Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Shechita

View on Wikipedia

This article contains one or more duplicated citations. The reason given is: DuplicateReferences detected: (May 2025) |

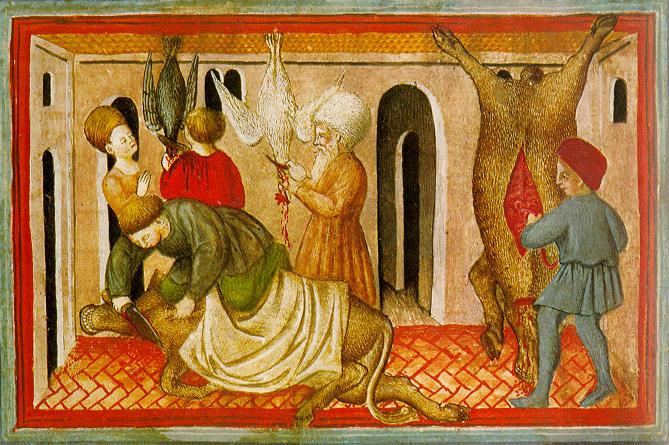

A 15th-century depiction of shechita and bedikah | |

| Halakhic texts relating to this article | |

|---|---|

| Torah: | Deuteronomy 12:21, Deuteronomy 14:21, Numbers 11:22 |

| Mishnah: | Hullin |

| Babylonian Talmud: | Hullin |

| Mishneh Torah: | Sefer Kodashim, Hilchot shechita |

| Shulchan Aruch: | Yoreh De'ah 1:27 |

| Other rabbinic codes: | Sefer ha-Chinuch mitzvah 451 |

In Judaism, shechita (anglicized: /ʃəxiːˈtɑː/; Hebrew: שחיטה; [ʃχiˈta]; also transliterated shehitah, shechitah, shehita) is ritual slaughtering of certain mammals and birds for food according to kashrut. One who practices this, a kosher butcher is called a shochet.

Biblical sources

[edit]Deuteronomy 12:21 states that sheep and cattle should be slaughtered "as I have instructed you",[1] but nowhere in the Torah are any of the practices of shechita described.[2] Instead, they have been handed down in Rabbinic Judaism's Oral Torah, and codified in halakha.

Species

[edit]The animal must be of a permitted species. For mammals, this is restricted to ruminants which have split hooves.[3] For birds, although biblically any species of bird not specifically excluded in Deuteronomy 14:12–18 would be permitted,[4][5] doubts as to the identity and scope of the species on the biblical list led to rabbinical law permitting only birds with a tradition of being permissible.[6]

Fish do not require kosher slaughter to be considered kosher, but are subject to other laws found in Leviticus 11:9-12, which determine whether or not they are kosher (having both fins and scales).[7]

Shochet

[edit]A shochet (שוחט, "slaughterer", plural shochtim) is a person who performs shechita. To become a shochet, one must study which slaughtered animals are kosher, what disqualifies them from being kosher, and how to prepare animals according to the laws of shechita. Subjects of study include the preparation of slaughtering tools, ways to interpret which foods follow the laws of shechita, and types of terefot (deformities which make an animal non-kosher).[2]

In the Talmudic era (beginning in 200 CE with the Jerusalem Talmud and 300 CE with the Babylonian Talmud and extending through the Middle Ages), rabbis started to debate and define kosher laws. As the laws increased in number and complexity, following ritual slaughter laws became difficult for Jews who were not trained in those laws. This resulted in the need for a shochet (someone who has studied shechita extensively) to perform the slaughtering in the communities.[2] Shochtim studied under rabbis to learn the laws of shechita. Rabbis acted as the academics who, among themselves, debated how to apply laws from the Torah to the preparation of animals. Rabbis also conducted experiments to determine under which terefot animals were no longer kosher. Shochtim studied under these rabbis, as rabbis were the officials who first interpret, debate, and determine the laws of shechita.[2]

Shochtim are essential to every Jewish community, so they earn elevated social status. In the Middle Ages, the shochtim were treated as second in social status, just underneath rabbis. Shochtim were respected for committing their time to studying and for their importance to their communities.[2]

An inspection (Heb. bedikah) of the animal is required for it to be declared kosher, and a shochet has a double title: Shochet u'bodek (slaughterer and inspector), for which qualification considerable study as well as practical training is required.[citation needed]

Procedure

[edit]

The shechita procedure, which must be performed by a shochet, is described in the Yoreh De'ah section of the Shulchan Aruch only as severing the wind pipe and food pipe (trachea and esophagus). Nothing is mentioned about veins or arteries.

However, in practice, as a very long sharp knife is used, in cattle the soft tissues in the neck are sliced through without the knife touching the spinal cord, in the course of which four major blood vessels, two of which transport oxygenated blood to the brain (the carotid arteries) the other two transporting blood back to the heart (jugular veins) are severed. The vagus nerve is also cut in this operation. With fowl, the same procedure is followed, but a smaller knife is used.[citation needed]

A special knife of considerable length is used; no undue pressure may be applied to the knife, which must be very sharp.[8][9] The procedure may be performed with the animal either lying on its back (שחיטה מונחת, shechita munachat) or standing (שחיטה מעומדת, shechita me'umedet).[10]

In the case of fowl (with the exception of large fowl like turkey) the bird is held in the non-dominant hand in such a way that the head is pulled back and the neck exposed, while the cut made with the dominant hand.[11]

The procedure is done with the intention of causing a rapid drop in blood pressure in the brain and loss of consciousness, to render the animal insensitive to pain and to exsanguinate in a prompt and precise action.[12]

It has been suggested that eliminating blood flow through the carotid arteries does not cut blood flow to the brain of a bovine because the brain is also supplied with blood by vertebral arteries,[13] but other authorities note the distinction between severing the carotid versus merely blocking it.[12]

If one did not sever the entirety of both the trachea and esophagus then an animal may still be considered kosher as long as one severed the majority of the trachea and esophagus (windpipe and food pipe) of a mammal, or the majority of either one of these in the case of birds.[8] The cut must be incised with a back-and-forth motion without employing any of the five major prohibited techniques,[14] or various other detailed rules.

Forbidden techniques

[edit]- Shehiyah (שהייה; delay or pausing) – Pausing during the incision and then starting to cut again makes the animal's flesh unkosher.[15] The knife must be moved across the neck in an uninterrupted motion until the trachea and esophagus are sufficiently severed to avoid this.[8] There is some disagreement among legal sources as to the exact length of time needed to constitute shehiyah, but today the normative practice is to disqualify a kosher cut as a result of any length of pausing.[16]

- Derasah (דרסה; pressing/chopping) – The knife must be drawn across the throat by a back and forth movement, not by chopping, hacking, or pressing without moving the knife back and forth.[17] There are those[18] who assert that it is forbidden to have the animal in an upright position during shechita due to the prohibition of derasah. They maintain that the animal must be on its back or lying on its side, and some also allow for the animal to be suspended upside down.[19] However, the Rambam explicitly permits upright slaughter,[10] and the Orthodox Union as well as all other major kosher certifiers in the United States accept upright slaughter.[20]

- Haladah (חלדה; covering, digging, or burying) – The knife must be drawn over the throat so that the back of the knife is at all times visible while shechita is being performed. It must not be stabbed into the neck or buried by fur, hide, feathers, the wound itself, or a foreign object (such as a scarf) which may cover the knife.[21]

- Hagramah (הגרמה; cutting in the wrong location) – Hagramah refers to the location on the neck on which a kosher cut may be performed; cutting outside this location will in most cases disqualify a kosher cut.[22] According to today's normative Orthodox practice, any cutting outside this area will in all cases disqualify a kosher cut.[22] The limits within which the knife may be applied are from the large ring in the windpipe to the top of the upper lobe of the lung when it is inflated, and corresponding to the length of the pharynx. Slaughtering above or below these limits renders the meat non-kosher.

- Iqqur (עיקור; tearing) – If either the esophagus or the trachea is torn during the shechita incision, the carcass is rendered non-kosher. Iqqur can occur if one tears out the esophagus or trachea while handling an animal's neck or if the esophagus or trachea is torn by a knife with imperfections on the blade, such as nicks or serration.[23][24][25] In order to avoid tearing, the kosher slaughter knife is expertly maintained and regularly checked with the shochet's fingernail to ensure that no nicks are present.[26]

Breaching any of these five rules renders the animal nevelah; the animal is regarded in Jewish law as if it were carrion.[27]

Temple Grandin has observed that "if the rules (of the five forbidden techniques) are disobeyed, the animal will struggle. If these rules are obeyed, the animal has little reaction."[24]

The knife

[edit]

The knife used for shechita is called a sakin (סכין), or alternatively a chalaf (חלף)[29] by Ashkenazi Jews. By biblical law the knife may be made from anything not attached directly or indirectly to the ground and capable of being sharpened and polished to the necessary level of sharpness and smoothness required for shechita.[30][31] The tradition nowadays is to use a very sharp metal knife.[32]

The knife must be at least slightly longer than the neck width but preferably at least twice as long as the animal's neck is wide, but not so long that the weight of the knife is deemed excessive. If the knife is too large, it is assumed to cause derasah, excessive pressing. Kosher knife makers sell knives of differing sizes depending on the animal. Shorter blades may technically be used depending on the number of strokes employed to slaughter the animal, but the normative practice today is that shorter blades are not used. The knife must not have a point. It is feared a point may slip into the wound during slaughter and cause haladah, covering, of the blade. The blade may also not be serrated, as serrations cause iqqur, tearing.[33]

The blade cannot have imperfections in it. All blades are assumed by Jewish law to be imperfect, so the knife must be checked before each session. In the past the knife was checked through a variety of means. Today the common practice is for the shochet to run their fingernail up and down both sides of the blade and on the cutting edge to determine if they can feel any imperfections. They then use a number of increasingly fine abrasive stones to sharpen and polish the blade until it is perfectly sharp and smooth.[citation needed]

After the slaughter, the shochet must check the knife again in the same way to be certain the first inspection was properly done, and to ensure the blade was not damaged during shechita. If the blade is found to be damaged, the meat may not be eaten by Jews. If the blade falls or is lost before the second check is done, the first inspection is relied on and the meat is permitted.[citation needed]

In previous centuries, the chalaf was made of forged steel, which was not reflective and was difficult to make both smooth and sharp. Shneur Zalman of Liadi, fearing that Sabbateans were scratching the knives in a way not detectable by normal people, introduced the Hasidic hallaf (hasidishe hallaf).[citation needed] It differs from the previously used knife design because it is made of molten steel and polished to a mirror gloss in which scratches could be seen as well as felt. The new knife was controversial and one of the reasons for the 1772 excommunication of the Hasidim.[citation needed] As of present time, the "Hassidic hallef" is universally accepted and is the only permitted blade allowed in religious communities.[34]

Other rules

[edit]The animal may not be stunned prior to the procedure,[citation needed] as is common practice in non-kosher modern animal slaughter since the early 20th century.

It is forbidden to slaughter an animal and its young on the same day.[35] An animal's "young" is defined as either its own offspring, or another animal that follows it around.

The animal's blood may not be collected in a bowl, a pit, or a body of water, as these resemble ancient forms of idol worship.[citation needed]

If the shochet accidentally slaughters with a knife dedicated to idol worship, he must remove an amount of meat equivalent to the value of the knife and destroy it.[clarification needed] If he slaughtered with such a knife on purpose, the animal is forbidden as not kosher.[citation needed]

Post-procedure requirements

[edit]Bedikah

[edit]The carcass must be checked to see if the animal had any of a specific list of internal injuries that would have rendered the animal a treifah before the slaughter. These injuries were established by the Talmudic rabbis as being likely to cause the animal to die within 12 months time.

Today all mammals are inspected for lung adhesions (bedikat ha-reah "examination of the lung") and other disqualifying signs of the lungs, and most kosher birds will have their intestines inspected for infections.

Further inspection of other parts of the body may be performed depending on the stringency applied and also depending on whether any signs of sickness were detected before slaughter or during the processing of the animal.

Glatt

[edit]Glatt (Yiddish: גלאַט) and halak (Hebrew: חלק) both mean "smooth". In the context of kosher meat, they refer to the "smoothness" (lack of blemish) in the internal organs of the animal. In the case of an adhesion on cattle's lungs specifically, there is debate between Ashkenazic customs and Sephardic customs. While there are certain areas of the lung where an adhesion is allowed, the debate revolves around adhesions which do not occur in these areas.

Ashkenazic Jews rule that if the adhesion can be removed (there are various methods of removing the adhesion, and not all of them are acceptable even according to the Ashkenazic custom) and the lungs are still airtight (a process that is tested by filling the lungs with air and then submerging them in water and looking for escaping air), then the animal is still kosher but not glatt.

If, in addition, there were two or fewer adhesions, and they were small and easily removable, then these adhesions are considered a lesser type of adhesion, and the animal is considered glatt.[36] Ashkenazi custom permits eating non-glatt kosher meat, but it is often considered praiseworthy to only eat glatt kosher meat.[37]

Sephardic Jews rule that if there is any sort of adhesion on the forbidden areas of the lungs, then the animal is not kosher. This standard is commonly known as halak Beit Yosef. It is the strictest in terms of which adhesions are allowed.

The Rema (an Ashkenazi authority) had an additional stringency, of checking adhesions on additional parts of the lung which Sephardi practice does not require. Some Ashkenazi Jews keep this stringency.[37]

Nikkur

[edit]Porging[note 1] refers to the halakhic requirement to remove the carcass's veins, chelev (caul fat and suet)[40] and sinews.[41][39] The Torah prohibits the eating of certain fats, so they must be removed from the animal. These fats are typically known as chelev. There is also a biblical prohibition against eating the sciatic nerve (gid hanasheh), so that, too, is removed.[42]

The removal of the chelev and the gid hanasheh, called nikkur, is considered complicated and tedious, and hence labor-intensive, and even more specialized training is necessary to perform the act properly.

While the small amounts of chelev in the front half of the animal are relatively easy to remove, the back half of the animal is far more complicated, and it is where the sciatic nerve is located.

In countries such as the United States, where there exists a large non-kosher meat market, the hindquarters of the animal (where many of these forbidden meats are located) is often sold to non-Jews, rather than trouble with the process.

This tradition goes back for centuries[43] where local Muslims accept meat slaughtered by Jews as consumable; however, the custom was not universal throughout the Muslim world, and some Muslims (particularly on the Indian subcontinent) did not accept these hindquarters as halal. In Israel, on the other hand, specially trained men are hired to prepare the hindquarters for sale as kosher.

Kashering

[edit]Because of the biblical prohibition of eating blood,[44] all blood must be promptly removed from the carcass.

All large arteries and veins are removed, as well as any bruised meat or coagulated blood. Then the meat is kashered, a process of soaking and salting the meat to draw out all the blood. A special large-grained salt, called kosher salt, is used for the kashering process.

If this procedure is not performed promptly, the blood is considered to have "set" in the meat, and the meat is no longer considered kosher except when prepared through broiling with appropriate drainage.

Giving of the Gifts

[edit]The Torah requires a shochet to give the foreleg, cheeks and maw to a kohen even though he does not own the meat. Thus, it is desirable that the shochet refuse to perform the shechita unless the animal's owner expresses their agreement to give the gifts. Rabbinical courts have the authority to excommunicate a shochet who refuses to perform this commandment.

The Rishonim pointed out that the shochet cannot claim that, since the animal does not belong to him, he cannot give the gifts without the owner's consent. On the contrary, since the average shochet is reputed to be well versed and knowledgeable in the laws of shechitah ("Dinnei Shechita"), the rabbinical court relies on him to withhold his shechita so long as the owner refuses to give the gifts.[45]

Covering of the blood

[edit]Full article: Covering of the blood

It is a positive commandment incumbent upon the shochet to cover the blood of chayot (non-domesticated animals) and ofot (birds) but not b'heimot (domesticated animals).[46]

The shochet is required to place dirt on the ground before the slaughter, and then to perform the cut over that dirt, in order to drop some of the blood on to the prepared dirt. When the shechita is complete, the shochet grabs a handful of dirt, says a blessing and then covers the blood.

The meat is still kosher if the blood does not get covered; covering the blood is a separate mitzvah which does not affect the kosher status of the meat.

Animal welfare controversies

[edit]"Opposition to the Jewish methods of slaughter has a long history, starting at least as far back as the mid-Victorian era."[47]

In the United Kingdom

[edit]In 2003, Compassion in World Farming supported recommendations made by the UK's Farm Animal Welfare Council, the government's animal welfare advise committee, of outlawing slaughter without stunning, stating that "We believe that the law must be changed to require all animals to be stunned before slaughter."[48][49] The council's recommendations were that slaughter without pre-stunning was "unacceptable", and that the exemption of religious practices under the Welfare of Animals (Slaughter or Killing) Regulations 1995 should be repealed.[50]

In 2004, the government issued its response to the FAWC's 2003 report in the form of a consultation document, indicating that the government was not intending to adopt the FAWC's recommendation to repeal religious exemptions to the Welfare of Animals Regulations (1995), but that it might consider implementing the labelling of meat originating from animals slaughtered without pre-stunning on a voluntary basis. The RSPCA responded to the government's consultation and urged it to consider the animal welfare implications of allowing continuation of slaughter without pre-stunning, as well as pressing for compulsory labelling of meat from animals slaughtered in this way.[citation needed]

However, in its final response to the FAWC report in March 2005, the government again stated that it would not change the law and that slaughter without pre-stunning would continue to be permitted for Jewish and Muslim groups.[citation needed]

In April 2008, the UK government's Food and Farming minister, Lord Rooker, stated his belief that halal and kosher meat should be labeled when sold, in order for members of the public to have choice over their purchases. Rooker stated that "I object to the method of slaughter ... my choice as a customer is that I would want to buy meat that has been looked after, and slaughtered in the most humane way possible." The RSPCA supported Lord Rooker's views.[51]

In 2009, the FAWC again advised on ending practices of slaughtering wherein animals were not stunned before their throats were cut, stating that "significant pain and distress" was caused by leaving the spinal cord of the animal intact. However, the council also recognised the difficulties of reconciling scientific matters and those of faith, urging the government to "continue to engage with religious communities" as part of making progress.[52] In response to outreach from The Independent, Massood Khawaja, then-president of the Halal Food Authority, stated that all animals passing through slaughterhouses regulated by its organisation were stunned, in comparison to those regulated to another authority on halal slaughter, the Halal Monitoring Committee.[52] Halal and kosher butchers denied the FAWC's findings of cruelty in slaughter without pre-stunning, and expressed anger over the FAWC recommendation.[49] Majid Katme of the Muslim Council of Britain also disagreed, stating that "it's a sudden and quick hemorrhage. A quick loss of blood pressure and the brain is instantaneously starved of blood and there is no time to start feeling any pain."[53]

The Gutachten (expert reports)

[edit]When shechita came under attack in the 19th century, Jewish communities resorted to expert scientific opinions which were published in pamphlets called Gutachten.[54] Among these authorities was Joseph Lister, who introduced the concept of sterility in surgery.[citation needed]

General description of controversy

[edit]The practices of handling, restraining, and unstunned slaughter have been criticized by, among others, animal welfare organizations such as Compassion in World Farming.[55] The UK Farm Animal Welfare Council said that the method by which kosher and halal meat is produced causes "significant pain and distress" to animals and should be banned.[52]

According to FAWC it can take up to two minutes after the incision for cattle to become insensible. Compassion in World Farming also supported the recommendation saying "We believe that the law must be changed to require all animals to be stunned before slaughter."[48][49]

Mr Bradshaw said the Government had maintained its position in not accepting FAWC's recommendation that slaughter without prior stunning should be banned, as they respected the rights of communities in Britain to slaughter animals in accordance with the requirements of their religion.[56][57][58][59][60]

The Federation of Veterinarians of Europe has issued a position paper on slaughter without prior stunning, calling it "unacceptable."[61]

The American Veterinary Medical Association has no such qualms, as leading US meat scientists support shechita as a humane slaughtering method as defined by the Humane Slaughter Act.

A 1978 study at the University of Veterinary Medicine Hanover indicates that shechita gave results which proved "pain and suffering to the extent as has since long been generally associated in public with this kind of slaughter cannot be registered" and that "[a complete loss of consciousness] occurred generally within considerably less time than during the slaughter method after captive bolt stunning."[62] However, the lead of the study William Schulze warned in his report that the results may have been due to the captive bolt device they used being defective.[62]

Nick Cohen, writing for the New Statesman, discusses research papers collected by Compassion in World Farming which indicate that the animal suffers pain during the process.[63] In 2009, Craig Johnson and colleagues showed that calves that have not been stunned feel pain from the cut in their necks,[64] and they may take at least 10–30 seconds to lose consciousness.[65]

Temple Grandin says that the experiment needs to be repeated using a qualified shochet and knives of the correct size sharpened in the proper way.[66]

Jewish and Muslim commentators cite studies that show shechita is humane and that criticism is at least partially motivated by antisemitism.[67][68] A Knesset committee announced (January, 2012) that it would call on European parliaments and the European Union to put a stop to attempts to outlaw kosher slaughter. "The pretext [for this legislation] is preventing cruelty to animals or animal rights—but there is sometimes an element of anti-Semitism and there is a hidden message that Jews are cruel to animals," said Committee Chair MK Danny Danon (Likud).[69]

Studies done in 1994 by Temple Grandin, and another in 1992 by Flemming Bager, showed that when the animals were slaughtered in a comfortable position they appeared to give no resistance and none of the animals attempted to pull away their head. The studies concluded that a shechita cut "probably results in minimal discomfort" because the cattle stand still and do not resist a comfortable head restraint device.[70]

Temple Grandin gives various times for loss of consciousness via kosher ritual slaughter, ranging from 15 to 90 seconds depending on measurement type and individual kosher slaughterhouse.[71] She elaborates on what parts of the process she finds may or may not be cause for concern.[72][73] In 2018, Grandin stated that kosher slaughter, no matter how well it is done, is not instantaneous, whereas stunning properly with a captive bolt is instantaneous.[74]

Efforts to improve conditions in shechita slaughterhouses

[edit]Temple Grandin is opposed to shackling and hoisting as a method of handling animals and wrote, on visiting a shechita slaughterhouse,

I will never forget having nightmares after visiting the now defunct Spencer Foods plant in Spencer, Iowa, fifteen years ago. Employees wearing football helmets attached a nose tong to the nose of a writhing beast suspended by a chain wrapped around one back leg. Each terrified animal was forced with an electric prod to run into a small stall which had a slick floor on a forty-five-degree angle. This caused the animal to slip and fall so that workers could attach the chain to its rear leg [in order to raise it into the air]. As I watched this nightmare, I thought, 'This should not be happening in a civilized society.' In my diary I wrote, 'If hell exists, I am in it.' I vowed that I would replace the plant from hell with a kinder and gentler system.[75]

Efforts are made to improve the techniques used in slaughterhouses. Temple Grandin has worked closely with Jewish slaughterers to design handling systems for cattle, and has said: "When the cut is done correctly, the animal appears not to feel it. From an animal-welfare standpoint, the major concern during ritual slaughter are the stressful and cruel methods of restraint (holding) that are used in some plants."[76]

When shackling and hoisting is used, it is recommended[77] that cattle not be hoisted clear of the floor until they have had time to bleed out.

Agriprocessors controversy

[edit]The prohibition of stunning and the treatment of the slaughtered animal expressed in shechita law limit the extent to which Jewish slaughterhouses can industrialize their procedures.

The most industrialized attempt at a kosher slaughterhouse, Agriprocessors of Postville, Iowa, became the center of controversy in 2004, after People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals released a gruesome undercover video of cattle struggling to their feet with their tracheas and esophagi ripped out after shechita. Some of the cattle actually got up and stood for a minute or so after being dumped from the rotating pen.[78][79]

The OU's condonation of Agriprocessors as a possibly inhumane, yet appropriately glatt kosher company has led to discussion as to whether or not industrialized agriculture has undermined the place of halakha (Jewish law) in shechita as well as whether or not halakha has any place at all in Jewish ritual slaughter.[80]

Jonathan Safran Foer, a Jewish vegetarian, narrated the short documentary film If This Is Kosher..., which records what he considers abuses within the kosher meat industry.[81]

Forums surrounding the ethical treatment of workers and animals in kosher slaughterhouses have inspired a revival of the small-scale, kosher-certified farms and slaughterhouses, which are gradually appearing throughout the United States.[82]

See also

[edit]- Christian dietary laws

- Comparison of Islamic and Jewish dietary laws

- DIALREL – report from the EU

- Dhabihah – Islamic ritual slaughter

- Jhatka – Indian ritual slaughter

- Mashgiach

- Joseph Molcho

- Schochet – surname meaning "slaughterer"

- Tza'ar ba'alei chayim – Jewish commandment which bans causing animals unnecessary suffering

- Terefah controversy, a severe halakhic controversy about a specific type of terefah, among the Fez Jewry between Toshavim and Megorashim

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ The English word porge is from Judeo-Spanish porgar (from Spanish purgar "to purge").[38] The Hebrew is nikkur (niqqur) and the Yiddish is treibering. This is done by a menaḳḳer (Yiddish).[39]

References

[edit]- ^ Deuteronomy 12:21

- ^ a b c d e Steinsaltz, Adin (17 June 1976). The Essential Talmud. pp. 224–225.

- ^ Shulchan Aruch, Yoreh De'ah 79

- ^ Deuteronomy 14:12–18

- ^ Zivotofsky, Ari Z. (2011). "Kashrut of Birds – The Biblical Story". Is Turkey Kosher?. Scharf Associates. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- ^ Zivotofsky, Ari Z. (2011). "Kashrut of Birds – The Need for a Mesorah". Is Turkey Kosher?. Scharf Associates. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- ^ Leviticus 11:9–12

- ^ a b c "Shulchan Arukh, Yoreh De'ah 21". Sefaria. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ "Shulchan Arukh, Yoreh De'ah 6". Sefaria. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ a b "Mishneh Torah, Ritual Slaughter 2:7". Sefaria. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ Sefer Beit David 24:4

- ^ a b S. D. Rosen. Physiological Insights into Shechita. The Veterinary Record 12 June 2004

- ^ Zdun, M., Frąckowiak, H., Kiełtyka-Kurc, A., Kowalczyk, K., Nabzdyk, M. and Timm, A. (2013), The Arteries of Brain Base in Species of Bovini Tribe. Anat. Rec., 296: 1677–1682. doi:10.1002/ar.22784

- ^ "Shulchan Arukh, Yoreh De'ah 23". Sefaria. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ "Shulchan Arukh, Yoreh De'ah 23:2". Sefaria. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ "Shulchan Arukh, Yoreh De'ah 23:2". Sefaria. Rama's commentary on Shulchan Aruch 23-2 requires strict adherence to disqualifying any pause. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Shulchan Arukh, Yoreh De'ah 24:1". Sefaria. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ "שו"ת תשובות והנהגות ח"ד - שטרנבוך, משה (page 173 of 568)". hebrewbooks.org. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ "Widespread Slaughter Method Scrutinized for Alleged Cruelty". The Forward. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ "A Cut Above: Shechita in the Crosshairs, Again | STAR-K Kosher Certification". star-k.org. 15 August 2013. A standing Matter. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ "Shulchan Arukh, Yoreh De'ah 24:7". Sefaria. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ a b "Shulchan Arukh, Yoreh De'ah 24:12". Sefaria. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ "Shulchan Arukh, Yoreh De'ah 24:15". Sefaria. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ a b "The rules of Shechita for performing a proper cut during kosher slaughter". Grandin.com. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ "Article: Shehitah Jewish Encyclopedia 1906". Jewishencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ "Deconstructing Kosher Slaughter Part 2: The Basics". The Kosher Omnivore's Quest. Archived from the original on 13 January 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ "Mishnah Chullin 5:3". www.sefaria.org. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ Battegay, Caspar, 1978- (2018). Jüdische Schweiz : 50 Objekte erzählen Geschichte = Jewish Switzerland : 50 objects tell their stories. Lubrich, Naomi, 1976-, Jüdisches Museum der Schweiz (1. Auflage ed.). Basel. ISBN 978-3-85616-847-6. OCLC 1030337455.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Klein, Reuven Chaim (22 October 2019). "Bereishis: The Sword of Methusaleh". The Times of Israel. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- ^ "Shulchan Arukh, Yoreh De'ah 6". www.sefaria.org. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ "Shulchan Arukh, Yoreh De'ah 18". www.sefaria.org. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ "Kaf HaChayim on Shulchan Arukh, Yoreh De'ah 18:28:1". www.sefaria.org. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ "Mishnah Chullin 1:2". www.sefaria.org. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ Vertheim, Aharon (1992). Law and Custom in Hasidism. KTAV Publishing House, Inc. pp. 302–. ISBN 978-0-88125-401-3.

- ^ Leviticus 22:28

- ^ "Beit Yousef Meat | Rabbi David Sperling | Ask the rabbi | yeshiva.co".

- ^ a b "The Difference between 'Glatt' and Kosher Meat". Archived from the original on 26 July 2018.

- ^ "porge". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ a b "Porging". Jewish Encyclopedia 1905. Jewishencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ Mishneh Torah Kedushah, Forbidden Foods 8:1

- ^ Mishneh Torah Kedushah, Forbidden Foods 6:1

- ^ Eisenstein, Judah David (19 June 1901). "PORGING". Jewish Encyclopedia. Vol. 10. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. p. 132. LCCN 16014703. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- ^ What's the Truth about Nikkur Achoraim? kashrut.com, 2007

- ^ Genesis 9:4, Leviticus 17:10–14, Deuteronomy 12:23–24

- ^ Shulchan Gavoah to Yoreh Deah 61:61. Text: "The obligation of giving the gifts lay upon the Shochet to separate the parts due to the Kohanim. Apparently, the reasoning is that since the average Shochet is a "Talmid Chacham", since he completed the prerequisite of understanding the (complex) laws of Shechita and Bedikah. It is assumed that he -as well- is knowledgeable in the details of the laws of giving the gifts, and will not put the Mitzvah aside. This, however, is not the case with the animal's owner, since the average owner is an Am ha-aretz not wholly knowledgeable in the laws of the gifts -and procrastinates in completing the mitzvah."

- ^ Mishnah Torah, laws of kosher slaughter 14:1

- ^ TONY KUSHNER (1989) STUNNING INTOLERANCE, Jewish Quarterly, 36:1, 16-20, DOI: 10.1080/0449010X.1989.10705025

- ^ a b "BBC: Should Halal and Kosher meat be banned?". BBC News. 16 June 2003.

- ^ a b c "Halal and Kosher slaughter 'must end'". BBC News. 10 June 2003.

- ^ "Slaughter without pre-stunning (for religious purposes)". RSPCA. February 2015. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2010. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ^ CIWF Halal and kosher meat should not be slipped in to food chain, says minister

- ^ a b c Hickman, Martin (22 June 2009). "End 'cruel' religious slaughter, say scientists". The Independent. London.

- ^ Karen Armstrong, Muhammad: Prophet for Our Time, HarperPress, 2006, p.167 ISBN 0-00-723245-4

- ^ Gutachten

- ^ "Compassion in World Farming: Unstunned Hallal and Kosher Meat (with link to collected reports)". Ciwf.org.uk. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ "The Government response to the Farm Animal Welfare Council's report on animal welfare at slaughter".

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 July 2009. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Kirby, Terry (2 April 2004). "Government backs down on religious slaughter banThe Independent". The Independent. London.

- ^ The religious stipulations in both faiths stem from the belief that animals should not eat an animal that has undergone hurt or injury in dying. They say the swift severance of the jugular vein and the draining of blood, consumption of which is forbidden, causes the animal to feel virtually nothing.

- ^ "Animals should not eat an animal" should perhaps read "one should not eat an animal". "The swift severance of the jugular vein" is not an accurate description of kosher or halal slaughter. Four major blood vessels are severed: two of which supply the brain with oxygenated blood, and two jugular veins that transport blood back to the heart. Consciousness is maintained by a constant flow of oxygenated blood over the brain. It is in "conventional" slaughter that only one jugular is cut. One of FAWC's recommendations was to standardize slaughter by always cutting two carotid arteries.

- ^ ["Slaughter of Animals Without Prior Stunning" (PDF). Federation of Veterinarians of Europe.

- ^ a b Schulze W., Schultze-Petzold H., Hazem A. S., Gross R. Experiments for the objectification of pain and consciousness during conventional (captive bolt stunning) and religiously mandated ("ritual cutting") slaughter procedures for sheep and calves. Deutsche Tierärztliche Wochenschrift 1978 Feb 5;85(2):62-6. English translation by Dr Sahib M. Bleher

- ^ Cohen, Nick (5 July 2004). "God's own chosen meat". New Statesman. 133 (4695): 22–23. ISSN 1364-7431. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

Possible reasons for the suffering are laid out in various research papers that Compassion in World Farming has collected. After the throat is cut, large clots can form at the severed ends of the carotid arteries, leading to occlusion of the wound (or "ballooning" as it is known in the slaughtering trade). Occlusions slow blood loss from the carotids and delay the decline in blood pressure that prevents the suffering brain from blacking out. In one group of calves, 62.5 per cent suffered from ballooning. Even if the slaughterman is a master of his craft and the cut to the neck is clean, blood is carried to the brain by vertebral arteries, and it keeps cattle conscious of their pain.

- ^ TJ Gibson; CB Johnson; JC Murrell; CM Hulls; SL Mitchinson; KJ Stafford; AC Johnstone; DJ Mellor (13 February 2009). "Electroencephalographic responses of halothane-anaesthetised calves to slaughter by ventral-neck incision without prior stunning" (PDF). New Zealand Veterinary Journal. 57 (2): 77–83. doi:10.1080/00480169.2009.36882. PMID 19471325. S2CID 205460429.

- ^ Andy Coghlan (13 October 2009). "Animals feel the pain of religious slaughter". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 15 October 2009. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ [1]Temple Grandin Discussion of research that shows that Kosher or Halal slaughter without stunning causes pain

- ^ "Halal, shechita and the politics of animal slaughter". TheGuardian.com. 6 March 2014.

- ^ "Shechita is not a painful method of slaughter, claims Jewish community". The Daily Telegraph. April 2011. Archived from the original on 4 October 2022.

- ^ Harman, Danna (10 January 2012). "Israeli Knesset committee seeks end to European bans on kosher slaughter Ha'aretz Knesset Committee on Immigration, Absorption and Diaspora Affairs chair says attempts to outlaw 'Shechita' contain 'anti-Semitic' elements. Ha'aretz Johnathan Lis January 10, 2012". Haaretz. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ ">Religious slaughter and animal welfare:a discussion for meat scientists". grandin.com. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ "Kosher Box Operation, Design, and Cutting Technique will Affect the Time Required for Cattle to Lose Consciousness". www.grandin.com. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ Grandin, Temple (August 2011). "Welfare During Slaughter without stunning (Kosher or Halal) differences between Sheep and Cattle". Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- ^ Grandin, Temple (28 April 2011). "Maximising Animal Welfare in Kosher Slaughter". Forward.com. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ Yanklowitz, Rabbi Shmuly (13 June 2018). "Improving Animal Treatment in Slaughterhouses: An Interview with Dr. Temple Grandin". Medium. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ Temple Grandin Thinking in Pictures. My Life with Autism

- ^ "Recommended Ritual Slaughter Practices". Grandin.com.

- ^ Hui, Y. H. (11 January 2012). Handbook of Meat and Meat Processing, Second Edition. Y. H. Hui (editor). CRC Press. ISBN 9781439836835. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ The New York Times Videotapes Show Grisly Scenes at Kosher Slaughterhouse By DONALD G. McNEIL Jr. 30 November 2004

- ^ Aaron Gross: When Kosher Isn't Kosher Archived 10 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Tikkun Magazine, March/April 2005, Vol. 20, No. 2.

- ^ Fishkoff, Sue (2010). Kosher Nation. New York: Schocken.

- ^ Foer, Jonathan Safran. "If This Is Kosher…".

- ^ Romanoff, Zan (13 March 2013). "Kosher – Farm to table | Food". Jewish Journal. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

Further reading

[edit]- Arluke, Arnold; Sax, Boria (1992). "Understanding Animal Protection and the Holocaust". Anthrozoös. 5 (1): 6–31. doi:10.2752/089279392787011638. S2CID 2536374.

- The Jewish method of Slaughter Compared with Other Methods : from the Humanitarian, Hygienic, and Economic Points of View (1894) Author: Dembo, Isaak Aleksandrovich, 1847?–1906 [the date is incorrectly given as 1984, corrected here]

- Neville G. Gregory, T. Grandin: Animal Welfare and Meat Science Publisher: CABI; 1 edition 304 pp (1998)[ISBN missing]

- Pablo Lerner and Alfredo Mordechai Rabello The Prohibition of Ritual Slaughtering (Kosher Slaughtering and Halal) and Freedom of Religion of Minorities Journal of Law and Religion 2006

- Dorothee Brantz Stunning Bodies: Animal Slaughter, Judaism, and the Meaning of Humanity in Imperial Germany

- Robin Judd The Politics of Beef: Animal Advocacy and the Kosher Butchering Debates in Germany

- Appendix I in Meat and Meat Processing. Y. H. Hui; (CRC Press. Second Edition 2012) A Discussion of Stunned and Nonstunned Slaughter prepared by an International Group of Scientists and Religious Leaders: Dr Shuja Shali (Muslim Council of Britain), Dr Stuart Rosen (Imperial College, London, UK), Dr Joe M. Regenstein (Cornell University, USA) and Dr Eric Clay (Shared Journeys, USA). Reviewers: Dr Temple Grandin (Colorado State University, USA), Dr. Ari Zivotofsky (Bar-Ilan University, Israel) Dr Doni Zivotofsky (DVM, Israel), Rabbi David Sears (Author of Vision of Eden, Brooklyn, USA, Dr Muhammad Chaudry (Islamic Food and Nutrition Council of America, Chicago) and Paul Hbhav, (Islamic Services of America) Google books

- David Fraser Anti-Shechita Prosecutions in the Anglo-American World, 1855–1913: "A major attack on Jewish freedoms"(North American Jewish Studies)[ISBN missing]

External links

[edit]- Ari Z. Zivotofsky Government Regulations of Shechita (Jewish Religious Slaughter) in the Twenty-first Century: Are They Ethical?

- Resolution on Disturbing Trends in Europe of Concern to Jewish and Other Religious Minorities The Rabbinical Assembly

- The assault on shechita and the future of Jews in Europe. World Jewish Congress

- Lewis, Melissa A Comparative Analysis of Kosher Slaughter Regulation, and recommendations as to how this issue should be dealt with in the United States

- The Cutting Edge: The debate over the regulation of ritual slaughter in the western world Jeremy A. Rovinsky

- Shechita at The Orthodox Union

- What's the Truth about Niqqur Acharonayim? by Rabbi Dr. Ari Z. Zivotofsky

- Laws of Judaism concerning food laws of ritual slaughter

- Shechita – The Jewish Religious Humane Method of Animal Slaughter for Food

- Shehitah: A photo essay Archived 14 September 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- From the Slaughterhouse to the Consumer. Transparency and Information in the Distribution of Halal and Kosher Meat. Dialrel project report. Authors: J. Lever, María Puig de la Bellacasa, M. Miele, Marc Higgin. University of Cardiff Cardiff, UK

- dialrel final report: Consumer and Consumption issues: Halal and Kosher Focus Groups Results Dr Florence Bergeaud-Blacker IREMAM (CNRS) & Université de la Méditerrainée, Aix-Marseille; Dr Adrian Evans, University of Cardiff; Dr Ari Zivotofsky, Bar-Ilan University

- Comparative Report of the Public Debates on Religious Slaughter in Germany, UK, France & Norway. DIALREL Encouraging Dialogue in Issues of Religious Slaughter. Comparative report: Lill M Vramo & Taina Bucher: SIFO (National Institute for Consumer Research); National Reports (in appendix): Florence Bergeaud-Blecker (French report) Adrian Evans (UK report) Taina Bucher, Lill M. Vramo & Ellen Esser (German report) Taina Bucher, Laura Terragni & Lill M. Vramo (Norwegian report) 01/03/2009

- S.D. Rosen Physiological Insights into Shechita The Veterinary Record (2004) 154, 759–765

- Should Animals be Stunned Before Slaughter? Raffi Berg BBC

- Rabbi Eliezer Melamed, What Does "Glatt" Mean? on Arutz Sheva.

Shechita

View on GrokipediaReligious and Historical Foundations

Biblical and Talmudic Basis

The biblical foundation for shechita derives from the Torah's regulations on permissible animal slaughter for consumption, particularly in Deuteronomy 12:15–25, which permits Israelites to slaughter cattle, sheep, and goats from their herds and flocks in their local settlements when the designated sanctuary is distant, provided the blood is drained and poured upon the ground like water. This drainage is mandated to avoid consuming blood, explicitly identified as the life force or soul of the animal (Deuteronomy 12:23), building on the earlier Noachide prohibition against eating flesh with its lifeblood (Genesis 9:4). The passage emphasizes that such slaughter must follow the method "as I have commanded you" (Deuteronomy 12:21), a phrase interpreted in Jewish tradition as referring to an oral transmission of procedural details to Moses at Sinai, though the written Torah omits the mechanics to prioritize the sanctity of blood avoidance over technical minutiae.[1][7] Talmudic sources systematize and expand these biblical imperatives in Tractate Chullin of the Mishnah and Babylonian Talmud, which focuses on the ritual slaughter of non-sacrificial ("secular") mammals and birds to render them fit for kosher consumption.[8] The Mishnah (Chullin 1:1–2) defines valid shechita as an uninterrupted transverse incision with an exceptionally sharp, defect-free knife (chalaf) severing the trachea (simla) and esophagus (vayeis), carotid arteries, and major blood vessels in the neck, ensuring swift death via exsanguination while deriving from the Torah's blood prohibition to invalidate incomplete or delayed cuts that might leave the animal alive. The Gemara in Chullin further elucidates derivations, such as requiring inspection of the knife pre- and post-slaughter to prevent defects akin to biblical treifot (fatal injuries rendering animals non-kosher, Leviticus 22:22), and links the practice to fulfilling Deuteronomy 12:21 as a positive commandment when meat is desired.[9] These rules prioritize causal efficacy in blood removal and animal dispatch, grounded in empirical observations of anatomy and physiology transmitted through rabbinic analysis rather than innovation.Historical Evolution and Codification

The biblical foundation for shechita lies in commandments permitting the slaughter of permitted animals for food, such as Deuteronomy 12:21, which states that Israelites may "slaughter... within any of your towns... as much as you desire, just as the gazelle and the deer are eaten," implying a regulated process distinct from profane killing. However, the Torah provides no explicit technique, deriving instead from the Oral Law to comply with prohibitions against ingesting blood (Leviticus 17:11-14) or flesh torn from a living animal (Genesis 9:4; Deuteronomy 12:23-25), with the method designed to expel blood rapidly and induce swift unconsciousness.[10][11] The earliest written codification appears in the Mishnah, redacted around 200 CE in Tractate Chullin (chapters 1-12), which mandates a single, uninterrupted transverse cut with a flawlessly sharp, smooth-edged knife across the trachea, esophagus, and major carotid arteries and jugular veins, prohibiting pauses (shehiyah), pressing (derasah), or incomplete severance. The Babylonian Talmud, finalized circa 500 CE, elaborates extensively in the Gemara on Chullin, analyzing knife defects (e.g., nicks detectable only by fingernail test), slaughter orientations, and validations through post-mortem lung inspections for adhesions (bedikah), thereby resolving interpretive disputes and establishing binding precedents for halakhic validity.[12] Medieval authorities further systematized these rules amid diaspora challenges. Maimonides, in his Mishneh Torah (Hilchot Shechitah, completed 1180 CE), enumerates 68 chapters on slaughter, stipulating shochet training, ritual purity, and disqualifications like intent or incompetence, while emphasizing humane intent through precise technique to avert tza'ar ba'alei chayim (animal suffering). Rabbi Joseph Karo consolidated prior sources in the Shulchan Aruch's Yoreh De'ah (sections 1-30, published 1565 CE), ruling on eligible practitioners and invalidations, with Rabbi Moses Isserles' glosses (1569 CE) accommodating Ashkenazic variations, such as additional stringencies on knife length relative to animal size.[13][14] These codes standardized practice, preventing deviations while preserving the Talmudic framework's emphasis on empirical verification of slaughter efficacy.[15]Eligible Animals and Species

Permitted Mammals and Birds

In Jewish dietary law, shechita applies exclusively to kosher mammals and birds, which must meet specific biblical criteria for eligibility. Mammals are permitted if they both chew their cud (ruminate) and possess fully cloven hooves, as stipulated in Leviticus 11:3 and Deuteronomy 14:6.[16][17] Examples include bovine species such as cattle and buffalo, ovine species like sheep, caprine species such as goats, and cervids including deer and antelope.[16][18] These animals must undergo shechita to render their meat permissible for consumption, involving a precise throat incision to sever the trachea, esophagus, carotid arteries, and jugular veins while minimizing suffering.[1] Birds eligible for shechita lack the explicit anatomical signs provided for mammals in the Torah; instead, permissibility is determined by longstanding rabbinic tradition identifying non-predatory, domesticated fowl as kosher, excluding those listed as forbidden in Leviticus 11:13–19 and Deuteronomy 14:11–18, such as eagles, vultures, and owls.[19][16] Commonly accepted kosher birds include chickens (Gallus domesticus), turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo), ducks (Anas platyrhynchos and related species), geese (Anser species), and pigeons or doves (Columba livia).[16][20] The Orthodox Union has documented these through historical acceptance by Jewish communities and examination by expert shochtim, ensuring consistency with Talmudic principles in tractate Chullin.[21] Shechita for birds follows the same procedural standards as for mammals, adapted to their anatomy, such as using a specialized chalaf knife for poultry.[22] Both mammals and birds must be healthy and free of defects at the time of slaughter, with post-shechita inspection for treifot (internal blemishes) to confirm fitness for consumption.[1] This framework ensures that only species aligning with Torah mandates undergo the ritual, distinguishing shechita from conventional slaughter methods.[23]Exclusions and Rationale

Mammalian species ineligible for shechita include those failing the dual biblical criteria of ruminating (chewing the cud) and possessing fully cloven hooves, as stipulated in Leviticus 11:3-8 and Deuteronomy 14:6-8. Examples encompass the pig, which has cloven hooves but does not ruminate; the camel, which ruminates but lacks fully cloven hooves; the hare and rock badger, which appear to ruminate but do not have cloven hooves; and carnivores or omnivores such as horses, dogs, and cats, which meet neither criterion.[24] [25] Avian exclusions similarly derive from Leviticus 11:13-19 and Deuteronomy 14:11-18, which enumerate 24 prohibited bird species, primarily raptors and scavengers including eagles, vultures, ospreys, hawks, owls, and kites. The Talmud in Chullin identifies predatory behavior as a disqualifying trait, rendering birds of prey non-kosher due to their tearing of flesh with talons or beaks, in contrast to permitted domestic fowl like chickens, ducks, geese, and turkeys, which lack such characteristics.[26] Reptiles, amphibians, most insects, and invertebrates are categorically excluded under Leviticus 11:29-31, 41-47, as they do not align with kosher classifications for land, air, or water creatures. Fish and other aquatic life require fins and scales for eligibility but undergo no shechita, as their blood is not drained via slaughter.[27] The rationale for these exclusions rests on divine imperative without explicit causal explanation in the Torah text, framed as statutes (chukim) to foster discipline, ethical distinction from surrounding cultures, and symbolic separation of pure from impure.[28] Rabbinic sources, such as Ibn Ezra, propose secondary interpretations like avoidance of inherently impure or disease-prone flesh, though these remain speculative and secondary to the primary command of obedience to God's delineation of permissible sustenance.[29]Practitioners and Qualifications

Role and Training of the Shochet

The shochet serves as the designated practitioner who performs shechita, the ritual slaughter mandated by Jewish law to permit the consumption of meat from eligible animals. This role requires executing a single, continuous incision with a chalef—a razor-sharp, flawlessly smooth knife—to sever the trachea and esophagus, thereby ensuring rapid blood drainage and adherence to halakhic principles derived from Torah commandments.[30] Shochtim frequently double as bodekim, conducting post-slaughter examinations of the animal's lungs and organs for treifot (defects or diseases) that invalidate the carcass under kosher standards. The position demands unwavering precision, as any deviation, such as a nick in the knife or incomplete cut, renders the slaughter invalid and necessitates restarting the process.[30] Qualifications for a shochet include being a Jew of sound character and religious observance, with comprehensive knowledge of shechita laws, animal anatomy, and the ethical imperatives of minimizing suffering. Prior to each act of slaughter, the shochet recites a specific blessing: "Blessed are You, L-rd our G-d, King of the universe, who has sanctified us with His commandments and commanded us concerning shechita."[30] Training to become a shochet entails extended study under a qualified mentor, often spanning several years, encompassing textual analysis of halakhic sources like the Shulchan Aruch, practical instruction in animal restraint and slaughter techniques, and mastery of knife maintenance. Apprentices learn to perform shtellen ah chalef, the meticulous sharpening and inspection of the blade to confirm its perfection, as even microscopic imperfections disqualify it.[30][31] Certification, termed kabbalah, is conferred by a rabbinic authority after rigorous evaluation, including written knowledge assessments, knife examinations, and supervised practical demonstrations on fowl or livestock to verify competence. Certified shochtim receive a formal document affirming their status, often denoted by the acronym שו"ב (shochet u-bodek), signifying dual expertise in slaughter and inspection.[30]Certification and Ethical Standards

A shochet must undergo extensive training and examination to obtain certification, typically from rabbinical seminaries or kosher supervisory organizations such as the Orthodox Union or the Kashruth Council of Canada. Candidates are required to be observant Jewish males at least 18 years old, with proficiency in Hebrew and mastery of the Torah laws governing shechita, including the Shulchan Aruch's detailed regulations on slaughter techniques and disqualifications.[31][32] Training programs, which can span one to several years, combine theoretical study of halachic texts with practical instruction in knife sharpening, animal positioning, and the precise chalaf (incision) motion, culminating in oral and hands-on assessments to verify competence.[33][34] Certification is not perpetual; shochets must periodically demonstrate ongoing proficiency and piety, as lapses can lead to revocation by certifying authorities.[35] Ethical standards for certified shochets prioritize adherence to halachic imperatives that balance ritual validity with minimization of animal suffering, rooted in the prohibition of tza'ar ba'alei chayim (cruelty to living creatures). A shochet is expected to embody yirat shamayim (fear of Heaven), maintaining personal piety and moral sensitivity to the gravity of taking life, avoiding callousness through constant self-examination and knife checks for imperfections that could prolong distress.[35][2] The method mandates a single, uninterrupted cut with an exceptionally sharp, flawless blade to sever the trachea, esophagus, carotid arteries, and jugular veins, inducing rapid unconsciousness via cerebral anemia within seconds, as physiological studies affirm the efficacy of this vascular disruption in averting prolonged pain.[36][37] Violations, such as hesitation or improper handling, render the slaughter invalid and may disqualify the practitioner, with certifying bodies enforcing these standards to uphold Torah fidelity over secular welfare claims that often overlook shechita's empirical outcomes.[38][39]Slaughter Procedure

Preparation and Animal Handling

Prior to shechita, the animal must be confirmed as a member of a permitted kosher species and appear healthy, with no obvious signs of illness or injury that could indicate internal defects rendering it treif (carcass-forbidden under halakha).[2][15] The shochet visually inspects for such issues, as only sound animals are eligible for ritual slaughter to ensure compliance with Torah commandments derived from Deuteronomy 12:21.[1] Handling practices prioritize calm and gentle movement to reduce stress, with animals transported and positioned without beating, excessive prodding, or other agitating methods, aligning with Jewish ethical imperatives for compassionate treatment during the process.[40][15] No pre-slaughter stunning or sedation is permitted, as these interventions risk violating halakhic requirements for a precise, uninterrupted cut on a conscious animal, though empirical assessments by livestock experts confirm that proper handling facilitates rapid insensibility post-incision.[2][40] For mammals like cattle, restraint occurs in upright pens that secure the body comfortably while lightly holding the head to expose the neck, enabling a swift transverse incision without inverting the live animal—a method refined to enhance welfare and replace older, prohibited practices such as shackling a hind leg and hoisting upside down, banned by the Rabbinical Assembly's Committee on Jewish Law and Standards in 2000.[2][40] Body restraints are released during the cut to allow natural responses, and inversion follows only after death for bleeding. Poultry handling involves gentle positioning, often with checks for leg tendon integrity, and slaughter while the bird remains calm, sometimes suspended by legs immediately after but not during the initial cut.[15] These techniques, when executed by certified shochtim, aim to minimize distress through mechanical consistency rather than reliance on pharmacological means.[40]The Act of Shechita

The act of shechita involves a trained shochet making a single, rapid, and uninterrupted transverse incision across the front of the animal's neck using a chalaf, a specialized knife that must be surgically sharp, perfectly smooth, and free of any notches or irregularities.[41][39] The chalaf's blade length is required to be at least twice the width of the animal's neck to allow the cut to be made without the knife being covered by hide, wool, or feathers, ensuring visibility and precision during the procedure.[41][39] This incision severs the trachea, esophagus, common carotid arteries (and their branches) in the front of the neck supplying blood toward the brain, and jugular veins, which constitutes the core halachic requirement of cutting the simanei shechita (essential signs of slaughter), primarily the windpipe and food pipe, while the major vessels facilitate immediate and maximal exsanguination; the posterior vertebral arteries, which join the basilar artery at the base of the brain, remain uncut.[42][41][43] The cut is performed at a specific anatomical site on the neck, known as the hagrama, to target these structures effectively without deviation.[39][41] The motion is executed by drawing the chalaf across the throat in a continuous sweep, typically involving forward and backward strokes within the single action to complete the severance without pausing or pressing.[41][39] The procedure's design aims to induce unconsciousness almost instantaneously through cerebral anoxia and blood pressure collapse, with physiological studies indicating the animal becomes insensible within 2 to 10 seconds, minimizing any potential distress.[42] Prior to the cut, the shochet recites a blessing invoking divine permission for the act, underscoring its ritual significance.[41] Following the incision, blood is allowed to drain fully, as retention of blood renders the meat non-kosher under biblical prohibition.[41][42]Instruments and Techniques

The chalaf, or shechita knife, is the sole instrument employed in the ritual slaughter process, crafted from sharpened metal without any attachment to the ground per biblical requirements. It features a perfectly smooth, razor-sharp blade devoid of nicks, serrations, or points to ensure a clean incision that minimizes tissue trauma.[44][45] The blade length must exceed twice the width of the animal's neck—typically around 6 inches for poultry and 18 inches for cattle—to allow a single, uninterrupted stroke across the throat.[46][47] Prior to each slaughter, the shochet meticulously inspects the chalaf under light, often using a fingernail or specialized tools to detect microscopic imperfections that could invalidate the shechita. Post-slaughter verification confirms the blade's integrity, discarding any chalaf with defects to uphold ritual validity. Sharpness is critical, as dullness or irregularities can cause tearing rather than severing, potentially rendering the carcass treif (non-kosher).[44][38] The technique demands a trained shochet to position the animal securely, exposing the neck, and execute a swift, back-and-forth drawing motion just below the larynx, simultaneously severing the trachea, esophagus, carotid arteries, and jugular veins while sparing the spinal cord. This motion must avoid prohibited actions such as derasa (excessive pressing), gratt (scratching), ikuf (stabbing), charat (choking), or haladah (covering the knife in tissue), ensuring the cut remains visible and precise throughout.[48][15] For larger mammals, the shochet may use a steady stance or mechanical restraint to immobilize the animal without stunning, facilitating the horizontal cut; poultry slaughter employs similar principles with scaled-down chalafim and manual handling.[41][48]Prohibited Methods and Errors

Shechita is invalidated if the procedure deviates from precise halakhic requirements, rendering the animal nevelah (carcass) and its meat non-kosher. Prohibited methods include any form of pre-slaughter stunning or anesthesia, as these can cause internal injuries that disqualify the animal as treifah (torn), violating the mandate for the animal to be healthy and conscious at the time of slaughter.[1] The slaughter must employ a continuous drawing motion (chalaf) with a flawlessly smooth knife across the designated area of the neck, severing the trachea, esophagus, carotid arteries, and jugular veins without damaging surrounding structures.[49] Key errors that invalidate shechita fall into five primary categories of improper technique, known as pesulim (defects):- Shehiyah (pausing or hesitation): Any delay longer than the time required to raise, lower, and slaughter a knife renders the act invalid, as the motion must be uninterrupted.[50][49]

- Chaladah (covering or submerging): Inserting the knife between anatomical signs, under skin, wool, or cloth, or cutting in a hidden manner disqualifies the slaughter, as the cut must be direct and visible.[50][49]

- Drasah or Derasa (pressing or scraping): Applying pressure or striking instead of a slicing motion invalidates the procedure, emphasizing the need for a pure cutting action.[50][49]

- Ikur (uprooting or tearing): Displacing or tearing the trachea or esophagus, often from a defective knife or forceful yanking, results in invalidation unless a majority of one sign was properly cut beforehand.[50][49]

- Hagramah (slanting or improper placement): Cutting at an elevated or deviated point on the windpipe, outside the permitted area, disqualifies the animal if it fails to properly sever the required structures.[50][49]

Post-Slaughter Inspection and Processing

Bedikah and Organ Examination

Bedikah, the post-slaughter internal examination, is a required procedure in shechita to detect treifot—pre-existing physiological defects or diseases that would invalidate the animal for kosher consumption under Jewish law, as such conditions are presumed to have existed before the slaughter.[51][52] This inspection ensures the animal was healthy at the time of shechita, aligning with biblical prohibitions against consuming animals with certain internal blemishes or illnesses.[53][54] The examination primarily targets the lungs in mammals, scrutinizing for sirchot (adhesions or fibrous connections between lung tissue and the pleural cavity), abscesses, parasites, nodules, or perforations that could compromise the organ's integrity.[51][53] For birds, bedikah focuses on the digestive and respiratory systems, checking for defects like tumors or adhesions in the intestines and lungs.[52] The shochet typically conducts the initial bedikah immediately after slaughter, but in commercial facilities, a specialized bodek (trained inspector) often performs or verifies the detailed organ review to enhance accuracy and efficiency.[55][52] To execute bedikah, the carcass is opened via incision to access the thoracic and abdominal cavities, followed by evisceration where organs are removed and palpated, probed, or inflated with air to reveal hidden flaws such as minute holes or abnormal growths.[51][15] Lungs are particularly tested by immersion in water or manual separation to assess adhesion strength; minor, easily removable adhesions may permit kosher status in standard (not glatt) meat, while glatt kosher requires lungs free of significant sirchot, defined as no adhesions larger than a specific size or in prohibitive locations.[56][53] Detection of a disqualifying treifah results in the carcass being declared non-kosher, with the meat discarded or sold non-kosher, preventing consumption.[52][54] This rigorous process, rooted in Talmudic standards, underscores shechita's emphasis on animal health verification, with modern slaughterhouses employing multiple bodekim and standardized protocols to minimize errors, though disputes over adhesion classification can arise among rabbinic authorities.[56][15]Nikkur and Forbidden Fat Removal

Nikkur refers to the precise excision of prohibited anatomical components from a kosher-slaughtered animal's carcass, primarily the chelev (certain internal fats) and gid hanasheh (sciatic nerve), to render the meat permissible for consumption under Jewish dietary laws.[57][58] This procedure follows the bedikah inspection and demands specialized training, as improper removal can invalidate portions of the meat.[59] The prohibition on chelev derives from Torah commandments against consuming fats designated for altar offerings in sacrificial rites, such as those surrounding the kidneys, stomach, and intestines, which remain forbidden even in non-sacrificial animals.[60][61] These fats differ from permissible shuman (regular animal fat), with chelev identified by its texture, location, and historical sacrificial use; violation carries a biblical penalty equivalent to severe dietary transgressions.[59] Similarly, the gid hanasheh—a major nerve complex in the hindquarters—is banned based on Genesis 32:33, commemorating Jacob's injury during his encounter with the angel, extending to all adjoining blood vessels and fats to ensure complete removal.[58][59] The nikkur process, known as traibering in Yiddish, involves dissecting the carcass with sharp knives or by hand to isolate and excise these elements, often focusing on the hindquarters (achoraim) where complexities arise due to intertwined tissues.[59][62] Trained menakerim (nikkur specialists) follow codified guidelines from rabbinic texts like the Shulchan Aruch, removing not only primary forbidden parts but also adjacent tissues to prevent mixture.[57] For cattle and sheep, this can yield significant meat loss, with forequarters generally simpler to process and thus more commonly consumed. Poultry nikkur is less intricate, targeting veins and fats without the sciatic nerve issue.[58] In contemporary practice, Ashkenazi kosher authorities outside Israel frequently forgo full hindquarter nikkur due to its labor-intensive nature and risk of error, selling those sections to non-kosher markets while certifying only forequarters.[59][62] Sephardi and some Israeli operations perform complete nikkur, as evidenced by historical shifts like the 1876 initiation of hindquarter processing in Jerusalem's Ashkenazi community.[59] Oversight by certifying agencies ensures compliance, with discarded parts often repurposed for non-food uses to minimize waste.[57] This selective approach balances halachic stringency with economic viability, though full nikkur upholds maximal adherence to Torah prohibitions.[62]Kashering and Blood Removal

The prohibition against consuming blood, derived from Leviticus 17:10–14, necessitates the removal of blood from meat following shechita to render it kosher for Jewish dietary laws.[63] This process, known as kashering or melicha, targets blood absorbed into the flesh (dam ben pesulim), which is distinct from the blood expelled during slaughter. Kashering must occur promptly, ideally within 72 hours of slaughter, as blood congeals over time and becomes harder to extract; soaking in water can extend this period by another 72 hours.[64] The standard kashering procedure for mammalian and avian meat begins with haksala, or soaking, where the meat is immersed in room-temperature water for approximately 30 minutes to dislodge surface blood and open pores.[65] The meat is then drained briefly before melicha, during which it is thoroughly coated with coarse, non-iodized kosher salt on all sides and placed on a perforated or slanted board for one hour (or 20–30 minutes for poultry) to allow blood to drain via osmosis.[63] The salt must form a continuous layer without pooling, ensuring even extraction, and the process is completed with three rinses (halacha) in fresh water to remove residual salt and blood.[65] For organs like the liver, which retain blood internally due to their vascular structure, salting alone is insufficient; instead, libun kal (light broiling) over an open flame is required immediately after slaughter to evaporate remaining blood, often followed by salting.[66] Frozen meat cannot be kashered until fully thawed and handled as fresh, and utensils used must be dedicated to avoid cross-contamination with non-kosher blood.[63] These steps ensure compliance with halakhic standards, prioritizing thorough blood expulsion over mere surface cleaning.[64]Distribution of Divine Gifts

After kashering, the approved kosher meat is sealed with a plumba or stamp certifying its halachic compliance, ensuring traceability throughout the supply chain.[47] The carcass is segmented into primal cuts, with the forequarters predominantly retained for kosher use in regions like the United States, where hindquarter nikkur is often uneconomical and sold to non-kosher markets.[47] These portions are then transported under rabbinical oversight to certified kosher butchers, processors, and retailers, preventing commingling with non-kosher products.[47][35] In modern operations, centralized facilities enable efficient distribution, supplying over 1,000 outlets nationwide from daily slaughters of 500 to 1,200 cattle.[35] Only approximately 30% of shechita-processed animals ultimately yield meat suitable for this distribution, reflecting rigorous inspections that prioritize adherence to Torah prohibitions against treifot.[47] This process facilitates the provision of meat compliant with kashrut, enabling Jewish observance of dietary laws derived from biblical commandments on permissible consumption.[35]Covering of Blood

Ritual Requirements

The ritual obligation of kisui ha-dam (covering the blood) stems from Leviticus 17:13, which requires that the blood of any permissible wild animal (chayyah) or bird caught for food be poured out and covered with earth.[67] This commandment applies Torah-ally only to birds and undomesticated animals slaughtered via shechita, as domesticated animals (behemah) fall under Deuteronomy 12:16's directive to pour out blood without explicit covering, rendering it a rabbinic extension or customary practice for consistency.[68] The shochet bears primary responsibility for fulfilling the mitzvah immediately after shechita, typically by allowing the blood to spill onto the ground and then covering it to honor the animal's life force, viewed in rabbinic sources as an act of mercy akin to burial.[69] If the shochet neglects it, any observant Jew may perform the covering, as derived from Talmudic interpretation in Chullin 86a emphasizing communal obligation.[70] The covering must use earth or earth-derived materials, such as soil, dust, straw, or sawdust, applied both beneath and over the blood to fully conceal it, emulating the verse's "cover it with earth" (v'chisah ba'afar).[71] Insufficient coverage, such as partial concealment or use of non-earthy substances like lime, invalidates the mitzvah, though post-facto leniencies exist in exigent circumstances per Shulchan Aruch Yoreh De'ah 28.[72] For poultry, common in modern shechita, the blood from the severed neck is directed onto a surface and promptly buried under dirt; wild game follows similarly, but practical challenges arise if blood mixes with non-kosher elements, potentially requiring additional purification.[73] The act underscores blood's sanctity as the seat of the soul (Leviticus 17:11), prohibiting consumption and mandating dignified disposal outside the altar context.[74]Practical Methods

The mitzvah of kisuy hadam applies exclusively to the blood of birds and undomesticated animals (chayot) slaughtered via shechita, requiring coverage of the initial blood that emerges upon cutting the trachea and esophagus.[72] This is performed promptly after the slaughter to fulfill the biblical injunction in Leviticus 17:13, using materials such as earth, dust, or equivalents like straw or sawdust that simulate soil's absorptive and concealing properties.[74][71] In practice, the shochet—certified ritual slaughterer—typically performs the covering, though the obligation can be delegated to another individual present, as it is not contingent on the slaughterer alone.[67] For poultry, common in both home and commercial settings, the process involves scattering covering material beneath the blood flow to absorb the initial spurt, followed by an additional layer atop to conceal it fully; not all subsequent blood need be covered, only the primary outflow.[75] Sawdust is widely employed in modern Orthodox practice for its practicality in containing and masking the blood without scattering, particularly on absorbent surfaces in slaughter areas.[76][77] For wild animals, traditional methods favor natural earth or dust scooped from the ground, aligning with the verse's reference to "dust" (afar), though rabbinic authorities permit substitutes if soil is unavailable.[70] The act requires intent (kavanah) to perform the mitzvah, and both upper and lower coverage—absorbing below and concealing above—satisfy the requirement per Shulchan Aruch Yoreh De'ah 28:1.[71] Failure to cover invalidates the mitzvah but does not render the meat non-kosher, as kisuy hadam is a positive commandment without punitive disqualification for the animal's edibility.[74]Scientific Assessment of Animal Welfare

Physiological Effects and Insensibility