][43] These distributions exhibit absolute continuity with respect to the Lebesgue measure, implying no point masses: the probability assigned to any single point is zero, for all ./03:_Distributions/3.13:_Absolute_Continuity_and_Density_Functions) The cumulative distribution function for such a distribution arises as the integral of the density function up to a given point.[43] Prominent examples include the uniform distribution on the interval , which assigns equal probability to every point within that bounded range, modeling scenarios like random selection from a continuous uniform source.[44] The exponential distribution, parameterized by a rate , captures waiting times between independent events occurring at a constant average rate, such as inter-arrival times in a Poisson process.[45] The normal distribution, defined by mean and standard deviation , produces the characteristic bell-shaped curve and serves as a foundational model for phenomena where values cluster symmetrically around the center, underpinning much of inferential statistics.Probability Density Function

For a continuous random variable with support over the real numbers, the probability density function (PDF), denoted , is a non-negative function such that the probability that falls within an interval is given by the integral , rather than the value of the function at a specific point.[31] Unlike probabilities in discrete distributions, the PDF value at any point does not represent a probability and can exceed 1, as it measures density rather than likelihood at a point; the probability of equaling exactly any single value is zero.[31] The interpretation of the PDF emphasizes that probabilities are determined by the area under the curve over an interval, providing a geometric understanding of continuous outcomes.[46] Key properties of the PDF include normalization, where , ensuring the total probability over the entire support is unity, and non-negativity, for all .[46] The expected value (mean) is computed as , and the variance as , which quantify central tendency and spread using weighted integrals over the density.[47] A classic example is the uniform distribution on the interval , where the PDF is constant: This reflects equal likelihood across the interval, with the height ensuring the area integrates to 1.[31] Another fundamental case is the exponential distribution with rate parameter , modeling waiting times or lifetimes, with PDF: Here, the density decays exponentially, capturing memoryless properties in processes like radioactive decay.[47]Other Types of Distributions

Singular Distributions

Singular distributions, also known as singular continuous distributions, are probability distributions that are neither discrete nor absolutely continuous with respect to the Lebesgue measure.[48] Their cumulative distribution function (CDF) is continuous and non-decreasing but lacks a probability density function (PDF), as the distribution assigns positive probability to sets of Lebesgue measure zero while having no point masses.[49] This contrasts with absolutely continuous distributions, where the CDF is the integral of a density function. A key property of singular distributions is that the derivative of their CDF is zero almost everywhere with respect to the Lebesgue measure, yet the CDF still increases over intervals, concentrating probability on "pathological" sets like fractals. These distributions are mutually singular with the Lebesgue measure, meaning there exists a set of measure zero that carries all the probability mass.[50] Unlike discrete distributions, they have no atoms, ensuring the CDF has no jumps. The Cantor distribution provides a canonical example of a singular continuous distribution. It is supported on the ternary Cantor set in [0,1], a compact set of Lebesgue measure zero constructed by iteratively removing middle-third intervals.[51] The CDF of the Cantor distribution, known as the Cantor-Lebesgue function or devil's staircase, is constant on the removed intervals and increases continuously from 0 to 1 over the Cantor set, resulting in a continuous but nowhere differentiable function except at countably many points. This function maps the unit interval onto [0,1] in a measure-preserving way, illustrating how probability can be distributed without density. In general, any probability distribution on the real line can be uniquely decomposed into a mixture of a discrete component (with point masses), an absolutely continuous component (with a PDF), and a singular continuous component, as per the Lebesgue decomposition theorem.[49] The singular part captures distributions that evade both atomic and density-based descriptions, highlighting the richness of measure-theoretic probability.[48]Multivariate Distributions

A multivariate probability distribution describes the joint behavior of multiple random variables, extending the univariate case to vector-valued outcomes. For a random vector taking values in , the joint cumulative distribution function (CDF) is defined as , which fully characterizes the distribution and is non-decreasing in each argument with limits and approaching 1 as all arguments go to .[52] For discrete random vectors, the joint probability mass function (PMF) specifies probabilities at each point in the support, summing to 1 over all possible outcomes. In the continuous case, the joint probability density function (PDF) satisfies , and the joint CDF relates to it via .[52] Marginal distributions are derived from the joint by eliminating variables not of interest, providing the univariate or lower-dimensional laws. For a continuous bivariate case with joint PDF , the marginal PDF of is , assuming the integral exists; similarly for discrete cases, summation replaces integration.[53] This process generalizes to higher dimensions by integrating or summing over the unwanted coordinates, yielding the marginal CDF or PMF for the retained variables. Marginals capture individual behaviors but lose information on dependencies among the variables. Independence between random variables implies no influence between their outcomes, formalized such that the joint distribution factors into marginals. Specifically, are mutually independent if the joint CDF equals the product of marginal CDFs: , or equivalently for PMFs/PDFs: or .[54] This property simplifies computations, as expectations and variances of functions separate additively. Prominent examples include the multivariate normal distribution, which generalizes the univariate normal to vectors with mean vector and covariance matrix , capturing linear correlations through its elliptical contours and central limit theorem applicability in high dimensions.[55] Copulas provide a flexible framework for modeling dependence separately from marginals, as per Sklar's theorem, which states that any joint CDF can be expressed as , where is a copula—a multivariate CDF with uniform [0,1] marginals—allowing construction of diverse dependence structures like tail dependence in finance or risk assessment.[56]Advanced Characterizations

Kolmogorov Axioms

The Kolmogorov axioms form the rigorous mathematical foundation of modern probability theory, establishing it as a branch of measure theory and providing the basis for defining probability distributions. These axioms ensure that probabilities behave consistently as a countably additive measure on a structured space of events, allowing for the precise modeling of uncertainty in both discrete and continuous settings. By abstracting probability from empirical frequencies to an axiomatic system, they enable the derivation of all key properties of distributions without reliance on specific interpretations of probability. A probability space, the fundamental structure underlying this theory, consists of a triple , where is the sample space representing all possible outcomes, is a -algebra of subsets of (known as events), and is a probability measure that assigns a non-negative real number to each event, with .[57] The -algebra ensures closure under countable unions, intersections, and complements, providing a complete framework for defining events and their probabilities. Random variables are then introduced as measurable functions , meaning that for every Borel set , the preimage .[57] The probability measure satisfies three axioms:-

Non-negativity: For every event , .

This ensures probabilities represent non-negative extents of possibility.[58] -

Normalization: .

This normalizes the total probability of the entire sample space to unity.[58] - Countable additivity: If is a countable collection of pairwise disjoint events (i.e., for ), then This axiom extends finite additivity to countable collections, crucial for handling infinite sample spaces in continuous distributions.[58]

![{\displaystyle [0,1]\subseteq \mathbb {R} }](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/042e529c93e86b5d03b1e1cd6ddcc50e89761c03)

![{\displaystyle f:\mathbb {R} \to [0,\infty ]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f8544ec4fd60d201e49cacb3afd640e760798489)

![{\displaystyle I=[a,b]\subset \mathbb {R} }](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1cad8a9865c17ed0c40a9e3f5eb3fe4a18df765e)

![{\displaystyle [a,b]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9c4b788fc5c637e26ee98b45f89a5c08c85f7935)

![{\displaystyle \gamma :[a,b]\rightarrow \mathbb {R} ^{n}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/58e103c376cd9ea50b5c12c8f5398ded4d2a3577)

![{\displaystyle [t_{1},t_{2}]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6e35e13fa8221f864808f15cafa3d1467b5d78ce)

![{\displaystyle [t_{2},t_{3}]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/82eae695d40fda9d1b713787d35efa48d9a95478)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}F(x)=u&\Leftrightarrow 1-e^{-\lambda x}=u\\[2pt]&\Leftrightarrow e^{-\lambda x}=1-u\\[2pt]&\Leftrightarrow -\lambda x=\ln(1-u)\\[2pt]&\Leftrightarrow x={\frac {-1}{\lambda }}\ln(1-u)\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4fb889e8427ec79417200e4c016790ef0d20c446)