Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

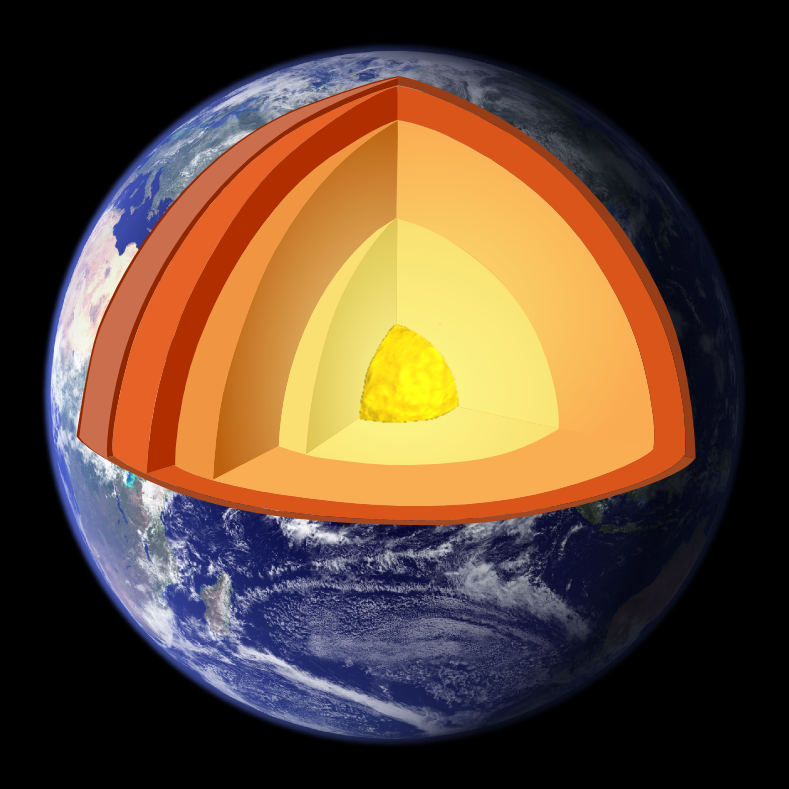

Internal structure of Earth

View on Wikipedia| Part of a series of |

| Geophysics |

|---|

|

The internal structure of Earth is the layers of the planet Earth, excluding its atmosphere and hydrosphere. The structure consists of an outer silicate solid crust, a highly viscous asthenosphere, and solid mantle, a liquid outer core whose flow generates the Earth's magnetic field, and a solid inner core.

Scientific understanding of the internal structure of Earth is based on observations of topography and bathymetry, observations of rock in outcrop, samples brought to the surface from greater depths by volcanoes or volcanic activity, analysis of the seismic waves that pass through Earth, measurements of the gravitational and magnetic fields of Earth, and experiments with crystalline solids at pressures and temperatures characteristic of Earth's deep interior.

Global properties

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2022) |

| Chemical element/oxide | Chondrite model (1) (%) | Chondrite model (2) (%) |

|---|---|---|

| MgO | 26.3 | 38.1 |

| Al2O3 | 2.7 | 3.9 |

| SiO2 | 29.8 | 43.2 |

| CaO | 2.6 | 3.9 |

| FeO | 6.4 | 9.3 |

| Other oxides | N/A | 5.5 |

| Fe | 25.8 | N/A |

| Ni | 1.7 | N/A |

| Si | 3.5 | N/A |

Note: In chondrite model (1), the light element in the core is assumed to be Si. Chondrite model (2) is a model of chemical composition of the mantle corresponding to the model of core shown in chondrite model (1).[1]

Measurements of the force exerted by Earth's gravity can be used to calculate its mass. Astronomers can also calculate Earth's mass by observing the motion of orbiting satellites. Earth's average density can be determined through gravimetric experiments, which have historically involved pendulums. The mass of Earth is about 6×1024 kg.[4] The average density of Earth is 5.515 g/cm3.[5]

Layers

[edit]

- upper mantle

- lower mantle

- Mohorovičić discontinuity

- core–mantle boundary

- outer core–inner core boundary

The structure of Earth can be defined in two ways: by mechanical properties such as rheology, or chemically. Mechanically, it can be divided into lithosphere, asthenosphere, mesospheric mantle, outer core, and the inner core. Chemically, Earth can be divided into the crust, upper mantle, lower mantle, outer core, and inner core.[6] The geologic component layers of Earth are at increasing depths below the surface.[6]: 146

Crust and lithosphere

[edit]

Earth's crust ranges from 5 to 70 kilometres (3.1–43.5 mi)[7] in depth and is the outermost layer.[8] The thin parts are the oceanic crust, which underlies the ocean basins (5–10 km) and is mafic-rich[9] (dense iron-magnesium silicate mineral or igneous rock).[10] The thicker crust is the continental crust, which is less dense[11] and is felsic-rich (igneous rocks rich in elements that form feldspar and quartz).[12] The rocks of the crust fall into two major categories – sial (aluminium silicate) and sima (magnesium silicate).[13] It is estimated that sima starts about 11 km below the Conrad discontinuity,[14] though the discontinuity is not distinct and can be absent in some continental regions.[15]

Earth's lithosphere consists of the crust and the uppermost mantle.[16] The crust-mantle boundary occurs as two physically different phenomena. The Mohorovičić discontinuity is a distinct change of seismic wave velocity. This is caused by a change in the rock's density[17] – immediately above the Moho, the velocities of primary seismic waves (P wave) are consistent with those through basalt (6.7–7.2 km/s), and below they are similar to those through peridotite or dunite (7.6–8.6 km/s).[18] Second, in oceanic crust, there is a chemical discontinuity between ultramafic cumulates and tectonized harzburgites, which has been observed from deep parts of the oceanic crust that have been obducted onto the continental crust and preserved as ophiolite sequences.[clarification needed]

Many rocks making up Earth's crust formed less than 100 million years ago; however, the oldest known mineral grains are about 4.4 billion years old, indicating that Earth has had a solid crust for at least 4.4 billion years.[19]

Mantle

[edit]

Earth's mantle extends to a depth of 2,890 km (1,800 mi), making it the planet's thickest layer.[21] [This is 45% of the 6,371 km (3,959 mi) radius, and 83.7% of the volume - 0.6% of the volume is the crust]. The mantle is divided into upper and lower mantle[22] separated by a transition zone.[23] The lowest part of the mantle next to the core-mantle boundary is known as the D″ (D-double-prime) layer.[24] The pressure at the bottom of the mantle is ≈140 GPa (1.4 Matm).[25] The mantle is composed of silicate rocks richer in iron and magnesium than the overlying crust.[26] Although solid, the mantle's extremely hot silicate material can flow over very long timescales.[27] Convection of the mantle propels the motion of the tectonic plates in the crust. The source of heat that drives this motion is the decay of radioactive isotopes in Earth's crust and mantle combined with the initial heat from the planet's formation[28] (from the potential energy released by collapsing a large amount of matter into a gravity well, and the kinetic energy of accreted matter).

Due to increasing pressure deeper in the mantle, the lower part flows less easily, though chemical changes within the mantle may also be important. The viscosity of the mantle ranges between 1021 and 1024 pascal-second, increasing with depth.[29] In comparison, the viscosity of water at 300 K (27 °C; 80 °F) is 0.89 millipascal-second [30] and pitch is (2.3 ± 0.5) × 108 pascal-second.[31]

Earth's outer core is a fluid layer about 2,260 km (1,400 mi) in height (i.e. distance from the highest point to the lowest point at the edge of the inner core) [36% of the Earth's radius, 15.6% of the volume] and composed of mostly iron and nickel that lies above Earth's solid inner core and below its mantle.[33] Its outer boundary lies 2,890 km (1,800 mi) beneath Earth's surface. The transition between the inner core and outer core is located approximately 5,150 km (3,200 mi) beneath Earth's surface. Earth's inner core is the innermost geologic layer of the planet Earth. It is primarily a solid ball with a radius of about 1,220 km (760 mi), which is about 19% of Earth's radius [0.7% of volume] or 70% of the Moon's radius.[34][35]

The inner core was discovered in 1936 by Inge Lehmann and is composed primarily of iron and some nickel. Since this layer is able to transmit shear waves (transverse seismic waves), it must be solid. Experimental evidence has at times been inconsistent with current crystal models of the core.[36] Other experimental studies show a discrepancy under high pressure: diamond anvil (static) studies at core pressures yield melting temperatures that are approximately 2000 K below those from shock laser (dynamic) studies.[37][38] The laser studies create plasma,[39] and the results are suggestive that constraining inner core conditions will depend on whether the inner core is a solid or is a plasma with the density of a solid. This is an area of active research.

In early stages of Earth's formation about 4.6 billion years ago, melting would have caused denser substances to sink toward the center in a process called planetary differentiation (see also the iron catastrophe), while less-dense materials would have migrated to the crust. The core is thus believed to largely be composed of iron (80%), along with nickel and one or more light elements, whereas other dense elements, such as lead and uranium, either are too rare to be significant or tend to bind to lighter elements and thus remain in the crust (see felsic materials). Some have argued that the inner core may be in the form of a single iron crystal.[40][41]

Under laboratory conditions a sample of iron–nickel alloy was subjected to the core-like pressure by gripping it in a vise between 2 diamond tips (diamond anvil cell), and then heating to approximately 4000 K. The sample was observed with x-rays, and strongly supported the theory that Earth's inner core was made of giant crystals running north to south.[42][43]

The composition of Earth bears strong similarities to that of certain chondrite meteorites, and even to some elements in the outer portion of the Sun.[44][45] Beginning as early as 1940, scientists, including Francis Birch, built geophysics upon the premise that Earth is like ordinary chondrites, the most common type of meteorite observed impacting Earth. This ignores the less abundant enstatite chondrites, which formed under extremely limited available oxygen, leading to certain normally oxyphile elements existing either partially or wholly in the alloy portion that corresponds to the core of Earth.[citation needed]

Dynamo theory suggests that convection in the outer core, combined with the Coriolis effect, gives rise to Earth's magnetic field. The solid inner core is too hot to hold a permanent magnetic field (see Curie temperature) but probably acts to stabilize the magnetic field generated by the liquid outer core. The average magnetic field in Earth's outer core is estimated to measure 2.5 milliteslas (25 gauss), 50 times stronger than the magnetic field at the surface.[46]

The magnetic field generated by core flow is essential to protect life from interplanetary radiation and prevent the atmosphere from dissipating in the solar wind. The rate of cooling by conduction and convection is uncertain,[47] but one estimate is that the core would not be expected to freeze up for approximately 91 billion years, which is well after the Sun is expected to expand, sterilize the surface of the planet, and then burn out.[48][better source needed]

Seismology

[edit]The layering of Earth has been inferred indirectly using the time of travel of refracted and reflected seismic waves created by earthquakes. The core does not allow shear waves to pass through it, while the speed of travel (seismic velocity) is different in other layers. The changes in seismic velocity between different layers causes refraction owing to Snell's law, like light bending as it passes through a prism. Likewise, reflections are caused by a large increase in seismic velocity and are similar to light reflecting from a mirror.

See also

[edit]- Hollow Earth

- Geological history of Earth

- Large low-shear-velocity provinces

- Lehmann discontinuity

- Rain-out model

- Seismic tomography – technique for imaging the subsurface of Earth using seismic waves

- Travel to the Earth's center

- Solid earth

References

[edit]- ^ a b The Structure of Earth and Its Constituents (PDF). Princeton University Press. p. 4.

- ^ Petsko, Gregory A. (28 April 2011). "The blue marble". Genome Biology. 12 (4): 112. doi:10.1186/gb-2011-12-4-112. PMC 3218853. PMID 21554751.

- ^ "Apollo Imagery – AS17-148-22727". NASA. 1 November 2012. Archived from the original on 20 April 2019. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ ME = 5·9722×1024 kg ± 6×1020 kg. "2016 Selected Astronomical Constants Archived 2016-02-15 at the Wayback Machine" in The Astronomical Almanac Online (PDF), USNO–UKHO, archived from the original on 2016-12-24, retrieved 2016-02-18

- ^ "Planetary Fact Sheet". Lunar and Planetary Science. NASA. Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- ^ a b Montagner, Jean-Paul (2011). "Earth's structure, global". In Gupta, Harsh (ed.). Encyclopedia of solid earth geophysics. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9789048187010.

- ^ Andrei, Mihai (21 August 2018). "What are the layers of the Earth?". ZME Science. Archived from the original on 12 May 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ Chinn, Lisa (25 April 2017). "Earth's Structure From the Crust to the Inner Core". Sciencing. Leaf Group Media. Archived from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ Rogers, N., ed. (2008). An Introduction to Our Dynamic Planet. Cambridge University Press and The Open University. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-521-49424-3. Archived from the original on 2016-05-02. Retrieved 2022-08-08.

- ^ Jackson, Julia A., ed. (1997). "mafic". Glossary of Geology (4th ed.). Alexandria, Virginia: American Geological Institute. ISBN 0922152349.

- ^ "Continental crust". Encyclopædia Britannica. 5 September 2023. Retrieved 6 October 2024.

- ^ Schmidt, Victor A.; Harbert, William (1998). "The Living Machine: Plate Tectonics". Planet Earth and the New Geosciences (3rd ed.). Kendall/Hunt. p. 442. ISBN 978-0-7872-4296-1. Archived from the original on 2010-01-24. Retrieved 2008-01-28. Schmidt, Victor A.; Harbert, William. "Unit 3: The Living Machine: Plate Tectonics". Planet Earth and the New Geosciences. Poznańb: Adam Mickiewicz University. Archived from the original on 2010-03-28.

- ^ Hess, H. (1955-01-01). "The oceanic crust". Journal of Marine Research. 14 (4): 424.

It has been common practice to subdivide the crust into sial and sima. These terms refer to generalized compositions, sial being those rocks rich in Si and Al and sima those rich in Si and Mg.

- ^ Kearey, P.; Klepeis, K. A.; Vine, F. J. (2009). Global Tectonics (3 ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 19–21. ISBN 9781405107778. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ^ Lowrie, W. (1997). Fundamentals of Geophysics. Cambridge University Press. p. 149. ISBN 9780521467285. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ^ Himiyama, Yukio; Satake, Kenji; Oki, Taikan, eds. (2020). Human Geoscience. Singapore: Springer Science+Business Media. p. 27. ISBN 978-981-329-224-6. OCLC 1121043185.

- ^ Rudnick, R. L.; Gao, S. (2003-01-01), Holland, Heinrich D.; Turekian, Karl K. (eds.), "3.01 – Composition of the Continental Crust", Treatise on Geochemistry, 3, Pergamon: 659, Bibcode:2003TrGeo...3....1R, doi:10.1016/b0-08-043751-6/03016-4, ISBN 978-0-08-043751-4, retrieved 2019-11-21

- ^ Cathcart, R. B. & Ćirković, M. M. (2006). Badescu, Viorel; Cathcart, Richard Brook & Schuiling, Roelof D. (eds.). Macro-engineering: a challenge for the future. Springer. p. 169. ISBN 978-1-4020-3739-9.

- ^ "Oldest rock shows Earth was a hospitable young planet". Spaceflight Now. National Science Foundation. 2001-01-14. Archived from the original on 2009-06-28. Retrieved 2012-01-27.

- ^ "MANTO", Silvae, Harvard University Press, pp. 2–29, 2004-07-30, retrieved 2025-10-09

- ^ Nace, Trevor (16 January 2016). "Layers Of The Earth: What Lies Beneath Earth's Crust". Forbes. Archived from the original on 5 March 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ Evers, Jeannie (11 August 2015). "Mantle". National Geographic. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 12 May 2016. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ Yu, Chunquan; Day, Elizabeth A.; de Hoop, Maarten V.; Campillo, Michel; Goes, Saskia; Blythe, Rachel A.; van der Hilst, Robert D. (28 March 2018). "Compositional heterogeneity near the base of the mantle transition zone beneath Hawaii". Nat Commun. 9 (9): 1266. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9.1266Y. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-03654-6. PMC 5872023. PMID 29593266.

- ^ Krieger, Kim (24 March 2004). "D Layer Demystified". Science News. American Association for the Advancement of Science. Archived from the original on 10 July 2022. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- ^ Dolbier, Rachel. "Coring the Earth" (PDF). W. M. Keck Earth Science and Mineral Engineering Museum. University of Nevada, Reno: 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ Cain, Fraser (26 March 2016). "What is the Earth's Mantle Made Of?". Universe Today. Archived from the original on 6 November 2010. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ Shaw, Ethan (22 October 2018). "The Different Properties of the Asthenosphere & the Lithosphere". Sciencing. Leaf Group Media. Archived from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ Preuss, Paul (July 17, 2011). "What Keeps the Earth Cooking?". Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. University of California, Berkeley. Archived from the original on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ Walzer, Uwe; Hendel, Roland; Baumgardner, John. "Mantle Viscosity and the Thickness of the Convective Downwellings". Los Alamos National Laboratory. Universität Heidelberg. Archived from the original on 26 August 2006. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ Haynes, William M.; David R., Lide; Bruno, Thomas J., eds. (2017). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (97th ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. Section 6 page 247. ISBN 978-1-4987-5429-3. OCLC 957751024.

- ^ Edgeworth, R.; Dalton, B.J.; Parnell, T. "The Pitch Drop Experiment". The University of Queensland Australia. Archived from the original on 28 March 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

- ^ "MANTO", Silvae, Harvard University Press, pp. 2–29, 2004-07-30, retrieved 2025-10-09

- ^ "Earth's Interior". Science & Innovation. National Geographic. 18 January 2017. Archived from the original on 18 January 2019. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ Monnereau, Marc; Calvet, Marie; Margerin, Ludovic; Souriau, Annie (21 May 2010). "Lopsided growth of Earth's inner core". Science. 328 (5981): 1014–1017. Bibcode:2010Sci...328.1014M. doi:10.1126/science.1186212. PMID 20395477. S2CID 10557604.

- ^ Engdahl, E.R.; Flinn, E.A.; Massé, R.P. (1974). "Differential PKiKP travel times and the radius of the inner core". Geophysical Journal International. 39 (3): 457–463. Bibcode:1974GeoJ...39..457E. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246x.1974.tb05467.x.

- ^ Stixrude, Lars; Cohen, R.E. (January 15, 1995). "Constraints on the crystalline structure of the inner core: Mechanical instability of BCC iron at high pressure". Geophysical Research Letters. 22 (2): 125–28. Bibcode:1995GeoRL..22..125S. doi:10.1029/94GL02742. Archived from the original on August 8, 2022. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- ^ Benuzzi-Mounaix, A.; Koenig, M.; Ravasio, A.; Vinci, T. (2006). "Laser-driven shock waves for the study of extreme matter states". Plasma Physics and Controlled Fusion. 48 (12B): B347. Bibcode:2006PPCF...48B.347B. doi:10.1088/0741-3335/48/12B/S32. S2CID 121164044.

- ^ Remington, Bruce A.; Drake, R. Paul; Ryutov, Dmitri D. (2006). "Experimental astrophysics with high power lasers and Z pinches". Reviews of Modern Physics. 78 (3): 755. Bibcode:2006RvMP...78..755R. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.78.755. Archived from the original on 2020-05-23. Retrieved 2019-06-26.

- ^ Benuzzi-Mounaix, A.; Koenig, M.; Husar, G.; Faral, B. (June 2002). "Absolute equation of state measurements of iron using laser driven shocks". Physics of Plasmas. 9 (6): 2466. Bibcode:2002PhPl....9.2466B. doi:10.1063/1.1478557.

- ^ Schneider, Michael (1996). "Crystal at the Center of the Earth". Projects in Scientific Computing, 1996. Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center. Archived from the original on 5 February 2007. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ Stixrude, L.; Cohen, R.E. (1995). "High-Pressure Elasticity of Iron and Anisotropy of Earth's Inner Core". Science. 267 (5206): 1972–75. Bibcode:1995Sci...267.1972S. doi:10.1126/science.267.5206.1972. PMID 17770110. S2CID 39711239.

- ^ BBC News, "What is at the centre of the Earth? Archived 2020-05-23 at the Wayback Machine. BBC.co.uk (2011-08-31). Retrieved on 2012-01-27.

- ^ Ozawa, H.; al., et (2011). "Phase Transition of FeO and Stratification in Earth's Outer Core". Science. 334 (6057): 792–94. Bibcode:2011Sci...334..792O. doi:10.1126/science.1208265. PMID 22076374. S2CID 1785237.

- ^ Herndon, J.M. (1980). "The chemical composition of the interior shells of the Earth". Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A372 (1748): 149–54. Bibcode:1980RSPSA.372..149H. doi:10.1098/rspa.1980.0106. JSTOR 2398362. S2CID 97600604.

- ^ Herndon, J.M. (2005). "Scientific basis of knowledge on Earth's composition" (PDF). Current Science. 88 (7): 1034–37. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-07-30. Retrieved 2012-01-27.

- ^ Buffett, Bruce A. (2010). "Tidal dissipation and the strength of the Earth's internal magnetic field". Nature. 468 (7326): 952–94. Bibcode:2010Natur.468..952B. doi:10.1038/nature09643. PMID 21164483. S2CID 4431270.

- ^ David K. Li (19 January 2022). "Earth's core cooling faster than previously thought, researchers say". NBC News.

- ^ "Core". National Geographic. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Drollette, Daniel (October 1996). "A Spinning Crystal Ball". Scientific American. 275 (4): 28–33. Bibcode:1996SciAm.275d..28D. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1096-28.

- Kruglinski, Susan (June 2007). "Journey to the Center of the Earth". Discover. Archived from the original on 26 May 2016. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- Lehmann, I (1936). "Inner Earth". Bur. Cent. Seismol. Int. 14: 3–31.

- Wegener, Alfred (1966). The origin of continents and oceans. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-61708-4.

External links

[edit] Media related to Structure of the Earth at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Structure of the Earth at Wikimedia Commons