Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

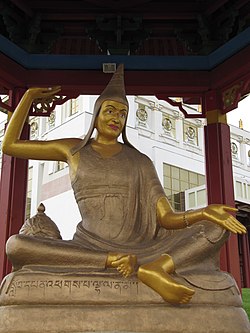

Aryadeva

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

Āryadeva (fl. 3rd century CE) (IAST: Āryadeva; Tibetan: འཕགས་པ་ལྷ་, Wylie: 'phags pa lha, Chinese: 提婆 菩薩 Tipo pusa meaning Deva Bodhisattva), was a Mahayana Buddhist monk, a disciple of Nagarjuna and a Madhyamaka philosopher.[1] Most sources agree that he was from "Siṃhala", which some scholars identify with Sri Lanka.[1] After Nagarjuna, he is considered to be the next most important figure of the Indian Madhyamaka school.[2][3]

Āryadeva's writings are important sources of Madhyamaka in East Asian Buddhism. His Catuḥśataka (Four Hundred Verses) was influential on Madhyamaka in India and China and his *Śataka (Bailun, 百論, T. 1569) and Dvādaśamukhaśāstra (both translated by Kumārajīva in the 4th century) were important sources for the East Asian Madhyamaka school.[1] Āryadeva is also known as Kanadeva, recognized as the 15th patriarch in Chan Buddhism and some Sinhalese sources also mention an elder (thera) called Deva which may also be the same person.[1] He is known for his association with the Nalanda monastery in modern-day Bihar, India.[4]

Biography

[edit]

The earliest biographical sources on Aryadeva state that he was a Buddhist monk who became a student of Nagarjuna and was skilled in debate.[3][2]

According to Karen Lang:

The earliest information we have about the life of Aryadeva occurs in the hagiography translated into Chinese by the Central Asian monk Kumarajiva (344–413 c.e.). It tells us that he was born into a Brahmin family in south India and became the spiritual son of Nagarjuna. Aryadeva became so skilled in debate that he could defeat all his opponents and convert them to Buddhism. One defeated teacher’s student sought him out and murdered him in the forest where he had retired to write. The dying Aryadeva forgave him and converted him to Buddhism with an eloquent discourse on suffering.[5]

Lang also discusses Xuanzang's (7th century) writings which mention Aryadeva:

He reports that Aryadeva came to south India from the island of Simhala because of his compassion for the ignorant people of India. He met the aging Nagarjuna at his residence on Black Bee Mountain, located southwest of the Satavahana capital, and became his most gifted student. Nagarjuna helped Aryadeva prepare for debate against Brahmanical teachers who had defeated Buddhist monks in the northeastern city of Vaisali for the previous twelve years. Aryadeva went to Vaisali and defeated all his opponents in less than an hour.[5]

Tom Tillemans also notes that Aryadeva's origins in Siṃhaladvīpa (Sri Lanka) are supported by his commentator Candrakīrti (sixth century C.E.), and "may possibly be confirmed by references in the Ceylonese chronicles Dīpavaṃsa and Mahāvaṃsa to a “Deva” who lived in the second half of the third century at the time when the Indian Vetullavāda sect of Great Vehicle Buddhism was temporarily implanted in Śrī Laṅka."[6]

Works

[edit]Most of Āryadeva's works were not preserved in the original Sanskrit but mainly in Tibetan and Chinese translations.

Four Hundred Verses

[edit]The Catuḥśataka śāstra kārikā (the Four Hundred Verse Treatise) is Āryadeva's main work. It is available in fragmentary Sanskrit, in Xuanzang's Chinese translation of the second part only, and in a full Tibetan translation.[7]

It is a work of sixteen chapters. David Seyfort Ruegg outlines the content as follows:

(i—iv) Elimination of the erroneous positing of things as permanent (nitya), pleasant (sukha), pure (asubha or suci), and self (atman) (according to Candrakirti these four chapters which dispel the four viparyasas explain the nature of mundane things so that they may be abandoned and buddhahood may be achieved), (v) The Bodhisattva's practice (which makes it practically possible to achieve Buddhahood). (vi) Elimination of the defilements (klesa) which hinder the preceding, (vii) Elimination of attachment to the enjoyment of seemingly desirable sensory objects (visaya), which causes the defilements to arise and increase. And (viii) the practice of the disciple. The first eight chapters of the Catuḥśataka are thus concerned with the preparation of those who practise the path. The last eight chapters then explain the non-substantiality of the dharmas. They deal in turn with the negation (pratisedha) of (ix) permanent entities, (x) self (atman), (xi) time, (xii) dogmatic opinions (drsti), (xiii) sense-faculties and their objects, (xiv) the positing of doctrinal extremes (antagraha, e.g. existence, non-existence, both, and neither) with special reference to identity and difference, and (xv) the positing of conditioned (samskrta) things as real. Finally chapter xvi, entitled 'An exposition of the cultivation of ascertainment for master and disciple', is devoted to a consideration of logical and epistemological problems in the doctrine of sunyata. In particular, it is pointed out (in conformity with Vigrahavyavartani 29—30) that he who does not maintain a thesis (paksa) based on the positions of existence (sat), non-existence (asat), and both cannot be attacked in logic by an opponent (xvi. 25).[8]

There also exists a complete commentary to this text by Chandrakirti which is only extant in Tibetan.[9]

Xuanzang also translated Dharmapāla’s commentary to verses 201–400 of the Catuḥśataka, published as Dasheng Guang bailun shi lun (大乘廣百論釋論, T. 1571).[1]

Other attributed texts

[edit]Two other texts which are attributed to Āryadeva in the Chinese tradition (but not the Tibetan) are the following:

- Śataśāstra (Bailun, 百論, Treatise in One Hundred Verses, Taisho 1569), which only survives in Kumarajiva's Chinese translation. However, according to Ruegg, the attribution of this work to Aryadeva is uncertain.[10] This text also comes with a commentary by an author known as Vasu (婆藪).[1] This text is closely connected to the Catuḥśataka.

- Akṣaraśataka (Baizi lun, 百字論, One Hundred Syllables, T. 1572) and its Vritti is sometimes attributed to Nagarjuna in the Tibetan tradition, but the Chinese tradition attributes this to Āryadeva.[11]

Possible wrong attributions

[edit]Chinese sources attribute a commentary to Nagarjuna's Madhyamakasastra ascribed to a "Pin-lo-chieh" ("Pingala") as being a work of Āryadeva. But this attribution has been questioned by some scholars according to Ruegg.[2]

Vincent Eltschinger also notes three other texts in the Chinese canon which are attributed to Āryadeva, but these attributions are dubious according to Eltschinger:[1]

- *Mahāpuruṣaśāstra, Dazhangfu lun (大丈夫論, T. 1577)

- Tipo pusa po Lengqie jing zhong waidao xiaosheng sizong lun (Treatise on the Refutation of Heterodox and Hīnayāna Theses in the Laṅkāvatārasūtra 提婆菩薩破楞伽經中外道小乘四宗論, T. 1639)

- Tipo pusa shi Lengqie jing zhong waidao xiaosheng niepan lun (Treatise on the Explanation of Nirvāṇa by Heterodox and Hīnayāna Teachers in the Laṅkāvatārasūtra 提婆菩薩釋楞伽經中外道小乘涅槃論 T. 1640)

The Hastavalaprakarana (Hair in the Hand) is attributed to Dignaga in the Chinese tradition and to Āryadeva in the Tibetan tradition. Modern scholars like Frauwallner, Hattori and Ruegg argue that it is likely by Dignaga.[11][1]

According to Ruegg "the bsTan'gyur also contains two very short works attributed to Aryadeva, the *Skhalitapramathanayuktihetusiddhi and the *Madhyamakabhramaghata".[12]

Tillemans writes that while Tibetans attribute the Destruction of Errors about Madhyamaka (*madhyamakabhramaghāta), "this text copiously borrows from the Verses on the Heart of Madhyamaka (madhyamakahṛdayakārikā) and Torch of Dialectics (tarkajvālā) of Bhāviveka, a celebrated Mādhyamika who lived in the sixth century (i.e., 500-570 C.E.)" and thus cannot be Aryadeva's.[6]

The Tantric Āryadeva

[edit]Several important works of esoteric Buddhism (most notably the Caryamelapakapradipa or "Lamp that Integrates the Practices" and the Jñanasarasamuccaya) are attributed to Āryadeva. Contemporary research suggests that these works are datable to a significantly later period in Buddhist history (late ninth or early tenth century) and they are seen as being part of a Vajrayana Madhyamaka tradition which included a later tantric author also named Āryadeva.[13] Tillemans also notes that the Compendium on the Essence of Knowledge (jñānasārasamuccaya) "gives the fourfold presentation of Buddhist doctrine typical of the doxographical (siddhānta) literature, a genre which considerably post-dates the third century".[6]

Traditional historians (for example, the 17th century Tibetan Tāranātha), aware of the chronological difficulties involved, account for the anachronism via a variety of theories, such as the propagation of later writings via mystical revelation. A useful summary of this tradition, its literature, and historiography may be found in Wedemeyer 2007.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Silk, Jonathan A. (ed.) (2019). Brill’s Encyclopedia of Buddhism Volume II:Lives, pp. 60-68. Brill.

- ^ a b c Ruegg (1981), p. 50.

- ^ a b Women of Wisdom by Tsultrim Allione, Shambhala Publications Inc, p. 186.

- ^ Niraj Kumar; George van Driem; Phunchok Stobdan (18 November 2020). Himalayan Bridge. KW. p. 253. ISBN 978-1-00-021549-6.

- ^ a b Lang, Karen C. (2003). Four Illusions: Candrakīrti's Advice for Travelers on the Bodhisattva Path, p. 9. Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b c Tillemans, Tom. Āryadeva, appearing in The Routledge Handbook of Indian Buddhist Philosophy, ed. by William Edelglass, Sara McClintock and Pierre-Julien Harter.

- ^ Ruegg (1981), p. 51.

- ^ Ruegg (1981), p. 52.

- ^ Ruegg (1981), p. 52.

- ^ Ruegg (1981), pp. 50-51.

- ^ a b Ruegg (1981), p. 53.

- ^ Ruegg (1981), p. 54.

- ^ Ruegg (1981), p. 54.

Bibliography

[edit]- Ruegg, David Seyfort (1981), ''The Literature of the Madhyamaka School of Philosophy in India,'' Otto Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Ruth Sonam (tr.), Āryadeva's Four Hundred Stanzas on the Middle Way: with Commentary by Gyel-tsap—Additional Commentary by Geshe Sonam Rinchen ISBN 9781559393027.

- Lang, Karen (1986). Aryadeva's Catuhsataka: On the Bodhisattva's Cultivation of Merit and Knowledge. Narayana Press, Copenhagen.

- Wedemeyer, Christian K. (2007). Aryadeva's Lamp that Integrates the Practices: The Gradual Path of Vajrayana Buddhism according to the Esoteric Community Noble Tradition. New York: AIBS/Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-9753734-5-3

- Wedemeyer, Christian K. (2005). 25117/http://www.lib.uchicago.edu/e-reserves/regenstein/timp/557-5114pt1.pdf Aryadeva's Lamp that Integrates the Practices: The Gradual Path of Vajrayana Buddhism according to the Esoteric Community Noble Tradition, part II: annotated English translation, University of Chicago

- Young, Stuart H. (2015). Conceiving the Indian Buddhist Patriarchs in China, Honolulu : University of Hawaiʻi Press, pp. 265-282

External links

[edit]- Aryadeva - "Els quatre-cents versos" (En català) Archived 12 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine