Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

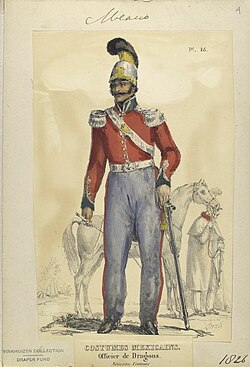

Dragoon

View on Wikipedia

Dragoons were originally a class of mounted infantry, who used horses for mobility, but dismounted to fight on foot. From the early 17th century onward, dragoons were increasingly also employed as conventional cavalry and trained for combat with swords and firearms from horseback.[1] While their use goes back to the late 16th century, dragoon regiments were established in most European armies during the 17th and early 18th centuries; they provided greater mobility than regular infantry but were far less expensive than cavalry.

The name reputedly derives from a type of firearm, called a dragon, which was a handgun version of a blunderbuss, carried by dragoons of the French Army.[2][3] The title has been retained in modern times by a number of armoured or ceremonial mounted regiments.

Origins and name

[edit]

The establishment of dragoons evolved from the practice of sometimes transporting infantry by horse when speed of movement was needed. During the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire in the 16th century, Spanish conquistadors fought on horse with arquebuses, prefiguring the origin of European dragoons.[4] In the Spanish army, dragoons were initially mounted infantry, trained to fight both on horseback and dismounted. They were a type of cavalry that could perform a variety of roles, including scouting, raiding, and direct combat. Dragoons played a significant role in the Spanish army where they were known for their versatile combat capabilities and distinctive yellow uniforms.

In 1552, Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma, mounted several companies of infantry on pack horses to achieve surprise, another example being that used by Louis of Nassau in 1572 during operations near Mons in Hainaut, when 500 infantry were transported this way.[5] It is also suggested the first dragoons were raised by the Marshal de Brissac in 1600.[6] According to old German literature, dragoons were invented by Count Ernst von Mansfeld, one of the greatest German military commanders, in the early 1620s. There are other instances of mounted infantry predating this. However Mansfeld, who had learned his profession in Hungary and the Netherlands, often used horses to make his foot troops more mobile, creating what was called an armée volante (French for 'flying army').

The origin of the name remains disputed and obscure. It possibly derives from an early weapon, a short wheellock, called a dragon because its muzzle was decorated with a dragon's head. The practice comes from a time when all gunpowder weapons had distinctive names, including the culverin, serpentine, falcon, falconet, etc.[7] It is also sometimes claimed a galloping infantryman with his loose coat and the burning match resembled a dragon.[1] It has also been asserted that the name was coined by Mansfeld as a comparison to dragons represented as "spitting fire and being swift on the wing".[8] Finally, it has been suggested that the name derives from the German tragen or the Dutch dragen, both being the verb to carry in their respective languages. Howard Reid claims the name and role descend from the Latin Draconarius.[9]

Use as a verb

[edit]Dragoon is occasionally used as a verb meaning to subjugate or persecute by the imposition of troops; and by extension to compel by any violent measures or threats. The term dates from 1689, when dragoons were used by the French monarchy to persecute Protestants, particularly by forcing Protestants to lodge a dragoon (dragonnades) in their house to watch over them at the householder's expense.[10]

Early history and role

[edit]Early dragoons were not organized in squadrons or troops as were cavalry, but in companies like the infantry. Their commissioned and non-commissioned officers bore infantry ranks, while they used drummers, not buglers, to communicate orders on the battlefield. The flexibility of mounted infantry made dragoons a useful arm, especially when employed for what would now be termed "internal security" against smugglers or civil unrest, and on line of communication security duties.

In Britain, companies of dragoons were first raised during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms and prior to 1645 either served as independent troops or were attached to cavalry units. When the New Model Army was first approved by Parliament in January 1645, it included ten regiments of cavalry, each with a company of dragoons attached. At the urging of Sir Thomas Fairfax, on 1 March they were formed into a separate unit of 1,000 men, commanded by Colonel John Okey, and played an important part at the Battle of Naseby in June.[11]

Supplied with inferior horses and more basic equipment, the dragoon regiments were cheaper to raise and maintain than the expensive regiments of cavalry. When in the 17th century Gustav II Adolf introduced dragoons into the Swedish Army, he provided them with a sword, an axe and a matchlock musket, using them as "labourers on horseback".[12] Many of the European armies henceforth imitated this all-purpose set of weaponry. Dragoons of the late 17th and early 18th centuries retained strong links with infantry in appearance and equipment, differing mainly in the substitution of riding boots for shoes and the adoption of caps instead of broad-brimmed hats to enable muskets to be worn slung.[13]

A non-military use of dragoons was the 1681 Dragonnades, a policy instituted by Louis XIV to intimidate Huguenot families into either leaving France or re-converting to Catholicism by billeting ill-disciplined dragoons in Protestant households. While other categories of infantry and cavalry were also used, the mobility, flexibility and available numbers of the dragoon regiments made them particularly suitable for repressive work of this nature over a wide area.[14]

In the Spanish Army, Pedro de la Puente organized a body of dragoons in Innsbruck in 1635. In 1640, a tercio of a thousand dragoons armed with the arquebus was created in Spain. By the end of the 17th century, the Spanish Army had three tercios of dragoons in Spain, plus three in the Netherlands and three more in Milan. In 1704, the Spanish dragoons were reorganised into regiments by Philip V, as were the rest of the tercios.[citation needed]

Dragoons were at a disadvantage when engaged against true cavalry, and constantly sought to improve their horsemanship, armament and social status. By the Seven Years' War in 1756, their primary role in most European armies had progressed from that of mounted infantry to that of heavy cavalry. They were sometimes described as "medium" cavalry, midway between heavy/armoured and light/unarmoured regiments, though this was a classification that was rarely used at the time.[15] Their original responsibilities for scouting and picket duty had passed to hussars and similar light cavalry corps in the French, Austrian, Prussian, and other armies. In the Imperial Russian Army, due to the availability of Cossack troops, the dragoons were retained in their original role for much longer.

British Army and Continental Army

[edit]An exception to the rule was the British Army, which from 1746 onward gradually redesignated all regiments of "horse" (regular cavalry) as lower paid "dragoons", in an economy measure.[16] Starting in 1756, seven regiments of light dragoons were raised and trained in reconnaissance, skirmishing and other work requiring endurance in accordance with contemporary standards of light cavalry performance. The success of this new class of cavalry was such that another eight dragoon regiments were converted between 1768 and 1783.[17] When this reorganisation was completed in 1788, the cavalry arm consisted of regular dragoons and seven units of dragoon guards. The designation of dragoon guards did not mean that these regiments (the former 2nd to 8th horse) had become household troops, but simply that they had been given a more dignified title to compensate for the loss of pay and prestige.[16]

Towards the end of 1776, George Washington, commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, realized the need for a mounted branch of the American military. In January 1777 four regiments of light dragoons were raised. Short term enlistments were abandoned and the dragoons joined for three years, or "the war". They participated in most of the major engagements of the American War of Independence, including the battles of White Plains, Trenton, Princeton, Brandywine, Germantown, Saratoga, Cowpens, and Monmouth, as well as the Yorktown campaign.

19th century

[edit]

During the Napoleonic Wars, dragoons generally assumed a cavalry role, though remaining a lighter class of mounted troops than the armored cuirassiers. Dragoons rode larger horses than the light cavalry and wielded straight, rather than curved swords.

France

[edit]Emperor Napoleon often formed complete divisions out of his 30 dragoon regiments, while in 1811 six regiments were converted to Chevau-Legers Lanciers; they were often used in battle to break the enemy's main resistance.[18] In northern and eastern Europe they were employed as heavy cavalry, while in the Peninsular War they also fulfilled the role of lighter cavalry, for example in anti-guerrilla operations.[15] In 1809, French dragoons scored notable successes against Spanish armies at the Battle of Ocaña and the Battle of Alba de Tormes.

British Army

[edit]Between 1806 and 1808, the 7th, 10th, 15th and 18th regiments of Light Dragoons of the British Army were re-designated as hussars and when the Napoleonic Wars ended in 1815, some became lancers. The transition from dragoons to hussars was however a slow one, affecting uniforms but not equipment and functions. Even titles often remained ambiguous until 1861, for example, 18th King's Light Dragoons (Hussars).[19]

The seven regiments of Dragoon Guards served as the heavy cavalry arm of the British Army, although unlike continental cuirassiers they carried no armour.[20] Between 1816 and 1861, the other twenty-one cavalry regiments were either disbanded or rebadged as lancers or hussars.[17][a]

Kingdom of Prussia

[edit]The Kingdom of Prussia in the Napoleonic era included 14 Regiments of Dragoons, designated Numbers 1 through 14, in their Order of Battle at the start of the 1806 Campaign against Napoleon's French Army. Prussian cavalry regiments were better known by their "Chef" or "Inhaber", the titular commander responsible for supporting the regiment, while command in the field might fall to a more junior Colonel, Lt. Colonel, or even a Major. As a result, every time there was a change in "Chef" the name of the regiment changed. By 1806, the Prussian Dragoons wore a very tall bicorn hat worn slanted slightly obliquely with a tall, white plume. Their uniforms had changed by 1802 from coats that had been cut like the infantry to short, medium-blue cavalry tunics. Each regiment had differentiating colors for a variety of uniform accessories such as small pompoms at the side of the hat, tunic facings and shoulder flaps on the left shoulder, woolen tassels for the sabre straps, and the horse saddlecloths. Dragoons were issued a long, straight blade with a single edge, the Dragoon Pallasch sword, which featured a brass basket hilt for hand protection. The Pallasch was designed for powerful cutting and thrusting action, making it effective for cavalry charges.

For the period of 1798 to October of 1806, the majority of Prussian Dragoon regiments were similar to Prussian Cuirassier regiments in staffing and organization. Most were made up of 5 squadrons with an 'on paper' war-time regimental strength of 935 men including soldiers, officers, and all the support staff. The minor difference was that Dragoon regiments had 10 more carabiniers (60 in a Dragoon regiment compared to 50 in a Cuirassier regiment) and therefore ten fewer regular troopers (660 Dragoons compared to 670 Cuirassiers). The average regimental staff of most of the regiments was around 37 officers, 65 NCOs, one staff trumpeter and 14 trumpeters, supported by 5 surgeons led by a regimental surgeon, 9 blacksmiths, a regimental quartermaster, a chaplain and a judge, a horse trainer, a saddlemaker, a gunsmith and a gunstock maker, a provost, and 68 servants. The two regiments that were exceptions were the 5th "Bayreuth" (re-designated in March 1806 as the Queen's or "Königin" Dragoons) and the 6th "Auer" Dragoon regiments, which were double-strength with 10 squadrons and retained 2/3rd German heavy horses.

After the disastrous results of the 1806-07 war with France, most of the Prussian army had ceased to exist. For example, the 9th, 10th, 11th, 12th, and 14th Dragoon regiments were totally lost and even the 9th and 14th Dragoon regimental depots had been destroyed. The complete re-organization of the Prussian army in 1808 led to numerous regiments being re-organized and re-designated, mixing surviving Dragoons and Cuirassier veterans with new recruits into a new numeric system and losing the traditional "Chef" naming schema in favor of a mostly geographical designation, with a few exceptions. For example, the old pre-1807 5th "Bayreuth"/"Königin" Dragoons became the 1st "Königin" Dragoon regiment, while the 7th "von Baczko" Dragoons became the 3rd "Lithuanian" Dragoon regiment. The newly designated 5th "Brandenburg" Dragoons were formed from merging the remains of the 5th "von Bailliodz" Cuirassier regiment and its depot with the remains of the old 1st "Konig von Bayern" Dragoon regiment and its depot. This resulted in the reduction of Prussian Dragoon regiments from 14 to 6.[21]

Many of these new Prussian Dragoon regiments fought in the 1813 Wars of Liberation in the Sixth Coalition against Napoleon in central Europe and France into 1814.

German Empire

[edit]The creation of a unified German state in 1871 brought together the dragoon regiments of Prussia, Bavaria, Saxony, Mecklenburg, Oldenburg, Baden, Hesse, and Württemberg in a single numbered sequence, although historic distinctions of insignia and uniform were largely preserved. Two regiments of the Imperial Guard were designated as dragoons.[22]

Austria

[edit]The Austrian (later Austro-Hungarian) Army of the 19th century included six regiments of dragoons in 1836, classed as heavy cavalry for shock action, but in practice used as multi-purpose medium troops.[23] After 1859 all but two Austrian dragoon regiments were converted to cuirassiers or disbanded.[24] From 1868 to 1918 the Austro-Hungarian dragoons numbered 15 regiments.[25]

Spain

[edit]During the 18th century, Spain raised several regiments of dragoons to protect the northern provinces and borders of New Spain, the present-day states of California, Nevada, Colorado, Texas, Kansas, Arizona, Montana, North Dakota, and South Dakota.[26] In mainland Spain, dragoons were reclassified as light cavalry from 1803 but remained among the elite units of the Spanish Colonial Army. A number of dragoon officers played a leading role in initiating the Mexican War of Independence in 1810, including Ignacio Allende, Juan Aldama and Agustin de Iturbide, who briefly served as Emperor of México from 1822 to 1823.

United States

[edit]Prior to the War of 1812, the U.S. organized the Regiment of Light Dragoons. For the war, a second regiment was activated; that regiment was consolidated with the original regiment in 1814. The original regiment was consolidated with the Corps of Artillery in June 1815.[27] The United States Dragoons were organized by an Act of Congress approved on 2 March 1833 after the disbandment of the Battalion of Mounted Rangers. The unit became the "First Regiment of Dragoons" when the Second Dragoons was raised in 1836. In 1861, they were re-designated as the 1st and 2nd Cavalry but did not change their role or equipment, although the traditional orange uniform braiding of the dragoons was replaced by the standard yellow of the Cavalry branch. This marked the official end of dragoons in the U.S. Army in name, although certain modern units trace their origins back to the historic dragoon regiments. In practice, all US cavalry assumed a dragoon-like role, frequently using carbines and pistols, in addition to their swords.

Russian Empire

[edit]Between 1881 and 1907, all Russian cavalry (other than Cossacks and Imperial Guard regiments) were designated as dragoons, reflecting an emphasis on the double ability of dismounted action as well as the new cavalry tactics in their training and a growing acceptance of the impracticality of employing historical cavalry tactics against modern firepower. Upon the reinstatement of Uhlan and Hussar Regiments in 1907 their training pattern, as well as that of the Cuirassiers of the Guard, remained unchanged until the collapse of the Russian Imperial Army.[28]

Japan

[edit]In Japan, during the late 19th and early 20th century, dragoons were deployed in the same way as in other armies, but were dressed as hussars.

20th century

[edit]

In the period before 1914, dragoon regiments still existed in the British, French,[29] German, Russian, Austro-Hungarian,[30] Canadian, Peruvian, Swiss,[31] Norwegian,[32] Swedish,[33] Danish, and Spanish[34] armies. Their uniforms varied greatly, lacking the characteristic features of hussar or lancer regiments. Uniforms bore occasional reminders of their mounted infantry origins: the 28 dragoon regiments of the Imperial German Army wore the infantry Pickelhaube or spiked helmet,[35] while British dragoons wore scarlet tunics for full dress while hussars and all but one of the lancer regiments wore dark blue.[36] In other respects however dragoons had adopted the same tactics, roles and equipment as other branches of the cavalry and the distinction had become simply one of traditional titles. Weaponry had ceased to have a historic connection, with both the French and German dragoon regiments carrying lances when serving as mounted troops during World War I.

The historic German, Russian and Austro-Hungarian dragoon regiments ceased to exist as distinct branches following the overthrow of the respective imperial regimes of these countries during 1917–18. The Spanish dragoons, which dated back to 1640, were reclassified as numbered cavalry regiments in 1931 as part of the army modernization policies of the Second Spanish Republic.[citation needed]

In 1914, at the outbreak of World War I, France maintained 32 regiments of dragoons. Armed with lances, sabres and carbines they were primarily intended to carry out reconnaissance and infantry flanking functions.[37]

The Australian Light Horse were similar to 18th-century dragoon regiments in some respects, being mounted infantry which normally fought on foot, their horses' purpose being transportation. They served during the Second Boer War and World War I. The Australian 4th Light Horse Brigade became famous for the Battle of Beersheba in 1917 where they charged on horseback using rifle bayonets in hand, since neither sabres nor lances were part of their equipment. Later in the Palestine campaign Pattern 1908 cavalry swords were issued and used in the campaign leading to the fall of Damascus.[citation needed]

Probably the last use of real dragoons (infantry on horseback) in combat was made by the Portuguese Army in the war in Angola during the 1960s and 1970s. In 1966, the Portuguese created an experimental horse platoon to operate against the guerrillas in the high grass region of Eastern Angola, in which each soldier was armed with a G3 battle rifle for combat on foot and with a semi-automatic pistol to fire from horseback. The troops on horseback were able to operate in difficult terrain unsuited to motor vehicles and had the advantage of being able to control the area around them, with a clear view over the grass that foot troops did not have. Moreover, these unconventional troops created a psychological impact on an enemy that was not used to facing horse troops, and thus had no training or strategy to deal with them. The experimental horse platoon was so successful that its entire parent battalion was transformed from an armored reconnaissance unit to a three-squadron horse battalion known as the "Dragoons of Angola". One of the typical operations carried out by the Dragoons of Angola, in cooperation with airmobile forces, consisted of the dragoons chasing the guerrillas and pushing them in one direction, with the airmobile troops being launched from helicopter in the enemy rear, trapping the enemy between the two forces.[38]

Dragoner rank

[edit]Until 1918, Dragoner (en: dragoon) was the designation given to the lowest ranks in the dragoon regiments of the Austro-Hungarian and Imperial German armies. The Dragoner rank, together with all other private ranks of the different branch of service, belonged to the so-called Gemeine rank group.

Modern dragoons

[edit]Brazil

[edit]

The guard of honour for the President of Brazil includes the 1st Guard Cavalry Regiment of the Brazilian Army, known as the "Dragões da Independência" (Independence Dragoons). The name was given in 1927 and refers to the fact that a detachment of dragoons escorted the Prince Royal of Portugal and Brazil, Pedro of Braganza, at the time when he declared Brazilian independence from the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves on 7 September 1822.

The Independence Dragoons wear 19th-century dress uniforms similar to those of the earlier Imperial Honor Guard, which are used as the regimental full dress uniform since 1927. The uniform was designed by Debret, in white and red, with plumed bronze helmets. The colors and pattern were influenced by the Austrian dragoons of the period, as the Brazilian Empress consort was also an Austrian archduchess.[39] The color of the plumes varies according to rank. The Independence Dragoons are armed with lances and sabres, the latter only for the officers and the colour guard.[40]

The regiment was established in 1808 by the Prince Regent and future King of Portugal, John VI, with the duty of protecting the Portuguese royal family, which had sought refuge in Brazil during the Napoleonic Wars. However dragoons had existed in Portugal since at least the early 18th century and, in 1719, units of this type of cavalry were sent to Brazil, initially to escort shipments of gold and diamonds and to guard the Viceroy who resided in Rio de Janeiro (1st Cavalry Regiment – Vice-Roy Guard Squadron). Later, they were also sent to the south to serve against the Spanish during frontier clashes. After the proclamation of the Brazilian independence, the title of the regiment was changed to that of the Imperial Honor Guard, with the role of protecting the Imperial Family. The Guard was later disbanded by Emperor Pedro II and would be recreated only later in the republican era.[41]

At the time of the Republic proclamation in 1889, horse No. 6 of the Imperial Honor Guard was ridden by the officer making the declaration of the end of Imperial rule, Second lieutenant Eduardo José Barbosa. This is commemorated by the custom under which the horse having this number is used only by the commander of the modern regiment.

Canada

[edit]

There are three dragoon regiments in the Canadian Army: The Royal Canadian Dragoons and two reserve regiments, the British Columbia Dragoons and the Saskatchewan Dragoons.

The Royal Canadian Dragoons is the senior Armoured regiment in the Canadian Army. The regiment was authorized in 1883 as the Cavalry School Corps, being redesignated as Canadian Dragoons in 1892, adding the Royal designation the next year. The RCD has a history of fighting dismounted, serving in the Second Boer War in South Africa as mounted infantry, fighting as infantry with the 1st Canadian Division in Flanders in 1915–1916 and spending the majority of the regiment's service in the Italian Campaign 1944–1945 fighting dismounted. In 1994 when the regiment deployed to Bosnia as part of the United Nations Protection Force, B Squadron was employed as a mechanized infantry company. The current role of The Royal Canadian Dragoons is to provide Armour Reconnaissance support to 2 Canadian Mechanized Brigade Group (2 CMBG) as well as C Squadron RCD in Gagetown which is a part of 2 CMBG and the RCD Regiment with Leopard 2A4 and 2A6 tanks.[42]

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police were accorded the formal status of a regiment of dragoons in 1921.[43][44] The modern RCMP does not retain any military status however.

Chile

[edit]Founded as the Dragones de la Reina (Queen's Dragoons) in 1758 and later renamed the Dragoons of Chile in 1812, and then becoming the Carabineros de Chile in 1903. The Carabineros are the national police of Chile. The military counterpart, that of the 15th Reinforced Regiment "Dragoons" is now as of 2010 the 4th Armored Brigade "Chorrillos" based in Punta Arenas as the 6th Armored Cavalry Squadron "Dragoons", and form part of the 5th Army Division.

Denmark

[edit]The Royal Danish Army includes amongst its historic regiments the Jutland Dragoon Regiment, which was raised in 1670.

France

[edit]The modern French Army retains three dragoon regiments from the thirty-two in existence at the beginning of World War I: the 2nd, which is a nuclear, biological and chemical protection regiment, the 5th, an experimental Combined arms regiment, and the 13th (Special Reconnaissance).

Lithuania

[edit]Beginning in the 17th century, the mercenary army of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania included dragoon units. In the middle of the 17th century there were 1,660 dragoons in an army totaling 8,000 men. By the 18th century there were four regiments of dragoons.

Lithuanian cavalrymen served in dragoon regiments of both the Russian and Prussian armies, after the Partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Between 1920 and 1924, and again between 1935 and 1940, the Lithuanian Army included the Third Dragoon Iron Wolf Regiment. The dragoons were the equivalent of the present-day Volunteer Forces.

In modern Lithuania the Grand Duke Butigeidis Dragoon Battalion (Lithuanian: didžiojo kunigaikščio Butigeidžio dragūnų batalionas)[45] is designated as dragoons, with a motorized infantry role.

Mexico

[edit]During the times of the Viceroyalty, regiments of dragoons (Dragon de cuera) were created to defend New Spain. They were mostly horsemen from the provinces. During and after the Mexican war of independence, dragons have played an important role in military conflicts within the country such as the Battle of Puebla during the French intervention, until the Mexican Revolution. One of the best-known military marches in Mexico is the Marcha Dragona (dragon march), the only one currently used by cavalry and motorized units during the parade on 16 September to commemorate Independence Day.[46][47]

Norway

[edit]In the Norwegian Army during the early part of the 20th century, dragoons served in part as mounted troops, and in part on skis or bicycles (hjulryttere, meaning "wheel-riders"). Dragoons fought on horses, bicycles and skis against the German invasion in 1940. After World War II the dragoon regiments were reorganized as armoured reconnaissance units. "Dragon" is the rank of a compulsory service private cavalryman while enlisted (regular) cavalrymen have the same rank as infantrymen: "Grenader".

Pakistan

[edit]The Armoured Regiment "34 Lancers" of Pakistan Army Armoured Corps is also known as "Dragoons".

Peru

[edit]

The "Mariscal Domingo Nieto" Cavalry Regiment Escort, named after Field Marshal Domingo Nieto, a former President of Peru, were the traditional Guard of the Government Palace until 5 March 1987 and its disbandment in that year. However, by Ministerial Resolution No 139-2012/DE/EP of 2 February 2012 the restoration of the Cavalry Regiment "Marshal Domingo Nieto" as the official escort of the President of the Republic of Peru was announced. The main mission of the reestablished regiment was to guarantee the security of the President of the Republic and of the Government Palace.

This regiment of dragoons was created in 1904 following the suggestion of a French military mission which undertook the reorganization of the Peruvian Army in 1896. The initial title of the unit was Cavalry Squadron "President's Escort". It was modelled on the French dragoons of the period. The unit was later renamed as the Cavalry Regiment "President's Escort" before receiving its current title in 1949.

The Peruvian Dragoon Guard has throughout its existence worn French-style uniforms of black tunic and red breeches in winter and white coat and red breeches in summer, with red and white plumed bronze helmets with the coat of arms of Peru and golden or red epaulettes depending on rank. They retain their original armament of lances and sabres, until the 1980s rifles were used for dismounted drill.

At 13:00 hours every day, the main esplanade in front of the Government Palace of Perú fronting Lima's Main Square serves as the stage for the changing of the guard, undertaken by members of the Presidential Life Guard Escort Dragoons, mounted or dismounted. While the dismounted changing is held on Mondays and Fridays, the mounted ceremony is held twice a month on a Sunday.

Portugal

[edit]The Portuguese Army still maintains two units which are descended from former regiments of dragoons. These are the 3rd Regiment of Cavalry (the former "Olivença Dragoons") and the 6th Regiment of Cavalry (the former "Chaves Dragoons"). Both regiments are, presently, armoured units. The Portuguese Rapid Reaction Brigade's Armoured Reconnaissance Squadron – a unit from the 3rd Regiment of Cavalry – is known as the "Paratroopers Dragoons".

During the Portuguese Colonial War in the 1960s and the 1970s, the Portuguese Army created an experimental horse platoon, to combat the guerrillas in eastern Angola. This unit was soon augmented, becoming a group of three squadrons, known as the "Angola Dragoons". The Angola Dragoons operated as mounted infantry – like the original dragoons – each soldier being armed with a pistol to fire when on horseback and with an automatic rifle, to use when dismounted. A unit of the same type was being created in Mozambique when the war ended in 1974.

Spain

[edit]The Spanish Army began the training of a dragoon corps in 1635 under the direction of Pedro de la Puente at Innsbruck. In 1640 the first dragoon "tercio" was created, equipped with arquebuses and maces. The number of dragoon tercios was increased to nine by the end of the XVII century: three garrisoned in Spain, another three in the Netherlands and the remainder in Milan.[48]

The tercios were converted into a Regimental system, beginning in 1704. Philip V created several additional dragoon regiments to perform the functions of a police corps in the New World.[49] Notable amongst those units were the leather-clad dragones de cuera.

In 1803, the dragoon regiments were renamed as "caballería ligera" (light cavalry). By 1815, these units had been disbanded.[50]

Spain recreated its dragoons in the late nineteenth century. Three Spanish dragoon regiments were still in existence in 1930.[51]

Sweden

[edit]In the Swedish Army, dragoons comprise the Military Police and Military Police Rangers. They also form the 13th Battalion of the Life Guards, which is a military police unit. The 13th (Dragoons) Battalion have roots that go back as far as 1523, making it one of the world's oldest military units still in service. Today, the only mounted units still retained by the Swedish Army are the two dragoons squadrons of the King's Guards Battalion of the Life Guards. Horses are used for ceremonial purposes only, most often when the dragoons take part in the changing of the guards at The Royal Palace in Stockholm. "Livdragon" is the rank of a private cavalryman.

Switzerland

[edit]Uniquely, mounted dragoons continued to exist as combat units in the Swiss Armed Forces until the early 1970s, when they were converted into Armoured Grenadiers units. The "Dragoner" had to prove he was able to keep a horse at home before entering the cavalry. At the end of basic training they had to buy a horse at a reduced price from the army and to take it home together with equipment, uniform and weapon. In the "yearly repetition course" the dragoons served with their horses, often riding from home to the meeting point.

The abolition of the dragoon units, believed to be the last non-ceremonial horse cavalry in Europe, was a contentious issue in Switzerland. On 5 December 1972 the Swiss National Council approved the measure by 91 votes, against 71 for retention.[52]

United Kingdom

[edit]As of 2021, the British Army contains four regiments designated as dragoons: 1st The Queens Dragoon Guards, Royal Scots Dragoon Guards, the Royal Dragoon Guards, and the Light Dragoons. These perform a variety of reconnaissance and light support activities, including convoy protection, and operate the Jackal, the Coyote Reconnaissance Vehicle and the FV107 Scimitar light tank.[53]

United States

[edit]

The 1st and 2nd Battalion, 48th Infantry were mechanized infantry units assigned to the 3rd Armored Division (3AD) in West Germany during the Cold War. The unit crest of the 48th Infantry designated the unit as Dragoons, purely a traditional designation.

The 1st Dragoons was reformed in the Vietnam War era as the 1st Squadron, 1st U.S. Cavalry. It served in the Iraq War and remains as the oldest cavalry unit, as well as the most decorated one, in the U.S. Army. Today's modern 1–1 Cavalry is a scout/attack unit, equipped with MRAPs, M3A3 Bradley CFVs, and Strykers.[54]

Another modern United States Army unit, informally known as the 2nd Dragoons, is the 2nd Cavalry Regiment. This unit was originally organized as the Second Regiment of Dragoons in 1836 and was renamed the Second Cavalry Regiment in 1861, being redesignated as the 2nd Armored Cavalry Regiment in 1948. The regiment is currently equipped with the Stryker family of wheeled fighting vehicles and was redesignated as the 2nd Stryker Cavalry Regiment in 2006. In 2011 the 2nd Dragoon regiment was redesignated as the 2nd Cavalry Regiment. The 2nd Cavalry Regiment has the distinction of being the longest continuously serving regiment in the United States Army.[55]

The 113th Army Band at Fort Knox is also officially nicknamed as "The Dragoons". This derives from its formation as the Band, First Regiment of Dragoons on 8 July 1840.

Company D, 3rd Light Armored Reconnaissance Battalion of the United States Marine Corps, is nicknamed the "Dragoons". Their combat history includes service in the Iraq War and the War in Afghanistan from 2002 to 2013.[56]

See also

[edit]- Carabinier

- Cuirassier

- Gendarmerie

- Harquebusier

- Hobilar

- Hussar

- Motorized infantry

- Reiter – A type of pistol-armed cavalry

- Ulan

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ The seven Dragoon Guards regiments were the 1st King's Dragoon Guards, 2nd Dragoon Guards (Queen's Bays), 3rd Dragoon Guards, 4th Royal Irish Dragoon Guards, 5th Dragoon Guards, Carabiniers (6th Dragoon Guards) and the 7th Dragoon Guards. In addition, there were 24 cavalry of the line regiments; 1st The Royal Dragoons, the Royal Scots Greys; 3rd The King's Own Hussars; the 4th Queen's Own Hussars; 5th Royal Irish Lancers (disbanded in 1799 and reformed in 1858); the 6th (Inniskilling) Dragoons, the 7th Queen's Own Hussars, the 8th King's Royal Irish Hussars, the 9th Queen's Royal Lancers, the 10th Royal Hussars, the 11th Hussars, the 12th Royal Lancers, the 13th Hussars, the 14th King's Hussars, the 15th The King's Hussars, the 16th The Queen's Lancers, the 17th Lancers, the 18th Royal Hussars, the 19th Royal Hussars, the 20th Hussars, the 21st Lancers, the 22nd Dragoons, the 23rd Light Dragoons, the 24th Regiment of (Light) Dragoons and 25th Dragoons (renumbered as the 22nd Dragoons in 1802).

References

[edit]- ^ a b Carman 1977, p. 48.

- ^ "Dragoon". Oxford English Dictionary.

A kind of carbine or musket.

- ^ "took his name from his weapon, a species of carbine or short musket called the dragon" (Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 471.)

- ^ Espino López 2012, pp. 7–48.

- ^ Bismark 1855, p. 330.

- ^ Bismark 1855, p. 331.

- ^ Bismark 1855, p. 333.

- ^ Nolan, Cpt. L. E. (1860). Cavalry; Its History and Tactics. London: Bosworth & Harrison. p. 65.

- ^ Reid 2001, p. 96.

- ^ "the definition of dragoon". Dictionary.com.

- ^ Ede-Borrett 2009, pp. 206–207.

- ^ Brzezinski 1993, p. 14-16.

- ^ Mollo 1972, p. 23.

- ^ Chartrand 1988, p. 37.

- ^ a b Haythornthwaite 2001, p. 19.

- ^ a b Barthorp 1984, p. 22.

- ^ a b Barthorp 1984, p. 24.

- ^ Rothenberg 1978, p. 141.

- ^ Barthorp 1984, pp. 61 & 64.

- ^ Rowe 2004.

- ^ Nafziger, George F.,The Prussian Army During the Napoleonic Wars (1792-1815). Volume III. The Cavalry & Artillery, West Chester, OH, 1996, p16-17

- ^ Marrion 1975, pp. 7–11.

- ^ Pavlovic 1999, p. 3.

- ^ Pavlovic 1999, p. 26.

- ^ Knotel 1980, p. 26.

- ^ Torres & Láinez 2008, p. ?.

- ^ Heitman 1903, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Novitsky, N. F., ed. (1911–1915). Cavalry/Encyclopaedia Militera, V.11. Moscow – SPb, Sytin Publishing.

- ^ Jouineau 2008, pp. 23–25.

- ^ Lucas 1987, pp. 101–105.

- ^ Koppen 1890, p. 67.

- ^ Koppen 1890, p. 62.

- ^ Koppen 1890, p. 61.

- ^ Koppen 1890, p. 65.

- ^ Herr 2006, pp. 324–343.

- ^ Barthorp 1984, pp. 183–184.

- ^ Mirouze, Laurent (2007). The French Army in the First World War - to battle 1914. Militaria. p. 296. ISBN 978-3-902526-09-0.

- ^ Cann 1997, p. ?.

- ^ "Exército Brasileiro – Braço Forte, Mão Amiga" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 12 March 2009.

- ^ "Presidência da República – GSI" (in Portuguese). office of the president of Brazil. Archived from the original on 21 June 2008. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- ^ CARVALHO, José Murilo de. D. Pedro II: Ser ou não ser. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2007, p. 98

- ^ "A Short History of The Royal Canadian Dragoons". Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ "Royal Canadian Mounted Police". Archived from the original on 18 January 2008. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- ^ "Ottawa Valley Branch of the Heraldry Society of Canada". Archived from the original on 1 August 2001.

- ^ Media, Fresh. "Lietuvos kariuomenė :: Kariuomenės struktūra » Kontaktai » Lietuvos didžiojo kunigaikščio Butigeidžio dragūnų batalionas". kariuomene.kam.lt. Archived from the original on 19 June 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ "Unidades militares que existieron en la Nueva España. | Secretaría de la Defensa Nacional | Gobierno | gob.mx". Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ "Infonor - Diario Digital". Infonor.com.mx. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ "Los dragones: ¿infantería a caballo, o caballería desmontada?". Camino a Rocroi (in European Spanish). 10 July 2012. Archived from the original on 3 December 2018. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- ^ "Dragones de Cuera: Oeste Español | GUERREROS". guerrerosdelahistoria.com (in European Spanish). Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- ^ Gómez, José Manuel Rodríguez. "Uniformidad de los dragones españoles en 1808". www.eborense.es (in European Spanish). Archived from the original on 11 June 2011. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- ^ Knotel, Richard. Uniforms of the World, pp. 408–409. ISBN 0-684-16304-7

- ^ Dragons toujours en selle, Éditions Imprimerie centrale, Neuchâtel (1974)

- ^ MOD. "Dragoon units". MOD. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ "1/1 CAV equipment arrives in Europe". army.mil. 25 September 2014.

- ^ "Regimental Designations and Deployments | 2d Dragoons". History.dragoons.org. Archived from the original on 28 July 2014. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- ^ "1st Marine Division > Units > 3D LAR BN". 1stmardiv.marines.mil. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

General and cited sources

[edit]- Barthorp, Michael (1984). British Cavalry Uniforms Since 1660. Littlehampton Book Services. ISBN 978-0713710434.

- Bismark, Graf Friedrich Wilhelm von (1855). On the Uses and Application of Cavalry in War from the Text of Bismark: With Practical Examples Selected from Ancient and Modern History. Translated by North Ludlow Beamish. London: T. & W. Boone. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- Brzezinski, Richard (1993). The Army of Gustavus Adolphus (2): Cavalry: Pt. 2. Men-at-Arms). Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1855323506.

- Cann, Jonh P (1997). Counterinsurgency in Africa: The Portuguese Way of War, 1961–1974. Praeger. ISBN 978-0313301896.

- Carman, W. Y. (1977). A Dictionary of Military Uniforms. HarperCollins Distribution Services. ISBN 0684151308.

- Chartrand (1988). Louis XIV's Army. Men-at-Arms No. 203. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-0850458503.

- Ede-Borrett, Stephen (2009). "Some Notes on the Raising and Origins of Colonel John Okey's Regiment of Dragoons, March to June, 1645". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 87 (351): 206–213. JSTOR 44231688.

- Espino López, Antonio (2012). "El uso táctico de las armas de fuego en las guerras civiles peruanas (1538–1547)". Historica (in Spanish). XXXVI (2): 7–48. doi:10.18800/historica.201202.001. S2CID 258861207.

- Haythornthwaite, Philip (2001). Napoleonic Cavalry. Napoleonic weapons & warfare. W&N. ISBN 978-0304355082.

- Heitman, Francis B. (1903). Historical register and dictionary of the United States Army. War Department. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- Herr, Ulrich (2006). The German Cavalry from 1871 to 1914. Verlag Militaria. ISBN 978-3902526076.

- Jouineau, Andre (2008). Officers and Soldiers of the French Army 1914. Amber Books Limited. ISBN 978-2352501046.

- Kannik, Prebben (1968). Military Uniforms in Colour. Blandford Press. ISBN 0713704829.

- Knotel, Richard (1980). Uniforms of the World: A Compendium of Army, Navy and Air Force Uniforms, 1700–1937. Arms & Armour Press. ISBN 978-0853683131.

- Koppen, Fedor von (1890). The Armies of Europe (2015 ed.). Naval & Military Press. ISBN 978-1783311750.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Lucas, James (1987). Fighting Troops of the Austro-Hungarian Army 1868–1914. Spellmount Publishers Ltd. ISBN 0946771049.

- Marrion, Richard (1975). Uniforms of the Imperial German Army, 1900–14: Lancers and Dragoons v. 3. Almark Publishing Co Ltd. ISBN 978-0855242015.

- Mollo, John (1972). Military Fashion: Comparative History of the Uniforms of the Great Armies from the 17th Century to the First World War. Barrie & Jenkins. ISBN 978-0214653490.

- Pavlovic, Darko (1999). The Austrian Army 1836–66 (2) Cavalry. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1855328006.

- Reid, Howard (2001). Arthur the Dragon King: Man and myth reassessed. Headline Book Publishing. ISBN 978-0747275572.

- Rothenberg, Gunther Erich (1978). The Art of Warfare in the Age of Napoleon. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253310768. LCCN 77086495. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- Rowe, David (2004). Head dress of the British heavy cavalry: Dragoon Guards, Household and Yeomanry Cavalry. Schiffer Publishing. ISBN 978-0764309571.

- Torres, Carlos Canales; Láinez, Fernando Martínez (2008). Banderas lejanas: la exploración, conquista y defensa por España del territorio de los actuales Estados Unidos (in Spanish). Edaf. ISBN 978-8441421196.

- Young, Peter; Holmes, Richard (2000). The English Civil War: A Military History of the Three Civil Wars, 1642–1651. Ware, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions. ISBN 1840222220.

Further reading

[edit]- Bennett, James A, Edited by Brooks, Clinton E., Reeve, Frank D. (1948). Forts and Forays, James A. Bennett: A Dragoon in New Mexico 1850–1856. The University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.

- Hildreth, James (1836). Dragoon Campaigns to the Rocky Mountains, Being a History of the Enlistment, Organization, and first Campaigns of The Regiment Of United States Dragoons. New York: Wiley & Long, No. D. Fanshaw, Printer.

- Note 1: Possibly from a previous writing, which resulted in a court martial, in which he was acquitted (p. 8), the author wished to remain anonymous and sometimes listed his name as "By A Dragoon" in lieu of his real name.

- Note 2: At the time of the author's enlistment in 1833, only one regiment of U.S. Dragoons existed, therefore there was no need to designate it with a number. When two more mounted regiments were created by Congress in 1836, the Regiment of Dragoons became the 1st U.S. Dragoons.

- Sawicki, James A. (1985). Cavalry Regiments in the U.S. Army. Dumfries, Virginia: Wyvern Publications. p. 415. ISBN 0-9602404-6-2. LCCN 85050072.

External links

[edit]- Napoleonic Cavalry: Dragoons, Cuirassiers

- Saskatchewan Dragoons (Canada)

- British Columbia Dragoons (Canada)

- First Regiment of Cavalry (USA) Archived 12 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- The Society of the Military Horse

- "Field Marshal Nieto" Regiment of Cavalry (Perú) Archived 10 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- Perú 1970: Changing of the Dragoon Guard

- Prussian Dragoon Regiments in 1806 War with France, Battle of Jena/Auerstadt

Dragoon

View on GrokipediaEtymology and Definition

Origins of the Term

The term "dragoon" originates from the French word dragon, denoting a short musket or carbine with a bell-mouthed barrel that evoked the image of a mythical fire-breathing dragon through its flared design and the expulsion of smoke and flame upon discharge.[3] This firearm, a handheld variant of the blunderbuss, was the signature weapon of the soldiers who bore the name, distinguishing them from other mounted troops reliant on edged weapons or longer firearms ill-suited for dismounted action.[7] The linguistic link underscores the emphasis on firepower in their early tactical identity, rather than any heraldic or serpentine emblem. The military application of "dragoon" first emerged in France during the 1630s, amid the escalating conflicts of the Thirty Years' War, when King Louis XIII authorized the formation of specialized mounted units equipped with these dragons.[8] One of the earliest documented examples is a regiment raised in 1630 in Piedmont under Commander Souvré, which was formally admitted to French service on May 16, 1635, marking the institutionalization of dragoons as a distinct branch.[8] These units represented an evolution from ad hoc mounted musketeers, providing infantry-like firepower with equine speed for reinforcement or skirmishing. Conceptually, dragoons differed from pure cavalry by prioritizing hybrid utility over charging prowess; they advanced rapidly on horseback to battlefields but dismounted to engage as infantry, avoiding the vulnerabilities of armored horsemen in prolonged foot combat.[4] This role suited them for raiding, securing flanks, or exploiting terrain where traditional cavalry faltered, reflecting a pragmatic adaptation to the era's shift toward combined arms tactics without aspiring to the status of elite shock troops.[4]Core Characteristics and Distinctions

Dragoons represented a pragmatic military adaptation in early modern warfare, functioning primarily as mounted infantry who relied on horses for swift battlefield mobility but dismounted to deliver fire support using short-barreled carbines or muskets. This core operational doctrine set them apart from charge-oriented cavalry branches, such as lancers employing polearms for shock tactics or hussars specializing in rapid mounted pursuits, thereby prioritizing firepower over melee impact in fluid engagements.[4][6][2] The inherent advantages of this hybrid approach lay in enhanced reconnaissance, skirmishing capabilities, and the ability to secure vulnerable flanks or strategic chokepoints, where dragoons could outpace foot infantry while maintaining disciplined volley fire. Battlefield records from 17th-century campaigns illustrate their tactical flexibility, as units often held elevated positions or fords against superior numbers by leveraging mobility for positioning and dismounted volleys for sustained defense, outperforming static infantry in scenarios demanding rapid redeployment.[9][1] Over time, dragoons transitioned from loosely organized raiding detachments to structured regiments, with training regimens that fused infantry foot drills—emphasizing formation firing and bayonet work—with essential horsemanship for endurance riding and horse management under fire. This comprehensive preparation, more demanding than that of pure infantry or cavalry, cultivated soldiers capable of seamless shifts between mounted approach and dismounted combat, underscoring their role as a versatile force multiplier in resource-constrained armies.[10][5]Historical Origins and Early Role

17th-Century Formation

Dragoon units emerged in the early 17th century as mounted infantry within the Swedish army under King Gustavus Adolphus, with initial formations dating to around 1611, where they functioned primarily as fire-support elements for cavalry, dismounting to engage with muskets while leveraging horses for rapid repositioning.[11] These early Swedish prototypes emphasized tactical flexibility during campaigns preceding and including the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), allowing smaller forces to harass enemies and secure flanks without the full logistical demands of shock cavalry. In parallel, the French army formalized dragoon regiments in 1635 under Cardinal Richelieu's direction as France escalated involvement in the same conflict against Habsburg and Spanish forces, deploying units such as those associated with the Cardinal-Duc for targeted raids and disruption of supply lines.[1] The rapid adoption of dragoons across European powers stemmed from inherent economic efficiencies amid the protracted fiscal strains of 17th-century warfare, as these troops required cheaper, lighter horses suited for transport rather than charging, along with simplified equipment focused on firearms over heavy armor or lances, thereby delivering infantry volley fire with superior mobility at a fraction of the cost of cuirassier or reiter regiments.[2] This hybrid model addressed causal pressures from prolonged conflicts like the Thirty Years' War, where states faced ballooning armies—Sweden fielding up to 45,000 troops by 1632 and France mobilizing over 100,000 by 1635—yet grappled with limited revenues, making dragoons a pragmatic solution for amplifying combat output without proportional expense increases. In practice, dragoons demonstrated their value through specialized roles in sieges and pursuits during the Thirty Years' War, where they dismounted to deliver suppressive fire during assaults on fortified positions or to cover retreating infantry, while their equine speed enabled effective chasing of routed foes who lacked comparable transport.[12] Such applications underscored the units' utility in asymmetric engagements, combining the endurance of foot soldiers with the velocity to exploit breakthroughs or evade counterattacks, influencing their integration into armies from the Holy Roman Empire to England by mid-century.Initial Tactics as Mounted Infantry

Dragoons in the early 17th century operated primarily as mounted infantry, advancing rapidly on horseback to favorable positions before dismounting in company formations led by drummers to deliver coordinated musket volleys against enemy lines.[4] This tactic exploited their mobility for surprise engagements, particularly effective against disorganized or isolated infantry units in rough or enclosed terrain where heavy cavalry charges faltered, followed by swift remounting for pursuit or evasion.[1] Horses served as expendable transport rather than combat assets, enabling dragoons to function as a flexible force for skirmishing and securing key points like bridges or hedgerows.[13] Training regimens prioritized marksmanship with short-barreled carbines or "dragon" muskets over saber or melee skills, reflecting their infantry-oriented doctrine where dismounted firepower determined outcomes.[2] Recruits drilled in rapid dismounting, volley fire, and reformation, with secondary emphasis on basic sword use for close defense, as Gustavus Adolphus equipped Swedish dragoons with matchlock muskets, swords, and axes for versatile but foot-based combat starting around 1621.[13] This approach treated mounts as logistical tools, often inferior in quality to cavalry horses, underscoring dragoons' role in supporting broader infantry actions through speed and firepower projection.[4] Despite vulnerabilities—such as slower reloading when dismounted compared to unencumbered foot soldiers and exposure of tethered horses to counterattacks—dragoons proved effective in asymmetric warfare by disrupting enemy cohesion and logistics.[1] At the Battle of Naseby on June 14, 1645, Colonel John Okey's Parliamentarian dragoons dismounted to shield flanks against Royalist assaults, then pursued retreating forces, breaking their morale and preventing reorganization to secure a decisive victory.[1] Similarly, during the Thirty Years' War, Swedish dragoons under Gustavus Adolphus at Lützen in November 1632 used mounted approach and dismounted fire to outmaneuver Habsburg tercios, demonstrating causal impacts on enemy command through targeted harassment that pure infantry lacked the mobility to achieve.[1] These outcomes refuted claims of inherent inferiority, as dragoons' hybrid capabilities inflicted disproportionate psychological and operational damage relative to their numbers.[4]Tactical Evolution and Equipment

Transition from Dismounted to Mounted Combat

During the late 17th and early 18th centuries, dragoons shifted doctrinally from primarily dismounted infantry roles to incorporating mounted shock tactics, driven by the need to counter the dominance of heavy cavalry in European linear warfare. This evolution emphasized training in sword and pistol use for charges, enabling dragoons to deliver decisive impacts against enemy lines after initial firepower exchanges, as pure cavalry units increasingly prioritized melee over firearms.[14][15] In John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough's campaigns during the War of the Spanish Succession, this hybrid approach proved tactically superior, with dragoons executing mounted charges that exploited breakthroughs. At the Battle of Blenheim on August 13, 1704, dragoon units supported infantry assaults by charging disarrayed French forces, contributing to the rout of 35,000 enemy troops against Allied losses of about 13,000. Similarly, at Ramillies on May 23, 1706, British dragoons, including the Scots Greys, overran French regiments in a mounted assault, capturing standards and prisoners while sustaining fewer casualties relative to the 20,000 French killed or wounded versus 2,500 Allied. Battlefield outcomes demonstrated higher effectiveness in hybrid actions, with dragoons achieving localized kill ratios favoring mounted follow-ups over static dismounted fire, as mobility allowed rapid concentration against vulnerable flanks.[16][17] Technological refinements, including lighter carbines that balanced reload times with horse handling and enhanced stirrup designs for stability during maneuvers, facilitated this doctrinal pivot by reducing the disadvantages of firing or charging from horseback. These changes addressed empirical limitations of early dragoons, where dismounted tactics yielded lower decisive impacts against entrenched foes, as evidenced by slower pursuit rates in pre-1700 engagements compared to Marlborough-era pursuits covering up to 20 miles post-victory. While the shift granted greater shock power for breaking infantry squares or cavalry reserves, it compromised some entrenchment capabilities in defensive scenarios, potentially exposing units to artillery in open fields; however, linear warfare metrics—such as Marlborough's 80% success rate in major battles utilizing dragoon versatility—refuted claims of training "divided loyalties," affirming the net tactical gains in fluid, maneuver-oriented conflicts.[18][19][20]Armament: Firearms, Edged Weapons, and Uniforms

Early dragoons, originating in France around 1667, were equipped with a short smoothbore musket known as the dragon or carbine, typically 30 to 36 inches in barrel length, alongside two flintlock pistols and a single-edged, slightly curved saber featuring a sharpened forte and copper-wired hilt.[21] [22] The carbine's compact design prioritized maneuverability for dismounted fire but yielded inferior range and accuracy compared to line infantry muskets, with effective hits on man-sized targets probable at 50 yards but falling to low probabilities beyond 75 yards in period smoothbore tests.[23] [24] Uniforms emphasized functionality for both riding and dismounting, retaining infantry-style coats—blue for French dragoons and red with regimental facings for British—paired with high leather boots, breeches, and minimal accoutrements to avoid hindering foot action.[25] [26] Edged weapons like the saber provided close-quarters efficacy post-volley, with the blade's curve aiding slashing from horseback or thrusting when grounded. By the early 18th century, flintlock mechanisms standardized across carbines such as the British Pattern 1756 light dragoon model, often adapted with socket bayonets for versatility in defensive stands or charges after firing.[27] [28] These additions mitigated the carbine's post-shot vulnerability, though shorter barrels still limited standoff power versus full-length muskets; mobility thus causally offset precision deficits, enabling surprise engagements at closer ranges where hit rates remained viable.[29] Lighter overall gear, including simplified sword designs and reduced pistol counts in some regiments, enhanced speed without sacrificing core dismounted firepower.[30]