Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Economic model

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Economics |

|---|

|

|

|

An economic model is a theoretical construct representing economic processes by a set of variables and a set of logical and/or quantitative relationships between them. The economic model is a simplified, often mathematical, framework designed to illustrate complex processes. Frequently, economic models posit structural parameters.[1] A model may have various exogenous variables, and those variables may change to create various responses by economic variables. Methodological uses of models include investigation, theorizing, and fitting theories to the world.[2]

Overview

[edit]In general terms, economic models have two functions: first as a simplification of and abstraction from observed data, and second as a means of selection of data based on a paradigm of econometric study.

Simplification is particularly important for economics given the enormous complexity of economic processes.[3] This complexity can be attributed to the diversity of factors that determine economic activity; these factors include: individual and cooperative decision processes, resource limitations, environmental and geographical constraints, institutional and legal requirements and purely random fluctuations. Economists therefore must make a reasoned choice of which variables and which relationships between these variables are relevant and which ways of analyzing and presenting this information are useful.

Selection is important because the nature of an economic model will often determine what facts will be looked at and how they will be compiled. For example, inflation is a general economic concept, but to measure inflation requires a model of behavior, so that an economist can differentiate between changes in relative prices and changes in price that are to be attributed to inflation.

In addition to their professional academic interest, uses of models include:

- Forecasting economic activity in a way in which conclusions are logically related to assumptions;

- Proposing economic policy to modify future economic activity;

- Presenting reasoned arguments to politically justify economic policy at the national level, to explain and influence company strategy at the level of the firm, or to provide intelligent advice for household economic decisions at the level of households.

- Planning and allocation, in the case of centrally planned economies, and on a smaller scale in logistics and management of businesses.

- In finance, predictive models have been used since the 1980s for trading (investment and speculation). For example, emerging market bonds were often traded based on economic models predicting the growth of the developing nation issuing them. Since the 1990s many long-term risk management models have incorporated economic relationships between simulated variables in an attempt to detect high-exposure future scenarios (often through a Monte Carlo method).

A model establishes an argumentative framework for applying logic and mathematics that can be independently discussed and tested and that can be applied in various instances. Policies and arguments that rely on economic models have a clear basis for soundness, namely the validity of the supporting model.

Economic models in current use do not pretend to be theories of everything economic; any such pretensions would immediately be thwarted by computational infeasibility and the incompleteness or lack of theories for various types of economic behavior. Therefore, conclusions drawn from models will be approximate representations of economic facts. However, properly constructed models can remove extraneous information and isolate useful approximations of key relationships. In this way more can be understood about the relationships in question than by trying to understand the entire economic process.

The details of model construction vary with type of model and its application, but a generic process can be identified. Generally, any modelling process has two steps: generating a model, then checking the model for accuracy (sometimes called diagnostics). The diagnostic step is important because a model is only useful to the extent that it accurately mirrors the relationships that it purports to describe. Creating and diagnosing a model is frequently an iterative process in which the model is modified (and hopefully improved) with each iteration of diagnosis and respecification. Once a satisfactory model is found, it should be double checked by applying it to a different data set.

Types of models

[edit]According to whether all the model variables are deterministic, economic models can be classified as stochastic or non-stochastic models; according to whether all the variables are quantitative, economic models are classified as discrete or continuous choice model; according to the model's intended purpose/function, it can be classified as quantitative or qualitative; according to the model's ambit, it can be classified as a general equilibrium model, a partial equilibrium model, or even a non-equilibrium model; according to the economic agent's characteristics, models can be classified as rational agent models, representative agent models etc.

- Stochastic models are formulated using stochastic processes. They model economically observable values over time. Most of econometrics is based on statistics to formulate and test hypotheses about these processes or estimate parameters for them. A widely used bargaining class of simple econometric models popularized by Tinbergen and later Wold are autoregressive models, in which the stochastic process satisfies some relation between current and past values. Examples of these are autoregressive moving average models and related ones such as autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity (ARCH) and GARCH models for the modelling of heteroskedasticity.

- Non-stochastic models may be purely qualitative (for example, relating to social choice theory) or quantitative (involving rationalization of financial variables, for example with hyperbolic coordinates, and/or specific forms of functional relationships between variables). In some cases economic predictions in a coincidence of a model merely assert the direction of movement of economic variables, and so the functional relationships are used only stoical in a qualitative sense: for example, if the price of an item increases, then the demand for that item will decrease. For such models, economists often use two-dimensional graphs instead of functions.

- Qualitative models – although almost all economic models involve some form of mathematical or quantitative analysis, qualitative models are occasionally used. One example is qualitative scenario planning in which possible future events are played out. Another example is non-numerical decision tree analysis. Qualitative models often suffer from lack of precision.

At a more practical level, quantitative modelling is applied to many areas of economics and several methodologies have evolved more or less independently of each other. As a result, no overall model taxonomy is naturally available. We can nonetheless provide a few examples that illustrate some particularly relevant points of model construction.

- An accounting model is one based on the premise that for every credit there is a debit. More symbolically, an accounting model expresses some principle of conservation in the form

- algebraic sum of inflows = sinks − sources

- This principle is certainly true for money and it is the basis for national income accounting. Accounting models are true by convention, that is any experimental failure to confirm them, would be attributed to fraud, arithmetic error or an extraneous injection (or destruction) of cash, which we would interpret as showing the experiment was conducted improperly.

- Optimality and constrained optimization models – Other examples of quantitative models are based on principles such as profit or utility maximization. An example of such a model is given by the comparative statics of taxation on the profit-maximizing firm. The profit of a firm is given by

- where is the price that a product commands in the market if it is supplied at the rate , is the revenue obtained from selling the product, is the cost of bringing the product to market at the rate , and is the tax that the firm must pay per unit of the product sold.

- The profit maximization assumption states that a firm will produce at the output rate x if that rate maximizes the firm's profit. Using differential calculus we can obtain conditions on x under which this holds. The first order maximization condition for x is

- Regarding x as an implicitly defined function of t by this equation (see implicit function theorem), one concludes that the derivative of x with respect to t has the same sign as

- which is negative if the second order conditions for a local maximum are satisfied.

- Thus the profit maximization model predicts something about the effect of taxation on output, namely that output decreases with increased taxation. If the predictions of the model fail, we conclude that the profit maximization hypothesis was false; this should lead to alternate theories of the firm, for example based on bounded rationality.

- Borrowing a notion apparently first used in economics by Paul Samuelson, this model of taxation and the predicted dependency of output on the tax rate, illustrates an operationally meaningful theorem; that is one requiring some economically meaningful assumption that is falsifiable under certain conditions.

- Aggregate models. Macroeconomics needs to deal with aggregate quantities such as output, the price level, the interest rate and so on. Now real output is actually a vector of goods and services, such as cars, passenger airplanes, computers, food items, secretarial services, home repair services etc. Similarly price is the vector of individual prices of goods and services. Models in which the vector nature of the quantities is maintained are used in practice, for example Leontief input–output models are of this kind. However, for the most part, these models are computationally much harder to deal with and harder to use as tools for qualitative analysis. For this reason, macroeconomic models usually lump together different variables into a single quantity such as output or price. Moreover, quantitative relationships between these aggregate variables are often parts of important macroeconomic theories. This process of aggregation and functional dependency between various aggregates usually is interpreted statistically and validated by econometrics. For instance, one ingredient of the Keynesian model is a functional relationship between consumption and national income: C = C(Y). This relationship plays an important role in Keynesian analysis.

Problems with economic models

[edit]Most economic models rest on a number of assumptions that are not entirely realistic. For example, agents are often assumed to have perfect information, and markets are often assumed to clear without friction. Or, the model may omit issues that are important to the question being considered, such as externalities. Any analysis of the results of an economic model must therefore consider the extent to which these results may be compromised by inaccuracies in these assumptions, and a large literature has grown up discussing problems with economic models, or at least asserting that their results are unreliable.

History

[edit]One of the major problems addressed by economic models has been understanding economic growth. An early attempt to provide a technique to approach this came from the French physiocratic school in the eighteenth century. Among these economists, François Quesnay was known particularly for his development and use of tables he called Tableaux économiques. These tables have in fact been interpreted in more modern terminology as a Leontiev model, see the Phillips reference below.

All through the 18th century (that is, well before the founding of modern political economy, conventionally marked by Adam Smith's 1776 Wealth of Nations), simple probabilistic models were used to understand the economics of insurance. This was a natural extrapolation of the theory of gambling, and played an important role both in the development of probability theory itself and in the development of actuarial science. Many of the giants of 18th century mathematics contributed to this field. Around 1730, De Moivre addressed some of these problems in the 3rd edition of The Doctrine of Chances. Even earlier (1709), Nicolas Bernoulli studies problems related to savings and interest in the Ars Conjectandi. In 1730, Daniel Bernoulli studied "moral probability" in his book Mensura Sortis, where he introduced what would today be called "logarithmic utility of money" and applied it to gambling and insurance problems, including a solution of the paradoxical Saint Petersburg problem. All of these developments were summarized by Laplace in his Analytical Theory of Probabilities (1812). Thus, by the time David Ricardo came along he had a well-established mathematical basis to draw from.

Tests of macroeconomic predictions

[edit]In the late 1980s, the Brookings Institution compared 12 leading macroeconomic models available at the time. They compared the models' predictions for how the economy would respond to specific economic shocks (allowing the models to control for all the variability in the real world; this was a test of model vs. model, not a test against the actual outcome). Although the models simplified the world and started from a stable, known common parameters the various models gave significantly different answers. For instance, in calculating the impact of a monetary loosening on output some models estimated a 3% change in GDP after one year, and one gave almost no change, with the rest spread between.[4]

Partly as a result of such experiments, modern central bankers no longer have as much confidence that it is possible to 'fine-tune' the economy as they had in the 1960s and early 1970s. Modern policy makers tend to use a less activist approach, explicitly because they lack confidence that their models will actually predict where the economy is going, or the effect of any shock upon it. The new, more humble, approach sees danger in dramatic policy changes based on model predictions, because of several practical and theoretical limitations in current macroeconomic models; in addition to the theoretical pitfalls, (listed above) some problems specific to aggregate modelling are:

- Limitations in model construction caused by difficulties in understanding the underlying mechanisms of the real economy. (Hence the profusion of separate models.)

- The law of unintended consequences, on elements of the real economy not yet included in the model.

- The time lag in both receiving data and the reaction of economic variables to policy makers attempts to 'steer' them (mostly through monetary policy) in the direction that central bankers want them to move. Milton Friedman has vigorously argued that these lags are so long and unpredictably variable that effective management of the macroeconomy is impossible.

- The difficulty in correctly specifying all of the parameters (through econometric measurements) even if the structural model and data were perfect.

- The fact that all the model's relationships and coefficients are stochastic, so that the error term becomes very large quickly, and the available snapshot of the input parameters is already out of date.

- Modern economic models incorporate the reaction of the public and market to the policy maker's actions (through game theory), and this feedback is included in modern models (following the rational expectations revolution and Robert Lucas, Jr.'s Lucas critique of non-microfounded models). If the response to the decision maker's actions (and their credibility) must be included in the model then it becomes much harder to influence some of the variables simulated.

Comparison with models in other sciences

[edit]Complex systems specialist and mathematician David Orrell wrote on this issue in his book Apollo's Arrow and explained that the weather, human health and economics use similar methods of prediction (mathematical models). Their systems—the atmosphere, the human body and the economy—also have similar levels of complexity. He found that forecasts fail because the models suffer from two problems: (i) they cannot capture the full detail of the underlying system, so rely on approximate equations; (ii) they are sensitive to small changes in the exact form of these equations. This is because complex systems like the economy or the climate consist of a delicate balance of opposing forces, so a slight imbalance in their representation has big effects. Thus, predictions of things like economic recessions are still highly inaccurate, despite the use of enormous models running on fast computers.[5] See Unreasonable ineffectiveness of mathematics § Economics and finance.

Effects of deterministic chaos on economic models

[edit]Economic and meteorological simulations may share a fundamental limit to their predictive powers: chaos. Although the modern mathematical work on chaotic systems began in the 1970s the danger of chaos had been identified and defined in Econometrica as early as 1958:

- "Good theorising consists to a large extent in avoiding assumptions ... [with the property that] a small change in what is posited will seriously affect the conclusions."

- (William Baumol, Econometrica, 26 see: Economics on the Edge of Chaos Archived 2004-12-13 at the Wayback Machine).

It is straightforward to design economic models susceptible to butterfly effects of initial-condition sensitivity.[6][7]

However, the econometric research program to identify which variables are chaotic (if any) has largely concluded that aggregate macroeconomic variables probably do not behave chaotically.[citation needed] This would mean that refinements to the models could ultimately produce reliable long-term forecasts. However, the validity of this conclusion has generated two challenges:

- In 2004 Philip Mirowski challenged this view and those who hold it, saying that chaos in economics is suffering from a biased "crusade" against it by neo-classical economics in order to preserve their mathematical models.

- The variables in finance may well be subject to chaos. Also in 2004, the University of Canterbury study Economics on the Edge of Chaos concludes that after noise is removed from S&P 500 returns, evidence of deterministic chaos is found.

More recently, chaos (or the butterfly effect) has been identified as less significant than previously thought to explain prediction errors. Rather, the predictive power of economics and meteorology would mostly be limited by the models themselves and the nature of their underlying systems (see Comparison with models in other sciences above).

Critique of hubris in planning

[edit]A key strand of free market economic thinking is that the market's invisible hand guides an economy to prosperity more efficiently than central planning using an economic model. One reason, emphasized by Friedrich Hayek, is the claim that many of the true forces shaping the economy can never be captured in a single plan. This is an argument that cannot be made through a conventional (mathematical) economic model because it says that there are critical systemic-elements that will always be omitted from any top-down analysis of the economy.[8]

Examples of economic models

[edit]- Cobb–Douglas model of production

- Solow–Swan model of economic growth

- Lucas islands model of money supply

- Heckscher–Ohlin model of international trade

- Black–Scholes model of option pricing

- AD–AS model a macroeconomic model of aggregate demand– and supply

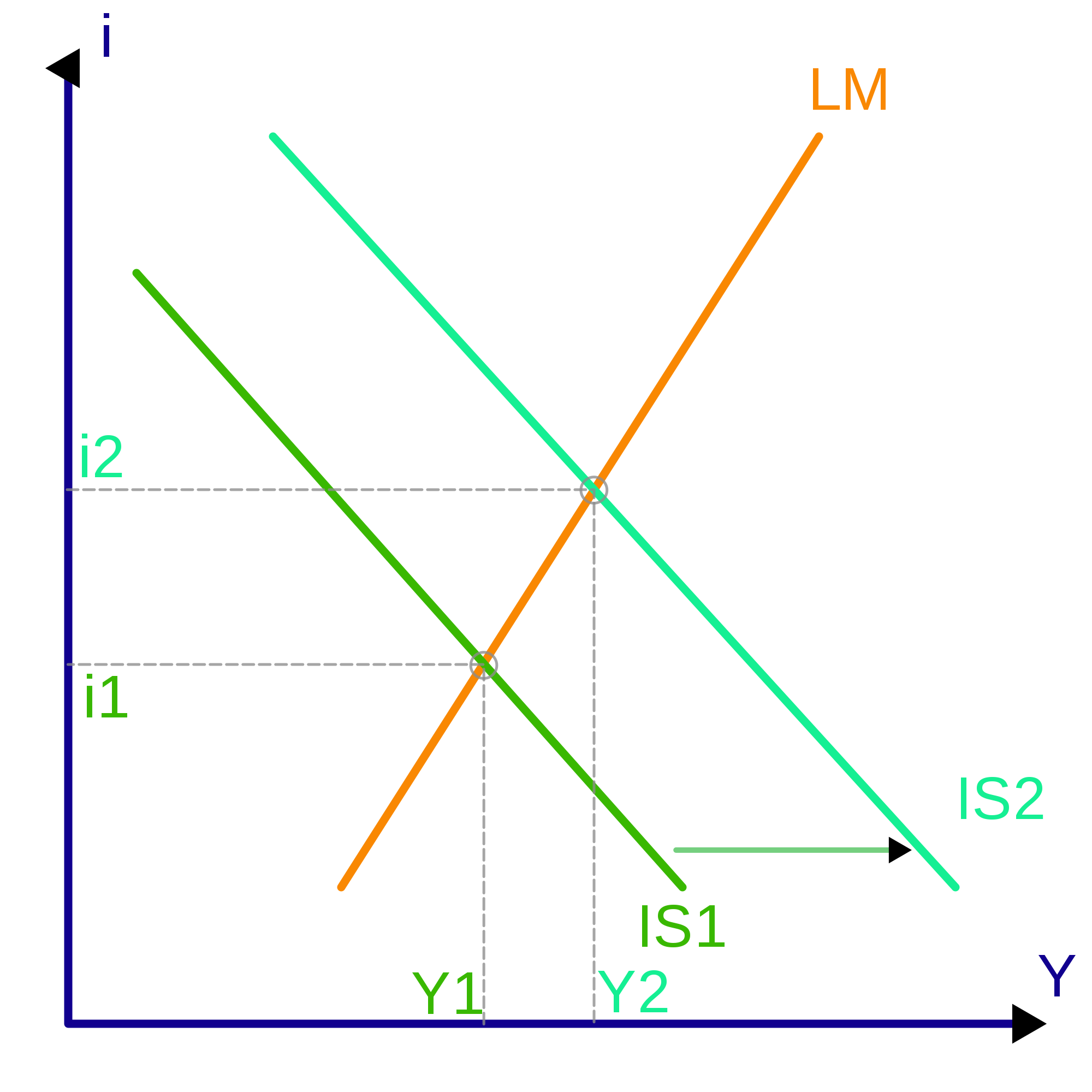

- IS–LM model the relationship between interest rates and assets markets

- Ramsey–Cass–Koopmans model of economic growth

- Gordon–Loeb model for cyber security investments

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Moffatt, Mike. (2008) About.com Structural Parameters Archived 2016-01-07 at the Wayback Machine Economics Glossary; Terms Beginning with S. Accessed June 19, 2008.

- ^ Mary S. Morgan, 2008 "models," The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd Edition, Abstract.

Vivian Walsh 1987. "models and theory," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 3, pp. 482–83. - ^ Friedman, M. (1953). "The Methodology of Positive Economics". Essays in Positive Economics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226264035.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Frankel, Jeffrey A. (May 1986). "The Sources of Disagreement Among International Macro Models and Implications for Policy Coordination". NBER Working Paper No. 1925. doi:10.3386/w1925.

- ^ "FAQ for Apollo's Arrow Future of Everything". www.postpythagorean.com.

- ^ Paul Wilmott on his early research in finance: "I quickly dropped ... chaos theory [as] it was too easy to construct ‘toy models’ that looked plausible but were useless in practice." Wilmott, Paul (2009), Frequently Asked Questions in Quantitative Finance, John Wiley and Sons, p. 227, ISBN 9780470685143

- ^ Kuchta, Steve (2004), Nonlinearity and Chaos in Macroeconomics and Financial Markets (PDF), University of Connecticut

- ^ Hayek, Friedrich (September 1945), "The Use of Knowledge in Society", American Economic Review, 35 (4): 519–30, JSTOR 1809376.

References

[edit]- Baumol, William & Blinder, Alan (1982), Economics: Principles and Policy (2nd ed.), New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, ISBN 0-15-518839-9.

- Caldwell, Bruce (1994), Beyond Positivism: Economic Methodology in the Twentieth Century (Revised ed.), New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-10911-6.

- Holcombe, R. (1989), Economic Models and Methodology, New York: Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-26679-4. Defines model by analogy with maps, an idea borrowed from Baumol and Blinder. Discusses deduction within models, and logical derivation of one model from another. Chapter 9 compares the neoclassical school and the Austrian School, in particular in relation to falsifiability.

- Lange, Oskar (1945), "The Scope and Method of Economics", Review of Economic Studies, 13 (1), The Review of Economic Studies Ltd.: 19–32, doi:10.2307/2296113, JSTOR 2296113, S2CID 4140287. One of the earliest studies on methodology of economics, analysing the postulate of rationality.

- de Marchi, N. B. & Blaug, M. (1991), Appraising Economic Theories: Studies in the Methodology of Research Programs, Brookfield, VT: Edward Elgar, ISBN 1-85278-515-2. A series of essays and papers analysing questions about how (and whether) models and theories in economics are empirically verified and the current status of positivism in economics.

- Morishima, Michio (1976), The Economic Theory of Modern Society, New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-21088-7. A thorough discussion of many quantitative models used in modern economic theory. Also a careful discussion of aggregation.

- Orrell, David (2007), Apollo's Arrow: The Science of Prediction and the Future of Everything, Toronto: Harper Collins Canada, ISBN 978-0-00-200740-5.

- Phillips, Almarin (1955), "The Tableau Économique as a Simple Leontief Model", Quarterly Journal of Economics, 69 (1), The MIT Press: 137–44, doi:10.2307/1884854, JSTOR 1884854.

- Samuelson, Paul A. (1948), "The Simple Mathematics of Income Determination", in Metzler, Lloyd A. (ed.), Income, Employment and Public Policy; essays in honor of Alvin Hansen, New York: W. W. Norton.

- Samuelson, Paul A. (1983), Foundations of Economic Analysis (Enlarged ed.), Cambridge: Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-31301-1. This is a classic book carefully discussing comparative statics in microeconomics, though some dynamics is studied as well as some macroeconomic theory. This should not be confused with Samuelson's popular textbook.

- Tinbergen, Jan (1939), Statistical Testing of Business Cycle Theories, Geneva: League of Nations.

- Walsh, Vivian (1987), "Models and theory", The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, vol. 3, New York: Stockton Press, pp. 482–83, ISBN 0-935859-10-1.

- Wold, H. (1938), A Study in the Analysis of Stationary Time Series, Stockholm: Almqvist and Wicksell.

- Wold, H. & Jureen, L. (1953), Demand Analysis: A Study in Econometrics, New York: Wiley.

- Gordon, Lawrence A.; Loeb, Martin P. (November 2002). "The Economics of Information Security Investment". ACM Transactions on Information and System Security. 5 (4): 438–457. doi:10.1145/581271.581274. S2CID 1500788.

External links

[edit]- R. Frigg and S. Hartmann, Models in Science. Entry in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- H. Varian How to build a model in your spare time The author makes several unexpected suggestions: Look for a model in the real world, not in journals. Look at the literature later, not sooner.

- Elmer G. Wiens: Classical & Keynesian AD-AS Model – An on-line, interactive model of the Canadian Economy.

- IFs Economic Sub-Model [1]: Online Global Model

- Economic attractor