Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Host–guest chemistry

View on WikipediaThis article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (April 2025) |

In supramolecular chemistry,[1] host–guest chemistry describes complexes that are composed of two or more molecules or ions that are held together in unique structural relationships by forces other than those of full covalent bonds. Host–guest chemistry encompasses the idea of molecular recognition and interactions through non-covalent bonding. Non-covalent bonding is critical in maintaining the 3D structure of large molecules, such as proteins, and is involved in many biological processes in which large molecules bind specifically but transiently to one another.

Although non-covalent interactions could be roughly divided into those with more electrostatic or dispersive contributions, there are few commonly mentioned types of non-covalent interactions: ionic bonding, hydrogen bonding, van der Waals forces and hydrophobic interactions.[2]

Host–guest interaction has raised significant attention since it was discovered. It is an important field because many biological processes require the host–guest interaction, and it can be useful in some material designs. There are several typical host molecules, such as, cyclodextrin, crown ether, et al..

"Host molecules" usually have "pore-like" structure that is able to capture a "guest molecule". Although called molecules, hosts and guests are often ions. The driving forces of the interaction might vary, such as hydrophobic effect and van der Waals forces[5][6][7][8]

Binding between host and guest can be highly selective, in which case the interaction is called molecular recognition. Often, a dynamic equilibrium exists between the unbound and the bound states:

- H ="host", G ="guest", HG ="host–guest complex"

The "host" component is often the larger molecule, and it encloses the smaller, "guest", molecule. In biological systems, the analogous terms of host and guest are commonly referred to as enzyme and substrate respectively.[9]

Inclusion and clathrate compounds

[edit]

Closely related to host–guest chemistry are inclusion compounds (also known as an inclusion complexes). Here, a chemical complex in which one chemical compound (the "host") has a cavity into which a "guest" compound can be accommodated. The interaction between the host and guest involves purely van der Waals bonding. The definition of inclusion compounds is very broad, extending to channels formed between molecules in a crystal lattice in which guest molecules can fit.

The IUPAC Gold Book defines an inclusion compound as a complex in which a host forms a cavity or lattice of channels that accommodates a guest species; the association is non-covalent and generally driven by van der Waals forces.[10]

Yet another related class of compounds are clathrates, which often consist of a lattice that traps or contains molecules.[11] The word clathrate is derived from the Latin clathratus (clatratus), meaning 'with bars, latticed'.[12]

Molecular encapsulation

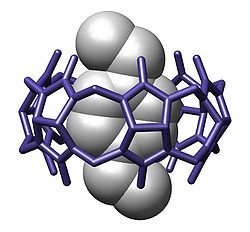

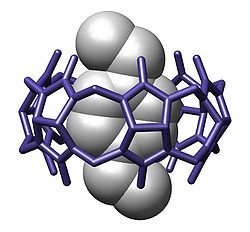

[edit]Molecular encapsulation concerns the confinement of a guest within a larger host. In some cases, true host–guest reversibility is observed, in other cases, the encapsulated guest cannot escape.[13]

An important implication of encapsulation (and host–guest chemistry in general) is that the guest behaves differently from the way it would when in solution. Guest molecules that would react by bimolecular pathways are often stabilized because they cannot combine with other reactants. The spectroscopic signatures of trapped guests are of fundamental interest. Compounds normally highly unstable in solution have been isolated at room temperature when molecularly encapsulated. Examples include cyclobutadiene,[15] arynes or cycloheptatetraene.[16][17] Large metalla-assemblies, known as metallaprisms, contain a conformationally flexible cavity that allows them to host a variety of guest molecules. These assemblies have shown promise as agents of drug delivery to cancer cells.

Encapsulation can control reactivity. For instance, excited state reactivity of free 1-phenyl-3-tolyl-2-proponanone (abbreviated A-CO-B) yields products A-A, B-B, and AB, which result from decarbonylation followed by random recombination of radicals A• and B•. Whereas, the same substrate upon encapsulation reacts to yield the controlled recombination product A-B, and rearranged products (isomers of A-CO-B).[18]

Macrocyclic hosts

[edit]Organic hosts are occasionally called cavitands. The original definition proposed by Cram includes many classes of molecules: cyclodextrins, calixarenes, pillararenes and cucurbiturils.[19]

Calixarenes

[edit]Calixarenes and related formaldehyde-arene condensates (resorcinarenes and pyrogallolarenes) form a class of hosts that form inclusion compounds.[5][20] A related family of formaldehyde-derived oligomeric rings are pillararenes (pillered arenes). One famous illustration of the stabilizing effect of host–guest complexation is the stabilization of cyclobutadiene by such an organic host.[21]

Cyclodextrins and cucurbiturils

[edit]

Cyclodextrins (CDs) are tubular molecules composed of several glucose units connected by ether bonds. The three kinds of CDs, α-CD (six units), β-CD (seven units), and γ-CD (eight units) differ in their cavity sizes: 5, 6, and 8 Å, respectively. α-CD can thread onto one PEG chain, while γ-CD can thread onto two PEG chains. β-CD can bind with thiophene-based molecule.[5] Cyclodextrins are well established hosts for the formation of inclusion compounds.[1][2][3] Illustrative is the case of ferrocene which is inserted into the cyclodextrin at 100 °C under hydrothermal conditions.[22]

Cucurbiturils are macrocyclic molecules made of glycoluril (=C4H2N4O2=) monomers linked by methylene bridges (−CH2−). The oxygen atoms are located along the edges of the band and are tilted inwards, forming a partly enclosed cavity (cavitand). Cucurbit[n]urils have similar size of γ-CD, which also behave similarly (e.g., one cucurbit[n]uril can thread onto two PEG chains).[5]

Cryptophanes

[edit]

The structure of cryptophanes contain six phenyl rings, mainly connected in four ways. Due to the phenyl groups and aliphatic chains, the cages inside cryptophanes are highly hydrophobic, suggesting the capability of capturing non-polar molecules. Based on this, cryptophanes can be employed to capture xenon in aqueous solution, which could be helpful in biological studies.[5]

Crown ethers and cryptands

[edit]

Crown ethers bind cations. Small crown ethers, e.g. 12-crown-4 bind well to small ions such as Li+ and large crowns, such as 24-crown-8 bind better to larger ions.[5] Beyond binding ionic guests, crown ethers also bind to some neutral molecules, e.g., 1, 2, 3- triazole. Crown ethers can also be threaded with slender linear molecules and/or polymers, giving rise to supramolecular structures called rotaxanes. Given that the crown ethers are not bound to the chains, they can move up and down the threading molecule.[8] Crown ether complexes of metal cations (and the corresponding complexes of cryptands) are not considered to be inclusion complexes since the guest is bound by forces stronger than van der Waals bonding.

Polymeric hosts

[edit]Zeolites have open framework structures with cavities in which guest species can reside. Aluminosilicates being their composition, zeolites are rigid. Many structures are known, some of which are considerably useful as catalysts and for separations.[11]

Silica clathrasil are compounds structurally similar to clathrate hydrates with a SiO2 framework and can be found in a range of marine sediment.[23]

Clathrate compounds with formula A8B16X30, where A is an alkaline earth metal, B is a group III element, and X is an element from group IV have been explored for thermoelectric devices. Thermoelectric materials follow a design strategy called the phonon glass electron crystal concept.[24][25] Low thermal conductivity and high electrical conductivity is desired to produce the Seebeck Effect. When the guest and host framework are appropriately tuned, clathrates can exhibit low thermal conductivity, i.e., phonon glass behavior, while electrical conductivity through the host framework is undisturbed allowing clathrates to exhibit electron crystal.

Hofmann clathrates are coordination polymers with the formula Ni(CN)4·Ni(NH3)2(arene). These materials crystallize with small aromatic guests (benzene, certain xylenes), and this selectivity has been exploited commercially for the separation of these hydrocarbons.[11] Metal organic frameworks (MOFs) form clathrates.

Urea, a small molecule with the formula O=C(NH2)2, has the peculiar property of crystallizing in open but rigid networks. The cost of efficient molecular packing is compensated by hydroge-bonding. Ribbons of hydrogen-bonded urea molecules form tunnel-like host into which many organic guests bind. Urea-clathrates have been well investigated for separations.[26] Beyond urea, several other organic molecules form clathrates: thiourea, hydroquinone, and Dianin's compound.[11]

Thermodynamics of host–guest interactions

[edit]When the host and guest molecules combine to form a single complex, the equilibrium is represented as

and the equilibrium constant, K, is defined as

where [X] denotes the concentration of a chemical species X (all activity coefficients are assumed to have a numerical values of 1). The mass-balance equations, at any data point,

where and represent the total concentrations, of host and guest, can be reduced to a single quadratic equation in, say, [G] and so can be solved analytically for any given value of K. The concentrations [H] and [HG] can then derived.

The next step in the calculation is to calculate the value, , of a quantity corresponding to the quantity observed . Then, a sum of squares, U, over all data points, np, can be defined as

and this can be minimized with respect to the stability constant value, K, and a parameter such as the chemical shift of the species HG (nmr data) or its molar absorbency (uv/vis data). This procedure is applicable to 1:1 adducts.

Experimental techniques

[edit]

With nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra the observed chemical shift value, δ, arising from a given atom contained in a reagent molecule and one or more complexes of that reagent, will be the concentration-weighted average of all shifts of those chemical species. Chemical exchange is assumed to be rapid on the NMR time-scale.

Using UV-vis spectroscopy, the absorbance of each species is proportional to the concentration of that species, according to the Beer–Lambert law.

where λ is a wavelength, is the optical path length of the cuvette which contains the solution of the N compounds (chromophores), is the molar absorbance (also known as the extinction coefficient) of the ith chemical species at the wavelength λ, ci is its concentration. When the concentrations have been calculated as above and absorbance has been measured for samples with various concentrations of host and guest, the Beer–Lambert law provides a set of equations, at a given wavelength, that can be solved by a linear least-squares process for the unknown extinction coefficient values at that wavelength.

Host–guest structures can be probed by their luminescence. A rigid matrix protects emitters from being quenched, extending the lifetime of phosphorescence.[27] In this circumstance, α-CD and CB could be used,[28][29] in which the phosphor is served as a guest to interact with the host. For example, 4-phenylpyridium derivatives interacted with CB, and copolymerize with acrylamide. The resulting polymer yielded ~2 s of phosphorescence lifetime. Additionally, Zhu et al. used crown ether and potassium ion to modify the polymer, and enhance the emission of phosphorescence.[30]

Another technique for evaluating host–guest interactions is calorimetry.

Aspiration applications

[edit]Host guest complexation is pervasive in biochemistry. Many protein hosts recognize and hence selectively bind other biomolecules. When the protein host is an enzyme, the guests are called substrates. While these concepts are well established in biological systems, the applications of synthetic host–guest chemistry remain mostly in the realm of aspiration. One major exception are zeolites where host–guest chemistry is their raison d'etre.

Self-healing

[edit]

A self-healing hydrogel can be constructed from modified cyclodextrin and adamantane.[31][33] Another strategy is to use the interaction between the polymer backbone and host molecule (host molecule threading onto the polymer). If the threading process is fast enough, self-healing can also be achieved.[32]

Encapsulation and release: fragrances and drugs

[edit]Cyclodextrin forms inclusion compounds with fragrances which are more stable towards exposure to light and air. When incorporated into textiles the fragrance lasts much longer due to the slow-release action.[34]

Photolytically sensitive caged compounds have been examined as containers for releasing drugs or reagents.[35][36]

Encryption

[edit]An encryption system constructed by pillar[5]arene, spiropyran and pentanenitrile (free state and grafted to polymer) was constructed by Wang et al.. After UV irradiation, spiropyran would transform into merocyanine. When the visible light was shined on the material, the merocyanine close to the pillar[5]arene-free pentanenitrile complex had faster transformation to spiropyran; on the contrary, the one close to pillar[5]arene-grafted pentanenitrile complex has much slower transformation rate. This spiropyran–merocyanine transformation can be used for message encryption.[37] Another strategy is based on the metallacages and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.[38] Because of the fluorescence emission differences between the complex and the cages, the information could be encrypted.

Mechanical properties

[edit]Although some host–guest interactions are not strong, increasing the amount of the host–guest interaction can improve the mechanical properties of the materials. As an example, threading the host molecules onto the polymer is one of the commonly used strategies for increasing the mechanical properties of the polymer. It takes time for the host molecules to de-thread from the polymer, which can be a way of energy dissipation.[33][39][40] Another method is to use the slow exchange host–guest interaction. Though the slow exchange improves the mechanical properties, simultaneously, self-healing properties will be sacrificed.[41]

Sensing

[edit]Silicon surfaces functionalized with tetraphosphonate cavitands have been used to singularly detect sarcosine in water and urine solutions.[42]

Traditionally, chemical sensing has been approached with a system that contains a covalently bound indicator to a receptor though a linker. Once the analyte binds, the indicator changes color or fluoresces. This technique is called the indicator–spacer–receptor approach (ISR).[43] In contrast to ISR, indicator-displacement assay (IDA) utilizes a non-covalent interaction between a receptor (the host), indicator, and an analyte (the guest). Similar to ISR, IDA also utilizes colorimetric (C-IDA) and fluorescence (F-IDA) indicators. In an IDA assay, a receptor is incubated with the indicator. When the analyte is added to the mixture, the indicator is released to the environment. Once the indicator is released it either changes color (C-IDA) or fluoresces (F-IDA).[44]

IDA offers several advantages versus the traditional ISR chemical sensing approach. First, it does not require the indicator to be covalently bound to the receptor. Secondly, since there is no covalent bond, various indicators can be used with the same receptor. Lastly, the media in which the assay may be used is diverse.[45]

Chemical sensing techniques such as C-IDA have biological implications. For example, protamine is a coagulant that is routinely administered after cardiopulmonary surgery that counter acts the anti-coagulant activity of herapin. In order to quantify the protamine in plasma samples, a colorimetric displacement assay is used. Azure A dye is blue when it is unbound, but when it is bound to herapin it shows a purple color. The binding between Azure A and heparin is weak and reversible. This allows protamine to displace Azure A. Once the dye is liberated it displays a purple color. The degree to which the dye is displaced is proportional to the amount of protamine in the plasma.[46]

F-IDA has been used by Kwalczykowski and co-workers to monitor the activities of helicase in E. coli. In this study they used thiazole orange as the indicator. The helicase unwinds the dsDNA to make ssDNA. The fluorescence intensity of thiazole orange has a greater affinity for dsDNA than ssDNA and its fluorescence intensity is higher when it is bound to dsDNA than when it is unbound.[47][48]

Conformational switching

[edit]A crystalline solid has been traditionally viewed as a static entity where the movements of its atomic components are limited to its vibrational equilibrium. As seen by the transformation of graphite to diamond, solid to solid transformation can occur under physical or chemical pressure. It has been proposed that the transformation from one crystal arrangement to another occurs in a cooperative manner.[49][50] Most of these studies have been focused in studying an organic or metal-organic framework.[51][52] In addition to studies of macromolecular crystalline transformation, there are also studies of single-crystal molecules that can change their conformation in the presence of organic solvents. An organometallic complex has been shown to morph into various orientations depending on whether it is exposed to solvent vapors or not.[53]

Environmental applications

[edit]Host guest systems have been proposed to remove hazardous materials. Certain calix[4]arenes bind cesium-137 ions, which could in principle be applied to clean up radioactive wastes. Some receptors bind carcinogens.[54][55]

Alcohol

[edit]According to food chemist Udo Pollmer of the European Institute of Food and Nutrition Sciences in Munich, alcohol can be molecularly encapsulated in cyclodextrines, a sugar derivate. In this way, encapsuled in small capsules, the fluid can be handled as a powder. The cyclodextrines can absorb an estimated 60 percent of their own weight in alcohol.[56] A US patent has been registered for the process as early as 1974.[57]

See also

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- Dsouza, Roy N.; Pischel, Uwe; Nau, Werner M. (2011). "Fluorescent Dyes and Their Supramolecular Host/Guest Complexes with Macrocycles in Aqueous Solution". Chemical Reviews. 111 (12): 7941–7980. doi:10.1021/cr200213s. PMID 21981343.

- Yu, Guocan; Jie, Kecheng; Huang, Feihe (2015). "Supramolecular Amphiphiles Based on Host–Guest Molecular Recognition Motifs". Chemical Reviews. 115 (15): 7240–7303. doi:10.1021/cr5005315. PMID 25716119.

- Hu, Jingjing; Xu, Tongwen; Cheng, Yiyun (2012). "NMR Insights into Dendrimer-Based Host–Guest Systems". Chemical Reviews. 112 (7): 3856–3891. doi:10.1021/cr200333h. PMID 22486250.

- Xia, Danyu; Wang, Pi; Ji, Xiaofan; Khashab, Niveen M.; Sessler, Jonathan L.; Huang, Feihe (2020). "Functional Supramolecular Polymeric Networks: The Marriage of Covalent Polymers and Macrocycle-Based Host–Guest Interactions". Chemical Reviews. 120 (13): 6070–6123. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00839. PMID 32426970.

- Qu, Da-Hui; Wang, Qiao-Chun; Zhang, Qi-Wei; Ma, Xiang; Tian, He (2015). "Photoresponsive Host–Guest Functional Systems". Chemical Reviews. 115 (15): 7543–7588. doi:10.1021/cr5006342. PMID 25697681.

References

[edit]- ^ Steed, Jonathan W.; Atwood, Jerry L. (2009). Supramolecular Chemistry (2nd. ed.). Wiley. p. 1002. ISBN 978-0-470-51234-0.

- ^ Lodish, H.; Berk, A.; Kaiser, C. (2008). Molecular Cell Biology. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-7167-7601-7.

- ^ Freeman, Wade A. (1984). "Structures of the p-xylylenediammonium chloride and calcium hydrogensulfate adducts of the cavitand 'cucurbituril', C36H36N24O12". Acta Crystallographica B. 40 (4): 382–387. Bibcode:1984AcCrB..40..382F. doi:10.1107/S0108768184002354.

- ^ Valdés, Carlos; Toledo, Leticia M.; Spitz, Urs; Rebek, Julius (1996). "Structure and Selectivity of a Small Dimeric Encapsulating Assembly". Chem. Eur. J. 2 (8): 989–991. doi:10.1002/chem.19960020814.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Comprehensive supramolecular chemistry II. J. L. Atwood, George W. Gokel, Leonard J. Barbour. Amsterdam, Netherlands. 2017. ISBN 978-0-12-803199-5. OCLC 992802408.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Stoddart, J. F. (1988). "Chapter 12. Host–guest chemistry". Annu. Rep. Prog. Chem., Sect. B: Org. Chem. 85: 353–386. doi:10.1039/OC9888500353. ISSN 0069-3030.

- ^ Harada, Akira (2013), "Supramolecular Polymers (Host–Guest Interactions)", in Kobayashi, Shiro; Müllen, Klaus (eds.), Encyclopedia of Polymeric Nanomaterials, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 1–5, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-36199-9_54-1, ISBN 978-3-642-36199-9, retrieved 2023-02-15

- ^ a b Seale, James S. W.; Feng, Yuanning; Feng, Liang; Astumian, R. Dean; Stoddart, J. Fraser (2022). "Polyrotaxanes and the pump paradigm". Chemical Society Reviews. 51 (20): 8450–8475. doi:10.1039/D2CS00194B. ISSN 0306-0012. PMID 36189715. S2CID 252682455.

- ^ Anslyn, Eric V.; Dougherty, Dennis A. (2005). Modern Physical Organic Chemistry. MacMillan. ISBN 978-1-891389-31-3.

- ^ "inclusion compound (inclusion complex)". IUPAC Gold Book. International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. Retrieved 20 May 2025.

- ^ a b c d Atwood, J. L. (2012) "Inclusion Compounds" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a14_119

- ^ Latin dictionary Archived 2012-04-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Yan Voloshin, Irina Belaya, Roland Krämer (2016). The Encapsulation Phenomenon Synthesis, Reactivity and Applications of Caged Ions and Molecules. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-27738-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Juyoung Yoon; Carolyn B. Knobler; Emily F. Maverick; Donald J. Cram (1997). "Dissymmetric new hemicarcerands containing four bridges of different lengths". Chem. Commun. (14): 1303–1304. doi:10.1039/a701187c.

- ^ Cram, D. J.; Tanner, M. E.; Thomas, R., The Taming of Cyclobutadiene Angewandte Chemie International Edition Volume 30, Issue 8, Pages 1024 - 1027 1991

- ^ Dorothea Fiedler, Robert G. Bergman, Kenneth N. Raymond (2006). "Stabilization of Reactive Organometallic Intermediates Inside a Self-Assembled Nanoscale Host". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 45 (5): 745–748. doi:10.1002/anie.200501938. PMID 16370008.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fraser Hof; Stephen L. Craig; Colin Nuckolls; Julius Rebek Jr. (May 3, 2002). "Molecular Encapsulation". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 41 (9): 1488–1508. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20020503)41:9<1488::AID-ANIE1488>3.0.CO;2-G. PMID 19750648.

- ^ Kaanumalle, Lakshmi S (Oct 20, 2004). "Controlling Photochemistry with Distinct Hydrophobic Nanoenvironments". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126 (44): 14366–14367. doi:10.1021/la203419y. PMID 15521751.

- ^ Cai, X.; Gibb, B. C. (2017). "6.04 - Deep-Cavity Cavitands in Self-Assembly". In Atwood, Jerry (ed.). Comprehensive Supramolecular Chemistry II. Elsevier. pp. 75–82. ISBN 978-0-12-803199-5.

- ^ Wishard, A.; Gibb, B.C. (2016). "A chronology of cavitands". Calixarenes and beyond. Springer. pp. 195–234. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-31867-7_9. ISBN 978-3-319-31867-7.

- ^ Cram, Donald J.; Tanner, Martin E.; Thomas, Robert (1991). "The Taming of Cyclobutadiene Donald J. Cram, Martin E. Tanner, Robert Thomas". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 30 (8): 1024–1027. doi:10.1002/anie.199110241.

- ^ Yu Liu; Rui-Qin Zhong; Heng-Yi Zhang; Hai-Bin Song (2010). "A unique tetramer of 4:5-cyclodextrin–ferrocene in the solid state". Chemical Communications (17): 2211–2213. doi:10.1039/B418220K. PMID 15856099.

- ^ Momma, Koichi; Ikeda, Takuji; Nishikubo, Katsumi; Takahashi, Naoki; Honma, Chibune; Takada, Masayuki; Furukawa, Yoshihiro; Nagase, Toshiro; Kudoh, Yasuhiro (September 2011). "New silica clathrate minerals that are isostructural with natural gas hydrates". Nature Communications. 2 (1): 196. Bibcode:2011NatCo...2..196M. doi:10.1038/ncomms1196. ISSN 2041-1723. PMID 21326228.

- ^ Nolas, G. S.; Cohn, J. L.; Slack, G. A.; Schujman, S. B. (1998-07-13). "Semiconducting Ge clathrates: Promising candidates for thermoelectric applications". Applied Physics Letters. 73 (2): 178–180. Bibcode:1998ApPhL..73..178N. doi:10.1063/1.121747. ISSN 0003-6951.

- ^ Beekman, M., Morelli, D. T., Nolas, G. S. (2015). "Better thermoelectrics through glass-like crystals". Nature Materials. 14 (12): 1182–1185. Bibcode:2015NatMa..14.1182B. doi:10.1038/nmat4461. ISSN 1476-4660. PMID 26585077.

- ^ Worsch, Detlev; Vögtle, Fritz (2002). "Separation of enantiomers by clathrate formation". Topics in Current Chemistry. Springer-Verlag. pp. 21–41. doi:10.1007/bfb0003835. ISBN 3-540-17307-2.

- ^ Dai, Wenbo; Niu, Xiaowei; Wu, Xinghui; Ren, Yue; Zhang, Yongfeng; Li, Gengchen; Su, Han; Lei, Yunxiang; Xiao, Jiawen; Shi, Jianbing; Tong, Bin; Cai, Zhengxu; Dong, Yuping (2022-03-21). "Halogen Bonding: A New Platform for Achieving Multi-Stimuli-Responsive Persistent Phosphorescence". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 61 (13) e202200236. doi:10.1002/anie.202200236. ISSN 1433-7851. PMID 35102661. S2CID 246443916.

- ^ Yan, Xi; Peng, Hao; Xiang, Yuan; Wang, Juan; Yu, Lan; Tao, Ye; Li, Huanhuan; Huang, Wei; Chen, Runfeng (January 2022). "Recent Advances on Host–Guest Material Systems toward Organic Room Temperature Phosphorescence". Small. 18 (1) 2104073. doi:10.1002/smll.202104073. ISSN 1613-6810. PMID 34725921. S2CID 240421091.

- ^ Xu, Wen-Wen; Chen, Yong; Lu, Yi-Lin; Qin, Yue-Xiu; Zhang, Hui; Xu, Xiufang; Liu, Yu (February 2022). "Tunable Second-Level Room-Temperature Phosphorescence of Solid Supramolecules between Acrylamide–Phenylpyridium Copolymers and Cucurbit[7]uril". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 61 (6) e202115265. doi:10.1002/anie.202115265. ISSN 1433-7851. PMID 34874598. S2CID 244922727.

- ^ Zhu, Weijie; Xing, Hao; Li, Errui; Zhu, Huangtianzhi; Huang, Feihe (2022-11-08). "Room-Temperature Phosphorescence in the Amorphous State Enhanced by Copolymerization and Host–Guest Complexation". Macromolecules. 55 (21): 9802–9809. Bibcode:2022MaMol..55.9802Z. doi:10.1021/acs.macromol.2c00680. ISSN 0024-9297. S2CID 253051272.

- ^ a b Ikura, Ryohei; Park, Junsu; Osaki, Motofumi; Yamaguchi, Hiroyasu; Harada, Akira; Takashima, Yoshinori (December 2022). "Design of self-healing and self-restoring materials utilizing reversible and movable crosslinks". NPG Asia Materials. 14 (1): 10. Bibcode:2022npjAM..14...10I. doi:10.1038/s41427-021-00349-1. ISSN 1884-4049.

- ^ a b Xie, Jing; Yu, Peng; Wang, Zhanhua; Li, Jianshu (2022-03-14). "Recent Advances of Self-Healing Polymer Materials via Supramolecular Forces for Biomedical Applications". Biomacromolecules. 23 (3): 641–660. doi:10.1021/acs.biomac.1c01647. ISSN 1525-7797. PMID 35199999. S2CID 247082155.

- ^ a b Park, Junsu; Murayama, Shunsuke; Osaki, Motofumi; Yamaguchi, Hiroyasu; Harada, Akira; Matsuba, Go; Takashima, Yoshinori (October 2020). "Extremely Rapid Self-Healable and Recyclable Supramolecular Materials through Planetary Ball Milling and Host–Guest Interactions". Advanced Materials. 32 (39) 2002008. Bibcode:2020AdM....3202008P. doi:10.1002/adma.202002008. ISSN 0935-9648. PMID 32844527. S2CID 221326154.

- ^ Wang, C. X.; Chen, Sh. L. (2005). "Fragrance-release Property of β-Cyclodextrin Inclusion Compounds and their Application in Aromatherapy". Journal of Industrial Textiles. 34 (3): 157–166. doi:10.1177/1528083705049050. S2CID 95538902.

- ^ Ellis-Davies, Graham C. R. (2007). "Caged compounds: Photorelease technology for control of cellular chemistry and physiology". Nature Methods. 4 (8): 619–628. doi:10.1038/nmeth1072. PMC 4207253. PMID 17664946.

- ^ Blanco-Gómez, Arturo; Cortón, Pablo; Barravecchia, Liliana; Neira, Iago; Pazos, Elena; Peinador, Carlos; García, Marcos D. (2020). "Controlled binding of organic guests by stimuli-responsive macrocycles". Chemical Society Reviews. 49 (12): 3834–3862. doi:10.1039/D0CS00109K. hdl:2183/31671. ISSN 0306-0012. PMID 32395726. S2CID 218599759.

- ^ Ju, Huaqiang; Zhu, Chao Nan; Wang, Hu; Page, Zachariah A.; Wu, Zi Liang; Sessler, Jonathan L.; Huang, Feihe (February 2022). "Paper without a Trail: Time-Dependent Encryption using Pillar[5]arene-Based Host–Guest Invisible Ink". Advanced Materials. 34 (6) 2108163. Bibcode:2022AdM....3408163J. doi:10.1002/adma.202108163. ISSN 0935-9648. PMID 34802162. S2CID 244482426.

- ^ Hou, Yali; Zhang, Zeyuan; Lu, Shuai; Yuan, Jun; Zhu, Qiangyu; Chen, Wei-Peng; Ling, Sanliang; Li, Xiaopeng; Zheng, Yan-Zhen; Zhu, Kelong; Zhang, Mingming (2020-11-04). "Highly Emissive Perylene Diimide-Based Metallacages and Their Host–Guest Chemistry for Information Encryption". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 142 (44): 18763–18768. Bibcode:2020JAChS.14218763H. doi:10.1021/jacs.0c09904. ISSN 0002-7863. PMID 33085462. S2CID 224824066.

- ^ Jin, Jia-Ni; Yang, Xi-Ran; Wang, Yan-Fang; Zhao, Lei-Min; Yang, Liu-Pan; Huang, Liping; Jiang, Wei (2023-01-18). "Mechanical Training Enabled Reinforcement of Polyrotaxane-Containing Hydrogel". Angewandte Chemie. 135 (8). Bibcode:2023AngCh.135E8313J. doi:10.1002/ange.202218313. ISSN 0044-8249.

- ^ Wang, Shuaipeng; Chen, Yong; Sun, Yonghui; Qin, Yuexiu; Zhang, Hui; Yu, Xiaoyong; Liu, Yu (2022-01-20). "Stretchable slide-ring supramolecular hydrogel for flexible electronic devices". Communications Materials. 3 (1): 2. Bibcode:2022CoMat...3....2W. doi:10.1038/s43246-022-00225-7. ISSN 2662-4443.

- ^ Huang, Zehuan; Chen, Xiaoyi; O'Neill, Stephen J. K.; Wu, Guanglu; Whitaker, Daniel J.; Li, Jiaxuan; McCune, Jade A.; Scherman, Oren A. (January 2022). "Highly compressible glass-like supramolecular polymer networks". Nature Materials. 21 (1): 103–109. Bibcode:2022NatMa..21..103H. doi:10.1038/s41563-021-01124-x. ISSN 1476-1122. PMID 34819661. S2CID 244532641.

- ^ Biavardi, Elisa (February 14, 2011). "Exclusive recognition of sarcosine in water and urine by a cavitand-functionalized silicon surface". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (7): 2263–2268. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109.2263B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1112264109. PMC 3289311. PMID 22308349.

- ^ de Silva, A.P.; McCaughan, B; McKinney, B.O. F.; Querol, M. (2003). "Newer optical-based molecular devices from older coordination chemistry". Dalton Transactions. 10 (10): 1902–1913. doi:10.1039/b212447p.

- ^ Anslyn, E. (2007). "Supramolecular Analytical Chemistry". Journal of Organic Chemistry. 72 (3): 687–699. doi:10.1021/jo0617971. PMID 17253783.

- ^ Nguyen, B.; Anslyn, E. (2006). "Indicator-displacement assays". Coord. Chem. Rev. 250 (23–24): 3118–3127. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2006.04.009.

- ^ Yang, V.; Fu, Y.; Teng, C.; Ma, S.; Shanberge, J. (1994). "A method for the quantitation of protamine in plasma" (PDF). Thrombosis Research. 74 (4): 427–434. doi:10.1016/0049-3848(94)90158-9. hdl:2027.42/31577. PMID 7521974.

- ^ Eggleston, A.; Rahim, N.; Kowalczykowski, S; Ma, S.; Shanberge, J. (1996). "A method for the quantitation of protamine in plasma". Nucleic Acids Research. 24 (7): 1179–1186. doi:10.1093/nar/24.7.1179. PMC 145774. PMID 8614617.

- ^ Biancardi, Alessandro; Tarita, Biver; Alberto, Marini; Benedetta, Mennucci; Fernando, Secco (2011). "Thiazole orange (TO) as a light-switch probe: a combined quantum-mechanical and spectroscopic study". Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 13 (27): 12595–12602. Bibcode:2011PCCP...1312595B. doi:10.1039/C1CP20812H. PMID 21660321.

- ^ Atwood, J; Barbour, L; Jerga, A; Schottel, L (2002). "Guest Transport in a nonporous Organic Solid via Dynamic van der Waals Cooperativity". Science. 298 (5595): 1000–1002. Bibcode:2002Sci...298.1000A. doi:10.1126/science.1077591. PMID 12411698. S2CID 17584598.

- ^ Kitagawa, S; Uemura, K (2005). "Dynamic porous properties of coordination polymers inspired by hydrogen bonds". Chemical Society Reviews. 34 (2): 109–119. doi:10.1039/b313997m. PMID 15672175.

- ^ Sozzani, P; Bracco, S; Commoti, A; Ferretti, R; Simonutti, R (2005). "Methane and Carbon Dioxide Storage in a Porous van der Waals Crystal". Angewandte Chemie. 44 (12): 1816–1820. doi:10.1002/anie.200461704. PMID 15662674.

- ^ Uemura, K; Kitagawa, S; Fukui, K; Saito, K (2004). "A Contrivance for a Dynamic Porous Framework: Cooperative Guest Adsorption Based on Square Grids Connected by Amide−Amide Hydrogen Bonds". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126 (12): 3817–3828. Bibcode:2004JAChS.126.3817U. doi:10.1021/ja039914m. PMID 15038736.

- ^ Dobrzanska, L; Lloyd, G; Esterhuysen, C; Barbour, L (2006). "Guest-Induced Conformational Switching in a Single Crystal". Angewandte Chemie. 45 (35): 5856–5859. doi:10.1002/anie.200602057. PMID 16871642.

- ^ Eric Hughes; Jason Jordan; Terry Gullion (2001). "Structural Characterization of the [Cs(p-tert-butylcalix[4]arene -H) (MeCN)] Guest–Host System by 13C-133Cs REDOR NMR". Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 105 (25): 5887–5891. doi:10.1021/jp004559x.

- ^ Serkan Erdemir; Mufit Bahadir; Mustafa Yilmaz (2009). "Extraction of Carcinogenic Aromatic Amines from Aqueous Solution Using Calix[n]arene Derivatives as Carriers". Journal of Hazardous Materials. 168 (2–3): 1170–1176. Bibcode:2009JHzM..168.1170E. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.02.150. PMID 19345489.

- ^ Alcohol powder: Alcopops from a bag Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine, Westdeutsche Zeitung, 28 October 2004 (German)

- ^ Preparation of an Alcohol Containing Powder, General Foods Corporation March 31, 1972

Host–guest chemistry

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Principles

Host–guest chemistry is a branch of supramolecular chemistry that focuses on the formation of complexes between a host molecule, typically larger and featuring a cavity or binding site, and a guest molecule, which is smaller and binds within or to that site through non-covalent interactions.[13] This field explores how these molecular assemblies mimic biological recognition processes, enabling selective binding without the formation of covalent bonds.[14] The core principles revolve around molecular recognition, where the host and guest exhibit complementarity in size, shape, and chemical properties to achieve stable complexation. According to foundational work, the host is defined as an organic molecule or ion with convergent binding sites that envelop the guest, whose binding sites diverge upon complex formation, ensuring a precise fit akin to a lock and key.[13] This complementarity is driven by non-covalent forces, including hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions, van der Waals forces (encompassing dispersion and π-π stacking), and hydrophobic effects, which collectively provide the energetic basis for binding without permanent linkage.[14] For instance, a host like cyclodextrin can encapsulate a hydrophobic guest in aqueous solution primarily through hydrophobic interactions within its cavity.[15] Unlike covalent chemistry, host–guest interactions are reversible and dynamic, allowing guests to associate and dissociate under equilibrium conditions influenced by environmental factors such as solvent or temperature. This reversibility underpins the field's applications in areas like drug delivery and sensing, as the complexes can respond to stimuli without structural degradation.[16] In a basic schematic, the host is represented as a concave structure (e.g., a ring or bowl) that cradles the guest, with arrows indicating non-covalent bonds forming a stable yet transient supermolecule.[13]Historical Development

The roots of host–guest chemistry trace back to the 19th century with early observations of clathrate and inclusion compounds. In 1811, Humphry Davy reported the formation of chlorine hydrate, an early example of a clathrate where gas molecules are trapped within a water lattice, marking one of the first documented cases of non-covalent encapsulation.[17] Later, in 1891, Antoine Villiers isolated crystalline products from the bacterial degradation of starch, which he termed "cellulosine," later identified as cyclodextrins—the first known inclusion compounds capable of hosting guest molecules within their cavity. These discoveries laid the groundwork for understanding molecular inclusion, though their structural implications were not fully appreciated until the mid-20th century. The field advanced significantly in the mid-20th century with the development of terminology and systematic studies. In 1948, H. M. Powell coined the term "clathrate" to describe cage-like structures trapping guests, based on X-ray analyses of such compounds.[18] Friedrich Cramer furthered this in the 1950s by investigating cyclodextrin complexes, introducing the German terms "Wirt" (host) and "Gast" (guest) in his 1954 book Einschlussverbindungen, which formalized the concept of molecular recognition through non-covalent interactions.[18] By 1959, the host-guest metaphor entered English-language literature via Louis F. Fieser's textbook, bridging early inclusion chemistry to modern paradigms.[18] A pivotal milestone occurred in 1967 when Charles J. Pedersen discovered crown ethers while investigating the coordination chemistry of vanadium compounds using multidentate phenolic ligands at DuPont; his publication described dibenzo-18-crown-6 and its selective binding to alkali metal cations, inaugurating synthetic macrocyclic hosts.[6] The 1970s saw rapid expansion: C. David Gutsche revived calixarene chemistry in 1978, naming these phenol-based macrocycles and demonstrating their host properties after earlier isolations in the 1940s by A. Zinke.[19] Concurrently, Jean-Marie Lehn developed cryptands in the early 1970s, three-dimensional ligands for enhanced metal ion encapsulation, and coined "supramolecular chemistry" in 1978 to encompass such associative systems.[20] Donald J. Cram popularized the host-guest framework in 1973–1974, emphasizing preorganization for selective binding.[18] The 1987 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, awarded to Pedersen, Cram, and Lehn, recognized their pioneering work on structure-specific interactions, catalyzing the field's growth into molecular recognition and self-assembly. In the 1980s, studies on cyclodextrins and calixarenes intensified for practical applications, while cryptands advanced understanding of three-dimensional hosts. Post-2000 developments included refined syntheses of cucurbiturils, originally isolated in 1905 by R. Behrend but structurally elucidated and named by William L. Mock in 1981; these pumpkin-shaped macrocycles gained prominence for their rigid cavities and high-affinity guest binding, expanding host-guest paradigms.[21]Types of Complexes

Inclusion Compounds

Inclusion compounds represent a class of host-guest complexes in which linear or layered host molecules self-assemble to form extended channels or layers that accommodate guest molecules primarily through van der Waals or hydrophobic interactions, without providing complete enclosure around individual guests.[22] These structures are stabilized by the host lattice's hydrogen-bonding network, which creates open tunnels allowing guests to reside in a linear array along the channel axis.[23] Unlike cage-like arrangements, the channels in inclusion compounds permit potential guest mobility or exchange under certain conditions, though guests are typically trapped within the crystalline framework.[24] Classic examples include urea and thiourea inclusion compounds, where the hosts form hexagonal channel structures. In urea inclusion compounds, urea molecules hydrogen-bond into a rigid lattice of parallel, non-intersecting tunnels with a diameter of approximately 5.25 Å, suitable for linear guests such as n-alkanes or n-alkanones with 8-14 carbon atoms.[22][23] Thiourea, with its larger sulfur atom, generates wider channels (around 7-9 Å in diameter) that accommodate more bulky or branched guests, such as cyclohexane derivatives or tert-butyl-substituted aromatics.[24][25] Formation of these inclusion compounds typically occurs through crystallization-driven processes, where the host and guest are co-dissolved in a suitable solvent, and upon cooling or evaporation, the host self-assembles around the guest molecules to form the channel lattice.[23] This templating effect ensures that only compatible guests are incorporated, with common stoichiometries such as 1:1 or 2:1 host-to-guest ratios depending on the guest's length relative to the channel repeat unit; for instance, urea-alkane compounds often approximate a 7.3:1 urea-to-CH₂ ratio but are treated as stoichiometric for practical purposes.[22] In some cases, guest exchange can occur post-formation without disrupting the host framework, facilitated by the channel openness.[24] Key properties of inclusion compounds include well-defined stoichiometric ratios dictated by the channel dimensions and guest geometry, as well as pronounced guest selectivity based on molecular size and shape.[23] Urea channels, for example, selectively include linear hydrocarbons while excluding branched isomers that exceed the tunnel cross-section, enabling separation applications.[22] Thiourea exhibits complementary selectivity for spherical or puckered guests that fit its broader channels, highlighting how host architecture tunes inclusion specificity through van der Waals contacts and hydrophobic effects.[25] These features underscore the role of inclusion compounds in mimicking biological recognition processes at the molecular level.[24]Clathrate Compounds

Clathrate compounds represent a subclass of inclusion complexes in host-guest chemistry where host molecules self-assemble into rigid, polyhedral cage structures that trap guest molecules or atoms within discrete, enclosed voids, typically within a crystalline lattice, stabilized by non-covalent interactions such as van der Waals forces and hydrogen bonding rather than direct chemical bonds.[26] The term "clathrate," derived from the Latin clathratus meaning "provided with a lattice," was coined by H.M. Powell to describe these cage-like entrapments, distinguishing them from channel-type inclusions by their closed geometry that prevents guest diffusion without lattice disruption.[27] This structural motif allows selective encapsulation based on guest size and shape, with the host framework maintaining integrity across a range of guests, as exemplified in noble gas clathrates where smaller atoms like xenon occupy compact cages.[28] Classic organic clathrates include those formed by hydroquinone (β-quinol), which assembles via hydrogen-bonded networks into a body-centered tetragonal lattice containing 1/3 empty cages per unit cell, capable of trapping small guests such as sulfur dioxide or methanol; the structure was first elucidated by X-ray crystallography in 1948, revealing guests positioned at symmetry centers without host perturbation.[29] Similarly, Dianin's compound, a chiral chroman derivative synthesized in the early 20th century, forms isostructural clathrates with a hexagonal lattice of cage voids accommodating guests like ethanol or chloroform, with the host's phenolic hydroxyl groups enabling flexible hydrogen bonding; detailed crystallographic analysis in 1970 confirmed the cage dimensions and guest orientation, highlighting the compound's utility in resolving racemic mixtures through selective inclusion.[28] Water-based clathrates, known as gas hydrates, feature hydrogen-bonded water molecules forming polyhedral cages in cubic or hexagonal lattices, as in structure I (sI) hydrates with 46 water molecules per unit cell enclosing up to eight guests. The structural features of clathrates are governed by cage geometry and size, which dictate guest compatibility; for instance, in noble gas hydrates, small pentagonal dodecahedral (5¹²) cages (approximate radius 3.9 Å) suit xenon or krypton, while larger irregular cages (5¹²6² or 5¹²6⁴, radii up to 5.8 Å) accommodate hydrocarbons like methane or ethane, ensuring van der Waals stabilization without rattling in oversized voids.[30] This size selectivity arises from the host lattice's fixed dimensions, as seen in type II hydrates where 16 small and 8 large cages per 136 water molecules allow mixed occupancy, with smaller guests filling smaller voids to maximize lattice energy.[28] In organic clathrates like those of hydroquinone, the cages measure about 5-6 Å in diameter, fitting linear or spherical guests up to the size of benzene, with occupancy ratios often approaching 0.33 guests per host molecule.[29] Naturally occurring clathrates, particularly methane hydrates, are abundant in oceanic sediments and permafrost regions, where high pressure and low temperature stabilize water cages around methane molecules, forming vast deposits estimated to contain twice the global conventional natural gas reserves. These structures pose both opportunities and risks for energy storage, as controlled dissociation could release methane for fuel, though unintended release contributes to greenhouse gas emissions; their discovery in marine environments dates to the 1960s, with ongoing research emphasizing their role in sustainable energy transitions.[31]Encapsulated Complexes

Encapsulated complexes in host-guest chemistry involve the complete enclosure of a guest molecule within a host cavity, forming discrete molecular assemblies where the guest is fully surrounded and isolated from the bulk medium, often in solution or non-crystalline states.[32] This encapsulation contrasts with channel-like inclusions by providing a spherical, three-dimensional enclosure that restricts guest escape without covalent bond breakage in the case of carcerands or allows controlled exchange through portals in hemicarcerands.[33] Pioneering examples include carcerands and hemicarcerands developed by Donald J. Cram, where guests such as hydrocarbons with molecular weights exceeding 200 are permanently or semi-permanently trapped within covalent spherical hosts.[33] Carcerands form carceplexes during host synthesis, incarcerating solvent or reagent molecules that become guests unable to exit without host decomposition, while hemicarcerands feature gated portals enabling reversible guest exchange under thermal or other stimuli.[34] Additional examples encompass self-assembling supramolecular capsules, such as those formed by resorcinarenes or calixarenes linked via hydrogen bonding networks, which encapsulate neutral guests like fullerenes or small organics in organic solvents.[35] The formation of these complexes is driven primarily by entropy gains from desolvation, where solvent molecules released from both host cavity and guest surface increase overall disorder, complemented by the preorganization of the host structure that minimizes reorganization energy upon binding.[36] Hydrophobic effects further stabilize encapsulation in non-polar environments by favoring the exclusion of solvent from the cavity interior.[37] Effective encapsulation requires precise size matching between the guest's dimensions and the host cavity volume, ensuring optimal van der Waals contacts without excessive strain or void space; in Cram's hemicarcerands, cavities typically accommodate guests with effective diameters of approximately 0.5 to 1.0 nm, such as benzene derivatives or small alkanes.[38] This complementarity enhances binding selectivity, as mismatched guests experience constrictive or loose binding, reducing complex stability.[32]Host Architectures

Macrocyclic Hosts

Macrocyclic hosts are cyclic oligomers composed of 12 to 30 or more atoms that form internal cavities suitable for binding guest molecules or ions through non-covalent interactions.[39] These structures, often featuring heteroatoms like oxygen or nitrogen in the ring, enable encapsulation by providing a preorganized space that complements the guest's size and shape, as pioneered in early work on cyclic polyethers.[40] Unlike linear molecules, the cyclic topology restricts conformational freedom, enhancing binding efficiency in host-guest chemistry.[41] Design principles for macrocyclic hosts emphasize balancing rigidity and flexibility to optimize guest recognition. Rigid macrocycles, such as those with aromatic building blocks, maintain a fixed cavity shape for high selectivity, while flexible ones allow adaptive binding through conformational changes induced by substituents or environmental stimuli.[42] Cavity tuning is achieved by varying ring size, incorporating electron-donating or withdrawing groups, or modifying linkages to adjust polarity and depth, thereby tailoring affinity for specific guests like cations or neutral molecules.[41] This preorganization minimizes entropic penalties during complexation, a concept central to supramolecular design.[43] Synthesis of macrocyclic hosts typically involves template-directed methods or fragment coupling to overcome the entropic challenges of cyclization. Template-directed approaches use metal ions, such as alkali metals, to preorganize linear precursors into cyclic forms, as seen in the formation of ether-linked rings.[40] Fragment coupling strategies employ high-dilution conditions with reactions like Williamson ether synthesis for oxygen-containing motifs or phenolic condensations for aromatic systems, yielding cycles with 20-40% efficiency in optimized cases.[41] Common motifs include ether or phenolic linkages, which provide stability and solubility while allowing further functionalization.[42] The primary advantages of macrocyclic hosts lie in their high selectivity and binding strength due to preorganized cavities, which reduce the energy required for guest inclusion compared to acyclic analogs.[39] This leads to association constants often exceeding 10^4 M^{-1} for matched guests, enabling applications in molecular recognition and separation.[44] Additionally, their modular design facilitates scalability and modification for diverse uses, such as in sensing or catalysis, without compromising the core host-guest motif.[41]Crown Ethers and Cryptands

Crown ethers are macrocyclic polyethers characterized by a ring structure composed of ethylene oxide units, enabling them to selectively bind alkali and alkaline earth metal cations through coordination of their oxygen donor atoms to the positively charged guest. The nomenclature denotes the total number of atoms in the ring followed by the number of oxygen atoms, such as 18-crown-6, which features an 18-membered ring with six oxygen atoms and a cavity diameter of approximately 2.6–3.2 Å, ideally suited for potassium ions (K⁺) with an effective ionic diameter matching this size. This size complementarity arises from the preorganized cavity, where the cation fits snugly, maximizing electrostatic interactions while minimizing strain. Charles J. Pedersen first synthesized and characterized these compounds in 1967, reporting over 50 variants and their metal complexes, which demonstrated remarkable selectivity based on ring size and ion diameter.[45] The synthesis of crown ethers typically employs the Williamson etherification, an intramolecular SN2 reaction under high-dilution conditions to favor cyclization over polymerization. In this process, a diol or polyol alkoxide reacts with a dihalide or ditosylate, such as the reaction of hexaethylene glycol with 1,2-dibromoethane to form 18-crown-6. Pedersen's initial syntheses involved condensing catechol with diethylene glycol ditosylate in the presence of base, yielding dibenzo-substituted crowns like dibenzo-18-crown-6. Binding occurs via multiple oxygen-cation coordinations that displace the ion's solvation shell in solution, with additional stabilization in aromatic-substituted crowns from cation-π interactions between the metal and benzene rings. Selectivity is pronounced; for instance, 12-crown-4, with a smaller cavity of about 1.2–1.6 Å, preferentially binds lithium ions (Li⁺) over larger cations like Na⁺ or K⁺ due to optimal size matching and reduced desolvation penalty.[45][46][47] Cryptands represent the three-dimensional analogs of crown ethers, featuring bicyclic or tricyclic architectures with bridgehead nitrogen atoms connected by polyether chains, providing a cage-like enclosure for enhanced guest encapsulation. The notation [m.n.p] indicates the lengths of the three bridges in ethylene units; [2.2.2]-cryptand, synthesized by Jean-Marie Lehn in 1969, consists of three -CH₂CH₂O- chains linking two nitrogens, forming a spheroidal cavity complementary to K⁺. This topology yields higher binding affinities than monocyclic crowns, often by orders of magnitude, due to the wrap-around encapsulation that restricts ligand reorganization and provides additional entropy gain upon complexation. Lehn's design emphasized the topological control of cavity size for selectivity, with [2.2.2]-cryptand exhibiting particular affinity for K⁺ through complete ion solvation within the cavity.[48][49] In host-guest applications, crown ethers and cryptands facilitate phase-transfer catalysis by solubilizing inorganic salts in organic media, enabling reactions between aqueous anions and organic substrates without detailed mechanistic elaboration here.[50]Cyclodextrins and Cucurbiturils

Cyclodextrins are a family of cyclic oligosaccharides composed of D-glucopyranose units linked by α-1,4-glycosidic bonds, forming a toroidal structure with a hydrophobic interior cavity and a hydrophilic exterior surface due to hydroxyl groups.[51] The most common native cyclodextrins include α-cyclodextrin (six glucose units, cavity diameter ~4.7 Å), β-cyclodextrin (seven units, ~6.2 Å), and γ-cyclodextrin (eight units, ~7.8 Å), which enable selective inclusion of guest molecules based on size and hydrophobicity.[51] These compounds are naturally produced through the enzymatic action of cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase (CGTase, EC 2.4.1.19) on starch, where the enzyme catalyzes the cyclization of α-1,4-glucan chains to form the ring structures in a process involving transglycosylation reactions.[52] In host-guest chemistry, cyclodextrins act as hosts by encapsulating hydrophobic guests within their apolar cavity, driven primarily by the hydrophobic effect and van der Waals interactions, while the polar exterior enhances water solubility.[53] For instance, adamantane, a bulky hydrocarbon, forms a stable inclusion complex with β-cyclodextrin through hydrophobic binding, with association constants typically on the order of 10^4 to 10^5 M^{-1}, illustrating the preference for nonpolar guests that fit snugly within the cavity.[54] Cucurbiturils, in contrast, are synthetic macrocyclic hosts derived from the acid-catalyzed condensation of glycoluril with formaldehyde, yielding pumpkin-shaped molecules denoted as CB, where n represents the number of glycoluril units (commonly n=6, 7, or 8 for CB[55], CB[56], and CB[57], with cavity volumes increasing from ~142 ų to ~367 ų).[58] The synthesis, pioneered in modern form by Kimoon Kim and others in the 1980s and 1990s, involves heating glycoluril and paraformaldehyde in concentrated HCl, followed by purification, and has been optimized to produce homologues beyond the original CB[55].[58] Structurally, cucurbiturils feature a rigid hydrophobic cavity flanked by two carbonyl-lined portals that facilitate additional interactions. The binding in cucurbituril complexes relies on the hydrophobic effect within the cavity, augmented by strong ion-dipole interactions between cationic or polar guest moieties and the electron-rich carbonyl oxygens at the portals, which can contribute up to several kcal/mol to the stability.[59] This dual mechanism enables cucurbiturils to accommodate a wide range of guests, including neutral hydrophobes and charged species, with the portals acting as recognition sites for ammonium or metal ions. Compared to cyclodextrins, cucurbiturils exhibit significantly higher binding affinities for suitable guests, often by orders of magnitude; for example, derivatives of adamantane can achieve association constants up to 10^{15} M^{-1} with CB[56] due to optimized hydrophobic encapsulation combined with portal interactions, far surpassing the 10^4–10^5 M^{-1} typical for cyclodextrin-adamantane complexes.[58][60] This enhanced stability stems from the more rigid, symmetric structure of cucurbiturils and their polar portals, making them particularly effective for tightly bound host-guest pairs in aqueous media.Calixarenes

Calixarenes are macrocyclic compounds composed of phenol units connected by methylene bridges at the ortho and para positions, resulting in a cup-shaped or basket-like cavity that serves as a tunable host in supramolecular chemistry.[61] The most common variants are calixarenes where n ranges from 4 to 8, with calix[62]arene featuring four phenolic units forming a relatively rigid structure approximately 7 Å in depth.[61] These molecules exhibit conformational flexibility, adopting shapes such as the cone (where phenolic OH groups point in the same direction), partial cone, 1,2-alternate, or 1,3-alternate, which influence their host properties; the cone conformation is particularly favored for guest inclusion due to its preorganized cavity.[63] The upper rim, bearing the phenolic hydroxyl groups, and the lower rim, at the para positions, allow for extensive functionalization to modulate selectivity and solubility.[64] Synthesis of calixarenes typically involves base-catalyzed condensation of p-alkylphenols, such as p-tert-butylphenol, with formaldehyde or paraformaldehyde in a one-pot reaction, yielding cyclic oligomers in moderate to high yields depending on reaction conditions like temperature and catalyst.[61] This process, pioneered in the late 1970s, produces mixtures separable by chromatography, with the cyclization driven by the formation of methylene bridges between phenolic rings.[61] Post-synthesis modifications at the upper rim (e.g., etherification of OH groups) or lower rim (e.g., introduction of alkyl chains or crowns) enable the creation of derivatives tailored for specific host-guest interactions, enhancing stability and binding affinity.[63] In host-guest chemistry, calixarenes bind guests primarily through their hydrophobic aromatic cavity, utilizing non-covalent interactions such as π-π stacking for aromatic guests, hydrogen bonding at the rims, and electrostatic interactions for ions.[61] Cation binding often occurs at the lower rim, where phenolate oxygens coordinate metal ions, while the cavity accommodates neutral molecules or anions; for instance, calix[62]arene derivatives functionalized with crown ether bridges exhibit high selectivity for Cs⁺ over smaller alkali metals like Na⁺, with stability constants up to 10⁶ M⁻¹ attributed to optimal cavity size matching and enthalpic contributions from ion-dipole interactions.[63] Anionic guests can be encapsulated via upper-rim ammonium groups, and neutral organics like toluene bind via van der Waals forces within the cavity, demonstrating the versatility of calixarenes as receptors.[64] Key derivatives include thiacalixarenes, where sulfur atoms replace the methylene bridges, synthesized via similar condensation but using p-tert-butylphenol with sulfurizing agents like thiourea, yielding softer, more flexible structures with enhanced binding for soft metal ions due to sulfur's coordinative properties.[65] Resorcinarenes, formed by acid-catalyzed condensation of resorcinol with aldehydes like formaldehyde, feature eight hydroxyl groups (four phenolic and four from the resorcinol meta positions), creating a deeper cavity suited for larger guests and enabling hydrogen-bonded cavitands for inclusion of neutral molecules.[66] These derivatives expand the scope of calixarene-based hosts by introducing varied bridge chemistries and rim functionalities.[65]Pillararenes

Pillararenes are a class of synthetic macrocyclic hosts composed of hydroquinone units linked by methylene bridges at their para positions, forming rigid, pillar-like structures with a hydrophobic cavity lined by electron-rich aromatic rings. Introduced by Tomoki Ogoshi in 2008, pillararenes (n=5–15, commonly n=5 or 6) feature planar chirality in their symmetric architecture, with cavity sizes ranging from ~4.5 Å diameter for pillar[67]arene to larger for higher homologues, enabling selective binding of linear or cationic guests.[68] Synthesis typically involves acid-catalyzed condensation of 1,4-dialkoxybenzene with paraformaldehyde in solvents like chloroform, yielding cyclic oligomers separable by column chromatography, with pillar[67]arene often predominant under optimized conditions. Post-synthesis, the rims can be functionalized via Williamson etherification or click chemistry to introduce solubilizing groups or binding motifs.[68] In host-guest chemistry, pillararenes bind guests through hydrophobic and π-π interactions within the cavity, with particular affinity for neutral alkanes, alkylammonium ions, or viologen derivatives, exhibiting association constants up to 10^5 M^{-1} in aqueous or organic media. Their unique symmetry allows for 1:1 or 1:2 complexation modes, and chirality enables enantioselective recognition when using planar chiral derivatives. Pillararenes' versatility extends to supramolecular polymers and assemblies, complementing other macrocyclic hosts.[68]Cryptophanes

Cryptophanes represent a prominent class of rigid, spherical host molecules in host–guest chemistry, designed to encapsulate small neutral guests within their enclosed hydrophobic cavities. These cage-like structures are typically constructed from two cyclotriveratrylene (CTV) units—bowl-shaped macrocycles derived from three veratrole units—linked by three flexible alkyl chains, such as ethylene bridges in the archetypal cryptophane-A. This dimeric architecture yields a compact, aromatic-lined cavity with a diameter of approximately 0.4–0.6 nm, enabling selective inclusion of guests like noble gases and small halocarbons while excluding larger species due to steric constraints.[69] The rigidity of the CTV caps imparts stability to the host, distinguishing cryptophanes from more open aromatic macrocycles like calixarenes by providing a fully enclosed environment that enhances binding specificity.[70] The synthesis of cryptophanes has evolved from early template-directed approaches to more versatile fragment coupling strategies, allowing precise control over cavity size and functionality. The first cryptophane, cryptophane-A, was synthesized in 1981 by linking two CTV units via a template-assisted cyclization in the presence of a guest molecule, achieving low yields but demonstrating the feasibility of cage formation. Contemporary methods employ SN2-mediated coupling of tri-substituted CTV fragments, often using catalysts like Sc(OTf)3, to construct cryptophanes in 5–13 steps with overall yields up to 18% for derivatives like cryptophane-111.[70] Chirality plays a key role, as CTV units can adopt P or M helical configurations; enantiopure cryptophanes are obtained via resolution with chiral auxiliaries like (S)-Mosher's acid or chiral HPLC, enabling enantioselective guest recognition in chiral environments.[69] Binding in cryptophanes relies on non-covalent interactions tailored to the guest, with cryptophane-A exemplifying high selectivity for xenon through dispersion and van der Waals forces, yielding association constants around 3900 M⁻¹ at 278 K in 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane-d₂. For chloroform, encapsulation is driven by CH–π interactions between the guest's C–H bonds and the host's aromatic walls, resulting in binding constants up to 10³ M⁻¹ and pronounced upfield shifts in ¹H NMR spectra.[69] This selectivity arises from the cavity's size complementarity, as larger or smaller guests exhibit weaker affinities; for instance, cryptophane-A prefers Xe over Kr by factors exceeding 10 due to optimal fit.[69] A defining property of cryptophane complexes is the high kinetic barrier to guest exchange, stemming from the rigid framework that necessitates conformational changes or portal gating for entry and exit. Energy barriers typically range from 10–20 kcal/mol, rendering exchange slow on the NMR timescale (seconds to minutes at room temperature) and allowing observation of distinct host–guest signals.[69] This kinetic stability enhances applications in sensing, where persistent encapsulation maintains signal integrity, though it can limit reversibility compared to more flexible hosts.[69]Polymeric Hosts

Polymeric hosts in host–guest chemistry consist of linear chains or crosslinked networks derived from macrocyclic or binding-site-containing monomers, enabling the inclusion of guest molecules along extended structures rather than discrete cavities. These polymers extend the principles of macrocyclic hosts by providing multiple binding sites in a one- or two-dimensional array, facilitating cooperative interactions and higher guest capacities. Unlike finite macrocycles, polymeric hosts offer scalability and processability for practical applications. Cyclodextrin-based polymers represent a prominent class, where β-cyclodextrin (β-CD) units are incorporated into polymer backbones or networks to form inclusion hosts. For instance, crosslinked β-CD polymers, synthesized via nucleophilic substitution or condensation reactions, exhibit channel-like pores that accommodate hydrophobic guests such as adamantane derivatives.[71] Pillararene-based polymers, another key type, leverage the rigid, electron-rich cavities of pillararenes (n=5–10) copolymerized with vinyl or alkyne monomers to create linear or networked structures capable of binding neutral or cationic guests through π–π and charge-transfer interactions.[72] Channel-forming polymers, such as those based on polyurethanes incorporating cyclodextrin units, generate tubular voids via hydrogen-bonding motifs in the polymer backbone, allowing selective transport and inclusion of linear guests like alkyl chains.[73] Synthesis of polymeric hosts typically involves polymerization of pre-functionalized macrocycles, such as azide- or alkene-modified cyclodextrins linked via copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC "click" chemistry), yielding well-defined copolymers with tunable cyclodextrin density.[74] Alternatively, copolymerization integrates binding sites directly, as in the radical polymerization of pillararene-acrylate monomers to form side-chain polymers with multiple host units per repeat.[75] These methods allow control over molecular weight and crosslinking degree, ensuring solubility or gelation as needed. Binding in polymeric hosts often features cooperative effects from adjacent sites, enhancing affinity beyond monomeric analogs; for example, in pseudopolyrotaxanes, α-cyclodextrin rings thread onto poly(ethylene glycol) chains, forming linear assemblies with binding constants up to 10^5 M^{-1} per unit due to multivalent interactions that stabilize the threaded structure.[76] Such assemblies demonstrate sliding or dethreading dynamics, influenced by guest size and solvent, enabling reversible encapsulation.[77] The advantages of polymeric hosts include enhanced mechanical and thermal stability from the extended backbone, which resists dissociation under stress compared to discrete complexes, and tunable porosity through monomer ratios or crosslinking, allowing guest selectivity based on size or hydrophobicity.[71] These properties make them suitable for scalable host–guest systems with improved recyclability.Cages and Frameworks

In host-guest chemistry, molecular cages represent discrete three-dimensional architectures designed to encapsulate guest molecules within confined cavities. Self-assembled coordination cages, typically formed through metal-ligand interactions, provide tunable pores for selective guest binding. For instance, these cages often employ square-planar or octahedral metal ions with bridging ligands to yield structures like M₂L₄ polyhedra, enabling encapsulation of aromatic or polar guests via hydrophobic or hydrogen-bonding interactions.[78] Carcerands, introduced by Cram in the late 1980s, are covalent spherical hosts that permanently incarcerate guests during synthesis, forming carceplexes where escape requires host bond breakage, thus offering irreversible entrapment for reactive species.[79] These cages exhibit constrictive binding, where the cavity size modulates guest affinity, as seen in hemicarcerands that allow partial guest exposure for controlled reactivity.[32] Extended frameworks expand host-guest interactions to porous networks, with metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) and covalent organic frameworks (COFs) serving as prominent examples. MOFs, constructed from metal nodes and organic linkers, feature high surface areas often exceeding 7000 m²/g, facilitating adsorption and exchange of gases or solvents within their micropores.[80] Guest molecules interact via coordination to open metal sites or π-π stacking with linkers, enabling applications in storage and separation. COFs, linked by strong covalent bonds between organic building units, provide crystalline pores with uniform sizes (typically 0.5–5 nm) for precise host-guest matching, such as anion binding or molecular sieving, while maintaining thermal stability up to 500°C.[81] In both systems, dynamic guest exchange occurs through diffusion or breathing modes, where framework flexibility accommodates varying guest loads without structural collapse.[82] Recent advances since 2020 have focused on metal-organic polyhedra (MOPs), finite analogs of MOFs, for enhanced selectivity in gas binding. For example, Zr-based MOPs with tailored hydrophobic pockets achieve CO₂/CH₄ selectivities over 100 via van der Waals interactions in confined spaces, as determined by in situ diffraction and DFT calculations.[83] Dynamic coordination cages have also emerged, incorporating stimuli-responsive ligands for reversible guest release; palladium-based systems, for instance, enable pH- or light-triggered dissociation, expanding utility in adaptive host-guest systems.[84] As of 2025, further developments include conformationally adaptable pseudo-cubic cages that dynamically adjust cavity volume to accommodate guests of varying sizes, and coordination cages equipped with frustrated Lewis pairs for controlled guest uptake and reactivity.[85][86] These developments underscore the versatility of cages and frameworks in achieving size- and shape-selective encapsulation, distinct from polymeric hosts by their well-defined, finite geometries.[87]Interaction Mechanisms

Thermodynamic Principles

The stability of host–guest complexes is quantified by the association constant , defined as , where [HG], [H], and [G] are the equilibrium concentrations of the complex, free host, and free guest, respectively; has units of M⁻¹ and reflects the equilibrium position of the binding process. The Gibbs free energy change for binding is related to by the equation , where is the gas constant and is the absolute temperature; thus, more negative values correspond to stronger binding affinities, typically ranging from -5 to -14 kcal mol⁻¹ at 298 K for common host–guest systems in aqueous media. The thermodynamic favorability of binding arises from contributions to both enthalpy () and entropy (), as . Enthalpic gains () stem primarily from specific interactions such as hydrogen bonding, electrostatic attractions, and van der Waals forces between host and guest, often dominating in polar solvents like water where values can reach -21 kcal mol⁻¹. Entropic contributions () are frequently driven by desolvation effects, where the release of ordered solvent molecules around hydrophobic surfaces increases overall disorder, though conformational restrictions in the host or guest can impose unfavorable entropy penalties; net -T terms at 298 K typically span -2 to +8 kcal mol⁻¹. The chelate effect enhances binding stability through multi-dentate interactions, where multiple binding sites on the host engage the guest simultaneously, increasing enthalpic contributions from additional non-covalent bonds while minimizing entropy loss compared to monodentate equivalents; this is particularly pronounced in macrocyclic hosts, leading to stability gains analogous to coordination chemistry.[88] Preorganization, as conceptualized by Cram, refers to the pre-arrangement of binding sites in the host to match the guest's geometry, reducing the energetic cost of reorganization upon complexation and thereby amplifying affinity by up to several orders of magnitude in ; for instance, spherands exhibit near-perfect preorganization for alkali metal ions.[13] In multi-site binding, positive cooperativity arises when initial guest binding facilitates subsequent interactions, quantified by successive association constants where , often due to induced-fit adjustments that enhance secondary contacts and yield improvements of 5–10 kcal mol⁻¹ per additional site.[89] Solvent effects significantly modulate stability, with polar protic solvents like water promoting binding via hydrophobic desolvation but weakening electrostatic interactions through dielectric screening; in non-polar media, van der Waals and -stacking forces dominate. Temperature dependence reveals that remains relatively constant over 278–328 K due to enthalpy-entropy compensation, but negative heat capacity changes ( to -150 cal mol⁻¹ K⁻¹) arise from solvent reorganization, making binding more enthalpically favorable at higher temperatures while often reducing overall affinity as decreases with rising .Kinetic Aspects

In host-guest chemistry, the kinetic aspects govern the dynamic processes of complex formation and disassembly, characterized by the association rate constant and dissociation rate constant , where the equilibrium association constant relates to these as . Association often proceeds via diffusion-controlled mechanisms, with typically on the order of to M s in aqueous environments, reflecting the encounter rate limited by molecular diffusion rather than intrinsic chemical barriers. Dissociation rates vary widely, from rapid (seconds) for loosely bound guests to exceedingly slow (hours or longer) for tightly encapsulated ones, enabling applications in controlled release systems. Binding mechanisms frequently involve energy barriers arising from host architecture, such as constrictive portals that impose steric constraints on guest ingress or egress. In cucurbiturils, portal gating exemplifies this: the narrow, carbonyl-lined portals create a high activation barrier for guest entry, often exceeding 20 kcal/mol, leading to constrictive binding where desolvation and ion-dipole interactions at the portal precede cavity inclusion.[90] This gating mechanism slows kinetics compared to open hosts like cyclodextrins, with values as low as 10 s for certain ammonium guests, tunable by cation competition at the portals. Diffusion-controlled limits apply primarily to initial encounter, but subsequent steps like portal passage introduce selectivity and rate modulation. Several factors influence these rates, including host conformational changes that must occur for guest accommodation, such as ring inversion in calixarenes or cage breathing in cryptophanes, which can elevate activation energies by 5–15 kcal/mol.[91] Solvent viscosity also plays a role; in viscous media, diffusion-controlled decreases proportionally, as seen in cyclodextrin-guest systems where rates scale inversely with bulk viscosity. A notable example is the slow release of xenon from cryptophanes, where exchange dynamics are hindered by portal constriction and water clustering, yielding on the order of 10 s or slower in aqueous solution, far below diffusion limits.[92] In dynamic host-guest systems, allosteric effects introduce responsive kinetics, where binding of one guest modulates the rate of a second binding event through conformational propagation. For instance, in γ-cyclodextrin-hosted bimetallic complexes, guest inclusion induces a U-shaped conformation that accelerates subsequent substrate binding by over 30-fold, with effective rate enhancements tied to allosteric rigidification.[93] Such effects enable kinetic control in multi-component assemblies, contrasting equilibrium-driven selectivity by favoring pathway-dependent outcomes over thermodynamic minima.Characterization Techniques